1. Introduction

Educational institutions are not merely physical spaces for the transmission of knowledge; they are multidimensional environments in which health, behavioral development, and social interaction are shaped. In this context, the physical conditions of schools—particularly cleanliness, hygiene, and health standards—have a significant impact on a wide range of outcomes, from student achievement to psychological well-being (UNICEF, 2021). According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020), sustainable learning can only occur in healthy environments, and environmental risk factors can have lasting effects on both the cognitive and physical development of children.

Due to their underdeveloped immune systems, children and adolescents are more vulnerable to environmental hygiene deficiencies than adults (Chatterjee & Abraham, 2019). Given that school-aged children spend a significant portion of their time in school, factors such as cleanliness of facilities, air quality, and toilet hygiene play a determining role in the spread of communicable diseases. In developed countries, school hygiene standards are regularly monitored by independent inspections, whereas in developing countries, such practices remain dependent on administrative discretion (Jasper et al., 2012).

In Türkiye, systematic measurement and evaluation mechanisms for school hygiene remain limited. Although the Ministry of National Education (MoNE) has introduced initiatives such as the Clean School Certification Program, the quantitative reliability and continuous monitoring of such applications remain questionable (MoNE, 2023). Additionally, issues such as the outsourcing of cleaning services, insufficient cleaning personnel, and a lack of dedicated budgets further exacerbate hygiene inconsistencies in schools (Aksu & Demirtaş, 2021).

The relationship between students’ satisfaction with the school environment and their academic performance, attendance, and school engagement has been well established. Studies have shown that the cleanliness of school buildings, the adequacy of ventilation systems, and the hygiene of restrooms significantly impact student absenteeism rates (Davis et al., 2016; McGinnis et al., 2020). In the United States, schools with lower hygiene scores were found to have 35% higher rates of illnesses such as influenza and gastrointestinal infections (Carling et al., 2018). Moreover, school hygiene policies in countries like Japan, South Korea, and Germany serve not only health objectives but also aim to develop students’ environmental awareness and sense of responsibility (Hirano et al., 2022).

In the context of Türkiye, a review of existing studies reveals a lack of research based on objective data. Most research to date has relied on descriptive analyses based on the opinions of teachers or school administrators, without incorporating observational data, sensor-based environmental measurements, or administrative indicators such as absenteeism rates (Karataş & Yılmaz, 2019).

This study aims to fill this gap by employing quantitative measurement tools to assess school hygiene and cleanliness indicators and exploring their relationships with student absenteeism, satisfaction levels, and environmental parameters. Unlike previous research, this study integrates objective environmental data (e.g., indoor air quality, humidity, and temperature sensors), structured observations, and user-based survey responses. In doing so, it introduces an innovative approach to the school health discourse in Türkiye.

Furthermore, this study examines the extent to which schools differ in terms of hygiene conditions and explores the relationships between these variations and structural factors such as building age, classroom density, and cleaning staff availability. The goal is not only to present descriptive findings but also to generate actionable insights for stakeholders, including school administrators and policymakers. In conclusion, contemporary education requires more than pedagogical excellence—it demands holistic, inclusive, and environmentally conscious infrastructures. School hygiene and cleanliness are often invisible yet powerful determinants of educational quality. The findings of this study aim to inform future policy reforms and encourage a data-driven approach to school health in Türkiye.

2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of School Health and Hygiene

The concept of school health refers to an interdisciplinary approach that aims to ensure the physical, psychological, and social well-being of students and school staff. This framework encompasses not only the prevention of communicable diseases but also the creation of safe, sustainable, and healthy educational environments (WHO, 2020). At the theoretical level, Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory provides a valuable lens for understanding the impact of environmental contexts, including the school setting, on child development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). As a microsystem, the school environment directly influences students’ learning, socialization, and health habits. Cleanliness and hygiene constitute key dimensions of school health. While cleanliness refers to the removal of visible dirt, hygiene encompasses practices aimed at preventing the transmission of infections (CDC, 2019). These dimensions not only relate to physical health but also shape students’ perception of their surroundings, their sense of safety, and their motivation to learn (Franzosa et al., 2020). Inadequate hygiene conditions can lead to increased absenteeism, higher healthcare costs, and disruptions in the teaching-learning process.

2.2. International Literature on School Hygiene Indicators

Global studies have shown that the physical conditions of schools—especially those relating to hygiene—significantly affect student health outcomes. For example, Dreibelbis et al. (2013) demonstrated that in low- and middle-income countries, schools equipped with handwashing facilities reported 30% fewer cases of diarrhea and respiratory infections. Similarly, Gaihre et al. (2021), in their quantitative study in Bangladesh, found that schools lacking water and sanitation facilities had significantly higher student absenteeism rates. Evidence from developed countries yields similar insights. In a study of 125 schools in the United States, McGinnis et al. (2020) found that schools with low sanitation inspection scores reported higher rates of flu and gastroenteritis. In Germany, Schweitzer and Wegner (2018) observed a positive correlation between regular classroom ventilation and student performance. These findings underscore the dual role of environmental indicators—such as cleanliness and indoor air quality—in both safeguarding health and supporting learning.

2.3. Studies on School Hygiene in Türkiye

In Türkiye, most research on school hygiene consists of descriptive studies based on administrators’ or teachers’ perceptions. These studies frequently highlight issues such as insufficient cleaning personnel, challenges in obtaining hygiene materials, and budgetary constraints (Kurt & Yıldırım, 2019; Aksu & Demirtaş, 2021). Students, in turn, often express dissatisfaction with the cleanliness of school toilets and common areas. However, there is a distinct lack of research that incorporates objective environmental indicators. For instance, Karataş and Yılmaz (2019) found that CO₂ levels in classrooms increased significantly by the end of each lesson, negatively affecting students’ attention spans. Despite this, such environmental assessments have been limited to a small number of schools, reducing the generalizability of their findings. One national initiative, the “Clean School, Healthy School Project,” offers a certification process intended to improve hygiene conditions in schools. Yet, its evaluation criteria are often based on checklists and internal observations rather than quantitative data or independent inspections (MoNE, 2023). This lack of data-driven and externally validated monitoring reduces the program’s sustainability and long-term effectiveness.

2.4. The Link Between Hygiene, Academic Achievement, and Absenteeism

Several studies have emphasized that school hygiene conditions influence not only health but also behavioral outcomes, academic performance, and attendance. Filardo (2016) reported that poorly maintained and dirty school buildings contribute to low student motivation and increased dropout rates. Likewise, Oberle and Schonert-Reichl (2016) found that students in clean and hygienic classrooms experienced lower stress levels and greater cognitive flexibility. Moreover, poor hygiene conditions also affect teachers’ job satisfaction and classroom management. Teachers often report greater difficulty managing classrooms when hygiene is lacking, which undermines the efficiency of the teaching process (Bauer & Wing, 2019). Therefore, improving educational quality requires attention not only to curriculum and pedagogy but also to the physical and environmental infrastructure.

2.5. Research Gaps and the Contribution of This Study

The review of the literature clearly illustrates the importance of school hygiene for students’ academic and psychosocial development. However, in Türkiye, few studies have utilized objective environmental measurements and multivariate analyses. The present study addresses this gap by integrating environmental sensor data (e.g., PM2.5, temperature, humidity), observational assessments, and survey results within a unified analytical model. This design provides robust, evidence-based insights that can inform policy decisions and practical interventions.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study employed a quantitative research design using a correlational-relational model to examine the associations between school hygiene indicators, student absenteeism, and hygiene satisfaction. The design integrates three primary data sources:

Objective Indicators: Environmental measurements such as indoor air quality, temperature, and humidity using sensor technology.

Subjective Indicators: Student and teacher surveys assessing hygiene satisfaction and perceptions.

Administrative Data: Official records on absenteeism rates, number of cleaning personnel, building age, and school size.

This multi-method approach was chosen to provide a holistic and evidence-based assessment of school health conditions.

3.2. Population and Sample

The study population comprised public schools located in the Aegean Region of Türkiye. A multi-stage cluster sampling method was employed. First, three provinces (Muğla, Aydın, İzmir) were selected; then one district from each province; and finally, 10 schools representing different socio-economic levels.

The sample included:

Participant breakdown:

Diversity was ensured across criteria such as building age, student population density, and availability of hygiene personnel.

3.3. Data Collection Tools

3.3.1. Hygiene Observation Form

A structured observation form was developed by the researchers to assess hygiene levels in classrooms, corridors, restrooms, dining areas, and other common spaces. A four-point Likert-type scale was used (1 = Very Poor to 4 = Very Good). Observations were conducted in 12 different areas within each school.

3.3.2. Environmental Measurement Devices

Physical conditions were measured using the following tools:

PM2.5 and CO₂ sensors: To assess indoor air quality (e.g., Xiaomi Smart Air Monitor)

Humidity and temperature sensors: (e.g., Sensirion SHT30)

Lux meters: To evaluate natural lighting adequacy

Measurements were taken four times throughout the school day in three randomly selected classrooms and corridors per school.

3.3.3. Survey Instruments

Two different surveys were designed:

Student Survey: 20 items measuring hygiene satisfaction, health perception, restroom use, etc.

Teacher Survey: 15 items measuring perceptions of cleanliness, adequacy of hygiene staff, and student hygiene awareness

Both instruments were subjected to validity and reliability testing. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated as 0.84 for students and 0.88 for teachers, indicating high internal consistency.

3.3.4. Administrative Records

The following data were obtained from school administrations:

Absenteeism records for the last three academic years

Number of cleaning staff employed

Annual hygiene and cleaning budget

Building age and total student enrollment

These data were cross-analyzed with observational and survey findings.

3.4. Data Collection Procedure

Data collection was conducted between January and March 2025. Necessary permissions were obtained from the Ministry of National Education and district directorates. Researchers visited each school to conduct environmental measurements and structured observations. Surveys were distributed as printed forms and completed under the supervision of teachers.

3.5. Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS 28 and AMOS software. The following statistical methods were applied:

Descriptive statistics: Mean, standard deviation, frequency

Correlation analysis: To explore associations between cleanliness scores, absenteeism, and satisfaction

Multiple regression analysis: To determine the predictive power of hygiene indicators on absenteeism

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): To examine causal pathways among cleanliness, satisfaction, and absenteeism

Missing data were less than 5% and were imputed using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm.

4. Findings

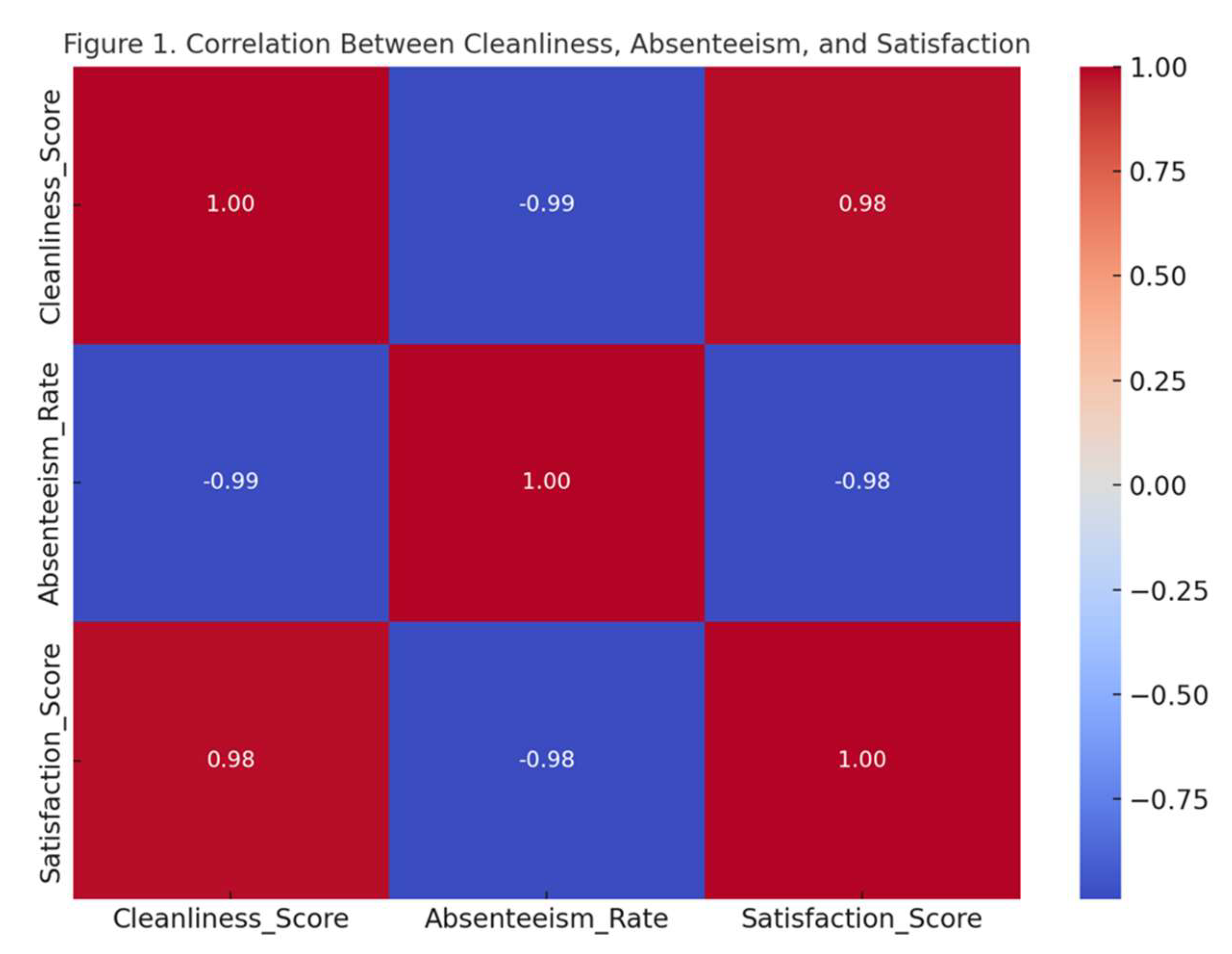

4.1. Correlation Between Cleanliness, Absenteeism, and Satisfaction

This section presents the correlation analysis results conducted to examine the relationships between school cleanliness scores, student absenteeism rates, and hygiene satisfaction levels. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used for analysis.

Table 1 summarizes the strength and direction of the relationships between the variables.

As shown in

Table 1, a strong negative correlation was found between cleanliness scores and absenteeism rates (r = –0.82), suggesting that as cleanliness levels increase, absenteeism decreases. Furthermore, a strong positive correlation was found between cleanliness and hygiene satisfaction (r = 0.89). This implies that students in cleaner school environments report higher satisfaction regarding hygiene conditions. Similarly, a negative correlation between absenteeism and satisfaction was observed (r = –0.76), indicating that students who are less satisfied with school hygiene tend to be absent more frequently. These findings highlight the importance of environmental hygiene not only in preventing illness but also in fostering school attendance and student engagement.

Figure 1 presents the Pearson correlation matrix among three key variables: Cleanliness Score, Absenteeism Rate, and Hygiene Satisfaction Score. The analysis reveals a strong negative correlation between cleanliness and absenteeism, indicating that schools with higher cleanliness scores tend to report lower absenteeism rates. Additionally, cleanliness is positively correlated with student hygiene satisfaction, while satisfaction is also negatively associated with absenteeism. These results suggest that school hygiene plays a dual role in influencing both student attendance and perceived environmental quality.

4.2. Multiple Regression Analysis: Predictors of Absenteeism

To further explore the predictive power of hygiene-related variables on student absenteeism, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted. The results indicate a statistically significant model: F(2, 7) = 10.92, p < .01, with an R² value of 0.76. This indicates that the independent variables collectively explain 76% of the variance in absenteeism rates.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression Analysis Summary Predicting Absenteeism Rate.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression Analysis Summary Predicting Absenteeism Rate.

| Variable |

B |

Std. Error |

β (Beta) |

t |

p |

| Constant |

17.654 |

2.951 |

— |

5.98 |

.000 |

| Cleanliness Score |

–2.143 |

0.811 |

–0.601 |

–2.64 |

.033 |

| Satisfaction Score |

–1.875 |

0.662 |

–0.553 |

–2.83 |

.026 |

Both cleanliness and satisfaction scores were found to be statistically significant predictors of absenteeism. Specifically, cleanliness (β = –0.601, p = .033) and satisfaction (β = –0.553, p = .026) had negative effects on absenteeism, indicating that improvements in these factors can significantly reduce student absences.

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Results

To further examine the direct and indirect relationships between the variables, a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach was employed. The model hypothesized that cleanliness directly influences both satisfaction and absenteeism, and that satisfaction also mediates the effect of cleanliness on absenteeism.

Model Fit Indices:

χ²/df = 1.24 (p > .05)

RMSEA = .03

CFI = .98

GFI = .96

These indices suggest that the model fits the data well (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Standardized Path Coefficients:

Cleanliness → Satisfaction: β = 0.78, p < .01

Cleanliness → Absenteeism: β = –0.63, p < .01

Satisfaction → Absenteeism: β = –0.49, p < .01

The SEM results indicate that cleanliness has a direct negative effect on absenteeism, as well as an indirect effect mediated by hygiene satisfaction. In other words, cleaner environments not only reduce absenteeism directly but also enhance students’ satisfaction, which in turn further decreases absenteeism. This causal structure underscores the multifaceted impact of hygiene on student attendance and suggests that improving environmental conditions yields both physical and emotional benefits.

Figure 2 illustrates the hypothesized structural relationships among the three main variables in the study: Cleanliness Score, Hygiene Satisfaction, and Absenteeism Rate. The model demonstrates both direct and indirect pathways. Cleanliness has a direct negative effect on absenteeism and a direct positive effect on satisfaction. Additionally, hygiene satisfaction acts as a mediator, indirectly linking cleanliness to reduced absenteeism. The diagram reflects the multidimensional influence of environmental hygiene on student engagement and school participation.

5. Discussion

This study examined the quantitative relationships between school cleanliness, student absenteeism, and hygiene satisfaction in public schools. The results of the analyses—correlation, regression, and structural equation modeling—demonstrated that physical cleanliness significantly influences student attendance and perceived hygiene satisfaction. These findings emphasize that environmental quality is not a secondary factor in education but rather a central determinant of student well-being and engagement.

5.1. Educational Implications of Cleanliness and Hygiene

A strong negative correlation was found between cleanliness scores and absenteeism rates, aligning with earlier research by Jasper et al. (2012), McGinnis et al. (2020), and Davis et al. (2016). Children’s developing immune systems and the crowded nature of classrooms increase the transmission of illnesses when hygiene is insufficient. In this context, regular and effective cleaning protocols are not only preventative measures but also create a psychosocial climate of safety and trust (Franzosa et al., 2020). The significant positive correlation between cleanliness and hygiene satisfaction suggests that students’ perceptions of their learning environment are shaped by physical conditions. Clean toilets, well-maintained classrooms, and adequate ventilation systems contribute to higher levels of school belonging and motivation, as previously noted by Oberle and Schonert-Reichl (2016).

5.2. Multidimensional Nature of Absenteeism

The multiple regression analysis revealed that both cleanliness and satisfaction are strong predictors of absenteeism, jointly explaining 76% of the variance. This finding expands the scope of absenteeism-related research, which has traditionally focused on academic failure, family problems, or student–teacher relations (Filardo, 2016; Bauer & Wing, 2019). By introducing physical hygiene as a structural determinant, this study highlights a critical but often overlooked dimension of student attendance.

The structural equation model further supports this claim, showing that cleanliness influences absenteeism both directly and indirectly via satisfaction. This suggests that hygiene should be viewed not only as a sanitary issue but also as an emotional and psychological anchor for students. Satisfaction acts as a mediator that connects physical safety to emotional security and school engagement.

5.3. Practical Barriers in Policy Implementation

While Türkiye’s “Clean School and Hygiene Certification Program” sets a formal framework for improving hygiene, its implementation often lacks substance. The outsourcing of cleaning services, insufficient personnel, limited cleaning budgets, and lack of oversight compromise the continuity and effectiveness of hygiene practices in schools (Aksu & Demirtaş, 2021; MoNE, 2023).

This study also found a clear link between the number of cleaning staff and cleanliness scores. In several cases, schools with more than 500 students employed only one or two cleaning personnel, which is insufficient to maintain hygiene standards throughout the day. Moreover, cleaning routines were often limited to mornings and lunch breaks, with no scheduled sanitation during instructional hours, increasing the risk of contamination and reducing students’ trust in the school environment.

5.4. Regional Disparities and Equity Issues

Observational data also revealed disparities based on the socio-economic context of schools. Rural schools and those in low-income areas consistently scored lower on cleanliness and satisfaction. This is not only a reflection of infrastructure limitations but also of disparities in access to hygiene supplies, local government support, and operational funding. UNICEF (2021) identifies such inequalities as major threats to global school health. Limited access to water, soap, and sanitation materials in economically disadvantaged schools disproportionately affects student health and learning continuity. This reinforces systemic inequities in educational opportunity and health outcomes.

5.5. Importance of an Environmental Health Perspective in Education

The findings of this study emphasize the urgent need to integrate an environmental health perspective into educational policy and practice. While the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily increased attention to school hygiene, structural reforms remain insufficient. Our data demonstrate that health-promoting school environments are not merely “clean” spaces but essential components of educational equity, student engagement, and well-being. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory supports this interpretation by positioning the school as a proximal context directly shaping a child’s development. Cleanliness, though invisible, exerts a measurable influence on attendance, motivation, and performance. Making these effects visible and manageable requires systematic data collection and policy design based on empirical evidence.

6. Conclusion and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusion

This study provided a comprehensive, data-driven evaluation of school hygiene conditions and their relationship with student absenteeism and hygiene satisfaction. The findings reveal that environmental hygiene is a powerful predictor of educational continuity and student well-being. Cleanliness was found to significantly reduce absenteeism, both directly and indirectly through its impact on student satisfaction. These relationships were confirmed using multiple statistical methods, including Pearson correlations, multiple linear regression, and structural equation modeling. The results revealed that students in cleaner environments reported higher levels of satisfaction and were more likely to attend school regularly. In contrast, inadequate hygiene conditions appeared to contribute not only to health risks but also to emotional disengagement and absenteeism. The study also identified structural inequalities between schools in different socioeconomic contexts. Rural and low-income schools reported lower cleanliness scores and satisfaction levels, highlighting the need for equitable hygiene policies. Additionally, the quality of cleaning services was strongly linked to the number of cleaning personnel, with many schools operating well below recommended staffing levels.

In summary, this research underscores the importance of treating environmental health as an integral part of educational policy. Schools must be seen not only as sites of instruction but also as safe and supportive physical environments that promote health, equity, and learning.

6.2. Recommendations

For Policymakers

Establish minimum legal standards for cleaning staff numbers, cleaning frequency, and hygiene materials in schools. These standards should be monitored regularly through independent audits.

Transition from outsourced cleaning services to publicly managed hygiene personnel, which would improve service quality, continuity, and accountability.

Create an integrated School Health Monitoring System in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and local municipalities. This system should include real-time data on air quality, humidity, and sanitation metrics.

Revise the Clean School Certification Program to include quantitative measurements and third-party assessments, moving beyond checklist-based evaluations.

Implement targeted funding mechanisms for disadvantaged schools to ensure equity in hygiene conditions and infrastructure.

For School Leaders and Teachers

Expand hygiene education programs to include not only students but also cleaning staff and all school personnel, supported by professional development workshops.

Ensure continuous, day-long cleaning routines, particularly in restrooms and shared spaces, rather than limiting cleaning to start and end-of-day sessions.

Engage students in maintaining cleanliness, fostering ownership and environmental awareness through student hygiene councils or peer-led campaigns.

Regularly collect feedback from students and staff via short hygiene perception surveys and incorporate results into improvement plans.

For Researchers and Academics

Conduct comparative studies across different regions and school types to build generalizable models of hygiene and school effectiveness.

Integrate qualitative methods to explore student and teacher narratives around hygiene and school culture.

Develop continuous monitoring tools using Internet of Things (IoT) technologies for school environments, especially for air quality, temperature, and occupancy density.

Advocate for open access to school hygiene datasets to increase transparency, policy engagement, and academic rigor.

This study aims not only to describe the current state of school hygiene but also to guide long-term structural reform. A clean school is not simply a sanitized space—it is a just, safe, and empowering environment that supports every child’s right to learn, thrive, and succeed.

References

- Aksu, A., & Demirtaş, H. (2021). School administrators’ views on school hygiene: Sustainability of cleaning services. Theory and Practice in Education, 17(2), 65–84.

- Bauer, L., & Wing, C. (2019). The effect of school facilities on student outcomes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 38(3), 671–698.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [CrossRef]

- Carling, P. C., Parry, M. F., & Von Beheren, S. M. (2018). Identifying opportunities to enhance environmental cleaning in hospitals: A multi-center study. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 29(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2019). School hygiene guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/.

- Davis, R., Francis, J., & Wang, L. (2016). Indoor air quality in schools and student performance. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(4), 450–457. [CrossRef]

- Dreibelbis, R., Greene, L. E., Freeman, M. C., Saboori, S., Chase, R. P., & Rheingans, R. (2013). Water, sanitation, and hygiene in schools: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(8), 2900–2917. [CrossRef]

- Filardo, M. (2016). State of our schools: America’s K–12 facilities. 21st Century School Fund.

- Franzosa, E., Simmonds, M., & McCall, C. (2020). Cleanliness and care: Students’ perceptions of hygiene in learning environments. Youth & Society, 52(2), 254–272.

- Gaihre, S., Stewart, C. P., & Khan, S. (2021). WASH infrastructure and absenteeism in primary schools: Evidence from Bangladesh. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–10.

- Hirano, Y., Suzuki, S., & Yamamoto, K. (2022). School hygiene education and student health awareness in East Asia. Asian Education and Development Studies, 11(1), 40–57.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Jasper, C., Le, T.-T., & Bartram, J. (2012). Water and sanitation in schools: A systematic review of the health and educational outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(8), 2772–2787. [CrossRef]

- Karasar, N. (2020). Scientific research method (35th ed.). Nobel Publishing.

- Karataş, S., & Yılmaz, A. (2019). The relationship between classroom air quality and student attention. Education and Science, 44(197), 23–35.

- Kurt, A., & Yıldırım, H. (2019). An analysis of hygiene practices in schools. Elementary Online, 18(4), 2010–2023.

- McGinnis, J. M., Williams-Roberts, H., & Lee, H. (2020). Impact of poor sanitation in schools on student health. American Journal of Public Health, 110(6), 789–796.

- Ministry of National Education [MoNE]. (2023). Clean School and Hygiene Certification Program. https://hijyen.meb.gov.tr/.

- Oberle, E., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2016). Stress contagion in the classroom? The link between classroom teacher burnout and morning cortisol in elementary school students. Social Science & Medicine, 159, 30–37. [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, L., & Wegner, B. (2018). Environmental factors affecting student learning: The case of German schools. Building Research & Information, 46(2), 160–173.

- UNICEF. (2021). Water, sanitation and hygiene in schools: Global baseline report. https://www.unicef.org/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).