1. Introduction

Machine learning (ML) has found its way into almost every domain and has been a promising tool overall. However, its data-driven approach comes with security challenges that include adversarial manipulation of data and exploitation of model vulnerabilities, to ultimately fail or deceive an ML model [

1]. Adversarial algorithms that trick ML classifiers into rendering incorrect or far-from-accurate outputs have become widely popular in image classification and cybersecurity domains.

Adversarial machine learning (AML) focuses on investigation of adversarial attack algorithms, their impact on ML models, and building robust ML algorithms that are resistant to adversarial attacks [

1,

2]. The first foundational work in AML dates back to 2004, when the problem was discovered in the context of spam filtering [

3]. Although AML has been popular for at least over a decade, its influence in the cybersecurity domain has not been thoroughly investigated compared to other areas such as computer vision [

4].

Cybersecurity is a unique area in many ways and complex in nature. Due to the complexity of this domain, concepts such as AML require thorough investigation and experimentation despite their popularity in other domains. The strategy an adversarial algorithm follows to perturb an image cannot be applied blindly to network data.

Intrusion detection systems (IDSs) powered by ML techniques have gained more popularity due to their superior performance and reduced false alarm rates compared to their traditional ancestors. The last few decades witnessed a spike in research activities focused on intelligent IDSs whose detection capabilities are powered by ML-based techniques. As discussions on AML became more common in the realms of image classification, natural language processing, etc., cybersecurity researchers started to focus more on AML. To secure existing ML-based IDS models against adversarial algorithms or to build more robust models, it is crucial to understand the impact of adversarial algorithms on the performance of IDS models.

Several adversarial methods have been proposed, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Some methods attempt to find the smallest change in original data that can maximize the likelihood of fooling the target system. Some other methods aim to perturb the data in a very short time to provide computational efficiency. Recent adversarial algorithms have relied on evolutionary computational techniques such as genetic algorithm (GA) and particle swarm optimization algorithm (PSO) to find the optimal perturbation to evade detection [

5]. Generative Adversarial Networks have also been used to create effective and deceptive adversarial samples [

6].

Knowledge of how various adversarial algorithms work helps in designing effective and reliable strategies to mitigate the impact of adversarial algorithms. In this article, we study two adversarial algorithms, the changes they introduce to network IDS data, and evaluate the performance of an IDS classifier in the presence of adversarial data. The following are the key contributions of this research.

Study the methodology of two adversarial algorithms - one employing a relatively simple perturbation approach, and the other utilizing a sophisticated evolutionary method;

Present the perturbations introduced by adversarial algorithms in the dataset;

Evaluate the impact of the said algorithms on the performance of an IDS classifier.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows.

Section 2 describes the concepts used in this research, such as attacks, dataset, and classification algorithm.

Section 3 presents the experimentation.

Section 4 presents the results and analysis.

Section 5 concludes the work and provides insight into the future directions of this research.

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Network Intrusion Detection Systems

Prompt identification of malicious activity is always a crucial task in cybersecurity. Network intrusion detection systems (NIDS) are the most popular network defenders that help identify abnormal activity in networks. Traditional NIDS were designed to assist human network analysts in examining traffic and alerting when abnormal activity was detected. They worked on predefined rules and conditions. The way in which NIDS solutions work varies significantly depending on the type of data they work with and detection strategies they use.

Earlier generations of NIDS heavily relied on deep packet inspection, which involved analyzing the payload of individual network packets. Although this strategy could offer high detection accuracy, with hugely growing volumes of data and the use of sophisticated encryption techniques on data, deep packet inspection became less practical [

7]. This has shifted the focus to flow-based detection strategies, which rely on metadata such as session duration, number of packets transmitted, and number of bytes transferred, among other details pertaining to communication between two end points [

8,

9]. This metadata is computationally feasible, easy to store, and does not pose privacy concerns.

In terms of detection mechanisms, traditional NIDS used signature-based methods [

10], where security experts manually developed rules to identify known threats. However, these mechanisms are ineffective against novel or unknown threat patterns. As attack behaviors grew more complex and sophisticated, traditional signature-based NIDS became less practical.

2.2. Machine Learning-Powered Network Intrusion Detection Systems

ML-powered NIDS have gained momentum in tasks related to anomaly detection. ML-based NIDS models harness the capabilities of ML techniques to learn traffic patterns from training data and make predictions on previously unseen traffic [

11,

12]. This reduces the burden of constant manual creation of rules and enhances the ability to detect zero-day attacks and advanced variants of known threats. These models can be trained using packet payloads or flow-based data. Several NIDS models relying on supervised and non-supervised learning techniques have been proposed. In addition, models powered by deep learning (DL) have also shown impressive detection abilities.

2.3. Adversarial algorithms

The primary goal of an adversarial algorithm is to bypass a detection system through deception. This deception involves carefully perturbing malicious data to make it appear benign to the detection system. An adversarial input is a data instance derived by adding carefully crafted noise (perturbation) to the original data [

13]. Adversarial algorithms are categorized as poisoning attacks if they are implemented during training phase, and as evasion attacks if they are implemented during deployment phase [

14]. Based on the adversary’s knowledge of the target system, attacks are typically classified as follows: black-box attacks, where the adversary has little-to-no knowledge of the target; white-box attacks, where the adversary has full or near-complete knowledge of the target; and gray-box attacks, where the adversary has partial knowledge of the target.

2.3.1. Gaussian perturbation method

The class of algorithms that generate adversarial samples by adding Gaussian noise to data are referred to as Gaussian perturbation algorithms. The core logic of these algorithms is to add a random noise drawn from Gaussian distribution.

Given an original input vector

x, the adversarial sample

is created as shown in equation

1.

Where is a fixed scalar that scales/controls the magnitude of the noise drawn from a Gaussian distribution with mean 0 and variance . The value of dictates the strength of the perturbation.

Gaussian perturbation approaches are simple yet fairly capable of performing baseline adversarial robustness testing of ML-based models. The reason behind choosing Gaussian approach for our work is to understand how such a straightforward methodology can influence a well-trained NIDS model.

2.3.2. Genetic algorithm

An evolutionary algorithm refers to a broad category of optimization methods that simulate natural evolution through population-based, stochastic search processes. Notable examples in this family of algorithms are genetic algorithms (GAs), evolutionary programming, and genetic programming [

15].

The GA, in particular, is inspired by natural selection. The algorithm initiates the adversarial crafting process by generating an initial population of input samples, which is passed through the target model to observe the corresponding outputs. Through iterative application of evolutionary operations - such as mutation, crossover, and selection, which are briefly explained following this paragraph — a new generation of potential adversarial samples is produced. These candidates are assessed based on their ability to fool the model. The most effective ones are retained and evolved further in subsequent iterations. This cycle continues until a potentially optimal adversarial instance is found. Overall, evolutionary algorithms are capable of creating model-specific adversarial inputs by progressively refining them to exploit target’s vulnerabilities [

13].

mutations: random alterations

crossover: the process of combining features of different inputs

selection: choosing the most promising candidates

For this study, we chose to evaluate NIDS with one simple perturbation method and one complex technique to investigate how the complexity of an attack influences the performance of the model.

2.4. Dataset

Due to the data-driven nature of machine learning, the quality of data significantly influences the knowledge a model acquires. In the rapidly evolving field of cybersecurity, there is a critical need to actively generate new datasets for educational and research purposes — ensuring that the data reflects contemporary networking trends and behaviors.

KDD Cup ’99 dataset is one of the most recognized datasets in artificial intelligence (AI)-powered network intrusion detection research. Originally developed for the Third International Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining competition (KDD Cup 1999), this dataset represents a processed version of Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA) 1998 dataset. The DARPA data was generated in a controlled simulated environment mimicking the activities of a U.S. Air Force local area network (LAN). The data was captured over a period of nine weeks in the form of TCP dump files. It includes various categories of cyberattacks, namely Probe, U2R (User to Root), R2L (Remote to Local), and Denial of Service (DoS). The dataset was gathered and distributed at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Lincoln laboratory [

16,

17]. For this work, the pre-separated subset having 10% of the complete data was used.

Table 1 summarizes the features of this dataset.

2.5. Classification algorithm

Random forest (RF) was used to train the NIDS with training data. It has been proving its efficiency time and again in achieving high classification performance in several applications across numerous domains [

18,

19]. RF is an ensemble of tree-structured classifiers that can work well with numerical and categorical data [

20].

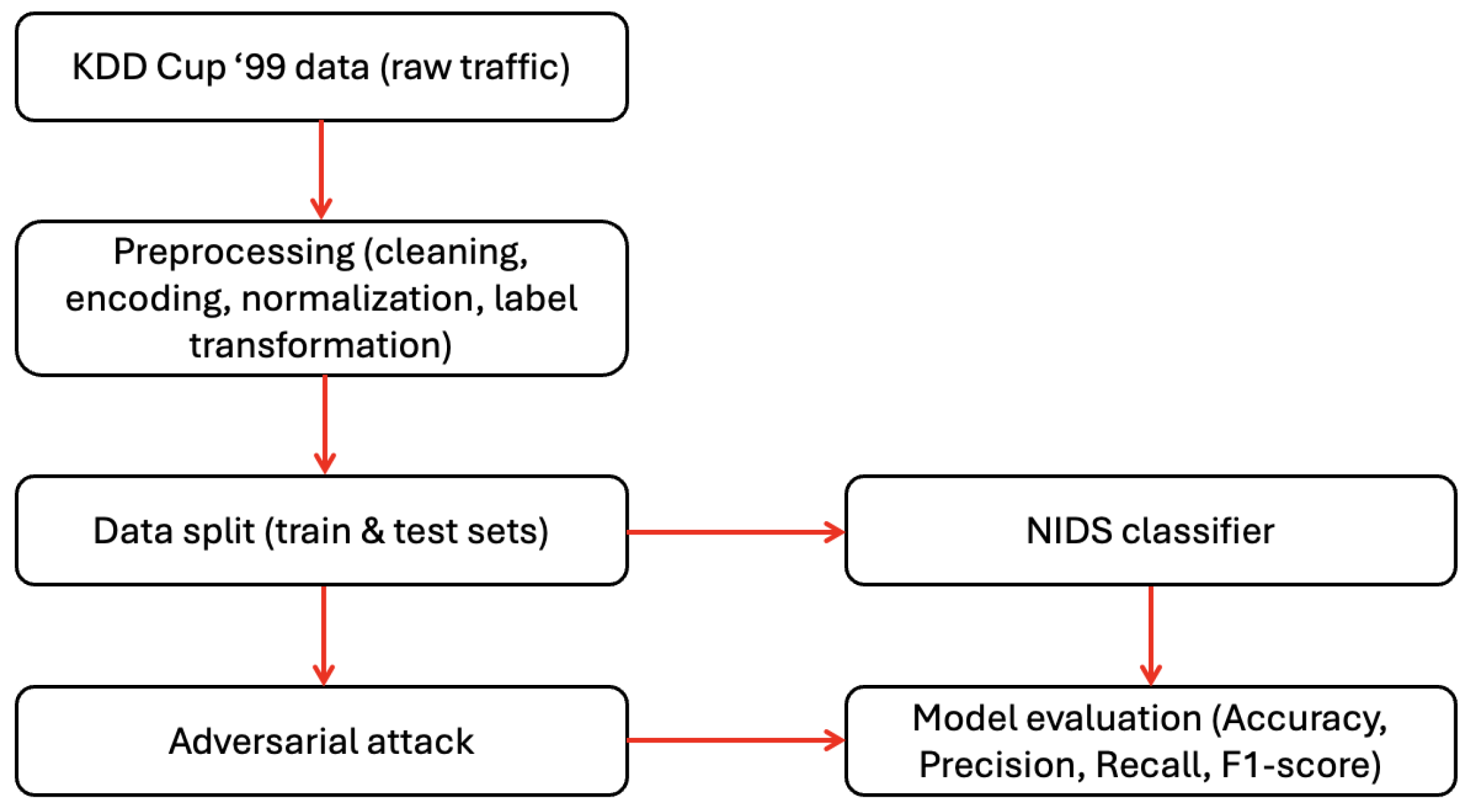

3. Architecture

Figure 1 shows a high-level design for the implemented workflow. Initially, raw network traffic data from the KDD Cup ’99 dataset was collected and subjected to preprocessing steps as described later in this section. The preprocessed dataset was then split into training and testing subsets. Then, a Network Intrusion Detection System (NIDS) classifier was trained on the training subset, and evaluated for its baseline performance with a fraction of test subset. The remaining fraction of the test set was used as input to adversarial algorithms to generate attack samples. To assess the robustness of the trained model, adversarial attack samples were introduced during adversarial evaluation of the model. Model performance was evaluated using standard metrics namely, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, to measure both detection effectiveness and resistance to adversarial manipulation. The following section describes the preprocessing applied to the dataset. The process remained the same for both adversarial attack scenarios.

4. Methodology

This section describes some of the important steps highlighted in the Architecture section.

4.1. Data preprocessing

To refine the raw network traffic and make it a cleaner and more structured version, the following steps were taken as part of data preprocessing.

Cleaning: Records with missing values were removed; redundant data, columns, and irrelevant fields were removed to improve data quality and model performance [

21].

Label transformation: KDD Cup ’99 dataset comprises a large collection of network connection records, each labeled as either normal or as belonging to one of several attack categories, including DoS, R2L, U2R, and Probe attacks [

22]. To simplify the classification task and align it with a binary intrusion detection scenario, we performed a label transformation. Specifically, all records labeled as attacks (i.e., any class other than normal) were grouped under a single label, "anomaly".

Encoding of categorical variables: Non-numeric fields such as protocol_type, service, and flag are converted into numerical representations using label encoding [

23], making them suitable for the model.

Normalization: Numerical features are scaled to a common range (e.g., [0, 1] or z-scores) to ensure uniform contribution across features during model training.

Dataset partitioning: The processed data is split into train and test subsets in the ratio of 70% and 30%, respectively.

4.2. RF classifier

The RF algorithm used to train the NIDS model is prominent in performing intrusion detection tasks where attack samples are often underrepresented compared to normal traffic.

Table 2 presents the hyperparameter configuration for the classifier.

The classifier was configured with 100 estimators (n_estimators=100), meaning it constructs an ensemble of 100 decision trees to enhance predictive performance and reduce overfitting. To ensure reproducibility and consistency of results, a fixed random_state value of 42 was used. Additionally, the class_weight parameter was set to ’balanced’ to address class imbalance issues inherent in network intrusion datasets. This adjustment automatically assigns higher weights to minority classes, thereby improving the classifier’s sensitivity to less frequent attack instances and contributing to a more equitable evaluation across all classes.

4.3. Adversarial attacks

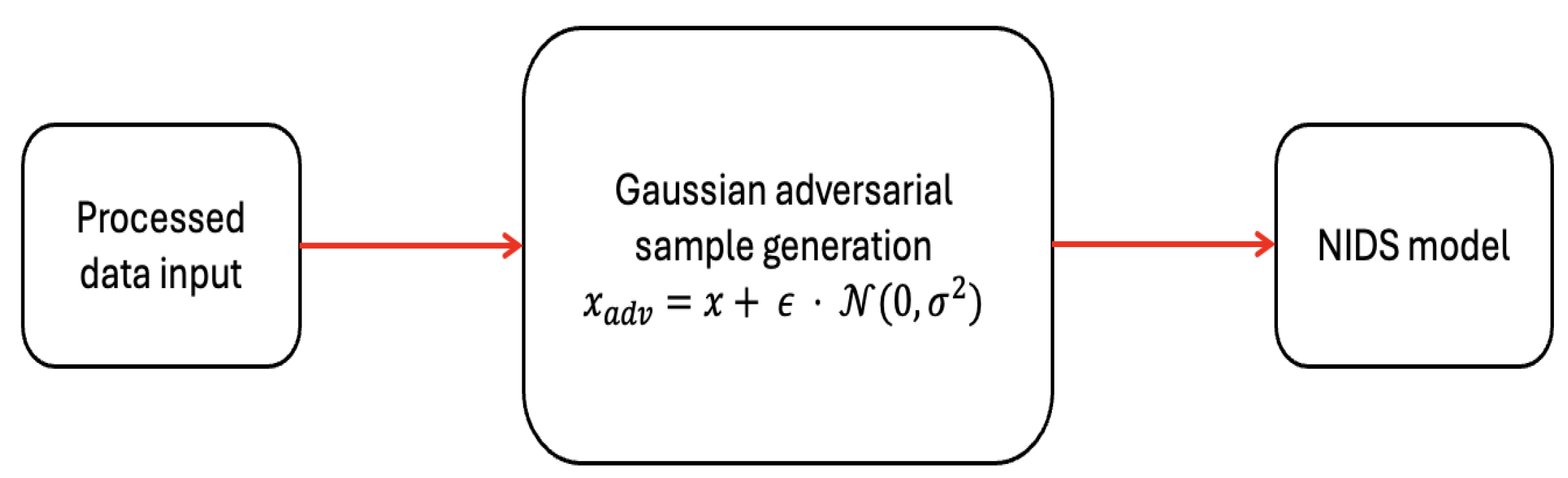

4.3.1. Gaussian method

For the implementation of Gaussian perturbation, a perturbation of

was chosen to control the noise intensity. This value was chosen to introduce minimal yet effective alterations to the input, ensuring that the perturbed samples remained close to the original data and within the feature space.

Figure 2 provides an outline of the workflow for this attack. A fraction of data from the test set is chosen as input to the Gaussian method. Each input from this subset is perturbed by adding Gaussian noise. This perturbed input is then fed into the classifier, which may misclassify it if the model is vulnerable to such perturbations. The evaluation of model’s performance is presented later in this paper.

4.4. Genetic algorithm

In this subsection, the attack configuration and workflow are discussed. The algorithm takes a sample of original data from the test set, and performs some key tasks as highlighted in Algorithm 1 below.

|

Algorithm 1:Adversarial data generation using Genetic Algorithm. |

-

Require:

, ,

-

Ensure:

Final adversarial population P

- 1:

Initialize population

- 2:

for to do

- 3:

for each do

- 4:

Compute fitness:

- 5:

end for

- 6:

Select top k individuals with lowest :

- 7:

Initialize offspring pool:

- 8:

for to do

- 9:

Randomly select

- 10:

Perform crossover:

- 11:

if then

- 12:

Mutate: , where

- 13:

end if

- 14:

Add to offspring:

- 15:

end for

- 16:

Form new population:

- 17:

end for - 18:

return Final population

|

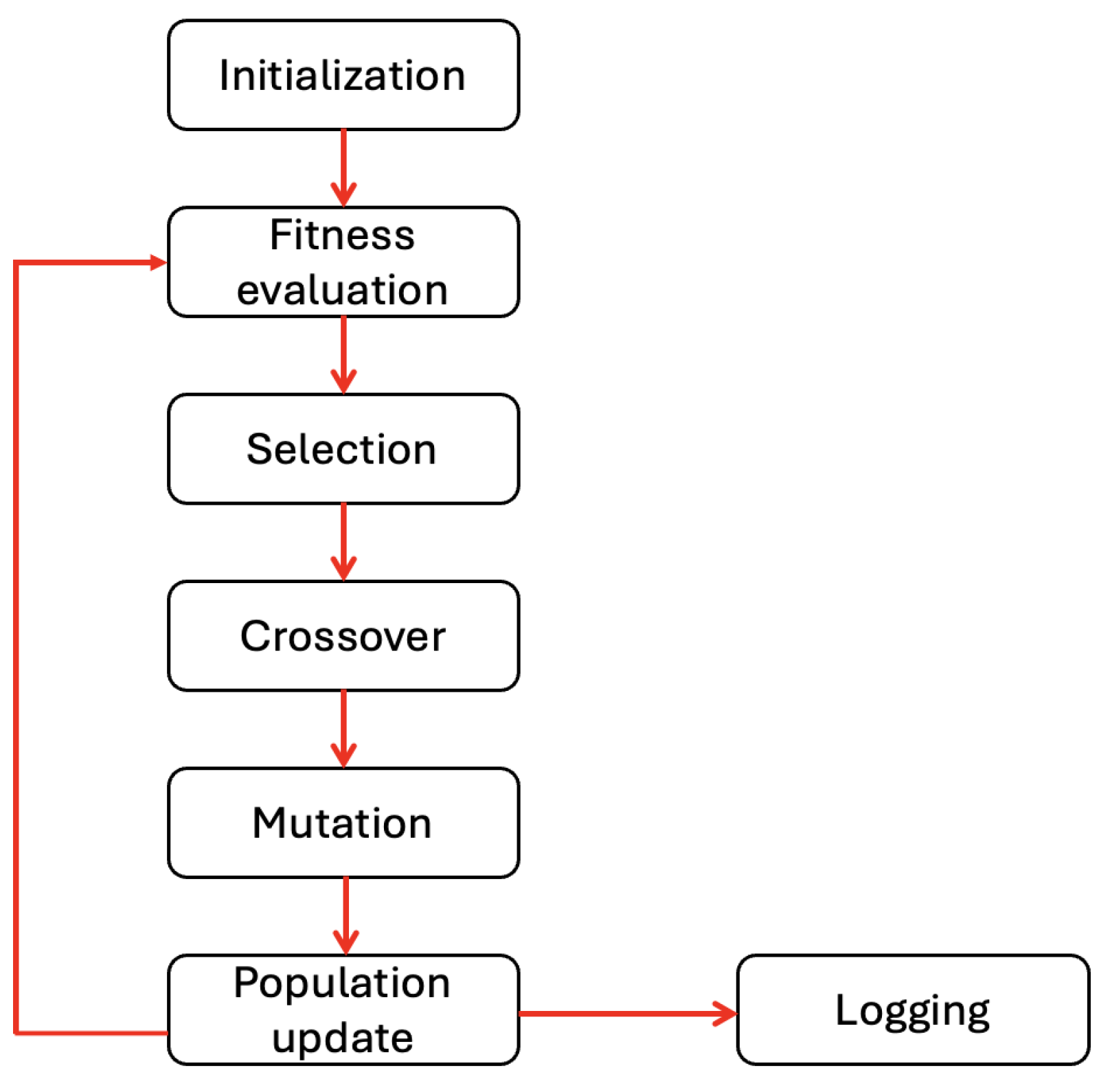

The methodology and some of the attack configurations are explained below.

Population size: The algorithm starts by initializing a population of adversarial candidates using the input data. The population size is defined by the parameter, which controls the diversity of candidate solutions. The was set to 20, meaning, 20 individuals are evaluated at each step. Larger population can enhance the diversity, but requires higher computational abilities.

Number of generations: The parameter controls how many times the population will evolve. A value of 30 was set during our experimentation as it would ensure sufficient number of iterations to refine the population and produce potent adversarial examples.

Mutation rate: The parameter determines the probability of randomly altering an offspring. For instance, a value of 0.1 (i.e., 10%) means that roughly one in ten new individuals will undergo mutation. This helps maintain diversity and avoid local minima.

Fitness evaluation: Each individual in the population is assessed using a , which measures how effectively the perturbed input causes misclassification. In our implementaion, the individuals with the least fitness scores are considered most adversarial.

Selection strategy: The algorithm uses fitness based ranking to selection the top individuals from the current generation to serve as parents for the next. This ensures that the strongest traits are propagated forward.

Crossover mechanism: New offspring are generated by combining features from two randomly selected parents using a function. This simulates genetic recombination, enabling the emergence of new patterns.

Mutation operation: After crossover, offspring may be modified by a function with the probability defined by . This step introduces novel variations and prevents premature convergence.

Population update: The next generation is formed by stacking the selected parents with the new offspring.

Logging: At each generation, we log the most desirable fitness scores, to monitor the optimization progress over time.

Figure 3 outlines the GA methodology implemented in our experimentation.

5. Results

The results obtained from Gaussian perturbation and genetic algorithm are separately presented and discussed in this section.

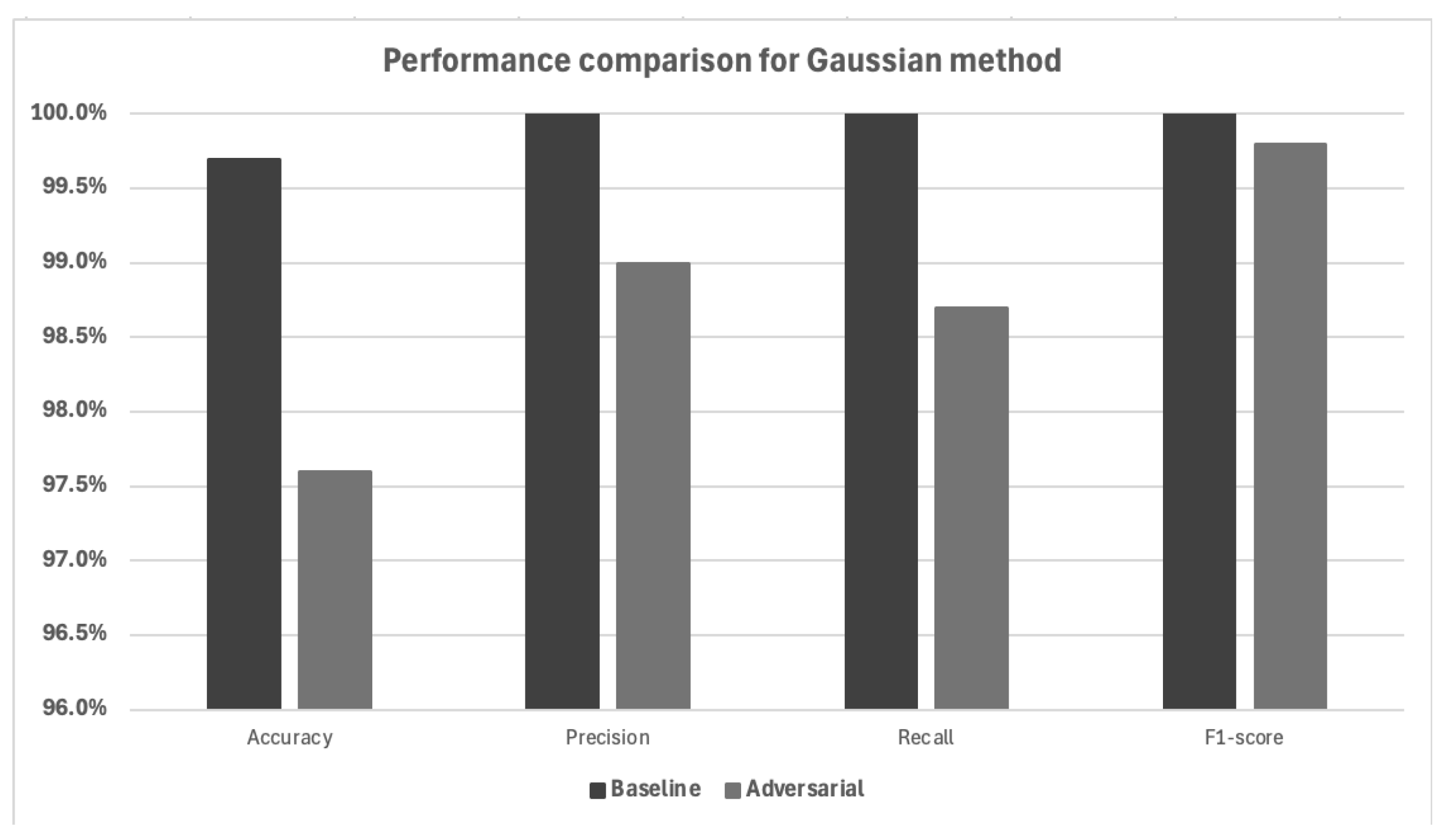

5.1. Gaussian perturbation

Figure 4 presents a comparative analysis of the model’s performance under baseline and adversarial conditions, where adversarial samples were generated using the Gaussian perturbation method. The values presented are the averages of five rounds of testing. The performance metrics used for evaluation were Accuracy, F1-score, Precision, and Recall. Accuracy alone is not a reliable metric for evaluating model performance due to the inherent class imbalance in the KDD dataset. Specifically, the dataset contains a disproportionately higher number of attack instances compared to normal traffic, which can lead to misleadingly high accuracy values even if the model performs poorly on the minority class.

As can be seen in

Figure 4, the model’s accuracy dropped from baseline 99.7% to about 97.6% under the adversarial attack. Although the 2% reduction highlights the vulnerability of the model to seemingly small, stochastic perturbations applied to the input features, it emphasizes the resistance of the model to this attack.

Precision, which measures the ability of the model to correctly identify positive cases, decreased from 100% to around 99.0%. This indicates that some adversarial samples were incorrectly classified as positive, slightly increasing the false positive rate.

The recall saw a more significant decline from baseline 100% to 98.7%, suggesting that the model failed to correctly identify some proportion of actual positive instances in the presence of adversarial perturbations.

The F1-score, which represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall, dropped from a baseline of 100% to approximately 99.8%.

5.2. Genetic algorithm

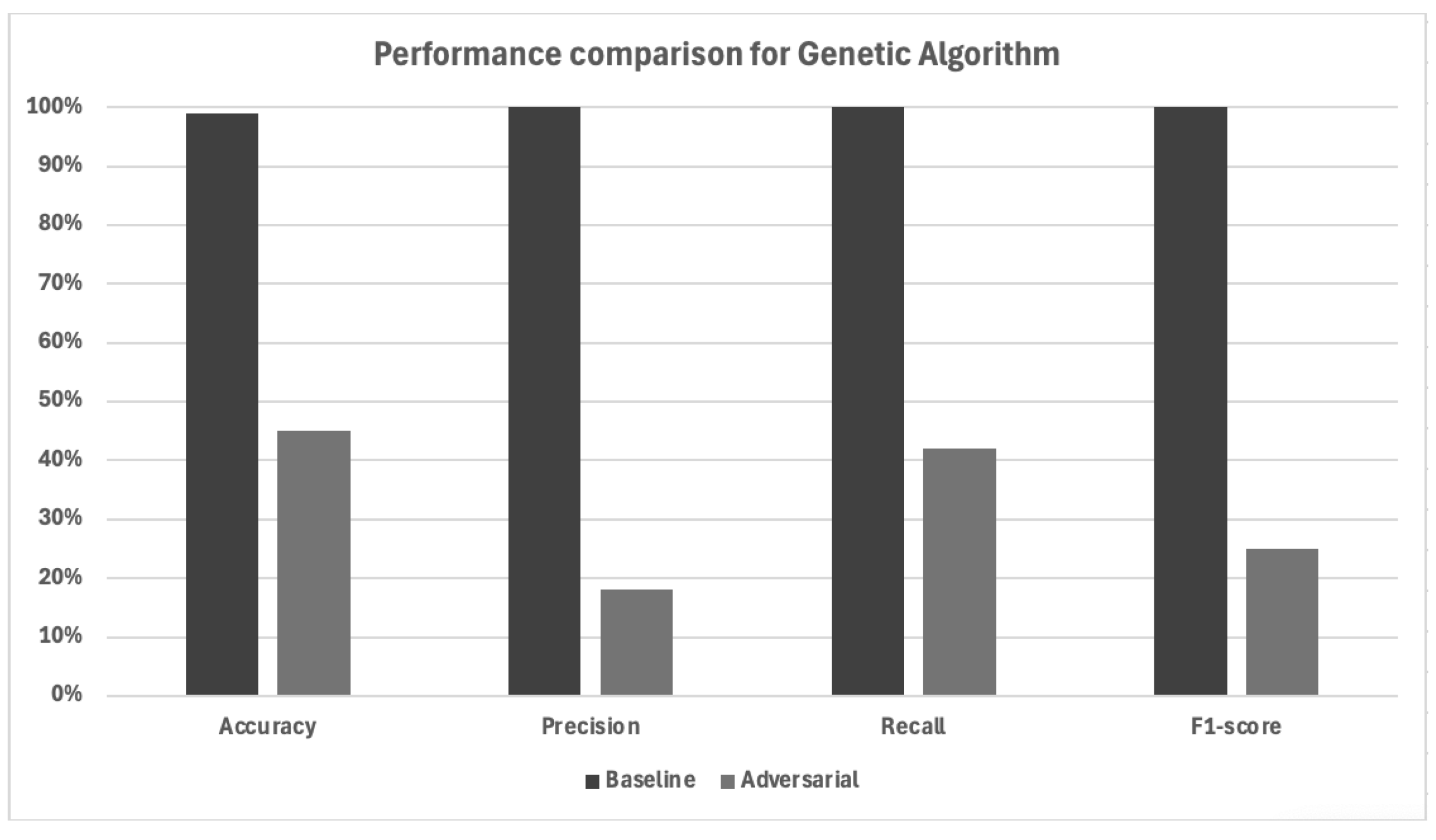

Figure 5 presents a comparative analysis of classification performance metrics under baseline and adversarial conditions generated using the Genetic Algorithm (GA). The figure clearly illustrates the substantial decline in model performance when exposed to adversarially crafted inputs, demonstrating the algorithm’s efficacy in compromising the network intrusion detection system (NIDS).

For both attack scenarios, the same test data sample was used, excluding certain features — such as , , and — from perturbation. Both the Gaussian and GA methods targeted a total of 29 features, with around 12 of them experiencing more significant perturbations under the influence of GA.

6. Discussion

When comparing the two adversarial perturbation techniques, a stark contrast emerges in both the strategy of perturbation and its resulting impact on model performance. Notably, the Gaussian method perturbed 100% of the input samples used for adversarial data generation, applying slight noise uniformly across the dataset. Despite its broad coverage, the reduction in performance metrics remained relatively moderate, with baseline metrics declining by only a few percentage points. In contrast, the genetic algorithm perturbed merely 20% of the data, focusing on a selective set of inputs with higher optimization for evading detection. Interestingly, this smaller subset had a significantly more destructive effect on the model, reducing accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score by over 50% in some cases. This highlights the effectiveness of targeted perturbations over uniform noise in adversarial machine learning. However, it is important to recognize the limitations of the KDD dataset used in this study. As an older benchmark dataset, it reflects network behaviors and attack signatures from a previous era and lacks the diversity and complexity of modern network traffic. Consequently, while the results underline the critical need for adversarial robustness, they also call for the use of more contemporary and realistic datasets in future studies.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

This study presented a comparative analysis of two adversarial attack techniques — Gaussian perturbation and genetic algorithm — to evaluate the robustness of ML-based NIDS using the KDD Cup ’99 dataset. Both methods were implemented to generate adversarial samples by perturbing selected features in the dataset while deliberately excluding categorical and/or functional features including , , , , , and to maintain semantic consistency.

The Gaussian perturbation method demonstrated its simplistic nature by perturbing 100% of the selected test data, leading to a slight degradation in classification performance, with relatively small perturbation strengths () and less computational requirements. In contrast, the genetic algorithm selectively modified only 20% of the data but achieved significantly high deception through optimization-driven feature selection, making the attack more efficient in terms of the number of changes required, with a downside of relatively more computational demands.

The experimental findings highlight the vulnerability of traditional NIDS models to adversarial attacks, particularly when trained on outdated datasets like KDD Cup ’99. The dataset’s limited representation of modern network behavior, coupled with its inherent class imbalance, contributed to the observed performance degradation under adversarial conditions. These results underscore the need for more resilient detection models and the adoption of more contemporary and realistic datasets in the evaluation of intrusion detection systems.

Future work will proceed in multiple directions, including the exploration of hybrid adversarial strategies, evaluation of their impact on NIDS models using modern and diverse datasets, and, importantly, the enhancement of adversarial robustness in NIDS solutions for real-world deployment scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.; methodology, M.P. and M.M.; software, M.M.; validation, M.P. and M.M.; formal analysis, M.P. and M.M.; investigation, M.P. and M.M.; data curation, M.P. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, M.P.; visualization, M.P.; supervision, M.P. and S.B.; project administration, M.P. and S.B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NIDS |

Network Intrusion Detection System |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| AML |

Adversarial Machine Learning |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithm |

| KDD |

Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining |

| DARPA |

Defense Advanced Research Project Agency |

| LAN |

Local Area Network |

| U2R |

User to Root |

| R2L |

Remote to Local |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| MIT |

Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| DoS |

Denial of Service |

References

- Elham Tabassi, Kevin J. Burns, M.H.A.D.M.M.J.T.S. A Taxonomy and Terminology of Adversarial Machine Learning. Technical report, National Institute of Standards and Technology, 19. 20 October.

- Alatwi, H.A.; Morisset, C. Adversarial machine learning in network intrusion detection domain: A systematic review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.03315, arXiv:2112.03315 2021.

- Biggio, B.; Roli, F. Wild patterns: Ten years after the rise of adversarial machine learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 2018, pp.

- Rosenberg, I.; Shabtai, A.; Elovici, Y.; Rokach, L. Adversarial machine learning attacks and defense methods in the cyber security domain. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajjar, E.; Maxwell, P.; Bastian, N. Adversarial machine learning in network intrusion detection systems. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 186, 115782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Shi, Y.; Xue, Z. Idsgan: Generative adversarial networks for attack generation against intrusion detection. In Proceedings of the Pacific-asia conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. Springer; 2022; pp. 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Apruzzese, G.; Andreolini, M.; Ferretti, L.; Marchetti, M.; Colajanni, M. Modeling realistic adversarial attacks against network intrusion detection systems. Digital Threats: Research and Practice (DTRAP) 2022, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.J.; Lin, C.H.R.; Lin, Y.C.; Tung, K.Y. Intrusion detection system: A comprehensive review. Journal of network and computer applications 2013, 36, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassi, E.; Burns, K.J.; Hadjimichael, M.; Molina-Markham, A.D.; Sexton, J.T. A taxonomy and terminology of adversarial machine learning. NIST IR 2019, 2019, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Draper-Gil, G.; Lashkari, A.H.; Mamun, M.S.I.; Ghorbani, A.A. Characterization of encrypted and vpn traffic using time-related. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on information systems security and privacy (ICISSP), 2016, pp.

- Sommer, R.; Paxson, V. Outside the closed world: On using machine learning for network intrusion detection. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE symposium on security and privacy. IEEE; 2010; pp. 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlicki, M.; Choraś, M.; Kozik, R. Defending network intrusion detection systems against adversarial evasion attacks. Future Generation Computer Systems 2020, 110, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujari, M.; Sun, W. Fortifying Machine Learning-Powered Intrusion Detection: A Defense Strategy Against Adversarial Black-Box Attacks. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Information and Communication Technology. Springer; 2024; pp. 655–671. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, N.; Cruz, J.M.; Cruz, T.; Abreu, P.H. Adversarial machine learning applied to intrusion and malware scenarios: a systematic review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 35403–35419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartz-Beielstein, T.; Branke, J.; Mehnen, J.; Mersmann, O. Evolutionary algorithms. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2014, 4, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protić, D.D. Review of KDD Cup ‘99, NSL-KDD and Kyoto 2006+ datasets. Vojnotehnički glasnik/Military Technical Courier 2018, 66, 580–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.K.; Naahid, S. Analysis of KDD CUP 99 dataset using clustering based data mining. International Journal of Database Theory and Application 2013, 6, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiu, M.; Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS journal of photogrammetry and remote sensing 2016, 114, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujari, M.; Cherukuri, B.P.; Javaid, A.Y.; Sun, W. An approach to improve the robustness of machine learning based intrusion detection system models against the carlini-wagner attack. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR). IEEE; 2022; pp. 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, A.; Kolhe, S.; Kamal, R. An improved random forest classifier for multi-class classification. Information Processing in Agriculture 2016, 3, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, A.; Di Lecce, V. Data preprocessing impact on machine learning algorithm performance. Open Computer Science 2023, 13, 20220278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, K.; Akhtar, Z.; Khan, F.A.; Kim, Y. KDD cup 99 data sets: A perspective on the role of data sets in network intrusion detection research. Computer 2019, 52, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Xue, Z.Y.; Aamodt, T.M. Label encoding for regression networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.01927, arXiv:2212.01927 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).