Submitted:

10 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Developing the Knowledge Retention Score (KRS)

3.1.1. Feature Similarity Calculation

3.1.2. Output Agreement Calculation

3.1.3. Combining Feature and Output Components

3.1.4. Interpreting the KRS

3.1.5. KRS for Image Segmentation Tasks

3.2. Experimental Setup

3.2.1. Dataset

3.2.2. Teacher-Student Model Pairs

3.2.3. Dataset-Model Pairing Strategy

3.2.4. Knowledge Distillation Techniques

3.3. Implementation Strategy

3.3.1. Image Augmentation

3.3.2. Training Process

3.3.3. Knowledge Distillation

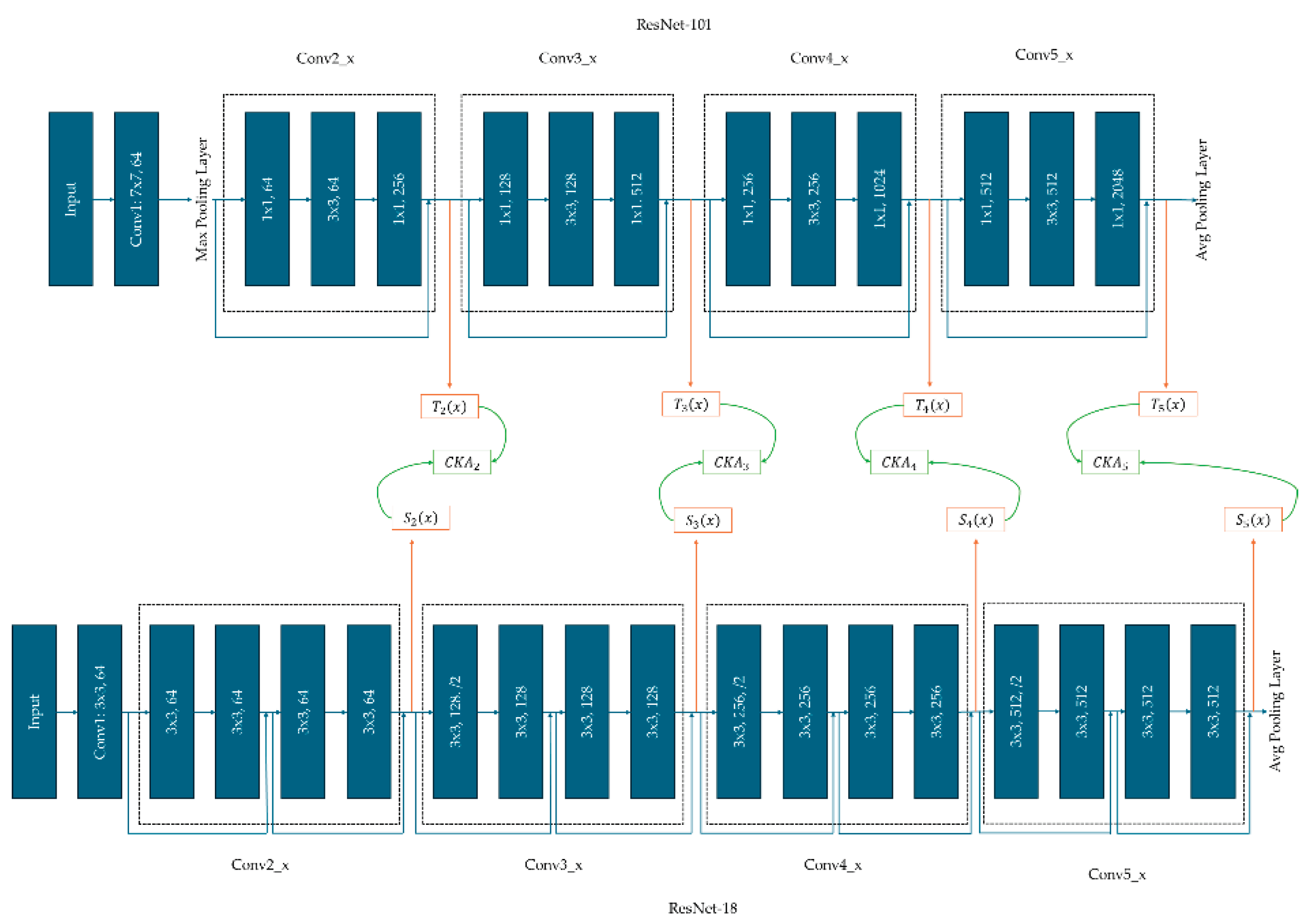

3.3.4. Evaluation of Student’s Performance Using KRS

4. Results and Discussion

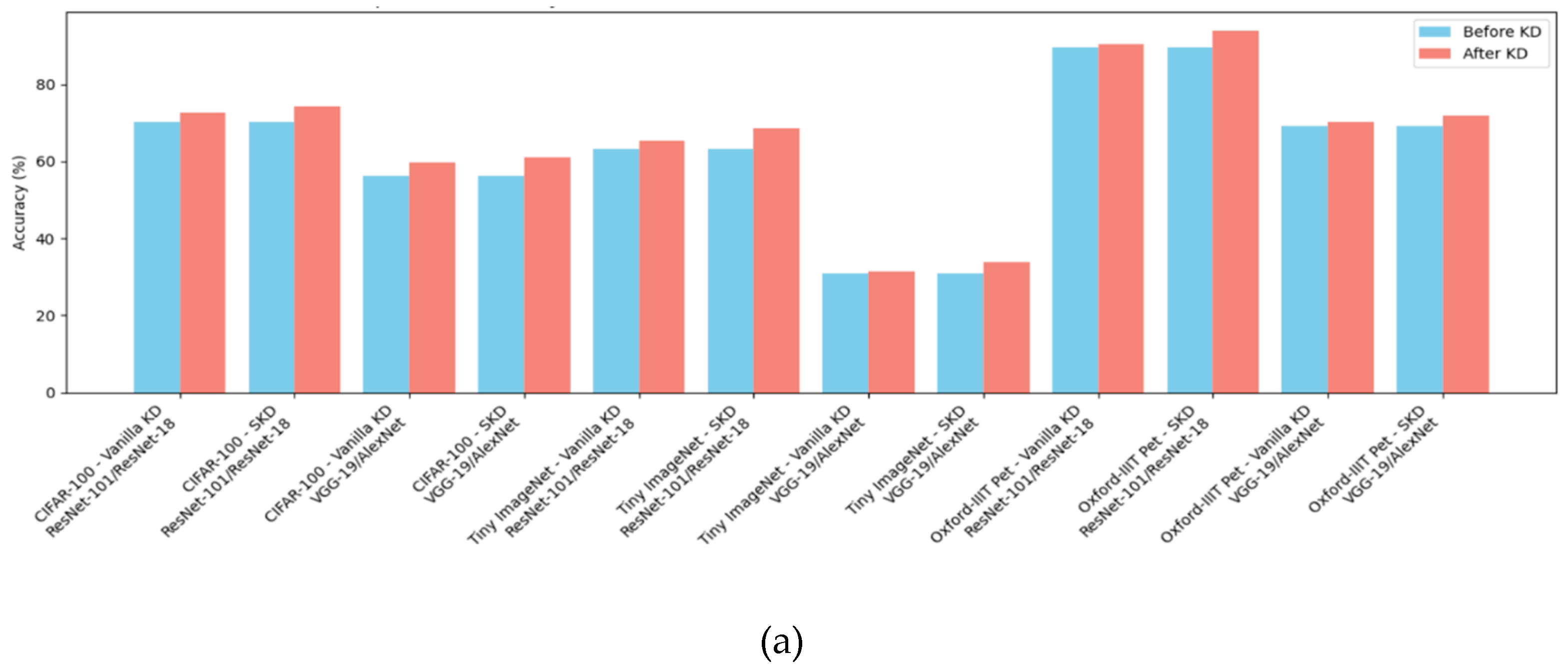

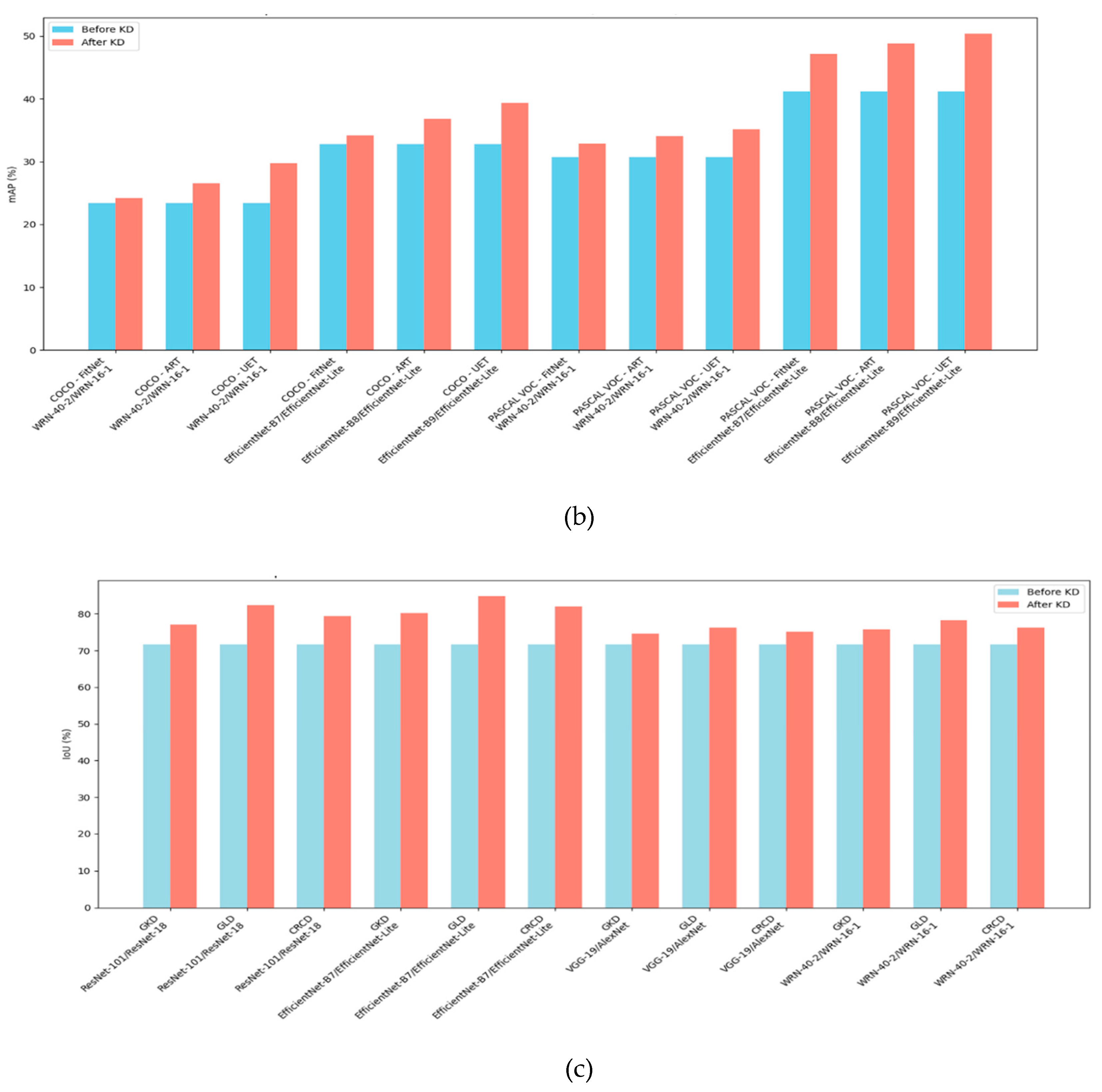

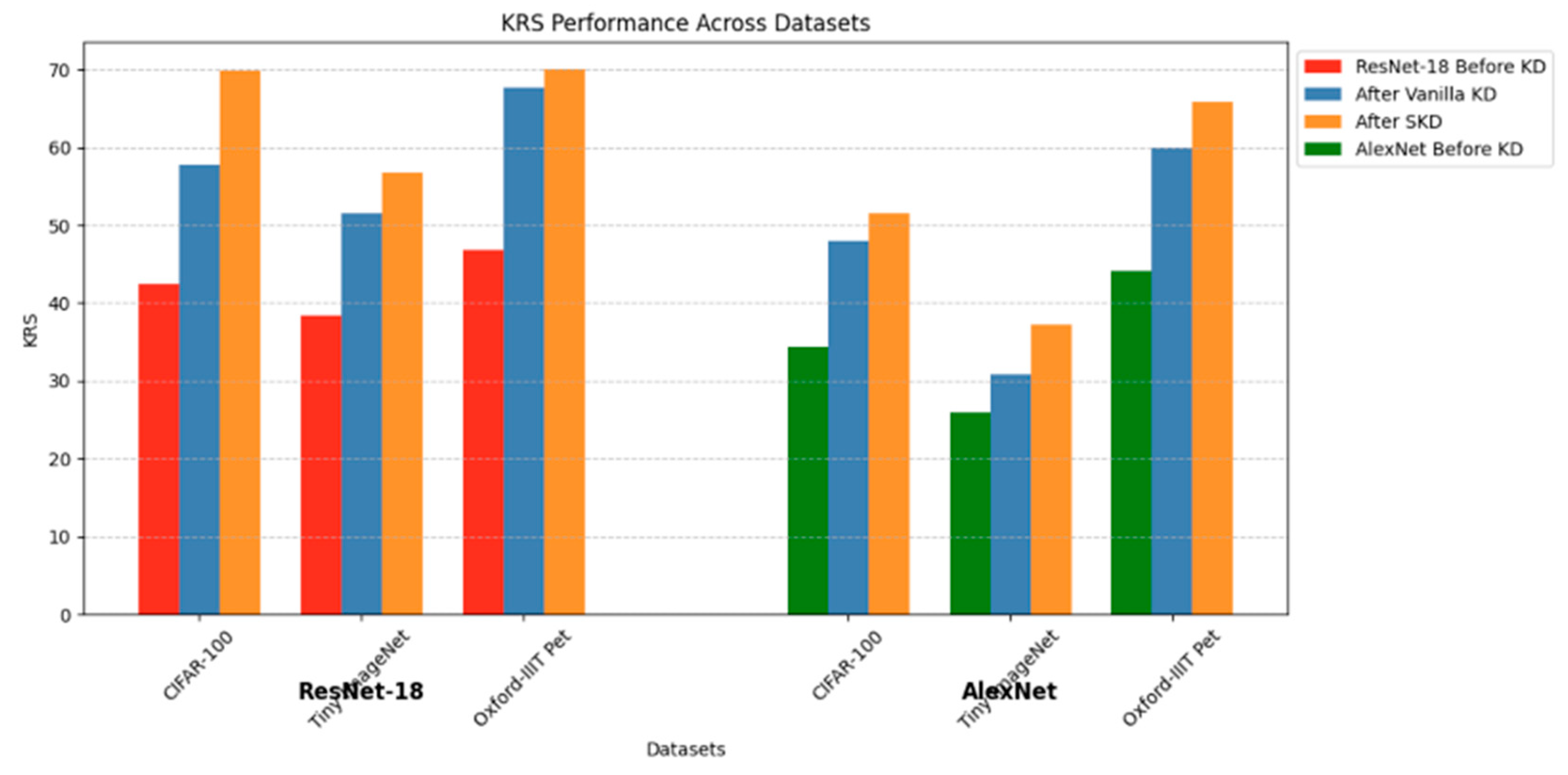

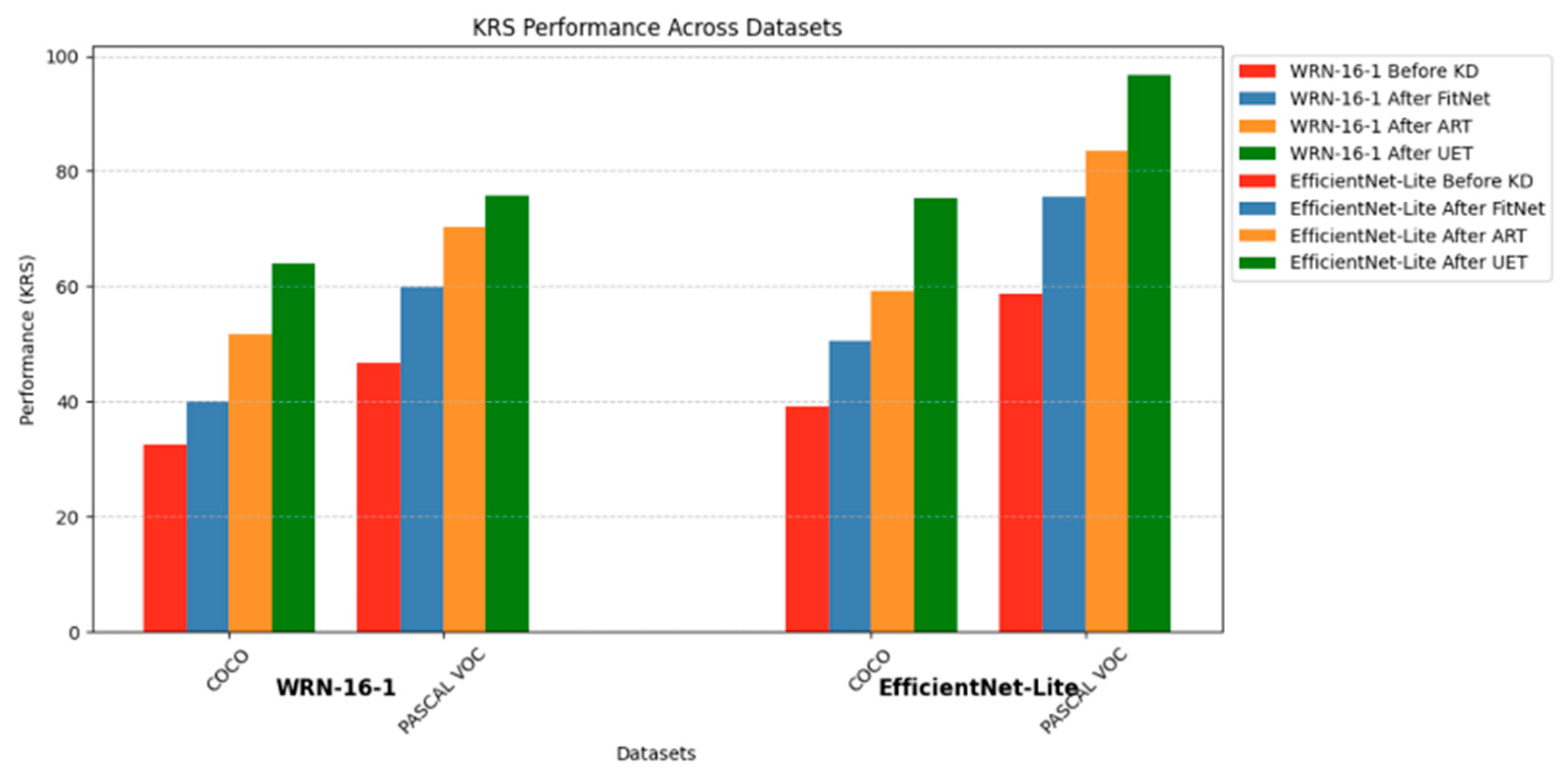

4.1. Performance Improvement Before and After KD

4.1.1. Analysis Using Conventional Performance Metrics

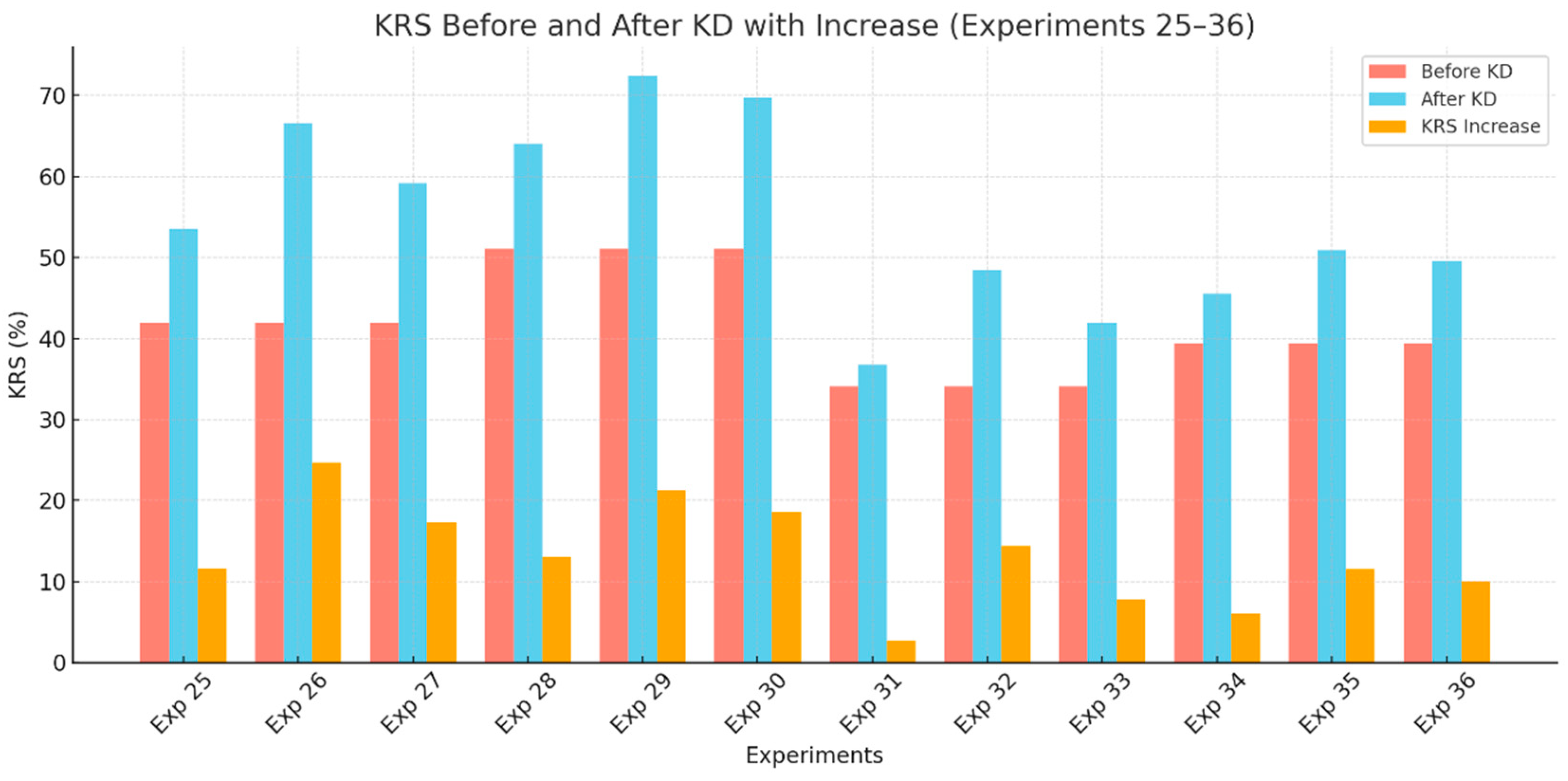

4.1.2. Student Model Performance Using KRS Before and After KD

4.2. Validation of the KRS Metric

4.2.1. Correlation Between KRS and Standard Performance Metrics

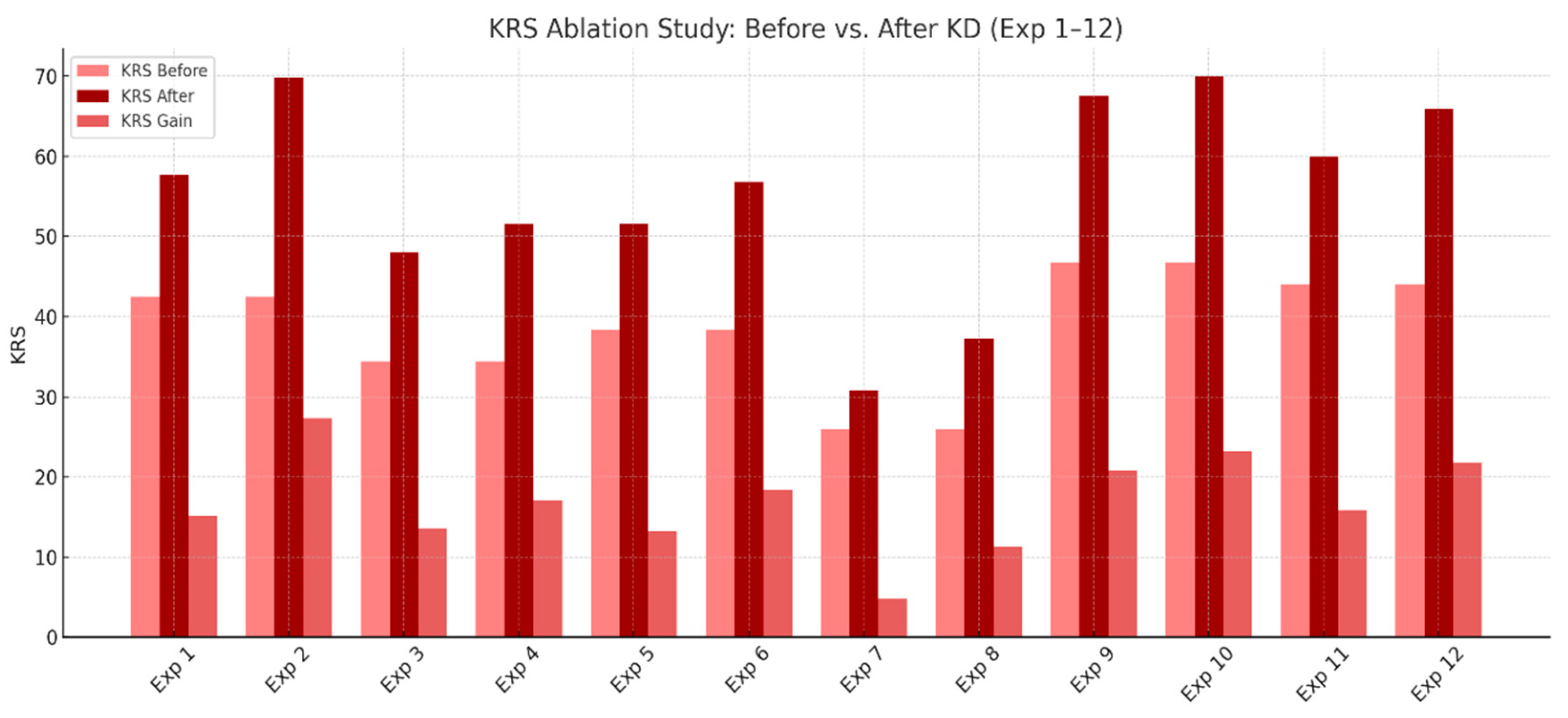

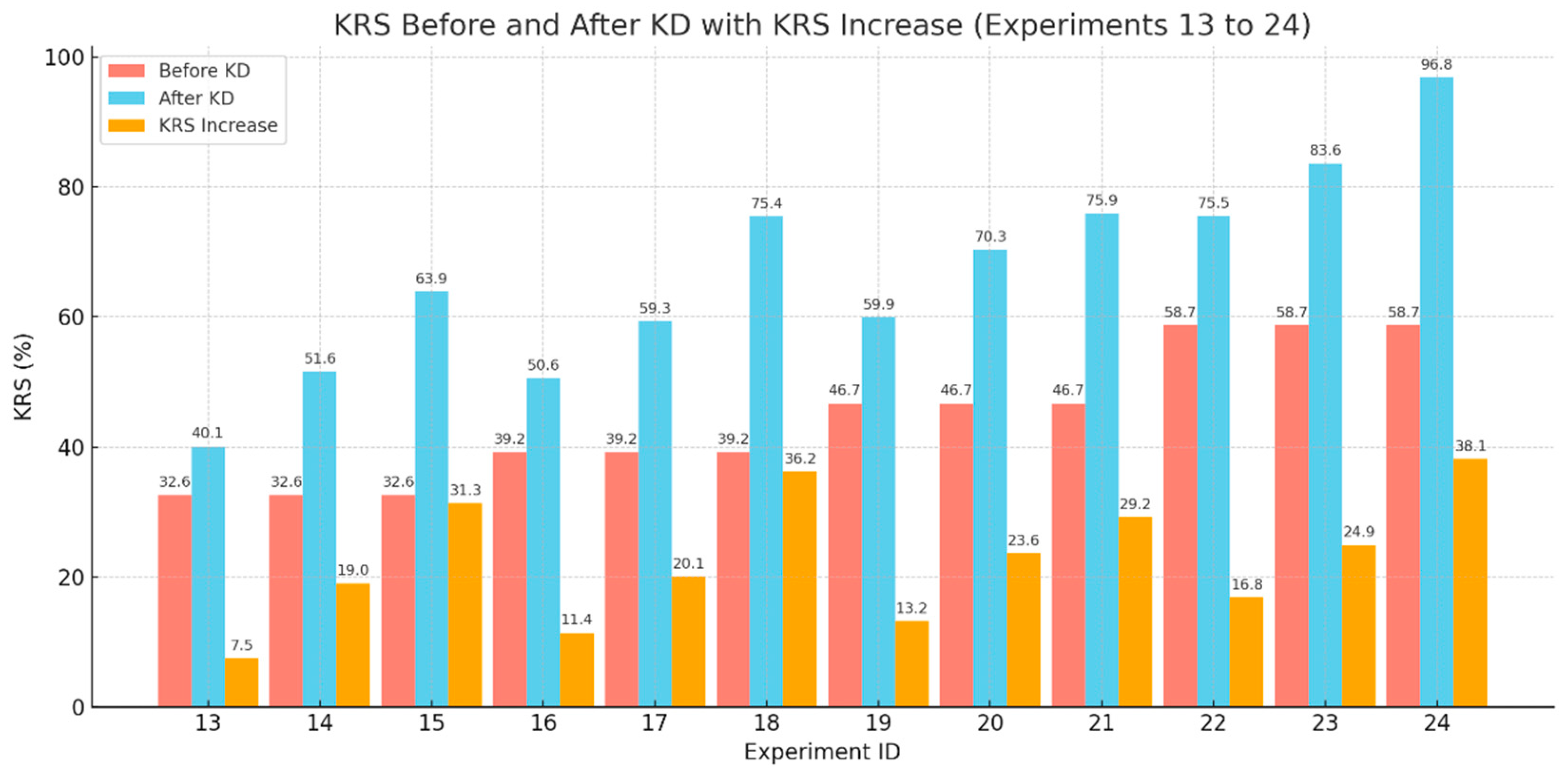

4.2.2. Ablation Study: Decomposing KRS Before and After KD

4.2.3. Sensitivity to KD Quality

4.2.4. Architectural Generalization

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rawat, W.; Wang, Z. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Image Classification: A Comprehensive Review. Neural Comput 2017, 29, 2352–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.Q.; Zheng, P.; Xu, S.T.; Wu, X. Object Detection with Deep Learning: A Review. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 2018, 30, 3212–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Georgiou, T.; Lew, M.S. A Review of Semantic Segmentation Using Deep Neural Networks. Int J Multimed Inf Retr 2018, 7, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otter, D.W.; Medina, J.R.; Kalita, J.K. A Survey of the Usages of Deep Learning for Natural Language Processing. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 2021, 32, 604–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Yu, B.; Maybank, S.J.; Tao, D. Knowledge Distillation: A Survey. Int J Comput Vis 2021, 129, 1789–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. 2015.

- Yang, C.; Yu, X.; An, Z.; Xu, Y. Categories of Response-Based, Feature-Based, and Relation-Based Knowledge Distillation. Advancements in Knowledge Distillation: Towards New Horizons of Intelligent Systems, Studies in Computational Intelligence 2023, 1100, 10–41. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, A.; Ballas, N.; Kahou, S.E.; Chassang, A.; Gatta, C.; Bengio, Y. FitNets: Hints for Thin Deep Nets. 2014.

- Alkhulaifi, A.; Alsahli, F.; Ahmad, I. Knowledge Distillation in Deep Learning and Its Applications. PeerJ Comput Sci 2021, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, G.; Reddy Mopuri, K.; Qiu, Q. Learning to Retain While Acquiring: Combating Distribution-Shift in Adversarial Data-Free Knowledge Distillation.

- Singh, P.; Mazumder, P.; Rai, P.; Namboodiri, V.P. Rectification-Based Knowledge Retention for Continual Learning.

- Hu, C.; Li, X.; Liu, D.; Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. Teacher-Student Architecture for Knowledge Distillation: A Survey. 2023.

- Ji, M.; Heo, B.; Park, S. Show, Attend and Distill:Knowledge Distillation via Attention-Based Feature Matching. 35th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI 2021 2021, 9B, 7945–7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.; Kim, D.; Lu, Y.; Cho, M. Relational Knowledge Distillation. Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2019, 2019-June, 3962–3971. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yoon, K.-J. Knowledge Distillation and Student-Teacher Learning for Visual Intelligence: A Review and New Outlooks.

- Zagoruyko, S.; Komodakis, N. Paying More Attention to Attention: Improving the Performance of Convolutional Neural Networks via Attention Transfer. 2016.

- Sun, T.; Chen, H.; Hu, G.; Zhao, C. Explainability-Based Knowledge Distillation. Pattern Recognit 2024, 111095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, J.; Wang, L.F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. KDE-GAN: A Multimodal Medical Image-Fusion Model Based on Knowledge Distillation and Explainable AI Modules. Comput Biol Med 2022, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franciscus, B.; Vosters, C.; Sebastian, J.; Jauregui, O.; Hendrix, P. Knowledge Distillation to Improve Model Performance and Explainability: A Decision-Critical Scenario Analysis. 2020.

- Ojha, U.; Li, Y.; Rajan, A.S.; Liang, Y.; Lee, Y.J. What Knowledge Gets Distilled in Knowledge Distillation? 2022.

- Park, S.; Kang, D.; Paik, J. Cosine Similarity-Guided Knowledge Distillation for Robust Object Detectors. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Oh, J.; Kim, N.Y.; Cho, S.; Yun, S.Y. Comparing Kullback-Leibler Divergence and Mean Squared Error Loss in Knowledge Distillation. IJCAI International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2021, 2628–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Bialkowski, A.; Khalifa, S. SAHA, BIALKOWSKI, KHALIFA: REPRESENTATION DISTILLATION USING CKA Distilling Representational Similarity Using Centered Kernel Alignment (CKA). 2022.

- Shrivastava, A.; Qi, Y.; Ordonez, V. Estimating and Maximizing Mutual Information for Knowledge Distillation.

- Lee, J.-W.; Choi, M.; Lee, J.; Shim, H. Collaborative Distillation for Top-N Recommendation.

- Alba, A.R.; Villaverde, J.F. PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT OF KNOWLEDGE DISTILLATION MODELS USING THE KNOWLEDGE RETENTION SCORE. In Proceedings of the IET Conference Proceedings; Institution of Engineering and Technology, 2024; Vol. 2024, pp. 372–379. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. European Conference on Computer Vision 2014, 8693 LNCS, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, M.; Eslami, S.M.A.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.K.I.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The Pascal Visual Object Classes Challenge: A Retrospective. Int J Comput Vis 2015, 111, 98–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Lang, B.; Quan, F. Student-Friendly Knowledge Distillation. Knowl Based Syst 2024, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Ham, G.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D. Ambiguity-Aware Robust Teacher (ART): Enhanced Self-Knowledge Distillation Framework with Pruned Teacher Network. Pattern Recognit 2023, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Mao, J.; Liu, T.; Li, M.; Gu, H.; Zhang, H.; Chang, X.; Wang, Y. Teaching with Uncertainty: Unleashing the Potential of Knowledge Distillation in Object Detection. 2024.

- Lee, S.; Song, B.C. Graph-Based Knowledge Distillation by Multi-Head Attention Network. 2019.

- Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Jang, Y.H.; Ali, M.; Oh, T.H.; Bae, S.H. Distilling Global and Local Logits with Densely Connected Relations. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2021, 6270–6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Tang, S.; Chen, D.; Yu, S.; Liu, Y.; Rong, M.; Yang, A.; Wang, X. Complementary Relation Contrastive Distillation. Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2021, 9256–9265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title 1 | Total Images | Training Set | Validation Set | Test Set | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIFAR-100 | 60,000 | 50,000 | 5,000 | 10,000 | |

| Tiny ImageNet | 120,000 | 100,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 | |

| COCO | 164,000 | 118,000 | 5,000 | 41,000 | |

| PASCAL VOC | 11,540 | 8,078 | 1,731 | 1,731 | |

| Oxford IIIT Pet | 7,349 | 5,239 | 1,105 | 1,105 |

| Teacher Model/Student Model | Compression Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ResNet-101/ResNet-18 | 73.71 | |

| VGG-19/AlexNet | 57.34 | |

| WRN-40-2/WRN-16-1 | 92.60 | |

| EfficientNet-B7/EfficientNet-Lite | 91.97 |

| Task | Dataset | Teacher/Student | KD Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image Classification | CIFAR-100 Tiny ImageNet Oxford-IIIT Pet |

ResNet-101/ResNet-18 VGG-19/AlexNet |

Vanilla KD [6], SKD [29] |

| Object Detection | COCO PASCAL VOC |

WRN-40-2/WRN-16-1 EfficientNet-B7/EfficientNet-Lite |

FitNet [8], ART [30], UET [31] |

| Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIIT Pet | ResNet-101/ResNet-18 EfficientNet-B7/EfficientNet-Lite VGG-19/AlexNet WRN-40-2/WRN-16-1 |

GKD [32], GLD [33], CRCD [34] |

| Teacher/Student | Layers to Capture from the Teacher | Layers to Capture from the Student |

|---|---|---|

| ResNet-101/ResNet-18 | Conv2_x, Conv3_x, Conv4_x, Conv5_x |

Conv2_x, Conv3_x, Conv4_x, Conv5_x |

| VGG-19/AlexNet | Conv1_2, Conv2_2, Conv3_4, Conv4_4, Conv5_4 | Conv1, Conv2, Conv3, Conv4, Conv5 |

| WRN-40-2/WRN-16-1 | Block 2, Block 3, Block 4 | Block 2, Block 3, Final Block |

| EfficientNet-B7/ EfficientNet-Lite |

MBConv2_1, MBConv3_3, MBConv4_5, | Corresponding MBConv blocks |

| ID No. | Task | Dataset | Teacher Network | Student Network | KD Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Image Classification | CIFAR-100 | ResNet-101 | ResNet-18 | Vanilla KD |

| 2 | Image Classification | CIFAR-100 | ResNet-101 | ResNet-18 | SKD |

| 3 | Image Classification | CIFAR-100 | VGG-19 | AlexNet | Vanilla KD |

| 4 | Image Classification | CIFAR-100 | VGG-19 | AlexNet | SKD |

| 5 | Image Classification | Tiny ImageNet | ResNet-101 | ResNet-18 | Vanilla KD |

| 6 | Image Classification | Tiny ImageNet | ResNet-101 | ResNet-18 | SKD |

| 7 | Image Classification | Tiny ImageNet | VGG-19 | AlexNet | Vanilla KD |

| 8 | Image Classification | Tiny ImageNet | VGG-19 | AlexNet | SKD |

| 9 | Image Classification | Oxford-IIT Pet | ResNet-101 | ResNet-18 | Vanilla KD |

| 10 | Image Classification | Oxford-IIT Pet | ResNet-101 | ResNet-18 | SKD |

| 11 | Image Classification | Oxford-IIT Pet | VGG-19 | AlexNet | Vanilla KD |

| 12 | Image Classification | Oxford-IIT Pet | VGG-19 | AlexNet | SKD |

| 13 | Object Detection | COCO | WRN-40-2 | WRN-16-1 | FitNet |

| 14 | Object Detection | COCO | WRN-40-2 | WRN-16-1 | ART |

| 15 | Object Detection | COCO | WRN-40-2 | WRN-16-1 | UET |

| 16 | Object Detection | COCO | EfficientNet-B7 | EfficientNet-Lite | FitNet |

| 17 | Object Detection | COCO | EfficientNet-B8 | EfficientNet-Lite | ART |

| 18 | Object Detection | COCO | EfficientNet-B9 | EfficientNet-Lite | UET |

| 19 | Object Detection | PASCAL VOC | WRN-40-2 | WRN-16-1 | FitNet |

| 20 | Object Detection | PASCAL VOC | WRN-40-2 | WRN-16-1 | ART |

| 21 | Object Detection | PASCAL VOC | WRN-40-2 | WRN-16-1 | UET |

| 22 | Object Detection | PASCAL VOC | EfficientNet-B7 | EfficientNet-Lite | FitNet |

| 23 | Object Detection | PASCAL VOC | EfficientNet-B8 | EfficientNet-Lite | ART |

| 24 | Object Detection | PASCAL VOC | EfficientNet-B9 | EfficientNet-Lite | UET |

| 25 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | ResNet-101 | ResNet-18 | GKD |

| 26 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | ResNet-101 | ResNet-18 | GLD |

| 27 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | ResNet-101 | ResNet-18 | CRCD |

| 28 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | EfficientNet-B7 | EfficientNet-Lite | GKD |

| 29 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | EfficientNet-B7 | EfficientNet-Lite | GLD |

| 30 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | EfficientNet-B7 | EfficientNet-Lite | CRCD |

| 31 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | VGG-19 | AlexNet | GKD |

| 32 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | VGG-19 | AlexNet | GLD |

| 33 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | VGG-19 | AlexNet | CRCD |

| 34 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | WRN-40-2 | WRN-16-1 | GKD |

| 35 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | WRN-40-2 | WRN-16-1 | GLD |

| 36 | Image Segmentation | Oxford-IIT Pet | WRN-40-2 | WRN-16-1 | CRCD |

| Lowest to Highest Ranking of KD Methods by Conventional Metrics Gain | Lowest to Highest KRS Gainers |

|---|---|

| Vanilla KD | Vanilla KD |

| FitNet | FitNet |

| GKD | GKD |

| CRCD | CRCD |

| ART | ART |

| GLD | GLD |

| UET | UET |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).