1. Introduction

Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) is a widely recognized technique for additive manufacturing (AM) of metal parts. The technique enables the production of parts with complex geometries by utilizing a laser to melt and consolidate powder particles layer by layer. While the design flexibility in AM makes LPBF well-suited for applications among others in the tooling [

1] and medical sectors [

2], its adoption for load-bearing components often remains limited. In this regard, the low as-built surface quality falls short compared to conventionally manufactured parts [

3]. Controlling the surface quality is particularly challenging for the often complex-shaped AM parts, as the quality highly depends on the build orientation [

4]. The morphology of up-facing inclined surfaces is complex, as it varies with the slope angle and is affected by the staircase effect, along with partially molten particles and elevated edges at the stair steps [

5].

It is well known that the poor surface quality of metal parts fabricated through LPBF can negatively impact their fatigue performance. Early fatigue failure is frequently associated with a high as-built roughness, surface defects and notches [

6]. These sites locally amplify the stress under loading, thereby increasing the risk for crack nucleation and initiation. Local stress concentration factors capture this by considering the surface valleys as notches that act as stress concentrators. The approach accounts for the notch morphology by extracting the depth-to-radius ratio for each valley and calculates the corresponding local stress values [

7]. Different studies have demonstrated the suitability of stress concentration factors as input for predicting the fatigue performance of both additively manufactured [

7] and machined parts [

8].

Post-AM surface treatments are systematically applied to improve the surface quality and consequently the fatigue performance. While conventional methods such as milling, polishing or grinding are commonly used, various alternative treatments are constantly explored to accommodate the complex geometries of AM parts as reviewed in [

9]. Considering the considerable efforts associated with surface finishing of intricate part geometries, improving the as-built surface quality would offer significant benefits.

In this respect, laser remelting is a promising technique to improve the surface quality directly during building. While laser remelting enables to enhance the quality of horizontal surfaces through re-scanning of build layers [

10], the treatment of inclined surfaces is less common as those are covered by loose powder particles. A recently introduced dual laser powder bed fusion (DLPBF) strategy demonstrated the quality improvement of up-facing inclined surfaces using laser-induced shock waves for powder removal and subsequent laser remelting. Although these recent studies have demonstrated notable improvements in three-point bending fatigue performance of such treated parts made from M300 and Ti64 [

11] and an aluminium-based metal matrix composite [

12], further research is required to explore the wider potential of this novel approach. Specifically, it remains unexplored whether this surface treatment can be effectively applied to enhance the fatigue performance of parts with variable initial surface quality resulting from different building strategies. This is particularly relevant for recent promising approaches that utilize a high layer thickness to increase build rates but severely compromise the surface quality [

13].

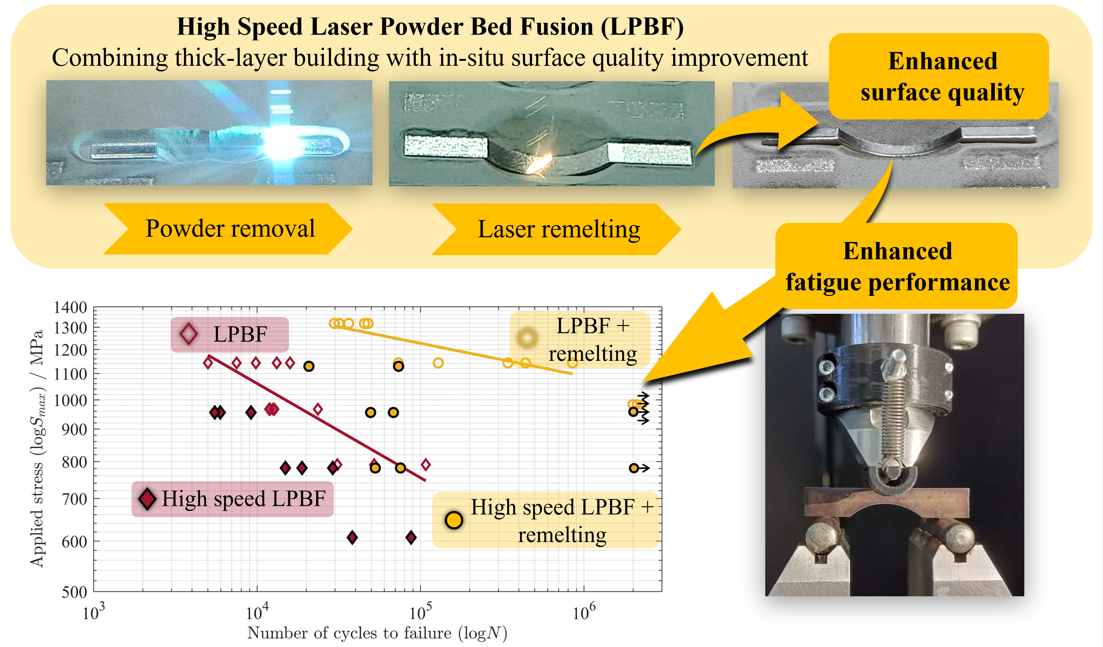

This work advances a DLPBF strategy towards high speed building of up-facing inclined metal parts with enhanced fatigue life made from M789, a novel tool steel powder. In-situ surface quality improvement through laser remelting is applied to parts produced with different building strategies, namely a standard strategy using a layer thickness (LT) of 60 μm (LT60), a high productivity strategy using a high LT of 120 μm (LT120), and a hull-bulk strategy using a LT of 60/120 μm (HB60/120). A three-point bending fatigue campaign is conducted to evaluate the fatigue life of such treated samples in comparison to reference samples with as-built (AB), electrical discharge machined (EDM) and mechanically polished (P) surface conditions. A comprehensive analysis of the surface morphology is presented, quantifying surface roughness, critical stress concentration factors, and the lateral size of dominant surface features. The strategy’s capability to simultaneously enhance productivity, surface quality and fatigue life is demonstrated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Manufacturing

Samples were fabricated using an innovative dual laser PBF machine setup. The setup consists of a commercially available ProX® DMP 320 machine (3DSystems, Belgium) equipped with a continuous wave laser (CW) with a nominal spot size of d1/e2,CW =90 μm and a central wavelength of 1070 nm. The machine is further equipped with a nanosecond pulsed wave (PW) laser with a nominal spot size of d1/e2,PW = 50 μm, and a central wavelength comparable to the CW laser. The laser optics setup enables sequential processing with either the CW or PW laser. Slicing and hatching was performed using 3DXpert (Oqton, Germany). The material selected is a novel tool steel powder, BÖHLER AMPO M789, from voestalpine Böhler Edelstahl GmbH & Co KG (Kapfenberg, Austria).

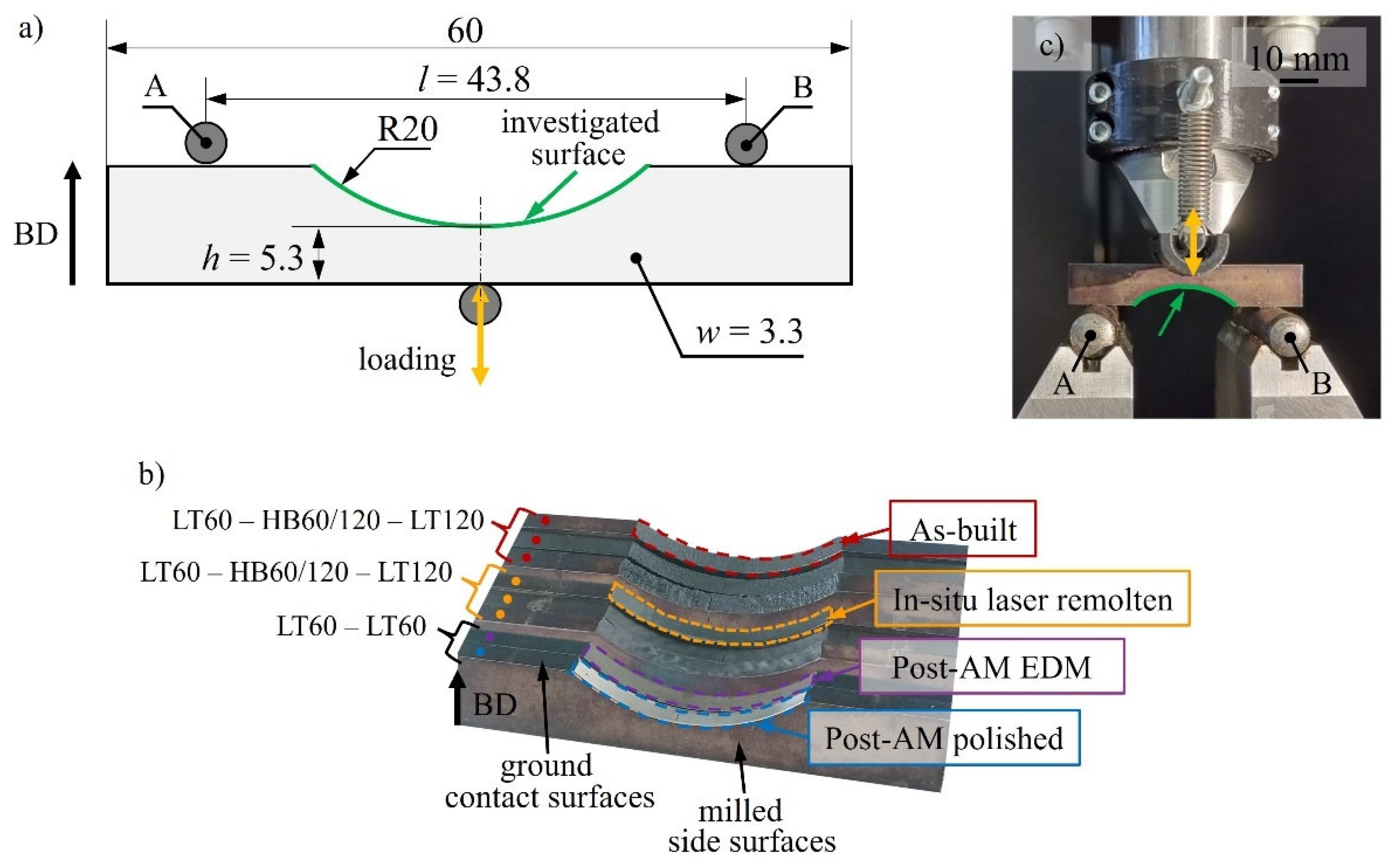

Figure 1a depicts the geometry that was used to fabricate parts using three different layer thicknesses (LT): standard LT of 60 μm (LT60), high LT of 120 μm (LT120) and hull-bulk LT of 60/120 μm (HB60/120), respectively. LT60 samples were manufactured using parameters recommended by 3D Systems [

14]. To increase the productivity, samples were also manufactured employing a recently proposed high speed LPBF strategy using LT120 [

13], which comes at the expense of a reduced surface quality. Additional samples were manufactured through an HB60/120 strategy adapted from [

13], aiming to restore the surface quality to LT60 level by combining LT60 for the hull region of the samples and LT120 for the bulk. The hull thickness was set to 1000 µm, with an overlap of 150 µm between hull and bulk. In addition, 12 up-safety layers were used to reach a stable LT60 up-facing surface quality.

All samples underwent the same post-processing after LPBF. The vertical side surfaces were milled to focus the investigations on the curved surface (

Figure 1b). The horizontal top and bottom surfaces that are in contact with the rollers were ground to ensure parallelism (

Figure 1b,c). The samples underwent a stress-relieving heat treatment consisting of solution annealing at 1000 °C for 1 hour followed by aging at 500 °C for 3 hours in a nitrogen atmosphere. Consequently, in this study the term ‘as-built’ refers to the surface condition. This heat treatment yielded consistent hardness values across the investigated sample conditions of

HLT60=(51.7 ± 0.5) HRC,

HLT120=(51.5 ± 0.5) HRC and

HHB60/120 =(51.7 ± 1.2) HRC, obtained from each 10 measurements using the Wilson 4-JR equipment with a 150 kgf load. The hardness values are consistent with those available for solution annealed and aged M789 material [

14,

15,

16]. FAverage sample densities of

ρLT60=(99.73 ± 0.03) %,

ρLT12=(99.74 ± 0.03) %, and

ρHB60/120=(99.69 ± 0.03 ) % based on 8 samples per condition were measured using the Archimedes principle with theoretical density of 7.715 g/cm

3.

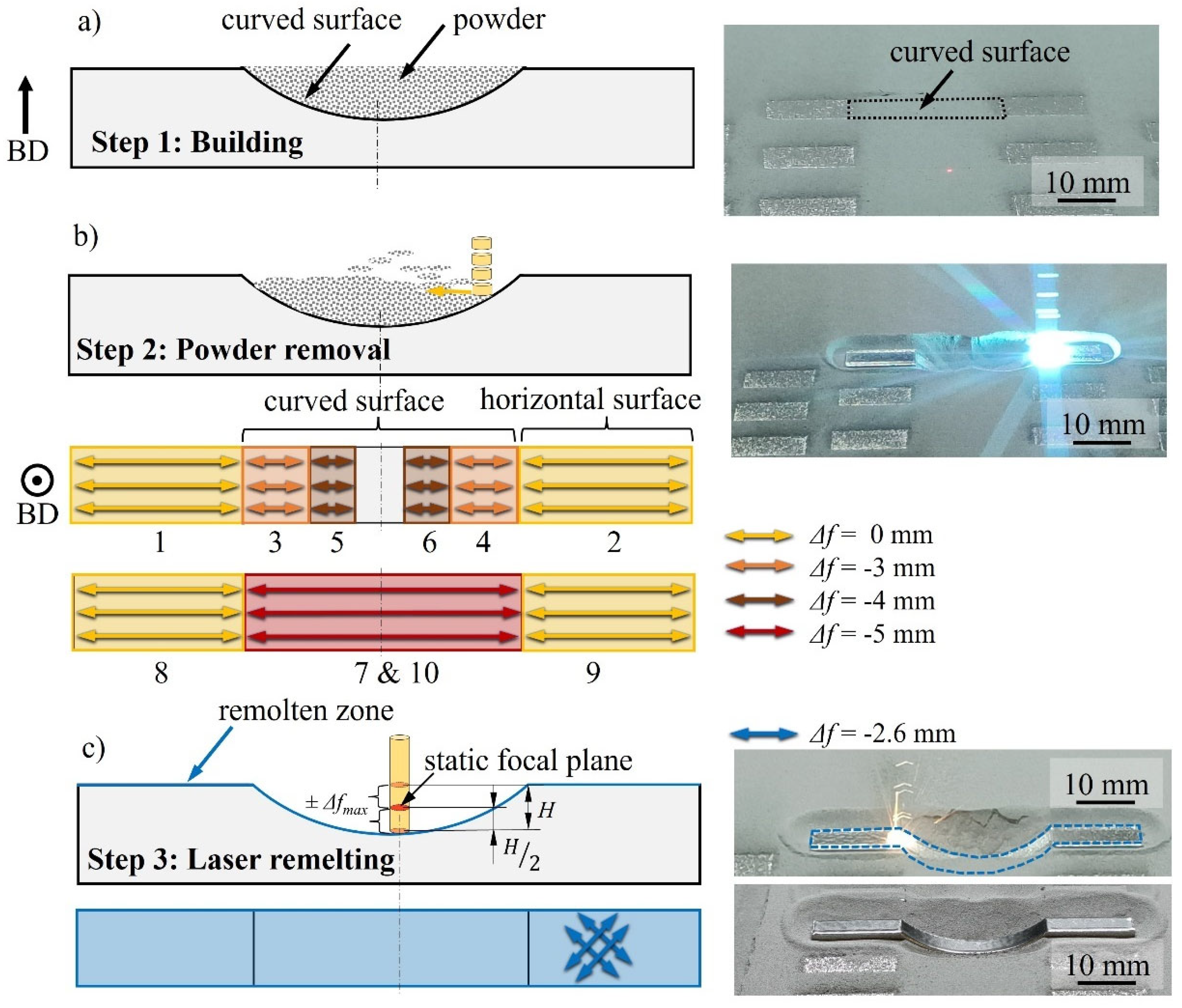

2.2. Dual Laser Powder Bed Fusion Strategy

The proposed DLPBF strategy was specifically developed for the treatment of up-facing inclined surfaces. The DLPBF strategy is based on previous findings in [

11], and was in this study further developed to enable the treatment of samples made from a novel tool steel M789 with variable initial surface states resulting from building using different layer thickness. The strategy consists of three steps as illustrated in

Figure 2. Firstly, the samples are built through LPBF (

Figure 2a). Secondly, after completing the last layer, pulsed laser-induced shock waves are used to remove the powder that is covering the up-facing curved surface (

Figure 2b). The full scan sequence for powder removal scan passes is illustrated in

Figure 2b. The treatment happens in different sections with manually adjusted focal plane by

Δf (

Figure 2b). This adjustment is necessary since treating an inclined surface with a static focal plane leads to constant laser defocusing along the surface slope, reducing the efficiency of shock waves for powder removal [

11]. Thirdly, laser remelting of the newly exposed up-facing surface is performed using four scan passes with the scan orientation indicated in

Figure 2c. The processing parameters are selected based on previous research on M789 material [

17], using for powder removal an average laser power of 45 W, a scan speed of 500 mm/s, a hatch spacing of 40 μm, a pulse repetition rate of 100 kHz, and a pulse duration of 30 ns, and for remelting a laser power of 200 W, a scanning speed of 500 mm/s, and a hatch spacing of 80 μm.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed DLPBF strategy, the fatigue performance of laser remolten (LR) samples was compared to reference samples in as-built (AB), electrical discharge machined (EDM), and mechanically polished (P) surface conditions. Both post-AM surface treatments were performed by the company Deceuninck (Hooglede-Gits, Belgium).

2.3. Surface Characterization

The surface quality was assessed through tactile profilometry with a Mitutoyo Formtracer CS-3200. It was evaluated on the up-facing curved surface based on 100 profiles spaced by 20 μm across an evaluation length of 10 mm, using a probe with 2 µm tip radius. The primary profiles were filtered according to ISO 16610–21 [

18] with short and long cut-off wavelengths of

λs=2.5 μm and

λc=2.5 mm, respectively.

Surface parameters [

Ra,

kt,crit,

Ral, Rdq] were calculated based on aforementioned tactile profiles. The arithmetic mean roughness

Ra and root mean square gradient

Rdq were calculated according to ISO 21920–2 [

19]. Critical stress concentration factors

kt,crit were evaluated according to the method described in [

8]. This method treats the profiles

a(x) as a function of cosine components using Eq. (1) with

Ai,

λi=1/

fi and

ϕi being the

ith cosine amplitude, wavelength, frequency and phase, respectively. The profiles were filtered with a short wavelength cut-off filter of

λs=25 μm with a Gaussian filter according to ISO 16610-21 [

18] before calculating corresponding stress concentration profiles

kt(x) with Eq. (2). The stress concentration factor at each valley’s location, defined as local minimum in

a(x), were extracted from

kt(x). Critical notches were identified as those with a probability exceeding 95 % in the generalized extreme value distribution according to [

7].

The lateral dimensions of the dominant surface features were determined by the autocorrelation length

Ral according to ISO 21920–2 [

19], defined as the horizontal distance over which the autocorrelation function decays to 0.2 [

20]. A smaller

Ral indicates dominant fine features with rapid spatial variation, while a larger

Ral denotes dominant coarser features with more gradual changes. The presented results for

kt,crit and

Ra represent mean values with corresponding standard deviations based on the samples included in the fatigue tests (

Figure 4). The results reported for

Ral and

Rdq are based on five samples per condition.

The chamfer observed on mechanically polished samples was characterized through tactile surface profile measurements. The chamfer height was defined as the maximum height difference between the part’s edge and the investigated surface within the middle section. The characterization was conducted using 10 tactile profiles spaced by 100 μm taken from the middle section.

2.4. Fatigue Testing

Three-point bending fatigue tests were performed on an Instron Electropuls E10000 machine equipped with a 10 kN dynamic load cell. The tests were performed with a stress ratio

R of 0.1 and a frequency of 30 Hz. The samples were subjected to sinusoidal compression-compression loading resulting in cyclic tensile stress on the surface under investigation (

Figure 1a,c). Tests were performed at three stress levels until samples’ failure, or run-out at

Nf ≥ 2 ·10

6 load cycles without failure. The stress levels were chosen as percentage of the materials’ yield strength, with

σy,LT60=1758 MPa based on testing of three round tensile specimens type 4 according to ASTM E8 standard, with the values in agreement with [

14], and

σy,LT120=1737 MPa [

13]. For the HB60/120 condition the same stress levels were applied as those for the LT60 standard. The applied loads

F required to achieve the maximum stress levels

Smax were calculated using Eq. (3), with the area moment of inertia

I of a beam determined from Eq. (4):

The bending span l was set constant to 43.8 mm. Sample dimensions (width w, height h) were measured at the critical cross-section. The fatigue data is presented with SN curves for the investigated sample conditions produced with standard LT60 (AB, LR, P, EDM), high LT120 (LR, AB), based on a minimum of 10 and 8 samples for each condition, respectively. Additional fatigue data was collected for samples produced through a hull-bulk strategy (HB60/120), with 5 samples tested for both the AB and LR conditions. The number of cycles to failure reported represent arithmetic mean values and corresponding standard deviations for the samples tested at each respective stress level. The statistical significance of differences in fatigue life between sample conditions was assessed using p-values, with the reported improvements meeting a threshold of p<0.05 (95% confidence level), and p<0.32 (68% confidence level) for polished samples.

3. Results

3.1. Surface Quality

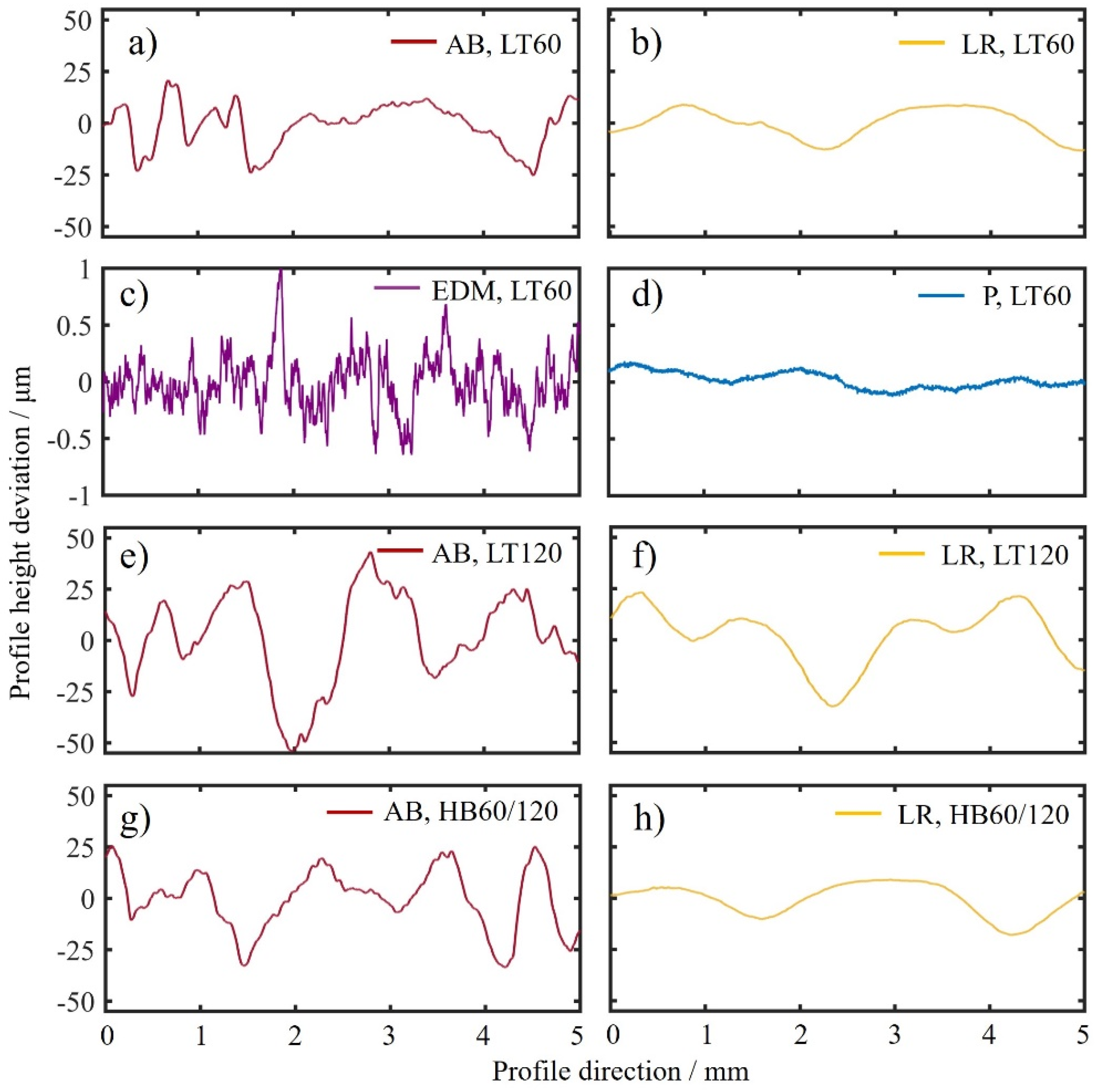

Figure 3a-h present the surface profiles for the investigated sample conditions along with

Table 1 listing the calculated surface parameters and their corresponding standard deviations. AB samples exhibit the highest surface roughness of R

a=14.0 μm. LR reduces the roughness to R

a=5.6 μm, which corresponds to a reduction of 60 %. Mechanical polishing and electrical discharge machining achieves significantly lower roughness values of R

a=0.2 μm and R

a=0.7 μm, respectively.

The k

t,crit trends observed for the investigated sample conditions are similar to those for R

a (

Table 1), however the differences between the investigated surface conditions are less pronounced. AB and P reference samples display the highest and lowest values of k

t,crit =2.1 and k

t,crit =1.0, respectively. Notably the LR samples exhibits a similar k

t,crit= 1.2 compared to the EDM samples (k

t,crit=1.3), despite exhibiting a R

a value by 8 times higher. While the roughness parameter takes only the depth of valleys into account, k

t,crit considers the notch morphology including both the valleys’ depth and radius. Laser remelting redistributes molten material from roughness peaks to valleys. The molten material partially fills the valleys resulting in a smoothened surface morphology compared to initial AB state, which is shown by a reduction of k

t,crit by 40 %.

Differences in the surface morphology among the investigated samples are evident from the tactile surface profiles displayed in

Figure 3a-d. The reference EDM samples show abruptly changing, spiky surface features (

Figure 3c). A similar morphology is observed for the AB reference samples, but with higher amplitude and lower spatial frequency (

Figure 3a). In contrast, the LR samples exhibit a gradually changing surface profile characterized by a low spatial variation (

Figure 3b). This is reflected by the autocorrelation length R

al, which quantifies the lateral size of the dominant surface features. The feature size increases for EDM, AB and LR with corresponding R

al values of 45 μm, 128 μm, 470 μm (

Table 1). For P samples a significantly larger autocorrelation length of 1182 μm suggests the absence of dominant surface features. These observations are further supported by the root mean square gradient parameter R

dq, which shows an increasing local surface slope accross the surface conditions, following the sequence P, LR, EDM and AB samples (see

Table 1).

Figure 3e-h and

Table 1 further display the surface morphology for samples produced with a high layer thickness of LT120 and a hull-bulk strategy HB60/120. The AB samples produced by the LT120 strategy exhibit the highest observed R

a=26 μm and k

t,crit=2.4, representing an increase of by 84 % and 11 % compared to the standard LT60 approach. This aligns with previous work that demonstrated significant improvements in productivity with this LT120 strategy, albeit at the expense of the surface quality

[13]. AB samples produced using the HB60/120 strategy exhibit a R

a=16 μm and k

t,crit=2.3, which widely restores the surface quality to LT60 level. Laser remelting improves the surface quality for both sample conditions, shown by reduction of R

a and k

t,crit by 28 % and 33 % (LT120) and 59 % and 41 % (HB60/120). Moreover,

Table 1 presents the R

al and R

dq values for the investigated conditions, reinforcing previous observation that laser remelting consistently results in a smoothened surface morphology displayed by an increased feature size (R

al) and reduced local surface slope (R

dq) compared to the AB reference samples.

3.2. Fatigue Performance

Figure 4a presents the three-point bending fatigue test results for the investigated sample conditions produced with a standard layer thickness LT of 60 μm. LR samples show the best performance at the comparably low and intermediate stress levels of 967 MPa and 1143 MPa, followed by the P, EDM and AB samples. At the highest stress level of 1317 MPa, the P samples exhibit an improved performance over LR samples.

AB samples exhibit the poorest fatigue performance across the investigated stress levels. They fail consistently below Nf <100 ·103 load cycles at Nf =(64 ± 4)·103 (at 791 MPa), Nf =(15 ± 5)·103 (at 967 MPa) and Nf =(10 ± 4)·103 (at 1143 MPa). In comparison, the LR samples record consistent run-outs without failure after Nf =2·106 load cycles at an applied stress level of 967 MPa. Moreover, LR samples only fail after Nf =(367 ± 310)·103 load cycles at a stress level of 1143 MPa, corresponding to a fatigue life improvement compared to the AB reference by a factor of 36.

The EDM reference samples show a consistent fatigue performance, failing at the stress levels of 967 MPa, 1143 MPa and 1317 MPa at Nf =(79 ± 23) ·103, Nf =(36 ± 12)·103, and Nf =(22 ± 14)·103 load cycles, respectively. In comparison, LR samples outperform the EDM reference sample across the respective stress levels, showing an improvement in fatigue life by up to a factor of 10.

Despite the large scatter in the data of the P reference samples, they demonstrate a notably increased fatigue life compared to AB and EDM reference samples across all stress levels. Furthermore, the P reference samples exhibit an enhanced fatigue life compared to the LR samples at the high stress level of 1317 MPa by almost a factor of 4. In contrast, LR samples show an enhanced fatigue life at the stress levels of 967 MPa and 1143 MPa. At corresponding stress levels, LR samples consistently run-out without failure at Nf =2·106 load cycles, respectively exhibit a fatigue life improved by a factor of 3.

Figure 4b further presents the fatigue performance of samples produced with a high layer thickness of 120 μm (LT120) and a hull-bulk strategy of 60/120 μm (HB60/120). The LR samples demonstrate dominant performance, with the HB60/120 outperforming LT120, followed by their respective AB reference samples.

Laser remelting of samples produced with a high layer thickness of LT120 consistently achieves an enhanced fatigue life compared to the AB references. While the AB reference samples made from LT120 show early failure with Nf =(7 ± 2)·103 at a stress level of 955 MPa, one LR sample runs-out at Nf =2·106 load cycles and other samples fail at Nf =50·103 and Nf =68·103 load cycles. Hence, this corresponds to an improvement in fatigue life by a factor of 8. Similarly, reference AB samples produced through the HB60/120 strategy fail consistently after Nf =(17 ± 4)·103, whereas their LR sample counterparts fail at Nf =(434 ± 267)·103, representing an improvement in fatigue life by a factor of 25. Furthermore, the significant performance increase achieved through remelting of the LT120 and HB60/120 samples is well demonstrated by their ability to compete with the reference samples produced using the LT60 approach. In fact, they exhibit a similar or improved fatigue life compared to the reference EDM samples, respectively, and outperform the AB LT60 reference. Specifically, laser remelting samples that were build using LT120 leads to a fatigue life enhancement compared to the AB LT60 reference by up to a factor of 4.

4. Discussion

The proposed DLPBF strategy enables significant improvements in fatigue life compared to the investigated reference samples. It is evident that the clear reduction in surface roughness Ra compared to the as-built AB reference by up to 60 % contributes to the increase in performance. However, the Ra parameter does not sufficiently explain the increased performance compared to the reference samples that underwent surface finishing as they have a roughness smaller by several orders of magnitude. And similarly, it does not explain the improved performance in comparison to specific AB samples conditions that exhibit a similar roughness. Given the similar sample quality, as evidenced by consistent values for density, hardness and yield strength across the investigated sample conditions, it strongly suggests that differences in the surface morphology are responsible for the observed fatigue performance.

The critical stress concentration factor

kt,crit considers the morphology of surface valleys through the ratio of depth-to-radius. Surface valleys act as micro-notches locally increasing the stress and hence the risk of cracks initiation from this site. Consequently, a deep and steep valley morphology corresponds to a high

kt,crit value, whereas a shallow and gradual morphology corresponds to a low

kt,crit value. LR samples display a slightly lower

kt,crit value compared to the reference EDM samples, despite exhibiting a

Ra value larger than a factor of 8. This is in line with the surface profiles depicted in

Figure 3, illustrating a smoothened, gradually changing surface morphology for the LR sample (

Figure 3b). In contrast, the EDM sample exhibits numerous abruptly changing surface features that are likely to act as stress concentrators under loading (

Figure 3c). Examining this further, the lateral size of the dominant surface features was quantified using the autocorrelation length

Ral (

Table 1). The LR exhibits wider surface features compared to the EDM samples, displaying a dominant feature width of

Ral=45 μm and

Ral=474 μm, respectively. In addition, EDM samples exhibit steeper local surface slopes by 58 % quantified by

Rdq (

Table 1). Hence, the EDM samples are densely packed with abruptly changing surface features, corresponding to a surface feature density increased by almost a factor of 11. This is linked to a higher number of potential crack initiation points and an unfavourable load distribution, both of which raise the likelihood of early failure.

Despite the large scatter observed for the data of the polished reference samples, it is evident that they display significantly increased fatigue life at the highest stress level compared to the LR samples, whereas LR samples are superior at the lowest stress level. The scatter is likely attributed to the presence of a chamfer located at the vertical side surface of the investigated curved surface, underscoring the challenges associated with post-AM surface finishing of complex geometries. The manual polishing operation resulted in maximum height reduction of 155 μm to 590 μm for the smallest and largest observed chamfers, respectively, captured by tactile profile measurements. Consequently, the reduced cross-section leads to a local stress increase at the chamfers of approximately 6 % and 27 %, respectively, which has likely reduced the fatigue life and increased the scatter. Moreover, following previous explanations, it is hypothesized that the gradual changing surface morphology of LR samples is beneficial compared to abruptly changing fine features observed on the P surfaces (

Figure 3b,d). This is supported by a

kt,crit value that approaches that of the P reference samples, despite having a larger roughness by a factor of 28.

In an effort to simultaneously improve productivity, surface quality and fatigue performance, LR was applied to samples that were built with a high layer thickness of 120 μm and a hull-bulk strategy (60/120 μm), respectively. As displayed in

Figure 4b, such treated samples demonstrated a significantly improved performance compared to investigated AB reference samples, including those made from the standard LT60 approach. Furthermore, the LR samples even displayed a similar or significantly enhanced performance compared EDM reference samples, respectively. Given that the LR samples made from LT120 have a

Ra of about 27 times higher than the EDM reference samples, the performance is likely attributed to the gradually changing surface morphology as displayed in

Figure 3f, in contrast to the abruptly changing surface features (

Figure 3c), respectively. This is supported by LR samples made from LT120 having a comparable

kt,crit value and a reduced density of dominant surface features by a factor of 10 according to

Ral (

Table 1) compared to the EDM reference samples. Similar explanations apply to the performance improvement for LR HB samples.

The production time for the proposed DLPBF strategy includes the build time through LPBF and additional time for the surface treatment. It is worth nothing that the production time depends on the number of samples to be treated, their size and design. In this case, the build time for a job including 16 samples using the standard LT60 approach was 170 min, compared to 94 min with the LT120 strategy. This corresponds to a reduction in build time by 81 %. The surface treatment per sample required up to ~130 s for powder removal, ~30 s for remelting, and approximately ~120 s for manually adjusting the focal plane. For the LT120 job, where 8 samples were laser remolten, the resulting production time was 131 minutes. Hence, despite the additional surface treatment, this represents a 30 % shorter production time compared to the standard LT60 approach. Simultaneously, the LR samples produced using LT120 exhibited an enhanced fatigue life compared to AB LT60 samples by up to a factor of 4. Moreover, as the DLPBF treatment happens directly in the AM machine, it has the potential to avoid or limit the need for post-AM surface finishing along with the associated costs and time. Despite its advantages, it is important to point out that the scanning strategy involves several manual operations to adjust the focal plane to avoid efficiency losses (see

Figure 2), making it impractical for treating larger components. These limitations were recently addressed, enabling fully automated treatment of large components directly during building [

17].

5. Conclusions

This work further developed a DLPBF strategy demonstrating simultaneous improvements in productivity, surface quality and fatigue life of parts with up-facing inclined surfaces, made from M789 - a novel tool steel powder. The proposed strategy combines building using a high layer thickness of 120 μm and subsequent in-situ surface quality improvement. This is achieved through selective removal of powder covering the inclined surfaces via laser-induced shock waves and subsequent laser remelting. The main findings are:

Laser remelting (LR) demonstrated significant improvements in surface quality and hence fatigue life, applied to samples with variable initial surface state resulting from building with a standard layer thickness of 60 μm (LT60), a high layer thickness of 120 μm (LT120), and an hull-bulk strategy using a 60/120 μm (HB60/120) approach, respectively. Fatigue life was consistently improved across the investigated AB conditions, reaching a performance increase of up to a factor of 36.

This significant improvement in fatigue life compared to AB reference samples was attributed to a smoothened surface morphology after remelting, shown by a reduction in surface roughness Ra and critical stress concentration factor kt,crit by up to 60 % and 40 %. Moreover, the smoothened surface morphology exhibited gradually changing features that were up to a factor of 4 wider displayed by the autocorrelation length Ral compared to the abrupt and rapidly changing surface features observed for the AB reference samples. This was associated with a beneficial stress distribution under loading and a reduced number of potential crack initiation points.

LR samples demonstrated an increased fatigue life compared to electrical discharge machined (EDM) reference samples by up to a factor of 10, despite having a roughness 8 times greater. It was associated with the smoothened surface morphology of LR samples, quantified by a similar kt,crit and gradual changing surface features with significantly increased lateral width displayed by Ral. Moreover, LR samples demonstrated an enhanced fatigue life compared to that of mechanically polished (P) reference samples at a relatively low and intermediate stress levels, whereas P samples dominated at higher stress level.

LR samples produced using a hull-bulk (HB60/120) strategy allowed to widely restore the surface quality to the LT60 level, and consequently demonstrated similar fatigue life improvement.

In an attempt to combine increased productivity, surface quality and hence fatigue performance, LR was applied to samples fabricated using a high layer thickness of 120 μm. While this approach significantly reduces the build time compared to the standard LT60 strategy, it also considerably deteriorates the AB surface quality. Laser remelting samples produced using LT120 demonstrated an improvement in fatigue life compared to AB reference samples produced using the standard LT60 strategy by up to a factor of 4, while simultaneously reducing the production time by 30 %.

Author Contributions

D. Ordnung: methodology, conceptualization, investigation, writing – original draft; M. Sinico: conceptualization, writing – review & editing; T. Mertens: writing – review & editing; H. Haitjema: writing – review & editing; B. Van Hooreweder: supervision, writing – review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by VLAIO/SIM/ICON HBC.2020.2958 MetaMould and FWO/SB 1SB2324N.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Deceuninck for their support in conducting surface machining of the samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AB |

As-built |

| BD |

Build orientation |

| HB |

Hull-bulk |

| LPBF |

Laser Powder Bed Fusion |

| LR |

Laser remolten |

| LT |

Layer thickness |

| DLPBF |

Dual Laser Powder Bed Fusion |

| EDM |

Electrical Discharge Machined |

| P |

Mechanically polished |

References

- Asnafi, N. Application of Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion for Direct Metal Tooling. Metals 2021, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M. Additive Manufacturing Processes in Medical Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DebRoy, T.; Wei, H.L.; Zuback, J.S.; Mukherjee, T.; Elmer, J.W.; Milewski, J.O.; Beese, A.M.; Wilson-Heid, A.; De, A.; Zhang, W. Additive manufacturing of metallic components – Process, structure and properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elambasseril, J.; Rogers, J.; Wallbrink, C.; Munk, D.; Leary, M.; Qian, M. Laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing (LPBF-AM): the influence of design features and LPBF variables on surface topography and effect on fatigue properties. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2023, 48, 132–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strano, G.; Hao, L.; Everson, R.M.; Evans, K.E. Surface roughness analysis, modelling and prediction in selective laser melting. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2013, 213, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbst, U.; Madia, M.; Klinger, C.; Bettge, D.; Murakami, Y. Defects as a root cause of fatigue failure of metallic components. I: Basic aspects. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 97, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutolo, A.; Elangeswaran, C.; Muralidharan, G.K.; Van Hooreweder, B. On the role of building orientation and surface post-processes on the fatigue life of Ti-6Al-4V coupons manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 840, 142747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Liao, R.; Lu, W. Surface stress concentration factor via Fourier representation and its application for machined surfaces. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2017, 113–114, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, E.; Bagherifard, S.; Bandini, M.; Guagliano, M. Surface post-treatments for metal additive manufacturing: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasa, E.; Kruth, J.-P.; Deckers, J. Manufacturing by combining Selective Laser Melting and Selective Laser Erosion/laser re-melting. CIRP Ann. 2011, 60, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordnung, D.; Metelkova, J.; Cutolo, A.; Van Hooreweder, B. Improving fatigue performance of metal parts with up-facing inclined surfaces produced by laser powder bed fusion and in-situ laser remelting. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 2022, 3, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senol, S.; Cutolo, A.; Ordnung, D.; Datye, A.; Van Hooreweder, B.; Vanmeensel, K. Improved surface quality and fatigue life of high-strength, hybrid particle reinforced (Ti+B4C)/Al-Cu-Mg metal matrix composite processed by dual-laser powder bed fusion. Proc. Struct. Integr. 2024, 53, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinico, M.; Metelkova, J.; Dalemans, T.; Thijs, L.; Van Hooreweder, B. High speed laser powder bed fusion of M789 tool steel with an optimized 120 µm layer thickness approach. In Procedia CIRP; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 113, pp. 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3DSystems. Certified M789 Material. Available online: https://www.3dsystems.com/materials/certified-m789-a (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Tian, Y.; Palad, R.; Aranas, C. Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of a newly designed steel fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, C.; Zunko, H.; Aumayr, C.; Leitner, H.; Kapp, M. Advances in Maraging Steels for Additive Manufacturing. BHM Berg- Hüttenmänn. Monatshefte 2019, 164, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordnung, D.; Mertens, T.; Metelkova, J.; Van Hooreweder, B. Novel strategy for automated quality enhancement of up-facing inclined surfaces by incremental dual laser powder bed fusion. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2024, 178, 108172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 16610-21. Geometrical product specifications (GPS) – Filtration – Part 21: Linear profile filters: Gaussian filters. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- ISO 21920-2. Geometrical product specifications (GPS). Surface texture: Profile – Part 2: Terms, definitions and surface. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- ISO 21920-3. Geometrical product specifications (GPS). Surface texture: Profile – Part 3: Specific operators. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).