1. Introduction

Timely and successful reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) and subsequent optimal medical therapy are associated with a decreased infarct size, preservation of left ventricular systolic function, and reduced mortality in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. It is well known that left ventricular systolic function is a particularly important predictor of mortality and the occurrence of other adverse events after STEMI [

6,

7] and that left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) is currently the most commonly used parameter for evaluating systolic function [

8,

9]. Patients with preserved EF after STEMI are considered to have a low risk of mortality and the occurrence of other adverse cardiac events [

2,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Heart failure (HF) complicating STEMI is another strong predictor of mortality and the occurrence of other adverse events. Patients who develop HF are considered high-risk [

5,

7,

10,

11,

15,

16]. HF complicating STEMI is predominantly caused by left ventricular systolic dysfunction (i.e., reduced EF) [

10,

17,

19,

20,

21]. On the other hand, diastolic dysfunction in STEMI patients with preserved EF may also cause HF [

9,

22,

23]. The incidence of HF complicating STEMI is on the decline in the pPCI era, but it has not been completely eliminated, and, according to some authors, it can be as high as 30% [

1,

3,

4,

9,

10,

11,

15,

17,

18,

19]. This decline in incidence refers to STEMI patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), while the incidence of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) as a complication of STEMI has remained stable [

18]. Although patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) are generally considered to have better survival than those with HFrEF, most observational studies indicate that this difference is negligible [

24]. Results from the large MAGGIC meta-analysis also showed that the adjusted median 2.5-year mortality rate was lower in patients with HFpEF compared to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [

24,

25].

Numerous studies have examined the incidence and prognosis of heart failure (HF) complicating myocardial infarction (MI) [

4,

5,

9,

10,

18]. However, some of these studies included mixed populations of STEMI and non-STEMI patients [

9], while others involved STEMI patients treated with various reperfusion strategies, such as primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI), fibrinolytic therapy, or post-thrombolysis PCI [

10]. Some registries have specifically evaluated post-AMI heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; however, some of these studies used varying cutoff values to define preserved EF, which differ from current guidelines [

26]. There are fewer studies analyzing the prevalence of HFpEF complicating STEMI in the era of primary PCI, and data on the long-term prognosis of these patients are almost non-existent.

This study aims to analyze the long-term mortality in patients with STEMI complicated by the development of HFpEF.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria, Data Collection, and Definitions

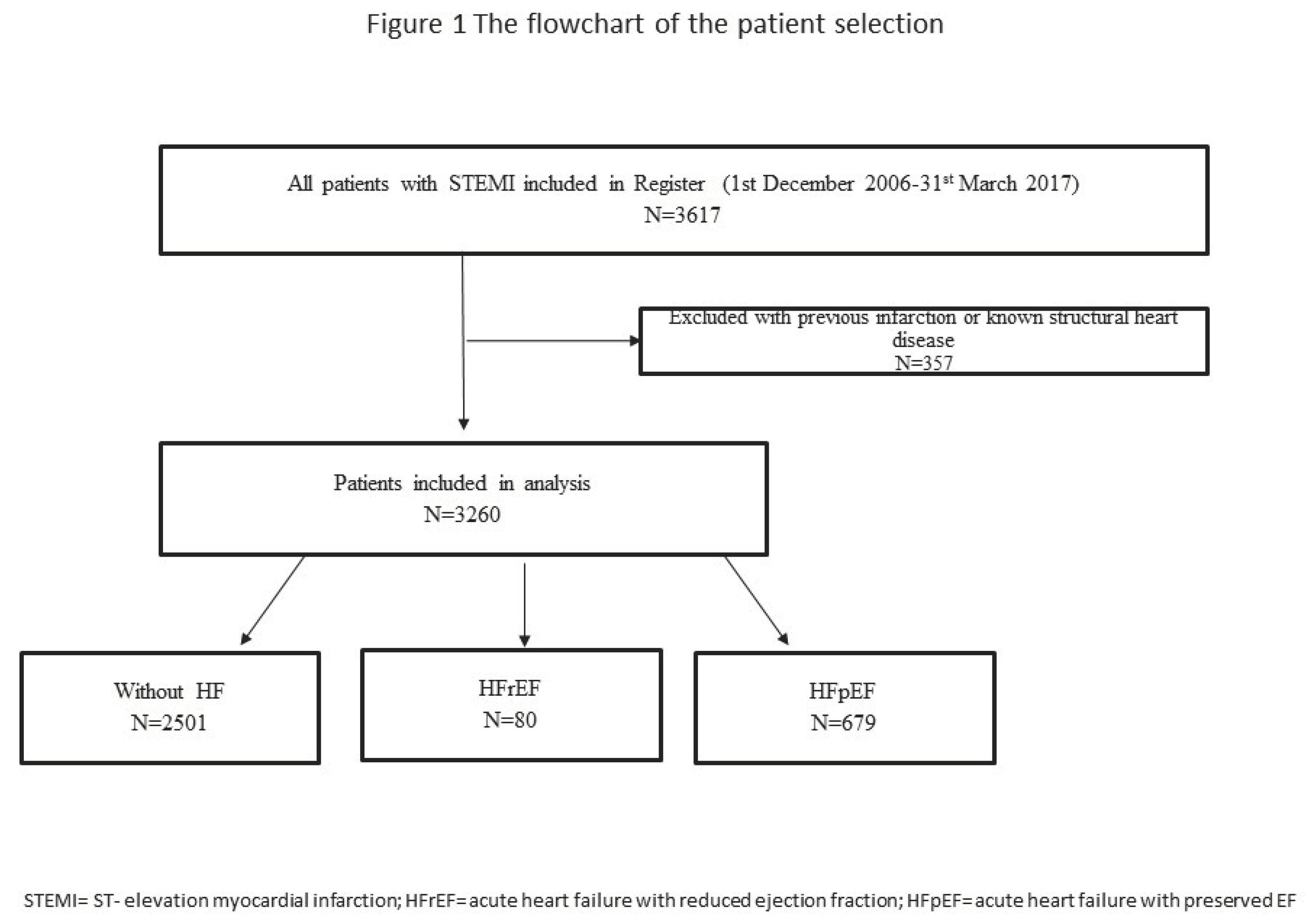

Our study involved 3,260 consecutive STEMI patients hospitalized between December 1, 2006, and March 31, 2017, who were included in the prospective University Clinical Center of Serbia STEMI Register. The purpose of the prospective University Clinical Center of Serbia STEMI Register has already been published elsewhere [

27]. The objective of the Register is to gather data on the management and short- and long-term outcomes of patients with STEMI treated with pPCI. All consecutive STEMI patients, aged 18 years or older, who were admitted to the Coronary Care Unit after being treated with pPCI in the Catheterization Lab of the Center, were included in the Register. All involved patients received written information about their participation in the Register and the long-term follow-up, and their verbal and written consent was obtained [

27]. Patients with cardiogenic shock at admission were excluded from the Register. Also, patients with previous myocardial infarction or previous known structural heart disease (according to medical records) were excluded from the study.

The flowchart of patient selection is presented in

Figure 1.

Coronary angiography, primary PCI, and stenting of the infarct-related artery (IRA) were performed using the standard technique. The femoral approach was the preferred vascular access in patients hospitalized between 2005 and 2012, while in patients hospitalized between 2013 and 2017, the radial approach was the preferred vascular access. Loading doses of aspirin (300 mg), clopidogrel (600 mg), or ticagrelor (180 mg) were administered to all patients before pPCI, depending on the guideline recommendations and practice current at the time of the index procedure. Selected patients were also given the GP IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor during the procedure. After pPCI, patients were treated according to the current guidelines.

Demographic, baseline clinical, laboratory, angiographic, and procedural data were collected and analyzed. Baseline kidney function (blood for creatinine analysis was drawn at hospital admission, before pPCI and iodine contrast administration) was assessed using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation, and the value of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 60 ml/min/m2 was considered as chronic kidney disease (CKD). Anemia at admission was defined as the baseline hemoglobin level <120 g/l in men and <110 g/l in women. New-onset atrial fibrillation (AF) was defined as electrocardiographic or monitoring evidence of a sustained (lasting at least 30 seconds) irregularly irregular rhythm (R-R intervals) with the absence of P waves in patients with no medical history of previous AF.

An echocardiographic examination was performed in all patients before hospital discharge. The left ventricular EF was assessed according to the biplane method. The value of EF ≥ 50% was considered as preserved EF. Diagnosis of HF (Killip class >1) at index hospitalization was made in patients with typical symptoms and signs of HF (clinical examination and corroboration by objective evidence of pulmonary and systemic congestion), after excluding any other diseases that can cause the above-described symptoms and signs. Patients were divided into three groups: those without HF, those with HF and reduced EF < 50% (HFrEF), and those with HF and preserved EF ≥ 50% (HFpEF).

Patients were followed up for eight years after the index event. Follow-up data were obtained through telephone interviews and at outpatient visits. We analyzed all-cause mortality.

2.2. Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Belgrade Faculty of Medicine (approval number 470/II-4, February 21, 2008). The study was conducted in keeping with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for their inclusion in the Register.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage, and continuous variables were expressed as the median (med), with 25th and 75th quartiles (IQR). Analysis for normality of data was performed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Baseline differences among groups were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test and the Man-Whitney test for continuous variables, and the Pearson χ² test for categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for constructing the probability curves for eight-year mortality, while the difference among patients with HFpEF, with HFrEF, and without HF was tested with the Log-Rank test. The Cox proportional hazard model (backward method, with p < 0.10 for entrance into the model) was used to identify univariable and multivariable predictors for the occurrence of mortality. Two-tailed P values of less than < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used the SPSS statistical software, version 19, for statistical analysis (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

3. Results

Of the 3,260 patients analyzed, 915 (28.1%) were women. The median age of all analyzed patients was 60 (52, 69) years. In-hospital HF was registered in 759 (23.2%) patients. Among the patients with in-hospital HF, 80 (10.5%) patients had HFpEF.

Compared to patients without HF, patients with HFpEF were older. They were more likely to have diabetes mellitus (DM), lower systolic blood pressure at admission, higher heart rate at admission, complete atrioventricular (AV) block, new-onset atrial fibrillation, and post-procedural TIMI flow <3 through the infarct-related artery, but they were less likely to have hyperlipidemia and to be smokers. In-hospital mortality was similar in these two groups of patients. When we compared patients with HFpEF and those with HFrEF we found that patients with HFpEF were less likely to have multivessel coronary artery disease (on initial angiogram), post-procedural flow TIMI<3 through the IRA, and baseline chronic kidney disease. Also, patients with HFpEF had a shorter hospital stay and lower in-hospital mortality when compared with patients with HFrEF. Except for a higher percentage of patients with HFrEF who were discharged with diuretic therapy and amiodarone, there was no difference in other therapy at hospital discharge among all the three analyzed groups.

Baseline characteristics, laboratory, angiographic, and procedural characteristics, in-hospital mortality, and therapy at discharge, in patients without HF, patients with in-hospital HFpEF, and patients with in-hospital HFrEF, are presented in

Table 1.

At eight-year follow-up, all-cause mortality was registered in a total of 267 (8.2%) patients. Causes of mortality were predominantly cardiovascular in all of the analyzed groups. Non-cardiovascular causes of death (such as cancer, ileus, pneumonia, and dementia) were registered in a total of 28 patients (10.8% of all deaths). After one-year follow-up, significantly higher mortality was recorded in patients with HFpEF compared to those without HF, while over the entire follow-up period, mortality in patients with HFpEF was significantly lower than in those with HFrEF.

Mortality during follow-up is presented in

Table 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing the probability of mortality during eight-year follow-up are presented in

Figure 2.

After adjustment for confounders, both HFpEF and HFrEF were independent predictors of mortality in eight-year follow-up. The negative prognostic impact of HFpEF was less pronounced than the negative prognostic impact of HFrEF. Predictors for the occurrence of eight-year mortality are presented in

Table 3.

4. Discussion

The results of our study showed that the occurrence of heart failure during index hospitalization was recorded in approximately 23% of the analyzed STEMI patients. The predominant cause of in-hospital HF was reduced left ventricular systolic function (i.e., reduced ejection fraction), while 10.5% of patients with in-hospital HF had preserved ejection fraction.

There was no significant difference in one-year mortality between patients with HFpEF and those without HF. However, after one year, patients with HFpEF had significantly higher mortality compared to those without HF, and this difference persisted throughout the follow-up period (eight years).

Additionally, during the entire follow-up period, mortality among patients with HFpEF was significantly lower than in those with HFrEF. HFpEF was an independent predictor of eight-year mortality. The negative prognostic impact of HFpEF on eight-year mortality was weaker than the impact observed in patients with HFrEF.

4.1. Patient Baseline Characteristics and the Incidence of HF

The incidence of HFpEF and HFrEF in our patients is generally in keeping with previous findings [

4,

5,

9,

18,

27]. In some earlier reports, the incidence of HF was higher or lower than in our study [

9,

11]. The differences in these findings can be explained by the varying populations of patients analyzed. In studies that included both STEMI and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients, the incidence of HF was generally lower [

5,

9]. In studies where myocardial revascularization was not performed in all patients, the incidence of HF was higher, as compared to our findings [

5,

11]. Thus, in an analysis of data from the ACTION Registry-GWTG, it was found that as many as 22% of STEMI patients with HF during index hospitalization had preserved left ventricular EF. However, in that study, only about 80% of STEMI patients were treated with primary PCI [

5].

The baseline characteristics of our patients with HFpEF are comparable with those found in the literature [

9,

12,

15,

18,

27]. Compared to patients without HF, it is commonly observed that patients with HFpEF are older and have poorer post-procedural TIMI flow through the infarct-related artery [

9,

18]. Also, when compared to patients with HFrEF, it is often found that patients with HFpEF had better coronary angiograms and a higher rate of post-procedural TIMI grade 3 flow. The age and risk factors of coronary artery disease did not differ between these two groups in our study, and this is also in keeping with some previous reports [

9].

4.2. Prognosis in STEMI Patients with HFpEF

Numerous studies have proven that heart failure developing during index hospitalization is a well-known major negative prognostic determinant in STEMI patients [

4,

12,

15]. A study by Kim et al. found that pre-discharge development of HF (at admission or during hospitalization) was associated with poorer clinical outcomes during the median follow-up of 60 months, as compared to patients without HF and those with HF developing after hospital discharge [

4].

A study by De Luca et al. found that one-year mortality was eight times higher in STEMI patients who experienced HF during index hospitalization, as compared to STEMI patients without HF [

12]. Studies analyzing STEMI patients with HFpEF have shown that short-term mortality in patients with HFpEF complicating STEMI is lower and that the negative prognostic impact of HFpEF is weaker, compared to that of HFrEF, which aligns with our findings [

5,

9,

18,

27].

In a study by Antonelli et al., the highest in-hospital mortality was observed in patients with systolic HF (EF <50%), while patients with HF and preserved EF (>50%) had lower in-hospital mortality compared to those with systolic dysfunction, but significantly higher mortality than patients without HF. Moreover, the negative, independent prognostic impact of HF with preserved EF on in-hospital mortality was lower than that of systolic HF, which is consistent with our results [

9].

Similar findings were reported in a study by Xu et al., which confirmed that patients with AMI and in-hospital HFpEF had significantly higher in-hospital mortality and more complications, as compared to patients without HF [

18].

Data from the CRUSADE study showed that NSTEMI patients with HFpEF have higher early mortality compared to patients without HF. In this study, 12% of patients had HFpEF, which is slightly higher than in our cohort. However, preserved EF was defined as EF ≥40%, meaning that, according to current guidelines, patients with moderately reduced EF (40–49%) were also included in the preserved EF group [

27]. Additionally, patients with HF and preserved systolic function (EF >40%) had approximately twofold lower in-hospital mortality compared to those with HF and reduced systolic function (EF <40%) [

27].

Unlike the previously cited studies, in our cohort, there was no difference in short-term mortality between the HFpEF group and the group without HF, but a significant difference was observed during long-term follow-up, beginning with one year after the index event.

4.3. Mechanisms of HF Development in STEMI Patients

Although coronary artery disease is considered one of the most important causes of HFrEF, recent data show that a large percentage of patients with AMI develop HFpEF [

28]. HF complicating AMI is a result of complex and unbalanced structural, hemodynamic and neurohumoral interactions [

9,

10,

17,

18,

22]. Ischemia and myocardial necrosis cause both systolic and diastolic dysfunction, because ventricular diastole is an active process that consumes oxygen [

9]. The percentage of patients with diastolic dysfunction following STEMI is around 20%-30% [

22]. Also, in the contemporary pPCI era, smaller infarct size usually does not reduce systolic function, but may lead to diastolic dysfunction [

28]. Even without extensive necrosis, stunned and hibernating myocardium also has relaxation/diastolic dysfunction, which is usually transitory and causes (transitory) in-hospital HF in patients with preserved EF [

3,

9,

18]. According to some authors, STEMI patients with preserved EF are usually less likely to receive drugs that positively affect their prognosis and possible further myocardial remodeling after STEMI (e.g., beta blockers and/or ACE inhibitors, etc.) [

28]. This finding may explain the poorer long-term prognosis of STEMI patients with HFpEF compared to STEMI patients without HF. In our study, there was no significant difference in the prescription of the said therapy at discharge among the analyzed patients. Therefore, the poorer survival of our STEMI patients with HFpEF cannot simply be attributed to the insufficient implementation of guideline-directed therapy.

4.4. Clinical Implications

Despite having a similar in-hospital outcome as patients without HF, STEMI patients with in-hospital HFpEF are at higher risk of mortality during long-term follow-up, as compared to patients without in-hospital HF. Bearing this in mind, STEMI patients with HFpEF should be considered to have an increased risk of mortality during long-term follow-up. Therefore, they require a more individualized approach, including more frequent follow-up, even beyond the first year following the index event. There should be a strong emphasis on strict control of risk factors for coronary artery disease and the development of HFpEF in general (primarily hypertension and diabetes mellitus), as well as on the prevention and management of obesity. [

24]. Also, introducing sodium glucose transporter inhibitors-2 (SGLT-2 inhibitors) in patients with in-hospital HFpEF should be considered regardless of the presence of DM [

29].

4.5. Study Limitations

This study should be viewed in the context of its limitations. The study is unicentric and observational, but it is controlled, prospective, and has included consecutive patients, limiting possible selection bias. Patients with cardiogenic shock at admission were excluded from our Register. We did not use other measures for determining systolic function, such as myocardial deformation imaging. However, numerous clinical trials have used EF to stratify patients, demonstrating its benefits in determining the outcome [Ng, Yilmaz]. Data on echocardiographic parameters used for assessing diastolic function were not available in all patients in our Register. There were no data on follow-up echocardiographic examinations to show whether there had been a certain degree of recovery or deterioration in the myocardial contractility. Natriuretic peptides were not determined in all patients in our Register. New-generation oral antidiabetic drugs, such as sodium glucose transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, were unavailable to our patients at the time of patient inclusion, which may have influenced long-term prognosis in those with HFpEF. The study was not designed to evaluate whether changing pharmacological treatment during follow-up would impact the long-term outcome in the analyzed patients.

5. Conclusion

Around a quarter of the patients with STEMI developed in-hospital HF, predominantly caused by reduced left ventricular systolic function. However, 10% of STEMI patients with in-hospital HF had preserved EF. STEMI patients with HFpEF had similar in-hospital mortality and significantly higher long-term mortality, as compared to STEMI patients without HF. Short- and long-term mortality was significantly lower in patients with HFpEF compared to patients with HFrEF. Development of in-hospital HFpEF in STEMI patients was an independent predictor for long-term mortality. However, the negative prognostic impact of HFpEF was weaker when compared to the impact of in-hospital HFrEF.

Author Contributions

LS and IM devised the study and participated in its design, acquisition of data, and coordination. LS performed statistical analysis. MA, SS, GK, RL, DM, and DS participated in the study design and helped draft the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in keeping with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Belgrade Faculty of Medicine (approval number 470/II-4, February 21, 2008).

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the physicians and nurses of the Coronary Unit and the Catheterization Laboratory who participated in the primary PCI program.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Martin J. Persistent mortality and heart failure burden of anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction following primary percutaneous coronary intervention: real-world evidence from the US Medicare Data Set. BMJ Open. 2023 Jun 21;13(6):e070210. [CrossRef]

- Emet S, Elitok A, Karaayvaz EB, Engin B, Cevik E, Tuncozgur A, et al. Predictors of left ventricle ejection fraction and early in-hospital mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Single-center data from a tertiary referral university hospital in Istanbul. SAGE Open Med. 2019 Aug 21;7:2050312119871785. [CrossRef]

- Mavungu Mbuku JM, Mukombola Kasongo A, Goube P, Miltoni L, Nkodila Natuhoyila A, M’Buyamba-Kabangu JR, et al. Factors associated with complications in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a single-center experience. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023 Sep 19;23(1):468. [CrossRef]

- Kim HY, Kim KH, Lee N, Park H, Cho JY, Yoon HJ, et al. Timing of heart failure development and clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023 Jun 30;10:1193973. [CrossRef]

- Shah RV, Holmes D, Anderson M, Wang TY, Kontos MC, Wiviott SD, et al. Risk of heart failure complication during hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction in a contemporary population: insights from the National Cardiovascular Data ACTION Registry. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5(6):693-702.

- Ng VG, Lansky AJ, Meller S, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, Peruga JZ, et al. The prognostic importance of left ventricular function in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the HORIZONS-AMI trial. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2014;3(1):67-77. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz AS, Kahraman F, Ergül E, Çetin M. Left Atrial Volume Index to Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Ratio Predicted Major Adverse Cardiovascular Event in ST-Elevated Myocardial Infarction Patients during 8 Years of Follow-up. J Cardiovasc Echogr 2021;31(4):227-33. [CrossRef]

- Lenell J, Lindahl B, Erlinge D, Jernberg T, Spaak J, Baron T. Global longitudinal strain in long-term risk prediction after acute coronary syndrome: an investigation of added prognostic value to ejection fraction. Clin Res Cardiol. 2024 Mar 25. [CrossRef]

- Antonelli L, Katz M, Bacal F, Makdisse MR, Correa AG, Pereira C, et al. Heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Arq Bras Cardiol 2015;105(2):145-50. [CrossRef]

- Liang J, Zhang Z. Predictors of in-hospital heart failure in patients with acute anterior wall ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2023;375:104-109. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton E, Desta L, Lundberg A, Alfredsson J, Christersson C, Erlinge D, et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of left ventricular systolic dysfunction or pulmonary congestion after acute myocardial infarction. ESC Heart Fail 2023;10(2):1347-57. [CrossRef]

- De Luca L, Cicala SD, D’Errigo P, Cerza F, Mureddu GF, Rosato S, et al. Impact of age, gender and heart failure on mortality trends after acute myocardial infarction in Italy. Int J Cardiol 2022;348:147-51. [CrossRef]

- Hoedemaker NP, Roolvink V, de Winter RJ, van Royen N, Fuster V, García-Ruiz JM, et al. Early intravenous beta-blockers in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A patient-pooled meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2020;9(5):469-77. [CrossRef]

- Yndigegn T, Lindahl B, Mars K, Alfredsson J, Benatar J, Brandin L, et al. REDUCE-AMI Investigators. Beta-Blockers after Myocardial Infarction and Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2024;390(15):1372-81. [CrossRef]

- Hung J, Teng TH, Finn J, Knuiman M, Briffa T, Stewart S, et al. Trends from 1996 to 2007 in incidence and mortality outcomes of heart failure after acute myocardial infarction: a population-based study of 20,812 patients with first acute myocardial infarction in Western Australia. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013 Oct 8;2(5):e000172.

- Sulo G, Igland J, Nygård O, Vollset SE, Ebbing M, Poulter N, et al. Prognostic Impact of In-Hospital and Postdischarge Heart Failure in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Nationwide Analysis Using Data From the Cardiovascular Disease in Norway (CVDNOR) Project. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017 Mar 15;6(3):e005277. [CrossRef]

- Jiang H, Fang T, Cheng Z. Mechanism of heart failure after myocardial infarction. J Int Med Res. 2023 Oct;51(10):3000605231202573.

- Xu M, Yan L, Xu J, Yang X, Jiang T. Predictors and prognosis for incident in-hospital heart failure in patients with preserved ejection fraction after first acute myocardial infarction: An observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Jun;97(24):e11093. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Liu Z, Zhu Y, Zeng J, Huang H, Yang W, et al. A diagnostic prediction model for the early detection of heart failure following primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2024;14(4):208-19.

- Cunningham JW, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, John JE, Desai AS, Lewis EF, et al. Myocardial Infarction in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Pooled Analysis of 3 Clinical Trials. JACC Heart Fail 2020;8(8):618-26.

- Bayes-Genis A, García C, de Antonio M, Fernandez-Nofrerías E, Domingo M, Zamora E, et al. Impact of a ‘stent for life’ initiative on post-ST elevation myocardial infarction heart failure: a 15 year heart failure clinic experience. ESC Heart Fail 2018;5(1):101-5. [CrossRef]

- Tomoaia R, Beyer RS, Simu G, Serban AM, Pop D. Understanding the role of echocardiography in remodeling after acute myocardial infarction and development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Med Ultrason 2019;21(1):69-76. [CrossRef]

- Lenselink C, Ricken KWLM, Groot HE, de Bruijne TJ, Hendriks T, van der Harst P, et al. Incidence and predictors of heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction after ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the contemporary era of early percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur J Heart Fail 2024;26(5):1142-9. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;42(36):3599-726. [CrossRef]

- Pocock SJ, Ariti CA, McMurray JJ, Maggioni A, Køber L, Squire IB, et al. Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure. Predicting survival in heart failure: a risk score based on 39 372 patients from 30 studies. Eur Heart J 2013;34(19):1404-13. [CrossRef]

- Bennett KM, Hernandez AF, Chen AY, Mulgund J, Newby LK, Rumsfeld JS, et al. Heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function among patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol 2007;99(10):1351-6. [CrossRef]

- Mrdovic I., Savic L., Lasica R. Krljanac G, Asanin M, Brdar N, et al. Efficacy and safety of tirofiban-supported primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients pretreated with 600 mg clopidogrel: results of propensity analysis using the clinical center of serbia STEMI register. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2014;3:56–66. [CrossRef]

- Kamon D, Sugawara Y, Soeda T, Okamura A, Nakada Y, Hashimoto Y, et al. Predominant subtype of heart failure after acute myocardial infarction is heart failure with non-reduced ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail 2021;(1):317-325. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(37):3627-39.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical, laboratory, angiographic, procedural characteristics, therapy at discharge and intrahospital mortality of the study patients.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical, laboratory, angiographic, procedural characteristics, therapy at discharge and intrahospital mortality of the study patients.

| Characteristics |

Without HF

N=2501 |

HFpEF

N= 80 |

P*value |

HFrEF

N=679 |

P**value

|

| Age, years med(IQR) |

58(45, 75) |

65(45, 85) |

<0.001 |

64(46, 82) |

0.828 |

| Female, n(%) |

667(26.6) |

22(27.5) |

0.453 |

226(33.2) |

0.064 |

| BMI, med (IQR) |

26.3(22.1, 30.5) |

25.5(20.1, 31.5) |

0.967 |

26.8(21.8, 31.2) |

0.897 |

| Previous angina, n(%) |

174(7) |

8(10) |

0.173 |

57(8.5) |

0.436 |

| Previous stroke, n(%) |

79(3.2) |

4(5) |

0.254 |

45(6.6) |

0.234 |

| Diabetes, n(%) |

427(17.1) |

19(23.7) |

0.038 |

203(29.8) |

0.535 |

| Hypertension, n(%) |

1652(66.1) |

51(63.8) |

0.730 |

488(71.8) |

0.335 |

| HLP, n(%) |

1555(62.2) |

32(40) |

0.003 |

380(55.9) |

0.064 |

| Smoking, n(%) |

1432(57.3) |

30(37.5) |

0.012 |

279(41) |

0.792 |

| Family hystory, n(%) |

874(34.5) |

24(30) |

0.951 |

182(26.8) |

0.238 |

| Pain duration, hours, med(IQR) |

2.5(2, 3.5) |

2.5(1.5, 3.5) |

0.678 |

3(1.5, 4.5) |

0.444 |

| New-onset atrial fibrillation, n(%) |

104(4.2) |

8(9.7) |

0.021 |

114(16.7) |

0.121 |

| Complete AV block, n(%) |

85(3.4) |

7(8.7) |

0.004 |

54(7.9) |

0.808 |

| Systolic BP at admission, med(IQR) |

140(110, 150) |

120(110, 150) |

0.022 |

130(110, 155) |

0.975 |

| Heart rate at admission med(IQR) |

76(70, 85) |

100(80, 116) |

<0.001 |

90(70, 98) |

0.063 |

| Multivessel disease, n(%) |

1323(52.3) |

46(56.9) |

0.480 |

471(69.3) |

0.031 |

| LM stenosis, n(%) |

134(5.4) |

5(6.2) |

0.553 |

57(8.4) |

0.502 |

| Stent implanted, n(%) |

2384(95.3) |

71(88.9) |

0.013 |

603(88.9) |

0.989 |

| Postprocedural flow TIMI <3, n(%) |

55(2.2) |

5(6.2) |

0.008 |

86(12.7) |

<0.001 |

| Acute stent thrombosis, n(%) |

26(1.1) |

1(1.2) |

0.336 |

11(1.6) |

0.883 |

| CK MB max, med (IQR) |

1673(1430, 5435) |

2819(1645, 4578) |

0.096 |

2883(1435, 6789) |

0.009 |

| Troponin max, med (IQR) |

29(14.3, 105) |

40(30, 130,1) |

0.456 |

52.8(34.6, 159) |

0.051 |

| WBC at admission, med(IQR) |

11.1(6.8-15.2) |

12.1(7.7-16.4) |

0.081 |

12.3(7-16.2) |

0.549 |

| Hemoglobin at admission g/L, med (IQR) |

143(123, 163) |

142(126, 156) |

0.061 |

139(117, 152) |

0.678 |

| Baseline CKD, n(%) |

1711(68.4) |

52(65.2) |

0.108 |

517(76.1) |

0.074 |

| EF, med(IQR) |

50(40, 61) |

55(50, 60) |

0.070 |

40(30, 45) |

<0.001 |

| LVEDD, med (IQR) |

5.5(5.1, 5.8) |

5.5(5, 5.7) |

0.130 |

5.7(5.3, 6.7) |

0.018 |

| Therapy at discharge*** |

|

|

|

|

|

| Beta blockers, n(%) |

2222(88.9) |

65(81.2) |

0.181 |

481(70.8) |

0.178 |

| ACE inhibitors, n(%) |

2056(82.2) |

62(77.5) |

0.204 |

462(68) |

0.417 |

| Statin, n(%) |

2206(88.2) |

66(82.5) |

0.559 |

481(70.9) |

0.447 |

| Diuretic, n(%) |

259(10.3) |

4(5) |

<0.001 |

236(34.8) |

<0.001 |

| Calcium antagonist, n(%) |

88(3.5) |

4(5) |

0.404 |

15(2.2) |

0.184 |

| Amiodarone, n(%) |

64(2.6) |

1(1.2) |

0.074 |

25(3.7) |

0.065 |

| Length of hospital stay, days, med(IQR) |

7(5, 9) |

7(6, 9) |

0.830 |

9(7, 13) |

<0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality, n(%) |

12(0.5) |

1(1.2) |

0.282 |

119(17.5) |

<0.001 |

Table 2.

Mortality during follow-up in patients without HF, patients with HFpEF and patients with HFrEF.

Table 2.

Mortality during follow-up in patients without HF, patients with HFpEF and patients with HFrEF.

| |

Without HF

N=2501 |

HFpEF

N=80 |

p value* |

HFrEF

N=679 |

p value ** |

| 1 month mortality |

19(0.7) |

1(1.1) |

0.282 |

124(18.2) |

<0.001 |

| 1-year mortality |

53(2.1) |

4(5) |

0.016 |

150(22.1) |

<0.001 |

| 8-years mortality |

87(3.5) |

9(11.2) |

<0.001 |

171(25.1) |

<0.001 |

Table 3.

Independent predictors for 8-years mortality (Cox regression model) in all analyzed patients.

Table 3.

Independent predictors for 8-years mortality (Cox regression model) in all analyzed patients.

| |

Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

| HR (95%CI) |

p value |

HR (95%CI) |

p value |

| |

| Age, years |

1.07(1.06-1.08) |

<0.001 |

1.05(1.04-1.06) |

<0.001 |

| In-hospital HF |

8.03(5.78-11.95) |

<0.001 |

4.78(3.21-7.12) |

<0.001 |

| HFrEF |

7.85(6.05-10.18) |

<0.001 |

4.89(3.19-6.42) |

<0.001 |

| HFpEF |

2.43(1.06-5.57) |

0.013 |

1.85(1.26-4.25) |

0.012 |

| Post-procedural flow TIMI<3 |

6.47(4.79-8.75) |

<0.001 |

2.84(2.06-3.92) |

<0.001 |

| New-onset AF |

4.39(3.28-5.87) |

<0.001 |

1.47(1.07-2.01) |

0.017 |

| Мultivessel disease |

2.58(2.02-3.95) |

<0.001 |

1.39(1.07-1.80) |

0.014 |

| Anaemia at admission |

2.17(1,95-3.74) |

<0.001 |

|

|

| Diabetes |

2.11(1.62-2.73) |

<0.001 |

|

|

| Baseline CKD |

1.46(1.11-1.67) |

0.051 |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).