1. Introduction

Token graphs were introduced by [

1] et al. as a framework to model the movement of objects or entities across graph vertices following specific rules, such as in graph pebbling. These graphs have since garnered significant attention due to their ability to preserve and analyze structural properties.

Given a graph with , let be a natural number and denote the collection of all k-subsets of . The k-token graph has as its vertex set. Two distinct vertices are adjacent if and only if , where (i.e., their symmetric difference is an edge in G).

Recent studies have concentrated on the properties of token graphs. In 2023, Ju Zhang et al. [

2] explored the automorphisms in 2-token graphs, while in 2022, [

3] examined their edge-transitive properties. Earlier, in 2020, [

4] investigated the structural characteristics of 2-token graphs. More recently, in 2023, [

5] analyzed 2-token graphs in the context of disjoint union graphs, contributing to a deeper understanding of this evolving field.

While 2-token graphs are well-studied, 3-token graphs remain relatively unexplored, offering opportunities to address significant gaps in graph theory. This research investigates the properties of 3-token graphs derived from path graphs and disjoint unions. By extending the foundational work on 2-token graphs, this study introduces new frameworks to analyze vertex degree patterns, structural relationships, and graph invariants such as chromatic number, clique number, and independence number.

Moreover, this research demonstrates isomorphisms between 3-token graphs and specific graph classes like the cubical staircase graph, uncovering structural relationships across graph families. These insights have practical implications for network flow analysis, resource allocation, and dynamic system modeling.

By solving open problems and proposing new conjectures, this study advances the theoretical understanding of token graphs and lays a foundation for exploring k-token graphs of cycle graphs, and more complex graphs. This contribution is vital for applying graph theory to real-world challenges.

All graphs in this paper are considerd to be finite, simple and undirected. We refer the reader to [

6] for general background on graph theory and for all undefined notions used in the text. For any graph

G, the vertex set and the edge set will be simultaneously symbolized by

and

. Recall that two graphs

G and

H are isomorphic if there exists a bijective function

such that

if and only if

. This function

is called an isomorphism, and the graphs are denoted as

. In graph theory, several fundamental parameters are used to describe a graph’s structure. The degree of a vertex

, denoted by

, is the number of vertices adjacent to

x. The distance between two vertices

u and

v, denoted by

, represents the length of the shortest path connecting them. The diameter of a graph,

, is defined as the longest shortest path in the graph, expressed as

. The clique number,

, is the size of the largest complete subgraph, while the independence number,

, measures the maximum size of a set of vertices where no two are adjacent. The chromatic number,

, is the minimum number of colors needed to color the graph such that no two adjacent vertices share the same color. The dominating number,

, is the minimum size of a vertex set

S such that every vertex not in

S is adjacent to at least one vertex in

S. The edge independence number,

, is the maximum size of a matching, where no two edges share a common vertex. These parameters collectively provide a comprehensive understanding of a graph’s structural properties. These parameters offer a comprehensive description of a graph’s structural properties.

2. Results

The degrees of vertices in

k-token graphs are not yet fully understood in general, leaving this as an open area of research. In [

4], the authors introduced a vertex degree theorem specifically addressing the 2-token graphs of a given graph, providing valuable insights into their structure. Expanding upon this foundational work, we aim to further explore the properties of token graphs by proposing a vertex degree theorem tailored to 3-token graphs. This extension seeks to offer a deeper understanding of the degree patterns in these more complex graphs and contribute to the broader study of token graph theory.

Theorem 1.

Let . For any we have

Proof. Let , we consider four cases.

-

For

Let be adjacent to . If then with . We have . Since then A has possibilities. Similarly, if , then A has possibilities and if , then A has possibilities. For case , we have .

-

For , WLOG assume that .

Let be adjacent to . For necessarily for some and . Since and we have . The A might have different forms. Similarly, if , then A has possibilities. If then for some , we get . The A might have different forms. For the case , we have .

-

For , WLOG assume that .

Let be adjacent to . For necessarily for some and , . Since and and also we have . The A might have different forms. For necessarily for some and . Since and we have . The A might have different forms. Similarly, if then A has possibilities. For this case, we have .

-

For .

Let be adjacent to . For necessarily with and , . Since and and also we have . The A might have different forms. Similarly, if and respectively A has and possibilities. For this case we had .

□

We now provide a detailed description of the 3-token graph constructed from two copies of a path graph. From this, we will gain insights into the structure of the 3-token graph of the disjoint union of two arbitrary graphs.

Lemma 1.

Given two path graphs and , with . Let . It follows that

Proof. According to the definition of the 3-token graph, we have

Let

and

. We make a partition

on

, where

It is clear that and are subgraphs of , so that is subgraph of . Now we will show that each two vertices in or in are not connected by any single vertex in . We know that and . Clearly, for any and for any , it follows that . Therefore , implying . For any and for any , we consider the following cases.

- (i)

-

Case .

Let with , we obtain . Therefore , and thus

- (ii)

-

Case .

Let with . If , then . If , then we have with . As , we get .

For any and for any , we get .

Now, let and with .

- (i)

If ( or ) and ( or ), we get where and . Hence .

- (ii)

If ( and ) or ( and ), obviously , so that .

Now, consider the subgraphs of induced by and . Firstly, let with . Let and with . Clearly, and . We will consider some cases:

- 1.

If and and , then . Thus, if and only if .

- 2.

If and and , then . Thus, if and only if .

- 3.

If and and , then . Thus, if and only if .

- 4.

If and and , then . Thus, if and only if .

- 5.

If and and , then clearly , so

- 6.

If and , then . Thus, if and only if .

- 7.

If and and , then clearly , so that

- 8.

If and and , then clearly , so

- 9.

If and and , then clearly , so .

From these cases, for any

we have that

if and only if either

which implies

or

which implies

.

Now, construct a mapping by , for any . It is easy to see that f is bijective. Moreover, by this correspondence we have that the subgraph induced by in is isomorphic to .

For the case with , the proof is similar to the case with .

□

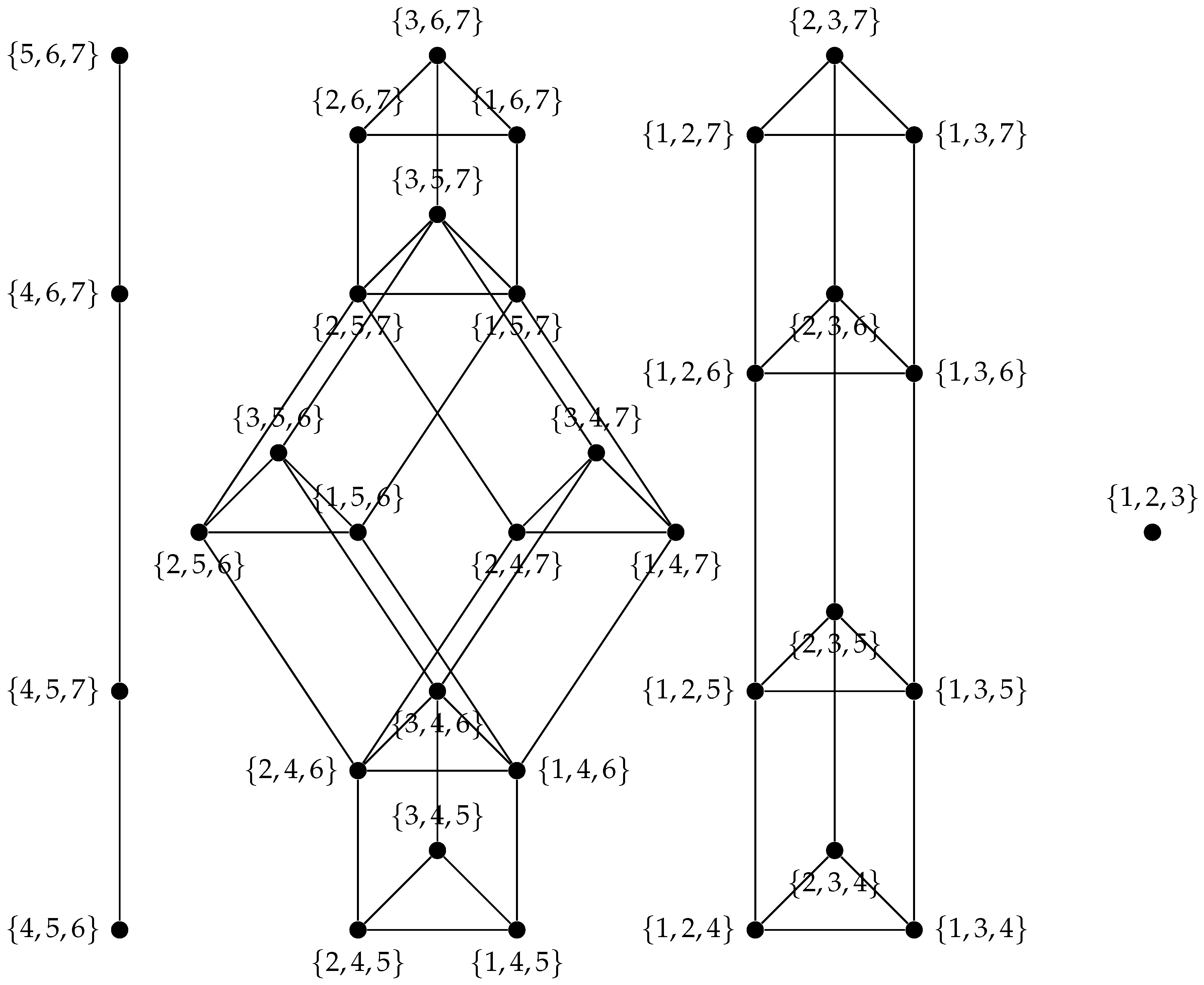

By Lemma 1, for

, the 3-token graph of

can be seen in

Figure 1.

By examining Lemma 1, which establishes that

we derive the following theorem, which provides a general characterization of the structure of the 3-token graph for any graph consisting of two components.

Theorem 2.

For any two graphs G and H, it follows that

Proof. By definition of the 3-token graph of G, we have

Let

and

. We again form a partition

on

, where

It is clear that and are subgraphs of , so that is a subgraph of . Now we will show that each vertex in or in is not connected by any single vertex in . We know that and . Clearly, for any and for any , it follows that , so that . As a consequence, . Secondly, for any and for any , we consider the following cases:

- (i)

-

Case: .

Let with , we got , so , clear that

- (ii)

-

Case: .

Let with , . If , clear that . If , we have with . Since , we get .

For any and for any , .

Now, let and where , .

- (i)

If ( or ) and ( or ), we obtain where and . Hence, .

- (ii)

If ( and ) or ( and ), obviously , so that .

Now, consider the subgraphs of induced by and . Let and with where , and . Clearly, and . We will consider cases:

- 1.

If and and , then . Thus, if and only if .

- 2.

If and and , then . Thus, if and only if .

- 3.

If and and , then . Thus, if and only if .

- 4.

If and and , then . Thus, if and only if .

- 5.

If and and , then clearly , so .

- 6.

If and , then . Thus, if and only if .

- 7.

If and and , then clearly , so that .

- 8.

If and and , then clearly , so that .

- 9.

If and and , then clearly , so that .

From these cases, for any , , we will have either implies or implies .

Now, we construct a mapping by , for any . It is easy to see that f is bijective. Moreover, by this correspondence we have that the subgraph induced by in is isomorphic to .

For the case with , the proof is similar to the case with .

□

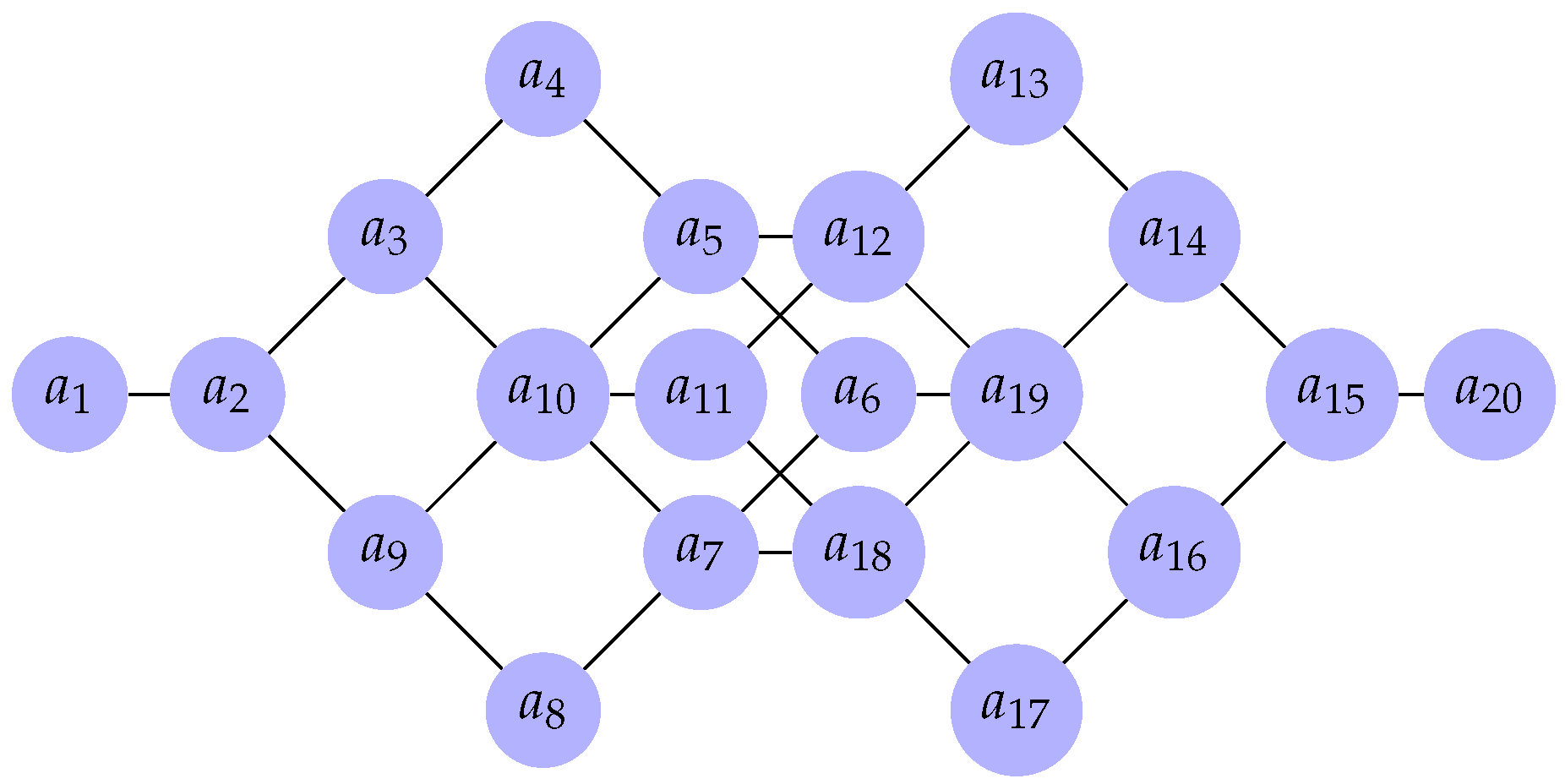

The following figure provides a visual representation of the 3-token graph of

.

Figure 2.

The Graph .

Figure 2.

The Graph .

From Theorem 2, which describes the 3-token graph of the disjoint union of two graphs, along with Theorem 2.1 as given in [

5] describing the structure of the 2-token graph of disconnected graphs, we can iteratively determine the 3-token graph of a disconnected graph consisting of multiple components. By applying these results step by step, we can construct the 3-token graph for more complex disconnected graphs with several individual components.

Theorem 3.

Let be arbitrary natural number and let be arbitrary graphs. Then

Proof. We will prove by mathematical induction on the number of component

n. By Theorem 2, the assertion is true for

. Assume that the assertion is true for arbitrary

n. We proceed for

. By assumption and by Theorem 2.1 on the 2-token graph of disconnected graphs given in [

5], we have

□

As a direct consequence of Theorem 3, we derive the following result concerning the number of components in the 3-token graph of the disjoint union of graphs.

Corollary 1. Let be arbitrary natural number and let be arbitrary graphs. The graph is disconnected and has components.

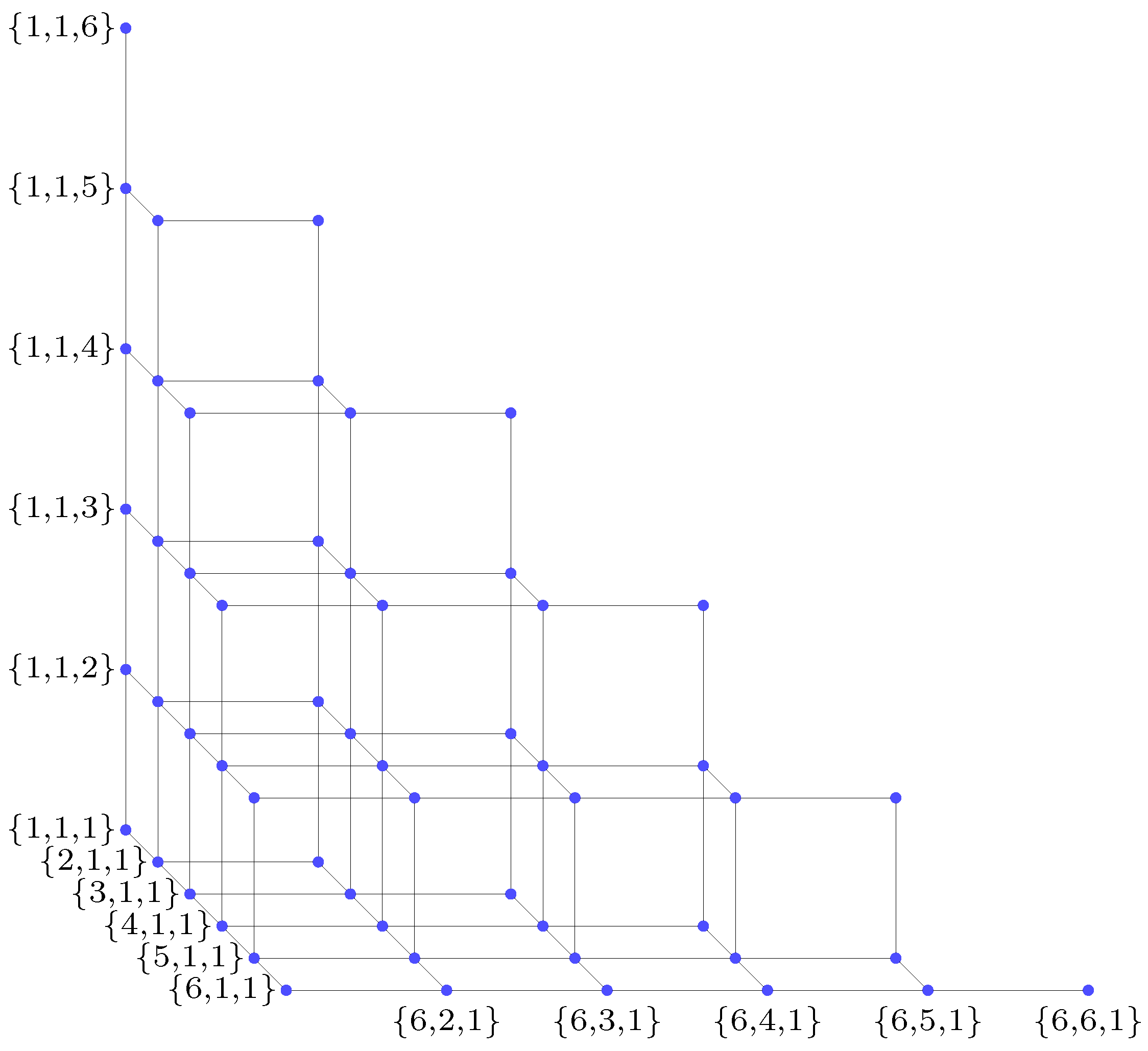

Having derived the result for the 3-token graph of disjoint union graphs with multiple components, we now shift our focus to a specific graph known as the cubical staircase graph. This graph possesses a unique structure and will, in subsequent analysis, be shown to be isomorphic to the 3-token graph of a path. By exploring the properties of the cubical staircase graph, we aim to gain deeper insights into the characteristics of 3-token graphs and their structural relationships.

Definition 1.

Let be a natural number. The cubical staircase graph is a graph that is isomorphic to the graph with

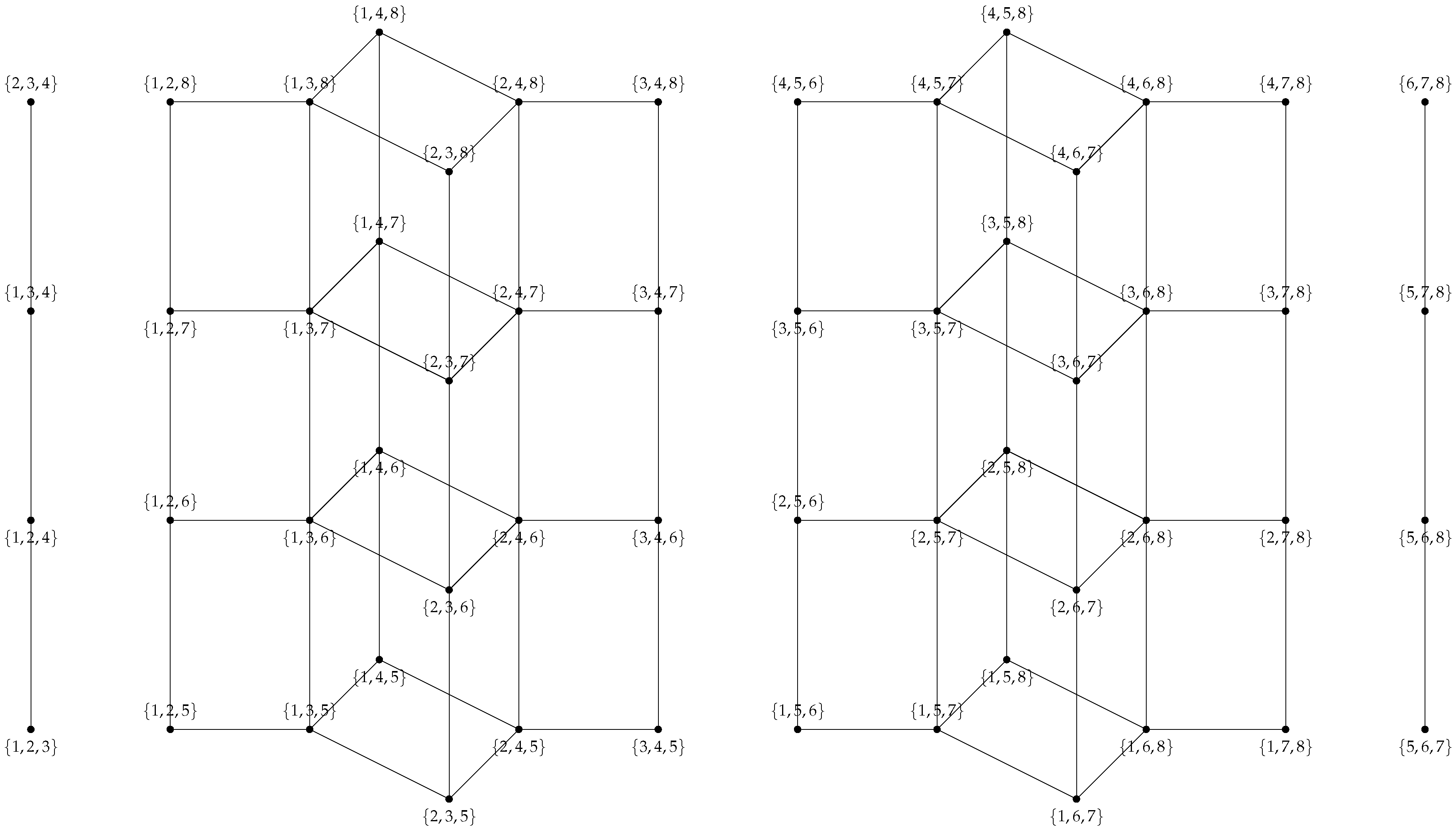

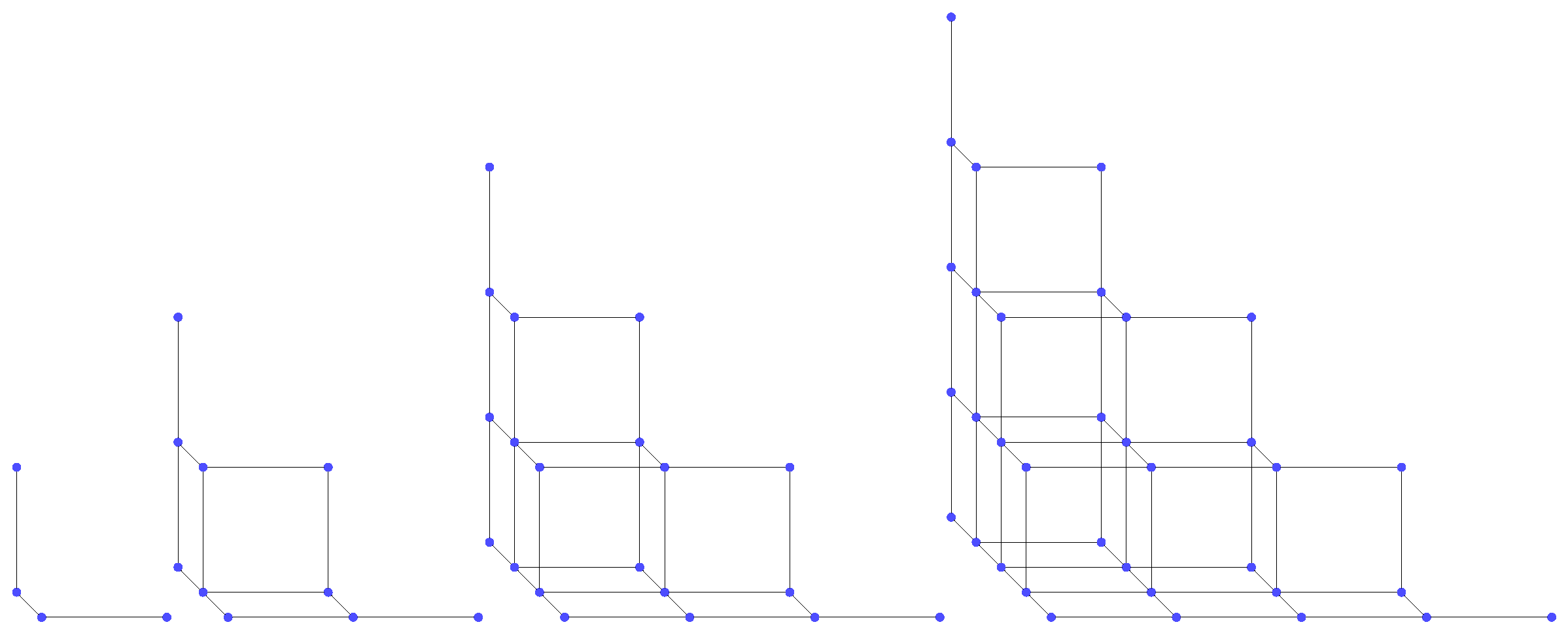

In the following example, we provide a particular cubical staircase graph

for

, as shown in

Figure 3.

For

, the graph

are described in

Figure 4.

The following lemma provides the distance between any two distinct vertices in the graph , offering a clearer understanding of the graph’s structural properties.

Lemma 2.

For any natural number , let be arbitrary. Then

Proof. Consider the graph for . Let We observe for some cases.

- (i)

Cases

, there exists a path

- (ii)

Cases

, there exist a path

So, from Cases (i) and (ii), we get . Now, we observe for following cases.

- (iii)

Cases

. There exists a path

- (iv)

Cases

. There exists a path

Consequently, we get

. Similar to Cases (i) and (ii) together with Cases (iii) and (iv), we have

and as a result, we obtain

Since

if and only if either

, and

; or

, and

; or

, and

, we get

□

The lemma below demonstrates that the graph contains no triangles.

Lemma 3. For every , graph has no triangle.

Proof. Let

where

. We know that

In this case, we only consider for

Also we have

Since

so we have no any subgraph that isomorphic to graph

. □

The following result establishes that the graph is either one-colorable or two-colorable.

Theorem 4.

For any positive integer . Graph has chromatic number

Proof. For , we have that the graph is isomorphic to . Then, we get . Now, let , for any vertex , we color the vertex with the first color if is even and we color the vertex with second color if is odd. Now, for all , we get

- (i)

Case 1: , , and .

- (ii)

Case 2: , , and .

- (iii)

Case 3: , , and .

For all cases, we have that and are odd and even respectively or even and odd respectively. Therefore, vertex and vertex have different colors. □

In these three following theorems, we determine the clique number , the diameter and the independence number of the graph when , respectively.

Theorem 5.

For any positive integer , the graph has the following properties:

Proof. Let . For , we know that is a so . Then, for , it is clear that . From Lemma 3 we know that the does not have a triangle. We conclude that does not have as an induced subgraph. In other word, . Thus, . □

Theorem 6.

For any , the graph has the following property

Proof. Consider the vertices

. Using Lemma 2, we obtain:

Now, for any

, the following holds:

□

Theorem 7.

For any positive integer , the graph satisfies that

Proof. If

n is odd, we can construct an independent set in graph

,

we get

and it is clear that

A is the only independent set with cardinality

in

. From

A, if we add one vertex

, i.e.

is even.

- (i)

If , we can found such that .

- (ii)

If , we can found such that .

So,

is not an independent set. If

n is even, we have

is an independent set in graph

. We have that

. It is clear that the independent sets with cardinality

in

are only the sets

B and

C. From

B, if we add one vertex

, i.e.

is odd.

- (i)

If , we can found such that .

- (ii)

If , we can found such that .

So, is not an independent set. Then, the case for the set C will be the same as the case when n is odd, so it follows that is not an independent set. □

In the study of token graphs, understanding the structural relationships between graphs provides valuable insights. In the following theorem, we demonstrate that the 3-token graph of the path graph is isomorphic to the graph for , establishing a clear connection between these two graph classes.

Theorem 8. Let , be path graph. Then .

Proof. For

, we know that

Now, let

and

where

. First, we have that

Then for any

,

if and only if

for some

. Now, we construct a mapping

by

for any

with

. Let

. If

, then we have

for some

. WLOG, let

, i.e.

and

.

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

- (v)

- (vi)

Conversely, let

. Let

and

. Then,

It means that either

and

or

and

, or

and

. This is equivalent to,

Thus,

or

or

. Therefore,

, so that

is an isomorphism between

with the

token graph

. □

As a direct consequence of Theorem 8, we obtain the following corollaries.

Corollary 2. For any positive integer , the graph has the following properties:

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

.

Proof. It is clear from Theorem 8, Theorem 4, Theorem 5, Theorem 7, Theorem 6. □

To understand the structure of the automorphism group of , where represents the path graph with , we delve into its symmetries and transformations. The automorphism group, , captures all the graph’s self-isomorphisms, preserving vertex connectivity. The following theorem establishes the precise characterization of based on the value of n.

Theorem 9.

Let , be a path graph. Then,

Proof. For

, we know that the graph

is isomorphic to

. Then,

. For

and

, by Theorem 8, we have

. Let

f be an isomorphism on

. Then,

f is either an identity mapping

or a bijection function

g that maps

to

for every

. It is clear that

. Hence,

which is isomorphic to the group

. Therefore, we get

For

, the graph

is given as follows. Let

f be an isomorphism on

. Then, the possible functions for

f are only the identity function or the bijective functions

, or

, with the following mappings.

Table 1.

Automorphism of .

Table 1.

Automorphism of .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus, , where , , and , which is isomorphic to the group . □

Observe the following independent edge set in the graph

for every

:

for even

n, and

for odd

n. We hypothesize that these sets represent the largest independent edge sets that can be constructed. Based on this hypothesize, the following conjecture is proposed.

Conjecture 1.

For any , the 3-token graph satisfies the following.

Open Problem. For further research, it would be interesting to investigate the structure of the 3-token graph of cycle graphs and other types of graphs. Additionally, the k-token graph of path graphs presents further open problems that could be explored.