Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire and Measures

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

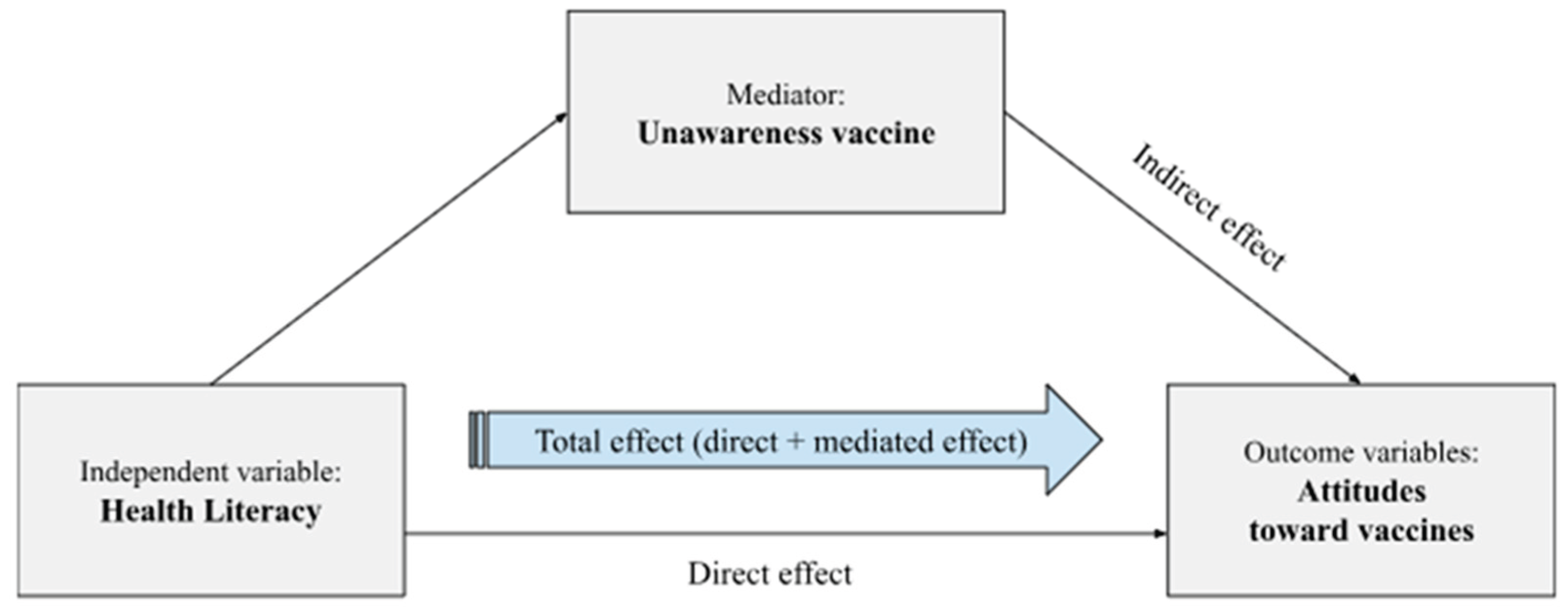

3.1. Mediator Models

3.2. Outcome Models

4. Discussion

5. Limitation and Future Direction

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HL | Health Literacy |

| VU | Vaccine unawareness |

| VAX-I | Vaccination Attitudes Examination scale (-Italian Version) |

| TTM | Transtheoretical model |

| VL | Vaccine Literacy |

References

- Antona, D. (2022). [Vaccination, a public health tool]. Revue de l’infirmiere, 71(279), 16–18. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E., Dai, Z., Wang, S., Wang, X., Zhang, X., & Fang, Q. (2023). Vaccine Literacy and Vaccination: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Public Health, 68. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2024, April 24). Global immunization efforts have saved at least 154 million lives over the past 50 years. Https://Www.Who.Int/News/Item/24-04-2024-Global-Immunization-Efforts-Have-Saved-at-Least-154-Million-Lives-over-the-Past-50-Years.

- Lorini, C., Santomauro, F., Donzellini, M., Capecchi, L., Bechini, A., Boccalini, S., Bonanni, P., & Bonaccorsi, G. (2018). Health literacy and vaccination: A systematic review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 14(2), 478–488. [CrossRef]

- Lorini, C., Lastrucci, V., Mantwill, S., Vettori, V., Bonaccorsi, G., & Florence Health Literacy Research Group. (2019). Measuring health literacy in Italy: a validation study of the HLS-EU-Q16 and of the HLS-EU-Q6 in Italian language, conducted in Florence and its surroundings. Annali Dell’Istituto Superiore Di Sanita, 55(1), 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Gusar, I., Konjevoda, S., Babić, G., Hnatešen, D., Čebohin, M., Orlandini, R., & Dželalija, B. (2021). Pre-Vaccination COVID-19 Vaccine Literacy in a Croatian Adult Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 7073. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Health promotion glossary of terms 2021 (Inis Communication, Ed.).

- Sørensen, K., van den Broucke, S., Fullam, J., Doyle, G., Pelikan, J., Slonska, Z., & Brand, H. (2012). Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 80. [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. (2023, January). Guide to health literacy. Contributing to trust building and equitable access to healthcare . Https://Rm.Coe.Int/Inf-2022-17-Guide-Health-Literacy/1680a9cb75.

- Berkman, N. D., Sheridan, S. L., Donahue, K. E., Halpern, D. J., Viera, A., Crotty, K., Holland, A., Brasure, M., Lohr, K. N., Harden, E., Tant, E., Wallace, I., & Viswanathan, M. (2011). Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, 199, 1–941.

- Rowlands, G., Khazaezadeh, N., Oteng-Ntim, E., Seed, P., Barr, S., & Weiss, B. D. (2013). Development and validation of a measure of health literacy in the UK: the newest vital sign. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 116. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Wang, D., Liu, C., Jiang, J., Wang, X., Chen, H., Ju, X., & Zhang, X. (2020). What is the meaning of health literacy? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Family Medicine and Community Health, 8(2), e000351. [CrossRef]

- Sundell, E., Wångdahl, J., & Grauman, Å. (2022). Health literacy and digital health information-seeking behavior - a cross-sectional study among highly educated Swedes. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 2278. [CrossRef]

- Biasio, L. R., Zanobini, P., Lorini, C., Monaci, P., Fanfani, A., Gallinoro, V., Cerini, G., Albora, G., del Riccio, M., Pecorelli, S., & Bonaccorsi, G. (2023). COVID-19 vaccine literacy: A scoping review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 19(1). [CrossRef]

- Bostock, S., & Steptoe, A. (2012). Association between low functional health literacy and mortality in older adults: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ, 344(mar15 3), e1602–e1602. [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. W., Gazmararian, J. A., Williams, M. v, Scott, T., Parker, R. M., Green, D., Ren, J., & Peel, J. (2002). Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among Medicare managed care enrollees. American Journal of Public Health, 92(8), 1278–1283. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B. D., & Palmer, R. (2004). Relationship between health care costs and very low literacy skills in a medically needy and indigent Medicaid population. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 17(1), 44–47. [CrossRef]

- Zanobini, P., Lorini, C., Caini, S., Lastrucci, V., Masocco, M., Minardi, V., Possenti, V., Mereu, G., Cecconi, R., & Bonaccorsi, G. (2022). Health Literacy, Socioeconomic Status and Vaccination Uptake: A Study on Influenza Vaccination in a Population-Based Sample. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11). [CrossRef]

- Duradoni, M., Baroni, M., Colombini, G., Gori, N., Della Maggiora, N., Saviozzi, V., Macrì, E., Zanobini, P., Materassi, L., Guazzini, A. (2025) Development and Validation of the Vaccine Unawareness Scale (VUS): A New Measure for Vaccine Unawareness – in review.

- Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 38–48. [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J. O., Redding, C. A., & Evers, K. E. (2015). The transtheoretical model and stages of change. (In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. “V.” Viswanath). Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 125–148.

- Manoharan, B., Stennett, R., de Souza, R. J., Bangdiwala, S. I., Desai, D., Kandasamy, S., Khan, F., Khan, Z., Lear, S. A., Loh, L., Nocos, R., Schulze, K. M., Wahi, G., & Anand, S. S. (2024). Sociodemographic factors associated with vaccine hesitancy in the South Asian community in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique. [CrossRef]

- Wood, L., Smith, M., Miller, C. B., & O’Carroll, R. E. (2019). The Internal Consistency and Validity of the Vaccination Attitudes Examination Scale: A Replication Study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 53(1), 109–114. [CrossRef]

- Keisala, J., Jarva, E., Comparcini, D., Simonetti, V., Cicolini, G., Unsworth, J., Tomietto, M., & Mikkonen, K. (2024). Factors influencing nurses and nursing students’ attitudes towards vaccinations: A cross-sectional study. International journal of nursing studies, 162, 104963. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Martin, L. R., & Petrie, K. J. (2017). Understanding the Dimensions of Anti-Vaccination Attitudes: the Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) Scale. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 51(5), 652–660. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, F., Laganà, V., Pistininzi, R., Tarantino, F., Martin, L., & Servidio, R. (2023). Validation and psychometric properties of the Italian Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX-I) scale. Current Psychology, 42(25), 21287–21297. [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, V., & Lazić, M. (2023). Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) Scale: a Bifactor-ESEM approach in a youth sample (15-24 years). BMC Psychology, 11(1), 351. [CrossRef]

- Zanobini, P., Bonaccorsi, G., Giusti, M., Minardi, V., Possenti, V., Masocco, M., Garofalo, G., Mereu, G., Cecconi, R., & Lorini, C. (2023). Health literacy and breast cancer screening adherence: results from the population of Tuscany, Italy. Health Promotion International, 38(6). [CrossRef]

- Eisenblaetter, M., Madiouni, C., Laraki, Y., Capdevielle, D., & Raffard, S. (2023). Adaptation and Validation of a French Version of the Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) Scale. Vaccines, 11(5), 1001. [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhanunni, A., Pretorius, T. B., & Isaacs, S. A. (2023). Validation of the vaccination attitudes examination scale in a South African context in relation to the COVID-19 vaccine: quantifying dimensionality with bifactor indices. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1872. [CrossRef]

- Paredes, B., Cárdaba, M. Á., Cuesta, U., & Martinez, L. (2021). Validity of the Spanish Version of the Vaccination Attitudes Examination Scale. Vaccines, 9(11). [CrossRef]

- Espejo, B., Martín-Carbonell, M., Romero-Acosta, K. C., Fernández-Daza, M., & Paternina, Y. (2022). Evidence of Validity and Measurement Invariance by Gender of the Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) Scale in Colombian University Students. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(16), 4682. [CrossRef]

- Raffard, S., Bayard, S., Eisenblaetter, M., Attal, J., Andrieu, C., Chereau, I., Fond, G., Leignier, S., Mallet, J., Tattard, P., Urbach, M., Misdrahi, D., Laraki, Y., & Capdevielle, D. (2022). Attitudes towards Vaccines, Intent to Vaccinate and the Relationship with COVID-19 Vaccination Rates in Individuals with Schizophrenia. Vaccines, 10(8), 1228. [CrossRef]

- Ye, X., Lee, H.-H., Hui, K.-H., Xin, M., & Mo, P. K. H. (2023). Effects of Negative Attitudes towards Vaccination in General and Trust in Government on Uptake of a Booster Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine and the Moderating Role of Psychological Reactance: An Observational Prospective Cohort Study in Hong Kong. Vaccines, 11(2), 393. [CrossRef]

- Paul, E., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2021). Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications. The Lancet Regional Health. Europe, 1, 100012. [CrossRef]

- Biella, M., Orrù, G., Ciacchini, R., Conversano, C., Marazziti, D., & Gemignani, A. (2023). Anti-Vaccination Attitude and Vaccination Intentions Against Covid-19: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study Investigating the Role of Media Consumption. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 20(4), 252–263. [CrossRef]

- Siena, L. M., Isonne, C., Sciurti, A., de Blasiis, M. R., Migliara, G., Marzuillo, C., de Vito, C., Villari, P., & Baccolini, V. (2022). The Association of Health Literacy with Intention to Vaccinate and Vaccination Status: A Systematic Review. Vaccines, 10(11). [CrossRef]

- Biasio, L. R. (2019). Vaccine literacy is undervalued. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 15(11), 2552–2553. [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2, Pt.2), 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, U., Karter, A. J., Liu, J. Y., Adler, N. E., Nguyen, R., López, A., & Schillinger, D. (2010). The Literacy Divide: Health Literacy and the Use of an Internet-Based Patient Portal in an Integrated Health System—Results from the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Journal of Health Communication, 15(sup2), 183–196. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.-I., Yu, W.-R., & Lee, S.-Y. D. (2018). Is health literacy associated with greater medical care trust? International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 30(7), 514–519. [CrossRef]

- Miller, T. A. (2016). Health literacy and adherence to medical treatment in chronic and acute illness: A meta-analysis. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(7), 1079–1086. [CrossRef]

- Brezis M. (2008) Big Pharma and health care: Unsolvable conflict of interests between private enterprise and public health. The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences 45(2): 83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

- Dănescu, T., & Popa, M. A. (2020). Public health and corporate social responsibility: exploratory study on pharmaceutical companies in an emerging market. Globalization and health, 16(1), 117. [CrossRef]

- Lorini, C., del Riccio, M., Zanobini, P., Biasio, R. L., Bonanni, P., Giorgetti, D., Ferro, V. A., Guazzini, A., Maghrebi, O., Lastrucci, V., Rigon, L., Okan, O., Sørensen, K., & Bonaccorsi, G. (2023). Vaccination as a social practice: towards a definition of personal, community, population, and organizational vaccine literacy. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1501. [CrossRef]

- Biasio, Luigi & Zanobini, Patrizio & Lorini, Chiara & Bonaccorsi, Guglielmo. (2024). Perspectives in the Development of Tools to Assess Vaccine Literacy. Vaccines. 12. 422. [CrossRef]

- Isonne, C., Iera, J., Sciurti, A., Renzi, E., De Blasiis, M. R., Marzuillo, C., Villari, P., & Baccolini, V. (2024). How well does vaccine literacy predict intention to vaccinate and vaccination status? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 20(1), 2300848. [CrossRef]

- Brun, C., Akinyemi, A., Houtin, L., Zerhouni, O., Monvoisin, R., & Pinsault, N. (2022). Intolerance of Uncertainty and Attitudes towards Vaccination Impact Vaccinal Decision While Perceived Uncertainty Does Not. Vaccines, 10(10). [CrossRef]

| Gender | Age | Region | Educational qualification | Annual Income | HL | ||||||||||||||

| [M±SD] | Male | Female | Other | 18-35 | 36-64 | 65-70 | North | center | south | low | average | high | low | average | high | inadequate | problematic | adequate | |

| VAX-I | (N=124) | (N=498) | (N=15) | (N=556) | (N=71) | (N=10) | (N=170) | (N=364) | (N=103) | (N=9) | (N=328) | (N=300) | (N=283) | (N=265) | (N=89) | (N=64) | (N=191) | (N=334) | |

| total scale | 32.11±12.71 | 32.41±14.68 | 31.99±12.10 | 33.33±15.53 | 30.70±11.09 | 41.80±17.41 | 41.6±22.52 | 32.35±14.17 | 31.53±11.79 | 33.72±13.26 | 34.11±16.55 | 31.87±12.68 | 32.31±12.65 | 31.33±12.06 | 32.31±12.86 | 33.95±14.12 | 37.31±14.30 | 33.01±12.15 | 30.31±12.28 |

| F1 | 7.14±3.49 | 7.20±4.09 | 7.11±3.33 | 7.66±3.69 | 6.86±3.09 | 9±5.01 | 9.6±6.36 | 7.45±4.02 | 6.89±3.23 | 7.52±3.41 | 8.22±4.26 | 7.14±3.46 | 7.12±3.52 | 7.12±3.45 | 7.03±3.45 | 7.55±3.74 | 8.46±4.33 | 7.41±3.47 | 6.70±3.21 |

| F2 | 10.61±3.62 | 10.02±3.87 | 10.75±3.55 | 10.6±3.69 | 10.29±3.43 | 12.87±4.01 | 12.3±5.45 | 10.31±3.8 | 10.62±3.58 | 11.06±3.45 | 11±4.03 | 10.63±3.73 | 10.57±3.51 | 10.44±3.63 | 10.71±3.52 | 10.83±3.91 | 11.57±3.64 | 10.73±3.54 | 10.25±3.64 |

| F3 | 6.42±3.84 | 6.79±4.34 | 6.30±3.69 | 7.06±4.51 | 5.99±3.35 | 9.43±5.33 | 8.8±6.52 | 6.59±4.06 | 6.22±3.53 | 6.82±4.49 | 7±4.63 | 6.27±3.80 | 6.56±3.87 | 6.05±3.44 | 6.58±3.96 | 7.07±4.56 | 8±4.35 | 6.73±3.79 | 5.88±3.64 |

| F4 | 7.93±3.83 | 8.38±4.33 | 7.81±3.66 | 8±4.82 | 7.55±3.50 | 10.49±4.92 | 10.9±5.02 | 8±4.22 | 7.79±3.61 | 8.31±3.93 | 7.88±4.78 | 7.82±3.73 | 8.05±3.92 | 7.71±3.61 | 7.97±3.89 | 8.49±4.28 | 9.26±4.20 | 8.13±3.69 | 7.48±3.78 |

| V.U. | 9.93±3.38 | 10.64±3.45 | 9.78±3.36 | 8.8±2.21 | 10.06±3.33 | 8.85±3.43 | 10.3±4.47 | 9.70±3.58 | 9.85±3.23 | 10.58±3.49 | 9.33±3.31 | 10.07±3.34 | 9.79±3.42 | 10.39±3.27 | 9.58±3.47 | 9.48±3.26 | 11.95±4.01 | 10.07±3.24 | 9.29±3.13 |

| N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) | |||||

| (HL) inadequate | - | 10 (9.01%) | 52 (11.21%) | 2 (14.29%) | 56 (10.89%) | 8 (12.12%) | 0 (0.00%) | 18 (11.46%) | 36 (10.62%) | 10 (10.75%) | 0 (0.00%) | 30 (9.97%) | 34 (12.19%) | 29 (11.46%) | 25 (10.00%) | 10 (11.63%) | - | - | - |

| (HL) problematic | - | 41 (36.94%) | 148 (31.90%) | 2 (14.29%) | 166 (32.30%) | 24 (36.36%) | 1 (11.11%) | 46 (29.30%) | 120 (35.40%) | 25 (26.88%) | 4 (44.44%) | 107 (35.55%) | 80 (28.67%) | 86 (33.99%) | 79 (31.60%) | 26 (30.23%) | - | - | - |

| (HL) adequate | - | 60 (54.05%) | 264 (56.90%) | 10 (71.43%) | 292 (56.81%) | 34 (51.52%) | 8 (88.89%) | 93 (59.24%) | 183 (53.98%) | 58 (62.37%) | 5 (55.56%) | 164 (54.49%) | 165 (59.14%) | 138 (54.55%) | 146 (58.40%) | 50 (28.14%) | - | - | - |

| HL | |||||||

| HL inadequate | HL problematic | HL adequate | F | p | R² | ||

| VAX-I | [M±SD] | (N=64) | (N=191) | (N=334) | |||

| total scale | [32.11±12.71] | [37.31±14.30] | [33.01±12.15] | [30.31±12.28] | 9.48 | 0.0001 | 0.0313 |

| F1 | [7.14±3.49] | [8.46±4.33] | [7.41±3.47] | [6.70±3.21] | 8.15 | 0.0003 | 0.0271 |

| F2 | [10.61±3.62] | [11.57±3.64] | [10.73±3.54] | [10.25±3.64] | 3.98 | 0.0192 | 0.0134 |

| F3 | [6.42±3.84] | [8±4.35] | [6.73±3.79] | [5.88±3.64] | 9.64 | 0.0001 | 0.0319 |

| F4 | [7.93±3.83] | [9.26±4.20] | [8.13±3.69] | [7.48±3.78] | 6.50 | 0.0016 | 0.0217 |

| V.U. | [9.93±3.38] | [11.95±4.01] | [10.07±3.24] | [9.29±3.13] | 18.46 | 0.0001 | 0.0593 |

| Vaccine Unawareness | VAX-I | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |||||||||||||

| β | p | 95% CI | β | p | 95% CI | β | P | 95% CI | β | p | 95% CI | β | p | 95% CI | β | p | 95% CI | |

| constant | 13.22 | <0.001 | [-10.752 15.705] | 17.78 | <0.001 | [8.053 27.511] | 4.46 | 0.001 | [1.743 7.182] | 6.05 | <0.001 | [3.182 8.925] | 3.01 | 0.047 | [0.041 5.992] | 4.24 | 0.006 | [1.215 7.280] |

| vaccine unawareness | - | - | - | 0.95 | <0.001 | [0.656 1.246] | 0.28 | <0.001 | [0.200 0.365] | 0.18 | <0.001 | [-0.094 0.268] | 0.24 | <0.001 | [0.159 0.339] | 0.23 | <0.001 | [0.145 0.329] |

| problematic1 | -1.95 | <0.001 | [-2.878 -1.035] | -2.29 | 0.180 | [-5.666 1.068] | -0.46 | 0.327 | [-1.411 0.471] | -0.44 | 0.380 | [-1.438 0.549] | -0.74 | 0.158 | [-1.771 0.288] | -0.64 | 0.229 | [-1.692 0 .406] |

| adequate1 | -2.71 | <0.001 | [-3.580 -1.841] | -4.37 | 0.008 | [-7.603 -1.142] | -1.01 | 0.028 | [-1.914 -0.108] | -0.79 | 0.101 | [-1.749 0.157] | -1.42 | 0.005 | [-2.414 -0.438] | -1.13 | 0.027 | [-2.144 -0.131] |

| cis. Females2 | -0.89 | 0.011 | [-1.572 -0.207] | 2.04 | 0.104 | [-0.421 4.518] | 0.42 | 0.232 | [-0.270 1.110] | 1.51 | <0.001 | [0.781 2.239] | 0.15 | 0.692 | [-0.603 0.907] | -0.03 | 0.929 | [-0.805 0.734] |

| other2 | -1.91 | 0.038 | [-3.727 -0.102] | 5.38 | 0.107 | [-1.164 11.931] | 1.42 | 0.128 | [-0.408 3.252] | 1.81 | 0.065 | [-0.114 3.750] | 1.40 | 0.167 | [-0.593 3.412] | 0.733 | 0.480 | [-1.307 2.774] |

| 35-643 | -1.28 | 0.004 | [-2.168 -0.401] | 12.44 | <0.001 | [9.238 15.642] | 2.43 | <0.001 | [1.536 3.327] | 3.25 | <0.001 | [2.305 4.195] | 3.58 | <0.001 | [2.609 4.568] | 3.16 | <0.001 | [2.17 4.166] |

| 65-703 | -0.047 | 0.966 | [-2.24 2.14] | 9.83 | 0.015 | [1.937 17.730] | 2.29 | 0.041 | [0.092 4.506] | 2.40 | 0.043 | [0.077 4.738] | 2.18 | 0.076 | [-0.232 4.598] | 2.94 | 0.019 | [0.48 5.404] |

| center4 | 0.19 | 0.554 | [-0.443 0.826] | -0.77 | 0.508 | [-3.058 1.516] | -0.59 | 0.068 | [-1.233 0.045] | 0.374 | 0.276 | [-0.300 1.050] | -0.26 | 0.456 | [-0.965 0.433] | -0.28 | 0.431 | [-0.999 0.426] |

| south4 | 0.74 | 0.082 | [-0.095 1.579] | 1.60 | 0.296 | [-1.413 4.631] | 0.12 | 0.780 | [-0.724 0.965] | 0.92 | 0.043 | [0.030 1.814] | 0.29 | 0.531 | [-0.629 1.219] | 0.27 | 0.572 | [-0.670 1.213] |

| average5 | -0.30 | 0.793 | [-2.54 1.94] | 5.27 | 0.201 | [-2.810 13.352] | 0.482 | 0.675 | [-1.777 2.741] | 1.52 | 0.211 | [-0.864 3.905] | 1.36 | 0.279 | [-1.109 3.834] | 1.90 | 0.138 | [-0.614 4.424] |

| high5 | -0.32 | 0.773 | [-2.55 1.90] | 3.84 | 0.348 | [-4.194 11.876] | 0.04 | 0.972 | [-2.205 2.286] | 1.03 | 0.390 | [-1.333 3.409] | 1.10 | 0.377 | [-1.350 3.564] | 1.65 | 0.195 | [-0.849 4.160] |

| average6 | -0.39 | 0.183 | [-.988 0.189] | 0.25 | 0.817 | [-1.871 2.373] | -0.18 | 0.539 | [-0.778 0.407] | 0.034 | 0.913 | [-0.591 0.661] | 0.31 | 0.334 | [-.329 0.968] | 0.08 | 0.808 | [-0.579 0.743] |

| high6 | -0.54 | 0.189 | [-1.36 0.268] | 2.18 | 0.144 | [-0.747 5.126] | 0.49 | 0.241 | [-0.330 1.311] | 0.18 | 0.674 | [-0.681 1.052] | 0.85 | 0.062 | [-0.042 1.753] | 0.65 | 0.158 | [-0.257 1.573] |

| R²= 0.098 | R²= 0.173 | R²= 0.143 | R²= 0.124 | R²= 0.156 | R²= 0.126 | |||||||||||||

| F(12, 576)= 5.27 | F(13, 575)= 9.29 | F(13, 575)= 7.41 | F(13, 575)= 6.31 | F(13, 575)= 8.23 | F(13, 575)= 6.39 | |||||||||||||

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||||||||||||

| VAX-I | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | ||||||||||||

| β | p | 95% CI | β | p | 95% CI | β | p | 95% CI | β | p | 95% CI | β | p | 95% CI | ||

| [problematic vs inadequate] | NIE | -0.56 | 0.294 | [-1.633 0.493] | -0.06 | 0.692 | [-.359 0.238] | -0.31 | 0.081 | [-0.668 0.039] | -0.06 | 0.699 | [-0.392 0.263] | -0.129 | 0.424 | [-0.447 0.188] |

| NDE | -3.61 | 0.061 | [-7.395 0.161] | -0.97 | 0.096 | [-2.117 0.173] | -0.48 | 0.326 | [-1.463 0.486] | -1.17 | 0.051 | [-2.354 0.005] | -0.98 | 0.096 | [-2.137 0.173] | |

| TE | -4.18 | 0.031 | [-7.986 -0.387] | -1.03 | 0.076 | [-2.174 0.108] | -0.80 | 0.107 | [-1.779 0.172] | -1.23 | 0.040 | [-2.421 -0.056 | -1.11 | 0.056 | [-2.252 0.029] | |

| [adequate vs inadequate] | NIE | -3.07 | <0.001 | [-4.739 -1.406] | -0.96 | <0.001 | [-1.439 -0.48] | -0.44 | 0.034 | [-0.862 -0.0.34] | -0.83 | <0.001 | [-1.307 -0.353] | -0.83 | <0.001 | [-1.298 -0.367] |

| NDE | -3.89 | 0.031 | [-7.445 -0.352] | -0.82 | 0.120 | [-1.862 0.214] | -0.84 | 0.089 | [-1.816 0.127] | -1.28 | 0.024 | [-2.392 -0.168] | -0.94 | 0.092 | [-2.053 0.154] | |

| TE | -6.97 | <0.001 | [-10.579 -3.363] | -1.78 | 0.001 | [-2.868 -0.702] | -1.29 | 0.006 | [-2.212 -0.373] | -2.11 | <0.001 | [-3.223 -0.998] | -1.78 | <0.001 | [-2.872 -0.693] | |

| [Outcome: VAX-I total scale, mediator: V.U., predictor: HL] | [Outcome: F1, mediator: V.U., predictor: HL] | [Outcome: F2, mediator: V.U., predictor: HL] | [Outcome: F3, mediator: V.U., predictor: HL] | [Outcome: F4, mediator: V.U., predictor: HL] | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).