1. Introduction

Sepsis is a life-threatening disease characterized by a dysregulated host response to infection leading to organ dysfunction[

1]. As a severe challenge in the global public health field, sepsis has always been one of the focuses of medical research. According to the global epidemiological data of The Lancet in 2020, approximately 50 million people worldwide suffer from sepsis each year[

2,

3]. The mortality rate is as high as 20%-30%. Its core pathological feature is the dysregulation of the host immune response triggered by infection, manifested as a dynamic imbalance between early excessive inflammation (such as the TNF-α and IL-6 storms) and late immunosuppression (such as T cell exhaustion), ultimately leading to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS)[

4]. The organ dysfunction caused by sepsis is systemic and leads to the impairment of organs far from the primary infection site, including the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys[

5,

6]. Among the affected organs, septic cardiomyopathy (SIMD) is particularly critical[

7,

8]. It is manifested as acute cardiac dysfunction, with an incidence rate of 13.8%-40% and a mortality rate as high as 70%-90%, posing a serious threat to human health[

9,

10]. Although its pathological mechanism has not been fully elucidated, recent studies have shown that protein ubiquitination, a non-traditional post-translational modification, plays a central regulatory role in the immune imbalance and organ injury in sepsis.

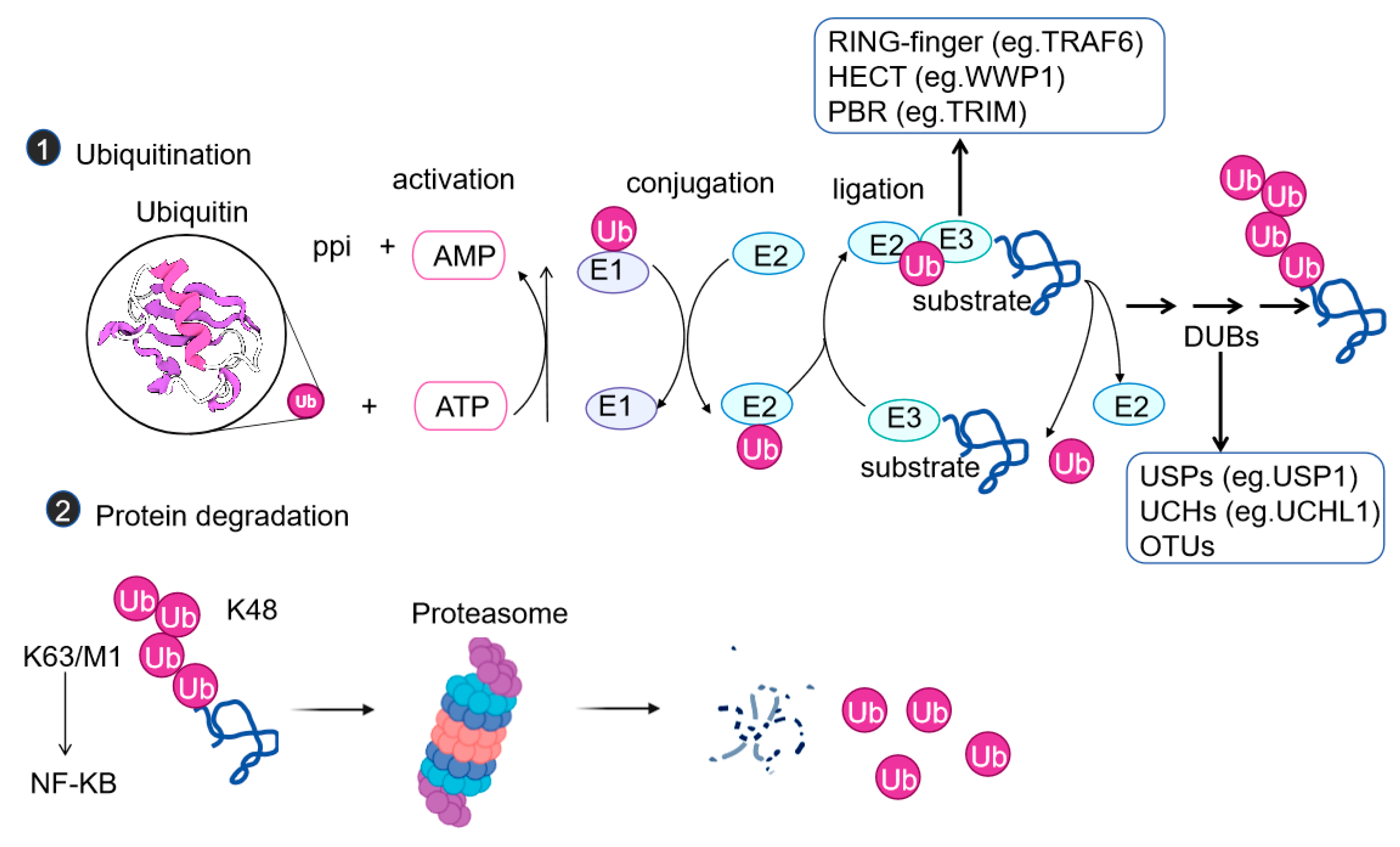

Protein ubiquitination, through the E1-E2-E3 enzyme cascade reaction, attaches ubiquitin molecules (76 amino acids) to target proteins via isopeptide bonds (lysine residues) or unconventional bonds (N-terminus, cysteine, etc.), forming various chain types such as K48 (for proteasomal degradation), K63 (for signal activation), and M1 (linear chain, for inflammatory regulation). Different from the traditionally recognized "proteasomal degradation function", recent studies have revealed that in sepsis, it regulates the inflammatory signaling pathway, immune cell polarization, and organ protection mechanisms through non-degradative modifications (such as K63/M1 chains). For example, the linear ubiquitin ligase complex LUBAC modifies RIPK1 by generating M1 chains, and the deubiquitinating enzyme USP5 removes the K63-linked polyubiquitin chains from RIPK1 to inhibit the activity of RIPK1, thereby suppressing the necroptosis pathway to protect cardiomyocytes[

11,

12]. The E3 ligase TRIM27 exacerbates oxidative stress in lung tissues by degrading PPARγ through K48 ubiquitination[

13]. These findings provide a new direction for the intervention of the "ubiquitination axis" in the treatment of sepsis.

2. Mechanisms of Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination is a post-translational modification in which one or usually a chain of small proteins, ubiquitin chains composed of 76 amino acids, are covalently linked to the lysine residues within the substrate proteins. Ubiquitination can affect the functions of proteins in various ways, such as influencing protein stability, turnover, cellular localization, and inducing conformational changes to affect interactions with other proteins[

14]. This process requires the sequential participation of E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes, E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, and E3 ubiquitin ligases (

Figure 1a). There are mainly three types of E3 ligases: the RING-type, the HECT-type, and the RBR type. The RING-type (such as TRAF6) directly catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin by recruiting E2 enzymes. The HECT type (such as WWP1) functions by forming a ubiquitin-E3 intermediate. The RBR type has the characteristics of both. The traditional K48-linked chains direct proteins to the proteasome for degradation, while K63 chains are involved in signal activation (such as the NF-κB pathway), and M1 chains (linear chains) regulate the assembly of inflammasomes[

15].

With the in-depth study, the non-canonical ubiquitination pathway has received much attention. It breaks through the traditional pattern, and unconventional types such as N-terminal formylation have emerged, playing an important role in physiological and pathological processes, especially in inflammation. During sepsis, non-canonical ubiquitination can rapidly respond to inflammation. For example, the E3 ligase HUWE1 modifies NLRP3 through non-lysine K27 chains to regulate inflammation[

16]. In the inflammatory signaling pathway, the mechanisms of ubiquitination are diverse and complex. The TNF-induced inflammatory pathway is regulated by both canonical (K48 linkage) and non-canonical (such as M1, K11 linkage, etc.) codes[

17]. The binding of TNF to TNFR triggers the formation of the TNFR complex I. In the initial stage, cIAPs and RIPK1 are ubiquitinated, and then related factors are recruited. The catalysis of ubiquitin esterification by HOIL-1 is crucial[

18]. Downstream, the phosphorylation of IκB-α leads to its K48-linked ubiquitination and degradation, promoting the nuclear translocation of NF-κB. The ubiquitination of RIPK1 in different complexes can induce apoptosis or necroptosis[

19]. In the IL-1-mediated pathway, the mixed chains of K11 and K63 regulate NF-κB, expanding the concept of ubiquitin signal transduction[

20]. Non-canonical ubiquitination is also crucial in other physiological processes. For example, in Parkin-mediated mitophagy, damaged mitochondria can recruit the kinase PINK1 and the E3 ligase PARKIN, inducing the PINK1-dependent phosphorylation of ubiquitin and PARKIN[

21], which, together with the regulation of ubiquitination in inflammation, reflects its wide role in the physiological and pathological processes of cells.

3. Ubiquitination in Sepsis and the Inflammatory Response

3.1. Regulation of the Production of Inflammatory Cytokines

The abnormal expression of inflammatory cytokines is one of the core pathological mechanisms of inflammatory diseases such as sepsis. The nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway, as a key hub for the transcription of inflammatory cytokines, has its activity precisely regulated by ubiquitination modifications. Upon stimulation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) or tumor necrosis factor receptors (TNFRs), ubiquitination activates the NF-κB signaling pathway through the non-degradative effects of K63/M1-type polyubiquitin chains. After TLR activation, MyD88 and IRAK1/4 are recruited, which then bind to TRAF6 and undergo K63-type polyubiquitination with the cooperation of Ubc13. This modification does not rely on protein degradation but serves as a signaling platform to recruit downstream kinases (such as TAK1), initiating the NF-κB activation program. TNFR stimulation depends on the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC) to extend the K63 chain with M1-type ubiquitin chains, recruiting the IKK complex through NEMO to release the NF-κB transcription factor and driving the transcription of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β[

22,

23,

24,

25]. It is worth noting that this K63/M1-type ubiquitination belongs to a non-degradative modification, and its core function is to promote the nuclear translocation of NF-κB by constructing a signaling complex, rather than inducing the degradation of target proteins[

26]. In addition, deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) such as OTULIN (an OUT deubiquitinase with linear bond specificity), CYLD (cylindromatosis), and A20 limit the excessive activation of NF-κB by removing ubiquitin chains[

23,

24,

25].

The traditional view is that ubiquitination inhibits NF-κB by mediating the proteasomal degradation of p65 through K48-type chains. However, the latest research has found that in the LPS-induced sepsis model, VANGL2 recruits PDLIM2 to catalyze the K63-type ubiquitination of p65. The selective autophagy receptor NDP52 transports p65 to the autolysosome for degradation by recognizing the K63 chain, and this process does not rely on the proteasome, reflecting the specific association between the type of ubiquitination modification and the degradation pathway[

27].

3.2. Regulation of the Activation of Inflammasomes

Inflammasomes play a key role in the inflammatory response of sepsis, and the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is one of the most widely studied types. Recent studies have shown that the protein ubiquitination system is involved in regulating the activation process of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and this mechanism is of great significance for the development of sepsis. Ubiquitination and deubiquitination modifications can play a protective role in inflammatory-related diseases by regulating various pathological processes such as excessive inflammatory responses, pyroptosis, abnormal autophagy, proliferation disorders, and oxidative stress injuries[

14]. Take the non-canonical ubiquitination regulation mechanism as an example:

The dual role of WWP1: Although the overexpression of WWP1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, can promote the ubiquitination of NLRP3, it can simultaneously inhibit the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the cleavage of GSDMD mediated by caspase-1. In addition, WWP1 is downregulated in sepsis. It can promote the proteasomal degradation of TRAF6 by inducing K48-linked polyubiquitination, negatively regulating the release of TNF-α and IL-6 mediated by TLR4[

28,

29].

The specific regulation of HUWE1: In the LPS and ATP-induced mouse bone marrow-derived macrophage (BMDM) model, the HECT-type E3 ligase HUWE1 directly interacts with the NACHT domain of NLRP3 through its BH3 domain, triggering non-lysine-dependent K27-linked polyubiquitination modification. This modification does not mediate protein degradation but promotes the assembly of the inflammasome by inducing a conformational change of NLRP3, thereby enhancing the maturation of Caspase-1 and the release of downstream pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-1β[

12].

The negative regulation of USP22: Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 22 (USP22) can degrade NLRP3 through the ATG5-mediated autophagy pathway, thereby inhibiting the activation of the inflammasome. Mechanistically, USP22 stabilizes ATG5 by reducing the K27 and K48-linked ubiquitination of ATG5 at the Lys118 site. In vivo studies have shown that the deficiency or silencing of USP22 will significantly exacerbate the peritonitis induced by alum and the systemic inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide[

30]. In summary, targeting the excessive activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome provides a potential strategy for the prevention or treatment of inflammatory-related diseases such as sepsis, and the in-depth analysis of the ubiquitination modification mechanism will lay the foundation for the development of new therapeutic targets.

4. Ubiquitination in Sepsis and Immune Cell Functions

4.1. Macrophage Polarization

In the pathogenesis of sepsis, the balance of M1/M2 macrophage polarization is a key immune regulation, and its state directly affects the outcome of the disease. Macrophages polarize into pro-inflammatory M1 type and anti-inflammatory M2 type. The dynamic imbalance between the two is closely related to the progression of sepsis, but its molecular mechanism has not been fully elucidated. Studies have shown that the level of malignant fibrous histiocytoma amplified sequence 1 (MFHAS1) in sepsis patients is significantly increased, and it drives the inflammatory response by activating the TLR2/JNK/NF-κB pathway[

31]. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Praja2 can bind to MFHAS1 and mediate its non-degradative ubiquitination, promoting the accumulation of MFHAS1, and then enhancing the activation of the JNK/p38 signaling pathway mediated by TLR2, driving the polarization of macrophages from the M2 type to the M1 type and exacerbating the inflammatory response[

31]. Other studies have further revealed the diversity of ubiquitination regulation: the interaction between A20 and NEK7: A20 can directly bind to NEK7, promote its proteasomal degradation through enhanced ubiquitination (the key functional sites are the K189 and K293 residues of NEK7), and inhibit the binding of NEK7 to the NLRP3 complex through the OTU domain and the ZnF 4/ZnF 7 motifs. Interfering with the function of NEK7 in macrophages can significantly inhibit pyroptosis and alleviate the process of sepsis[

14,

32].

The regulatory role of UBE2M: In the Escherichia coli-induced sepsis mouse model, the specific deletion of UBE2M, a key enzyme for ubiquitination modification in macrophages, can reduce the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, organ damage and improve the survival rate, without affecting the ability to clear bacteria. Mechanistically, the deletion of UBE2M inhibits the activation of the NF-κB, ERK, and JAK-STAT signaling pathways, downregulating the excessive inflammatory response[

33].

4.2. Regulation of T-Cell Functions

T cells play an important role in the immune response of sepsis, and ubiquitination affects their functions by regulating the activation, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of T cells. Among them, Casitas B lymphoma-b (Cbl-b) is a key downstream regulator of the CD28 and CTLA-4 co-stimulation/co-inhibition signaling pathway, and E3 ubiquitin ligases play a central role in the regulation of effector T cell functions[

34]. Cbl-b, through multiple protein interaction domains (such as binding to TCR signaling molecules such as LCK, SLP76, and ZAP70), cooperates with the E3 ligase Itch to mediate the polyubiquitination of the Lys33 site of the TCR-ζ subunit. This modification does not induce the degradation or endocytosis of TCR but inhibits the activation of T cells by preventing the phosphorylation of TCR and its binding to the downstream ZAP70 kinase, and this process does not require CD28 co-stimulation[

35,

36]. It is worth noting that Cbl-b knockout mice exhibit excessive activation of T cells (independent of CD28 stimulation), but no autoimmune damage has been observed[

37,

38]. This characteristic makes Cbl-b a potential target for cancer immunotherapy - it has multiple immune checkpoint inhibitory functions and a relatively low risk of autoimmune toxicity[

36].

5. Ubiquitination in Sepsis and Organ Protection

5.1. Lung Protection

The lung is one of the organs most vulnerable to sepsis, and its injury and fibrosis processes are closely related to ubiquitination regulation. Studies have shown that in LPS-induced sepsis mice, the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM27 is significantly upregulated and positively correlated with the degree of lung injury. Knocking down TRIM27 can inhibit the ubiquitination degradation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), reduce the expression of NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) and the activation of the downstream p-p65 inflammatory pathway, alleviate the inflammatory infiltration, apoptosis, and oxidative stress injury of lung tissues. Overexpressing NOX4 can reverse this protective effect[

13], revealing the key role of the "TRIM27-PPARγ-NOX4" ubiquitination axis in the lung injury of sepsis. In addition, pulmonary fibrosis in sepsis is related to ubiquitination regulation. The E3 ubiquitin ligase tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) and the deubiquitinating enzyme USP38 regulate the level and signal transduction of the interleukin 33 receptor (IL-33R) through K27-linked polyubiquitination and deubiquitination, thereby affecting the inflammatory response and fibrosis of the lungs, providing a precise direction for related treatments[

39]

5.2. Liver Protection

Liver injury induced by sepsis is a common complication. Although the liver has a relatively low incidence of failure due to its strong regenerative and anti-inflammatory capabilities, the mortality rate of septic patients with liver failure is high[

40]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop theories and treatment methods for liver protection and the prevention of liver failure. Studies have shown that ubiquitination is involved in regulating the process of liver injury in sepsis. It exerts its effects by regulating hepatocyte metabolism, functions, and responses to oxidative stress. Some ubiquitin-related proteins can protect hepatocytes from the damage of inflammatory cytokines by degrading damaged proteins or activating antioxidant signaling pathways. For example, OTUD1 reduces oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation induced by liver ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. Mechanistically, OTUD1 deubiquitinates and activates nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) through its catalytic cysteine 320 residues and the ETGE motif, thereby alleviating liver I/R injury[

41].

In the LPS-induced sepsis model, the excessive activation of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) in macrophages is a key factor driving the inflammatory response. Pimpinellin can upregulate the E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF146, promote K48-linked ubiquitination modification, and target PARP1 for degradation. This inhibits the release of pro-inflammatory factors such as TNF-α and IL-6 by macrophages and significantly reduces the inflammatory infiltration, apoptosis, and oxidative stress injury of hepatocytes induced by LPS. This protective effect depends on the PARP1 ubiquitination degradation pathway, and knocking out PARP1 will eliminate the ameliorative effect of impaneling on liver injury in sepsis. Mechanistically, pimpinellin enhances the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of PARP1, blocks the parthanatos cell death pathway, and restores mitochondrial function, providing a new intervention target of the "RNF146/PARP1 ubiquitination axis" for the treatment of liver injury in sepsis [

42]. In addition, a decrease in the level of deubiquitinase USP4 will exacerbate liver inflammation and fibrosis[

43,

44].

5.3. Cardiac Function

Sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction (SIMD) is a severe complication of sepsis, characterized by impaired cardiac function and a high mortality rate. Ubiquitination and deubiquitination, as key post-translational modifications (PTMs), are involved in crucial cellular processes such as inflammation, apoptosis, mitochondrial function, and calcium handling by regulating protein stability, localization, and activity. The dysregulation of the ubiquitination and deubiquitination systems has been gradually confirmed to be closely related to the pathogenesis of SIMD. The dysfunction of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is often driven by changes in the activity of E3 ligases, which accelerate the degradation of key regulatory proteins and exacerbate cardiac inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. The imbalance of deubiquitinase (DUB) activity disrupts protein homeostasis and further amplifies myocardial damage[

1]. For example, ubiquitin-specific peptidase 7 (USP7) can stabilize the transcription factor SOX9 through deubiquitination and upregulate its protein expression. SOX9 inhibits the expression of miR-96-5p by binding to its promoter region and then promotes the expression of NLRP3, exacerbating myocardial injury and pyroptosis of cardiomyocytes induced by sepsis[

45].

5.4. Renal Function

More than half of critically ill septic patients will develop acute kidney injury (AKI), which significantly increases the risk of death[

46]. The pro-inflammatory effect of macrophages can exacerbate tubular injury in the early stage of AKI. The ubiquitination mechanism is involved in the protection of AKI by regulating macrophage functions and mitophagy. E3 ubiquitin ligases MARCHF1 and MARCHF8 can ubiquitinate the T cell activation molecule 1 (TARM1) on the surface of myeloid cells, induce its internalization, and degrade it in phagolysosomes, thereby inhibiting excessive renal inflammation and reducing AKI[

47].

Meanwhile, the PINK1/PARK2 pathway in renal cells recruits and phosphorylates to activate the E3 ligase activity of PARK2 through PINK1, prompting the ubiquitination labeling of damaged mitochondria and their phagocytosis and degradation by autophagosomes, alleviating sepsis-related AKI through mitophagy[

48].

5.5. Intestinal Function

The intestine is an important target organ for immune regulation in sepsis, and its dysfunction is closely related to the gut microbiota, immune cells, and the ubiquitination mechanism. A large number of immune cells and microorganisms inhabit the intestine, and the metabolites derived from the microbiota can maintain the immune homeostasis of the intestine and the whole body[

49]. Sepsis can induce an increase in apoptosis, a decrease in proliferation, and a decline in the migration ability of intestinal epithelial cells, thereby disrupting the intestinal mucosal barrier.

Studies have shown that ubiquitin-specific peptidase 47 (USP47) is involved in the occurrence of intestinal injury in sepsis by regulating the inflammatory signaling pathway in intestinal epithelial cells. USP47 removes the K63-type polyubiquitination modification of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), stabilizes the TRAF6 protein, and activates its downstream inflammatory pathway, thus exacerbating the intestinal inflammatory response[

50]. This mechanism reveals the crucial role of ubiquitination modification in the intestinal immune dysregulation of sepsis and provides a potential intervention direction for targeting intestinal inflammation.

6. Conclusions

Protein ubiquitination plays multiple non-traditional roles in sepsis, involving the regulation of the inflammatory response, the modulation of immune cell functions, and organ protection. These non-traditional roles are different from the classical functions of ubiquitination in protein degradation and cell cycle control, providing a new perspective for understanding the pathogenesis of sepsis. Exploring the molecular mechanisms of protein ubiquitination in sepsis is conducive to the discovery of new therapeutic targets and is of great significance for the development of new treatment strategies for sepsis. In the future, more in-depth research is needed to elucidate the complex network of ubiquitination in sepsis and provide more effective assistance for clinical treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Y.C. and Y.L.; methodology, M.Y.C.; formal analysis, M.Y.C.; investigation, M.Y.C.; resources, M.Y.C. and Y.L.; data curation, M.Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y.C. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, M.Y.C. and M.F.; visualization, M.F.; supervision, M.F.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M760779).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make the data available upon reasonable request.

References

- Wang, Z.; Sun, S.; Huang, L.; Chen, X.; Xu, H.; Ma, H.; Xiao, M.; Wang, L. Pathological roles of ubiquitination and deubiquitination systems in sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction. Biomol. Biomed. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Wang, G.; Xie, J. Immune dysregulation in sepsis: experiences, lessons and perspectives. Cell Death Discov. 2023. 9(1):465. [CrossRef]

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.;Aschenbrenner, A.C.;Bauer, M.;Bock, C.;Calandra, T.;Gat-Viks, I.;Kyriazopoulou, E.;Lupse, M.;Monneret, G.;Pickkers, P., et al. The pathophysiology of sepsis and precision-medicine-based immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 2024. 25(1):19-28. [CrossRef]

- Barichello, T.; Generoso, J.S.; Singer, M.; Dal-Pizzol, F. Biomarkers for sepsis: more than just fever and leukocytosis-a narrative review. Crit. Care. 2022. 26(1). [CrossRef]

- Willmann, K.; Moita, L.F. Physiologic disruption and metabolic reprogramming in infection and sepsis. Cell Metab. 2024. 36(5):927-946. [CrossRef]

- Srdic, T.;Durasevic, S.;Lakic, I.;Ruzicic, A.;Vujovic, P.;Jevdovic, T.;Dakic, T.;Dordevic, J.;Tosti, T.;Glumac, S., et al. From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Therapy: Understanding Sepsis-Induced Multiple Organ Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024. 25(14). [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, H.; Rui, T.; Guo, J. Research Progress on Mechanisms and Treatment of Sepsis-Induced Myocardial Dysfunction. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024. 17:3387-3393. [CrossRef]

- Shvilkina, T.; Shapiro, N. Sepsis-Induced myocardial dysfunction: heterogeneity of functional effects and clinical significance. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023. 10:1200441. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wang, W.; Lee, M.; Meng, Q.; Ren, H. Current Status of Septic Cardiomyopathy: Basic Science and Clinical Progress. Front. Pharmacol. 2020. 11:210. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.K.; Yu, J.C.; Li, R.B.; Zhou, H.; Chang, X. New insights into the role of mitochondrial metabolic dysregulation and immune infiltration in septic cardiomyopathy by integrated bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2024. 29(1). [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Lu, H.; Ma, L.; Ding, C.; Wang, H.;Chu, Y. Deubiquitinase USP5 regulates RIPK1 driven pyroptosis in response to myocardial ischemic reperfusion injury. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024. 22(1):466. [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Li, D.; Liang, W.; Sun, W.; Xie, X.; Tong, Y.; Shan, B.; Zhang, M.; Lu, X.; Yuan, J., et al. PP6 negatively modulates LUBAC-mediated M1-ubiquitination of RIPK1 and c-FLIP(L) to promote TNFalpha-mediated cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2022. 13(9):773.

- Ning, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wei, J.; Hu, G.; Xing, P. Knockdown of TRIM27 alleviated sepsis-induced inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative stress via suppressing ubiquitination of PPARgamma and reducing NOX4 expression. Inflamm. Res. 2022. 71(10-11):1315-1325.

- Tang, S.; Geng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Q.; Yu, Y.;Li, H. The roles of ubiquitination and deubiquitination of NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammation-related diseases: A review. Biomol. Biomed. 2024. 24(4):708-721. [CrossRef]

- Renz, C.;Asimaki, E.;Meister, C.;Albanese, V.;Petriukov, K.;Krapoth, N.C.;Wegmann, S.;Wollscheid, H.P.;Wong, R.P.;Fulzele, A., et al. Ubiquiton-An inducible, linkage-specific polyubiquitylation tool. Mol. Cell. 2024. 84(2):386-400 e11. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.;Li, L.;Xu, T.;Guo, X.;Wang, C.;Li, Y.;Yang, Y.;Yang, D.;Sun, B.;Zhao, X., et al. HUWE1 mediates inflammasome activation and promotes host defense against bacterial infection. J. Clin. Invest. 2020. 130(12):6301-6316. [CrossRef]

- Cockram, P.E.; Kist, M.; Prakash, S.; Chen, S.H.; Wertz, I.E.; Vucic, D. Ubiquitination in the regulation of inflammatory cell death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2021. 28(2):591-605. [CrossRef]

- Fuseya, Y.; Fujita, H.; Kim, M.; Ohtake, F.; Nishide, A.; Sasaki, K.; Saeki, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Takahashi, R.;Iwai, K. The HOIL-1L ligase modulates immune signalling and cell death via monoubiquitination of LUBAC. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020. 22(6):663-673. [CrossRef]

- Huyghe, J.; Priem, D.; Bertrand, M.J.M. Cell death checkpoints in the TNF pathway. Trends Immunol. 2023. 44(8):628-643. [CrossRef]

- Ohtake, F.; Saeki, Y.; Ishido, S.; Kanno, J.;Tanaka, K. The K48-K63 Branched Ubiquitin Chain Regulates NF-kappaB Signaling. Mol. Cell. 2016. 64(2):251-266. [CrossRef]

- Herhaus, L.; Dikic, I. Expanding the ubiquitin code through post-translational modification. EMBO Rep. 2015. 16(9):1071-83. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zhu, L.; Xia, L.; Xiong, Y.; Yin, Q.; Rui, K. Roles of Ubiquitination and Deubiquitination in Regulating Dendritic Cell Maturation and Function. Front. Immunol. 2020. 11:586613. [CrossRef]

- Griewahn, L.; Koser, A.; Maurer, U. Keeping Cell Death in Check: Ubiquitylation-Dependent Control of TNFR1 and TLR Signaling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019. 7:117. [CrossRef]

- Lork, M.; Verhelst, K.; Beyaert, R. CYLD, A20 and OTULIN deubiquitinases in NF-kappaB signaling and cell death: so similar, yet so different. Cell Death Differ. 2017. 24(7):1172-1183.

- Spit, M.; Rieser, E.; Walczak, H. Linear ubiquitination at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2019. 132(2). [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M. Role of K63-linked polyubiquitination in NF-kappaB signalling: which ligase catalyzes and what molecule is targeted? J. Biochem. 2012. 151(2):115-8. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.;Zhang, J.;Jiang, H.;Hu, Z.;Zhang, Y.;He, L.;Yang, J.;Xie, Y.;Wu, D.;Li, H., et al. Vangl2 suppresses NF-kappaB signaling and ameliorates sepsis by targeting p65 for NDP52-mediated autophagic degradation. Elife 2024. 12.

- Lin, X.W.; Xu, W.C.; Luo, J.G.; Guo, X.J.; Sun, T.; Zhao, X.L.; Fu, Z.J. WW domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (WWP1) negatively regulates TLR4-mediated TNF-alpha and IL-6 production by proteasomal degradation of TNF receptor associated factor 6 (TRAF6). PLoS One 2013. 8(6):e67633. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.;Guan, X.;Liu, W.;Zhu, Z.;Jin, H.;Zhu, Y.;Chen, Y.;Zhang, M.;Xu, C.;Tang, X., et al. YTHDF1 alleviates sepsis by upregulating WWP1 to induce NLRP3 ubiquitination and inhibit caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis. Cell Death Discov. 2022. 8(1):244. [CrossRef]

- Di, Q.; Zhao, X.; Tang, H.; Li, X.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, H.; Wu, Z.; Quan, J.;Chen, W. USP22 suppresses the NLRP3 inflammasome by degrading NLRP3 via ATG5-dependent autophagy. Autophagy 2023. 19(3):873-885. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Sun, Z.; Chen, J.; Xu, Y.; Weng, M.; Shi, Q.; Ma, D.;Miao, C. Ubiquitylation of MFHAS1 by the ubiquitin ligase praja2 promotes M1 macrophage polarization by activating JNK and p38 pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2017. 8(5):e2763. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Luo, M.; Chen, S.; Shen, G.; Wei, X.;Shao, B. Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by A20 through modulation of NEK7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A . 2024. 121(25):e2316551121. [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.;Bai, S.;Xiong, G.;Xiu, H.;Li, J.;Yang, J.;Yu, Q.;Li, B.;Hu, R.;Cao, L., et al. Inhibition of the neddylation E2 enzyme UBE2M in macrophages protects against E. coli-induced sepsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2025. 301(1):108085. [CrossRef]

- Augustin, R.C.; Bao, R.; Luke, J.J. Targeting Cbl-b in cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023. 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Lutz-Nicoladoni, C.; Wolf, D.; Sopper, S. Modulation of Immune Cell Functions by the E3 Ligase Cbl-b. Front. Oncol. 2015. 5:58. [CrossRef]

- Gavali, S.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Paolino, M. Ubiquitination in T-Cell Activation and Checkpoint Inhibition: New Avenues for Targeted Cancer Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021. 22(19). [CrossRef]

- Schanz, O.;Cornez, I.;Yajnanarayana, S.P.;David, F.S.;Peer, S.;Gruber, T.;Krawitz, P.;Brossart, P.;Heine, A.;Landsberg, J., et al. Tumor rejection in Cblb(-/-) mice depends on IL-9 and Th9 cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021. 9(7).

- Thell, K.; Urban, M.; Harrauer, J.; Haslinger, I.; Kuttke, M.; Brunner, J.S.; Vogel, A.; Schabbauer, G.; Penninger, J.; Gaweco, A. Master checkpoint Cbl-b inhibition: Anti-tumour efficacy in a murine colorectal cancer model following siRNA-based cell therapy. Ann. Oncol. 2019. 30:503-+. [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.M.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.D.; Shu, H.B.;Li, S. Reciprocal regulation of IL-33 receptor-mediated inflammatory response and pulmonary fibrosis by TRAF6 and USP38. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A . 2022. 119(10):e2116279119. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Ji, F.; Ronco, C.; Tian, J.;Yin, Y. Gut-liver crosstalk in sepsis-induced liver injury. Crit. Care. 2020. 24(1):614. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.;Chen, Z.;Li, J.;Huang, K.;Ding, Z.;Chen, B.;Ren, T.;Xu, P.;Wang, G.;Zhang, H., et al. The deubiquitinase OTUD1 stabilizes NRF2 to alleviate hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Redox Biol. 2024. 75:103287. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Du, M.; Liu, K.; Wang, P.; Zhu, J.; Li, F.; Wang, Z.; Huang, K.;Liang, M. Pimpinellin ameliorates macrophage inflammation by promoting RNF146-mediated PARP1 ubiquitination. Phytother. Res. 2024. 38(4):1783-1798. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Qiu, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhang, L.;Zou, J. USP4 deficiency exacerbates hepatic ischaemia/reperfusion injury via TAK1 signalling. Clin. Sci. 2019. 133(2):335-349. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Luo, Z.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, P.; Xu, D.; Du, M.; Wang, B., et al. H19/miR-148a/USP4 axis facilitates liver fibrosis by enhancing TGF-beta signaling in both hepatic stellate cells and hepatocytes. J. Cell Physiol. 2019. 234(6):9698-9710. [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Zhou, F. USP7-SOX9-miR-96-5p-NLRP3 Network Regulates Myocardial Injury and Cardiomyocyte Pyroptosis in Sepsis. Hum. Gene Ther. 2022. 33(19-20):1073-1090. [CrossRef]

- Caraballo, C.; Jaimes, F. Organ Dysfunction in Sepsis: An Ominous Trajectory From Infection To Death. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2019. 92(4):629-640.

- Huang, X.R.;Ye, L.;An, N.;Wu, C.Y.;Wu, H.L.;Li, H.Y.;Huang, Y.H.;Ye, Q.R.;Liu, M.D.;Yang, L.W., et al. Macrophage autophagy protects against acute kidney injury by inhibiting renal inflammation through the degradation of TARM1. Autophagy 2025. 21(1):120-140. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Z.; Shu, S.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cai, J.; Tang, C.; Liu, Y.; Yin, X., et al. The PINK1/PARK2/optineurin pathway of mitophagy is activated for protection in septic acute kidney injury. Redox Biol. 2021. 38:101767. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, N.; Su, X.; Gao, Y.;Yang, R. Gut-Microbiota-Derived Metabolites Maintain Gut and Systemic Immune Homeostasis. Cells 2023. 12(5). [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Yang, L.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, M.; Wu, Y. Ubiquitin-specific protease 47 regulates intestinal inflammation through deubiquitination of TRAF6 in epithelial cells. Sci. China Life Sci. 2022. 65(8):1624-1635. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).