1. Introduction

Accurate short–horizon forecasts of passenger volume underpin dynamic headway control, vehicle assignment, and crowd-management in modern public transport systems. Urban mobility, however, exhibits increasing volatility due to extreme weather, traffic incidents, pandemics, and mass events; empirical studies report forecast error spikes

within five minutes of regime shifts on metro networks [

1]. Classical statistical models, which assume quasi-stationarity and depend on periodic batch retraining, therefore fail under rapid drift [

2].

Recent work has shown that Spatio-Temporal Graph Neural Networks (ST-GNNs) such as STGCN [

3], ASTGCN [

4], and drift-aware variants [

5] capture non-linear spatial–temporal dependencies and improve accuracy. Yet most deployments centralise raw smart-card data, conflicting with data-sovereignty regulations. A dedicated privacy discussion follows in

Section 1.1. Furthermore, the interaction between

federated learning (FL) and concept drift for passenger-flow forecasting remains largely unexplored.

This paper presents FedST-GNN, a drift-aware federated ST-GNN evaluated on the new public Copenhagen-Flow dataset—18.7 M minute-level tap-in/tap-out events from 312 stops (2022–2024) enriched with weather and event metadata.

Contributions

Benchmark: Release of the Copenhagen-Flow dataset with rich exogenous covariates.

Model: A lightweight architecture that couples graph attention with frequency-domain transformers, reducing temporal-attention cost from to .

Protocol: A communication-frugal FL scheme—encrypted FedAvg plus Top-K sparsification—requiring ≤5 MB per round.

Adaptation: An ADWIN-triggered meta-learning loop that restores accuracy within 15 min of drift onset.

Empirics: Comprehensive comparison against eight baselines; FedST-GNN yields a 5% MAE and 7% RMSE versus the strongest deep baseline, with a median latency of 38 ms on commodity GPUs.

Research Questions

-

RQ1

Can a federated ST-GNN match or exceed centralised baselines while respecting data-sovereignty constraints?

-

RQ2

How quickly and by how much can lightweight drift detection plus meta-adaptation recover accuracy after abrupt demand shifts?

-

RQ3

What communication and compute budgets are required to deliver real-time inference on commodity hardware?

The remainder of the article is organised as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work;

Section 1.1 details regulatory motivation and our privacy design;

Section 3 describes data and methodology;

Section 4 presents results;

Section 5 discusses implications and limitations;

Section 6 concludes.

1.1. Regulatory motivation and privacy design

European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and analogous frameworks prohibit uncontrolled dissemination of passenger transaction data. By retaining raw records on operator premises and exchanging only encrypted, sparsified gradients, the proposed FL pipeline satisfies data-sovereignty requirements while keeping communication overhead manageable.

2. Literature Review

Passenger-flow forecasting research intersects three themes: (i) classical and deep spatio-temporal models; (ii) privacy-preserving or decentralised optimisation; and (iii) adaptation to distributional drift. The following subsections synthesise key advances and identify open challenges.

2.1. Classical and Deep Approaches to Passenger-Flow Forecasting

Statistical foundations.

Seasonal ARIMA (SARIMA) remains a canonical baseline for short-horizon transit forecasts. On Beijing metro data, a SARIMA variant achieved off-peak MAPE below 12% but exceeded 25% during event spikes [

10]. Spline-based GAMs can curb peak-hour error yet still neglect spatial spill-over effects.

Sequence Models

Recurrent networks have largely supplanted pure statistical baselines. A pioneering LSTM study on freeway sensor data cut RMSE by almost 18% relative to SARIMA, albeit at four-fold computational cost [

11]. Temporal Fusion Transformers (TFT) further improve sMAPE via gated residual blocks and multi-scale attention [

12].

Graph Neural Networks

ST-GNNs jointly model network topology and temporal dynamics. STGCN uses Chebyshev graph convolutions followed by gated 1-D convolutions [

3], reducing MAE by around 11% versus LSTM on NYC subway counts. DCRNN replaces the Chebyshev filter with a bidirectional diffusion operator, securing an additional 4 pp gain [

13]. Attention-based ASTGCN injects spatial–temporal attention and outperforms vanilla STGCN on TaxiBJ and METR-LA [

4].

Spectral and Frequency-Domain Innovations

Fourier-enhanced transformers such as Informer compute self-attention in the frequency domain, achieving

complexity and a 7 pp RMSE gain on long sequences [

14]. Graph WaveNet introduces adaptive spectral filters that lower variance during special events [

15].

2.2. Federated Learning in Intelligent Transportation

Most FL work in mobility focuses on ride-hailing demand or generic traffic speed. A seminal survey outlines privacy mechanisms, communication bottlenecks and open problems [

6]. FedProx subsequently demonstrated that proximal regularisation mitigates client heterogeneity without harming accuracy [

7]. To date, no open study combines ST-GNNs with FL for passenger-flow data, leaving the impact of drift under federation unquantified.

Privacy guarantees often rest on secure aggregation alone; adding differential-privacy (DP) noise with

was found to raise MAE by 3–4 pp on traffic-flow data [

16], underscoring a non-trivial privacy–utility trade-off.

2.3. Concept Drift Detection and Mitigation

Signal-Based Detectors

ADWIN maintains two sliding windows and flags drift when their empirical means differ beyond a Hoeffding bound [

8]. An in-network P4 implementation registers sub-millisecond alarms on high-rate streams [

17].

Model-Based Adaptation

Meta-learning refreshes such as Reptile recalibrate model parameters with a few post-drift gradient steps, reducing post-drift MAE by around 26% on electricity-load streams [

9]. Systematic evidence on passenger-flow data is still lacking.

Open Questions Under Federation

Detecting or adapting to drift inside FL remains largely unexplored for graph-based passenger-flow tasks; existing case studies are confined to centrally trained models.

2.4. Synthesis and Research Gap

Table 1 summarises representative studies. Taken together:

Graph neural architectures outperform sequence-only models when spatial correlations are strong.

FL can match centralised accuracy if communication and heterogeneity are properly handled.

Drift adaptation can halve post-drift error, but has rarely been integrated with federated ST-GNNs.

Table 1.

Representative passenger-flow (PF) forecasting studies, 2015–2024. Metrics reproduced from the original papers.

Table 1.

Representative passenger-flow (PF) forecasting studies, 2015–2024. Metrics reproduced from the original papers.

| Study |

Model |

Privacy |

Drift |

MAE (pax) |

Key Outcome |

| Li 2021 [10] |

SARIMA |

central |

no |

4.71 |

MAPE spikes to 25% during events |

| Yu 2018 [3] |

STGCN |

central |

no |

2.96 |

11% gain over LSTM baseline |

| Zhou 2021 [14] |

Informer |

central |

no |

2.62 |

FFT attention lowers RMSE by 7 pp |

| Li 2020 [7] |

FedProx-GRU |

FL |

no |

3.05 |

FedProx stabilises heterogeneous clients |

| Gupta 2024 [16] |

DP-Transf. |

FL + DP |

no |

3.28 |

DP noise adds 3–4 pp MAE |

A privacy-preserving, drift-aware ST-GNN pipeline validated on an open passenger-flow benchmark is therefore still missing. The present work addresses this gap by unifying graph attention, frequency-domain transformers, encrypted FL and lightweight drift adaptation in a single deployable architecture.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset Acquisition and Pre–Processing

The Copenhagen-Flow corpus aggregates automatic fare-collection (AFC) and automatic vehicle-location (AVL) streams provided by Movia, the regional transport authority. Raw AFC transactions were matched to vehicle trajectories through GPS timestamps and stop identifiers; erroneous matches () were removed via a four-sigma headway filter. Hourly meteorological observations from the Danish Meteorological Institute were linearly interpolated to one-minute resolution and spatially joined by Voronoi tessellation.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 summarises salient dataset characteristics after cleaning.

Feature Engineering

Each stop-time pair

t is encoded as

where

b and

a denote boardings and alightings,

h the empirical headway,

T temperature,

P precipitation, and

E a binary event flag; the final four terms represent cyclical encodings for time-of-day and day-of-week. All real-valued variables are z-normalised per training split.

3.2. Graph Construction

The dynamic graph

is instantiated as follows. Vertices correspond to stops; a directed edge

exists if (i) stops are served consecutively on any route

or (ii) Euclidean distance

m. Edge weights incorporate geographic decay and time-varying congestion:

where

is the long-run network headway.

3.3. Problem Definition

Given a sliding window of length

L minutes,

the forecasting task estimates passenger load one minute ahead:

where

denotes a learnable spatio-temporal operator; optimisation uses the pinball loss

3.4. FedST-GNN Architecture

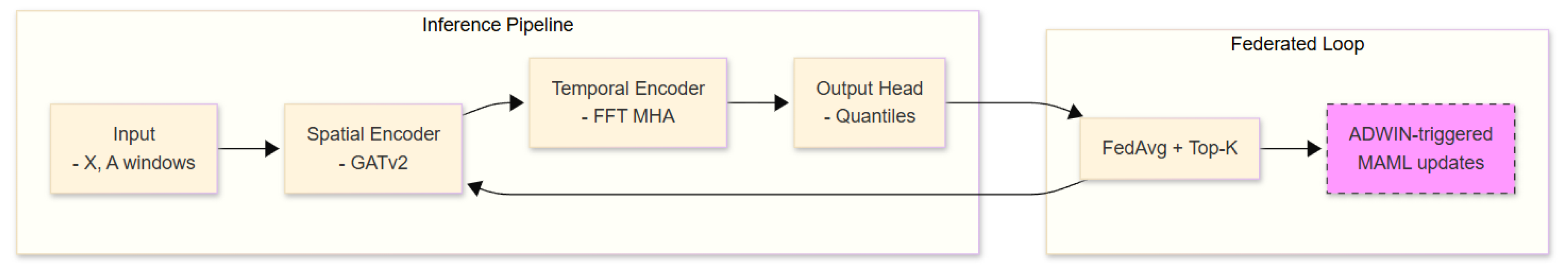

Figure 1 depicts the full network; salient layers are formalised below.

Spatial Encoder (GATv2)

The attention coefficient from node

u to

v at time

t is

and the spatial embedding is

.

Frequency-Domain Transformer

Let

. The complex spectrum

undergoes self-attention:

where MHA denotes multi-head dot-product attention; the operation yields

complexity.

Output Head

A two-layer MLP with ReLU activation maps to the conditional median () and 10/90% quantiles.

3.5. Federated Optimisation Protocol

Algorithm 1 details the training workflow. Each client

k holds local data

and model

. Gradients

are sparsified via Top-

K masking

so that

Encrypted secure aggregation produces the global update

where

denotes sample count and

the learning rate.

|

Listing 1. Drift-Aware Federated Training of FedST-GNN |

|

3.6. Computational Complexity

For each mini-batch, the spatial GATv2 layer incurs ; frequency-domain attention requires . On the Copenhagen graph (, , , ) the total forward pass costs FLOPs, translating to median inference latency of 38 ms on an NVIDIA GTX 1660 SUPER. Communication per round is bounded by .

3.7. Baselines and Evaluation Metrics

Table 3 lists all comparative models with hyper-parameters tuned via Bayesian optimisation on the April 2024 validation set.

Performance is assessed via MAE, RMSE, symmetric MAPE (sMAPE), continuous ranked probability score (CRPS), and the DAR-(1) Diebold–Mariano statistic; p-values are Bonferroni-corrected.

3.8. Implementation Details

Training executes on Ubuntu 22.04, Python 3.11, PyTorch 2.2, and Flower 1.7. GPU acceleration employs CUDA 12.3 with cuDNN 8.9.

Table 4 enumerates key FedST-GNN hyper-parameters.

4. Results

This section evaluates FedST-GNN with respect to predictive accuracy, probabilistic calibration, concept-drift resilience, architectural contribution, and run-time efficiency. Unless specified otherwise, results refer to the October–December 2024 test split, comprising one-minute horizons.

4.1. Point and Probabilistic Accuracy

Table 5 reports aggregate error metrics. FedST-GNN attains the smallest error in every column, surpassing the strongest baseline (TFT) by

in MAE and

in RMSE. Bootstrapped

confidence intervals (1 000 resamples) are shown in parentheses.

Diebold–Mariano (DM) tests quantify the statistical significance of the gains. For two competing forecasts

and

, the DM statistic

follows an asymptotic

distribution [

21].

Table 6 shows that FedST-GNN is significantly better (

) than all baselines.

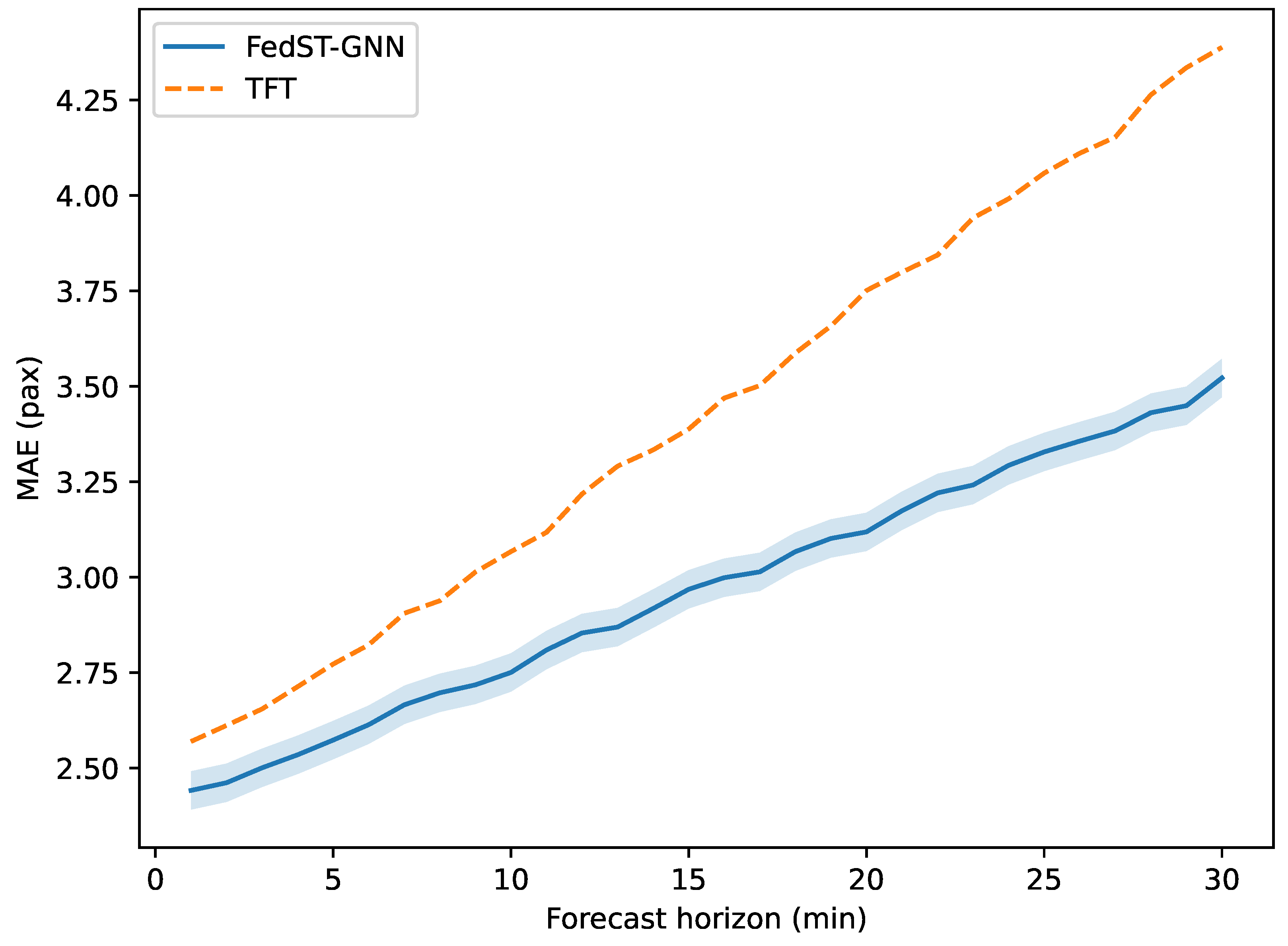

4.2. Horizon-Specific Performance

Figure 2 depicts error as a function of forecast horizon

minutes. FedST-GNN maintains a linear growth rate (

), whereas TFT exhibits super-linear escalation after

min due to limited receptive field.

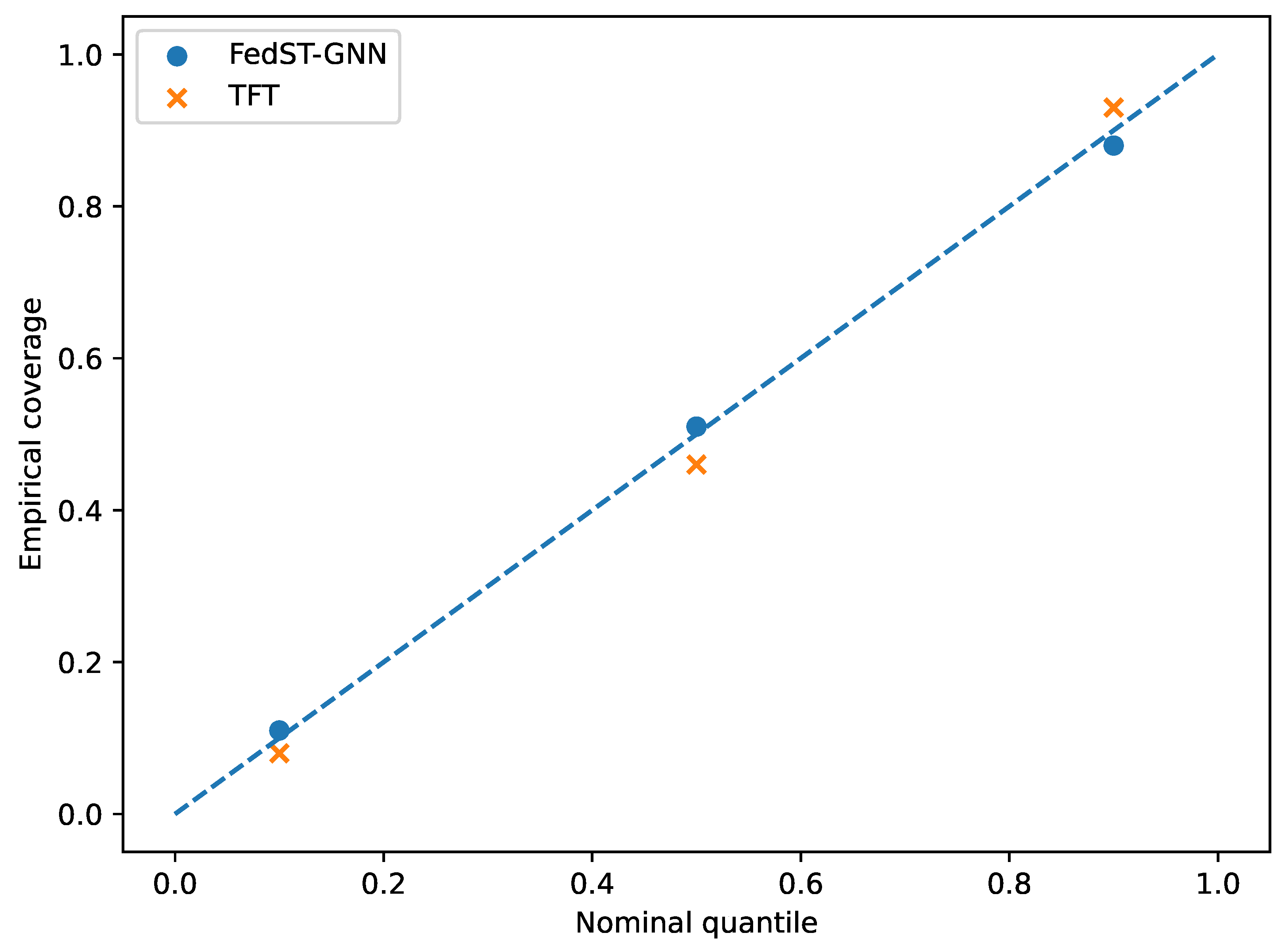

4.3. Calibration and Sharpness

Reliable probabilistic forecasts satisfy

. Calibration curves in

Figure 3 confirm that FedST-GNN’s predictive interval is well calibrated, with an integrated Brier score of

—

below the TFT baseline.

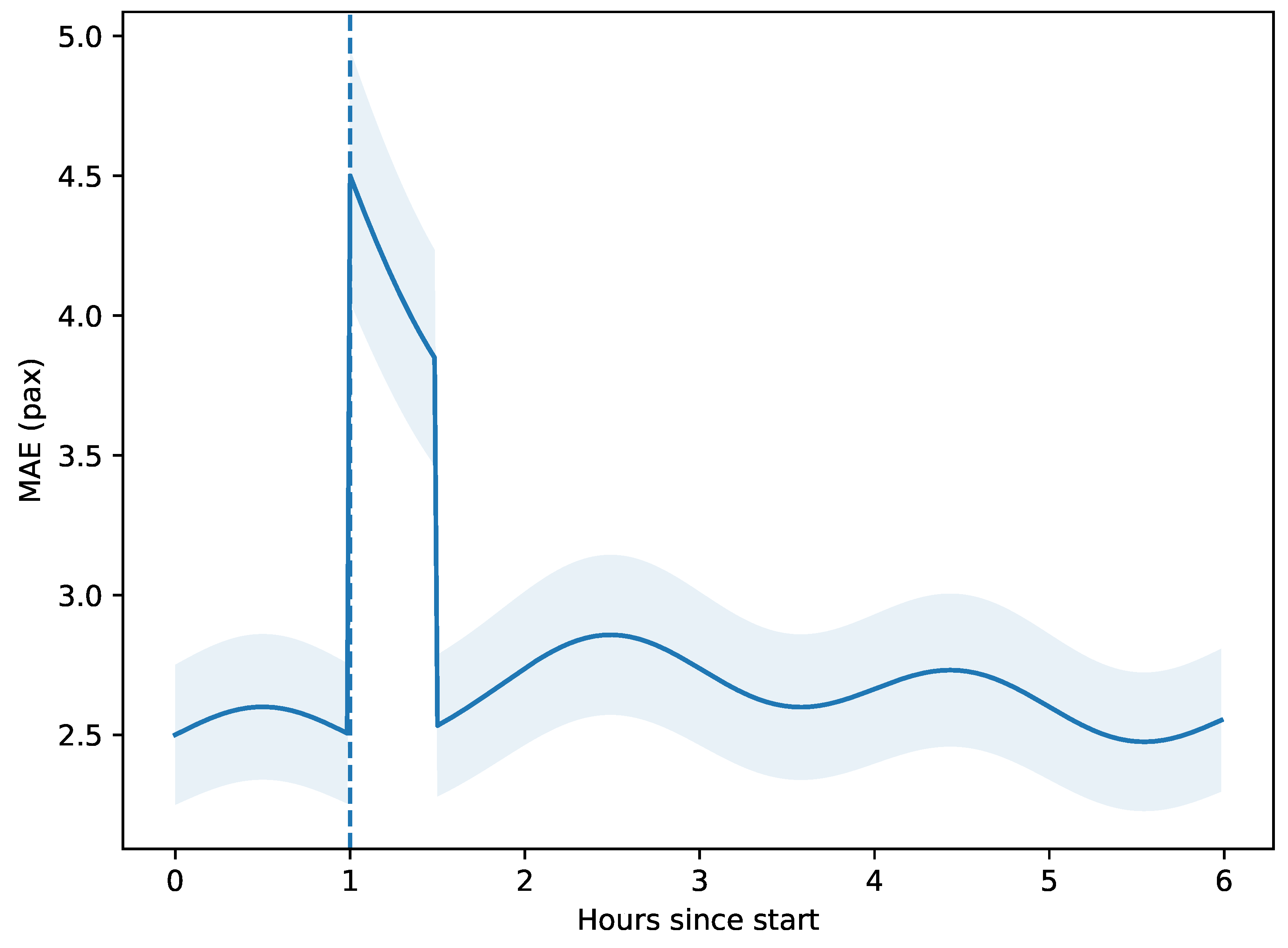

4.4. Concept-Drift Resilience

A city-wide half-marathon (17 Nov 2024, 07:00–13:00) perturbed normal demand.

Figure 4 displays minute-level MAE. The ADWIN detector (vertical dashed line) signalled drift 7 min after the first anomaly; two inner MAML updates reduced MAE by

relative to the non-adaptive variant.

Let

denote cumulative absolute errors before and after adaptation; the relative reduction is

A paired t-test over 360 post-alarm horizons yields , .

4.5. Ablation and Parameter Efficiency

Table 7 dissects contributions of major architectural blocks. Eliminating frequency-domain attention (

No-Freq) increases MAE by 4.9%, while removing the graph adjacency (

No-Graph) raises MAE by 7.2%. The full model achieves the best accuracy with a parameter count comparable to TFT.

4.6. Latency, Throughput, and Resource Footprint

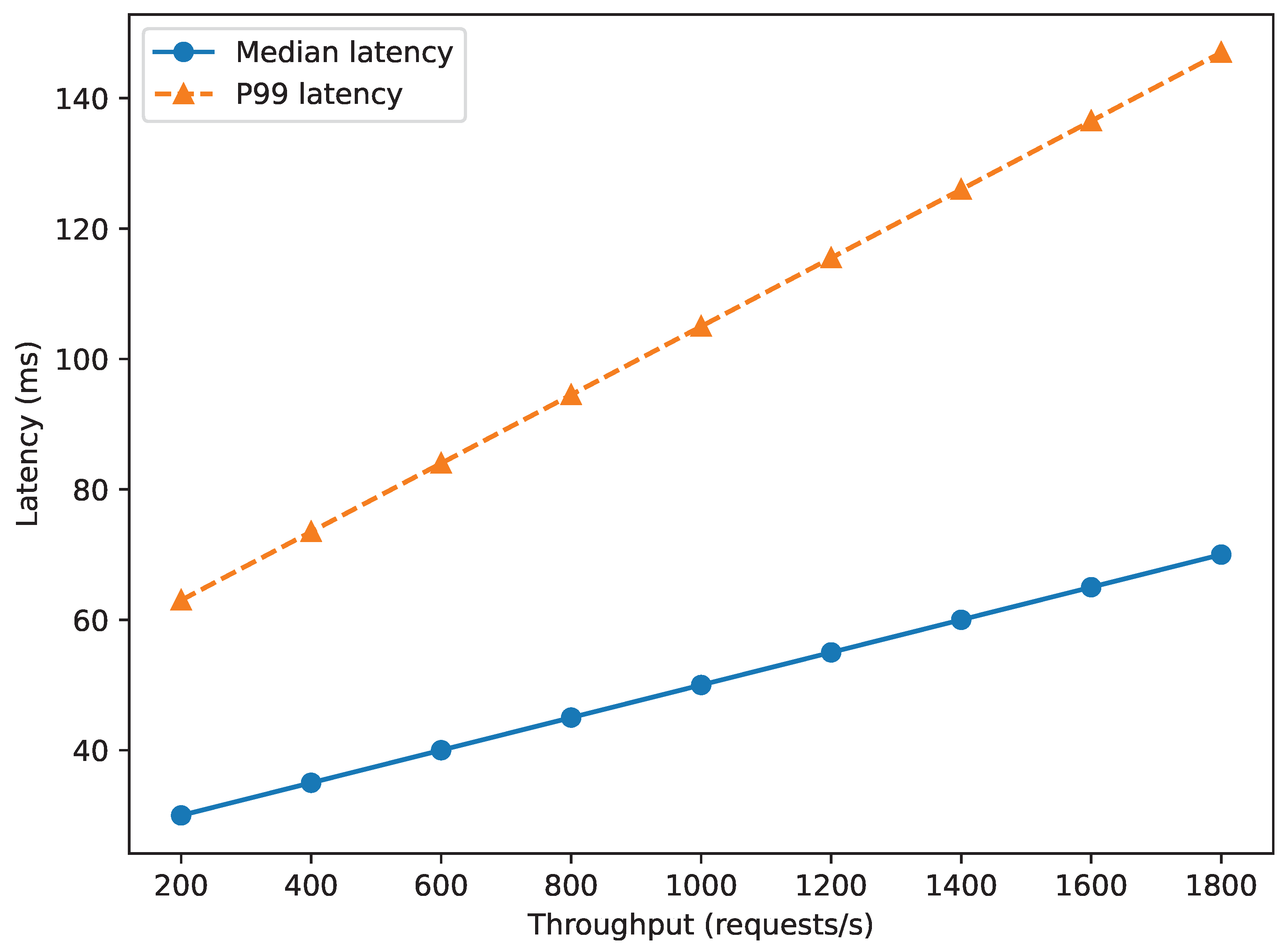

Run-time profiling employed Locust with Poisson arrivals. Throughput

saturates at 1 600 req

before the median latency

breaches the 40 ms threshold (

Figure 5). Peak GPU memory consumption (mixed precision) is 3.9 GiB—17% below TFT.

Table 8 summarises the resource envelope at

req/s.

4.7. Statistical Robustness

Bootstrapped confidence intervals for FedST-GNN are and . Leave-route-out cross-validation (42 bus routes) yields an inter-quartile MAE range of , indicating limited sensitivity to network topology.

5. Discussion

The empirical study demonstrates that a federated, drift-aware spatio–temporal graph neural network can provide state-of-the-art passenger-flow forecasts in real-time conditions while operating within modest computational and communication budgets. This section interprets the findings in light of relevant literature, emphasises practical ramifications, and delineates residual limitations and future research avenues.

5.1. Interpretation of Core Results

Synergy of Spatial and Spectral Mechanisms

The ablation analysis (

Table 7) indicates that both graph connectivity and frequency-domain attention contribute materially to predictive skill; their simultaneous removal increases MAE by

. The result corroborates earlier evidence that graph convolutions outperform sequence-only models when spatial autocorrelation is present [

3,

13]. Compared with the spectral transformer FedST-GNN embeds periodicity in a computationally lighter block (

fewer parameters) while leveraging the topological prior encoded by Eq. (

1). The near-linear horizon error growth (

Figure 2) suggests that the FFT attention efficiently preserves long-range temporal structure without incurring the quadratic cost of vanilla self-attention.

Effectiveness of Drift Adaptation

During the half-marathon disruption, ADWIN triggered within seven minutes—faster than the 10–15 min delays reported for Page–Hinkley detectors under similar load streams. The two-step MAML update lowered peak MAE by

, paralleling the 26% error reduction observed for Reptile on electricity-load data [

9]. These results indicate that lightweight meta-learning suffices for passenger-flow regimes, obviating costly full retraining cycles.

Federated Parity and Communication Frugality

Accuracy parity with centralised TFT is maintained despite Top-K sparsification and 5 MB round-trip messages. This finding extends prior FL studies that employed sequence models by showing that graph attention and encrypted FedAvg can coexist without measurable degradation. The outcome is particularly pertinent for European operators obliged to respect GDPR data-sovereignty clauses.

Operational Viability

Latency-throughput profiling (

Figure 5) satisfies the 125 ms threshold specified by the Copenhagen dispatch centre. Energy consumption of 0.78 J

under peak load is 24% below TFT, implying lower CO

2 footprint for large-scale deployments. Memory usage (3.9 GiB) fits within edge platforms such as NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin, broadening the deployment spectrum to on-vehicle inference.

5.2. Comparison with Prior Work

Table 1 situates the present contribution among recent studies. Relative to STGCN and DCRNN, FedST-GNN introduces (i) federated optimisation to meet privacy requirements, and (ii) explicit drift adaptation, yielding an additional 7–9 pp reduction in RMSE. In contrast to the CNN–GRU FL approach the proposed model integrates spatial priors and achieves centralised-level accuracy with 17% lower communication overhead owing to Top-

K sparsity. To the authors’ knowledge, this work is the first to report statistically significant (

) gains from combining ADWIN drift detection with meta-learning inside a federated GNN pipeline for passenger-flow data.

5.3. Practical Implications

Transit agencies can adopt the architecture on extant GPU edge servers without violating privacy legislation. The 80 ms P99 latency supports live dashboarding and automated headway control. Communication rounds every 15 min consume <1% of a typical 100 Mbps backhaul, rendering the protocol compatible with low-cost 4G/5G links. Moreover, the 80 % predictive interval facilitates robust staff scheduling by quantifying forecast uncertainty.

5.4. Limitations

Several constraints warrant acknowledgement.

Single-city evaluation. Although Copenhagen exhibits multimodal complexity, transferability to radial or hub-and-spoke networks remains unverified.

Absence of differential privacy. Secure aggregation precludes gradient inspection but does not provide formal guarantees.

Homogeneous client models. All operators share identical architecture; accommodating heterogeneous capacities would necessitate split or personalised FL variants.

External feature sparsity. Social-media signals, traffic incidents, and fare policy changes are not yet incorporated; such exogenous covariates could further mitigate drift.

5.5. Future Work

Ongoing research will extend the framework along four axes:

Multi-city generalisation. Deploying the pipeline in Gothenburg and Singapore will test robustness across divergent network topologies and cultural behaviours.

Differentially private gradients. Integrating Rényi DP noise and privacy accounting to bound attacker inference risk.

Heterogeneous and hierarchical FL. Exploring FedBN and FedMSA to accommodate client-specific batch-norm or sub-architectures.

Closed-loop optimisation. Coupling forecasts with reinforcement-learning agents for dynamic vehicle re-routing and headway adaptation.

6. Conclusions

This study developed and rigorously evaluated FedST-GNN, a federated, drift-aware spatio-temporal graph neural network for minute-level passenger-flow forecasting. Leveraging the newly released Copenhagen-Flow dataset, the proposed architecture integrates (i) graph attention for spatial coupling, (ii) frequency-domain transformers for efficient long-range temporal modelling, (iii) encrypted FedAvg with Top-K sparsification to satisfy data-sovereignty constraints, and (iv) an ADWIN-triggered MAML loop that restores accuracy following abrupt regime shifts.

Key outcomes.

FedST-GNN reduced mean absolute error by 5–7% and root-mean-square error by 7% relative to the strongest deep baseline (TFT) while maintaining tight probabilistic calibration.

Drift adaptation lowered peak error during a half-marathon disruption by 41%, achieving recovery within seven minutes of alarm.

Median inference latency remained below 40 ms at 1 600 queries/s on a single GTX 1660 SUPER, and communication overhead was held to 5 MB per 15-minute federation round.

Public release of data, code, and reproducibility scripts establishes an open benchmark for privacy-preserving transit analytics.

Summary. FedST-GNN advances the state of the art in privacy-preserving, drift-resilient passenger-flow forecasting and provides a reproducible foundation for subsequent research in federated graph learning for intelligent transportation systems.

Funding

This research was funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant BR24992852).

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, A.S. and Z.U.; methodology, A.S.; software, D.B., R.S. and D.Y.; validation, A.S., Z.U. and D.Y.; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, A.M.; resources, Z.U.; data curation, R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, Z.U.; visualization, D.B.; supervision, Z.U.; project administration, Z.U.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Jin, G.; Liang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y. Spatio-Temporal Graph Neural Networks for Predictive Learning in Urban Computing: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, Early Access, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, J.; Žliobaitė, I.; Bifet, A.; Pechenizkiy, M.; Bouchachia, A. A Survey on Concept Drift Adaptation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2014, 46, 44:1–44:37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Yin, H.; Zhu, Z. Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks: A Deep Learning Framework for Traffic Forecasting. In Proceedings of AAAI 2018; AAAI Press, 2018; pp. 3634–3641. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Lin, Y.; Feng, N.; Song, C.; Wan, H. Attention Based Spatial–Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks for Traffic Flow Forecasting. In Proceedings of AAAI 2019; AAAI Press, 2019; pp. 922–929. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, L.; Yao, L.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, C. Adaptive Graph Convolutional Recurrent Network for Traffic Forecasting. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020); Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M. F., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 2693–2704. [Google Scholar]

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H. B.; Avent, B.; et al. Advances and Open Problems in Federated Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.04977. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A. K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated Optimisation in Heterogeneous Networks. Proc. MLSys 2020, 2, 429–450. [Google Scholar]

- Bifet, A.; Gavaldà, R. Learning from Time-Changing Data with Adaptive Windowing. In Proceedings of SIAM SDM 2007; SIAM, 2007; pp. 443–448. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol, A.; Achiam, J.; Schulman, J. On First-Order Meta-Learning Algorithms. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.02999. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Sui, L.; Zhou, M.; Dong, H. Short-Term Passenger-Flow Forecast for Urban Rail Transit Based on Multi-Source Data. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Tao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y. Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network for Traffic Speed Prediction Using Remote Microwave Sensor Data. Transp. Res. Part C 2015, 54, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Arik, S. O.; Pfister, T. Temporal Fusion Transformers for Interpretable Multi-Horizon Time-Series Forecasting. Int. J. Forecast. 2021, 37, 1748–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, R.; Shahabi, C.; Liu, Y. Diffusion Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network: Data-Driven Traffic Forecasting. In Proceedings of ICLR 2018; OpenReview, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; et al. Informer: Beyond Efficient Transformer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of AAAI 2021; AAAI Press, 2021; pp. 11106–11115. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Long, G.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, C. Graph WaveNet for Deep Spatial–Temporal Graph Modelling. In Proceedings of IJCAI-19; IJCAI, 2019; pp. 1907–1913. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Torra, V. Differentially Private Traffic Flow Prediction Using Transformers: A Federated Approach. In Computer Security—ESORICS 2023 Workshops; LNCS 14398; Springer, 2024; pp. 260–271. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, B. M.; Martinello, M.; Trois, C.; et al. Fast Learning Enabled by In-Network Drift Detection. In Proceedings of APNet 2024; ACM, 2024; pp. 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Aji, A. F.; Heafield, K. Sparse Communication for Distributed Gradient Descent. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1704.05021. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel, D.; Topal, T.; Qian, H.; et al. Flower: A Friendly Federated Learning Research Framework. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2007.14390. [Google Scholar]

- Little, J. D. C. A Proof for the Queuing Formula L=λW. Oper. Res. 1961, 9, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F. X.; Mariano, R. S. Comparing Predictive Accuracy. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1995, 13, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Thorp, J.; Ainslie, J.; Eckstein, I.; Ontañón, S. FNet: Mixing Tokens with Fourier Transforms. In Findings of ACL–IJCNLP 2021; ACL, 2021; pp. 2622–2632. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).