Submitted:

13 May 2025

Posted:

14 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Context and Motivation

1.2. Objectives and Methodological Approach

- (1)

- To establish precise existence conditions for toroidal solutions, leveraging modular orthomorphisms and number-theoretic constraints (Section 4).

- (2)

- To reformulate the problem topologically, modeling the board as a simplicial complex and analyzing solutions via cohomological obstructions (Section 5).

- (3)

1.3. Structure of the Article

- Section 2 surveys prior work, positioning our interdisciplinary approach against combinatorial, stochastic, and algebraic studies.

- Section 3 defines notations and foundational concepts, such as the simplicial complex and energy function .

- Section 8 summarizes our findings and outlines future directions, including dynamic and multidimensional extensions.

- An appendix provides formal proofs and computational examples, such as Table A1.

2. Related Work and Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Enumerative Combinatorics

2.2. Stochastic and Ergodic Models

2.3. Toroidal Variants

2.4. Topological and Algebraic Approaches

2.5. Graph-Theoretic Models

2.6. Combinatorial Systems and Finite Geometry

2.7. Additional Combinatorial Works

2.8. Positioning Our Work

3. Mathematical Preliminaries and Notations

3.1. Basic Notations

- : The set of positive integers.

- : The index set for an board, for any .

- : The ring of integers modulo N, modeling the toroidal board’s periodicity.

- : The symmetric group of all permutations on , representing queen configurations.

- : The set of toroidal solutions, defined in Section 4 as conflict-free permutations.

- : The greatest common divisor of integers , critical for existence conditions (Section 4).

3.2. Board Configurations as Permutations

- Classical diagonal conflict if .

- Toroidal conflict if .

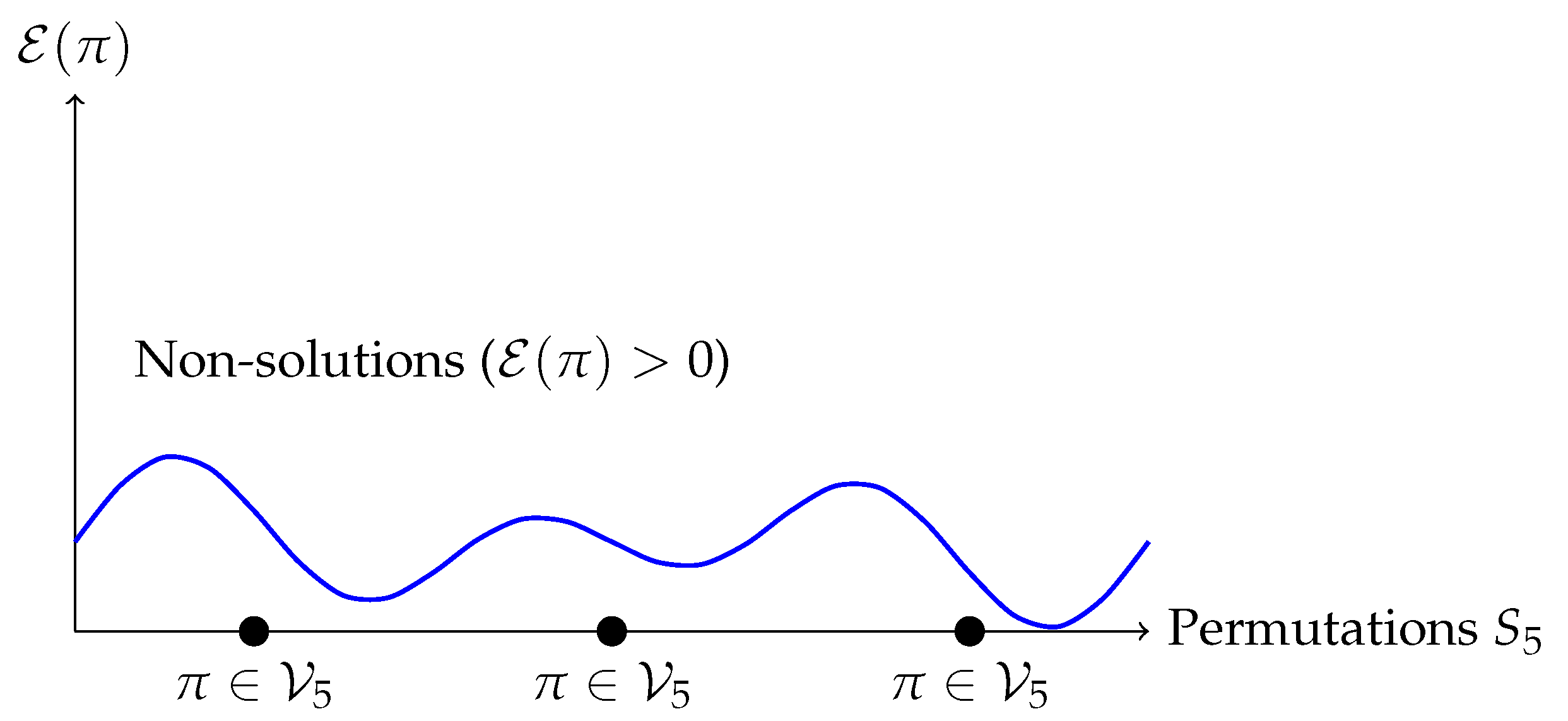

3.3. Energy Function

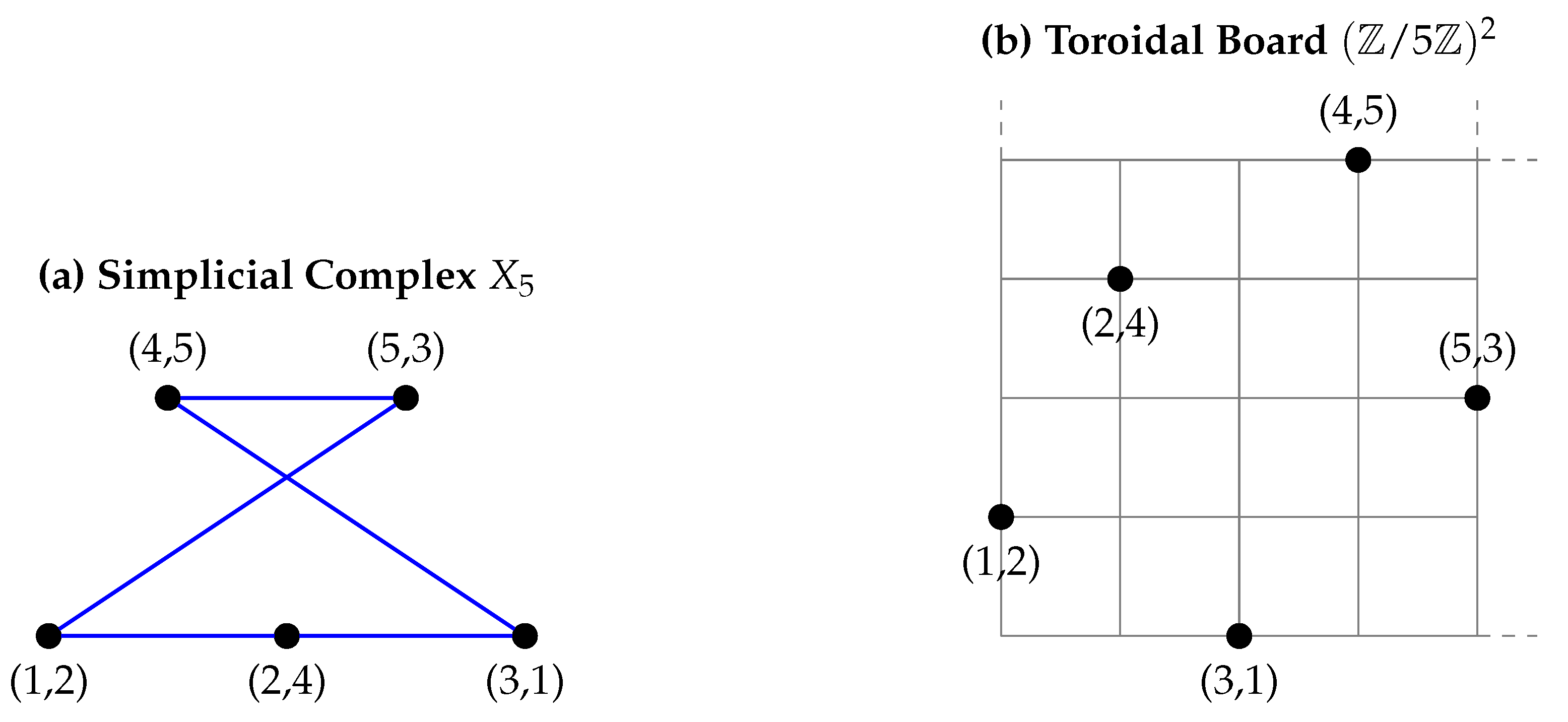

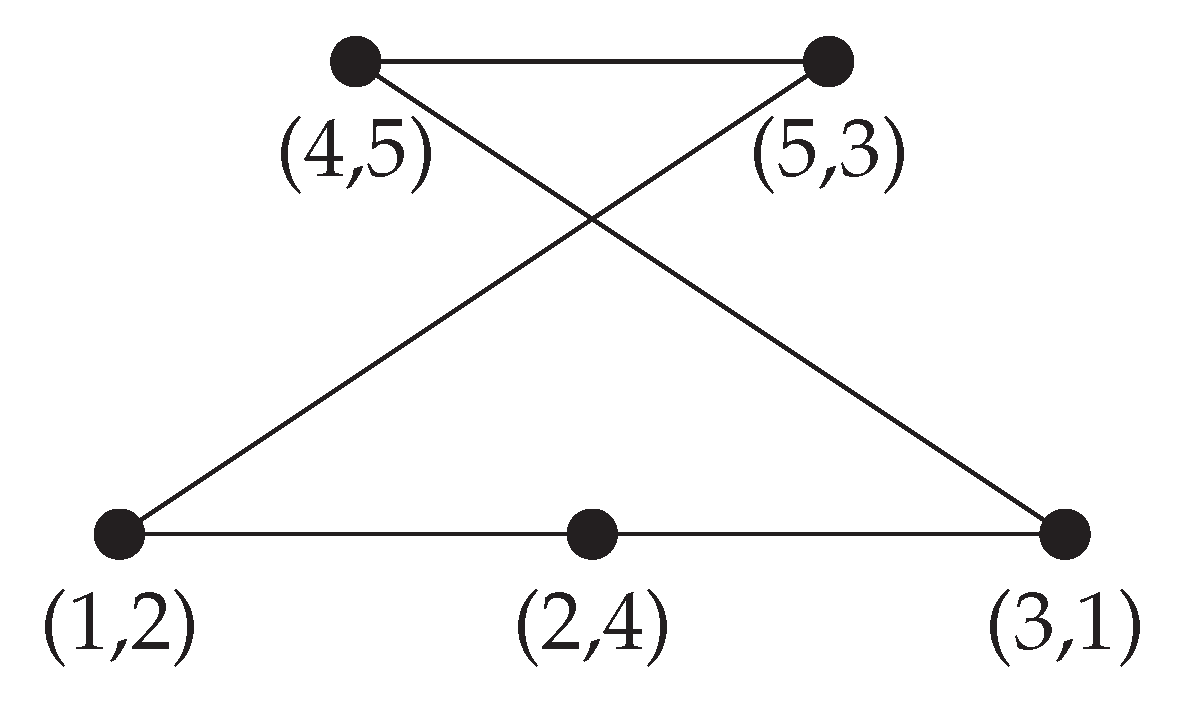

3.4. Simplicial Complex and Cohomology

- Vertex set , representing queen placements.

- 1-simplices for , included if:

3.5. Group Actions and Symmetries

- acts by translations .

- , the dihedral group of order 8, acts by rotations and reflections of the board.

- The semidirect product ⋊ combines these actions, with acting on .

4. Existence Conditions for Toroidal Solutions

4.1. Number-Theoretic Constraints

4.2. Modular Orthomorphisms

4.3. Connection to Dynamic Analyses

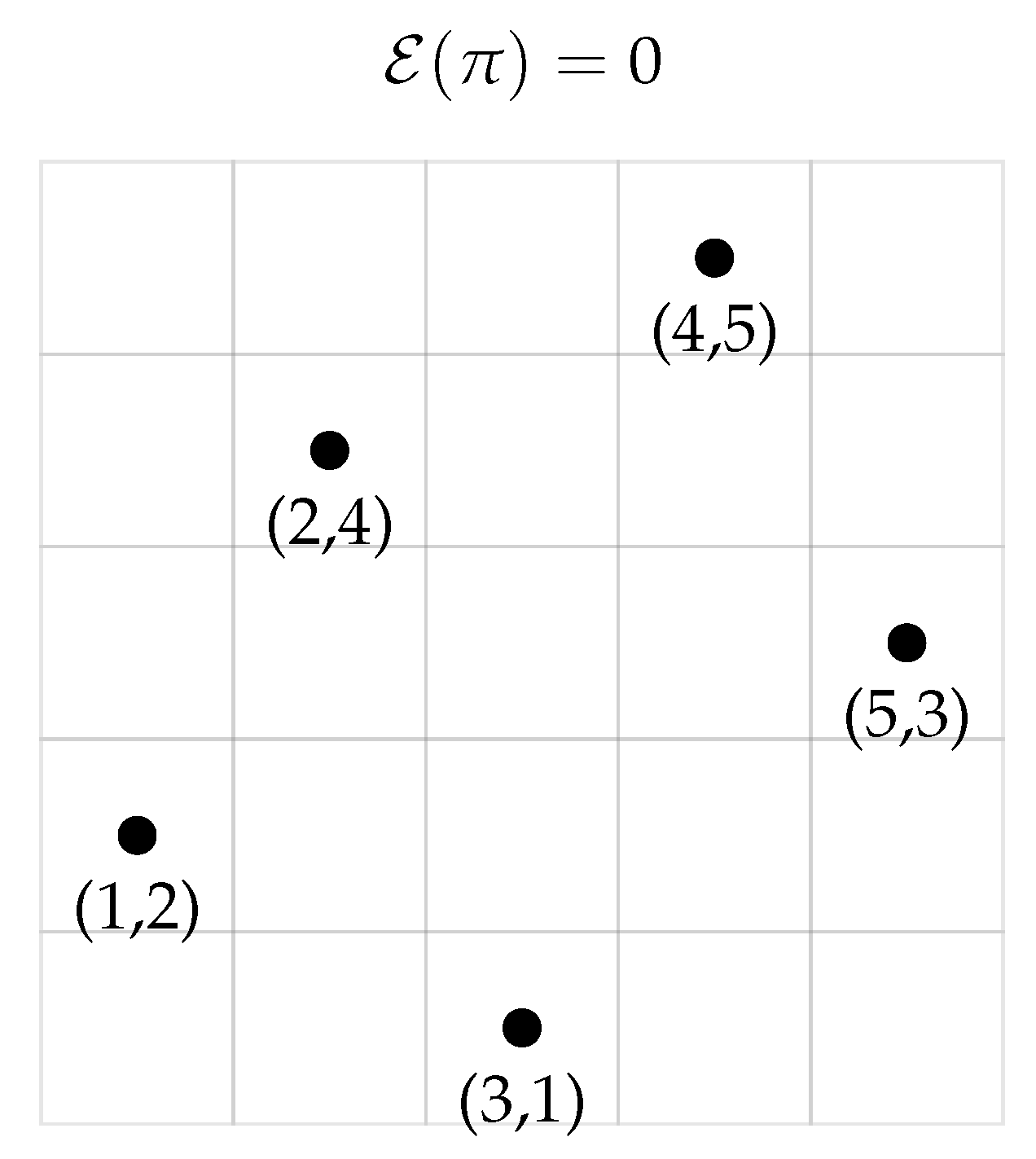

4.4. Visual Illustration

5. Topological and Cohomological Reformulation

5.1. Simplicial Complex Representation

- Vertex set , representing the positions of the queens.

- 1-simplices for , included if:

5.2. Cohomological Obstructions

- For a vertex , , representing the position of the row .

-

For an edge , , with restriction mapsand defined by the identity, encoding the modular difference .

6. Elliptic Curve Embeddings

6.1. Context: Elliptic Curves over Modular Rings

6.2. Mapping Configurations to Points on E

6.3. Applications and Numerical Visualization

6.4. Cryptographic Applications

- Security: ECDSA uses large fields; ours adds combinatorial complexity but is weaker for small N.

- Efficiency: Ours is faster for small N, leveraging future combinatorial optimizations.

- Implementation: ECDSA is standardized; ours requires custom algorithms.

- Originality: Ours is novel, building on the framework of toroidal configurations.

- Applications: Ours suits IoT, with potential extensions in future work.

7. Algebraic Structure and Stability

7.1. Toroidal Solution Space as an Algebraic Variety

7.2. Energy Function and Stability

7.3. Comparison with Classical Stability

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

8.1. Summary of Contributions

- Illustrative Examples: Through examples (e.g., , ), we illustrate , elliptic embeddings, and , contrasting our approach with stochastic methods [8].

8.2. Strengths and Limitations

- Computational Complexity: Computing or the cohomology scales poorly with N, as has elements and edge computations in are quadratic. For small N (e.g., , ), enumeration is feasible, but for , the large cardinal of poses challenges for cryptographic and coding applications.

- Parameter Selection: Constructing elliptic curves (Theorem 6.6) requires careful interpolation to ensure non-singularity (), which is challenging for composite N.

- Theoretical Focus: While we outline applications, practical algorithms (e.g., for enumerating ) are underdeveloped, limiting immediate computational impact.

8.3. Future Directions

- Cryptographic Protocols: Refining the elliptic curve-based protocols in Section 6.4 to enhance security for large , where the exponential growth of provides a larger key space, improving resistance to enumeration attacks. This requires efficient algorithms for generating , leveraging the combinatorial structure of .

- Applications in IoT and Quantum Analogs: Developing practical implementations for IoT, where the robustness of hyperstable configurations (Section 7) and modular symmetries support lightweight coding schemes. Additionally, exploring quantum analogs of , inspired by quantum constraint problems [18], could yield novel computational paradigms.

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Formal Proofs and Computations

Appendix A.1. Proof of Theorem 4.1: Existence Condition

Appendix A.2. Edge Computations for Simplicial Complex X5

Appendix A.3. Proof of Theorem 6.6: Elliptic Curve Embedding

Appendix A.4. Energy Computations for V5

Appendix A.5. Table of Toroidal Solution Existence

| N | ? | Example Permutation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 3 | No | – |

| 4 | 2 | No | – |

| 5 | 1 | Yes | (2, 4, 1, 5, 3) |

| 6 | 6 | No | – |

| 7 | 1 | Yes | (1, 3, 5, 7, 2, 4, 6) |

| 8 | 2 | No | – |

| 9 | 3 | No | – |

| 10 | 2 | No | – |

| 11 | 1 | Yes | (1, 4, 7, 10, 2, 5, 8, 11, 3, 6, 9) |

Appendix A.6. Cohomological Isomorphism for XN

Appendix A.7. Calculations for X3

Appendix A.8. Stability Calculations for π = (2,4,1,5,3)

Appendix A.9. Verification for N = 7

Appendix B. Complete Proof of Theorem 6.6

Step 1: System of Equations

Step 2: Solving for a and b

Step 3: Validation for All i∈[N]

Step 4: Ensuring Non-Singularity

- For , perturb for small k to adjust while preserving .

- For , the condition is trivial.

Step 5: Conclusion

References

- Fahiem Bacchus and Peter van Beek. On the conversion between non-binary and binary constraint satisfaction problems. Artificial Intelligence, 128(1-2):153–180, 2001.

- Jordan Bell and Brett Stevens. A survey of known results and research areas for n-queens. Discrete Mathematics, 309(1):1–31, 2009.

- Norman L. Biggs. Discrete Mathematics. Oxford University Press, 2 edition, 1989.

- Béla Bollobás. Modern Graph Theory. Springer, 1998.

- Richard A. Brualdi. Introductory Combinatorics. Pearson, 4 edition, 2004.

- Peter J. Cameron. Combinatorics: Topics, Techniques, Algorithms. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Gary Chartrand and Linda Lesniak. Graphs & Digraphs. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 3 edition, 1997.

- Persi Diaconis. Group representations in probability and statistics. Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 1988.

- Reinhard Diestel. Graph Theory. Springer, 3 edition, 2005.

- C. Godsil and G. Royle. Graphs & Combinatorics. Springer, 2001.

- Marshall Hall. A combinatorial problem on abelian groups. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 3:584–587, 1943.

- Allen Hatcher. Algebraic Topology. Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Wu-Yi Hsiang. On the toroidal n-queens problem. Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A, 106(2):249–262, 2004.

- Nicholas M. Katz and Barry Mazur. Arithmetic Moduli of Elliptic Curves. Princeton University Press, 1985.

- Donald E. Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 4: Combinatorial Algorithms. Addison-Wesley, 2000.

- Neal Koblitz. Elliptic curve cryptosystems. Mathematics of Computation, 48(177):203–209, 1987.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Digital signature standard (dss). Technical Report FIPS PUB 186-4, NIST, 2013.

- Michael A. Nielsen and Isaac L. Chuang. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- George Pólya. Über eine aufgabe der wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung betreffend die irrfahrt im straßennetz. Mathematische Annalen, 84:149–160, 1921.

- Ronald L. Rivest. A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems. Communications of the ACM, 21(2):120–126, 1978.

- Abderrahim Sabour. Stability and ergodic patterns in permutation-based optimization: The case of n-queens (part i). Preprints doi = 0.20944/preprints202505.0712.v1, 2025.

- Jean-Pierre Serre. Linear Representations of Finite Groups. Springer, 1977.

- Joseph H. Silverman. The Arithmetic of Elliptic Curves. Springer, 2 edition, 2009.

- Sloane, N.J.A. Sequence A000170: Number of ways to place n nonattacking queens on an n x n board. The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, 2023.

- Richard P. Stanley. Enumerative Combinatorics, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- W.T. Tutte. Connectivity in Graphs. University of Toronto Press, 1966.

- J.H. van Lint and R.M. Wilson. A Course in Combinatorics. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Douglas B. West. Introduction to Graph Theory. Prentice Hall, 2 edition, 2001.

- Robin J. Wilson. Introduction to Graph Theory. Longman, 4 edition, 1996.

| Component | Hsiang (2004) | This Article |

|---|---|---|

| Condition | ✓(Theorem 1) | ✓(Revisited and Extended) |

| Simplicial Complex | × | ✓(Section 5, Figure 1) |

| Elliptic Curves | × | ✓(Section 6, Theorem 6.6) |

| Stability Metric | × | ✓(Section 7, Theorem 7.5) |

| N | Solutions Exist? | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1 | Yes |

| 6 | 6 | No |

| 7 | 1 | Yes |

| 8 | 2 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).