Submitted:

18 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

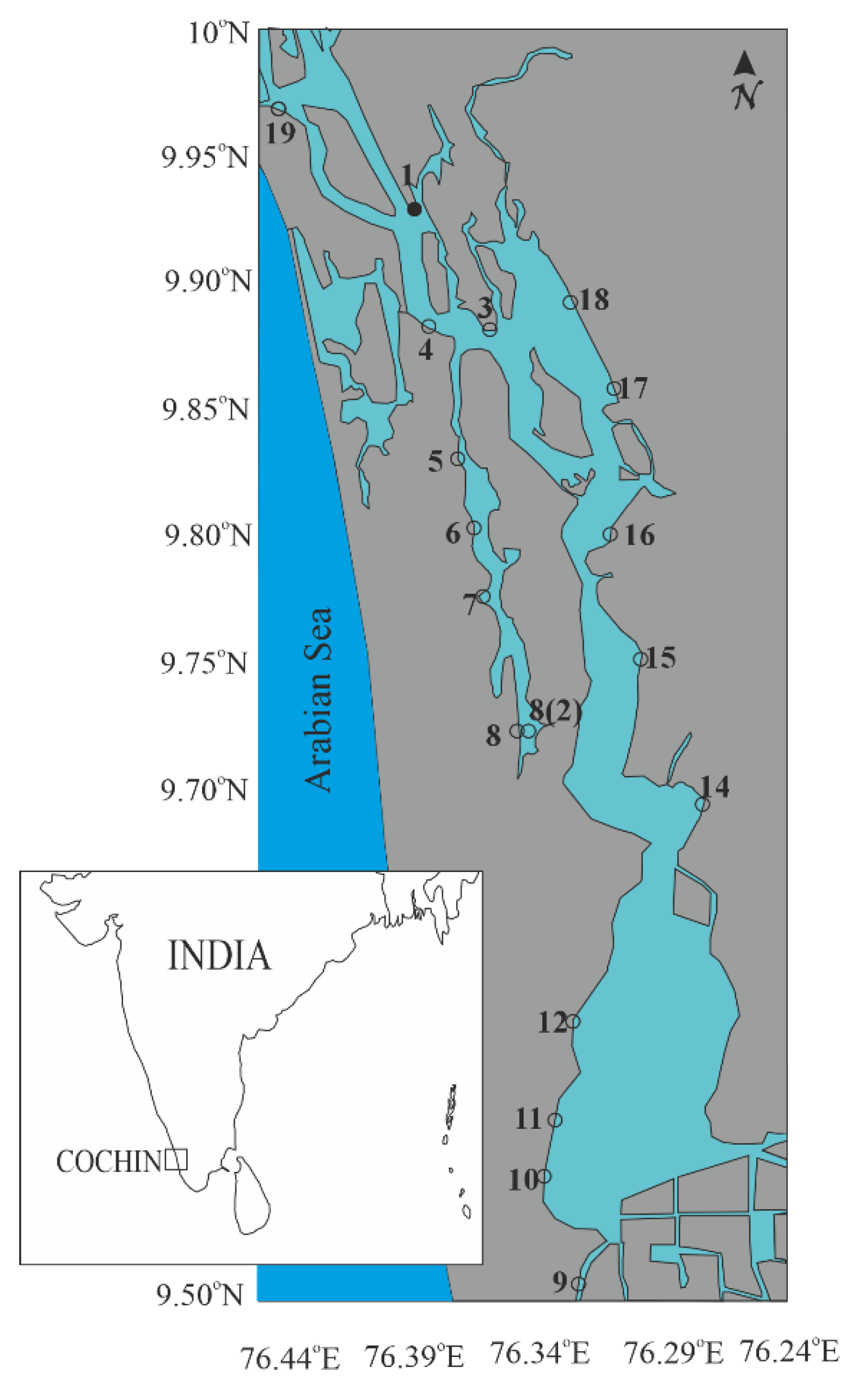

2.1. Study Area

| Date of Sample Collection | Seasons | δ18OVSMOW (‰) | Salinity | ||

| High tide | Low tide | High tide | Low tide | ||

| 4-Oct | North-East Monsoon | -2.84 | 0.2 | ||

| 18-Oct | -1.87 | -1.9 | 8.5 | 5.1 | |

| 2-Nov | -1.19 | -3.49 | 12.6 | 11.1 | |

| 16-Nov | -4.69 | -4.21 | 1.9 | 1.3 | |

| 2-Dec | -2.44 | -3 | 11.5 | 7.1 | |

| 16-Dec | -1.15 | -2.22 | 19.4 | 12.3 | |

| 31-Dec | -1.15 | -1.54 | 20 | 16.2 | |

| 15-Jan | -0.96 | -1.86 | 19.6 | 17.8 | |

| 30-Jan | -1.23 | -0.7 | 21.1 | 18 | |

| 13-Feb | Pre-Monsoon | -0.41 | -0.74 | 21.7 | 17.1 |

| 28-Feb | -0.3 | -1.24 | 20.5 | 18.6 | |

| 15-Mar | -0.58 | -0.78 | 18.5 | 18.1 | |

| 15-Apr | -0.75 | -1.1 | 20.5 | 16.6 | |

| 14-May | -0.72 | -0.47 | 21.6 | 20.3 | |

| 27-May | -1.01 | -1.09 | 7.8 | 4.9 | |

| 14-Jun | South West Monsoon | -3.72 | -3.69 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 27-Jun | -3.2 | -3.29 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 11-Jul | -2.83 | -2.68 | 1 | 2.6 | |

| 26-Jul | -2.66 | -2.58 | 2.5 | 0.5 | |

| 11-Aug | -2.26 | -2.2 | 2.8 | 4 | |

| 26-Aug | -2.74 | -2.58 | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| 8-Sep | -2.01 | -2.42 | 10.2 | 2.9 | |

| 25-Sep | -5.01 | 0.1 | |||

| Sl. No | Location | Lat (oN) | Long (oE) | Salinity (PSU) |

δ18O (‰ VSMOW) |

δ13CDIC (‰ VPDB) |

| 1 | Thevara ferry | 9.93 | 76.30 | 0.10 | 0.42 | -5.60 |

| 2 | Panangad | 9.88 | 76.33 | 18.80 | 0.54 | -5.64 |

| 3 | Arror | 9.88 | 76.31 | 17.60 | 0.89 | -10.52 |

| 4 | Kudapuram (Eramallor) | 9.83 | 76.32 | 15.70 | NA | -9.01 |

| 5 | Kodamthuruthu (Kuthiathodu) | 9.80 | 76.33 | 13.10 | 2.49 | -9.60 |

| 6 | Thykkatusherry | 9.77 | 76.33 | 11.70 | 3.31 | -11.10 |

| 7A | Vyalar | 9.72 | 76.43 | 10.40 | 1.52 | -9.62 |

| 7B | Vyalar | 9.72 | 76.43 | 10.40 | 0.43 | -8.58 |

| 8 | Punnamada | 9.51 | 76.35 | 2.10 | 0.50 | -14.09 |

| 9 | Aaryad | 9.54 | 76.35 | 0.10 | 1.76 | -17.23 |

| 10 | Pallathuserry | 9.56 | 76.36 | 0.10 | 0.53 | -21.34 |

| 11 | Muhamma | 9.60 | 76.36 | 3.40 | 1.23 | -17.03 |

| 12 | Thalayazham (Puthanpalam) | 9.69 | 76.41 | 10.40 | 2.00 | -11.97 |

| 13 | Vaikom | 9.75 | 76.39 | 11.60 | 3.06 | -9.33 |

| 14 | Kulasekaramagalam (Mekara) | 9.80 | 76.38 | 11.90 | 0.78 | -8.04 |

| 15 | Punnakkaveli (South Paravoor) | 9.86 | 76.38 | 12.45 | 2.45 | -7.74 |

| 16 | Chavakakadavuamera (Udayamperoor) | 9.89 | 76.36 | 16.40 | 1.59 | -7.20 |

| 17 | Fort Kochi | 9.97 | 76.24 | 28.00 | -1.75 | -2.90 |

2.2. Sample collection and Analysis

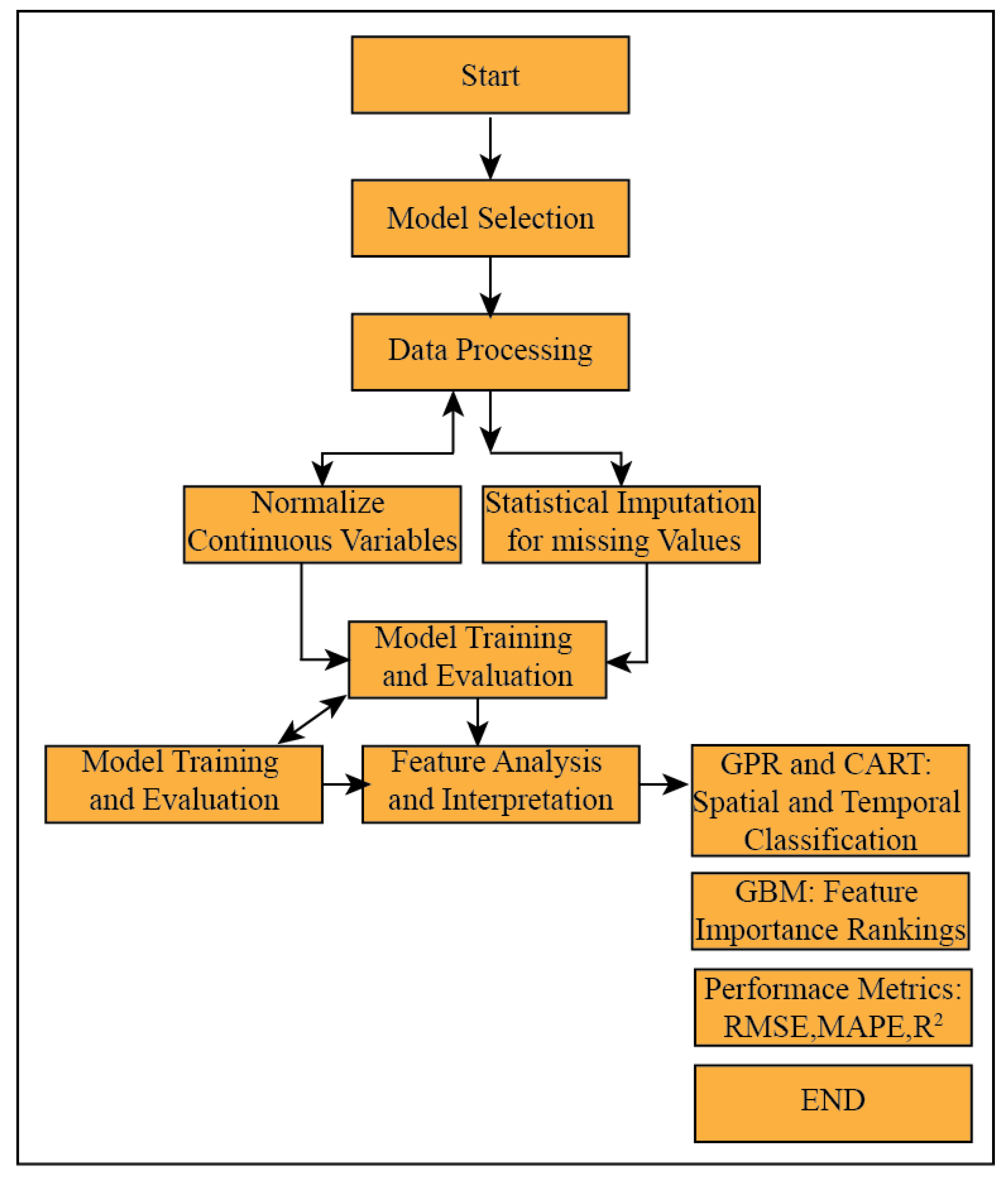

2.3. Machine Learning Methodology

3. Results

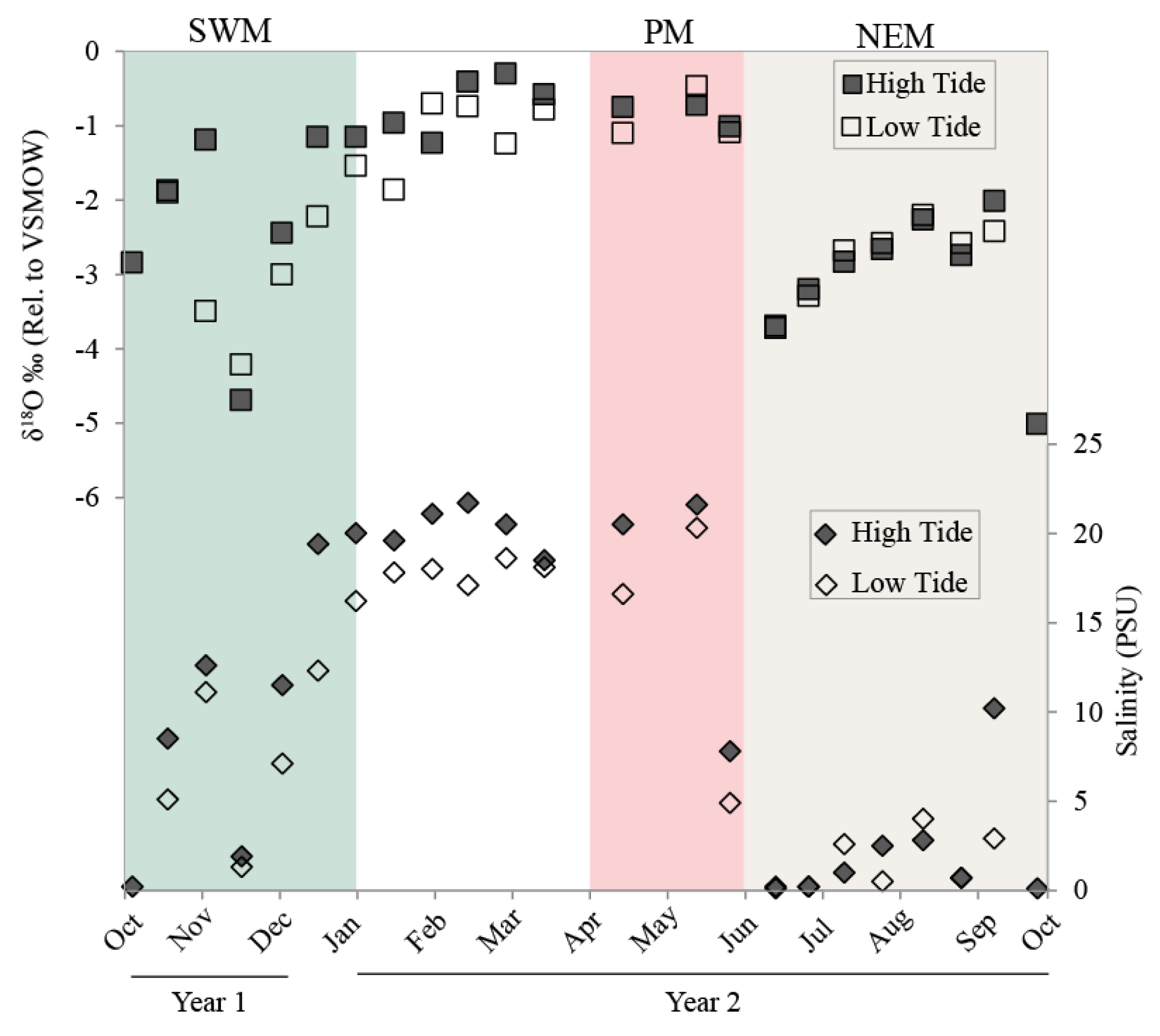

3.1. Seasonal and Spatial Variations in δ¹⁸O and Salinity

3.2. Performance Metrics for Machine Learning Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Seasonal and Spatial Variations in δ¹⁸O and Salinity

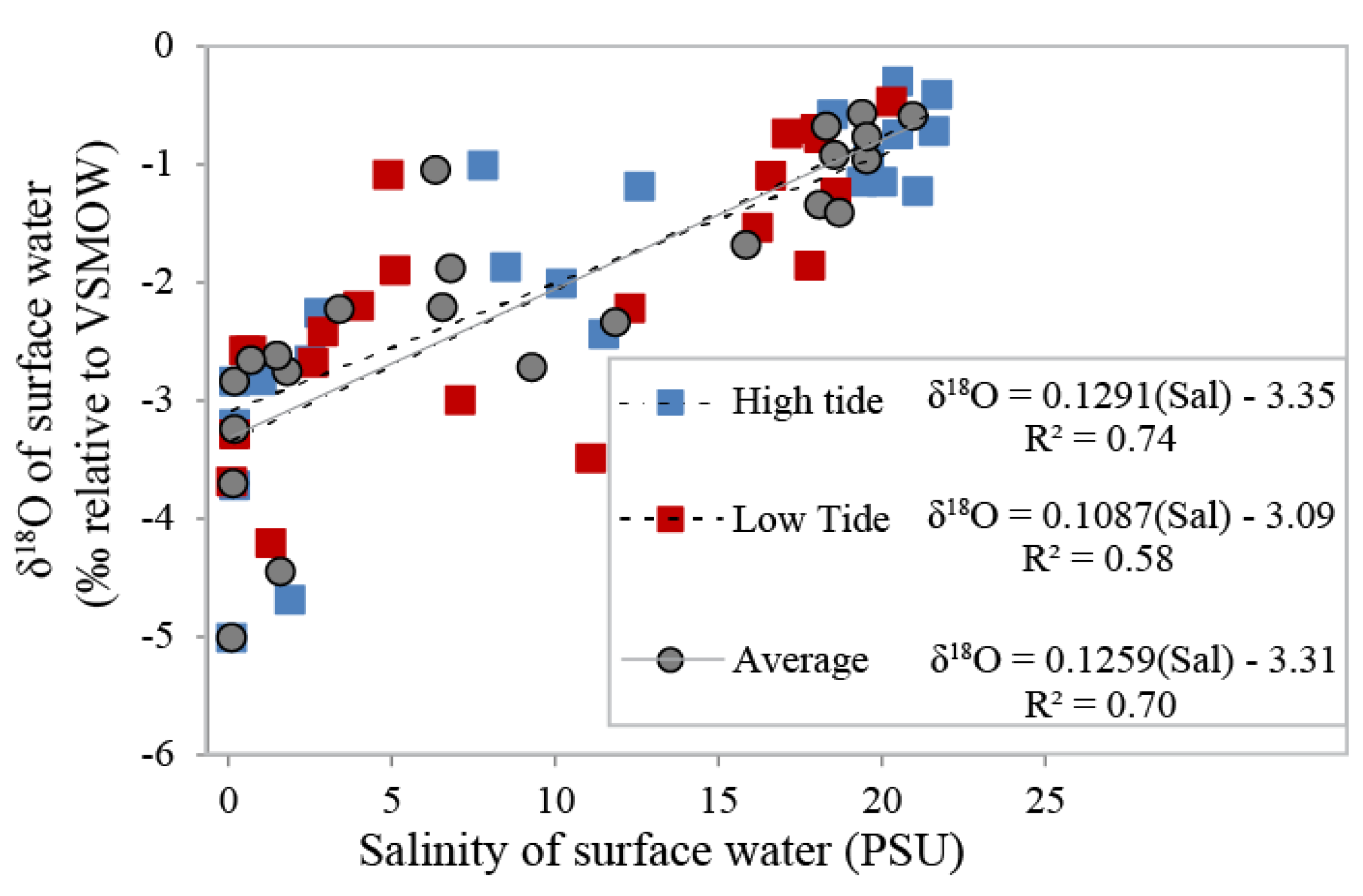

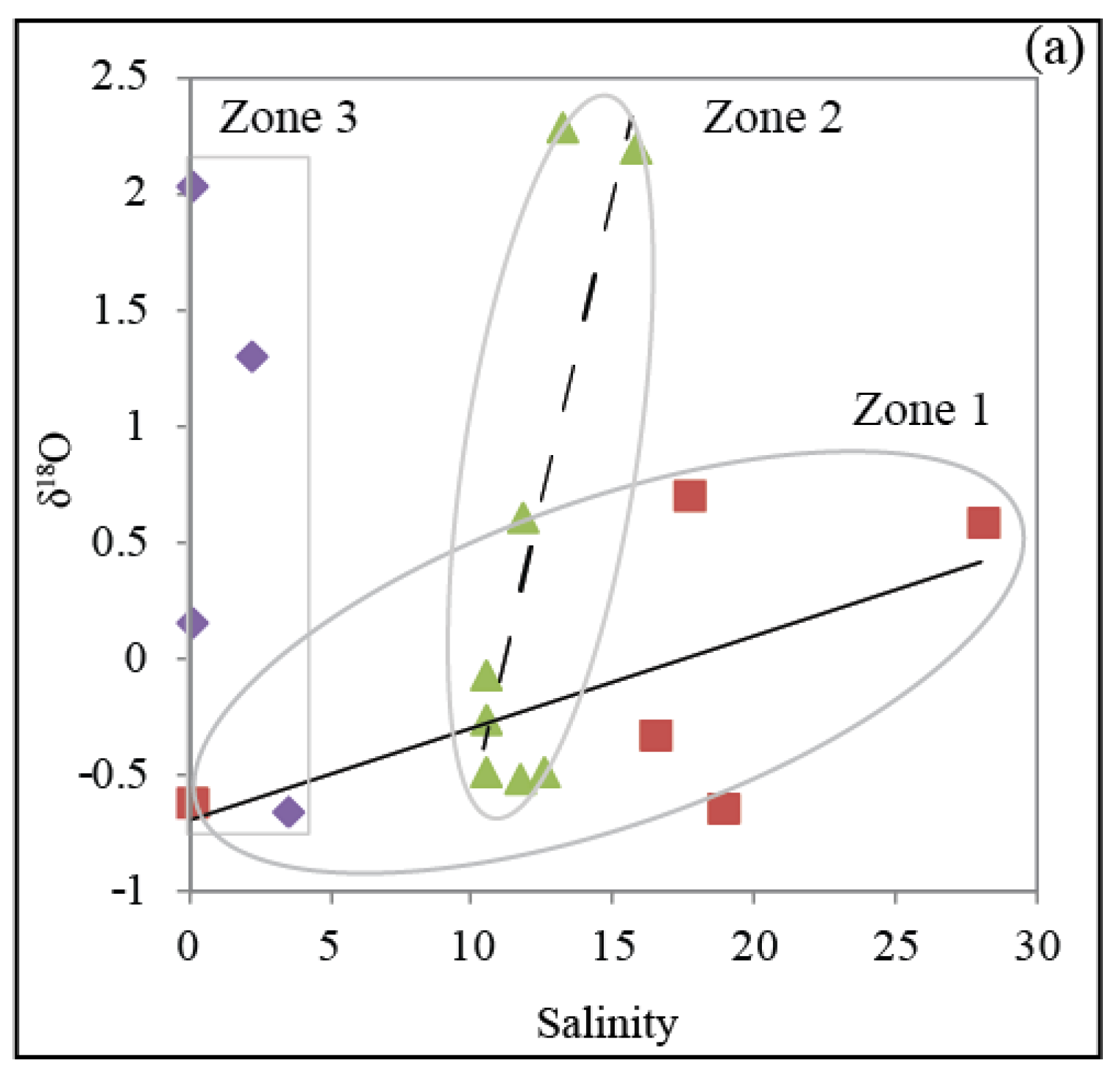

4.2. δ18O Relationship with Salinity

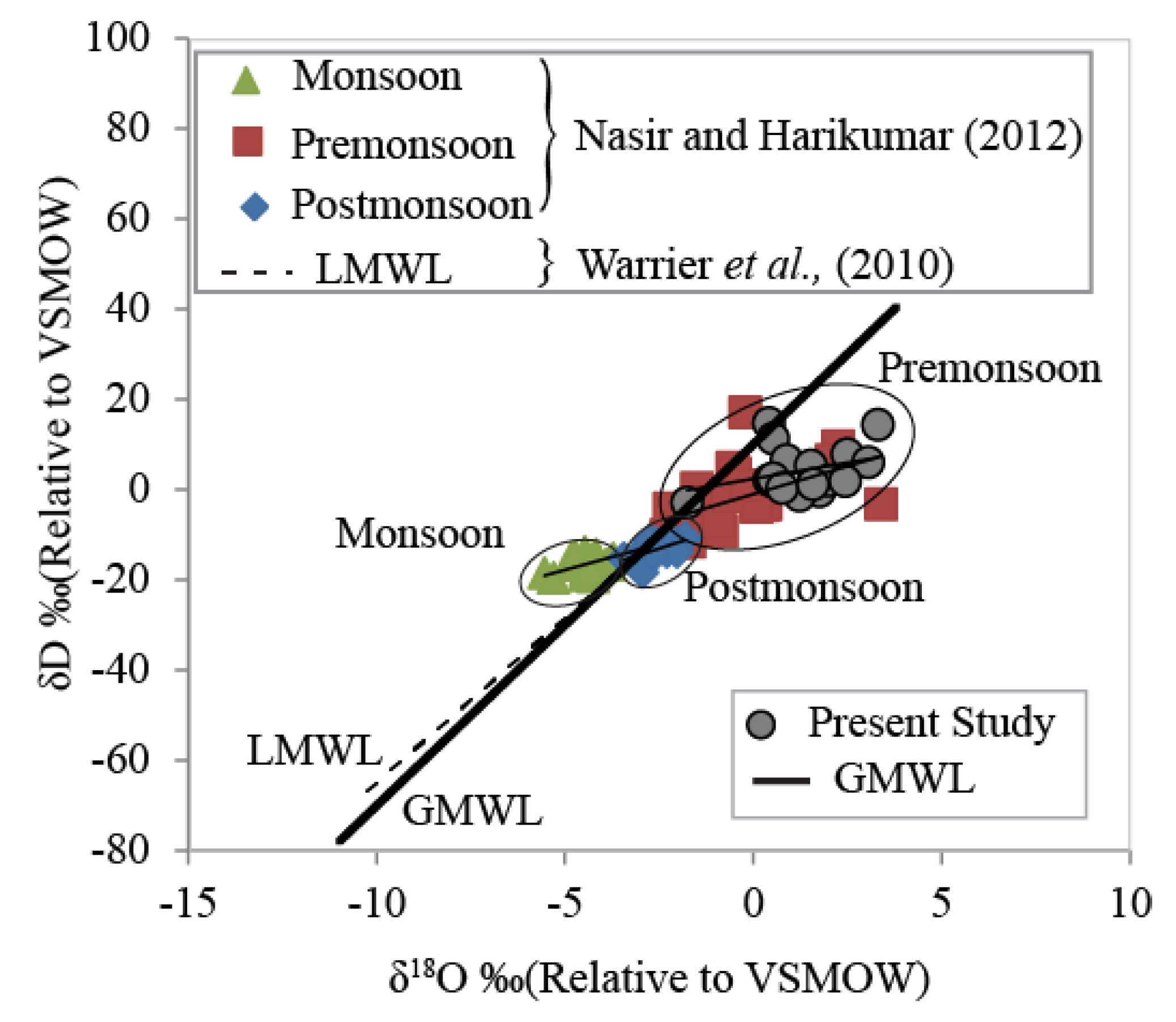

4.3. δ18O-δD Relationship of CBW Estuary

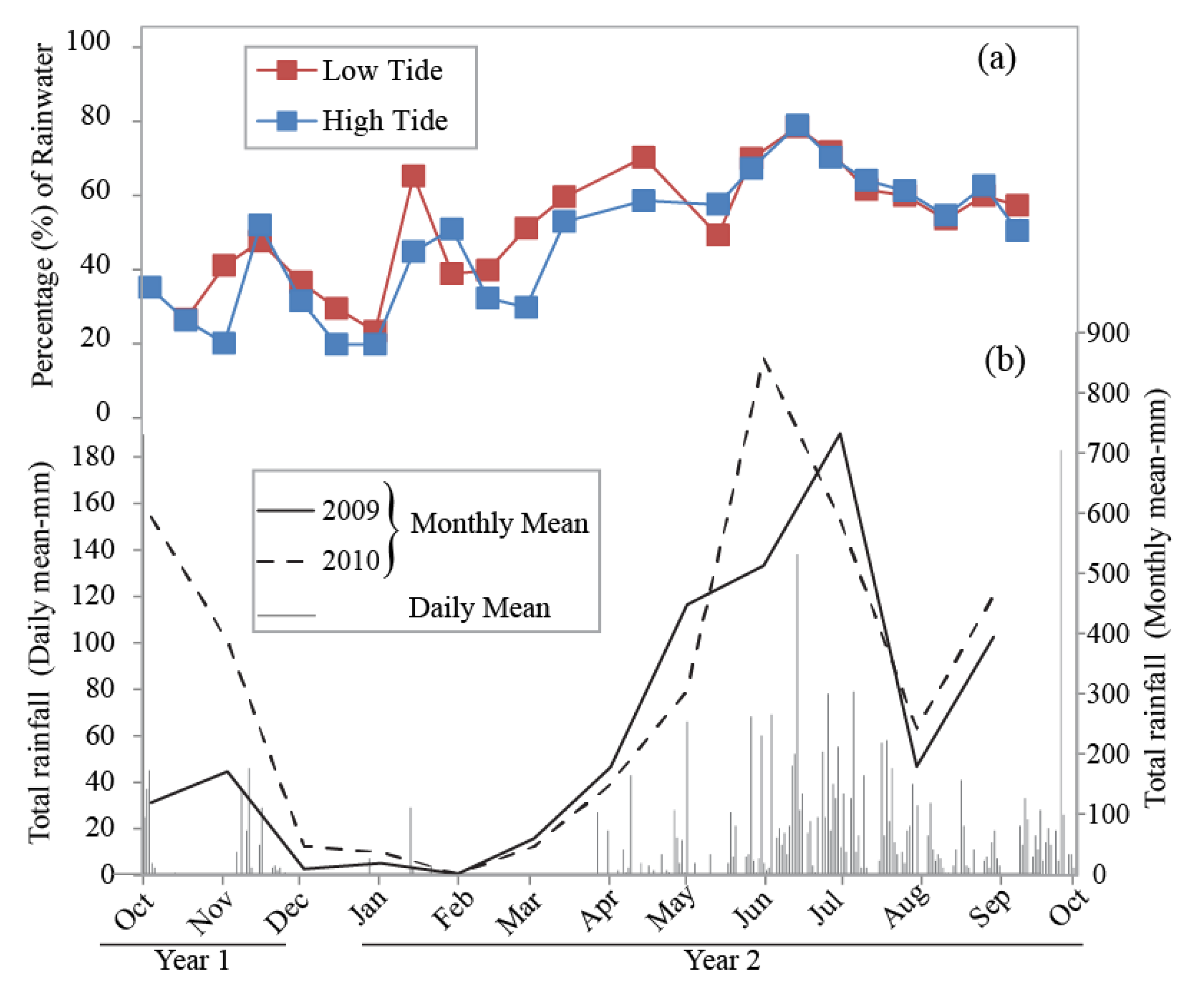

4.4. Freshwater Flux in Comparison with the Seasonal Rainfall

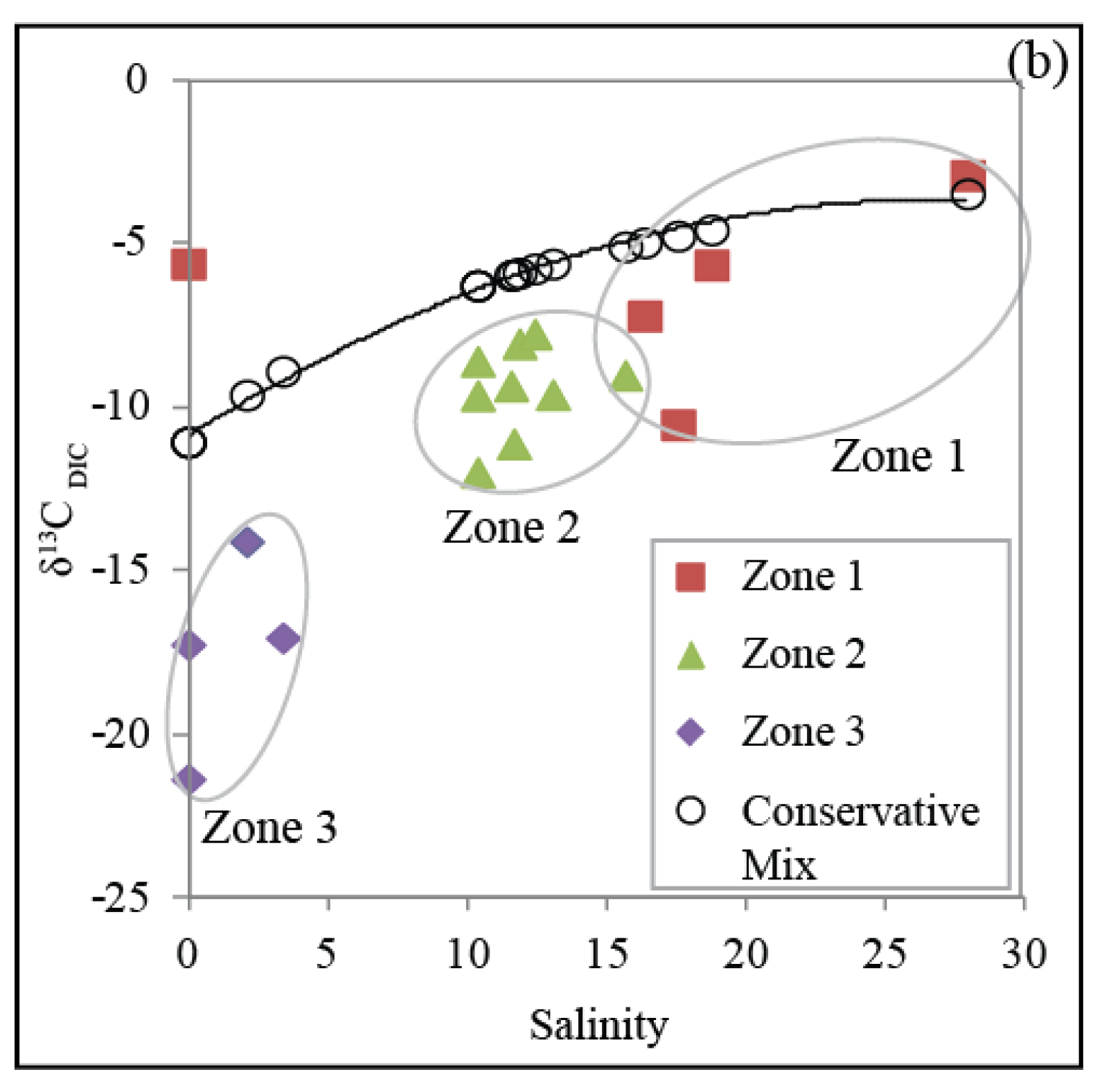

4.5. Carbon Dynamics Using Salinity and δ13CDIC

4.6. Evaluating Machine Learning Models for Salinity and Isotopic Predictions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBW | Cochin Back Water |

| DIC | Dissolved Inorganic Carbon |

| PM | Pre-Monsoon |

| SWM | South West Monsoon |

| NEM | Northeast Monsoon |

| HT | High Tide |

| LT | Low Tide |

| NBS19 | National Bureau of Standards -19 |

| HDPE | High Density Polyethylene |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| ANFIS | Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| RBNN | Radial Function Based Neural Network |

| RF | Random Forest |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbor |

| GBM | Gradient Boosting Machines |

| GPR | Gaussian Process regression |

| CART | Classification and Regression Tree |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machines |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

References

- Day Jr, J.W., Kemp, W.M., Yáñez-Arancibia, A. and Crump, B.C. eds., 2012. Estuarine ecology. John Wiley & Sons.

- Dittmar, T. and Lara, R.J., 2001. Driving forces behind nutrient and organic matter dynamics in a mangrove tidal creek in North Brazil. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 52(2), pp.249-259. [CrossRef]

- Cloern, J.E. and Jassby, A.D., 2010. Patterns and scales of phytoplankton variability in estuarine–coastal ecosystems. Estuaries and coasts, 33, pp.230-241. [CrossRef]

- Vijith V, Sundar D, Shetye SR (2009) Time-dependence of salinity in monsoonal estuaries. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 85:601–608. [CrossRef]

- Qasim S, Gopinathan C (1969) Tidal cycle and the environmental features of Cochin Backwater (a tropical estuary). Proc Indian Acad Sci - Sect A Part 3, Math Sci 69:336–348. [CrossRef]

- Haldar, R., Khosa, R., Gosain, A.K. (2019). Impact of Anthropogenic Interventions on the Vembanad Lake System. In: Rathinasamy, M., Chandramouli, S., Phanindra, K., Mahesh, U. (eds) Water Resources and Environmental Engineering I. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Kulk, G., George, G., Abdulaziz, A., Menon, N., Theenathayalan, V., Jayaram, C., Brewin, R. J., & Sathyendranath, S. (2020). Effect of Reduced Anthropogenic Activities on Water Quality in Lake Vembanad, India. Remote Sensing, 13(9), 1631. [CrossRef]

- Pranav, P., Roy, R., Jayaram, C., D’Costa, P. M., Choudhury, S. B., Menon, N. N., Nagamani, P., Sathyendranath, S., Abdulaziz, A., Sai, M. S., Sajhunneesa, T., & George, G. (2021). Seasonality in carbon chemistry of Cochin backwaters. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 46, 101893. [CrossRef]

- Shivaprasad A, Vinita J, Revichandran C, et al. (2013) Seasonal stratification and property distributions in a tropical estuary (Cochin estuary, west coast, India).

- Ghosh P, Chakrabarti R, Bhattacharya SK (2013) Short- and long-term temporal variations in salinity and the oxygen, carbon and hydrogen isotopic compositions of the Hooghly Estuary water, India. Chem Geol 335:118–127. [CrossRef]

- Nasir UP, Harikumar PS (2012) Hydrochemical and isotopic investigation of a tropical wetland system in the Indian sub-continent. Environ Earth Sci 66:111–119.

- Bhavya PS, Kumar S, Gupta GVM, et al. (2016) Carbon isotopic composition of suspended particulate matter and dissolved inorganic carbon in the Cochin estuary during post-monsoon. Curr Sci 110:.

- Raymond, P.A., Bauer, J.E., Caraco, N.F., Cole, J.J., Longworth, B. and Petsch, S.T., 2004. Controls on the variability of organic matter and dissolved inorganic carbon ages in northeast US rivers. Marine chemistry, 92(1-4), pp.353-366. [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, S., Borges, A.V., Castañeda-Moya, E., Diele, K., Dittmar, T., Duke, N.C., Kristensen, E., Lee, S.Y., Marchand, C., Middelburg, J.J. and Rivera-Monroy, V.H., 2008. Mangrove production and carbon sinks: a revision of global budget estimates. Global biogeochemical cycles, 22(2). [CrossRef]

- Astray, G., Soto, B., Barreiro, E., Gálvez, J. F., & Mejuto, J. C. (2021). Machine learning applied to the oxygen-18 isotopic composition, salinity and temperature/potential temperature in the mediterranean sea. Mathematics. [CrossRef]

- Cemek, B., Arslan, H., Küçüktopcu, E., & Simsek, H. (2022). Comparative analysis of machine learning techniques for estimating groundwater deuterium and oxygen-18 isotopes. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment. [CrossRef]

- Noori, N., Kalin, L., & Isik, S. (2020). Water quality prediction using SWAT-ANN coupled approach. Journal of Hydrology. [CrossRef]

- Ly, Q. V., Nguyen, X. C., Lê, N. C., Truong, T. D., Hoang, T. H. T., Park, T. J., ... & Hur, J. (2021). Application of Machine Learning for eutrophication analysis and algal bloom prediction in an urban river: A 10-year study of the Han River, South Korea. Science of The Total Environment, 797, 149040. [CrossRef]

- Samalavičius, V., Gadeikienė, S., Žaržojus, G., Gadeikis, S., & Lekstutytė, I. (2024). Oxygen-18 prediction using machine learning in the Baltic Artesian Basin groundwater. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, L. G., de Oliveira Roque, F., Valente-Neto, F., Koroiva, R., Buss, D. F., Baptista, D. F., Hepp, L. U., Kuhlmann, M. L., Sundar, S., Covich, A. P., & Pinto, J. O. P. (2021). Large-scale prediction of tropical stream water quality using Rough Sets Theory. Ecological Informatics. [CrossRef]

- Al Sudani, Z. A., & Salem, G. S. A. (2022). Evaporation rate prediction using advanced machine learning models: a comparative study. Advances in Meteorology, 2022(1), 1433835. [CrossRef]

- Dagher, D. H. (2024). Assessment of Using Machine and Deep Learning Applications in Surface Water Quantity and Quality Predictions: A Review. Journal of Water Resources and Geosciences, 3(2), 18-48.

- Singh A, Jani RA, Ramesh R (2010) Spatiotemporal variations of the δ18O-salinity relation in the northern Indian Ocean. Deep Sea Res Part I Oceanogr Res Pap 57:1422–1431. [CrossRef]

- Deshpande RD, Muraleedharan PM, Singh RL, et al. (2013) Spatio-temporal distributions of δ18O, δD and salinity in the Arabian Sea: Identifying processes and controls. Mar Chem 157:144–161.

- Lekshmy, P.R., Midhun, M., Ramesh, R. and Jani, R.A., 2014. 18O depletion in monsoon rain relates to large scale organized convection rather than the amount of rainfall. Scientific reports, 4, p.5661. [CrossRef]

- Rasheed K, Joseph KA, Balchand AN (1995) Impacts of harbour dredging on the coastal shoreline features around Cochin. In: Proceedings of the international conference on ‘Coastal Change. pp 943–948.

- Epstein S, Mayeda T (1953) Variation of O18 content of waters from natural sources. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 4:213–224. [CrossRef]

- Rangarajan R, Ghosh P (2011) Role of water contamination within the GC column of a GasBench II peripheral on the re-producibility of 18O/16O ratios in water samples. Isotopes Environ Health Stud 47:498–511. [CrossRef]

- Assayag N, Rivé K, Ader M, et al. (2006) Improved method for isotopic and quantitative analysis of dissolved inorganic carbon in natural water samples. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 20:2243–2251. [CrossRef]

- Rangarajan, R., Pathak, P., Banerjee, S. and Ghosh, P. (2021). Floating boat method for carbonate stable isotopic ratio determination in a GasBench II peripheral. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 35(15), p.e9115. [CrossRef]

- Torgersen T (1979) Isotopic composition of river runoff on the US East Coast: Evaluation of stable isotope versus salinity plots for coastal water mass identification. J Geophys Res Ocean 84:3773–3775. [CrossRef]

- Fairbanks RG, Sverdlove M, Free R, et al. (1982) Vertical distribution and isotopic fractionation of living planktonic forami-nifera from the Panama Basin. Nature 298:841.

- Khim B-K, Park B-K, Yoon H Il (1997) Oxygen isotopic compositions of seawater in the Maxwell Bay of King George Island, west Antarctica. Geosci J 1:115.

- Hameed AS, Resmi TR, Suraj S, et al. (2015) Isotopic characterization and mass balance reveals groundwater recharge pattern in Chaliyar river basin, Kerala, India. J Hydrol Reg Stud 4:48–58. [CrossRef]

- Rahul, P. and Ghosh, P., 2019. Long term observations on stable isotope ratios in rainwater samples from twin stations over Southern India; identifying the role of amount effect, moisture source and rainout during the dual monsoons. Climate Dynamics, 52(11). [CrossRef]

- Warrier, C.U., Babu, M.P., Manjula, P., Velayudhan, K.T., Hameed, A.S. and Vasu, K., 2010. Isotopic characterization of dual monsoon precipitation–evidence from Kerala, India. Current Science, pp.1487-1495.

- Samanta S, Dalai TK, Tiwari SK, Rai SK (2018) Quantification of source contributions to the water budgets of the Ganga (Hooghly) River estuary, India. Mar Chem 207:42–54. [CrossRef]

- Bhavya PS, Kumar S, Gupta GVM, et al. (2018) Spatio-temporal variation in δ13CDIC of a tropical eutrophic estuary (Cochin estuary, India) and adjacent Arabian Sea. Cont Shelf Res 153:75–85. [CrossRef]

- Kaushal R, Ghosh P, Geilmann H (2016) Fingerprinting environmental conditions and related stress using stable isotopic composition of rice (Oryza sativa L.) grain organic matter. Ecol Indic 61:941–951. [CrossRef]

| Model | Target | RMSE | R² | MAPE (%) | T-Test (p-value) |

| GBM | Salinity | 0.0993 | 0.9563 | N/A | <0.001 |

| GPR | δ¹⁸O | 0.6298 | -5.7860 | N/A | 0.045 |

| CART | δ¹³C | 0.3449 | -2.0460 | N/A | 0.089 |

| ELM | δ¹⁸O | 0.9187 | -13.440 | N/A | 0.103 |

| ELM | δ¹³C | 0.7626 | -13.890 | N/A | 0.097 |

| RBNN | δ¹⁸O | 0.2869 | -0.4080 | N/A | <0.001 |

| RBNN | δ¹³C | 0.2626 | -0.7660 | N/A | <0.001 |

| RF | δ¹⁸O | 0.2101 | 0.2451 | 36.19 | <0.001 |

| RF | δ¹³C | 0.2489 | -0.5869 | 34.90 | 0.032 |

| SVM | δ¹⁸O | 0.2500 | -0.0695 | 39.16 | 0.071 |

| SVM | δ¹³C | 0.2556 | -0.6722 | 25.88 | 0.089 |

| KNN | δ¹⁸O | 0.1703 | 0.5039 | 29.87 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).