3.1. Hardware abstraction layer

Optimizing the code execution time and having consistency in this execution requires quick and easy access to the microcontroller’s registers. To do his, we have skipped using the open-source libraries available from the manufacturer (i.e., STM32Cube MCU Packages) and developed a hardware abstraction layer (HAL) to access the most common microcontroller modules like the clock system, the GPIOs, the timers, the communication interfaces, the flash, and ADCs and DACs. The HAL defines standard function headers with the implementation varying from one microcontroller to another and allows for an easy code porting to another hardware platform if needed. The application layer calls these standard functions to configure and use the physical layer of the microcontroller.

The HAL uses the device descriptions to access the microcontroller registers that follow the Common Microcontroller Software Interface Standard (CMSIS) which is an Arm-maintained, vendor-independent software framework that standardizes how code, tools and device descriptions interact with Arm Cortex-based microcontrollers. The goal is to let the user focus on the application instead of relearning low-level details for every new microcontroller. Each module has its registers part of a structure as the one given below as for example, the GPIO module. CMSIS has all microcontroller registers defined as volatile and using the standard C99 data types for interoperability.

typedef struct

{

__IO uint32_t MODER; /*!< GPIO port mode register, Address offset: 0x00 */

__IO uint32_t OTYPER; /*!< GPIO port output type register, Address offset: 0x04 */

__IO uint32_t OSPEEDR; /*!< GPIO port output speed register, Address offset: 0x08 */

__IO uint32_t PUPDR; /*!< GPIO port pull-up/pull-down register, Address offset: 0x0C */

__IO uint32_t IDR; /*!< GPIO port input data register, Address offset: 0x10 */

__IO uint32_t ODR; /*!< GPIO port output data register, Address offset: 0x14 */

__IO uint32_t BSRR; /*!< GPIO port bit set/reset register, Address offset: 0x18 */

__IO uint32_t LCKR; /*!< GPIO port configuration lock register, Address offset: 0x1C */

__IO uint32_t AFR[

2]; /*!< GPIO alternate function registers, Address offset: 0x20-0x24 */

__IO uint32_t BRR; /*!< GPIO Bit Reset register, Address offset: 0x28 */

__IO uint32_t ASCR; /*!< GPIO analog switch control register, Address offset: 0x2C */

} GPIO_TypeDef;

Each microcontroller module is then defined as a pointer to a structure that points to the module’s fixed RAM address, as for example the first GPIO module named GPIOA:

#define GPIOA ((GPIO_TypeDef *) GPIOA_BASE), with GPIOA_BASE being defined as the base address for the module. Using this structure, we have defined functions to configure and access the functionality of each module. The example given below sets the state for a microcontroller pin, given as the function parameters (port and pin) controlled by a GPIO module and uses the same standard data types as the ones used by CMSIS. The code also follows the MISRA C [

15] coding guidelines to make safety- and security-critical embedded software safe, secure, portable and reliable, and is annotated according to Doxygen [

16] which can be used to automatically generate code documentation.

/**************************************************************************************************

* @author Andrei Rusu

* @brief GPIO port/pin write

* @param[in] p_ucModule - the GPIO module (e.g. HAL_GPIO_0)

* @param[in] p_ucPin - the GPIO pin (e.g. HAL_GPIO_PIN_0)

* @param[in] p_ucState - the GPIO state (e.g. HAL_GPIO_LOW)

* @remarks

**************************************************************************************************/

void HAL_GPIO_Write(uint8_t p_ucModule, uint8_t p_ucPin, uint8_t p_ucState)

{

switch (p_ucState)

{

case HAL_GPIO_LOW:

{

g_apstHAL_GPIO[p_ucModule]->BSRR = (uint32_t) (1 << (p_ucPin) << 16);

break;

}

case HAL_GPIO_HIGH:

{

g_apstHAL_GPIO[p_ucModule]->BSRR = (uint32_t) (1 << p_ucPin);

break;

}

case HAL_GPIO_TOGGLE:

{

g_apstHAL_GPIO[p_ucModule]->ODR ^= (uint32_t) (1 << p_ucPin);

break;

}

case HAL_GPIO_PULSE:

{

g_apstHAL_GPIO[p_ucModule]->ODR ^= (uint32_t) (1 << p_ucPin);

g_apstHAL_GPIO[p_ucModule]->ODR ^= (uint32_t) (1 << p_ucPin);

break;

}

default: break;

}

}

CMSIS also uses a standard way to define the register bits. This is also adopted in the device definition files available from the manufacturer. As an example, we have listed below a section of the bit definitions for the GPIO_MODER register.

/****************** Bits definition for GPIO_MODER register *****************/

#define GPIO_MODER_MODE0_Pos (0U)

#define GPIO_MODER_MODE0_Msk (0x3UL << GPIO_MODER_MODE0_Pos) /*!< 0x00000003 */

#define GPIO_MODER_MODE0 GPIO_MODER_MODE0_Msk

#define GPIO_MODER_MODE0_0 (0x1UL << GPIO_MODER_MODE0_Pos) /*!< 0x00000001 */

#define GPIO_MODER_MODE0_1 (0x2UL << GPIO_MODER_MODE0_Pos) /*!< 0x00000002 */

The HAL can be made available as source and header files or can be packed in a binary library for easy maintenance and giving the user access just to the header files to call the functions. As a library, it can be easily used in new projects simplifying the overall project structure. We have also defined an intermediate layer between the physical and application layers to configure the microcontroller modules and populate the module interrupt callback functions, which avoids adding application layer code in the HAL files.

3.2. Transceiver driver

To maintain consistency throughout the software project in terms of register access, we have followed the CMSIS guidelines also for the transceiver driver. This meant putting in place the bit definitions for each transceiver register, like the ones available for the microcontroller. As an example, we have listed below a part of the bit definitions for the TRX_CTRL_0 register defining the clock rate for the CLKM pin.

/****************** Address definition for TRX_CTRL_0 register *******************/

#define TRX_CTRL_0 0x03

/****************** Bit definition for TRX_CTRL_0 register *******************/

#define TRX_CTRL_0_CLKM_CTRL_Pos (0U)

#define TRX_CTRL_0_CLKM_CTRL_Msk (0x7UL << TRX_CTRL_0_IRQ_POLARITY_Pos)

#define TRX_CTRL_0_CLKM_CTRL TRX_CTRL_0_IRQ_POLARITY_Msk

#define TRX_CTRL_0_CLKM_CTRL_NO_CLOCK (0x0UL << TRX_CTRL_0_IRQ_POLARITY_Pos)

#define TRX_CTRL_0_CLKM_CTRL_1MHz (0x1UL << TRX_CTRL_0_IRQ_POLARITY_Pos)

#define TRX_CTRL_0_CLKM_CTRL_2MHz (0x2UL << TRX_CTRL_0_IRQ_POLARITY_Pos)

#define TRX_CTRL_0_CLKM_CTRL_4MHz (0x3UL << TRX_CTRL_0_IRQ_POLARITY_Pos)

#define TRX_CTRL_0_CLKM_CTRL_8MHz (0x4UL << TRX_CTRL_0_IRQ_POLARITY_Pos)

#define TRX_CTRL_0_CLKM_CTRL_16MHz (0x5UL << TRX_CTRL_0_IRQ_POLARITY_Pos)

#define TRX_CTRL_0_CLKM_CTRL_250kHz (0x6UL << TRX_CTRL_0_IRQ_POLARITY_Pos)

#define TRX_CTRL_0_CLKM_CTRL_IEEE_802_15_4 (0x7UL << TRX_CTRL_0_IRQ_POLARITY_Pos)

Functions were then defined and implemented to access the transceiver’s features like reading and writing registers, reading frames from and writing frames to the internal FIFO, setting the transceiver in different states (idle, transmission and reception) and using the internal AES module to encrypt data.

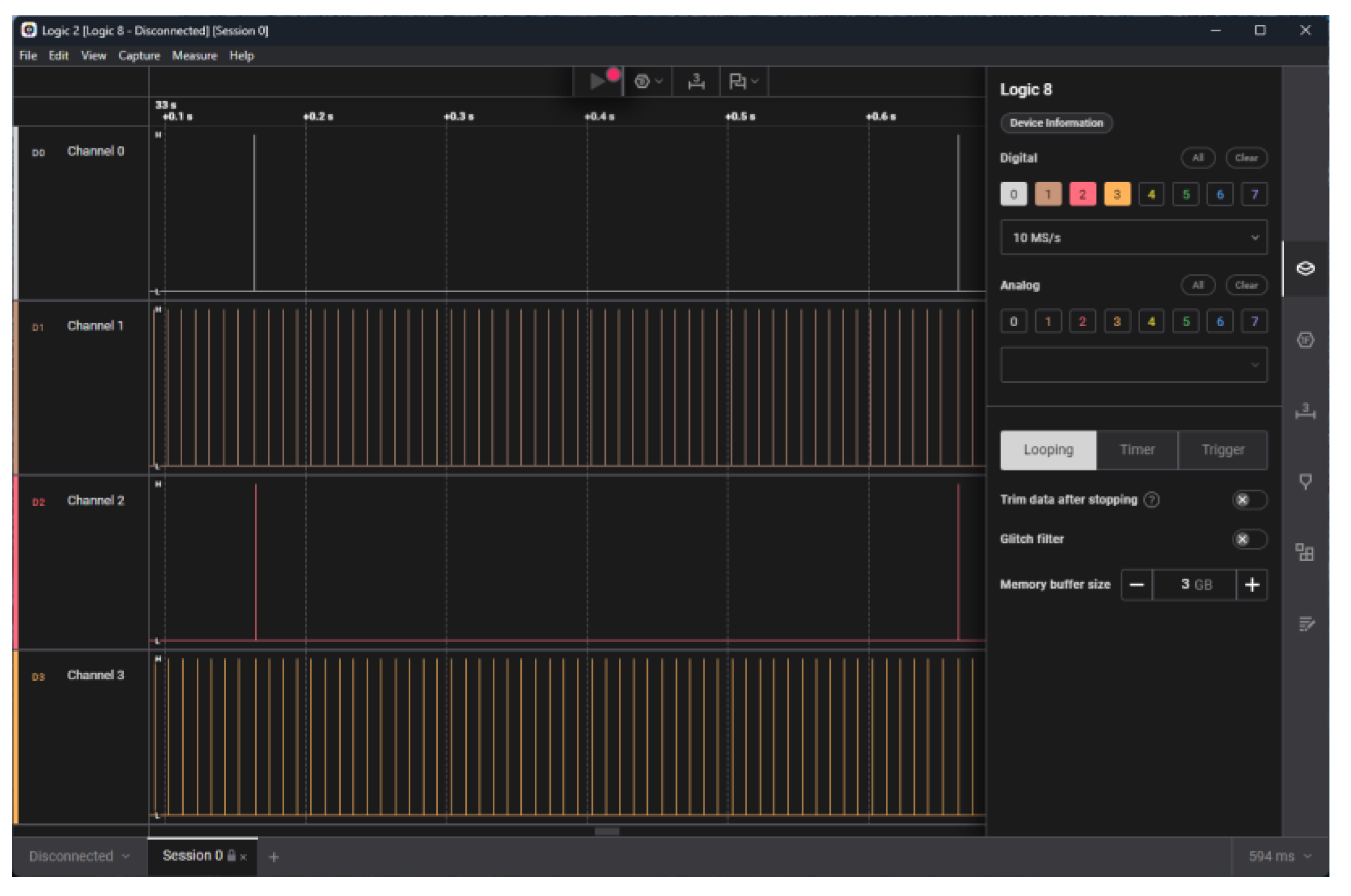

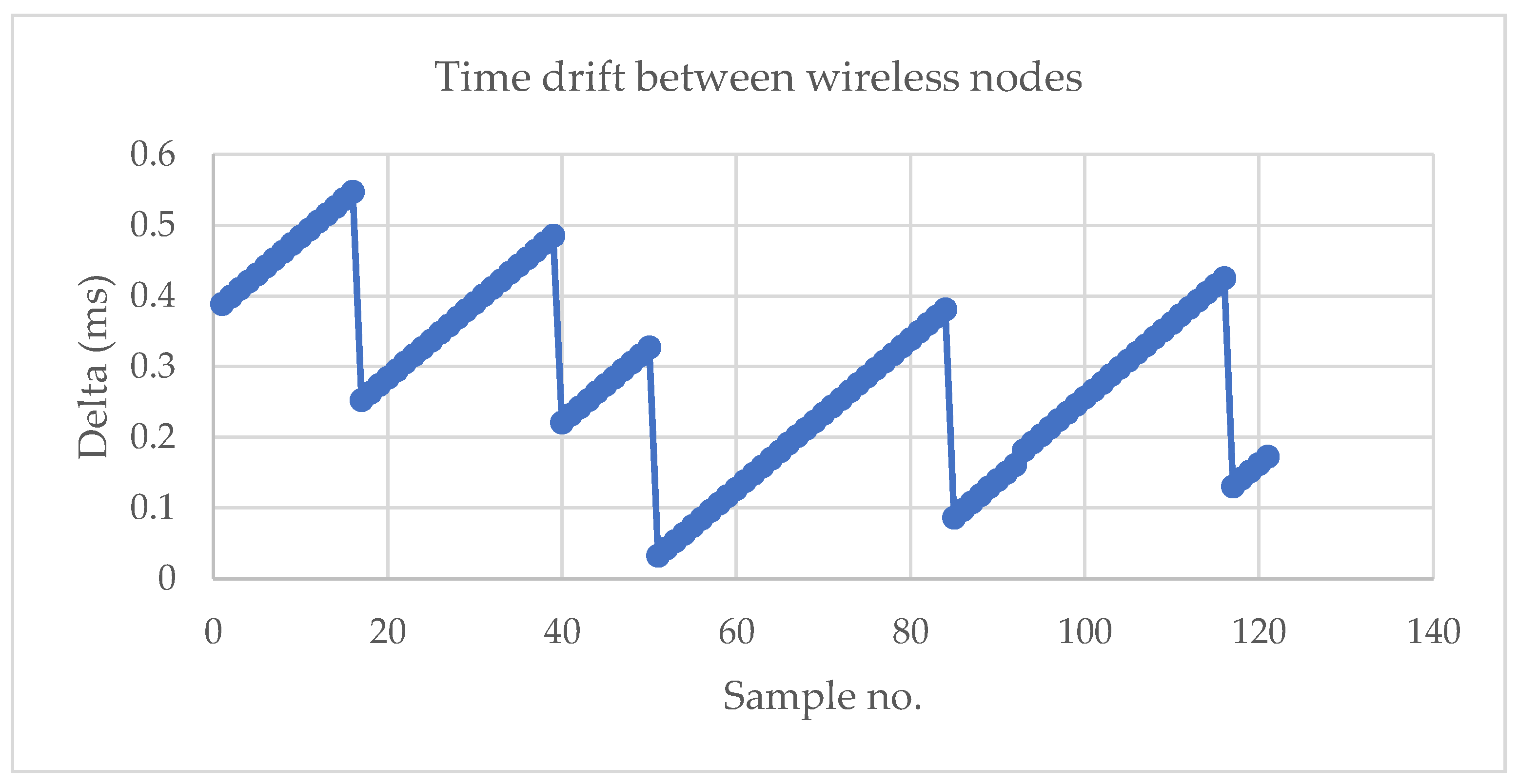

3.3. Division of time

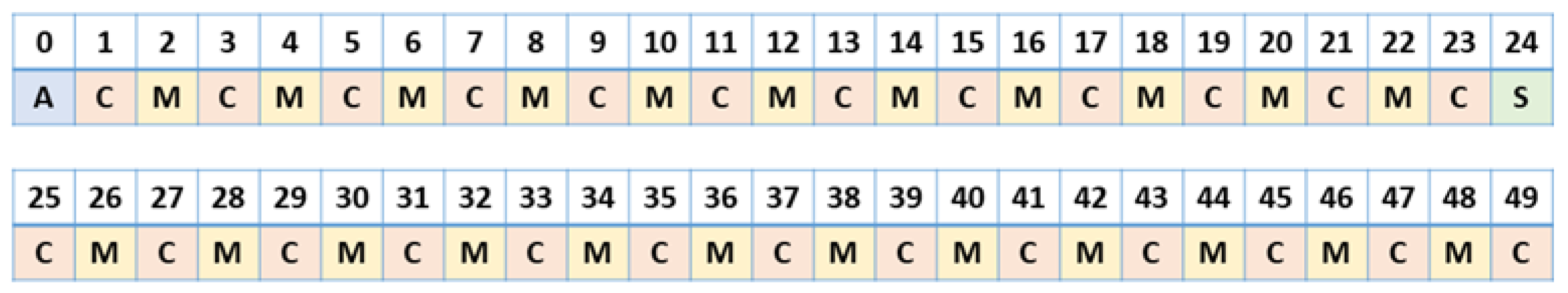

The overall aim of the time management algorithm is to achieve a sub-millisecond time drift between any two nodes associated to the wireless network. Why is this needed? If we look at classic control loop, sending a delayed command will cause instability in the controlled process, especially in fast ones. Furthermore, keeping this time drift is in line with the timeslot template defined by IEEE 802.15.4 when using the TSCH operating mode. Considering the COTS development boards used in this experiment and the ±20ppm frequency drift on-board crystals we have fixed the slot frame at 6000 timeslots of 10 milliseconds each leading to a 1-minute-long slot frame. This will lead to a theoretical maximum time drift less than 40ppm x 6000 slots = 2.4 milliseconds per slot frame, assuming one oscillator drifts forward and the other backward. To achieve a sub-millisecond drift between any two nodes, we have concluded to divide the slot frame into groups of 50 timeslots as shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The group of timeslots.

Figure 1.

The group of timeslots.

Figure 2.

The timeslot template.

Figure 2.

The timeslot template.

The first timeslot in the group of 50, or timeslot 0 marked with A, is an advertisement timeslot. During this timeslot, the network coordinator (the clock source) sends a beacon frame over the wireless network to notify other wireless devices of the network’s presence. The beacon frame also includes information about the exact time when the coordinator transmitted the frame. Odd timeslots are control timeslots, marked with C, used in control loops to transmit data frames containing commands and process output measurements. Even timeslots are management timeslots, marked with M, used by the coordinator to pass settings to wireless devices, as well as by wireless devices to pass data to the coordinator. Shared timeslots, marked with S, are used by all wireless nodes participating in the network to transmit frames when they do not yet have assigned timeslots. These timeslots are used in procedures such as associating a wireless device with the network, where the last step is to allocate dedicated timeslots. The 25th timeslot in the group of 50 will always be the shared timeslot. In a slot frame, there are 120 advertisement timeslots, 2760 management timeslots, 3000 control timeslots, and 120 shared timeslots.

We have chosen to send an enhanced beacon frame as defined by IEEE 802.15.4, during the advertisement timeslot as it allows the insertion of user payload. This 5-byte payload contains information related to the current network coordinator time: the UTC time in seconds and the time fraction – the timeslot group number, from 0 to 119. As the enhanced beacon frame is being sent during the advertisement timeslot at the moment specified in the timeslot template, a device joining or joined to the network knows the precise absolute time at which the enhanced beacon frame was sent.

3.4. Time synchronization

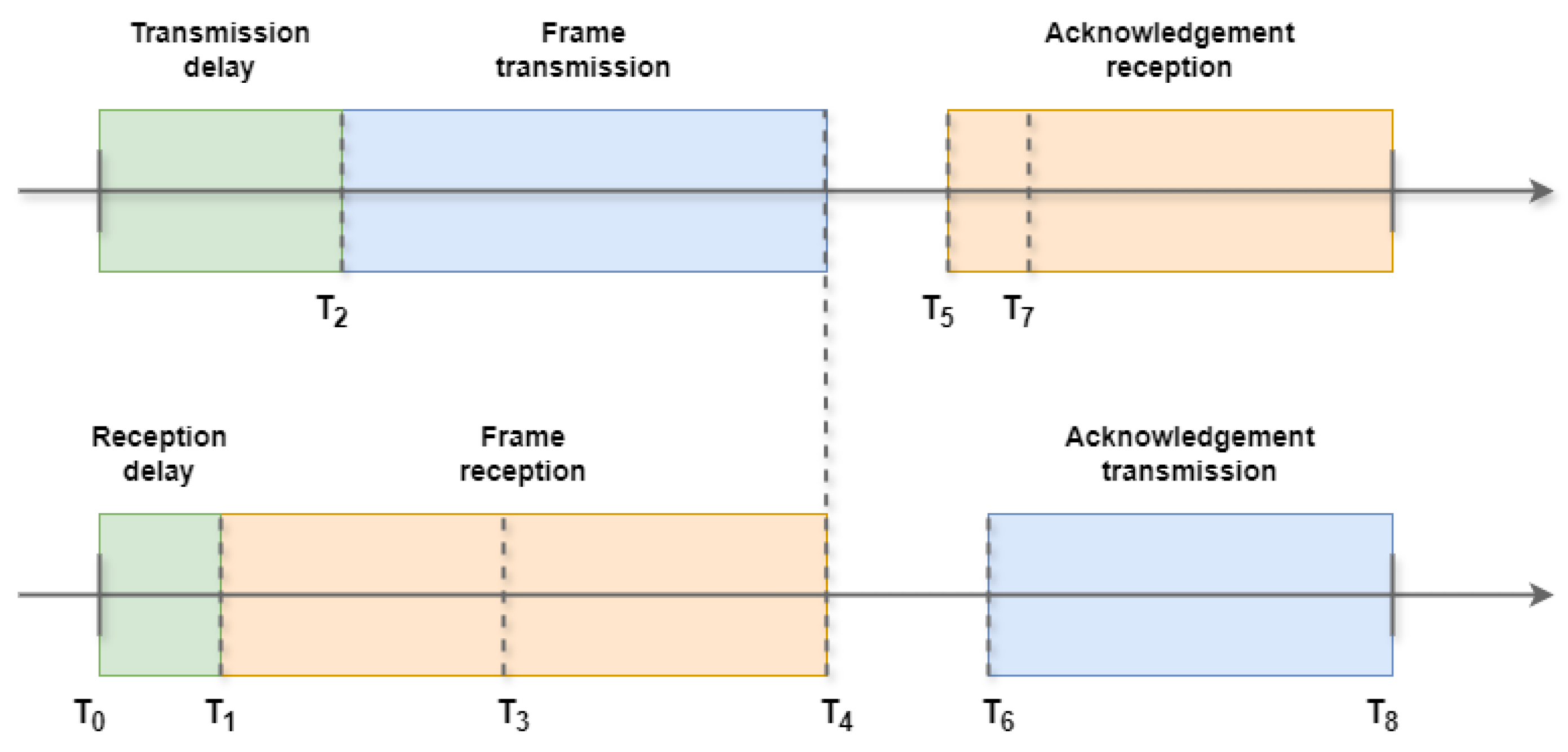

The IEEE 802.15.4 standard defines a timing template (macTimeslotTemplate) that must be followed by every transmission and reception over wireless. Figure 14 illustrates a two-way communication between two wireless devices, the first being the initiator of communication.

A timeslot is defined as the interval between T0 and T8, with a standard duration of 10 milliseconds. According to the transmission template, the actual data frame transmission commences at T2, which, as per the standard, is 2120 microseconds from the start of the timeslot. To ensure correct reception, the second wireless device will enter reception mode earlier, specifically at T1, which is 1020 microseconds from the beginning of the timeslot. The device will then wait for the interval between T3 and T1 for the transmission to begin, i.e., 2200 microseconds. The moment T4 signals the completion of the data frame’s transmission/reception. Subsequently, the receiving device will send an acknowledgment frame to the transmitting device exactly after T6 - T4, which is 1000 microseconds. The first device will enter reception mode at T5 and wait for the acknowledgment frame’s transmission until T7. The end of the transmit/receive process for the acknowledgment frame and the conclusion of bidirectional communication are marked by T8.

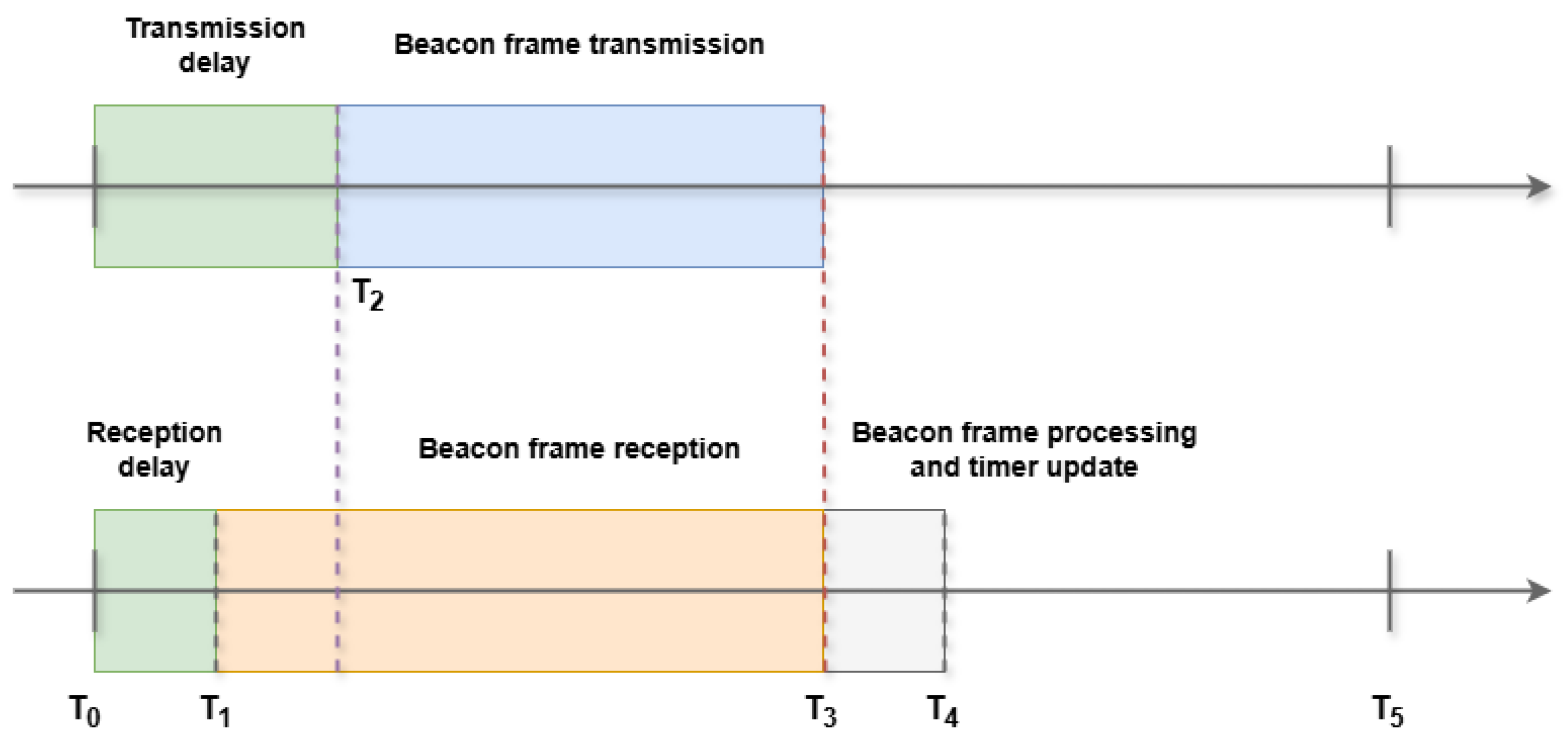

Strict adherence to the transmission and reception pattern is essential for the proper functioning of the wireless network, particularly in the time synchronization between wireless nodes. Time synchronization occurs between the network coordinator, which acts as the time source, and each wireless node associated with the network. For this purpose, the enhanced beacon frame is used, which the coordinator transmits in the first timeslot of the group of 50 timeslots. Figure 15 illustrates a synchronization procedure between two wireless nodes, with the top one being the network coordinator and the bottom one being a wireless node that is associated with or joining the network.

Figure 3.

The synchronization procedure

Figure 3.

The synchronization procedure

At time T1, the wireless device enters receive mode and awaits the transmission of the beacon data frame. At time T2, in accordance with the transmit and receive template, the coordinator initiates the transmission of the enhanced beacon frame. By time T3, the coordinator has completed the transmission, and concurrently, the wireless device completes its reception of the frame. Subsequently, the device processes the frame by extracting time-related information, including the slot frame, the time and the specific fraction of time when the transmission started. At time T4, the wireless device updates its timeslot and timeslot group timers. Consequently, at time T5, the wireless device will generate an interrupt to indicate the commencement of the next timeslot, thereby maintaining synchronization with the network coordinator.

Synchronization precision remains a key challenge in WSNs. [

17] demonstrated how hardware-assisted timestamping and drift correction can enhance accuracy with inexpensive hardware. Similarly, the LPSS protocol [

18] achieves energy-efficient scheduling and synchronization by minimizing communication overhead and allocating distinct sync slots to reference nodes. In [

19] they also proposed a lightweight approach (SA-MAC) that reduces sync-related traffic. Our work builds on these by integrating deterministic time division with beacon-based alignment and minimal protocol overhead.