Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

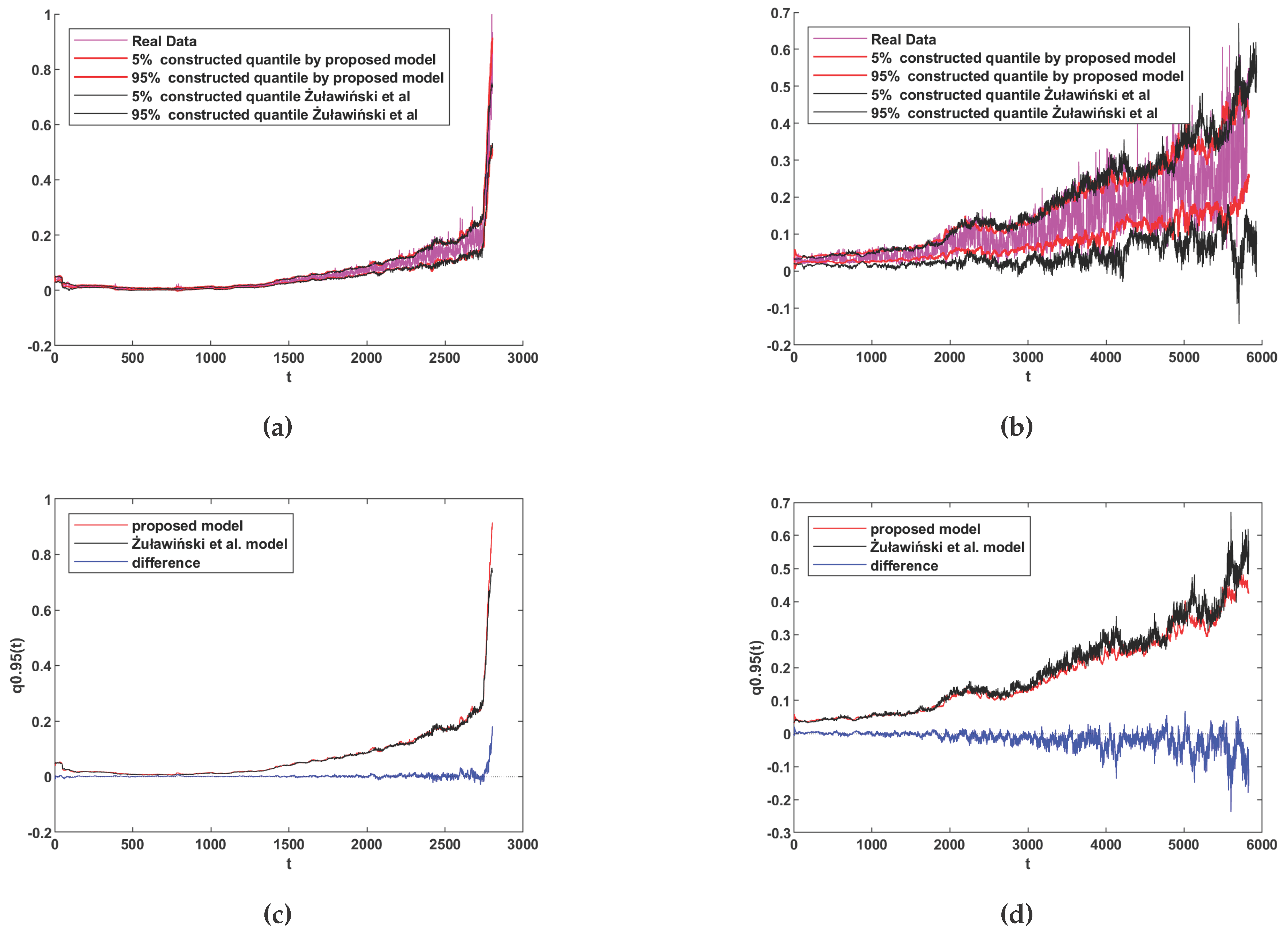

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A model of HI data was proposed as a three-segment sequence with non-stationary characteristics in both random and deterministic components to describe the degradation process, which can be used to simulate the artificial data set.

- Online identification of the time-varying random characteristics component like mean (location) and variance (scale), and also the dependency between them, is described for the TVC-AR model.

- A long-term data model based on TVC-AR is proposed for identification and modelling, and extensive experiments are carried out on the simulated data set and FEMTO and wind turbine datasets to verify its effectiveness.

2. Methodology and Theory

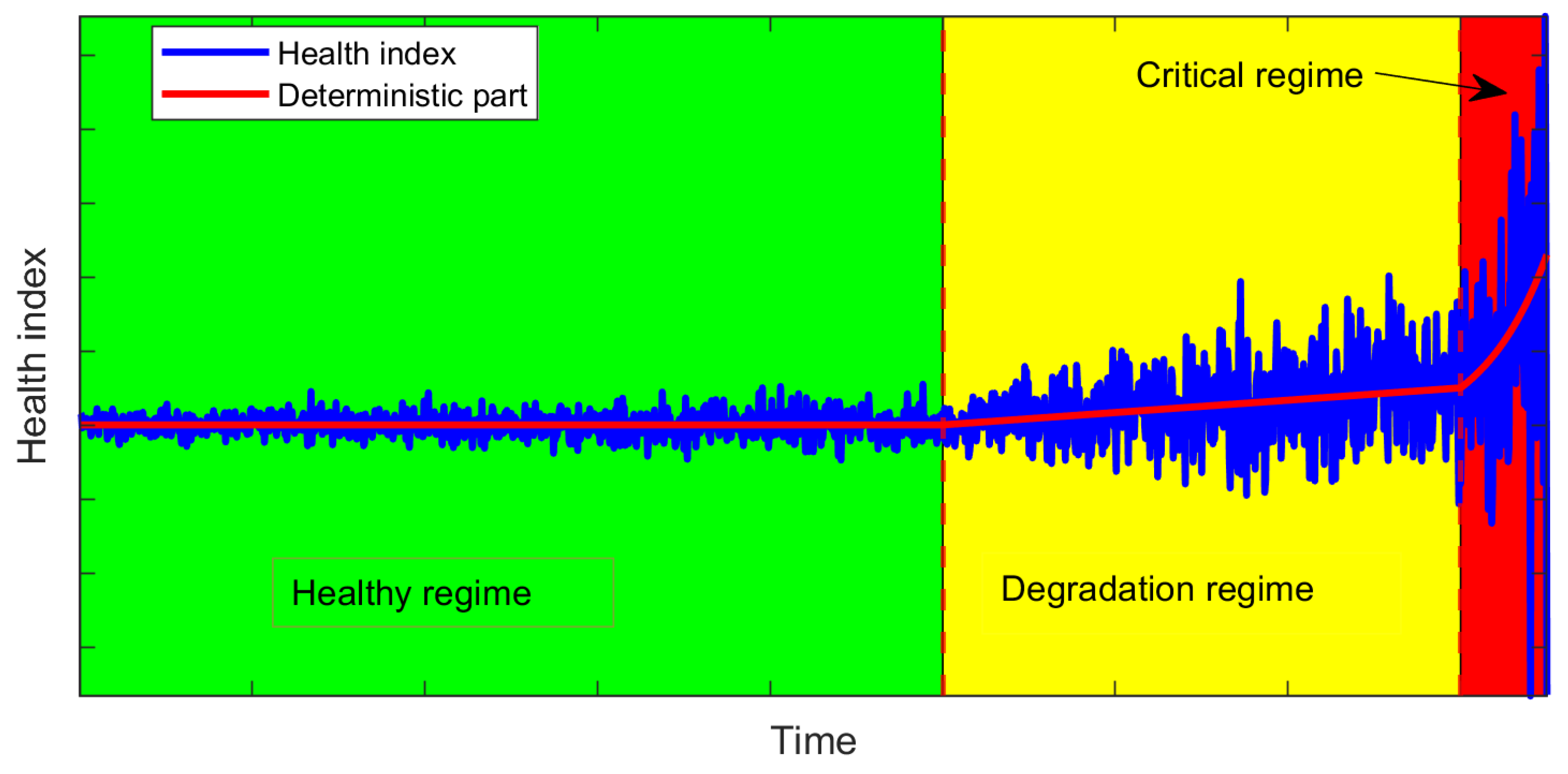

2.1. Degradation Model

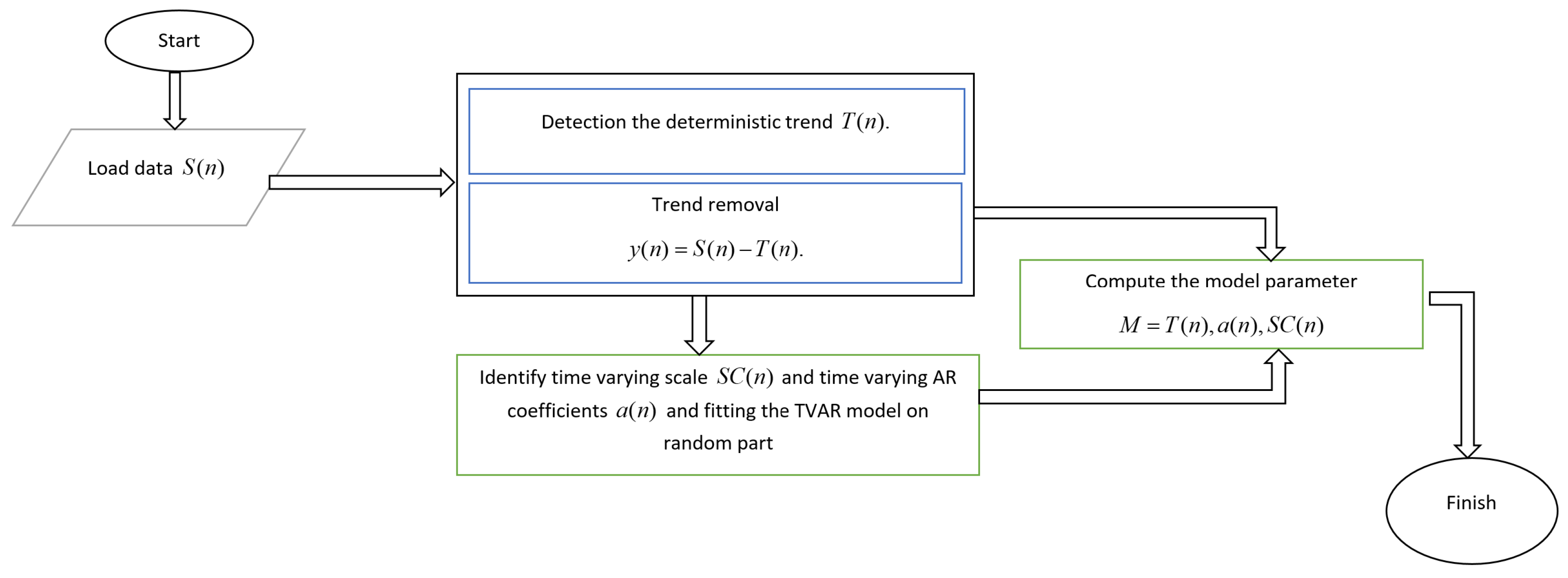

2.2. Methodology

2.3. Theory

2.3.1. Deterministic Component

2.3.2. Separating the Random and Deterministic Component

2.3.3. Random Component

- Time varying autoregressive model (TVC-AR)

- Model

- State space representations

- [Prediction]

- [Update]Above, and denote respectively the mean and covariance matrix of the state vector (estimated from the Kalman filter) given the data . The term is called Kalman gain.

- [Smoothing]Note that the state vector consists of the coefficients , and thus their estimates are directly obtained via .

- Estimation and identification of the model

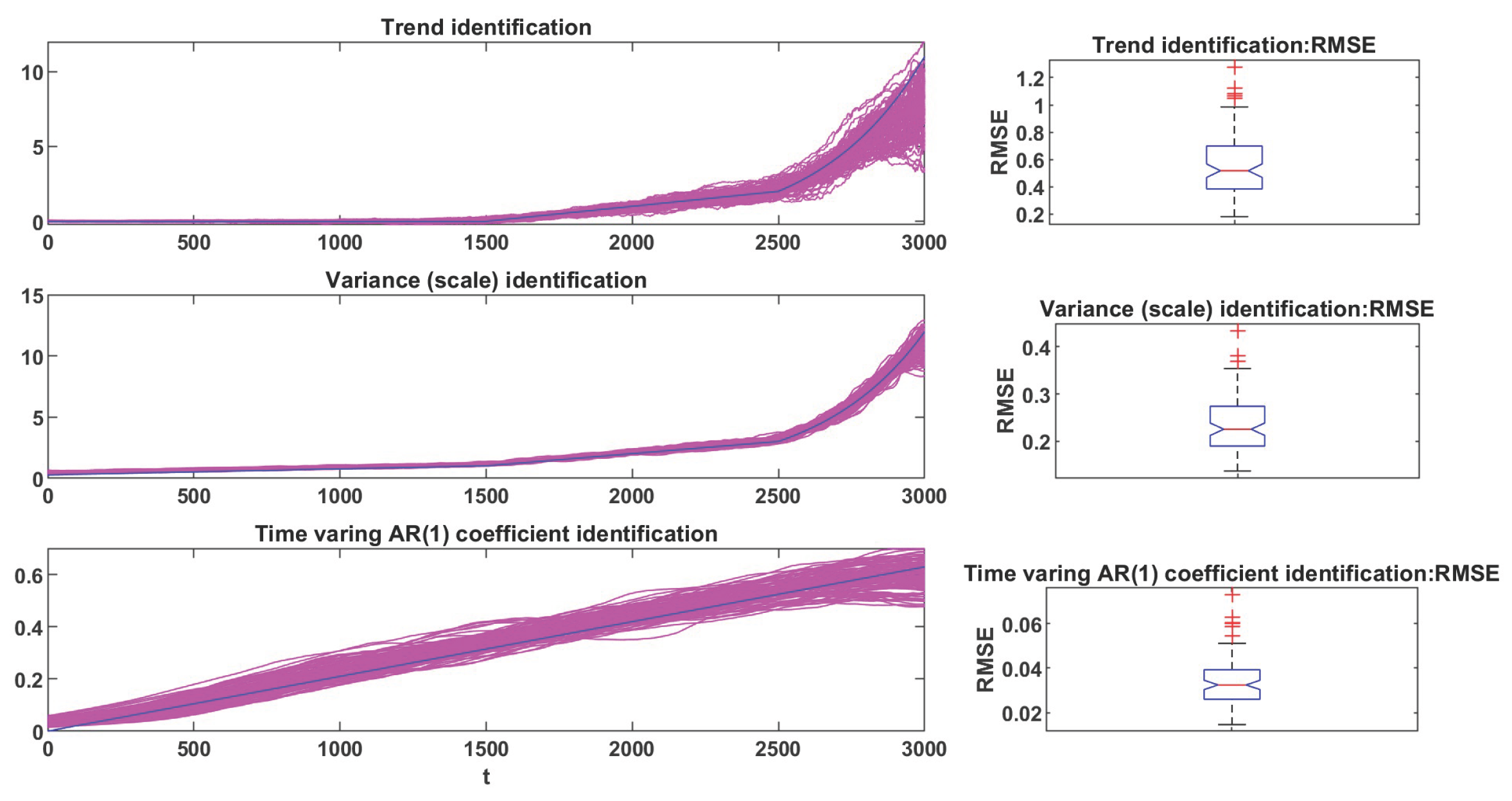

3. Simulation

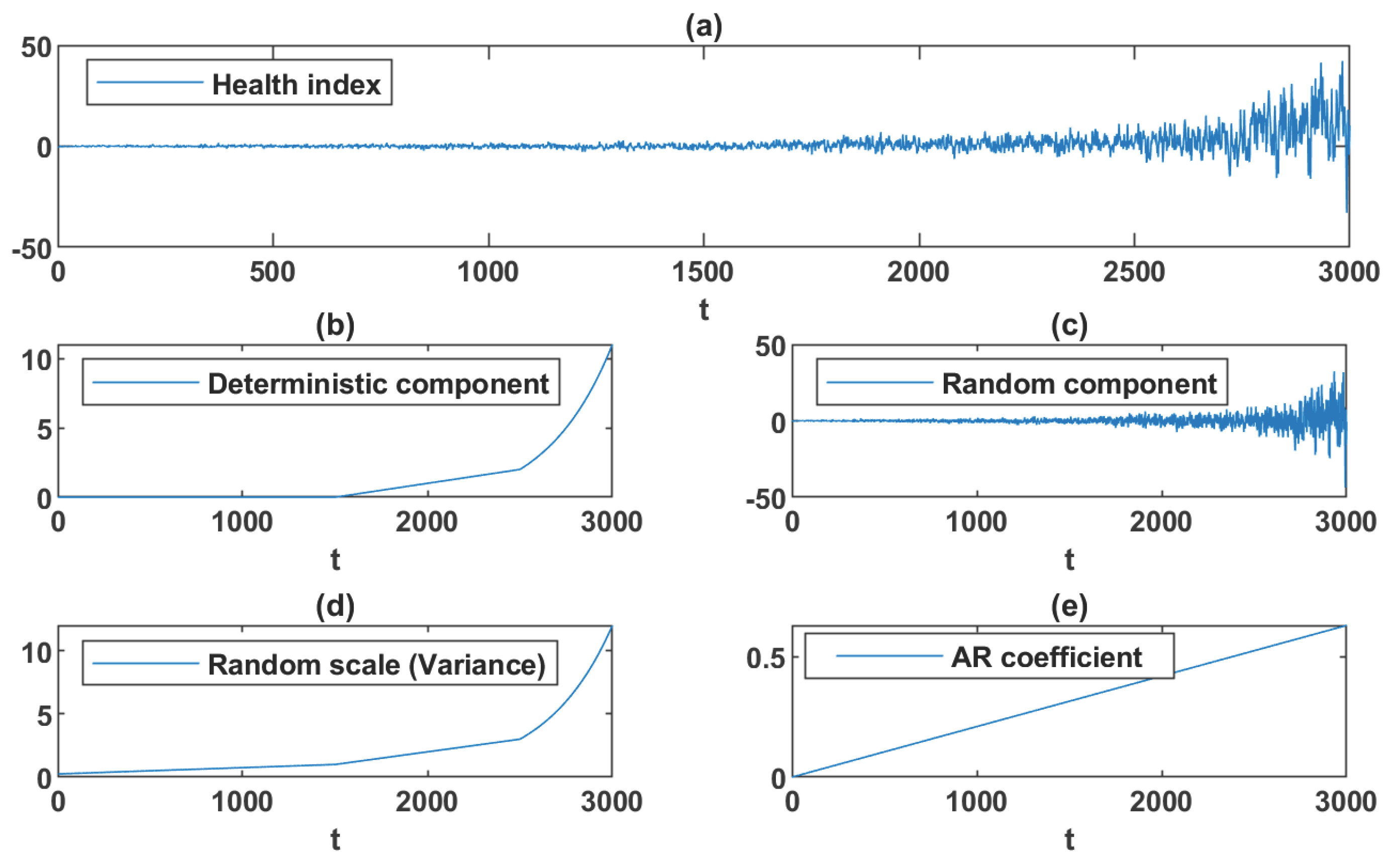

3.1. Generating the Degradation Data

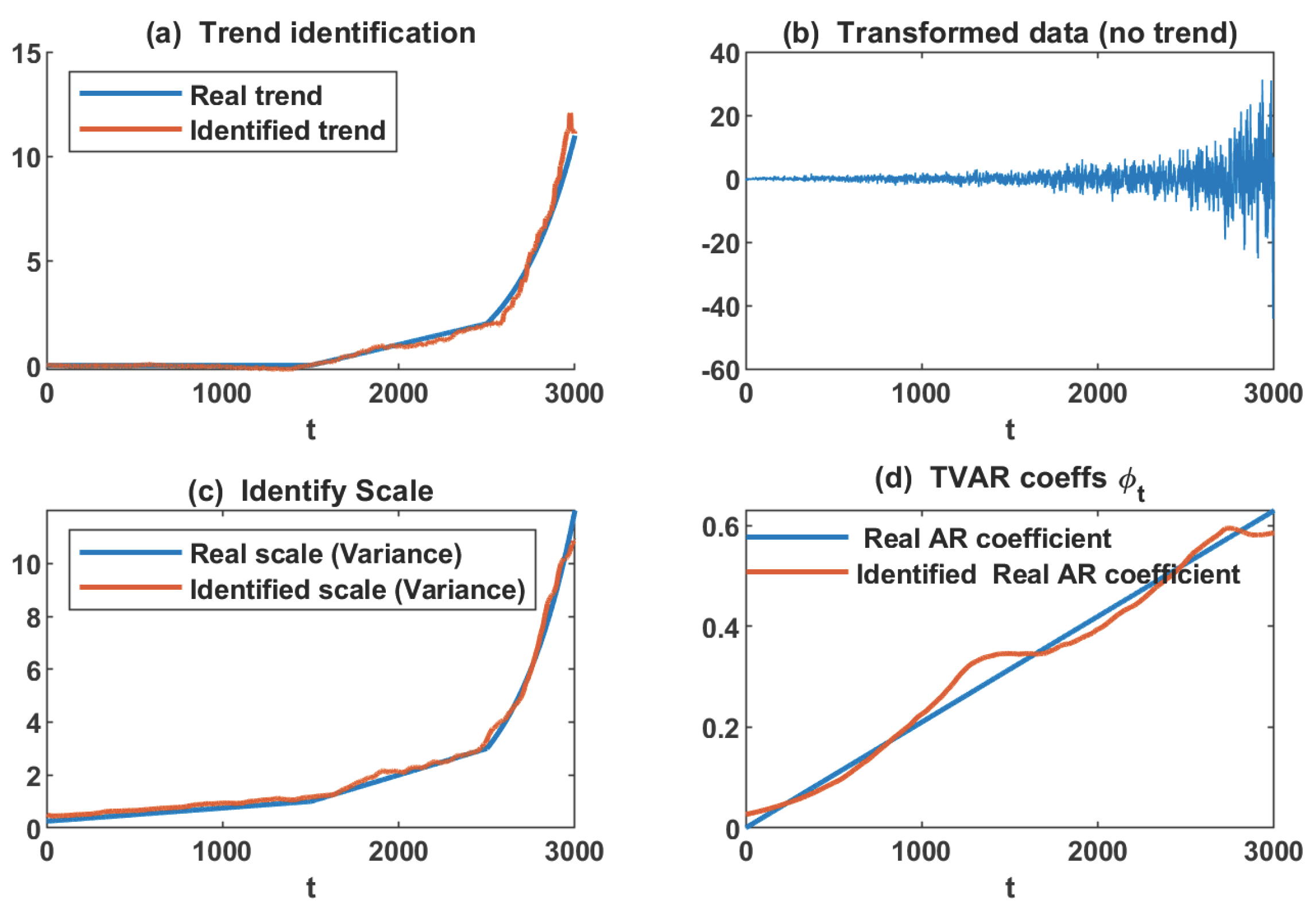

3.2. Results of Proposed Approach

4. Real Data Analysis

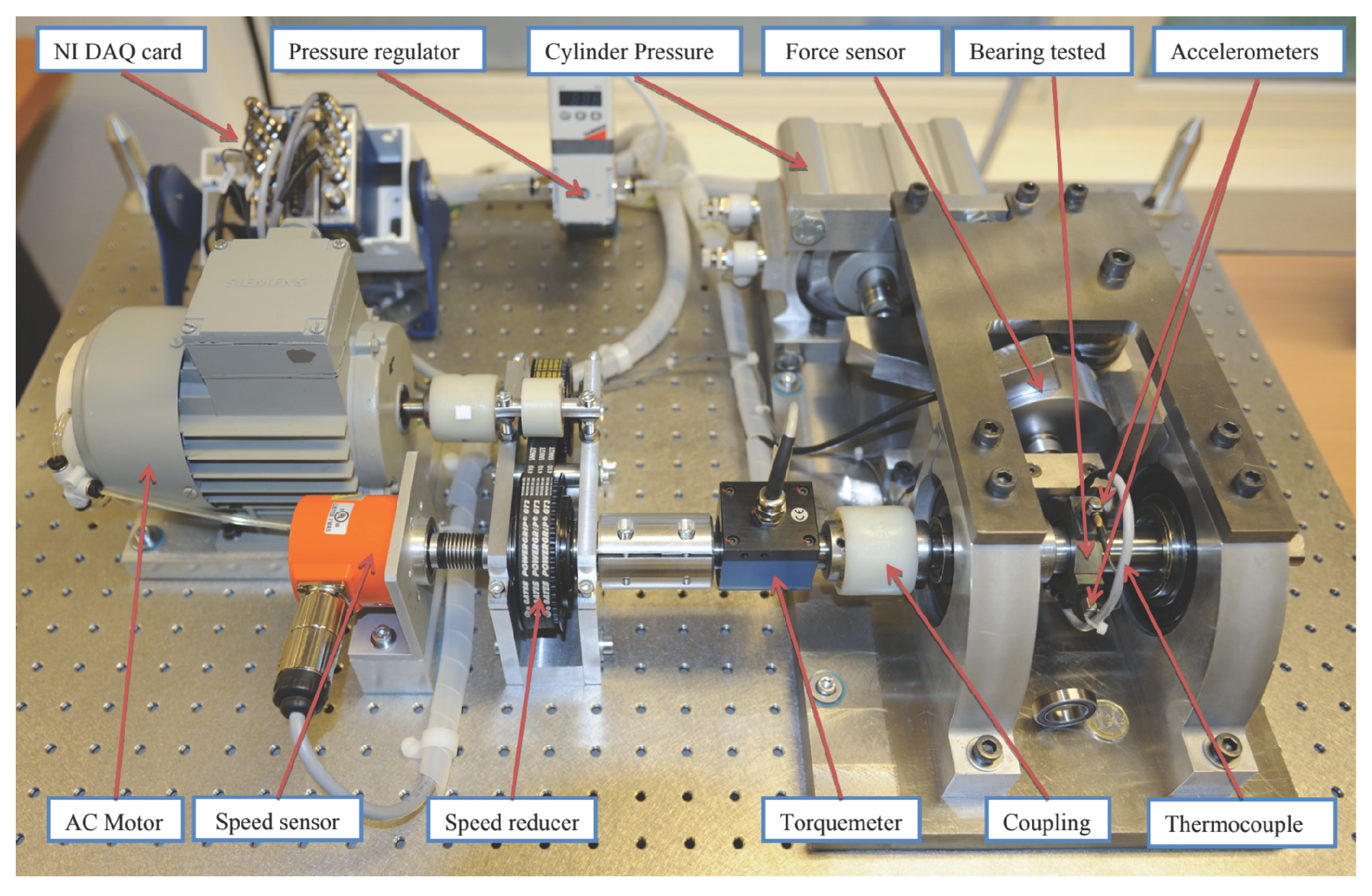

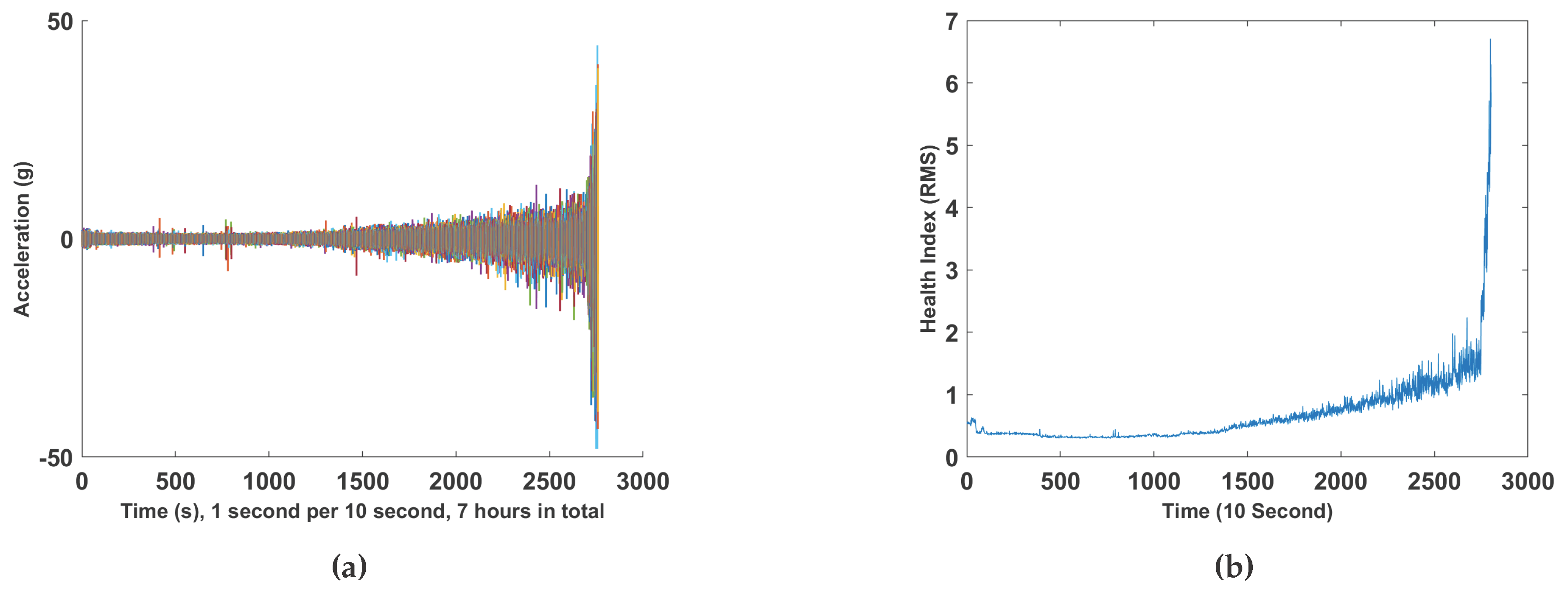

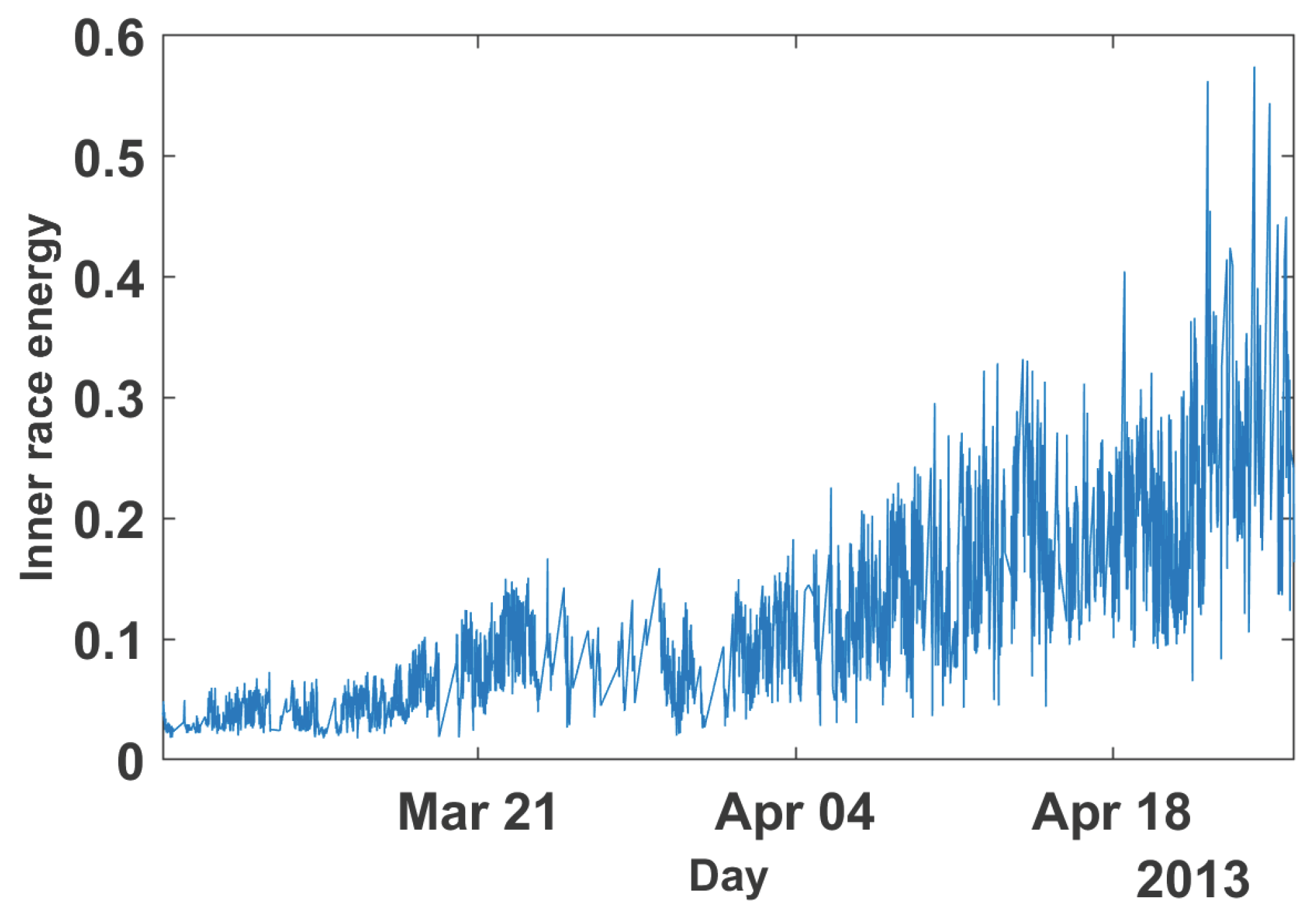

4.1. FEMTO Dataset

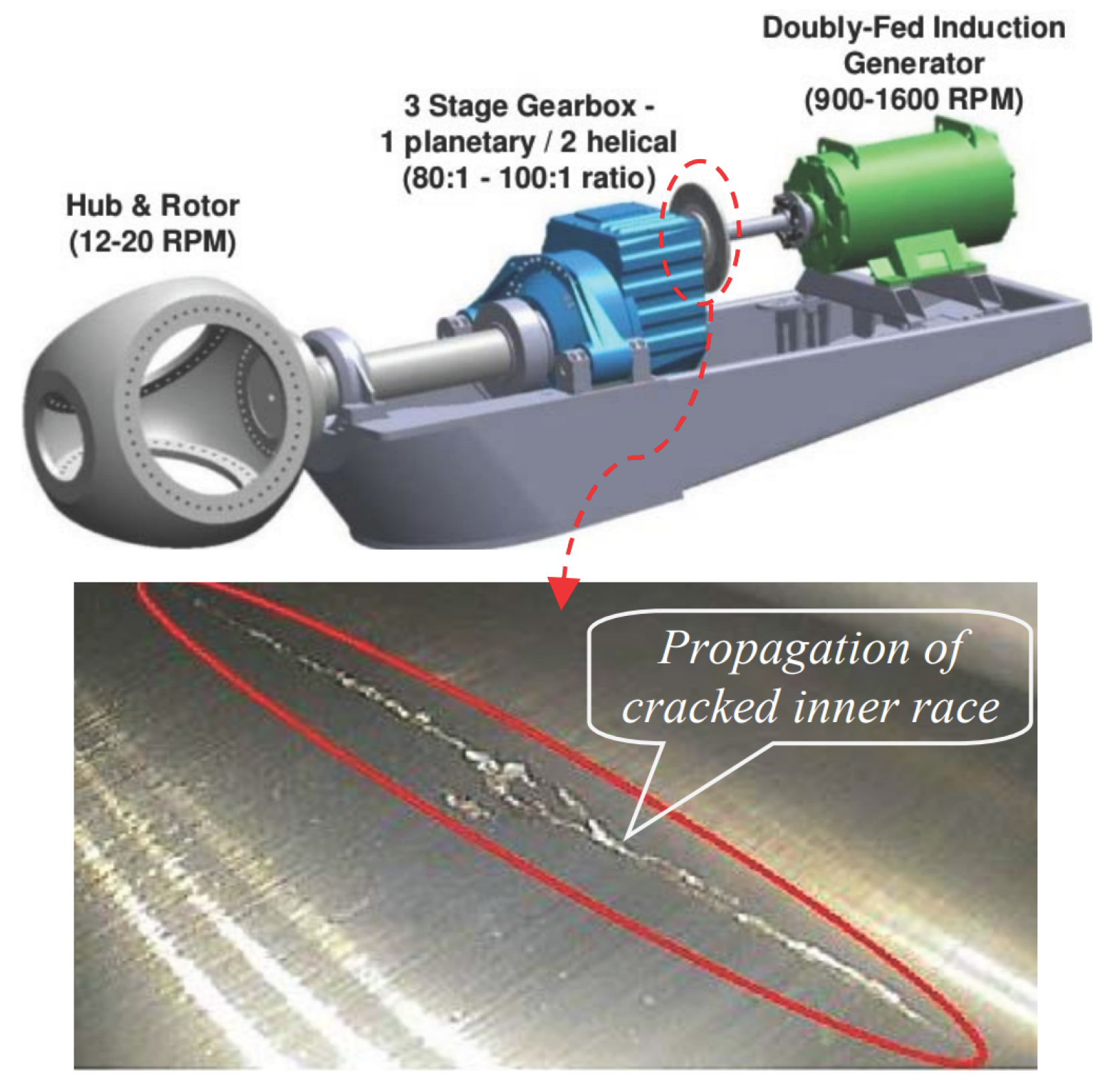

4.2. Wind Turbine Data Set

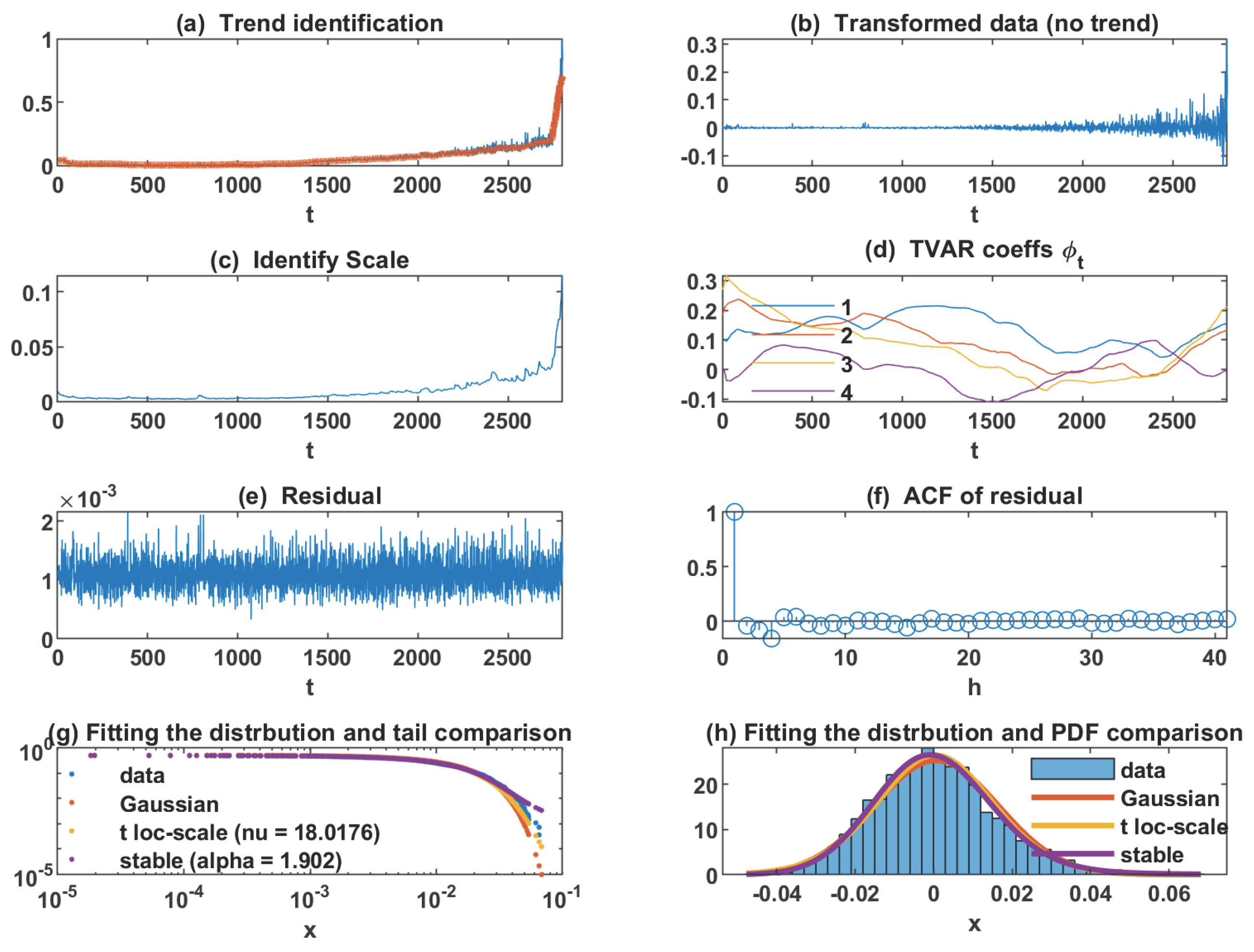

4.3. Result for FEMTO Data Set

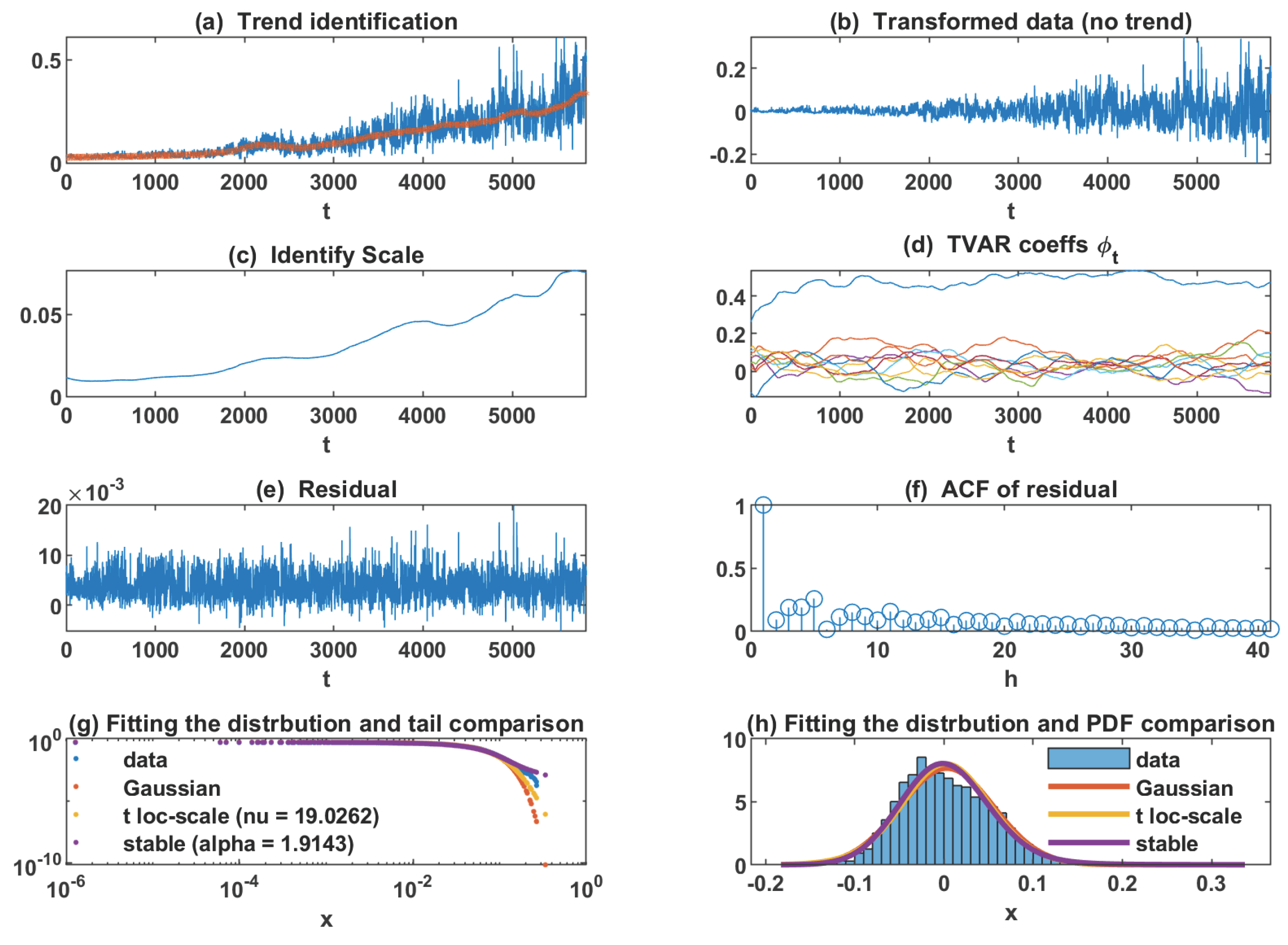

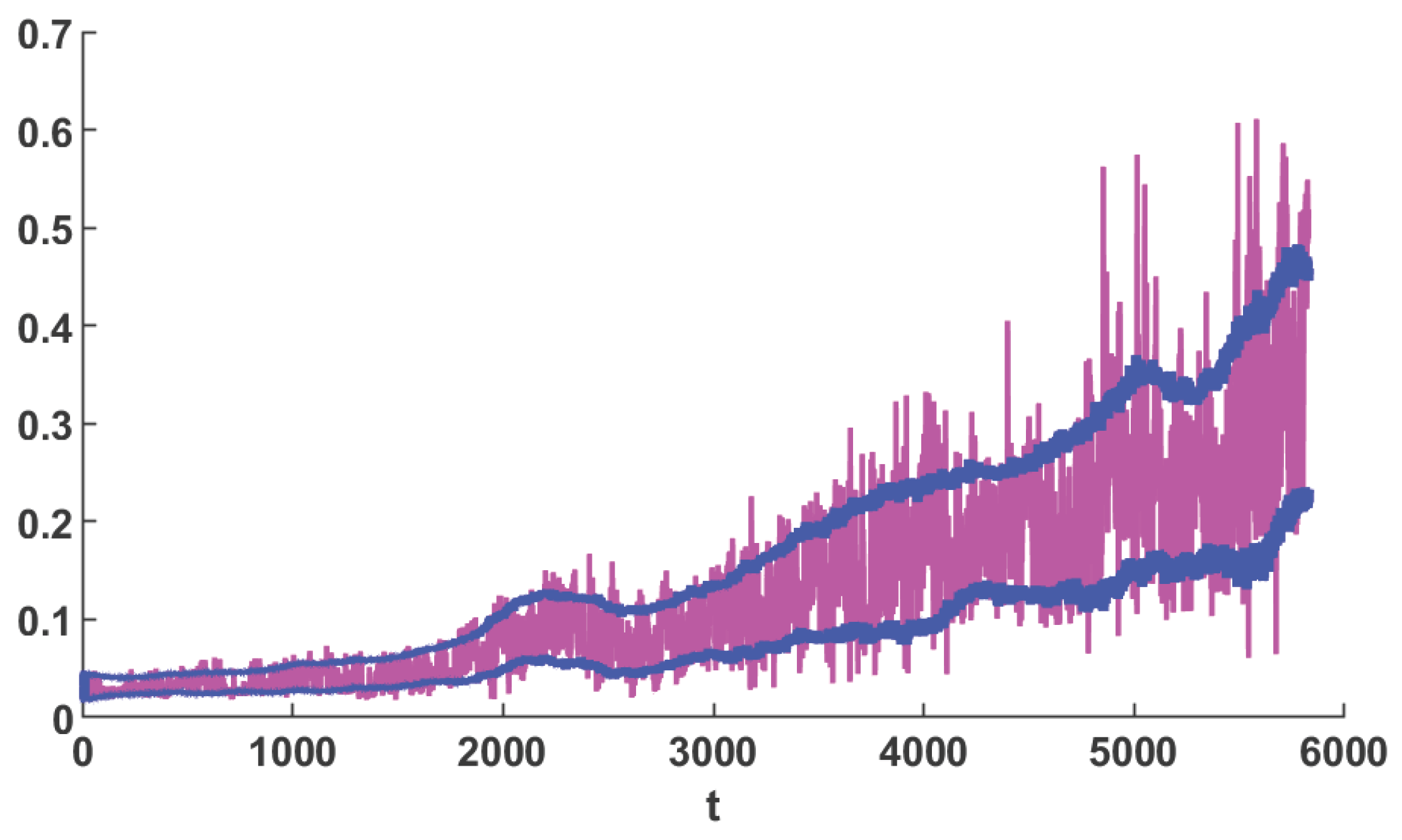

4.4. Result for Wind Turbine

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Heavy Tailed Probability Density Function

Appendix A.1. Stable Distribution

Appendix A.2. Student T Distribution

References

- Kourou, K.; Exarchos, T.P.; Exarchos, K.P.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Fotiadis, D.I. Machine learning applications in cancer prognosis and prediction. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2015, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, K.; Iversen, L.; Titlestad, T.L.; Winther, O. Systematic review of machine learning for diagnosis and prognosis in dermatology. Journal of Dermatological Treatment 2020, 31, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Olivan, A.; Del Ser, J.; Galar, D.; Sierra, B. Data fusion and machine learning for industrial prognosis: Trends and perspectives towards Industry 4.0. Information Fusion 2019, 50, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, F.; Shiri, H.; Wodecki, J.; Wyłomańska, A.; Zimroz, R. Application of Machine Learning Tools for Long-Term Diagnostic Feature Data Segmentation. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, X.S.; Wang, W.; Hu, C.H.; Zhou, D.H. Remaining useful life estimation–a review on the statistical data driven approaches. European journal of operational research 2011, 213, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.S.; Xie, M. Stochastic modelling and analysis of degradation for highly reliable products. Applied Stochastic Models in Business and Industry 2015, 31, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharczyk, D.; Wyłomańska, A.; Obuchowski, J.; Zimroz, R.; Madziarz, M. Stochastic modelling as a tool for seismic signals segmentation. Shock and Vibration 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, H.; Zimroz, P.; Wodecki, J.; Wyłomańska, A.; Zimroz, R. Data-driven segmentation of long term condition monitoring data in the presence of heavy-tailed distributed noise with finite-variance. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2023, 205, 110833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, A.; Zhang, S.; Tan, A.C.; Mathew, J. Rotating machinery prognostics: State of the art, challenges and opportunities. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2009, 23, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, M.S.; Tan, A.C.; Mathew, J. A review on prognostic techniques for non-stationary and non-linear rotating systems. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2015, 62, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Köttig, F. Review of hybrid prognostics approaches for remaining useful life prediction of engineered systems, and an application to battery life prediction. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2014, 63, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, T.; Sun, C.; Yan, R.; Chen, X. Challenges and opportunities of AI-enabled monitoring, diagnosis & prognosis: A review. Chinese Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2021, 34, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Li, N.; Guo, L.; Li, N.; Yan, T.; Lin, J. Machinery health prognostics: A systematic review from data acquisition to RUL prediction. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2018, 104, 799–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Fink, O.; Zhou, J.; Ma, Y. Controlled physics-informed data generation for deep learning-based remaining useful life prediction under unseen operation conditions. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2023, 197, 110359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Ma, X.; Huang, G.; Zhao, Y. Two-stage physics-based Wiener process models for online RUL prediction in field vibration data. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2021, 152, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Carr, M.; Xu, W.; Kobbacy, K. A model for residual life prediction based on Brownian motion with an adaptive drift. Microelectronics Reliability 2011, 51, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L.; Gebraeel, N. Stochastic methodology for prognostics under continuously varying environmental profiles. Statistical Analysis and Data Mining: The ASA Data Science Journal 2013, 6, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Chen, M.; Zhou, D. Remaining useful life prediction for degradation processes with memory effects. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2017, 66, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, M.; Ng, H.; Tsui, K. Bayesian and likelihood inferences on remaining useful life in two-phase degradation models under gamma process. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2019, 184, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Song, W.; Niu, Y.; Zio, E. A generalized cauchy method for remaining useful life prediction of wind turbine gearboxes. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2021, 153, 107471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Liu, H.; Zio, E. Long-range dependence and heavy tail characteristics for remaining useful life prediction in rolling bearing degradation. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2022, 102, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jia, C.; Chen, M. Remaining Useful Life Prediction for Degradation Processes With Dependent and Nonstationary Increments. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żuławiński, W.; Maraj-Zygmąt, K.; Shiri, H.; Wyłomańska, A.; Zimroz, R. Framework for stochastic modelling of long-term non-homogeneous data with non-Gaussian characteristics for machine condition prognosis. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2023, 184, 109677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Luo, Y.; Liu, J.; Peng, Y.; Guo, L.; Pecht, M. Lithium-ion battery remaining useful life estimation based on fusion nonlinear degradation AR model and RPF algorithm. Neural Computing and Applications 2014, 25, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Chen, H. A review on prognostics approaches for remaining useful life of lithium-ion battery. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing; 2017. Vol. 93. p. 012040. [Google Scholar]

- Prado, R.; Huerta, G.; West, M. Bayesian time-varying autoregressions: Theory, methods and applications. Resenhas do Instituto de Matemática e Estatística da Universidade de São Paulo 2000, 4, 405–422. [Google Scholar]

- Prado, R.; West, M. Time series: modeling, computation, and inference; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2010.

- Krishnan, M.; Bhowmik, B.; Hazra, B.; Pakrashi, V. Real time damage detection using recursive principal components and time varying auto-regressive modeling. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2018, 101, 549–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiong, G.; Liu, H.; Zou, H.; Guo, W. Time-frequency representation based on time-varying autoregressive model with applications to non-stationary rotor vibration analysis. Sadhana 2010, 35, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, N.; Gath, I. Segmentation of EEG during sleep using time-varying autoregressive modeling. Biological cybernetics 1989, 61, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.L.; Billings, S.A.; Liu, J.J. Time-varying parametric modelling and time-dependent spectral characterisation with applications to EEG signals using multiwavelets. International Journal of Modelling, Identification and Control 2010, 9, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Holan, S.H.; Yang, W.H. Bayesian Circular Lattice Filters for Computationally Efficient Estimation of Multivariate Time-Varying Autoregressive Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.12280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudoy, D.; Quatieri, T.F.; Wolfe, P.J. Time-varying autoregressions in speech: Detection theory and applications. IEEE Transactions on audio, Speech, and Language processing 2010, 19, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, A. A test of the adaptive market hypothesis using a time-varying AR model in Japan. Finance Research Letters 2016, 17, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.L.; Phillips, P.C. Adaptive estimation of autoregressive models with time-varying variances. Journal of Econometrics 2008, 142, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.Q. Time Varying Coefficient AR and VAR Models. In The Practice of Time Series Analysis; Akaike, H., Kitagawa, G., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 1999; pp. 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Nectoux, P.; Gouriveau, R.; Medjaher, K.; Ramasso, E.; Chebel-Morello, B.; Zerhouni, N.; Varnier, C. PRONOSTIA: An experimental platform for bearings accelerated degradation tests. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management, PHM’12. IEEE Catalog Number: CPF12PHM-CDR; 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mosallam, A.; Medjaher, K.; Zerhouni, N. Time series trending for condition assessment and prognostics. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutas, T.H.; Roulias, D.; Georgoulas, G. Remaining useful life estimation in rolling bearings utilizing data-driven probabilistic e-support vectors regression. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2013, 62, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, K.; Gouriveau, R.; Zerhouni, N.; Nectoux, P. Enabling health monitoring approach based on vibration data for accurate prognostics. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2014, 62, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, R.K.; Strangas, E.G.; Aviyente, S. Extended Kalman filtering for remaining-useful-life estimation of bearings. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2014, 62, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J. Degradation feature selection for remaining useful life prediction of rolling element bearings. Quality and Reliability Engineering International 2016, 32, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zio, E.; Wang, W. An adaptive method for health trend prediction of rotating bearings. Digital Signal Processing 2014, 35, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Li, N.; Gontarz, S.; Lin, J.; Radkowski, S.; Dybala, J. A model-based method for remaining useful life prediction of machinery. IEEE Transactions on Reliability 2016, 65, 1314–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Wan, J. Estimation of remaining useful life of bearings using sparse representation method. In Proceedings of the 2015 Prognostics and System Health Management Conference (PHM). IEEE; 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shiri, H.; Zimroz, P.; Wodecki, J.; Wyłomańska, A.; Zimroz, R.; Szabat, K. Using long-term condition monitoring data with non-Gaussian noise for online diagnostics. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2023, 200, 110472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimotho, J.K.; Sondermann-Wölke, C.; Meyer, T.; Sextro, W. Machinery Prognostic Method Based on Multi-Class Support Vector Machines and Hybrid Differential Evolution–Particle Swarm Optimization. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2013, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Zurita, D.; Carino, J.A.; Delgado, M.; Ortega, J.A. Distributed neuro-fuzzy feature forecasting approach for condition monitoring. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Emerging Technology and Factory Automation (ETFA).; IEEE, 2014, pp. 1–8.

- Guo, L.; Gao, H.; Huang, H.; He, X.; Li, S. Multifeatures fusion and nonlinear dimension reduction for intelligent bearing condition monitoring. Shock and Vibration 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Sun, Y.; Que, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chow, T.W. Anomaly detection and fault prognosis for bearings. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2016, 65, 2046–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, H.; Wodecki, J.; Zimroz, R. Robust switching Kalman filter for diagnostics of long-term condition monitoring data in the presence of non-Gaussian noise. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing; 2023. Vol. 1189. p. 012007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y. Rolling bearing reliability estimation based on logistic regression model. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Quality, Reliability, Risk, Maintenance,, and Safety Engineering (QR2MSE). IEEE, 2013; pp. 1730–1733. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Ke, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, Y. Remaining useful life prediction for an adaptive skew-Wiener process model. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2017, 87, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Zi, Y.; Jin, X.; Tsui, K.L. A two-stage data-driven-based prognostic approach for bearing degradation problem. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2016, 12, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, H.; Zimroz, P.; Wyłomańska, A.; Zimroz, R. Estimation of machinery’s remaining useful life in the presence of non-Gaussian noise by using a robust extended Kalman filter. Measurement 2024, 235, 114882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.z. Reliability estimation and remaining useful lifetime prediction for bearing based on proportional hazard model. Journal of Central South University 2015, 22, 4625–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M. A novel approach for bearing remaining useful life estimation under neither failure nor suspension histories condition. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 2017, 28, 1893–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechhoefer, E.; Schlanbusch, R. Generalized Prognostics Algorithm Using Kalman Smoother. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2015, 48, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, L.; Ali, J.B.; Bechhoefer, E.; Benbouzid, M. Wind turbine high-speed shaft bearings health prognosis through a spectral Kurtosis-derived indices and SVR. Applied Acoustics 2017, 120, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, L.; Bechhoefer, E.; Ali, J.B.; Benbouzid, M. Wind turbine high-speed shaft bearing degradation analysis for run-to-failure testing using spectral kurtosis. In Proceedings of the 2015 16th International Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering (STA). IEEE; 2015; pp. 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, J.B.; Saidi, L.; Harrath, S.; Bechhoefer, E.; Benbouzid, M. Online automatic diagnosis of wind turbine bearings progressive degradations under real experimental conditions based on unsupervised machine learning. Applied Acoustics 2018, 132, 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Burnecki, K.; Wyłomańska, A.; Beletskii, A.; Gonchar, V.; Chechkin, A. Recognition of stable distribution with Lévy index α close to 2. Physical Review E 2012, 85, 056711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Property | Regime 1 | Regime 2 | Regime 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trend | Constant | Linear | Exponential or Polynomial |

| Scale | Nearly constant | Linearly growing | Exponential or polynomial growing |

| Autodependence of noise | White / Colored | White / Colored | White / Colored |

| Noise distribution | Gaussian | Gaussian | Gaussian |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).