Submitted:

14 May 2025

Posted:

15 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

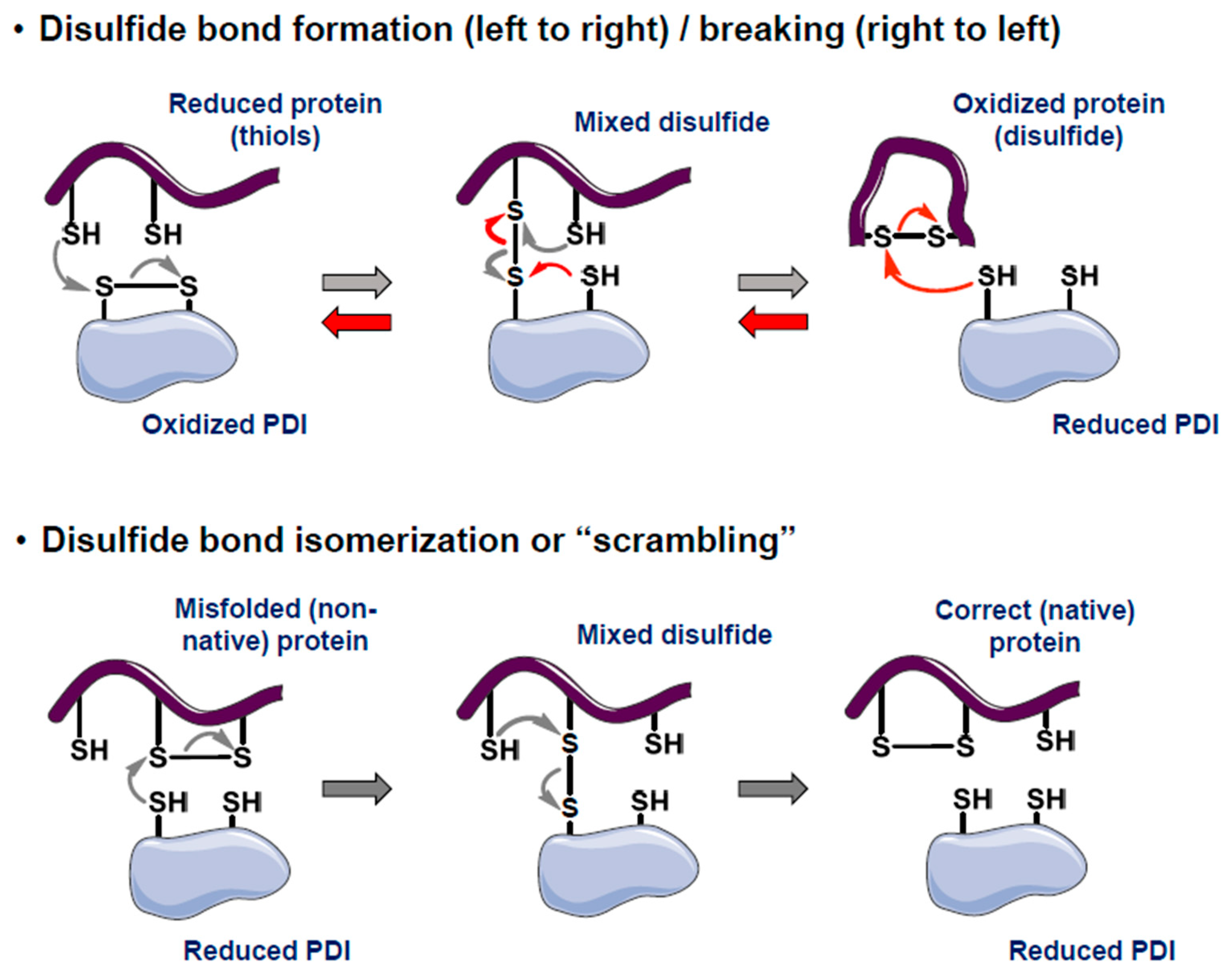

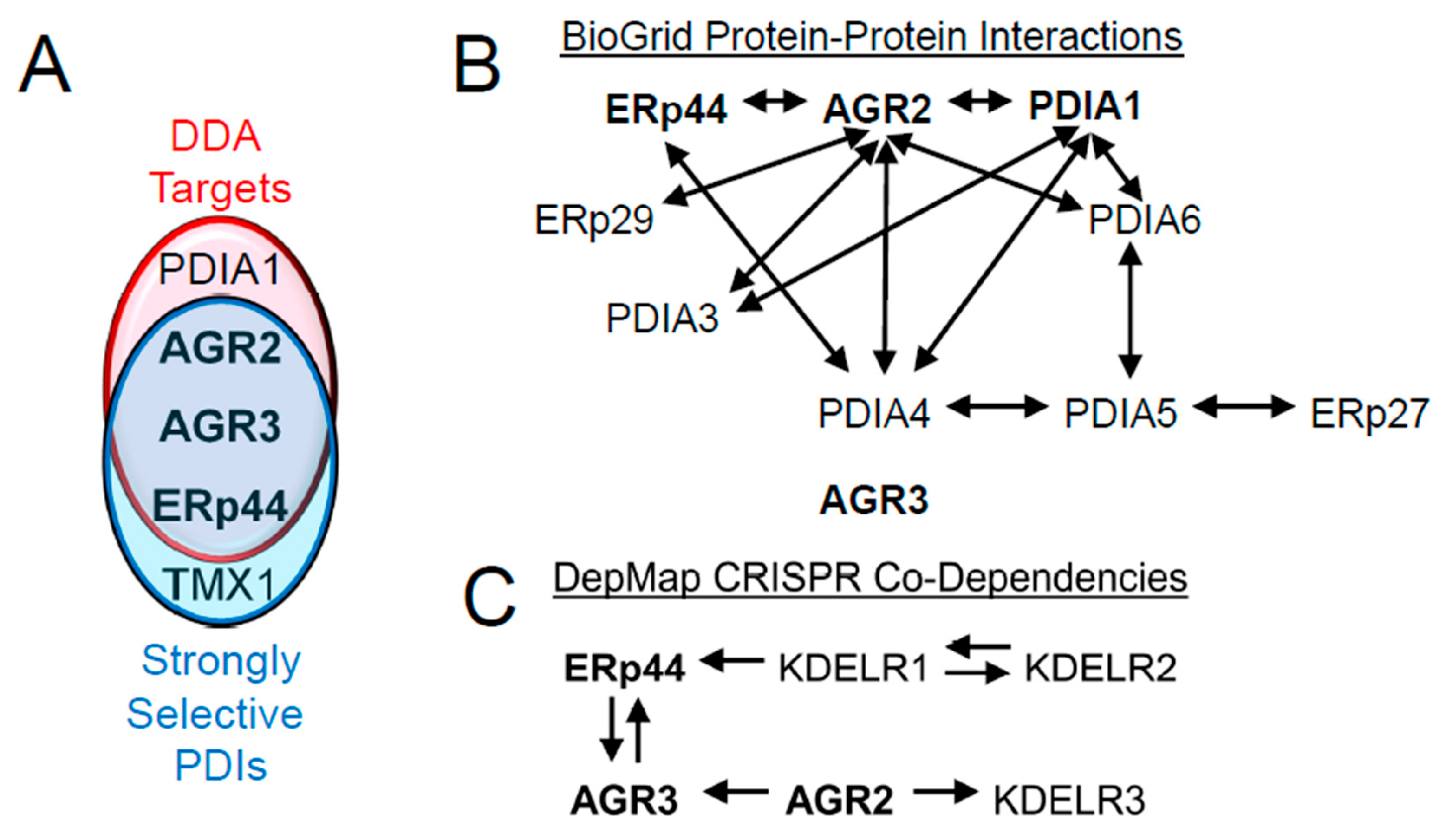

2. Protein Disulfide Isomerases as a Druggable Vulnerability in a Subset of Human Cancers

3. Roles of Strongly Selective Disulfide Isomerases in Protein Folding and Cellular Signaling

4. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Strongly Selective and Non-Canonical Disulfide Isomerases

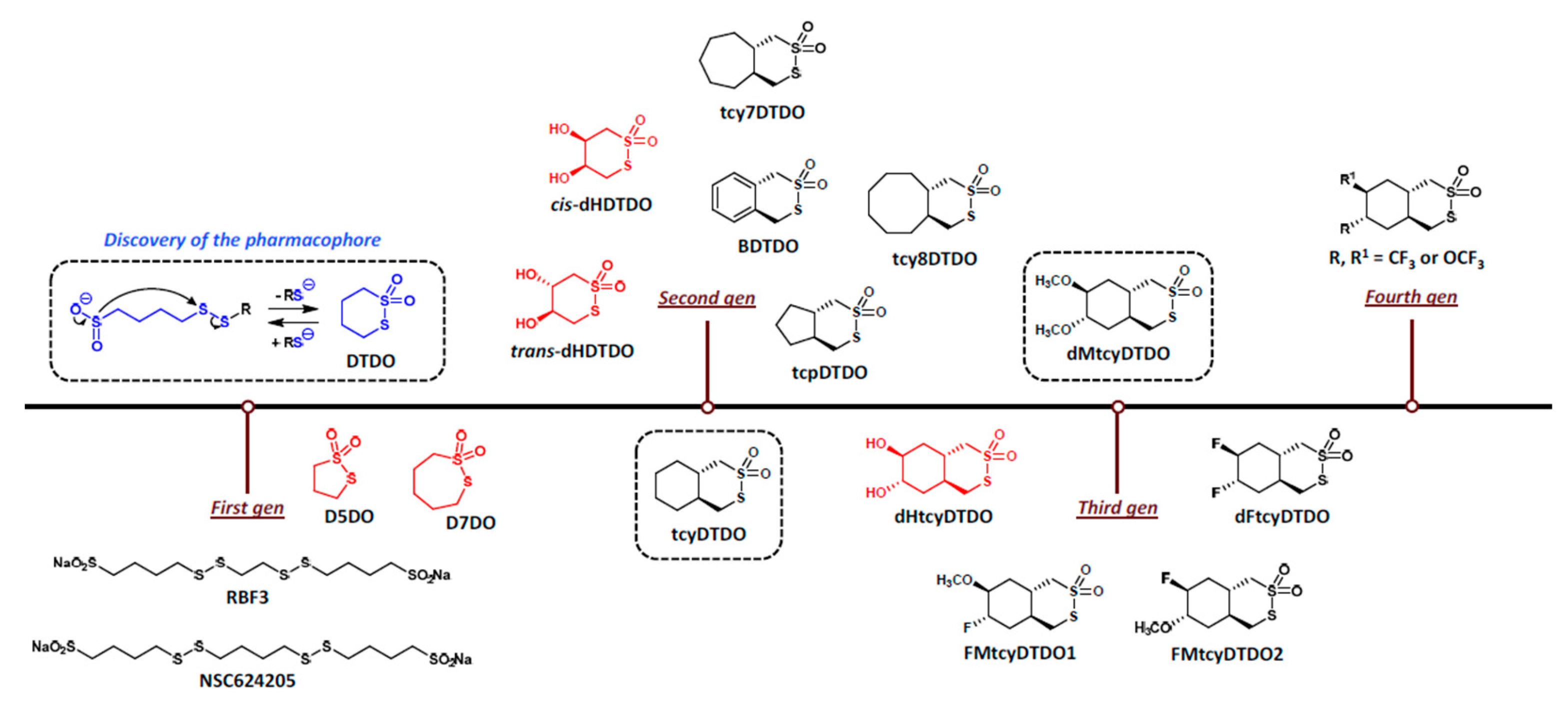

5. DDAs: Disulfide Isomerase Inhibitors with a Unique Selectivity Profile

6. Unanswered Questions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicting Interests

References

- Pourdehnad, M.; Truitt, M.L.; Siddiqi, I.N.; Ducker, G.S.; Shokat, K.M.; Ruggero, D. Myc and mTOR converge on a common node in protein synthesis control that confers synthetic lethality in Myc-driven cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 11988–11993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggero, D. The role of Myc-induced protein synthesis in cancer. Cancer Res 2009, 69, 8839–8843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, W.L.; Spaan, C.N.; Johannes de Boer, R.; Ramesh, P.; Martins Garcia, T.; Meijer, B.J.; et al. Driver mutations of the adenoma-carcinoma sequence govern the intestinal epithelial global translational capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 25560–25570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stams, W.A.; den Boer, M.L.; Holleman, A.; Appel, I.M.; Beverloo, H.B.; van Wering, E.R.; et al. Asparagine synthetase expression is linked with L-asparaginase resistance in TEL-AML1-negative but not TEL-AML1-positive pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2005, 105, 4223–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, R.J.; Woods, W.G.; Lampkin, B.C.; Nesbit, M.E.; Lee, J.W.; Buckley, J.D.; et al. Impact of high-dose cytarabine and asparaginase intensification on childhood acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Childrens Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol 1993, 11, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, A.K.; Ng, L.; Sing Li, H.; Cheng, C.W.; Lam, C.S.; Yau, T.C.; et al. Anti-tumor efficacy of a recombinant human arginase in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2012, 12, 1233–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Inanami, O.; Fujii, J.; Nakajima, O.; Ito, T.; et al. LAT1 inhibitor JPH203 sensitizes cancer cells to radiation by enhancing radiation-induced cellular senescence. Transl Oncol 2021, 14, 101212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier-Coles, G.; Broer, A.; McLeod, M.D.; George, A.J.; Hannan, R.D.; Broer, S. Identification and characterization of a novel SNAT2 (SLC38A2) inhibitor reveals synergy with glucose transport inhibition in cancer cells. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 963066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikubo, K.; Ohgaki, R.; Liu, X.; Okanishi, H.; Xu, M.; Endou, H.; et al. Combination effects of amino acid transporter LAT1 inhibitor nanvuranlat and cytotoxic anticancer drug gemcitabine on pancreatic and biliary tract cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int 2023, 23, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, S.; Nielsen, C.U. Exploring Amino Acid Transporters as Therapeutic Targets for Cancer: An Examination of Inhibitor Structures, Selectivity Issues, and Discovery Approaches. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rii, J.; Sakamoto, S.; Mizokami, A.; Xu, M.; Fujimoto, A.; Saito, S.; et al. L-type amino acid transporter 1 inhibitor JPH203 prevents the growth of cabazitaxel-resistant prostate cancer by inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinase activity. Cancer Sci 2024, 115, 937–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.E.; Dalton, L.; Malzer, E.; Marciniak, S.J. Unravelling the story of protein misfolding in diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes 2011, 2, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, G.M.; Greig, N.H.; Khan, T.A.; Hassan, I.; Tabrez, S.; Shakil, S.; et al. Protein misfolding and aggregation in Alzheimer's disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2014, 13, 1280–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A.; Morales-Scheihing, D.; Butler, P.C.; Soto, C. Type 2 diabetes as a protein misfolding disease. Trends Mol Med 2015, 21, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gonzalez, I.; Edwards Iii, G.; Salvadores, N.; Shahnawaz, M.; Diaz-Espinoza, R.; Soto, C. Molecular interaction between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer's disease through cross-seeding of protein misfolding. Mol Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, S. Targeting protein misfolding to protect pancreatic beta-cells in type 2 diabetes. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2018, 43, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C. Unfolding the role of protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003, 4, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agorogiannis, E.I.; Agorogiannis, G.I.; Papadimitriou, A.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.M. Protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2004, 30, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, L.K.; Uryu, K.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M. TDP-43 proteinopathies: neurodegenerative protein misfolding diseases without amyloidosis. Neurosignals 2008, 16, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Lipton, S.A. Cell death: protein misfolding and neurodegenerative diseases. Apoptosis 2009, 14, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, M.; Rzymski, T.; Mellor, H.R.; Pike, L.; Bottini, A.; Generali, D.; et al. The role of ATF4 stabilization and autophagy in resistance of breast cancer cells treated with Bortezomib. Cancer Res 2009, 69, 4415–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Sharma, N.; Golden, E.B.; Cho, H.; Agarwal, P.; Gaffney, K.J.; et al. Preferential killing of triple-negative breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo when pharmacological aggravators of endoplasmic reticulum stress are combined with autophagy inhibitors. Cancer Lett 2012, 325, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Liu, H.; Jiang, C.C.; Fang, L.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.D.; et al. Connecting endoplasmic reticulum stress to autophagy through IRE1/JNK/beclin-1 in breast cancer cells. Int J Mol Med 2014, 34, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Golemis, E.A. A new strategy to ERADicate HER2-positive breast tumors? Sci Signal 2015, 8, fs11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Joshi, R.; Komurov, K. HER2-mTOR signaling-driven breast cancer cells require ER-associated degradation to survive. Sci Signal 2015, 8, ra52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, V.; Zheng, W.; Adam-Artigues, A.; Staschke, K.A.; Huang, X.; Cheung, J.F.; et al. A PERK-Specific Inhibitor Blocks Metastatic Progression by Limiting Integrated Stress Response-Dependent Survival of Quiescent Cancer Cells. Clin Cancer Res 2023, 29, 5155–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urano, F.; Bertolotti, A.; Ron, D. IRE1 and efferent signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci 2000, 113 Pt 21, 3697–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urano, F.; Wang, X.; Bertolotti, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chung, P.; Harding, H.P.; et al. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science 2000, 287, 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haze, K.; Yoshida, H.; Yanagi, H.; Yura, T.; Mori, K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Molecular Biology of the Cell 1999, 10, 3787–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J.W.; Diehl, J.A. PERK mediates cell-cycle exit during the mammalian unfolded protein response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 12625–12630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.P.; Novoa, I.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zeng, H.Q.; Wek, R.; Schapira, M.; et al. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Molecular cell 2000, 6, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwawaki, T.; Hosoda, A.; Okuda, T.; Kamigori, Y.; Nomura-Furuwatari, C.; Kimata, Y.; et al. Translational control by the ER transmembrane kinase/ribonuclease IRE1 under ER stress. Nat Cell Biol 2001, 3, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, R.; Emi, M.; Tanabe, K.; Murakami, S. Role of the unfolded protein response in cell death. Apoptosis 2006, 11, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiss, D.C.; Gabriels, G.A. Implications of endoplasmic reticulum stress, the unfolded protein response and apoptosis for molecular cancer therapy. Part I: targeting p53, Mdm2, GADD153/CHOP, GRP78/BiP and heat shock proteins. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2009, 4, 799–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazari, Y.M.; Bashir, A.; Haq, E.U.; Fazili, K.M. Emerging tale of UPR and cancer: an essentiality for malignancy. Tumour Biol 2016, 37, 14381–14390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Law, M.E.; Castellano, R.K.; Law, B.K. The unfolded protein response as a target for anticancer therapeutics. Critical Reviews in Oncology / Hematology 2018, 127, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuRose, J.B.; Scheuner, D.; Kaufman, R.J.; Rothblum, L.I.; Niwa, M. Phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2alpha coordinates rRNA transcription and translation inhibition during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29, 4295–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Novoa, I.; Lu, P.D.; Calfon, M.; et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Molecular cell 2003, 11, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.C.; Scheraga, H.A. Catalysis of the oxidative folding of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A by protein disulfide isomerase. J Mol Biol 2000, 300, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheraga, H.A.; Konishi, Y.; Ooi, T. Multiple pathways for regenerating ribonuclease A. Adv Biophys 1984, 18, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, Y.; Ooi, T.; Scheraga, H.A. Regeneration of RNase A from the reduced protein: models of regeneration pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1982, 79, 5734–5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenman, D.E.; Lancet, D.; Pecht, I. Folding pathways of immunoglobulin domains. The folding kinetics of the Cgamma3 domain of human IgG1. Biochemistry 1979, 18, 3327–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, F.X.; Baldwin, R.L. Acid catalysis of the formation of the slow-folding species of RNase A: evidence that the reaction is proline isomerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1978, 75, 4764–4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhie, P. Kinetic studies on the unfolding and refolding of pepsinogen in urea. The nature of the rate-limiting step. J Biol Chem 1980, 255, 4048–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, K.E.; Ruan, B.; Alexander, P.A.; Wang, L.; Bryan, P.N. Mechanism of the kinetically-controlled folding reaction of subtilisin. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagradova, N. Enzymes catalyzing protein folding and their cellular functions. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2007, 8, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.P. Cyclophilin and protein disulfide isomerase genes are co-transcribed in a functionally related manner in Caenorhabditis elegans. DNA Cell Biol 1997, 16, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, M.; Kadokura, H.; Inaba, K. Structures and functions of protein disulfide isomerase family members involved in proteostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum. Free Radic Biol Med 2015, 83, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laboissiere, M.C.; Sturley, S.L.; Raines, R.T. The essential function of protein-disulfide isomerase is to unscramble non-native disulfide bonds. J Biol Chem 1995, 270, 28006–28009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulleid, N.J. Disulfide bond formation in the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.W.; Gilbert, H.F. Scanning and escape during protein-disulfide isomerase-assisted protein folding. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 8845–8848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furie, B.; Flaumenhaft, R. Thiol isomerases in thrombus formation. Circ Res 2014, 114, 1162–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.; Johannes, L.; Mallard, F.; Girod, A.; Grill, S.; Reinsch, S.; et al. Rab6 coordinates a novel Golgi to ER retrograde transport pathway in live cells. J Cell Biol 1999, 147, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murshid, A.; Presley, J.F. ER-to-Golgi transport and cytoskeletal interactions in animal cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 2004, 61, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anelli, T.; Alessio, M.; Mezghrani, A.; Simmen, T.; Talamo, F.; Bachi, A.; et al. ERp44, a novel endoplasmic reticulum folding assistant of the thioredoxin family. EMBO J 2002, 21, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsu, M.; Bertoli, G.; Fagioli, C.; Guerini-Rocco, E.; Nerini-Molteni, S.; Ruffato, E.; et al. Dynamic retention of Ero1alpha and Ero1beta in the endoplasmic reticulum by interactions with PDI and ERp44. Antioxid Redox Signal 2006, 8, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Parekh, V.V.; Mendez-Fernandez, Y.; Olivares-Villagomez, D.; Dragovic, S.; Hill, T.; et al. In vivo role of ER-associated peptidase activity in tailoring peptides for presentation by MHC class Ia and class Ib molecules. J Exp Med 2006, 203, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakihana, T.; Araki, K.; Vavassori, S.; Iemura, S.; Cortini, M.; Fagioli, C.; et al. Dynamic regulation of Ero1alpha and peroxiredoxin 4 localization in the secretory pathway. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 29586–29594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisatsune, C.; Ebisui, E.; Usui, M.; Ogawa, N.; Suzuki, A.; Mataga, N.; et al. ERp44 Exerts Redox-Dependent Control of Blood Pressure at the ER. Molecular cell 2015, 58, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, E.; Saveanu, L.; Aichele, P.; Staeheli, P.; Huai, J.; Gaedicke, S.; et al. The role of endoplasmic reticulum-associated aminopeptidase 1 in immunity to infection and in cross-presentation. J Immunol 2007, 178, 2241–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Batliwala, M.; Bouvier, M. ERAP1 enzyme-mediated trimming and structural analyses of MHC I-bound precursor peptides yield novel insights into antigen processing and presentation. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 18534–18544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastall, D.P.; Aldhamen, Y.A.; Seregin, S.S.; Godbehere, S.; Amalfitano, A. ERAP1 functions override the intrinsic selection of specific antigens as immunodominant peptides, thereby altering the potency of antigen-specific cytolytic and effector memory T-cell responses. Int Immunol 2014, 26, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- York, I.A.; Brehm, M.A.; Zendzian, S.; Towne, C.F.; Rock, K.L. Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 (ERAP1) trims MHC class I-presented peptides in vivo and plays an important role in immunodominance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 9202–9207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.C.; Momburg, F.; Bhutani, N.; Goldberg, A.L. The ER aminopeptidase, ERAP1, trims precursors to lengths of MHC class I peptides by a "molecular ruler" mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 17107–17112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, D.; Han, J. ERp44 depletion exacerbates ER stress and aggravates diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 504, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyirimigabo, E.; Jin, M.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhai, K.; Mao, Y.; et al. The role of ERp44 in glucose and lipid metabolism. Arch Biochem Biophys 2019, 671, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Chang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Mao, Y.; Zhai, K.; Zhou, Y.; et al. ERp44/CG9911 promotes fat storage in Drosophila adipocytes by regulating ER Ca(2+) homeostasis. Aging (Albany NY) 2021, 13, 15013–15031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anelli, T.; Ceppi, S.; Bergamelli, L.; Cortini, M.; Masciarelli, S.; Valetti, C.; et al. Sequential steps and checkpoints in the early exocytic compartment during secretory IgM biogenesis. EMBO J 2007, 26, 4177–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortini, M.; Sitia, R. ERp44 and ERGIC-53 synergize in coupling efficiency and fidelity of IgM polymerization and secretion. Traffic 2010, 11, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.V.; Schraw, T.D.; Kim, J.Y.; Khan, T.; Rajala, M.W.; Follenzi, A.; et al. Secretion of the adipocyte-specific secretory protein adiponectin critically depends on thiol-mediated protein retention. Mol Cell Biol 2007, 27, 3716–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, G. New insights into thiol-mediated regulation of adiponectin secretion. Nutr Rev 2008, 66, 642–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahameed, M.; Boukeileh, S.; Obiedat, A.; Darawshi, O.; Dipta, P.; Rimon, A.; et al. Pharmacological induction of selective endoplasmic reticulum retention as a strategy for cancer therapy. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Harayama, M.; Kanemura, S.; Sitia, R.; Inaba, K. Structural basis of pH-dependent client binding by ERp44, a key regulator of protein secretion at the ER-Golgi interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, E3224–E3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Amagai, Y.; Sannino, S.; Tempio, T.; Anelli, T.; Harayama, M.; et al. Zinc regulates ERp44-dependent protein quality control in the early secretory pathway. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anelli, T.; Alessio, M.; Bachi, A.; Bergamelli, L.; Bertoli, G.; Camerini, S.; et al. Thiol-mediated protein retention in the endoplasmic reticulum: the role of ERp44. EMBO J 2003, 22, 5015–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Vavassori, S.; Li, S.; Ke, H.; Anelli, T.; et al. Crystal structure of human ERp44 shows a dynamic functional modulation by its carboxy-terminal tail. EMBO Rep 2008, 9, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampe, L.; Xu, C.; Harris, P.W.R.; Chen, J.; Liu, M.; Middleditch, M.; et al. Synthetic peptides designed to modulate adiponectin assembly improve obesity-related metabolic disorders. Br J Pharmacol 2017, 174, 4478–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampe, L.; Harris, P.W.R.; Rushton, B.; Radjainia, M.; Brimble, M.A.; Mitra, A.K. Engineering a stable complex of ERp44 with a designed peptide ligand for analyzing the mode of interaction of ERp44 with its clients. Peptide Science 2021, 113, e24230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Shi, S.; You, B.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, M.; You, Y. ER resident protein 44 promotes malignant phenotype in nasopharyngeal carcinoma through the interaction with ATP citrate lyase. J Transl Med 2021, 19, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qiu, X.; Wang, F. Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O (PTPRO) knockdown enhances the proliferative, invasive and angiogenic activities of trophoblast cells by suppressing ER resident protein 44 (ERp44) expression in preeclampsia. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 9561–9574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solda, T.; Galli, C.; Guerra, C.; Hoefner, C.; Molinari, M. TMX5/TXNDC15, a natural trapping mutant of the PDI family is a client of the proteostatic factor ERp44. Life Sci Alliance 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Y.; Yang, Z.; Jin, M.; Zhai, K.; Wang, J.; Mao, Y.; et al. ERp44 is required for endocardial cushion development by regulating VEGFA secretion in myocardium. Cell Prolif 2022, 55, e13179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, M.; Wang, W.; et al. MiR-101 regulates apoptosis of trophoblast HTR-8/SVneo cells by targeting endoplasmic reticulum (ER) protein 44 during preeclampsia. J Hum Hypertens 2014, 28, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.H.; Jeon, Y.J.; Park, S.M.; Shin, J.C.; Lee, T.H.; Jung, S.; et al. Multifunctional effects of honokiol as an anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer drug in human oral squamous cancer cells and xenograft. Biomaterials 2015, 53, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.A.; Weigel, R.J. hAG-2, the human homologue of the Xenopus laevis cement gland gene XAG-2, is coexpressed with estrogen receptor in breast cancer cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998, 251, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberger, F.; Weidinger, G.; Grunz, H.; Richter, K. Anterior specification of embryonic ectoderm: the role of the Xenopus cement gland-specific gene XAG-2. Mech Dev 1998, 72, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, L.J.; Lu, Y.F.; Chen, Y.H.; Lin, C.C.; Chen, J.A.; Hwang, S.P. Characterization of the agr2 gene, a homologue of X. laevis anterior gradient 2, from the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Gene Expr Patterns 2007, 7, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, A.S.; Shandarin, I.N.; Ermakova, G.V.; Minin, A.A.; Tereshina, M.B.; Zaraisky, A.G. The secreted factor Ag1 missing in higher vertebrates regulates fins regeneration in Danio rerio. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 8123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, A.S.; Tereshina, M.B.; Ermakova, G.V.; Belousov, V.V.; Zaraisky, A.G. Agr genes, missing in amniotes, are involved in the body appendages regeneration in frog tadpoles. Sci Rep 2013, 3, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, M.M.; DeMayo, F.J.; Dekker, J.D.; et al. Foxp1/4 control epithelial cell fate during lung development and regeneration through regulation of anterior gradient 2. Development 2012, 139, 2500–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, M.; Liu, X.; Ji, X.; Li, S.; Jin, E. New insights into the unfolded protein response (UPR)-anterior gradient 2 (AGR2) pathway in the regulation of intestinal barrier function in weaned piglets. Anim Nutr 2023, 15, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shaibi, A.A.; Abdel-Motal, U.M.; Hubrack, S.Z.; Bullock, A.N.; Al-Marri, A.A.; Agrebi, N.; et al. Human AGR2 Deficiency Causes Mucus Barrier Dysfunction and Infantile Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 12, 1809–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.W.; Zhen, G.; Verhaeghe, C.; Nakagami, Y.; Nguyenvu, L.T.; Barczak, A.J.; et al. The protein disulfide isomerase AGR2 is essential for production of intestinal mucus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 6950–6955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoli-Avella, A.; Hotakainen, R.; Al Shehhi, M.; Urzi, A.; Pareira, C.; Marais, A.; et al. A disorder clinically resembling cystic fibrosis caused by biallelic variants in the AGR2 gene. J Med Genet 2022, 59, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, A.; Wodziak, D.; Lowe, A.W. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling requires a specific endoplasmic reticulum thioredoxin for the post-translational control of receptor presentation to the cell surface. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 8016–8027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, H.; Hu, L.; Negi, H.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Binding of anterior gradient 2 and estrogen receptor-alpha: Dual critical roles in enhancing fulvestrant resistance and IGF-1-induced tumorigenesis of breast cancer. Cancer Lett 2016, 377, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmans, M.L.; Zhao, F.; Andersen, B. The estrogen-regulated anterior gradient 2 (AGR2) protein in breast cancer: a potential drug target and biomarker. Breast Cancer Res 2013, 15, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Rudland, P.S.; Sibson, D.R.; Platt-Higgins, A.; Barraclough, R. Human homologue of cement gland protein, a novel metastasis inducer associated with breast carcinomas. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 3796–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hao, Y.; Lowe, A.W. The adenocarcinoma-associated antigen, AGR2, promotes tumor growth, cell migration, and cellular transformation. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Dong, A.; Lowe, A.W. AGR2 gene function requires a unique endoplasmic reticulum localization motif. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 4773–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, M.A.; Schlessinger, J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 2010, 141, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, M.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, N.; Li, L.; Jiang, J.; et al. Pro-metastatic activity of AGR2 interrupts angiogenesis target bevacizumab efficiency via direct interaction with VEGFA and activation of NF-kappaB pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2018, 1864, 1622–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Zhu, Q.; Yu, X.; Merugu, S.B.; Mangukiya, H.B.; Smith, N.; et al. Tumor-secreted anterior gradient-2 binds to VEGF and FGF2 and enhances their activities by promoting their homodimerization. Oncogene 2017, 36, 5098–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Z. AGR2 expression is regulated by HIF-1 and contributes to growth and angiogenesis of glioblastoma. Cell Biochem Biophys 2013, 67, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, T.; Deng, D.; Bover, L.; Wang, H.; Logsdon, C.D.; Ramachandran, V. New Blocking Antibodies against Novel AGR2-C4.4A Pathway Reduce Growth and Metastasis of Pancreatic Tumors and Increase Survival in Mice. Mol Cancer Ther 2015, 14, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.D.; Wu, K.; Liu, Y.J.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, H.; Ji, J.; et al. LY6/PLAUR domain containing 3 (LYPD3) maintains melanoma cell stemness and mediates an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Biol Direct 2023, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocce, K.J.; Jasper, J.S.; Desautels, T.K.; Everett, L.; Wardell, S.; Westerling, T.; et al. The Lineage Determining Factor GRHL2 Collaborates with FOXA1 to Establish a Targetable Pathway in Endocrine Therapy-Resistant Breast Cancer. Cell Rep 2019, 29, 889–903 e810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessart, D.; Domblides, C.; Avril, T.; Eriksson, L.A.; Begueret, H.; Pineau, R.; et al. Secretion of protein disulphide isomerase AGR2 confers tumorigenic properties. Elife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurel M, Obacz J, Avril T, Ding YP, Papadodima O, Treton X et al. Control of anterior GRadient 2 (AGR2) dimerization links endoplasmic reticulum proteostasis to inflammation. EMBO Mol Med, 2019; 11.

- Tonelli, C.; Yordanov, G.N.; Hao, Y.; Deschenes, A.; Hinds, J.; Belleau, P.; et al. A mucus production programme promotes classical pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gut 2024. [CrossRef]

- Neidhardt, L.; Cloots, E.; Friemel, N.; Weiss, C.A.M.; Harding, H.P.; McLaughlin, S.H.; et al. The IRE1beta-mediated unfolded protein response is repressed by the chaperone AGR2 in mucin producing cells. EMBO J 2023.

- Cloots, E.; Guilbert, P.; Provost, M.; Neidhardt, L.; Van de Velde, E.; Fayazpour, F.; et al. Activation of goblet-cell stress sensor IRE1β is controlled by the mucin chaperone AGR2. The EMBO Journal, 2023; 1-24-24. [Google Scholar]

- Bonser, L.R.; Schroeder, B.W.; Ostrin, L.A.; Baumlin, N.; Olson, J.L.; Salathe, M.; et al. The Endoplasmic Reticulum Resident Protein AGR3. Required for Regulation of Ciliary Beat Frequency in the Airway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2015, 53, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, J.; Zhang, H.; Hu, J.; Song, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; et al. AGR3 promotes the stemness of colorectal cancer via modulating Wnt/β-catenin signalling. Cellular Signalling 2020, 65, 109419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, P.J.; Boyd, R.; Tyson, K.L.; Fletcher, G.C.; Stamps, A.; Hudson, L.; et al. Comprehensive Proteomic Analysis of Breast Cancer Cell Membranes Reveals Unique Proteins with Potential Roles in Clinical Cancer*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 6482–6489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maresh, E.L.; Mah, V.; Alavi, M.; Horvath, S.; Bagryanova, L.; Liebeskind, E.S.; et al. Differential expression of anterior gradient gene AGR2 in prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armes, J.E.; Davies, C.M.; Wallace, S.; Taheri, T.; Perrin, L.C.; Autelitano, D.J. AGR2 expression in ovarian tumours: a potential biomarker for endometrioid and mucinous differentiation. Pathology 2013, 45, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.H.; Zhu, Q.; Gao, G.W.; Zhou, C.C.; Li, D.W. [Preparation, characterization and potential application of monoclonal antibody 18A4 against AGR2]. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi 2010, 26, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Negi, H.; Merugu, S.B.; Mangukiya, H.B.; Li, Z.; Zhou, B.; Sehar, Q.; et al. Anterior Gradient-2 monoclonal antibody inhibits lung cancer growth and metastasis by upregulating p53 pathway and without exerting any toxicological effects: A preclinical study. Cancer Letters 2019, 449, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Q.; Yu, X.; Rong, R.; Merugu, S.B.; et al. A humanized monoclonal antibody targeting secreted anterior gradient 2 effectively inhibits the xenograft tumor growth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016, 475, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Liu, G.-S.; Zeling Wang, A.; Zhou, B.; Yunus, F.-U.-N.; Raza, G.; et al. Construction and stable gene expression of AGR2xPD1 bi-specific antibody that enhances attachment between T-Cells and lung tumor cells, suppress tumor cell migration and promoting CD8 expression in cytotoxic T-cells. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2023, 31, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garri, C.; Howell, S.; Tiemann, K.; Tiffany, A.; Jalali-Yazdi, F.; Alba, M.M.; et al. Identification, characterization and application of a new peptide against anterior gradient homolog 2 (AGR2). Oncotarget 2018, 9, 27363–27379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, A.; Junaid, M.; Rafiq, H.; Htar, T.T.; et al. Prospect of Anterior Gradient 2 homodimer inhibition via repurposing FDA-approved drugs using structure-based virtual screening. Molecular Diversity 2022, 26, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Deng, Y.; Schuck, K.; Raulefs, S.; Maeritz, N.; et al. AGR2-Dependent Nuclear Import of RNA Polymerase II Constitutes a Specific Target of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma in the Context of Wild-Type p53. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1601–1614e1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohtar, M.A.; Hernychova, L.; O'Neill, J.R.; Lawrence, M.L.; Murray, E.; Vojtesek, B.; et al. The Sequence-specific Peptide-binding Activity of the Protein Sulfide Isomerase AGR2 Directs Its Stable Binding to the Oncogenic Receptor EpCAM. Mol Cell Proteomics 2018, 17, 737–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, K.; Ikezoe, T. miR-217 sensitizes chronic myelogenous leukemia cells to tyrosine kinase inhibitors by targeting pro-oncogenic anterior gradient 2. Experimental Hematology 2018, 68, 80–88e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhang, H. miR-199a-3p plays an anti-tumorigenic role in lung adenocarcinoma by suppressing anterior gradient 2. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 7859–7871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, W.; Dou, M.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; et al. 125I seeds inhibit proliferation and promote apoptosis in cholangiocarcinoma cells by regulating the AGR2-mediated p38 MAPK pathway. Cancer Letters 2022, 524, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, T.T.G.; Yun, J.; Ha, J.-S.; Kim, Y.-J.; Jang, W.-B.; Van Le, T.H.; et al. Inhibitory Effect of Etravirine, a Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor, via Anterior Gradient Protein 2 Homolog Degradation against Ovarian Cancer Metastasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, N.; Wang Y-q Wang C-f Jia M-q Niu H-m Lu, Q.-q.; et al. AGR2-induced cholesterol synthesis drives lovastatin resistance that is overcome by combination therapy with allicin. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2022, 43, 2905–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, T.A.; MacLaine, N.J.; Michie, C.O.; Bouchalova, P.; Murray, E.; Howie, J.; et al. Anterior Gradient-3, A novel biomarker for ovarian cancer that mediates cisplatin resistance in xenograft models. Journal of Immunological Methods 2012, 378, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obacz, J.; Sommerova, L.; Sicari, D.; Durech, M.; Avril, T.; Iuliano, F.; et al. Extracellular AGR3 regulates breast cancer cells migration via Src signaling. Oncol Lett 2019, 18, 4449–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, L.; Xie, J.; Guo, S.; Yu, H.; Chen, R.; Tao, K.; et al. AGR3 promotes estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cell proliferation in an estrogen-dependent manner. Oncol Lett 2020, 20, 1441–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Anterior Gradient 3 Promotes Breast Cancer Development and Chemotherapy Response. Cancer Res Treat 2020, 52, 218–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, M.E.; Davis, B.J.; Ghilardi, A.F.; Yaaghubi, E.; Dulloo, Z.M.; Wang, M.; et al. Repurposing Tranexamic Acid as an Anticancer Agent. Frontiers in Pharmacology (Original Research), 2022; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Law, M.E.; Davis, B.J.; Yaaghubi, E.; Ghilardi, A.F.; Ferreira, R.B.; et al. Disulfide bond-disrupting agents activate the tumor necrosis family-related apoptosis-inducing ligand/death receptor 5 pathway. Cell Death Discov 2019, 5, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Ferreira, R.B.; Law, M.E.; Davis, B.J.; Yaaghubi, E.; Ghilardi, A.F.; et al. A novel proteotoxic combination therapy for EGFR+ and HER2+ cancers. Oncogene 2019, 38, 4264–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besse, L.; Besse, A.; Mendez-Lopez, M.; Vasickova, K.; Sedlackova, M.; Vanhara, P.; et al. A metabolic switch in proteasome inhibitor-resistant multiple myeloma ensures higher mitochondrial metabolism, protein folding and sphingomyelin synthesis. Haematologica 2019, 104, e415–e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.E.; Dulloo, Z.M.; Eggleston, S.R.; Takacs, G.P.; Alexandrow, G.M.; Lee, Y.i.; et al. DR5 disulfide bonding functions as a sensor and effector of protein folding stress. Molecular Cancer Research 2024. [CrossRef]

- Law, M.E.; Yaaghubi, E.; Ghilardi, A.F.; Davis, B.J.; Ferreira, R.B.; Koh, J.; et al. Inhibitors of ERp44, PDIA1, and AGR2 induce disulfide-mediated oligomerization of Death Receptors 4 and 5 and cancer cell death. Cancer Lett 2022, 534, 215604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumantou, D.; Barnea, E.; Martin-Esteban, A.; Maben, Z.; Papakyriakou, A.; Mpakali, A.; et al. Editing the immunopeptidome of melanoma cells using a potent inhibitor of endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 (ERAP1). Cancer Immunol Immunother 2019, 68, 1245–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.B.; Law, M.E.; Jahn, S.C.; Davis, B.J.; Heldermon, C.D.; Reinhard, M.; et al. Novel agents that downregulate EGFR, HER2, and HER3 in parallel. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 10445–10459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, L.; Khim, Y.H. Organic disulfides and related substances. 33. Sodium 4-(2-acetamidoethyldithio)butanesulfinate and related compounds as antiradiation drugs. J Med Chem 1972, 15, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.K.; Field, L. Organic Disulfides and Related Substances.45. Synthesis and Properties of Some Disulfide Sulfinate Salts Containing No Nitrogen. J Chem Eng Data 1986, 31, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghilardi, A.F.; Yaaghubi, E.; Ferreira, R.B.; Law, M.E.; Yang, Y.; Davis, B.J.; et al. Anticancer Agents Derived from Cyclic Thiosulfonates: Structure-Reactivity and Structure-Activity Relationships. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202200165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, R.B.; Wang, M.; Law, M.E.; Davis, B.J.; Bartley, A.N.; Higgins, P.J.; et al. Disulfide bond disrupting agents activate the unfolded protein response in EGFR- and HER2-positive breast tumor cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 28971–28989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruice, T.C.; Pandit, U.K. Intramolecular Models Depicting the Kinetic Importance of "Fit" in Enzymatic Catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1960, 46, 402–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houk, J.; Whitesides, G.M. Characterization and Stability of Cyclic Disulfides and Cyclic Dimeric Bis(Disulfides). Tetrahedron 1989, 45, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, M.E.; Horning, B.D.; Khattri, R.; Roy, N.; Lu, J.P.; Whitby, L.R.; et al. Selective inhibitors of JAK1 targeting an isoform-restricted allosteric cysteine. Nat Chem Biol 2022, 18, 1388–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhong, Z.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, Z. Discovery of an Orally Available Janus Kinase 3 Selective Covalent Inhibitor. J Med Chem 2019, 62, 1054–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragan, A.M.; Ghaby, K.; Pond, M.P.; Roux, B. Computational Investigation of the Covalent Inhibition Mechanism of Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase by Ibrutinib. J Chem Inf Model 2024, 64, 3488–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoonor-Williams, E.; Abu-Saleh, A.A.A. Molecular Insights into the Impact of Mutations on the Binding Affinity of Targeted Covalent Inhibitors of BTK. J Phys Chem B 2024, 128, 2874–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Du, Y.; Huang, L.; Cui, J.; Niu, J.; Xu, Y.; et al. Discovery of novel potent covalent inhibitor-based EGFR degrader with excellent in vivo efficacy. Bioorg Chem 2022, 120, 105605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouffard, E.; Zaro, B.W.; Dix, M.M.; Cravatt, B.; Wong, C.H. Refinement of Covalent EGFR Inhibitor AZD9291 to Eliminate Off-target Activity. Tetrahedron Lett 2021, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Liu, C.F.; Zhang, W.; Rao, G.W. A New Dawn for Targeted Cancer Therapy: Small Molecule Covalent Binding Inhibitor Targeting K-Ras (G12C). Curr Med Chem 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selles, B.; Zannini, F.; Couturier, J.; Jacquot, J.P.; Rouhier, N. Atypical protein disulfide isomerases (PDI): Comparison of the molecular and catalytic properties of poplar PDI-A and PDI-M with PDI-L1A. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0174753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Gilbert, H.F.; Harper, J.W. Conserved residues flanking the thiol/disulfide centers of protein disulfide isomerase are not essential for catalysis of thiol/disulfide exchange. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 4205–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wunderlich, M.; Otto, A.; Maskos, K.; Mucke, M.; Seckler, R.; Glockshuber, R. Efficient catalysis of disulfide formation during protein folding with a single active-site cysteine. J Mol Biol 1995, 247, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.; Saidjalolov, S.; Moreau, D.; Thorn-Seshold, O.; Matile, S. Inhibition of Cell Motility by Cell-Penetrating Dynamic Covalent Cascade Exchangers: Integrins Participate in Thiol-Mediated Uptake. JACS Au 2023, 3, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shybeka, I.; Maynard, J.R.J.; Saidjalolov, S.; Moreau, D.; Sakai, N.; Matile, S. Dynamic Covalent Michael Acceptors to Penetrate Cells: Thiol-Mediated Uptake with Tetrel-Centered Exchange Cascades, Assisted by Halogen-Bonding Switches. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2022, 61, e202213433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Lim, B.; Cheng, Y.; Pham, A.T.; Maynard, J.; Moreau, D.; et al. Cyclic Thiosulfonates for Thiol-Mediated Uptake: Cascade Exchangers, Transporters, Inhibitors. JACS Au 2022, 2, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, Q.; Martinent, R.; Lim, B.; Pham, A.T.; Kato, T.; Lopez-Andarias, J.; et al. Thiol-Mediated Uptake. JACS Au 2021, 1, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, L.; Felber, J.G.; Scholzen, K.C.; Schmitt, C.; Wiegand, A.J.; Komissarov, L.; et al. Piperazine-Fused Cyclic Disulfides Unlock High-Performance Bioreductive Probes of Thioredoxins and Bifunctional Reagents for Thiol Redox Biology. J Am Chem Soc 2024. [CrossRef]

- Felber, J.G.; Kitowski, A.; Zeisel, L.; Maier, M.S.; Heise, C.; Thorn-Seshold, J.; et al. Cyclic Dichalcogenides Extend the Reach of Bioreductive Prodrugs to Harness Thiol/Disulfide Oxidoreductases: Applications to seco-Duocarmycins Targeting the Thioredoxin System. ACS Cent Sci 2023, 9, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, L.; Xie, J.; Guo, S.; Yu, H.; Chen, R.; Tao, K.; et al. AGR3 promotes estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cell proliferation in an estrogen-dependent manner. Oncol Lett 2020, 20, 1441–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obacz, J.; Brychtova, V.; Podhorec, J.; Fabian, P.; Dobes, P.; Vojtesek, B.; et al. Anterior gradient protein 3 is associated with less aggressive tumors and better outcome of breast cancer patients. Onco Targets Ther 2015, 8, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garczyk, S.; von Stillfried, S.; Antonopoulos, W.; Hartmann, A.; Schrauder, M.G.; Fasching, P.A.; et al. AGR3 in breast cancer: prognostic impact and suitable serum-based biomarker for early cancer detection. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0122106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kang, H.; Lyu, L.; Xiong, W.; Hu, Y. A target map of clinical combination therapies in oncology: an analysis of clinicaltrials.gov. Discov Oncol 2023, 14, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PDIA# | Alternate Names | Thioredoxin Repeat(s) | Enzymatic Motif | ER Retention | Strongly Selective in Broad DepMap (CRISPR; 12/24/24) |

Confirmed as DDA Targets | ||

| 1 | P4HB | CGHC, CGHC | + | -KDEL | - | + | ||

| 2 | PDA2, PDIp | CGHC, CTHC | + | -KEEL | - | - | ||

| 3 | ERp57 | CGHC, CGHC | + | -QEDL | - | - | ||

| 4 | ERp72 | CGHC, CGHC, CGHC | + | -KEEL | - | - | ||

| 5 | PDIR | CSMC, CGHC, CPHC | + | -KEEL | - | - | ||

| 6 | ERp5 | CGHC, CGHC | + | -KDEL | - | - | ||

| 7 | PDILT | SKQS, SKKC | - | -KEEL | - | - | ||

| 8 | ERp27 | - | - | -KTEL | - | - | ||

| 9 | ERp29 | - | - | -KEEL | - | - | ||

| 10 | ERp44, TXNDC4 | CRFS | + | -RDEL | + | + | ||

| 11 | TMX1 | CPAC | + | Transmembrane | + | - | ||

| 12 | TMX2 | SNDC | - | Transmembrane | - | - | ||

| 13 | TMX3 | CGHC | + | Transmembrane | - | - | ||

| 14 | TMX4 | CPSC | + | Transmembrane | - | - | ||

| 15 | TXNDC5, ERp46 | CGHC, CGHC, CGHC | + | -KDEL | - | - | ||

| 16 | TXNDC12, AGR1 | CGAC | + | -KTEL | - | - | ||

| 17 | AGR2 | CPHS | + | -KTEL | + | + | ||

| 18 | AGR3 | CQYS | + | -QSEL | + | + | ||

| 19 | DnaJ10, DnaJ | CSHC, CPPC, CHPC, CGPC | + | -KDEL | - | - | ||

| PDIB1 | Calsequestrin 1 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| PDIB2 | Calsequestrin 2 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| TMX5, TXNDC15 | CRFS | + | Transmembrane | - | - | |||

| AGR2 Selectively Dependent Cancer Line |

AGR2 Essentiality Rank (out of 17,347 genes) |

Tumor Type | Notes on top 10 essential genes: Gene essentiality rank is in parentheses. Fractions denote the number of top-10 most essential genes involved in Wnt signaling. |

|---|---|---|---|

| C80 | 1 | Colorectal | CDX2 (2) |

| COLO205 | 4 | FOXP4 (2), FOXA2 (10) | |

| LS513 | 3 | CDX2 (1), CDX1 (6) | |

| SNUC4 | 5 | 2/10 Wnt signaling | |

| MAPACHS77 | 2 | Pancreatic | 7/10 Wnt signaling |

| HSC39 | 7 | Esophagogastric | |

| 2313287 | 9 | Gastric | 3/10 Wnt signaling |

| Rank | Gene |

|---|---|

| 1 | SOX9 |

| 2 | TTC7A |

| 3 | RAB10 |

| 4 | CTNNB1 (b-catenin) |

| 5 | AGR3 |

| Rank | Gene | Importance | Corr. Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ERN2 (IRE1b) | 23.1% | Expression |

| 2 | SH3BGRL2 | 2.1% | Expression |

| 3 | LRRC19 | 2.1% | Expression |

| 4 | RAB31 | 1.2% | Expression |

| 5 | NOX1 | 1.1% | Expression |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).