1. Introduction

Anomaly detection is essential in fields such as surveillance, healthcare, finance, and industrial monitoring, where identifying deviations from normal patterns is crucial. In video surveillance, anomalies can include unusual movements, unauthorized access, or unexpected incidents, with context playing a significant role in determining what is considered abnormal, for example, walking on a highway instead of a sidewalk. Since obtaining labeled video data for anomalies is challenging, many existing methods approach anomaly detection as a one-class classification problem, training models only on normal data and identifying anomalies as outliers during testing. However, current techniques face several limitations. Many fail to account for environmental variability, such as changes in lighting, weather conditions, and camera motion. Additionally, dataset limitations can lead to inaccurate representations of real-world anomalies, as certain activities, like cycling or running on a street, may be misclassified. Another major issue is the hu-man-centric focus of existing models, which prioritize detecting human-related anomalies while overlooking non-human anomalies, such as falling objects, fires, or water leaks. Furthermore, most datasets capture different camera angles within the same scenario but lack coverage of multiple distinct scenarios, reducing a model’s ability to generalize effectively.

To address these challenges, the Multi-Scenario Anomaly Detection (MSAD) dataset [

27] was used. This dataset includes high-resolution video recordings from 14 different scenarios, each captured from multiple camera perspectives. It incorporates a wide range of normal activities along with variations in lighting and weather conditions, ensuring better generalization across diverse environments. In addition to the dataset, this study introduces Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) [

4] as a novel approach to anomaly detection. Meta-learning, or "learning to learn," enables models to quickly adapt to new tasks with minimal data, which is particularly valuable when large-scale data collection is impractical. The meta-learning process consists of two phases: the meta-training phase, where the model is exposed to various tasks (i.e., different scenarios in the MSAD dataset) to develop a meta-model capable of adapting to new tasks, and the meta-testing phase, where the model is evaluated on previously unseen tasks to assess its ability to generalize.

This meta-learning approach offers several advantages for anomaly detection. It allows models to rapidly adapt to new environments with minimal data, improving their ability to function in dynamic settings. Training in diverse tasks enhances the model’s ability to generalize, making it more effective in identifying anomalies in unfamiliar scenarios. Additionally, meta-learning increases efficiency by leveraging small amounts of anomalous data, addressing the common issue of data scarcity. Applying MAML to the MSAD dataset enables the model to handle new viewpoints by learning from multiple camera perspectives within the same scenario. It also demonstrates strong generalization capabilities when applied to entirely new scenarios, proving its effectiveness in real-world applications. This approach significantly strengthens anomaly detection in dynamic and evolving environments, making it a promising solution for improving security and monitoring systems.

Previous studies on anomaly detection across multiple scenarios have faced significant challenges in generalization. Traditional models struggle to adapt to different scenarios and viewpoints, and while few-shot learning (FSL) [

26] methods have been introduced to address this issue, they remain limited to specific environments and fail to generalize effectively. To overcome these limitations, a Meta-Learning Framework, particularly Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML), can be employed. MAML optimizes model parameters to enable rapid adaptation to new tasks with only a few examples through minimal gradient updates.

The main contribution of this paper can be summarized as follows:

MAML technique is designed to enable anomaly detection in 14 different scenarios including highway, shop, front door, office, parking lot, pedestrian street, street Highview, warehouse, road, park, mall, train, restaurant, sidewalk by using small number of normal and anomalous data, where data collection is limited.

Our method leverages metadata and swin transformers to extract spatial features from frames of video data from different targeted scenes, thereby enhancing adaptability to different scenarios.

By leveraging anomaly detector models using MAML to acquire the capability to classify between normal and abnormal data, better accuracy in anomaly detection from different scenarios with limited data is realized from targeted domain.

2. Related Works

Over the years, several counter measures have been proposed to detect anomaly for video surveillance in different sectors like education, manufacturing, road etc. Santoro et al., 2016 [

19] focused on meta-learning techniques that address this by enabling models to learn from prior tasks and adapt quickly to new ones. Memory-Augmented Neural Networks (MANNs), especially Neural Turing Machines, provided external memory mechanisms that support rapid learning from a few examples. They also demonstrated that MANNs outperform LSTMs in both classification and regression tasks, showing strong potential for efficient, flexible meta-learning.

Finn, Abbeel et al., 2017 [

4] concluded that MAML is a powerful and versatile me-ta-learning approach that allows models to adapt quickly to new tasks with minimal data. Its model-agnostic nature makes it applicable across various domains and tasks, ad-dressing key limitations of traditional machine learning methods in dynamic environments. The study demonstrates that MAML significantly enhances few-shot learning capabilities in both supervised and reinforcement learning contexts. Ravi et al., 2017 [

17] studied and introduces an LSTM-based meta-learner that learns an optimization strategy tailored for few-shot scenarios by updating a learner model’s parameters efficiently.

Munkhdalai et al., 2017 [

13] introduced Meta Networks (MetaNet), a novel meta-learning framework designed to enhance rapid generalization and continual learning in neural networks, particularly in scenarios with limited labeled data. It built on previous meta-learning approaches that emphasize two-level learning, where a meta-learner acquired knowledge across tasks to improve a base learner's performance on new tasks.

Similarly, gong et al., 2019 [

5] studied reconstruction-based techniques, such as those employing Auto-Encoder methods exclusively train on normal videos and subsequently test on both normal and abnormal videos. Soh and Cho et al., 2020 [

21] published a paper that introduces a meta-transfer learning framework that could be adapted for anomaly detection tasks. The method aims to learn a meta-learner that can transfer knowledge from related tasks to new tasks with limited labeled data. By leveraging meta-transfer learning, the model can adapt to new anomaly detection tasks with minimal supervision, potentially improving detection performance.

Zhang et al., 2020 [

25] proposed a novel few-shot learning framework leveraging Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) which was proposed for bearing anomaly detection. The framework aimed to develop a robust fault classifier with minimal data by adapting quickly to new fault conditions. In a case study involving the introduction of new artificial faults, the method achieved up to 25 percent overall accuracy compared to a Siamese network benchmark. Moreover, when sufficient training data from artificial damages was available, MAML demonstrated competitive generalization abilities compared to state-of-the-art few-shot learning methods in identifying realistic bearing damages.

Smith et al., 2020 [

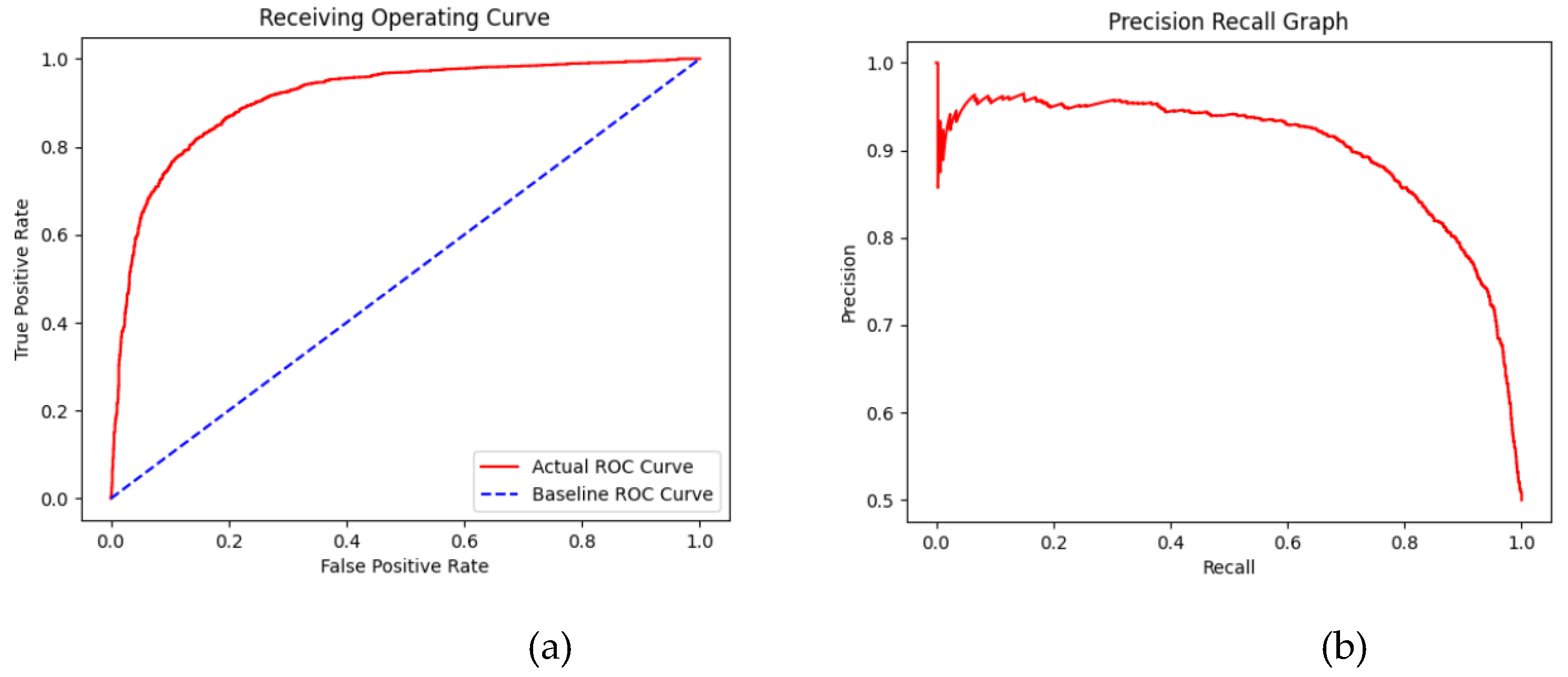

20] addressed the limitations of traditional anomaly detection methods in cybersecurity, emphasizing the potential of meta-learning to enhance detection accuracy and adaptability with limited data. Diverse cyber security datasets were collected. Preprocessing involved normalization, feature extraction, and dimensionality re-duction. Meta-Learning Framework utilized Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) to train models on various anomaly detection tasks. Evaluation Metrics assessed using precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC, compared to baseline models. Meta-learning outperformed traditional models, especially with limited data. Demonstrated robust performance on new, unseen data shows the adaptability of the system. Initial training was resource-intensive, but adaptation to new tasks was efficient.

Bergman et al., 2020 [

1] presented a novel approach to anomaly detection through a classification-based method called GOAD, which addressed the limitations of existing techniques by utilizing a semi-supervised learning framework. It was built on previous works that categorize anomaly detection methods into reconstruction, distributional, and classification-based approaches, highlighting the effectiveness of deep learning in this domain.

Chen et al., 2021 [

2] studied anomaly detection as a one-class classification problem, relying on the features of normal events where Generative adversarial network aims to re-construct normal events to minimize the reconstruction loss. Wu et al., 2021 [

22] introduced an unsupervised transformer-based framework, Meta Former, for anomaly detection without relying on labeled data. The model leverages self-attention mechanisms to learn generalized representations from normal patterns, enabling it to detect anomalies across diverse domains. Meta Former captures both local and global contextual features, enhancing its ability to handle complex data distributions.

Reiss et al., 2022 [

18] studied and experimented with anomaly detection methods which were often thought to struggle with understanding normal events, some models can effectively detect anomalies. However, achieving a good reconstruction isn't a guarantee of effective anomaly detection. These methods can be sensitive to object speeds, leading them to misclassify sudden motions as anomalies. Thus, a nuanced understanding of model behavior is necessary to improve anomaly detection accuracy. Natha et al., 2022 [

14] conducted a systematic review of anomaly detection methods utilizing machine learning and deep learning techniques across various domains. The study categorizes approaches based on supervised, unsupervised, and semi-supervised learning, highlighting their strengths, limitations, and application areas. Meng et al., 2023 [

11] proposed an explainable few-shot learning framework for online anomaly detection in ultrasonic metal welding processes with varying configurations. Their approach combines prototype-based learning with interpretability techniques to enable accurate detection and transparent decision-making using limited labeled data. The model effectively adapts to different welding setups, addressing data scarcity and variability challenges. Moon et al., 2023 [

12] proposed an anomaly detection method using a model-agnostic meta-learning-based variational autoencoder (MAVAE) tailored for facility management systems. This approach enables rapid adaptation to new environments using few-shot learning by leveraging MAML to fine-tune VAE parameters with limited normal data.

Joshi et al., 2023 [

8] focused on the head pose estimation techniques in this paper named "One, Five, and Ten-Shot-Based Meta-Learning for Computationally Efficient Head Pose Estimation". It compares MAML and FO-MAML methods for efficiency. FO-MAML uses first-order approximation, avoiding Hessian computation. Experiments were conducted in one-shot, five-shot, and ten-shot settings. FO-MAML shows faster optimization than traditional MAML. Navarro et al., 2023 [

15] introduced Hydra, a meta-learning framework designed for fast model recommendation in unsupervised multivariate time series anomaly detection. Their approach leverages a small set of meta-features to match datasets with suitable detection models, addressing the challenges of scalability and generalization. Li et al., 2023 [

9] proposed a novel zero-shot anomaly detection method leveraging batch normalization statistics to detect anomalies without requiring training data from the target distribution. Their approach models the distribution of batch normalization parameters across diverse tasks, enabling effective generalization to unseen domains.

Duan et al., 2024 [

3] introduced a meta-learning framework for efficient anomaly diagnosis in few-shot AIOps scenarios, addressing the challenges of limited labeled data in IT operations. Their approach leverages Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) to enable fast adaptation to new fault types with minimal training samples. Wu et al., 2024 [

23] provided a comprehensive review of deep learning techniques for video anomaly detection, highlighting advancements across supervised, unsupervised, and self-supervised methods. The paper categorizes key approaches based on learning paradigms, feature representations, and anomaly scoring techniques. Zhang et al., 2024 proposed ADAGENT, a novel anomaly detection framework that leverages multimodal large models to operate effectively in adverse and complex environments. By integrating visual, textual, and contextual data, ADAGENT enhances anomaly detection robustness under challenging conditions such as low visibility or sensor noise.

Zhu, Raj et al., 2024 [

26] developed a SAAD (Scenario Adaptive Anomaly Detection) model that takes a unique approach, utilizing a few-shot learning framework for faster adaptation to novel concepts and scenarios. This adaptability, coupled with its competitive performance on diverse scenarios, sets SAAD apart from traditional models. Jeong et al., 2024 [

6] presented a novel approach for detecting pipeline leaks using limited normal data, particularly in hazardous environments like power plants. The authors proposed the GAD-PN framework, combining Cycle GAN for generating synthetic anomaly data and Prototypical Networks for anomaly classification based on few-shot learning.

Zhu, Wang et al., 2024 [

27] published the paper "Advancing Video Anomaly Detection: A Concise Review and a New Dataset" proposes a novel approach to anomaly detection using the Scenario-Adaptive Anomaly Detection (SA2D) model. This model is designed to address limitations in existing few-shot learning frameworks by enhancing adaptability to multiple scenarios and viewpoints. Unlike traditional methods, SA2D utilizes a meta-learning framework to efficiently adapt to unseen contexts, making it suitable for diverse and dynamic environments. The authors introduce the Multi-Scenario Anomaly Detection (MSAD) dataset, which includes a variety of indoor and outdoor settings, dynamic environments, and multiple camera angles, improving upon the limitations of existing datasets like UCSD Ped1/Ped2 and ShanghaiTech. This dataset adopts frame-level annotations to ensure precise anomaly detection. The SA2D model employs future frame prediction for anomaly detection, supported by backbone architectures like U-Net and ConvLSTM for temporal modeling. It incorporates a generative adversarial network (GAN) for video frame reconstruction, demonstrating strong adaptability and competitive performance across challenging tasks. The paper highlights the importance of scenario diversity and meta-learning in advancing anomaly detection methodologies and datasets

In contrast to existing methods, meta learning framework can be utilized in models to adapt to multiple scenarios even new scenario with more accuracy. It includes MAML (Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning) that trains a model's parameters in such a way that a small number of gradient updates can quickly adapt to a new task with few examples. This approach is versatile and can be applied to various domains including image classification, regression, and reinforcement learning.

3. Methodology

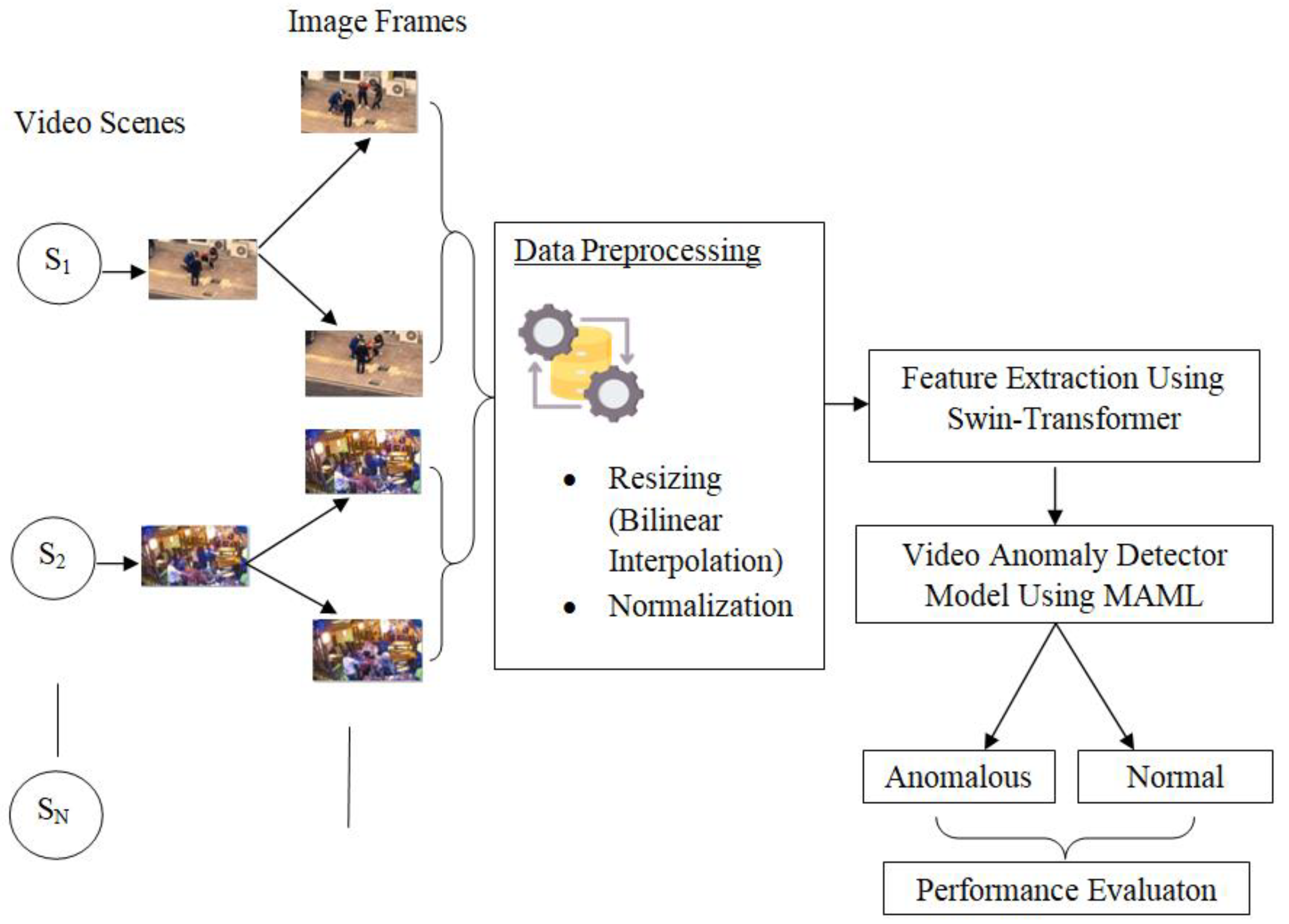

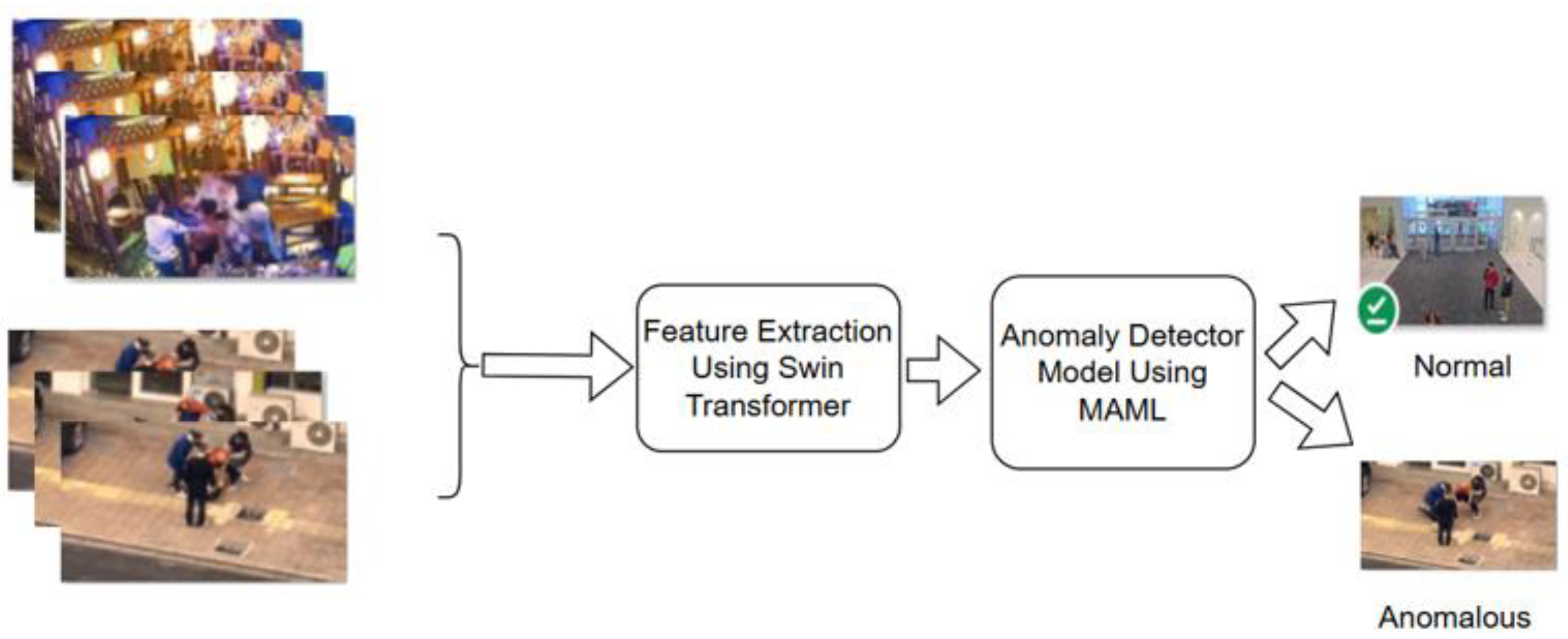

The methodology starts with data collection. The system model for video anomaly detection using model agnostic meta learning from video surveillance is illustrated in

Figure 1, where Frames were extracted and then preprocessed. After preprocessing, feature extraction was done using swin transformer. And the extracted features as feature maps were fed to the anomaly detector model that uses MAML to classify the dataset into normal and anomalous.

3.1. Dataset

MSAD (Multi Scenario Anomaly Detection) [

1] datasets containing anomalies and normal instances have been collected. MSAD dataset has anomaly videos, normal testing and normal training datasets in video form. Dataset also contains annotated csv files that contain frame numbers. In csv file dataset has range values in column from where anomalies have been started. The MSAD dataset, along with any new datasets, serves as input to the system. Here, each dataset represents a different task.

A collection of 720 video datasets has been compiled, categorized as follows: anomaly videos, normal testing videos, and normal training videos. The anomaly video dataset comprises 240 videos, encompassing 11 distinct anomaly types across 13 different scenarios, excluding highway scenes. The normal testing video set includes a total of 120 videos. Finally, the normal training video dataset contains 360 videos, covering 14 different scenarios, including highway scenes.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Raw data from MSAD dataset undergoes preprocessing to ensure data quality and consistency. This involves video frame resizing using bilinear interpolation method and Normalization using mean and standard deviation. Here Bilinear interpolation for y (height) and x (width) with four coordinate points

A(y

1 ,x

1),

B(y

1 ,x

2),

C(y

2 , x

1) and

D(y

2 , x

2) includes formula for computation for X and Y for width dimension is given by:

Then linear interpolation between the two interpolated values

X and

Y in the height dimension is given by:

where,

Using the above equations, images were resized to required dimension i.e. 224×224 RGB image. Here PIL image with [H × W × C] in range [0,255] with unsigned int type were converted to Tensor of float type with shape [C × H × W] in the range [0,1]. In this case, PIL images belong to RGB mode. The normalization of resized images was done to standardize the images based on their mean and standard deviation, ensuring stable and consistent model performance.

For this study, the dataset was initially partitioned into training, validation, and testing sets based on different scenarios. For the initial training phase of the model, nine distinct scenarios were utilized, encompassing shop, front door, office, parking lot, pedestrian street, street Highview, warehouse, road, and park, each containing both anomalous and normal video data. Two different scenarios, mall and train, which also included both anomalous and normal videos, were allocated for the initial validation of the model. Finally, the initial testing of the model employed data from two separate scenarios: restaurant and sidewalk, both containing anomalous and normal video examples.

3.3. Data Preprocessing

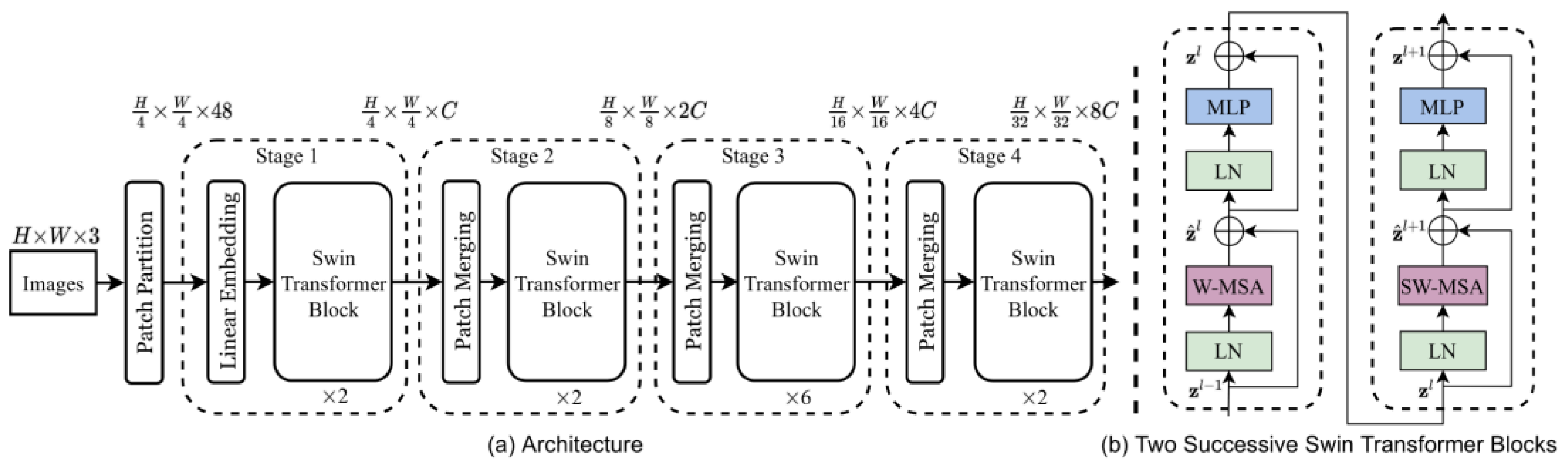

For video frames (Image Input) of size 224 × 224 with 3 channels, the Swin Trans-former [

10] was used to extract feature vectors from the preprocessed data of the MSAD dataset which is illustrated in

Figure 2.

Here swin transformers were used for leveraging their hierarchical attention mechanism to capture both local and global spatial patterns. During the forward pass, the model processes the input images, and feature maps were extracted from intermediate layers, providing rich representations for anomaly detection. Mathematical interpretation, for input image I, the feature extraction process using Swin-S can be described as:

where,

I is the input image of size 224×224×3 and F is the feature vector whose output feature shape is 768 dimensional vectors (feature vectors). In patch embeddings, the image

I is divided into patches of size 4×4 and each patch is embedded into a patch token

T as

where,

WEis learnable embedding weight and b

E is bias. Then for hierarchical feature representation, swin transformer applies Shifted Windows Multi-Head Self Attention (SW-MSA) in hierarchical stages using:

where,

F(l) is the feature map at layer l and SW-MSA is the shifted window-based multi-head self- attention. Then feature extraction at final layer was done where final feature representation F can be taken from the last stage of the Swin Transformer using:

where, L is the last layer, and the pooling operation reduces spatial dimensions to a feature vector.

Finally, using input image 224×224×3 was given to swin transformer and 768 dimensional vectors as feature vectors were obtained and these embeddings were then served as inputs to the anomaly detector model, allowing for effective anomaly detection.

3.4. Data Preprocessing

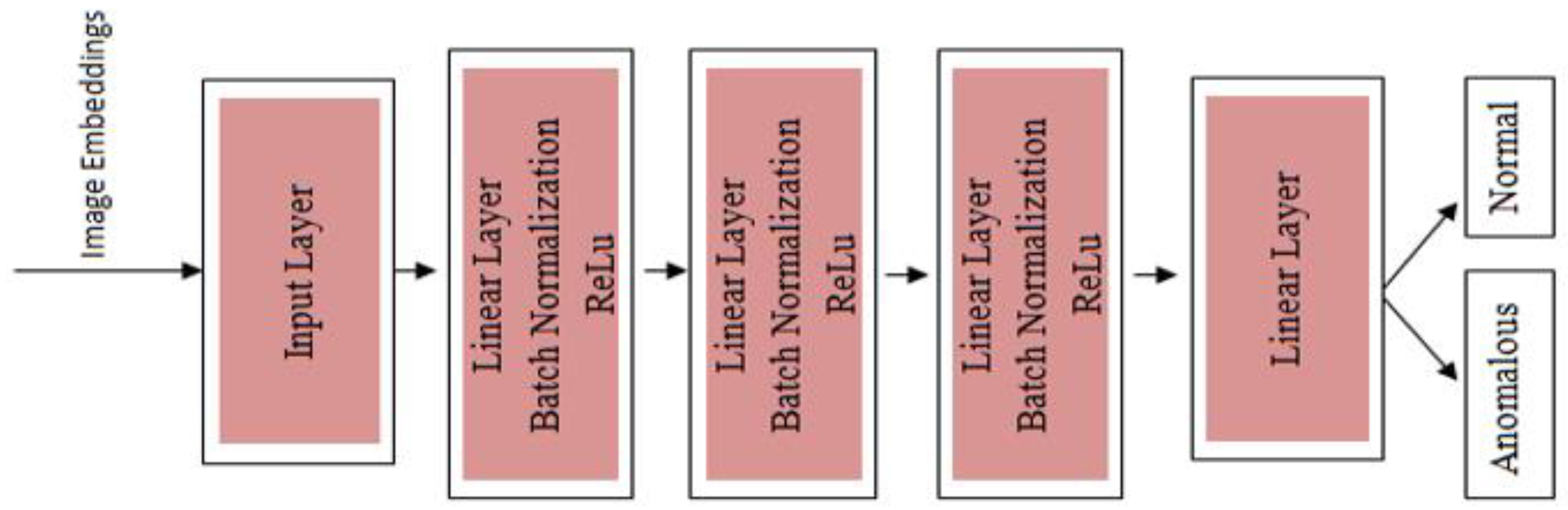

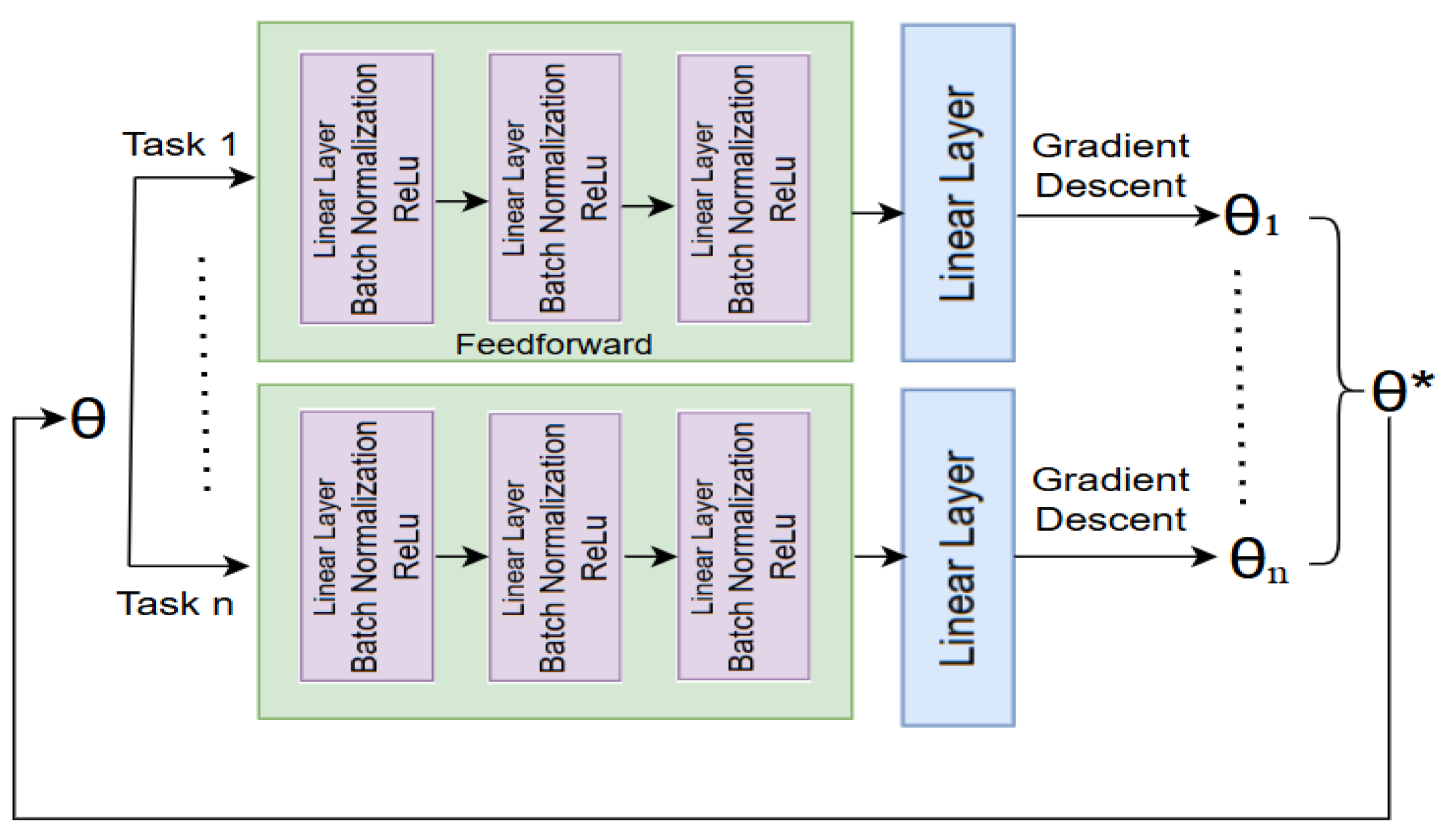

In this phase, the architecture represents a feedforward neural network designed for anomaly detection using image embeddings as input. The model begins with an input layer that processes these embeddings, which are typically extracted from swin model.

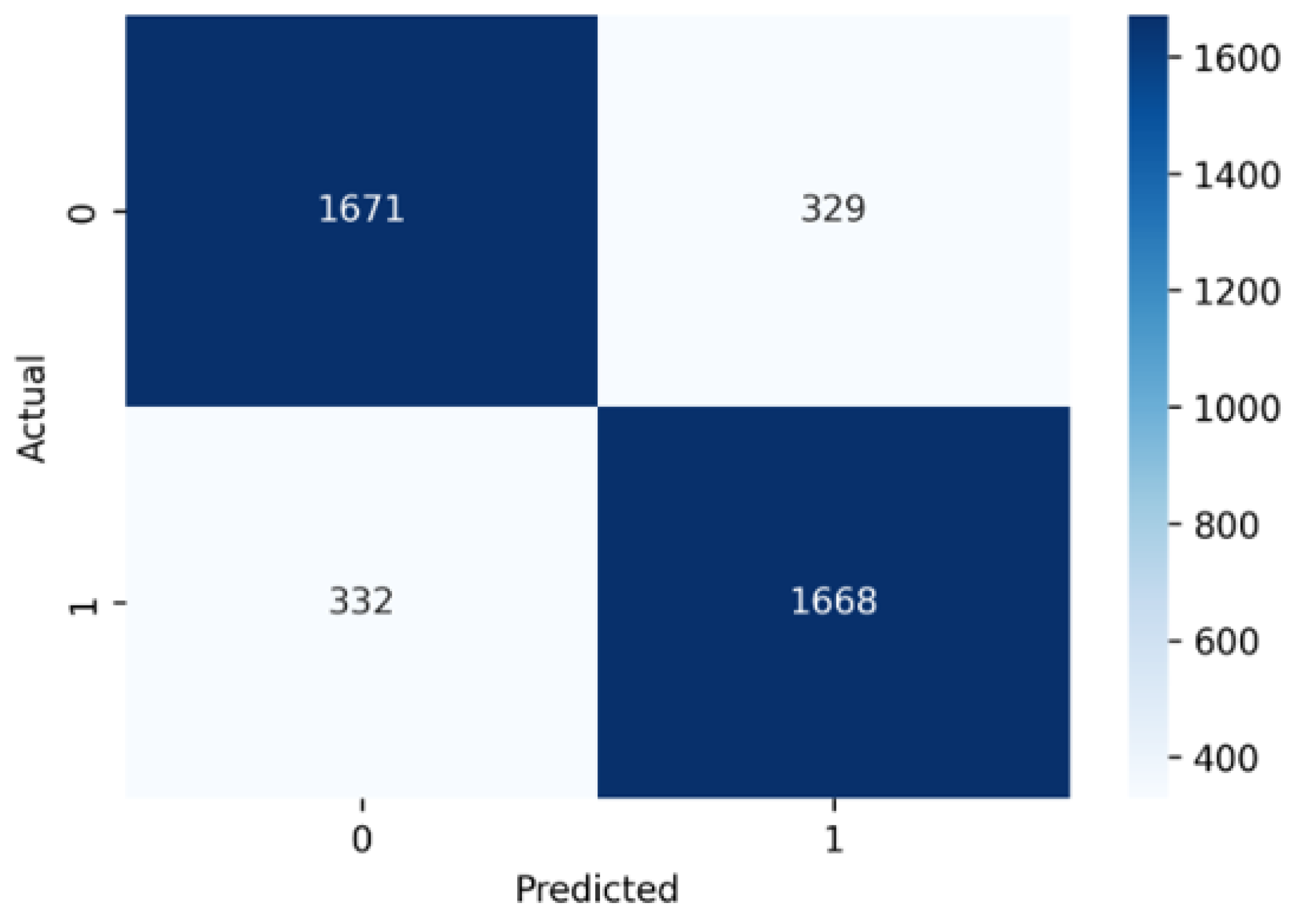

Figure 3 shows layered architecture where input is image embeddings (dimensional vectors) given to input layer. The Anomaly Detector class takes image embeddings as input, with a default feature size of 1024. The model consists of three sequential layers, each containing a fully connected (Linear) layer, batch normalization (BatchNorm1d), and a ReLU activation function to introduce non-linearity. The first layer reduces the input dimension from 1024 to 512, followed by a second layer that maintains the dimension at 512, and a third layer that reduces it further to 256. The final output layer is a linear trans-formation that maps the 256-dimensional feature representation to a single scalar logit. The forward method processes an input tensor through these layers sequentially, producing an output of shape, where each sample gets a single logit value. This output is used for binary classification, where we can get a probability for determining whether an input is normal or anomalous.

3.4.1. Meta Training on Dataset

The meta training process in meta-learning consists of several key steps designed to help a model learn how to quickly adapt to new tasks (Image Embeddings) with limited data and a meta learning approach is illustrated in

Figure 4.

Task Sampling: The sample task method was designed to generate a dataset sample for anomaly detection task. Here a random scenario from a predefined list was selected. Within that scenario, it identified normal and anomalous images by cross-referencing scenario-specific indices with label-specific indices. Once these images were identified, it randomly selected a fixed number (k_shot + k_query) of normal and anomalous samples. These selected images were then split into two sets: the support set, which consists of k_shot normal and k_shot anomalous images for training, and the query set, which contains k_query normal and k_query anomalous images for evaluation. Each image was assigned to its respective label, either normal or anomalous. To avoid bias, the method shuffled both the support and query sets before returning them. Then the function ultimately ensured a balanced, structured dataset that can be used in meta-learning tasks, particularly for detecting anomalies within specific scenarios.

Inner Loop: The method began by creating a temporary copy of the model to ensure that updates do not affect the original model. The copied model was then placed in training mode, and a Binary Cross Entropy with Logits Loss function was defined for classification. Then a series of inner-loop updates were performed over self-inner steps iterations. In each iteration, it made predictions using the support set, calculated the loss, and computed gradients with respect to the model’s parameters. Instead of using an optimizer, it manually updated each parameter using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) by subtracting the gradient scaled by the inner learning rate. This adapted model, then fine-tuned to the support set, was returned. The purpose of this method was to allow a model to quickly adapt to a new task using only a few examples. This approach maintains the computational graph so that the outer update can backpropagate through the inner adaptation steps.

Outer Loop: The meta update function implements a meta-learning step based on the Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) approach. It processed multiple tasks, where each task consists of a support set (used for inner-loop adaptation) and a query set (used for evaluation). First, it initialized the loss function, optimizer, and storage variables for query labels and predictions. Then, it iterated over tasks, moving data to the appropriate device and performing an inner-loop update, where the model adapts to the task using the support set. After adaptation, the model made predictions on the query set, and the binary cross-entropy loss was computed. The predicted probabilities and true query labels were stored for later analysis. The total meta-loss was averaged across tasks, and outer-loop optimization was performed by backpropagating the loss. Finally, the main model’s weights were updated using the adapted model, and the function returned the final loss along with stored query labels and predictions. This process helped the model learn a generalizable initialization that can quickly adapt to new tasks with minimal updates.

Meta Validate: A meta-learning model was then evaluated by iterating over a set of tasks, each containing a support set for fine-tuning and a query set for evaluation. It first initialized the total loss and prepared storage for true labels and predictions. As it looped through tasks, it moves data to the appropriate device (CPU/GPU) and fi-ne-tuned a copy of the model on the support set using an inner-loop update function (inner update). After adaptation, it made predictions on the query set, applied a sigmoid activation function to convert logits into probabilities, and stored both true and predicted labels. Then the function computed the binary cross-entropy loss for each task, accumulated the losses, and then averaged them over all tasks. Finally, it invoked an early stop-ping mechanism, which can determine if the model should be saved or training should halt based on the meta-loss trend. Then the function returned the averaged loss, true query labels, predicted labels, and the early stopping decision, ensuring model evaluation in a meta-learning framework.

3.4.2. Meta Testing on Dataset

A new dataset, which the model has not seen during the meta-training phase, was prepared. This dataset contains new tasks from two different scenarios (restaurant and sidewalk) that the model needs to adapt to. Then, like the meta-training phase, tasks were sampled from the novel dataset. Each task was defined with a small number of training examples (support set) and testing examples (query set).

For each sampled task, the model adapted its parameters using the support set. This was usually done using the same adaptation procedure (inner loop) as in the meta-training phase. The key difference here was that the initial model parameters or meta-parameters, obtained from meta-training, were used as the starting point. After adaptation, the model was evaluated on the query set of the same task. The performance was recorded to assess how well the model had adapted to the new task.

3.5. Data Preprocessing

In the context of video anomaly detection, each task Ti corresponds to a different set of video frames, representing a unique scenario or environment. The collection of all such tasks is denoted by T = {T1, T2, …, Tn}. For each task Ti, there exists a dedicated dataset Di={(xj,yj)}mi for j=1, where xj is the input and yj is the corresponding level. The model was used for anomaly detection is parameterized by θ, which represents the set of all learnable parameters. During meta-training, the goal is to find an optimal initialization of θ such that, after a few gradient updates using data from any task Ti, the model quickly adapts and performs well.

3.5.1. Dataset Meta Training Phase

The meta training phase aims to find an initial set of model parameters, denoted as

θ, that can rapidly adapt to new tasks. Within this phase, the inner loop involves task-specific adaptation: for each task

Tᵢ, the model performs a few steps of gradient descent to adapt the initial parameters

θ, resulting in task-specific parameters

θ′ᵢ.

where α is the learning rate and

LTi(θ) is the loss function for task

Tᵢ.

Following this, the outer loop performs a meta-update by adjusting the initial parameters

θ based on the performance of the adapted parameters

θ′ᵢ across all tasks, enabling better generalization to unseen tasks.

where, β is meta learning rate.

3.5.2. Meta Testing Phase

During the meta testing phase, the learned initial parameters

θ are fine-tuned on a new dataset corresponding to a previously unseen task using a few gradient descent steps. Given a new task

Tnew with its dataset

Dnew, the model adapts its parameters according to the following update equation:

where, α is the learning rate and

LTnew(

θ) represents the loss on the new task. This adaptation allows the model to quickly generalize new tasks using minimal training data.

3.5.3. Loss Function for Anomaly Detection

For anomaly detection, the loss function

Lₜ

ᵢ(

θ) can be designed based on either reconstruction error or the output of a discriminator. In a reconstruction-based approach, the loss function measures how well the model can reconstruct the input data and, it can be defined as:

where

fθ(

x) is the reconstructed output of the model. This formulation penalizes large deviations between the input x and its reconstruction, thereby helping the model learn normal patterns and identify anomalies as instances with high reconstruction errors.

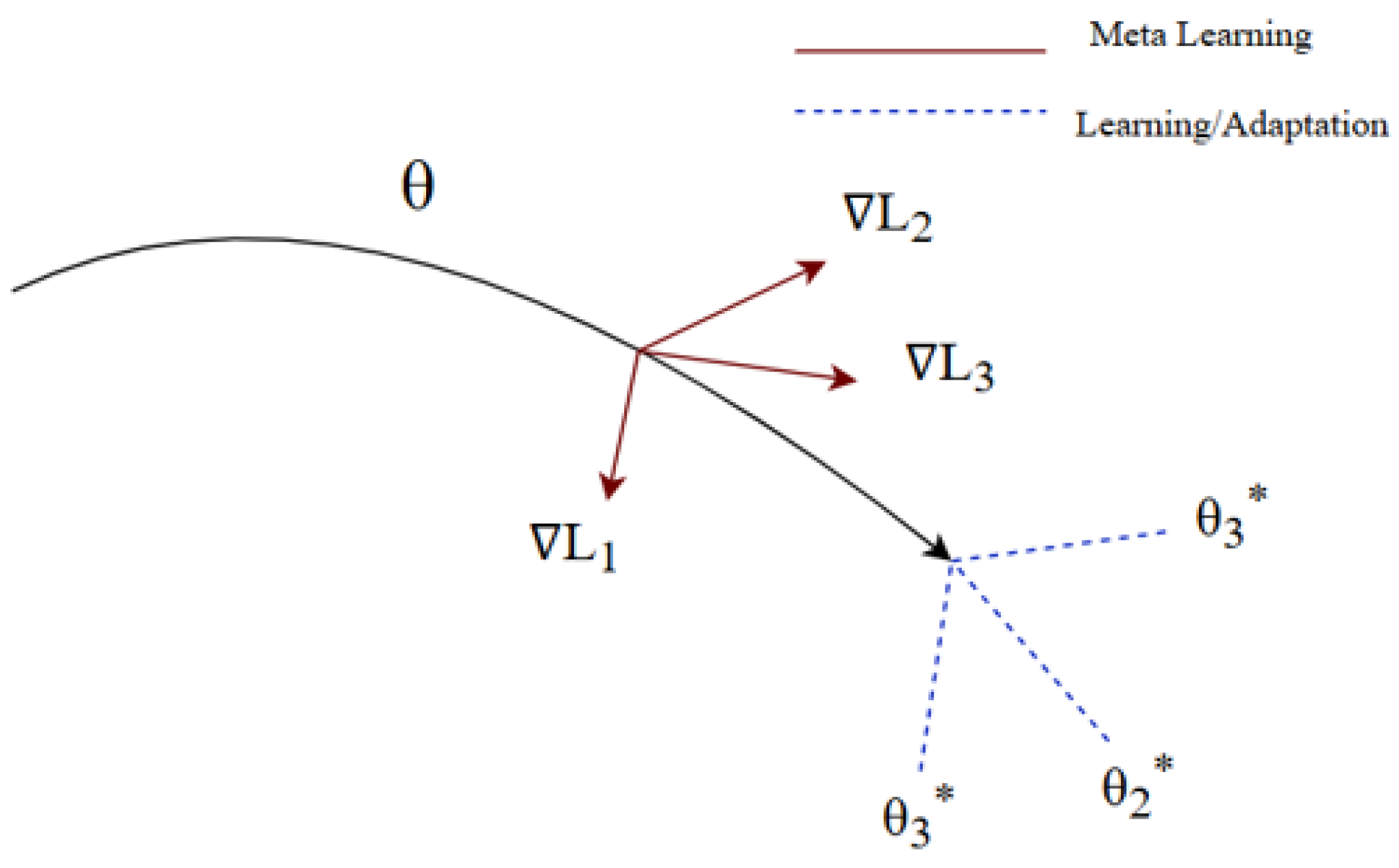

3.5.4. Model Agnostic Meta Learning Architecture

This figure 5 illustrates the core concept of Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML), where the objective is to find an optimal set of initial parameters θ that can quickly adapt to a variety of tasks with minimal training. The solid curve represents the trajectory of meta-learning, which optimizes the initial parameters across multiple tasks. Each red arrow (∇L₁, ∇L₂, ∇L₃) indicates the task-specific gradient computed during the inner loop of training for different tasks. These gradients guide the adaptation of the initial parameters θ toward task-specific optima (θ₁*, θ₂*, θ₃*), shown as blue dashed arrows labeled as "Learning/Adaptation." The goal of MAML is to optimize θ such that a small number of gradient steps can lead to effective task-specific models, enabling rapid learning on new tasks. The figure highlights how meta-learning integrates feedback from multiple tasks to update the shared initialization in a way that supports efficient fine-tuning.

Figure 5.

The architecture of MAML.

Figure 5.

The architecture of MAML.

To implement the meta-learning approach in a task-agnostic manner, the following algorithm outlines the Generic Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) procedure. This algorithm is designed to optimize an initial model that can quickly adapt to new video frame-based anomaly detection tasks with only a few gradient steps. The steps below detail the inner and outer learning loops required to achieve this fast adaptation:

Algorithm: Generic Model Agnostic Meta learning algorithm

Require: D(T): Distribution over tasks (Video frames)

Require: α and β: step size hyperparameters

Step1. Randomly initialize parameter θ

Step2. While not done do

Step3. Sample batch of task Ti ∼ D(T)

Step4. For all Ti do

Step5. Evaluate ∇θ LTi(fθ) with respect to k samples

Step6. Calculate adapted parameters using gradient descent:

θ’i = θ - α∇ θ LTi(fθ)

Step7. end for

Step8. Update θ ← θ − β∇θ∑Ti∼D(T) LTi(f ‘θ)

Step9. end while

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.S., D.R.P. and G.G.; methodology, B. S., D.K.S. and D.R.P.; software, D.K.S.; validation, D.R.P, G.G. and B.S.; formal analysis, D.K.S.; investigation, D.K.S.; resources, D.K.S.; data curation, D.K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.S. and G.G.; writing—review and editing, D.K.S., G.G. and B.S.; visualization, D.K.S. and D.R.P.; supervision, D.R.P.; project administration, B.S., D.R.P,. and G.G.; funding acquisition, G.G. and B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.