Introduction

Zoos and aquariums have evolved from menageries, with animals in cages, to zoological parks focused on science (Maynard et al. 2020). Zoos have an ethical obligation to ensure the animals in their care experience the highest possible standard of welfare (Wolfensohn et al. 2018). Ensuring animal welfare is not only an ethical and legal obligation, but also a key requirement for accreditation from professional organisations, e.g., regional member associations such as the Zoo and Aquarium Association (ZAA). While conservation goals are frequently central to a zoo’s mission, these and other objectives (e.g., education, advocacy) cannot come at the expense of welfare; ensuring positive welfare must be fundamental to the zoo’s operation. Therefore, it is essential that zoos have a mechanism to enhance and ensure positive welfare—the absence of negative welfare being a given—whilst continuing to evolve and adapt, aligning with changing public sentiment and new knowledge (Gray, 2017). To ensure long-term success of zoos, having animal welfare central to the zoo’s business supports continuous improvement. Developing and implementing an animal welfare strategy is essential to fulfilling this objective.

In this work, we define an animal welfare strategy as a comprehensive framework that sits above operational documents and plans, to ensure its welfare considerations are integrated into all zoo operations, policies, and procedures, aiming to embed effective welfare practices across the entire organisation and extend and showcase these practices into the broader community. This article is intended to provide detail about the role and composition of an animal welfare strategy. In addition, it is intended to help support readers with the creation and implementation of their own institutional animal welfare strategy. It first provides the context in which a welfare strategy is created, by defining animal welfare and examining the societal and ethical considerations around the existence of zoos, and detailing the importance of good animal welfare for a zoo’s existence. It then provides a framework for developing and operationalising an animal welfare strategy to embed animal welfare into zoo policy and practice.

Defining Animal Welfare

There have been various attempts to define animal welfare, but the central component that is important to acknowledge is that animal welfare is an internal state derived from the experiences of the animal as it interacts with the external environment. Animal welfare can vary on a scale from negative to positive and incorporates both physical health and emotional health (Fraser 2008; Broom 2014; Yeates 2017). Many authors including Fraser (2008) have argued the relative importance of three conceptual frameworks to ‘define’ animal welfare: (1) biological functioning, (2) naturalness, and (3) affective state. The term ‘affective state’ is often used as a broad category encompassing both the emotions and moods (Reimert et al. 2023) experienced by an animal, often characterised as ‘pleasant’ or ‘unpleasant’ (Mellor and Beausoleil 2015).

Recent animal welfare research supports the central role of the affective state definition, which is centred on animal ‘feelings’, rather than solely focusing on biological functioning or naturalness (Duncan 2004; Whittaker & Barker 2020). Researchers in this camp argue that if an animal’s psychological needs are met, physical health and natural behaviour are likely to follow, making these other criteria less important to the definition of animal welfare (Englund and Cronin 2023). We agree with this conclusion and contend that, while all three components are relevant, an animal’s psychological state is the most important factor to consider when assessing its welfare for this will impact upon, and be impacted by, biological functioning and naturalness. At its core then, animal welfare is about the individual’s internal state—their perception of their quality of life (Ohl and Putman, 2018). One way of framing this approach to animal welfare is to summate the balance of positive and negative experiences throughout the animal’s life (Vigors et al. 2021). Defining welfare is important, as it shapes how zoos prioritise resources, communicate about animal welfare, and set organisational goals, supporting stakeholder ‘buy in’ and the strategic deployment of a welfare strategy.

Animal welfare science is a rapidly growing, young discipline (Hampton et al. 2023). The book ‘Animal Machines’, released in 1964 by Ruth Harrison, caused an outcry of public concern over the conditions in which farm animals were kept, leading to the creation of the Brambell Report in 1965 (McCulloch 2013), and the later development of animal welfare science as an academic discipline. The Five Freedoms, born from the Brambell Report, was a welfare assessment framework that referred to freedom from thirst, hunger, fear, distress, discomfort, pain, malnutrition, injury, disease, and freedom to express natural behaviour (Mellor, 2016). Despite the Five Freedoms having a huge impact on animal welfare legislation, and farm animal welfare accreditation schemes (McCulloch 2013), they lacked the ability to evaluate the emotional states of animals.

Once a definition of welfare is settled upon, there still needs to be some way of assessing it at a practical level. There have been various attempts to develop tools to assess welfare and the Five Domains model is commonly used in zoological parks as a supportive model. This approach includes consideration of the four physical domains: nutrition, environment, health, and behaviour, including behavioural interactions with conspecifics, humans, and the environment (Mellor et al. 2020). The fifth domain is the animal’s mental or affective state, evaluated by equating it with the collective influence of the four physical domains (Jones et al. 2022). The model considers both negative and positive contributions to the animal’s welfare state (Mellor et al. 2020). Evidence can help infer the animals affective state, assisting in drawing welfare conclusions. It is important to understand animal welfare science, as it influences how organisations assess animal welfare and their animal welfare goals, supporting their animal welfare strategy.

The Social Licence to Operate

Welfare is not only a question of wellbeing for the individual animal, but rather a matter for their caretakers, the institution and its core mission, and the broader community, including the potential implications for institutional sustainability. An understanding of the complexities of welfare, leading to accurate welfare assessments and ability to intervene in the face of poor welfare, is crucial for maintaining the public trust. Welfare is of increasing and significant societal concern, with citizens choosing to support or withdraw from animal-related organisations—such as zoological parks, marine parks, or public aquariums (collectively referred to as ‘zoos’)—based on their views of how animals are treated and/or the justification(s) for captivity. This tacit approval, or societal compact, often referred to as the “social licence to operate” (SLO), represents an ongoing informal approval granted by the community and other stakeholders, reflecting society’s attitudes toward an organisation’s practices (Hampton et al. 2020). Failure to meet the responsibilities tied to social licence can result in social discontent, increased chances of protest and/or litigation, and stricter regulations, all which can hinder the success of animal industries (Coleman, 2018) and the delivery of their core missions.

Zoos with a strong commitment to welfare and conservation can play a key role in shaping people’s perspectives and meaningfully amplify society’s care for the natural world (Greenwell et al. 2023). In the past, zoos’ objectives have included research, recreation, education, and conservation (Kleiman 1985). However, it has been suggested that the modern zoo should include a fifth objective: animal wellbeing (Rose & Riley 2022). For zoos to maintain their SLO, and to continue to fulfil these important roles, their efforts must align with global conservation priorities (Conway, 2011; Miranda et al. 2024), incorporate advances in pedagogy and human influence, and, crucially, adopt advances in animal welfare science, a rapidly-changing field of research. One role of the animal welfare strategy is to promote social justice by advocating for the ethical treatment of animals, aligning with public expectations, and highlighting the zoos commitment to animal welfare.

Ethical Considerations for Zoos

Whilst there are many great outcomes from zoos, they also face many dilemmas and challenges. Firstly, not all zoos can be classified as conservation focused, as some may not align with global conservation goals or may not meet the acceptable standards of animal welfare, diminishing the effectiveness of their conservation efforts (Spooner et al. 2023). But there are good zoos too. As Gray (2017) aptly puts it, ‘Good zoos aren’t menageries anymore, they’re conservation centres’ (p.iii). Ensuring that conservation programs are effective and yet maintain positive animal welfare is only one of the many challenges zoos face. Another challenge is appropriate species choice for public display. Species plans vary between zoos based on their mission and business priorities. For example, a zoo may focus on conservation and visitor experience, while facing challenges associated with animal welfare, sustainability, and financial capacity to house species (Harley 2023). Additionally, charismatic mammal species are often of interest to visitors (Brereton and Brereton 2020), while some, such as carnivores, cetaceans, primates, and elephants, are often viewed as emblematic of compromised welfare (Veasey, 2020), due to their tendency to express stereotypic behaviours, often perceived as a welfare problem (Clubb & Mason 2007). Another challenge for modern zoos is population management, as the need to study or protect a species through research and management actions can sometimes conflict with animal welfare considerations (Minteer and Collins 2013). These conflicts often result in complex ethical dilemmas, sometimes referred to as ‘wicked’ problems. An animal welfare strategy supports organisational commitments to addressing these dilemmas, ensuring they are soundly managed through science, ethically robust, and support an effective decision-making framework.

Why do Zoos Need an Animal Welfare Strategy?

Zoos have a mandatory responsibility to maintain high standards of welfare, while also ensuring legal compliance and adherence to regulations, or accreditation schemes, many of which are predominantly welfare focussed. A well-defined animal welfare strategy is essential to meet these expectations and to ensure the zoo’s ongoing SLO. A key component of a successful animal welfare strategy is the intentional alignment of the organisation’s goals with positive welfare outcomes. This alignment should be established as a clear operational position accepted by all parties.

Zoos also need to fulfil mission-based goals (e.g., conservation outcomes, educational engagement), both within the facility and in society at large. These goals frequently enhance the experience of zoo visitors. However, visitor engagement and the SLO plummet if these activities result in compromised welfare. In general, positive visitor engagement serves as an indication of an organisation’s commitment to, and delivery of, positive welfare, underpinning the broader mission of the zoo. As has been observed, optimal welfare contributes directly to successful conservation efforts (Escobar-Ibarra et al. 2021).

Tensions frequently arise when ethical considerations and business objectives clash, especially within the context of the resource constraints (e.g., financial, physical) common to many zoos. In these cases, zoos frequently adopt cost-effective solutions to make up for resource shortfalls. For example, volunteers may be used (in place of paid, full-time staff) for educational experiences involving animals, without having the full suite of requisite animal-handling skills (Martin, et al. 2024). Similarly, an animal may require more of a limited resource (e.g., a larger habitat to meet their spatial needs), but the resource cannot be provided as it is financially or physically prohibitive. In these cases, as Maple & Perdue (2013, p.167) note, “the business strategy has become [the de facto] welfare strategy”.

This approach is ill conceived. An animal welfare strategy should protect the animals from a flawed business plan and provide clear direction to inform decisions. Animal welfare should not be compromised by activities intended to meet resource shortfalls (e.g., an excessive application of paid animal-visitor interactions), or where physical resources supplied to the animals are restricted to ‘meet budget’ (e.g., replacement of nutritionally appropriate food with lesser alternatives). An effective animal welfare strategy establishes a framework where this tension is addressed at the planning stage, before an animal’s welfare is compromised. A comprehensive and effective animal welfare strategy informs the business plan at the outset, guiding appropriate resource allocation, professional development for staff, etc., and in the process increases overall operational efficiency.

The Foundations of an Animal Welfare Strategy

To genuinely uphold their SLO and their welfare commitments, it is important for zoos to adopt a comprehensive strategy that integrates welfare across all aspects of their operation. To accomplish this outcome, we propose a structured, step-by-step approach to developing an animal welfare strategy, tailored to the meet the many needs of zoos. As described by More (2019), welfare policies are essentially ‘plans of action’. These policies should extend beyond the domain of animal husbandry to influence broader zoo operations, including conservation, education, financial planning, commercial operations, marketing, and more. By embedding welfare into all aspects of management, zoos can not only achieve enhanced animal care and welfare, but also yield significant operational advantages and improvements to mission outcomes. These benefits include, amongst others, improved efficiencies, stronger community engagement, and increased public support.

It should be a priority for zoos to have an animal welfare strategy. This imperative is reflected in regional associations such as The World Association of Zoos and Aquariums having an overarching animal welfare strategy (WAZA, 2025). Many zoos may already have animal welfare strategies, but they should be more broadly communicated and advertised. If zoos do not have an animal welfare strategy, it is in their best interest to adopt one as soon as possible, including a clear commitment to animal welfare advocacy both within the zoo and beyond, into the broader community.

Effective animal welfare strategies enable zoos to be progressive and proactive in achieving optimal welfare standards and should reflect a clear commitment to applied welfare research, individual welfare monitoring, regular assessments of welfare, and ongoing welfare enhancement (Sherwen et al. 2018). In addition, a strategy should ensure that the zoo proactively tackles public concerns about welfare by conducting regular horizon scans (i.e., community sentiment research) to identify any areas that are uncomfortable for local communities, addressing challenges as soon as they are presented (Veasey, 2022), and by directly advocating for improved welfare within the community. An animal welfare strategy should extend beyond simply mitigating welfare concerns, it should also establish a clear framework for actively enhancing and celebrating positive welfare.

Despite this clear understanding, there is little guidance available on how to create a zoo welfare strategy and the considerations upon which it should be based. A number of regional associations have created welfare strategies or frameworks (i.e., World Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ ‘

Caring for Wildlife - Animal Welfare Strategy’, Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ ‘

Strategic framework for the wellbeing of animals’ and the associated ‘

Guiding principles’ document, British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ ‘

BIAZA Welfare Policy’, and Zoo and Aquarium Association of Australasia’s ‘

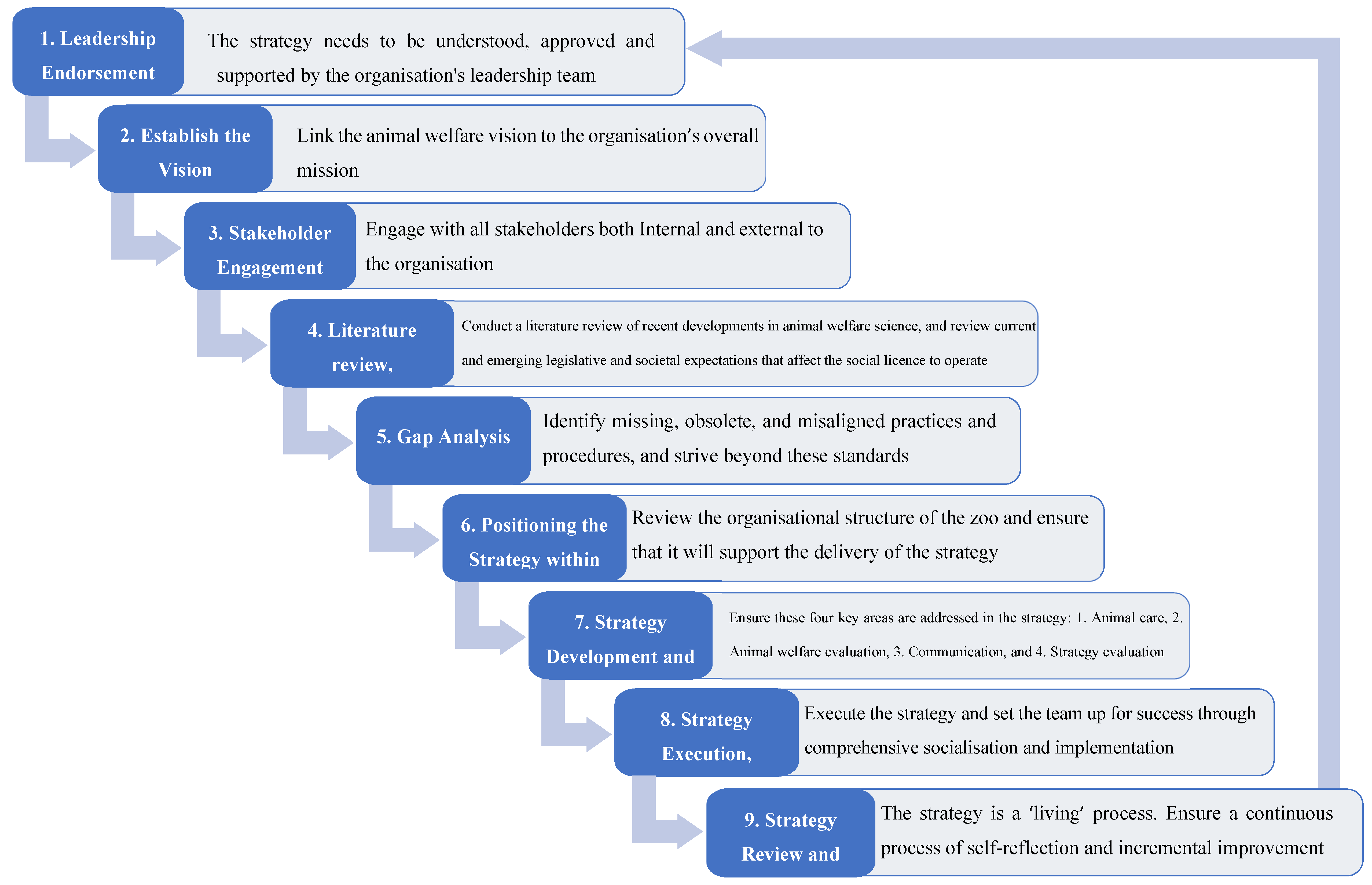

Animal Welfare Policy’). These documents provide useful guidelines and general principles for zoos to consider, however they do not meet the needs of the local conditions unique to each zoo. It is important for individual zoos to develop their own strategy that links to regional or global networks, while also setting their own standards to make it relevant to their own community and organisational priorities. We set out the steps required to develop an animal welfare strategy for a zoo or aquarium in

Figure 1, accommodating these specific conditions. Each step will be considered in term, but it is important to note how integrated and interconnected each of these steps is when developing a welfare strategy.

Step 1 - Leadership Endorsement

To ensure the success of a strategy, the policymaking process should be shaped by organisational culture, rules, and regulations, while also being informed by factors such as resource limitations (More, 2019), so these can be overcome without welfare being compromised. A successful strategy requires backing from a coalition of key internal and external stakeholders, both at the time of its inception and adoption, and throughout its implementation (Crosby & Bryson, 2018). A robust animal welfare strategy must be understood, approved, supported, and championed, by the organisation’s leadership team. Securing early ‘buy in’ and endorsement of an animal welfare strategy is an essential first step, especially if the development of the strategy was not initiated by the leadership team at the outset.

Step 2 - Establishing the Vision

A critical step in the development of a strategy is to establish a vision for animal welfare, requiring broad-ranging stakeholder engagement to capture diverse perspectives, address ethical considerations, and encourage ongoing broad adoption. Having a clear definition of animal welfare is essential, as it aligns efforts towards common goals, supporting establishment of the vision. The first round of stakeholder engagement should conclude by distilling down all the received feedback into a strong collective vision statement for animal welfare and establishing the high-level primary components of the strategy. Such a vision should be aspirational, focussed on what the organisation wants to achieve and work towards in animal welfare. Stakeholder engagement will continue throughout the process, but the vision statement becomes a guiding star to the ongoing development of the strategy.

Step 3 - Stakeholder Engagement

The strategy needs to capture as many of the needs of all stakeholder groups as possible. For strategic priorities to appropriately reflect stakeholder values and expectations, a multi-stakeholder approach is more effective than engagement at the level of a single stakeholder (Britton et al. 2021; Tanaka & Tanaka 2022). This approach is especially important for an animal welfare strategy, as stakeholders may share views, or have strongly differing opinions, in relation to what constitutes positive welfare, and how best to achieve optimal welfare for animals (Muhammad et al. 2022). Understanding the dynamics of stakeholder networks is vital, as collaborative approaches enable leaders in animal welfare to foster productive partnerships and develop policies that address the nuanced needs for animals, caretakers, and broader society (Fernandes et al. 2019). By incorporating diverse perspectives, the zoo will benefit from constructive feedback and collaborative problem-solving, which yields an improved strategy and better welfare outcomes.

Within a zoo setting, it is crucial to include ‘hands on’ stakeholders, such as animal care staff, veterinarians, and other animal management professionals. However, stakeholder groups should also encompass the full spectrum of zoo staff, including management, horticulture, technical services, marketing, visitor services, education, conservation, human resources, leadership, and volunteers. Each of these groups represent different business interests and contribute different sets of expertise, making the final strategy more robust.

Engaging the public is also important for ensuring transparency and fostering positive community relations. In addition to animal advocacy groups, community engagement can include zoo members, visitors, and local organisations, alongside government representatives, philanthropists, and researchers, ensuring a fully inclusive approach. Whist it is important to engage all stakeholders, it is equally essential to recognise that not all stakeholders have an equal level of interest, knowledge, or influence (Verrinder & Phillips, 2023) on the final strategy.

External and internal stakeholder feedback can be obtained in many ways, including surveys, workshops, focus groups, one-on-one interviews, literature reviews, and community engagement sessions. Collaborating with other zoos and aligning priorities is important, as it can make a significant positive impact, as opposed to working against one another. Collecting feedback from all stakeholders encourages them to take responsibility for enhancing program performance (Sheperis and Bayles 2022), ensuring the strategy remains relevant, dynamic, and responsive, and helps secure organisation- and community-wide support.

Step 4 – Literature Review, Legislation, and Societal Expectations

Conducting a literature review on current animal welfare science pertaining to animals housed in zoos will help establish a strong knowledge base, identify gaps in the strategy, and help to inform policy and procedures. An animal welfare strategy should consider any regional zoo association welfare and accreditation standards, recent developments in our collective understanding of animal welfare science, relevant stakeholder feedback (discussed above), an understanding of the available institutional resources, and the zoo’s aspirational goals and core mission. To aid in this process, all existing relevant internal policies and procedures related to welfare should be reviewed and updated. This documentation can include strategic business plans, with associated key performance indicators, animal welfare charters and codes of conduct, animal record-keeping processes and archival record-keeping, husbandry manuals, ongoing research programs, species management and planning processes, and the animal welfare and ethics committee’s terms of reference (refer below). As part of this policy review process, it is critical to assess existing animal welfare evaluation mechanisms at the zoo, which could include animal welfare assessments, animal transfer protocols, enclosure design protocols, quality of life assessments, health and nutritional assessments, environmental enrichment programs and protocols, and behavioural monitoring programs (such as animal-visitor interactions and training). In addition, a review of municipal, state, and federal animal welfare legislation and accreditation processes is recommended, as they are the primary bodies responsible for defining, penalising, and ideally preventing animal cruelty (Morton, et al. 2020), and promoting positive animal welfare.

Step 5 - Gap Analysis

Once the aforementioned resources have been collected and compiled, a gap analysis should be performed. The gap analysis should identify missing, obsolete, or misaligned practices and procedures, ensuring that they align with legislation and best practice, noting that legislative requirements are intended to prevent negative animal welfare states (Melfi, 2009), and that best practice aims to strive beyond these standards. Evidence-based management has gained significant momentum in recent years (Kaufmann et al. 2019; Brereton & Rose 2022) and should be included in the gap analysis, as evidence plays a key role in inferring welfare states. The gap analysis is essential to highlighting discrepancies between aspiration and reality (Kaplan et al. 2008), setting the foundation for a more robust animal welfare strategy, and for more practical and effective practices.

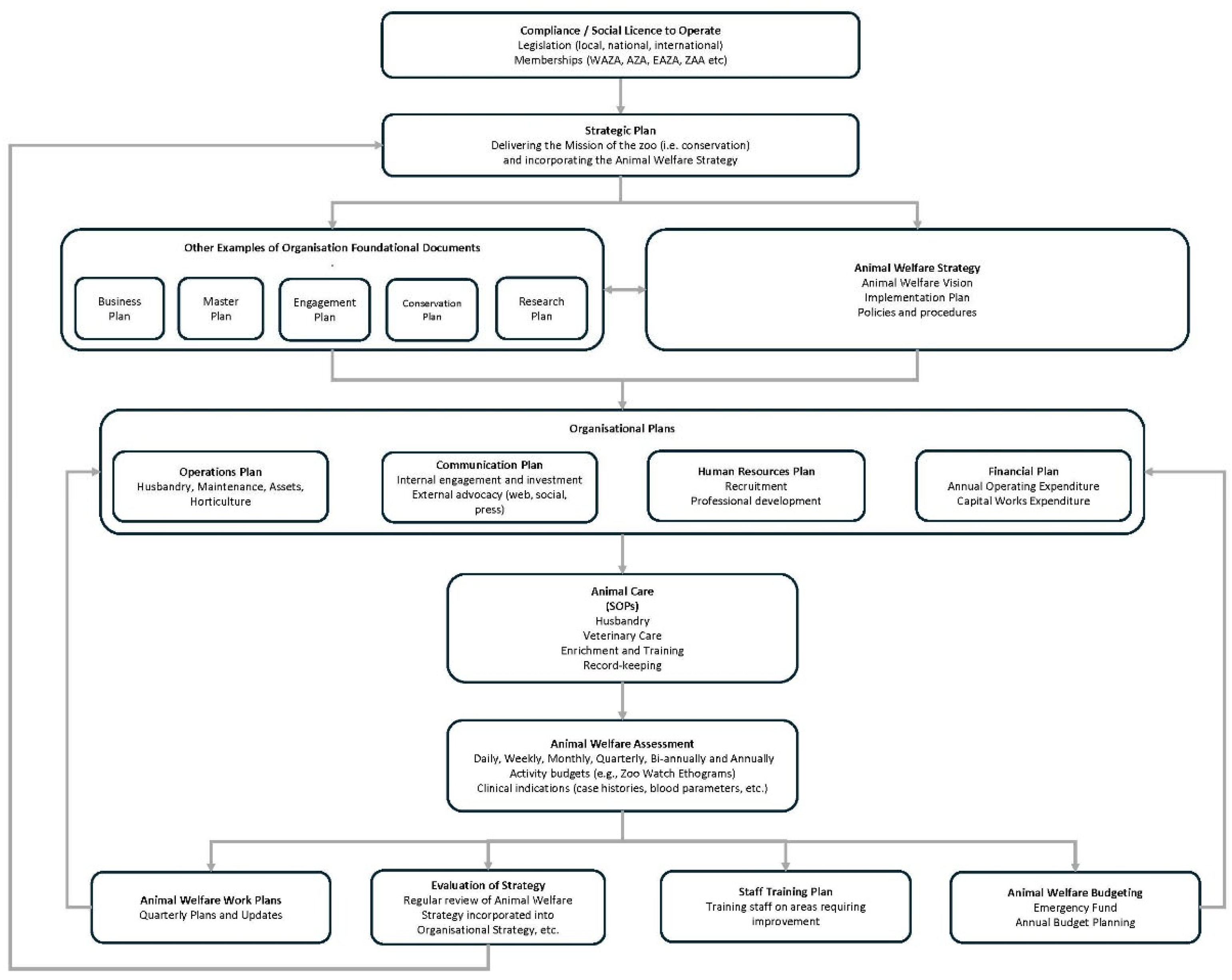

Step 6 – Positioning the Strategy within the Organisation

A crucial component of any animal welfare strategy is determining how it sits within the broader organisational structure of the zoo. Most zoos have a set of foundational documents that guide their operations, including planning documents (e.g., master plan, business plan) and operational charters (e.g., sustainability charter, accessibility charter). These guiding documents are typically reviewed and updated every 3-5 years, and are aligned under an overarching organisational strategic plan, intended to ensure the delivery of the organisation’s mission. To be most effective, an animal welfare strategy should be fully embedded within this interconnected business framework, particularly within the organisational strategic plan, to ensure that all guiding documents align and support one another (

Figure 2).

The strategy should reference legislative and compliance requirements and align with the organisation’s guiding principles and foundational documents, and should inform institutional plans—e.g., operations, communication, human resources, financial, etc. These elements work together to deliver animal care and welfare outcomes, and incorporate the welfare evaluation process, which drives the creation of welfare work plans, staff training plans, and budgeting priorities. The organisational framework emphasises the importance of continuously evaluating the effectiveness of the animal welfare strategy to ensure ongoing improvement and adherence to the highest standards of animal welfare.

The next key step in advancing a welfare strategy is to establish a team responsible for developing and implementing policies and programs aimed at understanding, improving, and evaluating welfare (Kagan et al., 2015). This team needs to take ownership of the strategy, be empowered to act under it, and to make improvements where needed. It is critical that this team is adequately resourced for the task. Whilst a team-based approach is ideal, the strategy still requires a ‘champion’, a person that is primarily responsible for managing the day-to-day planning process. The champion should track progress, push the process along, encourage, and ensure all details are carefully attended to (Crosby & Bryson, 2018). The champion must have the unequivocal support of the zoo leadership team. Some zoos employ dedicated animal welfare scientists, as recommended by Ward et al. (2018), who can promptly address early welfare challenges identified by keepers and veterinarians, conduct targeted research, and collaborate with external experts. Recruiting highly educated scientists skilled in research, public education, and responsible decision-making, also is beneficial, as their expertise—whether in-house or through strategic partnerships—helps prevent misdirected criticism and poor decision-making (Maple and Perdue 2013). The welfare champion should be determined, well-versed in animal welfare science, and an inspiring communicator who can articulate a clear vision and ensure the successful development and implementation of the strategy.

Step 7 – Strategy Development and Ground Truthing

To ensure the animal welfare strategy sets up an environment that effectively manages, assesses, and improves welfare it is helpful to break the strategy down into the following four components: (1) animal care; (2) animal welfare assessment; (3) communication (internal and external); and (4) strategy evaluation. Each of these components should be aligned with measurable goals and will be described in more detail below.

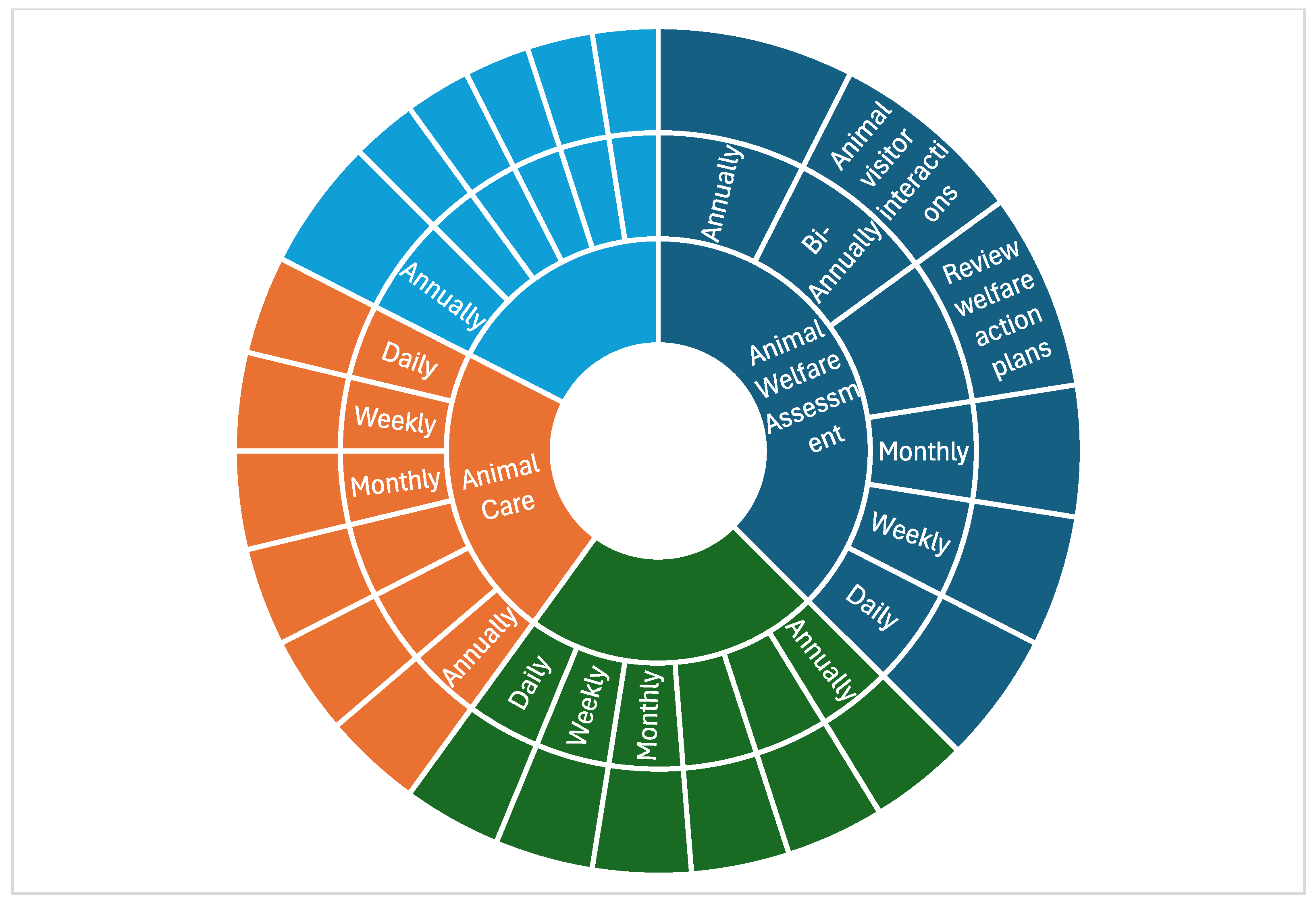

Once the framework is established, clear objectives should be defined using measurable, time-bound KPIs to track progress that aligns with the strategy and support the overall vision. A five-year timeline with milestones and regular evaluations allows for continuous refinement. Using the SMART model—specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound—ensures strategic goals are effectively met. The sunburst diagram detailed in

Figure 3 illustrates an example of an evaluation process where KPIs are tracked at effective intervals. This structured approach ensures continuous monitoring across all aspects of the strategy, from animal care to staff training, fostering ongoing improvements in animal welfare standards.

Zookeepers play a critical role in providing care for animals (Sherwen & Hemsworth, 2019). To achieve their goals, zoos should require that all staff responsible for animal care possess a strong understanding of recent advancements in animal welfare and husbandry techniques (Bacon et al. 2023). Yet, whilst there is a connection between animal care and animal welfare, they do not seamlessly align. Welfare indicators are typically divided into two primary categories: (1) resource-based indicators, or “inputs,” which refer to the resources or management practices provided to the animals, such as space, environmental complexity, healthcare, and nutrition; and (2) animal-based measures, or “outputs,” which assess the animal’s actual welfare state through a variety of means, for example, physiological health and behavioural indicators (Velarde & Dalmau 2012; Tallo-Parra et al. 2023). Both inputs and outputs are important to understand and quantify when assessing welfare.

This paper is not intended to detail every aspect of animal care for different zoo species. That work is for the relevant taxon specialists and animal carers/keepers. However, when creating an animal welfare strategy, all animal care disciplines need to be considered, including animal training and behaviour management programs, enrichment programs, nutrition evaluation and food preparation, health care, habitat design and substrate selection, animal visitor interaction programs, and professional development for staff. Each of these disciplines implies inputs that must be examined when assessing animal welfare.

Provision of adequate resources alone does not guarantee that an individual will experience positive welfare (Kagan et al. 2018). Animal-based measures, or outputs, must be assessed to fully understand the welfare status of the animal in question. Optimal welfare is only achieved when an animal’s physical, social, and psychological needs are fully met, including the essential ability to exercise agency, make decisions, and have control over their daily activities (Kagan & Veasey 2010). It is also important to remember that every individual is unique, resulting in individual-specific needs (Tallo-Para et al. 2023) and a broader range of possible collective experiences.

- 2.

Animal Welfare Assessment

Evaluating animal welfare within a zoo can be challenging, as there is no universally standardised method, and many zoos lack the formalised procedures for welfare assessment. However, many well-managed zoos, along with regional zoo associations, have taken proactive steps to develop their own systems for assessing, evaluating, and enhancing animal welfare. These assessments are often informed by standards, regulations, and guidelines from accreditation bodies such as AZA, ZAA, AZA, EAZA, and BIAZA (AZA 2025; BIAZA 2025; EAZA 2025; ZAA 2025).

Effective welfare evaluation requires the use of clear, objective, evidence-based assessment methods. These assessment tools can be developed internally and can include species-specific or taxa-specific tools for different animal groups (e.g., birds, mammals, reptiles, ungulates). Many zoos have already developed these tools and are more than willing to share with others, which can be a great place to start and can save significant time. Animal welfare assessments should extend beyond just vertebrates (Escobar-Ibarra et al. 2021), as zoos have an ethical responsibility to promote good welfare for all individuals and ensure that animals, no matter their taxon, are experiencing optimal welfare. In addition, assessments may need to be tailored to accommodate different life stages or reproductive statuses. Recent progress in the field of welfare assessments has led to the development of various tools, including universal welfare framework surveys (Kagan et al. 2015), species-general welfare assessments (O’Brien & Cronin 2023), animal welfare risk assessments (Sherwen et al. 2018), and species-specific evaluation methods (Benn et al. 2019; Clegg et al. 2015).

Many tools use behaviour analyses as a source of evidence when assessing welfare. Monitoring animal behaviour is crucial, as it provides insight into the emotional states of individuals (Bacon 2018; Wolfensohn et al. 2018), and the animals responses to their surroundings, allowing an inference of welfare state. Despite the clear utility of behaviour as a measurable output, the reader is cautioned against over-reliance on this metric alone, as it can bias and comprise the assessment. In addition, other animal-based measures, such as physiological indications, keeper ratings (Tallo-Parra et al. 2023), and qualitative behavioural assessments (Yon et al. 2019), as well as cognitive bias (Clegg 2018) analyses, can be applied as an adjunct. Readers seeking a more detailed exploration of this matter are encouraged to consult Jones et al. (2022) and Tallo-Parra et al. (2023).

- 3.

Communication (Internal and External)

Communication of the animal welfare strategy, in a coherent and consistent manner, is fundamental to its successful implementation. This process should include both internal and external stakeholders to ensure broad awareness of the strategy, and clarity about the required actions to support its implementation. The key elements to consider for inclusion in a communication section include: establishment of an animal welfare and ethics committee, an animal welfare and ethics charter, education/professional development for staff, social media policy, visitor engagement with animal welfare and animal welfare feedback process.

If it does not already exist, it is highly recommended to establish an animal welfare and ethics committee, including members from throughout the zoo and some independent non-zoo members with knowledge of welfare science (e.g., a staff member of the RSPCA). This committee plays an important role in overseeing the animal welfare strategy, ensuring the ethical treatment and welfare of animals throughout the organisation. The committee can provide independent advice on welfare questions, ethical dilemmas or ‘wicked’ problems, compliance, community engagement, and relevant welfare research. The committee should be composed of staff members who are well-versed and trained in animal welfare science, and internal and external stakeholders with and without formal training in animal welfare to support broader objectivity (Miller & Chinnadurai 2023).

In addition to the establishment of a dedicated committee, an animal welfare and ethics charter should be drafted and implemented that clearly articulates the zoo’s expectations about how its staff will engage with animal welfare throughout their day-to-day operations. A charter is stronger if the staff are mandated to read and commit to the charter. Furthermore, it is recommended that the zoo’s mission statement clearly and transparently prioritise animal care and welfare, positioning them as central to its values—akin to the importance of conservation in a modern zoo (Maple & Perdue, 2013).

Another key aspect of a comprehensive animal welfare strategy is educating stakeholders about animal welfare science. Brando et al. (2023) found that many zoo professionals do not have access to appropriate professional development opportunities. Educating stakeholders is essential, as assessing animal welfare is seemingly intuitive and yet it is a nuanced and complex matter with significant societal implications. Passionate disagreements can ensue when stakeholders have different perspectives on how animal welfare should be defined and evaluated (DiVincenti et al. 2023). Educating zoo staff and providing them professional development opportunities is essential, as it empowers them to apply best practice science principles to questions of animal welfare, ensuring decisions are guided by evidence and best practice and not by visceral reactions and intuitions.

Social media continues to grow in popularity and is an effective platform for sharing information rapidly and to a very large audience (Meikle, 2016), so it can be a very powerful communication tool. It is highly recommended that, if not already in existence, the zoo adopt a clear social media policy to effectively communicate and support their commitment to positive animal welfare and transparency that is aligned with the zoos’ mission.

It is important that visitors develop an understanding of animal welfare when visiting zoos.

Figure 4 presents an example infographic used to communicate the five domains model of animal welfare as it applies to zoo animals. This visual overview makes it easier for both staff and the public, especially those who do not work directly with animals, to understand the key components of the Five Domains model and associated techniques used to manage animal welfare. By highlighting both input and output measures for assessing welfare, the infographic serves as an educational tool, promoting awareness and fostering better communication about how animal welfare is monitored and maintained. This visual guide helps demystify animal welfare, encourages a deeper understanding of, and connection to, the zoo’s mission, and empowers staff and visitors alike to contribute to the overall welfare of animals.

One final and essential form of communication must be included within the strategy: a mechanism that allows staff, volunteers, or zoo visitors to raise questions or concerns about animal welfare without fear of censure, retribution, or derision. A well-functioning team escalates concerns about animal welfare up through identified channels within the organisational hierarchy, with a formal response provided once the concern has been investigated (Kagan, 2015). In rare circumstances, where this approach is not functioning, an alternative mechanism should be provided. This can entail an in confidence direct communication with the animal welfare officer or the animal welfare and ethics committee. In addition, the culture surrounding what is traditionally considered ‘whistleblowing’ needs to change towards viewing it as valuable ‘information gathering’. Zoos should embrace open feedback as an opportunity to enhance transparency and improve their practices, rather than something to be resisted.

- 4.

Strategy Evaluation: A Continuous Journey of Improvement

Strategy evaluation is an ongoing process. Tracking KPIs, and assessing longer-term metrics, that indicate the strategy is working can include measures such as changing trends in animal welfare evaluation scores, the range and effectiveness of enrichment programs, the proportion of animals in preventative health care training programs, or the extent to which real-time welfare tracking is used across the zoo, to name just a few.

In addition to specific and directed metrics, it is valuable to evaluate broader measures of the zoo’s performance. Financial support tied directly to animal welfare is a measure of success, as is the proportion of staff undertaking animal welfare professional development, both of which build capacity for improving welfare standards. Feedback from stakeholders, both internal and external, is another measure of strategy evaluation. Gathering and responding to these insights ensures that the strategy remains aligned with the needs and expectations of the community. Finally, ground truthing the strategy, with direct evidence, ensures it delivers on its promise—improving animal welfare.

Step 8 – Strategy Execution, Socialisation and Implementation

Once the strategy has been developed and mechanisms are in place to check its effectiveness, it is time to execute. Organisational changes often fail when improvements to practices and procedures are not implemented effectively (Tuite et al. 2022). Successfully executing a strategy requires the ability to effectively implement the planned actions and achieve the outlined goals (Abedian and Hejazi 2023). Implementing an animal welfare strategy effectively depends on ensuring that all staff members have a shared and comprehensive understanding of its structure, goals, and objectives. Maintaining a flexible approach, whereby KPIs are regularly reviewed and adjusted as needed, ensures the strategy remains responsive to emerging challenges and helps staff stay focused and motivated. While it is natural to focus on problems or setbacks, it is equally important to celebrate successes and acknowledge progress made toward improving animal welfare, recognising that, like any definition of welfare, the focus should not only be on addressing compromised welfare but also on proactively enhancing positive welfare outcomes.

Step 9 – Strategy Review and Revitalisation

For an animal welfare strategy to be truly effective, it must go far beyond a simple “tick box” exercise. An effective strategy requires strong support from leadership and management, at all levels, to ensure that it is integrated into the zoo’s core operations and fully supports the zoo’s overarching mission. Effective evaluation goes beyond tracking data and outcomes, it should also include an ongoing cycle of reflection and adaptation. This approach requires strong support from leadership and management, at all levels, to ensure that it is integrated into the zoo’s core operations and fully supports the zoo’s overarching mission. It is essential to monitor not just successes but also instances where expectations have not been met. Identifying deviations from expected outcomes, or areas where the strategy did not deliver as anticipated, can highlight areas that need more attention, adjustment, or resourcing. In addition, it is critically important that the zoo’s team remain informed of the latest developments in animal welfare science and incorporate changes to best practices wherever the emerge. This approach ensures that that zoo is continually improving its animal care practices and the associated animal welfare outcomes. The animal welfare and ethics committee is a good organising mechanism to keep the strategy on track and relevant, and, ultimately, result in positive animal welfare within the zoo and the broader community at large.

Challenges present opportunities to innovate and refine processes further. For example, using technologies such as AI are worth investigation, as they are transforming how animal behaviour is interpreted, providing valuable insight that enhances animal welfare, supports conservation efforts, improves research, and optimises animal management (Fuentes et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2023). Though these changes may require an initial commitment to training and some modest investment, they result in faster, more efficient, and effective welfare assessments, helping the organisation make informed decisions about animal care and supporting an environment where the animals can thrive.

Conclusion

Zoos must adopt a comprehensive strategy to ensure the ongoing assessment and enhancement of animal welfare, rooted in the latest scientific advancements. Establishing a clear framework, endorsed by leadership and adequately resourced, provides a strong foundation for a coherent strategy and improved animal welfare. An effective strategy should be structured around four primary areas—animal care, animal welfare assessment, communication, and strategy evaluation—ensuring a comprehensive institution-wide commitment to animal welfare. Meaningful stakeholder engagement is vital to embed animal welfare into policies, practices, and daily care, with a commitment to maintaining welfare throughout each animal’s lifetime. Transparency in evaluating and implementing welfare standards builds public trust and reinforces the zoo’s social licence to operate. Furthermore, strategic planning should cascade seamlessly from high-level objectives to operational practices, ensuring animal welfare is prioritised across all aspects of zoo management. By integrating these different elements, zoos can create a robust system that meets ethical and scientific standards, while fostering continual improvement in animal welfare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.K.P; feedback and guidance, S.L.S, M.F.L.S, L.M.R, A.L.W; writing – original draft preparation, J.K.P; writing – review and editing, J.K.P, S.L.S, M.F.L.S, L.M.R, A.L.W; supervision, S.L.S and A.L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the use of AI-assisted tools, including Chat GTP, in the preparation of this manuscript. These tools were used to assist with language refinement and formatting but did not contribute to the development of the Animal Welfare Strategy or its content.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Abedian, M; Hejazi, M. 2023 Optimal strategy selection under fuzzy environment for strategic planning methodology selection: A SWOT approach. Cybernetics and Systems. [CrossRef]

-

Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) 2025. 1 February 2025. Available at Accessed. Available online: http://www.aza.org.

- Bacon, H. Behaviour-based husbandry—a holistic approach to the management of abnormal repetitive behaviors. Animals 2018, 8(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, H; Vigors, B; Shaw, DJ; Waran, N; Dwyer, CM. and Bell C 2023 Zookeepers–The most important animal in the zoo? Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 26(4), 634–646. [CrossRef]

- Benn, AL; McLelland, DJ; Whittaker, AL. 2019 A review of welfare assessment methods in reptiles, and preliminary application of the welfare quality® protocol to the pygmy blue-tongue skink, tiliqua adelaidensis, using animal-based measures. In Animals; MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Brando, S; Rachinas-Lopes, P; Goulart, VDLR. and Hart LA 2023 Understanding job satisfaction and occupational stressors of distinctive roles in zoos and aquariums. Animals 13(12). [CrossRef]

- Brereton, J; Rose, P. 2022 An evaluation of the role of ‘biological evidence’ in zoo and aquarium enrichment practices. Animal Welfare 31(1), 13–26. [CrossRef]

- Brereton, SR; Brereton, JE. 2020 Sixty years of collection planning: what species do zoos and aquariums keep? International Zoo Yearbook 54(1), 131–145. [CrossRef]

-

British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums (BIAZA) 2025. 1 February 2025. Available at Accessed. Available online: http://biaza.org.uk/animal-welfare.

- Britton, E; Domegan, C; McHugh, P. 2021 Accelerating sustainable ocean policy: The dynamics of multiple stakeholder priorities and actions for oceans and human health. Marine Policy 124, 104333. [CrossRef]

- Broom, DM. Sentience and animal welfare; CABI, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg, ILK. Cognitive bias in zoo animals: An optimistic outlook for welfare assessment. In Animals; MDPI AG, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, ILK; Borger-Turner, JL; Eskelinen, HC. C-Well: The development of a welfare assessment index for captive bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Animal Welfare 24(3), 267–282. [CrossRef]

- Clubb, R; Mason, G J. Natural Behavioral Biology as a Risk Factor in Carnivore Welfare: How Analysing Species Differences Could Help Zoos Improve Enclosures. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 2007, 102, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, G. Public animal welfare discussions and outlooks in Australia. Animal Frontiers 8(1), 14–19. [CrossRef]

-

Conway WG 2011 Buying time for wild animals with zoos. Zoo Biology 30, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Crosby, B.C.; Bryson, J.M. Chapter eleven: Leadership roles in making strategic planning work. In Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organizations: A guide to strengthening and sustaining organizational achievement; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2018. [Google Scholar]

- DiVincenti, L; McDowell, A. Herrelko ES 2023 Integrating individual animal and population welfare in Zoos and Aquariums. In Animals; MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, IJH. A Concept of Welfare Based on Feelings. In The Well-Being of Farm Animals; Wiley; pp. 85–101. [CrossRef]

- Englund, MD. Cronin KA 2023 Choice, control, and animal welfare: definitions and essential inquiries to advance animal welfare science. In Frontiers in Veterinary Science; Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Ibarra, I; Mota-Rojas, D; Gual-Sill, F; Sánchez, CR; Baschetto, F; Alonso-Spilsbury, M. 2021 Conservation, animal behaviour, and human-animal relationship in zoos. Why is animal welfare so important? Journal of Animal Behaviour and Biometeorology 9(1), 1–17. [CrossRef]

-

European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) 2025 EAZA Zoos and Aquariums. 1 February 2025. Available at Accessed. Available online: http://www.eaza.net.

- Fernandes, J; Blache, D; Maloney, SK; Martin, GB; Venus, B; Walker, FR. Head B and Tilbrook A 2019 Addressing animal welfare through collaborative stakeholder networks. Agriculture (Switzerland) 9(6). [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D. Understanding animal welfare. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 50(1), 1–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, S; Viejo, C G; Tongson, E; Dunshea, F R. 2022 The livestock farming digital transformation: Implementation of new and emerging technologies using artificial intelligence. Animal Health Research Reviews 1–13.

-

Gray J 2017 Zoo ethics: The challenges of compassionate conservation; Csiro Publishing.

- Greenwell, PJ; Riley, LM; Lemos de Figueiredo, R; Brereton, JE. Mooney A and Rose PE 2023 The societal value of the modern zoo: A commentary on how zoos can positively impact on human populations locally and globally. Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens 4(1), 53–69. [CrossRef]

- Hampton, JO; Hemsworth, LM; Hemsworth, PH; Hyndman, TH; Sandøe, P. 2023 Rethinking the utility of the Five Domains model. Animal Welfare 32. [CrossRef]

- Hampton, JO; Jones, B. McGreevy PD 2020 Social license and animal welfare: Developments from the past decade in Australia. Animals 10(12), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Harley, J. Rose, P., Ed.; 2023 Behavioural biology in animal collection planning and conservation. In The behavioural biology of zoo animals; CRC Press; pp. 11–20.

- Jones, N; Sherwen, S L; Robbins, R; McLelland, D J. Whittaker A L 2022 Welfare assessment tools in zoos: From theory to practice. Veterinary Sciences 9(4), 170. [CrossRef]

- Kagan, R; Allard, S; Carter, S. What is the future for Zoos and Aquariums? Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 21(sup1), 59–70. [CrossRef]

- Kagan, R; Carter, S; Allard, S. A Universal Animal Welfare Framework for Zoos. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagan, R; Veasey, J. Kleiman, D. G., Thompson, K. V., Baer, C. K., Eds.; Challenges of zoo animal welfare. In Wild mammals in captivity: Principles and techniques for zoo management, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press; pp. 439–450.

- Kaplan, RS; Norton, DP. Barrows EA 2008 The strategy execution source: Developing the Strategy: vision, value gaps, and analysis. Retrieved from. Available online: http://bsr.harvardbusinessonline.org.

- Kaufman, A B; Bashaw, M J. Maple T L 2019 Scientific foundations of zoos and aquariums: Their role in conservation and research; Cambridge University Press.

- Kleiman, DG. Criteria for the evaluation of zoo research projects. Zoo Biology 93–98. [CrossRef]

-

Maple TL and Perdue BM 2013 Launching Ethical Arks. 167–183. [CrossRef]

- Martin, S; Stafford, G; Miller, DS. A Re examination of the relationship between training practices and welfare in the management of ambassador animals. Animals 2024, 14(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, L; Jacobson, SK; Monroe, MC. Savage A 2020 Mission impossible or mission accomplished: Do zoo organizational missions influence conservation practices? Zoo Biology 39(5), 304–314. [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, SP. A Critique of FAWC’s Five Freedoms as a Framework for the Analysis of Animal Welfare. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 26(5), 959–975. [CrossRef]

- Meikle, G. 2016 Social media: Communication, sharing and visibility; Routledge.

- Melfi, V. There are big gaps in our knowledge, and thus approach, to zoo animal welfare: A case for evidence-based zoo animal management. Zoo Biology 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, DJ. Updating animal welfare thinking: Moving beyond the “five freedoms” towards “A lifeworth living”. Animals 6(3). [CrossRef]

- Mellor, DJ; Beausoleil, NJ. Extending the ‘Five Domains’ model for animal welfare assessment to incorporate positive welfare states. Animal Welfare 24(3), 241–253. [CrossRef]

- Mellor, DJ; Beausoleil, NJ; Littlewood, KE; McLean, AN; McGreevy, PD; Jones, B; Wilkins, C. 2020 The 2020 five domains model: Including human–animal interactions in assessments of animal welfare. Animals. MDPI AG 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Miller, L J; Chinnadurai, S K. 2023 Beyond the five freedoms: Animal welfare at modern zoological facilities. Animals 13(11), 1818. [CrossRef]

- Minteer, BA; Collins, JP. Ecological ethics in captivity: Balancing values and responsibilities in zoo and aquarium research under rapid global change. ILAR Journal 54(1), 41–51. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R; Escribano, N; Casas, M; Pino-Del-Carpio, A; Villarroya, A. 2024 The role of Zoos and Aquariums in a changing world. 18, 24. [CrossRef]

-

More SJ 2019 Perspectives from the science-policy interface in animal health and welfare. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 6. [CrossRef]

- Morton, R; Hebart, ML; Whittaker, AL. 2020 Explaining the gap between the ambitious goals and practical reality of animal welfare law enforcement: A review of the enforcement gap in Australia. In Animals; MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M; Stokes, JE; Morgans, L. Manning L 2022 The social construction of narratives and arguments in animal welfare discourse and debate. Animals. MDPI. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, SL. and Cronin KA 2023 Doing better for understudied species: Evaluation and improvement of a species-general animal welfare assessment tool for zoos. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 264, 105965. [CrossRef]

- Ohl, F; Putman, R. The biology and management of animal welfare; Whittles Publishing, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reimert, I; Webb, LE; van Marwijk, MA; Bolhuis, JE. 2023 Review: Towards an integrated concept of animal welfare. In Animal; Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Rose, PE. Riley LM 2022 Expanding the role of the future zoo: Wellbeing should become the fifth aim for modern zoos. Frontiers in Psychology 13. [CrossRef]

- Sheperis, CJ; Bayles, B. 2022 Empowerment evaluation: A practical strategy for promoting stakeholder inclusion and process ownership. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 13(1), 12–21. [CrossRef]

- Sherwen, SL; Hemsworth, LM; Beausoleil, NJ; Embury, A; Mellor, DJ. An animal welfare risk assessment process for zoos. Animals 8(8). [CrossRef]

- Sherwen, SL; Hemsworth, PH. The visitor effect on zoo animals: Implications and opportunities for zoo animal welfare. In Animals; MDPI AG, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, SL; Walker, SL; Dowell, S. and Moss A 2023 The value of zoos for species and society: The need for a new model. In Biological Conservation; Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Tallo-Parra, O; Salas, M. Manteca X 2023 Zoo animal welfare assessment: Where do we stand? Animals. MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H. Tanaka C 2022 Sustainable investment strategies and a theoretical approach of multi-stakeholder communities. Green Finance 4(3), 329–346. [CrossRef]

- Tuite, E K; Moss, S A; Phillips, C J; Ward, S J. Why are enrichment practices in zoos difficult to implement effectively? Animals 2022, 12, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veasey, JS. 2020 Can Zoos ever be big enough for large wild animals? A review using an expert panel assessment of the psychological priorities of the Amur Tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) as a model Species. Animals 10(9), 1536. [CrossRef]

- Veasey, JS. Differing animal welfare conceptions and what they mean for the future of zoos and aquariums, insights from an animal welfare audit. Zoo Biology 41(4), 292–307. [CrossRef]

- Velarde, A; Dalmau, A. 2012 Animal welfare assessment at slaughter in Europe: Moving from inputs to outputs. Meat Science 244–251. [CrossRef]

- Verrinder, JM. Knight, A., Phillips, C. J., Sparks, P., Eds.; Phillips CJC 2023 Stakeholder groups and perspectives. In Routledge Handbook of Animal Welfare, 1st ed.; Routledge.

- Vigors, B; Sandøe, P. and Lawrence AB 2021 Positive welfare in science and society: Differences, similarities and synergies. Frontiers in Animal Science 2. [CrossRef]

- Ward, SJ; Sherwen, S; Clark, FE. Advances in Applied Zoo Animal Welfare Science. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 21(sup1), 23–33. [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, AL; Barker, TH. A consideration of the role of biology and test design as confounding factors in judgement bias tests. In Applied Animal Behaviour Science; Elsevier B.V, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfensohn, S; Shotton, J; Bowley, H; Davies, S; Thompson, S; Justice, WSM. 2018 Assessment of welfare in zoo animals: Towards optimum quality of life. In Animals; MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

-

World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) 2025 Committing to Conservation: The World Zoo and Aquarium Conservation Strategy. Retrieved from. Available online: http://www.waza.org/en/site/conservation/conservation-strategies.

- Yeates, J W. Animal welfare in veterinary practice; Wiley Blackwell.

- Yon, L; Williams, E; Harvey, ND; Asher, L. 2019 Development of a behavioural welfare assessment tool for routine use with captive elephants. PLoS ONE 14(2). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L; Guo, W; Lv, C; Guo, M; Yang, M; Fu, Q; Liu, X. Advancements in artificial intelligence technology for improving animal welfare: Current applications and research progress. ” Animal Research and One Health 2024, 2, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Zoo and Aquarium Association Australasia (ZAA) 2025. 1 February 2025. Available at Accessed. Available online: https://www.zooaquarium.org.au/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).