Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Background and Context

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Inclusion

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Clinical Examination

2.4. Sample Collection

2.5. Sample Analysis

2.5.1. aMMP-8 Quantification

2.5.2. Microbial Profiling

2.5.3. Genetic Polymorphism Analysis

2.5.4. MMP-8 Gene Expression

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Predictors of Peri-Implantitis

3.4. Predictors of Bleeding on Probing (BOP%)

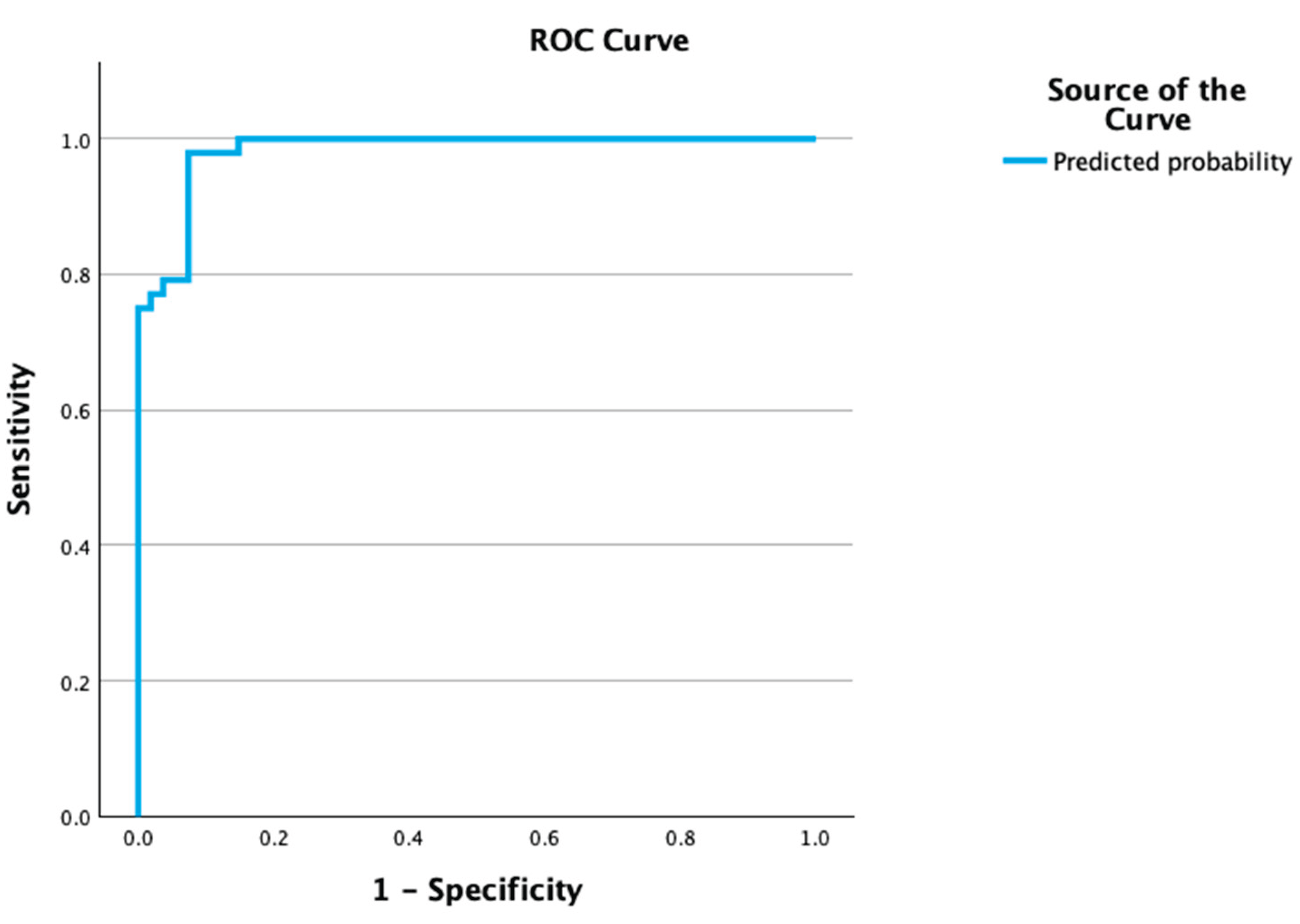

3.5. Personalized Risk Assessment Tool Development and Validation

- Low risk: 0–2 points

- Moderate risk: 3–5 points

- High risk: 6–7 points

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- H. W. Elani, J. R. Starr, J. D. Da Silva, and G. O. Gallucci, “Trends in Dental Implant Use in the U.S., 1999-2016, and Projections to 2026,” J Dent Res, vol. 97, no. 13, pp. 1424–1430, Dec. 2018, doi: 10.1177/0022034518792567.

- T. Berglundh et al., “Peri-implant diseases and conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions,” J Periodontol, vol. 89, pp. S313–S318, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.1002/JPER.17-0739.

- J. Derks and C. Tomasi, “Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology,” Apr. 01, 2015. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12334.

- T. Berglundh, A. Mombelli, F. Schwarz, and J. Derks, “Etiology, pathogenesis and treatment of peri-implantitis: A European perspective,” Periodontol 2000, 2024, doi: 10.1111/PRD.12549,.

- D. Hashim, N. Cionca, C. Combescure, and A. Mombelli, “The diagnosis of peri-implantitis: A systematic review on the predictive value of bleeding on probing,” Clin Oral Implants Res, vol. 29 Suppl 16, pp. 276–293, Oct. 2018, doi: 10.1111/CLR.13127.

- A. Ramanauskaite and G. Juodzbalys, “Diagnostic Principles of Peri-Implantitis: a Systematic Review and Guidelines for Peri-Implantitis Diagnosis Proposal,” J Oral Maxillofac Res, vol. 7, no. 3, p. e8, Sep. 2016, doi: 10.5037/JOMR.2016.7308.

- Carcuac and T. Berglundh, “Composition of human peri-implantitis and periodontitis lesions,” J Dent Res, vol. 93, no. 11, pp. 1083–1088, Nov. 2014, doi: 10.1177/0022034514551754.

- Fragkioudakis, G. Konstantopoulos, C. Kottaridi, A. E. Doufexi, and D. Sakellari, “Quantitative assessment of Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis in peri-implant health and disease: correlation with clinical parameters,” J Med Microbiol, vol. 73, no. 11, 2024, doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001933.

- S. M. Dabdoub, A. A. Tsigarida, and P. S. Kumar, “Patient-specific analysis of periodontal and peri-implant microbiomes,” J Dent Res, vol. 92, no. 12 Suppl, Dec. 2013, doi: 10.1177/0022034513504950.

- É. B. S. Carvalho, M. Romandini, S. Sadilina, A. C. P. Sant’Ana, and M. Sanz, “Microbiota associated with peri-implantitis—A systematic review with meta-analyses,” Nov. 01, 2023, John Wiley and Sons Inc. doi: 10.1111/clr.14153.

- V. Xanthopoulou, I. T. Räisänen, T. Sorsa, D. Tortopidis, and D. Sakellari, “Diagnostic value of aMMP-8 and azurocidin in peri-implant sulcular fluid as biomarkers of peri-implant health or disease,” Clin Exp Dent Res, vol. 10, no. 3, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1002/cre2.883.

- A. Al-Majid, S. Alassiri, N. Rathnayake, T. Tervahartiala, D. R. Gieselmann, and T. Sorsa, “Matrix metalloproteinase-8 as an inflammatory and prevention biomarker in periodontal and peri-implant diseases,” 2018, Hindawi Limited. doi: 10.1155/2018/7891323.

- S. Alassiri et al., “The Ability of Quantitative, Specific, and Sensitive Point-of-Care/Chair-Side Oral Fluid Immunotests for aMMP-8 to Detect Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases,” 2018, Hindawi Limited. doi: 10.1155/2018/1306396.

- K. Murthykumar, S. Varghese, and J. V. Priyadharsini, “Association of MMP8 (-799C/T) (rs11225395) gene polymorphism and chronic periodontitis,” 2019.

- Y. H. Chou et al., “MMP-8-799 C>T genetic polymorphism is associated with the susceptibility to chronic and aggressive periodontitis in Taiwanese,” J Clin Periodontol, vol. 38, no. 12, pp. 1078–1084, Dec. 2011, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01798.x.

- L. Izakovicova Holla, B. Hrdlickova, J. Vokurka, and A. Fassmann, “Matrix metalloproteinase 8 (MMP8) gene polymorphisms in chronic periodontitis,” Arch Oral Biol, vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 188–196, Feb. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.08.018.

- P. S. Kumar, S. M. Dabdoub, R. Hegde, N. Ranganathan, and A. Mariotti, “Site-level risk predictors of peri-implantitis: A retrospective analysis,” J Clin Periodontol, vol. 45, no. 5, pp. 597–604, May 2018, doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12892.

- T. Mameno et al., “Predictive modeling for peri-implantitis by using machine learning techniques,” Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1038/S41598-021-90642-4.

- F. Schwarz, J. Derks, A. Monje, and H. L. Wang, “Peri-implantitis,” J Clin Periodontol, vol. 45, pp. S246–S266, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12954.

- S. Renvert, G. R. Persson, F. Q. Pirih, and P. M. Camargo, “Peri-implant health, peri-implant mucositis, and peri-implantitis: Case definitions and diagnostic considerations,” J Periodontol, vol. 89, pp. S304–S312, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.1002/JPER.17-0588.

- N. P. Lang and P. M. Bartold, “Periodontal health,” J Periodontol, vol. 89, pp. S9–S16, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.1002/JPER.16-0517.

- G. Emingil et al., “Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP)-8 and Tissue Inhibitor of MMP-1 (TIMP-1) Gene Polymorphisms in Generalized Aggressive Periodontitis: Gingival Crevicular Fluid MMP-8 and TIMP-1 Levels and Outcome of Periodontal Therapy,” J Periodontol, vol. 85, no. 8, pp. 1070–1080, Aug. 2014, doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130365.

- P. Peduzzi, J. Concato, E. Kemper, T. R. Holford, and A. R. Feinstem, “A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis,” J Clin Epidemiol, vol. 49, no. 12, pp. 1373–1379, Dec. 1996, doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3.

- R. D. Riley et al., “Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model,” BMJ, vol. 368, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1136/BMJ.M441.

- Fragkioudakis, L. Batas, I. Vouros, and D. Sakellari, “Diagnostic Accuracy of Active MMP-8 Point-of-Care Test in Peri-Implantitis,” Eur J Dent, 2024, doi: 10.1055/s-0044-1793843.

- T. Sorsa et al., “Analysis of matrix metalloproteinases, especially MMP-8, in gingival creviclular fluid, mouthrinse and saliva for monitoring periodontal diseases,” Periodontol 2000, vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 142–163, Feb. 2016, doi: 10.1111/PRD.12101.

- C. A. Ramseier, “Diagnostic measures for monitoring and follow-up in periodontology and implant dentistry,” Periodontol 2000, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1111/PRD.12588.

- J. G. Caton et al., “A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions – Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification,” Jun. 01, 2018, Wiley-Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/JPER.18-0157.

- G. N. Belibasakis and D. Manoil, “Microbial Community-Driven Etiopathogenesis of Peri-Implantitis,” Jan. 01, 2021, SAGE Publications Inc. doi: 10.1177/0022034520949851.

- M. Mccann et al., “Staphylococcus epidermidis device-related infections: pathogenesis and clinical management,” Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, vol. 60, no. 12, pp. 1551–1571, Dec. 2008, doi: 10.1211/JPP.60.12.0001.

- G. Charalampakis, Å. Leonhardt, P. Rabe, and G. Dahlén, “Clinical and microbiological characteristics of peri-implantitis cases: A retrospective multicentre study,” Clin Oral Implants Res, vol. 23, no. 9, pp. 1045–1054, Sep. 2012, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02258.x.

- G. Charalampakis and G. N. Belibasakis, “Microbiome of peri-implant infections: Lessons from conventional, molecular and metagenomic analyses,” Feb. 05, 2015, Landes Bioscience. doi: 10.4161/21505594.2014.980661.

- L. J. A. Heitz-Mayfield, F. Heitz, and N. P. Lang, “Implant Disease Risk Assessment IDRA-a tool for preventing peri-implant disease,” Clin Oral Implants Res, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 397–403, Apr. 2020, doi: 10.1111/CLR.13585.

- J. Derks, D. Schaller, J. Håkansson, J. L. Wennström, C. Tomasi, and T. Berglundh, “Peri-implantitis - Onset and pattern of progression,” J Clin Periodontol, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 383–388, Apr. 2016, doi: 10.1111/JCPE.12535.

- L. J. A. Heitz-Mayfield and G. E. Salvi, “Peri-implant mucositis,” J Clin Periodontol, vol. 45, pp. S237–S245, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.1111/JCPE.12953.

| Parameter | Peri-implantitis (n = 58) | Healthy/Mucositis (n = 66) | p-value |

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 60.73 ± 10.54 years | 58.22 ± 10.19 years | 0.225a |

| Sex | Male: 33, Female: 25 | Male: 31, Female: 35 | 0.270b |

| Smoking Status | No: 35, <10 cig/day: 9, >10 cig/day: 17 | No: 44, <10 cig/day: 10, >10 cig/day: 10 | 0.665b |

| Predictor | B | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

| aMMP-8 > 20 ng/mL | 3.260 | 0.006 | 26.06 |

| CAL (per mm) | 4.540 | <0.001 | 93.70 |

| S. epidermidis (copies) | 0.009 | 0.010 | — |

| B = regression coefficient, SE = standard error, OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, CAL = clinical attachment level, aMMP-8 = active-matrix metalloproteinase-8, S. epidermidis = bacterial load by qPCR. All predictors were statistically significant (p < 0.05), indicating independent associations with peri-implantitis risk. OR for S. epidermidis calculated as exp(B); CI not shown due to unavailable SE | |||

| Predictor | β | p-value |

| MMP-8 Gene Expression | 0.322 | 0.003 |

| aMMP-8 > 20 ng/mL | 0.213 | 0.046 |

| Risk Category | n | Peri-Implantitis Cases (n) | % with Peri-Implantitis |

| Low (0–2 points) | 41 | 5 | 12.2% |

| Moderate (3–5 points) | 31 | 18 | 58.1% |

| High (6–7 points) | 23 | 23 | 100.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).