Submitted:

23 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Demographic and Socioeconomic Factors

2.4.2. Outcome Inventory 21 (OI-21)

2.4.3. Inner-Strength-Based Inventory (I-SBI)

2.4.4. Parental Stress Scale (PSS)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics

3.2. Table 2: Biological Characteristics

| Variables | Categories | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core-biological | No | 272 | 82.4 | |

| Yes | 58 | 17.6 | ||

| Bio-behavioral | No | 263 | 79.7 | |

| Yes | 67 | 20.3 | ||

| Secondary biological | No | 255 | 77.3 | |

| Yes | 75 | 22.7 | ||

| Composite biological | 0 | 207 | 62.7 | |

| 1 | 78 | 23.6 | ||

| 2 | 31 | 9.4 | ||

| 3 | 8 | 2.4 | ||

| 4 | 6 | 1.8 | ||

| Mean ± SD, min-max | 0.57 ± 0.8, 0-4 | |||

| Median, interquartile range | 0,1 | |||

3.3. Test Differences Between Associated Factors and Depression

3.4. Pearson’s Correlation among Variables

3.5. Tests of Moderation

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OI-21 | Outcome Inventory 21 |

| I-SBI | Inner-Strength-Based Inventory |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

References

- Liu, Q.; He, H.; Yang, J.; Feng, X.; Zhao, F.; Lyu, J. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J Psychiatr Res 2020, 126, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health in China. Available online: https://www.who.int/china/health-topics/mental-health (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Lin, W.; Wang, H.; Gong, L, Lai, G. ; Zhao, X.; Ding, H.; Wang, Y. Work stress, family stress, and suicide ideation: A cross-sectional survey among working women in Shenzhen, China. J Affect Disord 2020, 277, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymo, J.M.; Park, H.; Xie, Y.; Yeung, W. J. Marriage and Family in East Asia: Continuity and Change. Annu Rev Sociol 2015, 41, 471–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhong, S.; Li, L.; Luo, M. How housing burden damages residents’ health: Evidence from Chinese cities. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1345775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textor, C.; Population in China from 2014 to 2024, by gender. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1225146/china-employment-situation-of-mothers/ (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Chen, G.; Oubibi, M.; Liang, A.; Zhou, Y. Parents' Educational Anxiety Under the "Double Reduction" Policy Based on the Family and Students' Personal Factors. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2022, 15, 2067–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, T.; Gao, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Diao, H.; Zhang, G.; Shen, H.; Chang, R.; Yu, Z.; Lu, J.; Liang, L.; Zhang, L. Questionnaire development on measuring parents' anxiety about their children's education: Empirical evidence of parental perceived anxiety data for primary and secondary school students in China. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 1018313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.; Fu, R.; Coyte, P.C. How Do Middle-Aged Chinese Men and Women Balance Caregiving and Employment Income? Healthcare 2021, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Mai, Z.; Guan, X.; Cai, P.; Li, X.; Feng, J.; Hung, S. The Moderating Role of Social Capital Between Parenting Stress and Mental Health and Well-Being Among Working Mothers in China. Healthcare 2025, 2, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengelkoch, S.; Slavich, G.M. Sex differences in stress susceptibility as a key mechanism underlying depression risk. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2024, 26, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parents. Treating anxiety during pregnancy. https://www.parents.com/treating-anxiety-during-pregnancy-117267252. (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- Meltzer-Brody, S.; Miller, L. J. Postpartum hormonal changes and maternal mental health: A narrative review. J Womens Health 2021, 30, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Alblooshi, S.; Taylor, M.; Gill, N. Does menopause elevate the risk for developing depression and anxiety? Results from a systematic review. Australas Psychiatry 2023, 31, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, M.T.; Murphy, E.; Posner, J.E.; Talati, A.; Weissman, M.M. Association of multigenerational family history of depression with lifetime depressive and other psychiatric disorders in children: Results from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, M.T.; Zureigat, H.; Abohashem, S.; Mezue, K.; Gharios, C.; Grewal, S.; Cardeiro, A.; Naddaf, N.; Civieri, G.; Abbasi, T.; Radfar, A.; Aldosoky, W.; Seligowski, A.V.; Wasfy, M.M.; Guseh, J.S.; Churchill, T.W.; Rosovsky, R.P.; Fayad, Z.; Rosenzweig, A.; Baggish, A.; Pitman, R.K.; Choi, K.W.; Smoller, J.; Shin, L.M.; Tawakol, A. Anxiety and depression associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk through accelerated development of risk factors. JACC: Advances 2024, 3, 101208. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, D.C.; McDowell, C.P.; Kenny, R.A.; Herring, M.P. Dynamic associations between anxiety, depression, and tobacco use in older adults: Results from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing. J Psychiatr Res 2021, 139, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.; Johnson, S.E.; Mitrou, F.; Lawn, S.; Sawyer, M. Tobacco smoking and mental disorders in Australian adolescents. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2022, 56, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschloo, L.; Vogelzangs, N.; Smit, J.H.; van den Brink, W.; Veltman, D.J.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Alcohol use disorders and the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2012, 200, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, T.; Yang, T.; Varnado, P.; Siriai, Y.; Mirnics, Z.; Kövi, Z.; Wongpakaran, N. The development and validation of a new resilience inventory based on inner strength. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XIE, Ying. The relationship among internal strength, self-efficacy and quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease [D]. Yanji: Yanbian University.

- Mao, B.; Kanjanarat, P.; Wongpakaran, T.; Permsuwan, U.; O’Donnell, R. Factors Associated with Depression, Anxiety and Somatic Symptoms Among International Salespeople in the Medical Device Industry: A Cross-sectional Study in China. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Luo, Q.; Ma, W.; Xie, C. Status and development of community nursing in China: Challenges and opportunities. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1083091. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, C.; Tortolero, L.; Jun, S.; Cummins, D. D.; Saad, A.; Young, J.; Nunez Martinez, L.; Schulman, Z.; Marcuse, L.; Waters, A.; Mayberg, H.S.; Davidson, R.J.; Panov, F.; Saez, I. Intracranial substrates of meditation-induced neuromodulation in the amygdala and hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2025, 122, e2409423122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Pang, Z.; Li, G. The intervention effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on patients with depression. Psychol Mon 2024, 19, 121–123. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, N.G.; Rodney, T.; Peterson, J.K.; Baker, A.; Francis, L. Nurse-Led Mental Health Interventions for College Students: A Systematic Review. Prev Chronic Dis 2025, 22, E17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran; T. ; Kövi, Z. Development and validation of 21-item outcome inventory (OI-21). Heliyon 2022, 8, e09682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpakaran, T.; Yang, T.; Varnado, P.; Siriai, Y.; Mirnics, Z.; Kövi, Z.; Wongpakaran, N. The development and validation of a new resilience inventory based on inner strength. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.O.; Jones, W.H. The parental stress scale: initial psychometric evidence. J Soc Pers Relat 1995, 12, 463–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.K. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the parental stress scale. Psychologia 2000, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, G.; Di, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Prevalence and risk factors for depressive and anxiety symptoms in middle-aged Chinese women: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2022, 22, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripunya, P.; Wongpakaran, T.; Wongpakaran, N. The relationship between feelings of emptiness and self-harm among Thai patients exhibiting borderline personality disorder symptoms: The mediating role of the inner strengths. Medicina 2024, 60, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekpoo, K.; Wongpakaran, T.; Wongpakaran, N.; Siriai, Y. Inner strength and its association with mental health outcomes in patients with spinocerebellar ataxia: A cross-sectional study. J Neurol Sci 2023, 430, 120056. [Google Scholar]

- Gawlik, K.; Melnyk, B. Pandemic Parenting: Examining the Epidemic of Working Parental Burnout and Strategies to Help. [Report]. Ohio State University. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, G.; Carvalho, L.A.; Stafford, M.; Kivimäki, M. Association of working hours with depressive symptoms: a longitudinal study of UK employees. J Epidemiol Community Health 2019, 73, 448–454. [Google Scholar]

- Wasti, S.P.; Simkhada, P.; van Teijlingen, E.R.; Sathian, B.; Banerjee, I. The Growing Importance of Mixed-Methods Research in Health. Nepal J Epidemiol 2022, 12, 1175–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age |

30-35 | 94 | 28.5 |

| 36-40 | 141 | 42.7 | |

| 41-45 | 95 | 28.8 | |

|

Marital status |

Married/ cohabiting | 276 | 83.6 |

| Single | 9 | 2.7 | |

| Divorced/ widowed/ separated | 45 | 13.6 | |

| Children number |

1 | 189 | 57.3 |

| 2 | 111 | 33.6 | |

| ≥3 | 30 | 9.1 | |

| Educational level |

High school and below | 81 | 24.6 |

| High vocational school | 69 | 20.9 | |

| Bachelor’s degree and above | 180 | 54.5 | |

| 1-20 | 48 | 14.6 | |

| Weekly working hours |

21-39 | 77 | 23.3 |

| 40-54 | 147 | 44.5 | |

| ≥55 | 58 | 17.6 | |

|

Annual income (CNY) |

0-60,000 | 78 | 23.6 |

| 61,000-10,000 | 88 | 26.7 | |

| 101,000-150,000 | 81 | 24.5 | |

| >151,001 | 83 | 25.2 |

|

Variables |

OI-Depression Score (Mean ±SD) |

Test Difference |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 30-35 | 6.67±5.7 | F (2, 327) = 4.572 | p < 0.05 |

| 36-40 | 4.73±4.3 | ||

| 41-45 | 5.31±4.6 | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married/ cohabiting | 4.87±4.5 |

F (2, 327) = 12.878 |

|

| Single | 7.78±7.3 | p < 0.001 | |

| Divorced/ widowed/ separated | 8.56±5.4 | ||

| Children number | |||

| 1 | 4.03±4.2 | F (2, 327) = 36.693 | p < 0.001 |

| 2 | 6.32±5.0 | ||

| ≥3 | 11.17±3.8 | ||

| Educational level | |||

| High school and below | 9.74±5.0 | F (2, 327) = 55.364 | p < 0.001 |

| High vocational school | 4.52±3.8 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree and above | 3.87±4.1 | ||

| Weekly working hours | |||

| 1-20 | 5.15±4.9 |

F (3, 326) = 16.181 |

|

| 21-40 | 3.53±4.2 | p < 0.001 | |

| 41-54 | 5.16±4.5 | ||

| ≥55 | 8.98±5.0 | ||

| Table 3. Cont | |||

| Annual income | |||

| 0-60,000 | 6.96±5.6 |

F (4, 325) = 10.995 |

|

| 61,000-10,000 | 6.74±4.7 | p < 0.001 | |

| 101,000-150,000 | 5.36±4.2 | ||

| >151,001 | 2.80±3.9 | ||

| Hormonal fluctuations | |||

| No | 5.03±4.9 |

F (3, 326) = 4.708 |

|

| Pregnancy | 7.00±4.9 | ||

| Within 1 year after delivery | 8.11±4.7 | p < 0.01 | |

| Perimenopause or menopause | 7.94±4.4 | ||

| Smoking | |||

| No | 5.11±4.7 | F (1, 328) = 26.329 | p < 0.001 |

| Yes | 10.70±4.4 | ||

| Alcohol use | |||

| No | 4.96±4.7 | F (1, 328) = 31.888 | p < 0.001 |

| Yes | 9.82±5.0 | ||

| Family psychiatric history |

|||

| No | 5.25±4.8 | F (1, 328) = 18.229 | p < 0.001 |

| Yes | 11.80±4.8 | ||

| Psychical disease(s) | |||

| No | 4.65±4.7 |

F (5, 324) = 8.234 |

|

| Arthritis | 6.11±4.4 | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 7.90±5.6 | p < 0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 8.85±4.7 | ||

| Diabetes | 5.83±4.8 | ||

| Others | 9.71±4.4 | ||

| Items | Composite biological | I-SBI | OI-Depression | PSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite biological | - | |||

| I-SBI | -0.347** | - | ||

| OI-Depression | 0.429** | -0.708** | - | |

| PSS | 0.371** | -0.705** | 0.837** | - |

| B Coefficient | SE | t | p-value | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Regression Model | ||||||

| Constant | 2.517 | 1.501 | 1.677 | 0.950 | ||

| Composite biological | 1.599 | 0.241 | 6.623 | < 0.001 | ||

| Age | -0.310 | 0.280 | -1.107 | 0.269 | ||

| Weekly working hours | 0.499 | 0.206 | 2.429 | 0.016 | ||

| Marital status | 1.069 | 0.533 | 2.006 | 0.046 | ||

| Educational level | -0.973 | 0.215 | -4.536 | < 0.001 | ||

| Number of children | 2.010 | 0.317 | 6.335 | < 0.001 | ||

| Annual income (CNY) | -0.432 | 0.175 | -2.477 | 0.014 | ||

| R2 | 0.671 (F=37.744, Df1=5, Df2=322, P<0.0001) | |||||

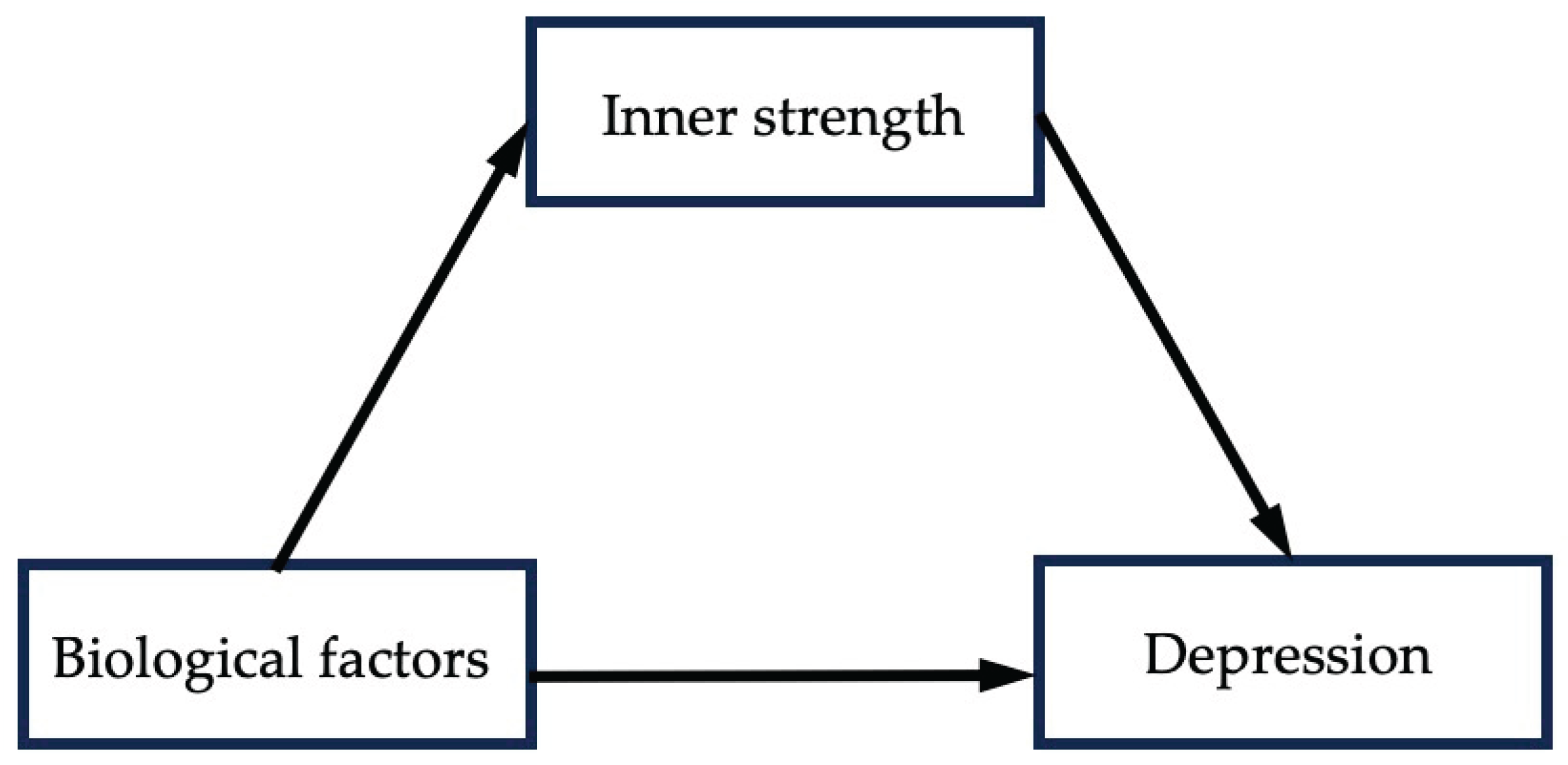

| Mediation model (Model 4) | ||||||

| Constant | -0.3095 | 1.5675 | -0.1974 | 0.8436 | -3.3934 | 2.7745 |

| Composite biological | 0.5838 | 0.1714 | 3.4059 | 0.0007 | 0.2466 | 0.9211 |

| I-SBI | -0.1432 | 0.0244 | -5.8629 | 0.0000 | -0.1912 | -0.0951 |

| PSS | 0.1916 | 0.0145 | 13.2075 | 0.0000 | -0.1631 | 0.2201 |

| Age | -0.1035 | 0.1894 | -0.5465 | 0.5851 | -0.4761 | 0.2691 |

| Weekly working hours | 0.2412 | 0.1396 | 1.7273 | 0.0851 | -0.0335 | 0.5159 |

| Marital status | 0.6675 | 0.3622 | 1.8428 | 0.0663 | -0.0451 | 1.3801 |

| Educational level | -0.2192 | 0.1516 | -1.4463 | 0.1491 | -0.5175 | 0.0790 |

| Number of children | -0.4798 | 0.2505 | -1.9155 | 0.0563 | -0.9725 | 0.0130 |

| Annual Income (CNY) | 0.2340 | 0.1244 | 1.8806 | 0.0609 | -0.0108 | 0.4788 |

| R2 | 0.751 (F= 106.954, df1=9, Df2= 320, p<0.001) | |||||

| β | S.E. | LLCI | ULCI | p-value | Effective size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 1.600 | 0.2415 | 1.1242 | 2.0744 | 0.000 | |

| Direct effect | 0.977 | 0.210 | 0.564 | 1.389 | 0.000 | 61.06% |

| Indirect effect | 0.623 | 0.170 | 0.294 | 0.962 | 38.94% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).