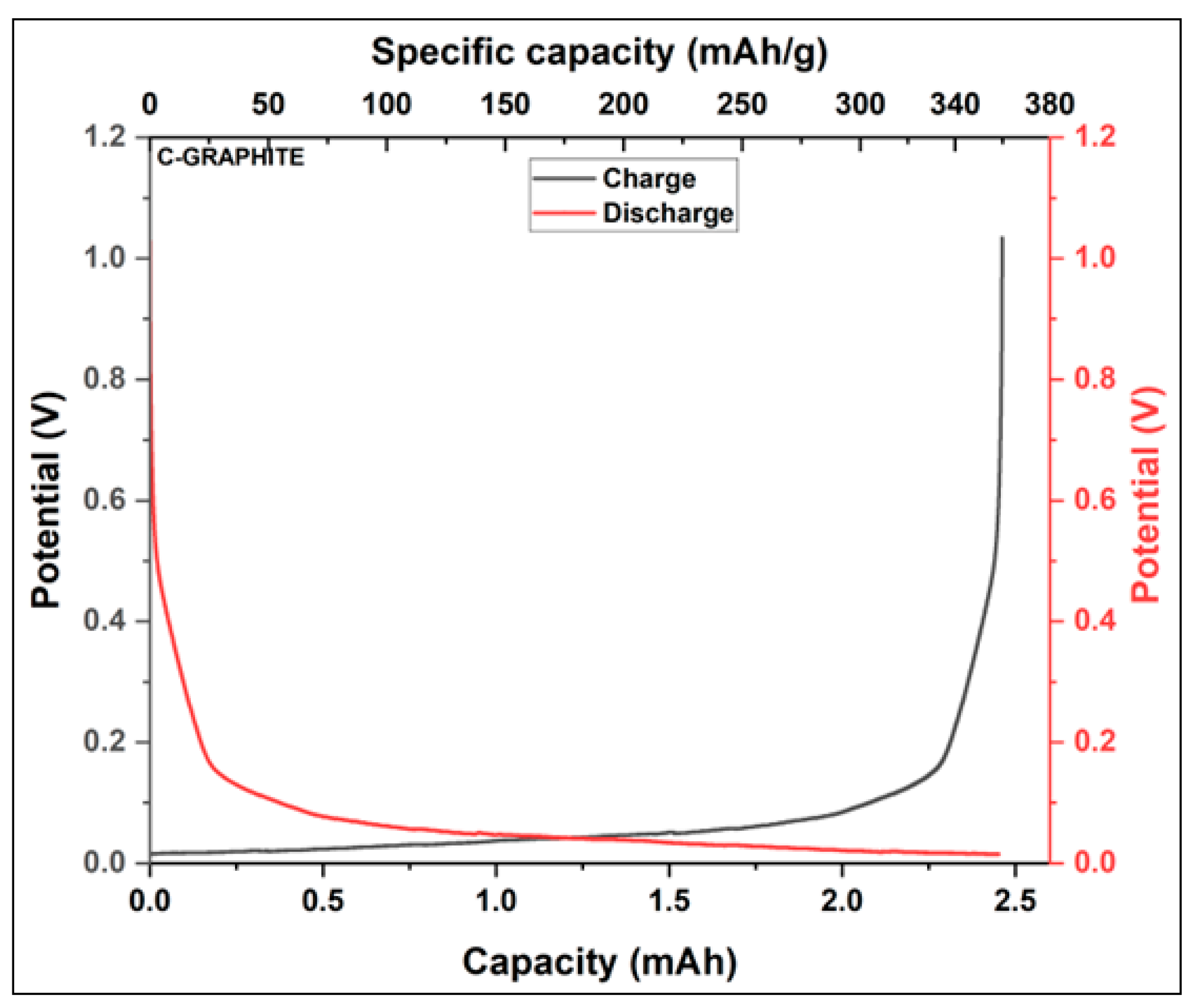

3.3.3.1. Study of Coulombic Efficiency

Table 7 presents the Coulombic efficiency values for the first three cycles of LiFePO4/C, using activated carbon derived from millet cob (MC) and water hyacinth (WH). The results reveal a Coulombic efficiency of approximately 95% for the LFP/MC 1:1, 2:1, and 5:1 sample during the first charge cycle, with slightly better performance observed for LFP/MC 2:1. For the LFP/WH 1:1, 2:1, and 5:1 samples, the Coulombic efficiency reaches around 96%, with the LFP/WH 2:1 sample also showing slightly higher values.

The improvement of the coulombic efficient at second cycle is an indication of the formation of a SEI (Solid Electrolyte Interphase) at the electrode/electrolyte which is a thin layer which is formed on the surface of the anode during the initial charge and discharge cycles of lithium-ion batteries. It results from the reaction between lithium ions and the electrolyte [

62]. During the first charge cycle, a portion of the lithium ions is consumed to form this layer, which explains why the capacity measured during the this first cycle is not representative of the capacity of the battery prior to subsequent cycles [

63]. To study the formation of the SEI, which appears, mainly during the first cycle, and determine the Coulombic efficiency, the batteries were cycled at a current rate of C12 for three cycles.

Coulombic efficiency, which measures the ratio of charge recovered during discharge to the charge stored during charging, is a key indicator of battery reversibility. A high Coulombic efficiency reflects good reversibility, with minimal losses due to side reactions [

64]. However, the formation of the SEI during the first cycle consumes some lithium ions, resulting in a lower initial Coulombic efficiency. Once the SEI stabilizes, subsequent cycles exhibit improved charge recovery, leading to higher efficiency and better system reversibility [

63,

64].

In reality, the thickness of the SEI layer increases with the long period of charge/discharge cycles. This seems to be related to the discharge of the electrolyte ions as Li ions at the carbon surface or/and the diffusion of the electrolyte at the carbon surface. Although the first cycle’s thickness of the SEI is the most important, the subsequent thickening, with time, of the layer with time enhances the consumption of the Li ions and the electrolyte components. This contributes in the decrease in cell conductivity, capacity and coulombic efficiency in a long term [

65,

66].

Further cycling is underway to tackle this effect of the number of cycles on the conductivity, coulombic efficiency and capacity of the cell based on these bio sources carbons based on MC and WH.

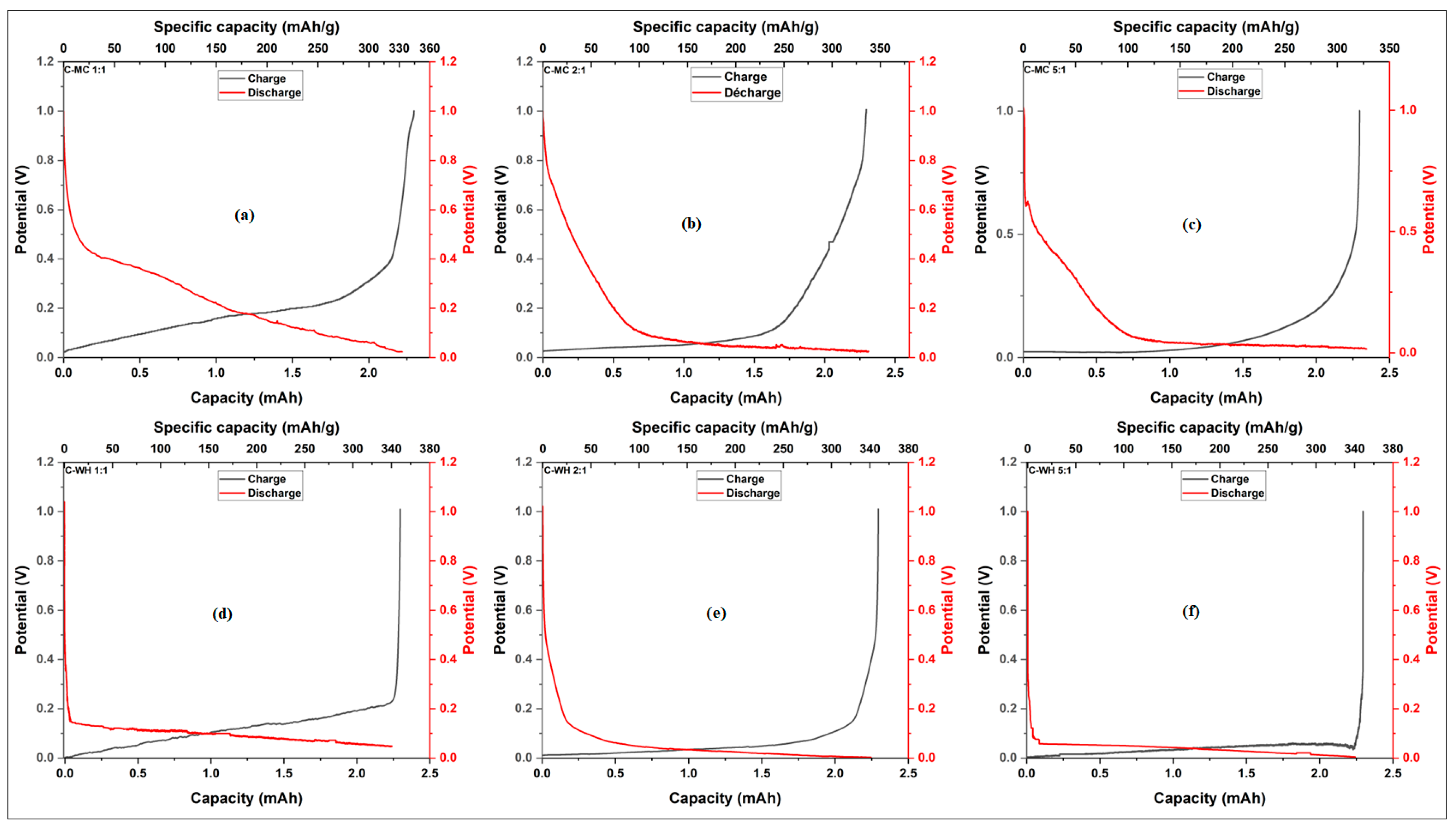

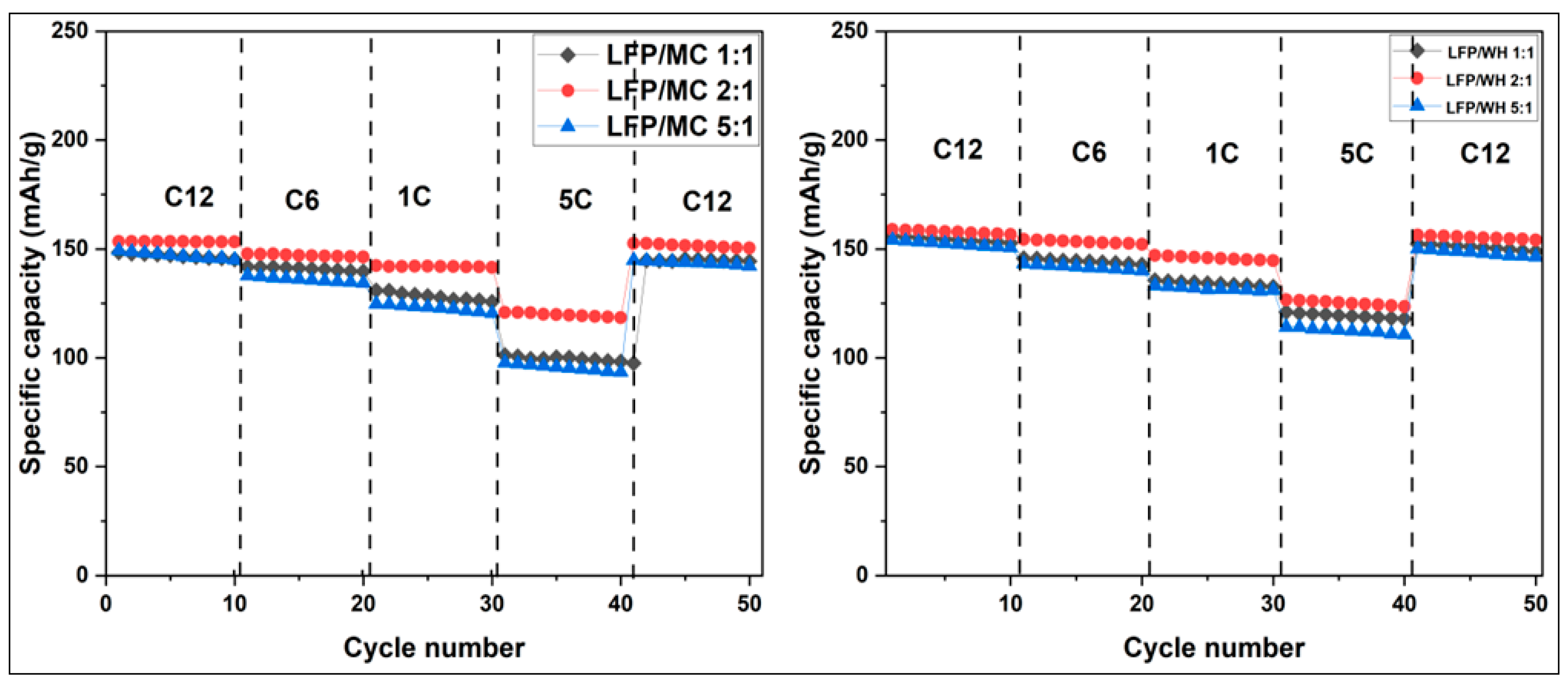

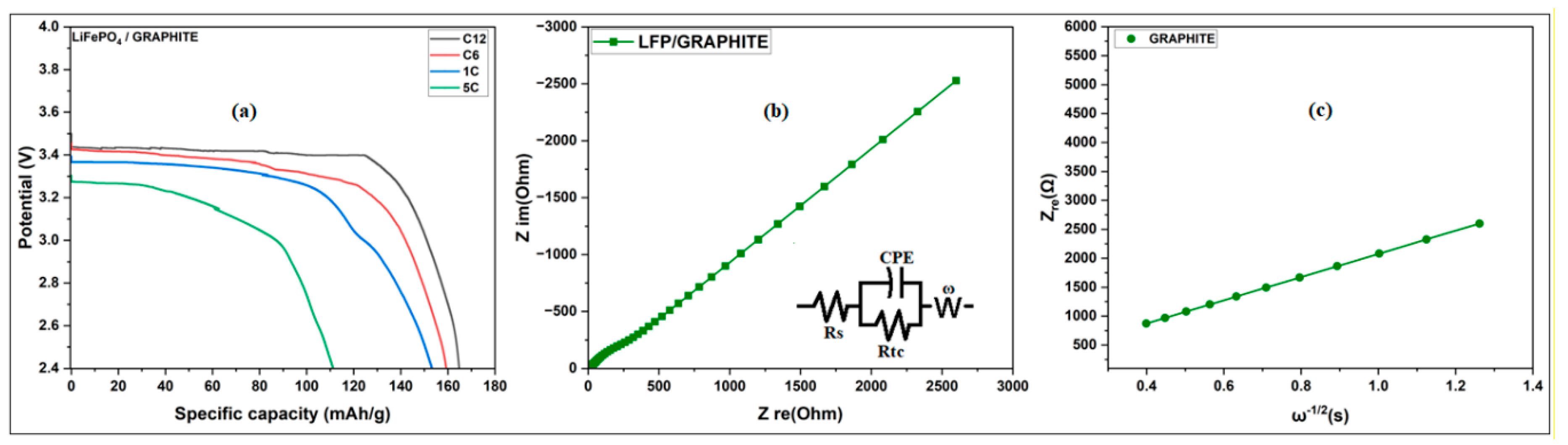

3.3.3.2. Study of the Discharge of LiFePO4/C at Different Current Rates

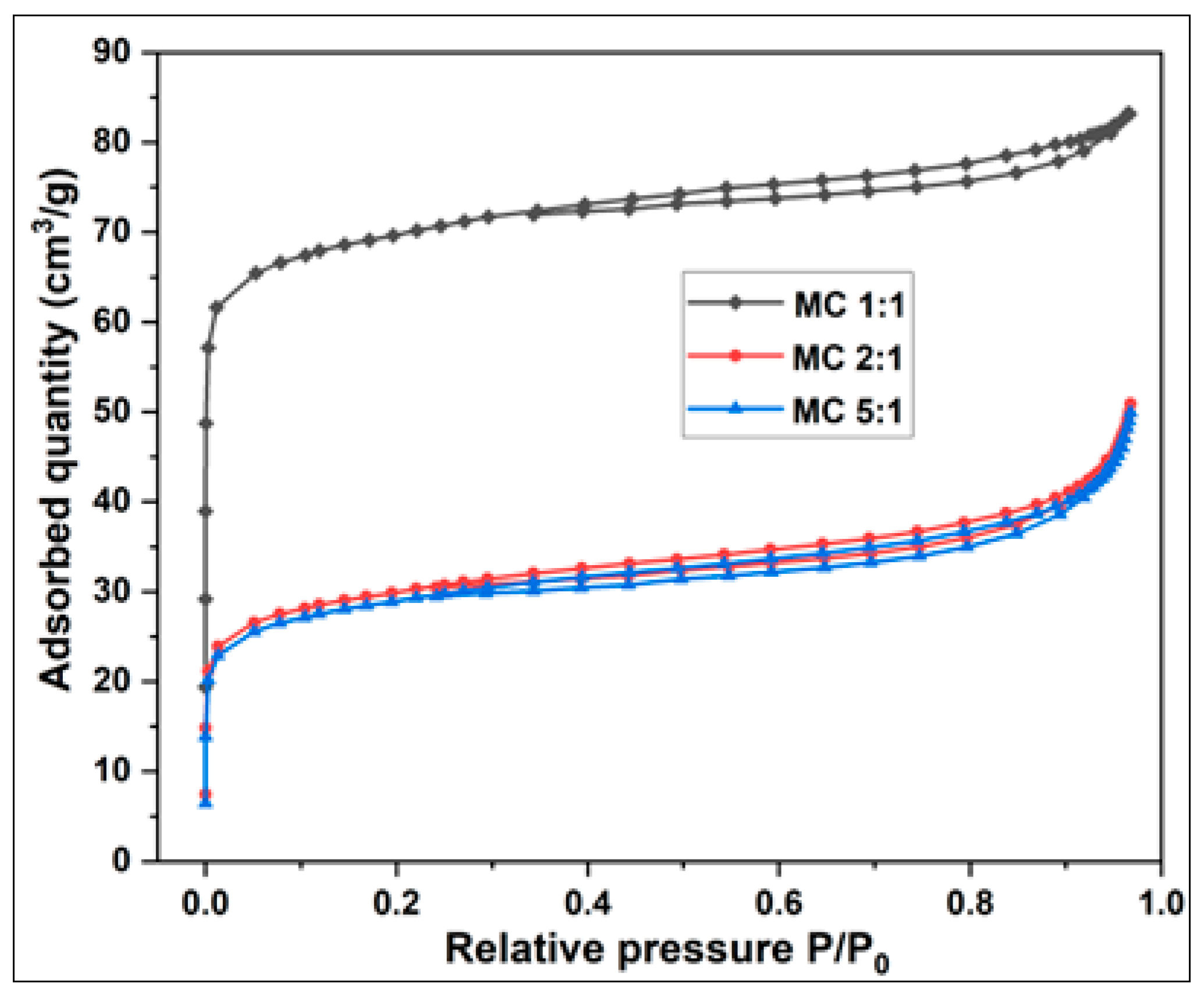

The charge and discharge performance of LiFePO

4 cathodes supported by activated carbon derived from millet cob and water hyacinth was analyzed using coin cells, composed of LiFePO

4/C cathodes and lithium metal anodes. These cells were tested at various current rates, including C12, C6, 1C, and 5C, to evaluate their electrochemical behavior under different conditions. The resulting discharge curves, presented in the corresponding figures, highlight the efficiency and reversible capacity of the cathodes as a function of cycling rate.

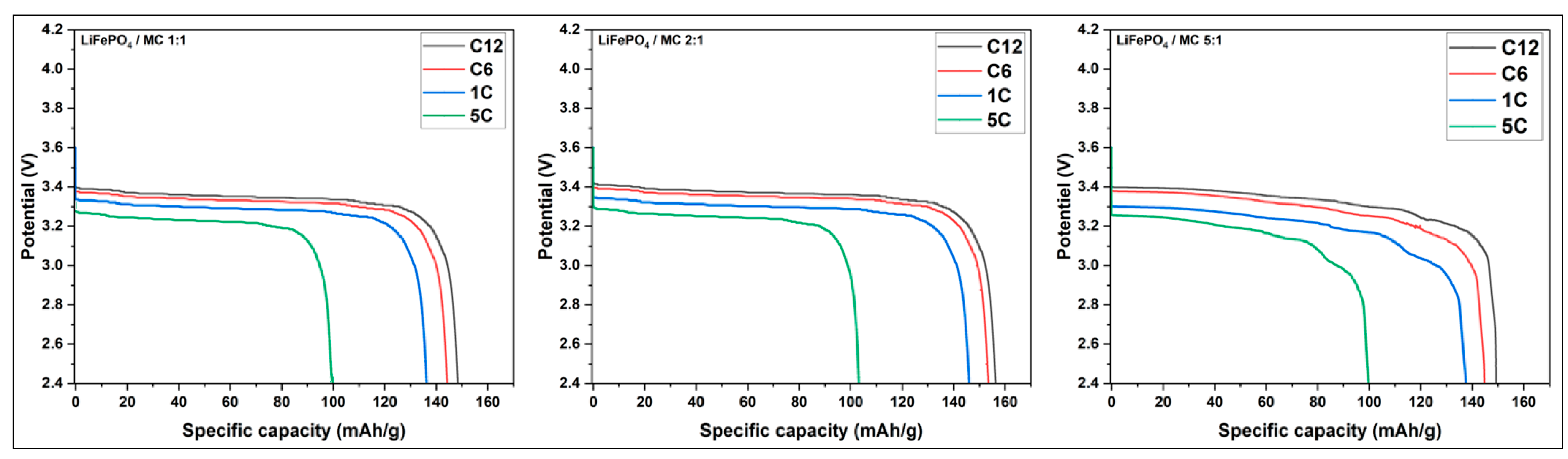

Figure 19 presents the discharge curves of LiFePO

4/C cathodes using activated carbon derived from millet cob, prepared with KOH/MC mass ratios of 1:1, 2:1, and 5:1. These curves exhibit a stable voltage plateau at approximately 3.4 V, corresponding to the redox reactions of the Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ couple, which involve a biphasic mechanism between FePO

4 and LiFePO

4 [

67].

Table 8 shows the variation of the specific capacity with the current rate for different activated carbon based on Millet.

The results indicate that the activated carbon derived from millet cob with a mass ratio of KOH/MC 2:1 exhibits the highest specific capacity and electrical conductivity, outperforming the KOH/MC 1:1 and KOH/MC 5:1 sample. This trend highlights the critical role of the KOH ratio during activation, directly influencing the electrochemical and conductive properties of the material.

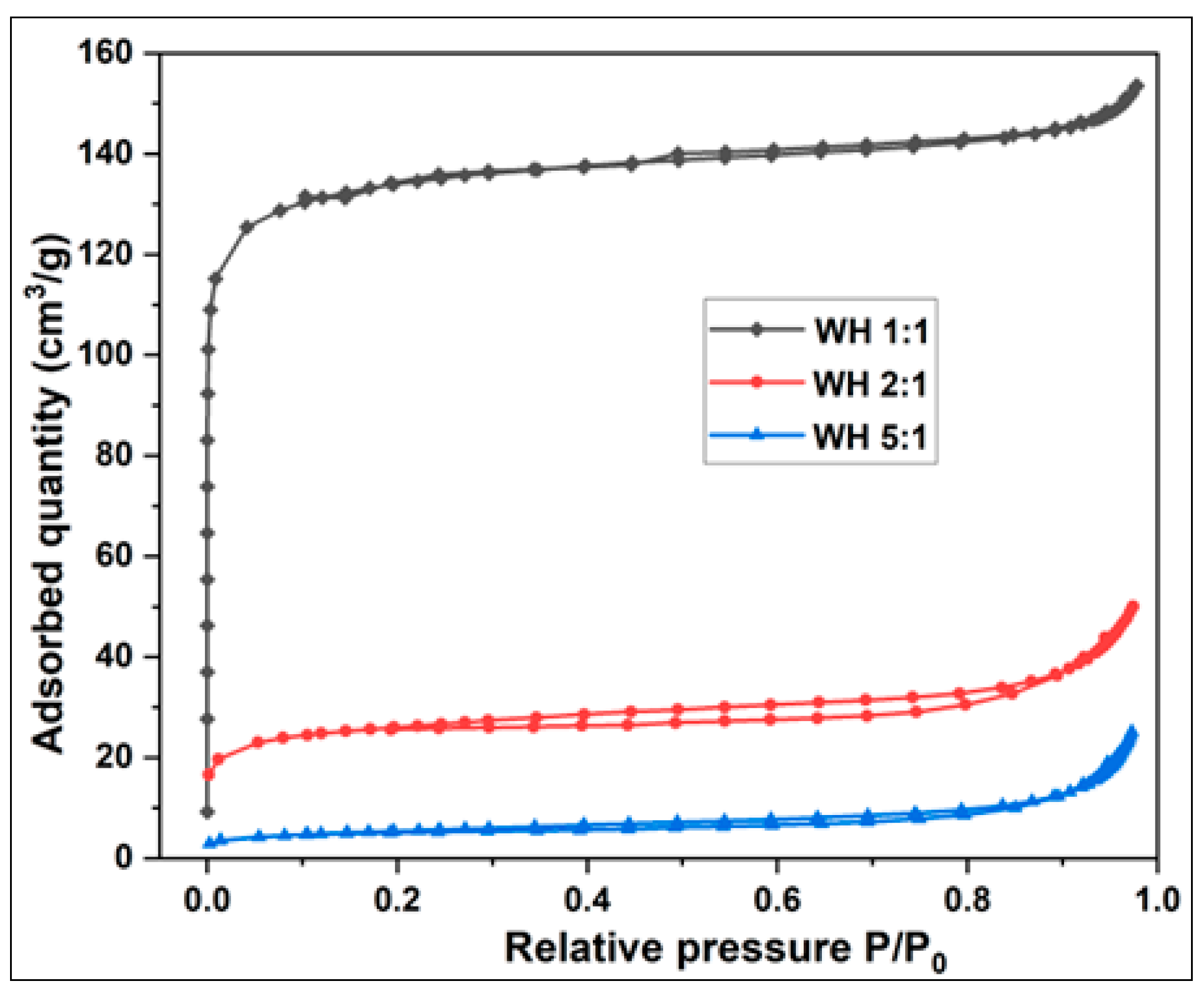

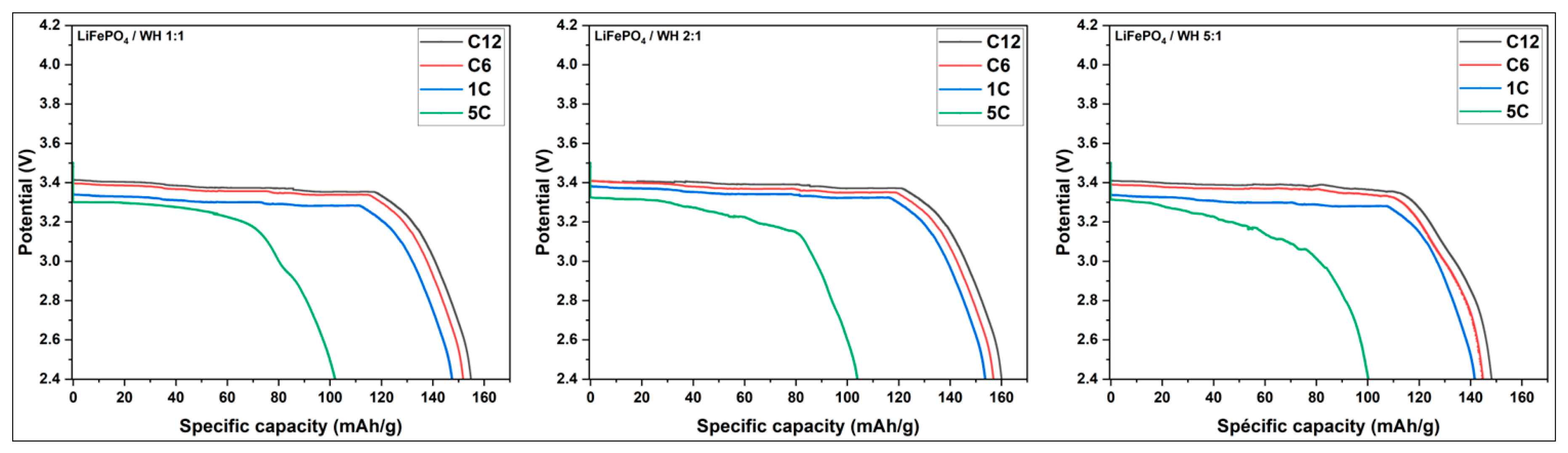

The discharge curves in

Figure 20 illustrate the electrochemical performance of LiFePO4/C cathodes utilizing activated carbon derived from water hyacinth for the KOH/WH 1:1, KOH/WH 2:1, and KOH/WH 5:1 sample. These curves display a stable voltage plateau around 3.4 V, reflecting the reversible redox mechanism of the Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ couple between FePO

4 and LiFePO

4, like the behavior observed with carbon derived from millet cob.

The specific capacities of the LFP/WH 1:1, LFP/WH 2:1, and LFP/WH 5:1 sample, measured at different current rates, reveal optimal performance for the WH 2:1 sample, which exhibits the highest specific capacity. This superiority is attributed to its enhanced electrical conductivity and favorable porous structure, which facilitate lithium-ion diffusion and improve charge transfer.

Table 8.

Specific capacities (SC) of LiFePO4/C samples derived from water hyacinth.

Table 8.

Specific capacities (SC) of LiFePO4/C samples derived from water hyacinth.

| Current rate |

SC (mAh/g) WE 1:1 |

SC (mAh/g) WE 2:1 |

SC (mAh/g) WE 5:1 |

SC(mAh/g) |

| C12 |

158 |

163 |

153 |

167 |

| C6 |

155 |

160 |

149 |

163 |

| 1C |

151 |

157 |

145 |

161 |

| 5C |

108 |

110 |

106 |

120 |

These results confirm the preliminary electrical conductivity tests, which had already highlighted the superiority of the activated carbon with a KOH/WH ratio of 2:1. With its high conductivity and optimized porous structure, this sample demonstrates outstanding performance, particularly at high current rates where ion transport becomes more challenging. It stands out for its ability to maintain high efficiency even under fast charge and discharge conditions.

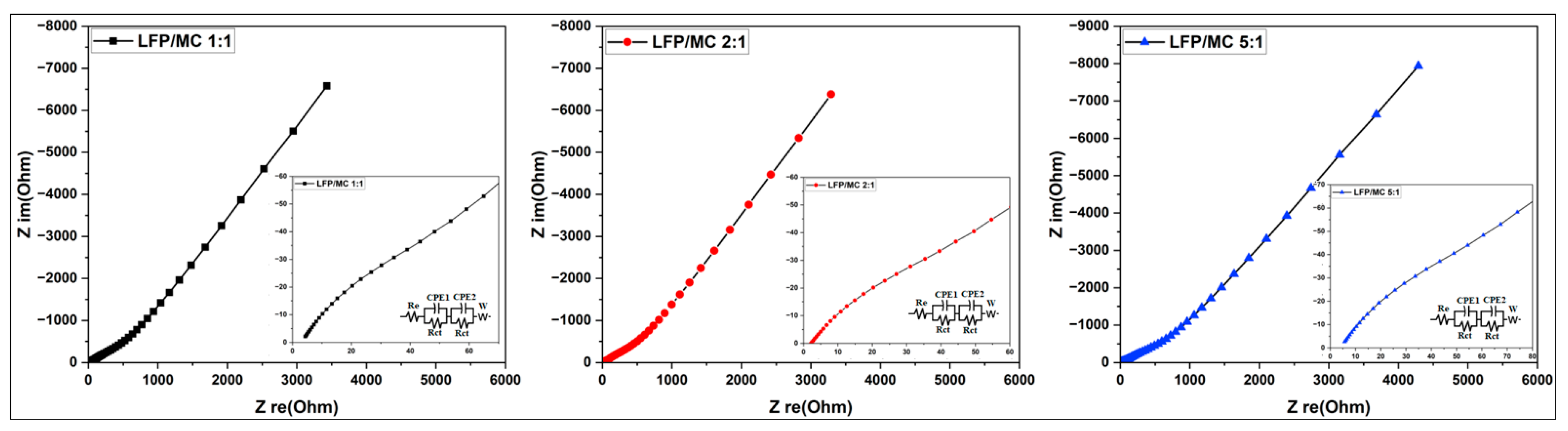

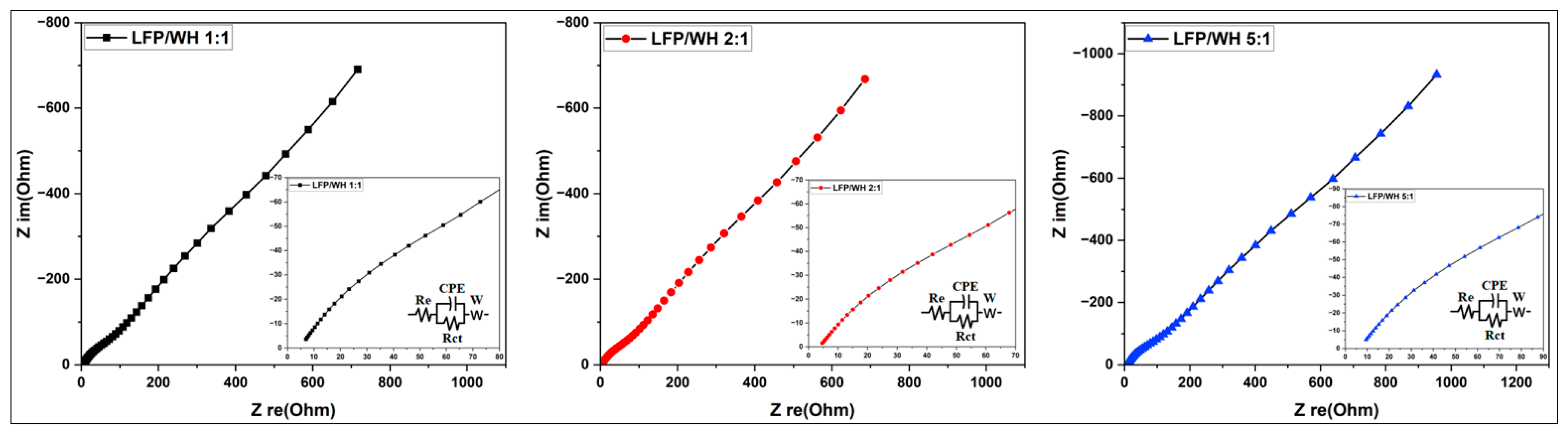

3.3.3.4. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) Analysis

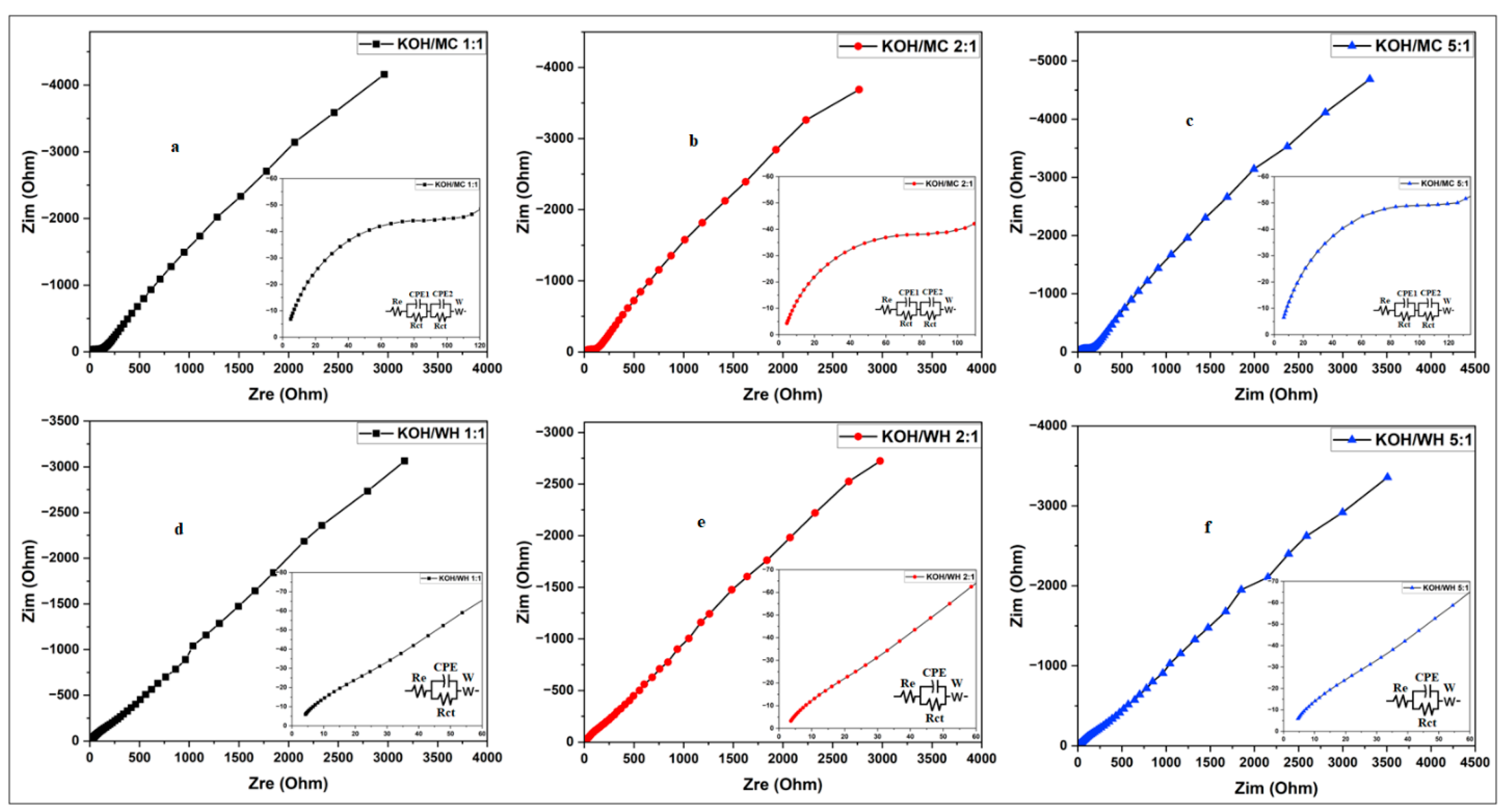

The EIS analysis of LiFePO

4 samples supported by carbon derived from millet cob (MC) and water hyacinth (WH) is illustrated through Nyquist plots, which depict the relationship between the real (Zre) and imaginary (Zim) components of impedance. These curves provide insights into charge transfer resistance (Rct) and lithium-ion diffusion properties. The three spectra of each of the LFP/MC and LFP/WH cathode samples show a similar trend with an absence of a well-defined semicircular loop, followed by an inclined straight line (Warburg), which reflects Li⁺ ion diffusion within the active material, a characteristic behavior of lithium battery electrodes [

68].

Among the carbon-supported LiFePO4 samples derived from millet cob (LFP/MC), the sample prepared with a mass ratio KOH/MC 2:1 shows the smallest values of electrolyte resistance and charge transfer resistance. This suggests improved electronic conductivity, allowing more efficient transport of lithium ions. Conversely, the KOH/MC 5:1 sample exhibits the higher charge transfer resistance, while the KOH/MC 1:1 sample performs intermediately between these two extremes.

Figure 22 depicts the Nyquist plot along with the equivalent circuits of the LiFePO4/C cathode (millet stem carbon), labeled as LFP/MC 1:1, LFP/MC 5:1, and LFP/MC 5:1.

Among the carbon-supported LiFePO4/C samples derived from water hyacinth (LFP/WH), electrochemical testing reveals that the sample prepared with a mass ratio of KOH/WH 2:1 displays the smallest values of resistance. This indicates too enhanced electronic conductivity and more efficient lithium-ion transport. As with the millet cob samples, the water hyacinth sample KOH/WH 5:1 exhibits increased charge transfer resistance, while the KOH/WH 1:1 sample demonstrates performance that falls between these two extremes.

Figure 23 also presents the Nyquist plot for the LFP samples using water hyacinth-derived activated carbon as a support.

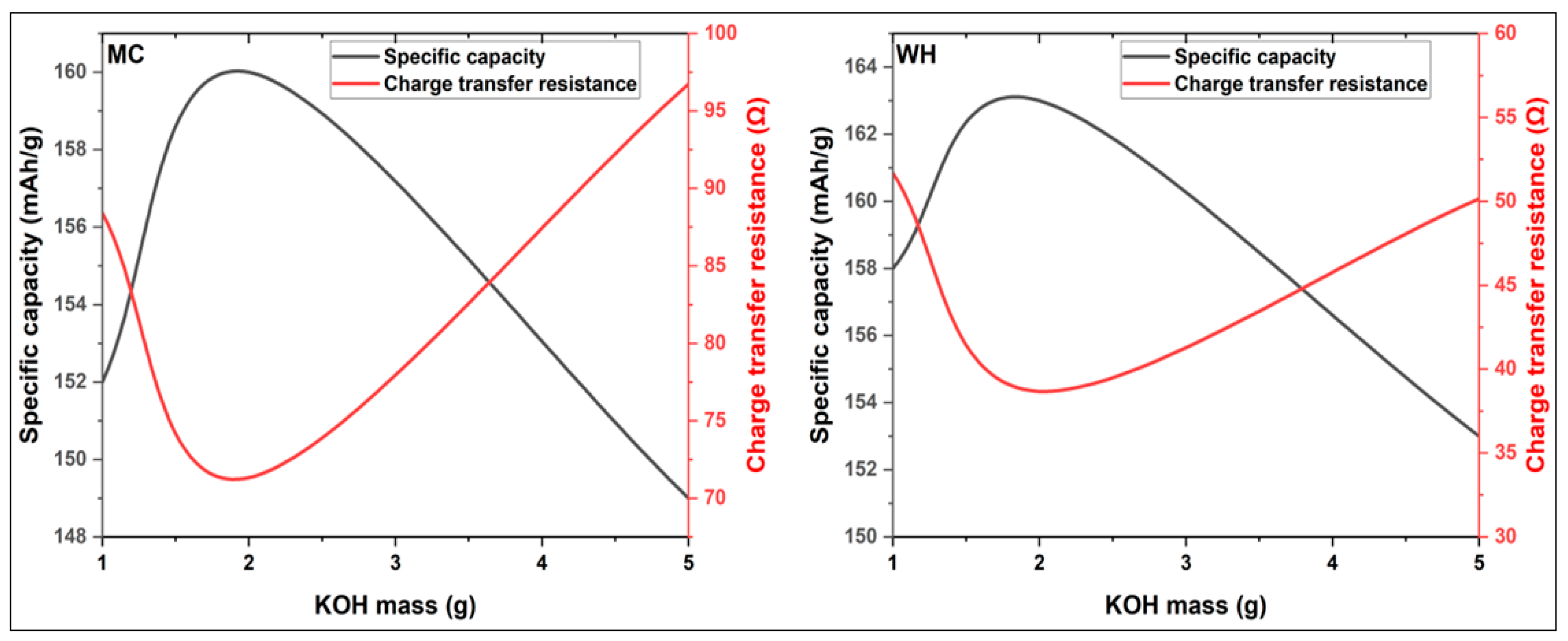

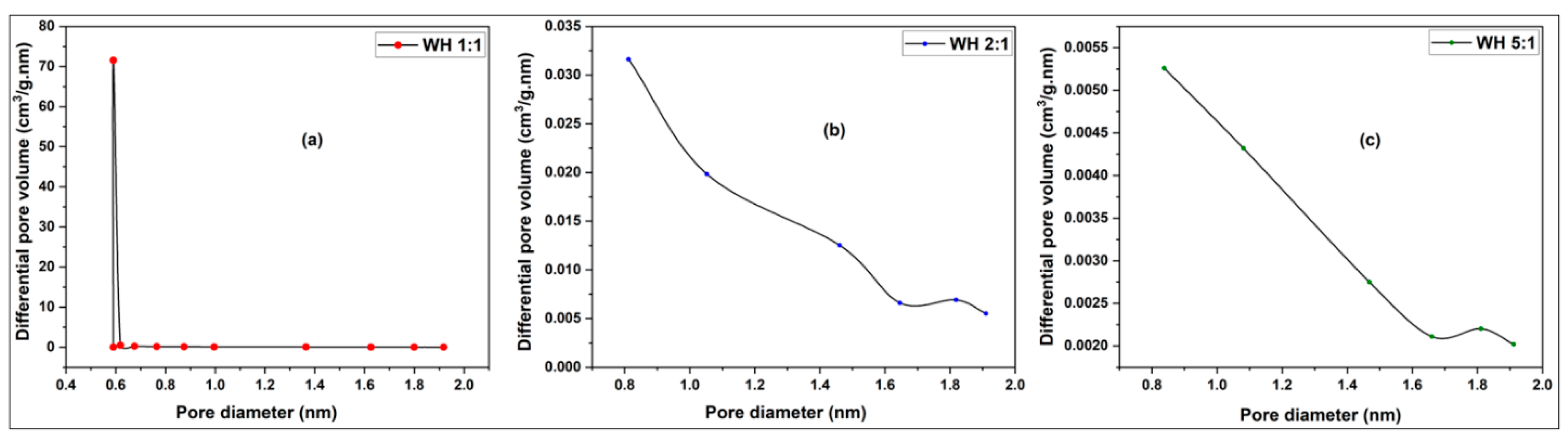

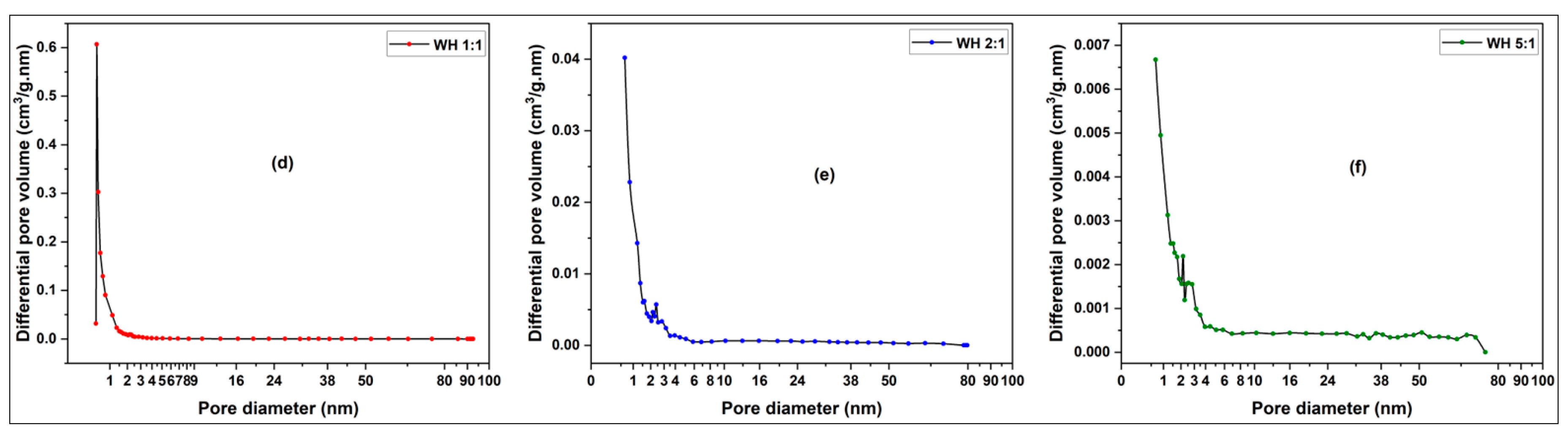

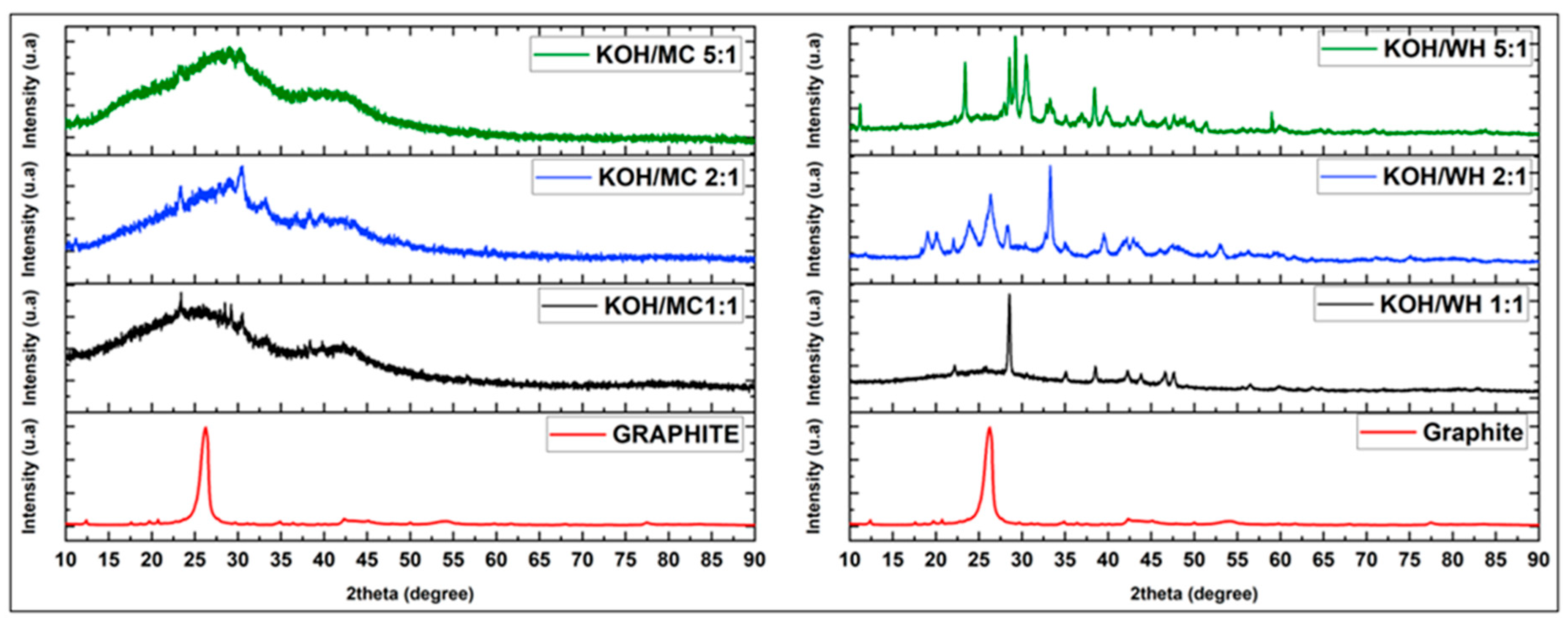

The analysis of the influence of the KOH/Carbonous Materials mass ratio reveals that a ratio KOH/CM 2:1 represents the optimal compromise for electronic conductivity and lithium-ion mobility. An excess of KOH (KOH/CM 5:1 ratio) induces marked degradation of electrochemical properties, likely due to excessive structural alteration of the carbonaceous material. This morphological modification results in reduced interparticle connectivity and a significant increase in charge transfer resistance (Rct). Conversely, a ratio KOH/CM 1:1 generates pronounced microporosity, which hinders charge carrier mobility during charge-discharge cycles.

Comparative characterization of the LFP/WH and LFP/MC cathodes highlights the lower intrinsic impedance of the water hyacinth-based composite. This improvement in conductive properties over millet cob-derived carbon may arise from the distinct crystalline structure of the activated material. The carbon matrix derived from water hyacinth appears to enhance both the dispersion of LiFePO4 particles and the optimization of electron conduction pathways.

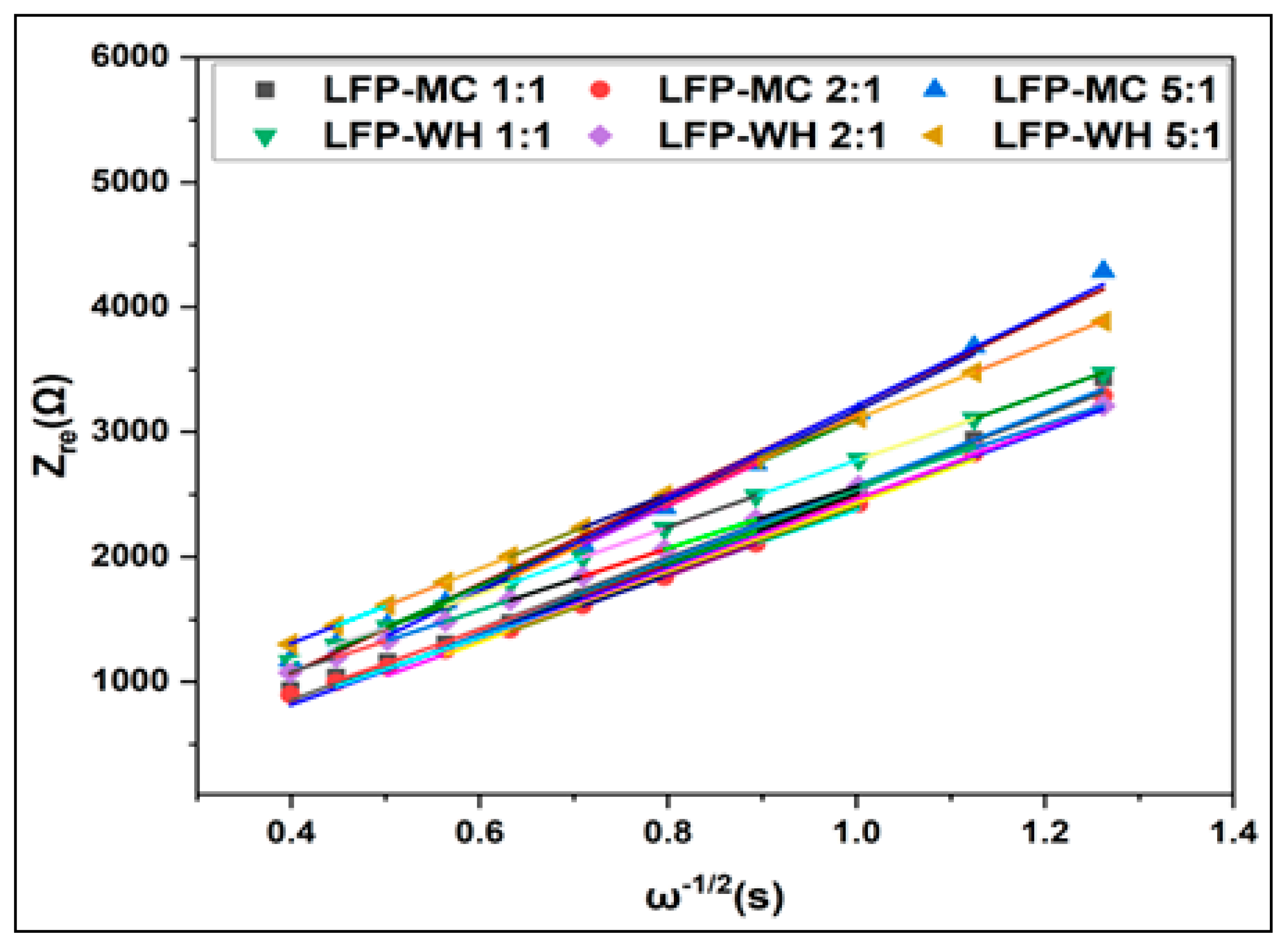

Analysis of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) spectra via equivalent circuit modeling enables extraction of the Warburg coefficient using Equation (3) [

69]. This approach clearly underscores differences in ionic diffusion kinetics between the two cathodic systems supported by millet cob and water hyacinth carbon samples. Equation (3) is given by [

69]:

Where: Zre is the real impedance, Re is the electrolyte resistance, Rct is the charge transfer resistance, ω is the angular frequency in the low-frequency range, and σω represents the slope of Zre curve as a function of ω-1/2.

To determine the slope of the Z

re (ω

-1/2) σ

ω in Equation (1), we employed a systematic approach by plotting the linear relationship between the real impedance component (Z

re) and the inverse square root of low-frequency angular frequencies (ω) for the LFP/EM and LFP/JE composites. This linear regression analysis provides a quantitative assessment of the materials’ electrochemical behavior, particularly their ionic diffusion dynamics. The resulting fitting lines, displayed in

Figure 24, reveal distinct trends for each cathode system, highlighting the superior Warburg-type diffusion characteristics of the water hyacinth-derived carbon (LFP/WH) compared to the millet cob-based counterpart (LFP/MC).

Building on the linear correlations demonstrated in

Figure 24, the lithium-ion diffusion coefficients (D

Li) for the LFP/MC (millet cob-derived carbon) and LFP/WH (water hyacinth-derived carbon) composites were calculated using Equation (4) given by [

69]:

Where: R = universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹), T = absolute temperature (298.5 K), A = electrode surface area (experimental parameter, m²), C is the molar concentration of lithium ions (mol·m⁻³), F = Faraday constant (96,500 C·mol⁻¹).

This methodology enables a rigorous evaluation of ionic mobility within the cathode materials, directly linking structural properties to electrochemical kinetic performance. The derived DLi values underscore the superior ion transport efficiency of the water hyacinth-based composite, consistent with its enhanced charge transfer dynamics observed in earlier analyses.

The key electrochemical parameters derived from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis, including ohmic resistance R

e, charge transfer resistance R

ct, and lithium-ion diffusion coefficient D

Li, are systematically compared for the LFP/MC and LFP/WH cathodes in

Table 6. This quantitative comparison provides essential insights into the interfacial kinetics and ionic transport efficiency of the two composite systems, corroborating their distinct electrochemical behaviors observed in earlier performance evaluations.

Table 9.

EIS-derived electrochemical parameters for LFP/EM and LFP/JE cathodes.

Table 9.

EIS-derived electrochemical parameters for LFP/EM and LFP/JE cathodes.

| Samples |

Re (Ω) |

Rct (Ω) |

DLi (cm²/s) |

| LFP/MC 1:1 |

4.39 |

99.91 |

1.69x10-13 |

| LFP/ MC 2:1 |

2.74 |

95.87 |

1.84x10-13 |

| LFP/ MC 5:1 |

5.72 |

124.88 |

1.07x10-13 |

| LFP/WH 1:1 |

2.70 |

98.6 |

1.94x10-13 |

| LFP/ WH 2:1 |

2.49 |

91.12 |

2.28x10-13 |

| LFP/ WH 5:1 |

3.02 |

110.38 |

1.53x10-13 |

| LFP/graphite |

2.34 |

73.81 |

3.55x10-13 |

Comparative analysis reveals that the LFP/WH 2:1 composite exhibits the lowest ohmic resistance (Re = 2.49 Ω) and charge transfer resistance (Rct = 91.12 Ω) among all tested samples. This synergistic enhancement correlates with a superior lithium-ion diffusion coefficient (DLi = 2.28 × 10⁻¹³ cm² s⁻¹), surpassing values observed in other formulations. The marked improvement in ionic transport kinetics is attributed to the optimized carbon architecture of the LFP/WH 2:1 composite, which reduces effective ion diffusion pathways through hierarchical porosity, thereby enhancing ionic mobility. In contrast, the LFP/MC 5:1 sample (both MC- and WH-derived) display the lowest DLi values, a limitation likely arising from insufficient microporosity and the predominance of non-interconnected macropores, which impede efficient lithium-ion percolation.

The graphite used as a reference here, underwent electrochemical testing under the same conditions. The results indicate superior performance compared to the various synthesized activated carbons. However, the KOH/WH 2:1 sample exhibit performance close to that of graphite.

From the discharge curves, the LFP/Graphite cathode exhibits slightly higher specific capacities at different current rates compared to the LFP/WH 2:1 sample. The LFP/Graphite delivered capacities of 167 mAh/g at C12, 163 mAh/g at C6, 161 mAh/g at 1C, and 120 mAh/g at 5C. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) parameters of the LFP/Graphite cathode are recorded in the table below. The graphite exhibits lower electrolyte resistance and charge transfer resistance compared to the other synthesized activated carbons. Consequently, the LFP/Graphite cathode demonstrates a high diffusion coefficient, followed by the LFP/WH 2:1 cathode.