1. Introduction

Serratus Anterior Muscle Pain Syndrome (SAMPS) is an infrequent cause of anterior chest wall pain [1]. This syndrome is characterized by pain overlying the fifth to seventh ribs in the mid-axillary line, with referred pain that may radiate down the ipsilateral upper extremity into the palmar aspects of the ring and little fingers, as well as the lower inner side of the shoulder blade [2]. SAMPS, often attributed to myofascial trigger points of the serratus anterior muscle (SAM) or dysfunction of the Long Thoracic Nerve (LTN), can lead to significant disability, affecting ipsilateral upper limb movement and quality of life. SAMPS on left side of the body can mimic the pain of myocardial infarction and is frequently misdiagnosed as such. The intensity of the pain is typically mild to moderate and intermittent, often described as chronic deep, sharp, and aching in character[2]. Patients may present as weakness in the ipsilateral shoulder and upper limb, especially during flexion and abduction.

Anatomy of SAM and LTN

The Serratus Anterior muscle (SAM) originates from the outer surfaces of the first to ninth ribs and the fascia covering the external intercostal muscles. Its fibers travel posteriorly and medially around the thoracic cage, inserting along the entire length of the medial border of the scapula. The SAM is situated superficially to the first nine ribs and the fascia of the external intercostal muscles, and deep to the scapula, latissimus dorsi, trapezius, and subscapularis muscles, as well as the fascia containing the long thoracic nerve. It is also located posterior to the pectoralis major and minor muscles. The SAM contributes to the formation of the medial wall of the axilla. Notably, its lower fibers interdigitate with the upper fibers of the external abdominal oblique muscle, establishing a biotensegrity connection to the abdominal muscles [3].

The primary functions of the SAM include protracting and upwardly rotating the pectoral (shoulder) girdle at the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints. Additionally, it helps stabilize the scapula against the thoracic wall [4].

In terms of innervation, the SAM is supplied by the long thoracic nerve (LTN) (C5-C7). Its blood supply is derived from the superior and lateral thoracic arteries, as well as the thoracodorsal arteries.

Due to its involvement in punching and pushing movements, the SAM is often referred to as the "boxer's muscle." To test its function, the patient is asked to hold their shoulder in flexion and their elbow in extension, then push their upper limb against a wall. During this action, the muscle can be visually observed and palpated. In cases where the SAM is weakened or paralyzed from LTN impingement or entrapment, the medial border of the scapula becomes prominent on the upper back, a condition known as "winged scapula" [5].

The Long Thoracic Nerve (LTN) arises from the anterior rami of the fifth to seventh cervical nerves (specifically the C5, C6, and C7 roots of the brachial plexus). It descends along the lateral margin of the ribs, approximately at the mid-axillary line. Traveling along the superficial surface of the Serratus Anterior muscle, the LTN innervates each of its muscle slips. Entrapment of the LTN within the fascia of the Serratus Anterior may lead to conditions such as winged scapula or Serratus Anterior Muscle Palsy (SAMPS).

Herein, we report the first case in the literature of a 72-year-old male patient who experienced chronic SAMPS for three years and had failed conventional treatments. He was successfully diagnosed using SDP and effectively treated with ultrasound-guided hydrodissection of the LTN using D5W without LA.

2. Case Presentation

A 72-year-old male was referred from a cardiologist to the Rehabilitation Clinic with persistent pain in the left chest radiating to the upper back. His medical history included two Percutaneous Coronary Interventions (PCIs), the first in Japan approximately 10 years ago and the second in Singapore several years ago. The patient regularly takes heart medicine prescribed by his cardiologist. The most recent CT Coronary Angiography (dated16/12/24) revealed a stent in the ostial proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery , with mild disease distal to the stent, mild disease at proximal RCA, and normal origins of the coronary arteries. A recent CT Thorax without contrast showed normal heart and lungs, central trachea, normal diaphragm, and no fractures of costae, sternum, clavicle, or thoracic vertebrae.

The pain had been persisting for approximately three years, beginning after a fall during a rafting excursion. Since that incident, the patient complained of pain in the left chest, radiating to the left back. The pain had been insidious in onset, with an intensity of 6/10 on the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) for the past three years. However, in the last two weeks, the pain had worsened to 9/10 after the patient pushed a trolley. That severe pain had significantly affected his sleep and daily activities.

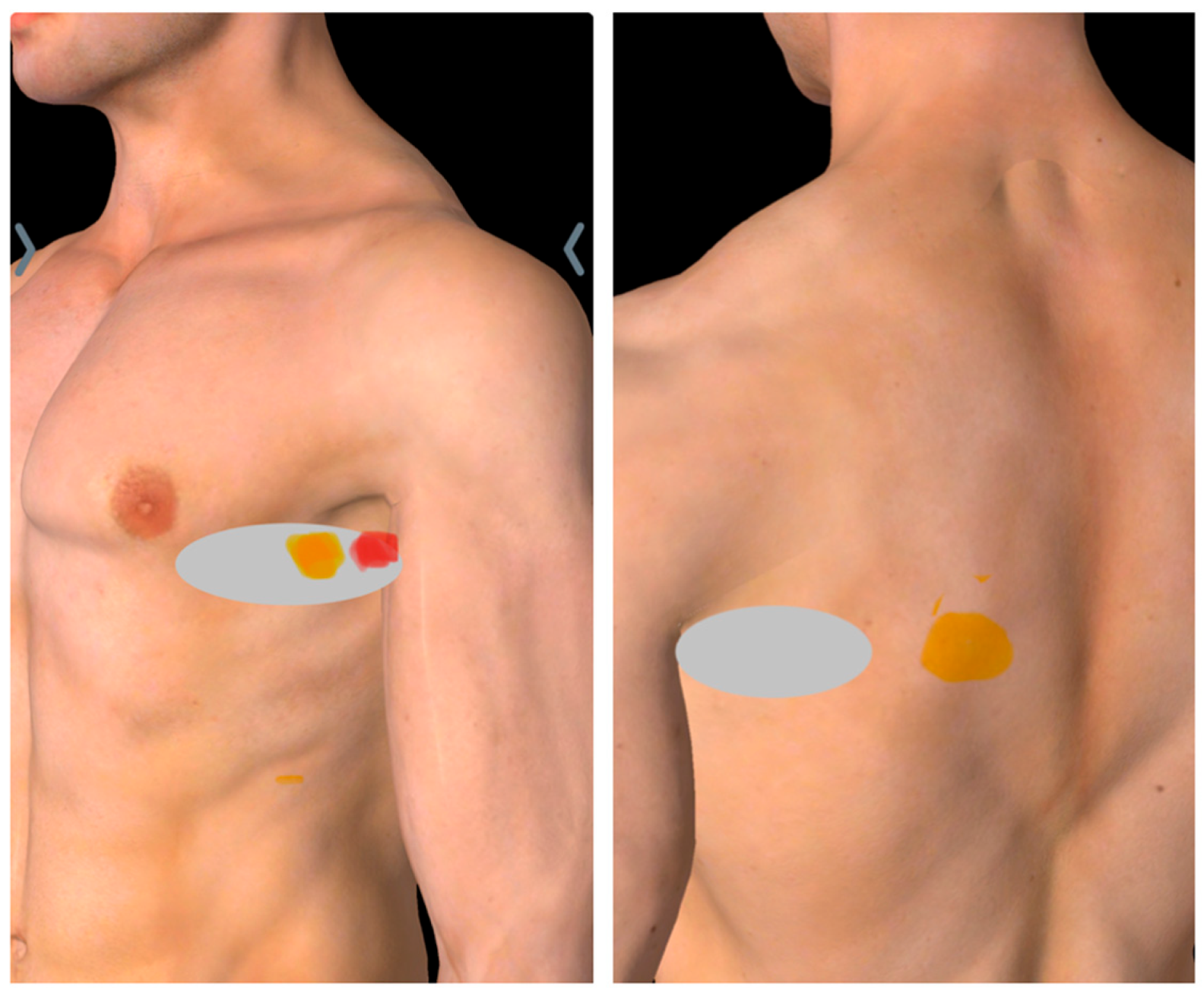

The patient reported experiencing pain on the left side of the ribcage, in the left armpit, and the lower inner side of the ipsilateral shoulder blade, with occasional radiation down the inner side of arm (

Figure 1). He described the pain as similar to that experienced during a previous heart attack, which led him to consult a cardiologist; however, examination results were found to be normal. He reported sharp pain and tenderness upon touching or pressing the affected area. The pain worsened with movements involving forward flexion or protraction of the shoulder, while relief occurred when he extended or retracted the shoulder. His pain was temporarily alleviated by medication and massage.

Upon physical examination, his vital signs were within normal ranges, but his pain level was rated as 9/10 on the NRS. The patient appeared to be in severe discomfort, frequently rubbing his hand over his left chest. His posture was forward-slouched, although he sometimes pulled his chest and back backward to reduce pain. Chest wall symmetry was normal, with no scar, or retractions. He demonstrated a full range of motion in both the cervical spine and shoulder girdle, with increased pain during forward shoulder flexion or protraction but no signs of scapular winging. The patient was able to localize his pain, with tenderness observed along the anterior axillary line over the 5

Th rib, and a positive jump sign in the mid-axillary line at the same rib level (

Figure 1).

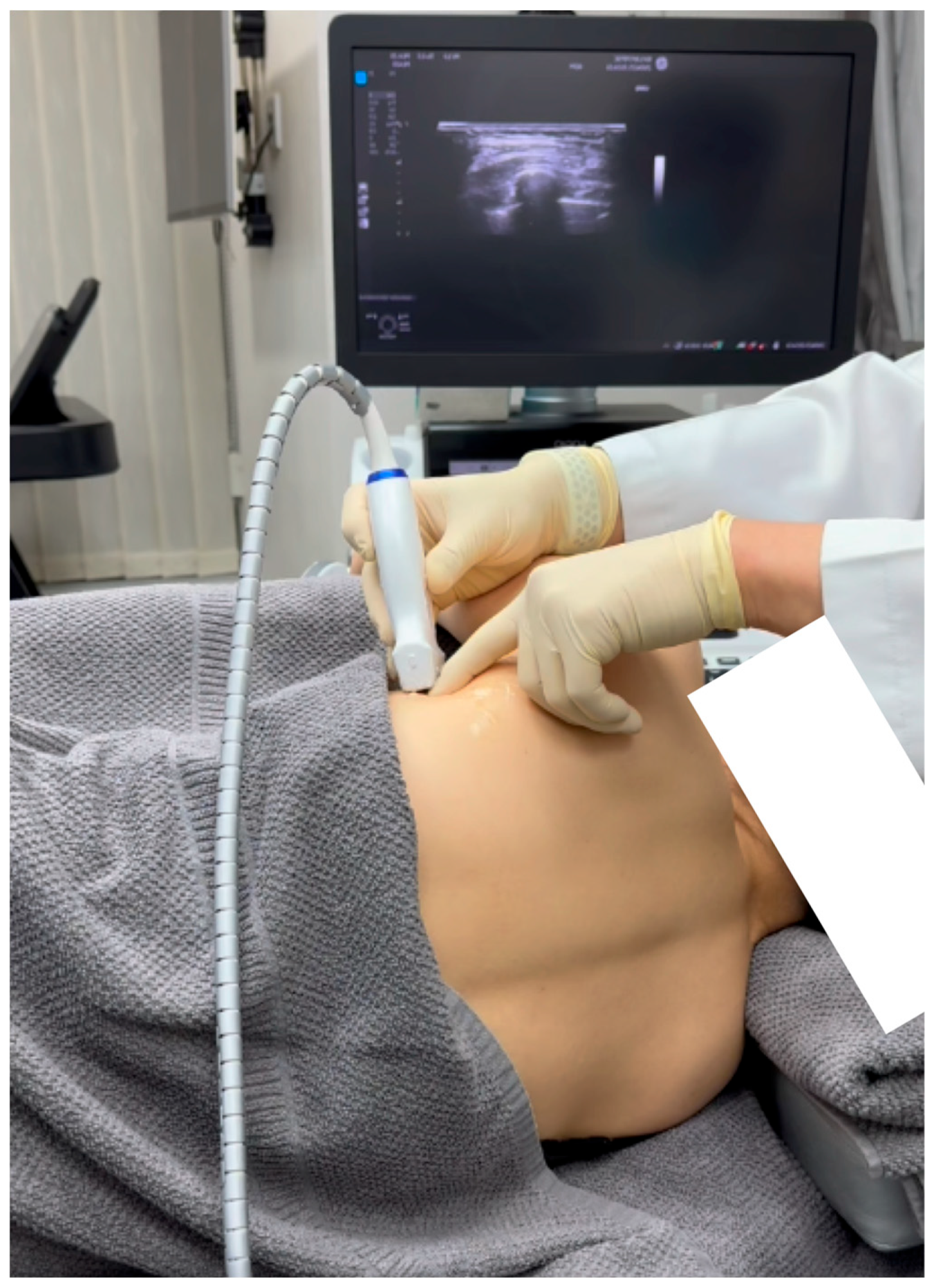

2.1. Diagnosis of SAMPS Using Sonoguided Digital Palpation

Sonoguided Digital Palpation was used to assist in diagnosing and visualizing the suspected lesions associated the SAMPS

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, Video 1.

Sonoguided Digital Palpation (SDP) serves as a dynamic tool to utilize a layered palpation technique under ultrasound guidance[6,7]. This allows for the visualization and diagnosis of changes in the tension or friction of the fascia, specifically the serratus anterior fascia (SAF) in this patient. An excessive displacement or gliding restriction of the SAF relative to the superficial latissimus dorsi fascia may signify fascial defects, as illustrated in Video 1. This technique has the advantage of real-time comparison with the contralateral side as a control.

Video 1 shows the sonographic appearance of the normal Serratus Anterior Muscle (SAM) and Serratus Anterior Fascia (SAF), along with the painful long thoracic nerve (LTN). Repeated digital palpation of the LTN during Sonoguided Digital Palpation (SDP) reproduced the patient’s concordant pain associated with Serratus Anterior Muscle Pain Syndrome (SAMPS).

The excessive movement of the SAF may contribute to the development of trigger points in the serratus anterior muscle (SAM) as a compensatory mechanism.

SDP can also be selectively used to palpate the long thoracic nerve (LTN) and the lateral thoracic artery, which are located within the SAF and superficial to the SAM. Digital compression over the LTN that reproduces the patient's concordant pain, as opposed to compression on the thoracodorsal nerve, and deeper palpation to elicit a twitching response in the SAM trigger points, may help to differentiate the root cause of the neuropathic pain in the locality.

Sonoguided digital palpation (SDP) reproduced the patient's concordant pain. With sustained pressure, some referral pain to the shoulder and medial upper limb was also reproduced.

2.2. Ultrasound-Guided Hydrodissection of Long Thoracic Nerve to Treat the Entrapped Segment: Method

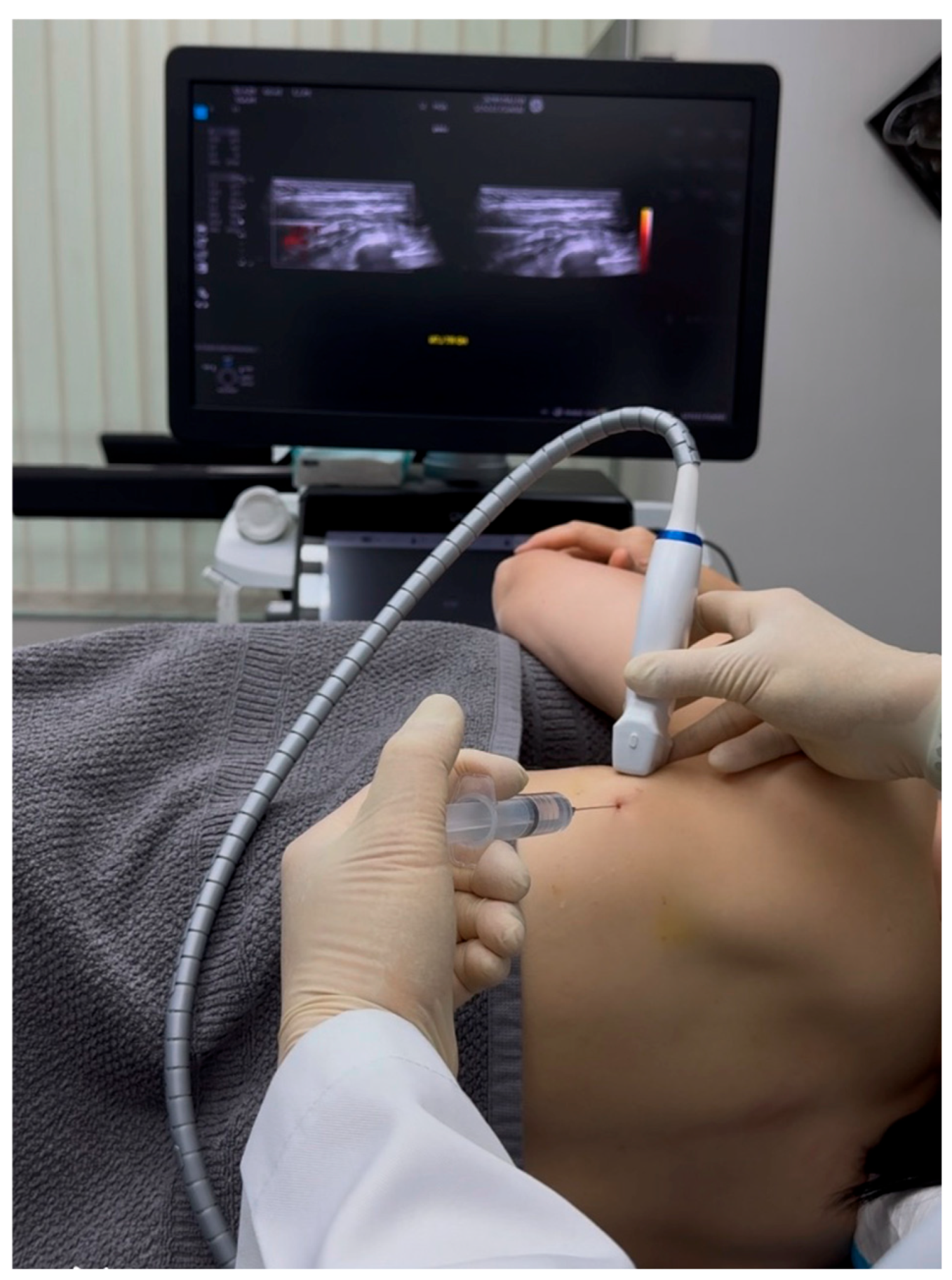

Since the patient had failed all previous conventional treatments and the suspected lesion identified through Sonoguided Digital Palpation (SDP) was the long thoracic nerve (LTN), we proposed ultrasound-guided hydrodissection of the LTN. Informed consent was obtained, and the patient agreed to participate in this study. The cardiologist approved the treatment on the condition that the patient discontinue anticoagulant medication five days prior to the procedure.

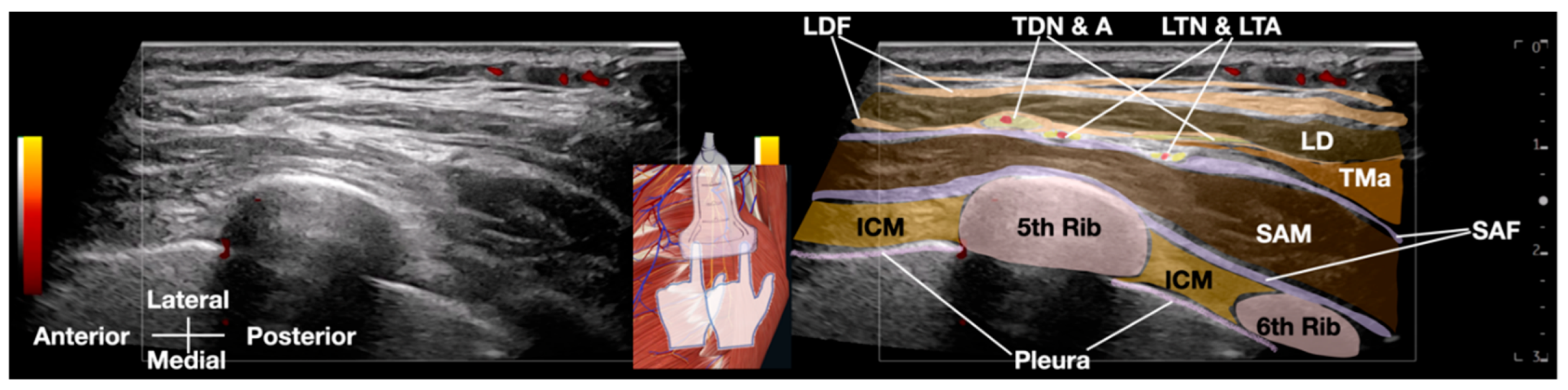

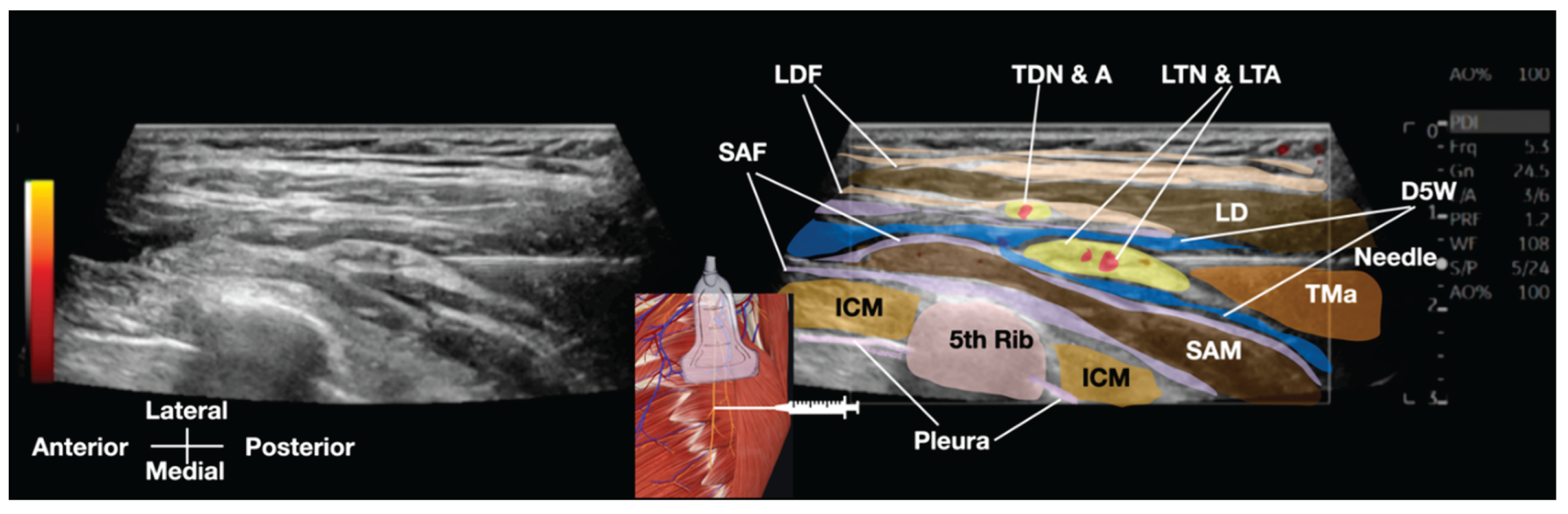

Standard IV lines and monitors were prepared, and a GE high-frequency linear transducer (10-12 MHz) was utilized for the procedure. The field was made sterile, and local anesthesia was administered to the skin. A Braun 25-G (occasionally, 23G and even 22-G needles can also be used) x 3.5 inch needle was used, along with 20 to 30 cc of D5W as the hydrodissection solution. (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 and Video 2)

Video 2: This Video demonstrates the ultrasound-guided hydrodissection of the long thoracic nerve using 20cc of 5% dextrose with no local anesthesia. D5W, 5% dextrose water; ICM, intercostal muscle; LD, latissimus dorsi muscle; LDF, latissimus dorsi fascia; LTN & LTA, long thoracic nerve and lateral thoracic artery; SAM, serratus anterior muscle; SAF, serratus anterior fascia; TDN & A, thoracodorsal nerve and artery; TMa, teres major muscle

Watch Video Here:

Hydrodissection was performed by injecting a solution to separate soft tissues ahead of the needle, creating a visible 'halo' that guided needle placement [8]. The fascial plane between the latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles was opened by the injected fluid. Using a 'fascial unzipping' technique, a precise injection of 20-30 cc of 5% dextrose (without local anesthetic) was administered within the fascial plane surrounding the long thoracic nerve (LTN) until muscle and fascial layer separation was achieved. The transducer and needle is then pivoted from the same entry point to hydrodissect more proximal or distal aspects of the LTN, requiring up to 50 cc of 5% dextrose to fully cover the serratus anterior fascia (SAF) and suspend the LTN within the dextrose solution. The procedure's endpoint was confirmed by a significant reduction in the patient's usual pain to a satisfactory level (typically below 3/10 on a numerical rating scale), free movement of the ipsilateral shoulder and arm, and the absence of pain with SDP. In this patient, pain immediately reduced to 1/10 on the NRS after freeing the LTN from surrounding tissues. The treated nerve segment was approximately the same length as the ultrasound transducer.

Post-procedure, the patient's vital signs remained stable. No bruising occurred, and injection-related swelling subsided within 10 minutes. No complications or adverse effects were observed during the procedure or the observation period, and the patient was subsequently discharged. At follow-up appointments at 1 month, 2 months, 6 months, and 12 months, the patient reported minimal to no pain, and SDP did not elicit any positive signs.

3. Review of Serratus Anterior Muscle Pain Syndrome

Serratus anterior muscle pain syndrome (SAMPS) is a condition characterized by pain and dysfunction of the serratus anterior muscle, which can lead to significant chest pain, scapular dyskinesis, and functional limitations. This review synthesizes recent literature on the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of SAMPS, emphasizing the importance of a multifaceted approach to management.

3.1. Etiology and Clinical Presentation

The etiology of SAMPS can vary widely, encompassing factors such as overuse, strain, or direct trauma. A notable case report by Elders et al. (2001) illustrates how serratus anterior palsy can arise as an occupational disease, particularly in scaffolders, due to repetitive strain and mechanical pressure leading to nerve damage and muscle paralysis[9]. Additionally, Bagcier and Yurdakul (2021) emphasize that myofascial trigger points in the serratus anterior can mimic cardiac pain[10], underscoring the need for careful differential diagnosis when patients present with chest pain.

Patients with SAMPS often report symptoms such as localized pain in the anterior thorax, scapular winging, and difficulty with overhead activities. The pain may be exacerbated by specific movements or postures, particularly those involving shoulder elevation or protraction. This condition can significantly impact daily activities and quality of life, making early recognition and intervention crucial.

3.2. Diagnosis

Diagnosing SAMPS can be challenging due to its overlapping symptoms with other conditions. Bautista et al. (2017) refer to it as a "diagnostic conundrum," indicating that it is often overlooked in clinical practice[1]. A thorough clinical history and physical examination are essential, focusing on the assessment of scapular motion and muscle strength.

Currently, the diagnosis of SAMPS predominantly relies on a process of exclusion, necessitating the ruling out of other potential etiologies for chest and shoulder pain, in conjunction with a comprehensive physical examination. This diagnostic methodology typically encompasses a thorough assessment of the patient's medical history, palpation for tender points indicative of muscle dysfunction, and the employment of clinical maneuvres to reproduce specific symptoms. Unfortunately, the absence of definitive diagnostic tests or biomarkers uniquely associated with SAMPS complicates the accurate identification of this condition. There is a pressing clinical need for a readily accessible and easily usable diagnostic method for SAMPS, which can facilitate timely and accurate diagnosis, ultimately leading to effective management and treatment of this complex condition. Sonoguided digital palpation has been reported by Lam et al. as a bridge between traditional clinical musculoskeletal palpation and imaging diagnosis [6,7]. It fully utilizes the advantages of Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS), including dynamic ultrasound without radiation, allowing for direct visualization of the suspected lesions and the reproduction of the patient's concordant pain.

The use of ultrasound has emerged as a valuable diagnostic tool, allowing for better evaluation of the serratus anterior muscle and guiding interventions. Su et al. (2024) provide a technical note on ultrasound evaluation and guided injection techniques for the subscapularis and serratus anterior muscles, which can enhance diagnostic accuracy and treatment efficacy [11]. Their approach is particularly advantageous for assessing and guiding interventions to the pathologies of subscapularis and serratus anterior muscles, which are located anterior to the scapula and are difficult to access with traditional techniques [11]. Ultrasound imaging allows for visualization of muscle integrity, identification of trigger points, and assessment for nerve entrapments.

3.3. Treatment Approaches

Current treatment options include conservative approaches, including physical therapy, which focuses on enhancing muscle function and alleviating pain through targeted exercises and manual techniques. Pharmacological interventions, such as analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), are commonly utilized to manage symptoms. Injections directed at myofascial trigger points within the serratus anterior muscle have been reported [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19], presenting a potential therapeutic strategy for the alleviation of localized muscular pain, including injection of steroids and local anesthetics (LA) into the trigger points of SAM by Bautista 2017 [1], which carries the potential for systemic and local side effects from both the steroids and the LA. In contrast, ultrasound-guided hydrodissection of peripheral or deep nerves using 5% dextrose in water (D5W), without the addition of local anesthetics, has emerged as a promising alternative treatment option [20,21]. This approach can effectively address peripheral or central neuropathic pain without the systemic or local side effects associated with steroids and LA , and potentially allow for a more accurate determination of procedural endpoint by avoiding an anesthetic effect on the nerve which may prevent symptoms of incomplete entrapment release.

3.3.1. Conservative Management

3.3.1, Exercise Therapy: Targeted exercises are crucial for restoring serratus anterior function and scapular stability. Neumann and Camargo (2019) discussed kinesiologic strategies for selectively activating the serratus anterior, emphasizing exercises that optimize muscular control and encourage pain-free shoulder motion [23]. Andersen et al. (2014) demonstrated that scapular function training can reduce pain intensity and improve shoulder strength in individuals with chronic neck and shoulder pain [24]. Kilinç et al. (2024) found that incorporating scapulohumeral exercises into rehabilitation improved performance and reduced pain in stroke patients [25].

3.3.2. Manual Therapy

Techniques such as joint mobilization and soft tissue release can address musculoskeletal imbalances. Magarey and Jones (2003) highlighted the importance of early management of altered motor control around the shoulder complex [26]. Haik et al. (2017) found that thoracic spine manipulation may enhance scapular upward rotation, although its effects on muscle activity require further investigation [27]. Petersen et al. (2016) found that cervical manipulation and neck range of motion exercises improved scapulothoracic muscle strength in individuals with neck pain [28]. Existing literature does not confirm the efficacy of manual therapy interventions specifically for SAMPS.

3.3.3. Biofeedback

Biofeedback techniques can enhance muscle activation and motor control. Riek et al. (2022) found that various biofeedback methods improved scapular muscle activation ratios during exercises[29]. McKenna et al. (2021) demonstrated that real-time ultrasound feedback significantly increased serratus anterior activation in patients with shoulder pain [30,31] . Valera-Calero et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review indicating that visual real-time ultrasound feedback is more effective than tactile or verbal cues for improving muscle activation performance [32]. The literature supports the use of biofeedback for enhancing muscle activation and motor control. However, its efficacy in the treatment of SAMPS has not been confirmed.

3.4. Injections

Ultrasound-guided trigger point injections with local anesthetics and steroids have shown significant pain reduction in SAMPS patients, as reported by Bautista et al [1], and Vargas-Schaffer et al. (2015) [17]. Wang et al. (2024) compared nerve block strategies in breast cancer patients, finding that a combination of serratus anterior plane block and other techniques improved postoperative recovery and reduced pain [33]. Kim et al. (2022) reported on ultrasound-guided hydrodissection of the LTN using bupivacaine with triamcinolone [34]. Currently, there is no literature documenting the use of D5W without local anesthetic as an injectate for hydrodissecting the LTN.

3.5. Surgical Interventions

Surgical options are typically reserved for severe cases of serratus anterior dysfunction or long thoracic nerve injury that do not respond to conservative management.

3.5.1. Nerve Release

Surgical release of the long thoracic nerve can restore function in cases of nerve compression. Laulan et al. (2011) described a small case series of surgical release with favorable outcomes, particularly when performed within six months of paralysis and all cases of marked dysfunction [35].

3.5.2. Muscle Transfers

Pectoralis major or other muscles transfer has been reported as a management of scapula winging secondary to serratus anterior injury or paralysis [36,37]. Muscle transfers, such as the modified Marmor-Bechtol pectoralis major transfer, can restore scapular stability. Guettler and Basamania (2006) discuss this technique as a viable option for treating scapular winging due to long thoracic nerve injury[36]. While various treatment modalities exist that could be proposed for treatment of serratus anterior muscle dysfunctions, there is no specific documentation, to date, discussing surgical interventions for SAMPS.

3.6. Other Considerations

It is crucial to differentiate SAMPS from other conditions causing shoulder pain.

3.6.1. Scapular Dyskinesis

Addressing scapular dyskinesis is essential in managing serratus anterior related shoulder pain and impingement syndrome[38]. Panagiotopoulos et al (2019) found that patients with shoulder impingement syndrome often exhibit decreased serratus anterior muscle activity [39]. Kinsella and Pizzari (2017) noted that serratus anterior activation patterns can be altered in patients with shoulder pain [40]. For that reason, a potential connection between impingement or other shoulder pain sources should be ruled out by examination.

3.6.2. Winged Scapula

Winging of the scapula is a common manifestation of SAMPS. Duralde (1995) emphasizes a systematic approach to evaluation of scaupular winging [41], while Wagner et al. (2024) highlight the importance of understanding the periscapular muscles involved in scapulohumeral rhythm [42]. Nadeau et al. (2021) provide an overview of its pathophysiology and management [43]. Geurkink et al. (2023) found that many nonsurgically managed patients with scapular winging experience persistent complaints [44], indicating the need for comprehensive patient education regarding potential outcomes. Nevertheless, the direct association of the winged scapula and SAMPS is not established.

In summary, SAMPS is a potentially underdiagnosed condition that can significantly impact quality of life. Effective management necessitates a holistic approach, integrating conservative therapies aimed at restoring muscle function and alleviating pain with surgical options reserved for refractory cases. Given the current limitations in diagnostic precision and the need for more targeted interventions, continued research efforts are crucial to deepen our understanding of SAMPS and develop evidence-based treatment guidelines.

4. Discussion

SAMPS, characterized by pain and dysfunction in the serratus anterior muscle, poses a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, often stemming from LTN involvement. The LTN's critical role in serratus anterior muscle innervation underscores its importance in scapular stability and shoulder function; its dysfunction leads to muscle weakness, pain, and restricted shoulder movement [17]. As highlighted in this case, and reinforced by Bagcier and Yurdakul (2021), a key diagnostic hurdle is the potential for SAMPS symptoms to mimic other conditions, such as myocardial infarction (MI) or other cardiac-related chest pain [10], necessitating careful differential diagnosis, especially in patients with cardiac risk factors.

Given the limitations of current diagnostic methods for SAMPS, SDP provides a valuable adjunct. As demonstrated in Video 1, SDP enables real-time visualization and palpation of the serratus anterior fascia (SAF) and LTN, facilitating the reproduction of the patient's concordant pain and differentiation from other sources of chest and shoulder pain.

This case report presents a novel approach: ultrasound-guided hydrodissection of the LTN using 5% dextrose in water (D5W) without local anesthetic. While Kim et al. (2022) reported on LTN hydrodissection using bupivacaine with triamcinolone [34], the use of D5W alone is, to our knowledge, undocumented. The "fascial unzipping" technique, visualized in Video 2, facilitates precise separation of the LTN from surrounding tissues, potentially alleviating nerve entrapment and reducing pain. The patient's immediate and sustained pain relief in the absence of a potential-obscuring anestthetic effect of the injectate, suggests that D5W hydrodissection may be more a more optimal approach than traditional injection therapies involving local anesthetics and steroids, which carry the risk of systemic and local side effects [20,21,22,45,46].

The successful outcome in this case reinforces the importance of a comprehensive and multifaceted approach to managing SAMPS. While conservative approaches are first line treatments, interventional procedures may be necessary in cases refractory to conservative management, as seen in this patient who had failed conventional treatments for three years. The use of ultrasound guidance, as emphasized by Su et al. (2024), allows for precise delivery of the solution, minimizing the risk of complications and ensuring optimal targeting of the affected nerve [11].

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. The primary limitation is the single-case study design, which inherently limits the generalizability of the findings. A larger sample size in future studies is essential to provide more robust data supporting the efficacy of this treatment. While the patient reported pain relief lasting for 12 months, longer follow-up durations are needed to assess the long-term effectiveness of ultrasound-guided hydrodissection. The absence of a control group also limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions about the intervention's effectiveness compared to standard care or placebo.

Pain relief was primarily measured using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), a subjective assessment influenced by factors such as patient mood and expectations. Although SDP was used as an objective post-treatment assessment, a direct correlation between NRS scores and SDP findings was not established. Future research could benefit from exploring this relationship and incorporating additional objective measures, such as functional assessments or imaging studies, to further validate treatment efficacy.

Potential biases must also be considered. Selection bias may be present, as the patient was referred after failing conservative treatments, suggesting a specific subset of individuals more resistant to standard therapies. Observer bias may exist, as the clinician performing the assessments and treatment could have expectations regarding the outcomes. The potential for publication bias, with positive outcomes being more likely to be published, and reporting bias, where the patient's self-reported outcomes may be influenced by their expectations of treatment efficacy, should also be acknowledged.

Future research should focus on multicenter trials with larger sample sizes and control groups receiving standard treatments. Employing a combination of subjective and objective measures for assessing pain and functionality would provide a more comprehensive understanding of treatment effects. Furthermore, exploring the impact of confounding factors, such as the patient's overall health and psychological state, on treatment outcomes would contribute to a more nuanced interpretation of the findings. Further studies are needed to validate these findings and to optimize treatment protocols.

5. Conclusions

This case report demonstrates the potential of ultrasound-guided hydrodissection with D5W without local anesthetic as a safe and effective treatment for SAMPS, particularly in cases refractory to conservative management. The diagnosis of SAMPS can be challenging due to its symptomatic overlap with conditions such as myocardial infarction and rotator cuff injuries, as evidenced by the patient's initial presentation.

The integration of SDP as a diagnostic adjunct proved valuable in visualizing and assessing the serratus anterior fascia (SAF) and LTN, aiding in the identification of fascial defects and enhancing the overall diagnostic process. SDP offered a dynamic assessment that helped differentiate SAMPS from other sources of chest and shoulder pain.

Ultrasound-guided hydrodissection, coupled with SDP, offers a minimally invasive and targeted approach to managing pain associated with potential LTN entrapment, facilitating improved nerve gliding and reducing local inflammation. The use of readily accessible solutions, such as D5W, further enhances its applicability in most hospitals and clinics and avoids the potential side effects of local anesthetics and steroids.

While this case suggests promising results, the findings are limited by the single-case study design. Case series or cohort-controlled studies are warranted to evaluate the long-term efficacy of D5W hydrodissection in the treatment of SAMPS. Further studies are needed to compare the outcomes and effects of various injectates, such as saline, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and stem cells, and to explore the potential benefits of hydrodissection across different anatomical sites. Such research could significantly advance the field of musculoskeletal pain management and provide more robust evidence-based treatment guidelines for SAMPS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N., K.H.S.L., and A.S.; methodology, N.N., K.H.S.L., T.T., T.S., A.S., W.R., D.C.-J.S.,Y.Y., and K.D.R..; resources, N.N., K.H.S.L., T.T., T.S., A.S., and K.D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, N.N., K.H.S.L., T.T., T.S., A.S., W.R., D.C.-J.S.,Y.Y., and K.D.R.; writing—review and editing, N.N., K.H.S.L., T.T., T.S., A.S., W.R., D.C.-J.S.,Y.Y., and K.D.R.; visualization, N.N., K.H.S.L., T.T., T.S., A.S., W.R., D.C.-J.S.,Y.Y., and K.D.R..; supervision, K.H.S.L., A.S., and K.D.R..; funding acquisition, K.H.S.L., T.S... All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the research involves the use of collections of information or data from which all personal identifiers have been removed prior to being received by the researchers.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data related to this study has been included in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to declare that both Nunung Nugroho and King Hei Stanley Lam are the co-first authors for their equal contribution to this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bautista, A., C. Webb, and R. Rosenquist, Serratus Anterior Muscle Pain Syndrome: A Diagnostic Conundrum. Pain Medicine, 2017. 18(8): p. 1600-1602. [CrossRef]

- Waldman, S.D., Atlas of uncommon pain syndromes. 2014, Saunders/Elsevier,: Philadelphia,. [CrossRef]

- Bordoni, B. and T. Myers, A Review of the Theoretical Fascial Models: Biotensegrity, Fascintegrity, and Myofascial Chains. Cureus, 2020. 12(2): p. e7092. [CrossRef]

- Standring, S., A brief history of topographical anatomy. Journal of Anatomy, 2016. 229(1): p. 32-62. [CrossRef]

- Sinnatamby CS. Last’s anatomy: regional and applied, t.e.A.R.C.S.E.A.E.A.P.P.

- Lam, K.H.S., et al., Infraspinatus Fascial Dysfunction as a Cause of Painful Anterior Shoulder Snapping: Its Visualization via Dynamic Ultrasound and Its Resolution via Diagnostic Ultrasound-Guided Injection. Diagnostics (Basel), 2023. 13(15). [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.H.S., et al., Novel Ultrasound-Guided Cervical Intervertebral Disc Injection of Platelet-Rich Plasma for Cervicodiscogenic Pain: A Case Report and Technical Note. Healthcare (Basel), 2022. 10(8). [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.H.S., et al., Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Hydrodissection for Pain Management: Rationale, Methods, Current Literature, and Theoretical Mechanisms. J Pain Res, 2020. 13: p. 1957-1968.

- Elders, L.A., F.G. Van der Meche, and A. Burdorf, Serratus anterior paralysis as an occupational injury in scaffolders: two case reports. Am J Ind Med, 2001. 40(6): p. 710-3.

- Bagcier, F. and O.V. Yurdakul, A myofascial trigger point of the serratus anterior muscle that could mimic a heart attack: a dry needling treatment protocol. Acupunct Med, 2021. 39(5): p. 563-564. [CrossRef]

- Su, D.C., C.Y. Hung, and K.H.S. Lam, Ultrasound Evaluation and Guided Injection of the Subscapularis and Serratus Anterior Muscles Between the Scapula and the Thoracic Cage: A Technical Note. J Ultrasound Med, 2024. 43(7): p. 1353-1357. [CrossRef]

- S., T., Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction the Trigger Point Manual (Vol. 1 and 2). 1992: Williams & Wilkins;

- Simons DG, T.J., Simons LS (1999) Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction – The Trigger Point Manual. Vol 1. Upper Half of Body,. 2nd ed. 1999: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins.

- Kim, M.Y., Y.M. Na, and J.H. Moon, Comparison on Treatment Effects of Dextrose Water, Saline, and Lidocaine for Trigger Point Injection. J Korean Acad Rehab Med, 1997. 21(5): p. 967-973.

- DAVID J. ALVAREZ, D.O., AND PAMELA G. ROCKWELL, D.O., Trigger Points: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician., 2002. 4(65).

- Kumbhare, D., et al., Ultrasound-Guided Interventional Procedures: Myofascial Trigger Points With Structured Literature Review. Reg Anesth Pain Med, 2017. 42(3): p. 407-412.

- Vargas-Schaffer, G., et al., Ultrasound-Guided Trigger Point Injection for Serratus Anterior Muscle Pain Syndrome: Description of Technique and Case Series. A A Case Rep, 2015. 5(6): p. 99-102.

- Lavelle, E.D., W. Lavelle, and H.S. Smith, Myofascial trigger points. Med Clin North Am, 2007. 91(2): p. 229-39.

- Phan, V., et al., Myofascial Pain Syndrome: A Narrative Review Identifying Inconsistencies in Nomenclature. PM R, 2020. 12(9): p. 916-925. [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.K.H., K.D. Reeves, and A.L. Cheng, Transition from Deep Regional Blocks toward Deep Nerve Hydrodissection in the Upper Body and Torso: Method Description and Results from a Retrospective Chart Review of the Analgesic Effect of 5% Dextrose Water as the Primary Hydrodissection Injectate to Enhance Safety. Biomed Res Int, 2017. 2017: p. 7920438. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, K.D., et al., A Novel Somatic Treatment for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: A Case Report of Hydrodissection of the Cervical Plexus Using 5% Dextrose. Cureus, 2022. 14(4): p. e23909. [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.H.S., et al., A Novel Ultrasound-Guided Bilateral Vagal Nerve Hydrodissection With 5% Dextrose Without Local Anesthetic for Recalcitrant Chronic Multisite Pain and Autonomic Dysfunction. Cureus, 2024. 16(7): p. e63609.

- Neumann, D.A. and P.R. Camargo, Kinesiologic considerations for targeting activation of scapulothoracic muscles - part 1: serratus anterior. Braz J Phys Ther, 2019. 23(6): p. 459-466.

- Andersen, C.H., et al., Effect of scapular function training on chronic pain in the neck/shoulder region: a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Rehabil, 2014. 24(2): p. 316-24. [CrossRef]

- Onursal Kilinc, O., et al., Effects of scapulo-humeral training on ultrasonographic and clinical evaluations in stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Top Stroke Rehabil, 2024. 31(5): p. 501-512. [CrossRef]

- Magarey, M.E. and M.A. Jones, Dynamic evaluation and early management of altered motor control around the shoulder complex. Man Ther, 2003. 8(4): p. 195-206. [CrossRef]

- Haik, M.N., F. Alburquerque-Sendin, and P.R. Camargo, Short-Term Effects of Thoracic Spine Manipulation on Shoulder Impingement Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2017. 98(8): p. 1594-1605.

- Petersen, S., et al., Scapulothoracic Muscle Strength Changes Following a Single Session of Manual Therapy and an Exercise Programme in Subjects with Neck Pain. Musculoskeletal Care, 2016. 14(4): p. 195-205.

- Sasso, R.C., et al., Selective nerve root injections can predict surgical outcome for lumbar and cervical radiculopathy: comparison to magnetic resonance imaging. J Spinal Disord Tech, 2005. 18(6): p. 471-8.

- Akgun, K., I. Aktas, and Y. Terzi, Winged scapula caused by a dorsal scapular nerve lesion: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2008. 89(10): p. 2017-20.

- Bedewi, M.A., et al., Estimation of ultrasound reference values for the lower limb peripheral nerves in adults: A cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore), 2018. 97(12): p. e0179.

- Valera-Calero, J.A., et al., Ultrasound Imaging as a Visual Biofeedback Tool in Rehabilitation: An Updated Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021. 18(14).

- Wang, S., et al., The effect of different nerve block strategies on the quality of post-operative recovery in breast cancer patients: A randomized controlled study. Eur J Pain, 2024. 28(1): p. 166-173. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., et al., Serratus anterior plane block with ultrasound-guided hydrodissection for lateral thoracic pain caused by long thoracic nerve neuropathy - A case report. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul), 2022. 17(4): p. 434-438. [CrossRef]

- Laulan, J., et al., Isolated paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle successfully treated by surgical release of the distal portion of the long thoracic nerve. Chir Main, 2011. 30(2): p. 90-6. [CrossRef]

- Guettler JH, B.C., Muscle transfers involving the shoulder. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2006 Spring;15(1):27-37. PMID: 16603110., 2006.

- Elhassan, B., Pectoralis major transfer for the management of scapula winging secondary to serratus anterior injury or paralysis. J Hand Surg Am, 2014. 39(2): p. 353-61. [CrossRef]

- Ben Kibler, W., et al., Managing Scapular Dyskinesis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am, 2023. 34(2): p. 427-451.

- Panagiotopoulos, A.C. and I.M. Crowther, Scapular Dyskinesia, the forgotten culprit of shoulder pain and how to rehabilitate. SICOT J, 2019. 5: p. 29.

- Kinsella, R. and T. Pizzari, Electromyographic activity of the shoulder muscles during rehabilitation exercises in subjects with and without subacromial pain syndrome: a systematic review. Shoulder Elbow, 2017. 9(2): p. 112-126. [CrossRef]

- Duralde, X.A., Evaluation and treatment of the winged scapula. J South Orthop Assoc, 1995. 4(1): p. 38-52.

- Wagner, E.R., et al., The Scapula: The Greater Masquerader of

Shoulder Pathologies. Instr Course Lect, 2024. 73: p. 587-607.

- Nadeau, C., S. McGhee, and J.M. Gonzalez, Winged scapula: an overview of pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Emerg Nurse, 2021. 29(5): p. 28-31.

- Geurkink, T.H., et al., Treatment of neurogenic scapular winging: a systematic review on outcomes after nonsurgical management and tendon transfer surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 2023. 32(2): p. e35-e47.

- Hauser, R.A., et al., A Systematic Review of Dextrose Prolotherapy for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord, 2016. 9: p. 139-59. [CrossRef]

- Buntragulpoontawee M, Chang KV, Vitoonpong T, Pornjaksawan S, Kitisak K, Saokaew S, Kanchanasurakit S. The Effectiveness and Safety of Commonly Used Injectates for Ultrasound-Guided Hydrodissection Treatment of Peripheral Nerve Entrapment Syndromes: A Systematic Review. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Mar 5;11:621150. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).