Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical and Computational Modelling

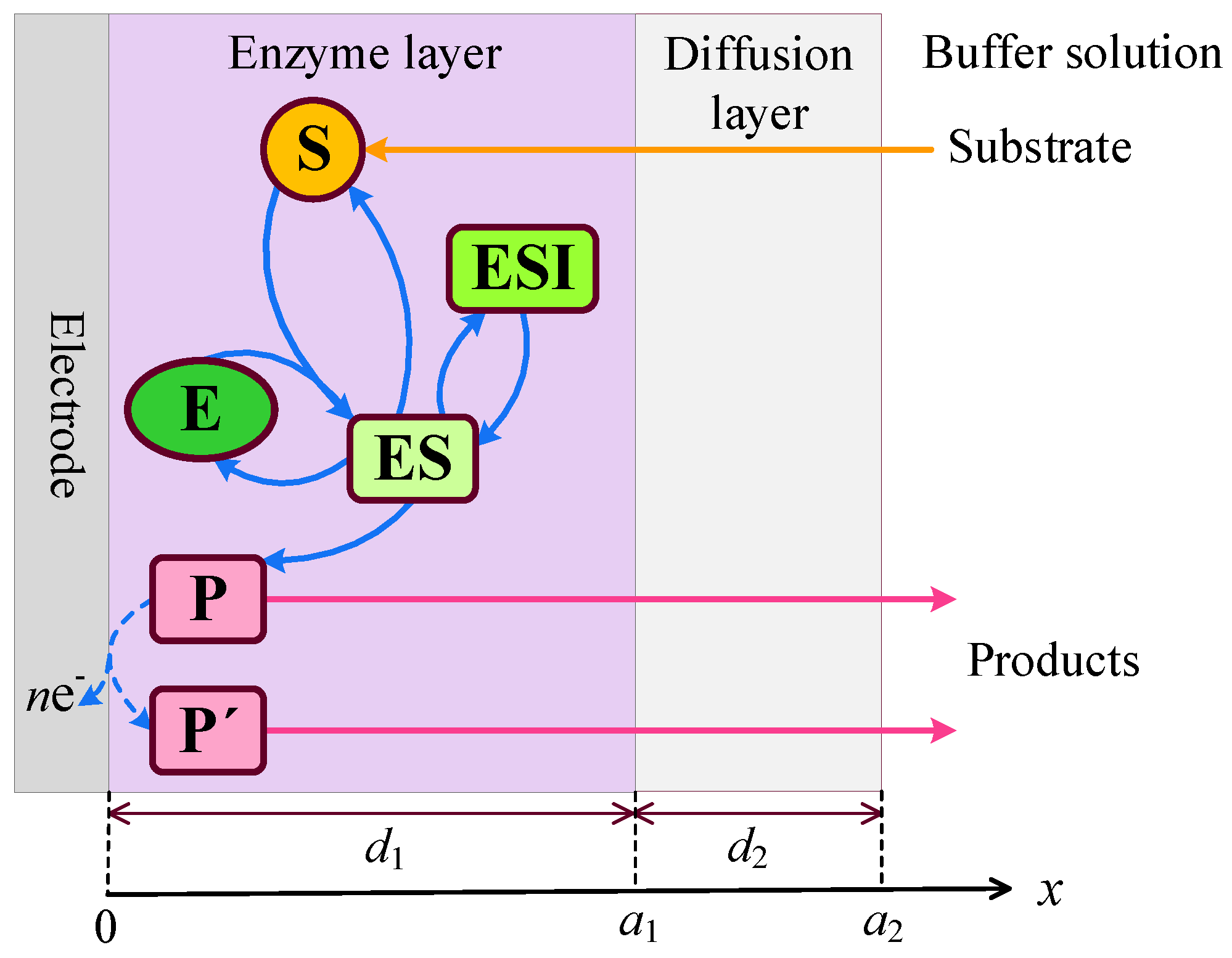

2.1. Biosensor Principal Structure

2.2. Mathematical Model

2.2.1. Governing Equations

2.2.2. Boundary Conditions

2.2.3. Initial Conditions

2.3. Biosensor Response

2.4. Dimensionless Model Parameters

2.5. Numerical Simulation

3. Results and Discusion

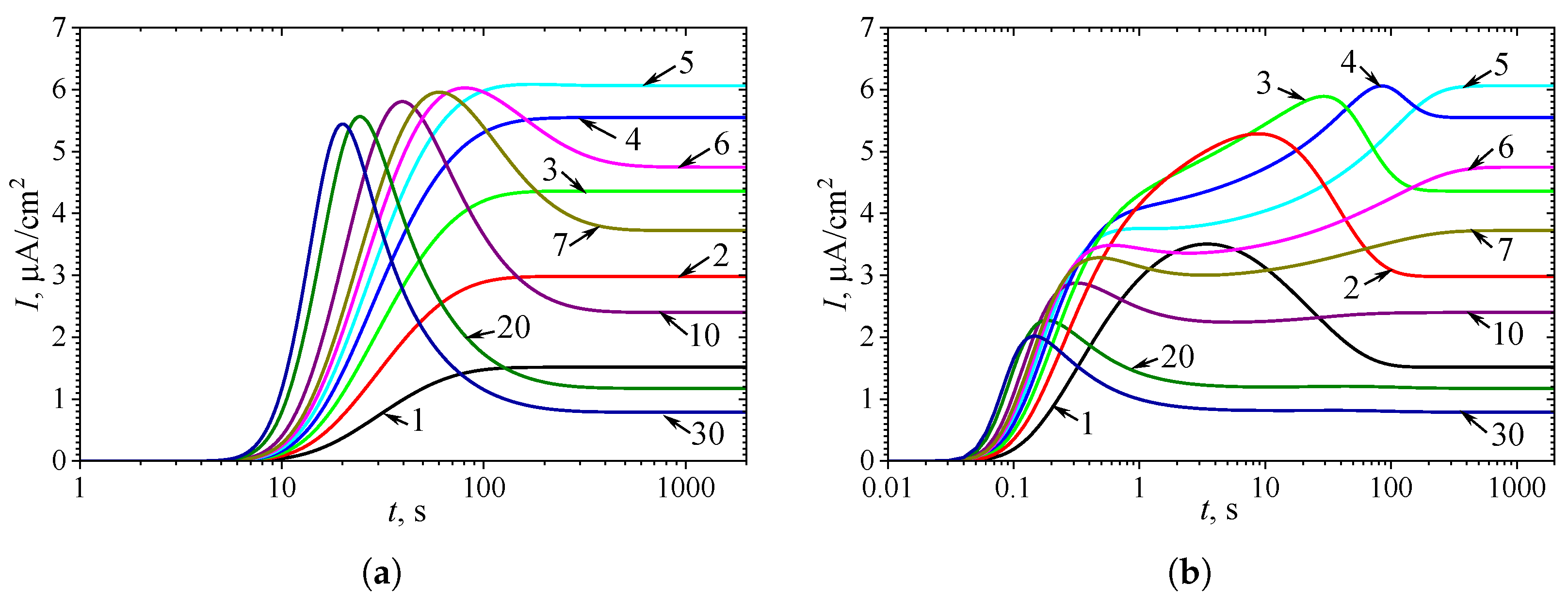

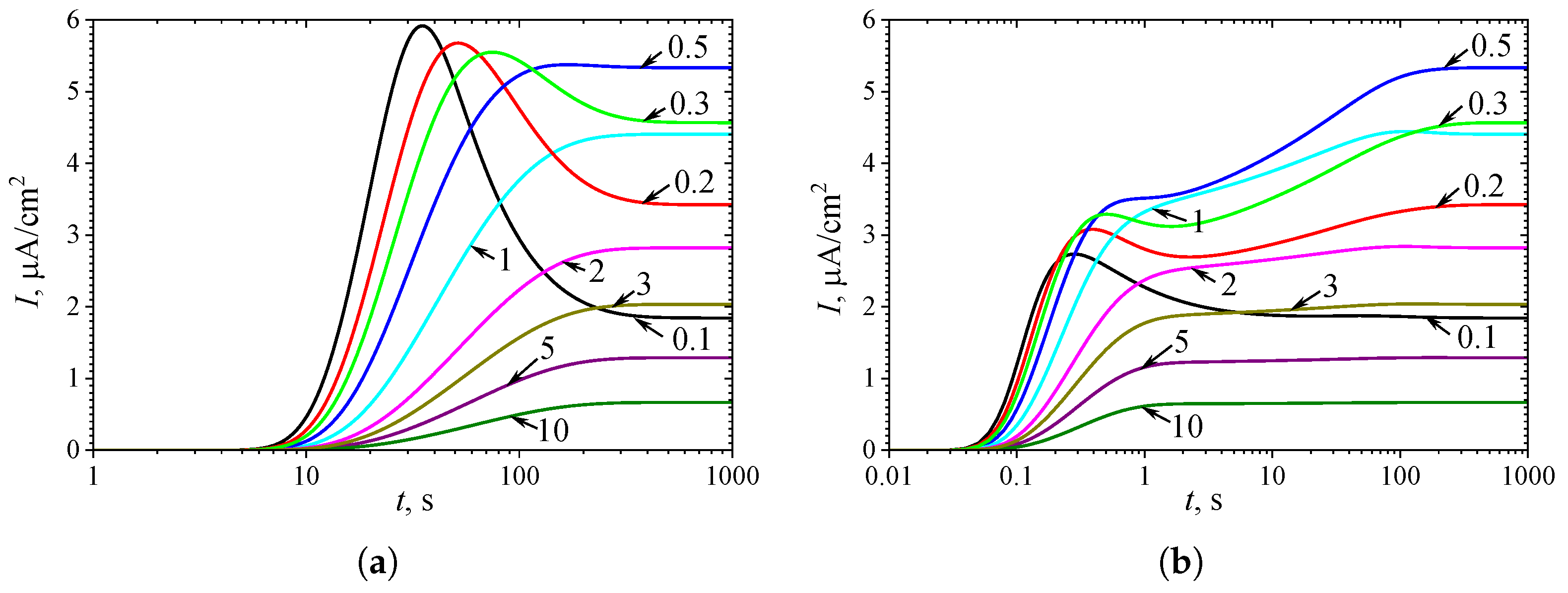

3.1. Temporal Dynamics of Biosensor Response

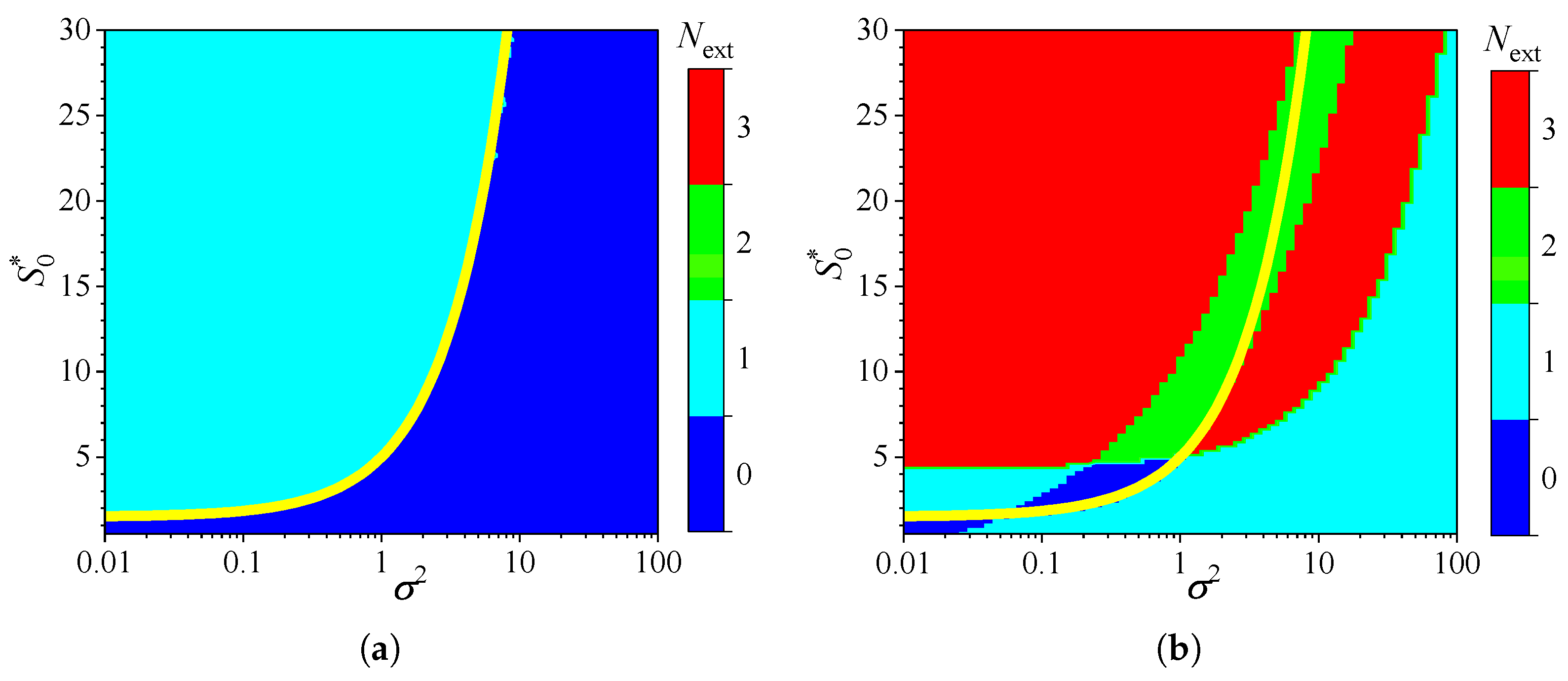

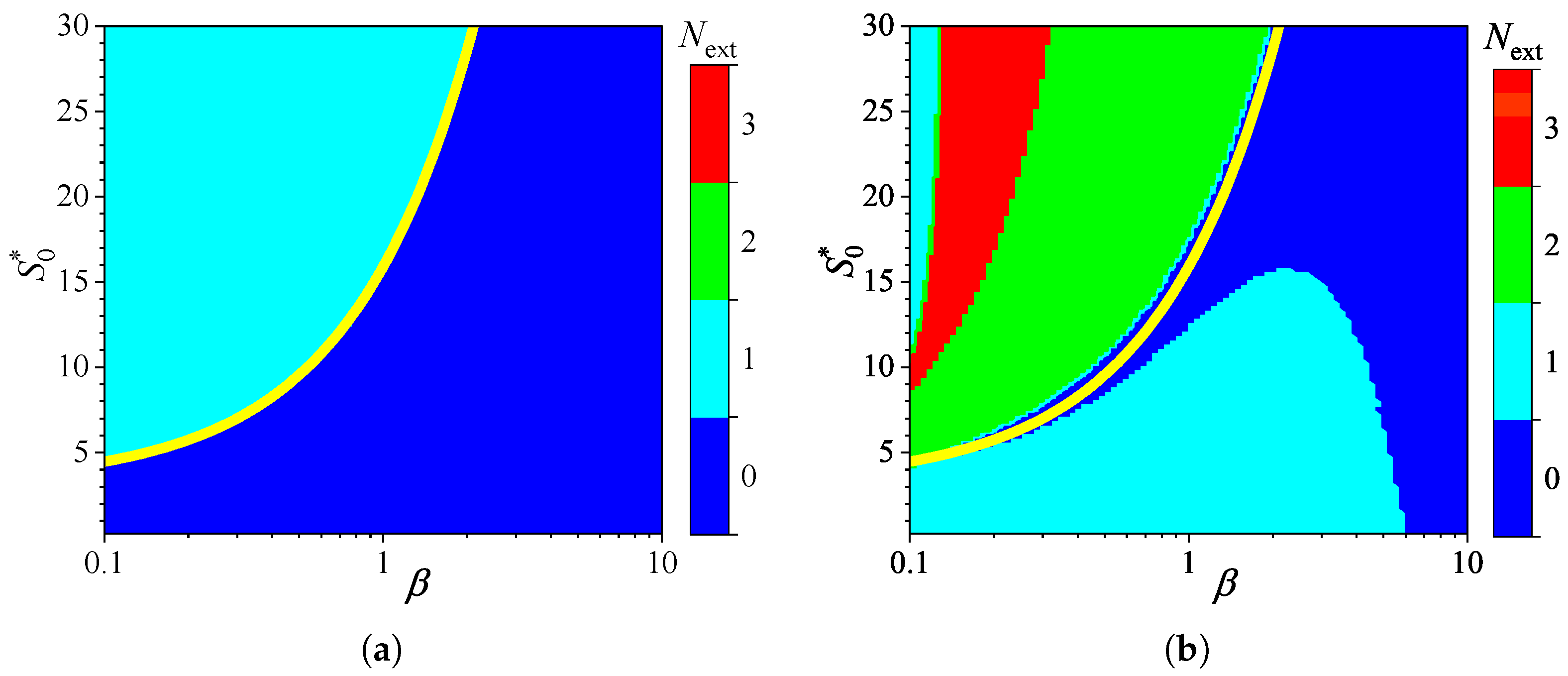

3.2. Effect of Internal Diffusion Limitation

3.3. Effect of External Diffusion Limitation

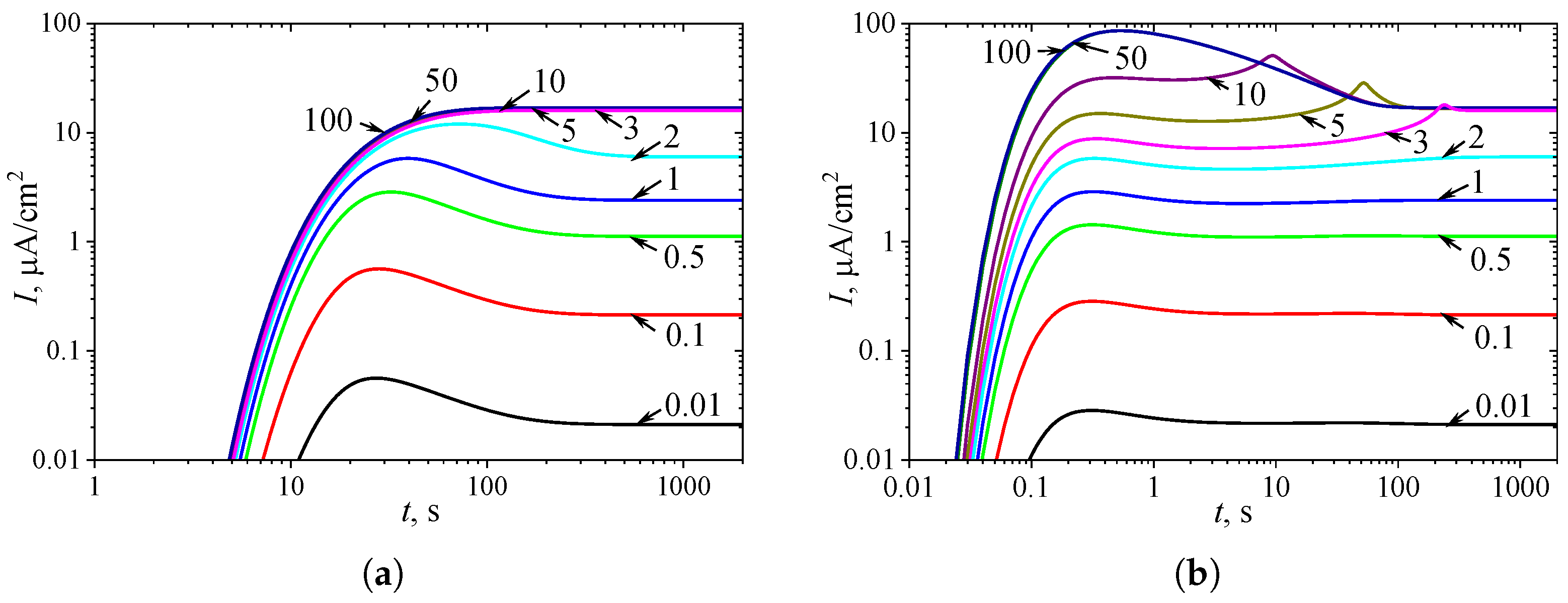

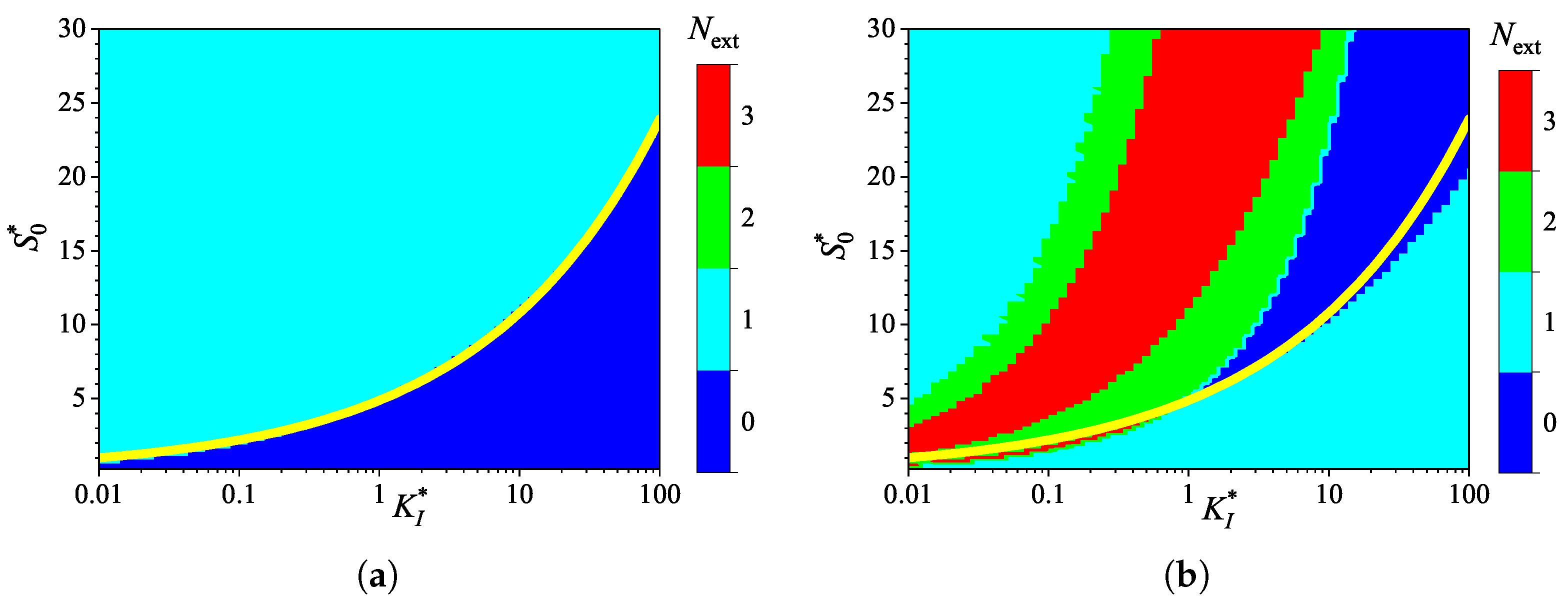

3.4. Effect of Inhibition

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| E | Enzyme |

| S | Substrate |

| P | Reaction product |

| ES | Enzyme-substrate complex |

| ESI | Inhibitory complex |

| IA | Injection analysis |

| BA | Batch analysis |

| QSSA | Quasi-steady-state approximation |

Appendix A. Dimensionless Mathematical Model

| Parameter | Dimensional | Dimensionless |

|---|---|---|

| Time | t, s | |

| Distance from electrode | ||

| Enzyme layer thickness | ||

| Diffusion layer thickness | ||

| Substrate concentration in enzyme layer | ||

| Product concentration in enzyme layer | ||

| Substrate concentration in diffusion layer | ||

| Product concentration in diffusion layer | ||

| Substrate concentration in bulk | ||

| Michaelis-Menten constant | ||

| Substrate inhibition constant | ||

| Maximal enzymatic rate | ||

| Current density | ||

| Steady-state current density | ||

| Diffusion coefficient of substrate in enzyme layer | ||

| Diffusion coefficient of product in enzyme layer | ||

| Diffusion coefficient of substrate in diffusion layer | ||

| Diffusion coefficient of product in diffusion layer | ||

| Partition coefficient for substrate | ||

| Partition coefficient for product | ||

| Biot number for substrate | ||

| Biot number for product | ||

| Diffusion module | ||

| External diffusion module |

References

- Bisswanger, H. Enzyme Kinetics: Principles and Methods, 2 ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Weinheim, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, B.D.; Pandey, C.M. Biosensors: Fundamentals and Applications; Smithers Rapra: Shawbury, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Patra, S.; Kundu, D.; Gogoi, M. (Eds.) Enzyme-based Biosensors: Recent Advances and Applications in Healthcare; Springer Verlag: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Scheller, F.W.; Schubert, F. Biosensors; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sadana, A.; Sadana, N. Handbook of Biosensors and Biosensor Kinetics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish-Bowden, A. Fundamentals of Enzyme Kinetics, 3 ed.; Portland Press: London, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, A.P.F.; Karube, I.; Wilson, G.S. (Eds.) Biosensors: Fundamentals and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, P.N. Bioelectrochemistry: Fundamentals, Experimental Techniques and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Banica, F.G. Chemical Sensors and Biosensors: Fundamentals and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rafat, N.; Satoh, P.; Worden, R.M. Electrochemical Biosensor for Markers of Neurological Esterase Inhibition. Biosensors-Basel 2021, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullo, L.; Brunelleschi, B.; Duranti, L.; Fiore, L.; Mazzaracchio, V.; Arduini, F. 3D printed shamrock-like electrochemical biosensing tool based on enzymatic inhibition for on-line nerve agent measurement in drinking water. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 282, 117471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M.; Webb, E.; Thorne, C.; Tipton, K. Enzymes, 3 ed.; Longman: London, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Croce, R.A.J.; Vaddiraju, S.; Papadimitrakopoulos, F.; Jain, F.C. Theoretical analysis of the performance of glucose sensors with layer-by-layer assembled outer membranes. Sensors 2012, 12, 13402–13416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, O.; Bercovici, M. Simulation tool coupling nonlinear electrophoresis and reaction kinetics for design and optimization of biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baronas, R.; Kulys, J.; Lančinskas, A.; Žilinskas, A. Effect of diffusion limitations on multianalyte determination from biased biosensor response. Sensors 2014, 14, 4634–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulys, J. Biosensor response at mixed enzyme kinetics and external diffusion limitation in case of substrate inhibition. Nonlinear Anal. Model. Control. 2006, 11, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirón, J.; González, M.P.; Vázquez, J.A.; Pastrana, L.; Murado, M.A. A mathematical model for glucose oxidase kinetics, including inhibitory, deactivant and diffusional effects, and their interactions. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2004, 34, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaallah, R.; Amine, A. The Kinetic and Analytical Aspects of Enzyme Competitive Inhibition: Sensing of Tyrosinase Inhibitors. Biosensors-Basel 2021, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forastiere, D.; Falasco, G.; Esposito, M. Strong current response to slow modulation: A metabolic case-study. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 134101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshagh, F.; Rostami, K.; van Niel, E.W. Application of kinetic models in dark fermentative hydrogen production – A critical review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 21952–21968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraz, M.; Alvarez-Ramirez, J.; Vernon-Carter, E.J.; Reyes, I.; Hernandez-Jaimes, C.; Martinez-Martinez, F. A Two Competing Substrates Michaelis-Menten Kinetics Scheme for the Analysis of In Vitro Starch Digestograms. Starch-Starke 2020, p. 1900170.

- Meriç, S.; Tünay, O.; San, H.A. A new approach to modelling substrate inhibition. Environ. Technol. 2002, 23, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meriç, S.; Tünay, O.T.; San, H.A. Modelling approaches in substrate inhibition. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 1998, 7, 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, H.; John, R. Development of a quantitative relationship between inhibition percentage and both incubation time and inhibitor concentration for inhibition biosensors-theoretical and practical considerations. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2001, 16, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baronas, R.; Ivanauskas, F.; Kulys, J. Mathematical Modeling of Biosensors; Springer Series on Chemical Sensors and Biosensors; Springer: Cham, 2021; Volume 9, p. 456. [Google Scholar]

- Achi, F.; Bourouina-Bacha, S.; Bourouina, M.; Amine, A. Mathematical model and numerical simulation of inhibition based biosensor for the detection of Hg(II). Sens. Actuator B: Chem. 2015, 207, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernevez, J. Enzyme Mathematics. Studies in Mathematics and its Applications; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Manimozhi, P.; Subbiah, A.; Rajendran, L. Solution of steady-state substrate concentration in the action of biosensor response at mixed enzyme kinetics. Sensor. Actuat. B-Chem. 2010, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.D. Mathematical Biology: I. An Introduction, 3 ed.; Springer: New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kulys, J.; Baronas, R. Modelling of amperometric biosensors in the case of substrate inhibition. Sensors 2006, 6, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimelevičius, D.; Baronas, R. Computational modelling of amperometric biosensors in the case of substrate and product inhibition. J. Math. Chem. 2010, 47, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.C.; Lieb, A.; Nijhout, H.F. The biological significance of substrate inhibition: A mechanism with diverse functions. BioEssays 2010, 32, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanasundaraganesan, M.; Luis, J.; Guirao, G.; Rathinama, S. Theoretical Analysis of Amperometric Biosensor with Substrate and Product Inhibition Involving non-Michaelis-Menten Kinetics. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2025, 93, 319–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulmeister, T. Mathematical modelling of the dynamic behaviour of amperometric enzyme electrodes. Sel. Electrode Rev. 1990, 12, 203–260. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, M.R.; Baruzzi, A.M.; Garay, F. Mathematical modeling and experimental results of a sandwich-type amperometric biosensor. Sensors and Actuators B 2012, 162, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, M.C.; Pirabaharan, P.; Rajendran, L.; Abukhaled, M. Amperometric biosensors in an uncompetitive inhibition processes: a complete theoretical and numerical analysis. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2021, 133, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, R.; Devi, M.C.; Rajendran, L.; Venugopal, K. Sensitivity and resistance of amperometric biosensors in substrate inhibition processes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 895, 115527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayagan, J.A.; Krishnan, S.M.; Rajendran, L.; Eswari, A. Incorporating different enzyme kinetics in amperometric biosensor for the steady-state conditions: A complete theoretical and numerical approach. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2024, 19, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reena, A.; Karpagavalli, S.; Swaminathan, R. Mathematical analysis of urea amperometric biosensor with Non-Competitive inhibition for Non-Linear Reaction-Diffusion equations with Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Results Chem. 2024, 7, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallikarjuna, M.; Senthamarai, R. An amperometric biosensor and its steady state current in the case of substrate and product inhibition: Taylors series method and Adomian decomposition method. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 946, 117699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shannag, M.; Al-Qodah, Z.; Herrero, J.; Humphrey, J.A.; Giralt, F. Using a wall-driven flow to reduce the external mass-transfer resistance of a bio-reaction system. Biochem. Eng. J. 2008, 39, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypacz, P.; Kabduali, B.; Golman, B.; Andreev, V. Dead-core solutions and critical Thiele modulus for slabs with a distributed catalyst and external mass transfer. React. Chem. Eng. 2023, 8, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baronas, R. Nonlinear effects of diffusion limitations on the response and sensitivity of amperometric biosensors. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 240, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Govid, R. New Thiele’s Modulus for the Monod Biofilm Model. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2008, 16, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Barea, A.; Leckner, B. Modeling of biomass gasification in fluidized bed. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 444–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickson, R.I.; Barry, S.I.; Mercer, G.N.; Sidhu, H.S. Finite difference schemes for multilayer diffusion. Math. Comput. Model. 2011, 54, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ašeris, V.; Baronas, R.; Petrauskas, K. Computational modelling of three-layered biosensor based on chemically modified electrode. Comp. Appl. Math. 2016, 35, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baronas, R. Nonlinear effects of partitioning and diffusion-limiting phenomena on the response and sensitivity of three-layer amperometric biosensors. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 478, 143830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaedel, W.J.; Kissel, T.R.; Boguslaski, R.C. Kinetic behavior of enzymes immobilized in artificial membranes. Anal. Chem. 1972, 44, 2030–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochum, P.; Kowalski, B.R. A coupled two-compartment model for immobilized enzyme electrodes. Anal. Chim. Acta 1982, 144, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanauskas, F.; Baronas, R. Modeling an amperometric biosensor acting in a flowing liquid. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Fluids 2008, 56, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.Q.N.; Varnićic, M.; Hanke-Rauschenbach, R.; Vidakovic-Koch, T.; Sundmacher, K. Mathematical modeling of a porous enzymatic electrode with direct electron transfer mechanism. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 137, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafat, N.; Satoh, P.; Worden, R.M. Integrated Experimental and Theoretical Studies on an Electrochemical Immunosensor. Biosensors-Basel 2021, 10, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, J.; Rajendran, L.; Wang, L.; Fernandez, C. A new mathematical modelling using Homotopy perturbation method to solve nonlinear equations in enzymatic glucose fuel cells. Chem. Phys. Let. 2016, 662, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britz, D.; Strutwolf, J. Digital Simulation in Electrochemistry, 4 ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2016; p. 492. [Google Scholar]

- Samarskii, A. The Theory of Difference Schemes; Marcel Dekker: New York-Basel, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena, J. Time-scale separation: Michaelis and Menten’s old idea, still bearing fruit. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Shen, Y.; Li, B. Quasi-steady-state laws in enzyme kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 2311–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutfreund, H. Kinetics for the Life Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M.E.G. Transport and kinetics at carbon nanotube – redox enzyme composite modified electrode biosensors. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2009, 4, 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulmeister, T. Mathematical treatment of concentration profiles and anodic current of amperometric enzyme electrodes with chemically amplified response. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1987, 201, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Analytical Electrochemistry, 3 ed.; Wiley: New-York, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Velkovsky, M.; Snider, R.; Cliffel, D.E.; Wikswo, J.P. Modeling the measurements of cellular fluxes in microbioreactor devices using thin enzyme electrodes. J. Math. Chem. 2011, 49, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobst, G.; Moser, I.; Urban, G. Numerical simulation of multi-layered enzymatic sensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 1996, 11, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coche-Guerente, L.; Labbé, P.; Mengeaud, V. Amplification of amperometric biosensor responses by electrochemical substrate recycling. 3. Theoretical and experimental study of the phenol-polyphenol oxidase system immobilized in laponite hydrogels and layer-by-layer self-assembled structures. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 3206–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevelyan, P.M.J.; Strier, D.E.; Wit, A.D. Analytical asymptotic solutions of nA+mB→C reaction-diffusion equations in two-layer systems: A general study. Phys. Rev. E 2008, 78, 026122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumsey, T.R.; McCarthy, K.L. Modeling oil migration in two-layer chocolate-almond confectionery products. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauverjat, C.; de Loubens, C.; Déléris, I.; Tréléa, I.C.; Souchon, I. Rapid determination of partition and diffusion properties for salt and aroma compounds in complex food matrices. J. Food Eng. 2009, 93, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulys, J. The development of new analytical systems based on biocatalysts. Anal. Lett. 1981, 14, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzicka, J.; Hansen, E. Flow Injection Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Baronas, R.; Ivanauskas, F.; Kulys, J. Modelling dynamics of amperometric biosensors in batch and flow injection analysis. J. Math. Chem. 2002, 32, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M.E.G.; Bannon, T.; Hinds, G.; Rebouillat, S. Reaction/diffusion with Michaelis-Menten kinetics in electroactive polymer films. Part 2. The transient amperometric response. Analyst 1998, 123, 1947–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, D.; Na, T.; Schultz, J.S. Effectiveness factor calculations for immobilized enzyme catalysts. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1973, 15, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baronas, R. Nonlinear effects of partitioning and diffusion limitation on the efficiency of three-layer enzyme bioreactors and potentiometric biosensors. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2024, 974, 118698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britz, D.; Baronas, R.; Gaidamauskaitė, E.; Ivanauskas, F. Further comparisons of finite difference schemes for computational modelling of biosensors. Nonlinear Anal. Model. Control 2009, 14, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.J.; March, N.G. Semi-analytical solution of multilayer diffusion problems with time-varying boundary conditions and general interface conditions. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 333, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, N.G.; Carr, E.J. Finite volume schemes for multilayer diffusion. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2019, 345, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, K. Mathematical simulation of an amperometric enzyme-substrate electrode with a pO2 basic sensor. Part 2. Mathematical simulation of the glucose oxidase glucose electrode. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 1988, 26, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniasz, L.; Britz, D. Recent developments in digital simulation of electroanalytical experiments. Pol. J. Chem. 2004, 78, 1195–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, J.E.; Midkiff, S.P.; Gupta, M.; Artigas, P.V.; Snir, M.; Lawrence, R.D. Java programming for high-performance numerical computing. IBM Syst. J. 2000, 39, 21–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberly, J.; Bernards, M.; Waynant, K. Key features and updates for Origin 2018. J. Cheminform. 2018, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulys, J.; Hansen, H. Carbon-paste biosensors array for long-term glucose measurement. Biosens. Bioelectron. 1994, 9, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.S. Advancing Biosensors with Machine Learning. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 3346–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).