1. Introduction

Emotion recognition is a fundamental component of affective computing and human-computer interaction, with significant implications across healthcare, education, and consumer technologies [

1,

2]. Traditional methods primarily rely on observable cues such as facial expressions or speech. However, these external indicators can be intentionally controlled or masked, limiting their reliability in representing genuine emotional states [

2,

10]. Physiological signals—such as heart rate, blood volume pulse (BVP), and skin conductance—regulated autonomically, offer a more authentic and less voluntarily modifiable reflection of emotional states, making them ideal for unobtrusive affective computing [

2,

4,

10].

Extensive psychophysiological research has firmly established that emotional states trigger characteristic, transient changes in cardiovascular activity [

4,

5,

22]. Heart rate variability (HRV), defined by fluctuations in intervals between heartbeats, reflects autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity, correlating distinctly with emotional regulation processes [

5,

6,

30]. Additionally, pulse waveform morphology captures vascular tone variations associated directly with emotional arousal [

22]. Notably, these physiological responses are transient, sparsely distributed, and exhibit non-uniform temporal patterns—highlighting a critical gap in current approaches: effective identification and interpretation of emotionally salient temporal segments amidst noisy physiological signals.

Recent advancements in remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) enable unobtrusive, camera-based monitoring of cardiovascular activity, measuring subtle skin color variations induced by cardiac pulse waves [

15,

23,

24]. This technique allows scalable affective computing applications across diverse industrial contexts due to the proliferation of camera-equipped devices (e.g., smartphones, laptops, surveillance systems), significantly broadening the practical utility of emotion recognition technology.

Despite promising potential, recognizing emotions exclusively from unimodal temporal rPPG signals faces significant unresolved challenges. Firstly, emotional physiological responses often manifest briefly and sporadically rather than continuously, complicating effective temporal analysis [

4,

5,

10]. Secondly, rPPG signals inherently suffer from noise and artifacts compared to contact-based methods, impairing robust interpretation of subtle emotional cues [

15,

23,

24]. Thirdly, typical session-level annotations induce a weak-label, Multiple Instance Learning (MIL) scenario [

7], necessitating sophisticated models to pinpoint informative temporal segments accurately. Finally, recognizing valence from physiological signals remains inherently more challenging than arousal, with its subtler and more complex physiological correlates less directly tied to general ANS activation [

4,

22,

39].

Our study explicitly addresses these challenges by proposing a novel deep learning framework designed to fully leverage temporal dynamics within unimodal rPPG signals. By processing signals in short, localized temporal chunks, we effectively isolate and analyze transient physiological responses. We introduce a Multi-scale Temporal Dynamics Encoder (MTDE), physiologically motivated by multi-rate ANS response characteristics [

22,

30], capturing subtle temporal patterns across different timescales. Furthermore, an adaptive sparse attention mechanism leveraging α-Entmax and entropy regularization explicitly identifies and prioritizes temporally sparse emotional segments, emulating selective human attentional processes [

16,

19,

37,

38]. A novel gated temporal pooling mechanism robustly aggregates chunk-level information, effectively filtering noise through joint temporal weighting and feature-level gating [

13,

20,

35].

Critically, we employ a physiologically inspired, three-phase curriculum learning strategy—exploration, discrimination, and exploitation—mirroring human attentional refinement during learning [

6,

20,

38]. This systematic training approach addresses weak-label issues, temporal sparsity, and signal noise incrementally, enabling stable, progressive learning from complex, noisy temporal data.

To robustly evaluate our method, we employ weighted F1 scores, addressing class imbalance more objectively compared to prior work such as Mellouk & Handouzi [

9]. Unlike Mellouk & Handouzi [

9], we explicitly validate performance on entirely unseen test sets, enhancing generalizability and methodological rigor. Our evaluations on the MAHNOB-HCI dataset show promising results: for arousal, achieving an accuracy of 66.0%, an F1 of 0.7429, and weighted F1 of 0.6224; for valence, an accuracy of 62.3%, an F1 of 0.6667, and weighted F1 of 0.6227, underscoring our model's effectiveness despite inherent challenges.

Our contributions explicitly bridge critical research gaps, providing clear advancements:

Focused Temporal Analysis of rPPG: Establishes foundational insights into the capabilities and limitations of using exclusively temporal physiological information, providing a rigorous benchmark.

Multi-scale Temporal Dynamics Encoder (MTDE): Effectively captures physiologically meaningful ANS responses across multiple timescales, addressing complexity in subtle temporal emotional signals.

Adaptive Sparse Attention: Precisely identifies transient, emotionally relevant physiological segments amidst noisy rPPG data, significantly enhancing robustness.

Gated Temporal Pooling: Sophisticatedly aggregates emotional information across temporal chunks, effectively mitigating noise and irrelevant features.

Curriculum Learning Strategy: Systematically addresses learning complexities associated with weak labels, noise, and temporal sparsity, ensuring robust, stable model learning.

2. Related Work

2.1. The Physiological Signals for Emotion Recognition

Physiological signals, particularly cardiovascular activity, offer reliable indicators of emotional states due to their involuntary ANS regulation [

3,

4,

5]. HRV and pulse morphology have emerged as critical temporal features reflecting emotional arousal and valence [

22,

30]. Traditional approaches often extract handcrafted temporal features (e.g., HRV frequency bands, SDNN), with newer methods exploring nonlinear temporal dynamics [

11,

17,

33]. Our MTDE explicitly addresses limitations of these conventional approaches by capturing rich, physiologically motivated temporal patterns through a specialized multi-scale neural architecture.

2.2. Remote PPG Signal Extraction and Denoising

Due to higher susceptibility to artifacts, extracting robust temporal waveforms from rPPG signals remains challenging [

15,

23,

24]. Recent deep learning advancements, such as PhysNet, PhysFormer, PhysMamba, RhythmFormer, significantly improve extraction and noise resilience [

25,

28,

32,

36]. We adopt PhysMamba [

32] for its superior temporal refinement and robustness, explicitly addressing the inherent noise challenges of rPPG signals, crucial for accurate emotion inference.

2.3. Emotion Recognition from rPPG/PPG

Only a few studies focus exclusively on temporal rPPG signals. Mellouk & Handouzi [

9] applied CNN-LSTM models on short temporal segments without specialized sparsity or attention mechanisms. Talala et al. [

34] utilized pulse-derived spectral images, implicitly incorporating spatial-temporal features. Contact-based methods often employ multiple modalities or personalization [

11,

17]. Our model, conversely, specifically targets temporal sparsity and noise, utilizing adaptive sparse attention, gated pooling, and structured curriculum learning, thereby significantly advancing beyond existing models.

2.4. Comparison and Key Differences

Distinct from prior works, our approach uniquely addresses:

Temporal-only Focus: Clarifies inherent temporal limitations and potentials, establishing foundational benchmarks.

Explicit Temporal Dynamics Modeling: Physiologically-grounded multi-scale analysis tailored specifically for temporal emotional signals [

22,

30].

Advanced Temporal Attention: Sparse attention explicitly prioritizes salient temporal segments amidst noise, paralleling biological attention mechanisms [

16,

19,

37,

38].

Robust Aggregation Strategy: Gated pooling methodically filters noise, prioritizing emotionally informative temporal segments.

Generalizable, Rigorous Evaluation: Utilizing weighted F1 metrics and unseen test validation enhances objective performance assessments, overcoming methodological shortcomings of previous studies [

9].

3. Methodology

This section delineates the methodology employed in our study for emotion recognition from remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) signals. We describe the dataset utilized, the preprocessing steps, the overall framework architecture, the detailed components of our model, the physiologically-inspired curriculum learning strategy, the evaluation metrics and comparative baseline, and the experimental setup.

3.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

We employ the publicly available MAHNOB-HCI multimodal emotion dataset [

21], comprising recordings from 27 subjects who viewed 20 emotional film clips and provided self-reported valence and arousal ratings on a 1–9 scale. Following common practice and excluding unusable sessions from 3 subjects, our study utilizes a total of 527 face videos. These videos were downsampled to 30 fps, a rate validated as sufficient for capturing the subtle cardiovascular dynamics essential for emotion recognition [

14] and aligning with the pre-training conditions of the PhysMamba model used as our front-end [

32].

The self-reported valence and arousal ratings were binarized into "low" (ratings 1–4) and "high" (ratings 5–9) classes by thresholding at the midpoint (4.5), resulting in minor class imbalances across the full dataset (Arousal: 270 low vs. 257 high, Valence: 251 low vs. 276 high). To ensure rigorous testing of the model's generalization capability and prevent data leakage, a strict subject-independent split was adopted. The 527 sessions were partitioned into 421 sessions (80%) for training, 53 sessions (10%) for validation, and 53 sessions (10%) for testing. While the limited dataset size necessitates relatively small validation and test sets, this rigorous partitioning ensures evaluation solely on entirely unseen subjects, providing a more realistic assessment of applicability compared to splits permitting subject overlap. The dataset is publicly available under a CC-BY-NC-SA license, and our study complies with GDPR by utilizing anonymized data, thus not requiring further ethical approval.

The MAHNOB-HCI dataset is publicly available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC-BY-NC-SA) license. Our study complies with this license and GDPR regulations, as only de-identified, pre-recorded data were used and no personally identifiable information was processed.

3.2. Overall Framework

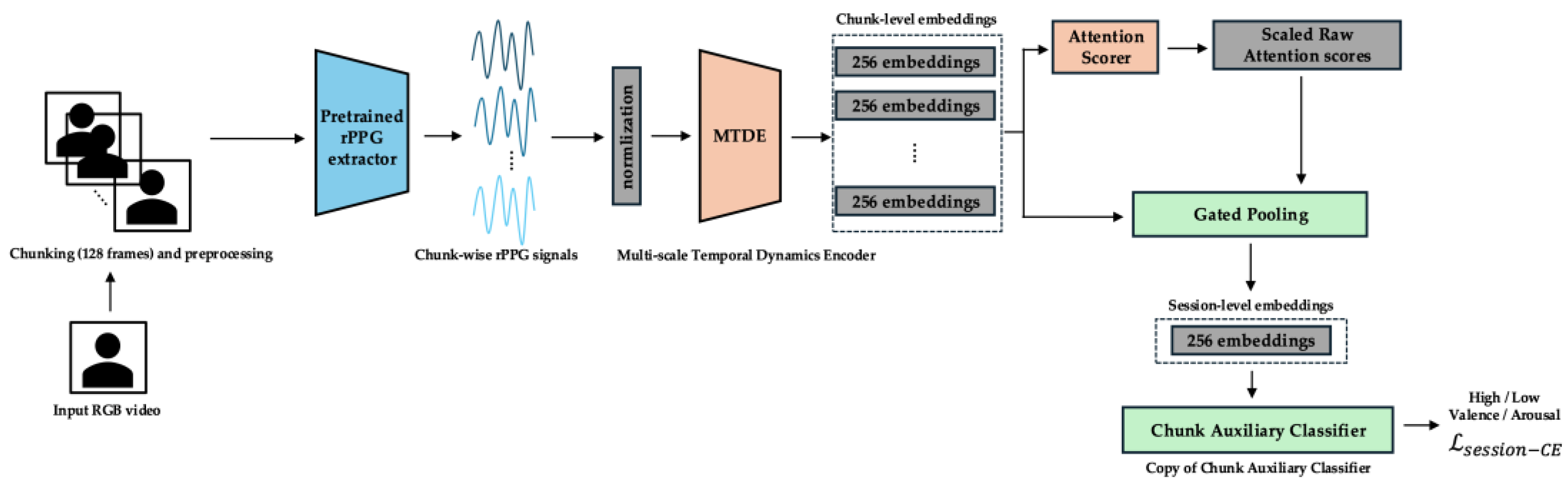

The overall architecture of our proposed end-to-end framework is illustrated in

Figure 1. This figure depicts the core model structure as it operates during Phase 2 of training (session-level exploitation and inference), representing the complete pipeline from the raw video input (via the rPPG extractor) to the final emotion prediction. The pipeline fundamentally consists of a pre-trained rPPG extraction front-end, followed by our emotion recognition model.

Our emotion recognition model processes the 1D temporal rPPG signal, derived from the video, in fixed-length, non-overlapping temporal chunks of 128 frames (approximately 4 seconds at 30 fps). This specific chunk size was strategically chosen for multiple reasons. Firstly, it aligns with the temporal window used by the robust PhysMamba rPPG extractor [

32] and common processing units in the rPPG-Toolbox framework [

14]. Secondly, and crucially, prior work [

9] has demonstrated that a 4-second segmentation size yields optimal performance for emotion classification from contactless PPG signals, reinforcing its appropriateness for capturing pertinent physiological dynamics within the temporal domain. Physiologically, a

4-second window is well-suited as it typically encompasses several cardiac cycles (e.g., approximately 4–7 heartbeats at a resting heart rate of 60-100 bpm). Analyzing physiological patterns such as heart rate variability (HRV) or subtle pulse waveform changes over this duration allows for the capture of meaningful short-term autonomic nervous system (ANS) modulations [30, 22], which are widely recognized as crucial indicators of emotional states.

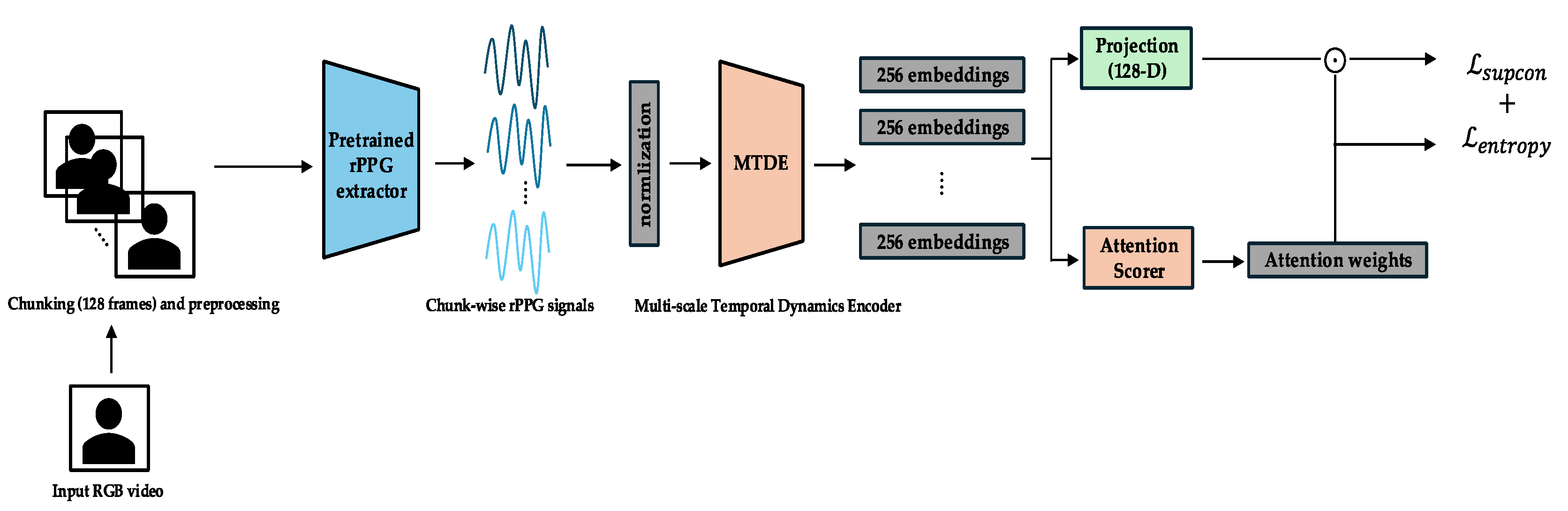

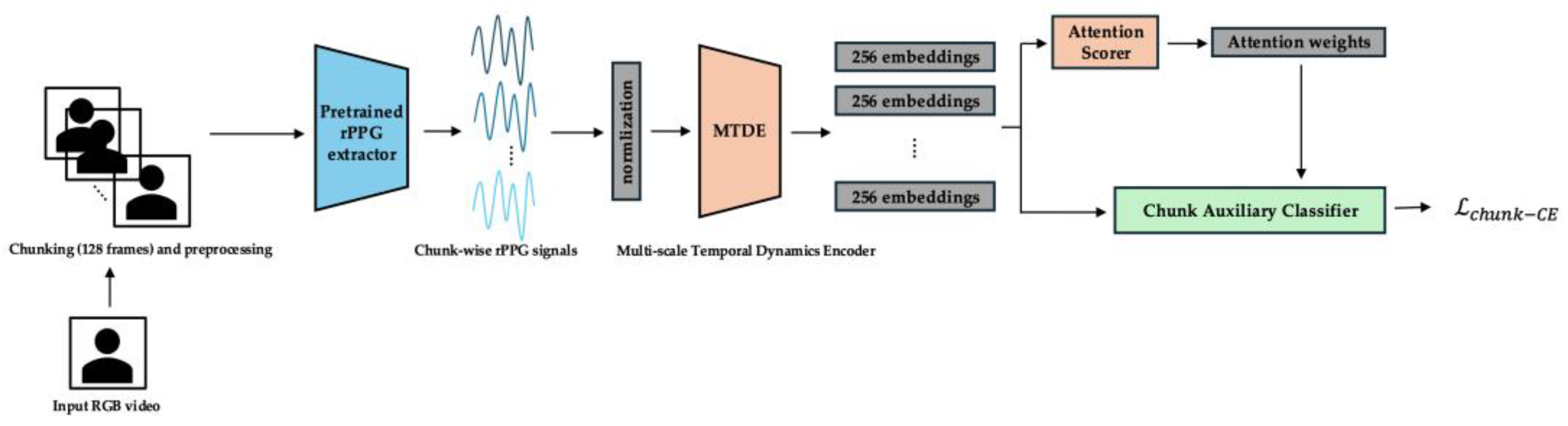

Each temporal chunk is subsequently processed by the Multi-scale Temporal Dynamics Encoder (MTDE) to extract rich temporal feature embeddings. These chunk embeddings are then fed to the AttnScorer to derive a scalar attention score indicating their potential emotional relevance, and also passed to the GatedPooling module. The GatedPooling module integrates these attended and gated chunk features into a single session-level representation. Finally, a Main Classifier predicts the session-level emotion labels (Valence/Arousal) from this pooled representation, based exclusively on the aggregated temporal information. Specific details and components active during the earlier Phase 0 and Phase 1 training, which build upon or extend this core architecture, are illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, respectively, and are described in detail in the subsequent section on the curriculum learning strategy.

3.3. Training Modules

This section provides a detailed description of the core modules constituting our emotion recognition framework.

3.3.1. rPPG Extraction Front-end (PhysMamba)

The PhysMamba [

32] model serves as the initial step to extract a refined, denoised 1D temporal rPPG (Blood Volume Pulse, BVP) signal from raw facial video frames. We utilize the pre-trained PhysMamba, a robust deep learning model demonstrating state-of-the-art performance in recovering accurate BVP signals even under challenging real-world conditions [

32]. PhysMamba is applied to each video by first dividing it into non-overlapping 128-frame (

4 s) chunks, processing each chunk independently. Input frames to PhysMamba are preprocessed using the DiffNormalized scheme [

32], which computes frame-wise ratio differences normalized by the standard deviation, enhancing the detection of subtle blood flow changes. The output of PhysMamba is a refined 1D temporal BVP signal representation for each chunk, serving as the exclusive input to our subsequent emotion recognition model without further per-session normalization or bandpass filtering.

3.3.2. Multi-scale Temporal Dynamics Encoder (MTDE)

The MTDE's purpose is to effectively capture physiological dynamics across various temporal scales present within each 128-frame BVP chunk, designed with a biologically inspired [

22,

30] multi-scale architecture. As detailed in

Appendix A, the MTDE comprises two main stages: a SlimStem and a MultiScaleTemporalBlock (MSTB). The SlimStem consists of two sequential 1D convolutional layers for initial noise reduction and low-level feature extraction, reducing input length by half, conceptually akin to early sensory filtering. The MSTB features a three-branch architecture using dilated convolutions to achieve different effective receptive field (RF) sizes on the original chunk input. The approximate effective RFs for each branch (Short:

6 frames,

0.2 s; Medium:

66 frames,

2.2 s; Long:

129 frames,

4.3 s) are calculated based on layer parameters (

Appendix A) and linked to distinct physiological phenomena. The Short scale is sensitive to rapid physiological changes like pulse upslope and beat onset, often linked to sympathetic activation [

22]. The Medium scale captures patterns related to short-term HRV, primarily associated with parasympathetic regulation [

30]. The Long scale integrates slower fluctuations across the chunk, reflecting ANS interplay [

22]. Outputs from the three MSTB branches are concatenated, normalized, and passed through a Softmax-based temporal attention pooling layer (SoftmaxPool) applied across the temporal dimension. This layer learns to weigh the importance of different temporal steps within the chunk, producing a single, fixed-size chunk embedding (

, where

=256).

3.3.3. AttnScorer

The AttnScorer's purpose is to generate a scalar attention score for each chunk embedding (

), indicating its potential emotional relevance. It consists of a 2-layer MLP with GELU activation (

Appendix B). Raw attention scores are normalized using

scaling, an adaptive mechanism based on the running standard deviation, analogous to biological sensory normalization [

37]. Scores are then transformed using α-Entmax [

16] attention with adaptive α annealing (

Appendix B) to encourage sparse, differentiable selection of salient chunks, mirroring biological selective attention [19, 37, 38]. Entropy regularization further ensures attention sparsity and efficient neural encoding.

3.3.4. Auxiliary Components

These modules are active only during specific curriculum phases (

Figure 2,

Figure 3) to support learning objectives. The ChunkProjection (Phase 0) is an MLP head for normalized embeddings used by the Supervised Contrastive Loss [

12]. The ChunkAuxClassifier (Phase 1) is a classifier attached before GatedPooling, predicting session labels from individual chunks to pretrain the MTDE for local discrimination. It is used to initialize the Main Classifier in Phase 2.

3.3.5. GatedPooling

GatedPooling aggregates the sequence of chunk embeddings (

) into a single session-level representation (

). Unlike standard pooling [

23], it implements a learned, content-aware aggregation [20, 13] via temporal attention and feature-level gating. Using AttnScorer scores (via α-Entmax) for temporal weights (

) and a learned gate vector (

) per chunk (MLP + Sigmoid), it computes:

The feature-level gating () is pivotal; it modulates contribution of each feature dimension within a chunk, mimicking biological neural gating/inhibition [19, 37, 38] to selectively amplify relevant signals and suppress noise/irrelevant features within temporally attended segments, critical for robust rPPG analysis.

3.3.6. Main Classifier

The Main Classifier receives the vector and predicts final emotion labels (Low/High Valence/Arousal) via FC layers, based solely on aggregated temporal rPPG information.

3.4. Training Curriculum

Our training employs a three-phase curriculum learning strategy [6, 38], conceptually

inspired by how biological systems, including humans, refine their learning and attentional focus [

20]. This structured approach guides the model through progressively more complex learning objectives, addressing the inherent challenges of noisy, temporally sparse, and weakly-labeled time-series data to achieve stable and effective learning. The entire training process runs for a total of 50 epochs. The specific pipeline configuration and module activations during each phase are illustrated in

Figure 1,

Figure 2, and

Figure 3. Detailed hyperparameters for each phase are provided in

Appendix C.

3.4.1. Phase 0 (Epochs 0–14): Exploration and Representation Learning.

Physiological/Cognitive Link: This initial phase serves as an analogy to broad, unguided sensory exploration in biological systems. Before specific pattern recognition, a system first captures a wide array of sensory inputs to build a general understanding of the feature space. Similarly, the model focuses on encoding diverse physiological patterns within the rPPG signal across different time scales, irrespective of the final emotional labels, aiming to structure the embedding space based on inherent data characteristics and label proximity.

Objective: The primary objective is to train the MTDE and related components (AttnScorer, ChunkProjection) to produce robust and diverse embedding representations for individual temporal chunks. During this phase, the GatedPooling module and the Main Classifier are not used for the primary loss computation.

Primary Losses: The total loss in Phase 0 is a combination of the Supervised Contrastive Loss and an Entropy Regularization Loss. The Supervised Contrastive Loss (

) [

12] is applied to the normalized embeddings from the ChunkProjection. This loss encourages embeddings from chunks originating from the same session (sharing the same label) to be closer in the representation space, while pushing embeddings from different sessions apart. This helps structure the embedding space according to emotional labels and promotes representation diversity.

Here,

is the set of anchor indices in the batch,

is the set of all indices in the batch except

,

is the set of indices of positive samples (same label) as

,

represents the normalized embedding vectors, and

is the temperature parameter.

The Entropy Regularization Loss (

) is applied to the AttnScorer's internal Softmax attention output. With a weight

(detailed in

Appendix C), this loss encourages the initial attention distribution to be more uniform across chunks, promoting broader exploration of temporal features by the MTDE. The temperature parameter τ for

is adaptively scheduled (

Appendix C) based on the complexity of learned attention distributions, facilitating effective contrastive learning alongside exploration. The overall loss for this phase is

.

3.4.2. Phase 1 (Epochs 15–29): Chunk-level Discrimination and Attentional Refinement.

Physiological/Cognitive Link: This phase simulates the development of selective attention and fine discrimination. After initial broad exploration, a biological system learns to differentiate between stimuli and focus processing on the most relevant or challenging aspects. In this phase, the model refines its ability to discriminate between emotional classes specifically at the chunk level, learning to focus its attention on the temporal segments that are most informative or difficult to classify amidst noise.

Objective: To significantly enhance the discriminative capacity of the individual chunk embeddings and to refine the AttnScorer's ability to identify emotionally salient temporal segments. During this phase, the ChunkProjection module and its loss are frozen. The MTDE, AttnScorer, and ChunkAuxClassifier are actively trained. The GatedPooling module's parameters also begin training from epoch 25, preparing for the final session-level task.

Primary Losses: The total loss in Phase 1 combines a Chunk-level Cross-Entropy Loss with a gradually introduced Session-level Cross-Entropy Loss. The Chunk-level Cross-Entropy Loss (

) is applied using the ChunkAuxClassifier. To effectively handle potential class imbalance present at the chunk level and to focus learning on challenging examples, we employ Focal Loss [

41] with

(

Appendix C):

Here,

is the model's estimated probability for the target class,

is a class-balancing weight, and

is the focusing parameter. This loss is critically calculated

only for the Top-K chunks selected based on the AttnScorer's α-Entmax output. The Top-K ratio

is strategically annealed downwards over this phase (schedule in

Appendix C) to progressively focus discriminative learning on the most salient segments,

mimicking how attention narrows onto key details [8, 20] within a stimulus. The Session-level Cross-Entropy Loss (

)

is scheduled to be introduced from epoch 25, with its weight gradually ramping up from 0 to 0.5 (see schedule in

Appendix C). While the

parameters of the GatedPooling module and the session-level classifier are unfrozen starting at this point, allowing gradient flow and preparatory fine-tuning,

L_session-CE itself is not yet included in the total loss calculation until Phase 2. This staged activation strategy enables the model to begin adapting the session-level representation and pooling dynamics without prematurely influencing the optimization objective, thus facilitating a smoother transition to Phase 2 training. The overall loss for this phase is

3.4.3. Phase 2 (Epochs ≥ 30): Session-level Exploitation and Fine-tuning.

The Physiological/Cognitive Link: This final phase is analogous to integrating filtered and relevant information to make a final decision or judgment. The system leverages its refined chunk representations and attentional mechanisms to consolidate evidence from the most salient and informative features identified across time, leading to the final emotional inference.

Objective: To optimize the entire end-to-end pipeline for the final session-level emotion recognition task. In this phase, the ChunkAuxClassifier and its associated loss are removed. The Main Classifier is initialized using the trained weights from the ChunkAuxClassifier at the start of epoch 30. The MTDE, AttnScorer, GatedPooling, and the Main Classifier are all actively trained. The full pipeline shown in

Figure 1 is operational.

Primary Loss Function: The sole objective function in Phase 2 is the Session-level Cross-Entropy Loss (

) applied to the output of the Main Classifier based on the GatedPooling session embedding. Its weight ramps up from 0.5 (at epoch 30) towards 1.0 (schedule in

Appendix C) to become the primary focus.

Here,

is the one-hot encoded ground truth label for the session,

is the predicted probability distribution over classes from the Main Classifier, and

is the number of classes. During this phase, the AttnScorer is fine-tuned at a reduced learning rate (scaling factor in

Appendix C). Additionally, the

value for the α-Entmax transformation within the GatedPooling module is annealed from 1.5 (at epoch 30) to 1.8 (at epoch 50) (schedule in

Appendix C). This increases the sparsity of the temporal attention applied during aggregation, further refining the focus on the most crucial temporal segments and their gated features for the final prediction.

3.5 Evaluation Metrics

Model performance was quantitatively evaluated using standard metrics on the independent test set. These metrics were chosen to provide a comprehensive and robust assessment, particularly considering potential class imbalances. Performance was measured using Accuracy and Weighted F1-score. The Weighted F1-score is particularly valuable in the presence of class imbalances, as it accounts for performance on all classes weighted by their frequency, providing a more objective measure than simple accuracy or macro-averaged metrics in such scenarios.

Accuracy: Defined as the proportion of correctly classified sessions out of the total number of sessions in the test set:

Weighted F1-score: This metric is calculated based on the Precision (

), Recall (

), and F1-score (

) for each individual class

. The formulas for these class-specific metrics are:

The overall Weighted F1-score is then computed as the average of the class F1-scores, weighted by the number of samples in each class (

):

Here, is the total number of samples in the test set, and is the number of classes. In addition to these primary metrics, we also analyze the confusion matrix to gain insights into the model's performance across different classes and the types of errors made.

3.6. Baseline

We provide a comparative evaluation against Mellouk & Handouzi [

9], a relevant prior deep learning work on contactless PPG emotion recognition using CNN-LSTM on

4s segments but lacking explicit sparsity/attention. We utilize their reported results. However, achieving an ideal comparison on our exact subject-independent split is limited by their source code unavailability and unspecified test partition. Our study mitigates this by detailing our split and using Weighted F1 for robust comparison despite potential test set distribution differences, establishing a clearer benchmark.

3.7. Experimental Setup

Training was performed using the AdamW optimizer. We employed a CosineAnnealingLR schedule, with for Phases 0 and 1, and for Phase 2. The initial learning rates were set to , , and for Phases 0, 1, and 2, respectively. Weight decay was in Phase 0 and in Phases 1 and 2. All experiments were run on a system with Ubuntu 20.04, Python 3.8, PyTorch 2.1.2 (+ CUDA 12.1) and an NVIDIA RTX 4080 GPU with a batch size of 8.

4. Results

4.1. Main Results

As summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2, the proposed end-to-end framework demonstrates competitive performance in arousal classification using only the temporal rPPG signal from the MAHNOB-HCI dataset under a subject-independent evaluation protocol. Specifically, the model achieves an accuracy of 64.04% and a weighted F1-score of 61.97%, which are on par with those reported by other unimodal physiological approaches such as HRV-based methods [

40]. These results highlight the expressive power of temporal rPPG signals when effectively modeled using our dedicated temporal representation learning architecture.

When compared against a conventional CNN-LSTM baseline [

9]—evaluated using their reported confusion matrix—our model yields consistent improvements across all relevant metrics:

Accuracy: 64.04% vs. 61.31%

Positive-class F1-score: 74.29% vs. 50.96%

Weighted F1-score: 61.97% vs. 59.46%

These improvements validate the effectiveness of our architectural choices, including multi-scale temporal encoding, sparse attentional chunk selection, and feature-level gated pooling, in capturing discriminative temporal dynamics from the rPPG signal. Notably, these gains are achieved under a rigorous subject-independent setting, underscoring the model’s generalizability and robustness. The performance margin over the prior deep learning baseline affirms the merit of our tailored design for temporal-only physiological modeling.

In contrast, valence classification remains a more complex and challenging task. Our model achieves 62.26% accuracy and 62.26% weighted F1-score, which are both substantially lower than those reported by the CNN-LSTM baseline (73.50% accuracy and 73.14% weighted F1). The corresponding confusion matrix is provided in

Appendix D (Table D.2).

This performance gap can be attributed to several fundamental factors:

Physiological limitations: Arousal is closely associated with

autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity—particularly sympathetic arousal—which is effectively captured through heart rate and HRV patterns inherent in rPPG signals [3, 22, 30, 39]. In contrast, valence is more intricately tied to

subtle physiological cues, such as facial muscle activity (e.g., EMG) or cortical patterns, which are not sufficiently reflected in peripheral cardiovascular dynamics [

39].

Modality constraints: The use of spatially averaged 1D temporal rPPG precludes access to fine-grained spatial information, such as facial blood flow asymmetries, which have been shown to correlate with valence [34, 27].

Data imbalance: A notable class imbalance in valence labels, both in the overall dataset and particularly within the test set, may contribute to biased predictions and hinder generalization performance.

Collectively, these findings suggest that while temporal rPPG is a potent modality for arousal recognition, effective valence modeling may necessitate either multimodal fusion or spatially-aware approaches to capture its more nuanced correlates.

4.2. Ablation Studies

To quantitatively assess the contributions of individual components in our model architecture and training pipeline, we conducted ablation experiments centered on the arousal classification task. These experiments isolate the effect of each module when relying solely on temporal rPPG inputs, and the results are reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

4.2.1. Ablation Study on Pooling and Attention Mechanisms (Arousal)

We first examined the effect of various temporal aggregation strategies applied to chunk-level embeddings extracted via the Multi-Temporal Dynamics Encoder (MTDE). As shown in

Table 3, our proposed

Gated Pooling mechanism delivers superior performance compared to simpler alternatives.

These results reveal that naïve temporal averaging or soft attention pooling fails to effectively aggregate salient information in the rPPG signal. In contrast, the combination of learned chunk-wise attention scoring (AttnScorer) and feature-level modulation (Gated Pooling) provides a more precise and robust representation of emotionally relevant temporal patterns, resulting in improved classification performance.

4.2.2. Ablation Study on Pooling and Attention Mechanisms (Arousal)

We further evaluated the impact of our

three-phase curriculum learning strategy, which progressively transitions from exploratory representation learning to discriminative and exploitative stages.

Table 4 presents the classification results under different curriculum variants.

The results demonstrate that:

Phase 0 (Contrastive learning) significantly enhances the diversity and expressiveness of learned representations.

Phase 1 (Chunk-level weak supervision) improves the model’s ability to localize and distinguish emotionally salient segments.

Phase 2 (Session-level classification) yields optimal results only when preceded by these preparatory stages.

This progressive strategy mirrors human-like attentional learning, facilitating stable and effective optimization on weakly labeled and noisy temporal signals. The marked performance gain from the full curriculum attests to the importance of structured, phase-aware training for robust rPPG-based affect recognition.

4.3. Computational Efficiency

Average inference time for an 2-minute session is approximately 0.66 seconds on NVIDIA RTX 4080 GPU, faster than real-time, enabling practical deployment using this temporal-only approach. Trainable parameters: 197,892 total; 164,996 for inference (Inference uses fewer parameters as the Chunk-Projection module, only needed for Phase 0 training, is removed).

5. Discussion

Our proposed framework demonstrates promising capabilities in recognizing emotions exclusively from temporal remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) signals, achieving competitive arousal classification performance under rigorous subject-independent evaluation. Specifically, our model attains

a 66.04% accuracy and a

weighted F1-score of 61.97% for arousal, outperforming the CNN-LSTM baseline by Mellouk & Handouzi [

9] (Accuracy: 61.31%, Weighted F1: 59.46%). This improved performance for arousal underscores the efficacy of our specialized temporal processing techniques—including the Multi-scale Temporal Dynamics Encoder (MTDE), adaptive sparse attention via α-Entmax, and the feature-level GatedPooling mechanism—in effectively extracting, filtering, and leveraging the discriminative temporal dynamics inherent in rPPG signals, which are strongly tied to autonomic nervous system (ANS) arousal responses.

A critical factor contributing to this performance enhancement is our physiologically-inspired MTDE. By employing parallel convolutional branches with distinct receptive fields, the MTDE explicitly captures emotional cues manifesting at multiple temporal scales, reflecting diverse ANS modulations. These captured dynamics include rapid pulse morphology changes (indicating sympathetic activation), beat-to-beat interval variations (reflecting parasympathetic activity), and slower trends integrating broader sympathetic-parasympathetic interplay [

22,

30].

Capturing these multi-rate temporal signatures is particularly vital for arousal recognition, as ANS activation patterns tied to arousal frequently involve changes in both the speed (heart rate) and the variability/shape of the pulse wave over short time periods. Furthermore, our adaptive sparse attention mechanism refines the temporal analysis by selectively emphasizing emotionally salient segments amidst inherently noisy physiological data. This process, closely mimicking human selective attention [

18,

37,

38], is crucial for robust detection from rPPG, where emotional cues are often transient and sparsely distributed in the temporal stream, easily masked by noise. Moreover, our novel GatedPooling mechanism effectively mitigates the impact of noise and irrelevant features by integrating learned feature-level gating. This allows the model to not only weight the importance of

temporal segments but also to amplify or suppress specific feature dimensions

within those segments, providing a refined representation crucial for handling the noisy nature of remote physiological signals.

Beyond these architectural innovations, our staged curriculum learning strategy was vital for achieving optimal performance. By progressively transitioning the learning objectives—from broad, exploratory representation learning in Phase 0 (analogous to initial sensory intake), through chunk-level discriminative refinement focusing on salient cues in Phase 1 (simulating selective attention and discrimination), to final session-level exploitation and fine-tuning in Phase 2 (akin to decision-making based on integrated information) [

6,

20,

38]—the curriculum effectively addresses the inherent challenges posed by noisy, temporally sparse, and weakly-labeled time series data. This structured learning process guides the model towards learning robust features and reliable attentional mechanisms before attempting the complex session-level prediction, resulting in more stable and effective learning outcomes compared to end-to-end training without such guidance. Indeed, our ablation studies (detailed in

Section 4.2) further validate the necessity of each component (MTDE, Sparse Attention, GatedPooling) within our architecture and underscore the critical role of the staged curriculum learning strategy in enabling the observed performance gains.

Conversely, the valence recognition task remains significantly challenging when relying exclusively on temporal rPPG signals. Our model achieved 62.26% accuracy and a weighted F1-score of 62.26% for valence, which was lower than the performance reported by Mellouk & Handouzi’s baseline [

9] (Accuracy: 73.50%, Weighted F1: 73.14%). This discrepancy highlights fundamental physiological limitations and inherent methodological constraints in valence detection using only

temporal, spatially averaged rPPG data. Physiologically, valence correlates with more nuanced patterns such as subtle facial muscle activity and specific cortical region activations [

39], which are not directly captured by changes in the average blood pulse wave over time. Furthermore, subtle

spatial variations in facial blood flow, which may hold valence-related information [

29,

34], are inherently lost when the rPPG signal is derived as a single temporal waveform averaged over a facial region. These findings strongly reinforce that while temporal rPPG signals robustly reflect general ANS activation tied closely to arousal, recognizing more nuanced affective dimensions like valence likely requires either multimodal integration (e.g., with facial expressions) or advanced spatial-temporal rPPG analysis that preserves regional blood flow patterns.

Regarding practical applicability, the computational efficiency of our approach is notable. Achieving an inference speed of approximately 0.66 seconds for a two-minute video segment on an NVIDIA RTX 4080 GPU, our model operates faster than real-time. Furthermore, its compact size (164,996 parameters at inference) facilitates deployment in resource-constrained scenarios (e.g., mobile devices, edge computing), significantly enhancing the viability of our temporal-only rPPG approach for unobtrusive affective computing in real-world applications where dedicated sensors or multiple modalities may not be feasible. This demonstrates the potential of specialized temporal models even within the limitations of the unimodal signal.

5.1. Limitations

Despite demonstrating advancements in temporal rPPG-based emotion recognition, our study presents several limitations that inform future research directions. Firstly, our evaluation is confined to the MAHNOB-HCI dataset. Although widely recognized, its limited scale (527 sessions) and potential lack of diversity across varied populations and emotional elicitation methods may constrain the generalizability of our findings. Secondly, the deliberate restriction to temporal-only rPPG, while defining the specific scope of our investigation, inherently excludes potentially valuable spatial information from rPPG itself or complementary affective cues from other modalities. As evidenced by the lower performance in valence recognition, this limitation underscores the inherent constraints of relying solely on a spatially averaged temporal pulse signal for nuanced affective dimensions.

5.2. Future work

Addressing the identified limitations suggests several clear avenues for future research to build upon the temporal processing foundations established by this study. Validating our proposed framework on larger and more diverse datasets (e.g., DEAP, WESAD) is crucial to assess its generalization and robustness across varied contexts and populations. Exploring more granular emotion classification (e.g., predicting continuous valence/arousal or discrete emotions) and investigating personalization strategies (e.g., few-shot subject calibration or transfer learning) could significantly enhance practical applicability and performance. Importantly, to improve the recognition of nuanced affective dimensions like valence, future work should explore the integration of spatial-temporal rPPG analyses that preserve regional blood flow patterns, or multimodal fusion with complementary affective cues such as facial expressions or audio signals. Evaluating our model on alternative emotional elicitation methods, such as the large-scale VR-based dataset by Marín Morales et al. [

31], would further strengthen validation and assess domain generalization. Finally, while our attention mechanism targets sparsity, deeper analyses could yield critical insights into

which specific physiological dynamics and temporal patterns are most indicative of different emotional states, potentially informing more interpretable models.

Collectively, our results establish foundational benchmarks and methodological insights for future advancements in unimodal physiological emotion recognition, clearly defining both the capabilities and inherent limitations of relying solely on temporal-only rPPG signals. The comprehensive physiological and cognitive grounding of our approach, combined with rigorous evaluation protocols, ensures robust, interpretable, and applicable outcomes, advancing the state-of-the-art in this challenging area of affective computing research.

6. Conclusions

We introduced a physiologically-inspired deep learning framework for recognizing emotional states exclusively from temporal remote photoplethysmography (rPPG). Our approach systematically addresses critical limitations—temporal sparsity, signal noise, and weak labeling—through the Multi-scale Temporal Dynamics Encoder (MTDE), adaptive sparse attention, Gated Temporal Pooling, and a structured three-phase curriculum learning strategy. Empirical evaluation confirmed competitive performance in arousal classification (66.04% accuracy, 61.97% weighted F1), surpassing previous deep learning baselines. Conversely, lower performance in valence classification (62.26% accuracy) reveals fundamental physiological constraints in using solely temporal cardiovascular signals, clearly demarcating the capability boundaries of unimodal rPPG signals.

These results establish robust methodological benchmarks and highlight promising directions for future exploration: incorporating spatially-resolved rPPG analysis or multimodal integration could significantly enhance nuanced emotional inference. This study provides critical foundational insights and clear guidelines to advance affective computing towards more accurate, reliable, and interpretable physiological emotion recognition.

Code Availability

Our code and trained models are available at

https://github.com/LeeChangmin0310/ReMOTION-Temporal. The repository includes the training scripts, inference demo, and the raw split lists used for reproducibility. Experimental environment details are also provided in the repository's README, consistent with the setup described in

Section 3.7.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. H.L. and M.W.; methodology, C.L.; software, C.L.; validation, C.L. and H.L.; formal analysis, C.L.; investigation, C.L.; resources, M.W.; data curation, C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.; writing—review and editing, H.L. and M.W.; visualization, C.L.; supervision, M.W.; project administration, M.W.; funding acquisition, M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by an Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute(ETRI) grant funded by the Korean government [25ZB1100, Core Technology Research for Self-Improving Integrated Artificial Intelligence System] and the Technology Innovation Program (or Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program-Knowledge service industrial technology development) (20023561, Development of learncation service for active senior life planning and selfdevelopment support) funded by the Ministry of Trade Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea)

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The study uses the publicly released MAHNOB-HCI dataset, which contains de-identified recordings collected under the authors’ original institutional approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Emotion Contents Technology Research Center members for their feedback on experimental design.

Conflicts of Interest

none

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Acc |

Accuracy |

| ANS |

Autonomic Nervous System |

| AttnScorer |

Attention Scorer |

| BVP |

Blood Volume Pulse |

| CE |

Confusion Matrix |

| CM |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| EDA |

Electrodermal Activity |

| HRV |

Heart Rate Variability |

| MIL |

Multiple Instance Learning |

| MTDE |

Multi-scale Temporal Dynamics Encoder |

| rPPG |

remote Photoplethysmography |

| WF1 |

Weighted F1-score |

Appendix A. Architecture Details of MTDE

A.1. Architecture Overview

The MTDE encodes each 128-frame (4 s) rPPG chunk into a 256-dimensional embedding through two stages:

SlimStem: Two Conv1D layers (kernel=5, then 3 with stride=2) for initial noise reduction and temporal downsampling (T=128 → 64).

MultiScaleTemporalBlock (MSTB): Three parallel branches with different kernel sizes and dilations to model short-, mid-, and long-range temporal dynamics.

A.2. Physiological Rationale & Receptive Fields

Table A1.

Table of MSTB’s parameters per branch.

Table A1.

Table of MSTB’s parameters per branch.

| Branch |

Kernel |

Dilation |

Effective RF |

Approx. Duration |

Physiological Role |

| Short |

3 |

3 |

6 |

∼0.2 s |

Pulse upslope, sympathetic ramp |

| Medium |

5 |

8 |

66 |

∼2.2 s |

High-frequency HRV |

| Long |

3 |

32 |

129 |

∼4.3 s |

Multi-cycle ANS modulation |

Here, Receptive Field can be calculated by

A.3. Pooling Layer: SoftmaxPool

Softmax over time across temporal steps:

This results in a single (B, D) embedding per chunk. No gating is applied in this layer.

Appendix B. Attention Modules: AttnScorer and GatedPooling

B.1. AttnScorer: Phase-aware Attention Scoring

B.1.1. Architecture

o 2-layer MLP: Linear(D, D/2) → GELU → Linear(D/2, 1)

o Zero-mean score normalization:

scaling with EMA-based adjustment:

o Raw score scaling:

B.1.2. Phase-dependent Attention Mechanism

Table 1.

Table of Attention Type per phase.

Table 1.

Table of Attention Type per phase.

| Phase |

Epoch Range |

Attention Type |

Notes |

| 0 |

0–14 |

Softmax (with temperature ) |

Encourages diversity |

| 1 |

15–29 |

-Entmax (adaptive ) |

Sharp, sparse, differentiable Top-K |

| 2 |

≥30 |

Raw scores only |

Passed to GatedPooling |

B.1.3. Entmax Scheduling during Phase 1.

B.2. GatedPooling: Sparse Temporal Aggregation

Receives chunk embeddings

and raw attention scores. In Phase 2, the attention scores are transformed using

-Entmax to produce temporal weights:

The session-level pooled embedding is computed as:

Where

denotes element-wise multiplication

is scheduled during Phase 2 as:

This dual mechanism (Temporal weight Feature gate) reflects neural inhibition, enabling selective suppression of irrelevant dimensions even within sailent chunks.

Appendix C. Phase-wise Training Schedule

Table 1.

Epoch-based Curriculum Strategy.

Table 1.

Epoch-based Curriculum Strategy.

| Phase |

Epochs |

Objective |

Active Modules |

| 0 |

0–14 |

Embedding diversity (SupCon) |

MTDE, AttnScorer, ChunkProjection |

| 1 |

15–29 |

Chunk-level discrimination |

+ ChunkAuxClassifier, GatedPooling✓ (E≥25) |

| 2 |

30–49 |

Session-level classification |

GatedPooling, Classifier |

Table 2.

Hyperparameter Scheduling.

Table 2.

Hyperparameter Scheduling.

| Epoch |

Top-K Ratio |

SupCon

|

CE

|

|

(Temp)

|

(AttnScorer)

|

(Gated)

|

| 0 |

0.0 |

1.00 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

1.2 |

— |

— |

| 14 |

0.0 |

0.44 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.7 |

— |

— |

| 15 |

0.6 |

0.0 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

— |

| 25 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

1.7 |

start = 1.7 |

| 30 |

— |

0.0 |

0.7 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

raw only |

1.7 → 2.0 |

| 50 |

— |

0.0 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

raw only |

2.0 |

Appendix D. Contusion Matrices

This appendix provides the confusion matrices for Arousal and Valence classification results from the final proposed model evaluated on the MAHNOB-HCI test set.

Table D1.

Confusion Matrix – Arousal Classification (Final Model).

Table D1.

Confusion Matrix – Arousal Classification (Final Model).

| |

Predicted Low |

Predicted High |

| Actual Low |

9 |

18 |

| Actual High |

0 |

26 |

Accuracy: 64.04%

Weighted F1-score: 61.97%

The model shows strong sensitivity to high arousal states (recall: 100%), with most misclassifications occurring in the low-arousal category.

Table D2.

Confusion Matrix – Valence Classification (Final Model).

Table D2.

Confusion Matrix – Valence Classification (Final Model).

| |

Predicted Low |

Predicted High |

| Actual Low |

13 |

10 |

| Actual High |

10 |

20 |

Accuracy: 62.26%

Weighted F1-score: 62.26%

The model demonstrates relatively balanced performance but reveals confusion between low and high valence categories, indicating the nuanced nature of valence detection from unimodal temporal signals.

References

- Author 1, Calvo, R. A.; D'Mello, S. Affective computing and education: Learning about feelings. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2010, 1, 161–164. [CrossRef]

- Picard, R.W. Affective Computing; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreibig, S.D. Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion: A review. Biol. Psychol. 2010, 84, 394–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Gardner, W.L.; Berntson, G.G. The affect system has parallel and integrative processing components: Form follows function. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 839–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada, F.; Russell, J.A. The affective core of emotion. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 807–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elman, J.L. Learning and development in neural networks: The importance of starting small. Cognition 1993, 48, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietterich, T.G.; Lathrop, R.H.; Lozano-Pérez, T. Solving the multiple instance problem with axis-parallel rectangles. Artif. Intell. 1997, 89, 31–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itti, L.; Koch, C.; Niebur, E. A model of saliency-based visual attention for rapid scene analysis. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1998, 20, 1254–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellouk, W.; Handouzi, W. Deep Learning-Based Emotion Recognition Using Contactless PPG Signals. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauss, I.B.; Robinson, M.D. Measures of emotion: A review. Cogn. Emot. 2009, 23, 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanberg, J. Emotion recognition from physiological signals. Master's Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, P.; Teterwak, P.; Wang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Anand, A.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y. Supervised contrastive learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Virtual Conference, 6-12 December 2020; Volume 33, pp. 1602–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X. Gated convolution networks for semantic segmentation. arXiv arXiv:1804.01033, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, J. RPPG-Toolbox: A Benchmark for Remote PPG Methods. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 70, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDuff, D.; Estepp, M.; Piasecki, N.; Blackford, E. Remote physiological measurement: Opportunities and challenges. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2017, 6, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.F.; Martins, A. Sparse attentive backtracking and the alpha-entmax. arXiv arXiv:1905.05055, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Agrafioti, F.; Mayosi, B.; Tarassenko, L. Robust emotion recognition from physiological signals using spectral features. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 9-13 July 2012; pp. 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.; Tarassenko, L. Capturing the Multi-Scale Temporal Dynamics of Physiological Signals using a Temporal Convolutional Network for Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction Workshops (ACIIW), Cambridge, UK, 3-6 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbetta, M.; Shulman, G.L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 8, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, F.; Ding, Y.; Liu, T. Gated pooling for convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2020, 30, 2201–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, M.; Lichtenauer, J.; Pun, T.; Pantic, M. A multimodal database for affect recognition in response to movies. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2012, 3, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akselrod, S.; Gordon, D.; Ubel, J.B.; Shannon, D.C.; Berger, A.C.; Cohen, R.J. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate fluctuation: a quantitative probe of beat-to-beat cardiovascular control. Science 1981, 213, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantriglia, F.; Morabito, F.C. A Survey on Remote Photoplethysmography and Its Applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; den Brinker, A.C.; Stuijk, S.; de Haan, G. Algorithmic principles of remote PPG. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 64, 2757–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhou, J. PhysNet: A Deep Learning Framework for Remote Physiological Measurement From Face Videos. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2020, 30, 2852–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J.; Han, H.; Zhao, Y. Emotion Recognition from Remote Photoplethysmography: A Review. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2023, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, R.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J. PhysFormer++: Robust Remote Physiological Measurement Guided by Multi-scale Fusion and Noise Modeling. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, R.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J. PhysFormer: Robust Remote Physiological Measurement via Transformer. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 8686–8704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Schinle, M.; Stork, W. Dimensional emotion recognition from camera-based PRV features. Methods 2023, 218, 224-232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Morales, J.; Guixeres, J.; Cebrián, M.; Alcañiz, M.; Chicchi Giglioli, I.A. Affective Computing in Virtual Reality: Emotion Recognition from Physiological Signals Using Machine Learning and a Novel Open Dataset. Sensors 2021, 21, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Xie, Y.; Yu, Z. PhysMamba: Efficient Remote Physiological Measurement with SlowFast Temporal Difference Mamba. arXiv arXiv:2409.12031, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Valenza, G.; Lanata, A.; Padgett, L.; Thayer, J.F.; Scilingo, E.P. Instantaneous autonomic evaluation during affective elicitation. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 22, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talala, F.; Bazi, Y.; Al Rahhal, M.M.; Al-Jandan, B. Emotion Classification Based on Pulsatile Images Extracted from Short Facial Videos via Deep Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Gallagher, P.; Tu, Z. Generalizing Pooling Functions in CNNs: Mixed, Gated, and Tree. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Chen, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J. RhythmFormer: Extracting rPPG Signals Based on Hierarchical Temporal Periodic Transformer. arXiv arXiv:2402.12788, 2024.

- Briggs, F.; Mangun, G.R.; Usrey, W.M. Attention enhances Synaptic Efficacy and Signal-to-Noise in Neural Circuits. Nature 2013, 499, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengio, Y.; Louradour, J.; Collobert, R.; Weston, J. Curriculum learning. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Montreal, QC, Canada, 14-18 June 2009; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, W.; Kochiyama, T. Dynamic relationships of peripheral physiological activity with subjective emotional experience. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 837085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, X.; Arslan, O.; Bilgin, G.; Al Machot, F. Emotion recognition from physiological signals: a review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Human Computer Interaction, Halifax, NS, Canada, 5-7 December 2018; pp. 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).