1. Background

Patients who are admitted to the shock room in the emergency departments are considered as the most medically severe patients upon their arrival to the hospital, frequently due to respiratory and/or hemodynamic instability, or an immediate life-threatining condition. Consequently, treatment of those patients should be urgent and cannot be delayed. Rapid diagnosis and appropriate treatment may reduce morbidity and mortality among these patients who are considered as critically-ill patients, and to improve their survival [

1,

2,

3]. In previous studies, a direct relationship was found between delaying the identification of the critical ill patients and their referral to the various appropriate intensive care units (ICU), which was primarily linked to a poor outcome [

4,

5,

6]. In the study of Rivers et al., approximately 16% reduction in mortality was reported in patients with severe sepsis who received early intensive treatment in the emergency department, compared to other patients who received the standard therapy [

1]. It was also stated in several studies that there was a great importance and improvement in outcomes by the fast and effective management of various types of severely-ill patients arriving to the emergency department, including cases of severe trauma, acute coronary syndrome, post-surgeries and other conditions [

1,

2,

3,

7].

In a prospective cohort outlined by Nguyen et al., approximately 300 patients with severe sepsis were followed. Significant reduction in mortality was noted in patients monitored by continuous central venous pressure, those who were administered broad-spectrum antibiotics within 4 hours of the their admission, those who were treated for sepsis within 6 hours of admission, those who have received steroid treatment while on vasopressor therapy, and in subjects with lactic acid level monitoring [

8].

In another study, Sebat et al. reported that the implementation of a special program in the hospital for early detection and rapid treatment of non-traumatic shock states, resulted in improved mortality rates compared to a group of patients who received the standard treatment [

9,

10]. Similarly, in a study conducted by McQuillan et al., it was shown that sub-optimal and delayed treatment of critically ill patients in the emergency department before their transfer to the appropriately designated intensive care units, affected their long-term morbidity and even increased their mortality later on. In addition, these patients had to stay for a longer duration in the various intensive care units in the hospital [

11]. It is also worth noting, that previous studies demonstrated that the referral of patients from the emergency department to the various intensive care units in the hospital, and in particular from the shock room, was accompanied by lower mortality rates compared to patients who were referred from other departments to the intensive care units of the hospital [

12,

13,

14].

Therefore, it is of utmost importance to identify patients with medical emergencies as early as possible, to make the true diagnosis, to start appropriate treatment, and to transfer them urgently to the designated facility, such as the "shock room" in the emergency department. Studies even showed that this may improve the patients' recovery rates [

15], especially in various shock states such as decrease in blood volume, cardiac failure, peripheral vascular dilatation, or increased metabolism [

2].

In another study which examined 525 patients with various malignancies who were hospitalized in intensive care units for various reasons (respiratory failure, severe sepsis or septic shock), it was shown that early intervention significantly and unequivocally reduced mortality after approximately one year following their index hospitalization [

16]. In the same study, the patients were divided into two groups- those who were treated with an early therapeutic intervention in less than 1.5 hours, compared to patients who were treated after more than 1.5 hours upon arrival to the emergency department. The parameters that were investigated were as follows: providing rapid medical response and treatment by the staff of the emergency department, the length of stay in the emergency department until arrival to the target intensive care unit, the patient's functional condition, the status and severity of the malignant disease, three abnormal physiological variables, and the need for mechanical ventilation.

In consequence with these data, our aim was to investigate the probabilty of survivng hospitalization following treatment in the shock room in relation to several factors, and hypothesized that the length of stay in the shock room for up to four hours will be a associated with a better prognosis and lower mortality rates, compared to patients who stay more than four hours in the shock room. Accordingly, we conducted the current study aiming to evaluate the survival rates of patients admiied to the hospital wards after being treated in the shock room in our tertiary medical center, depending on their stay in the sock room (in hours), besides additional parameters which included age and gender of the patient, background medical conditions, admission to the emergency department following out of hospital mechanical ventilation, the main etiology of the medical emergency which leaded to the treatment in the shock room (respiratory, cardiac, infectious, neurologic, hemato-oncologic, or following intoxication), and systolic blood pressure and body temperature at time of admission to the shock room.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

In accordance with the approval of the local ethics committee (RMB 0724/19), we retrospectively reviewed the medical files of patients who were treated in the shock room of the emergency department (ER) at Rambam health care campus, a tertiary medical center in northern Israel, between 1.1.2018 and 31.12.2019. Due to the fact that it was a retrospective non-interventional study, an exemption from signing an informed consent form was received from the institutional ethics committee. Patients were included in the study in case they were eligible according to the following criteria: patients who were admitted to the emergency department and treated in the shock room during the years mentioned above, were at least 18 years old at time of admission, have arrived alive to the shock room, and survived their stay in the shock room. Subjects were not eligible to be enrolled into the study in case of death upon arrival to the hospital, were admitted to the shock room following multiple trauma, a patient that did not survive his stay in the shock room, or in case patients found unsuitable for performing resuscitation for any reason at the discretion of the attending physician (patients defined as DNR= Do not Resuscitate).

We assessed files of the patients, while the end point was mortality of patients who were hospitalized after being treated in the shock room of the emergency department. Non-dependent parameters tested in the study included age, gender, medical history- diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic respiratory diseases, chronic kidney failure, malignant diseases, chronic inflammatory diseases, patients treated with immunosuppressive agents on regular basis- transplanted or treated with long-term steroids or immuno-suppressants, or treated with biological treatment on a regular basis.

The etiologies of the event that necessitated treatment in the shock room were divided as follows. Respiratory failure- following asthmatic attacks or exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiac causes- including acute coronary events, decompensation of CHF or hemodynamically unstable cardiac arrhythmias, infectious diseases- mainly severe sepsis or septic shock, neurological diseases- convulsions, stroke or meningo-encephalitis, patients suffering from hematological malignancies or oncological diseases, and patients who have been exposed to toxins/poisons of any kind.

For each patient we assessed the length of stay in the shock room in hours, and divided the study population into two groups- those who were treated for up to four hours, and those who stayed for more than four hours. We then assessed the survival of the subjects at discharge from hospital following the index event, and included in the statistical analysis those who survived their stay in the shock room and were admitted for hospital departments. We then documented the outcome of the hospitalization following the index event- death versus survival.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 28 (IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0.1, Armonk, New York, United States). Descriptive statistics were reported by using averages, percentages and standard deviation for all patients who were included in the study. We used logistic regression model and the Fisher Exact Test to determine the correlation between the outcome (survival or death) with each of the independent factors studied, and compared the outcome of the hospitalization referring to the length of stay in the shock room- up to four hours compared to more than four hours. P<0.05 is considered statistically significant.

3. Results

After reviewing hospital files of 400 patients, our study included 101 eligible patients who were treated in the shock room at Rambam health care campus emergency department between 01/JAN/2018 and 31/DEC/2019. The average age of the patients was 68±20 years (range 18-100 years), of which there were 50 men (49.5%) and 51 women (50.5). The average length of stay in the shock room was 4.69±4.3 hours, with 48 of them (47.5%) staying up to 4 hours (average 1.8±1 hours) and 53 patients (52.5%) staying in the shock room for more than 4 hours (average 7.8±4.3 hours). 16 patients (16%) arrived to the emergency department on invasive ventilators following out of hospital resuscitation.

In total, 60 patients (60%) did not survive the hospitalization eventually. The characteristics of the patients and their medical background are detailed in

Table 1. Compared to the patients who stayed more than 4 hours in the shock room, patients that stayed up to 4 hours were more likely to have the diagnosis if ischemic heart disease in their medical history (41.3% compared to 12%, respectively, p=0.03), and less likely to have chronic kidney disease (15.2% compared to 37%, respectively, p=0.02) or chronic lung diseases (6% compared to 25.6%, respectively, p=0.001).

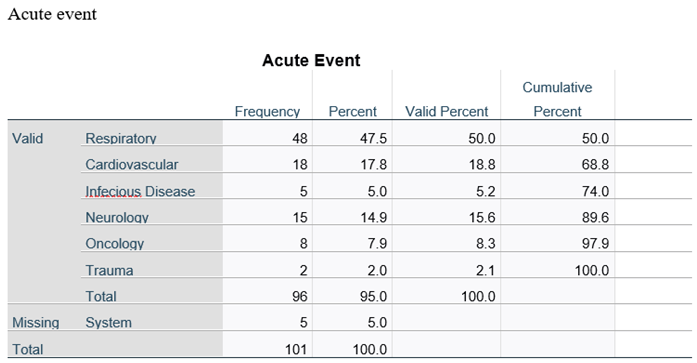

The etiologies for which the patients were treated in the shock room are shown in

Table 2. In 48% of the cases, patients were treated in the shock room for morbidities related to the respiratory system that included respiratory failure as a result of asthma attacks, exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or other lung diseases such as interstitial lung disease or lung fibrosis). Other etiologies for the acute event necessitating treatment in the shock room were diseases of the cardiovascular system (18%), neurological diseases that included convulsions, cerebro-vascular events, meningitis or encephalitis (15%), emergencies related to oncological diseases (8%), infectious diseases (5%), or trauma together with other acute morbidity (2%). For 5 patients (5%), the reason for the treatment in the shock room was multi-systemic or not clearly determined.

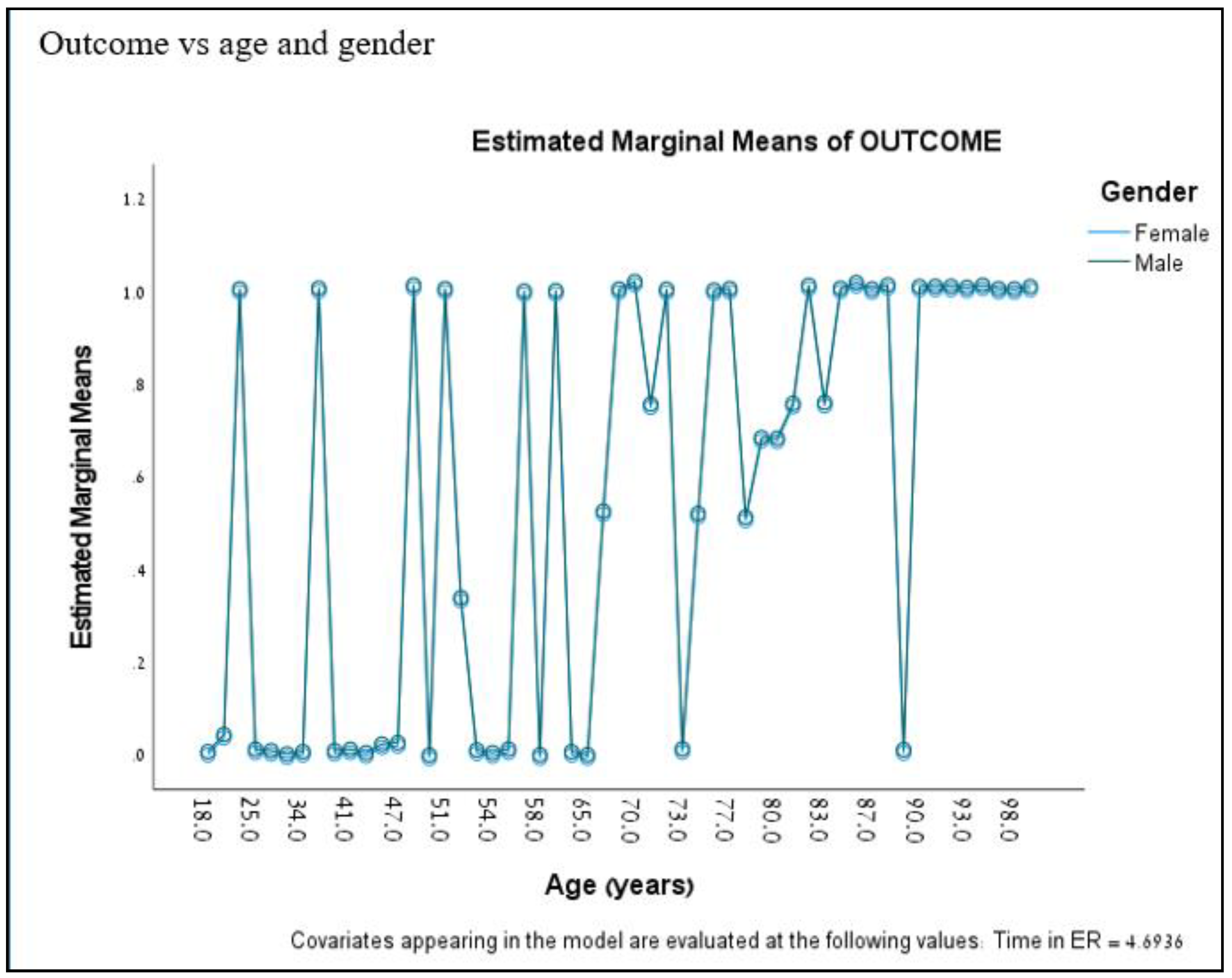

By performing a multivariate logistic regression, it was found that only age was associated with the probability of the determined outcome (mortality), when the age threshold value was 65 years. By comparing the patients in the age groups of up to 65 or over 65 years, mortality was found to be 34% versus 75% respectively, p=0.046 (

Figure 1).

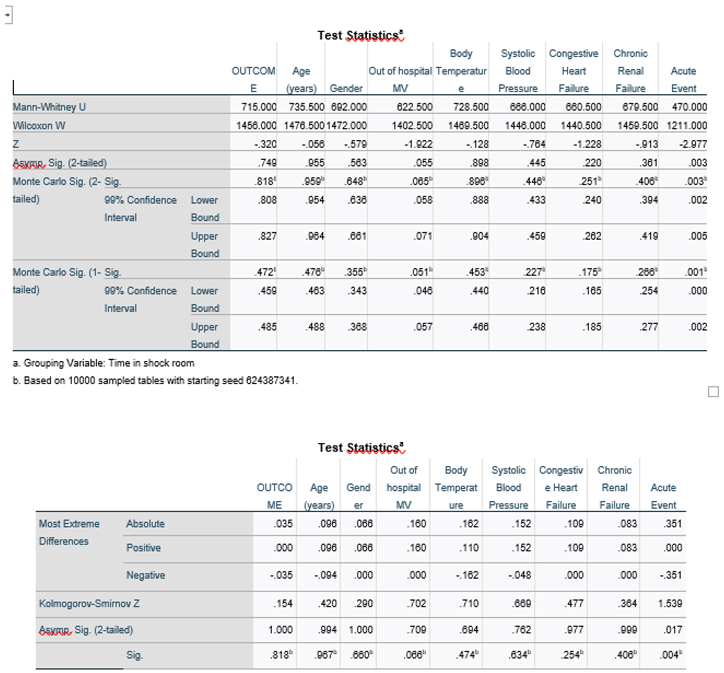

16 patients arrived in the shock room while on mechanical ventilation following out-of-hospital rssuscitation, which also was associated with higher mortality rates compared to patients who arrived in the shock room without mechanical ventilation. In those patients, there were 11 (68.8%) deaths and 5 (31.2%) survival cases, with similar borderline statistical significance regardless of duration of stay in the shock room for up to four hours or more than four hours (p=0.055 and 0.051, respectively). No correlation was found between the other investigated factors and mortality, while these factors included the gender of the patient (p=0.35), the reason why the patient was treated in the shock room (p-value had nosignificance for all), the average blood pressure (p=0.23) and body temperature (p=0.45) that were measured at time of admission in the shock room (

Table 3).

4. Discussion & Conclusions

Previous works have shown that in patients who arrive to the emergency department with medical emergencies that necessitate intensive treatment in the shock room, length of stay in the shock room has an impact on their upcoming survival following the acute event. In our study, we investigated the impact of length of stay in the shock room besides additional factors on survival rate, and hypothesized that length of stay for up to four hours will be accompanied by better survival rates than staying for longer than four hours. We demonstrated that the main effect on the outcome was the patient's age, with a significantly higher mortality rate observed among patients over 65 years of age compared to patients up to 65 years of age, p=0.046. Indeed, in patients with the age over 90 years (n=11), all subjects who were treated in the shock room deceased during the hospitalizaion following the index event. In addition, patients who arrived to the shock room with mechanical ventilation following out-of-hospital resuscitation, also a worse prognosis was observed, with lower chances for survival compared to those who arrived to the shock room with no out of hospital mechanical ventilation, with borderline statistical significance (p=0.051).

The results of our study are in line with the publication of Dae-Sang Lee et al, in which a better prognosis was demonstrated in patients treated in the emergency separtment as a function of the time spent in the shock room, when the threshold of time spent in the shock room was up to 1.5 hours compared to more than 1.5 hours (16).

In our study, no effect on survival was found for the underlying diseases of the patient, gender, or the reasons for their treatment in the shock room. Of note is the shorter time of stay in the shock room in subjects arriving with a history of ischemic heart disease compared to other emergencies (41.3% up to four hours compared to 12% for more than four hours).

In conclusion, among the patients who survive treatment in the shock room and are admitted to hospital afterwards, the chances of survival are better for those under the age of 65 compared to patients over the age of 65, and for patients who arrive unventilated to the emergency room, compared to those who arrive with mechanical ventilation following out-of-hospital rescussitation. Indeed, the probability of survival in subjects 90-years-old or more is neglectable, regardless of the acute event with which they were presented.

4.1. Study Limitations

- ○

The number of patients is relatively small. When calculating the sample size, in order to distinguish the differences in survival, at least 50 patients were required in each group according to the etiology leading to treatment in the shock room, but we could not reach these numbers due to the lack of sufficient data for all the patient files reviewed, and many patient files that were reviewed did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the study. We did reach enough numbers in the groups of gender, history of hypertension, and length of stay in the shock room.

- ○

Rambam health care campus, where the work was conducted, is the main tertiary medical center in the northern area of the country. Since this is a tertiary care hospital, patients are often referred with more difficult and complicated conditions compared to other hospitals nearby, therefore their prognosis is usually worst. This could explain the lack of a significant difference in the survival chances of the patients in the different groups according to their length of stay in the shock room, and for the high mortality rate among patients who were after being treated in the shock room.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Shadi Hamoud; Methodology, Salam Ghanaem, Hisam Zaidani, Jubran Bolus, Ahmad Hassan and Shadi Hamoud; Software, Shadi Hamoud; Validation, Shadi Hamoud; Formal analysis, Salam Ghanaem and Shadi Hamoud; Investigation, Yousef Shukha, Salam Ghanaem, Hisam Zaidani and Shadi Hamoud; Resources, Shadi Hamoud; Data curation, Ahmad Hassan and Shadi Hamoud; Writing – original draft, Salam Ghanaem; Writing – review & editing, Yousef Shukha and Shadi Hamoud; Visualization, Hisam Zaidani, Jubran Bolus and Ahmad Hassan; Supervision, Shadi Hamoud; Funding acquisition, Shadi Hamoud.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

References

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M; Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 8;345(19):1368-77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giugliano RP, Newby LK, Harrington RA, Gibson CM, Van de Werf F, Armstrong P, Montalescot G, Gilbert J, Strony JT, Califf RM, Braunwald E; EARLY ACS Steering Committee. The early glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (EARLY ACS) trial: a randomized placebo-controlled trial evaluating the clinical benefits of early front-loaded eptifibatide in the treatment of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome--study design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2005 Jun;149(6):994-1002. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, Light B, Parrillo JE, Sharma S, Suppes R, Feinstein D, Zanotti S, Taiberg L, Gurka D, Kumar A, Cheang M. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006 Jun;34(6):1589-96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkhe M, Myles PS, Leach DS, Maclean AV. Outcome of emergency department patients with delayed admission to an intensive care unit. Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2002 Mar;14(1):50-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalfin DB, Trzeciak S, Likourezos A, Baumann BM, Dellinger RP; DELAY-ED study group. Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007 Jun;35(6):1477-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piagnerelli M, Van Nuffelen M, Maetens Y, Lheureux P, Vincent JL. A 'shock room' for early management of the acutely ill. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009 May;37(3):426-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhard M, Becker TK, Nowe T, Mohorovicic M, Sikinger M, Brenner T, Richter GM, Radeleff B, Meeder PJ, Büchler MW, Böttiger BW, Martin E, Gries A. Introduction of a treatment algorithm can improve the early management of emergency patients in the resuscitation room. Resuscitation. 2007 Jun;73(3):362-73. Epub 2007 Feb 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen HB, Corbett SW, Steele R, Banta J, Clark RT, Hayes SR, Edwards J, Cho TW, Wittlake WA. Implementation of a bundle of quality indicators for the early management of severe sepsis and septic shock is associated with decreased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2007 Apr;35(4):1105-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebat F, Johnson D, Musthafa AA, Watnik M, Moore S, Henry K, Saari M. A multidisciplinary community hospital program for early and rapid resuscitation of shock in nontrauma patients. Chest. 2005 May;127(5):1729-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebat F, Musthafa AA, Johnson D, Kramer AA, Shoffner D, Eliason M, Henry K, Spurlock B. Effect of a rapid response system for patients in shock on time to treatment and mortality during 5 years. Crit Care Med. 2007 Nov;35(11):2568-75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuillan P, Pilkington S, Allan A, Taylor B, Short A, Morgan G, Nielsen M, Barrett D, Smith G, Collins CH. Confidential inquiry into quality of care before admission to intensive care. BMJ. 1998 Jun 20;316(7148):1853-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7148.1853. Erratum in: BMJ 1998 Sep 5;317(7159):631. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goldhill DR, Sumner A. Outcome of intensive care patients in a group of British intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 1998 Aug;26(8):1337-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkhe M, Myles PS, Leach DS, Maclean AV. Outcome of emergency department patients with delayed admission to an intensive care unit. Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2002 Mar;14(1):50-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbe CP, Williams E, Fligelstone L, Gemmell L. Does earlier detection of critically ill patients on surgical wards lead to better outcomes? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005 Jul;87(4):226-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Beal AL, Cerra FB. Multiple organ failure syndrome in the 1990s. Systemic inflammatory response and organ dysfunction. JAMA. 1994 Jan 19;271(3):226-33. [PubMed]

- Lee DS, Suh GY, Ryu JA, Chung CR, Yang JH, Park CM, Jeon K. Effect of Early Intervention on Long-Term Outcomes of Critically Ill Cancer Patients Admitted to ICUs. Crit Care Med. 2015 Jul;43(7):1439-48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).