Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Setting and Study Design

Participants

Instrument and Variables for Data Collection

Data Collection and Study Procedures

Data Analysis

Ethics

3. Results

Sociodemographic and Obstetric Characteristics

Physical and Sedentary Activity Patterns

Proportion of Pregnant Women Meeting the WHO Recommendation

Variability of Compliance with WHO Physical Activity Recommendations for Health According to Sociodemographic and Obstetric Variables

Variability of Physical Activity by Domain, MET Minutes/Week and Sedentary Behaviour According to Sociodemographic Variables

Physical Activity by Domain, MET-Minutes, and Sedentary Behaviour Variability in Relation to Obstetric Variables

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACOG | American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. |

| ESDRM | Sport Sciences School of Rio Maior – Santarém Polytechnic University, Portugal |

| GPAQ | Global Physical Activity Questionnaire. |

| IOC | International Olympic Committee. |

| MET | Metabolic Equivalents of Task. |

| MVPA | Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. |

| PA | Physical activity. |

| RANZCOG | Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologist. |

| SPRINT | Sport Physical Activity and Health Research & Innovation Center, Portugal. |

| US DHHS | United States Department of Health and Human Services. |

| WHO | World Health Organization. |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior. 2020;3(2):115-118. doi:10.1016/j.smhs.2021.05.001. [CrossRef]

- Dipietro L, Evenson KR, Bloodgood B, et al. Benefits of Physical Activity during Pregnancy and Postpartum: An Umbrella Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(6):1292-1302. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001941. [CrossRef]

- Pereira MA, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman KP, et al. Predictors of change in physical activity during and after pregnancy: Project Viva. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):312-319. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.017. [CrossRef]

- Okely AD, Kontsevaya A, Ng J, Abdeta C. 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior. Sports Med Health Sci. 2021;3(2):115-118. doi:10.1016/j.smhs.2021.05.001. [CrossRef]

- Mudd LM, Owe KM, Mottola MF, Pivarnik JM. Health benefits of physical activity during pregnancy: an international perspective. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(2):268-277. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31826cebcb. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari N, Joisten C. Impact of physical activity on course and outcome of pregnancy from pre- to postnatal. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75(12):1698-1709. doi:10.1038/s41430-021-00904-7. [CrossRef]

- Xie W, Zhang L, Cheng J, et al. Physical activity during pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):594. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-18131-7. [CrossRef]

- Melzer K, Schutz Y, Boulvain M, Kayser B. Physical activity and pregnancy: cardiovascular adaptations, recommendations and pregnancy outcomes. Sports Med. 2010;40(6):493-507. doi:10.2165/11532290-000000000-00000. [CrossRef]

- Grau A, Sánchez Del Pino A, Amezcua-Prieto C, et al. An umbrella review of systematic reviews on interventions of physical activity before pregnancy, during pregnancy, and postpartum to control and/or reduce weight gain. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2024;166(3):915-931. doi:10.1002/ijgo.15453. [CrossRef]

- Dhar P, Sominsky L, O'Hely M, et al. Physical activity and circulating inflammatory markers and cytokines during pregnancy: A population-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2024;103(9):1808-1819. doi:10.1111/aogs.14870. [CrossRef]

- Cai C, Busch S, Wang R, Sivak A, Davenport MH. Physical activity before and during pregnancy and maternal mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Affect Disord. 2022;309:393-403. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.143. [CrossRef]

- Davenport MH, McCurdy AP, Mottola MF, et al. Impact of prenatal exercise on both prenatal and postnatal anxiety and depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(21):1376-1385. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099697. [CrossRef]

- González-Cazorla E, Brenes-Romero AP, Sánchez-Gómez MJ, et al. Physical Activity in Work and Leisure Time during Pregnancy, and Its Influence on Maternal Health and Perinatal Outcomes. J Clin Med. 2024;13(3):723. doi:10.3390/jcm13030723. [CrossRef]

- Wu D, Chen S, Zhong X, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with antenatal depressive symptoms across trimesters: a study of 110,584 pregnant women covered by a mobile app-based screening programme in Shenzhen, China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024;24(1):480. doi:10.1186/s12884-024-06680-z. [CrossRef]

- Ekelöf K, Andersson O, Holmén A, et al. Depressive symptoms postpartum is associated with physical activity level the year prior to giving birth - A retrospective observational study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2021;29:100645. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100645. [CrossRef]

- Menke BR, Duchette C, Tinius RA, et al. Physical Activity during Pregnancy and Newborn Body Composition: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(12):7127. doi:10.3390/ijerph19127127. [CrossRef]

- Dieberger AM, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Harreiter J, et al; DALI Core Investigator group. Physical activity and sedentary time across pregnancy and associations with neonatal weight, adiposity and cord blood parameters: a secondary analysis of the DALI study. Int J Obes. 2023;47(9):873-881. doi:10.1038/s41366-023-01347-9. [CrossRef]

- Musakka ER, Ylilauri MP, Jalanka J, et al. Maternal exercise during pregnancy is associated with reduced risk of asthma in the child: A prospective birth cohort study. Med. 2025;6(2):100514. doi:10.1016/j.medj.2024.09.003. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Xiao Y, Bai S, et al. The Association Between Exercise During Pregnancy and the Risk of Preterm Birth. Int J Womens Health. 2024;16:219-228. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S447270. [CrossRef]

- Weng YM, Green J, Yu JJ, et al. The relationship between incidence of cesarean section and physical activity during pregnancy among pregnant women of diverse age groups: Dose-response meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2024;164(2):504-515. doi:10.1002/ijgo.14915. [CrossRef]

- Lv C, Lu Q, Zhang C, et al. Relationship between first trimester physical activity and premature rupture of membranes: a birth cohort study in Chinese women. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):1736. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-18791-5. [CrossRef]

- Claiborne A, Wisseman B, Kern K, et al. Exercise during pregnancy Dose: Influence on preterm birth outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2024;300:190-195. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2024.07.017. [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity guidelines for Americans. Oklahoma Nurse. 2018;53(4):25. doi:10.1249/fit.0000000000000472. [CrossRef]

- ACOG CO. Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(4):178–188. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004267. [CrossRef]

- Mottola MF, Davenport MH, Ruchat SM, et al. No. 367-2019 Canadian Guideline for Physical Activity throughout Pregnancy [published correction appears in J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(7):1067. doi:10.1016/j.jogc.2019.05.001.]. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40(11):1528-1537. doi:10.1016/j.jogc.2018.07.001. [CrossRef]

- The Royal Australian New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RANZCOG). Exercise during Pregnancy. 2016. https://ranzcog.edu.au/womens-health/patient-informationresources/exercise-during-pregnancy.

- Bø K, Artal R, Barakat R, et al. Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016/2017 evidence summary from the IOC expert group meeting, Lausanne. Part 5. Recommendations for health professionals and active women. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(17):1080-1085. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099351. [CrossRef]

- Department of Health & Social Care. UK Chief Medical Officer’s physical activity guidelines. 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5d839543ed915d52428dc134/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf.

- Sport Medicine Australia. SMA statement the benefits and risks of exercise during pregnancy. J Sci Med Sport. 2002;5(1):11-19. doi:10.1016/s1440-2440(02)80293-6. [CrossRef]

- Barakat R, et al. Guía de práctica clínica sobre la actividad física durante el embarazo [Spanish]. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. 2023. https://portal.guiasalud.es/gpc/actividad-fisica-embarazo/.

- Goya M, Miserachs M, SuyA, et al. Documento de consenso de la Sociedad Española de Obstetricia y Ginecologia (SEGO) y el Comité Español Interdisciplinario para la Prevención Vascular (CEIPV). Ventana de oportunidad: prevención del riesgo vascular en la mujer. Resultados adversos del embarazo y riesgo de enfermedad vascular [Consensus document of the Spanish Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (SEGO) and the Spanish Interdisciplinary Committee for Vascular Prevention (CEIPV). Window of opportunity: prevention of vascular risk in women]. 2023;97:e202310084.

- Muñoz J, Delgado M. (coord.) Guía de recomendaciones para la promoción de actividad física [Guide of recommendations for promoting physical activity]. Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Salud. 2010. https://acortar.link/3EniXS.

- Hayman M, Brown WJ, Brinson A, et al. Public health guidelines for physical activity during pregnancy from around the world: a scoping review. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(14):940-947. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2022-105777. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Jose C, Mottola MF, Palacio M, et al. Impact of Physical Activity Interventions on High-Risk Pregnancies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pers Med. 2023;14(1):14. doi:10.3390/jpm14010014. [CrossRef]

- Srugo SA, Fernandes da Silva D, Menard LM, et al. Recent Patterns of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Among Pregnant Adults in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2023;45(2):141-149. doi:10.1016/j.jogc.2022.11.011. [CrossRef]

- Ning Y, Williams MA, Dempsey JC, et al. Correlates of recreational physical activity in early pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003;13(6):385-393. doi:10.1080/jmf.13.6.385.393. [CrossRef]

- Román-Gálvez MR, Amezcua-Prieto C, Salcedo-Bellido I, et al. Physical activity before and during pregnancy: A cohort study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;152:374-381.

- Mendinueta A, Esnal H, Arrieta H, et al. What Accounts for Physical Activity during Pregnancy? A Study on the Sociodemographic Predictors of Self-Reported and Objectively Assessed Physical Activity during the 1st and 2nd Trimesters of Pregnancy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2517. doi:10.3390/ijerph17072517. [CrossRef]

- Todorovic J, Terzic-Supic Z, Bjegovic-Mikanovic V, et al. Factors Associated with the Leisure-Time Physical Activity (LTPA) during the First Trimester of the Pregnancy: The Cross-Sectional Study among Pregnant Women in Serbia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1366. doi:10.3390/ijerph17041366. [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist M, Lindkvist M, Eurenius E, et al. Leisure time physical activity among pregnant women and its associations with maternal characteristics and pregnancy outcomes. Sex Reprod Health. 2016;9:14-20.

- Lynch KE, Landsbaugh JR, Whitcomb BW, et al. Physical activity of pregnant Hispanic women. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(4):434-439. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.020. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Zhang L, Xu P, et al. Physical activity levels and influencing factors among pregnant women in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2024;158:104841. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104841. [CrossRef]

- Sarno L, Borrelli P, Mennitti C, et al. Adherence to physical activity among pregnant women in Southern Italy: results of a cross-sectional survey. Midwifery. 2024;137:104102. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2024.104102. [CrossRef]

- Okafor UB, Goon DT. Physical Activity Level during Pregnancy in South Africa: A Facility-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7928. doi:10.3390/ijerph17217928. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento SL, Surita FG, Godoy AC, et al. Physical Activity Patterns and Factors Related to Exercise during Pregnancy: A Cross Sectional Study [publication correction: appears in PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133564.10.1371/journal.pone.0133564.]. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128953. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128953. [CrossRef]

- Gaston A, Vamos CA. Leisure-time physical activity patterns and correlates among pregnant women in Ontario, Canada. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(3):477-484. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-1021-z. [CrossRef]

- Amezcua-Prieto C, Olmedo-Requena R, Jiménez-Mejías E, et al. Factors associated with changes in leisure time physical activity during early pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121(2):127-131. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.11.021. [CrossRef]

- Gaston A, Cramp A. Exercise during pregnancy: a review of patterns and determinants. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(4):299-305. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2011.02.006. [CrossRef]

- Evenson KR, Savitz DA, Huston SL. Leisure-time physical activity among pregnant women in the US. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18(6):400-407. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00595.x. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi AEM, Paula JA, Almeida MA, et al. Trend in physical activity patterns of pregnant women living in Brazilian capitals. Rev Saude Publica. 2022;56:42. doi:10.11606/s1518-8787.2022056003300. [CrossRef]

- Petersen AM, Leet TL, Brownson RC. Correlates of physical activity among pregnant women in the United States. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(10):1748-1753. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000181302.97948.90. [CrossRef]

- Kubler JM, Edwards C, Cavanagh E, et al. Maternal physical activity and sitting time and its association with placental morphology and blood flow during gestation: Findings from the Queensland Family Cohort study. J Sci Med Sport. 2024;27(7):480-485. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2024.02.011. [CrossRef]

- Lindberger E, Ahlsson F, Johansson H, et al. Associations of maternal sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in early to mid-pregnancy with infant outcomes: A cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2024;103(12):2522-2531. doi:10.1111/aogs.14983. [CrossRef]

- Khojah N, Gibbs BB, Alghamdi SA, et al. Associations Between Domains and Patterns of Sedentary Behavior with Sleep Quality and Duration in Pregnant Women. Healthcare (Basel). 2025;13(3):348. doi:10.3390/healthcare13030348. [CrossRef]

- Osumi A, Kanejima Y, Ishihara K, et al. Effects of Sedentary Behavior on the 556 Complications Experienced by Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. Reprod Sci. 2024;31(2):352-365. doi:10.1007/s43032-023-01321-w. [CrossRef]

- Evenson KR, Wen F. Prevalence and correlates of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior among US pregnant women. Prev Med. 2011;53(1-2):39-43. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.04.014. [CrossRef]

- Fazzi C, Saunders DH, Linton K, et al. Sedentary behaviours during pregnancy: a systematic review. Int J BehavNutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12966-017-0485-z. [CrossRef]

- Nagai M, Tsuchida A, Matsumura K, et al; Japan Environment and Children’s Study Group. Factors related to sedentary behavior of pregnant women during the second/third trimester: prospective results from the large-scale Japan Environment and Children's Study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):3182. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-20574-x. [CrossRef]

- Corrales-Gutierrez I, Mendoza R, Gomez-Baya D, Leon-Larios F. Understanding the Relationship between Predictors of Alcohol Consumption in Pregnancy: Towards Effective Prevention of FASD. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1388. doi:10.3390/ijerph17041388. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza R, Morales-Marente E, Palacios MS, et al. Health advice on alcohol consumption in pregnant women in Seville (Spain). Gac Sanit. 2020;34(5):449-458. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2018.11.008. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong T, Bull F. Development of the World Health Organization Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). J Public Health. 2006;14:66-70. doi:10.1007/s10389-006-0024-x. [CrossRef]

- Bull FC, Maslin TS, Armstrong T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): nine country reliability and validity study. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(6):790-804. doi:10.1123/jpah.6.6.790. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann SD, Heumann KJ, Der Ananian CA, Ainsworth BE. Validity and Reliability of the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). Measurement Physical Edu Exercise Sci. 2013;17(3):221-235. doi:10.1080/1091367X.2013.805139. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide. Surveillance and Population-Based Prevention, Prevention of Noncommunicable Diseases Department, World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/ncds/ncd-surveillance/gpaq-analysis-guide.pdf.

- Algallai N, Martin K, Shah K, et al. Reliability and validity of a Global Physical Activity Questionnaire adapted for use among pregnant women in Nepal. Archives Public Health.2023;81(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s13690-023-01032-3. [CrossRef]

- Meander L, Lindqvist M, Mogren I, et al. Physical activity and sedentary time during pregnancy and associations with maternal and fetal health outcomes: an epidemiological study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):166. doi:10.1186/s12884-021-03627-6. [CrossRef]

- Rial-Vázquez J, Vila-Farinas A, Varela-Lema L, et al. Actividad física en el embarazo y puerperio: prevalencia y recomendaciones de los profesionales sanitarios [Physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum: prevalence and healthcare professional recommendations]. Aten Primaria. 2023;55(5):102607. doi:10.1016/j.aprim.2023.102607. [CrossRef]

- Garland M, Wilbur JE, Semanik P, Fogg L. Correlates of Physical Activity During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review with Implications for Evidence-based Practice. Worldviews Evidence-Based Nursing. 2019;16(4):310–318. doi:10.1111/wvn.12391. [CrossRef]

- Fell DB, Joseph KS, Armson BA, Dodds L. The impact of pregnancy on physical activity level. Maternal Child Health J. 2009;13(5):597–603. doi:10.1007/s10995-008-0404-7. [CrossRef]

- Mok KC, Liu M, Wang X. The physical activity and sedentary behavior among pregnant women in Macao: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2025;20(1):e0318352. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0318352. [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Ugarriza R, Mielgo-Ayuso J, Benito PJ, et al.; EXERNET Study Group. Physical activity assessment in the general population; instrumental methods and new technologies. Nutr Hosp. 2015;31Suppl 3:219-26. doi:10.3305/nh.2015.31.sup3.8769. [CrossRef]

- Kozai AC, Jones MA, Borrowman JD, et al. Patterns of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep across pregnancy before and during two COVID pandemic years. Midwifery. 2025;141:104268. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2024.104268. [CrossRef]

- Yimer A, Endris S, Wossen A, Abate M. Pregnant women's knowledge, attitude, and practice toward physical exercise during pregnancy and its associated factors at Dessie town health institutions, Ethiopia. AJOG Glob Rep. 2024;4(4):100391. doi:10.1016/j.xagr.2024.100391. [CrossRef]

- Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. The Lancet. Child Ado Health. 2020;4(1):23-35. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2. [CrossRef]

- Duffey K, Barbosa A, Whiting S, et al. Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity Participation in Adolescent Girls: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Front Public Health. 2021;9:743935.10.3389/fpubh.2021.743935.

- Gonçalves H, Soares ALG, Domingues MR, et al. Why are pregnant women physically inactive? A qualitative study on the beliefs and perceptions about physical activity during pregnancy. Cad Saude Publica. 2024;40(1):e00097323. doi:10.1590/0102-311XEN097323. [CrossRef]

- Heslehurst N, Newham J, Maniatopoulos G, et al. Implementation of pregnancy weight management and obesity guidelines: a meta-synthesis of healthcare professionals' barriers and facilitators using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Obes Rev. 2014;15(6):462-486.10.1111/obr.12160.

- Panton ZA, Smith S, Duggan M, et al. The Significance of Physical Activity Education: A Survey of Medical Students. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2023;18(6):832-842. doi:10.1177/15598276231187838. [CrossRef]

- Corfe BM, Smith T, Heslehurst N, et al. Long overdue: undergraduate nutrition education for medical students. Br J Nutr. 2022;129(6):1-2. doi:10.1017/S0007114522001647. [CrossRef]

- Jones G, Macaninch E, Mellor DD, et al. Putting nutrition education on the table: development of a curriculum to meet future doctors' needs. Br J Nutr. 2022;129(6):1-9. doi:10.1017/S0007114522001635. [CrossRef]

- Dilworth S, Doherty E, Mallise C, et al. Barriers and enablers to addressing smoking, nutrition, alcohol consumption, physical activity and gestational weight gain (SNAP-W) as part of antenatal care: A mixed methods systematic review. Implement Sci Commun. 2024;5(1):112. doi:10.1186/s43058-024-00655-z. [CrossRef]

- Santo EC, Forbes PW, Oken E, Belfort MB. Determinants of physical activity frequency and provider advice during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):286. doi:10.1186/s12884-017-1460-z. [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama AJ, Carr D, Granberg EM, et al. How and why weight stigma drives the obesity 'epidemic' and harms health. BMCMed. 2018;16(1):123. doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1116-5. [CrossRef]

- Hill B, Azzari A, Botting KJ, et al. The Challenge of Weight Stigma for Women in the Preconception Period: Workshop Recommendations for Action from the 5th European Conference on Preconception Health and Care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(22):7034. doi:10.3390/ijerph20227034. [CrossRef]

- Laeremans M, Dons E, Avila-Palencia I, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour in daily life: A comparative analysis of the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) and the Sense Wear armband. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177765. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177765. [CrossRef]

- Meh K, Jurak G, Sorić M, et al. Validity and Reliability of IPAQ-SF and GPAQ for Assessing Sedentary Behaviour in Adults in the European Union: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4602. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094602. [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 385 | 31.84 | 5.99 | |

| Approximate weight (kg) | 383 | 70.04 | 14.21 | |

| Approximate height (cm) | 383 | 163.30 | 6.12 | |

| Body Mass Index (Kg/height2) | 382 | 26.26 | 5.15 | |

| Variables | Categories | N | % | |

| Age | Less than 30 years | 119 | 30.9 | |

| 30 to 35 years | 110 | 28.6 | ||

| More than 35 years | 156 | 40.5 | ||

| Educational level | No studies | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Primary education | 175 | 45.5 | ||

| Secondary studies | 87 | 22.6 | ||

| Higher education | 119 | 30.9 | ||

| Currently studying | No | 328 | 85.2 | |

| Yes | 57 | 14.8 | ||

| Employment status | Full time | 157 | 41.1 | |

| Part time | 82 | 21.5 | ||

| Unemployed | 68 | 17.8 | ||

| Other | 75 | 18.6 | ||

| Size of place of residence | Up to 5,000 inhabitants | 45 | 11.7 | |

| From 5,001 to 20,000 inhabitants | 82 | 21.3 | ||

| From 20,001 to 50,000 inhabitants | 137 | 35.6 | ||

| More than 50,000 inhabitants | 121 | 31.4 | ||

| In a relationship | Yes | 382 | 99.2 | |

| No | 3 | 0.8 | ||

| Current language spoken at home |

Spanish | 347 | 90.1 | |

| Other (including bilinguals) | 38 | 9.9 | ||

| Language spoken at home as a child |

Spanish | 349 | 90.6 | |

| Other (including bilingual) | 36 | 9.4 | ||

| Country of birth | Spain | 353 | 91.7 | |

| Another country | 32 | 8.3 | ||

| Body Mass Index | Underweight | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Normal weight | 182 | 47.6 | ||

| Overweight | 116 | 30.4 | ||

| Obesity | 79 | 20.7 | ||

| Total sample size: 385 | ||||

| Variables | N | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of pregnancies including the current one | 385 | 2.06 | 1.11 | |

| Number of vaginal births | 385 | 0.48 | 0.74 | |

| Number of cesarean births | 385 | 0.12 | 0.34 | |

| Number of miscarriages | 385 | 0.37 | 0.72 | |

| Number of abortions | 385 | 0.10 | 0.35 | |

| Number of health problems during pregnancies ended in live birth | 190 | 0.25 | 0.63 | |

| Age at first pregnancy (years) | 383 | 27.50 | 6.35 | |

| Date of initiation of health care (in gestational weeks) | 380 | 6.42 | 2.40 | |

| Number of weeks since last menstrual period | 382 | 20.23 | 0.69 | |

| Variables | Categories | N | % | |

| Gravidity (number of pregnancies including the current one) | Primigravida | 142 | 36.9 | |

| Multigravida | 243 | 63.1 | ||

| Health problems during pregnancies ended in live birth | No | 159 | 83.7 | |

| Yes | 31 | 16.3 | ||

| Pregnancy planning | No | 90 | 23.4 | |

| Yes | 294 | 76.6 | ||

| Assisted reproduction pregnancy | No | 254 | 87.3 | |

| Yes | 37 | 12.7 | ||

| High-risk pregnancy care | No | 325 | 84.4 | |

| Yes | 60 | 15.6 | ||

| Trimester of pregnancy awareness | First trimester | 379 | 98.7 | |

| Second trimester | 5 | 1.3 | ||

| Professional health careduring pregnancy | No | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Yes | 383 | 99.5 | ||

| Variables | N | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total PA (work, travel to and from places, and leisure) (min/week) | 384 | 902.85 | 1,061.31 | |

| Total work PA (min/week) | 382 | 596.31 | 1,037.52 | |

| Vigorous work PA (min/week) | 382 | 201.28 | 683.26 | |

| Moderate work PA (min/week) | 380 | 397.11 | 818.45 | |

| Total active travel to and from places (min/week) | 384 | 97.57 | 211.28 | |

| Total leisure PA (min/week) | 384 | 212.07 | 262.34 | |

| Vigorous leisure PA (min/week) | 384 | 2.34 | 34.20 | |

| Moderate leisure PA (min/week) | 384 | 209.73 | 261.99 | |

| Total vigorous PA (work and leisure) (min/week) | 384 | 202.58 | 681.80 | |

| Total moderate PA (work, travel to and from places, and leisure) (min/week) | 384 | 700.27 | 858.64 | |

| Total % moderate PA (min/week) | 339 | 90.46 | 26.66 | |

| Number of MET-min/week | 384 | 4,421.70 | 6,254.84 | |

| Sedentary behaviour (min/day) | 383 | 234.61 | 162.99 | |

| Variables | Categories | N | % | |

| Engaged in PA at work | Yes | 128 | 33.5 | |

| No | 254 | 66.5 | ||

| Engaged in PA for travel to and from places | Yes | 139 | 36.2 | |

| No | 245 | 63.8 | ||

| Engaged in PA for leisure | Yes | 237 | 61.7 | |

| No | 147 | 38.3 | ||

| Engaged in some type of PA | Yes | 324 | 84.4 | |

| No | 60 | 15.6 | ||

| Engaged in vigorous PA | Yes | 42 | 10.9 | |

| No | 342 | 89.1 | ||

| Engaged in moderate PA | Yes | 312 | 81.3 | |

| No | 72 | 18.8 | ||

| Engaged in at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity PA per week. Met WHO requirement of PA during pregnancy | Yes | 283 | 73.7 | |

| No | 101 | 26.3 | ||

| Variables / Categories | Yes | N | Statistical parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (2) = 2.56; p = 0.28;Cramer’s V = 0.08 |

| Less than 30 years | 70.6 | 29.4 | |

| From 30 to 35 years | 70.9 | 29.1 | |

| More than 35 years | 78.1 | 21.9 | |

| Educational level | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (3) = 5.44; p = 0.14;Cramer’s V = 0.12 |

| No studies | 25.0 | 75.0 | |

| Primary education | 73.0 | 27.0 | |

| Secondary studies | 77.0 | 23.0 | |

| Higher education | 73.9 | 26.1 | |

| Currently studying | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (1) = 5.2; p = 0.02;Cramer’s V = 0.12 |

| No | 71.6 | 28.4 | |

| Yes | 86.0 | 14.0 | |

| Employment status | N=280 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (3) = 1.27; p = 0.74;Cramer’s V = 0.06 |

| Full time | 73.1 | 26.9 | |

| Part time | 78.0 | 22.0 | |

| Unemployed | 70.6 | 29.4 | |

| Other | 72.0 | 28.0 | |

| Size of place of residence | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (3) = 4.52; p = 0.21;Cramer’s V = 0.11 |

| Up to 5,000 inhabitants | 77.8 | 22.2 | |

| From 5,001 to 20,000 inhabitants | 81.7 | 18.3 | |

| From 20,001 to 50,000 inhabitants | 70.6 | 29.4 | |

| More than 50,000 inhabitants | 70.2 | 29.8 | |

| In a relationship | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (1) = 0.08; p = 0.78;Cramer’s V = 0.01 |

| Yes | 73.8 | 26.2 | |

| No | 66.7 | 33.3 | |

| Current language spoken at home | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (1) = 0.15; p = 0.7;Cramer’s V = 0.02 |

| Spanish | 74.0 | 26.0 | |

| Other (including bilinguals) | 71.1 | 28.9 | |

| Language spoken at home as a child | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (1) = 0.96; p = 0.33;Cramer’s V = 0.05 |

| Spanish | 73.0 | 27.0 | |

| Other (including bilinguals) | 80.6 | 19.4 | |

| Country of birth | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (1) = 0.03; p = 0.86;Cramer’s V = 0.01 |

| Spain | 73.6 | 26.4 | |

| Another country | 75.0 | 25.0 | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | N=280 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (3) = 1.42; p = 0.7;Cramer’s V = 0.06 |

| Underweight | 80.0 | 20.0 | |

| Normal weight | 74.2 | 25.8 | |

| Overweight | 69.8 | 30.2 | |

| Obesity | 76.9 | 23.1 | |

| Gravidity (Number of pregnancies including the current one) | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (1) = 5.04; p = 0.02;Cramer’s V = 0.11 |

| Primigravida | 80.3 | 19.7 | |

| Multigravida | 69.8 | 30.2 | |

| Health problems during pregnancies ended in live birth | N=130 % |

N=59 % |

Chi2 (1) = 0.07; p = 0.79;Cramer’s V = 0.02 |

| No | 69.2 | 30.8 | |

| Yes | 66.7 | 33.3 | |

| Pregnancy planning | N=217 % |

N=73 % |

Chi2 (1) = 1.36; p = 0.24;Cramer’s V = 0.06 |

| No | 68.9 | 31.1 | |

| Yes | 75.1 | 24.9 | |

| Assisted reproduction pregnancy | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (1) = 0; p = 0.98;Cramer’s V = 0 |

| No | 74.8 | 25.2 | |

| Yes | 75.0 | 25.0 | |

| High-risk pregnancy care | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (1) = 0.5; p = 0.48;Cramer’s V = 0.04 |

| No | 74.4 | 25.6 | |

| Yes | 70.0 | 30.0 | |

| Trimester of pregnancy awareness | N=282 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (1) = 0.48; p = 0.49;Cramer’s V = 0.04 |

| First trimester | 73.8 | 26.2 | |

| Second trimester | 60.0 | 40.0 | |

| Professional health care during pregnancy | N=283 % |

N=101 % |

Chi2 (1) = 0.58; p = 0.45;Cramer’s V = 0.04 |

| No | 50.0 | 50.0 | |

| Yes | 73.8 | 26.2 |

| Variables / Categories | Leisure PA min/week | Work PA min/week | Travel to and from places PA min/week | MET minutes/week | Sedentary minutes/day | ||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Sign. | Mean | SD | Sign. | Mean | SD | Sign. | Mean | SD | Sign. | Mean | SD | Sign. | |

| Age | p=0.06 | p=0.17 | p=0.6 | p=0.18 | p=0.29 | ||||||||||

| Less than 30 years | 182.86 | 221.12 | 770.08 | 1,193.63 | 108.28 | 233.72 | 5,316.81 | 7,536.17 | 215.80 | 126.82 | |||||

| 30 to 35 years | 176.68 | 197.66 | 528.91 | 934.35 | 86.62 | 215.12 | 3,677.20 | 5,254.22 | 267.86 | 193.74 | |||||

| More than 35 years | 259.61 | 319.71 | 509.61 | 965.19 | 97.13 | 190.35 | 4,262.84 | 5,762.11 | 225.39 | 161.33 | |||||

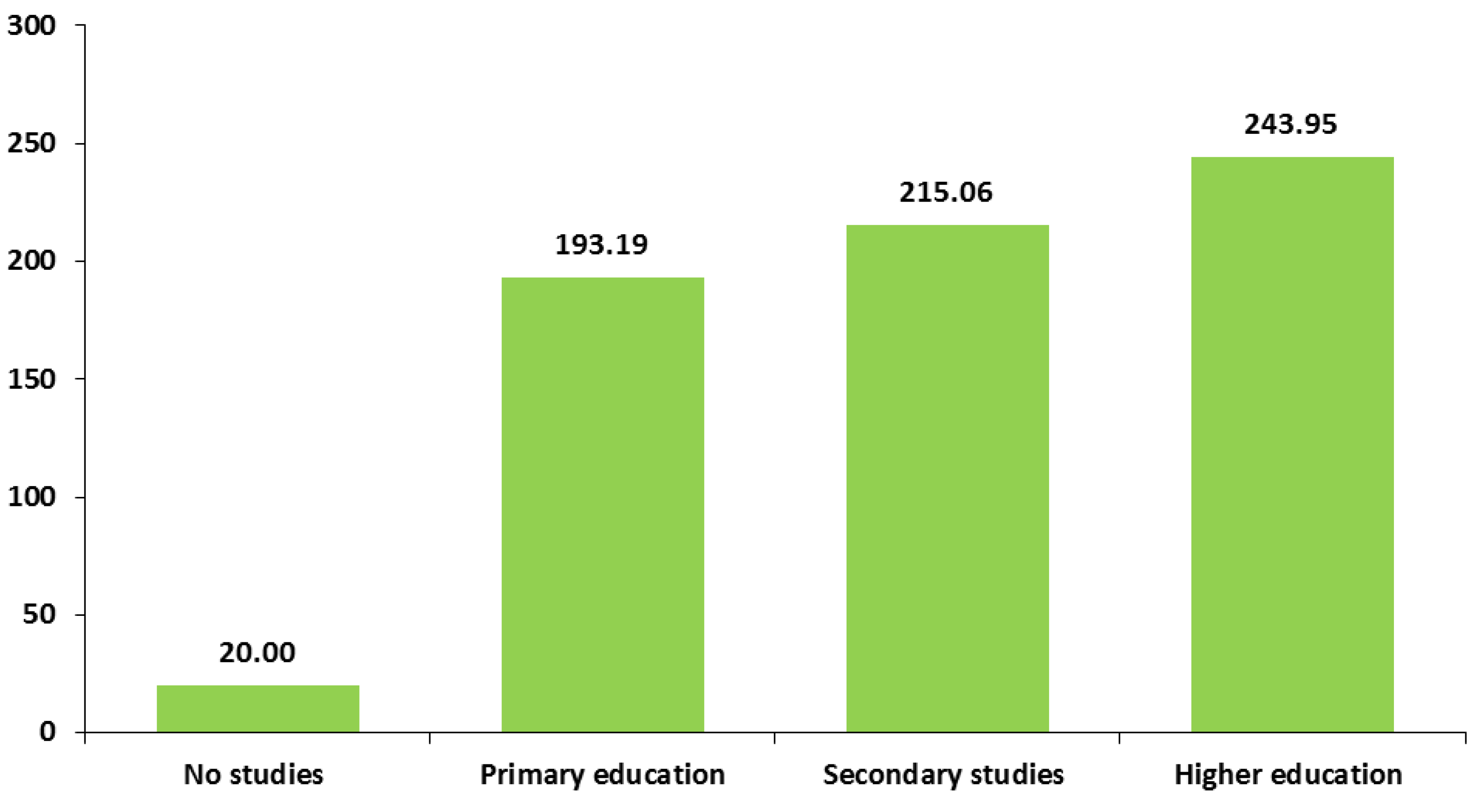

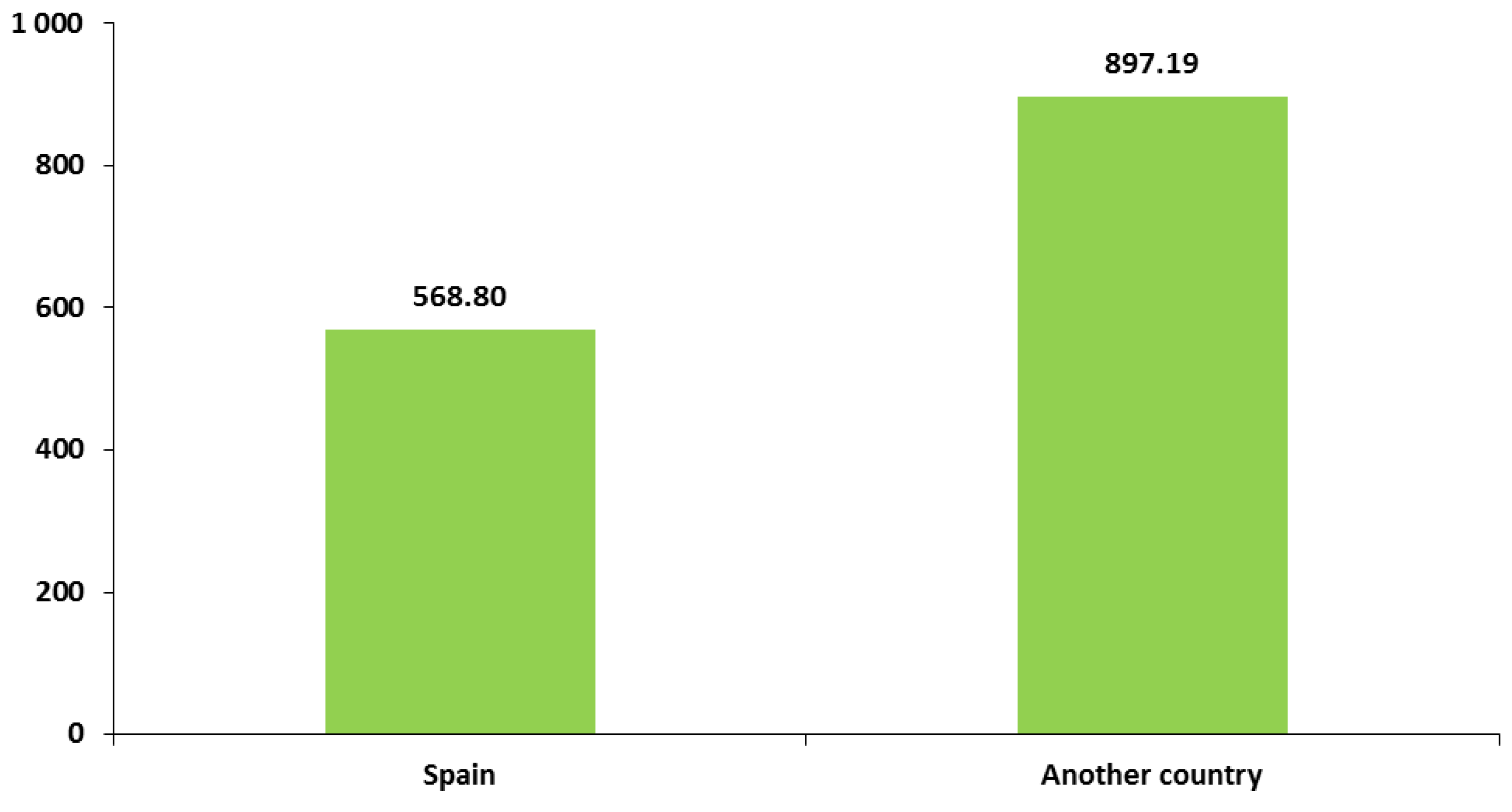

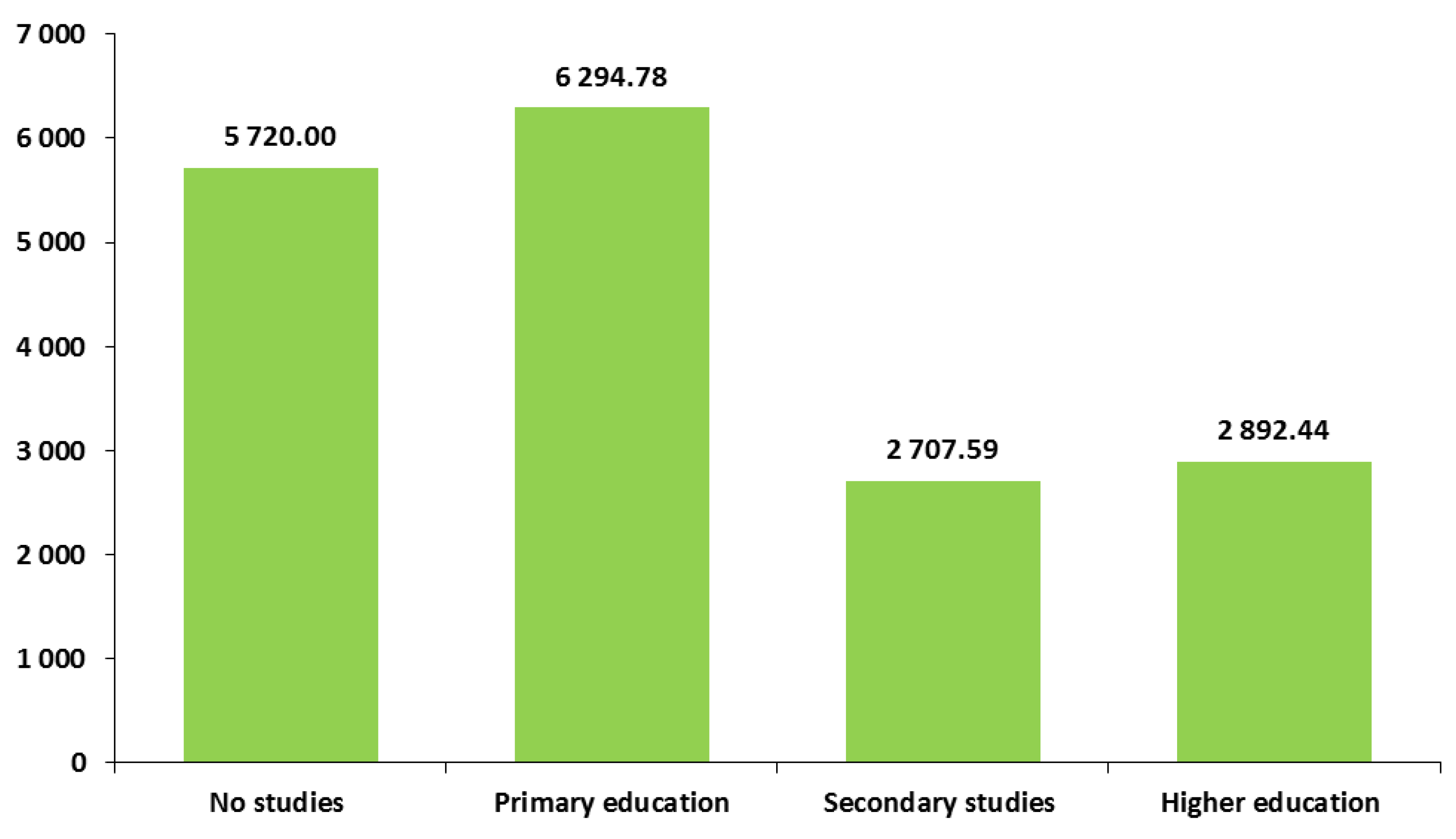

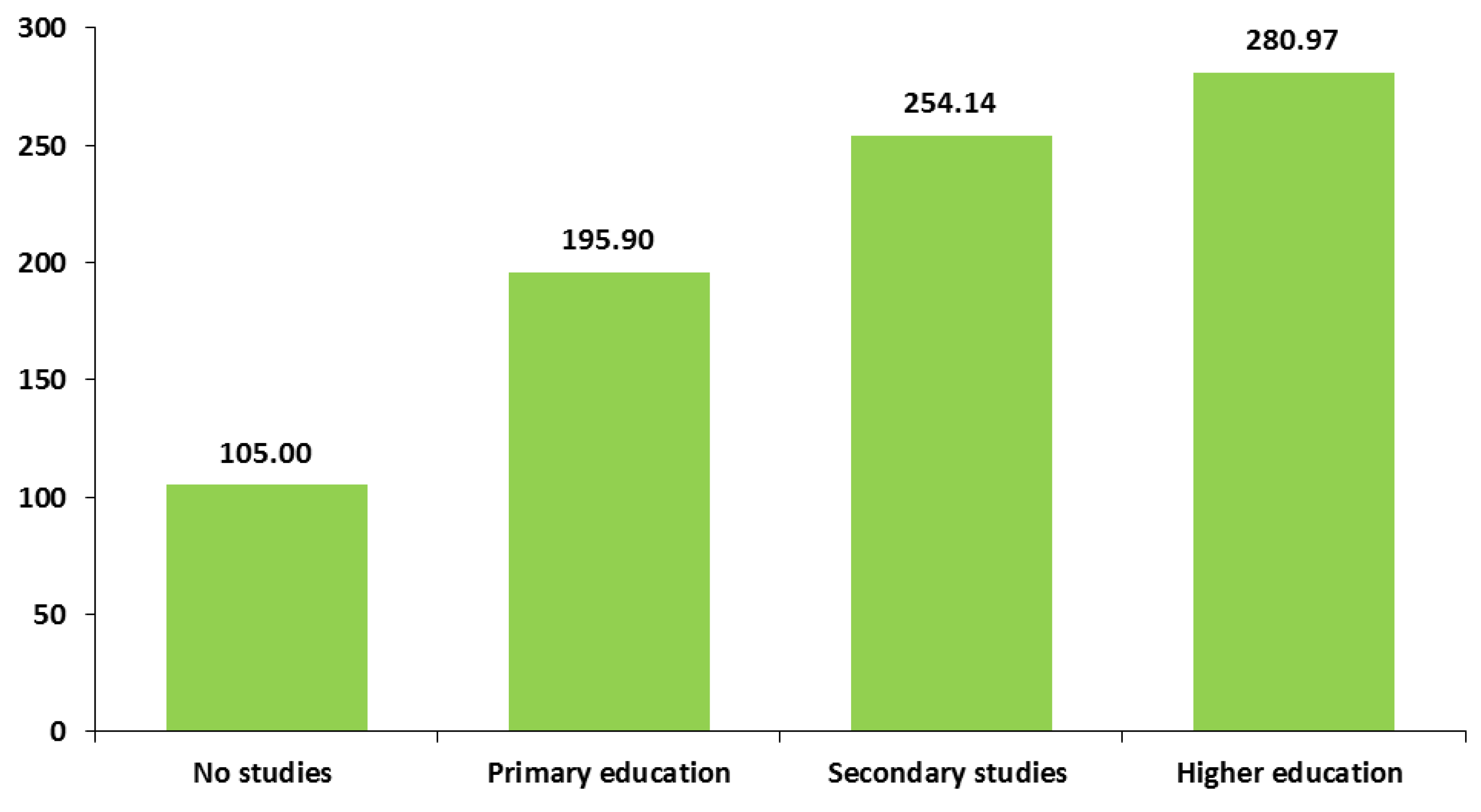

| Educational level | p<0.05 | p<0.01 | p=0.28 | p<0.01 | p<0.01 | ||||||||||

| No studiesa | 20.00 | 40.00 | c, d | 727.50 | 1,337.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5,720.00 | 10,750.70 | 105.00 | 51.96 | c, d | |||

| Primary education b | 193.19 | 255.03 | d | 916.42 | 1,233.32 | c, d | 100.56 | 239.02 | 6,294.78 | 7,813.60 | c, d | 195.90 | 127.05 | c, d | |

| Secondary studiesc | 215.06 | 198.56 | a | 330.70 | 758.30 | b | 92.53 | 178.85 | 2,707.59 | 3,448.23 | b | 254.14 | 166.90 | a, b | |

| Higher education d | 243.95 | 310.54 | a, b | 318.49 | 720.22 | b | 100.17 | 193.53 | 2,892.44 | 4,014.44 | b | 280.97 | 192.05 | a, b | |

| Currently studying | p<0.05 | p<0.01 | p=0.12 | p=0.73 | p=0.19 | ||||||||||

| No | 198.06 | 235.31 | 658.06 | 1,085.14 | 95.99 | 215.94 | 4,687.38 | 6,570.30 | 230.67 | 162.83 | |||||

| Yes | 292.46 | 375.01 | 244.21 | 602.12 | 106.67 | 183.74 | 2,897.54 | 3,673.28 | 257.11 | 163.52 | |||||

| Employment situation | p=0.87 | p<0.05 | p=0.27 | p=0.12 | p=0.38 | ||||||||||

| Full time e | 212.44 | 240.42 | 592.18 | 1,068.96 | g | 76.28 | 192.99 | 4,132.05 | 5,797.18 | 268.74 | 201.44 | ||||

| Part time f | 228.66 | 331.38 | 654.51 | 1,010.48 | g | 102.20 | 204.62 | 4,869.27 | 6,872.31 | 209.09 | 129.92 | ||||

| Unemployed g | 195.66 | 211.93 | 354.55 | 937.02 | e, f, h | 130.41 | 248.83 | 3,180.18 | 5,285.89 | 225.00 | 127.12 | ||||

| Other h | 203.93 | 263.30 | 777.87 | 1,075.26 | g | 106.13 | 218.88 | 5,767.73 | 7,150.25 | 194.07 | 115.87 | ||||

| Size of place of residence | p=0.51 | p<0.05 | p=0.66 | p<0.05 | p=0.13 | ||||||||||

| Up to 5,000 inhabitants i | 225.11 | 227.89 | 688.89 | 1,178.00 | 139.00 | 351.39 | 5,446,67 | 8,075.07 | 196.33 | 129.03 | |||||

| 5,001 to 20,000 inhabitants j | 256.71 | 352.68 | 764.63 | 998.78 | l | 93.35 | 166.48 | 5,278.29 | 5,911.79 | k, l | 199.76 | 125.89 | |||

| 20,001 to 50,000 inhabitants k | 191.25 | 227.36 | 583.90 | 1,000.03 | 73.42 | 156.57 | 4,247.50 | 5,947.52 | i | 246.21 | 169.26 | ||||

| More than 50,000 inhabitants l | 200.37 | 237.57 | 459.50 | 1,042.73 | i | 112.17 | 222.22 | 3,655.80 | 6,004.34 | i | 259.63 | 183.45 | |||

| In a relationship | p=0.92 | p=0.75 | p=0.21 | p=0.8 | p=0.37 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 212.44 | 263.09 | 593.27 | 1,033.72 | 98.34 | 211.93 | 4,389.59 | 6,197.47 | 234.41 | 163.48 | |||||

| No | 165.00 | 158.03 | 980.00 | 1,697.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8,500.00 | 13,010.50 | 260.00 | 91.65 | |||||

| Current language spoken at home | p=0.78 | p=0.85 | p=0.56 | p=0.87 | p=0.53 | ||||||||||

| Spanish | 211.03 | 263.36 | 599.30 | 1,040.26 | 99.78 | 218.91 | 4,460.32 | 6,319.26 | 236.10 | 164.38 | |||||

| Other (Including bilinguals) | 221.58 | 256.06 | 569.21 | 1,025.60 | 77.50 | 121.57 | 4,070.00 | 5,699.70 | 221.05 | 151.12 | |||||

| Language spoken at home as a child | p=0.45 | p<0.05 | p=0.2 | p=0.07 | p<0.05 | ||||||||||

| Spanish | 211.32 | 266.63 | 564.62 | 1,025.29 | 102.82 | 219.05 | 4,314.52 | 6,283.85 | 239.28 | 164.97 | |||||

| Other (including bilinguals) | 219.31 | 219.62 | 900.83 | 1,118.29 | 46.81 | 99.13 | 5,457.78 | 5,951.16 | 189.58 | 136.31 | |||||

| Country of birth | p=0.84 | p<0.05 | p=0.74 | p=0.08 | p=0.38 | ||||||||||

| Spain | 213.78 | 268.38 | 568.80 | 1,027.84 | 99.88 | 216.43 | 4,309.52 | 6,243.45 | 235.83 | 162.32 | |||||

| Another country | 193.28 | 185.23 | 897.19 | 1,110.96 | 72.19 | 142.81 | 5,655.63 | 6,346.92 | 221.25 | 172.21 | |||||

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | p=0.29 | p=0.75 | p=0.08 | p=0.67 | p=0.15 | ||||||||||

| Underweight | 192.00 | 245.19 | 546.00 | 1,220.89 | 462.00 | 558.68 | 6,984.00 | 10,340.35 | 222.00 | 162.39 | |||||

| Normal weight | 237.91 | 290.53 | 536.35 | 976.92 | 85.21 | 187.09 | 3,923.91 | 5,552.11 | 240.82 | 165.78 | |||||

| Overweight | 188.06 | 234.35 | 598.17 | 1,036.30 | 99.61 | 237.23 | 4,607.93 | 6,479.77 | 245.78 | 165.90 | |||||

| Obesity | 184.10 | 233.09 | 743.46 | 1,176.17 | 99.49 | 173.46 | 5,182.05 | 7,209.59 | 208.46 | 153.80 | |||||

| Variables / Categories | Leisure PA min/week | Work PA min/week | Travel to and from places PA min/week | MET – min/week | Sedentary min./day | ||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Sign. | Mean | SD | Sign. | Mean | SD | Sign. | Mean | SD | Sign. | Mean | SD | Sign. | |

| Gravidity (number of pregnancies including the current one) | p<0.01 | p=0.07 | p=0.64 | p=0.64 | p<0.05 | ||||||||||

| Primigravida | 254.33 | 242.74 | 470.85 | 939.63 | 98.23 | 222.17 | 3,863.18 | 5,482.26 | 251.91 | 160.35 | |||||

| Multigravida | 187.27 | 270.61 | 670.54 | 1,086.39 | 97.19 | 205.09 | 4,749.42 | 6,655.75 | 224.52 | 163.99 | |||||

| Health problems during pregnancies ended in live birth | p=0.13 | p=0.9 | p=0.97 | p=0.43 | p=0.96 | ||||||||||

| No | 199.37 | 300.35 | 621.20 | 1,035.87 | 103.36 | 227.58 | 4,647.42 | 6,571.48 | 227.83 | 170.32 | |||||

| Yes | 123.17 | 198.20 | 580.34 | 997.64 | 96.33 | 197.37 | 3,506.00 | 5,120.43 | 205.50 | 129.04 | |||||

| Pregnancy planning | p=0.34 | p=0.28 | p=0.51 | p=0.51 | p=0.6 | ||||||||||

| No | 195.67 | 243.24 | 646.52 | 1,002.53 | 121.92 | 274.21 | 4,806.36 | 6,271.93 | 213.03 | 125.34 | |||||

| Yes | 217.83 | 268.26 | 580.58 | 1,050.89 | 90.43 | 188.06 | 4,308.81 | 6,265.72 | 241.76 | 172.40 | |||||

| Assisted reproduction pregnancy | p=0.44 | p=0.12 | p=0.77 | p=0.25 | p=0.15 | ||||||||||

| No | 216.10 | 271.69 | 623.72 | 1,098.43 | 88.25 | 186.58 | 4,580.71 | 6,615.44 | 238.72 | 173.25 | |||||

| Yes | 243.19 | 251.74 | 267.50 | 571.08 | 66.67 | 134.27 | 2,309.44 | 2,367.26 | 270.83 | 170.84 | |||||

| High-risk pregnancy consultation | p=0.36 | p=0.68 | p=0.37 | p=0.9 | p=0.42 | ||||||||||

| No | 217.13 | 268.96 | 585.37 | 1,043.02 | 98.13 | 208.48 | 4,378.80 | 6,292.21 | 231.08 | 159.00 | |||||

| Yes | 184.75 | 223.20 | 655.00 | 1,014.05 | 94.58 | 227.66 | 4,653.33 | 6,095.47 | 253.58 | 183.25 | |||||

| Trimester of pregnancy awareness | p=0.47 | p<0.01 | p=0.94 | p<0.01 | p=0.48 | ||||||||||

| First trimester | 212.09 | 262.55 | 569.92 | 1,020.82 | 97.49 | 211.10 | 4,273.58 | 6,154.53 | 235.24 | 163.21 | |||||

| Second trimester | 162.00 | 272.98 | 2,124.00 | 741.37 | 123.00 | 266.73 | 13,836.00 | 6,577.54 | 198.00 | 174.41 | |||||

| Professional health care during pregnancy | p=0.73 | p=0.62 | p=0.39 | p=0.93 | p=0.96 | ||||||||||

| No | 315.00 | 445.48 | 940.00 | 1,329.36 | 420.00 | 593.97 | 10,300.00 | 14,566.40 | 210.00 | 127.28 | |||||

| Yes | 211.53 | 261.92 | 594.50 | 1,037.71 | 95.88 | 208.33 | 4,390.92 | 6,212.02 | 234.74 | 163.28 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).