Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

25 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Framework and Guidelines

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Studies reporting in vitro flexural testing of clear aligners.

- Studies comparing different aligner materials or testing methodologies.

- Studies analyzing the influence of clinically relevant factors (e.g. aging, moisture, temperature).

- Peer-reviewed articles in English.

- Studies focusing solely on 3D-printed aligners or non-thermoformed materials.

- Studies on orthodontic retainer materials.

- Clinical studies without an in vitro testing component.

- Reviews, editorials, or opinion pieces.

2.3. Information Sources & Search Strategy

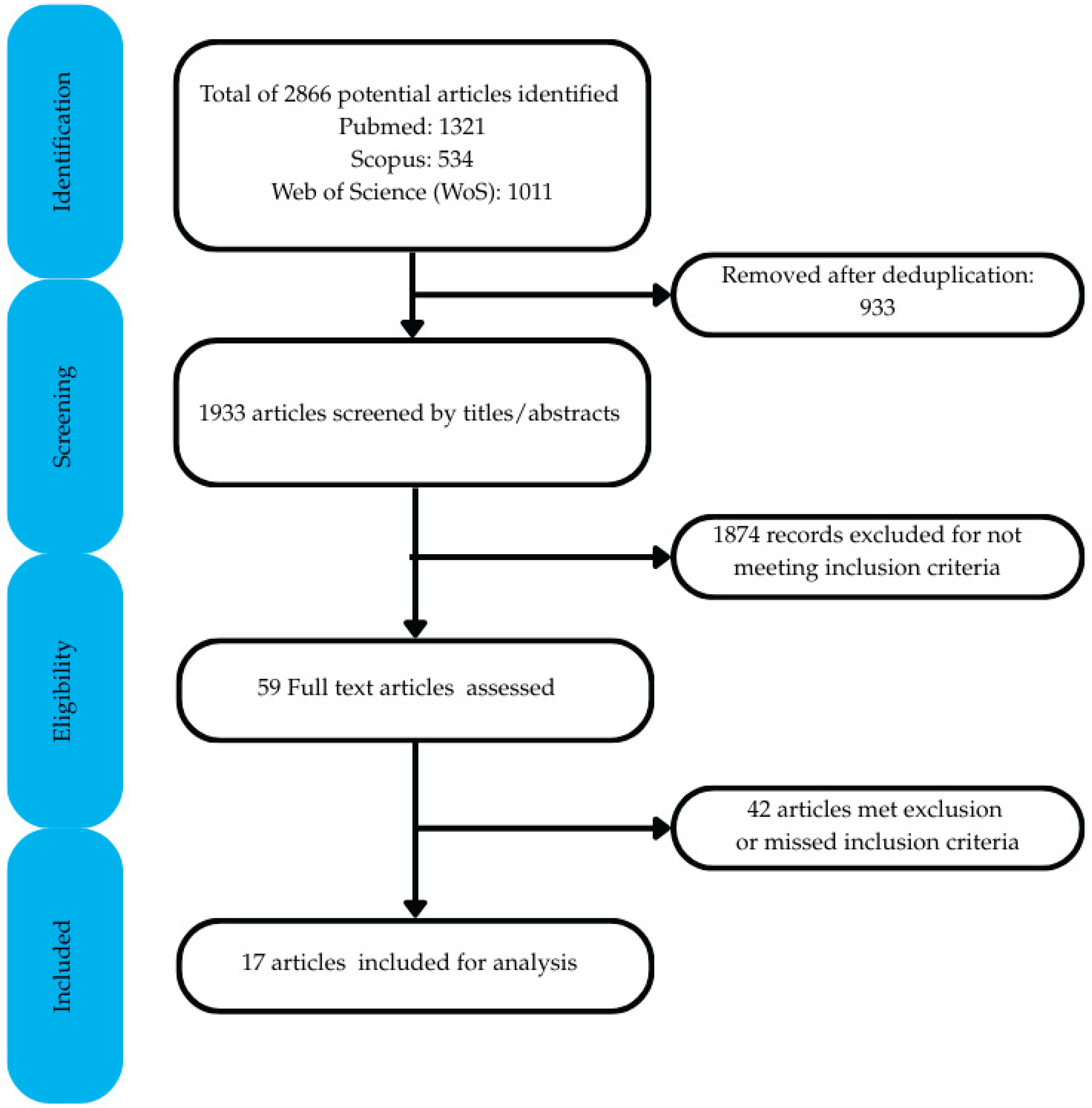

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Risk of Bias

2.6. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection, Risk of Bias and Testing Overview

3.2. Test Parameters

3.2.1. Temperature Conditions

| Albertini et al. [19] | Astasov-Frauenhoffer et al.[25] | Atta et al. [26] | Bhate & Nagesh [27] | Chen et al. [28] | Dalaie et al. [24] | Elkholy et al. (2019) [29] | Elkholy et al. (2023) [30] | Golkhani et al. [23] | Iijima et al. [31] | Kaur et al. [32] | Krishnakumaran et al. [33] | Kwon et al. [22] | Lombardo et al. [18] | Ranjan et al. [20] | Ryu et al. [21] | Yu et al. [34] | |

| Clearly Stated aims / objectives | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Detailed explanation of sample size calculation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Detailed explanation of sampling technique | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Details of comparison group | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Detailed explanation of methodology | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Operator details | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Randomization | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Method of measurement of outcome | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Outcome assessor details | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blinding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Statistical analysis | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Presentation of results | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Total score | 13 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 16 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 11 | 15 | 13 | 12 | 14 | 7 |

| Applied criteria | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Final Score (%) | 54.2 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 54.2 | 50.0 | 66.7 | 58.3 | 54.2 | 58.3 | 54.2 | 58.3 | 45.8 | 62.5 | 54.2 | 50.0 | 58.3 | 29.2 |

| Risk of bias | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | High | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | High |

| First Author, Year | Material tested | Test | Testing machine | Specimen preparation | Testing method | Specimen size | Span length | Testing standard used | Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albertini et al, 2022 [19] | F22 Evoflex (TPU) 0.76mm thickness. F22 Aligner (TPU) 0.76mm thickness. Duran (PET-G) 0.75mm thickness. Erkoloc-Pro (PET-G/TPU) 1mm thickness. Durasoft (TPU/PC) 1.2mm thickness. |

Three-point bending test to measure stiffness, stress-strain curve, yield stress, stress relaxation | Instron 4467 dynamometer with 100N load cell | Nil | Load-deflection test with deformation of 100mm/min to max deflection of 7mm, immersed in bath of distilled water at 37°C | 25 x 50mm raw sheets | 25mm | ASTM D790 | Rapid stress decay and stress relaxation for all materials during first few hours of application before reaching a plateau. Single-layer samples (Duran, F22 Aligner and F22 Evoflex) had similar yield strength, deformation, yield load and stiffness. Double-layer samples (Erkoloc-Pro and Durasoft) had far lower stiffness values and were similar to each other. |

| Astasov-Frauenhoffer et al, 2023 [25] | Naturaligner 0.75 mm thickness. Naturaligner 0.55 mm. Zendura FLX (control) |

Three-point bending test to assess maximum force (initial force), maximum stress (initial stress), and stress-relaxation over a 24 h loading period. | Electromechanical universal testing machine FMT-313 Alluris equipped with a 50N load sensor | Laser cut from thermoformed materials (40W cw CO2 laser), samples were placed in water (unloaded) or in antibacterial solution (loaded for 1 and 6h). | 2 mm vertical deflection to achieve internal elongation of 1.6%, under wet conditions. Force (N) recorded every 59 s for 24 h. Stress ratio between initial stress and the reduced stress was calculated at 8, 12 and 24 h to determine relaxation. | 40 mm x 15 mm | 22 mm | None reported | Antimicrobial loading of samples didn't significantly influence the initial force nor the initial stress. Naturaligner 0.75 mm, antibacterial-loaded for 6h resulted in a lower initial force and initial stress than unloaded and 1h-loaded but similar to Zendura (control). Naturaligner 0.55 mm initial stress and force (loaded and unloaded) was significantly lower than 0.75 mm and Zendura. Zendura had the lowest stress ratio (stress relaxation) at 8, 12 and 24 h. Loading with bioactive molecules for 1h didn't significantly increases stress ratios (relaxation) in samples of Naturaligner 0.75 and 0.55 mm. |

| Atta et al, 2024 [26] | CA Pro (3 layers: soft thermoplastic elastomeric between two hard layers of co-polyester) 0.75 mm. Zendura A (TPU) 0.75 mm. Zendura FLX (3 layers: Thermoplastic soft TPU between two hard layers of co-polyester) 0.75 mm. Graphy Tera Harz TC-85 (3D printed material) 0.6 mm. |

Three-point bending test to measure the maximum force at different temperatures (30 °C, 37 °C, and 45 °C) | Custom-made Orthodontic measurement and simulation system (OMSS) | Samples thermoformed on Biostar device according to manufacturer's guidelines on a custom-made metal mold and scissor cut into strips. TC-85: 3D printed. |

Test in a temperature-controlled cabin, and with 2 mm vertical deflection | 50 x 10 x 0.6 mm | 24 mm | None reported | Highest force measurement for Zendura A (30 °C and 37 °C). No significant differences between all thermoformed materials at 45 °C. TC-85 consistently lowest forces at all temperatures. No significant differences between Zendura FLX and CA Pro at 30 °C, but at 37 °C, CA Pro displayed higher values CA Pro maintained consistent force levels throughout. |

| Bhate & Nagesh, 2024 [27] | Duran (PET-G) 0.75mm thickness. Zendura (PU) 0.75mm thickness. |

Three-point bending test to measure flexural modulus: as-received, thermoformed and thermoformed and aged | Instron E-3000 universal testing machine | 3 groups/material: i. As-received as cut into shape; ii. Thermoformed on metal plate and cut into shape, iii. Thermoformed in metal plate, cut into shape, kept in distilled water 37 °C/24h and thermocycled (200 cycles). |

Loading at cross-head speed of 1 mm/min until fracture. | 40 mm x 9 mm | Not reported | None reported | Duran as-received showed highest flexural strength, and reduced significantly between T0-T1 and T0-T2. Zendura reduced significantly its strength when thermoformed and aged (T2) compared to as-received (T0). Significant flexural strength differences between materials were found in T0 and T1 (duran>zendura) |

| Chen et al, 2023 [28] | Duran T (PET-G). Biolon (PET). Zendura (TPU). All 0.75mm thickness. |

Three-point bending to evaluate changes in strength | Digital push-pull force gauge | Nil | Preload of 10g. Displacement distance of 3mm at speed of 5cm/min. |

10mm x 40mm | 10mm | None reported | For Biolon and Duran T, significant differences between samples soaked in artificial saliva to those soaked in different liquids (wine, Coca-Cola, coffee) on the first and fourth days. For Zendura, no significant differences between samples soaked in beverages and those soaked in artificial saliva. |

| Dalaie et al, 2021 [24] | Duran (PET-G) 1mm thickness. Erkodur (PET-G) 0.8mm thickness. |

Three-point bending test to determine flexural modulus of specimens | UTM model Zwick/Roell Z020 universal testing machine | 3 groups: control, thermoforming, and thermoforming and aging. Thermoforming on 40x7x2mm model and samples of 4x20mm cut for testing. Thermocycling used to simulate intraoral aging |

Loading at rate of 1mm/min with max deflection of 5mm | 4 x 20mm | 11mm | None reported | Flexural modulus decreased significantly after thermoforming (Duran = 88%, Erkodur = 70%). No significant difference between thermoforming and thermoforming and ageing groups (P value=0.190 for Duran, P value = 0.979 for Erkodur). |

| Elkholy et al, 2023 [30] | Duran (PET-G) 0.4, 0.5, 0.625, 0.75mm thicknesses | Three-point bending test to measure force-deflection curves, plastic deformation and stiffness changes after different loading/unloading cycles | 1) Z2.5 universal testing machine with 100N load sensor to measure bending force. 2) custom made 'loading devices' for long term loading. |

Films thermoformed on flat metal plate | 1) bending force measured in Z2.5 machine. 2) samples subjected to 3 loading/unloading cycles in custom machine and short force measurement performed in testing machine after reaching maximum deflection. |

Four 10x40mm specimens cut from each thermoformed film. 3 specimens of each thickness at 3 different loading/unloading modes (n=36). |

8mm | None reported | Force decay values increased significantly after the first loading cycle in 12h/12h loading/unloading mode. Force decay increased over subsequent loading cycles until a nearly constant median residual force level of 9.7% was reached. For 18h/6h and 23h/1h loading/unloading cycles, force decay increased significantly as the length of loading interval increased. |

| Elkholy et al, 2019 [29] | Duran (PET-G) 0.4-0.75mm thicknesses | Three-point bending test to measure deflection forces | Zwick Z2.5 universal testing machine with 100N force sensor | Samples thermoformed on 4 shapes: stainless steel plate, model base plate, round disc, gable roof shaped specimen | Displacement rate of 1mm/min to different distances (0.25 or 0.5mm) | 40mm x 10mm rectangular specimens from untreated and thermoformed sheets | 8-16mm | None reported | Thermoforming led to thinning of samples and a decrease in forces delivered.Max deflection before cracking was 0.20mm for the 0.4mm sample, 0.15mm for 0.5mm, 0.15mm for the 0.625, 0.10mm for the 0.75mm sample.Storage in water for 24hr without loading did not alter deflection forces. Force levels reduced by 50% after storage in water for 24hr with loading, |

| Golkhani et al, 2022 [23] | Duran Plus (PET-G) 0.75mm thickness. Zendura (Polyurethane) 0.75mm thickness. Essix ACE (Copolyester) 0.75mm thickness. Essix PLUS (Copolyester) 0.9mm thickness. |

Three-point bending test before and after thermoforming to measure thickness changes and modulus of elasticity | Zwick/Roell ZmartPro universal testing machine | 1.untreated raw sheets x 10. 2.10 specimens deep drawn on a master plate dimension 10 × 10 × 50 mm3. Specimens cut from upper side and lateral walls and then tested. |

Central displacement of 0.25, 0.50, 2.00mm at lengths of 8, 16, 24mm | Test 1 - 10 specimens 50 x 10mm of each material. Test 2 - 10 specimens cut from upper side and side of cuboid with 50 x 10mm dimensions. |

8mm, 16mm, 24mm | None reported | Force reduction for samples from upper side was 50% and 90% for the side walls. Minor influence of span distance. Reductions in modulus of elasticity from as-received to thermoformed samples were statistically significant for Duran Plus (2746MPa to 2189MPa) and Essix PLUS (1869MPa to 1144MPa). Reduction in E values for Essix ACE was not statistically significant (2274MPa to 1798MPa). Zendura showed a reduction in E from 2218MPa to 1718MPa. |

| Iijima et al, 2015 [31] | Duran (PET-G) 0.5mm thickness. Hardcast (Polypropylene) 0.4mm thickness. SMP MM (polyurethane) 0.5mm thickness. |

Three-point bending test to determine load-deflection curves, elastic modulus, yield strength, shape recovery | EZ Test universal testing machine | 1. specimens prepared. 2. specimens heat treated at Tg + 25°C. 3. specimens inserted in straight slot formed in gypsum block. |

1.specimens loaded at 25°C to 3mm deflection at 1mm/min. 2.specimens heated to 100°C using dry heat steriliser to observe shape memory. |

Specimens with dimensions of 1mm x 0.4 or 0.5mm and 20mm in length | 12mm | ANSI/ADA Specification No. 32 | Elastic moduli and yield strengths similar for Duran, SMP MM 6520 and SMP MM 9520. Elastic moduli and yield strengths for Hardcast and SMP MM 3520 much lower than the other materials. For shape memory tests, slight residual deflection was observed for Hardcast, SMP MM 3520 and SMP MM 9520. Duran and SMP MM 6520 showed large residual deflection. |

| Kaur et al, 2023 [32] | Essix A+ (PET) 0.75mm thickness. Taglus (PET-G) 0.75mm thickness. Zendura (PU) 0.75mm thickness. |

Three-point bending test on raw and thermoformed samples to determine flexural modulus from force-displacement curve | ElectroPlus E3000 universal testing machine | Samples thermoformed using Biostar machine on stone simplified dental arch shape following manufacturer’s recommendations | Displacement rate of 2mm/min | 5 x 40mm samples cut from thermoformed and raw sheets. 60 samples (10 raw and 10 thermoformed sheets per material). |

24mm | ASTM D790-03 | Flexural modulus for Zendura increased during thermoforming (2264.72MPa to 2913.46MPa). Insignificant increase in flexural modulus after thermoforming for Essix A+ (2196.46MPa to 2412.66MPa). Flexural modulus for Taglus decreased from 2462.36MPa to 2457.95MPa. |

| Krishnakumaran et al, 2023 [33] | Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) 1 mm Thickness (manufacturer not mentioned) | Three-point bending test to determine tensile strength and elastic modulus: as-received (TPU), nanocoated CMC-CHI (Coated TPU), and nanocoated CMC-CHI and thermoformed (Thermoformed coated TPU) | Universal testing machine (no further details) | 3 groups: i. Control (TPU), ii. Coated with carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) chitosan (CHI), and iii. Coated and thermoformed TPU |

Loading at 25 °C, with a deflection of 3 mm applied at a strain rate of 1 mm/min | 20 mm x 1 mm x 1 mm | 15 mm | None reported | Elastic modulus and tensile strength increased when TPU was coated with carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and Chitosan (CHI). However, thermoforming coated-specimens appeared to counteract the effects of higher mechanical properties due to coating. |

| Kwon et al, 2008 [22] | Essix A+ 0.5, 0.75, 1mm thicknesses. Essix ACE 0.75mm thickness. Essix C+ 1mm thickness. |

Three-point bending recovery test to measure force delivery properties during recovery from deflection | Instron model 4465 | Materials thermoformed on stone model 30 x 60 x 10mm | 1.specimen deflected vertically 2mm at 5mm/min. 2. force delivery properties during recovery from deflection recorded. 3.thermocycled between 5°C and 55°C and test repeated. |

Specimens of 20 x 50mm cut out (10 specimens for each material) | 24mm | None reported | Amount of delivered force decreased after thermocycling. No significant difference in the force delivery properties after thermocycling when deflection was in the range of optimum force delivery (0.2 – 0.5mm).A mount of delivered force generally decreased after repeated load cycling. |

| Lombardo et al, 2017 [18] | F 22 Aligner (TPU) 0.75mm thickness Duran (PET-G) 0.75mm thickness. Erkoloc-Pro (PET-G/TPU) 1mm thickness. Durasoft (TPU/PC) 1.2mm thickness. |

Three-point bending test to measure stiffness, stress-strain curve, yield stress, stress relaxation | Instron 4467 dynamometer with 100N load cell | Nil | Preload 1N, load-deflection test with deformation of 100mm/min to max deflection of 7mm, immersed in bath of distilled water at 37°C | 25mm x 50mm raw sheets | 25mm | ASTM D790 | Stress relaxation and stress decay for each sample was high during the first 8 hours and then plateaued. Yield strength test showed single layer samples (Duran and F22 aligner) had similar stiffness values (2.9 and 2.7 MPa). Double layer samples (Erkoloc-Pro and Durasoft) values of 0.6MPa. |

| Ranjan et al, 2020 [20] | Duran (PET-G) 0.75mm thickness. Erkodur (PET-G/TPU) 0.8mm. Track (PET-G) 0.8mm. |

Three-point bending test to assess load deflection, stress relaxation and yield strengths | Star universal testing machine | Nil | Preload of 1N. Displacement rate of 100mm/min to max deflection of 7mm. |

25mm x 50mm | 25mm | None reported | Duran had more yield load and yield strength than Erkodur and Track. Duran had greater total initial stress and highest decay during first 24 hours. Erkodur had lowest initial and final stress values. Duran had higher percentage of stress relaxation. |

| Ryu et al, 2018 [21] | Duran (PET-G) 0.5, 0.75, and 1.0mm. Essix A+ (Copolyester) 0.5, 0.75, and 1mm. eCligner (PET-G) 0.5, and 0.75mm. Essix ACE (Copolyester) 0.75, and 1mm. |

Three-point bending test to measure flexural modulus before and after thermoforming | Instron model 3366 universal testing machine | Samples thermoformed at 220°C on 8.5mm x 7mm x 2mm block | Strain interval of 0.5mm from 0.5mm to 1mm at crosshead speed of 5mm/min. | 40mm x 9mm specimens cut out for analysis (5 specimens of each material and thickness) | 24mm | ISO 20795-2 (2013) | Flexural force for all materials and thicknesses significantly lowered after thermoforming. Flexural modulus after thermoforming: 1: 0.5mm samples: significant increase. 2: 0.75mm: Duran and eCligner increased significantly, no significant changes for Essix A+ and Essix ACE. 3: 1mm: significant decrease for all materials. |

| Yu et al, 2022 [34] | Thermoplastic polyurethane (no further description) | Three-point bending test to determine flexural modulus and stress/strain curve | Universal testing machine Instron 5943 | Not reported | Cross-head speed was 0.5 mm/min | Not reported | Not reported | None reported | TPU achieved a bending modulus of 2511 Mpa |

3.2.2. Thermoforming Protocols

3.2.3. Span Lengths

3.2.4. Deflection Levels

3.3. Materials

3.4. Investigated Influencing Factors

3.4.1. Thermoforming Effects

3.4.2. Liquid Absorption

3.4.3. Temperature Changes

3.4.4. Constant and Interval Loading

3.4.5. Influence of Aligner Thickness

4. Discussion

4.1. Testing

4.2. Test Parameters

4.2.1. Temperature Conditions

4.2.2. Thermoforming Protocols

4.2.3. Span Length

4.2.4. Deflection Levels

4.3. Materials

4.4. Influencing Factors

4.4.1. Thermoforming

4.4.2. Liquid Absorption

4.4.3. Temperature Changes

4.4.4. Constant and Interval Loading

4.4.5. Aligner Thickness

4.5. Other Factors

4.6. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAT | Clear aligner therapy |

| FAT | Fixed Appliance therapy |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PET-G | Polyethylene terephthalate glycol |

| PU | Polyurethane |

| TPU | Thermoplastic polyurethane |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PC | Polycarbonate |

| CAD-CAM | Computer-aided design/Computer-aided manufacturing |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| Tg | Glass transition temperature |

| 3-PBT | Three-point bending test |

References

- Lagravère, M.O.; Flores-Mir, C. The Treatment Effects of Invisalign Orthodontic Aligners. The Journal of the American Dental Association 2005, 136, 1724–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, B.; Padmanabhan, S.; Srinivasan, S. Comparative Evaluation of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Clear Aligners – a Systematic Review. Evid Based Dent 2024, 25, 53–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesling, H.D. Coordinating the Predetermined Pattern and Tooth Positioner with Conventional Treatment. American Journal of Orthodontics and Oral Surgery 1946, 32, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliades, T.; Athanasiou, A.E. Orthodontic Aligner Treatment: A Review of Materials, Clinical Management, and Evidence; Thieme: Stuttgart New York Delhi Rio de Janeiro, 2021; ISBN 978-3-13-241148-7. [Google Scholar]

- Beers, A.; Choi, W.; Pavlovskaia, E. Computer-assisted Treatment Planning and Analysis. Orthod Craniofacial Res 2003, 6, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, L.; Kaur, H.; Fagundes, N.C.F.; Romanyk, D.; Major, P.; Flores Mir, C. Effectiveness of Clear Aligner Therapy for Orthodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review. Orthod Craniofacial Res 2020, 23, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennessy, J.; Al-Awadhi, E.A. Clear Aligners Generations and Orthodontic Tooth Movement. J Orthod 2016, 43, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Jiang, Y.-N.; Chu, F.-T.; Lu, P.-J.; Tang, G.-H. A Cone-Beam Computed Tomographic Study Evaluating the Efficacy of Incisor Movement with Clear Aligners: Assessment of Incisor Pure Tipping, Controlled Tipping, Translation, and Torque. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2021, 159, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalampakis, O.; Iliadi, A.; Ueno, H.; Oliver, D.R.; Kim, K.B. Accuracy of Clear Aligners: A Retrospective Study of Patients Who Needed Refinement. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2018, 154, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, G.; Parrini, S.; Castroflorio, T.; Deregibus, A.; Debernardi, C.L. Efficacy of Clear Aligners in Controlling Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Systematic Review. The Angle Orthodontist 2015, 85, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, T. Clear Aligners in Orthodontic Treatment. Australian Dental Journal 2017, 62, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortona, A.; Rossini, G.; Parrini, S.; Deregibus, A.; Castroflorio, T. Clear Aligner Orthodontic Therapy of Rotated Mandibular Round-Shaped Teeth: A Finite Element Study. The Angle Orthodontist 2020, 90, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Moghrabi, D.; Salazar, F.C.; Pandis, N.; Fleming, P.S. Compliance with Removable Orthodontic Appliances and Adjuncts: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2017, 152, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Bai, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhang, Y. Preparation and Characterization of Thermoplastic Materials for Invisible Orthodontics. Dental Materials Journal 2011, 30, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapila, S.; Sachdeva, R. Mechanical Properties and Clinical Applications of Orthodontic Wires. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 1989, 96, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization ISO 20795-2:2013. Dentistry - Base Polymers. Part 2: Orthodontic Base Polymers; 2013.

- Sheth, V.H.; Shah, N.P.; Jain, R.; Bhanushali, N.; Bhatnagar, V. Development and Validation of a Risk-of-Bias Tool for Assessing in Vitro Studies Conducted in Dentistry: The QUIN. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2024, 131, 1038–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, L.; Martines, E.; Mazzanti, V.; Arreghini, A.; Mollica, F.; Siciliani, G. Stress Relaxation Properties of Four Orthodontic Aligner Materials: A 24-Hour in Vitro Study. The Angle Orthodontist 2016, 87, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, P.; Mazzanti, V.; Mollica, F.; Pellitteri, F.; Palone, M.; Lombardo, L. Stress Relaxation Properties of Five Orthodontic Aligner Materials: A 14-Day In-Vitro Study. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Biradar, A.K.; Patel, A.; Varghese, V.; Pawar, A.; Kulshrestha, R. Assessment of the Mechanical Properties of Three Commercially Available Thermoplastic Aligner Materials Used for Orthodontic Treatment. Iran J Ortho 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.-H.; Kwon, J.-S.; Jiang, H.B.; Cha, J.-Y.; Kim, K.-M. Effects of Thermoforming on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Thermoplastic Materials for Transparent Orthodontic Aligners. Korean J Orthod 2018, 48, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.-S.; Lee, Y.-K.; Lim, B.-S.; Lim, Y.-K. Force Delivery Properties of Thermoplastic Orthodontic Materials. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2008, 133, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkhani, B.; Weber, A.; Keilig, L.; Reimann, S.; Bourauel, C. Variation of the Modulus of Elasticity of Aligner Foil Sheet Materials Due to Thermoforming. J Orofac Orthop 2022, 83, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalaie, K.; Fatemi, S.M.; Ghaffari, S. Dynamic Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Clear Aligners after Thermoforming and Aging. Prog Orthod. 2021, 22, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astasov-Frauenhoffer, M. Antimicrobial and Mechanical Assessment of Cellulose-Based Thermoformable Material for Invisible Dental Braces with Natural Essential Oils Protecting from Biofilm Formation.

- Atta, I.; Bourauel, C.; Alkabani, Y.; Mohamed, N.; Kim, H.; Alhotan, A.; Ghoneima, A.; Elshazly, T. Physiochemical and Mechanical Characterisation of Orthodontic 3D Printed Aligner Material Made of Shape Memory Polymers (4D Aligner Material). Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2024, 150, 106337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhate, M.; Nagesh, S. Assessment of the Effect of Thermoforming Process and Simulated Aging on the Mechanical Properties of Clear Aligner Material. Cureus 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-M.; Huang, T.-H.; Ho, C.-T.; Kao, C.-T. Force Degradation Study on Aligner Plates Immersed in Various Solutions. Journal of Dental Sciences 2023, 18, 1845–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkholy, F.; Schmidt, S.; Amirkhani, M.; Schmidt, F.; Lapatki, B.G. Mechanical Characterization of Thermoplastic Aligner Materials: Recommendations for Test Parameter Standardization. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkholy, F.; Schmidt, S.; Schmidt, F.; Amirkhani, M.; Lapatki, B.G. Force Decay of Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol Aligner Materials during Simulation of Typical Clinical Loading/Unloading Scenarios. J Orofac Orthop 2023, 84, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, M.; Kohda, N.; Kawaguchi, K.; Muguruma, T.; Ohta, M.; Naganishi, A.; Murakami, T.; Mizoguchi, I. Effects of Temperature Changes and Stress Loading on the Mechanical and Shape Memory Properties of Thermoplastic Materials with Different Glass Transition Behaviours and Crystal Structures. EORTHO 2015, 37, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Khurelbaatar, T.; Mah, J.; Heo, G.; Major, P.W.; Romanyk, D.L. Investigating the Role of Aligner Material and Tooth Position on Orthodontic Aligner Biomechanics. J Biomed Mater Res 2023, 111, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumaran, M.; Mahalingam, J.; Arumugam, S.; Prabhu, D.; Parameswaran, T.M.; Krishnan, B. Evaluation of the Effect of Nanocoating on Mechanical and Biofilm Formation in Thermoplastic Polyurethane Aligner Sheets. Contemporary Clinical Dentistry 2023, 14, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, G.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, J.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Huang, L.; Pan, X.; Ding, J. ‘Invisible’ Orthodontics by Polymeric ‘Clear’ Aligners Molded on 3D-Printed Personalized Dental Models. Regenerative Biomaterials 2022, 9, rbac007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.; Watts, J.; Hood, J.; Burritt, D. Intra-Oral Temperature Variation over 24 Hours. European Journal of Orthodontics 1999, 21, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, C.W.; Spence, D.; Laird, W.R.E. Intra-oral Temperatures during Function. J of Oral Rehabilitation 2005, 32, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstone, C.J. The Biophysics of Bone Remodeling during Orthodontics-Optimal Froce Considerations-. In The biology of tooth movement; CRC Press, 1989; pp. 321–333.

- Proffit, W.R.; Fields, H.W.; Larson, B.E.; Sarver, D.M. Contemporary Orthodontics; Sixth edition.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-323-54387-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, J.; Ledoux, W.; McMinn, R. Essix Appliances: Minor Tooth Movement with Divots and Windows. J Clin Orthod 1994, 28, 659–663. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, R.L.; Miller, R.J.; Vlaskalic, V. The Invisalign System in Adult Orthodontics: Mild Crowding and Space Closure Cases.

- Elkholy, F.; Schmidt, F.; Jäger, R.; Lapatki, B.G. Forces and Moments Delivered by Novel, Thinner PET-G Aligners during Labiopalatal Bodily Movement of a Maxillary Central Incisor: An in Vitro Study. The Angle Orthodontist 2016, 86, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihssen, B.A.; Willmann, J.H.; Nimer, A.; Drescher, D. Effect of in Vitro Aging by Water Immersion and Thermocycling on the Mechanical Properties of PETG Aligner Material. J Orofac Orthop 2019, 80, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschang, P.H.; Shaw, S.G.; Ross, M.; Crosby, D.; Campbell, P.M. Comparative Time Efficiency of Aligner Therapy and Conventional Edgewise Braces. The Angle Orthodontist 2014, 84, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haouili, N.; Kravitz, N.D.; Vaid, N.R.; Ferguson, D.J.; Makki, L. Has Invisalign Improved? A Prospective Follow-up Study on the Efficacy of Tooth Movement with Invisalign. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2020, 158, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search string | Results found |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ("Clear aligners" OR Invisalign OR thermoform* OR orthodontic* OR "thermoplastic appliance*" OR "orthodontic retainer*" OR "orthodontic splint*") AND ("Flexural Strength"[MeSH] OR "three-point bending" OR "three point bending" OR "four-point bending" OR "four point bending" OR "biaxial flexural" OR "mechanical properties" OR "flexural modulus" OR "elastic modulus") AND (Journal Article[PT]) AND (English[lang]) | 1321 Articles |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "clear aligners" OR invisalign OR thermoform* OR orthodontic* ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "flexural strength" OR "three-point bending" OR "three point bending" OR "four-point bending" OR "four point bending" OR "biaxial flexural" OR "mechanical properties" OR "flexural modulus" OR "elastic modulus" ) AND SUBJAREA ( mater OR dent OR eng ) AND DOCTYPE ( ar ) AND LANGUAGE ( english ) | 534 Articles |

| WoS | TS=("clear aligners" OR Invisalign OR thermoform* OR orthodontic*) AND TS=("flexural strength" OR "three-point bending" OR "three point bending" OR "four-point bending" OR "four point bending" OR "biaxial flexural" OR "mechanical properties" OR "flexural modulus" OR "elastic modulus") AND WC=("Materials Science" OR "Dentistry, Oral Surgery & Medicine") AND DT=(Article) |

1011 Articles |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).