1. Introduction

The potential of remote sensing (RS) data and Geographical Information System (GIS) techniques are emerging in the area of hydrological studies and water resource management from past decades. The open accessed high spatial and temporal satellite data has enabled us to assess the short term and long-term geographical changes for a large area at different times and space [

1]. The wide applicability of multi-sensor, multi-spectral, and multi-temporal satellite data has revolutionized the methodological approaches for delineating and evaluating groundwater potential zones and their effectiveness [

2]. These maps have sufficient details and are of multiple domains like Geology, soil type, climate, economic development, and population maps.

Lineaments are the linear features on the crust that represent fractures, faults, and other linear features. Lineaments map is a well-known topic in different disciplines to resolve certain difficulties in the area. For example, in site selection for road construction, dams, bridges, etc., for assessment of landslide and the seismic possibility for mineral assessment for hot springs recognition and hydrogeological explorations [

3] the environment and the range of the lineaments should be acknowledged. Satellite and airborne images are extensively used to extract lineaments in the perspective of different research problems [

4]. Since satellite images are acquired with different wavelength intervals of the electromagnetic spectrum, they are considered to be a better tool to recognize the lineaments and make preferred data over regular airborne photographs [

5].

Quality and availability of digital maps have been improved in recent few years, however, local conditions still required to be determined. United States Agency for International Development in cooperation with the Ministry of Water and Irrigation Jordan carried out a study in 1996 for weather conditions, suitability in favour of artificial recharge by surface runoff water [

6]. This study was focused on two areas of interest Wadi Butam and Wadi Madoneh near the Amman border, conclusions were drawn that Wadi Madoneh has the best conditions for the implementation of artificial recharge which is mainly based on lithological factor. The first studies were carried out by Al Qaisi, (2008) to assess the utilization of available storm water for infiltration and construction of suitable infrastructure. Hard rock terrains the groundwater is essentially confined to weathered and fractured aquifers. Porosity mainly controls the infiltration of water in aquifers however in hard rocks secondary porosity does so [

7].

Artificial replenishment supplements the natural penetration of water into the ground and increases the production of groundwater. Sitender [

8] used analytical hierarchy process on thematic layers prepared by using Landsat 7 ETM+ data to delineate artificial recharge.

In artificial recharge, the sites that are marked after applying different analysing techniques to the corresponding data are considered as suitable sites. Remote sensing data was used for the delineation of suitable sites in Bankura district India. Study was carried out using weighted overlay method in the GIS environment for the assessment of suitable sites and used water wells yielding data for cross-validation of his analysis [

7]. Similarly, different researchers in different time frames used varying techniques in the respective domain to get desired results [

9,

10,

11].

Healy and Cook [

12] displayed a brilliant examination of the hypothesis and utilization of the water table variance technique for assessing revives; they recognized the accompanying confinements in the water table variance technique. Groundwater availability in hard rock terrains is of limited extent due to low infiltration rate in comparison with low land planer horizons otherwise it is confined to the weathered and fractured horizon in rocks [

13]. Overlay analysis of spatial themes has been practiced in central and South America, Africa, and Asia for artificial recharge [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], and many researchers have suggested artificial recharge to aquifers based on geologic and geomorphic analysis with less emphasis on subsurface hydrological and stratigraphic data. Remote Sensing data of moderate resolution is very suitable for the identification of artificial recharge locations, drawn by lineaments and other stochastic techniques [

2].

2. Study Area

The study area is Quetta, capital of province Baluchistan of Pakistan, which lies between 29.65°N–30.41°N latitude to 66.83°E–67.31°E longitude, covering an area of 9549 km

2. The estimated population of the study area is about 1,099546 with a growth rate of 2.74%. It is situated at the west of Sibi district of Balochistan Province, South-west Pakistan, and is covered by Geological Survey of Pakistan map no 350/13 and 35/16 (

Figure 1). The relief of the study area lies between 370 to 3576 meters from sea level [

20].

Most of the wells in the investigation zone extract water from the thick alluvial stores in the valley [

21]; less groundwater is being extracted from the bedrock aquifers. The thicker most alluvial aquifer from all surrounding areas is found in the central Quetta valley, these alluvial aquifers are in contact with the underlying sandstone aquifers of the Bostan Formation and Chiltan limestone [

22].

The Quetta River Valley is located at the convergence boundary of the Indian and Eurasian plates. The surface water sources are mainly from three major streams: Pishin Lora, Surkhab Lora, and Sariab Lora. PL is located at the northwest end of the study area, flowing from north to south has a dry to semi-arid climate, and the area continues to have western disturbances and thunderstorms [

23]. In 2012, the maximum rainfall of about 61 mm was recorded in the last quarter of each month. The monsoon rarely enters the area; however, if it is strong enough to reach the Quetta Valley from northern Pakistan, it causes some rainfall and snowfall. Khan, et al. [

24] observed the precipitation data of the Quetta valley region from 1998 to 2005 concludes that the area faces scarce hydrologic conditions due to fewer rainfalls in the duration. The spin karez and other ground reservoirs dried down completely due to high temperatures and low rainfalls.

The area under study is divided into four aquifer systems. The aquifer at the top lies in an alluvial fan with high porosity and permeability because of the coarse-grained sediments of the formation [

21]. This illustrates that the zone may have high hydraulic conductance, currently this aquifer is dried up due to scarce climatic conditions in the valley [

25]. The second aquifer of the area is alluvium and is composed mainly of sand, gravel, and clay particles, having an intermediate level of porosity and permeability. The third aquifer zone is Boston Formation that mainly composed of silt and clay particles having low conductivity because of its lithology. The fourth aquifer zone exists in Chilton Limestone, although the primary porosity of this zone is low, only due to tectonic activity fractures are developed in rocks which cause the secondary porosity very high in the Formation. The depth of Chilton Limestone varies in the valley, at the north end of Quetta valley the depth of bedrock is about 1500 meters and at the south end, it is 1058 meters [

25].

Mahdi, (2010) mapped the geological and structural map of the area. The area is tectonically active under the influence of collusion between Indian and Arabian plate which is at the northern boundary of the study area.

Figure 2 shows some intra-formational faults that lie in the area. Chaman or Ghazaband Zohab fault is a north-south strike-slip fault that runs through the western boundary of Quetta Valley.

3. Materials and Methods

The present research covers two keys’ areas: first assessing site suitability for artificial recharge and second the structural parameter evaluation against the lithological parameter with high prioritization. The artificial replenishment points are delineated through analysis performed with geospatial thematic layers and remotely sensed techniques have been applied to describe the effectiveness of artificial recharge.

This is done by assessing the distribution of groundwater in the aquifer of the study area, by using data from the past decades to infer the amount of water loss in the aquifer, and by assessing the amount of recharge at suitable locations other than the area of water loss in aquifers.

United States Geological Survey (USGS) Landsat 8 (OLI) satellite data, having a medium resolution of about 30 meters, have been used for land use land cover (LULC) and lineaments extraction. For the preparation of watershed and slope thematic layers, the Global Digital Elevation Model (GDEM) of 30 meters resolution has been acquired by The Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER). Geological maps of Sibi, Quetta, Loralai, and Khuzdar produced by the U.S. Geological Survey in calibration with the geological survey of Pakistan, are used for lithological layers. The groundwater data of the observation wells obtained from the Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) Quetta was used to validate the final overlay analysis map of the inferred artificial recharge area. The detailed methodology is explained in following flow chart (

Figure 3).

3.1. Data Sets Used

Many studies have been carried out by researchers since the availability of satellite data products by Landsat 7 enhanced thematic Mapper Plus launched in 1999, however after the launch of Landsat_8 having sensor Operational Land Imager (OLI) the results are clearer with imageries of good resolution. Landsat 8 has several sensors on its platform to collect different wavelengths of electromagnetic radiations. These radiations are invisible like infrared, Ultraviolet, and Microwave. When satellite imageries are made these invisible radiations are assigned a visible colour. Landsat_8 optical land Imager has a thermal infrared sensor and it collects terrestrial dataset of moderate resolution with 16 days temporal period. Similarly, the satellite of other data set, Aster is operational since 2000. It provides high-resolution data in 14 different bands of the electromagnetic spectrum. The image resolution of ASTER GDEM data ranges from 15 meters to 90 meters but we acquired ASTER GDEM of 30-meter resolution. Data from this source is used to generate elevation maps and the attributes, which are used for further analysis. The dataset from Landsat and ASTER was acquired in the year 2018 as the most recent data. In-situ ground data of water wells (2007 to 2017) has been obtained from WAPDA to analyse the temporal changes that occurred in the study area.

The thematic layer of structural element Lineaments which is generated from DEM data has been used for the experiment. The structural influence on recharge is evaluated against the lithological influence and ground data is used for the validation of the experiment.

The acquired satellite images have digital value (DN) information in their pixels, and these images have been pre-processed before being analysed. Landsat 8 images are used with multi-spectral bands with 16-bit resolution, and its metadata (MTL) contains product information such as cloud cover, solar height, and reflectivity for each band. The radiometric rescaling factor has been used to convert the image DN value into reflectivity. This process enhanced the imagery by the top of the atmosphere (TOA) reflectance correction. QGIS Desktop version 2.18.19 was used to convert the imagery from DN to reflectance bands.

In this study, we perform pre-processing of raw data taken in the form of imagery and identify/generate different map layers using PCA and classifications. These thematic map layers are further indexed via assigning weights as a separate overlay where lithology has assigned the highest priority. These map layers along with weighted index are further used for evaluation and classification of artificial recharge sites which are further validated against ground data. And cross-tested against the lineament’s high weightage recharge by comparison of correlations of both tests with ground data. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is an image enhancement technique that processed the multiband data sets to compress the information from original bands to fewer bands. [

26] discussed that Near Infrared, Shortwave Infrared, and Middle Infrared composite provides good visual information for interpretation of what. In this study, PCA is applied to six bands 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7. However, only band one has been used in all three RGB Composite Image bands to do lineament extraction

.

QGIS 2.18.19, Rockworks, MODFLOW Flex-2005, and Microsoft Excel-2010 have been used for data preparation and its analysis. QGIS is widely used during the analysis, after corrections applied to data all the thematic layers were prepared using QGIS and their overlay as well. “Rockworks” was used to extract the alignment direction of linear structures and their density direction which is represented by the rose diagram given below. MODFLOW Flex has been used for regression analysis of ground data to create a stochastic surface based on actual data so that points of unknown values in the study area are generated from the points of known values.

3.2. Lithology

Sandstone and conglomerates are considered as a material having high absorption of water because they have large particle size and coarse texture; their pore spaces are wider than other rock material, one-fourth of the percentage has been assigned to lithology [

27].

Sandstone and conglomerates of Miocene-Pliocene age are fractured and porous, having inter-granular porosity, these are considered most suitable for water absorption. Most of the valley is covered by limestone of the middle Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Eocene ages. Limestones in the area are fractured and having secondary porosity they are also considered suitable for water intake throughout the region [

28]. Chiltan limestone of Jurassic age, Pleistocene Soan Formation, Eocene to Pliocene sandstone and Conglomerate comprises almost the whole valley, clays, sandstone, and gravels are porous and permeable and are recent deposits of Holocene age, these comprise unconfined aquifer in the region [

24].

Table 1.

Showing the average permeability of rock units in the study area.

Table 1.

Showing the average permeability of rock units in the study area.

| Lithology |

Average Permeability (m2/d). |

| Limestone |

10-18 to 10-10

|

| Sandstone and Conglomerates |

10-19 to 10-13

|

| Alluvium |

10-15 to 10-10

|

| Semi-consolidated Clasts |

to 10-10

|

Figure 4 shows the lithological map prepared according to lithological units ranking in Weighted Overlay (WOL). Lithology is mainly comprised of sand, clay, and gravels of Quaternary Alluvium scattered as Bostan Formation, alluvium, and alluvial fans. Limestone of Jurassic age is found in most of the part of Quetta valley. Dik, Taktu, Murder, and Kumbelan ranges are composed entirely of Chiltan Limestone intercalated with Cretaceous and Tertiary sediments.

3.3. Lineaments

Lineament analysis calculates its frequency per unit area. Lineaments extracted by satellite imageries are interpreted as fractures in rock formations of the area. They are also considered as the most important factor for water intake to subsurface aquifers from the ground surface, they are ranked second in the weighted overlay [

5].

Landsat 8 OLI imagery has been used for semi-automated Lineaments extraction. Imageries are enhanced by image processing techniques; After DN to Reflectance conversion and PCA of the band set 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7, the band set with the first band in place of all the three bands RGB has been used in PCI Geomatics to extract lineament features. From PCI Geomatica Algorithm menu line is used with the threshold set to 50 which is half of the total percentage of linear features exist in the imagery. Line algorithm consists of three stages curve extraction, thresholding, and edge detection [

29].

Maps produced by analysis show the concentration of linear features over an area (

Figure 5). The lineament density layer has been generated by using the lineament features layer as an input and the line density tool has been applied in QGIS to get the density thematic layer of lineaments.

Area calculation of the density map enabled us to understand the density group covered the area present of the total study area used in this study and a quick understanding of the structural deformation trends. The density area in Km

2 and the percentage is given below

Table 2.

In most of the area, lineaments are underlain by zones of confined weathering what's more, expanded penetrability and porosity. Lineament's lengths concentrations and directions are represented by a rose diagram in the figure given below.

The length of the petals (

Figure 6) represents the intensity of line concentrations and their angle represents their direction of distribution in the area. In the first diagram, we have more concentrations of lineaments however a threshold of 50 has been applied during lineaments extraction in PCI Geomatica to exclude the smaller lineaments which are considered as noise which may be of atmospheric origin or surface features like terraces depressions in landforms. The rose diagram at the right hand has been drawn with excluded values, as observed from the diagram the intensity of petals are more towards the Northwest direction and some of them run in a Westward direction. The intensity petal at a 45-degree angle has a greater length, which represents the structural fracture or fault line passing through the area, when compared to structural studies of the area two fault lines of active nature, have been inferred in the area, the Ghazaban fault, and Kalat-Chingi fault; are running in Northeast direction through the area which is the indication that other deep-running fractures might exist along the sides.

3.4. Land Use Land Cover

Land cover is of equal importance while performing weighted overlay analysis for groundwater recharge. The land cover analysis is an important parameter as it has features that spread over the land surface and highly influence the hydrological cycle in the region [

30]. Supervised classification was employed to the selected satellite imagery. The study area is mostly composed of a dry natural barren land, so spectral signature for this kind of surface rise high in ranges between 5 to 6µm. Band 5 (NIR) of LANDSAT 8 OLI is used with a combination of band 4 (Red) and 1 to get a more detailed visualization of the ground features. In a second step, sampling has been done from differentiable features in the imagery by training polygons; each polygon represents a different feature. Finally, a maximum likelihood classifier has been applied to classify imagery into differentiable classes based on training classes (

Figure 7). Land covers greatly affect infiltration and precipitation runoff, vegetation can slow down the development of runoff enabling more opportunity for it to saturate the ground [

30]. Impervious surfaces, for example, parking areas, streets, and built-ups go about as a "fast track" for precipitation drain directly into streams. Farming and the culturing of land additionally changes the penetration pattern of an area.

Water that, in common conditions, infiltrates specifically into soil currently keeps running off into streams [

31,

32].

As assessed from the land use analysis, only 0.01% of the total land cover area is occupied by surface water bodies which indicate that there is a minor amount of surface reservoir water in the study area which is not sufficient to store enough surface water from the ground and precipitation sources. A second feature observed in the outcomes is vegetation which covered most of the area of the valley floor; however, at high altitudes, the bare hard rocks that do not support any vegetation to grow, 3% of the total land-use area is vegetation cover, whereas approximately 1.9% of the valley floor is covered by build-up areas. Alluvial soil which covered the Quetta valley and surroundings derived from the parent rocks found 15.02% of the total area. The central valley is covered by sand and silty loam, while at the margins of the valley sandy loam deposits near foothills have pebbles and clasts intermixed. A great portion of the study area (79.9%) is covered by hard strata which make the most of the land use, less for recharge activity in the region (

Figure 7).

3.5. Slope and Drainage Density

The third weight % has been assigned to slope and land cover which plays an approximately equal role in the recharge mechanism in the hilly and dry, densely populated urban area (reference). Alluvium and vegetation lie at slope 0-10% with high ranking while built-up has been assigned with low ranking also lies at the low slope; slope percentage of barren feature class varies throughout the valley. The slope gradient of the terrain directly influences the infiltration rate, the higher the percentage of slope lower will be the percolation rate because it runs off rapidly from steep surfaces while gentle to low slopes are suitable for water infiltration to saturated zones [

33]. DEM is used to extract the slope, each pixel of the DEM is referenced to a datum and 30m resolution product covers the area of 30 meters by 30 meters over a terrain [

34,

35]. Slope analysis applied on the DEM and percentage was given as parameter units to calculate, classes, are then converted to percentage slope.

The slope has been reclassified to delineate the areas within the 15% of slope range and an unequal interval of 5, 10, and 15 has been assigned to the classes. Groundwater is recharged by precipitation in the region, which is percolated by the terrain surface. The great terrain changes in the Quetta valley area were identified due to structural disturbances and a geologically active zone.

Figure 8 had shown the uneven class percentage concerning the influence on water intake.

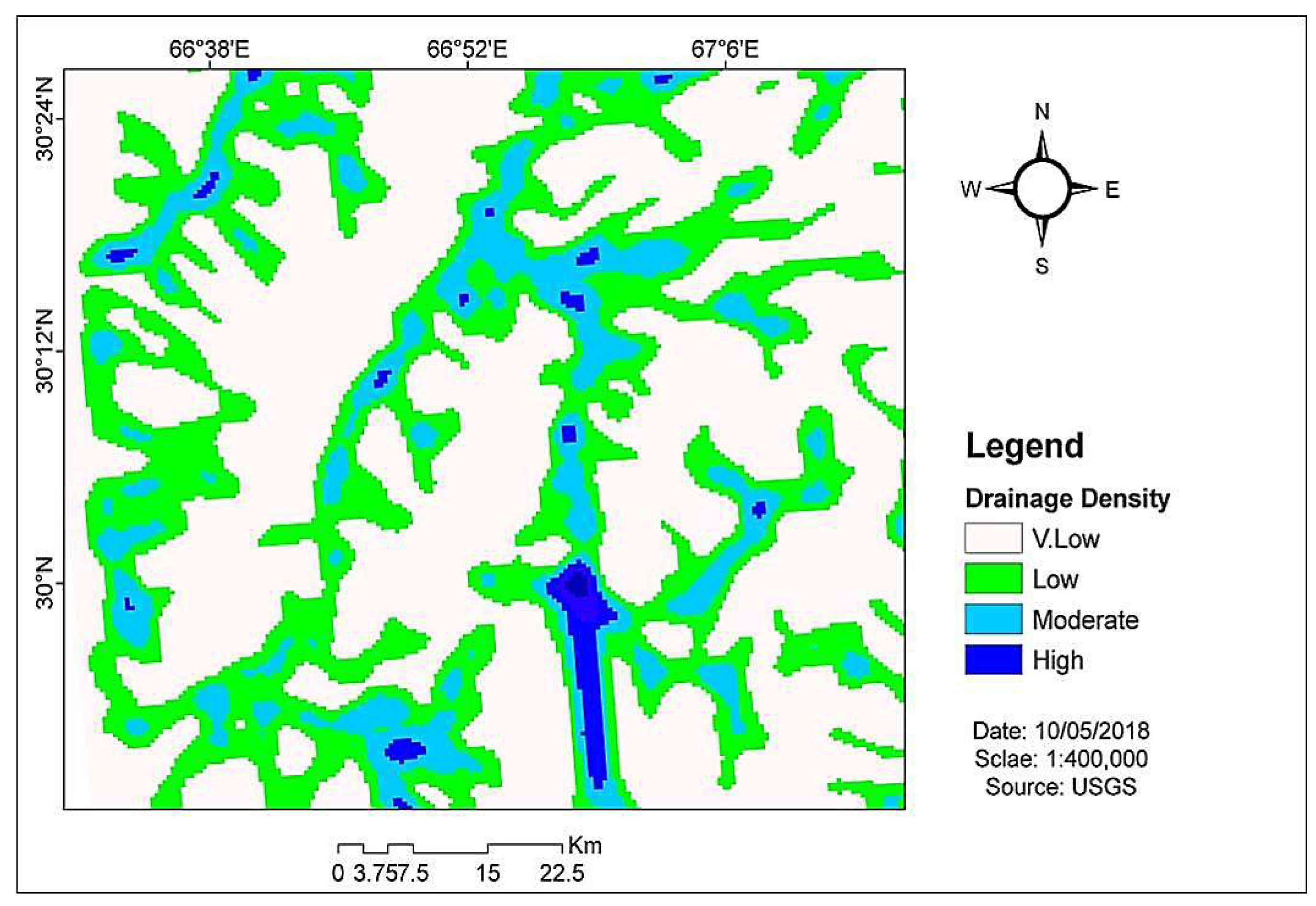

The slope map of the central valley has comparatively a low slope per km2 at each interval class. High drainage density contributes to a high recharge factor of the parameter used in the present analysis. Moderate to high drainage density cover about 15% of the total area which is approximately equal to the percentage rise adjusted to slope layer which also contributes equally in recharge as given the same ranks as drainage density.

Drainage density, bifurcation ratio, elongation ratio, and stream frequency are the key factors that influence the water runoff and absorption ratio through terrain surfaces along their channels [

36]. Drainage density is defined as the closeness of channel spacing. It is calculated by the segments of stream lengths and is controlled by the relief and slope gradient of the area [

37]. The drainage texture of the area is placed in the moderate category in the present research study and assigned a weight to it in overlay analysis according to its influence on groundwater recharge mechanism.

In QGIS, the first drainage stream lengths were calculated by field calculator, a drainage basin area was found by multiplying the number of pixels in the watershed by the area of the single-pixel such as 30×30 for 30m resolution imagery used (

Figure 9).

Watershed of an area gave us an idea of the surface water runoff in the area and the catchment area of each drainage stream flowing through the area. The watershed has been extracted using Aster DEM of 30m resolution. Hydrological tools were applied on DEM in Arc Map to extract the watershed and their respective basins, e.g. Fill Flow directions, Flow accumulation, Conditional raster, and Stream order.

The weighted overlay analysis works based on the criteria given in rankings from 1 to 10 for the information of all layer’s pixels overlaying one above another, rank 10 means most favourable conditions and one has been given to least [

38].

3.6. Reclassification and Weighted Overlay

The values of all thematic layers are automatically set to a common scale in reclassification. The Input layers having no data cells are assigned with values by the classifier and output layers with equal scale data are generated. A weighted overlay tool can be used on this data for WOL analysis.

In the WOL analyst tool weightage has been assigned to each parameter according to its active role in water intake from the surface, either rainwater or downhill running streams. Classes of every parameter have been assigned with rankings from 1 to 9, number 1 is considered as a low priority class and number 9 is at high as shown in

Table 3.

Table 3.

The parameters used in weighted overlay analysis with their percentage weights and ranking of their classes adjusted accordingly.

Table 3.

The parameters used in weighted overlay analysis with their percentage weights and ranking of their classes adjusted accordingly.

| Sr.# |

Parameters |

Classes |

Ranking |

% Weights |

| 1 |

Lithology |

Alluvium Old (Qao) |

9 |

25 |

| Alluvium Young (Qay) |

8 |

| Kirthar Formation (Tk) |

5 |

| Urak Group (Qtu) |

5 |

| Bostan Formation (Qb) |

4 |

| Ghazij Formation (Tg) |

3 |

| Mona Jhal Group (Kjm) |

2 |

| Tertiary and Cretaceous units (Tku) |

1 |

| Khojak Group (Tsm) |

1 |

| Chiltan Limestone (Jc) |

1 |

| Shirinab Formation (Js) |

1 |

| Sibbi Group (Ts) |

3 |

| Nisai Formation [39,40] |

5 |

| Dada Conglomerate (Qd) |

6 |

| 2 |

Lineaments density |

High, 60-100 % |

3 |

23 |

| Moderate 20-60 % |

2 |

| Low >20 % |

1 |

| 3 |

Slope |

0-10 |

4 |

22 |

| 11-21 |

3 |

| 22-32 |

2 |

| <33 |

1 |

| 4 |

Land cover |

Alluvium |

5 |

20 |

| Vegetation |

4 |

| Water bodies |

3 |

| Barren |

2 |

| Built up |

1 |

| 5 |

Drainage density |

High, 66-100 % |

3 |

10 |

| Moderate 33-66% |

2 |

| Low 0-33 % |

1 |

3.7. Water table Interpolation

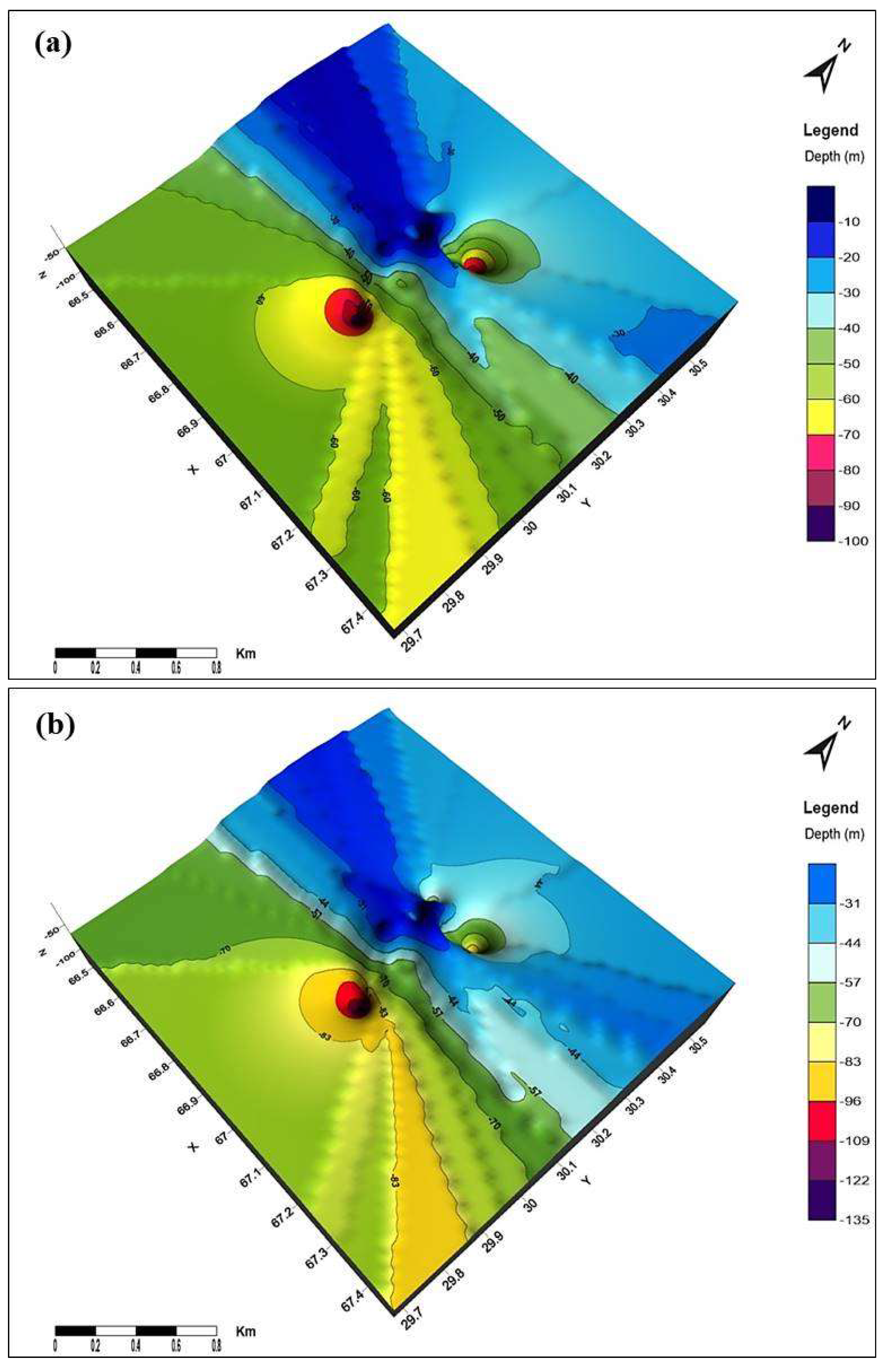

In-situ data of water wells (2000 to 2017) used to observe the trends of water table fluctuation rate in the valley (

Figure 10). To see the decadal water table depletion and fluctuations, the time series is divided into two periods. The water table depth recorded from 2000 to 2010 period shows (

Figure 10a) that the wells were up to 100 meters maximum depth and 5 meters minimum. Whereas with the advancement of time and over-exploitation by consumers, the depth of the water table depleted to 230 meters (

Figure 10b) maximum and 10 meters minimum from 2011 to 2017.

The 3D plot of the data gave an understanding of water table depth (rise or fall) depending on the time of the year. The wells data showed that the water table was depleted from -2m to -135m (

Figure 10a,b) and infers that aquifers with water table of shallow depth at the north of study area.

3.8. Evaluation

The effectiveness of the drainage or rainwater recharge to the aquifers always depends upon the nature of the aquifer which can be confined, semi-confined, unconfined, and perched aquifers [

14]. But in the present study, recharge was irrespective of the nature of the aquifer, whether it is overlain by an unconfined layer because of two reasons, first the aquifer lies in the alluvium that do not have more depth and geological succession studies of the area do not reveal whether there are unconfined layers between the aquifers instead the aquifers are hydraulically connected [

22,

23,

41]. Secondly, in the present research study lineaments have been considered the second most important parameter after lithology; they may contribute to the increased hydraulic conductivity of the aquifers from the ground surface and also increased hydraulic connectivity between the subsurface aquifers in the area.

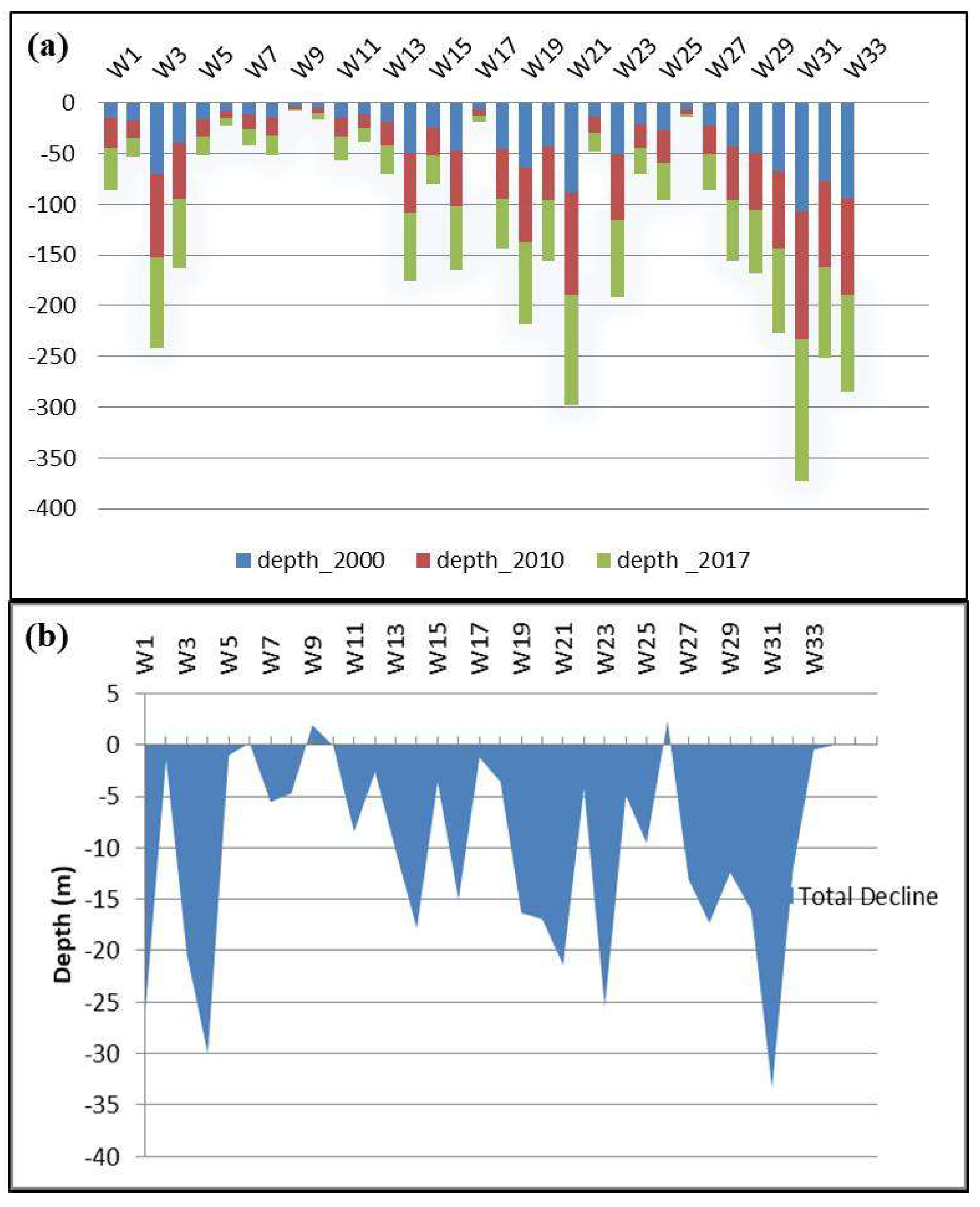

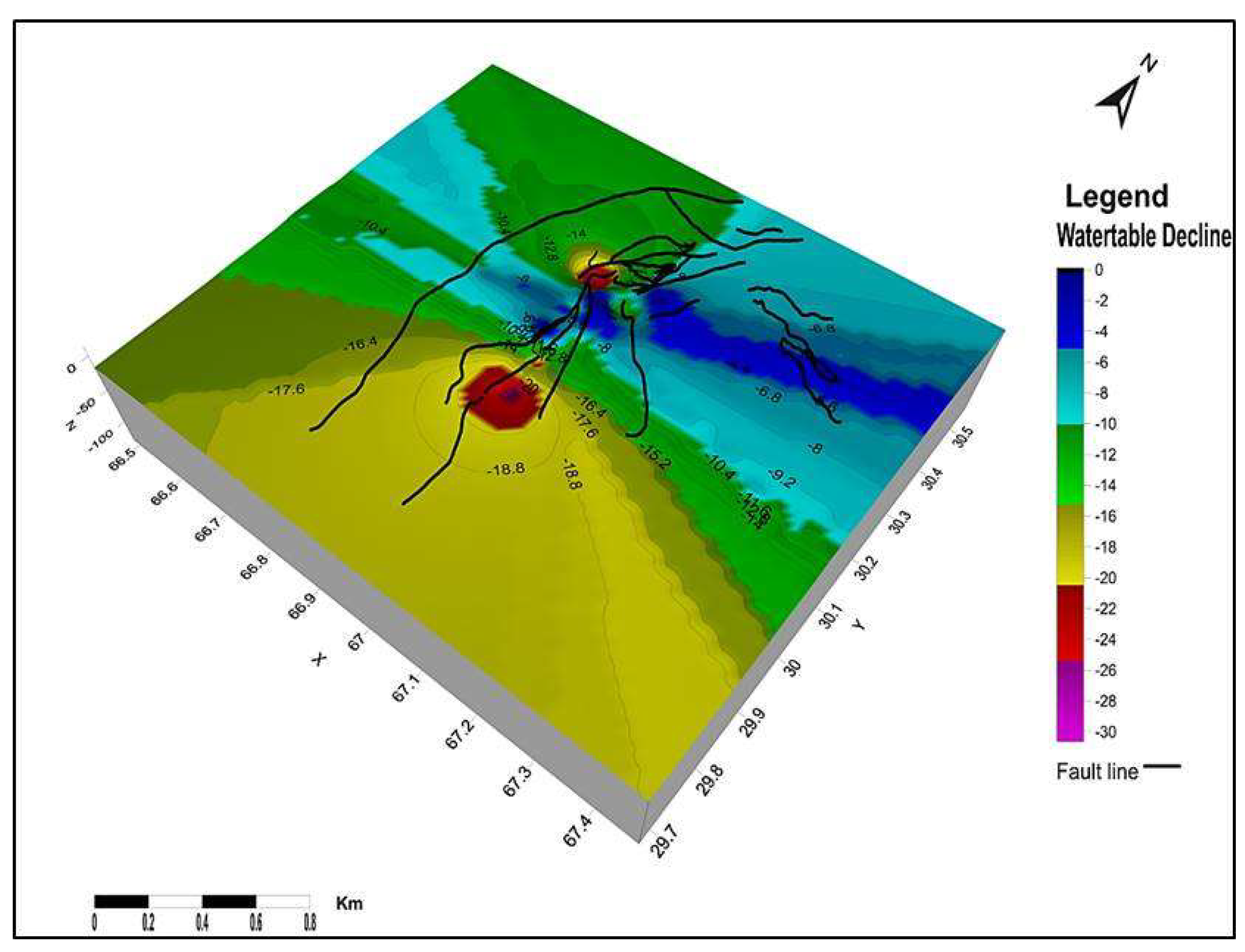

Water table decline maps were prepared using the observation wells data from 2000 to 2017 and calculated the total changes in water levels during these years (

Figure 11a and

Figure 12b).

In

Figure 12, a considerable depletion in water levels occur from 2000 onwards, at some points depletion is seen as higher as 30 meters and 35 meters in wells W3 and W31 respectively, in the central city showed this abnormal depletion can be connected to shear or fractures aquifer by fault lines at the location, however in W9 and W26 water levels increased up to several meters whereas the wells are located near natural lakes.

The effectiveness of the drainage or rainwater recharge to the aquifers always depends upon the nature of the aquifer which can be confined, semi-confined, unconfined, and perched aquifers. In this study recharge is irrespective of the nature of the aquifer whether it is overlain by an unconfined layer because of two reasons, first, the aquifer lies in the alluvium that does not have more depth and geological succession studies of the area do not reveal whether there are unconfined layers between the aquifers instead the aquifers are hydrologically connected [

23,

42,

43]. Secondly, in this research study lineaments have been considered the second most important parameter after lithology; they may contribute to the increased hydraulic conductivity of the aquifers from the ground surface and also increased hydraulic connectivity between the subsurface aquifers in the area. Correlation between purposed classes was found by using the person correlation method.

4. Results and Discussion

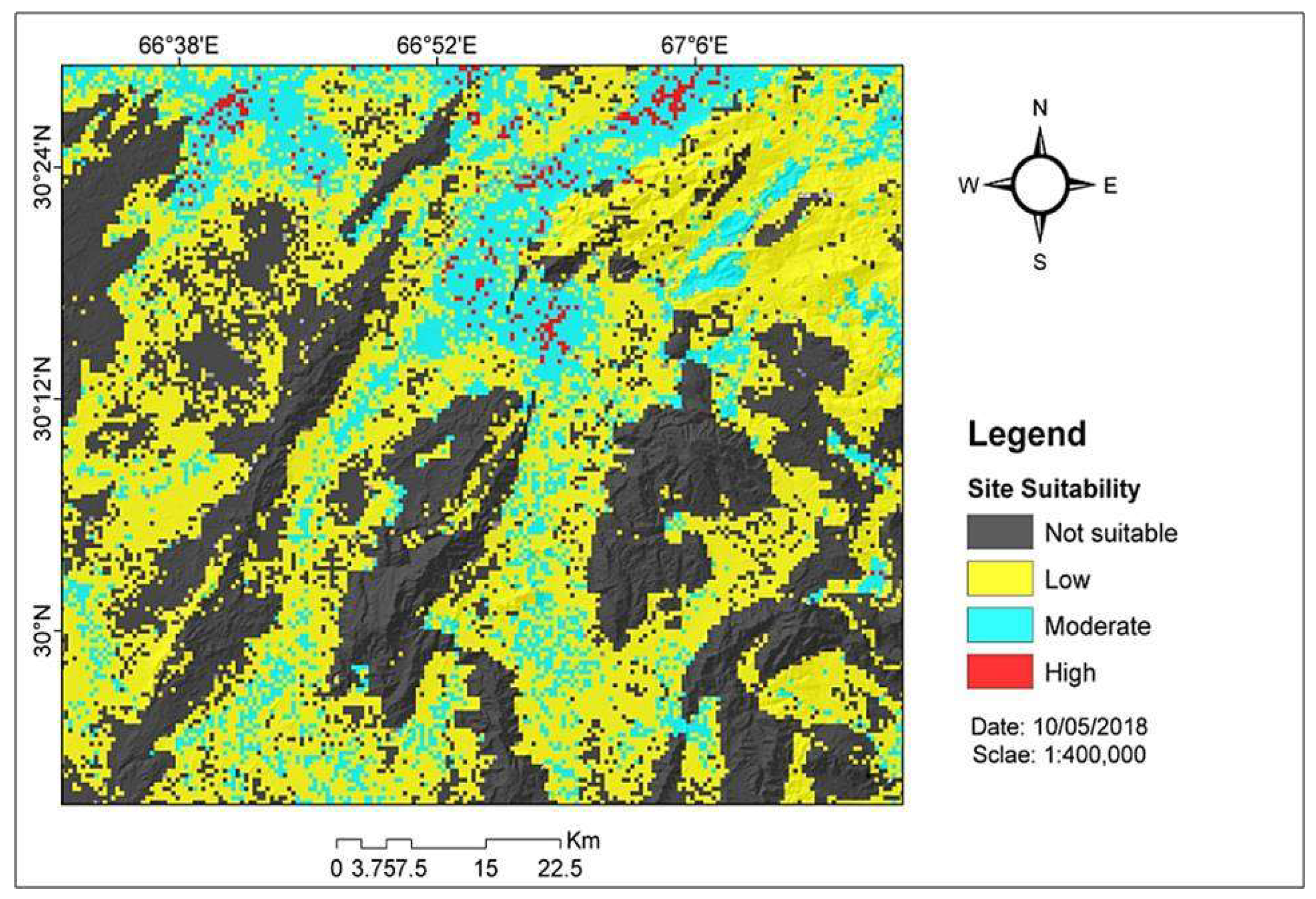

The generated layer represents pixels that meet the given criteria of logic for every layer and their respective classes according to their weighted and rankings, given in the sense of active role in recharge mechanism (

Figure 13).

NDinar, Ajram Ghar and Pishin city which are in the North and north-western part of the study area shows that these sites are of high potential recharge while most of the central part of the valley is marked moderately suitable areas. Most of the eastern and southern parts of the study area is marked with less and less suitable for potential recharge sites, areas on both sides of the valley are also marked with less and less suitable classes.

Potential recharge sites are divided into four classes by weighted overlay analysis which can be identified by red, green, blue, and grey colours (

Figure 14). Red shows high suitable sites for potential recharge, green represents the moderately suitable; blue for less suitable, and grey is for the site that is not suitable at all. Sites with high suitability mostly lies in semi consolidated deposits of sand, gravels, silt, and clays which are the primary rock units of Quaternary Alluvium having ages range from Holocene to upper Pleistocene, these rock units are coarse-grained unsorted clast having high porosity with respect to other rock units lies in the study area. Quaternary alluvium young marked as moderately suitable for a potential recharge which is of Holocene age covered most of the portion of central valley area, these alluviums composed mainly of recently deposited material over the top of older alluvium in the valley having a high proportion of clayey material which reduce the pore spaces and permeability of the unit. Areas with less and not suitable classes lie in high altitudes at both sides of the central valley, these are composed mostly of hard strata of Chiltan limestone and Bostan sand and clay stones which are compact and less porous and permeable.

Water Table Temporal Changes and Correlation

Nguyen et al, (2007) and BIPD, (2010) used data to study water levels in the valley, which is taken from Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) and Water and Sanitation Authority (WASA) results have shown an annual decline average of 36.5 million cubic meters in the area.

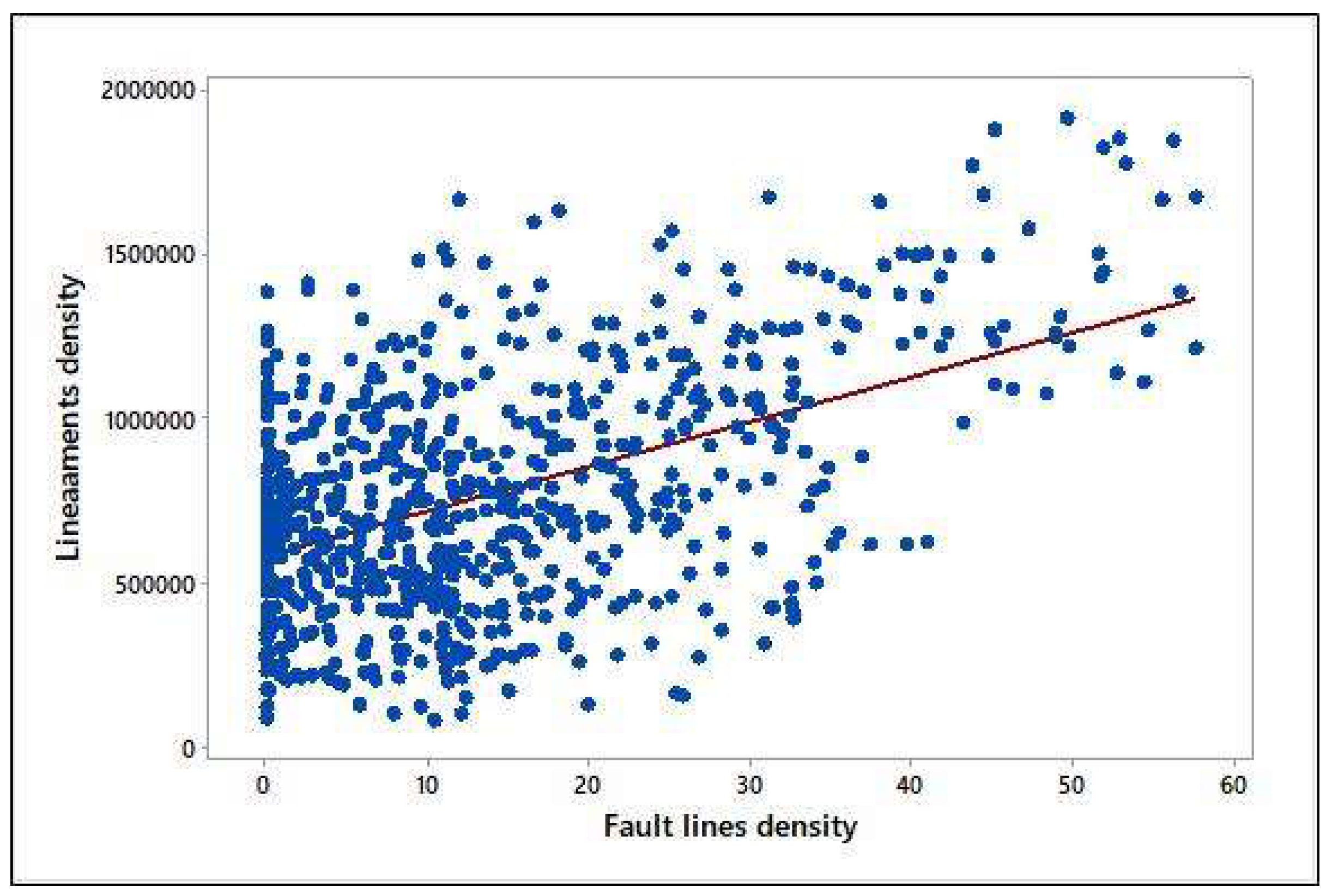

Figure 14.

Correlation plot of Lineament density and fault line density.

Figure 14.

Correlation plot of Lineament density and fault line density.

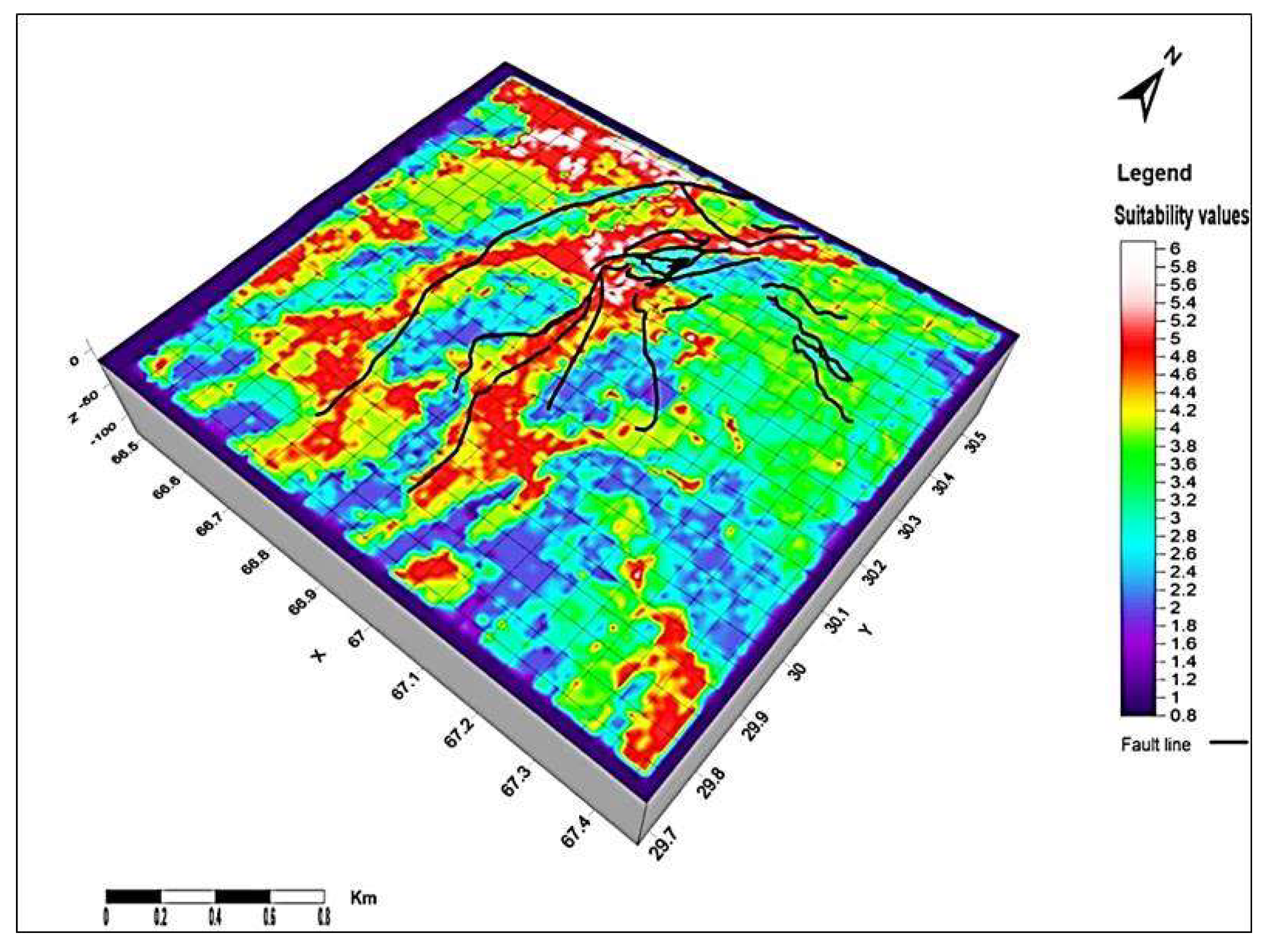

Figure 15.

The 3D overlay of potential recharge suitability site and geological structural impact.

Figure 15.

The 3D overlay of potential recharge suitability site and geological structural impact.

As water depth starts from -2m shallow to -135m high the map produced from this data infers that aquifers with water table of shallow depth are at the northern side of the observational area and another aquifer with deeper depth lies underneath it which runs approximately through the whole study area (

Figure 13). Two depressions in the northern and the southern valley region represent higher depths at these points; this can be connected to overexploitation in these areas as both are located in areas of two densely populated cities Quetta north and Mastung at the south.

[

44] proposed that water table fluctuations depend on the assumption that water level ascents are caused by precipitation recharging the aquifer. If the water level ascent is known and the specific yield is known at that point, recharge can be inferred. The research area is arid to semiarid nature and got less annual rainfalls [

45], therefore the only available source of recharge is drainage streams of the area which are delineated to be used to increase recharge efficiency. Three main streams are the surface water sources; Pishin Lora is located at the northwest of the study area, flowing in the north-south direction. The maximum recharge suitable area is located in Pishin Lora stream basin, while Surkhab Lora is the stream at the central northern boundary and Sariab Lora lays in central valley these streams also contributes but less at suitable areas.

When there are two continuous variables associated with each other, Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient is used to measure statistics of the relationship between them. It works based on covariance and gives information about the magnitude of the association between variables (Calculations are given below the correlation plot). P-Value determines the significance of the results obtained by a hypothesis (

Figure 14). The strength of the evidence is on the basis of what the outcomes tell us about the ground relates.

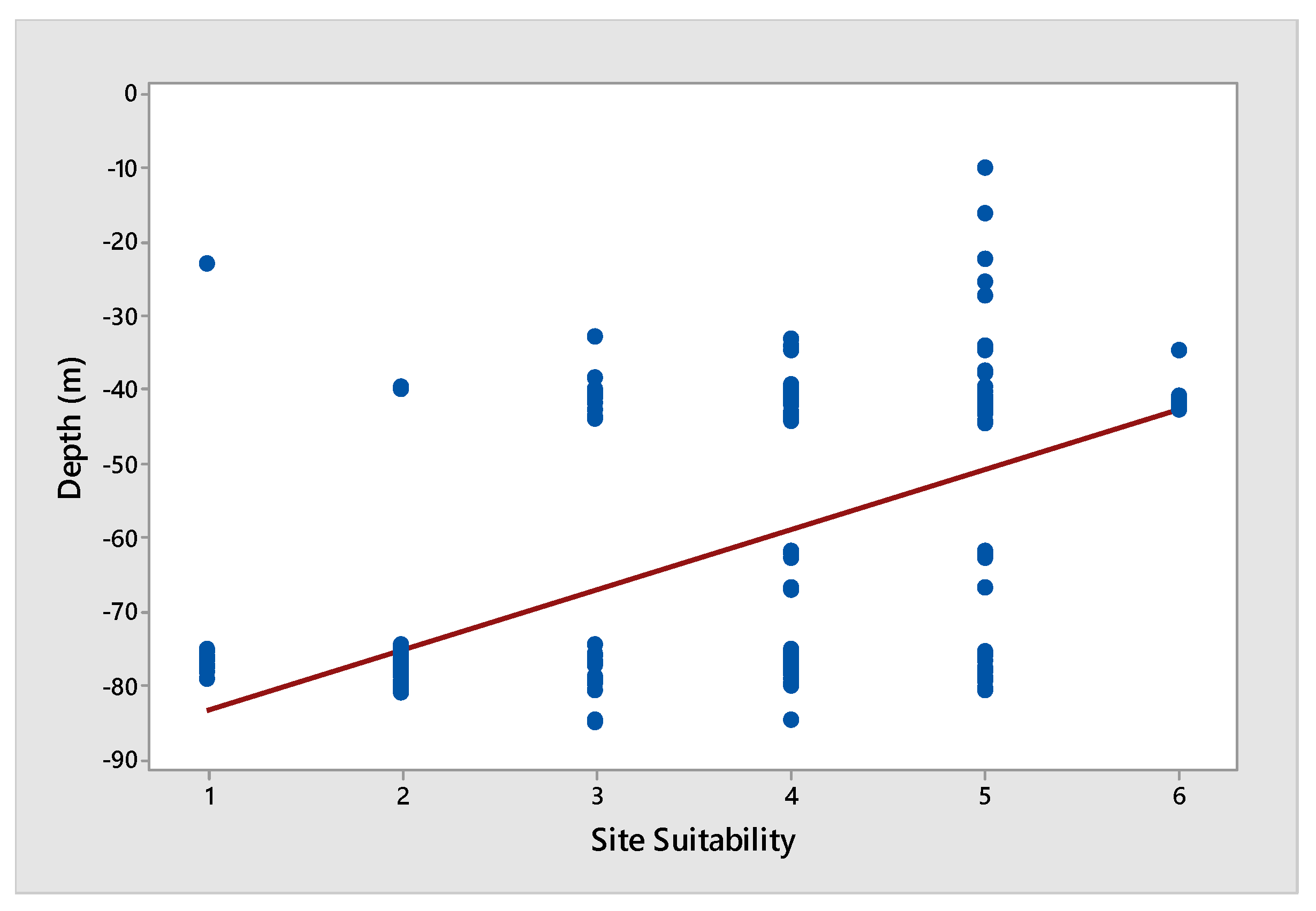

Pearson’s correlation for recharge is:

Pearson correlation of Z (Depth) and Raster (Weighted overlay output) = 0.574 & P-Value = 0.000

Figure 16.

Water table and lithology dominating site suitability regression plot.

Figure 16.

Water table and lithology dominating site suitability regression plot.

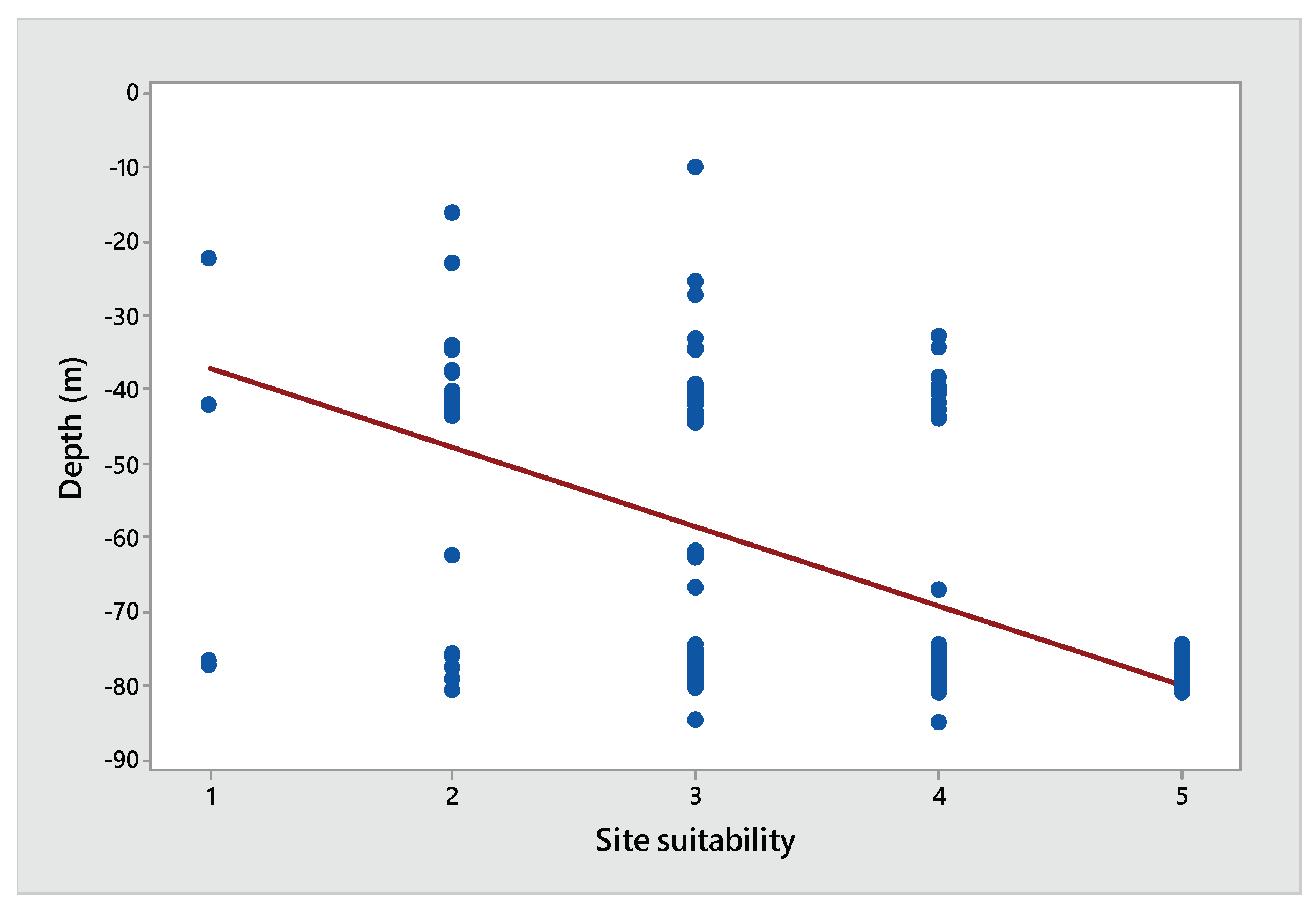

Pearson’s correlation for lineaments dominating recharge is:

Pearson correlation of Z (Depth) and Raster (Lineament _WOL) = -0.563

-Value = 0.000

Figure 17.

Water table and lineaments dominating site suitability regression plot.

Figure 17.

Water table and lineaments dominating site suitability regression plot.

The value of Pearson’s correlation shows an inverse relation between Lineament dominating recharge and water table and direct relation between Lithology dominating recharge and water table depth.

Conclusion

In the present study, Remote Sensing and GIS techniques applied for artificial groundwater recharge. Alluvium of early Quaternary period has more permeability and porosity than Holocene alluvial deposits, this is the reason these rock units allow more surface water to pass through them. Alluvium has mainstream of area’s drainage passing through it which is joined by small tributaries running down from the mountains. The water table depth and shape represent its extensive area, natural lakes in the surroundings of the upper Quetta city represent the shallow aquifer depth in the area where there is the only possible source of recharge in small areas where the suitable surface sites are intersected by stream network running through the area. Most of the streams in the area are seasonal, however; some of them are currently running on discharge of groundwater coming out upstream of the valley. Streams are not much more effective to recharge at their path of flow as pore space in the underneath rocks are already coagulated by particle deposition by flowing water, however, nearby places can be allocated at sites of high suitability for stream water spread over a landscape surface for effective recharge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B. and M.A.; methodology M.A and F.B.; resources, S.T.; data collection, F.B and S.H.; software, F.B. and M.A.; Supervision, S.T.; Validation, G.S.; Project administration, G.S.; Writing—review & editing, F.B., M.A., and S.H.; and revision of the original manuscript, M.A. and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We are happy to share with this thankful note to the Department of Meteorology, COMSATS University Islamabad, Pakistan to provide a peaceful environment and all possible support to acquire the relevant data for this study. In addition, we are thankful to USGS for their free dataset which we used to conduct this study, and thanks to the Geological Survey of Pakistan for providing the data to complete this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- M. K. Gumma and P. Pavelic, "Mapping of groundwater potential zones across Ghana using remote sensing, geographic information systems, and spatial modeling," Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, vol. 185, no. 4, pp. 3561-3579, 2013/04/01 2013.

- A. Saraf, P. Choudhary, B. Sarma, and P. Ghosh, "Impacts of reservoirs on groundwater and vegetation: A study based on remote sensing and GIS techniques," International Journal of Remote Sensing, vol. 22, no. 13, pp. 2439-2448, 2001.

- J. Dong, D. Zhuang, Y. Huang, and J. Fu, "Advances in multi-sensor data fusion: Algorithms and applications," Sensors, vol. 9, no. 10, pp. 7771-7784, 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. G. Thannoun, "Automatic Extraction and Geospatial Analysis of Lineaments and their Tectonic Significance in some areas of Northern Iraq using Remote Sensing Techniques and GIS.," INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENHANCED RESEARCH IN SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY & ENGINEERING, vol. VOL. 2, no. ISSUE 2, 2013.

- A. Shaban, F. El-Baz, and M. Khawlie, "The relation between water-wells productivity and lineaments morphometry: Selected zones from Lebanon," Hydrology Research, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 187-201, 2007. [CrossRef]

- E. Salameh, G. Abdallat, and M. van der Valk, "Planning Considerations of Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) Projects in Jordan," Water, vol. 11, no. 2, p. 182, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Das, "Delineation of groundwater potential zone in hard rock terrain in Gangajalghati block, Bankura district, India using remote sensing and GIS techniques," Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 1589-1599, 2017.

- R. Sitender, "Estimation of ground water resource of Gurgaon District," Haryana. J. Land Use Water Manag, vol. 14, pp. 25-36, 2015.

- S. K. Nag and P. Ghosh, "Delineation of groundwater potential zone in Chhatna Block, Bankura District, West Bengal, India using remote sensing and GIS techniques," Environmental Earth Sciences, vol. 70, no. 5, pp. 2115-2127, 2013/11/01 2013.

- S. Shekhar and A. C. Pandey, "Delineation of groundwater potential zone in hard rock terrain of India using remote sensing, geographical information system (GIS) and analytic hierarchy process (AHP) techniques," Geocarto International, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 402-421, 2015/04/21 2015.

- D. C. Jhariya, T. Kumar, M. Gobinath, P. Diwan, and N. Kishore, "Assessment of groundwater potential zone using remote sensing, GIS and multi criteria decision analysis techniques," Journal of the Geological Society of India, vol. 88, no. 4, pp. 481-492, 2016/10/01 2016.

- R. W. Healy and P. G. Cook, "Using groundwater levels to estimate recharge," Hydrogeology journal, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 91-109, 2002. [CrossRef]

- N. S. Rao, G. Chakradhar, and V. Srinivas, "Identification of groundwater potential zones using remote sensing techniques in and around Guntur town, Andhra Pradesh, India," Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing, vol. 29, no. 1-2, p. 69, 2001.

- S. Arya, T. Subramani, and D. Karunanidhi, "Delineation of groundwater potential zones and recommendation of artificial recharge structures for augmentation of groundwater resources in Vattamalaikarai Basin, South India," Environmental Earth Sciences, vol. 79, no. 5, p. 102, 2020/02/24 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. K. Zaidi, Y. Nazzal, I. Ahmed, M. Naeem, and M. K. Jafri, "Identification of potential artificial groundwater recharge zones in Northwestern Saudi Arabia using GIS and Boolean logic," Journal of African Earth Sciences, vol. 111, pp. 156-169, 2015/11/01/ 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. K. Singh, M. K. Jha, and V. M. Chowdary, "Multi-criteria analysis and GIS modeling for identifying prospective water harvesting and artificial recharge sites for sustainable water supply," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 142, pp. 1436-1456, 2017/01/20/ 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Pliakas, C. Petalas, I. Diamantis, and A. Kallioras, "Modeling of Groundwater Artificial Recharge by Reactivating an Old Stream Bed," Water Resources Management, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 279-294, 2005/06/01 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. Ghayoumian, B. Ghermezcheshme, S. Feiznia, and A. A. Noroozi, "Integrating GIS and DSS for identification of suitable areas for artificial recharge, case study Meimeh Basin, Isfahan, Iran," Environmental Geology, vol. 47, no. 4, pp. 493-500, 2004.

- J. O. Kimrey, "Artificial recharge of groundwater and its role in water management," Desalination, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 135-147, 1989/04/01/ 1989. [CrossRef]

- A. Ghani, Z. A. Chaudary, H. Rehman, A. H. Azhar, and M. Masood, "Assessment of Sustainable Groundwater Extraction rate for Quetta city using MODFLOW," Pakistan Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, vol. 24, 2019.

- N. Kakar, D. M. Kakar, and S. Barrech, "Land subsidence caused by groundwater exploitation in Quetta and surrounding region, Pakistan," Proc. IAHS, vol. 382, pp. 595-607, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Khan, K. Mahmood, M. I. Sultan, A. S. Khan, Y. Xiong, and Z. Sagintayev, "Trace element geochemistry of groundwater from Quetta Valley, western Pakistan," Environmental Earth Sciences, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 573-582, 2010.

- A. Kazmi, G. Abbas, and S. Younas, "Water resources and hydrogeology of Quetta Basin, Balochistan, Pakistan," Geological Survey of Pakistan, Quetta, 2005.

- A. S. Khan, S. D. Khan, and D. M. Kakar, "Land subsidence and declining water resources in Quetta Valley, Pakistan," Environmental earth sciences, vol. 70, no. 6, pp. 2719-2727, 2013. [CrossRef]

- K. Alam and N. Ahmad, "Determination of aquifer geometry through geophysical methods: A case study from Quetta Valley, Pakistan," Acta Geophysica, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 142-163, 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Serra-Sogas, P. D. O’Hara, R. Canessa, P. Keller, and R. Pelot, "Visualization of spatial patterns and temporal trends for aerial surveillance of illegal oil discharges in western Canadian marine waters," Marine pollution bulletin, vol. 56, no. 5, pp. 825-833, 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Uren, C. Laukamp, A. D. George, S. A. Occhipinti, and A. R. Aitken, "Inferring sandstone grain size using spectral datasets: An example from the Bresnahan Group, Western Australia," Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 252, p. 112109, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Hayatullah, K. Attiq-ur-Rehman, K. Samiullah, K. Naqeebullah, A. Irshad, and A. Abdul Baqi, "Physicochemical and Spectroscopic Elemental Analysis of Ground Water in Thickly Populated and Industrial Area of Quetta Valley Pakistan," Al-Nahrain Journal of Science, vol. 22, no. 3, 09/01 2019.

- M. H. Msaddek, Y. Moumni, I. Chenini, and M. Dlala, "Applicability of Developed Algorithm for Semi-automated Extraction and Morphotectonic Interpretation of Lineaments Using Remotely Sensed Data, Southwestern Tunisia," Remote Sensing in Earth Systems Sciences, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 292-307, 2019/12/01 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. R. Scanlon, R. C. Reedy, D. A. Stonestrom, D. E. Prudic, and K. F. Dennehy, "Impact of land use and land cover change on groundwater recharge and quality in the southwestern US," Global Change Biology, vol. 11, no. 10, pp. 1577-1593, 2005. [CrossRef]

- D. Lu, P. Mausel, E. Brondizio, and E. Moran, "Change detection techniques," International journal of remote sensing, vol. 25, no. 12, pp. 2365-2401, 2004.

- D. C. Rundquist, S. Narumalani, and R. M. Narayanan, "A review of wetlands remote sensing and defining new considerations," 2001. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Singh, M. Zeddies, U. Shankar, and G. A. Griffiths, "Potential groundwater recharge zones within New Zealand," Geoscience Frontiers, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 1065-1072, 2019/05/01/ 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Jha, V. Chowdary, and A. Chowdhury, "Groundwater assessment in Salboni Block, West Bengal (India) using remote sensing, geographical information system and multi-criteria decision analysis techniques," Hydrogeology journal, vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 1713-1728, 2010.

- B. Maathuis and L. Wang, "Digital elevation model based hydro-processing," Geocarto International, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 21-26, 2006.

- I. P. Senanayake, D. M. D. O. K. Dissanayake, B. B. Mayadunna, and W. L. Weerasekera, "An approach to delineate groundwater recharge potential sites in Ambalantota, Sri Lanka using GIS techniques," Geoscience Frontiers, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 115-124, 2016/01/01/ 2016.

- P. Sreedevi, K. Subrahmanyam, and S. Ahmed, "The significance of morphometric analysis for obtaining groundwater potential zones in a structurally controlled terrain," Environmental Geology, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 412-420, 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Waikar and A. P. Nilawar, "Identification of groundwater potential zone using remote sensing and GIS technique," Int J Innov Res Sci Eng Technol, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 12163-12174, 2014.

- A. Khan and B. Mian, "Groundwater development issues of Baluchistan," in Proceedings of the global water partnership seminar on regional groundwater management, 2000.

- N. Vassilas, S. Perantonis, E. Charou, T. Tsenoglou, M. Stefouli, and S. Varoufakis, "Delineation of lineaments from satellite data based on efficient neural network and pattern recognition techniques," in 2nd Hellenic Conf. on AI, SETN-2002, 2002, pp. 11-12: Citeseer.

- Z. J. S. Sagintayev, "Integrated approach for the assessment and development of groundwater resources in arid lands: Applications in the Quetta Valley, Pakistan," PhDT, 2010.

- C. TCI, "ARD, 2004," Techno Consult International Corporation, Cameous and Arab Resources Development. Research for water and sanitation authority, Quetta. Quetta water supply and environmental improvement project, vol. 2, 2008.

- Z. J. S. Sagintayev, "Integrated approach for the assessment and development of groundwater resources in arid lands: Applications in the Quetta Valley, Pakistan," 2010.

- M. A. Sophocleous, "Combining the soilwater balance and water-level fluctuation methods to estimate natural groundwater recharge: Practical aspects," Journal of hydrology, vol. 124, no. 3-4, pp. 229-241, 1991. [CrossRef]

- S. Salma, M. Shah, and S. Rehman, "Rainfall trends in different climate zones of Pakistan," Pakistan Journal of Meteorology, vol. 9, no. 17, 2012.

Figure 1.

The study area map shows the regional location of observation wells, and elevation in color pattern from low to high.

Figure 1.

The study area map shows the regional location of observation wells, and elevation in color pattern from low to high.

Figure 2.

The Fault Structure map of the study area where each type of line indicating the different fault lines.

Figure 2.

The Fault Structure map of the study area where each type of line indicating the different fault lines.

Figure 3.

The flow chart diagram of the data framework having all respective components that are used in research.

Figure 3.

The flow chart diagram of the data framework having all respective components that are used in research.

Figure 4.

The lithological map showing the lithological units. (Qay is for Quetta alluvium young, Qao-Quetta alluvium old, Qb Bostan formation, Qd- Dada Conglomerates, Qtu-Urak Group, Ts-Sibbi Formation, Tsm-Kojak Group, Tn-Nisai Formation, Tk-Kirthar Formation, Tg-Ghazij Formation, Tkg-Kirthar and Ghazij Formation, Tku-Tertiary and Cretaceous units, Kjm-Mona jhl Group, Jc-Chiltan Limestone and Js-Shirinab Formation).

Figure 4.

The lithological map showing the lithological units. (Qay is for Quetta alluvium young, Qao-Quetta alluvium old, Qb Bostan formation, Qd- Dada Conglomerates, Qtu-Urak Group, Ts-Sibbi Formation, Tsm-Kojak Group, Tn-Nisai Formation, Tk-Kirthar Formation, Tg-Ghazij Formation, Tkg-Kirthar and Ghazij Formation, Tku-Tertiary and Cretaceous units, Kjm-Mona jhl Group, Jc-Chiltan Limestone and Js-Shirinab Formation).

Figure 5.

(a) represents the lineaments map showing the lineaments by red line segments, overlaid on hill shade layer and (b) represents the lineaments density map showing the line density classes from very low to high.

Figure 5.

(a) represents the lineaments map showing the lineaments by red line segments, overlaid on hill shade layer and (b) represents the lineaments density map showing the line density classes from very low to high.

Figure 6.

Rose diagram showing the intensity and orientation of linear features, Petals represent the direction of lineaments distribution and their length shows their intensity.

Figure 6.

Rose diagram showing the intensity and orientation of linear features, Petals represent the direction of lineaments distribution and their length shows their intensity.

Figure 7.

The land use land cover map of the study area showing the surface features distribution in the area.

Figure 7.

The land use land cover map of the study area showing the surface features distribution in the area.

Figure 8.

The slope map showing the uneven percentage classes of slope surface, adjusted according to the influence on water intake.

Figure 8.

The slope map showing the uneven percentage classes of slope surface, adjusted according to the influence on water intake.

Figure 9.

The drainage density map showing the kernel density of drainage features. Drainage density has been divided into four different classes with different colour patterns.

Figure 9.

The drainage density map showing the kernel density of drainage features. Drainage density has been divided into four different classes with different colour patterns.

Figure 10.

(a) shows the 3D plot of water table depth during 1st period (2000 to 2010) and (b) shows the 3D plot of water table depth during 2nd period (2011 to 2017).

Figure 10.

(a) shows the 3D plot of water table depth during 1st period (2000 to 2010) and (b) shows the 3D plot of water table depth during 2nd period (2011 to 2017).

Figure 11.

(a) shows the temporal changes graph of water levels in observation wells and (b) shows the Water decline in the observation wells from the year 2000 to 2017.

Figure 11.

(a) shows the temporal changes graph of water levels in observation wells and (b) shows the Water decline in the observation wells from the year 2000 to 2017.

Figure 12.

The decline map overlain by fault structures.

Figure 12.

The decline map overlain by fault structures.

Figure 13.

The site suitability map showing the potential recharge sites for groundwater recharge.

Figure 13.

The site suitability map showing the potential recharge sites for groundwater recharge.

Table 2.

The lineaments density classes area and their probability to take part in water percolation.

Table 2.

The lineaments density classes area and their probability to take part in water percolation.

| Lineaments Density |

Area (Km2) |

Area % |

Class Probability |

| V. Low |

5655.271 |

51.512 |

0.515 |

| Low |

4241.636 |

38.636 |

0.386 |

| Moderate |

981.0596 |

8.936 |

0.089 |

| High |

100.4533 |

0.915 |

0.009 |

| Total |

10978.42 |

100 |

0.999 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).