1. Introduction

The development of renewable energy sources has become increasingly imperative in light of the significant rise in global energy demand in recent years. Projections indicate that total energy consumption is expected to surpass 30 terawatts (TW) by 2050 [

1]. Hydrogen, considered a green energy carrier, offers numerous environmental benefits due to its clean and sustainable nature. It comes from various sources, has high energy density, and supports diverse applications. Moreover, it holds the potential to replace fossil fuels, thereby mitigating the critical energy and environmental challenges currently confronting society [

2,

3]. The Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) has attracted considerable attention from researchers due to its highly efficient hydrogen production mechanism and its environmentally friendly, non-polluting process [

4]. Catalysts are essential in the catalytic process as they lower energy barriers, accelerate reaction rates, and optimize pathways for efficient charge transfer, which significantly impacts overall performance [

5,

6]. The prevailing commercial HER catalyst is Pt/C. However, its widespread use in industrial applications is limited by the limited availability of Pt and the high costs associated with its synthesis and application [

7,

8]. Consequently, it is crucial to develop alternative materials that are cost-effective, exhibit strong chemical stability, and demonstrate high catalytic activity to overcome this challenge [

9].

In the development of catalysts for HER, a wide range of materials have been investigated. Transition metal compounds are extensively utilized in this domain due to their distinctive electronic structure and modifiable elemental composition [

10]. From an electronic structure perspective, transition metal atoms have unfilled d orbitals, which allow electrons to move between these orbitals. This distinctive electronic configuration enables transition metal atoms to form various bonding modes with reactant molecules, facilitating effective adsorption and dissociation of the reactants [

11,

12]. This, in turn, reduces the activation energy of the reaction and enhances the rate of catalytic hydrogen evolution.

In recent years, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have become some of the most promising non-precious metal HER catalysts due to their large specific surface area and adjustable electronic structure [

13,

14]. In terms of structural properties, they possess a characteristic layered architecture, with the fundamental constituents comprising alternating layers of transition metal and chalcogen atoms. This structural arrangement endows the material with advantageous electrical and other properties [

15]. Furthermore, the electrocatalytic performance of TMDs can be effectively tuned by adjusting the transition metal-to-sulfur ratio, the arrangement of metal atoms, and the crystal structure of the sulfides. This optimization ensures optimal interaction with the hydrogen evolution reaction, thereby meeting the performance requirements for HER in various practical applications [

16].

Among the numerous transition metal sulfides, molybdenum disulfide (MoS

2), a prototypical layered transition metal disulfide, stands out due to its distinctive electronic and crystal structures, excellent stability, and the cost-effectiveness of its constituent elements, thereby attracting considerable attention. The exploration of MoS

2 began in 1977 when Tributsch and Bennett first synthesized bulk MoS

2 and evaluated its electrochemical properties [

17]. Bulk MoS

2 was found to be inactive for HER, a result attributed to its limited surface area. The individual layers are loosely connected by van der Waals interactions, which reduces the exposure of active sites and restricts conductivity.

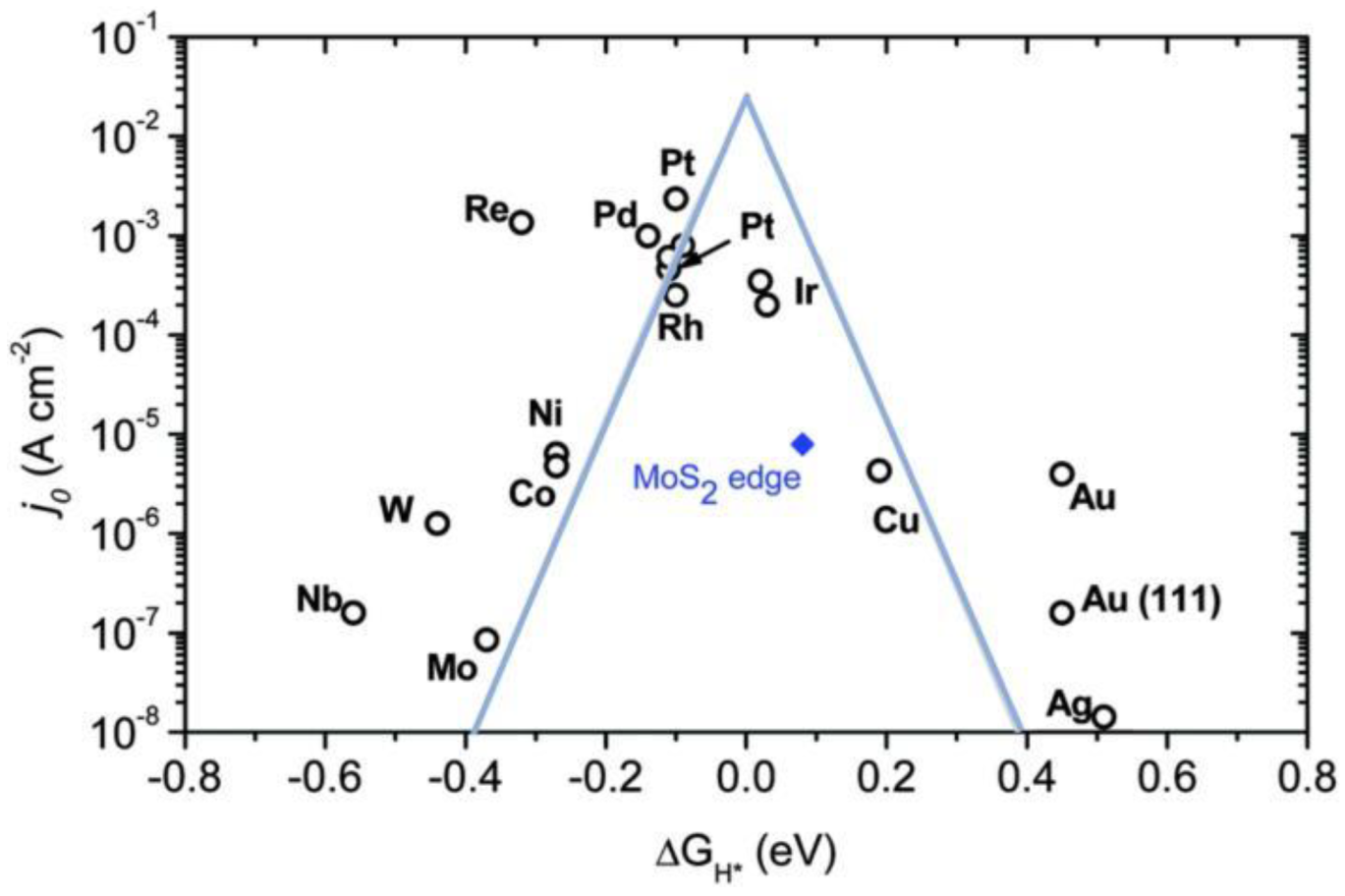

Subsequent studies by Hinnemann and colleagues demonstrated that nanostructured MoS

2 exhibited enhanced electrocatalytic activity, which was ascribed to its increased specific surface area [

18]. The increased surface exposure of the edge sites, which were previously buried within bulk MoS

2, resulted in a substantial increase in the quantity of active sites [

19]. Consequently, the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution activity was significantly improved. Additionally, nanostructured MoS

2, with its high specific surface area and excellent chemical stability, contains numerous reactive unsaturated S and Mo atoms that serve as active sites. These atoms interact with hydrogen to catalyze the HER, accounting for the majority of MoS

2's catalytic activity. The volcano plot of the exchange current density, obtained from extensive experiments, is presented [

20]. The Mo-edge of MoS

2 exhibits moderate hydrogen adsorption energy and hydrogen coverage strength, which contributes to its excellent HER activity. This finding provides an important theoretical foundation for the subsequent exploration and innovation of high-performance HER catalysts based on MoS

2 [

21].

Figure 1.

Volcano plot of the experimentally measured exchange current density as a function of the Gibbs free energy of adsorbed atomic hydrogen, calculated using DFT (from ref. [

20], with permission).

Figure 1.

Volcano plot of the experimentally measured exchange current density as a function of the Gibbs free energy of adsorbed atomic hydrogen, calculated using DFT (from ref. [

20], with permission).

However, MoS

2 is a semiconductor with relatively poor intrinsic conductivity, and the electron transport rate within the material is slow, leading to low electron transfer efficiency during the HER process [

22]. The poor intrinsic conductivity makes it difficult for some active sites, especially those located within the material or between layers, to fully participate in the reaction. Owing to the difficulty in electron transport, the catalytic activity of these sites cannot be effectively utilized, which reduces the overall catalytic efficiency of the material.

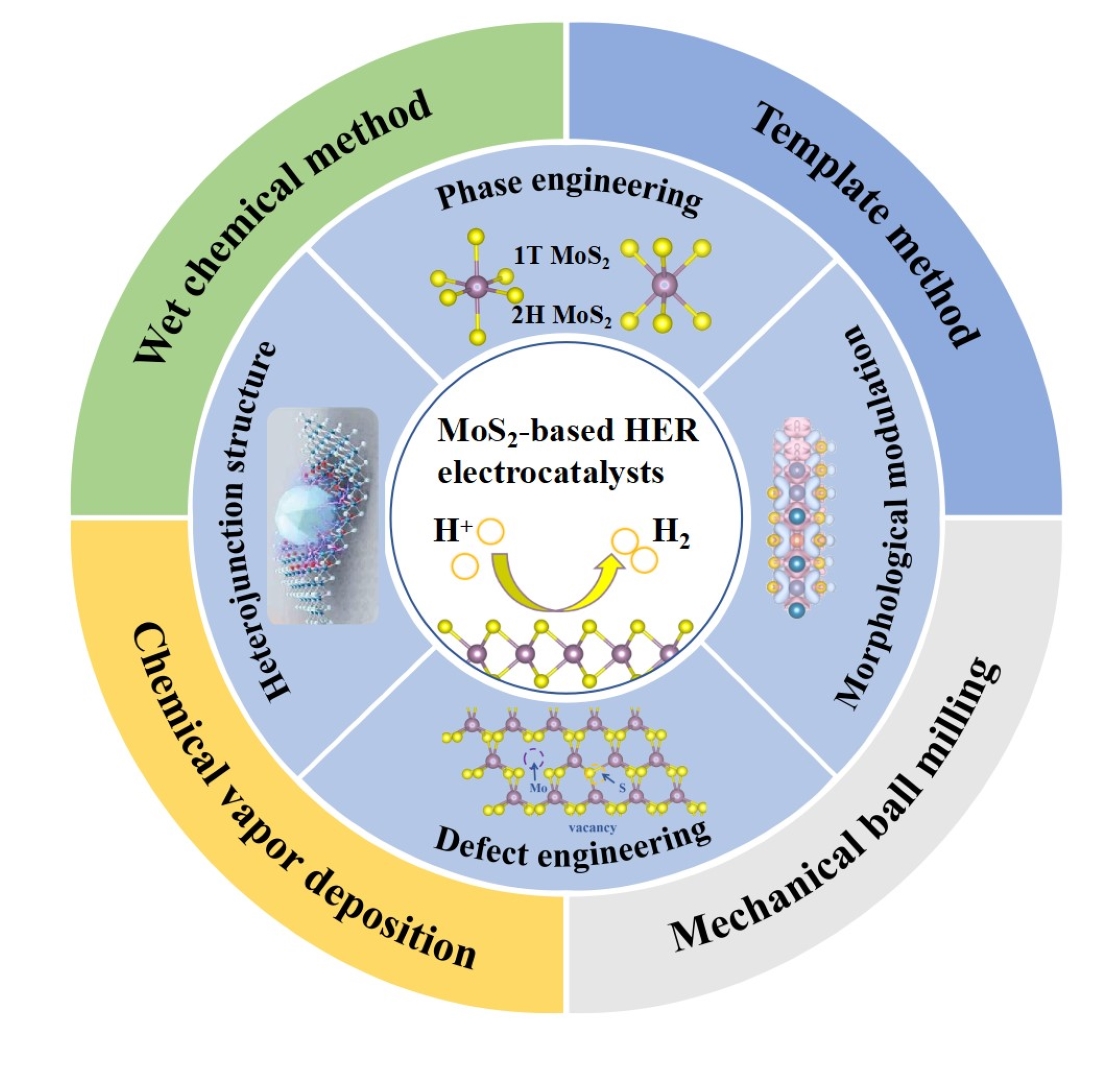

To optimize the HER electrocatalytic activity of MoS2, researchers have employed various strategies, including morphology design, defect introduction, phase engineering, and the construction of heterostructures. In this context, it is crucial to systematically review the synthetic methods and performance enhancement strategies of MoS2, as well as to deeply explore the mechanisms by which these strategies improve HER performance. The objective of this article is twofold: first, to offer a comprehensive and systematic overview of the synthetic methods used in MoS2 production; and second, to conduct an in-depth investigation into the mechanisms underlying the performance-enhancing strategies employed in this process. The synthesis methods summarized in this study provide various approaches for producing high-quality and high-activity MoS2 materials. Additionally, the performance enhancement strategies and their underlying mechanisms can aid in unlocking the potential of MoS2 for HER, overcoming its current limitations, and advancing its development towards improved efficiency and stability.

This review traces the latest scientific progress in the fabrication of highly efficient and stable MoS2-based nanostructured HER electrocatalysts using various synthetic methods. It offers an overview of the current research on MoS2-based HER catalysts, including their synthesis techniques. Furthermore, it provides a comprehensive discussion of the electrocatalytic performance mechanisms of MoS2 with different morphologies and modification strategies, while also offering insights into its future development.

This article begins with a thorough introduction to the crystal and energy-band structure of MoS2, Subsequently analyzing its synthesis strategies in-depth. It then focuses on the preparation approaches aimed at designing structural parameters and optimizing the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance. The preparation strategies are summarized, and experiments conducted over the past three years are discussed. These experiments incorporate advanced characterization techniques to investigate the hydrogen evolution reaction in water electrolysis. Finally, the challenges and opportunities associated with MoS2-based electrocatalysts for hydrogen production are thoroughly examined, and future academic perspectives are provided to enhance their electrocatalytic performance. This is expected to contribute to the advancement of high-performance catalysts for green hydrogen production.

The article begins with a comprehensive discussion of the crystal and energy-band structure of MoS2, followed by a detailed analysis of its synthesis strategies. It then shifts focus to the preparation methods, which are designed to optimize structural parameters and enhance the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance. The preparation strategies are summarized, and experiments conducted over the past three years are detailed. These experiments integrate advanced characterization techniques to investigate the water-electrolysis process for hydrogen evolution. Finally, the challenges and opportunities associated with MoS2-based electrocatalysts for hydrogen production are comprehensively discussed, and future academic perspectives are offered to improve their electrocatalytic performance.

2. Crystal and Band Structure of MoS2

Transition metal-sulfur compounds are classified as MX

2-type semiconductors, where M represents a transition metal (e.g., Mo, W) and X denotes a chalcogen element (e.g., S, Se, or Te). These compounds generally possess a layered structure, with each layer consisting of three atomic sub-layers. In these layers, transition metal atoms are sandwiched between two sulfur (or chalcogen) atoms, forming structures that can be considered as van der Waals solids [

23]. This structural configuration facilitates the penetration of hydrogen ions into the interlayer, thereby enabling the reaction. In the context of HER, the layered structure offers an ideal reaction site for H

2 production, promoting the adsorption and desorption of hydrogen atoms.

As a typical transition metal sulfide, MoS

2 features a layered hexagonal structure with distinct S-Mo-S layers. The Mo atoms create covalent bonds with six neighboring S atoms, and there are no unsaturated bonds between the layers [

24]. The Mo and S atoms within the layer are strongly bonded to each other by covalent bonds. This layered configuration results in two distinct exposed surfaces: the basal surface, which is associated with interlayer exfoliation, and the prismatic surface, which is linked to intra-layer Mo-S bonding exfoliation. This unique structural attribute endows MoS

2 with improved electrical conductivity and stability, thereby facilitating the continuous and efficient execution of the hydrogen evolution reaction. Therefore, the performance remains stable, without significant degradation due to the intrinsic properties of the material.

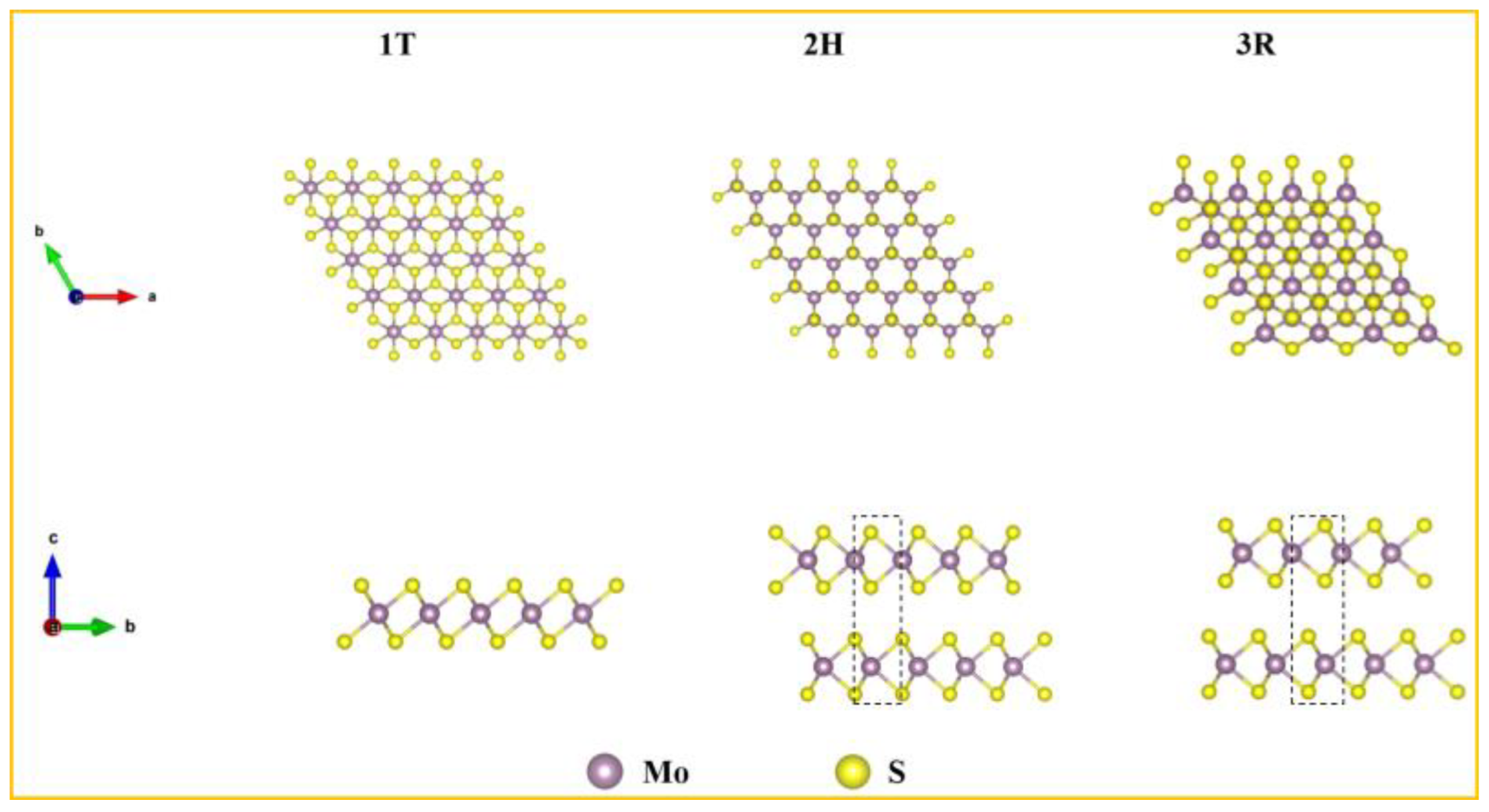

From a crystallographic perspective, MoS

2 can exist in three distinct phases, as shown in: octahedral (1T), hexagonal (2H), rhombohedral (3R). These phases exhibit significant differences in their crystal structures, electronic properties, and stability. 1T-MoS

2 exhibits a metallic character and adopts an "A-B-C" stacking mode, with the d orbital splitting into d

Z2, d

X2−Y2, d

XY, d

XZ, d

YZ [

25]. 2H-MoS

2 is the most common and stable phase with semiconducting properties. It adopts the "A-B-A" stacking way, also with the d orbital splitting into d

Z2, d

X2−Y2, d

XY, d

XZ, d

YZ. 3R-MoS

2 is structurally similar to 2H-MoS

2 but has a distinct stacking configuration. Each unit cell of 3R MoS

2 consists of three layers aligned along the c axis, and this configuration can be converted into the 2H phase through a phase transition [

26].

In the context of electrolytic water splitting for hydrogen production, the catalytic active sites of 2H-MoS

2 are predominantly concentrated at the edge planes. Conversely, 1T-MoS

2 shows a broader distribution of active sites across both the basal and edge planes, resulting in enhanced conductivity [

27]. The present study primarily focuses on increasing the number of active sites or enhancing the catalytic activity per site of 2H-MoS

2, as well as improving the stability of 1T-MoS

2.

Figure 2.

Three different MoS2 crystal phases.

Figure 2.

Three different MoS2 crystal phases.

MoS

2 has attracted significant attention because of its unique and adjustable band structure. Near the high-symmetry points of the Brillouin zone, the peak of the valence band and the trough of the conduction band exhibit distinct dispersion relations, which are crucial for its catalytic properties, particularly in HER. This suggests a strong and specific relationship between the energy and momentum of electrons. The conduction band of MoS

2 is positioned at an energy level that facilitates efficient electron transfer to protons during HER. From the perspective of atomic orbitals, the conduction and valence bands of MoS

2 primarily result from the hybridization of molybdenum's d orbitals and sulfur's p orbitals. It is important to note that at different points in the Brillouin zone, the contribution and interaction strength between Mo-d orbitals and S-p orbitals vary, producing notable distinctions in the shape and energy distribution of the energy bands [

28].

Bulk MoS

2 is an indirect bandgap semiconductor with a bandgap of 1.29 electron volts (eV). However, as the number of MoS

2 layers decreases, its bandgap gradually increases due to the enhanced quantum confinement effect. In contrast, single-layer MoS

2 exhibits a direct bandgap with a width of 1.8 eV [

18]. When the bandgap is too large and the energy expenditure required for electron transition is excessively high, the electron transfer rate is restricted, resulting in sluggish HER kinetics. Conversely, if the bandgap is too small, the catalyst's electronic structure may become overly stable, which is detrimental to hydrogen atom adsorption and activation. The bandgap of MoS

2 allows it to strike a balance between electron transfer and adsorption activation requirements, thus exhibiting good HER activity. Theoretical calculations demonstrate that the band structure of MoS

2 is amenable to tuning through doping and strain application, which can further optimize its properties [

29].

Sun et al. found through theoretical and experimental characterization that the adjustment of the electronic band structure of MoS

2 is related to the regulation of HER activity [

30]. They introduced a Pd-Re dopant to bring the new band closer to the Fermi level, increasing the number of bands around the Fermi level, which in turn improves the hydrogen adsorption strength of the basal S site. At low doping levels of metal atoms, the distance between Pd and Re atoms is relatively large, and the synergistic effect between the two heteroatoms can be neglected. However, when the distance between them decreases, the double-dopant substitutes adjacent Mo sites, promoting the formation of Pd-S-Re at the S site. The synergistic effect between the adjacent heteroatoms has been shown to enhance the HER activity of the basal S site, achieving an optimal hydrogen adsorption Gibbs free energy (ΔG

H* = 0 eV). This doping process has been shown to modify the electronic structure, induce strain in MoS

2, alter the bandgap width and band edge positions, and ultimately enhance the catalytic performance.

3. Synthesis Strategy of MoS2

In this chapter, we have explored the recently reported strategies for synthesizing MoS2, including mechanical ball milling, chemical vapor deposition, wet chemical synthesis, and the template method.

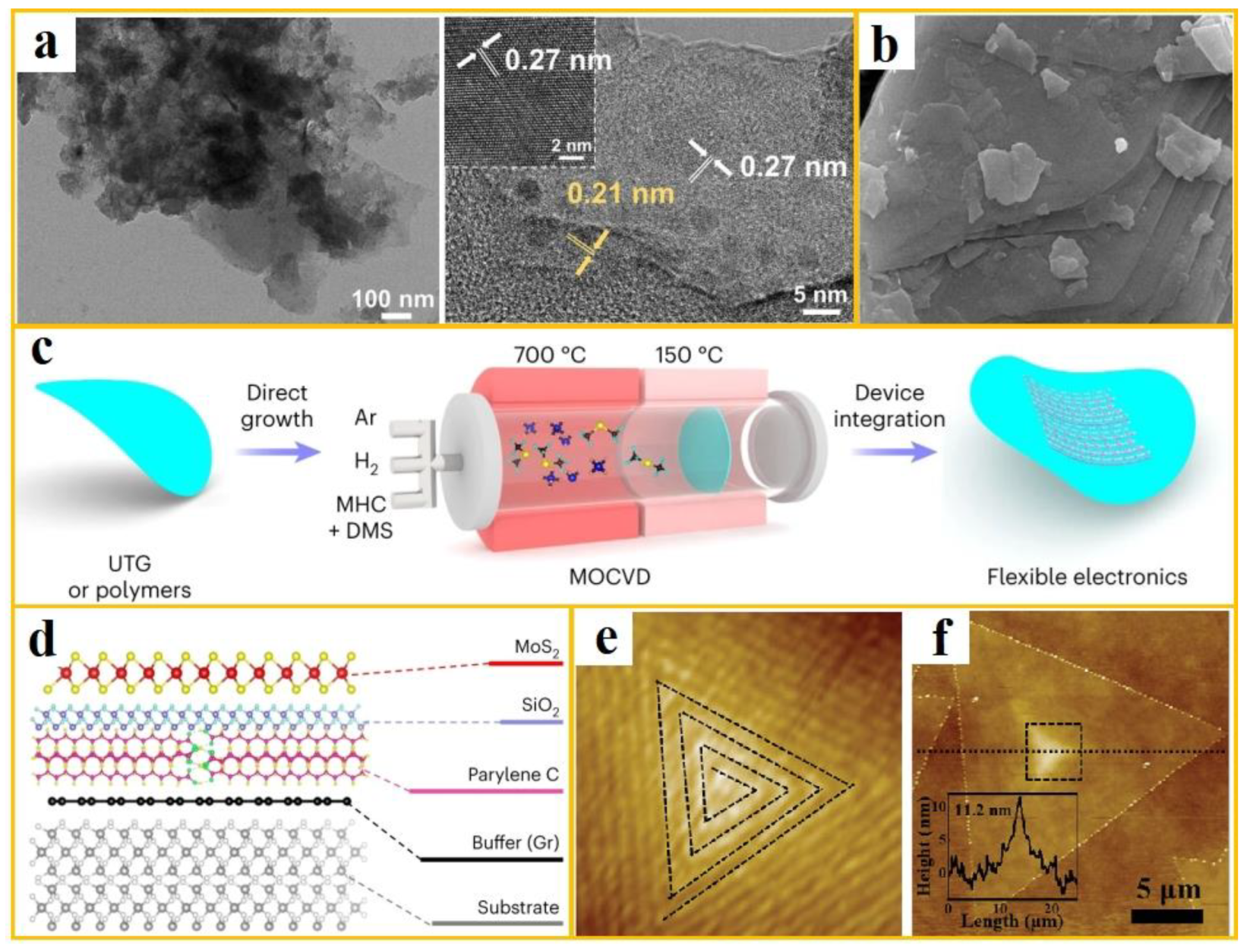

3.1. Mechanical Ball Milling

The mechanical ball milling method involves the use of a ball mill, where raw materials such as molybdenum powder and sulfur powder are added. The milling medium, such as steel balls or ceramic balls, impacts and rubs the powder at high speeds, leading to physical changes and chemical reactions in the raw materials. This process ultimately results in the formation of MoS

2. To further characterize the structural features of the synthesized MoS

2, Raman spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy (AFM) can be utilized to ascertain the number of layers. Hu et al. synthesized near atomic layer 2H-MoS

2 nanosheets (NS) functionalized with graphene quantum dots (GQD) using a mechanical ball milling assisted hydrothermal method. Their morphology is shown in a [

31]. This synthesis process alters the interlamellar distance in MoS

2 and modifies the electronic structure of the near-atomic layer 2H-MoS

2-NS, thereby enhancing its electrocatalytic performance. Additionally, the p-band center analysis reveals that the electron-rich GQD-functionalized 2H-MoS

2-NS exhibits improved adsorption capacity for intermediates, further demonstrating its excellent electrocatalytic activity.

The ball milling method is a widely used technique in the defect engineering of MoS

2. In a pioneering study, Yan et al. employed this method, subjecting MoS

2 to various ball milling times and ball-to-material ratios to investigate their effects on the material. The TEM images are displayed in b. Furthermore, EPR experiments, in conjunction with XPS results, revealed that ball milling induced the formation of additional sulfur defects in MoS

2, thereby exposing more active sites [

32].

Figure 3.

(

a) SEM and TEM images of MoS

2 quantum dots (from ref. [

31], with permission); (

b) TEM images of MoS

2 prepared by ball milling methods (from ref. [

32], with permission); (

c) Schematic diagram of dual temperature zone strategy synthesis and direct manufacturing process (from ref. [

33], with permission); (

d) Optical image (top) and SEM cross-sectional image (bottom) of MoS

2 grown on UTG; (

e-

f) magnified AFM images of spiral pyramid MoS

2 and its central region (from ref. [

34], with permission).

Figure 3.

(

a) SEM and TEM images of MoS

2 quantum dots (from ref. [

31], with permission); (

b) TEM images of MoS

2 prepared by ball milling methods (from ref. [

32], with permission); (

c) Schematic diagram of dual temperature zone strategy synthesis and direct manufacturing process (from ref. [

33], with permission); (

d) Optical image (top) and SEM cross-sectional image (bottom) of MoS

2 grown on UTG; (

e-

f) magnified AFM images of spiral pyramid MoS

2 and its central region (from ref. [

34], with permission).

3.2. Chemical Vapor Deposition

The chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method offers unmatched advantages in synthesizing high-quality, large-area MoS

2 with vertically aligned layer structures [

35]. The synthesis of MoS

2 nanosheets with varying sizes and thicknesses can be precisely controlled by adjusting reaction conditions such as temperature, pressure, gas flow rate, precursor amount, and substrate type [

36].

CVD technology is versatile and can be used to produce MoS

2 films on a wide range of substrates, including hard materials such as silicon wafers and quartz, as well as flexible substrates like PET, PI plastic films, and copper foils. However, hard substrates are inherently brittle, and in applications requiring high mechanical stability, their fragility may prevent them from withstanding complex mechanical environments. Therefore, flexible substrates have become a focal topic in current research [

37]. However, the use of flexible substrates and 2D materials to prepare flexible electronic devices remains challenging. The melting temperature of flexible substrates is often lower than the growth temperature of 2D materials, and the transfer process can lead to surface contamination, material wrinkling, and tearing, which negatively impact their electronic properties [

38].

To address this issue, Jong Hyun Ahn et al. implemented a dual-temperature-zone strategy and synthesis method, as illustrated in c [

33]. The precursor was activated in the high-temperature zone at 700°C, while the flexible substrate remained undamaged in the low-temperature zone at 150°C. They successfully fabricated high-quality, highly crystalline MoS

2 thin films directly on polymer substrates (such as parylene C and polyimide), ultra-thin glass, and other materials using the MOCVD method. The grown MoS

2 structure is shown in d, representing the lowest temperature achieved for CVD synthesis of MoS

2. This method eliminates the need for transfer and enables the direct growth of high-crystallinity MoS

2 on flexible substrates.

Additionally, during the CVD growth of MoS

2, eddy current magnetocaloric technology can be introduced to generate micro eddy currents and magnetic heating effects. This process helps form high-density sulfur vacancies and other active sites, thereby enhancing HER performance. Yuan et al. fabricated three-dimensional spiral pyramid-structured MoS

2 using an improved CVD method, and its AFM image is shown in e-f [

34]. This novel spiral pyramid-structured MoS

2 not only fully exposes the catalytic active sites at the edges but also eliminates interlayer potential barriers, enabling efficient electron transfer along the spiral orbit. Additionally, it is more likely to form eddy currents under alternating electromagnetic fields, further enhancing its catalytic performance. Characterization methods reveal that the spiral MoS

2 structure exhibits layer-by-layer stacking similar to the silicon steel sheet structure in transformers, effectively eliminating the potential barriers found in traditional layered structures. This provides new insights for the design of field-assisted electrocatalytic reactions.

3.3. Wet Chemical Method

MoS

2 and other nanomaterials, including graphene, TiO

2, carbon nanotubes, and noble metals, can be utilized to construct functional nanocomposites through wet chemical methods [

39,

40,

41]. To date, numerous reports have documented functional MoS

2 nanocomposites with various morphologies, including nanorods, nanosheets, nanoflowers, nanoplates, nanowires and hollow nanoparticles [

42,

43,

44]. Li et al. synthesized a lanthanum-doped Ni

3S

2/MoS

2 heterostructure electrocatalyst on foamed nickel [

45]. The preparation scheme depicted in b. They constructed two different transition metal sulfides, Ni

3S

2 and MoS

2, into heterostructures to fully exploit the synergistic effects between the two materials. This approach significantly enhances HER performance of the catalyst. Lanthanum doping modifies the electronic structure and surface chemical properties of the material, increasing the number and activity of active sites, thereby further enhancing the catalyst's performance.

Meanwhile, wet chemical methods have been extensively used to synthesize MoS

2 with various phases. Sun et al. employed electronic control and phosphate stabilization strategies to fabricate stable MoS

2 predominantly in the 1T phase (1T-P-MoS

2) [

46]. The precursors for Mo, S, and PO

43- are (NH

4)

6Mo

7O

24·4H

2O, thiourea, and NaH

2PO

2, respectively. PO

43- was incorporated into MoS

2 using a solvothermal method. The phase transition mechanism of MoS

2 and the electron filling orbitals associated with orbital splitting are depicted in a. The electronic state of Mo 4d is a key factor governing the phase state and electronic properties of MoS

2. When PO

43- is intercalated, a portion of its charges is transferred to Mo. This charge transfer induces the spontaneous transformation of 2H-MoS

2 to 1T-MoS

2 increases the interlayer distance, promoting the formation and stability 1T-MoS

2. After PO

43- intercalation, some electrons are transferred to Mo, leading to the recombination of Mo 4d orbitals. This recombination causes MoS

2 to spontaneously transform from the 2H phase to the 1T phase, which enhances the electronic conductivity of MoS

2.

Figure 4.

(

a) The schematic of the MoS

2 phase transition mechanism and its Mo 4d orbital splitting electron filling in the 2H and 1T phases is presented (from ref. [

46], with permission); (

b) The scheme of La-NMS@NF one-step hydrothermal preparation is also included (from ref. [

45], with permission); The MoS

2-x synthesis pathway and its SEM image are shown in (

c) and (

d), respectively (from ref. [

47], with permission); The 1T-MoS

2/NiS

2 synthesis design diagram and SAED pattern are displayed in (

e) and (

f) (from ref. [

48], with permission).

Figure 4.

(

a) The schematic of the MoS

2 phase transition mechanism and its Mo 4d orbital splitting electron filling in the 2H and 1T phases is presented (from ref. [

46], with permission); (

b) The scheme of La-NMS@NF one-step hydrothermal preparation is also included (from ref. [

45], with permission); The MoS

2-x synthesis pathway and its SEM image are shown in (

c) and (

d), respectively (from ref. [

47], with permission); The 1T-MoS

2/NiS

2 synthesis design diagram and SAED pattern are displayed in (

e) and (

f) (from ref. [

48], with permission).

3.4. Template Method

Unlike the CVD method, which requires high temperatures and gaseous reactants, the template method avoids complex vacuum systems and high-temperature gas delivery, offering a simpler approach to material synthesis [

49]. The template method requires relatively simple equipment. By utilizing the template's structure and properties, it provides spatial constraints and guidance for material growth [

50]. This allows relevant substances to react and deposit at the pores, surfaces, and other sites of the template, resulting in materials with specific morphology, structure, and dimensions. However, the composite materials synthesized using templates are typically limited to a two-dimensional morphology [

51].

Consequently, Yuan et al. pioneered a novel approach by combining sulfur deficient MoS

2 with nitrogen doped carbon, resulting in the fabrication of three-dimensional interconnected sulfur deficient MoS

2/CN composite materials through the salt template method [

47]. The synthesis path is shown in c. They mixed molybdenum source, sulfur source, carbon source, and salt and heated them at 600°C for 5 hours. Following the removal of the salt template, the sample underwent a heat treatment at 800°C for a duration of 6 hours to yield the desired product. In the annealing stage, the presence of hydrogen gas led to the formation of sulfur vacancies, resulting in sulfur-deficient MoS

2. The SEM image, depicted in d, shows the formation of these defects. These defects modify the electronic structure of MoS

2, and thus confer it with enhanced conductivity and ion transport properties.

Furthermore, the template method is considered a viable approach for synthesizing nanomaterials with metastable phases. In a notable study, Yu et al. used layered Ni(OH)

2 as a template, leading to the synthesis of MoS

2 nanosheets with a 1T phase content of 83% [

48]. The synthesis pathway is delineated in e. Experimental characterization demonstrates that Mo

7O

246- ions can be synthesized in situ in a closed space to induce the embedding of 1T-MoS

2. By adjusting the template structure, the ratio between 1T and 2H phases can be readily manipulated. f presents the difference in SAED patterns between 1T-MoS

2/NiS

2 and 2H-MoS

2. The composition and crystal structure of the confinement template play an important role in the formation of the metastable metal phase MoS

2. This specific sample has been shown to unveil more active sites and demonstrate enhanced catalytic activity in alkaline electrolyte solutions.

provides a summary of the synthesis and performance optimization strategies for MoS2 that have emerged in recent years:

Table 1.

Typical MoS2-based nanostructured HER electrocatalysts.

Table 1.

Typical MoS2-based nanostructured HER electrocatalysts.

| Method |

Electrocatalyst |

Main Modulation Strategies |

Electrolyte |

η/mV @ 10 mA cm–2

|

Tafel Slope (mV dec–1) |

Year |

Ref |

| Mechanicaln ball milling |

Atom-layered MoS2 nanosheets |

Increasing edges active sites |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

270 |

83.3 |

2023 |

[52] |

| Few-layer MoS2

|

Increasing edges active sites |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

127 |

199 |

2021 |

[53] |

| CVD |

Ni/MoS2

|

Doping |

1 M KOH |

89 |

59 |

2023 |

[54] |

| PdxSy/1T-MoS2

|

Phase engineering |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

78 |

39.8 |

2023 |

[55] |

| N,Pt-MoS2

|

doping |

1 M KOH |

38 |

39 |

2022 |

[56] |

| LP-MoS2

|

Vacancies engineering |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

35 |

140 |

2024 |

[57] |

| Co2P/1T-MoS2

|

Heterojunction structure |

1 M KOH |

37 |

88 |

2024 |

[58] |

| Re-MoS2-Vs |

Doping |

1 M KOH |

99 |

89 |

2024 |

[59] |

| Ag NPs/1T(2H) MoS2/TNRs |

Phase engineering |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

118 |

38.61 |

2023 |

[60] |

| Wet chemical synthesis |

MoS2/CoS2/NF |

Heterojunction structure |

1 M KOH |

67 |

56 |

2022 |

[61] |

| g–C3N4/FeS2/MoS2

|

Heterojunction structure |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

193 |

87.7 |

2021 |

[62] |

| Co-MoS2-n

|

Doping |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

56 |

32 |

2020 |

[63] |

| 1T MoS2/chlorophyll |

Phase engineering |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

68 |

15.56 |

2023 |

[64] |

| Ni(OH)2 /MoS2 NF |

Heterojunction structure |

1 M KOH |

155 |

62.1 |

2023 |

[65] |

| CoFe/NDC/MoS2

|

Heterojunction structure |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

64 |

45 |

2021 |

[66] |

| MoO2/E/MoS2

|

Heterojunction structure |

1 M KOH |

99 |

109 |

2023 |

[67] |

| Mo-MOFs |

Heterojunction structure |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

98 |

52 |

2022 |

[68] |

| 1T-MoS2/CoS2

|

Phase engineering |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

26 |

43 |

2020 |

[69] |

| MoS2/Ti3C2

|

Heterojunction structure |

1 M KOH |

124 |

24.63 |

2024 |

[70] |

| Pt-MoS2

|

Phase engineering |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

88.43 |

55.69 |

2021 |

[71] |

| Co-MoS2/G |

Doping |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

78.1 |

40 |

2022 |

[72] |

| Template method |

1T-phase nanosheets MoS2

|

Phase engineering |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

199 |

54 |

2024 |

[73] |

| MoS2 QDs |

Increasing edges active sites |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

190 |

74 |

2014 |

[74] |

| Pseudo-1T MoS2

|

Phase engineering and doping |

0.5 M H2SO4

|

165 |

44 |

2022 |

[75] |

4. Fabrication of MoS2-Based HER Electrocatalysts

MoS

2 was first documented as a catalyst for HER in 1977 [

17]. In 2005, some scholars reported that theoretical calculations indicated MoS

2 had HER catalytic activity similar to that of Pt under acidic conditions. However, the measured activity was much lower than the theoretical predictions [

18]. The primary reason for this discrepancy is the chemical inertness of the (001) crystal plane of MoS

2 to HER, which restricts the active sites to a limited edge. This conclusion was subsequently published in 2007 [

76]. Consequently, enhancing the catalytic activity of MoS

2 has become a prominent research focus. Activating the active sites on the MoS

2 substrate and enhancing the intrinsic activity of individual active sites are of great scientific significance and present substantial challenges.

4.1. Morphological Modulation

The morphology of catalysts is a critical factor in developing materials with superior performance. As previously discussed, MoS

2 manifests catalytic activity exclusively at its edge sites. To enhance the performance of MoS

2, designing nanostructures with specific morphologies is essential. These morphologies can activate the basal active sites and regulate the HER properties of MoS

2 [

77,

78].

In 2011, a seminal study by Mark C. Hersam et al. facilitated the isolation of atomically thin MoS

2 layers, filling a significant gap in the field of graphene and establishing two-dimensional MoS

2 as a promising material [

79]. This breakthrough catalyzed extensive research into the creation of layered MoS

2 nanostructures, with numerous scholars exploring methods to synthesize MoS

2 with diverse morphologies and applications.

4.1.1. Conventional Morphology Design

In 2005, theoretical calculations brought sheet-like MoS

2 into the spotlight due to its advantageous properties, such as a larger specific surface area and more exposed edge active sites compared to bulk materials. With the gradual maturation of techniques such as mechanical exfoliation and CVD, the preparation of nanosheet MoS

2 became feasible. This development subsequently promoted research on other structures in HER [

80].

The synthesis of MoS

2 nanosheets has evolved from multilayer to monolayer, from nanosheets (NSs) to quantum sheets (QSs), and from uncontrollable to controllable size. Recently, Zhang et al. achieved a significant breakthrough in the synthesis of MoS

2 nanosheets [

42]. They reported the preparation of 2H-MoS

2 NSs with full-size controllability using a combination of SiO

2 ball milling and ultrasound-assisted solvent exfoliation techniques. By meticulously adjusting the duration of the ball milling process, the researchers were able to produce multi-scale NSs with distinct distribution patterns. This study systematically investigated the impact of MoS

2 sample size on HER. The overpotentials of MoS

2 QSs and MoS

2 NSs at 10 mA cm

-2 were 264 and 211 mV.

The synthesis of MoS

2 nanowires typically involves the use of CVD or template methods. The focus of research on MoS

2 nanowires has been primarily centered on the period from 2015 to 2017. In this context, Hitanshu Kumar and his team's research, published in 2017, is particularly noteworthy [

81]. They explored the use of argon plasma treatment to modify the structure of MoS

2, with the aim of enhancing HER performance. The HRTEM images of the nanowires are shown in a-b. By systematically adjusting the plasma treatment parameters, researchers can precisely control the degree of structural change in the MoS

2 material. This regulation results in an augmentation of the specific surface area, the generation of defects, and a change in the chemical bond state, significantly improving the electrocatalytic performance. The overpotential at 10 mA cm

-2 is 190 mV.

MoS

2 nanospheres typically manifest as spherical or quasi-spherical in morphology, with their diameter capable of modulation across a range from a few nanometers to hundreds of nanometers, contingent upon the specific conditions of their preparation. The synthesis of MoS

2 nanospheres typically involves the employment of either the microemulsion method or the sol-gel method. In a notable study, Zhou et al. optimized the hydrogen adsorption desorption behavior of sulfur sites by strategically introducing carbon elements into the lattice gaps of MoS

2 nanospheres [

82]. The nanosphere structure is illustrated in c, thereby enhancing the HER performance of the material, with an overpotential of 87 mV at 10 mA cm

-2.

MoS

2 nanotubes possess a distinctive hollow structure, with their tube walls composed of curled nanosheets. The preparation methods for MoS

2 nanotubes include the hydrothermal method, CVD method, the template method, the mechanical ball milling method, and the atomic layer deposition (ALD) method. Xu et al. employed ALD technology to deposit Pt atoms uniformly on the wall of MoS

2 nanotubes, as illustrated in d. Their electrochemical data demonstrate that MoS

2 nanotubes are more suitable as carriers of Pt atoms for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution than two-dimensional MoS

2 nanostructures [

83]. The overpotential of Pt-loaded tubular MoS

2 was determined to be 32 mV at 10 mA cm

-2, with a Tafel slope of 35 mV dec

-1.

Figure 5.

(

a-

b) HRTEM images of atomic arrangement and d-spacing of MoS

2 nanowires (from ref. [

81], with permission); (

c) HRTEM image of MoS

2 nanorods (from ref. [

82], with permission); (

d) Magnified HRTEM image of Pt/MoS

2-NTA with inset showing the HAADF intensity distribution map taken along the labeled rectangle (from ref. [

83], with permission); (

e) Atomic structure diagram of mixed MoS

2/WS

2 heterostructures grown under insufficient NH

4Cl supply (from ref. , [

84]with permission); (

f) HAADF-STEM image of Ru MIs-MoS

2, with Ru single atom islands uniformly dispersed in a 2D MoS

2 plane (from ref. [

85], with permission); (

g-

h) HRTEM, AFM image of MoS

2 nanosheets modified with CL-MoS

2 quantum dots (from ref. [

86], with permission); (

i) AC-TEM image of C-Co-MoS

2 in the swollen layer (from ref. [

87], with permission).

Figure 5.

(

a-

b) HRTEM images of atomic arrangement and d-spacing of MoS

2 nanowires (from ref. [

81], with permission); (

c) HRTEM image of MoS

2 nanorods (from ref. [

82], with permission); (

d) Magnified HRTEM image of Pt/MoS

2-NTA with inset showing the HAADF intensity distribution map taken along the labeled rectangle (from ref. [

83], with permission); (

e) Atomic structure diagram of mixed MoS

2/WS

2 heterostructures grown under insufficient NH

4Cl supply (from ref. , [

84]with permission); (

f) HAADF-STEM image of Ru MIs-MoS

2, with Ru single atom islands uniformly dispersed in a 2D MoS

2 plane (from ref. [

85], with permission); (

g-

h) HRTEM, AFM image of MoS

2 nanosheets modified with CL-MoS

2 quantum dots (from ref. [

86], with permission); (

i) AC-TEM image of C-Co-MoS

2 in the swollen layer (from ref. [

87], with permission).

4.1.2. Unconventional Morphology Design

The increasing demand for high-performance materials has highlighted the limitations of conventionally structured MoS2. To further expand its application scope and enhance its performance, researchers have begun exploring unconventional structural designs. These novel designs aim to overcome the limitations of traditional structures in electronic transport, chemical activity, and other aspects. Potential designs include vertically arranged layers, different stacked structures, quantum dots, and other innovative structures.

The study of the vertical arrangement layer structure of MoS

2 commenced in 2013, when Kong et al. initially reported a method for synthesizing MoS

2 and MoSe

2 thin films with vertical arrangement layers [

88]. A prominent feature of this structure is its perpendicular growth relative to the substrate. The synthesis of these layers involves two primary methods: CVD method and the template-assisted growth method. Duan et al. induced the formation of active clusters featuring ultra-low adsorption energy by introducing NH

4Cl [

84]. This process promoted the nucleation and growth of WS₂ on MoS

2, thereby forming a vertical heterostructure. The atomic-scale structural diagram is presented in e.

The primary factor contributing to the suboptimal hydrogen evolution performance of conventional three-dimensional layered MoS

2 is the restricted quantity of active sites and the reduced electron transfer efficiency. To address this challenge, numerous scholars have investigated the preparation of diverse stacked structures of MoS

2 to enhance its hydrogen evolution performance. For example, Yuan et al. successfully prepared three-dimensional spiral pyramid MoS

2 with abundant edge active sites on SiO

2/Si substrates using a tilted substrate CVD method [

89]. The morphology of the spiral pyramid MoS

2 is illustrated in e-f, offering novel insights into the impact of eddy current on the electrocatalysis of transition metal disulfides.

In recent years, the synthesis and research of MoS

2 nanoislands have become a prominent area garnering widespread interest among scientists. Various preparation methods, such as CVD and hydrothermal techniques, have been employed to study this phenomenon. These methods inherently introduce defects during the synthesis process, which can manipulate the local electronic structure and chemical properties, generating additional active sites for hydrogen atom adsorption and reaction. Cao et al. employed HiGee technology to synthesize Ru monolayer islands (MIs)-doped MoS

2 samples [

85]. In these samples, Ru MIS was uniformly anchored onto the surface of MoS

2 via coordination with S species. Moreover, Ru atoms were uniformly doped into the MoS

2 lattice in a single - layer island - like configuration. The corresponding HAADF - STEM image is presented in f. This catalyst demonstrated the highest utilization rate of Ru atoms, enabling the maximum and stable exposure of MoS

2 edge sites.

Upon transitioning from a bulk material to quantum dots (with a size less than 10 nm), MoS

2 experiences a pronounced quantum confinement effect, resulting in significant alterations to its electronic and band structures. The preparation methods encompass liquid-phase exfoliation, hydrothermal method, CVD method, and plasma laser synergistic effect method. Chandra Sekhar et al. expedited the synthesis of zero dimensional (0D) MoS

2 quantum dots through a freeze-mediated liquid-phase exfoliation process, and their HRTEM and AFM images are shown in g-h. Moreover, they employed a self-assembly strategy to form quantum dot-modified 0D/2D homojunctions between the exfoliated quantum dots and nanosheets [

86].

Further research on MoS

2 reveals that its catalytic performance lags behind that of commercial Pt/C, even with the smallest size and structure of 2nm MoS

2. Consequently, the manipulation of morphology can be integrated with heterostructures, such as heteroatom doping methodologies, which facilitate the anchoring of carbon-based SACs in horizontal, axial, and asymmetric coordination structures. These structures exhibit enhanced advantages over single anchored catalysts. Gong et al. developed dual anchored C-M-MoS

2 SACs (M=Co, Ni, Fe, Zn, W, Cu, Mn, and Cd) employing a universal sub nano strategy [

87]. The AC-TEM image of the C-Co-MoS

2 expansion layer is presented in i, which is used to promote hydrogen electrocatalysis. The experimental findings demonstrate that the sub nano strategy can be utilized to prepare a series of MoS

2-supported single-atom electrocatalysts, featuring dual anchored local microenvironments on egg yolk shell C-MoS

2. A comparison of the optimized C-Co-MoS

2 with previously reported MoS

2-based electrocatalysts reveals that the former exhibits a lower overpotential (17 mV at 10 mA cm

-2) and a substantially enhanced activity, ranging from five to nine times higher.

4.2. Phase Engineering

The phase engineering strategy is a process that involves converting the semiconductor 2H phase of MoS

2 into the metallic 1T or 1T′ phase. Specifically, this process increases density of catalytic sites, improving the velocity of electron transfer, enhancing conductivity, and boosting electrocatalytic activity [

27]. The phase engineering strategy of MoS

2 encompasses two distinct approaches: synthesis strategy and phase transition strategy [

90]. These strategies modify the electronic configuration and atomic coordination milieu of the MoS

2 substrate, revealing significantly more active sites and optimizing the distribution of catalytic sites.

The most common synthesis pathway for 1T/1T′-MoS

2 is the wet chemistry method, which can generally yield MoS

2 with specific morphology by modifying the reaction conditions. In a notable study, Dae Joon et al. incorporated sodium phosphate into an aqueous solution of sodium molybdate and thiourea, thereby producing defect-type hierarchical phosphorus-doped biphasic MoS

2 nanosheets [

91]. The synthesis process and morphology are illustrated in a-b, where the doped P atoms modify the electronic structure of MoS

2, enhance the reaction kinetics during water electrolysis, and substantially improve its conductivity and structural stability. The catalytic performance of the catalyst is demonstrated in c, exhibiting hydrogen evolution overpotentials of 60 mV and 72 mV (10 mA cm

−2) in acidic and alkaline electrolytes, respectively.

Synthesizing 1T-MoS

2 with controllable proportions through wet chemical synthesis is a difficult problem in phase engineering strategy. In addressing this challenge, Yu et al. employed a spatial confinement template strategy, synthesizing 1T-MoS

2 with a maximum content of 83% through hydrothermal sulfurization using Mo

7O

246− intercalated Ni(OH)

2 as the precursor [

92]. d presents the HAADF-STEM images of edge enrichment. The experimental characterization demonstrates that the ratio of sulfur source to precursor is a determining factor in the content of 1T-MoS

2. The composition and crystal structure of the confinement template significantly contribute to the formation of the metastable metal phase MoS

2. Utilizing a NiS

2 confined template facilitates the acquisition of 1T-MoS

2/NiS

2 catalytic performance, as illustrated in e. The overpotential at 10 mA cm

-2 in an alkaline electrolyte is 116 mV, which is among the most efficient synthesis methods employing wet chemistry methods.

Figure 6.

(

a-b) A flowchart and TEM image of the P-BMS electrocatalyst synthesized using the hydrothermal method; (

c) LSV curves of P-BMS catalysts at acidic (from ref. [

91], with permission); (

d) Atomic resolution HAADF-STEM images of edge-enriched 1T-MoS

2 QS; (

e) LSV curves in 1 M KOH (from ref. [

92], with permission); (

f-

g) HAADF-STEM images of s-Pt/1T′-MoS

2 and 1T′-MoS

2; (

h) Schematic diagram of the floating electrode setup (from ref. [

93], with permission).

Figure 6.

(

a-b) A flowchart and TEM image of the P-BMS electrocatalyst synthesized using the hydrothermal method; (

c) LSV curves of P-BMS catalysts at acidic (from ref. [

91], with permission); (

d) Atomic resolution HAADF-STEM images of edge-enriched 1T-MoS

2 QS; (

e) LSV curves in 1 M KOH (from ref. [

92], with permission); (

f-

g) HAADF-STEM images of s-Pt/1T′-MoS

2 and 1T′-MoS

2; (

h) Schematic diagram of the floating electrode setup (from ref. [

93], with permission).

It has been established that MoS

2 synthesized through wet chemical methods is biphasic, with the metastable 1T/1T′ phase exhibiting a high generation energy. Consequently, the synthesis of bulk/nano pure 1T′-TMDs is rendered extremely challenging under mild reaction conditions. In order to synthesize 1T′-MoS

2 with high phase purity, Zhang et al. synthesized 1T′-MoS

2 through solid-state reaction, and on this basis, metal Pt was loaded on 1T′-MoS

2 and 2H-MoS

2 using photoreduction method [

93]. Specifically, f-g shows the HAADF-STEM morphology, and it can be observed that the aggregation of Pt is related to the crystal phase of MoS

2. The 2H phase template promotes the formation of Pt nanoparticles loaded on MoS

2, while the 1T phase can load single atom dispersed Pt atoms. The s-Pt/1T′-MoS

2 obtained by setting the floating electrode according to h exhibits enhanced electrocatalytic activity. The hydrogen evolution overpotential in the alkaline electrolyte at 10 mA cm

-2 is -19 ± 5 mV.

Single layer 1T′-MoS

2 has been shown to feature a higher density of active sites and thus exhibit enhanced HER performance. However, in order to achieve a synthesis that surmounts the interlayer van der Waals attractions, a greater level of complexity is required, thus significantly increasing the difficulty of the process. Recently, Huang et al. proposed a novel method for the direct preparation of monolayer 1T'-MoS

2 by colloidal chemical thermal injection method, and its crystal structure and morphology are shown in a-b. The effects of different alkyl amine/alkyl acid ligands, precursor initial supersaturation, and other experimental conditions on the phase purity, number of layers, nucleation mechanism, and growth process of 1T'-MoS

2 were revealed [

94]. The prepared 1T'-MoS

2 exhibits excellent electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution activity, with a polarization curve shown in c and an overpotential of 149 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm

-2.

Besides the direct synthesis techniques, phase transition constitutes another approach for the preparation of 1T/1T'-MoS

2. Theoretical calculations demonstrate that phase transition is advantageous in enhancing electrochemical reaction kinetics, optimizing hydrogen adsorption behavior, and consequently augmenting the HER activity of MoS

2. The incorporation of charge carriers has been demonstrated to reduce the energy difference between the 1H and 1T phases of MoS

2, while the introduction of sulfur vacancies and lattice strain has been shown to stabilize the 1T phase. Li et al. synthesized Se-MoS

2 with Se and O co-embedded by hydrothermal method. The synthesis strategy is illustrated in e. The incorporation of Se modifies the environment of Mo atoms, leading to the generation of a substantial number of S defects on the surface area of MoS

2 and the subsequent insertion of O, resulting in the transformation of MoS

2 from the 2H phase to the 1T phase (~60% 1T phase) [

95]. The performance of the material is demonstrated in h, and it is evident that at a current density of 10 mA cm

-2 in 0.5 M H

2SO

4 electrolyte, the overpotential of Se-MoS

2 is 108 mV.

Moreover, plasma treatment has been demonstrated to induce local strain on the surface of MoS

2, thereby facilitating a phase transition from the 2H phase to the 1T phase. Anup Kumar Keshri et al. investigated the correlation between process parameters and the efficacy of stripping and phase transformation through plasma spray stripping. The lattice structure, XRD and SEM images of the synthesized ultra-thin 1T-MoS

2 are shown in f [

96], and 100% 1T-MoS

2 with a thickness of 1.0-2.6 nm was synthesized, paving the way for the large-scale production of high-quality ultra-thin 1T-MoS

2. For the phase transition from 2H phase to 1T′-MoS

2, Zhang et al. proposed a simple and controllable salt-assisted synthesis strategy [

97]. The phase transition strategy is illustrated in d, which involves the transformation of a substantial quantity of commercially available 2H MoS

2 into a metastable 1T′ phase, facilitated by K

2C

2O

4·H

2O. The transformation of the crystal morphology is illustrated in g, leading to a significant simplification of the synthesis process for metastable 1T′ phase TMDs.

Figure 7.

(

a) Crystal structure of 1T′-MoS

2; (

b) HRTEM image of 1T′-MoS

2 nano-monolayer illustrating the jagged chains of molybdenum atoms (purple balls); (

c) Polarization curve of 1T′-MoS

2 (from ref. [

94], with permission); (

d) Schematic illustration of the general strategy of phase transition in TMD materials (from ref. [

97], with permission); (

e) Schematic representation of the synthesis of Se-MoS

2 (from ref. [

95], with permission); (

f) Schematic representation of ultrathin 1T-MoS

2 prepared by plasma spraying technique, with the lattice structure, XRD and SEM images of 2H-phase and 1T-phase MoS

2 on the left and right, respectively (from ref. [

96], with permission); (

g) Transformation of 2H-phase; (

h) HER polarization curve of Se-MoS

2.

Figure 7.

(

a) Crystal structure of 1T′-MoS

2; (

b) HRTEM image of 1T′-MoS

2 nano-monolayer illustrating the jagged chains of molybdenum atoms (purple balls); (

c) Polarization curve of 1T′-MoS

2 (from ref. [

94], with permission); (

d) Schematic illustration of the general strategy of phase transition in TMD materials (from ref. [

97], with permission); (

e) Schematic representation of the synthesis of Se-MoS

2 (from ref. [

95], with permission); (

f) Schematic representation of ultrathin 1T-MoS

2 prepared by plasma spraying technique, with the lattice structure, XRD and SEM images of 2H-phase and 1T-phase MoS

2 on the left and right, respectively (from ref. [

96], with permission); (

g) Transformation of 2H-phase; (

h) HER polarization curve of Se-MoS

2.

4.3. Defect Engineering

Defect engineering is the process of artificially introducing various defects into MoS2 to alter its microstructure and electronic structure, thus allowing control over its hydrogen evolution performance. During the preparation and synthesis process, vacancy defects and edge defects are often introduced to control and optimize the catalytic properties of MoS2. The presence of vacancy defects has been shown to modify the charge distribution on the surface of MoS2, thereby regulating the material's adsorption free energy for hydrogen atoms. Atoms at the edge defects exhibit higher activity and can form more stable transition states with reactants, thereby reducing the energy barriers at each step of the HER process.

The introduction of vacancy defects, whereby some sulfur atoms are absent from MoS

2, results in the formation of a surface "defect" structure, thereby exposing the molybdenum atoms within the inner layer. These exposed molybdenum atoms are in a bonding unsaturated state, which facilitates the adsorption of reactants and subsequent catalysis of chemical reactions [

98]. Zhou et al. synthesized MoS

2 with different local atomic environments of vacancies using the limited growth method. The generation of unsaturated chemical bonds in the absence of sulfur atoms has been shown to enhance the adsorption of hydrogen atoms, suggesting that the increased exposure of molybdenum atoms in the vicinity of vacancies contributes to the promotion of HER intrinsic activity in MoS

2.

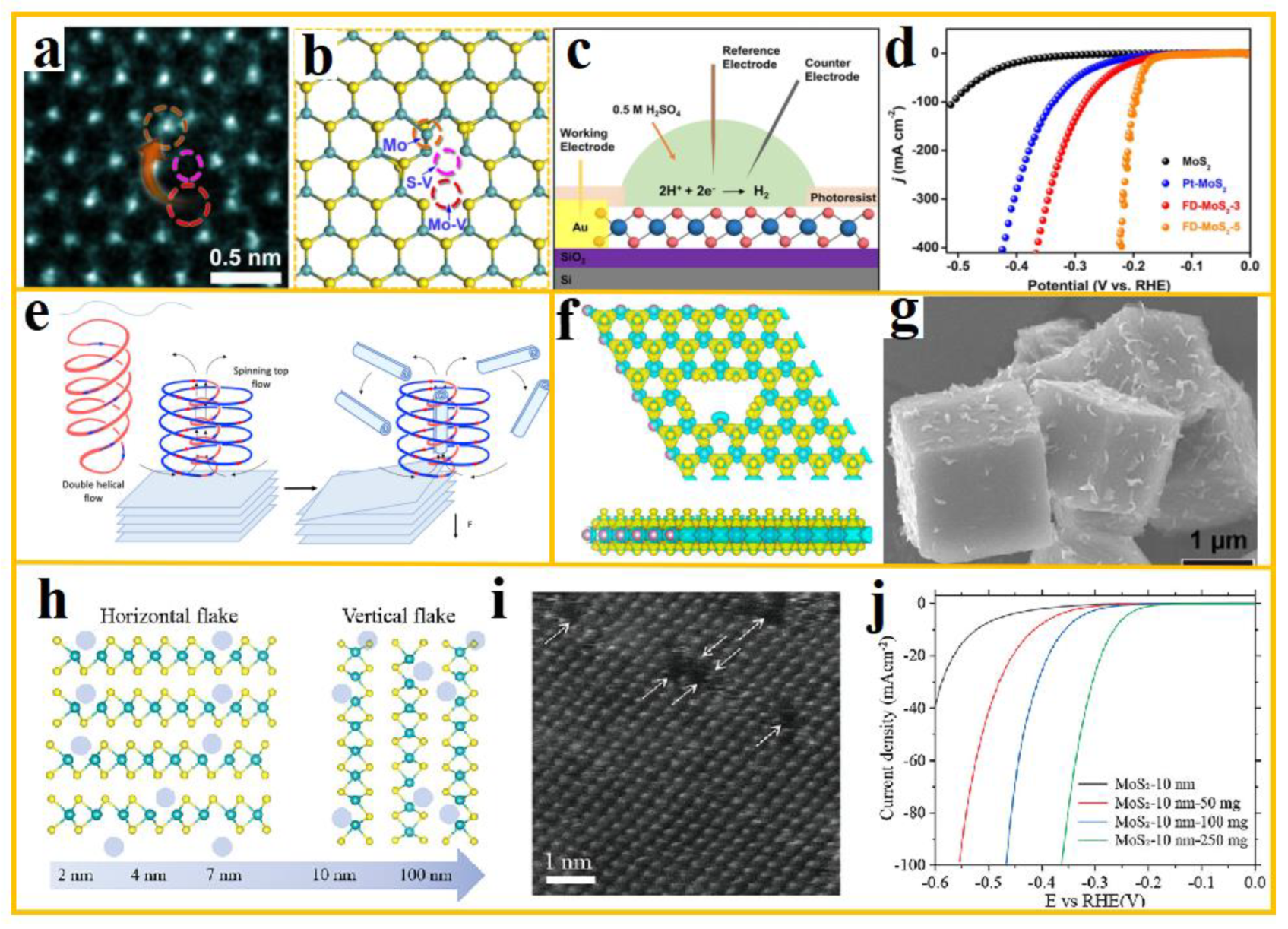

A study was recently conducted by Xu et al., in which a single-layer MoS

2 catalyst containing Frenkel defects was prepared, and the atomic configuration of these defects was revealed for the first time through AC-STEM observation [

99]. The HAADF-STEM image is shown in a-b. DFT calculations indicate that a portion of Mo atoms in MoS

2 spontaneously deviate from their original positions in the lattice and remain in proximity to the lattice, thereby creating vacancies and becoming interstitial atoms. The introduction of these point-like defects has been shown to result in a prominent charge distribution effect in MoS

2, as illustrated in c. This charge distribution effect has been found to render the interstitial Mo atoms more conducive to H adsorption, thereby significantly promoting HER activity. The polarization curve is shown in d. In a 0.5 M H

2SO

4 electrolyte, the overpotential of the catalyst is 164 mV at a current density of 100 mA cm

-2, and it exhibits lower energy loss.

Figure 8.

(

a-

b) FD-MoS

2 atomic resolution HAADF-STEM images and corresponding atomic models; (

c) Schematic of the microreactor; (

d) HER polarization curves (from ref. [

99], with permission); (

e) Schematic representation of the MoS

2 vortex formation mechanism: the ST topological fluid flow is centrifugally exfoliated on the surface of immobilized MoS

2 particles on the tube surface and subsequently rolls into a chiral upward flow in the ST core (from ref. [

100], with permission); (

f) Top and side view electron density difference maps of c-MoS

2; (

g) SEM image of c-MoS

2 (from ref. [

101], with permission); (

h) Schematic representation of vacancy formation in vertically and horizontally grown MoS

2 samples; (

i) Atomic resolution STEM images of defect formation; (

j) Normalized polarization curves measured for MoS

2 grown from 10 nm Mo crystal seed layers after different PH

3 annealing treatments (from ref. [

102], with permission).

Figure 8.

(

a-

b) FD-MoS

2 atomic resolution HAADF-STEM images and corresponding atomic models; (

c) Schematic of the microreactor; (

d) HER polarization curves (from ref. [

99], with permission); (

e) Schematic representation of the MoS

2 vortex formation mechanism: the ST topological fluid flow is centrifugally exfoliated on the surface of immobilized MoS

2 particles on the tube surface and subsequently rolls into a chiral upward flow in the ST core (from ref. [

100], with permission); (

f) Top and side view electron density difference maps of c-MoS

2; (

g) SEM image of c-MoS

2 (from ref. [

101], with permission); (

h) Schematic representation of vacancy formation in vertically and horizontally grown MoS

2 samples; (

i) Atomic resolution STEM images of defect formation; (

j) Normalized polarization curves measured for MoS

2 grown from 10 nm Mo crystal seed layers after different PH

3 annealing treatments (from ref. [

102], with permission).

Theoretical calculations demonstrate that the edge sites of MoS

2 exhibit exceptional catalytic activity, with a hydrogen adsorption ΔG

H of only 0.06 eV, which is on a par with that of the precious metal platinum [

76]. Edge atoms in MoS

2 exhibit elevated chemical activity, and compared with internal atoms, their coordination is unsaturated, with dangling bonds that can provide a greater number of active sites. Consequently, researchers are committed to the preparation of nanoscale MoS

2 with highly exposed edge defect sites [

103]. Xu et al. pioneered the development of ultra-thin MoS

2 with abundant defect sites through a continuous micro reaction method, which exhibited high heat and mass transfer rates. e shows the synthesis schematic [

100]. It is hypothesized that the enhanced uniformity and rate of mass transfer will result in a reduction in reaction time, resulting in the formation of smaller and thinner MoS

2 and a larger quantity of edge active sites. The presence of substrate plane defects has also been demonstrated to expose a larger quantity of active sites, delivering excellent HER performance with an overpotential of 260 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm

−2.

In the contemporary era, advanced characterization techniques have been developed which are capable of observing the formation of active sites during the process of electrochemical activation. Ren et al. utilized electrochemical tip enhanced Raman spectroscopy (EC-TERS) technology to achieve in situ monitoring of the geometric and electronic evolution of catalytic active sites in HER at nanoscale spatial resolution for the first time. Their observations revealed a 40 nm reconstruction region characterized by distinct lattice and electron densities, extending from the edge position to the nearby basal plane. f shows the difference in electron density between the top and side views of c-MoS

2, and g shows its SEM image. The synergistic reconstruction around the active edge, due to lattice deformation, has been shown to reduce the activation energy barrier, with atoms around the coordinated unsaturated edge tending to self-adjust, resulting in a lattice structure with the lowest energy. The observed change in the geometric structure of the active site is attributed to the high electrocatalytic activity [

101].

Recently, Zhou et al. investigated the preparation of MoS

2 catalysts with controllable defect concentrations [

102]. To this end, a range of MoS

2 catalysts with controllable defect concentrations were synthesized through thermochemical annealing under phosphine gas. The crystal structure of defect formation and retention in MoS

2 catalysts was systematically studied using XPS, XANES, and EPR. h provides a schematic representation of vacancy formation in both vertically and horizontally grown MoS

2 samples, while i presents their corresponding STEM images. Following thermochemical annealing with PH

3, the HER activity of both vertically and horizontally arranged MoS

2 thin films was enhanced. j presents the normalized polarization curves of MoS

2 grown from 10nm Mo seed layers following annealing at varying PH

3 levels. These active defects have been shown to regulate the thermodynamic adsorption/desorption of protons, as well as adjust the interface energy level to facilitate electron transfer and enhance the HER activity of the catalyst.

4.4. Construction of Heterostructures

In comparison with the catalytic performance of a single component, heterostructure strategies have been shown to optimize the interfacial properties of materials, integrate the advantages of different materials, and increase the efficiency of catalytic reactions. The interaction between different materials can produce synergistic effects, further enhancing the performance of the materials. Moreover, the construction of heterostructures involves the formation of heterostructures between metals and their compounds, non-metals and their compounds, and MoS

2 [

104]. These heterostructures have the capacity to optimize ΔG

H and enhance HER performance. The design of heterostructures, including core-shell structures and sandwich structures, can be tailored to different materials, thereby enhancing the performance and application value of MoS

2 heterostructure catalysts.

4.4.1. MoS2-Metal Nanocomposite Heterostructures

Metals and metal compounds can form heterostructures with MoS

2 through interfacial chemical bonding, charge transfer, lattice matching, and stress effects [

105]. The interfaces of these heterostructures exhibit a high concentration of unsaturated chemical bonds and defects, which exhibit enhanced chemical reactivity. is capable of forming heterostructures with metals, typically precious metals, leading to the generation of van der Waals forces. This induces strain in the MoS

2 lattice and results in local electron redistribution, significantly enhancing HER performance [

106].

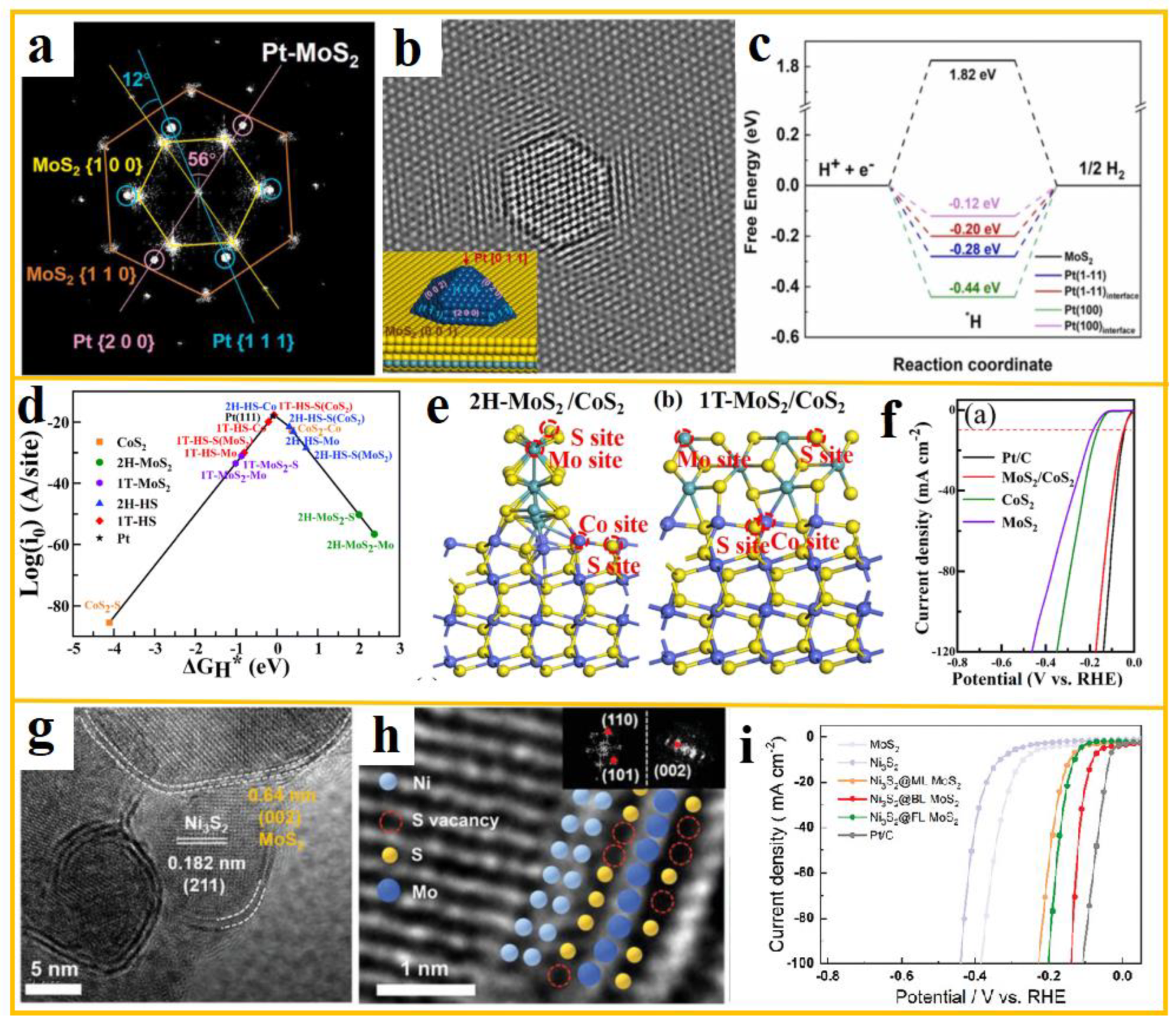

Wang et al. prepared Pt-MoS

2 composite nanocatalysts using wet chemical methods and studied in detail their surface atomic arrangement, interface atomic configuration, and electronic states, revealing the effect of interface interactions in determining catalytic activity and stability [

107]. Aberration corrected environmental electron microscopy revealed the presence of monodisperse single crystal Pt nanoparticles (~3 nm) surrounded by {111} and {200} crystal plane clusters on the surface of MoS

2 nanosheets. a-b illustrate HRTEM images, FFT images, and simulated TEM images of possible atomic models constructed by QSTEM program for Pt-MoS

2, respectively. It is this interface electronic structure regulation that results in the Pt-MoS

2 heterostructure exhibiting excellent HER activity and stability. The LSV curve is 67.4 mV when the current density reaches 10 mA cm

-2 in alkaline solution. According to the DFT calculation in c, the formation of Pt-S bonds on the surface prevents the aggregation of Pt nanoparticles, thereby improving the catalyst’s catalytic performance and long-term stability.

Figure 9.

(

a-

b) FFT images, and simulated TEM images of possible atomic models constructed by QSTEM program for Pt-MoS

2 ; (

c) Gibbs free energy of hydrogen adsorption at Pt position and MoS

2 surface(from ref. [

107], with permission); (

d) Log(i

0) and ΔG

H* volcano plot of each adsorption site; (

e) Ball and stick models of 2H and 1T-MoS

2/CoS

2 heterostructures, with red dashed circles representing H* adsorption sites at Mo, Co, and S atoms on the heterostructure, respectively; (

f) LSV curve of MoS

2/CoS

2(from ref. [

108], with permission); (

g-

h) TEM and HRTEM images of epitaxial growth of layered MoS

2 on Ni

3S

2 ; (

i) The LSV curve of Ni

3S

2@MoS

2(from ref. [

109], with permission).

Figure 9.

(

a-

b) FFT images, and simulated TEM images of possible atomic models constructed by QSTEM program for Pt-MoS

2 ; (

c) Gibbs free energy of hydrogen adsorption at Pt position and MoS

2 surface(from ref. [

107], with permission); (

d) Log(i

0) and ΔG

H* volcano plot of each adsorption site; (

e) Ball and stick models of 2H and 1T-MoS

2/CoS

2 heterostructures, with red dashed circles representing H* adsorption sites at Mo, Co, and S atoms on the heterostructure, respectively; (

f) LSV curve of MoS

2/CoS

2(from ref. [

108], with permission); (

g-

h) TEM and HRTEM images of epitaxial growth of layered MoS

2 on Ni

3S

2 ; (

i) The LSV curve of Ni

3S

2@MoS

2(from ref. [

109], with permission).

In the construction of heterostructures between MoS

2 and metal compounds, Tao et al. explored the HER properties of the material over a wide pH range, synthesizing MoS

2/CoS

2 heterostructures in the process [

108]. Through a combination of theoretical calculations and experiments, data such as Gibbs free energy and theoretical exchange current density were calculated under different conditions, as illustrated in d. This study employs a multifaceted approach, integrating theoretical calculations with experimental observations to provide a nuanced understanding of the material's behavior. The LSV curve of the material under alkaline conditions is shown in f, with an overpotential of 46 mV. The enhancement in performance can be attributed primarily to the enhanced electronic localization and local bonding of Co atoms at the co-activated interface. e presents the ball and stick models of 2H and 1T-MoS

2/CoS

2 heterostructures, where interface effects enhance electronic conductivity and improve hydrogen adsorption properties, rendering MoS

2/CoS

2 highly valuable as an efficient HER electrocatalyst.

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that certain materials are capable of forming special structures, including core-shell structures, during the process of heterostructure construction with MoS

2. The encapsulation or support of these materials can improve the total stability of the heterostructure, while the shell material can protect the core material from external environmental influences, prevent aggregation, oxidation, or corrosion, thereby improving the stability of the material under various conditions and extending its service life [

110]. Li et al. synthesized a biaxial strain nanoshell in the form of a single-crystal Ni

3S

2/MoS

2 core-shell heterostructure using a new in-situ self sulfurization strategy [

109]. g-h shows TEM and HRTEM images of the epitaxial growth of layered MoS

2 on Ni

3S

2, with the MoS

2 layer precisely manipulated within the range of 1 to 5 layers. Specifically, electrodes with double-layer MoS

2 nanoshells exhibit significant hydrogen evolution activity, as evidenced by the LSV curves shown in i, which demonstrate a low overpotential of 78.1 mV at 10 mA cm

–2. Density functional theory calculations highlight the role of optimized biaxial strain and induced sulfur vacancies, identifying the origin of the enhanced catalytic sites in these biaxially strained MoS

2 nanoshells.

4.4.2. MoS2-Non-Metal Compound Heterostructures

The incorporation of non-metallic elements has been shown to shift the Fermi level of MoS

2, thereby moderating the adsorption of hydrogen atoms on the material surface and reducing the activation energy of HER [

111,

112]. For example, in the heterostructure of molybdenum disulfide and graphene, the two-dimensional planar structure of graphene can support and separate MoS

2 nanosheets, increase the exposure of edge sites, and provide more active sites for HER [

113,

114].

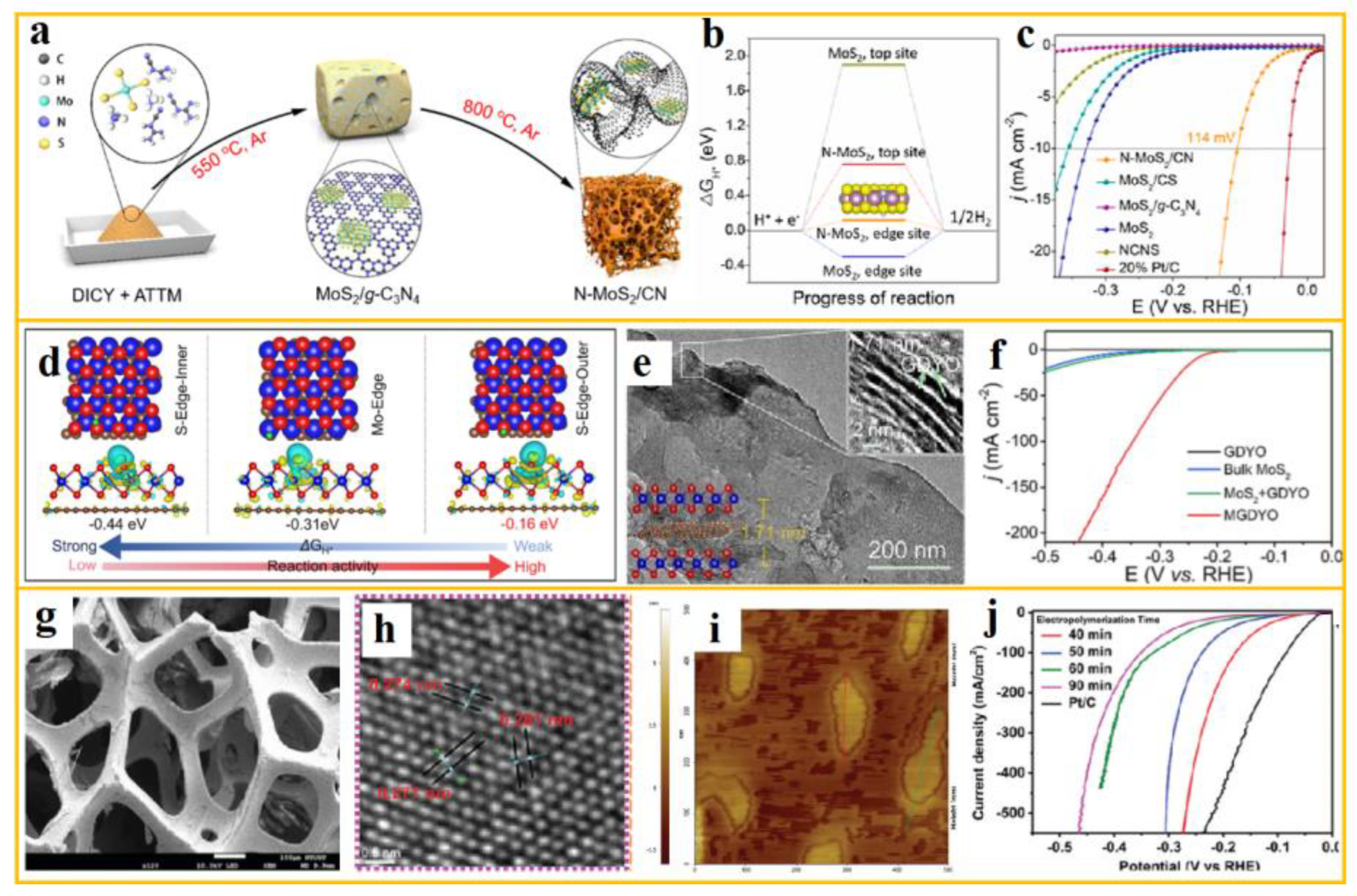

Jong Min Lee et al. achieved a "0D/3D" structure of N-doped MoS

2 anchored to a carbon grid based on a self-template strategy [

115]. a shows the synthesis schematic of N-MoS

2/CN. This self-template strategy has been demonstrated to optimize both the catalyst edge structure and electrons simultaneously. b illustrates the adsorbed ΔG

H* on different sites of the original MoS

2 and N-MoS

2. The edge sites on the MoS

2 crystal are activated by nitrogen. The 3D mesoporous carbon substrate has a graded porous structure, which facilitates the transfer of H

+ in the electrolyte. The N-MoS

2/CN catalyst demonstrates remarkable HER performance. c shows the polarization curve of the sample in 0.5 M H

2SO

4, corrected by iR, with an overpotential of 114 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm

-2.

Figure 10.

(

a) Schematic diagram of N-MoS

2/CN self-template synthesis; (

b) ΔG

H* of H* adsorption on different sites of original MoS

2 and N-MoS

2; (

c) Polarization curve of the sample in 0.5 M H

2SO

4 corrected by iR (from ref. [

115], with permission); (

d) Top view of MGDYO, where hydrogen atoms are adsorbed at the edge position and the corresponding charge density difference and calculated ΔG

H*; (

e) TEM images of MGDYO; (

g) LSV curve of MGDYO (from ref. [

116], with permission); (

h-

j) SEM, HRTEM and AFM images of Na chitosan/MoS

2/PANI/NF; (

k) In 0.5 M H

2SO

4 LSV curve in solution (from ref. [

117], with permission).

Figure 10.

(

a) Schematic diagram of N-MoS

2/CN self-template synthesis; (

b) ΔG

H* of H* adsorption on different sites of original MoS

2 and N-MoS

2; (

c) Polarization curve of the sample in 0.5 M H

2SO

4 corrected by iR (from ref. [

115], with permission); (

d) Top view of MGDYO, where hydrogen atoms are adsorbed at the edge position and the corresponding charge density difference and calculated ΔG

H*; (

e) TEM images of MGDYO; (

g) LSV curve of MGDYO (from ref. [

116], with permission); (

h-

j) SEM, HRTEM and AFM images of Na chitosan/MoS

2/PANI/NF; (

k) In 0.5 M H

2SO

4 LSV curve in solution (from ref. [

117], with permission).

In the field of special designs, Considerable headway has been achieved in the synthesis of MoS

2 heterostructures with graphdiyne oxide sandwiched in between, as demonstrated by Wu et al. This synthesis utilized an electrostatic self-assembly strategy, a method that has garnered significant attention in recent research [

116]. The SEM and TEM images of MGDYO are shown in e. The insertion of a GDYO layer has been demonstrated to suppress the stacking of MoS

2, to increase the area of the heterojunction interface, and to enlarge its interlayer spacing. Consequently, MGDYO demonstrates enhanced HER performance, as evidenced by the LSV curve depicted in f and a lower overpotential of 237 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm

-2. In addition, they revealed in detail the "structure activity" relationship between the synthesized layer by layer MGDYO catalyst and the enhanced HER activity through DFT calculations. The simulated structure is shown in d, paving the way for 2D TMDs heterostructures as high-efficiency catalysts for HER.

Notably, the synergistic effect of disparate components in heterostructures has been demonstrated to significantly enhance HER performance. Cheng Yu Tsai et al. constructed Na chitosan/MoS

2/PANI/NF composite materials using wet chemical methods [

117]. The SEM, HRTEM, and AFM images are shown in g-i, respectively. The combination of a P-N heterojunction for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution, along with the combination of N- type exfoliated MoS

2 and P-type acid doped PANI nanosheets formed through an exfoliation process and electropolymerization pathway, greatly enhances the conductivity and stability of MoS

2. In an acidic environment, the LSV curve is shown in j. At a current density of 50 mA cm

−2 the overpotential is only 42.7 mV, demonstrating great potential in the preparation of HER composite materials with P-N heterojunction interfaces.

5. Summary and Outlook

Due to its unique crystal structure, band structure, and low hydrogen adsorption free energy, MoS2 has demonstrated significant potential in the field of HER, garnering considerable attention. Nevertheless, the current challenges associated with MoS2 catalysts, such as insufficient activity, limited lifespan, and inadequate selectivity in the HER process, highlight the need for further investigation into the underlying catalytic mechanisms. Advancements in synthetic methodologies aimed at regulating the electronic structure of MoS2 to enhance its HER performance are expected in the future, addressing the demands of industrial applications. Therefore, it is essential to design appropriate structural forms to improve the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance of MoS2.

Future research on MoS2 catalysts should focus on the following aspects:

In the context of enhancing synthesis techniques, it is recognized that, while various methods exist for the preparation of MoS2, each approach has its own distinct limitations. Consequently, exploring the integration of diverse synthesis methods, integrating the advantages of each, and developing novel processes capable of producing high-quality MoS2 materials in substantial quantities is a logical and necessary step.

In terms of morphology design, it is essential to continue exploring novel synthesis strategies. Alongside existing self-assembly techniques, template methods, and well-established approaches like ALD, the development of precise nanostructuring methods to shape MoS2 is crucial. Microfluidic technology can be employed to synthesize MoS2 nanoparticles or nanowires with uniform sizes and distinct morphologies. Their high specific surface area maximizes active edge sites, thereby enhancing adsorption and conversion in HER.

In the field of phase engineering, the synthesis of ultra-thin 1T/1T′-MoS2 nanosheets with high phase purity and crystallinity is feasible. Alternatively, the phase transition mechanism of MoS2 between different phases (e.g., 2H, 1T, etc.) can be thoroughly investigated to develop mild and efficient control strategies. These two aspects of phase engineering research are interrelated and complementary. Both approaches facilitate the precise preparation and stable maintenance of specific phases, while improving electronic conductivity to enhance HER performance.

Defect engineering is essential in the study of MoS2 catalysts. Introducing defects has been shown to effectively enhance the local electronic structure and increase the number of active sites. The use of advanced atomic-level manipulation techniques enables the precise introduction of defects, such as sulfur and molybdenum vacancies. These methods also allow for a detailed investigation of how defect concentration and distribution influence HER activity. This investigation seeks to optimize the electronic structure and adsorption properties of the material.

The development of innovative heterostructure synthesis methods has become a highly dynamic and actively explored area of research. This is driven by the exploration of more diverse composite materials and novel synthesis pathways. For example, the preparation of composite heterostructures of MoS2 with metal or non-metal nanoparticles through in-situ growth combined with plasma treatment is a particularly active research focus. In addition, other research areas focus on optimizing the electron transfer process through synergistic effects, as well as enhancing the conductivity, stability, and catalytic activity of materials to achieve efficient HER catalysis.