Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Global Economic Impact of Wheat and Yellow Rust

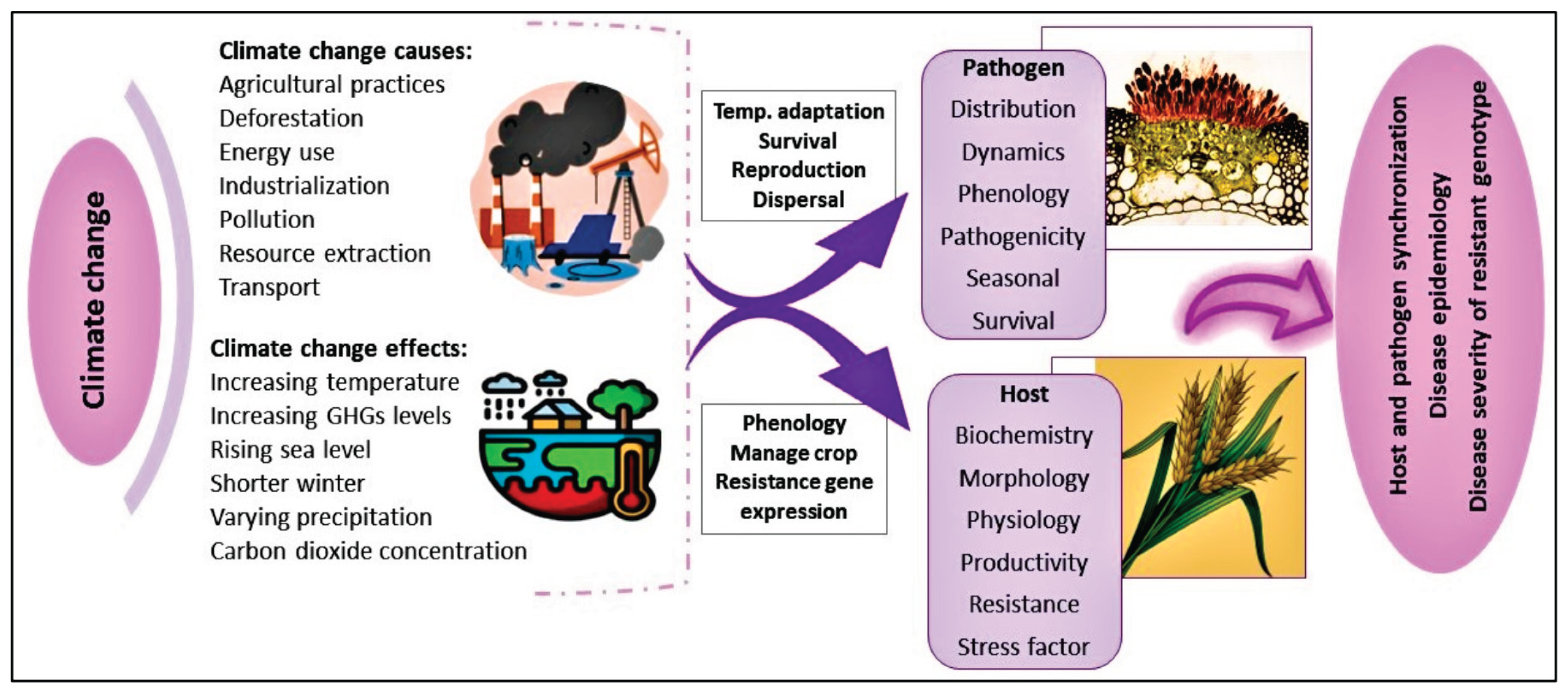

3. Climate Change and Wheat Yellow Rust

3.1. Emergence of High-Temperature-Adapted Pst Strains and Rust Expansion

3.2. Pathogen Survival, Reproduction, and Increased Aggressiveness

3.3. New Strains and Pathotypes

3.4. Regional Impact of Yellow Rust

3.5. Effects of Elevated GHGs and Abiotic Factors on Host-Pathogen Dynamics

4. Host Resistance as a Primary Control Strategy

5. Conclusion and Way Forward

References

- Abou-Zeid, M. A., & Mourad, A. M. (2021). Genomic regions associated with yellow rust resistance against the Egyptian race revealed by genome-wide association study. BMC Plant Biology, 21, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Abro, Z. A., Jaleta, M., & Qaim, M. (2017). Yield effects of rust-resistant wheat varieties in Ethiopia. Food security, 9(6), 1343-1357. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R., Kulshreshtha, D., Sharma, S., Singh, V. K., Manjunatha, C., Bhardwaj, S. C., & Saharan, M. S. (2018). Molecular characterization of Indian pathotypes of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici and multigene phylogenetic analysis to establish inter-and intraspecific relationships. Genetics and Molecular Biology, 41, 834-842.

- Ali, S., & Hodson, D. (2017). Wheat rust surveillance: field disease scoring and sample collection for phenotyping and molecular genotyping. Wheat Rust Diseases: Methods and Protocols, 3-11.

- Ali, S., Gladieux, P., Leconte, M., Gautier, A., Justesen, A. F., Hovmøller, M. S., & de Vallavieille-Pope, C. (2014). Origin, migration routes and worldwide population genetic structure of the wheat yellow rust pathogen Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. PLoS pathogens, 10(1), e1003903. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., Rodriguez-Algaba, J., Thach, T., Sørensen, C. K., Hansen, J. G., Lassen, P., & Hovmøller, M. S. (2017). Yellow rust epidemics worldwide were caused by pathogen races from divergent genetic lineages. Frontiers in Plant Science, 8, 1057. [CrossRef]

- Anand, S., Sandhu, S. K., & Tak, P. S. (2023). Effect of abiotic factors on pathotypes causing yellow and brown rust in wheat. Journal of Agrometeorology, 25(3), 462-465. [CrossRef]

- Andrivon, D., Pilet, F., Montarry, J., Hafidi, M., Corbière, R., Achbani, E. H., & Ellisseche, D. (2007). Adaptation of Phytophthora infestans to partial resistance in potato: evidence from French and Moroccan populations. Phytopathology, 97(3), 338-343.

- Anonymous (2019) Rust Watch Report 34 PP.

- Asseng, S., Foster, I. A. N., & Turner, N. C. (2011). The impact of temperature variability on wheat yields. Global change biology, 17(2), 997-1012. [CrossRef]

- Azzimonti, G., Lannou, C., Sache, I., & Goyeau, H. (2013). Components of quantitative resistance to leaf rust in wheat cultivars: diversity, variability and specificity. Plant Pathology, 62(5), 970-981. [CrossRef]

- Bahri, B., Leconte, M., Ouffroukh, A., DE VALLAVIEILLE-POPE, C., & Enjalbert, J. (2009). Geographic limits of a clonal population of wheat yellow rust in the Mediterranean region. Molecular Ecology, 18(20), 4165-4179. [CrossRef]

- Bariana, H., Kant, L., Qureshi, N., Forrest, K., Miah, H., & Bansal, U. (2022). Identification and characterisation of yellow rust resistance genes Yr66 and Yr67 in wheat cultivar VL Gehun 892. Agronomy, 12(2), 318.

- Beddow, J. M., Pardey, P. G., Chai, Y., Hurley, T. M., Kriticos, D. J., Braun, H. J., & Yonow, T. (2015). Research investment implications of shifts in the global geography of wheat Yellow rust. Nature Plants, 1(10), 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Beresford, R. M. (1982). Yellow rust (Puccinia striiformis), a new disease of wheat in New Zealand. Cereal Rusts Bulletin, 10, 35-41.

- Bezner Kerr R et al 2022 Food, Fibre, and Other Ecosystem Products Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ed H-O Pörtner et al(Cambridge University Press) pp 713–906.

- Bhardwaj, Subhash C., Gyanendra P. Singh, Om P. Gangwar, Pramod Prasad, and Subodh Kumar. “Status of wheat rust research and progress in rust management-Indian context.” Agronomy 9, no. 12 (2019): 892. [CrossRef]

- Boland, G. J., Melzer, M. S., Hopkin, A., Higgins, V., & Nassuth, A. (2004). Climate change and plant diseases in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 26(3), 335-350. [CrossRef]

- Boshoff, W. H. P., Pretorius, Z. A., & Van Niekerk, B. D. (2002). Establishment, distribution, and pathogenicity of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in South Africa. Plant Disease, 86(5), 485-492.

- Boshoff, W. H. P., Visser, B., Lewis, C. M., Adams, T. M., Saunders, D. G. O., Terefe, T., & Pretorius, Z. A. (2020). First report of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, causing yellow rust of wheat, in Zimbabwe. Plant Disease, 104(1), 290-290.

- Brar, G. S., Fetch, T., McCallum, B. D., Hucl, P. J., & Kutcher, H. R. (2019). Virulence dynamics and breeding for resistance to Yellow, stem, and leaf rust in Canada since 2000. Plant disease, 103(12), 2981-2995.

- Brown, J. K. (2015). Durable resistance of crops to disease: a Darwinian perspective. Annual review of phytopathology, 53(1), 513-539. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. K., & Hovmøller, M. S. (2002). Aerial dispersal of pathogens on the global and continental scales and its impact on plant disease. Science, 297(5581), 537-541. [CrossRef]

- Burdon, J. J., Thrall, P. H., & Ericson, A. L. (2006). The current and future dynamics of disease in plant communities. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol., 44(1), 19-39. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S. (2005). Potential impact of climate change on plant-pathogen interactions: Presented as a Keynote Address at the 15th Biennial Conference of the Australasian Plant Pathology Society, 26–29 September 2005, Geelong. Australasian Plant Pathology, 34(4), 443-448.

- Chakraborty, S., & Datta, S. (2003). How will plant pathogens adapt to host plant resistance at elevated CO2 under a changing climate?. New Phytologist, 159(3), 733-742. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S., & Newton, A. C. (2011). Climate change, plant diseases and food security: an overview. Plant pathology, 60(1), 2-14. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S., Luck, J., Hollaway, G., Fitzgerald, G., & White, N. (2011). Rust-proofing wheat for a changing climate. Euphytica, 179, 19-32. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S., Luck, J., Hollaway, G., Fitzgerald, G., & White, N. (2011). Rust-proofing wheat for a changing climate. Euphytica, 179, 19-32. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S., Tiedemann, A. V., & Teng, P. S. (2000). Climate change: potential impact on plant diseases. Environmental pollution, 108(3), 317-326. [CrossRef]

- Chaloner, T. M., Gurr, S. J., & Bebber, D. P. (2020). Geometry and evolution of the ecological niche in plant-associated microbes. Nature Communications, 11(1), 2955. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Duan, G. H., Li, D. L., & Zhan, J. (2017). Host resistance and temperature-dependent evolution of aggressiveness in the plant pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8, 1217. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Wellings, C., Chen, X., Kang, Z., & Liu, T. (2014). Wheat Yellow (yellow) rust caused by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Molecular plant pathology, 15(5), 433-446.

- Chen, W., Zhang, Z., Chen, X., Meng, Y., Huang, L., Kang, Z., & Zhao, J. (2021). Field production, germinability, and survival of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici teliospores in China. Plant Disease, 105(8), 2122-2128.

- Chen, X. (2020). Pathogens which threaten food security: Puccinia striiformis, the wheat yellow rust pathogen. Food Security, 12(2), 239-251. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. M. (2005). Epidemiology and control of yellow rust [Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici] on wheat. Canadian journal of plant pathology, 27(3), 314-337.

- Chen, X. M. (2007). Challenges and solutions for yellow rust control in the United States. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research, 58(6), 648-655.

- Chen, X. M. (2007). Challenges and solutions for yellow rust control in the United States. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research, 58(6), 648-655. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. M., & Kang, Z. S. (Eds.). (2017). Yellow Rust (719 pages). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Chen, X., Wang, M., Wan, A., Bai, Q., Li, M., López, P. F., & Abdelrhim, A. S. (2021). Virulence characterization of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici collections from six countries in 2013 to 2020. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 43(sup2), S308-S322.

- Chen, X.M. (2013) Review article: High-temperature adult-plant resistance, key for sustainable control of yellow rust. Am. J. Plant Sci. 4, 608–627.

- Clifford, B. C., & Harris, R. G. (1981). Controlled environment studies of the epidemic potential of Puccinia recondita f. sp. tritici on wheat in Britain. Transactions of the British mycological Society, 77(2), 351-358. [CrossRef]

- Coakley, S. M. (1979). Climate variability in the Pacific Northwest and its effect on yellow rust disease of winter wheat. Climatic Change, 2(1), 33-51. [CrossRef]

- Coakley, S. M., Scherm, H., & Chakraborty, S. (1999). Climate change and plant disease management. Annual review of phytopathology, 37(1), 399-426. [CrossRef]

- Crowl, T. A., Crist, T. O., Parmenter, R. R., Belovsky, G., & Lugo, A. E. (2008). The spread of invasive species and infectious disease as drivers of ecosystem change. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 6(5), 238-246.

- de Vallavieille-Pope, C., Ali, S., Leconte, M., Enjalbert, J., Delos, M., & Rouzet, J. (2012). Virulence dynamics and regional structuring of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in France between 1984 and 2009. Plant Disease, 96(1), 131-140.

- de Vallavieille-Pope, C., Bahri, B., Leconte, M., Zurfluh, O., Belaid, Y., Maghrebi, E., & Bancal, M. O. (2018). Thermal generalist behaviour of invasive Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici strains under current and future climate conditions. Plant Pathology, 67(6), 1307-1320.

- Dean, R., Van Kan, J. A., Pretorius, Z. A., Hammond-Kosack, K. E., Di Pietro, A., Spanu, P. D., & Foster, G. D. (2012). The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Molecular plant pathology, 13(4), 414-430.

- Dennis, J. I. (1987). Effect of high temperatures on survival and development of Puccinia striiformis on wheat. Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 88(1), 91-96. [CrossRef]

- Dennis, J.I. (1987) Temperature and wet-period conditions for infection by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici race 104e137a+. Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 88: 119-121.

- Donald, F., Green, S., Searle, K., Cunniffe, N. J., & Purse, B. V. (2020). Small scale variability in soil moisture drives infection of vulnerable juniper populations by invasive forest pathogen. Forest Ecology and Management, 473, 118324. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z., Hegarty, J. M., Zhang, J., Zhang, W., Chao, S., Chen, X., & Dubcovsky, J. (2017). Validation and characterization of a QTL for adult plant resistance to yellow rust on wheat chromosome arm 6BS (Yr78). Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 130, 2127-2137.

- Dossa, G. S., Oliva, R., Maiss, E., Vera Cruz, C., & Wydra, K. (2016). High temperature enhances the resistance of cultivated African rice, Oryza glaberrima, to bacterial blight. Plant Disease, 100(2), 380-387. [CrossRef]

- Draz, I. S. (2019a). Common Ancestry of Egyptian Puccinia striiformis population along with effective and ineffective resistance genes. Asian Journal of Biological Sciences, 12, 217-221. [CrossRef]

- Draz, I. S. (2019b). Pathotypic and molecular evolution of contemporary population of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in Egypt during 2016–2018. Journal of Phytopathology, 167(1), 26-34.

- Druzhin, A.E. Effect of climate change on the structure of populations of spring wheat pathogens in the Volga region. Agrar. Report. South-East 2010, 1, 31-36. (In Russian).

- Duveiller, E., Singh, R. P., & Nicol, J. M. (2007). The challenges of maintaining wheat productivity: pests, diseases, and potential epidemics. Euphytica, 157(3), 417-430. [CrossRef]

- Dyck, P. L., & Johnson, R. (1983). Temperature sensitivity of genes for resistance in wheat to Puccinia recondita. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 5(4), 229-234. [CrossRef]

- Eastburn, D. M., McElrone, A. J., & Bilgin, D. D. (2011). Influence of atmospheric and climatic change on plant–pathogen interactions. Plant pathology, 60(1), 54-69. [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, H., Plakhine, D., Hershenhorn, J., Kleifeld, Y., & Rubin, B. (2003). Resistance to broomrape (Orobanche spp.) in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) is temperature dependent. Journal of Experimental Botany, 54(385), 1305-1311. [CrossRef]

- El Amil, R., Shykoff, J. A., Vidal, T., Boixel, A. L., Leconte, M., Hovmøller, M. S., ... & de Vallavieille-Pope, C. (2022). Diversity of thermal aptitude of Middle Eastern and Mediterranean Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici isolates from different altitude zones. Plant Pathology, 71(8), 1674-1687.

- Elbasyoni, I. S., El-Orabey, W. M., Morsy, S., Baenziger, P. S., Al Ajlouni, Z., & Dowikat, I. (2019). Evaluation of a global spring wheat panel for yellow rust: Resistance loci validation and novel resources identification. PLoS One, 14(11), e0222755.

- El-Orabey, W. M., Elbasyoni, I. S., El-Moghazy, S. M., & Ashmawy, M. A. (2019). Effective and ineffective of some resistance genes to wheat leaf, stem and yellow rust diseases in Egypt. Journal of Plant Production, 10(4), 361-371. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, J. (1894). Uber die Spezialisierung des Parasitismus bei den Getreiderostpilzen. Berichte der Deutschen Botanischen Gesellschaft, 12, 292–331.

- Esmail, S. M., Draz, I. S., Ashmawy, M. A., & El-Orabey, W. M. (2021). Emergence of new aggressive races of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici causing yellow rust epiphytotic in Egypt. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology, 114, 101612. [CrossRef]

- Esmail, S. M., Omar, G. E., El-Orabey, W. M., Börner, A., & Mourad, A. M. (2023). Exploring the genetic variation of yellow rust foliar and head infection in Egyptian wheat as an effect of climate change. Agronomy, 13(6), 1509. [CrossRef]

- Ezzahiri B, Yahyaoui A, Hovmøller MS (2009) An analysis of the 2009 Epidemic of yellow rust on wheat in Morocco. In The 4th Regional Yellow Rust Conference for Central and West Asia and North Africa (Antalya: Turkish Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, ICARDA, CIMMYT, FAO of the United Nations).

- Feng, J., Wang, M., See, D. R., Chao, S., Zheng, Y., & Chen, X. (2018). Characterization of novel gene Yr79 and four additional quantitative trait loci for all-stage and high-temperature adult-plant resistance to yellow rust in spring wheat PI 182103. Phytopathology, 108(6), 737-747. [CrossRef]

- Feodorova-Fedotova, L., & Bankina, B. (2018). Characterization of yellow rust (Puccinia striiformis westend). Research for Rural Development, 2.

- Fu, D., Uauy, C., Distelfeld, A., Blechl, A., Epstein, L., Chen, X., & Dubcovsky, J. (2009). A kinase-START gene confers temperature-dependent resistance to wheat yellow rust. science, 323(5919), 1357-1360. [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, O. P., Kumar, S., Prasad, P., Bhardwaj, S. C., Khan, H., & Verma, H. (2016). Virulence pattern and emergence of new pathotypes in Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici during 2011-15 in India. Indian Phytopathol, 69(4s), 178-185.

- Gardner, H., Onofre, K. F. A., & De Wolf, E. D. (2023). Characterizing the response of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici to periods of heat stress that are common in Kansas and the great plains region of North America. Phytopathology®, 113(8), 1457-1464.

- Garrett, K. A., Bebber, D. P., Etherton, B. A., Gold, K. M., Plex Sulá, A. I., & Selvaraj, M. G. (2022). Climate change effects on pathogen emergence: Artificial intelligence to translate big data for mitigation. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 60(1), 357-378. [CrossRef]

- Garrett, K. A., Dendy, S. P., Frank, E. E., Rouse, M. N., & Travers, S. E. (2006). Climate change effects on plant disease: genomes to ecosystems. Annual Review of Phytopathology 44(1), 489-509.

- Ghelardini, L., Pepori, A. L., Luchi, N., Capretti, P., & Santini, A. (2016). Drivers of emerging fungal diseases of forest trees. Forest Ecology and Management, 381, 235-246. [CrossRef]

- Gladders, P., Langton, S. D., Barrie, I. A., Hardwick, N. V., Taylor, M. C., & Paveley, N. D. (2007). The importance of weather and agronomic factors for the overwinter survival of yellow rust (Puccinia striiformis) and subsequent disease risk in commercial wheat crops in England. Annals of applied Biology, 150(3), 371-382. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C., Almeida, A. S., Coutinho, J., Costa, R., Pinheiro, N., Coco, J., & Maçãs, B. (2018). Foliar fungicide application as management strategy to minimize the growing threat of yellow rust on wheat in Portugal. Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture, 30(9), 715-724.

- GRRC report of yellow and stem rust races 2022: GRRC, Aarhus University, Denmark www.wheatrust.org.

- Gulev SK, Thorne PW, Ahn J, Dentener FJ, Domingues CM, Gerland S, Gong D, Kaufman DS, Nnamchi HC, Quaas J, Rivera JA, Sathyendranath S, Smith SL, Trewin B, von Schuckmann K, Vose RS (2021) Changing state of the climate system. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Chapter 2. [CrossRef]

- Gultyaeva, E., Shaydayuk, E., Gannibal, P., & Kosman, E. (2021). Analysis of host-specific differentiation of Puccinia striiformis in the South and North-West of the European Part of Russia. Plants, 10(11), 2497.

- He, X., Gahtyari, N. C., Roy, C., Dababat, A. A., Brar, G. S., & Singh, P. K. (2022). Globally important non-rust diseases of wheat. In Wheat Improvement: Food Security in a Changing Climate (pp. 143-158). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Heagle, A. S., Spencer, S., & Letchworth, M. B. (1979). Yield response of winter wheat to chronic doses of ozone. Canadian Journal of Botany, 57(19), 1999-2005. [CrossRef]

- Helfer, S. (2014). Rust fungi and global change. New phytologist, 201(3), 770-780. [CrossRef]

- Helguera, M., Khan, I. A., Kolmer, J., Lijavetzky, D., Zhong-Qi, L., & Dubcovsky, J. (2003). PCR assays for the Lr37-Yr17-Sr38 cluster of rust resistance genes and their use to develop isogenic hard red spring wheat lines. Crop science, 43(5), 1839-1847. [CrossRef]

- Hovmøller, M. S., & Justesen, A. F. (2007). Appearance of atypical Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici phenotypes in north-western Europe. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research, 58(6), 518-524. [CrossRef]

- Hovmøller, M. S., Thach, T., & Justesen, A. F. (2023). Global dispersal and diversity of rust fungi in the context of plant health. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 71, 102243. [CrossRef]

- Hovmøller, M. S., Walter, S., Bayles, R. A., Hubbard, A., Flath, K., Sommerfeldt, N., ... & de Vallavieille-Pope, C. (2016). Replacement of the European wheat yellow rust population by new races from the centre of diversity in the near-Himalayan region. Plant Pathology, 65(3), 402-411. [CrossRef]

- Hovmøller, M. S., Yahyaoui, A. H., Milus, E. A., & Justesen, A. F. (2008). Rapid global spread of two aggressive strains of a wheat rust fungus. Molecular Ecology, 17(17), 3818-3826. [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, A., Lewis, C. M., Yoshida, K., Ramirez-Gonzalez, R. H., de Vallavieille-Pope, C., Thomas, J., ... & Saunders, D. G. (2015). Field pathogenomics reveals the emergence of a diverse wheat yellow rust population. Genome biology, 16, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, S., & Pumphrey, M. (2014). A time for more booms and fewer busts? Unraveling cereal–rust interactions. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 27(3), 207-214. [CrossRef]

- Hussain M, Kirmani MAS, Haque E, 2004. Pathotypes and man guided evolution of Puccinia striiformis West sp. tritici in Pakistan. Abstracts, Second Regional Yellow Rust Conference for Central & West Asia and North Africa, 22–26 March 2004, Islamabad, Pakistan. 21.

- ICARDA. (2011). Strategies to reduce the emerging wheat yellow rust disease. Synthesis of a dialog between policy makers and scientists from 31 countries at: International Wheat Yellow Rust Symposium, Aleppo, Syria, April 2011. International Center for Agriculture Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) http://www.fao.org/familyfarming/detail/en/c/325927/. Accessed 8 Nov 2019.

- Indu, S., & Saharan, M. S. (2011). Status of wheat diseases in India with a special reference to yellow rust. Plant Dis. Res, 26, 156.

- IPCC 2022 Summary for Policymakers Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ed H O Pörtner et al (Cambridge University Press) pp 3–33.

- IPCC 2023 Summary for policymakers Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Core Writing Team ed H Lee and J Romero (IPCC, Geneva) pp 1–34.

- IPCC Secretariat. (2021). Scientific review of the impact of climate change on plant pests-A global challenge to prevent and mitigate plant pest risks in agriculture, forestry and ecosystems. FAO on behalf of the IPCC Secretariat. https://doir.org/10.4060/cb4769en.

- Ivanova, Y. N., Rosenfread, K. K., Stasyuk, A. I., Skolotneva, E. S., & Silkova, O. G. (2021). Raise and characterization of a bread wheat hybrid line (Tulaykovskaya 10× Saratovskaya 29) with chromosome 6Agi2 introgressed from Thinopyrum intermedium. Vavilov Journal of Genetics and Breeding, 25(7), 701-712. [CrossRef]

- Jevtić, R., Župunski, V., Lalošević, M., & Župunski, L. (2017). Predicting potential winter wheat yield losses caused by multiple disease systems and climatic conditions. Crop Protection, 99, 17-25. [CrossRef]

- Jevtić, R., Župunski, V., Lalošević, M., Jocković, B., Orbović, B., & Ilin, S. (2020). Diversity in susceptibility reactions of winter wheat genotypes to obligate pathogens under fluctuating climatic conditions. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 19608. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., Szabo, L. J., & Carson, M. (2010). Century-old mystery of Puccinia striiformis life history solved with the identification of Berberis as an alternate host. Phytopathology, 100(5), 432-435. [CrossRef]

- Jindal MM, Mohan C, Pannu PPS (2012) Status of Yellow rust of wheat in Punjab during 2011-12 season. In: Proceedings of brain storming session. Department of Plant Pathology PAU, Ludhian, p 56.

- Juroszek, P., & von Tiedemann, A. (2013). Climate change and potential future risks through wheat diseases: a review. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 136, 21-33.

- Juroszek, P., Racca, P., Link, S., Farhumand, J., & Kleinhenz, B. (2020). Overview on the review articles published during the past 30 years relating to the potential climate change effects on plant pathogens and crop disease risks. Plant pathology, 69(2), 179-193. [CrossRef]

- Khanfri, S., Boulif, M., & Lahlali, R. (2018). Yellow rust (Puccinia striiformis): a serious threat to wheat production worldwide. Notulae Scientia Biologicae, 10(3), 410-423. [CrossRef]

- Kokhmetova, A., Sharma, R. C., Rsaliyev, S., Galymbek, K., Baymagambetova, K., Ziyaev, Z., & Morgounov, A. (2018). Evaluation of Central Asian wheat germplasm for yellow rust resistance. Plant Genetic Resources, 16(2), 178-184. [CrossRef]

- Krattinger, S.G., Lagudah, E.S., Spielmeyer, W., Singh, R.P., Huerta-Espino, J., McFadden, H., Bossolini, E., Selter, L.L., Keller, B. (2009). A putative ABC transporter confers durable resistance to multiple fungal pathogens in wheat. Science 323, 1360–1363. [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, K. D. (2009). The ecology of climate change and infectious diseases. Ecology, 90(4), 888-900.

- Lan, C., Randhawa, M. S., Huerta-Espino, J., & Singh, R. P. (2017). Genetic analysis of resistance to wheat rusts. Wheat Rust Diseases: Methods and Protocols, 137-149.

- Lee JY, Marotzke J, Bala G, Cao L, Corti S, Dunne JP, Engelbrecht F, Fischer E, Fyfe JC, Jones C, Maycock A, Mutemi J, Ndiaye O, Panickal S, Zhou T (2021) Future global climate: scenario-based projections and near-term information. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Chapter 4. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Q., & Zeng, S. M. (2002). Wheat rusts in China (pp. 379). Beijing: Chinese Agricultural Press (In Chinese).

- Line, R. F. (2002). Yellow rust of wheat and barley in North America: a retrospective historical review. Annual review of phytopathology, 40(1), 75-118.

- Liu, L., Wang, M. N., Feng, J. Y., See, D. R., Chao, S. M., & Chen, X. M. (2018). Combination of all-stage and high-temperature adult-plant resistance QTL confers high-level, durable resistance to yellow rust in winter wheat cultivar Madsen. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 131, 1835-1849. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Wang, M., Zhang, Z., See, D. R., & Chen, X. (2020). Identification of Yellow rust resistance loci in US spring wheat cultivars and breeding lines using genome-wide association mapping and Yr gene markers. Plant Disease, 104(8), 2181-2192.

- Liu, L., Yuan, C. Y., Wang, M. N., See, D. R., Zemetra, R. S., & Chen, X. M. (2019). QTL analysis of durable yellow rust resistance in the North American winter wheat cultivar Skiles. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 132, 1677-1691.

- Loladze, A., Druml, T., & Wellings, C. R. (2014). Temperature adaptation in Australasian populations of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Plant pathology, 63(3), 572-580.

- Lu, Y., Wang, M., Chen, X., See, D., Chao, S., & Jing, J. (2014). Mapping of Yr62 and a small-effect QTL for high-temperature adult-plant resistance to yellow rust in spring wheat PI 192252. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 127, 1449-1459. [CrossRef]

- Lyon, B., & Broders, K. (2017). Impact of climate change and race evolution on the epidemiology and ecology of yellow rust in central and eastern USA and Canada. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 39(4), 385-392.

- Ma, L., Qiao, J., Kong, X., Zou, Y., Xu, X., Chen, X., & Hu, X. (2015). Effect of low temperature and wheat winter-hardiness on survival of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici under controlled conditions. PLoS One, 10(6), e0130691. [CrossRef]

- Mashaheet, A. M., Burkey, K. O., Saitanis, C. J., Abdelrhim, A. S., Rafiullah, & Marshall, D. S. (2020). Differential ozone responses identified among key rust-susceptible wheat genotypes. Agronomy, 10(12), 1853.

- Mboup, M., Bahri, B., Leconte, M., De Vallavieille-Pope, C., Kaltz, O., & Enjalbert, J. (2012). Genetic structure and local adaptation of European wheat yellow rust populations: the role of temperature-specific adaptation. Evolutionary applications, 5(4), 341-352. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, B. A., & Linde, C. (2002). Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential, and durable resistance. Annual review of phytopathology, 40(1), 349-379.

- Mcelrone, A. J., Reid, C. D., Hoye, K. A., Hart, E., & Jackson, R. B. (2005). Elevated CO2 reduces disease incidence and severity of a red maple fungal pathogen via changes in host physiology and leaf chemistry. Global Change Biology, 11(10), 1828-1836. [CrossRef]

- Megahed, E. M., Awaad, H. A., Ramadan, I. E., Abdul-Hamid, M. I., Sweelam, A. A., El-Naggar, D. R., & Mansour, E. (2022). Assessing performance and stability of yellow rust resistance, heat tolerance, and agronomic performance in diverse bread wheat genotypes for enhancing resilience to climate change under Egyptian conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, 1014824.

- Miedaner, T., & Juroszek, P. (2021). Climate change will influence disease resistance breeding in wheat in Northwestern Europe. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 134(6), 1771-1785. [CrossRef]

- Mills, G., Sharps, K., Simpson, D., Pleijel, H., Broberg, M., Uddling, J., ... & Van Dingenen, R. (2018). Ozone pollution will compromise efforts to increase global wheat production. Global change biology, 24(8), 3560-3574. [CrossRef]

- Milus, E. A., Kristensen, K., & Hovmøller, M. S. (2009). Evidence for increased aggressiveness in a recent widespread strain of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici causing yellow rust of wheat. Phytopathology, 99(1), 89-94.

- Milus, E. A., Seyran, E., & McNew, R. (2006). Aggressiveness of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici isolates in the south-central United States. Plant Disease, 90(7), 847-852.

- Mourad, A. M., Abou-Zeid, M. A., Eltaher, S., Baenziger, P. S., & Börner, A. (2021). Identification of candidate genes and genomic regions associated with adult plant resistance to yellow rust in spring wheat. Agronomy, 11(12), 2585. [CrossRef]

- Mu, J., Liu, L., Liu, Y., Wang, M., See, D. R., Han, D., & Chen, X. (2020). Genome-wide association study and gene specific markers identified 51 genes or QTL for resistance to yellow rust in US winter wheat cultivars and breeding lines. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 998. [CrossRef]

- Murray, G. M., & Brennan, J. P. (2009). Estimating disease losses to the Australian wheat industry. Australasian Plant Pathology, 38(6), 558-570.

- Niks, R. E., Qi, X., & Marcel, T. C. (2015). Quantitative resistance to biotrophic filamentous plant pathogens: concepts, misconceptions, and mechanisms. Annual review of phytopathology, 53(1), 445-470. [CrossRef]

- Nnadi, N. E., & Carter, D. A. (2021). Climate change and the emergence of fungal pathogens. PLoS pathogens, 17(4), e1009503.

- Novotná M, Hloucalová P, Skládanka J, Pokorný R (2017) Effect of weather on the occurrence of Puccinia graminis subsp. graminicola and Puccinia coronata f. sp. lolii at Lolium perenne L. and Deschampsia caespitosa (L.). Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 65: 125-134. [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, J. B., Danial, D. L., & Paucar, B. (2007). Virulence of wheat yellow rust races and resistance genes of wheat cultivars in Ecuador. Euphytica, 153(3), 287-293. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, R., Sayre, K. D., Govaerts, B., Gupta, R., Subbarao, G. V., Ban, T., ... & Reynolds, M. (2008). Climate change: can wheat beat the heat?. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 126(1-2), 46-58. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Bobea, A., Ault, T. R., Carrillo, C. M., Chambers, R. G., & Lobell, D. B. (2021). Anthropogenic climate change has slowed global agricultural productivity growth. Nature Climate Change, 11(4), 306-312.

- Pariaud, B., Ravigné, V., Halkett, F., Goyeau, H., Carlier, J., & Lannou, C. (2009). Aggressiveness and its role in the adaptation of plant pathogens. Plant Pathology, 58(3), 409-424. [CrossRef]

- Pariaud, B., Robert, C., Goyeau, H., & Lannou, C. (2009b). Aggressiveness components and adaptation to a host cultivar in wheat leaf rust. Phytopathology, 99(7), 869-878.

- Pathak, R., Singh, S. K., Tak, A., & Gehlot, P. (2018). Impact of climate change on host, pathogen and plant disease adaptation regime: a review. Biosciences Biotechnology Research Asia, 15(3), 529-540. [CrossRef]

- Pautasso, M., Döring, T. F., Garbelotto, M., Pellis, L., & Jeger, M. J. (2012). Impacts of climate change on plant diseases-opinions and trends. European journal of plant pathology, 133, 295-313.

- Prank, M., Kenaley, S. C., Bergstrom, G. C., Acevedo, M., & Mahowald, N. M. (2019). Climate change impacts the spread potential of wheat stem rust, a significant crop disease. Environmental Research Letters, 14(12), 124053. [CrossRef]

- Prashar, M., Bhardwaj, S. C., Jain, S. K., & Datta, D. (2007). Pathotypic evolution in Puccinia striiformis in India during 1995–2004. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research, 58(6), 602-604. [CrossRef]

- Prashar, M., Bhardwaj, S. C., Jain, S. K., & Datta, D. (2007). Pathotypic evolution in Puccinia striiformis in India during 1995–2004. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research, 58(6), 602-604. [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, Z. A. (2004). The impact of wheat yellow rust in South Africa. In Proc 11th Intl Cereal Rusts and Powdery Mildews Conf, 22–27 Aug 2004, John Innes Centre, Norwich, UK, European and Mediterranean Cereal Rust Foundation, Wageningen, Netherland, Cereal Rusts and Powdery Mildews Bulletin, Abstract A1.29.

- Priestley, R. H., & Bayles, R. A. (1988). The contribution and value of resistant cultivars to disease control in cereals. In B. C. Clifford & E. Lester (Eds.), Control of plant diseases, Costs and Benefits (pp. 53–65). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

- Rahmatov M, Eshonova Z, Ibrogimov A, Otambekova M, Khuseinov B, Muminjanov H et al (2012) Monitoring and evaluation of yellow rust for breeding resistant varieties of wheat in Tajikistan. In Meeting the Challenge of Yellow Rust in Cereal Crops Proceedings of the 2nd, 3rd and 4th Regional Conferences on Yellow Rust in Central and West Asia and North Africa (CWANA) Region, Yahyaoui A, Rajaram S (eds) International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, Alnarp.

- Ren, R. S., Wang, M. N., Chen, X. M., & Zhang, Z. J. (2012). Characterization and molecular mapping of Yr52 for high-temperature adult-plant resistance to yellow rust in spring wheat germplasm PI 183527. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 125, 847-857. [CrossRef]

- Roelfs, A. P., R. P. Singh and E. E. Saari. 1992. Rust Diseases of Wheat: Concepts and.

- methods of disease management. Mexico, D.F.: CIMMYT. 81 pages.

- Rodriguez-Algaba, J., Sørensen, C. K., Labouriau, R., Justesen, A. F., & Hovmøller, M. S. (2019). Susceptibility of winter wheat and triticale to yellow rust influenced by complex interactions between vernalisation, temperature, plant growth stage and pathogen race. Agronomy, 10(1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Saari, E. E., & Prescott, J. M. (1985). World distribution in relation to economic losses. In A. P. Roelfs & W. R. Bushnell (Eds.), The cereal rusts (Vol. II, pp. 259–298). Orlando: Academic Press.

- Sánchez Espinosa, K. C., Fernández-González, M., Almaguer, M., Guada, G., & Rodríguez-Rajo, F. J. (2023). Puccinia Spore Concentrations in Relation to Weather Factors and Phenological Development of a Wheat Crop in Northwestern Spain. Agriculture, 13(8), 1637. [CrossRef]

- Sanin, S.S. Agricultural plant disease control-The main factor of the crop production intensification. Plant Prot. News. 2010, 1,3–14. (In Russian).

- Santra, D. K., Chen, X. M., Santra, M., Campbell, K. G., & Kidwell, K. K. (2008). Identification and mapping QTL for high-temperature adult-plant resistance to Yellow rust in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivar ‘Stephens’. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 117, 793-802.

- Savadi, S. (2018). Molecular regulation of seed development and strategies for engineering seed size in crop plants. Plant Growth Regulation, 84(3), 401-422. [CrossRef]

- Savary, S., Willocquet, L., Pethybridge, S. J., Esker, P., McRoberts, N., & Nelson, A. (2019). The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nature ecology & evolution, 3(3), 430-439.

- Schade, F. M., Shama, L. N., & Wegner, K. M. (2014). Impact of thermal stress on evolutionary trajectories of pathogen resistance in three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). BMC evolutionary biology, 14, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Scherm H, Yang, X. B. (1995) Interannual variations in wheat rust development in China and the United States in relation to the El Niño/Southern Oscillation. Phytopathology 85:970-976.

- Scherm, H., & Yang, X. B. (1998). Atmospheric teleconnection patterns associated with wheat Yellow rust disease in North China. International Journal of Biometeorology, 42, 28-33. [CrossRef]

- Schimanke, S., Joelsson, M., Andersson, S., Carlund, T., Wern, L., Hellström, S., & Kjellström, E. (2022). Observerad klimatförändring i Sverige 1860–2021.

- Scholthof, K. B. G. (2007). The disease triangle: pathogens, the environment and society. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 5(2), 152-156.

- Schwessinger, B. (2017). Fundamental wheat Yellow rust research in the 21st century. New Phytologist, 213(4), 1625-1631.

- Shahin, A. A. (2020). Occurrence of new races and virulence changes of the wheat Yellow rust pathogen (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) in Egypt. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection, 53(11-12), 552-569.

- Shahin, A., Draz, I., & Esmail, S. (2020). Race specificity of Yellow rust resistance in relation to susceptibility of Egyptian wheat cultivars. Egyptian Journal of Phytopathology, 48(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.; Shaheen, S.; Abu, A. A. A. (2015) Virulence and Diversity of Wheat Yellow Rust Pathogen in Egypt. J. Am. Sci., 11, 47–52.

- Sharma-Poudyal, D., Chen, X. M., Wan, A. M., Zhan, G. M., Kang, Z. S., Cao, S. Q., ... & Patzek, L. J. (2013). Virulence characterization of international collections of the wheat Yellow rust pathogen, Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Plant Disease, 97(3), 379-386.

- Sharma-Poudyal, D., Chen, X., & Rupp, R. A. (2014). Potential over summering and overwintering regions for the wheat yellow rust pathogen in the contiguous United States. International journal of biometeorology, 58, 987-997.

- Shaw, M. W., Bearchell, S. J., Fitt, B. D., & Fraaije, B. A. (2008). Long-term relationships between environment and abundance in wheat of Phaeosphaeria nodorum and Mycosphaerella graminicola. New Phytologist, 177(1), 229-238. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V. K., Mathuria, R. C., Gogoi, R. O. B. I. N., & Aggarwal, R. A. S. H. M. I. (2016). Impact of different fungicides and bioagents, and fungicidal spray timing on wheat Yellow rust development and grain yield. Indian Phytopath, 69(4), 357-362.

- Solh, M., Nazari, K., Tadesse, W., & Wellings, C. R. (2012). The growing threat of Yellow rust worldwide. BGRI 2012 Technical workshop, 1–4 September 2012, Beijing, China. Borlaug Global Rust Initiative.

- Strandberg, G., Andersson, B., & Berlin, A. (2024). Plant pathogen infection risk and climate change in the Nordic and Baltic countries. Environmental research communications, 6(3), 031008. [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, R. W. (1985). Yellow rust. In A. P. Roelfs & W. R. Bushnell (Eds.), The cereal rusts (Vol. II, pp. 61–101). Orlando: Academic Press.

- Sturrock, R. N., Frankel, S. J., Brown, A. V., Hennon, P. E., Kliejunas, J. T., Lewis, K. J., ... & Woods, A. J. (2011). Climate change and forest diseases. Plant pathology, 60(1), 133-149.

- Sukumar Chakraborty, S. C., Luck, J., Hollaway, G., Freeman, A., Norton, R., Garrett, K. A., & Karnosky, D. F. (2008). Impacts of global change on diseases of agricultural crops and forest trees. CABI Reviews, (2008), 1-15.

- Tariq-Khan, M., Younas, M. T., Mirza, J. I., Awan, S. I., Jameel, M., Saeed, M., & Mahmood, B. (2020). Evaluation of major and environmentally driven genes for resistance in Pakistani wheat landraces and their prospected potential against yellow rust. International Journal of Phytopathology, 9(3), 145-156. [CrossRef]

- Tiedemann, A. V., & Firsching, K. H. (2000). Interactive effects of elevated ozone and carbon dioxide on growth and yield of leaf rust-infected versus non-infected wheat. Environmental Pollution, 108(3), 357-363. [CrossRef]

- Uauy, C., Brevis, J. C., Chen, X., Khan, I., Jackson, L., Chicaiza, O., ... & Dubcovsky, J. (2005). High-temperature adult-plant (HTAP) Yellow rust resistance gene Yr36 from Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides is closely linked to the grain protein content locus Gpc-B1. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 112, 97-105.

- Vergara-Diaz, O., Kefauver, S. C., Elazab, A., Nieto-Taladriz, M. T., & Araus, J. L. (2015). Grain yield losses in yellow-rusted durum wheat estimated using digital and conventional parameters under field conditions. The Crop Journal, 3(3), 200-210.

- Vidal, T., Boixel, A. L., Maghrebi, E., Perronne, R., du Cheyron, P., Enjalbert, J., ... & de Vallavieille-Pope, C. (2022). Success and failure of invasive races of plant pathogens: the case of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in France. Plant pathology, 71(7), 1525-1536.

- Waheed, A., Haxim, Y., Islam, W., Ahmad, M., Muhammad, M., Alqahtani, F. M., ... & Zhang, D. (2023). Climate change reshaping plant-fungal interaction. Environmental Research, 117282. [CrossRef]

- Walter, S., Ali, S., Kemen, E., Nazari, K., Bahri, B. A., Enjalbert, J., ... & Justesen, A. F. (2016). Molecular markers for tracking the origin and worldwide distribution of invasive strains of Puccinia striiformis. Ecology and Evolution, 6(9), 2790-2804. [CrossRef]

- Wan, A., Zhao, Z., Chen, X., He, Z., Jin, S., Jia, Q., ... & Yuan, Z. (2004). Wheat Yellow rust epidemic and virulence of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in China in 2002. Plant Disease, 88(8), 896-904.

- Wang, M.N., Chen, X.M., 2017. Yellow rust resistance. In: Kang, Z.S. (Ed.), Yellow Rust. X. M. Chen. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 353–558.

- Webb, K. M., Ona, I., Bai, J., Garrett, K. A., Mew, T., Vera Cruz, C. M., & Leach, J. E. (2010). A benefit of high temperature: increased effectiveness of a rice bacterial blight disease resistance gene. New Phytologist, 185(2), 568-576. [CrossRef]

- Wellings, C. R. (2007). Puccinia striiformis in Australia: a review of the incursion, evolution, and adaptation of Yellow rust in the period 1979–2006. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research, 58(6), 567-575. [CrossRef]

- Wellings, C. R. (2011). Global status of Yellow rust: a review of historical and current threats. Euphytica, 179(1), 129-141.

- Weng, Y., Azhaguvel, P., Devkota, R. N., & Rudd, J. C. (2007). PCR-based markers for detection of different sources of 1AL. 1RS and 1BL. 1RS wheat–rye translocations in wheat background. Plant Breeding, 126(5), 482-486.

- Wiik, L., & Ewaldz, T. (2009). Impact of temperature and precipitation on yield and plant diseases of winter wheat in southern Sweden 1983–2007. Crop Protection, 28(11), 952-962. [CrossRef]

- WMO 2022 State of the global climate 2021 WMO-No. 1290 57 ISBN 978-92-63-11290-3 https://library.wmo.int/records/item/56300-state-of-the-global-climate-2021 last access Aug 31, 2023.

- WMO 2023 State of the global climate 2022, WMO-No 1316 55 ISBN 978-92-63-11316-0 https://library.wmo.int/records/item/66214-state-of-the-global-climate-2022 last access Aug 31, 2023.

- World agricultural production. USDA https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/production.pdf (2022).

- Wyka, S. A., Smith, C., Munck, I. A., Rock, B. N., Ziniti, B. L., & Broders, K. (2017). Emergence of white pine needle damage in the northeastern United States is associated with changes in pathogen pressure in response to climate change. Global Change Biology, 23(1), 394-405. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. N., Zhu, W., Wu, E. J., Yang, C., Thrall, P. H., Burdon, J. J., ... & Zhan, J. (2016). Trade-offs and evolution of thermal adaptation in the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Molecular Ecology, 25(16), 4047-4058. [CrossRef]

- Zadoks, J. C., & Rijsdijk, F. H. (1984). Atlas of cereal diseases and pests in Europe. Agro-ecological atlas of cereal growing in Europe Vol III. Pudoc, Wageningen, the Netherlands.

- Zeleneva, Y. V., Sudnikova, V. P., & Buchneva, G. N. (2022). Immunological characteristics of soft winter wheat varieties in conditions of the CBR. Proc. Kuban State Agrar. Univ, 96, 95-99. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J., & McDONALD, B. A. (2011). Thermal adaptation in the fungal pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. Molecular Ecology, 20(8), 1689-1701. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Q., Liu, B., Chen, W. Q., Liu, T. G., & Gao, L. (2013). Temperature-sensitivity of population of Puccinia striiformis Westend. Acta Phytopathologica Sinnica, 43(1), 88-90.

- Zhao, J., & Kang, Z. (2023). Fighting wheat rusts in China: a look back and into the future. Phytopathology Research, 5(1), 6.

- Zhao, J., Wang, M., Chen, X., & Kang, Z. (2016). Role of alternate hosts in epidemiology and pathogen variation of cereal rusts. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 54(1), 207-228. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. L., Wang, M. N., Chen, X. M., Lu, Y., Kang, Z. S., & Jing, J. X. (2014). Identification of Yr59 conferring high-temperature adult-plant resistance to Yellow rust in wheat germplasm PI 178759. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 127, 935-945. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z., Cao, Q., Han, D., Wu, J., Wu, L., Tong, J., ... & Hao, Y. (2023). Molecular characterization and validation of adult-plant Yellow rust resistance gene Yr86 in Chinese wheat cultivar Zhongmai 895. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 136(6), 142. [CrossRef]

- Župunski, V., Jevtić, R. & Lalošević, M. Te occurrence of yellow rust of winter wheat in relation to year. Book of abstracts of XV Symposium on plant protection, Zlatibor, Serbia, 28 November–02 December, pp. 89–90 (2016) (in Serbian).

| Developmental Stage |

Temperature (°C) | Light | Free water | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lowest |

Optimum |

Highest |

|||

| Germination | 0 | 9-13 | 23 | Low | Required |

| Germling | - | 10-15 | - | Low | Required |

| Appressorium | - | - | (not formed) | None | Required |

| Penetration | 2 | 9-13 | 23 | Low | Required |

| Growth | 3 | 12-15 | 20 | High | Not required |

| Sporulation | 5 | 12-15 | 20 | High | Not required |

| Years | Production (Million metric tons) |

Consumption (Million metric tons) |

|---|---|---|

| 2017-18 | 761.54 | 742.37 |

| 2018-19 | 730.92 | 735.31 |

| 2019-20 | 759.39 | 745.71 |

| 2020-21 | 773.09 | 786.57 |

| 2021-22 | 780.05 | 791.16 |

| 2022-23 | 789.17 | 790.93 |

| 2023-24 | 784.91 | 796.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).