Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- proposes a customized remediation framework to meet the heterogeneous needs of embedded systems, designs a four-step remediation process (vulnerability identification, vulnerability localization, patch preparation, and patch switching) tailored to the characteristics of embedded devices, and enhances the detection-based hotfixing approach to avoid relying on the binary detection and other software layers, and improves the accuracy and adaptability of the patches.

- In order to solve the service interruption problem caused by static patching, the framework proposes a hot-patching-based vulnerability remediation method for embedded devices, which utilizes the hardware built-in function to execute hot patches, avoiding device downtime and system restart, and guaranteeing system continuity in mission-critical scenarios.

- In order to overcome the high overhead of dynamic patching, the framework uses on-board debugging units to dynamically replace instructions at runtime, which greatly reduces resource consumption during the repair process while maintaining the real-time nature of the system.

- The experimental results show that the hot-patch-based vulnerability repair method proposed in this paper performs well in embedded device vulnerability repair, effectively reduces system downtime and service interruption, and provides strong support for system stability and availability. Through in-depth analysis and optimization, this paper provides an innovative and efficient solution for security maintenance of embedded devices, which has important theoretical significance and practical value.

2. Related Works

3. Methodology

3.1. Vulnerability Identification

3.2. Vulnerability Localization

3.3. Patch Preparation

3.4. Patch Switching

3.4.1. Debugging Unit FPB Configuration

- The fpb_Init function is responsible for initializing the FPB unit, ensuring that the FPB unit has been loaded correctly, and preparing for subsequent task scheduling and priority management;

- The fpb_enable function is used to set the FPB unit to be enabled and disabled; if not set, the device will ignore any breakpoints that have been configured and enabled;

- The enable_single_patch function utilizes code remapping and breakpoints to enable the creation of jump instructions for control flow redirection. The jump instructions can be provided directly by the patch or generated by calculating to get the specified offset. The function sets the breakpoint at the insertion location of the jump instruction and sets the breakpoint behavior to code remapping. Atomic switches are implemented to enable hot patching by writing in a single register;

- The load_patch_and_dispatcher function is responsible for patch loading and preparation, and the basic scheduler copies the patch into RAM by loading and modifying it according to the given patch location.

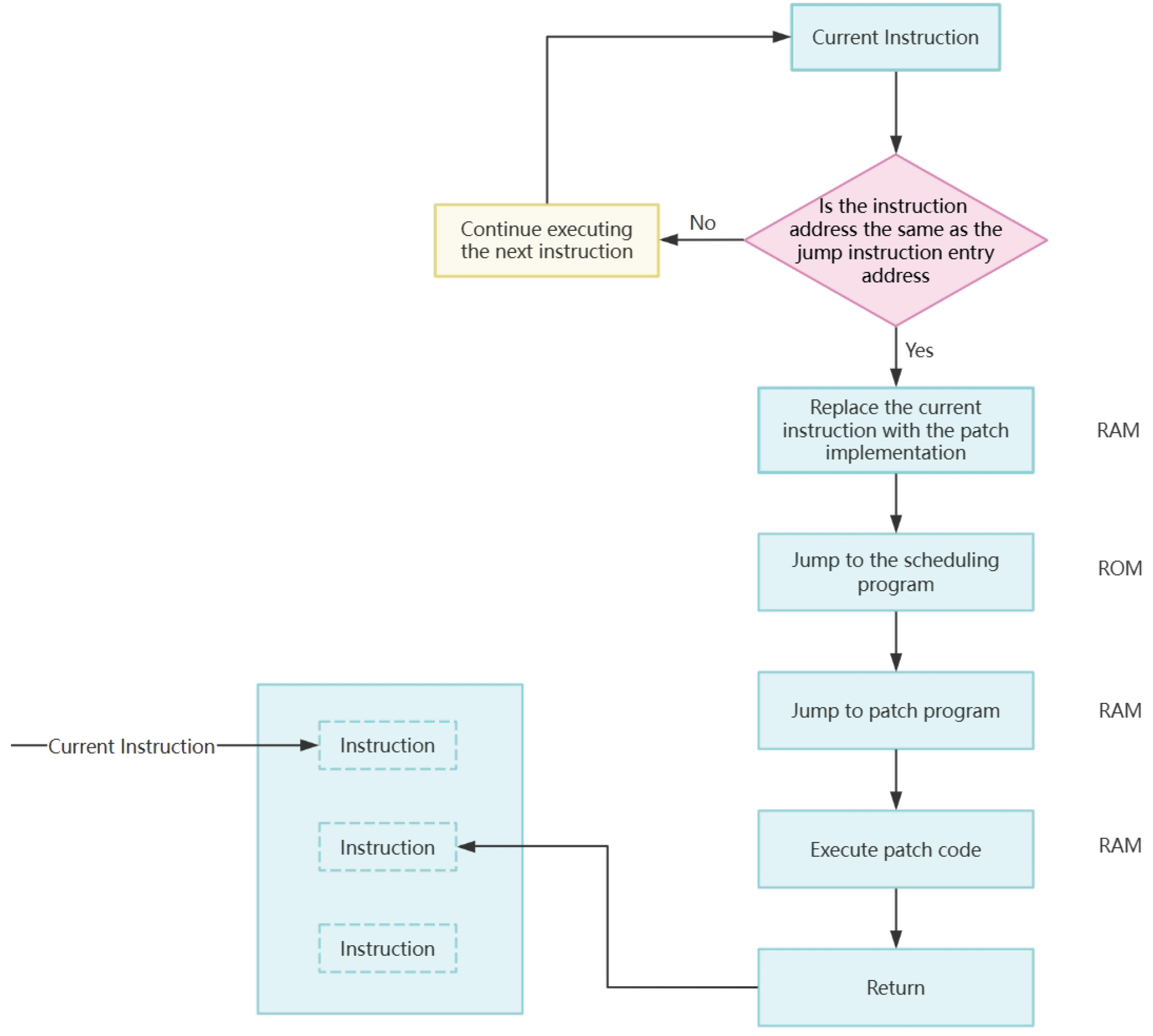

3.4.2. Add Patch Tasks to the Scheduler and Configure Jump Instructions

3.4.3. The Update Program Notifies the Hardware to Activate the Patch Through Atomic Instructions

3.4.4. Monitor the Instructions Executed by the CPU

3.4.5. Jump to Patch Code by Jump Instruction

3.4.6. Execute Patch Code

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Environment

4.2. Data Sets

4.3. Experiment and Result Analysis

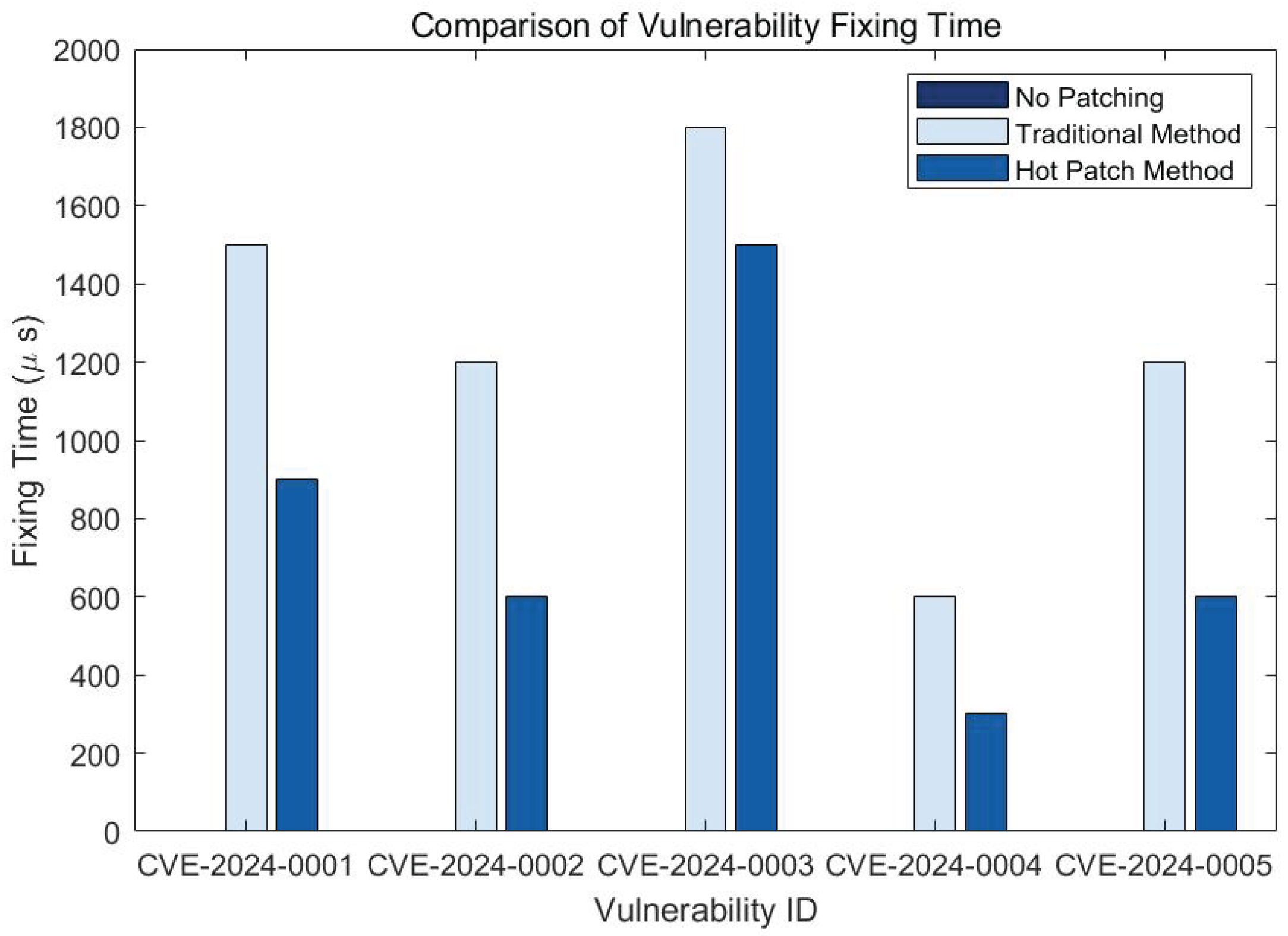

4.3.1. Vulnerability Fixing Time Comparison Experiment and Result Analysis

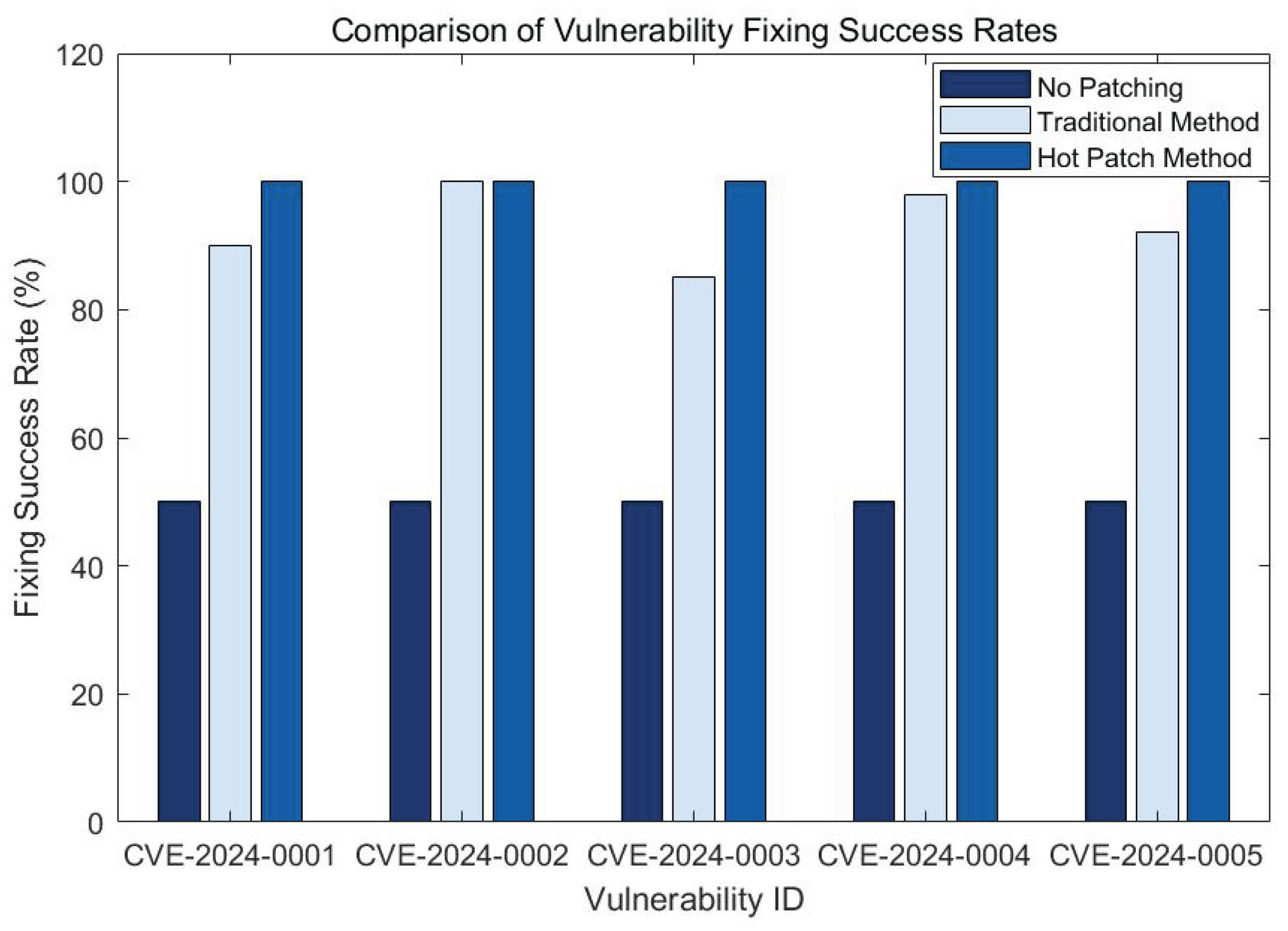

4.3.2. Vulnerability Repair Success Rate Comparison Experiment and Result Analysis

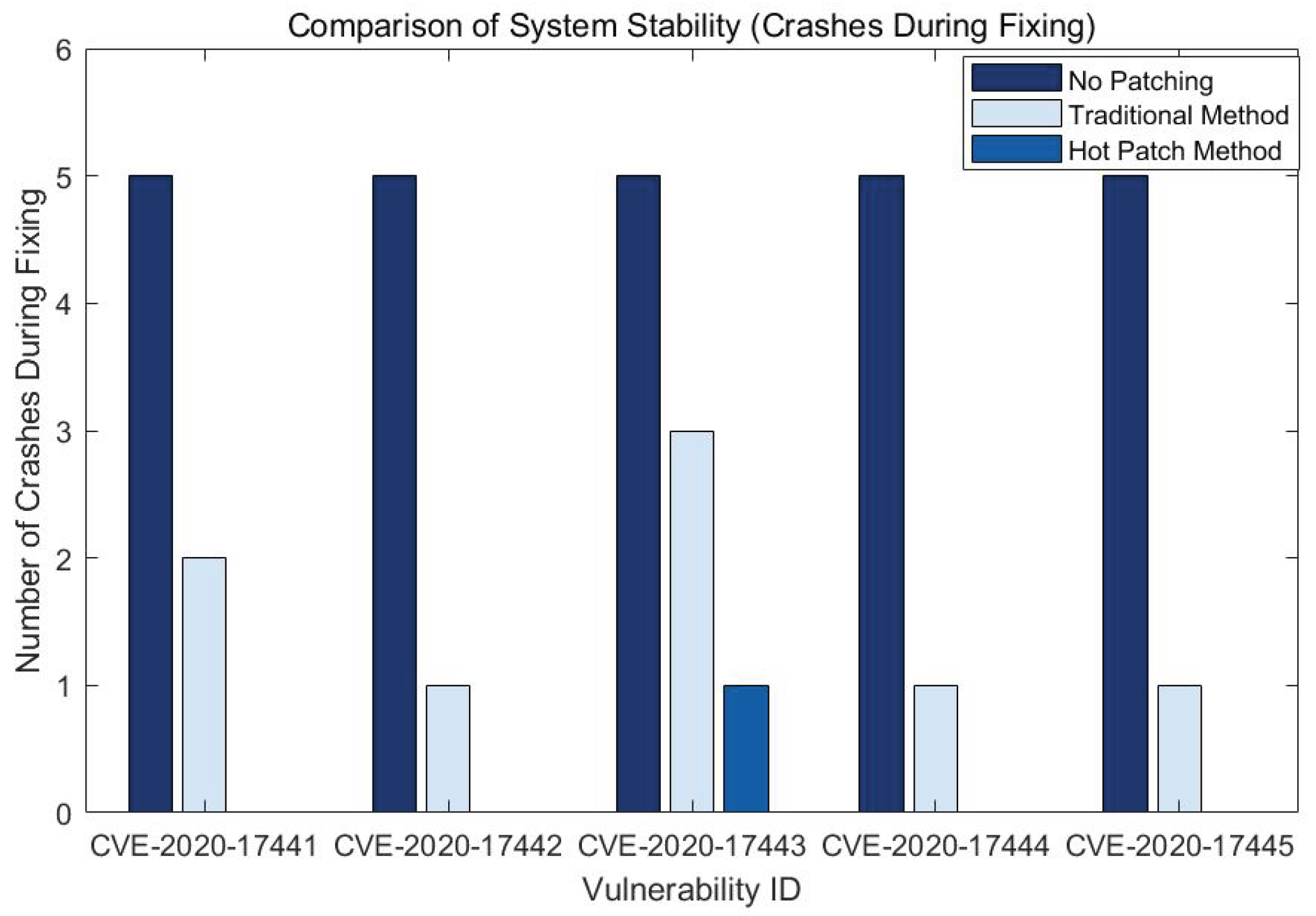

4.3.3. System Stability Comparison Experiment and Result Analysis

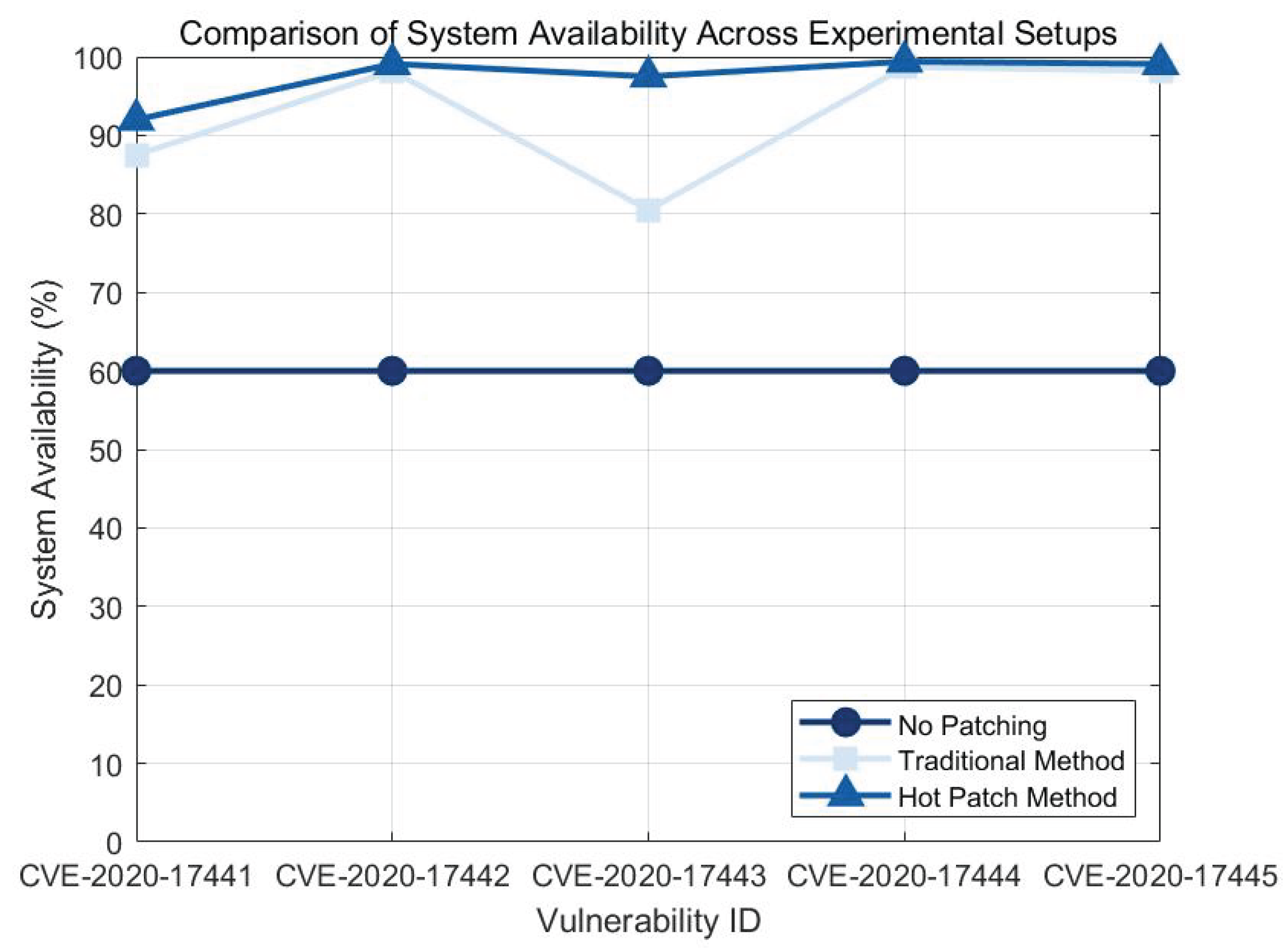

4.3.4. System Usability Comparison Experiment and Result Analysis

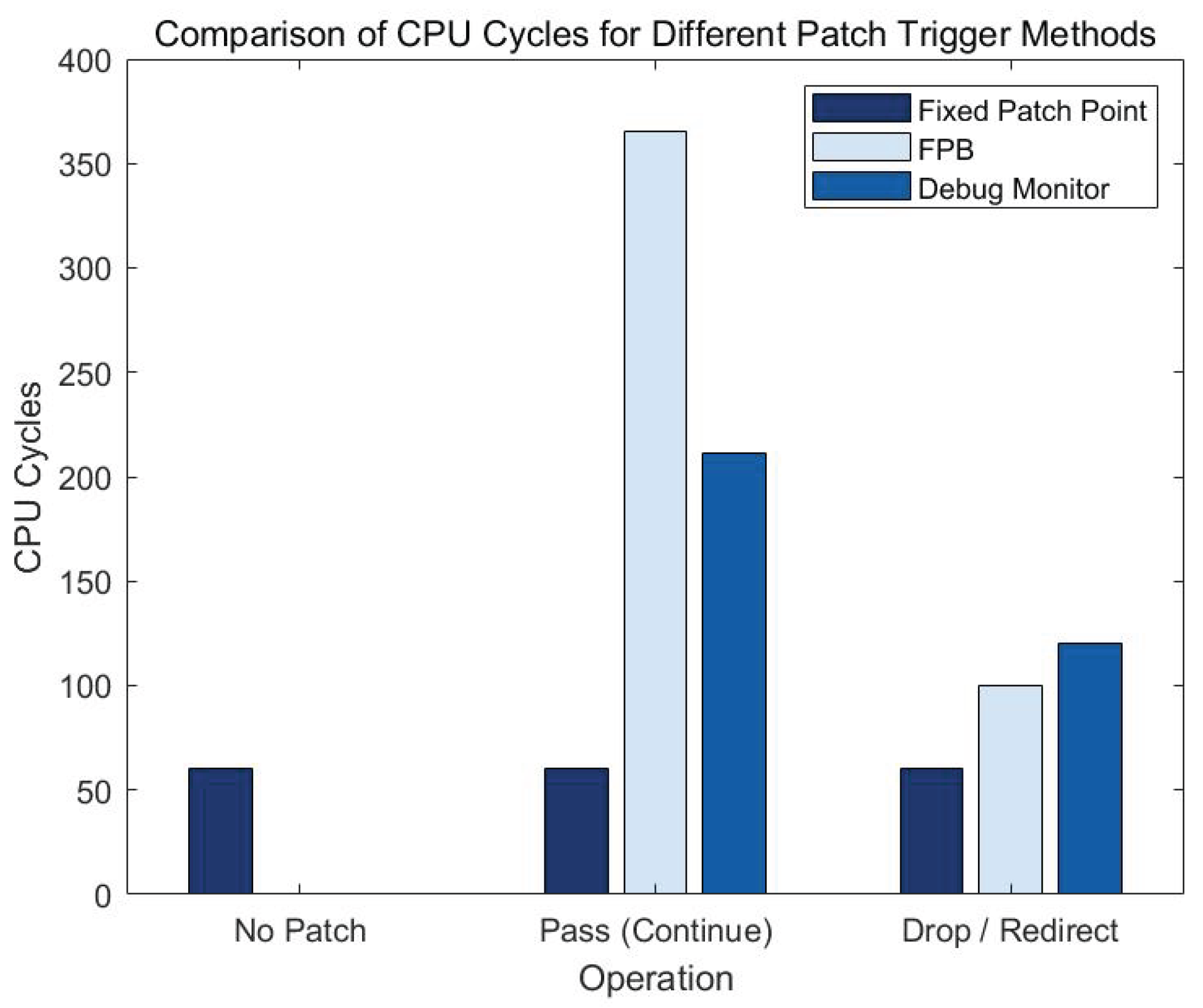

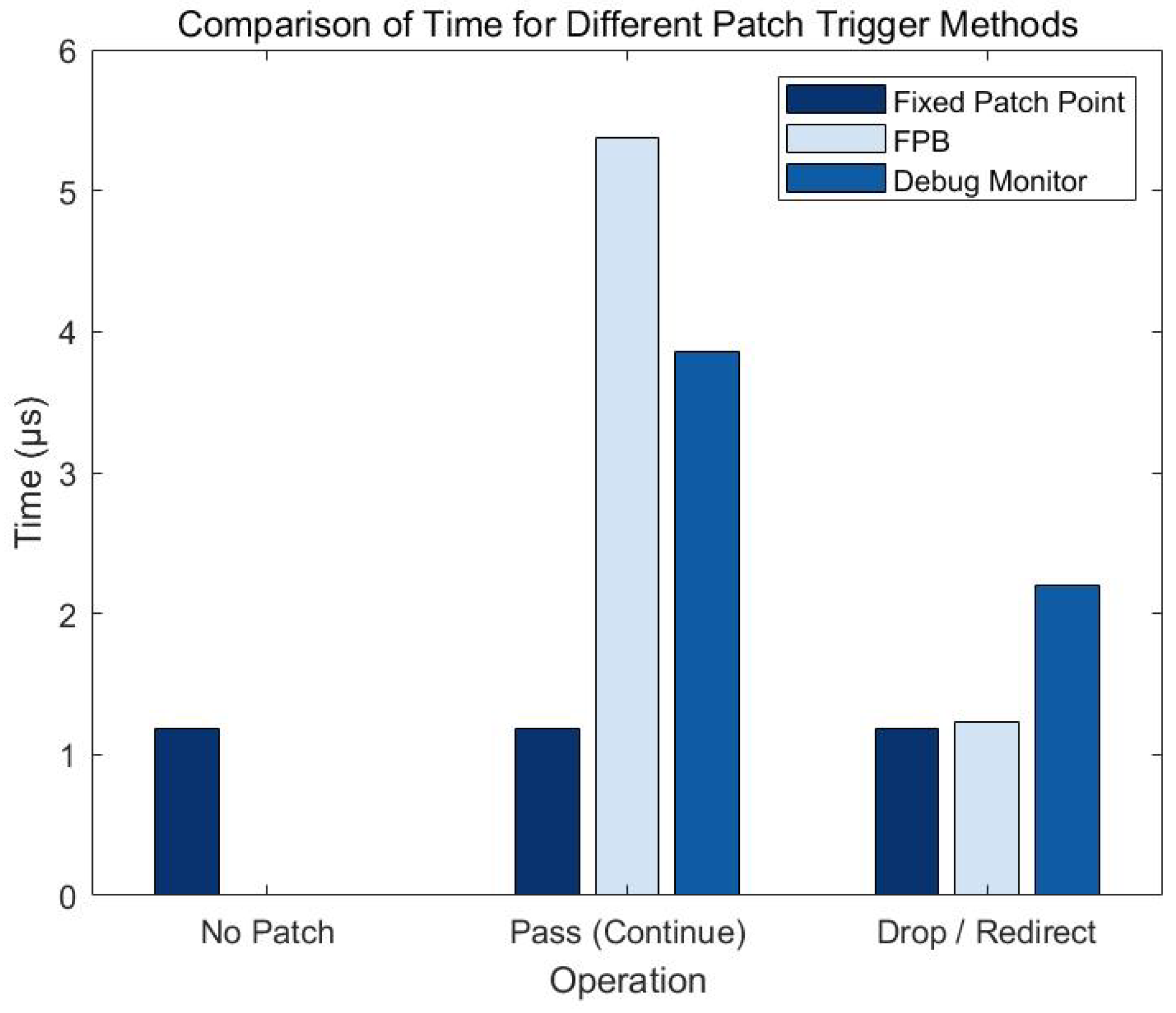

4.3.5. Experiment and Result Analysis of Time and CPU Cycle Required for Different Patch Triggering Methods

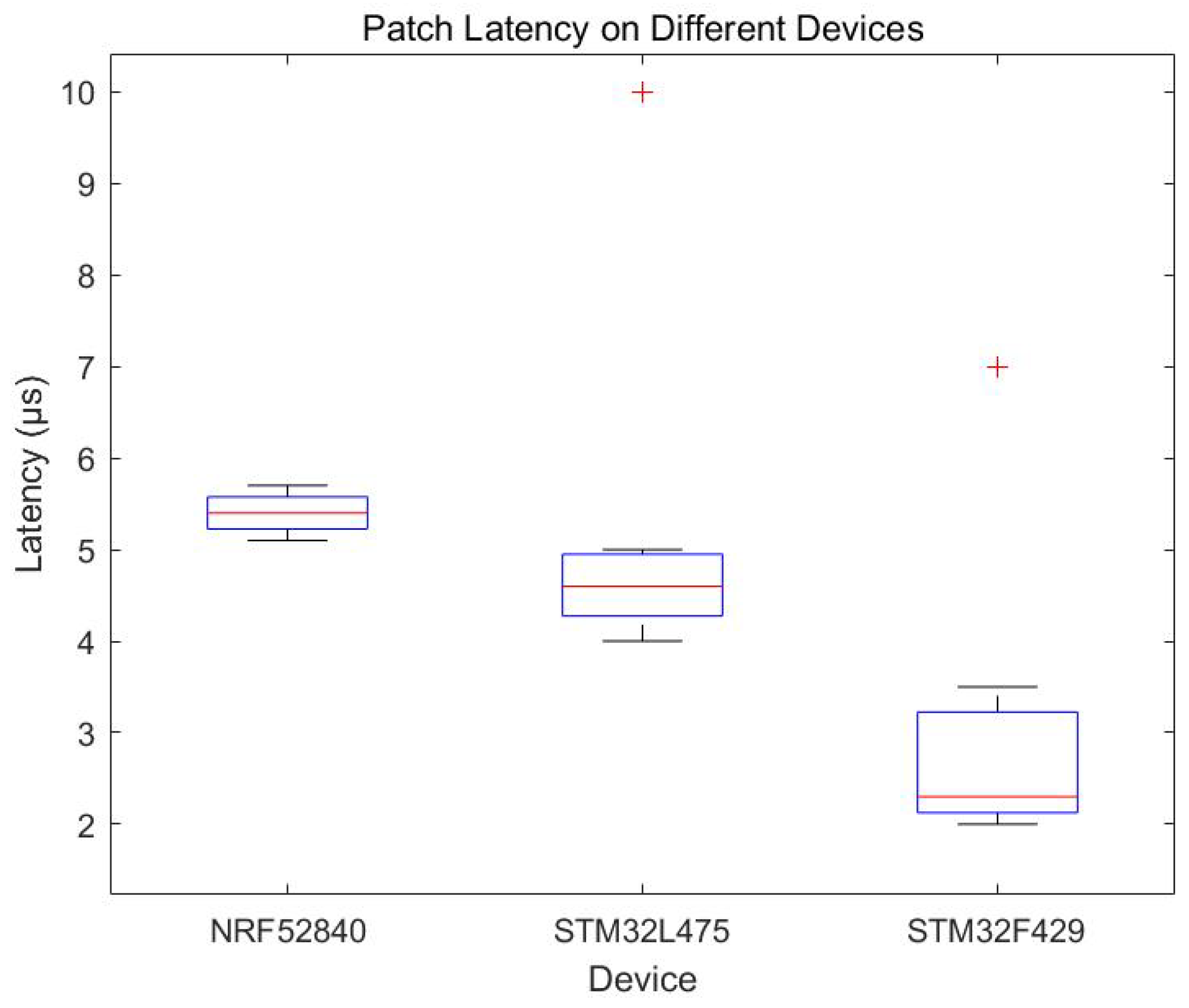

4.3.6. Patch Delay Experiments with Different Devices and Analysis of Results

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Niesler C, Surminski S, Davi L. HERA: Hotpatching of Embedded Real-time Applications. In: Proc. Network and Distributed Systems Security (NDSS) Symp. 2021. p. 21–25. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Wang X, Hao Q, Xu D, Wang J, Liu J, Ma J, Zhang J. Hardware-Implemented Security Processing Unit for Program Execution Monitoring and Instruction Fault Self-Repairing on Embedded Systems[J]. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(7): 3584.

- Li Z, Liu M, Wang P, Su W, Chang T, Chen X, Zhou X. Multi-ARCL: Multimodal Adaptive Relay-Based Distributed Continual Learning for Encrypted Traffic Classification[J]. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing, 2025, 201: 105083.

- Ye H, Gu J, Martinez M, et al. Automated classification of overfitting patches with statically extracted code features. IEEE Trans. Software Eng. 2021;48(8):2920–2938. [CrossRef]

- Xiong Y F, Liu X Y, Zeng M H, et al. Identifying patch correctness in test-based program repair. In: Proc. 40th Int. Conf. Software Eng. ACM: New York, 2018. p. 789–799. [CrossRef]

- Jiang W, Liu L. Research on hot-patching technology based on VXWORKS system. Comput. Technol. Dev. 2017;27(03):18–22+28.

- Zhou M, Wang H, Li K, et al. Save the Bruised Striver: A Reliable Live Patching Framework for Protecting Real-World PLCs. In: Proc. 19th Eur. Conf. Comput. Syst. 2024. p. 1192–1207. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Zou Z, Sun K, Liu Z, Xu K, Wang Q, Shen C, Wang Z, Li Q. RapidPatch: Firmware Hotpatching for Real-Time Embedded Devices. In: Proc. USENIX Security Symp. 2022. p. 10–12.

- Wang M. Exploration and application of remote hot deployment based on SpringBoot. Inf. Comput. (Theor. Ed.). 2023;35(07):1–4. [CrossRef]

- Holmbacka S, et al. Lightweight Framework for Runtime Updating of C-Based Software in Embedded Systems. In: Workshop on Hot Topics in Software Upgrades. 2013.

- Ramaswamy A, Bratus S, et al. Katana: A Hot Patching Framework for ELF Executables. In: Proc. ARES 2010. p. 507–512. [CrossRef]

- Payer M, et al. DynSec: On-the-fly Code Rewriting and Repair. In: Workshop on Hot Topics in Software Upgrades. 2013.

- Chen H, Chen R-X, et al. Live updating operating systems using virtualization. In: Proc. Int. Conf. Virtual Execution Environments. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Mao Y, Migliore V, Nicomette V. MATANA: A Reconfigurable Framework for Runtime Attack Detection Based on the Analysis of Microarchitectural Signals[J]. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(3): 1452.

- Zhu Z, Jin Z, Wang X, Zhang J, Chen H, Choo K K R. Rethinking Transferable Adversarial Attacks with Double Adversarial Neuron Attribution[J]. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, 2024.

- Altekar G, et al. OPUS: Online Patches and Updates for Security. In: Proc. USENIX Security Symp. 2005.

- Dong Y, et al. Towards the Detection of Inconsistencies in Public Security Vulnerability Reports. In: Proc. USENIX Security Symp. 2019.

- Shi J, Wang Y, Su Y, et al. Analysis of MQX interrupt mechanism and interrupt program framework design based on ARM Cortex-M4. Comput. Sci. 2013;40(06):41–44+79. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Ling X, Wang Y. Design of a generic framework for assembly engineering for ARM Cortex-M series cores. Small Microcomput. Syst. 2021;42(11):2440–2445.

- Zhou C. Design and Implementation of Server/Client Based Patch Management System. Microcomput. Appl. 2009;30(06):53–57.

- Li Z, Wang P, Wang Z, et al. Flowganomaly: Flow-based anomaly network intrusion detection with adversarial learning. Chin. J. Electron. 2024;33(1):58–71.

- Wang Z X, Li Z Y, Fu M Y, et al. Network traffic classification based on federated semi-supervised learning. J. Syst. Archit. 2024;149:103091.

- Li Z, Zhang Z, Fu M, et al. A novel network flow feature scaling method based on cloud-edge collaboration. In: Proc. 2023 IEEE 22nd Int. Conf. Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom). IEEE: 2023. p. 1947–1953.

- Correa R, Bermejo Higuera J R, Higuera J B, et al. Hybrid security assessment methodology for web applications[J]. Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences, 2021, 126(1): 89–124.

- Naeem H, Alsirhani A, Alserhani F M, Ullah F, Krejcar O. Augmenting Internet of Medical Things Security: deep ensemble integration and methodological fusion[J]. Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences, 2024, 141(3): 2185–2223.

- Zhu Z, Chen H, Zhang J, Wang X, Jin Z, Xue M, Zhu D, Choo K K R. MFABA: A More Faithful and Accelerated Boundary-Based Attribution Method for Deep Neural Networks[C]. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, 38(15): 17228–17236.

| Categories | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware | Multiprocessor | Intel Core i7-10870H |

| GPUs | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 | |

| Random access memory (RAM) | 16GB DDR4 | |

| Software | Development and operating environments | Ubuntu 20.04 LTS |

| Integrated development environment (IDE) | Eclipse IDE 2021-09 | |

| programming language | C, C++ | |

| Debugging Tools | GDB 10.1 | |

| version control | Git 2.25.1 | |

| network tool | Wireshark 3.4.8 | |

| Traffic Tools | Scapy 2.4.5 | |

| virtualized environment | VMware Workstation Pro |

| Vulnerability ID | subassemblies | descriptive | (machine) filte |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-17441 | PicoTCP | Validate IPv6 payload length field against actual size for function pico_ipv6_process_in | Filter Patch |

| 2020-17442 | PicoTCP | Validate hop-by-hop IPv6 extension header length field for function pico_ipv6_process_hopbyhop | Filter Patch |

| 2020-17443 | PicoTCP | Restrict that echo->transport_len is no less than 8 in pico_icmp6_send_echoreply | Filter Patch |

| 2020-17444 | PicoTCP | Check possible overflow of header extension length field for pico_ipv6_check_headers_sequence | Filter Patch |

| 2020-17445 | PicoTCP | Validate optlen using a loop prior to function pico_ipv6_process_destopt | Filter Patch |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).