Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

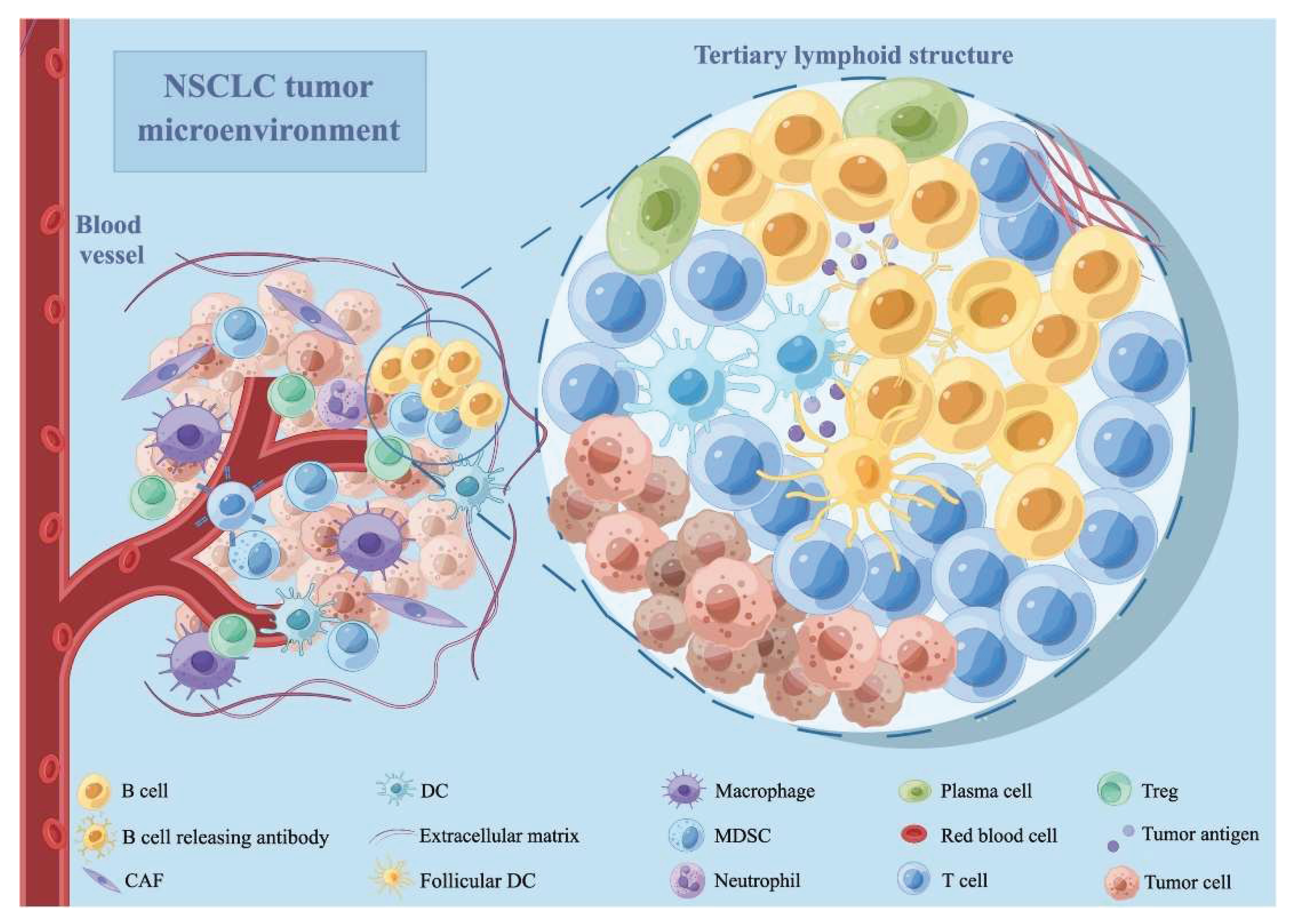

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

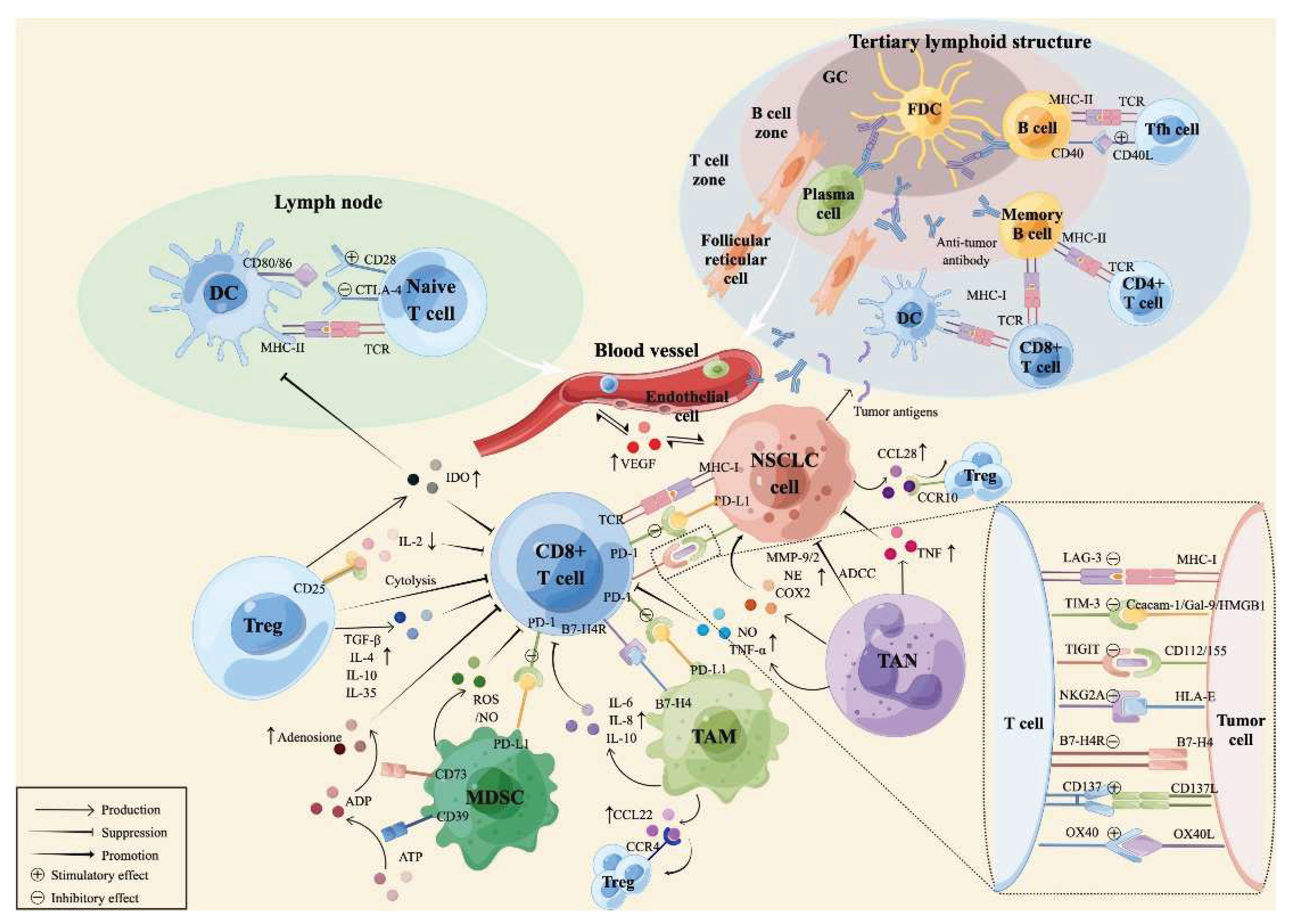

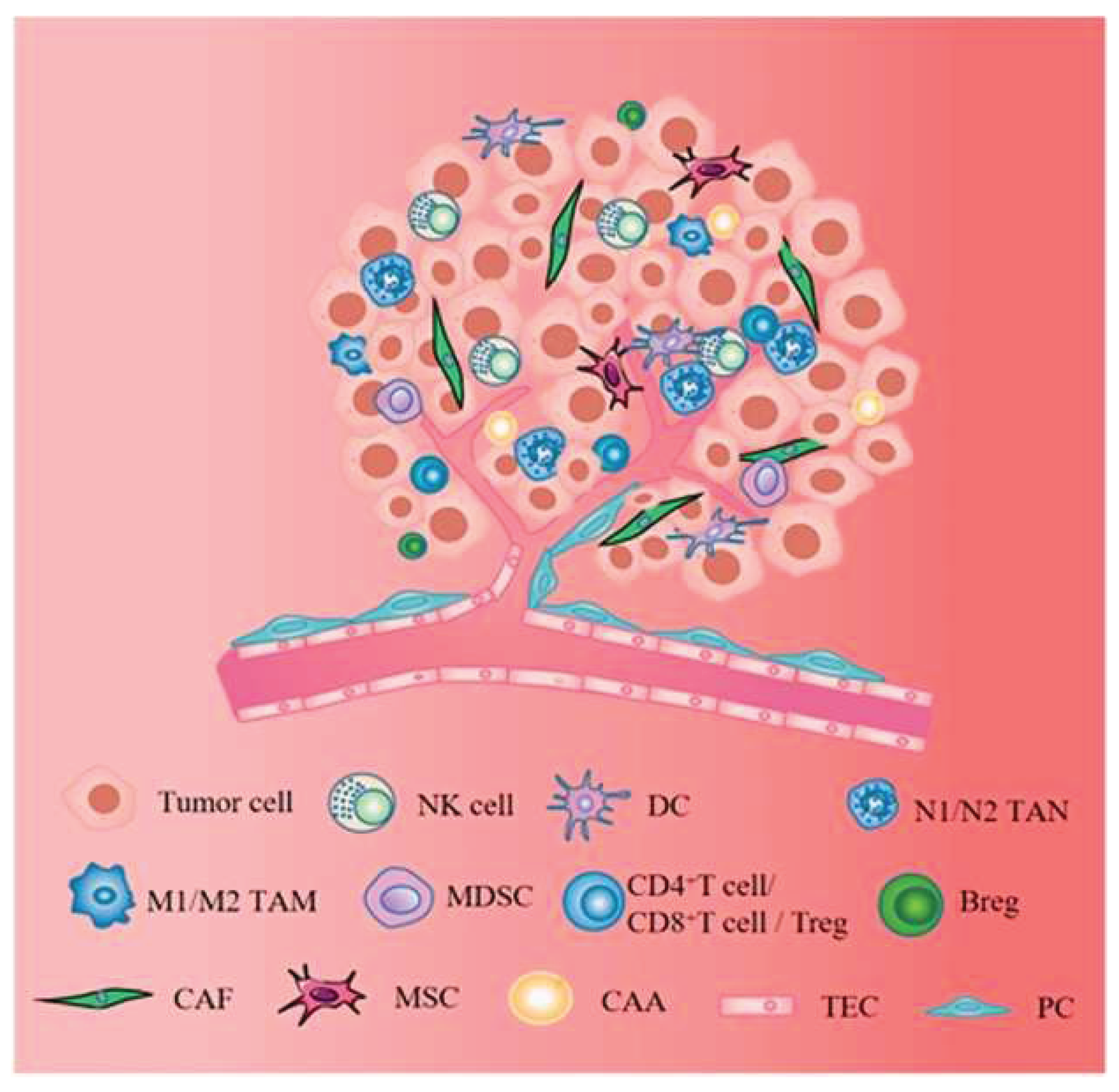

2. Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells

| Immune cell type | Main Function in TME | Clinical/Prognostic Association |

| CD8+ T cells | Cytotoxic killing of tumor cells | Improved survival, better ICI response[21],[22] |

| CD4+ T cells | Helper/regulatory roles; coordinate immune responses | Variable; subset-dependent [22,23] |

| Regulatory T cells (Tregs) | Suppress anti-tumor immunity | Poorer prognosis [22,24] |

| B cells | Antibody production, antigen presentation | Mixed; high density may predict HPD [21,25] |

| Macrophages (M1/M2) | M1: pro-inflammatory/anti-tumor; M2: immunosuppressive | M1: favorable; M2: poor prognosis [22,23,24] |

| Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) | Suppress T cell function, promote tumor growth | Poorer prognosis [22] |

| Natural Killer (NK) cells | Direct killing of tumor cells (innate immunity) | Generally favorable [23] |

| Dendritic cells (DCs) | Antigen presentation, T cell activation | It can be immunosuppressive in TME [24] |

| Mast cells | Modulate inflammation, angiogenesis | Prognostic value in LUAD [23] |

2.1. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TIL)

2.1.1. Cytotoxic CD8+ T Lymphocytes

3. Tumor Expressing Cytokines

| Cytokine | Primary Source | Target Cells | Primary Function |

| IL-1 | Monocytes, macrophages, fibroblasts | T/B cells, endothelium, hypothalamus | Co-stimulation, inflammation, fever |

| IL-2 | T cells, NK cells | T/B/NK cells, monocytes | Growth and activation of immune cells |

| IL-4 | T cells | T/B cells | Th2 differentiation, IgE switching |

| IL-6 | T cells, macrophages | T/B cells, liver | Acute phase response, inflammation |

| IL-10 | Th2 cells | Macrophages, T cells | Anti-inflammatory, suppresses APCs |

| IL-12 | Macrophages, NK cells | T cells | Promotes Th1 differentiation |

| IL-17 | NKT cells, ILCs | Epithelial, endothelial cells | Inflammation, infection control |

| IL-21 | CD4+ T cells, NKT cells | T/B/NK cells | Enhances immune responses |

| IL-23 | APCs | T cells, NK cells | Promotes chronic inflammation via Th17 |

| IFN-γ | T, NK, NKT cells | Monocytes, endothelial cells | MHC upregulation, macrophage activation |

| TNF-α | Macrophages, T cells | Immune, endothelial, liver cells | Inflammation, fever, acute-phase response |

| TGF-β | T cells, macrophages | T cells | Suppresses immune activation |

| IL-35 | Tregs | T cells | Immunosuppressive, induces iTr35 |

| IL-37 | Monocytes, DCs | Macrophages, B cells | Dampens excessive inflammation |

4. Lung Tumor Microenvironment

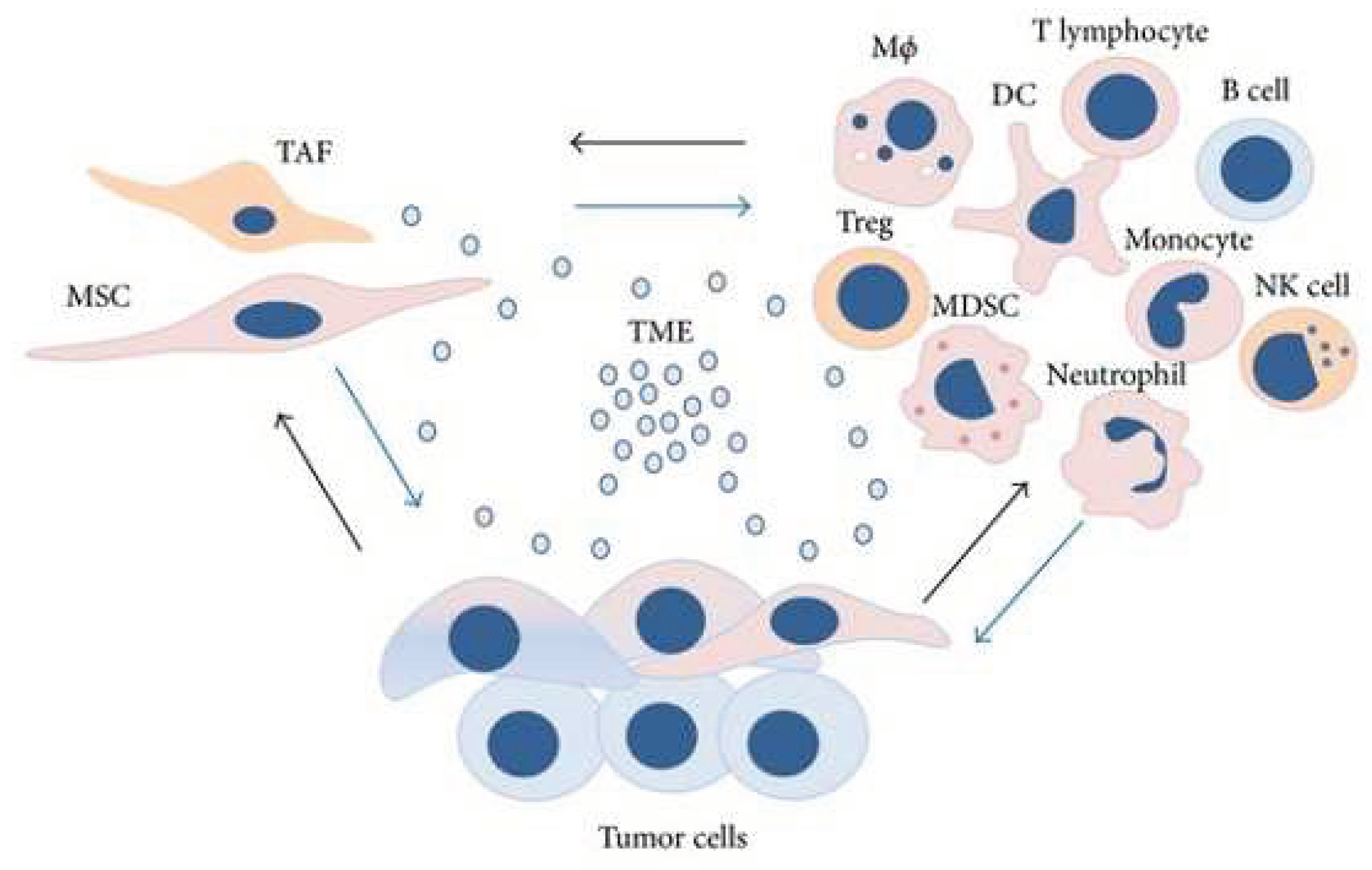

5. Cells of the Stroma

5.1. Fibroblast Cells

5.2. Immune Cells

5.2.1. T-Cells

5.2.2. Macrophages

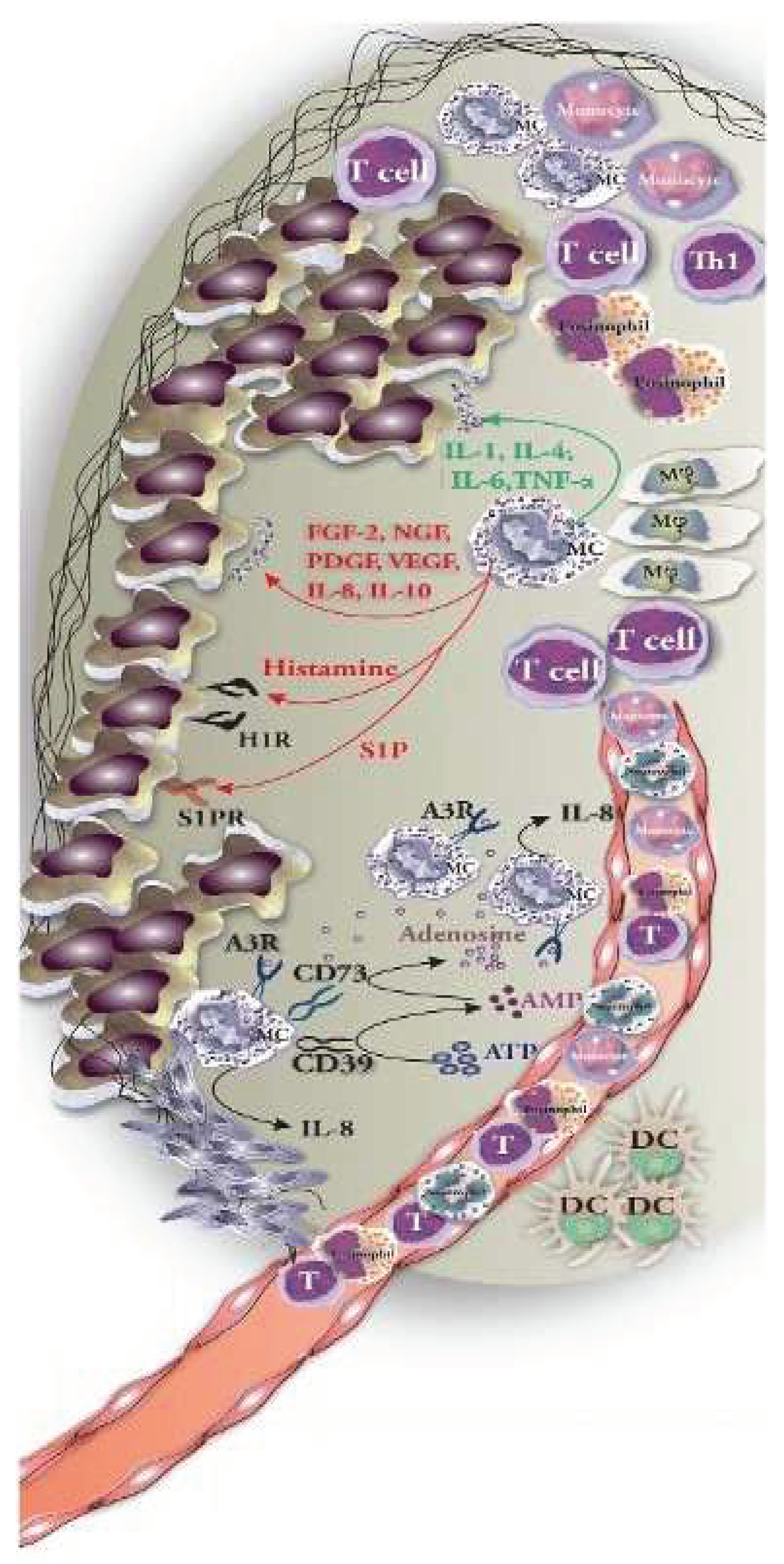

5.2.3. Mast Cells

5.2.4. Dendritic Cells

5.2.5. Vascular Cells

6. Extracellular Molecules

6.1. Cytokines

| Cytokine | Source | Functions |

| IL-6 | T-cells, macrophages, adipocytes | Proinflammatory action, promotes differentiation and cytokine production |

| IL-8 | Epithelial cells, macrophages, endothelial cells | Proinflammatory action, promotes angiogenesis and chemotaxis |

| IL-10 | Monocytes, B-cells, T-cells | Anti-inflammatory action, inhibits proinflammatory cytokines |

| IL-17 | Th17 cells | Proinflammatory action, enhances cytokine and chemokine production, contributes to antitumor immunity |

| IL-27 | Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) | Anti-inflammatory action, induces IL-10 production |

| IL-35 | Regulatory T-cells (Tregs) | Anti-inflammatory action, promotes Treg proliferation, suppresses Th17 cells |

| IL-37 | NK cells, monocytes, epithelial cells, B-cells | Anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and contributes to antitumor immunity |

| TNF-α | Macrophages, CD4+ lymphocytes, adipocytes, NK cells | Proinflammatory action, induces cell proliferation, cytokine production, and apoptosis |

| IFN-γ | NK cells, T-cells | Antiviral and proinflammatory action |

| TGF-β | T-cells, macrophages | Anti-inflammatory action, suppresses proinflammatory cytokine production |

| Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) | T-cells, macrophages, fibroblasts | Proinflammatory action, enhances neutrophil and monocyte function, activates macrophages |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) | Macrophages, endothelial cells, platelets | Promotes vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, endothelial chemotaxis, and migration |

6.2. Growth Factors

6.3. Matrix Metalloproteinase

7. Immune Regulation by Stroma

8. Hypoxia and Tumour Microenvironment

9. Role of microRNAs in Regulating Tumor Microenvironment

| microRNA | Targets | Expression status (Under-expressed/Over-expressed/ Unchanged) |

Comments (if any) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-487b | SUZ12,BM11, MYC | Over-expressed | Tumour suppressor | Xi et al, 2013 [114] |

| miR-449 | HDAC1 | Over-expressed | AM Rusek et al;2015 [113] | |

| miR-101 | EZH2 | Over-expressed | AM Rusek et al;2015 [113] | |

| miR-486 | IGF1R | Under-expressed | NSCLC-Tumour suppressor | C M. Croce et al;2013 [115] |

| miR-9 | MHC 1 gene | Over-expressed | AM Rusek et al;2015 [113] | |

| miR-124a | CDK6 | Over-expressed | Tumour suppressor | A Lujambio et al;2007 [116] |

| miR-221 | TIMP3 | Over-expressed | AM Rusek et al;2015 [113] | |

| miR-222 | TIMP3 | Over-expressed | AM Rusek et al;2015 [113] | |

| miR-429 | ZEB1/2 | Over-expressed | NSCLC- Oncogenic | Wu Cl et al;2018 [117] |

| miR-128b | EGFR in NSCLC | Under-expressed | Tumour Suppressor | Becker-Santos DD et al 2012 [118] |

| miR-1827 | SK-LU-1, RBX1 in NSCLC | Under-expressed | NSCLC- Tumour suppressor | SM Noor et al;2018 [119] |

| miR-378 | RBX1, CRKL in NSCLC | Over-expressed | NSCLC- Tumour suppressor | SM Noor et al;2018 [119] |

| miR-630 | Mut-Bcl-2-3ʹ-UTR | Unchanged | NSCLC- Tumour suppressor | Huei Lee et al;2018 [120] |

| miR-31 | LATS2/PPP2R2A | Overexpressed | NSCLC -Oncogenic | Liu et al;2010 [121] |

| miR-221/222 | PUMA | Overexpressed | NSCLC -Oncogenic | Zhang et al;2014 [122] |

| miR-197 | PD-L1 | Overexpressed | NSCLC -Oncogenic | Fujita et al; 2015 [123] |

| microRNA-146a | EGFR | Overexpressed | NSCLC- Tumour suppressor | Chen et al; 2013 [124] |

10. Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| SCLC | Small cell lung cancer |

| TME | Tumor-microenvironment |

| ICB | Immune checkpoint blockade |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells |

| TAFs | Tumor-associated fibroblasts |

| Tregs | Regulatory T-cells |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| NK | Natural killer cells |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| HIFs | Hypoxia-inducible factors |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

References

- Sica, A.; Bronte, V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mimi, M.A.; Hasan, M.; Takanashi, Y.; Waliullah, A.; Mamun, A.; Chi, Z.; Kahyo, T.; Aramaki, S.; Takatsuka, D.; Koizumi, K.; et al. UBL3 overexpression enhances EV-mediated Achilles protein secretion in conditioned media of MDA-MB-231 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 738, 150559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S. Tumor Microenvironment and Myelomonocytic Cells. BoD–Books on Demand. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstraw P, Ball D, Jett JR, et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet 2011, 378, 1727–1740. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirlog, R.; Chiroi, P.; Rusu, I.; Jurj, A.M.; Budisan, L.; Pop-Bica, C.; Braicu, C.; Crisan, D.; Sabourin, J.-C.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. Cellular and Molecular Profiling of Tumor Microenvironment and Early-Stage Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, T.S.K.; Wu, Y.-L.; Kudaba, I.; Kowalski, D.M.; Cho, B.C.; Turna, H.Z.; Castro, G., Jr.; Srimuninnimit, V.; Laktionov, K.K.; Bondarenko, I.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1819–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Paust, S. Chemokines in the tumor microenvironment: implications for lung cancer and immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1443366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Arenberg, D.; Keane, M.P.; DiGiovine, B.; Kunkel, S.L.; Morris, S.B.; Xue, Y.Y.; Burdick, M.D.; Glass, M.C.; Iannettoni, M.D.; Strieter, R.M. Epithelial-neutrophil activating peptide (ENA-78) is an important angiogenic factor in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 102, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wang, J.; Lee, P.; Sharma, S.; Mao, J.T.; Meissner, H.; Uyemura, K.; Modlin, R.; Wollman, J.; Dubinett, S.M. Human non-small cell lung cancer cells express a type 2 cytokine pattern. . 1995, 55, 3847–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jover, R.; Nguyen, T.; Pérez–Carbonell, L.; Zapater, P.; Payá, A.; Alenda, C.; Rojas, E.; Cubiella, J.; Balaguer, F.; Morillas, J.D.; et al. 5-Fluorouracil Adjuvant Chemotherapy Does Not Increase Survival in Patients With CpG Island Methylator Phenotype Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasarao, D.A.; Shah, S.; Famta, P.; Vambhurkar, G.; Jain, N.; Pindiprolu, S.K.S.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, R.; Padhy, H.P.; Kumari, M.; et al. Unravelling the role of tumor microenvironment responsive nanobiomaterials in spatiotemporal controlled drug delivery for lung cancer therapy. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2024, 15, 407–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag, S.M.; Toma, S.N.; Morshed, N.; Imon, A.I.; Islam, M.; Piash, I.; Shahria, N.; Mahmud, I. Exploration of analgesic and anthelmintic activities of Artocarpus chaplasha ROXB. leaves supported by in silico molecular docking. Phytomedicine Plus 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang S, Chung JYF, Li C, et al. Cellular dynamics of tumor microenvironment driving immunotherapy resistance in non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Lett. Published online 2024, 217272. [Google Scholar]

- Riera-Domingo C, Audigé A, Granja S, et al. Immunity, hypoxia, and metabolism–the Ménage à Trois of cancer: implications for immunotherapy. Physiol Rev. 2020, 100, 1–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed Issa B, Adhab AH, Salih Mahdi M, et al. Decoding the complex web: cellular and molecular interactions in the lung tumour microenvironment. J Drug Target. 2025, 33, 666–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shackleton, M.; Vaillant, F.; Simpson, K.J.; Stingl, J.; Smyth, G.K.; Asselin-Labat, M.-L.; Wu, L.; Lindeman, G.J.; Visvader, J.E. Generation of a functional mammary gland from a single stem cell. Nature 2006, 439, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, G.; Hou, Z. The prognostic landscape of tumor-infiltrating immune cell and immunomodulators in lung cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 95, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Bruggen P, Van Pel A. Tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes. Annu Rev, Immunol. 1994, 12, 337–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, G.P.; Old, L.J.; Schreiber, R.D. The Immunobiology of Cancer Immunosurveillance and Immunoediting. Immunity 2004, 21, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Nguyen, T.T.; Tang, M.; Wang, X.; Jiang, C.; Liu, Y.; Gorlov, I.; Gorlova, O.; Iafrate, J.; Lanuti, M.; et al. Immune Infiltration in Tumor and Adjacent Non-Neoplastic Regions Codetermines Patient Clinical Outcomes in Early-Stage Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 1184–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Barnes, T.; Amir, E. HYPE or HOPE: the prognostic value of infiltrating immune cells in cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Ding, J.; Chu, Y.; Zhou, X. The relationship between tumor infiltrating immune cells and the prognosis of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Dis. 2023, 15, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffens, S.; Kayser, C.; Roesner, A.; Rawluk, J.; Schmid, S.; Gkika, E.; Kayser, G. Low densities of immune cells indicate unfavourable overall survival in patients suffering from squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, B.M.; Kim, Y.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, S.; Sun, J.; Lee, S.; Ahn, J.S.; Park, K.; Ahn, M. Tumor infiltrated immune cell types support distinct immune checkpoint inhibitor outcomes in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Immunol. 2021, 51, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Yang, M.; Luo, W.; Zhou, Q. Characteristics of tumor microenvironment and novel immunotherapeutic strategies for non-small cell lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 2022, 2, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Shao, Y.; He, W.; Hu, W.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, C.; Jiang, J. Prognostic Role of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Lung Cancer: a Meta-Analysis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 37, 1560–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinay, D.S.; Ryan, E.P.; Pawelec, G.; Talib, W.H.; Stagg, J.; Elkord, E.; Lichtor, T.; Decker, W.K.; Whelan, R.L.; Kumara, H.M.C.S.; et al. Immune evasion in cancer: Mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 35, S185–S198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Stary, C.M.; Gao, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, Z.; Jian, Z.; Gu, L.; Xiong, X. Genetically Modified T-Cell-Based Adoptive Immunotherapy in Hematological Malignancies. J. Immunol. Res. 2017, 2017, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, T.E.; Burke, K.P.; Van Allen, E.M. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walunas, T.L.; Lenschow, D.J.; Bakker, C.Y.; Linsley, P.S.; Freeman, G.J.; Green, J.M.; Thompson, C.B.; Bluestone, J.A. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity 1994, 1, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Luo, H.; Wu, L.; et al. Massive PD-L1 and CD8 double positive TILs characterize an immunosuppressive microenvironment with high mutational burden in lung cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee S, Margolin K. Cytokines in cancer immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2011, 3, 3856–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochman, Y.; Spolski, R.; Leonard, W.J. New insights into the regulation of T cells by γc family cytokines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essogmo, F.E.; Zhilenkova, A.V.; Tchawe, Y.S.N.; Owoicho, A.M.; Rusanov, A.S.; Boroda, A.; Pirogova, Y.N.; Sangadzhieva, Z.D.; Sanikovich, V.D.; Bagmet, N.N.; et al. Cytokine Profile in Lung Cancer Patients: Anti-Tumor and Oncogenic Cytokines. Cancers 2023, 15, 5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotenko, S.V.; Pestka, S. Jak-Stat signal transduction pathway through the eyes of cytokine class II receptor complexes. Oncogene 2000, 19, 2557–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilcek, J. Novel interferons. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, H.C.; Gamero, A.M. Interferon-Lambda as a Potential Therapeutic Agent in Cancer Treatment. J. Interf. Cytokine Res. 2010, 30, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, C.J.; Besse, B.; Gualberto, A.; Brambilla, E.; Soria, J.-C. The Evolving Role of Histology in the Management of Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 5311–5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Grivennikov, S.; Karin, M. Inflammation and oncogenesis: a vicious connection. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2010, 20, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valastyan, S.; Weinberg, R.A. Tumor Metastasis: Molecular Insights and Evolving Paradigms. Cell 2011, 147, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessenbrock, K.; Plaks, V.; Werb, Z. Matrix Metalloproteinases: Regulators of the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell 2010, 141, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzali, G. The modality of transendothelial passage of lymphocytes and tumor cells in the absorbing lymphatic vessel. . 2007, 73–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chunhacha, P.; Chanvorachote, P. Roles of caveolin-1 on anoikis resistance in non small cell lung cancer. . 2012, 4, 149–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Mehdi, A.B.; Tozawa, K.; Fisher, A.B.; Shientag, L.; Lee, A.; Muschel, R.J. Intravascular origin of metastasis from the proliferation of endothelium-attached tumor cells: A new model for metastasis. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, A.F.; Groom, A.C.; MacDonald, I.C. Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.P.; Nguyen, D.X.; Chiang, A.C.; Bos, P.D.; Kim, J.Y.; Nadal, C.; Gomis, R.R.; Manova-Todorova, K.; Massagué, J. Mediators of vascular remodelling co-opted for sequential steps in lung metastasis. Nature 2007, 446, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaila, B.; Lyden, D. The metastatic niche: adapting the foreign soil. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erler, J.T.; Bennewith, K.L.; Cox, T.R.; Lang, G.; Bird, D.; Koong, A.; Le, Q.-T.; Giaccia, A.J. Hypoxia-Induced Lysyl Oxidase Is a Critical Mediator of Bone Marrow Cell Recruitment to Form the Premetastatic Niche. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Siegel, P.M.; Shu, W.; Drobnjak, M.; Kakonen, S.M.; Cordón-Cardo, C.; Guise, T.A.; Massagué, J. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.X.; Bos, P.D.; Massague, J. Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.S. Publication Status of Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast Cells in Scientific Journals. Eur. J. Ther. 2021, 27, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasek, J.J.; Gabbiani, G.; Hinz, B.; Chaponnier, C.; Brown, R.A. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsonage, G.; Filer, A.D.; Haworth, O.; Nash, G.B.; Rainger, G.E.; Salmon, M.; Buckley, C.D. A stromal address code defined by fibroblasts. Trends Immunol. 2005, 26, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodemann, H.P.; Müller, G.A. Characterization of Human Renal Fibroblasts in Health and Disease: II. In Vitro Growth, Differentiation, and Collagen Synthesis of Fibroblasts From Kidneys With Interstitial Fibrosis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1991, 17, 684–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.Y.; Chi, J.-T.; Dudoit, S.; Bondre, C.; van de Rijn, M.; Botstein, D.; Brown, P.O. Diversity, topographic differentiation, and positional memory in human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 12877–12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmouliere, A.; Guyot, C.; Gabbiani, G. The stroma reaction myofibroblast: a key player in the control of tumor cell behavior. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2004, 48, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erez, N.; Truitt, M.; Olson, P.; Hanahan, D. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Are Activated in Incipient Neoplasia to Orchestrate Tumor-Promoting Inflammation in an NF-κB-Dependent Manner. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schliekelman, M.J.; Creighton, C.J.; Baird, B.N.; Chen, Y.; Banerjee, P.; Bota-Rabassedas, N.; Ahn, Y.-H.; Roybal, J.D.; Chen, F.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Thy-1+ Cancer-associated Fibroblasts Adversely Impact Lung Cancer Prognosis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6478–6478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintani, Y.; Kimura, T.; Funaki, S.; Ose, N.; Kanou, T.; Fukui, E. Therapeutic Targeting of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in the Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers 2023, 15, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Shen M, Wu L, et al. Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment: accomplices of tumor progression? Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Hu, S.; Liu, Q.; Qian, C.; Liu, Z.; Luo, D. Exosomal microRNA remodels the tumor microenvironment. PeerJ 2017, 5, e4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seager, R.J.; Hajal, C.; Spill, F.; Kamm, R.D.; Zaman, M.H. Dynamic interplay between tumour, stroma and immune system can drive or prevent tumour progression. Converg. Sci. Phys. Oncol. 2017, 3, 034002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.A.; Arpaia, N.; Schizas, M.; Dobrin, A.; Rudensky, A.Y. A nonimmune function of T cells in promoting lung tumor progression. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 3565–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Huang, K.; Lin, H.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Jin, J. Mogroside IIE Inhibits Digestive Enzymes via Suppression of Interleukin 9/Interleukin 9 Receptor Signalling in Acute Pancreatitis. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, B.; Lin, Y.; Navin, N. Advancing Cancer Research and Medicine with Single-Cell Genomics. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Sozzani, S.; Locati, M.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002, 23, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostuni, R.; Kratochvill, F.; Murray, P.J.; Natoli, G. Macrophages and cancer: from mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, A.; Holthoff, E.; Vadali, S.; Kelly, T.; Post, S.R. Cleavage of Type I Collagen by Fibroblast Activation Protein-α Enhances Class A Scavenger Receptor Mediated Macrophage Adhesion. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0150287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.E.; Pollard, J.W. Distinct Role of Macrophages in Different Tumor Microenvironments. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingle, L.; Brown, N.; Lewis, C.E. The role of tumour-associated macrophages in tumour progression: implications for new anticancer therapies. J. Pathol. 2002, 196, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway EM, Pikor LA, Kung SHY, et al. Macrophages, inflammation, and lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016, 193, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edin S, Wikberg ML, Oldenborg PA, Palmqvist R. Macrophages: Good guys in colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e23038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivanović, D.; Krstić, J.; Djordjević, I.O.; Mojsilović, S.; Santibanez, J.F.; Bugarski, D.; Jauković, A. The Roles of Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells in Tumor Microenvironment Associated with Inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, S.J.; Tsai, M. Mast cells in allergy and infection: Versatile effector and regulatory cells in innate and adaptive immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010, 40, 1843–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, L.; Gisfredi, S.; Ursino, S.; Lucchi, M.; Melfi, F.; Mussi, A.; Basolo, F.; Fontanini, G. Tumour necrosis factor-α: prognostic role and relationship with interleukin-8 and endothelin-1 in non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2006, 17, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komi, D.E.A.; Redegeld, F.A. Role of Mast Cells in Shaping the Tumor Microenvironment. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimpean, A.M.; Tamma, R.; Ruggieri, S.; Nico, B.; Toma, A.; Ribatti, D. Mast cells in breast cancer angiogenesis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2017, 115, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, G.-Y.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, S.E.; Han, H.D.; Hong, K.-J.; Kang, T.H.; Park, Y.-M. Interactions between tumor-derived proteins and Toll-like receptors. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1926–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudziak, D.; Kamphorst, A.O.; Heidkamp, G.F.; Buchholz, V.R.; Trumpfheller, C.; Yamazaki, S.; Cheong, C.; Liu, K.; Lee, H.-W.; Park, C.G.; et al. Differential Antigen Processing by Dendritic Cell Subsets in Vivo. Science 2007, 315, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts EW, Broz ML, Binnewies M, et al. Critical role for CD103+/CD141+ dendritic cells bearing CCR7 for tumor antigen trafficking and priming of T cell immunity in melanoma. Cancer Cell. 2016, 30, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, J.P.; Bonavita, E.; Chakravarty, P.; Blees, H.; Cabeza-Cabrerizo, M.; Sammicheli, S.; Rogers, N.C.; Sahai, E.; Zelenay, S.; e Sousa, C.R. NK Cells Stimulate Recruitment of cDC1 into the Tumor Microenvironment Promoting Cancer Immune Control. Cell 2018, 172, 1022–1037.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.C.; Gudjonson, H.; Pritykin, Y.; Deep, D.; Lavallée, V.-P.; Mendoza, A.; Fromme, R.; Mazutis, L.; Ariyan, C.; Leslie, C.; et al. Transcriptional Basis of Mouse and Human Dendritic Cell Heterogeneity. Cell 2019, 179, 846–863.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canton, J.; Blees, H.; Henry, C.M.; Buck, M.D.; Schulz, O.; Rogers, N.C.; Childs, E.; Zelenay, S.; Rhys, H.; Domart, M.-C.; et al. The receptor DNGR-1 signals for phagosomal rupture to promote cross-presentation of dead-cell-associated antigens. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 22, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giampazolias, E.; Schulz, O.; Lim, K.H.J.; Rogers, N.C.; Chakravarty, P.; Srinivasan, N.; Gordon, O.; Cardoso, A.; Buck, M.D.; Poirier, E.Z.; et al. Secreted gelsolin inhibits DNGR-1-dependent cross-presentation and cancer immunity. Cell 2021, 184, 4016–4031.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, P.; Ahluwalia, M.; Mondal, A.K.; Sahajpal, N.S.; Kota, V.; Rojiani, M.V.; Kolhe, R. Natural Killer Cells and Dendritic Cells: Expanding Clinical Relevance in the Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers 2021, 13, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature 2005, 438, 932–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, H.F. Angiogenesis: update 2005. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005, 3, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D.; Ennas, M.G.; Vacca, A.; Ferreli, F.; Nico, B.; Orru, S.; Sirigu, P. Tumor vascularity and tryptase-positive mast cells correlate with a poor prognosis in melanoma. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 33, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, K.A.; Cho, D.S.; Arneson, P.C.; Samani, A.; Palines, P.; Yang, Y.; Doles, J.D. Tumor-derived cytokines impair myogenesis and alter the skeletal muscle immune microenvironment. Cytokine 2018, 107, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeta, V.M.; Massara, M.; Capucetti, A.; Bonecchi, R. Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors: New Targets for Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarode, P.; Schaefer, M.B.; Grimminger, F.; Seeger, W.; Savai, R. Macrophage and Tumor Cell Cross-Talk Is Fundamental for Lung Tumor Progression: We Need to Talk. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Stolina, M.; Sharma, S.; Mao, J.T.; Zhu, L.; Miller, P.W.; Wollman, J.; Herschman, H.; Dubinett, S.M. Non-small cell lung cancer cyclooxygenase-2-dependent regulation of cytokine balance in lymphocytes and macrophages: up-regulation of interleukin 10 and down-regulation of interleukin 12 production. . 1998, 58, 1208–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, S.; Verma, A.K.; Dev, K.; Goyal, Y.; Bhatt, D.; Alsahli, M.A.; Rahmani, A.H.; Almatroudi, A.; Almatroodi, S.A.; Alrumaihi, F.; et al. Role of Cytokines and Chemokines in NSCLC Immune Navigation and Proliferation. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5563746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendler, F.J.; Ozanne, B.W. Human squamous cell lung cancers express increased epidermal growth factor receptors. J. Clin. Investig. 1984, 74, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Normanno, N.; De Luca, A.; Bianco, C.; Strizzi, L.; Mancino, M.; Maiello, M.R.; Carotenuto, A.; De Feo, G.; Caponigro, F.; Salomon, D.S. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling in cancer. Gene 2006, 366, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non–small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. Jama 2003, 290, 2149–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page-McCaw, A.; Ewald, A.J.; Werb, Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.; Lapiere, C.M. COLLAGENOLYTIC ACTIVITY IN AMPHIBIAN TISSUES: A TISSUE CULTURE ASSAY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1962, 48, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, S.; Huang, L.; He, J.; Liu, G.; Ma, S.; Weng, Y.; Huang, S. Systemic immune microenvironment and regulatory network analysis in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Transl. Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 2859–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, B.; Rosicarelli, B.; Magliozzi, R.; Stigliano, E.; Aloisi, F. Detection of Ectopic B-cell Follicles with Germinal Centers in the Meninges of Patients with Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2004, 14, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Rosenberg, S.; Yang, J.C.; Restifo, N.P. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Wilson, W.R. Exploiting tumour hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Zhao L, Li XF. Hypoxia and the tumor microenvironment. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2021, 20, 15330338211036304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedogni, B.; Powell, M.B. Hypoxia, melanocytes and melanoma – survival and tumor development in the permissive microenvironment of the skin. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2009, 22, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.A.; Sutphin, P.D.; Denko, N.C.; Giaccia, A.J. Role of Prolyl Hydroxylation in Oncogenically Stabilized Hypoxia-inducible Factor-1α. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 40112–40117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, N.; Willam, C.; Maxwell, P.H.; Pugh, C.W.; Ratcliffe, P.J. Independent function of two destruction domains in hypoxia-inducible factor-α chains activated by prolyl hydroxylation. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 5197–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, A.; Kwon, I.; Tae, G. Improving cancer therapy through the nanomaterials-assisted alleviation of hypoxia. Biomaterials 2020, 228, 119578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otmani, K.; Lewalle, P. Tumor Suppressor miRNA in Cancer Cells and the Tumor Microenvironment: Mechanism of Deregulation and Clinical Implications. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmero, E.I.; de Campos, S.G.P.; Campos, M.; de Souza, N.C.N.; Guerreiro, I.D.C.; Carvalho, A.L.; Marques, M.M.C. Mechanisms and role of microRNA deregulation in cancer onset and progression. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2011, 34, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee YS, Dutta A. MicroRNAs in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2009, 4, 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon R, Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNAs in cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2009, 60, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusek, A.M.; Abba, M.; Eljaszewicz, A.; Moniuszko, M.; Niklinski, J.; Allgayer, H. MicroRNA modulators of epigenetic regulation, the tumor microenvironment and the immune system in lung cancer. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 34–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, S.; Xu, H.; Shan, J.; Tao, Y.; Hong, J.A.; Inchauste, S.; Zhang, M.; Kunst, T.F.; Mercedes, L.; Schrump, D.S. Cigarette smoke mediates epigenetic repression of miR-487b during pulmonary carcinogenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 1241–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Dai, Y.; Hitchcock, C.; Yang, X.; Kassis, E.S.; Liu, L.; Luo, Z.; Sun, H.-L.; Cui, R.; Wei, H.; et al. Insulin growth factor signaling is regulated by microRNA-486, an underexpressed microRNA in lung cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 15043–15048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujambio, A.; Ropero, S.; Ballestar, E.; Fraga, M.F.; Cerrato, C.; Setién, F.; Casado, S.; Suarez-Gauthier, A.; Sanchez-Cespedes, M.; Gitt, A.; et al. Genetic Unmasking of an Epigenetically Silenced microRNA in Human Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 1424–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ho, J.; Hung, S.; Yu, D. miR-429 expression in bladder cancer and its correlation with tumor behavior and clinical outcome. Kaohsiung J. Med Sci. 2018, 34, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubaux R, Becker-Santos DD, Enfield KSS, Lam S, Lam WL, Martinez VD. MicroRNAs As Biomarkers For Clinical Features Of Lung Cancer. Metabolomics open access. 2012, 2, 1000108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Ho C, Noor SM, Nagoor NH. MiR-378 and MiR-1827 regulate tumor invasion, migration and angiogenesis in human lung adenocarcinoma by targeting RBX1 and CRKL, respectively. J Cancer 2018, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-J.; Wu, D.-W.; Wang, G.-C.; Wang, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lee, H. MicroRNA-630 may confer favorable cisplatin-based chemotherapy and clinical outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer by targeting Bcl-2. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 13758–13767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Sempere, L.F.; Ouyang, H.; Memoli, V.A.; Andrew, A.S.; Luo, Y.; Demidenko, E.; Korc, M.; Shi, W.; Preis, M.; et al. MicroRNA-31 functions as an oncogenic microRNA in mouse and human lung cancer cells by repressing specific tumor suppressors. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, A.; Wang, Y.; Han, L.; You, Y.; Pu, P. PUMA is a novel target of miR-221/222 in human epithelial cancers. Int. J. Oncol. 2010, 37, 1621–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Yagishita, S.; Hagiwara, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Kosaka, N.; Takeshita, F.; Fujiwara, T.; Tsuta, K.; Nokihara, H.; Tamura, T.; et al. The Clinical Relevance of the miR-197/CKS1B/STAT3-mediated PD-L1 Network in Chemoresistant Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Umelo, I.A.; Lv, S.; Teugels, E.; Fostier, K.; Kronenberger, P.; Dewaele, A.; Sadones, J.; Geers, C.; De Grève, J. miR-146a Inhibits Cell Growth, Cell Migration and Induces Apoptosis in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e60317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sounni NE, Noel A. Targeting the tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy. Clin Chem. 2013, 59, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma-Rodrigues C, Mendes R, Baptista P V, Fernandes AR. Targeting tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.M.; Marabelle, A.; Eggermont, A.; Soria, J.-C.; Kroemer, G.; Zitvogel, L. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: removing obstruction to anticancer immune responses and immunotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).