Submitted:

09 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Motivation

- First we extract the Java implementation of ConcurrentLinkedQueue from the OpenJDK.

- We change the object-oriented code to structured code to simplify translation to CSP.

- We decompose complex operations to further simplify translation to CSP.

- Finally, we translate the code to CSP.

1.1. Layout of the Paper

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Communicating Sequential Processes

2.1.1. Choice

2.1.2. Pre-Guards

2.1.3. Process Composition

- The generalised parallel defines two processes that synchronise on a specific synchronisation setA. In (a machine-readable version of CSP) this is written as .

- The alphabetised parallel defines two processes, each restricted to their respective alphabets: P with alphabet A and Q with alphabet B. In this is written as .

2.1.4. Traces and Hiding

2.1.5. Models

The Traces Model

The Stable Failures Model

The Failures-Divergences Model

2.1.6. FDR

2.1.7. Modules

2.2. Concurrent and Non-Blocking Data Structures

- Obstruction-Free: A thread will progress if all other threads are suspended. This differs from using locks as when a thread holding a lock gets suspended, a thread waiting for the lock can continue.

- Lock-Free: A data structure is lock-free if at least one thread can continue execution at any time. This differs from obstruction-freedom in that at least one thread remains non-starving, regardless of suspension.

- Wait-Free: A data structure is wait-free if it is lock-free and ensures that every thread will make progress after a finite number of steps.

2.3. Serializable vs. Linearizable

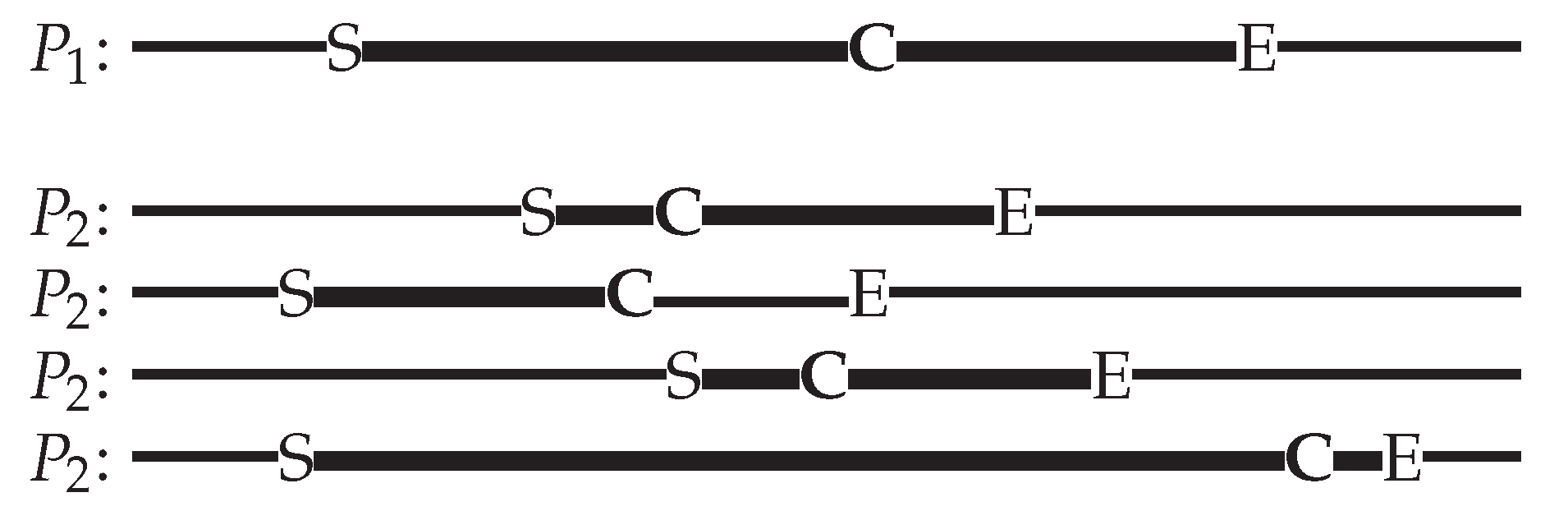

-

Linearizable traces:

- −

- — P completes before Q begins, and Q sees the value of the register as 1.

- −

- — opposite ordering, and so Q sees the value of the register as 0.

- −

- — although P has not completed, it has begun and the linearization point has occurred, thus Q sees the value of the register as 1.

-

Non-linearizable traces:

- −

- — P completes before Q begins, but Q sees the value of the register as 0. This is not linearizable as it violates the real-time ordering.

2.4. Related Work

3. Methods

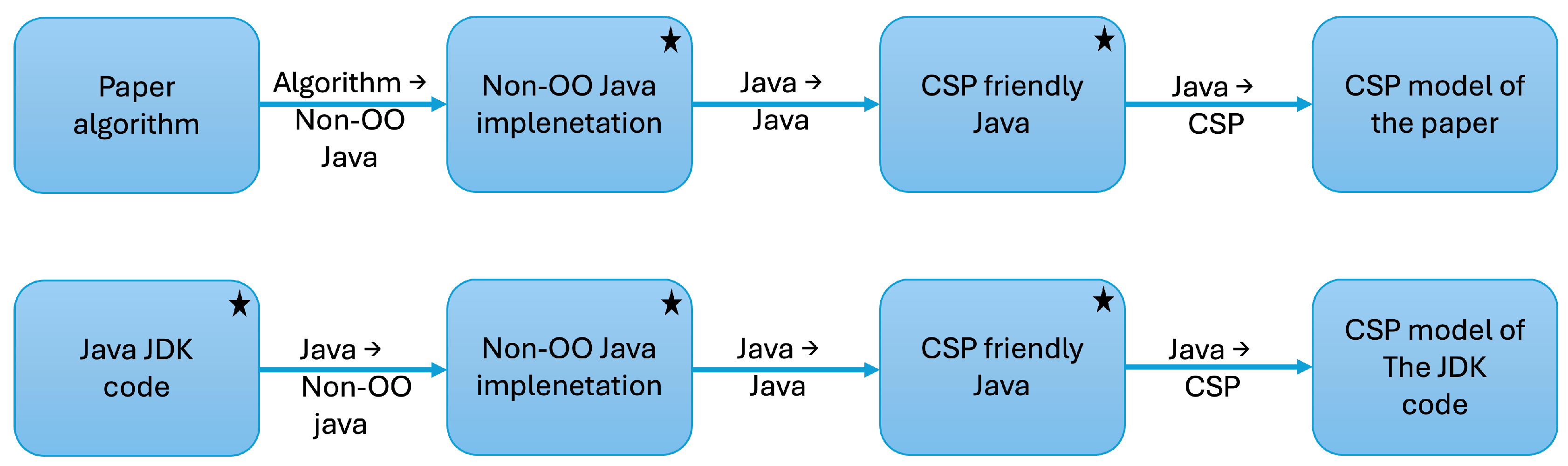

3.1. OO to CSP Pipeline

3.1.1. Common Code

- value: An AtomicInteger for the value stored on the node. The value can be null.

- next: An AtomicReference<Node> to the next node in the queue. The node can be null.

- head: An AtomicReference<Node> pointed to the head node of the queue.

- tail: An AtomicReference<Node> pointed to the tail node of the queue.

3.1.2. Converting Michael and Scott to Structured Java

| Michael & Scott | Structured Java |

| node = new_node() | Node node = new Node(); |

| node→value = value | node.value.set(value); |

| node→next.ptr = null | node.next.set(null); |

3.1.3. Converting OpenJDK Code to Structured Java

- offer() becomes enqueue().

- poll becomes dequeue().

- Ternary Operators: In the offer() method, OpenJDK uses ternary operators to update values. For example, p = (t != (t = tail)) ? t : head;. CSP does not support such operations, so we expand them into a sequence of operations to aid later conversion.

- Use of VarHandle: Rather than use Java’s atomic types directly, OpenJDK uses VarHandles to nodes and values as an optimisation. A VarHandle has atomic operators (e.g., compareAndSet). We convert this approach to use the standard Java AtomicReference and AtomicInteger types.

3.1.4. Converting Structured Java to CSP Friendly Java

- Remove method chaining.

- Store return values before use.

- Expand conditionals fully.

- Move final operations outside loops.

- Flag loop continues.

3.2. Implementing Shared Memory Programs in

3.2.1. Modelling Global State in CSP

3.2.2. Modelling Atomic Variables in CSP

3.2.3. Converting CSP Friendly Java to

3.3. Queue Specifications

3.3.1. A Sequential Queue Specification

3.3.2. A Concurrent Queue Specification

- enqueue.proc.value — the start of an enqueue operation.

- lin_enqueue.proc.value — the time of commitment — the linearization point — where the value is committed into the queue.

- end_enqueue.proc — the end of an enqueuing operation.

- What happens if the queue is full? In reality this never happens as a linked list can grow until we run out of memory, but we must manage the system state size for verification, so we set an upper limit (MAX_QUEUE_LENGTH) and only allow lin_enqueue events to happen if there is room in the queue.

- What happens if the queue is empty on dequeue? In this case, we return null.

4. Examining OpenJDK’s Implementation of a Current Queue

- add/offer — Inserts an element into queue.

- poll — Retrieves and removes an element from the queue, or returns null if this queue is empty.

- Translate the OpenJDK Java implementation to CSP (this is the implementation).

- Use the CSP model of Michael and Scott’s algorithm (this is the specification).

- Verify that the OpenJDK implementation behaves in accordance with the specification.

4.1. The OpenJDK/Java Version in CSP

4.2. Results

4.3. Code Refactoring

5. Not Sequential but Linearizable

6. Overall Results

| (1) | SeqQueue | MSYSTEM | (for N = 1 and vice versa) |

| (2) | SeqQueue | JSYSTEM | (for N = 1 and vice versa) |

| (3) | MSYSTEM | SeqQueue | (for 2 ≤ N ≤ 4 ) |

| (4) | JSYSTEM | SeqQueue | (for 2 ≤ N ≤ 4 ) |

| (5) | MSYSTEM | JSYSTEM | (for 1 ≤ N ≤ 3 and vice versa) |

| (6) | ConcQueue | MSYSTEM | (for 1 ≤ N ≤ 4 and vice versa) |

| (7) | ConcQueue | MSYSTEMJSYSTEM | (for 1 ≤ N ≤ 3 and vice versa) |

| (8) | SimpleQueue | ConcQueue | (for 1 ≤ N ≤ 4 — linearizable) |

- Show that the algorithm of Michael and Scott [1] behaves like a concurrent queue.

- Show that the OpenJDK implementation of the ConcurrentLinkedQueue behaves like Michael and Scott’s algorithm and transitively is a correct implementation of a concurrent queue.

- Does the concurrent queue specification refine the sequential queue specification? For a single user, the answer is “yes, in the stable-failures model.” For more users, the answer is “no, not even in the traces model.”

- Does the sequential queue specification refine the concurrent queue specification? For a single user, the answer is again “yes, in the stable-failures model.” For more users, the answer is “yes, but only in the traces model.” This is because the sequential queue has a different set of failures compared to the concurrent queue; This is because the number of operations in progress in a sequential queue at any time is at most one, whereas in a concurrent queue many operations can be in progress at the same time.

- The first two results show that the concurrent queue implementations behave like a sequential queue when only one user thread is using them. The third and fourth result demonstrate that the concurrent queues are not sequential with more than one thread, but the concurrent queues still contain the complete behaviour of the sequential queue.

- The fifth result demonstrate that the OpenJDK implementation of a concurrent queue behaves as Michael and Scotts original algorithm (and vice-versa). The sixth result demonstrates that Michael and Scott’s algorithm also behaves as our ConcQueue specification, leading to the seventh result through the transitive relationship of CSP refinement. This meets the key aim of our work — development of a specification of a concurrent queue that can be used in other models.

- The final result demonstrates that the concurrent queue specification and (and therefore the implementations) are linearizable, insofar that they behave as a queue that atomically allows adding and removing items. We only require trace refinement in this regard.

6.1. Limitations

- We have only checked MSYSTEM JSYSTEM to three user processes. However, this is inline with other works using CSP for verification (e.g., Lowe [2]) of such complex models. Three user processes still provides a rich set of interactions with the queue.

- We have only checked ConcQueue MSYSTEM for four user processes. Likewise, this provides a rich set of comparative behaviours to check against.

- We do not utilise any node recycling, allowing only a fixed number of enqueues to occur. Lowe [2] implemented a garbage collection system that we could have emulated (at the cost of increased state space complexity), but our work has focused on specification development. The queue allows multiple enqueues from different threads to occur, and unlimited dequeues. Again, this provides a rich set of behaviour transactions to explore for model checking.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

7.1. Conclusion

7.1.1. Contributions

7.2. Future Work

- Model Scaling via Composition Techniques. While we have verified up to four concurrent users, the state space grows exponentially. Future work could explore compositional verification or data independence techniques to verify a greater number of users, following work by Roscoe and others.

- Node Recycling and Garbage Collection Semantics. Out models assume a fixed number of enqueues and do not recycle nodes. Incorporating garbage collection (e.g., as Lowe [2]) and node deletion schemes would enable a more accurate modelling of real-world behaviour. The limitation is in the size of models that would be created.

- Application to Other Lock-Free Structures. The methodology and reusable specification style developed here could be applied to stacks, dequeues, priority queues, and concurrent maps. These structures present unique challenges in terms of linearization point placement and memory consistency.

- Exploration of Other Memory Semantics. We have assumed that atomic operations occur in the order they invoked (they are sequentially consistent). In modern memory systems, caching means we can consider different memory semantics (e.g., relaxed vs. sequentially consistent). Building a richer set of atomic memory components would allow exploration of these different semantics.

- Tool Integration and Usability. While our models are available online, integrating our workflow into tools could broaden adoption of verification of Java (or other language) code. Semi-automated translation from structured Java to could support teaching or wider industry adoption.

- Durable Linearizability. Future work could also investigate durable linearizability — i.e., ensuring consistency after a failure — building on the work of Derrick et al. [14]. This is particularly relevant for persistent memory systems.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Michael, M.M.; Scott, M.L. Simple, fast, and practical non-blocking and blocking concurrent queue algorithms. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing, New York, NY, USA, 1996; PODC ’96, p. 267–275. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, G. Analysing Lock-Free Linearizable Datatypes Using CSP. In Concurrency, Security and Puzzles: Essays Dedicated to Andrew William Roscoe on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday; Gibson-Robinson, T.; Hopcroft, P.; Lazić, R., Eds.; Springer, 2017; Vol. 10160, LNCS. LNCS. [CrossRef]

- Hoare, C.A.R. Communicating Sequential Processes. CACM 1978, 21, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, C.A.R. Communicating Sequential Processes; Prentice-Hall, 1985.

- Roscoe, A. CSP is expressive enough for π. In Reflections on the Work of CAR Hoare; Springer, 2010; pp. 371–404. [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, A.W. The theory and practice of concurrency; Prentice Hall, 1998. The text book teaching material can be found at http://www.comlab.ox.ac.uk/publications/books/concurrency/.

- FDR 4.2 Documentation. https://cocotec.io/fdr/manual/. Accessed: April 29, 2025.

- Herlihy, M.P.; Wing, J.M. Linearizability: a correctness condition for concurrent objects. ACM Trans. Program. Lang. Syst. 1990, 12, 463–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, A.W. Understanding Concurrent Systems; Springer, 2010.

- Gibson-Robinson, T.; Armstrong, P.; Boulgakov, A.; Roscoe, A.W. FDR3 — A Modern Refinement Checker for CSP. In Proceedings of the Tools and Algorithms for the Construction and Analysis of Systems; Ábrahám, E.; Havelund, K., Eds., Vol. 8413, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; 2014; pp. 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlihy, M.; Shavit, N.; Luchangco, V.; Spear, M. The art of multiprocessor programming; Newnes, 2020.

- Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.A.; Sun, J. Model checking linearizability via refinement. In Proceedings of the FM 2009: Formal Methods: Second World Congress, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2009. Proceedings 2. Springer, 2009, November 2-6; pp. 321–337. [CrossRef]

- O’Hearn, P.W.; Rinetzky, N.; Vechev, M.T.; Yahav, E.; Yorsh, G. Verifying linearizability with hindsight. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGACT-SIGOPS symposium on Principles of distributed computing, 2010, pp. 85–94. [CrossRef]

- Derrick, J.; Doherty, S.; Dongol, B.; Schellhorn, G.; Wehrheim, H. Verifying correctness of persistent concurrent data structures: a sound and complete method. Formal Aspects of Computing 2021, 33, 547–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongol, B.; Derrick, J. Verifying linearisability: A comparative survey. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2015, 48, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenJDK. LinkedBlockingQueue.java. https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/api/java/util/concurrent/LinkedBlockingQueue.html, 2018. Accessed: April 29, 2025.

| 1 | We have taken the implementation from the OpenJDK source available at https://github.com/openjdk/jdk/blob/master/src/java.base/share/classes/java/util/concurrent/ConcurrentLinkedQueue.java

|

| 2 | Assuming that v does not appear in P. |

| 3 | We have omitted the ✓ representing termination. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | We need to set an upper limit of the length of the queue here. This is necessary because CSP does not handle unlimited data structures. |

| Michael & Scott | Structured Java |

| node = new_node() | Node node = new Node(); |

| node→value = value | node.value.set(value); |

| node→next.ptr = null | node.next.set(null); |

| Node tail; | |

| Node next; | |

| loop | while (true) |

| tail = Q→Tail | tail = Q.tail.get(); |

| next = tail.ptr→next | next = tail.next.get(); |

| if tail == Q→Tail | if (tail == Q.tail.get()) { |

| if next.ptr == null | if (next == null) { |

| ifCAS(&tail.ptr→next, next, node) | if (tail.next.compareAndSet(next, node)) { |

| break | break; |

| endif | } |

| } | |

| else | else { |

| CAS(&Q→Tail, tail, next.ptr)| | Q.tail.compareAndSet(tail, next); |

| endif | } |

| endif | } |

| endloop | } |

| CAS(&Q→Tail, tail, node)| | Q.tail.compareAndSet(tail, node);| |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).