Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extended System

2.2. Selecting Parameters

2.2.1. Orthogonal Algorithm

2.2.2. Optimization of the Identifiable Parameter’s Selection

3. Results

3.1. The Heat Exchanger Model

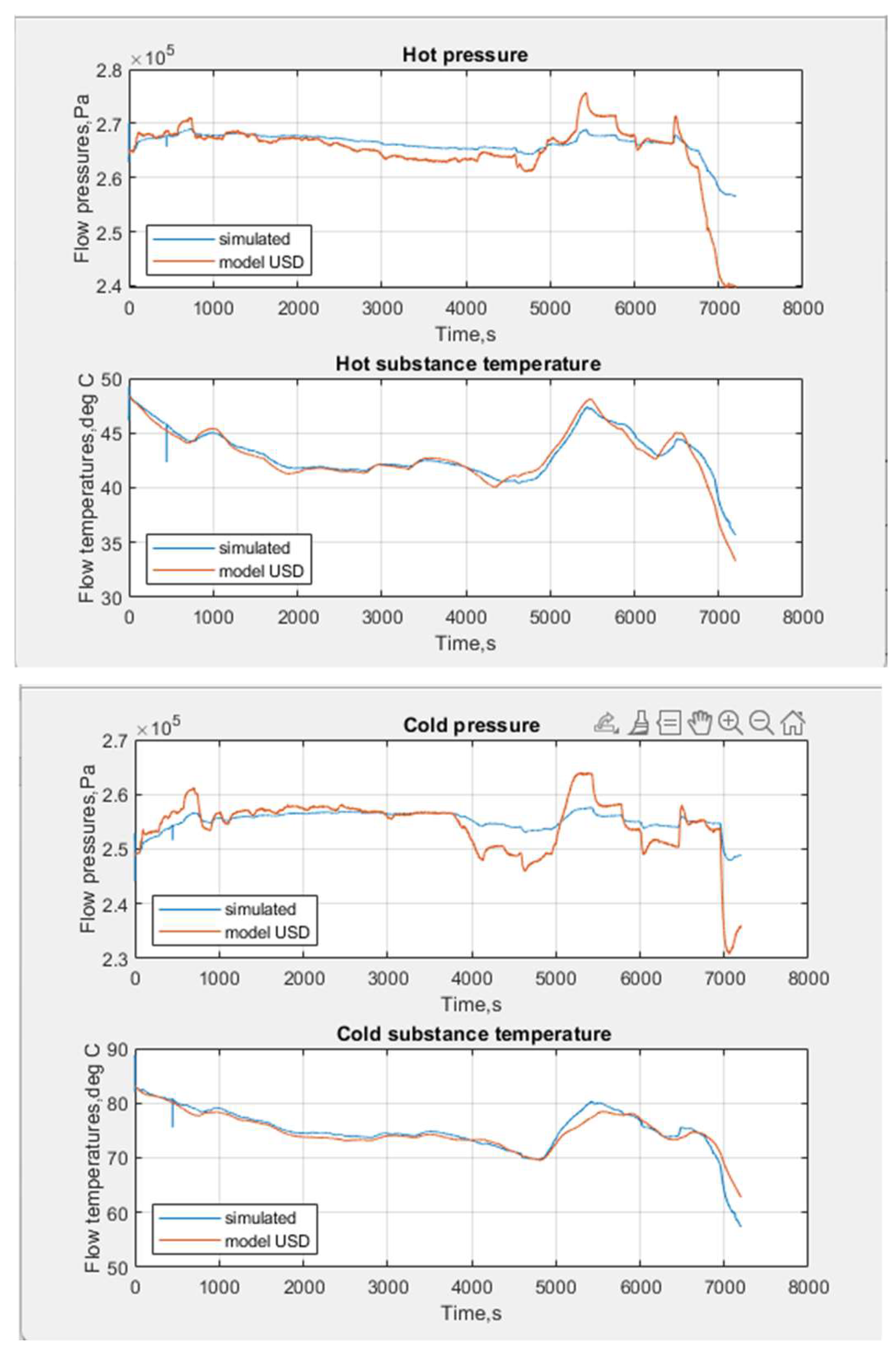

3.1.1. Modeling Results

3.2. Selecting Parameters for Estimation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valluru, J; Patwardhan, S.C. An Integrated Frequent RTO and Adaptive Nonlinear MPC Scheme Based on Simultaneous Bayesian State and Parameter Estimation. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2019, 58(18), pp. 7561-7578. [CrossRef]

- Kamalapurkar, R. Simultaneous state and parameter estimation for second-order nonlinear systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 56th Annual Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 12-15 December 2017; pp. 2164–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Bo.; Soumya, R.S.; Xunyuan, Y.; Jinfeng, L.; Sirish, L.S. Parameter and state estimation of one-dimensional infiltration processes: A simultaneous approach. Mathematics, 2020, 8(1), p.134, pp.1-22. [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E.; Bucy, R.S. New results in linear filtering and prediction theory. Journal of Basic Engineering, 1961, 83(1), pp. 95–108. [CrossRef]

- Grewal, M.S.; Andrews, A.P. Kalman Filtering: Theory and Practice Using MATLAB, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, USA, 2001; p. 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, V.; He, S.P.; Zhang, B.Y. State and parameter joint estimation of linear stochastic systems in presence of faults and non-Gaussian noises. International Journal of Robust and Nonlinear Control, 2020, 30(16), pp. 6683-6700. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Ding, F.; Hayat, T. Moving data window gradient-based iterative algorithm of combined parameter and state estimation for bilinear systems. International Journal of Robust and Nonlinear Control, 2020, 30(6), pp. 2413-2429. [CrossRef]

- Sobol’, I.M. Global sensitivity indices for nonlinear mathematical models and their Monte Carlo estimates. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 2001, Vol.55., Issues 1-3, pp. 271– 280. [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Annoni, P. How to avoid a perfunctory sensitivity analysis. Environmental Modelling & Software, 2010, 25(12), pp. 1508– 1517. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.B.; Gnanasekar, A.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Simultaneous state and parameter estimation: the role of sensitivity analysis. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2021, 60(7), pp. 2971-2982. [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.Z.; Benjamin, M.Sh.; Bo, K.; McAuley, K.; Bacon, D.W. Modeling Ethylene/Butene Copolymerization with Multi-site Catalysts: Parameter Estimability and Experimental Design. Polymer reaction engineering, 2003, 11(3), pp. 563–588. [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R.; Åström K.J. On structural Identifiability. Mathematical Biosciences, 1970, Vol.7., Issues 3-4, pp. 329–339. [CrossRef]

- Ljung, L.; Glad, T. On global identifiability for arbitrary model parametrizations. Automatica, Pergamon Press, Inc.: New York, USA, 1994, 30(2), pp. 265–276. [CrossRef]

- Kravaris, C.; Hahn, J.; Chu, Y.F. Advances and selected recent developments in state and parameter estimation. Computers & Chemical Engineering, 2013, 51(5), pp. 111-123. [CrossRef]

- Tasanbayev, S.; Uskenbayeva, G.; Kulniyazova, K.; Slastenov, I. Simultaneous estimation of states and parameters of a heat exchanger model using an extended Kalman filter. Bulletin of KazATC, 2023, 6(129), pp.111-120. [CrossRef]

- Semushin, I.V. Computational methods of algebra and estimation. Study guide, UlSTU, Inc.: Ulyanovsk, Russia, 2011; p. 366. ISBN 978-5-9795-0902-0.

- Box, G. E.; Draper, N. R. Response surfaces, mixtures, and ridge analyses, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, USA, 2006; p. 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T. Principal component analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer-Verglar: New-York, USA, 2002; p. 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. J. Subset selection in regression, 2nd ed.; CRC: New-York, USA, 2002; p. 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivorotko, O.I.; Andornaya, D.V.; Kabanikhin, S.I. Sensitivity analysis and practical identifiability of mathematical models of biology, Journal of Applied and Industr. Math., 2020, Vol.14, pp.115–130. [CrossRef]

- Lund, B.F.; Foss, B.A. Parameter ranking by orthogonalization - Applied to nonlinear mechanistic models, Automatica, 2008, 44(1), pp. 278-281. [CrossRef]

- Brun, R.; Reichert, P.; Kunsch, H.R. Practical identifiability analysis of large environmental simulation models, Water Resources Research., 2001; 37(4), pp. 1015-1030. [CrossRef]

- Omlin, M.; Brun, R.; Reichert P. Biogeochemical model of Lake Zurich: sensitivity, identifiability and uncertainty analysis, Ecological Modelling, 2001; 141(1-3), pp. 77-103. [CrossRef]

- Turanyi, T.; Nagy, T. Reduction of very large reaction mechanisms using methods based on simulation error minimization, Combustion and Flame., 2009; 156(2), pp. 417-428. [CrossRef]

- Degenring, D.; Froemel, C.; Dikta G.; Takors R. Sensitivity analysis for the reduction of complex metabolism models, J Process Control, 2004, 14(7), pp. 729-745. [CrossRef]

- Schittkowski, K. Experimental design tools for ordinary and algebraic differential equations, Ind Eng. Chem Res, 2007, 46(26), pp. 9137-9147. [CrossRef]

- Quaiser, T.; Monningmann, M. Systematic identifiability testing for unambiguous mechanistic modeling - application to JAK-STAT, MAP kinase, and NF-kappa B signaling pathway models. BMC Systems Biology, 2009, 3(50), pp. 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Sandink, C.A.; McAuley, K.B.; McLellan, P.J. Selection of parameters for updating in on-line models, Ind Eng Chem Res., 2001, 40(18), pp. 3936-3950. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.F.; Hahn, J. Parameter Set Selection via Clustering of Parameters into Pairwise Indistinguishable Groups of Parameters, Ind Eng Chem Res., 2009, 48(13), pp. 6000-6009. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.J.; Henson, M.A.; Kurtz, M.J. Selection of model parameters for off-line parameter estimation, IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol, 2004, 12(3), pp. 402-412. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.L.; Hahn, J. Parameter reduction for stable dynamical systems based on Hankel singular values and sensitivity analysis, Chem Eng Sci., 2006, 61(16), pp. 5393-5403. [CrossRef]

- Latyshenko, V.; Krivorotko, O.; Kabanikhin, S.; Zhang, Sh.; Kashtanova, V.; Yermolenko, D. Identifiability analysis of inverse problems in biology, In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computational Modeling, Simulation, and Applied Mathematics (CMSAM-2017), Beijing, China, October 22-23, 2017, pp. 567–571. [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, G.; Macchietto, S. Model-based design of experiments for parameter precision: State of the art, Chem Eng Sci., 2008, 63(19), pp. 4846-4872. [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.Y.; Xia, X.H.; Perelson, A.S.; Wu, H.L. On identifiability of nonlinear ODE models and applications in viral dynamics, SIAM Review, 2011, 53(1), pp. 3-39. [CrossRef]

- Haghtalab, A.; Mahmoodi, P, Mazloumi, S.H. A modified Peng–Robinson equation of state for phase equilibrium calculation of liquefied, synthetic natural gas, and gas condensate mixtures, The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 2011, 89(6), pp. 1376-1387. [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.Y.; Robinson, D.B. A new two-constant equation of state, Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam., 1976, 15(1), pp. 59–64. [CrossRef]

- Peng D.Y., Robinson D.B. Two and three phase equilibrium calculations for systems containing water, The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 1976, 54(5), pp.595–599. [CrossRef]

| Technological parameters of the simulated heat exchanger | |

| Volume of heat exchanger space with hot substance, , [] | 4.30 |

| Volume of space of heat exchanger with cold substance, , [] | 5.70 |

| Heat exchange surface area, A, [] | 60,32 |

| Specific heat capacity of the partition material, , [] | 473 |

| Parameters of the technological process | |

| Heat transfer coefficient from hot substance to partition, [W/m2*0С] | 298 |

| Heat transfer coefficient from partition to cold substance, [W/m2*0С] | 265 |

| Partition weight, [kg]; | 847 |

| Coefficient of hydraulic conductivity of hot space, | 7.532E-3 |

| Coefficient of hydraulic conductivity of cold space, | 7.724E-3 |

| Disturbances | Output variables | ||

| [] | [] | ||

| [] | [] | ||

| [] | |||

| Option for selecting a subset of parameters for identification | Input flow pressure, [Pa] | Input flow temperature, [C] | Output flow pressure, [Pa] | Output flow temperature, [C] |

| -1143.8 ± 13.460 | -0.15 ± 0.432 | -752.8 ± 13.9526 | -0.27±1.5989 | |

| 1-5424.5± 357.2365 | -2.75± 32.345 | -1424.7± 24.7563 | -4.75±5.7853 | |

| 1-5978.5± 462.2455 | -3.15± 34.869 | -1689.6± 31.4231 | -2.1±6.2153 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).