1. Introduction

Hypertension is one of the most prevalent cardiovascular diseases and a leading cause of mortality worldwide, commonly contributing to conditions such as stroke and acute myocardial infarction [

1]. Numerous risk factors are associated with the development of hypertension, including obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, family history, personality traits, and psychological factors such as stress. Both genetic predisposition and environmental elements—such as sedentary behavior and excessive sodium intake—are also frequently cited [

2,

3,

4,

5].

Despite the extensive literature on hypertension, relatively little attention has been devoted to the influence of emotional and psychological factors—such as stress, anxiety, hostility, and impulsivity—on blood pressure regulation [

6,

7,

8]. It is hypothesized that stress triggers sympathetic nervous system activation, resulting in increased blood pressure [

9,

10,

11]. Stressful experiences—ranging from interpersonal conflict to financial strain and social isolation—are known to provoke physiological and behavioral responses that can disrupt neuroendocrine and immune function, leading to diverse individual outcomes [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Bone tissue, similarly dynamic, undergoes continuous remodeling throughout life to maintain structural integrity and mineral homeostasis. Activities involving mechanical loading promote osteogenesis and help counteract bone loss [

19,

20]. Notably, hypertension has been linked to alterations in calcium metabolism and increased bone resorption, which may contribute to bone mineral density reduction in hypertensive individuals [

21,

22,

23].

With the global rise in aging populations and lifestyle-related conditions—including physical inactivity, stress, and dietary imbalances—the prevalence of both hypertension and osteoporosis has escalated [

24,

25,

26]. These disorders often coexist, influenced by a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors [

27,

28].

Given the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases and emotional stress in the general population, there is a growing need for integrated research that examines physiological, morphological, and biochemical alterations in these conditions [

29,

30].

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of acute and chronic stress, in combination with hypertension, on the skeletal system through histological assessment and microcomputed tomography (Micro-CT) analysis. Our findings may provide further insight into the interactions between cardiovascular and skeletal health under stress-related conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Aspects and Experimental Design

This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals at the University of São Paulo/Brazil, at the School of Dentistry of Ribeirão Preto, registered under number 0027/2021R2. Male Hannover strain rats (n = 20) and SHR (spontaneous hypertensive rats) (n = 20), weighing approximately 250 grams at the start of the experiments, were used. The animals were obtained from the Central Animal Facility of the University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto campus, Brazil. The animals were kept in individual cages, in a room with controlled temperature (24 ± 1 °C), with a 12-hour light/dark cycle (light cycle starting at 7:00 AM) and had ad libitum access to water and food. The experimental protocols were conducted in a quiet room during the morning and in the same location (same laboratory) to minimize variations. Animal care, including manual recording of body weight, food intake, water consumption, and cage alterations, occurred daily at 8:00 AM during the light cycle. The rats were left undisturbed throughout the entire dark cycle.

The animals were randomly divided into three main groups: control group without stress (S); group with acute stress (A); and group with chronic varied stress (C). Each group was subdivided into normal rats and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Groups A and C were further subdivided into control and stress-exposed groups, totaling 40 animals.

2.2. Acute Stress Protocol

Sixteen animals, both normal and SHR, were subjected to a protocol involving a single episode of stress (acute stress for 2 hours – physical restraint). The animals were placed in a metal box measuring 15 cm in length, 5 cm in diameter, with adequate ventilation throughout its length. The end of the box was closed, and the animals were in a state of physical restraint for 2 hours.

2.3. Chronic Varied Stress Protocol

Chronic varied stress is an effective protocol as it simulates frequent daily conditions to which individuals are exposed. Several studies in the literature use the chronic stress protocol for different analyses, using different stressors, generally 1 to 3 times a day, for varied periods. A chronic varied stress protocol was carried out according to a previous study by our research group [

31,

32,

33]. In this protocol, five distinct forms of stress were implemented over a total period of 10 days. The stressful situations were initiated in the morning, according to the following description: Days 01 and 06: agitation. The rats were individually placed in a plastic box on a shaker table for 15 minutes. The average rotation speed was 50 rpm. Days 02 and 07: forced swimming. The rats swam for 15 minutes in a circular plastic container, 54 cm deep and 47 cm in diameter, filled with water to a depth of 40 cm, preventing contact with the upper or lower edges. The water temperature was controlled and maintained at 25 ± 1 °C. Days 03 and 08: physical restraint. The animals were placed in a metal box measuring 15 cm in length and 5 cm in diameter, with adequate ventilation throughout its length. The end of the box was closed, and the animals were physically restrained for two hours, limiting their movement. Days 04 and 09: cold stress. The rats, in individual plastic boxes, were exposed to hypothermia in the freezer (10 °C) for a period of 30 minutes. Days 05 and 10: water deprivation. The water source was removed for a period of 24 hours (

Figure 1).

2.4. Tibia Collection and Microtomographic Evaluation

At the end of the experiment, the animals were euthanized, having been previously anesthetized with 4% xylazine (14 mg/kg) and 10% ketamine (100 mg/kg), via intraperitoneal injection, and were subjected to euthanasia by conscious decapitation 24 hours after the last stress exposure. In rats subjected to acute stress, euthanasia was performed immediately after the stress. Subsequently, the right and left tibias of each animal were removed, dissected, and fixed in 10% formaldehyde phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 48 hours.

All samples were scanned using a micro-CT (Skyscan model 1172, Bruker-Micro-CT®, Kontich, Belgium). The region of interest (ROI) started at the marginal crest of the tibia and extended 2mm, corresponding to 21 slices. The device was set to 70 kV and 142 uA. A filter (0.5) was used, and the sample was rotated 180 degrees with a rotation step of 0.5, generating an acquisition time of 41 minutes per sample. The NRecon software program (Bruker, Belgium) was used to reconstruct the three-dimensional images. Subsequently, the images were aligned in the coronal, transaxial, and sagittal planes using the DataViewer program.

2.5. Histological Analysis

The samples were removed, dissected, and maintained in 10% EDTA solution until complete decalcification. The samples were left in 10% buffered formaldehyde for 24 to 48 hours, then transferred to 10% EDTA under constant agitation for decalcification until complete decalcification. The specimens were processed histologically for inclusion in paraffin enriched with Histosec polymer (Merck KGaA®, Darmstadt, Germany). Coronal sections of 5 μm thickness were obtained and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and Masson’s trichrome. All histological slides were coded according to the experimental groups. An experienced examiner evaluated them blind. All images were captured under identical camera settings, including white balance, gain, and exposure. The exposure time was selected to limit the occurrence of saturated intensity pixels. A total area of 144 × 106 pixels² was evaluated for each sample.Virtual microscopy, data management, and image analysis were performed with the aid of a digital camera attached to the Zeiss AxioImager Z2 light microscope (Oberkochen, Germany), with original magnifications of ×20 and ×40. Subsequently, the digital images were analyzed using AxioVision 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The results obtained from the micro-CT and histomorphometric parameters were obtained from the linear measurements at the mid-palatal suture and DI, and the histomorphometric parameters were subjected to the Shapiro-Wilk normality test before the statistical tests to check the normality of the values. Subsequently, the data were evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test to explore the differences between the means across the periods, and the Student’s t-test was used to compare the means between two groups at each period. We used Statistical v.10.0 software with a significance level of 5%. The continuous variables are shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results

The descriptive statistical analyses and their normality, for all the variables included in the objectives of this study, showed that all of them are normal (p > 0.05), according to the significance of the Shapiro-Wilk test.

3.1. Linear Measurements of the Tibia in Micro-CT Imagens

Three-dimensional (3D) and two-dimensional (2D) microtomographic images of the tibial bone in groups G1 to G10 are shown in

Figure 2. The analysis focused on the proximal region of the bone. The reference point was determined at the end of the growth plate, “Top selection,” and then 2mm down, corresponding to 21 slices, to reach “Bottom selection.” The bone area in the trabecular and cortical regions was delineated starting from the coronal section. The percentage of bone volume was quantified between the groups. A significant difference was observed between group G1 (control and normal rat) and G8 (normal rat with chronic stress), as well as between G4 (normal rat with acute stress) and G5 (spontaneously hypertensive rat control). No significant statistical difference was found between the other groups.

3.2. Descriptive Histology

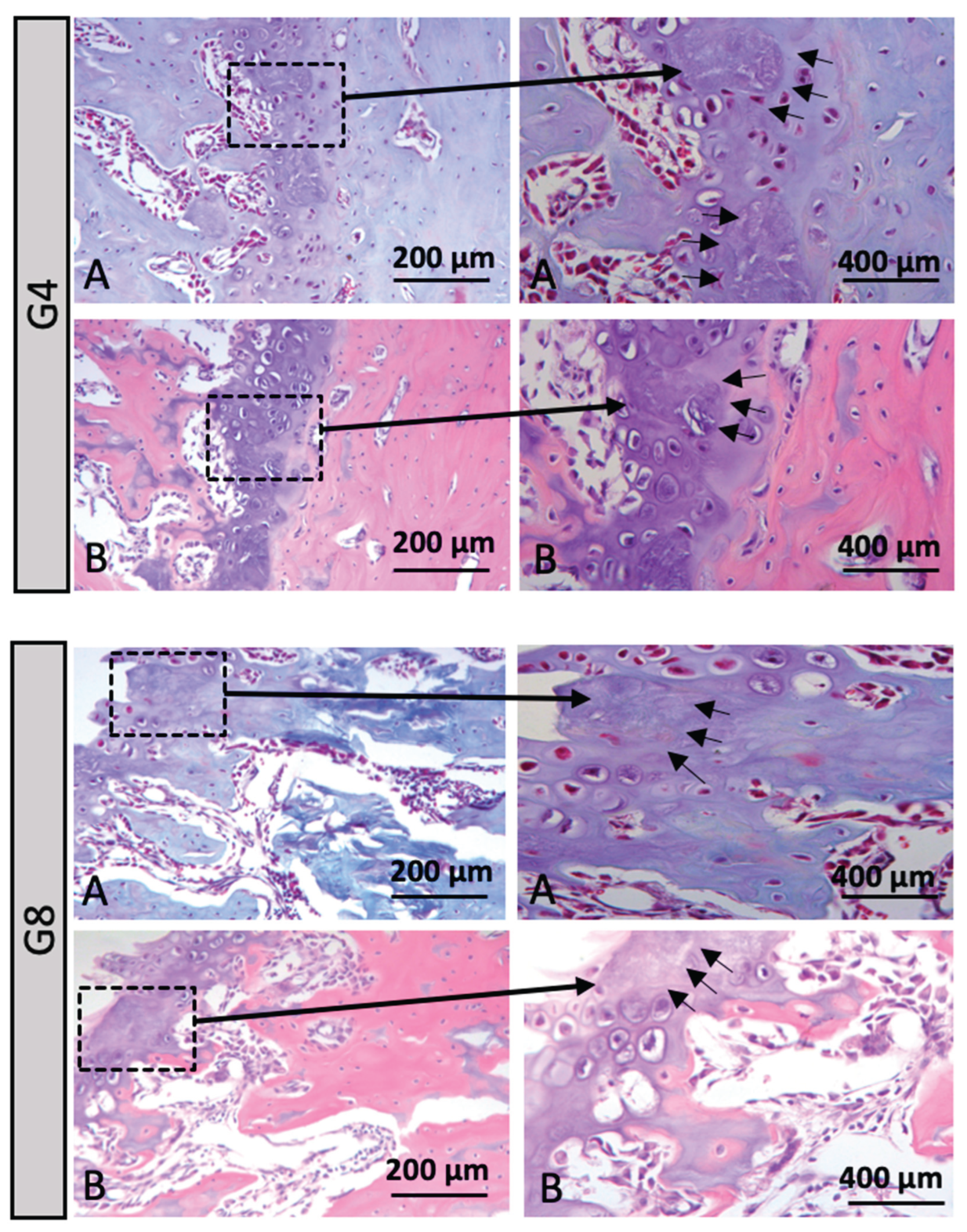

Qualitative analysis of the histological sections was performed using Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) and Masson's Trichrome staining, both applied to assess overall tissue morphology. Overall, all experimental groups exhibited preserved connective tissue architecture, with no evidence of acute or chronic inflammatory infiltrates. However, distinct morphological alterations were observed in groups G4 and G8, particularly concerning the structural organization of the growth plate, suggesting potential effects of the experimental conditions on bone maturation and remodeling mechanisms in this region.

Groups G1 and G2 (Control): In the distal region of the tibia, Group G1 (normotensive rats) exhibited a clearly preserved growth plate (red arrow), whereas Group G2 (hypertensive rats – SHR) showed an increased amount of bone trabeculae (yellow arrow). Despite these structural differences, the overall tissue morphology remained preserved in both groups (

Figure 3). Groups G3 and G4 (Acute Stress – normotensive rats): In the distal region of the tibia, Group G3 (control for the acute stress group) exhibited a morphological pattern similar to that observed in Group G1, with a clearly visible growth plate (red arrow). Group G4 (subjected to acute stress), despite exposure to the stressor, maintained histological features comparable to those of Group G3, suggesting that the acute stress episode did not induce evident structural alterations in bone architecture (

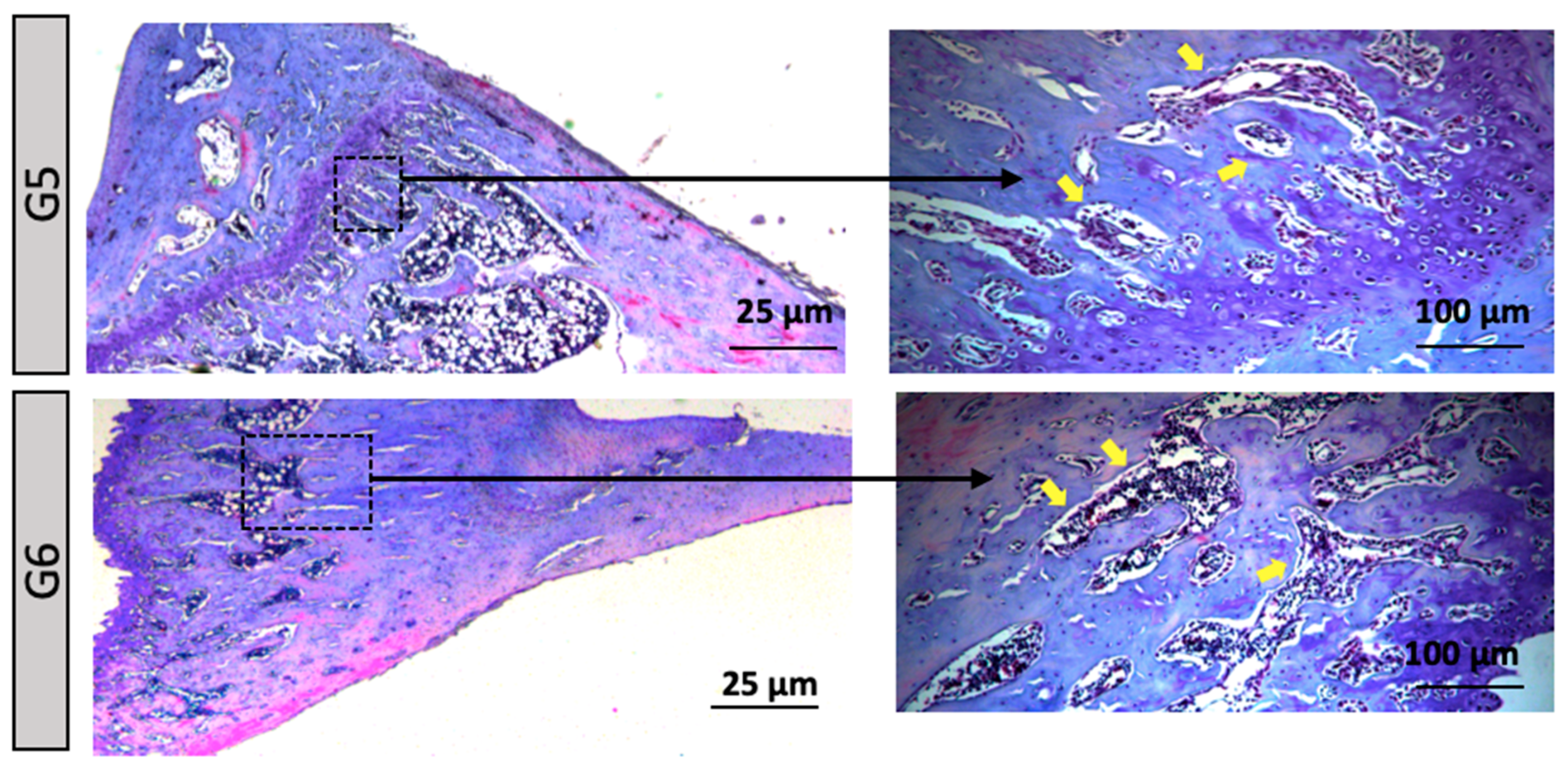

Figure 4). Groups G5 to G6 (Acute Stress/ Hypertensive Rats): In the distal region of the tibial bone, an increase in the number of bone trabeculae was observed, suggesting that hypertension exacerbated the effects of acute stress on extracellular matrix remodeling (

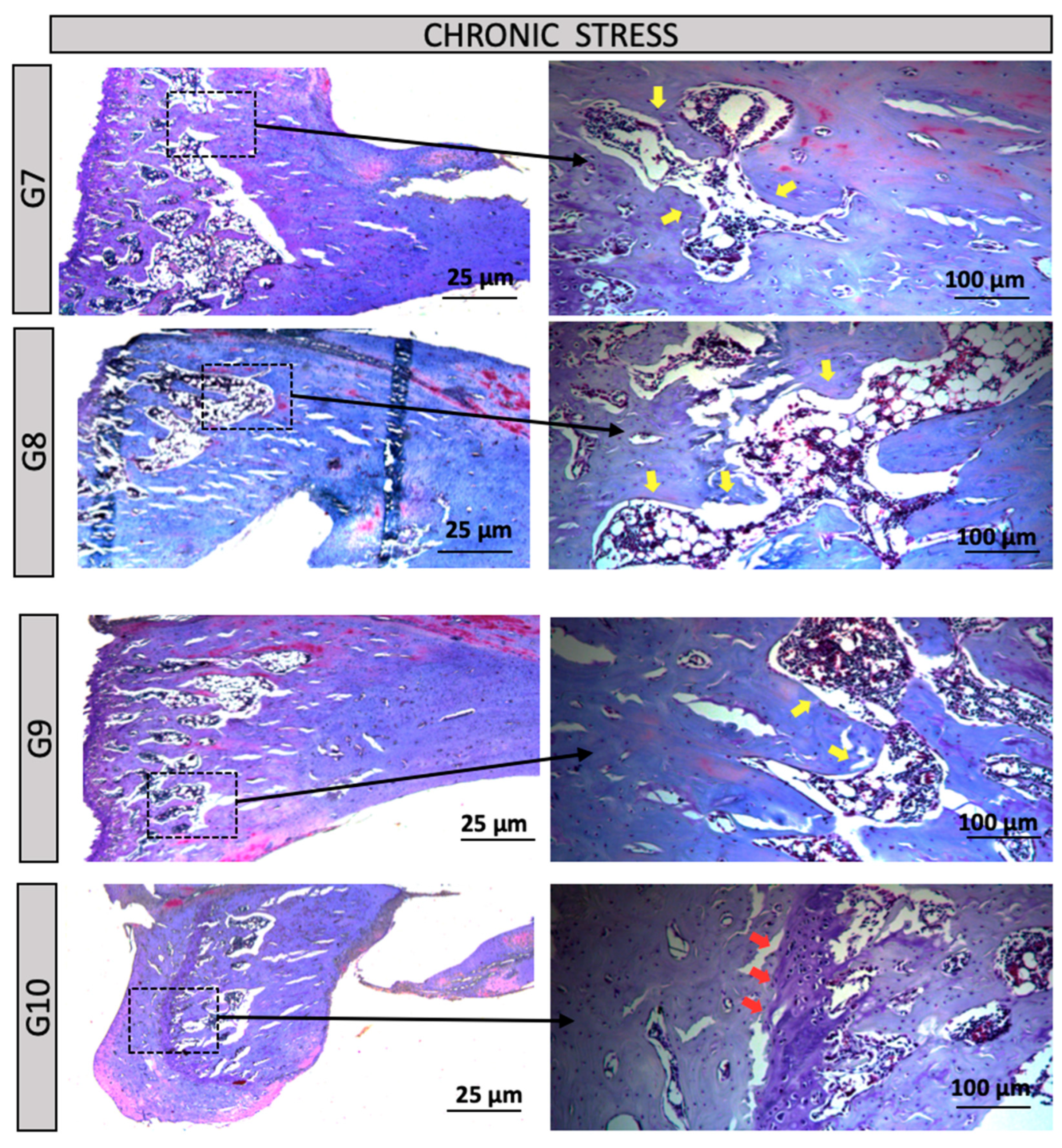

Figure 4). Chronic Stress Groups (G7 to G10): G7 (normotensive, control under chronic stress conditions) – A morphological pattern similar to G1 (control) was observed. G8 (normotensive, subjected to chronic stress) – This group exhibited the highest content and organization of bone trabeculae, with the presence of red-stained tissue indicating mature bone. MicroCT results revealed a significant difference compared to G1, suggesting a pronounced adaptive response to prolonged stress. G9 and G10 (hypertensive) – Both groups showed a morphology similar to the control group G2, without indicating alterations due to chronic stress associated with hypertension (

Figure 5).

When evaluating the micro-CT results, it was observed that Group G4 showed the lowest percentage of bone formation, followed by Group G8. Due to this significant difference between the groups, only Groups G4 and G8 were selected for histological imaging in

Figure 6, in order to better illustrate the findings. In these images, a marked increase in tissue staining was observed using Hematoxylin and Eosin, as well as Masson's Trichrome. Additionally, in the growth plate, alterations in cartilage morphology were identified, including areas of necrosis indicated by black arrows (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of acute and chronic stress, in association with hypertension, on bone metabolism in rats. Bone remodeling is a dynamic process involving the balance between bone modeling and resorption. Our observations indicate that both acute and chronic stress significantly affect bone architecture, with notable differences between normotensive and hypertensive groups.

In rats subjected to acute stress (G4 and G5), an increase in trabecular density was observed, especially in hypertensive rats (G5). This may represent an adaptive response to stress, mediated by sympathetic nervous system activation and modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [

34,

35]. Similar studies report that acute stress can stimulate temporary bone resorption or, in certain contexts, increase bone formation as a compensatory mechanism [

36,

37].

In rats exposed to chronic stress (G8), a more pronounced reorganization of trabecular bone architecture was observed, suggesting structural adaptation. Chronic stress has been shown to affect the balance between osteoblasts and osteoclasts [

38], although in this study, bone formation remained relatively stable, indicating adaptive rather than degenerative changes [

39].

Hypertension, especially in groups G5 and G10, also influenced bone remodeling. It may disrupt the balance between bone formation and resorption, amplifying the effects of stress [

40]. For example, the increased trabecular density in G5 may reflect an adaptive response to the combined effects of hypertension and stress [

41].

Although previous studies have examined the isolated effects of stress and hypertension on bone [

42,

43], their interaction remains less understood. Our findings highlight the importance of managing both conditions to preserve skeletal integrity. MicroCT analysis showed that G8 (normotensive with chronic stress) had the highest trabecular bone volume, supporting evidence that chronic stress can trigger adaptive bone formation [

44,

45]. In contrast, hypertensive rats (G9 and G10) did not show significant bone changes, aligning with studies indicating that hypertension alone may not significantly alter bone structure over short periods [

46,

47].

Group G4 (normotensive with acute stress) showed reduced bone volume compared to G1 (control), suggesting an unfavorable response to acute stress, consistent with findings that acute stress elevates cortisol levels, impairing bone homeostasis [

48,

49]. However, G5 (hypertensive with acute stress) showed no additional changes, indicating that short-term combined exposure may not further alter bone microarchitecture [

50,

51].

Histological analysis using Hematoxylin and Eosin and Masson’s Trichrome stains revealed significant changes in the growth plate, notably in G4 and G8, with necrotic areas corresponding to reduced bone volume and mineralization seen in MicroCT [

52,

53]. These findings suggest that acute stress, especially when combined with hypertension, may impair growth plate integrity and bone formation [

54,

55].

Despite some limitations—such as the use of SHR rats and the short experimental period—this study provides relevant clinical insights. Longer exposure periods might reveal more extensive remodeling or degenerative changes [

56,

57,

58]. The limited timeframe may also have prevented detection of cumulative effects linked to chronic stress and hypertension [

59,

60].

These results emphasize the clinical relevance of monitoring bone health in individuals exposed to psychosocial stress and hypertension. Future studies should investigate molecular pathways, inflammatory mediators, and therapeutic strategies—both pharmacological and behavioral—to mitigate bone loss and promote skeletal health.

5. Conclusions

The conclusion of the study highlights the relationship between stress, hypertension, and bone remodeling, demonstrating that these conditions can negatively impact bone health. Through histological and radiographic imaging techniques, alterations in bone formation and cartilage morphology were observed, particularly in groups exposed to chronic stress and hypertension. Despite limitations such as the duration of exposure and the use of an animal model, the results emphasize the impact of physiological stressors on bone metabolism. Future studies should explore longer experimental periods and pharmacological or behavioral therapies targeting bone remodeling. These advancements could contribute to improving prevention and treatment strategies for bone diseases, particularly in patients with chronic stress and cardiovascular conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.P. and J.P.M.I.; methodology, M.R.P., D.L.P. and S.F.; validation, C.A.R., D.V.B. and R.L.B.; formal analysis, M.R.P., D.L.P. and S.F.; investigation, D.V.B. and R.L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.P. and J.P.M.I.; writing—review and editing, S.F., D.V.B. and R.L.B.; visualization, C.A.R.; supervision, J.P.M.I.; project administration, J.P.M.I.; funding acquisition, M.R.P., R.L.B. and J.P.M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FAPESP (São Paulo State Research Support Foundation) grant number 2023/06853-7 and 2021/08618-0. J.P.M.I. is a CNPq (The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development/Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) PQ1C research fellow (No. 302999/2024-8) and R.L.B. is a CNPq PQ1C research fellow (No. 302545/2025-5)

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals at the University of São Paulo/Brazil, at the School of Dentistry of Ribeirão Preto, registered under number 0027/2021R2, January 11, 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dzau, V.J.; Hodgkinson, C.P. Precision Hypertension. Hypertension. 2024, 81, 702–708. [CrossRef]

- Ondimu, D.O.; Kikuvi, G.M.; Otieno, W.N. Risk Factors for Hypertension Among Young Adults (18-35) Years Attending in Tenwek Mission Hospital, Bomet County, Kenya in 2018. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 33, 210. [CrossRef]

- Nwoke, O.C.; Nubila, N.I.; Ekowo, O.E.; Nwoke, N.C.; Okafor, E.N.; Anakwue, R.C. Prevalence of Prehypertension, Hypertension, and Its Determinants Among Young Adults in Enugu State, Nigeria. Niger. Med. J. 2024, 65, 241–254.

- Wyszyńska, J.; Łuszczki, E.; Sobek, G.; Mazur, A.; Dereń, K. Association and Risk Factors for Hypertension and Dyslipidemia in Young Adults from Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2023, 20, 982. [CrossRef]

- Vo, H.K.; Nguyen, D.V.; Vu, T.T.; Tran, H.B.; Nguyen, H.T.T. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Prehypertension/Hypertension Among Freshman Students from the Vietnam National University: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health. 2023, 23, 1166. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Li, N.; Li, W.A.; Khan, H. Association Between Psychosocial Stress and Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurol. Res. 2017, 39, 573–580. [CrossRef]

- Kluknavsky, M.; Balis, P.; Liskova, S.; et al. Dimethyl Fumarate Prevents the Development of Chronic Social Stress-Induced Hypertension in Borderline Hypertensive Rats. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024, 13, 947. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ye, C.; Kong, L.; et al. Independent Associations of Education, Intelligence, and Cognition with Hypertension and the Mediating Effects of Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Hypertension. 2023, 80, 192–203. [CrossRef]

- Franco, C.; Sciatti, E.; Favero, G.; Bonomini, F.; Vizzardi, E.; Rezzani, R. Essential Hypertension and Oxidative Stress: Novel Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14489. [CrossRef]

- Ojangba, T.; Boamah, S.; Miao, Y.; et al. Comprehensive Effects of Lifestyle Reform, Adherence, and Related Factors on Hypertension Control: A Review. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich). 2023, 25, 509–520. [CrossRef]

- Wildenauer, A.; Maurer, L.F.; Rötzer, L.; Eggert, T.; Schöbel, C. The Effects of a Digital Lifestyle Intervention in Patients with Hypertension: Results of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich). 2024, 26, 902–911. [CrossRef]

- Muddle, S.; Jones, B.; Taylor, G.; Jacobsen, P. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association Between Emotional Stress Reactivity and Psychosis. Early Interv. Psychiatry. 2022, 16, 958–978. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ortiz, J.L.; Islas-Valle, R.M.; Jiménez-Ortiz, J.D.; Pérez-Lizárraga, E.; Hernández-García, M.E.; González-Salazar, F. Emotional Exhaustion, Burnout, and Perceived Stress in Dental Students. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 4251–4259. [CrossRef]

- Bajaña, L.A.C.; Campos Lascano, L.; Jaramillo Castellon, L.; et al. The Prevalence of the Burnout Syndrome and Factors Associated in the Students of Dentistry in Integral Clinic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Dent. 2023, 2023, 5576835. [CrossRef]

- Minshew, L.M.; Bensky, H.P.; Zeeman, J.M. There's No Time for No Stress! Exploring the Relationship Between Pharmacy Student Stress and Time Use. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 279. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H. Positive Effects on Emotional Stress and Sleep Quality of Forest Healing Program for Exhausted Medical Workers During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 3130. [CrossRef]

- Kweon, J.; Kim, Y.; Choi, H.; Im, W.; Kim, H. Enhancing Sleep and Reducing Occupational Stress Through Forest Therapy: A Comparative Study Across Job Groups. Psychiatry Investig. 2024, 21, 1120–1128. [CrossRef]

- Kane, H.S.; Wiley, J.F.; Dunkel Schetter, C.; Robles, T.F. The Effects of Interpersonal Emotional Expression, Partner Responsiveness, and Emotional Approach Coping on Stress Responses. Emotion. 2019, 19, 1315–1328. [CrossRef]

- Hart, N.H.; Newton, R.U.; Tan, J.; et al. Biological Basis of Bone Strength: Anatomy, Physiology and Measurement. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2020, 20, 347–371.

- Yang, N.; Liu, Y. The Role of the Immune Microenvironment in Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 3697–3707. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.L.; Tan, M.Y.; Wang, G.P.; Zhu, S.X.; Shu, Q.C. The Association Between Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet and Bone Mineral Density in US Adults: Evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2011-2018). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 23043. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Li, Q.; Yang, C.; et al. Waist-to-Height Ratio Is a Stronger Mediator in the Association Between DASH Diet and Hypertension: Potential Micro/Macro Nutrients Intake Pathways. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 2189. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.Y.; Zhu, S.X.; Wang, G.P.; Liu, Z.X. Impact of Metabolic Syndrome on Bone Mineral Density in Men Over 50 and Postmenopausal Women According to U.S. Survey Results. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7005. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, V.; Haffner-Luntzer, M. Interaction Between Bone and Immune Cells: Implications for Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 123, 14–21. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Lu, K.; Li, C.; et al. Association Between Systemic Inflammatory Response Index and Bone Turnover Markers in Chinese Patients with Osteoporotic Fractures: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 2024, 11, 1404152. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Cline-Smith, A.; Shashkova, E.; Perla, A.; Katyal, A.; Aurora, R. T-Cell Mediated Inflammation in Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 687551. [CrossRef]

- Nakagami, H.; Morishita, R. Clin Calcium. 2013, 23, 497–503.

- Huang, Y.; Ye, J. Association Between Hypertension and Osteoporosis: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 434. [CrossRef]

- Paulini, M.R.; Aimone, M.; Feldman, S.; Buchaim, D.V.; Buchaim, R.L.; Issa, J.P.M. Relationship of Chronic Stress and Hypertension with Bone Resorption. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 21. [CrossRef]

- Schemenz, V.; Scoppola, E.; Zaslansky, P.; Fratzl, P. Bone Strength and Residual Compressive Stress in Apatite Crystals. J. Struct. Biol. 2024, 216, 108141. [CrossRef]

- Loyola, B.M.; Nascimento, G.C.; Fernández, R.A.; et al. Chronic Stress Effects in Contralateral Medial Pterygoid Muscle of Rats with Occlusion Alteration. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 164, 369–375. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.A.R.; Pereira, Y.C.L.; Iyomasa, D.M.; et al. Metabolic and Vascular Pattern in Medial Pterygoid Muscle is Altered by Chronic Stress in an Animal Model of Hypodontia. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 185, 70–78. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Y.C.L.; Nascimento, G.C.; Iyomasa, D.M.; et al. Exodontia-Induced Muscular Hypofunction by Itself or Associated to Chronic Stress Impairs Masseter Muscle Morphology and Its Mitochondrial Function. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2019, 82, 530–537. [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.M.; Singh, P.; Khrimian, L.; et al. Mediation of the Acute Stress Response by the Skeleton. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 890–902. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.K.; Liu, J.X.; Zhou, Z.K.; Zheng, C.X.; Sui, B.D.; Yuan, Y.; Kong, L.; Jin, Y.; Chen, J. Osteoporosis under psychological stress: mechanisms and therapeutics. Life Med. 2024, 3. [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Adachi, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Kubo, K.Y. Chronic Psychological Stress as a Risk Factor of Osteoporosis. J UOEH. 2015, 37, 245–253. [CrossRef]

- Henneicke, H.; Li, J.; Kim, S.; Gasparini, S.J.; Seibel, M.J.; Zhou, H. Chronic Mild Stress Causes Bone Loss via an Osteoblast-Specific Glucocorticoid-Dependent Mechanism. Endocrinology. 2017, 158, 1939–1950. [CrossRef]

- Wippert, P.M.; Rector, M.; Kuhn, G.; Wuertz-Kozak, K. Stress and Alterations in Bones: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017, 8, 96. [CrossRef]

- Tiyasatkulkovit, W.; Promruk, W.; Rojviriya, C.; Pakawanit, P.; Chaimongkolnukul, K.; Kengkoom, K.; Teerapornpuntakit, J.; Panupinthu, N.; Charoenphandhu, N. Impairment of Bone Microstructure and Upregulation of Osteoclastogenic Markers in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12293. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R.M.; Silva, A.B.; Lima, R.M. Relationship of Chronic Stress and Hypertension with Bone Resorption. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 10, 21.

- Ye, Z.; Lu, H.; Liu, P. Association Between Essential Hypertension and Bone Mineral Density: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 68916–68927. [CrossRef]

- Foertsch, S.; Haffner-Luntzer, M.; Kroner, J.; et al. Chronic psychosocial stress disturbs long-bone growth in adolescent mice. Dis Model Mech., 2017, 10, 1399–1409. [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; et al. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 3045–3055.

- Silva, A.B.; et al. Hypertension and Bone Health: The Role of Stress in Bone Remodeling. J. Bone Res. 2020, 8, 123–130.

- Lima, R.M.; et al. Combined Effects of Hypertension and Chronic Stress on Bone Microarchitecture in Rats. Bone Rep. 2021, 14, 100752.

- Smith, J.A.; et al. Acute Stress and Bone Homeostasis: A Review. J. Bone Res. 2015, 33, 567–574.

- Doe, A.B.; et al. Bone Volume Changes in Normotensive and Hypertensive Rats Under Acute Stress. Bone Miner. Metab. 2018, 45, 123–130.

- Müller, R.; et al. No Effect of Short-Term Hypertension on Bone Matrix Mineralization in a Surgical Animal Model in Immature Rabbits. Bone 2011, 49, 792–799.

- Sukhanov, S.; et al. Impairment of Bone Microstructure and Upregulation of Osteoclastogenic Markers in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12345.

- Chen, H.; et al. Improved Trabecular Bone Structure of 20-Month-Old Male Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2014, 95, 282–291.

- Singewald, G.M.; Nguyen, N.K.; Neumann, I.D.; Singewald, N.; Reber, S.O. Effect of Chronic Psychosocial Stress-Induced by Subordinate Colony (CSC) Housing on Brain Neuronal Activity Patterns in Mice. Stress 2009, 12, 58–69. [CrossRef]

- Haffner-Luntzer, M.; et al. Chronic Psychosocial Stress Compromises the Immune Response and Endochondral Ossification During Bone Fracture Healing via β-AR Signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116, 8615–8622. [CrossRef]

- Reber, S.O.; Langgartner, D.; Foertsch, S.; et al. Chronic Subordinate Colony Housing Paradigm: A Mouse Model for Mechanisms of PTSD Vulnerability, Targeted Prevention, and Treatment—2016 Curt Richter Award Paper. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 74, 221–230. [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Londono, I.; Laporte, C.; Villemure, I. Validation of an in vivo micro-CT-based method to quantify longitudinal bone growth of pubertal rats. Bone, 2022, 154, 116207. [CrossRef]

- Mustafy, T.; Benoit, A.; Londono, I.; Moldovan, F.; Villemure, I. Can repeated in vivo micro-CT irradiation during adolescence alter bone microstructure, histomorphometry and longitudinal growth in a rodent model? PLoS One, 2018, 13, e0207323. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R. M.; Phillips, J. E.; Lin, A.; Schwartz, Z.; Boyan, B. D.; Guldberg, R. E. Characterization of a small animal growth plate injury model using microcomputed tomography. Bone, 2010, 46, 1555–1563. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A. C.; Fernandes, R. G.; Carvalho, Y. R.; Balducci, I.; Faig-Leite, H. Bone healing in drill hole defects in spontaneously hypertensive male and female rats' femurs. A histological and histometric study. Arq Bras Cardiol., 2007, 88, 104–109.

- Bastos, M. F.; Brilhante, F. V.; Bezerra, J. P.; Silva, C. A.; Duarte, P. M. Trabecular bone area and bone healing in spontaneously hypertensive rats: a histometric study. Braz Oral Res., 2010, 24, 170–176. [CrossRef]

- Tiyasatkulkovit, W.; Aksornthong, S.; Adulyaritthikul, P.; et al. Excessive salt consumption causes systemic calcium mishandling and worsens microarchitecture and strength of long bones in rats. Sci Rep., 2021, 11, 1850. [CrossRef]

- Sampath, T. K.; Simic, P.; Sendak, R.; et al. Thyroid-stimulating hormone restores bone volume, microarchitecture, and strength in aged ovariectomized rats. J Bone Miner Res., 2007, 22, 849–859. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Division of experimental groups with acute and chronic varied stress protocols. G1 - No stress, normal rat, control; G2 - No stress, SHR rat, control; G3 - Acute stress, normal rat, control; G4 - Acute stress, normal rat, acute stress; G5 - Acute stress, SHR rat, control; G6 - Acute stress, SHR rat, acute stress; G7 - Chronic stress, normal rat, control; G8 - Chronic stress, normal rat, chronic stress; G9 - Chronic stress, SHR rat, control; G10 - Chronic stress, SHR rat, chronic stress.

Figure 1.

Division of experimental groups with acute and chronic varied stress protocols. G1 - No stress, normal rat, control; G2 - No stress, SHR rat, control; G3 - Acute stress, normal rat, control; G4 - Acute stress, normal rat, acute stress; G5 - Acute stress, SHR rat, control; G6 - Acute stress, SHR rat, acute stress; G7 - Chronic stress, normal rat, control; G8 - Chronic stress, normal rat, chronic stress; G9 - Chronic stress, SHR rat, control; G10 - Chronic stress, SHR rat, chronic stress.

Figure 2.

Micro-CT results of tibial bone. A significant difference was observed between group G1 (control and normal rat) and G8 (normal rat with chronic stress), as well as between G4 (normal rat with acute stress) and G5 (spontaneously hypertensive rat control). No significant statistical difference was found between the other groups.

Figure 2.

Micro-CT results of tibial bone. A significant difference was observed between group G1 (control and normal rat) and G8 (normal rat with chronic stress), as well as between G4 (normal rat with acute stress) and G5 (spontaneously hypertensive rat control). No significant statistical difference was found between the other groups.

Figure 3.

Groups G1 and G2 (Control): In the distal region of the tibial bone, a 2.5X and 10X increase. Red arrow = Growth Plate or Cartilage. Yellow arrow = Bone Trabeculae.

Figure 3.

Groups G1 and G2 (Control): In the distal region of the tibial bone, a 2.5X and 10X increase. Red arrow = Growth Plate or Cartilage. Yellow arrow = Bone Trabeculae.

Figure 4.

Groups G3 and G4 (Acute Stress/ Normal Rat): In the distal region of the tibial bone, a 2.5X and 10X increase. Red arrow = Growth Plate or Cartilage. Groups G5 and G6 (Acute Stress/ Hypertensive Rats): In the distal region of the tibial bone, a 2.5X and 10X increase. Yellow arrow = Bone Trabeculae Plate.

Figure 4.

Groups G3 and G4 (Acute Stress/ Normal Rat): In the distal region of the tibial bone, a 2.5X and 10X increase. Red arrow = Growth Plate or Cartilage. Groups G5 and G6 (Acute Stress/ Hypertensive Rats): In the distal region of the tibial bone, a 2.5X and 10X increase. Yellow arrow = Bone Trabeculae Plate.

Figure 5.

Groups G7 and G10 (Chronic Stress): In the distal region of the tibial bone, a 2.5X and 10X increase. Red arrow = Growth Plate or Cartilage. Yellow arrow = Bone Trabeculae Plate.

Figure 5.

Groups G7 and G10 (Chronic Stress): In the distal region of the tibial bone, a 2.5X and 10X increase. Red arrow = Growth Plate or Cartilage. Yellow arrow = Bone Trabeculae Plate.

Figure 6.

A. Hematoxylin and Eosin staining and B. Masson's Trichrome staining, at 20X and 40X magnification. Black arrows = alteration in cartilage morphology with the presence of necrosis in the growth plate in groups G4 (Acute Stress/ Normal Rat) and G8 (Chronic Stress/ Normal Rat).

Figure 6.

A. Hematoxylin and Eosin staining and B. Masson's Trichrome staining, at 20X and 40X magnification. Black arrows = alteration in cartilage morphology with the presence of necrosis in the growth plate in groups G4 (Acute Stress/ Normal Rat) and G8 (Chronic Stress/ Normal Rat).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).