1. Introduction

Headache is a frequent symptom in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection[

1,

2], with a frequency ranging from 10% to 75% according to the different series [

3,

4,

5]. It has been reported as a presenting symptom of infection in both patients with and without a history of primary headache [

3,

6,

7].

Most patients with headache during SARS-CoV-2 infection meet criteria for acute systemic viral headache [

8]. The headache must have a temporal relationship with the onset of the viral infection, as well as with the worsening and improvement and/or resolution of the infection [

8,

9]. The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying its development are still under investigation. Some authors suggest that headache may result from direct activation of the trigeminal-vascular system by SARS-CoV2 or from the systemic inflammatory response and cytokine release [

3,

6,

10,

11]. When headache persists for more than three months, it is referred to as chronic systemic viral headache. Prospective patient series have shown that in 5% to 20% of cases, headache may continue after the resolution of SARS-CoV-2 infection, referred to as post-COVID-19 headache [

3,

12,

13].

The semiology of headache in COVID-19 appears to be heterogeneous. The most frequently described characteristics correspond to bilateral pain, of a throbbing quality in temporoparietal or frontal regions and of moderate to severe intensity [

14]. A recent phenotyping study of COVID-19 headache has described two predominant subtypes resembling two main types of primary headache: migraine-like and tension-type headache [

10,

14]. As described in different studies, COVID-19 headache with a migraine phenotype was more frequent after SARS-CoV-2.

Furthermore, headache is among the most frequently reported adverse effects following COVID-19 vaccination, with an incidence ranging from 30% to 52% in clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of various vaccine types [

15,

16,

17,

18]. In terms of semiological characteristics, both migraine-like and tension-type-like headache phenotypes have been identified in post-vaccination cases [

11].

Thus, to increase knowledge about headache in the context of acute infection, reinfection, and post- vaccination, we performed an observational study within a single cohort of patients to characterize the headache phenotype across these tree periods. Additionally, we explored its relationship with clinical variables, primary headache history, and persistent headache.

Our hypothesis is that both reinfection and COVID-19 vaccination may trigger headaches with characteristics similar to those observed during the primary SARS-CoV-2 infection. Likewise, the development of headache with infection may be influenced by the individual’s usual headache phenotype and could be associated with the subsequent development of post-COVID-19 headache.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

One-year observational descriptive study with retrospective cohort analysis of healthcare workers with COVID-19 headache from a tertiary hospital in the Community of Madrid. The patients were initially assessed using a questionnaire administered by the Occupational Medicine Department. The variables related to headache were collected through a semi-structured telephone interview conducted by physicians belonging to the Neurology Department. Recruitment followed a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method and all patients with COVID-19 headache were assessed for eligibility.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria included healthcare workers with PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (via nasopharyngeal swab) who experienced infection-related headache, had documentation from the Occupational Medicine Department, and consented to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were individuals under 18 years of age and those with severe neurological disease hindering communication.

2.3. Variables Included in the Study

The following demographic and clinical characteristics were evaluated by the Occupational Medicine Department: sex, age, weight (kg), body mass index (BMI), obesity (BMI 30> kg/m²), high blood pressure (HBP), dyslipidemia (DL), diabetes mellitus (DM), smoker history, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), anxiety, depression, fibromyalgia, history of headache and frequency (<1 pain day per month, 1-10 days and >10 days) and evaluation by neurologists.

Headache-related variables were collected through semi-structured telephone interviews conducted by the Neurology Department. The data included characteristics of the headache such as location (holocranial or hemicranial), quality (pulsatile, stabbing, or oppressive), and intensity rated on a 0–10 scale (with 1–5 considered mild to moderate and 6–10 moderate to severe). Additional symptoms were also recorded, including the presence of photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia, nausea or vomiting, and clinophilia. These variables were assessed during the acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, reinfection, and post-vaccination periods. Diagnostic criteria for migraine and tension-type headache were applied according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) (18). If the ICHD-3 criteria were not met or we did not have sufficient data to classify the patients in the previous groups, “other” headache profile was considered. The duration of COVID-19-related headache was recorded, and patients whose headache persisted for more than three months were classified as having post-COVID-19 headache.

Additionally, other persistent symptoms (present for more than 3 months) were also recorded: tachycardia, fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia, asthenia, ageusia, anosmia, odynophagia, insomnia, lack of concentration, nausea, arthralgia, dizziness, paresthesia, gait instability.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables with a normal distribution are presented using means and standard deviations (SD), while those with non-normal distribution are reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Qualitative variables are expressed as relative frequencies and percentages. The distribution of quantitative variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to evaluate conformity with a Gaussian distribution. When normality assumptions were not met, non-parametric statistical methods were applied. Statistical tests were two-tailed with a significance level of 5%. Analyses were performed using R software, version 4.2.1 (

http://www.R-project.org; the R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

2.5. Ethics Committee Approval

The study has been approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario de la Princesa (Number: 4507, on 10-05-21). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [

19]. All participants gave their written informed consent prior to participation.

3. Results

3.1. Population Demography

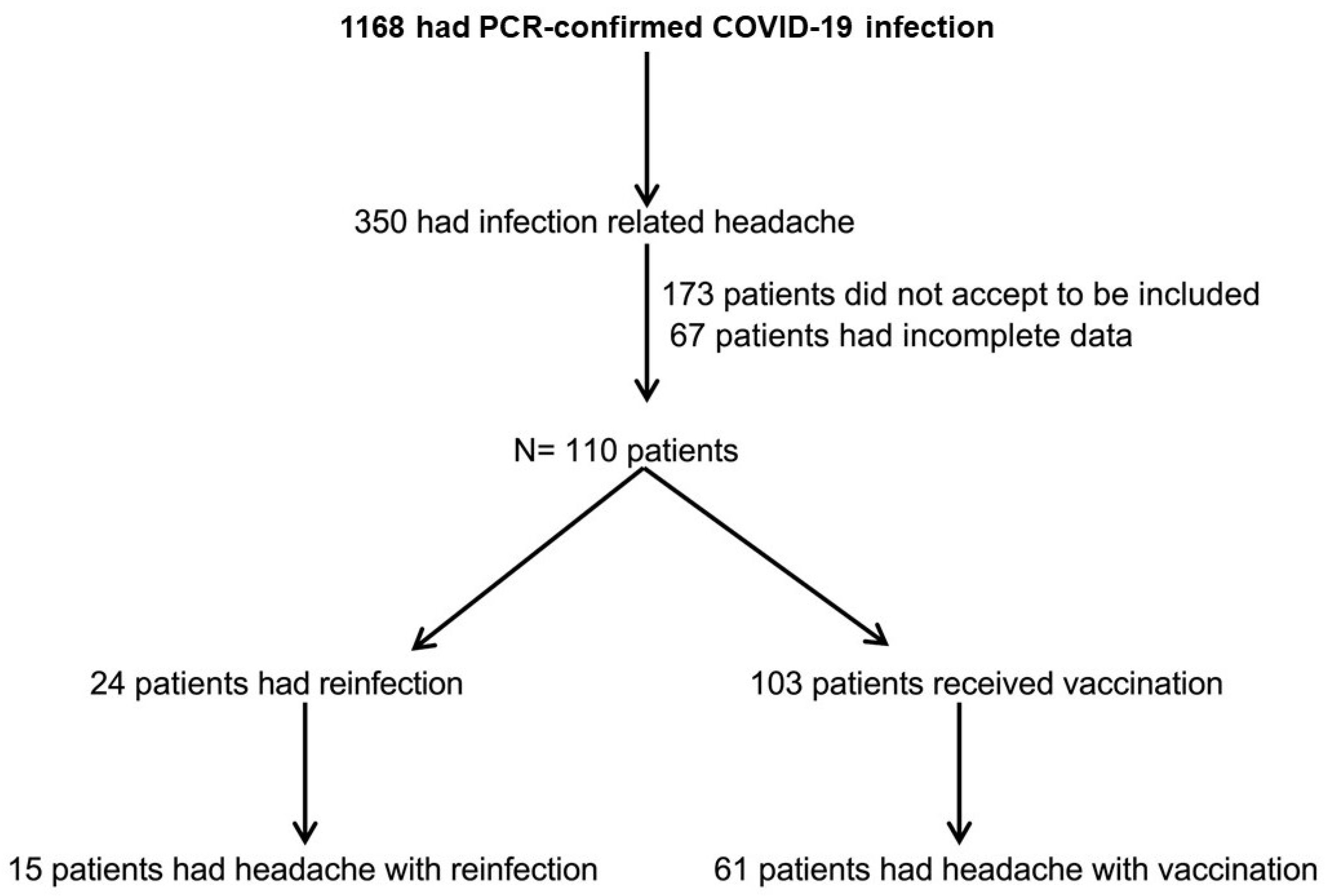

Out of 1.168 health workers at the Hospital Universitario de la Princesa with SARS-CoV-2 infection, 350 had COVID-19 headache, and 109 patients agreed to participate in the study. Among them, 15 reported headache associated with reinfection, and 61 experienced headache following vaccination (

Figure 1).

Among the 109 patients with COVID-19-related headache, 49.5% (54/109) met the ICHD-3 criteria for tension-type headache and 12.8% (14/109) for migraine. Baseline characteristics of the study population, stratified by COVID-19 headache phenotype (migraine, tension-type, or other), are presented in

Table 1. Obesity was more frequently observed in patients with a migraine-like headache phenotype (28%) compared to those with tension-type (5%) or other headache types (7%) during COVID-19 infection (p = 0.045).

3.2. Profile of COVID-19 Headache in Relation to Primary Headache, During Reinfection and Post-Vaccination

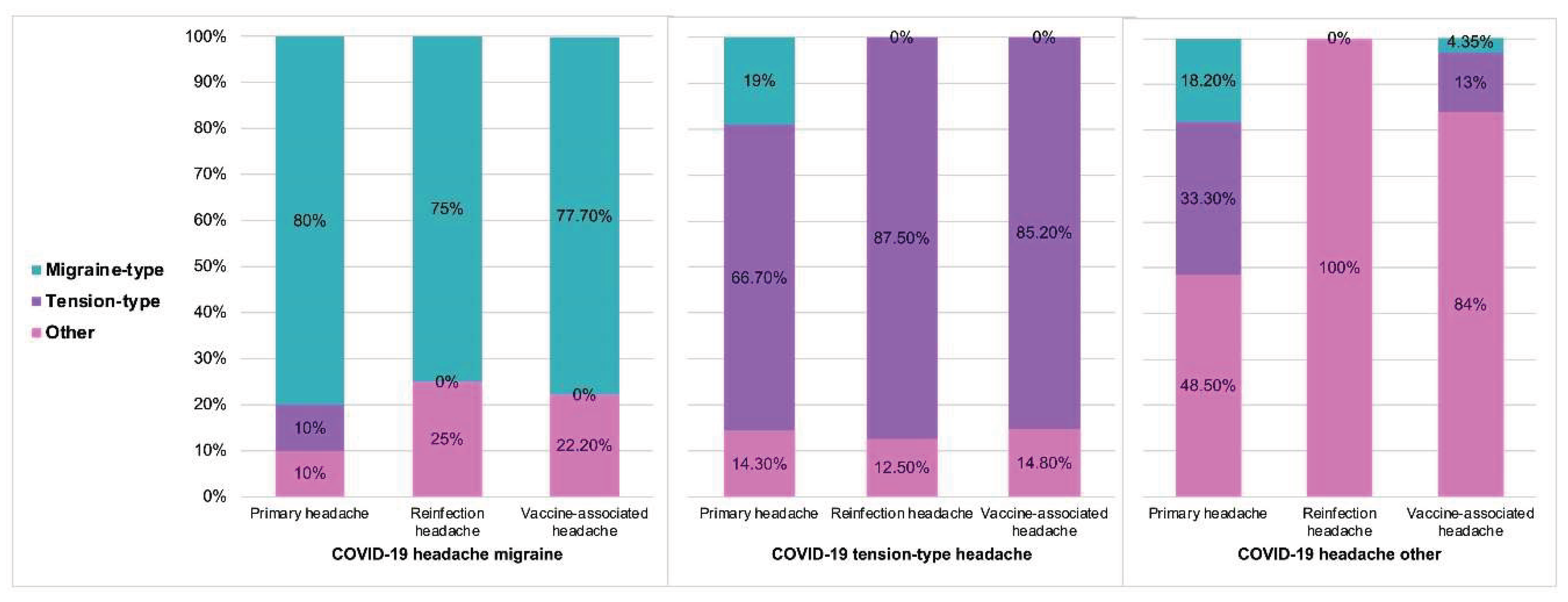

Among patients with COVID-19-related headache, 77.9% (85/109) had a prior diagnosis of primary headache, and 67% (73/109) had previously been evaluated by a neurologist. Of those with a history of primary headache, 25.9% (22/85) met criteria for migraine and 47.1% (40/85) for tension-type headache.

During reinfection, 62.5% (15/24) of the patients reported headache. Among these, 20% (3/15) presented with a migraine and 46.6% (7/15) with a tension type headache. Regarding post-vaccination headache, 59.2% (61/103) of vaccinated individuals presented headache, of which 13.1% (8/61) were migraine-like and 42.6% (26/61) tension-type. Post-vaccination headache occurred more frequently after the first and second doses, occurring in 75.4% (46/61) and 82% (50/61) respectively. After the third dose, 60.6% (37/61) reported headache. The main findings are shown in

Figure 2, while detailed information on COVID-19 headache phenotype in relation to primary headache, reinfection, and post-vaccination headache are presented in

Table A1.

The prevalence of primary headache was 70-80% in the three groups. Patients with a migraine-like COVID-19 headache were significantly more likely to have a history of primary migraine (p=0.001), while those with a tension-type COVID-19 headache were more likely to have a history of primary tension-type headache (p=0.001). Regarding reinfection, there were no differences in the percentage of headache during reinfection according to the profile of the COVID-19 headache. However, a migraine-like profile during reinfection was more frequent in patients who had experienced a migraine-like headache during the initial COVID-19 episode (75% vs. 0% in other groups; p = 0.014), and a tension-type profile during reinfection was more frequent in those with a previous tension-type COVID-19 headache (87% vs. 0%; p = 0.001). No significant differences were observed in the overall prevalence of post-vaccination headache among the three groups. However, patients with a migraine-like COVID-19 headache were more likely to experience a migraine-type headache post-vaccination, while those with a tension-type COVID-19 headache typically experienced a tension-type headache after vaccination. Headache characteristics of the headache classified as “other” primary and “other” COVID-19 headache are included in

Table A2.

In the multivariate analysis, a history of primary migraine headache [OR 0.17 (0.04-0.60), p=0.0269] and tension-type headache [OR 0.21 (0.07-0.624), p= 0.019] was independently associated with the COVID-19 headache profile (

Table 2).

3.3. Post-COVID-19 Headache Profile

In our cohort, 22.9% (25/109) patients presented persistent COVID-19 headache. As shown in

Table 3, these patients were more likely to be obese (28% vs. 4%; p = 0.001) and had a higher prevalence of anxiety (p = 0.041) and fibromyalgia (p = 0.028) compared to those without persistent headache.

No differences were found between other baseline characteristics or with the primary headache profile. Several semiological characteristics of the COVID-19 headache – hemicranial location, photophobia, sonophobia and strong intensity – were significantly associated with the presence of persistent headache (

Table 4). No other persistent symptoms were associated with the presence of post-COVID-19 headache (

Table A3).

In the multivariate model we found that the presence of fibromyalgia [OR 28.8 (5.32-317.68), p=0.003] and obesity [OR 14.1 (3.3-77.05), p=0.004] were independently associated with persistent headache (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

The results of this study show the association between the headache profile during SARS-CoV-2 infection and the pain phenotype during reinfection and post-vaccination period, as well as with the patient’s prior history of primary headache. To our knowledge, the simultaneous relationship of headache phenotypes across these three contexts has not been previously described.

In our sample, the most common COVID-19 headache phenotype was tension-type, observed in 49.5% of cases, while only 12.8% of patients met ICHD-3 criteria for migraine. These results are aligned with those previously reported, indicating a frequency of 50% and 20% of tension-type headache and migraine, respectively [

5,

20]. The pathophysiological mechanisms that determine the development of one phenotype over another remain unclear. The migraine phenotype (high-intensity, pulsating quality and associated with nausea) has been associated with inflammatory markers linked to more severe COVID-19 presentations, such as thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia, and hyperferritinemia. In contrast, the tension-type phenotype (oppressive quality and mild-moderate intensity) was present in patients with lower levels of these inflammatory markers [

14]. Additionally, the manifestations of a specific headache phenotype during COVID-19 could be influenced by the previous presence of patients with different subtypes of primary headache (migraine or tension-type headache). Previous studies have described that secondary headaches are often related to the pre-existing primary headache [

21].

For this reason, we studied the proportion of patients with a history of primary headache and evaluated whether it could predict the headache phenotype during COVID-19. Our results showed that a history of migraine or previous tension headache was independently associated with the development of the same phenotype during SARS-CoV-2 infection. The prevalence of primary headache in our cohort was 70-80%, indicating that most patients with COVID-19-related headache had a history of known primary headache, consistent with data already reported [

5,

22]. The baseline characteristics across the three groups, based on the headache phenotype during COVID-19, were similar, with the exception of a higher percentage of obesity among patients with a migraine phenotype.

As for the percentage of headache during reinfection, we found that more than half of the patients presented headache, with tension type being more frequent (46.6% tension type vs 20% migraine type), as occurred during the initial infection. Similar to what has been previously described related to primary headache, patients with a migraine profile or tension during the initial COVID-19 episode tended to present similar semiological characteristics upon reinfection.

Post-vaccination headache appeared in more than half of the patients (59.2%). This type of headache is mostly a reversible pain. It typically occurs within the first few days after receiving the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and is generally short-lived, often lasting less than 24 hours [

11,

23,

24]. It has been shown that the presence of post-vaccination headache is more frequent in patients with a history of primary headache, especially those with chronic and high frequency headache, and in such cases, the headache often resembles their usual episodes [

25]. The most frequently reported phenotype is tension type, accounting for approximately 70% of cases according to recent data [

5]. While the pain does not meet the criteria for migraine, up to one third of the patients may have migraine characteristics, especially in those patients with a history of pre-existing migraine [

11]. In our study, the tension phenotype was more frequent than the migraine phenotype (42.6% vs. 13.1% of vaccinated patients). Overall, the post-vaccination headache showed characteristics similar to the phenotype found in headache during initial COVID-19.

There are some differences in incidence related to different types and doses of vaccine [

11]. While some studies reported a higher occurrence after the second dose [

5,

26], others found it to be more common after the first dose of vaccine [

11,

24]. Vaccination triggers an innate immune response, leading to the release of cytokines that mediate the acute phase. Serum concentrations of some cytokines, such as gamma interferon or interleukin-6, have been found to increase after the second vaccine dose, which could explain a higher prevalence of headache after the second immunization [

11]. In our study, the frequency was slightly higher after the second dose (82%) in comparison with the first dose (75.4%).

Finally, regarding persistent headache, 23% of patients in our study reported headache for more than 3 months. Although other persistent symptoms were studied, no significant association with headache was found. In the univariate analysis, obesity, fibromyalgia, and anxiety were significantly more frequent in patients with persistent headache compared to those without. In the multivariate model, obesity and fibromyalgia remained as predictors of persistent headache. In the literature, persistent COVID-19 headache has been described in up to 20% of patients [

5,

13]. Following the acute phase, some patients experience persistent symptoms, including headache, known as post-COVID-19 syndrome. This scenario is increasingly observed in clinical practice [

27,

28].

The mechanisms underlying the development of persistent COVID-19 headache remain unclear, likely involving multiple pathophysiological pathways. A migrainous phenotype has been more frequently described in these patients, suggesting that persistent headache is a chronification of migraine in patients with a pre-existing diagnosis. The possibility of an acquired activation of the trigeminovascular system after infection has also been proposed [

13,

27]. Although our study did not find significant differences regarding the headache profile between patients with and without persistent headache, we did observe a higher frequency of migraine characteristics (hemicranial pain, photo and sonophobia, and strong intensity) among those patients with persistent headache.

The main limitation of this study is that it is an analysis of a retrospective cohort with a small sample size, which may have limited the ability to detect some significant associations within the current series. A larger-scale study would provide useful information that could corroborate our results and further clarify the factors contributing to persistent COVID-19 headache.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest that the headache profile observed during COVID-19 tends to recur in patients during reinfection and after vaccination and is closely related to the patient’s primary headache type. Persistent headaches are more likely to develop in patients with obesity and fibromyalgia and often follows a migraine pattern.

These findings may assist in our clinical practice by enabling a more targeted treatment approach based on headache semiology and focusing our attention on patients with a higher susceptibility to persistent pain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ABGV and MDG.; methodology, ABGV and MDG.; formal analysis, ABGV, MDG, AGM, PPB, AS, CR, ABLR, AMC, ALGA, MGC, JV; investigation, MDG, PPB, AS, AMC, ALGA, MGC ; data curation, MDG, PPB and AGM; writing—original draft preparation, ABGV and MDG; writing—review and editing, ABGV, MDG, AGM, PPB, AS, CR, ABLR, AMC, ALGA, MGC, JV; supervision, ABGV, JV and MGC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario de la Princesa (Number: 4507).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared at the request of any qualified researcher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participating patients, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Alicia Gonzalez-Martinez has received education funding from Lilly, Novartis, Roche, TEVA, Abbvie-Allergan, & Daichi. Dr. José Vivancos has served as speaker, consultant, and advisory member for or has received research funding from MSD, Pfizer, Daychii-Sankyo, Bayer, Sandoz, Bristol Myers Skibb, Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Almirall, Sanofi-Aventis and Ferrer Pharma. Dr. Ana Beatriz Gago-Veiga has received honoraria from Lilly, Novartis, TEVA, Abbvie-Allergan, Exeltis & Chiesi. The rest of the authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

Appendix A

Table A1.

COVID-19 headache phenotype according to primary headache, headache during reinfection and headache after vaccine. *p<0.05;**p<0.01;***p<0.001.

Table A1.

COVID-19 headache phenotype according to primary headache, headache during reinfection and headache after vaccine. *p<0.05;**p<0.01;***p<0.001.

| |

COVID-19

headache

Migraine

N=14 |

COVID-19

headache

Tension-type

N=54 |

COVID-19

headache

Other

N=41 |

p value |

| Primary headache (85/109)1 |

10/14 (71.4%) |

42/54 (77.7%) |

33/41 (80.4%) |

|

| Migraine (22/85) |

8/10 (80.0%) |

8/42 (19.0%) |

6/33 (18.2%) |

0.001*** |

| Tension-type (40/85) |

1/10 (10.0%) |

28/42 (66.7%) |

11/33 (33.3%) |

0.001*** |

| Other (23/85) |

1/10 (10.0%) |

6/42 (14.3%) |

16/33 (48.5%) |

0.002** |

| Reinfected (24/109) |

4/14 (28.57%) |

13/54 (24.07%) |

7/41 (17.1%) |

0.511 |

| Headache phenotype after reinfection (15/24)2 |

4/4 (100%) |

8/13 (61.5%) |

3/7 (42.8%) |

0.402 |

| Migraine (3/15) |

3/4 (75.0%) |

0/8 (0.00%) |

0/3 (0.00%) |

0.011* |

| Tension-type (7/15) |

0/4 (0.00%) |

7/8 (87.5%) |

0/3 (0.00%) |

0.001*** |

| Other (5/15) |

1/4 (25.0%) |

1/8 (12.5%) |

3/3 (100%) |

0.030* |

| Vaccinated (103/109) |

13/14 (92.8%) |

50/54 (92.5%) |

40/41 (97.5%) |

|

| Headache phenotype after vaccine (61/103)3 |

9/13 (69.2%) |

27/50 (54.0%) |

25/40 (62.5%) |

0.527 |

| Migraine (8/61) |

7/9 (77.7%) |

0/27 (0.00%) |

1/25 (4.35%) |

<0.001*** |

| Tension-type (26/61) |

0/9 (0.00%) |

23/27 (85.2%) |

3/25 (13.0%) |

<0.001*** |

| Other (27/61) |

2/9 (22.2%) |

4/27 (14.8%) |

21/25 (84%) |

<0.001*** |

Table A2.

Persistent symptoms in post-COVID-19 headache.

Table A2.

Persistent symptoms in post-COVID-19 headache.

| |

Non-Persistent (N=84) |

Persistent (N= 25) |

p value |

| Tachycardia, n (%) |

3 (5.26) |

0 (0) |

0.553 |

| Fever, n (%) |

0 (0) |

1 (4.3) |

0.288 |

| Cough, n (%) |

11 (19.3) |

2 (8.7) |

0.328 |

| Dysnea, n (%) |

22 (38.6) |

14 (60.9) |

0.118 |

| Muscle pain, n (%) |

18 (31.6) |

10 (41.7) |

0.538 |

| Asthenia, n (%) |

37 (64.9) |

16 (66.7) |

1.000 |

| Ageusia, n (%) |

10 (17.2) |

7 (29,2) |

0.243 |

| Anosmia, n (%) |

13 (22.8) |

6 (25) |

1.000 |

| Odynophagia, n (%) |

5 (8.6) |

1 (4,2) |

0.666 |

| insomnia, n (%) |

2 (3.4) |

0 (0) |

1.000 |

| Lack of concentration, n (%) |

3 (5.2) |

2 (8.30) |

0.627 |

| Nausea, n (%) |

0 (0) |

2 (8.30) |

0.083 |

| Arthralgia, n (%) |

1 (1.7) |

1 (4.20) |

0.502 |

| Dizziness, n (%) |

7 (12.1) |

0 (0) |

0.100 |

| Paresthesia, n (%) |

2 (3.4) |

2 (8.30) |

0.577 |

| Gait instability, n (%) |

0 (0) |

1 (4.20) |

0.293 |

Table A3.

Headache characteristics of headache classified as other primary and other COVID-19 headache.

Table A3.

Headache characteristics of headache classified as other primary and other COVID-19 headache.

| Variables |

Other primary headache (23) |

Other COVID-19 headache (41) |

| Hemicranial, n (%) |

8 (35) |

1 (3) |

| Holocranial, n (%) |

1 (5) |

5 (12) |

| Throbbing, n (%) |

6 (26) |

1 (3) |

| Oppressive, n (%) |

5 (22) |

7 (17) |

| Mild-moderate intensity, n (%) |

5 (22) |

5 (12) |

| Moderate-severe intensity, n (%) |

18 (78) |

8 (20) |

| Clinophilia, n (%) |

10 (43) |

3 (7) |

| Nausea/vomit, n (%) |

4 (17) |

8 (20) |

| Photophobia, n (%) |

6 (26) |

10 (41) |

| Sonophobia, n (%) |

2 (9) |

4 (10) |

References

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Navarro-Santana, M.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; et al. Headache as an acute and post-COVID-19 symptom in COVID-19 survivors: A meta-analysis of the current literature. Eur J Neurol 2021, 28, 3820–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Martinez, A.; Fanjul, V.; Ramos, C.; Ballesteros, J.S.; Bustamante, M.; Martí, A.V.; Álvarez, C.; del Álamo, Y.G.; Vivancos, J.; Gago-Veiga, A.B. Headache during SARS-CoV-2 infection as an early symptom associated with a more benign course of disease: a case–control study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 3426–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, L.; Jin, H.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; He, Q.; Chang, J.; Hong, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caronna, E.; Hoek, T.C.v.D.; Bolay, H.; Garcia-Azorin, D.; Gago-Veiga, A.B.; Valeriani, M.; Takizawa, T.; Messlinger, K.; E Shapiro, R.; Goadsby, P.J.; et al. Headache attributed to SARS-CoV-2 infection, vaccination and the impact on primary headache disorders of the COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive review. Cephalalgia 2023, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, J.; Gonzalez-Martinez, A.; García-Blanco, M.J.; et al. Headache and impaired consciousness level associated with SARS-CoV-2 in CSF: A case report. Neurology 2020, 95, 266–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta-Etessam, J.; Matías-Guiu, J.A.; González-García, N.; Iglesias, P.G.; Santos-Bueso, E.; Arriola-Villalobos, P.; García-Azorín, D. Spectrum of Headaches Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Study of Healthcare Professionals. Headache: J. Head Face Pain 2020, 60, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J.; Bes, A.; Kunkel, R.; et al. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013, 33, 629–808. [Google Scholar]

- Baykan, B.; Ozge, A.; Ertas, M.; Atalar, A.C.; Bolay, H. Urgent need for ICHD criteria for COVID-19-related headache: Scrutinized classification opens the way for research. Noro Psikiyatr. Arsivi 2021, 58, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.T.; García-Azorín, D.; Planchuelo-Gómez, Á.; García-Iglesias, C.; Dueñas-Gutiérrez, C.; Guerrero, Á.L. Phenotypic characterization of acute headache attributed to SARS-CoV-2: An ICHD-3 validation study on 106 hospitalized patients. Cephalalgia 2020, 40, 1432–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, M.; Waliszewska-Prosół, M.; Koutsokera, M.; Robotti, M.; Straburzyński, M.; Apostolakopoulou, L.; Capizzi, M.; Çibuku, O.; Ambat, F.D.F.; Frattale, I.; et al. Headache onset after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J. Headache Pain 2022, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caronna, E.; Ballvé, A.; Llauradó, A.; Gallardo, V.J.; Ariton, D.M.; Lallana, S.; Maza, S.L.; Gadea, M.O.; Quibus, L.; Restrepo, J.L.; et al. Headache: A striking prodromal and persistent symptom, predictive of COVID-19 clinical evolution. Cephalalgia 2020, 40, 1410–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Azorin, D.; Layos-Romero, A.; Porta-Etessam, J.; A Membrilla, J.; Caronna, E.; Gonzalez-Martinez, A.; Mencia, Á.S.; Segura, T.; Gonzalez-García, N.; Díaz-De-Terán, J.; et al. Post-COVID-19 persistent headache: A multicentric 9-months follow-up study of 905 patients. Cephalalgia 2022, 42, 804–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchuelo-Gómez, Á.; Trigo, J.; de Luis-García, R.; Guerrero, Á.L.; Porta-Etessam, J.; García-Azorín, D. Deep Phenotyping of Headache in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients via Principal Component Analysis. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 583870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meo, S.A.; Bukhari, I.A.; Akram, J.; Meo, A.S.; Klonoff, D.C. COVID-19 vaccines: Comparison of biological, pharmacological characteristics and adverse effects of Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna Vaccines. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 1663–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göbel, C.H.; Heinze, A.; Karstedt, S.; Morscheck, M.; Tashiro, L.; Cirkel, A.; Hamid, Q.; Halwani, R.; Temsah, M.-H.; Ziemann, M.; et al. Clinical characteristics of headache after vaccination against COVID-19 (coronavirus SARS-CoV-2) with the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine: a multicentre observational cohort study. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, C.H.; Heinze, A.; Karstedt, S.; Morscheck, M.; Tashiro, L.; Cirkel, A.; Hamid, Q.; Halwani, R.; Temsah, M.-H.; Ziemann, M.; et al. Headache Attributed to Vaccination Against COVID-19 (Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2) with the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) Vaccine: A Multicenter Observational Cohort Study. Pain Ther. 2021, 10, 1309–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, R.K.; Paliwal, V.K. Spectrum of neurological complications following COVID-19 vaccination. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 43, 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [CrossRef]

- Schankin, C.J.; Straube, A. Secondary headaches: Secondary or still primary? Journal of Headache and Pain 2012, 13, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hashel, J.Y.; Abokalawa, F.; Alenzi, M.; Alroughani, R.; Ahmed, S.F. Coronavirus disease-19 and headache; impact on pre-existing and characteristics of de novo: a cross-sectional study. J. Headache Pain 2021, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestro, M.; Tessitore, A.; Orologio, I.; Sozio, P.; Napolitano, G.; Siciliano, M.; Tedeschi, G.; Russo, A. Headache Worsening after COVID-19 Vaccination: An Online Questionnaire-Based Study on 841 Patients with Migraine. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekizoglu, E.; Gezegen, H.; Dikmen, P.Y.; Orhan, E.K.; Ertaş, M.; Baykan, B. The characteristics of COVID-19 vaccine-related headache: Clues gathered from the healthcare personnel in the pandemic. Cephalalgia 2021, 42, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, K.; Watanabe, N.; Miyazaki, N.; Ishizuchi, K.; Iba, C.; Tagashira, Y.; Uno, S.; Shibata, M.; Hasegawa, N.; Takemura, R.; et al. Incidence of headache after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with history of headache: A cross-sectional study. Cephalalgia 2021, 42, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Peng, Y.; Shen, E.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, P.; Guo, C.; Feng, Z.; Gao, L.; Zhang, X.; et al. A comprehensive analysis of the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 2794–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caronna, E.; Alpuente, A.; Torres-Ferrus, M.; Pozo-Rosich, P. Toward a better understanding of persistent headache after mild COVID-19: Three migraine-like yet distinct scenarios. Headache: J. Head Face Pain 2021, 61, 1277–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceban, F.; Ling, S.; Lui, L.M.; Lee, Y.; Gill, H.; Teopiz, K.M.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Cao, B.; et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2021, 101, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Florencio, L.L. Defining Post-COVID Symptoms (Post-Acute COVID, Long COVID, Persistent Post-COVID): An Integrative Classification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or propery resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).