Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biosensors and Monitoring Strategies of Fish, Meat, Poultry and Related Product Quality Parameters

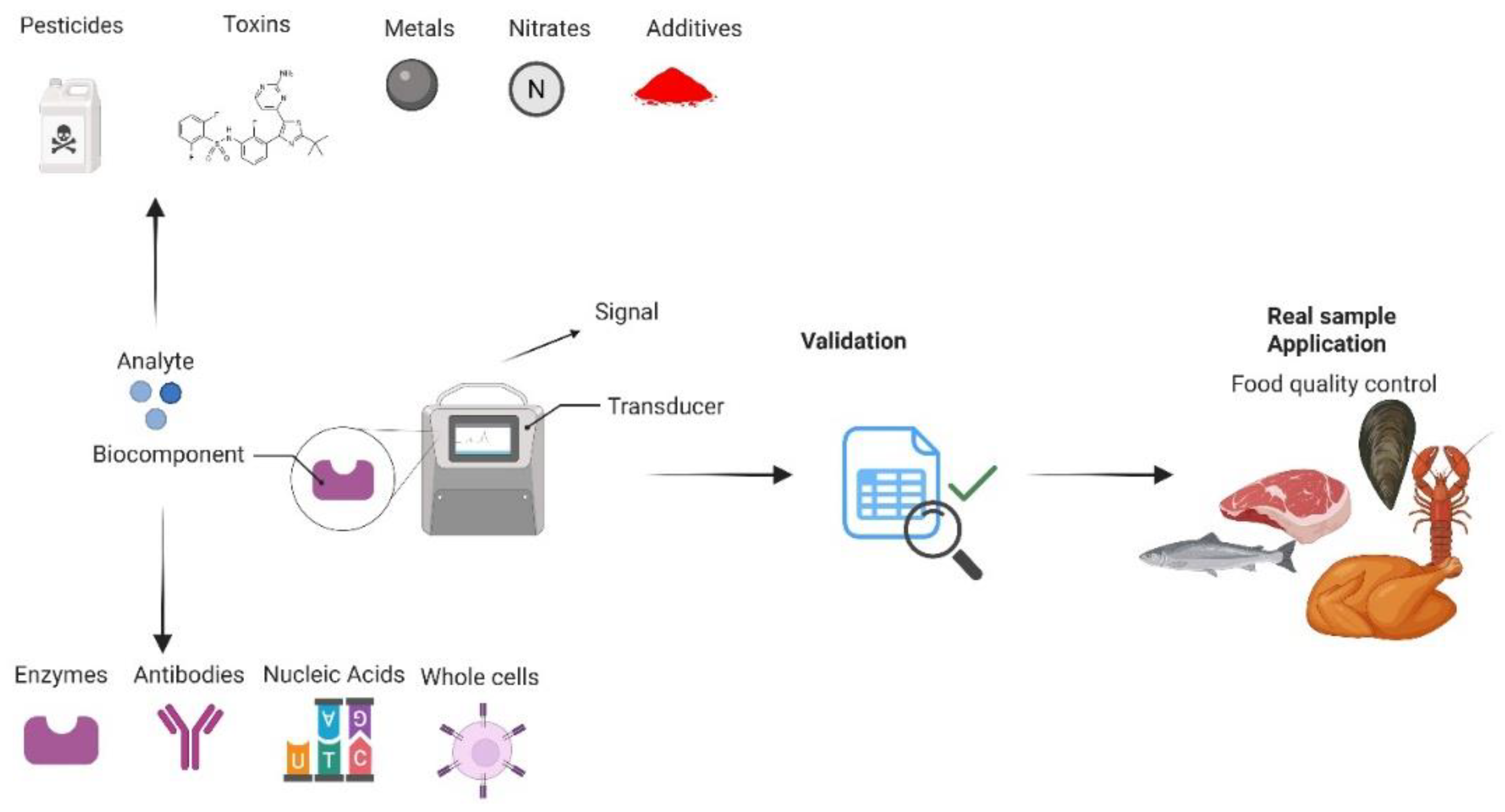

2.1. Biosensor Development Strategies and Mechanism of Sensing

(1)

(1) (2)

(2) (3)

(3) (4)

(4)2.2. Types of Biosensors Employed to Monitor Fish, Meat, Poultry and Related Product Quality Parameters

3. Applications of Biosensors in Real-Time Food Quality Monitoring In Fish, Meat and Meat Products

3.1. Biosensor-Based Detection of Freshness Indicators in Fish, Meat and Meat Products

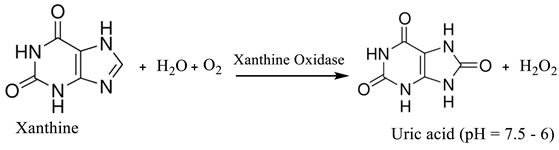

3.1.1. Hypoxanthine

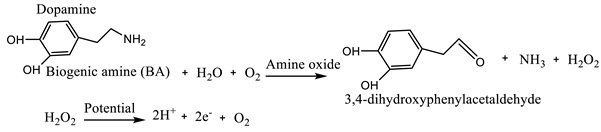

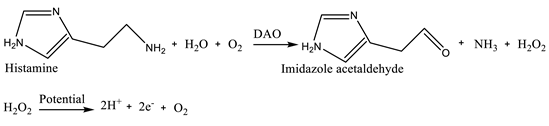

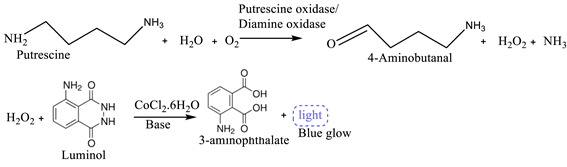

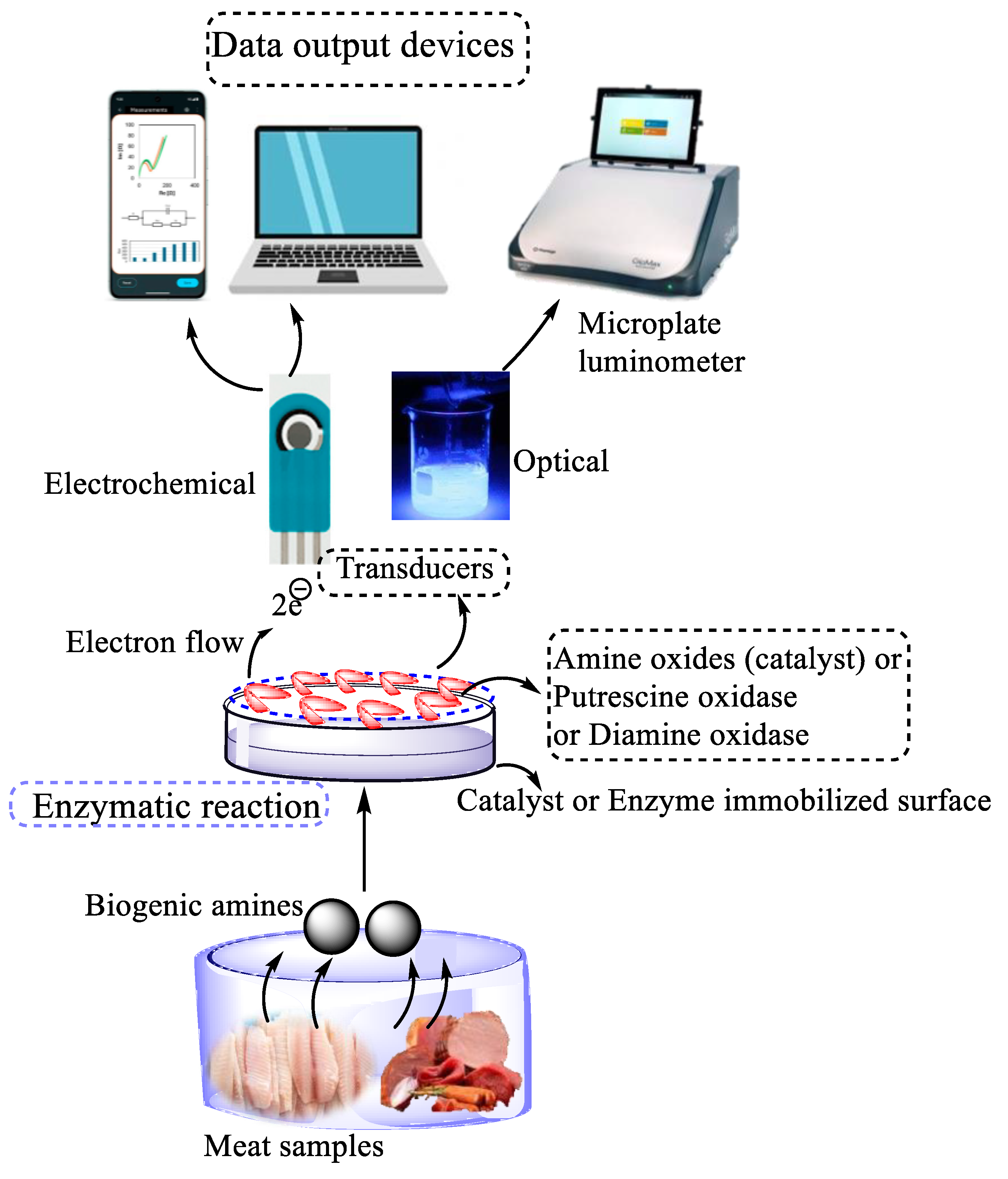

3.1.2. Biogenic Amines and Volatile Amines

3.2. Biosensor-Based Detection of Microbial Hazards in Fish, Meat and Meat Products

3.3. Biosensor-Based Detection of Contaminants, Antibiotics, and Drug Residues in Fish, Meat And Meat Products

4. Standardization and Validation of Biosensors in Real-Time Food Quality Monitoring

4.1. Validation

4.1.1. Specificity and Cross-Reactivity Challenges

4.1.2. Selectivity in Complex Food Matrices

4.1.3. Calibration Curve and Reportable Range

4.1.4. Accuracy and Precision Requirements

4.1.5. Dilution Linearity and High-Dose Hook Effect

4.1.6. Stability Under Analytical Conditions

4.2. Limits and Challenges for Biosensors Application in in Real-Time Food Quality Monitoring

5. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Perspectives in Biosensor Applications for Fish, Meat, Poultry, and Related Products Safety Monitoring

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daramola, O.B.; Omole, R.; Akinsanola, B.A. Emerging applications of biorecognition elements-based optical biosensors for food safety monitoring. Discover Sensors 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinçkaya, E.; Akyilmaz, E.; Sezgintürk, M.K.; Ertaş, F.N. Sensitive nitrate determination in water and meat samples by amperometric biosensor. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010, 40, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Xiao, F.; Bai, J.; Lai, Y.; Hou, J.; Xian, Y.; Jin, L. Label-free immunoassay for chloramphenicol based on hollow gold nanospheres/chitosan composite. Talanta 2011, 87, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohk, S.-H.; Bhunia, A.K. Multiplex fiber optic biosensor for detection of Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica from ready-to-eat meat samples. Food Microbiol. 2013, 33, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.; Fathi, F.; Jalili, R.; Shoeibie, S.; Dastmalchi, S.; Khataee, A.; Rashidi, M.-R. SPR enhanced DNA biosensor for sensitive detection of donkey meat adulteration. Food Chem. 2020, 331, 127163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albelda, J.A.; Uzunoglu, A.; Santos, G.N.C.; Stanciu, L.A. Graphene-titanium dioxide nanocomposite based hypoxanthine sensor for assessment of meat freshness. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 89, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nami, M.; Taheri, M.; Siddiqui, J.; Deen, I.A.; Packirisamy, M.; Deen, M.J. Recent Progress in Intelligent Packaging for Seafood and Meat Quality Monitoring. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegay, Z.T.; Hosseini, E.; Varzakas, T.; Smaoui, S. The latest research progress on polysaccharides-based biosensors for food packaging: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, P.K.; Bhattacharya, D.; Das, J.K.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Ekhlas, D.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Dandapat, P.; Alessandroni, L.; Das, A.K.; Gagaoua, M. Emerging Role of Biosensors and Chemical Indicators to Monitor the Quality and Safety of Meat and Meat Products. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasijevic, I.; Kundacina, I.; Jaric, S.; Pavlovic, Z.; Radovic, M.; Radonic, V. Recent Advances in Biosensor Technologies for Meat Production Chain. Foods 2025, 14, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritea, L.; Tertis, M.; Sandulescu, R.; Cristea, C. Chapter Eleven - Enzyme–Graphene Platforms for Electrochemical Biosensor Design With Biomedical Applications, in Methods in Enzymology, C.V. Kumar, Editor 2018), Academic Press. pp. 293-333. [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wei, X.; Zhang, D.; Huang, L.; Liu, H.; Fang, H. Immobilization of Enzyme Electrochemical Biosensors and Their Application to Food Bioprocess Monitoring. Biosensors 2023, 13, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre, R.; Costa-Rama, E.; Lopes, P.; Nouws, H.P.A.; Delerue-Matos, C. Amperometric enzyme sensor for the rapid determination of histamine. Anal. Methods 2019, 11, 1264–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omanovic-Miklicanin, E.; Valzacchi, S. Development of new chemiluminescence biosensors for determination of biogenic amines in meat. Food Chem. 2017, 235, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, D.; Verma, N. Fibre-optic biosensor for the detection of xanthine for the evaluation of meat freshness. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2020, 1531, 012098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

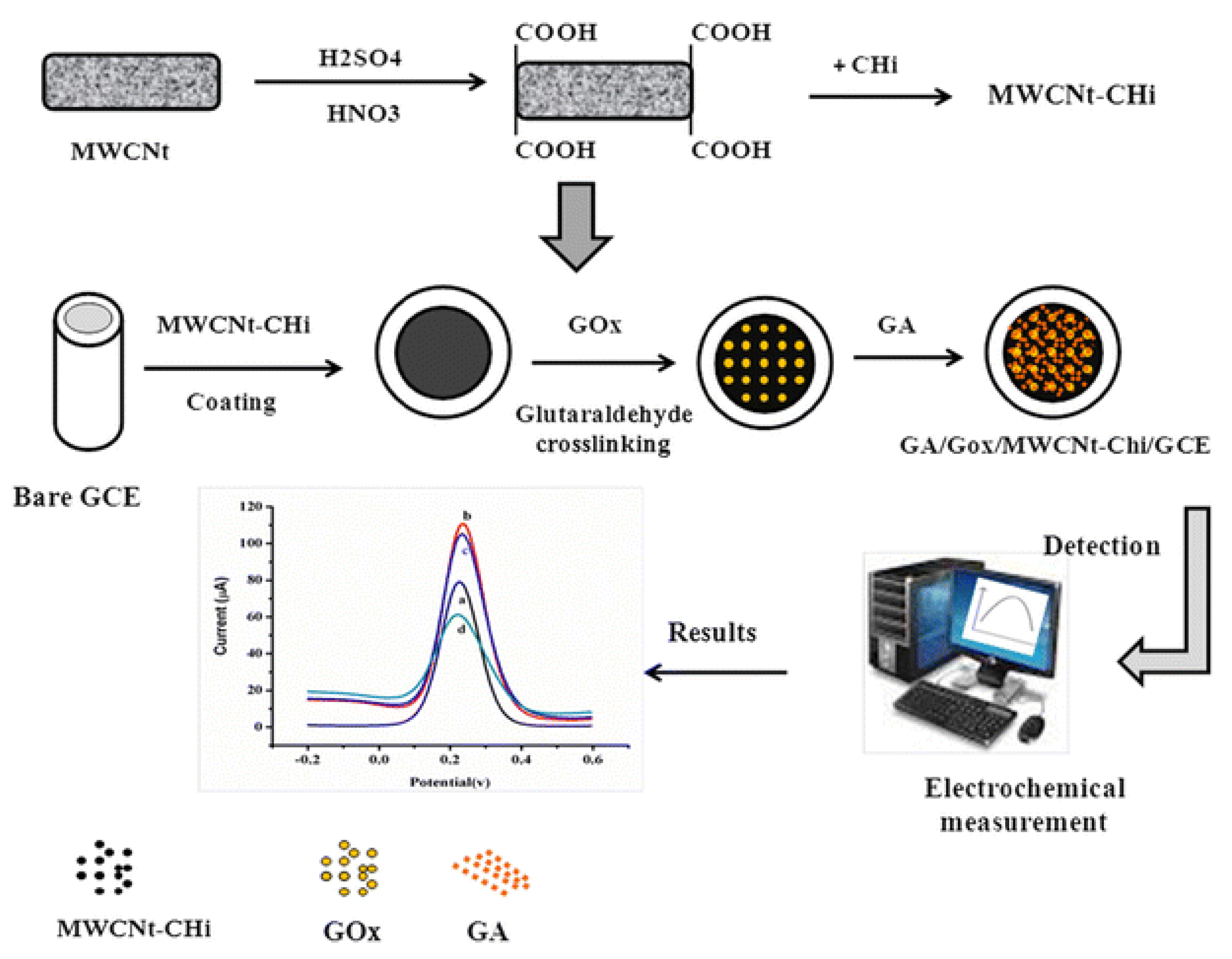

- Uwimbabazi, E.; Mukasekuru, M.R.; Sun, X. Glucose Biosensor Based on a Glassy Carbon Electrode Modified with Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes-Chitosan for the Determination of Beef Freshness. Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-H.; Ma, L. Integrating machine learning, optical sensors, and robotics for advanced food quality assessment and food processing. Food Innov. Adv. 2025, 4, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçoğlu, I.O.; Erden, P.E.; Kılıç, E. Disposable biogenic amine biosensors for histamine determination in fish. Anal. Methods 2020, 12, 3802–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zór, K.; Dymek, K.; Ortiz, R.; Faure, A.M.; Saatci, E.; Gorton, L.; Bardsley, R.; Nistor, M. Indirect, non-competitive amperometric immunoassay for accurate quantification of calpastatin, a meat tenderness marker, in bovine muscle. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, M.; Rapallini, M.; Karp, M.; Elferink, J. Application of a luminescent bacterial biosensor for the detection of tetracyclines in routine analysis of poultry muscle samples. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2010, 27, 1112–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaidan, A.; Barras, A.; Addad, A.; Tahon, J.-F.; Toufaily, J.; Hamieh, T.; Szunerits, S.; Boukherroub, R. Colorimetric sensing of dopamine in beef meat using copper sulfide encapsulated within bovine serum albumin functionalized with copper phosphate (CuS-BSA-Cu3(PO4)2) nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 582, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzini, P.; Manzano, M.; Farre, C.; Meylheuc, T.; Chaix, C.; Ramarao, N.; Vidic, J. Highly sensitive detection of Campylobacter spp. In chicken meat using a silica nanoparticle enhanced dot blot DNA biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 171, 112689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierini, G.D.; Robledo, S.N.; Zon, M.A.; Di Nezio, M.S.; Granero, A.M.; Fernández, H. Development of an electroanalytical method to control quality in fish samples based on an edge plane pyrolytic graphite electrode. Simultaneous determination of hypoxanthine, xanthine and uric acid. Microchem. J. 2018, 138, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; You, S.; Li, C.; Chen, T.; Wang, X. One-Step and Colorimetric Detection of Fish Freshness Indicator Hypoxanthine Based on the Peroxidase Activity of Xanthine Oxidase Grade I Ammonium Sulfate Suspension. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervisevic, M.; Custiuc, E.; Çevik, E.; Durmus, Z.; Şenel, M.; Durmus, A. Electrochemical biosensor based on REGO/Fe3O4 bionanocomposite interface for xanthine detection in fish sample. Food Control. 2015, 57, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lin, Y.; Ma, X.; Guo, L.; Qiu, B.; Chen, G.; Lin, Z. Multicolor biosensor for fish freshness assessment with the naked eye. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2017, 252, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yan, F.; Wu, Y.; Huang, D.; Weng, Z. A fluorescent biosensor based on catalytic activity of platinum nanoparticles for freshness evaluation of aquatic products. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooltongchun, M.; Teepoo, S. A Simple and Cost-effective Microfluidic Paper-Based Biosensor Analytical Device and its Application for Hypoxanthine Detection in Meat Samples. Food Anal. Methods 2019, 12, 2690–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görgülü, M.; Çete, S.; Arslan, H.; Yaşar, A. Preparing a new biosensor for hypoxanthine determination by immobilization of xanthine oxidase and uricase in polypyrrole-polyvinyl sulphonate film. Artif. Cells, Nanomedicine, Biotechnol. 2013, 41, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R.; Yadav, S.; Nehra, R.; Yadav, S.; Pundir, C. Electrochemical biosensor based on gold coated iron nanoparticles/chitosan composite bound xanthine oxidase for detection of xanthine in fish meat. J. Food Eng. 2013, 115, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, S.; Lei, J.; Xu, Q.; Ju, H. Carbon nanospheres enhanced electrochemiluminescence of CdS quantum dots for biosensing of hypoxanthine. Talanta 2011, 85, 2154–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martuscelli, M.; Esposito, L.; Mastrocola, D. Biogenic Amines’ Content in Safe and Quality Food. Foods 2021, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirone, M.; Esposito, L.; D’onofrio, F.; Visciano, P.; Martuscelli, M.; Mastrocola, D.; Paparella, A. Biogenic Amines in Meat and Meat Products: A Review of the Science and Future Perspectives. Foods 2022, 11, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Zou, X.; Shi, J.; Huang, X.; Sun, Z.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Holmes, M.; et al. Amine-responsive bilayer films with improved illumination stability and electrochemical writing property for visual monitoring of meat spoilage. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2020, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-F.; Lin, Z.-Z.; Hong, C.-Y.; Huang, Z.-Y. Colorimetric detection of putrescine and cadaverine in aquatic products based on the mimic enzyme of (Fe,Co) codoped carbon dots. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 1747–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.G.; Gao, W.; Shi, X. Portable functional hydrogels based on silver metallization for visual monitoring of fish freshness. Food Control. 2021, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matindoust, S.; Farzi, A.; Nejad, M.B.; Abadi, M.H.S.; Zou, Z.; Zheng, L.-R. Ammonia gas sensor based on flexible polyaniline films for rapid detection of spoilage in protein-rich foods. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 7760–7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.-Y.; Chuang, M.-Y.; Zan, H.-W.; Meng, H.-F.; Lu, C.-J.; Yeh, P.-H.; Chen, J.-N. One-Minute Fish Freshness Evaluation by Testing the Volatile Amine Gas with an Ultrasensitive Porous-Electrode-Capped Organic Gas Sensor System. ACS Sensors 2017, 2, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, Z.; Shi, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Holmes, M.; Zhang, W.; Zou, X. Titanium dioxide-polyaniline/silk fibroin microfiber sensor for pork freshness evaluation. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2018, 260, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, J.; Wu, M. Nondestructive detection of total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N) content in pork meat by integrating hyperspectral imaging and colorimetric sensor combined with a nonlinear data fusion. LWT 2015, 63, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.; Altemimi, A.B.; Alhelfi, N.; Ibrahim, S.A. Application of Biosensors for Detection of Pathogenic Food Bacteria: A Review. Biosensors 2020, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Sekizuka, T.; Kishi, N.; Yamashita, A.; Kuroda, M. Conventional culture methods with commercially available media unveil the presence of novel culturable bacteria. Gut Microbes 2018, 10, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lin, H.; Wang, L.; Cao, L.; Sui, J.; Wang, K. Optical sensing techniques for rapid detection of agrochemicals: Strategies, challenges, and perspectives. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 838, 156515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, M.; Conrad, N.L.; Conceição, F.R.; Moreira, Â.N.; da Silva, W.P.; Aleixo, J.A.; Bhunia, A.K. Highly specific fiber optic immunosensor coupled with immunomagnetic separation for detection of low levels of Listeria monocytogenes and L. ivanovii. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 275–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhogail, S.; Suaifan, G.A.; Zourob, M. Rapid colorimetric sensing platform for the detection of Listeria monocytogenes foodborne pathogen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 86, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.Y.; Heo, N.S.; Shukla, S.; Cho, H.J.; Vilian, A.E.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.Y.; Han, Y.-K.; Yoo, S.M.; Huh, Y.S. Development of gold nanoparticle-aptamer-based LSPR sensing chips for the rapid detection of Salmonella typhimurium in pork meat. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Liu, Y.; Duan, N.; Wu, S.; Wang, Z.; Xu, B. Gold nanoparticles enhanced SERS aptasensor for the simultaneous detection of Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 74, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.-S.; Park, T.S.; Yoon, J.-Y. Rapid and reagentless detection of microbial contamination within meat utilizing a smartphone-based biosensor. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morant-Miñana, M.C.; Elizalde, J. Microscale electrodes integrated on COP for real sample Campylobacter spp. detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 70, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniandy, S.; Dinshaw, I.J.; Teh, S.J.; Lai, C.W.; Ibrahim, F.; Thong, K.L.; Leo, B.F. Graphene-based label-free electrochemical aptasensor for rapid and sensitive detection of foodborne pathogen. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 6893–6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasooly, A. Surface Plasmon Resonance Analysis of Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B in Food. J. Food Prot. 2001, 64, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jasim, I.; Shen, Z.; Zhao, L.; Dweik, M.; Zhang, S.; Almasri, M. A microfluidic based biosensor for rapid detection of Salmonella in food products. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0216873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turdean, G.L. Design and Development of Biosensors for the Detection of Heavy Metal Toxicity. Int. J. Electrochem. 2011, 2011, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; He, X.; Cui, P.L.; Liu, J.; Bin Li, Z.; Jia, B.J.; Zhang, T.; Wang, J.P.; Yuan, W.Z. Preparation of a chemiluminescence sensor for multi-detection of benzimidazoles in meat based on molecularly imprinted polymer. Food Chem. 2019, 280, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Peng, D.; Xie, S.; Chen, D.; Pan, Y.; Tao, Y.; Yuan, Z. Construction of Electrochemical Immunosensor Based on Gold-Nanoparticles/Carbon Nanotubes/Chitosan for Sensitive Determination of T-2 Toxin in Feed and Swine Meat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Tang, J.; Su, B.; Chen, G. Ultrasensitive Electrochemical Immunoassay of Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B in Food Using Enzyme-Nanosilica-Doped Carbon Nanotubes for Signal Amplification. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 10824–10830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Guan, C.; Wen, Y.; Zhong, X.; Yuan, L. Multi-hole fiber based surface plasmon resonance sensor operated at near-infrared wavelengths. Opt. Commun. 2014, 313, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, T.; Baxter, A.; Ferguson, J.; Haughey, S.; Bjurling, P. Multi sulfonamide screening in porcine muscle using a surface plasmon resonance biosensor. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 529, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Oliver, R.; Aguilar, M.-I.; Wu, Y. Surface Plasmon Resonance Assay for Chloramphenicol. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 8329–8333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad-Razdari, A.; Ghasemi-Varnamkhasti, M.; Izadi, Z.; Rostami, S.; Ensafi, A.A.; Siadat, M.; Losson, E. Detection of sulfadimethoxine in meat samples using a novel electrochemical biosensor as a rapid analysis method. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, H.S.; Shetty, S.S.; Thomas, N.J.; Dhamu, V.N.; Bhide, A.; Prasad, S. Ultrasensitive and Rapid-Response Sensor for the Electrochemical Detection of Antibiotic Residues within Meat Samples. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 6324–6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baş, S.Z.; Gülce, H.; Yildiz, S. Hypoxanthine Biosensor Based on Immobilization of Xanthine Oxidase on Modified Pt Electrode and Its Application for Fish Meat. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2014, 63, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xin, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L.; Xia, X.; Tong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L.; Wang, W. Novel affinity purification of xanthine oxidase from Arthrobacter M3. J. Chromatogr. B 2012, 906, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erol, E.; Yildirim, E.; Cete, S. Construction of biosensor for hypoxanthine determination by immobilization of xanthine oxidase and uricase in polypyrrole-paratoluenesulfonate film. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2020, 24, 1695–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.C.; Ghica, M.E.; Brett, C.M.A. Design of a new hypoxanthine biosensor: xanthine oxidase modified carbon film and multi-walled carbon nanotube/carbon film electrodes. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 405, 3813–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.; Andreescu, S. Paper-Based Enzyme Biosensor for One-Step Detection of Hypoxanthine in Fresh and Degraded Fish. ACS Sensors 2020, 5, 4092–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratcher, C.; Grant, S.; Vassalli, J.; Lorenzen, C. Enhanced efficiency of a capillary-based biosensor over an optical fiber biosensor for detecting calpastatin. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2008, 23, 1674–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.A.B.; Grazhdan, D.; Fiutowski, J.; Nebling, E.; Blohm, L.; Lofink, F.; Rubahn, H.-G.; Hansen, R.d.O. Meat and fish freshness evaluation by functionalized cantilever-based biosensors. Microsyst. Technol. 2019, 26, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zór, K.; Castellarnau, M.; Pascual, D.; Pich, S.; Plasencia, C.; Bardsley, R.; Nistor, M. Design, development and application of a bioelectrochemical detection system for meat tenderness prediction. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 4283–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. , Chai, C., & Yao, B., Rapid evaluation of Salmonella pullorum contamination in chicken based on a portable amperometric sensor. J. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 137, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Helali, S.; Alatawi, A.S.E.; Abdelghani, A. Pathogenic Escherichia coli biosensor detection on chicken food samples. J. Food Saf. 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Bhunia, A.K. Cell-based biosensor for rapid screening of pathogens and toxins. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J.; Baxter, A.; Young, P.; Kennedy, G.; Elliott, C.; Weigel, S.; Gatermann, R.; Ashwin, H.; Stead, S.; Sharman, M. Detection of chloramphenicol and chloramphenicol glucuronide residues in poultry muscle, honey, prawn and milk using a surface plasmon resonance biosensor and Qflex® kit chloramphenicol. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 529, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-Y.; Huang, P.; Wu, F.-Y. A label-free colorimetric aptasensor based on controllable aggregation of AuNPs for the detection of multiplex antibiotics. Food Chem. 2020, 304, 125377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Zheng, H.; Li, X.-Q.; Yuan, X.-X.; Li, H.; Deng, L.-G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.-Z.; Yang, G.-S.; Meng, M.; et al. Detection of ractopamine residues in pork by surface plasmon resonance-based biosensor inhibition immunoassay. Food Chem. 2012, 130, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yao, C.; Li, Z. Microarray-based chemical sensors and biosensors: Fundamentals and food safety applications. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanholo, P.V.; Sgobbi, L.F. Chapter 4 - Validation of biosensors, in Biosensors in Precision Medicine, L.C. Brazaca and J.R. Sempionatto, Editors(2024), Elsevier. pp. 105-131. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, H.; Song, G.; Huang, K.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Q.; He, X.; Cheng, N. Intelligent biosensing strategies for rapid detection in food safety: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 202, 114003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.D.Á.; Gomes, R.S.; de Carvalho, A.M.; Lima, E.M.F.; Pinto, U.M.; da Cunha, L.R. Revolutionizing food safety with electrochemical biosensors for rapid and portable pathogen detection. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 2511–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, S.A.; Uslu, B.; Sezgintürk, M.K. Biosensors; Taylor & Francis: London, United Kingdom, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S. Advancements in food quality monitoring: integrating biosensors for precision detection. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 976–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indyk, H.E.; Woollard, D.C. Single laboratory validation of an optical biosensor method for the determination of folate in foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2013, 29, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, H.; Scherbaum, E.; Anastassiades, M.; Vorlová, S.; Schmid, R.D.; Bachmann, T.T. Development, validation, and application of an acetylcholinesterase-biosensor test for the direct detection of insecticide residues in infant food. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2002, 17, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.S.; Ragavan, K.V. Biosensors in food processing. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 50, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meliana, C.; Liu, J.; Show, P.L.; Low, S.S. Biosensor in smart food traceability system for food safety and security. Bioengineered 2024, 15, 2310908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijayanti, S.D.; Tsvik, L.; Haltrich, D. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Enzyme-Based Biosensors for Food and Beverage Analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curulli, A. Electrochemical Biosensors in Food Safety: Challenges and Perspectives. Molecules 2021, 26, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inês, A.; Cosme, F. Biosensors for Detecting Food Contaminants—An Overview. Processes 2025, 13, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Liu, Y.; Geng, J.; Kou, X.; Xin, Z.; Yang, D. Engineering nanomaterials-based biosensors for food safety detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 106, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesche, C.; Baeumner, A.J. Biosensors to support sustainable agriculture and food safety. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Q.; Wang, L.; Ahmad, W.; Rong, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Q. A highly sensitive detection of carbendazim pesticide in food based on the upconversion-MnO2 luminescent resonance energy transfer biosensor. Food Chem. 2021, 349, 129157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, G.; Zheng, S.; Han, S.; Liang, S.; Lin, Y. Collaborative Light-off and Light-on Bacterial Luciferase Biosensors: Innovative Approach for Rapid Contaminant Detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 280, 117369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadán, F.; Aristoy, M.-C.; Toldrá, F. Biosensor Based on Immobilized Nitrate Reductase for the Quantification of Nitrate Ions in Dry-Cured Ham. Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 3481–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Guo, H.; Chen, H.; Zou, B.; Yang, C.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Sun, M.; Wang, L. A Rapid and Sensitive Aptamer-Based Biosensor for Amnesic Shellfish Toxin Domoic Acid. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonfría, E.S.; Vilariño, N.; Campbell, K.; Elliott, C.; Haughey, S.A.; Ben-Gigirey, B.; Vieites, J.M.; Kawatsu, ✗. K.; Botana, L.M. Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning Detection by Surface Plasmon Resonance-Based Biosensors in Shellfish Matrixes. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 6303–6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, N.; Sakthivel, R.; Karthik, C.S.; Lin, Y.-C.; Liu, X.; Wen, H.-W.; Yang, W.; Chung, R.-J. Polydopamine-modified 3D flower-like ZnMoO4 integrated MXene-based label-free electrochemical immunosensor for the food-borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes detection in milk and seafood. Talanta 2024, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadır, E.B.; Sezgintürk, M.K. Applications of commercial biosensors in clinical, food, environmental, and biothreat/biowarfare analyses. Anal. Biochem. 2015, 478, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, R.; Suni, I.I.; Bever, C.S.; Hammock, B.D. Impedance Biosensors: Applications to Sustainability and Remaining Technical Challenges. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yibar, A.; Ajmi, N.; Duman, M. First report and genomic characterization of Escherichia coli O111:H12 serotype from raw mussels in Türkiye. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Long, F.; Chen, W.; Chen, J.; Chu, P.K.; Wang, H. Fundamentals and applications of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy–based biosensors. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 13, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boodhoo, N.; Doost, J.S.; Sharif, S. Biosensors for Monitoring, Detecting, and Tracking Dissemination of Poultry-Borne Bacterial Pathogens Along the Poultry Value Chain: A Review. Animals 2024, 14, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masdor, N.A.; Altintas, Z.; Tothill, I.E. Surface Plasmon Resonance Immunosensor for the Detection of Campylobacter jejuni. Chemosensors 2017, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, C. Recent Progress in Aptamer-Based Functional Probes for Bioanalysis and Biomedicine. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2016, 22, 9886–9900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, W.C.; Beni, V.; Turner, A.P. Lateral-flow technology: From visual to instrumental. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 79, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Thakur, D.; Kumar, D. Novel Enzymatic Biosensor Utilizing a MoS2/MoO3 Nanohybrid for the Electrochemical Detection of Xanthine in Fish Meat. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 31962–31971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaway, T.R.; Lillehoj, H.; Chuanchuen, R.; Gay, C.G. Alternatives to Antibiotics: A Symposium on the Challenges and Solutions for Animal Health and Production. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxminarayan, R.; Duse, A.; Wattal, C.; Zaidi, A.K.M.; Wertheim, H.F.L.; Sumpradit, N.; Vlieghe, E.; Hara, G.L.; Gould, I.M.; Goossens, H.; et al. Antibiotic resistance—the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 1057–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlet, J. The gut is the epicentre of antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2012, 1, 39–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Er, B.; Onurdağ, F.K.; Demirhan, B.; Özgacar, S.Ö.; Öktem, A.B.; Abbasoğlu, U. Screening of quinolone antibiotic residues in chicken meat and beef sold in the markets of Ankara, Turkey. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 2212–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, P.; Li, M.; Wang, W.; Yang, L.; Yang, Y. Ochratoxin A: its impact on poultry gut health and microbiota, an overview. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, M.; Diaz, G. Microsomal and cytosolic biotransformation of aflatoxin B1 in four poultry species. Br. Poult. Sci. 2006, 47, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manessis, G.; Gelasakis, A.I.; Bossis, I. Point-of-Care Diagnostics for Farm Animal Diseases: From Biosensors to Integrated Lab-on-Chip Devices. Biosensors 2022, 12, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T.N.D.; Nguyen, H.A.; Thi, N.P.A.; Nam, N.N.; Tran, N.K.S.; Trinh, K.T.L. Biosensors for Seafood Safety Control—A Review. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Sun, Z.; Guo, Q.; Weng, X. Microfluidic thread-based electrochemical aptasensor for rapid detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 182, 113191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalonga, A.; Sánchez, A.; Mayol, B.; Reviejo, J.; Villalonga, R. Electrochemical biosensors for food bioprocess monitoring. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Moreno-Guzman, M.; Jurado, B.; Escarpa, A. Chapter 9 - Food Microfluidics Biosensors, in Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, V. Scognamiglio, G. Rea, F. Arduini, and G. Palleschi, Editors(2016), Elsevier. pp. 273-312. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.-Q.; Ge, L. Colorimetric Sensors: Methods and Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 9887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, H. Chromogenic Mechanisms of Colorimetric Sensors Based on Gold Nanoparticles. Biosensors 2023, 13, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.; Ju, P.; Bi, F.; Wen, S.; Xiang, Z.; Chen, J.; Qiu, M. A smartphone-assisted ultrasensitive colorimetric aptasensor based on DNA-encoded porous MXene nanozyme for visual detection of okadaic acid. Food Chem. 2024, 464, 141776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda, A.; Michelini, E.; Zangheri, M.; Di Fusco, M.; Calabria, D.; Simoni, P. Smartphone-based biosensors: A critical review and perspectives. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 79, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, C.; Ma, X. Sensitive SERS aptasensor for histamine detection based on Au/Ag nanorods and IRMOF-3@Au based flexible PDMS membrane. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1288, 342147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Dang, H.; Moon, J.-I.; Kim, K.; Joung, Y.; Park, S.; Yu, Q.; Chen, J.; Lu, M.; Chen, L.; et al. SERS-based microdevices for use as in vitro diagnostic biosensors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 5394–5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, N.; Saxena, K.; Rawal, R.; Yadav, L.; Jain, U. Advances in surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy-based sensors for detection of various biomarkers. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2023, 184, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, F.; Ghazali, K.H.; Fen, Y.W.; Meriaudeau, F.; Jose, R. Biosensing through surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy: A review on the role of plasmonic nanoparticle-polymer composites. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-Y.; Zhu, J.; Weng, G.-J.; Li, J.-J.; Zhao, J.-W. Fabrication of SERS composite substrates using Ag nanotriangles-modified SiO2 photonic crystal and the application of malachite green detection. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 318, 124472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Li, H.; Yin, M.; Yang, D.; Xiao, F.; Tammina, S.K.; Yang, Y. Fluorescence-SERS dual-mode for sensing histamine on specific binding histamine-derivative and gold nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 273, 121047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindran, N.; Kumar, S.; M, Y.; S, R.; A, M.C.; S, N.T.; K, S.C. Recent advances in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensors for food analysis: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 63, 1055–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Qi, Q.; Wang, C.; Qian, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors for food allergen detection in food matrices. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 142, 111449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Esmaelpourfarkhani, M.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Abnous, K.; Alibolandi, M. Chapter 22 -Application of nanosensors for food safety, in Nanosensors for Smart Cities, B. Han, V.K. Tomer, T.A. Nguyen, A. Farmani, and P. Kumar Singh, Editors(2020), Elsevier. pp. 369-386. [CrossRef]

- Prodromidis, M.I. Impedimetric immunosensors—A review. Electrochimica Acta 2010, 55, 4227–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosona, T.; Gebresenbet, G. Food traceability as an integral part of logistics management in food and agricultural supply chain. Food Control 2013, 33, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, F.; Abdillah, A.N.; Shivanand, P.; Ahmed, M.U. CeO2 nanozyme mediated RPA/CRISPR-Cas12a dual-mode biosensor for detection of invA gene in Salmonella. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 247, 115940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, L. Ultrasensitive and Rapid Visual Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Based on RAA-CRISPR/Cas12a System. Biosensors 2023, 13, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Y.; Tuck, O.T.; Skopintsev, P.; Soczek, K.M.; Li, G.; Al-Shayeb, B.; Zhou, J.; Doudna, J.A. Genome expansion by a CRISPR trimmer-integrase. Nature 2023, 618, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtar, L.G.; Aranda, P.; Messina, G.A.; Nazareno, M.A.; Pereira, S.V.; Raba, J.; Bertolino, F.A. Amperometric biosensor based on laccase immobilized onto a nanostructured screen-printed electrode for determination of polyphenols in propolis. Microchem. J. 2019, 144, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Ji, J.; Sun, Z.; Shen, P.; Sun, X. Recent advances in electrochemical biosensors for antioxidant analysis in foodstuff. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Neethirajan, S. Ensuring food safety: Quality monitoring using microfluidics. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 65, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonu; Chaudhary, V. A Paradigm of Internet-of-Nano-Things Inspired Intelligent Plant Pathogen-Diagnostic Biosensors. ECS Sensors Plus 2022, 1, 031401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyarathna, I.R.; Rajakaruna, R.; Karunaratne, D.N. The rise of inorganic nanomaterial implementation in food applications. Food Control. 2017, 77, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Kaur, G. Chapter 2 - Trends on Biosensing Systems for Heavy Metal Detection, in Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, V. Scognamiglio, G. Rea, F. Arduini, and G. Palleschi, Editors(2016), Elsevier. pp. 33-71. [CrossRef]

- Pawar, D.; Presti, D.L.; Silvestri, S.; Schena, E.; Massaroni, C. Current and future technologies for monitoring cultured meat: A review. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO, Food Safety Aspects of Cell-Based Food—Background Document Two: Generic Production Process, FAO, Editor.(2022), FAO: Rome.

- Dudefoi, W.; Villares, A.; Peyron, S.; Moreau, C.; Ropers, M.-H.; Gontard, N.; Cathala, B. Nanoscience and nanotechnologies for biobased materials, packaging and food applications: New opportunities and concerns. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 46, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Sun, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, J.; Dong, S. Recent development of biofuel cell based self-powered biosensors. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 3393–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, Q. Biosensors and bioelectronics on smartphone for portable biochemical detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 75, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Imani, S.; de Araujo, W.R.; Warchall, J.; Valdés-Ramírez, G.; Paixao, T.R.L.C.; Mercier, P.P.; Wang, J. Wearable salivary uric acid mouthguard biosensor with integrated wireless electronics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 74, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Kannan, P.; Natarajan, B.; Maiyalagan, T.; Subramanian, P.; Jiang, Z.; Mao, S. MnO2 cacti-like nanostructured platform powers the enhanced electrochemical immunobiosensing of cortisol. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2020, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, M.; Morales, J.; Vizcaíno, E.; Murillo, J.A.; Klauke, T.; Petersen, B.; Piñeiro, C. The use of acute phase proteins for monitoring animal health and welfare in the pig production chain: The validation of an immunochromatographic method for the detection of elevated levels of pig-MAP. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. Recent advances in wearable sensors for animal health management. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2017, 12, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, K.J.; Boeras, D.I.; Chen, X.-S.; Ramsay, A.R.; Peeling, R.W. REASSURED diagnostics to inform disease control strategies, strengthen health systems and improve patient outcomes. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 4, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Chavalarias, D.; Panahi, M.; Yeh, T.; Takimoto, K.; Mizoguchi, M. Mobile-based traceability system for sustainable food supply networks. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelbasset, W.K.; Savina, S.V.; Mavaluru, D.; Shichiyakh, R.A.; Bokov, D.O.; Mustafa, Y.F. Smartphone based aptasensors as intelligent biodevice for food contamination detection in food and soil samples: Recent advances. Talanta 2022, 252, 123769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, T.; Shen, Y.; Li, H. A High-Performance Self-Supporting Electrochemical Biosensor to Detect Aflatoxin B1. Biosensors 2022, 12, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Lu, L.; Gao, F.; He, S.-J.; Zhao, H.-J.; Fang, Y.; Yang, J.-M.; An, Y.; Ye, Z.-W.; Dong, Z. Integration of Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain, and Wearable Technology for Chronic Disease Management: A New Paradigm in Smart Healthcare. Curr. Med Sci. 2021, 41, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, Food safety.(2022, May 19), WHO.

- Chen, S.; Brahma, S.; Mackay, J.; Cao, C.; Aliakbarian, B. The role of smart packaging system in food supply chain. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ye, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, J.; Pang, R.; Xue, L.; Wang, J.; Zeng, H.; Wu, S.; et al. An ultrasensitive CRISPR/Cas12a based electrochemical biosensor for Listeria monocytogenes detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 179, 113073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Peng, L.; Yin, L.; Liu, G.; Man, S. CRISPR-Cas12a-Powered Dual-Mode Biosensor for Ultrasensitive and Cross-validating Detection of Pathogenic Bacteria. ACS Sensors 2021, 6, 2920–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xu, X.; Song, Y.; Huang, J.; Xu, H. Research progress of nanozymes in colorimetric biosensing: Classification, activity and application. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, B.; Tu, H.; Pan, C.; Chai, Y.; Chen, W. Advances in colorimetric biosensors of exosomes: novel approaches based on natural enzymes and nanozymes. Nanoscale 2023, 16, 1005–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Wang, M.; Liu, G.; Ping, J. Nanozyme-based biosensor for organophosphorus pesticide monitoring: Functional design, biosensing strategy, and detection application. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Luo, X.; Lin, W.; Li, Z.; Huang, J. Silver nanoparticles deposited carbon microspheres nanozyme with enhanced peroxidase-like catalysis for colorimetric detection of Hg2+ in seafood. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Lin, X.; Wu, J.; Ying, D.; Duan, N.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S. Multifunctional magnetic composite nanomaterial for Colorimetric-SERS Dual-Mode detection and photothermal sterilization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayerdurai, V.; Cieplak, M.; Kutner, W. Molecularly imprinted polymer-based electrochemical sensors for food contaminants determination. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.A.; Rahmawati, F.; Jamal, J.A.; Ibrahim, S.; Said, M.M.; Ahmad, M.S. Inspecting Histamine Isolated from Fish through a Highly Selective Molecularly Imprinted Electrochemical Sensor Approach. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 13352–13361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.-J.; Chang, B.-W.; Wu, C.-C.; Chen, C.-J.; Chang, H.-C. A new method for detection of endotoxin on polymyxin B-immobilized gold electrodes. Electrochem. Commun. 2007, 9, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Lin, M.; Lee, H.; Cho, M.; Choe, W.-S.; Lee, Y. Determination of endotoxin through an aptamer-based impedance biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 32, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek-Sutherland, J.Z.; Vu, D.M.; Noormohamed, A.; Mendez, H.M.; Stromberg, L.R.; Pedersen, C.A.; Hengartner, A.C.; Klosterman, K.E.; Bridgewater, H.A.; Otieno, V.; et al. Direct detection of bacteremia by exploiting host-pathogen interactions of lipoteichoic acid and lipopolysaccharide. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; He, Y.; Wu, Z. Design of a Blockchain-Enabled Traceability System Framework for Food Supply Chains. Foods 2022, 11, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, F.; Othman, A.; Andreescu, S. Cerium oxide-based hypoxanthine biosensor for Fish spoilage monitoring. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2021, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Yang, R.; Yu, L.; Du, Q.; Ge, A.; Liu, C.; Chi, Z. Improved triple-module fluorescent biosensor for the rapid and ultrasensitive detection of Campylobacter jejuni in livestock and dairy. Food Control. 2022, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Terry, L.R.; Guo, H. A surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy based smart Petri dish for sensitive and rapid detection of bacterial contamination in shrimp. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, Y.; Pi, F. Sensitive and reproducible gold nanostar@metal–organic framework-based SERS membranes for the online monitoring of the freshness of shrimps. Anal. 2023, 148, 2081–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of biosensor | Target Analyte | Source of analyte | Bioreceptor | Transducer/ Electrode | Data visualization device | Measured value | Reference |

| Enzyme-based biosensors | Histamine | Fish | Diamine oxidase (DAO) or monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzymes | Electrochemical Screen printed carbon electrodes |

cyclic voltammetry (CV), chronoamperometry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) | 8.957x10-2 mM | [18] |

| Hypoxanthine | Pork meat | Xanthine oxidase | Electrochemical Platinum wire as counter electrode |

Thermogravimetric Analysis |

111.3 µM at 7 days | [6] | |

| Putrescine | Beef, pork, chicken, turkey and fish meat | Putrescine oxidase |

Electrochemical |

Chemiluminescence Microplate luminometer |

0.8 – 2 mg/L | [14] | |

| Xanthine | Chicken meat | Guanine deaminase and Xanthine oxidase | Electrochemical with fibre optic probe |

Spectrometer (OceanOptics) | 44 µM at 5 days | [15] | |

| Nitrate | Meat sample | Nitrate reductase | Ag/AgCl reference electrode and platinum auxiliary electrode and working electrode glassy carbon (GCE) | Voltammetric analysis | Detection limit: 2.2 × 10–9 M and limit of quantification: 5.79 x10-9 M | [2] | |

| Glucose reduction | Glucose oxidase | Beef meat | Glassy carbon electrode modified with multi-walled carbon nanotubes and chitosan | Cyclic voltammetry (CV), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) | Reduction in glucose from 0.01-0.06 mmol/L | [16] | |

| Immunosensors | Chloramphenicol | Beef and pork meat samples | Monoclonal antibody to CAP (anti-CAP) | Electrochemical immunosensor; Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy technique | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS | Detection limit: 0.06 ng/mL | [3] |

| Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli | Ready-to-eat beef, chicken and turkey breast meat | Alexa Fluor 647-labeled monoclonal antibodies | Streptavidin coated optical waveguides | Fluorometer | Detection limit: 103 CFU/mL | [4] | |

| Calpastatin | Beef meat | Primary anti-calpastain antibody and secondary enzyme-labelled antibody | Potentiostat–galvanostat with Gold working (W.E.) and counter (C.E.) electrodes silver pseudo-reference electrode |

Amperometric detection |

481 ng/mL | [19] | |

| Tetracycline | Poultry muscle samples | Lyophilized reconstituted sensor cells | Cell-biosensor | Bioluminescence with SynergyTM HT Multi-detection Microplate Reader | Sensitivity: 10 µg/kg | [20] | |

| DNA-based biosensors | DNA (Donkey meat) | Donkey adulteration in cooked sausages | DNA | Multi-parameter SPR device with gold chips | Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) | Detection limit: 1.0 nM | [5] |

| Dopamine Adulterant | Beef meat | Anti-dopamine substance | - | Colorimetric sensor | Detection limit: 0.13 mM | [21] | |

| Bacteria (Campylobacter spp.) | Chicken meat | Genomic Campylobacter DNA |

Paper membrane, and biotinylated-DNA detection probe | Chemiluminescent read-out | 3 pg/µL of DNA Detection limit | [22] |

| Analyte | Employed electrode and material of detection | Immobilization Technique | Food product | LOD | Sensitivity/linear range/ detection time | References |

| Some examples for biosensors detecting freshness of fish, meat and meat products. | ||||||

| Hx | XOD within a Nafion matrix on a graphene–titanium dioxide | Entrapment | Pork | 9.5 μM | Sensitivity: 4.1 nA/μM Linear range 20–512 μM |

[6] |

| XOD and horseradish peroxidase | Adsorption | Raw and treated meat samples | 1.8 mg/L | Quantitative limit: 6.1 mg L−1 | [28] | |

| XOD and polyvinylferrocenium perchlorate matrix on a platinum | Adsorption | Fish | 0.6 μM, | Linear range 2.1–103 μM | [62] | |

| XOD and platinum electrode with single-walled carbon nanohorns (SWCsNH) and gold nanoparticles (AuNP) | Covalent | Fish | 0.61 | Linear range 1.5–35.4 | [63] | |

| XOD and uricase within a polypyrrole-paratoluenesulfonate composite film | Entrapment | Fish | 5 | 5-500 Linear range | [64] | |

| XOD on carbon film electrodes and carbon nanotube | Cross-linking | Fish | 0.77 | 10-130 | [65] | |

| XOD onto a modified platinum electrode surface. | Entrapment | Seafood | 0.0023 | 0.01–10 | [64] | |

| XOD onto paper substrate | Adsorption | Fish | 4.1 | 4–35 | [66] | |

| Calpastatin | Capillary and optical fiber biosensor | Covalent | Longissimus muscle from beef | Calpastatin activity (R2 = 0.6058) | [67] | |

| Cadaverine | Receptor molecules onto the surface of thiol-gold | Covalent | Beef, chicken, or pork | [68] | ||

| Putrescine | Casein onto the electrode surface using glutaraldehyde | Covalent | Beef, pork, chicken, turkey meat samples | LOD: 0.8 mg/L–1.3 mg/L | Linearity range: 1–2 mg/L | [69] |

| TVB-N | pre-fabricated responsive dyes, embedded onto a paper or polymer film | Adsorption | Pork meat | Correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.932) | [40] | |

| Some examples for biosensors detecting pathogen microorganisms and toxins in meat and meat products | ||||||

| Campylobacter spp. | Amino-modified DNA probes onto a nylon membrane | Covalent | Chicken meat | LOD: 3 pg/μL of DNA | - | [22] |

| Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli O157:H7 | antibodies onto the optical fiber surface using carbodiimide | Covalent | Beef, turkey breast and chicken | LOD: 103 CFU/mL | - | [4] |

|

SalmonellaTyphimurium Staphyloccocus aureus |

Thiol-modified aptamers onto gold nanoparticles | Non-covalent | Pork | 15 CFU/mL 35 CFU/mL |

Recovery rate: 94.12%–108.33% | [47] |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | Amine-terminated DNA aptamers onto a carboxyl-functionalized graphene-modified electrode employing carbodiimide | Covalent | Chicken meat | LOD: 1 CFU/mL | Linear range (detection): 1–8 log CFU/mL | [50] |

| Salmonella pullorum | specific antibodies onto the electrode surface using glutaraldehyde | Covalent | Chicken meat | LOD: 100 CFU/mL | Detection time: 1.5 to 2 h | [70] |

| E coli K-12 | specific antibodies onto the gold electrode surface. | Adsorption | Chicken meat | LOD: 3 log CFU/mL | - | [71] |

|

Listeria monocytogenes |

thiol-modified DNA aptamers onto gold nanoparticles | Covalent | Meat samples | LOD: 2 log CFU/g | Linear detection range : From 10² to 10⁷ CFU/m Detection time <30 minutes |

[45] |

|

L. monocytogenes toxin S. aureus enterotoxin B |

live mammalian cells onto the surface of gold interdigitated microelectrodes | Adsorption | Salami | 10⁴ CFU/mL 100 ng/mL | Detection time <1 hour | [72] |

| Staphylococcal enterotoxin B | anti-SEB antibodies onto a gold-coated SPR | Covalent | Meat | 0.5 ng/mL | 0.5 ng/mL to 20 ng/mL Detection time <20min |

[51] |

| TrichotheceneT-2 toxin | Anti-T-2 toxin antibodies onto a modified electrode surface using glutaraldehyde | Covalent | Swine meat | 0.04 ng/mL | 0.05 – 20 ng/mL Detection time = 30 min |

[55] |

| Some examples for biosensors detecting antibiotics, drug residues, and additives in meat products | ||||||

| Tetracyclines | E. colicells in agarose gel on the surface of microplates or membrane | Entrapment | Poultry muscle samples | 2–5 µg/kg | 2 to 100 µg/kg. Detection time = 3Hours |

[20] |

| Chloramphenicol (CAP) | CAP–protein conjugate onto the SPR sensor chip | Covalent | Poultry muscle | 100 ng/kg | to 1 µg/kg detection time <30 min |

[73] |

|

Oxytetracycline (OTC) Kanamycin (KAN) Ampicillin (AMP) |

aptamers onto citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles | Adsorption | Chicken |

0.42 ng/mL 0.31 ng/mL0.28 ng/mL |

1–100 ng/mL 1–80 ng/mL 1–60 ng/mL Detection time = 15 min |

[74] |

| Ractopamine | ractopamine–BSA conjugate onto a carboxymethylated dextran chip | Covalent | Pork | 0.09 ng/mL | 0.1 – 10 ng/mL Detection time = 10 min |

[75] |

| Parameter | Definition | Regulatory Expectation | Biosensor-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Ability to detect only the target analyte, not structurally similar compounds | Interference from related compounds should result in <LLOQ signal; accuracy ±25% at extremes | Biosensors using antibodies/aptamers must be screened against analogs, metabolites, and additives |

| Selectivity | Differentiation of analyte in presence of matrix components | ≥80% of blank matrices should show <LLOQ signal; accuracy within ±25% at LLOQ | Must account for interference from fats, enzymes, or proteins common in food matrices |

| LOD (Limit of Detection) | Lowest concentration distinguishable from blank with confidence | typically signal/noise (S/N) ≥3 | Important for contaminant detection; impacted by sensor noise and baseline stability |

| LOQ (Limit of Quantification) | Lowest concentration quantifiable with acceptable accuracy & precision | S/N typically ≥10 | Defines lower end of calibration; matrix effects often limit LOQ in real food samples |

| Calibration Curve | Relationship between analyte concentration and sensor response | ≥6 levels + blank; logistic fit often used; 75% points within ±20–25% of nominal value | Non-linear response at low/high ranges often requires 4/5-parameter modeling |

| Accuracy | Closeness of measured value to true value | Within ±20% (±25% at LLOQ/ULOQ); evaluated within- and between-runs | Challenging when sensor drift or matrix effects occur; needs robust QC planning |

| Precision | Repeatability of results under same conditions | CV ≤20% (≤25% at LLOQ/ULOQ); across ≥6 runs and 5 QC levels | Signal variability from biorecognition elements (e.g. enzyme-based biosensors) must be managed |

| Total Error | Sum of bias (accuracy) and variability (precision) | Should not exceed 30% (40% at LLOQ/ULOQ) | A helpful global indicator of biosensor method performance |

| Dilution Linearity | Consistency of measurement across diluted samples | Mean ±20% of expected after correction; ≥3 dilutions tested | Needed for samples exceeding range; verifies absence of hook effect |

| Hook Effect | Signal suppression at high analyte concentrations | No signal drop-off in undiluted samples expected above ULOQ | Particularly relevant in immunoassay-based biosensors |

| Carry-over | Residual analyte signal from prior sample influencing subsequent results | Signal in blank after ULOQ standard must be <LLOQ | Typically minimal in biosensors; confirm with blank after high calibrator |

| Stability | Analyte remains unchanged during storage, preparation, and analysis | Mean ±20% at low/high QC; validated over actual storage conditions | Biosensor reagents (e.g. enzymes, aptamers) and analyte stability must both be validated |

| Analyte | Biosensor Type | Matrix | LOD/ LOQ | Key Challenges | Mitigation Strategies | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbendazim | upconversion-MnO2 luminescent resonance energy transfer | food | LOD: 0.05 ng·mL−1 | specificity | aptamer integration and high fluorescence quenching capability of MnO2 nanosheets | [91] |

| cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb) and mercury (Hg) | luciferase-based biosensors | food | LOD:Cd: 0.01 μM Pb: 0.025 nM Hg: 2 nM | decrease of sensitivity | expression of Pb importers or nonspecific modifications | [92] |

| Nitrate | Immobilized Nitrate Reductase | dry-cured ham | - | comparison with HPLC | good agreement with standard HPLC method: R 2 = 0.971 | [93] |

| amnesic shellfish toxins: domoic acid | Aptamer-Based Biosensor | - | LOD: 13.7 nM | specificity | identification and truncation optimization | [94] |

| Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning Toxins | Surface Plasmon Resonance-Based Biosensors | shellfish | - | interferences | comparison of several extraction methods | [95] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).