Submitted:

12 May 2025

Posted:

13 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A novel hierarchical framework that processes and integrates multimodal data through specialized neural pathways before combining them in higher cognitive layers

- An adaptive attention mechanism that dynamically weighs information based on context relevance and reliability

- A transparent reasoning component that provides explanations for AI decisions, enhancing trust in human-AI collaborations

- Comprehensive empirical evaluation demonstrating superior performance in complex multimodal understanding tasks

2. Related Work

2.1. Multimodal Learning Systems

2.2. Cognitive Architectures

2.3. Human-AI Interaction

3. Theoretical Background

3.1. Multimodal Integration

3.2. Hierarchical Processing

4. Methodology

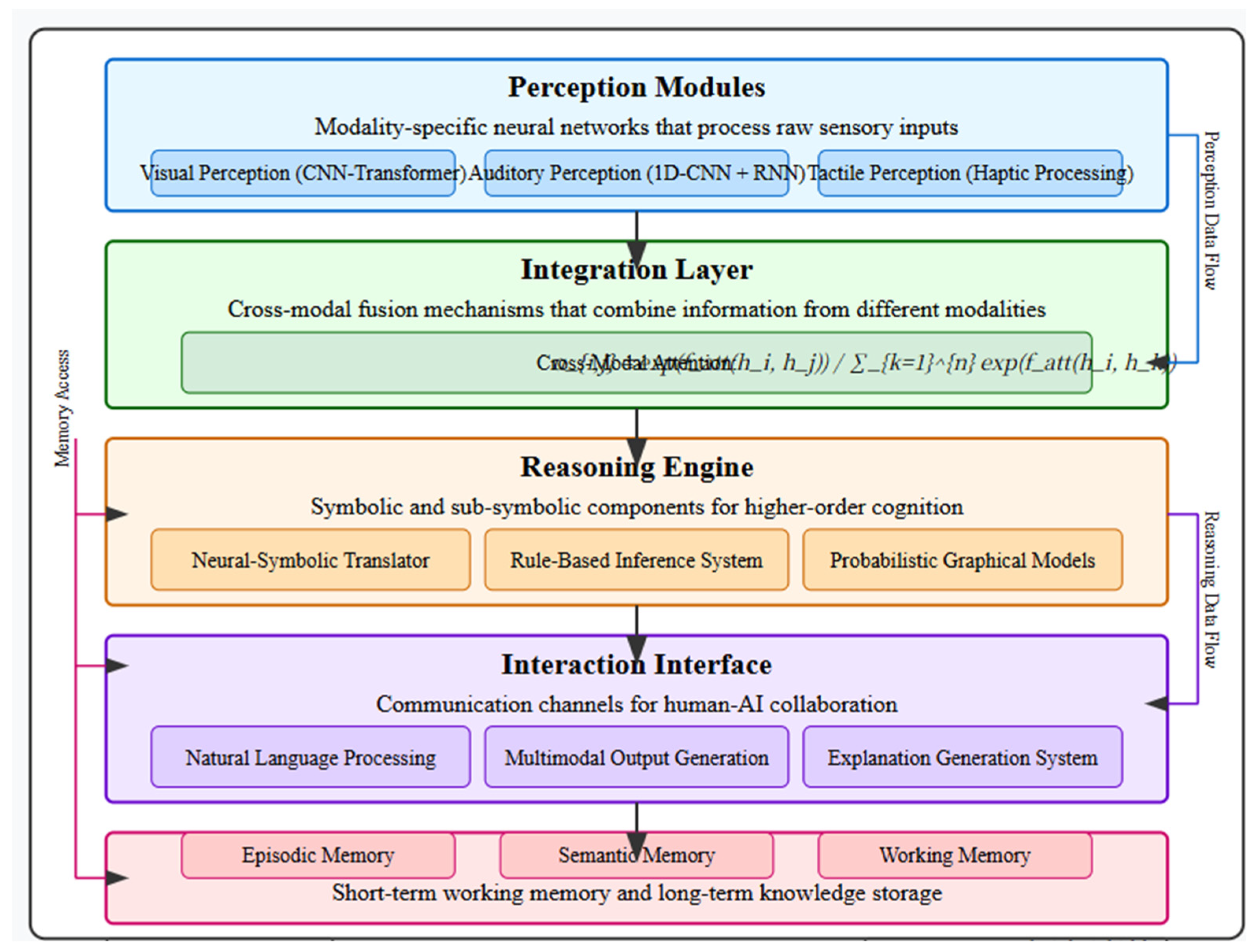

4.1. System Architecture

- Perception Modules: Modality-specific neural networks that process raw sensory inputs

- Integration Layer: Cross-modal fusion mechanisms that combine information from different modalities

- Reasoning Engine: Symbolic and sub-symbolic components for higher-order cognition

- Interaction Interface: Communication channels for human-AI collaboration

- Memory Systems: Short-term working memory and long-term knowledge storage

4.2. Model Design and Components

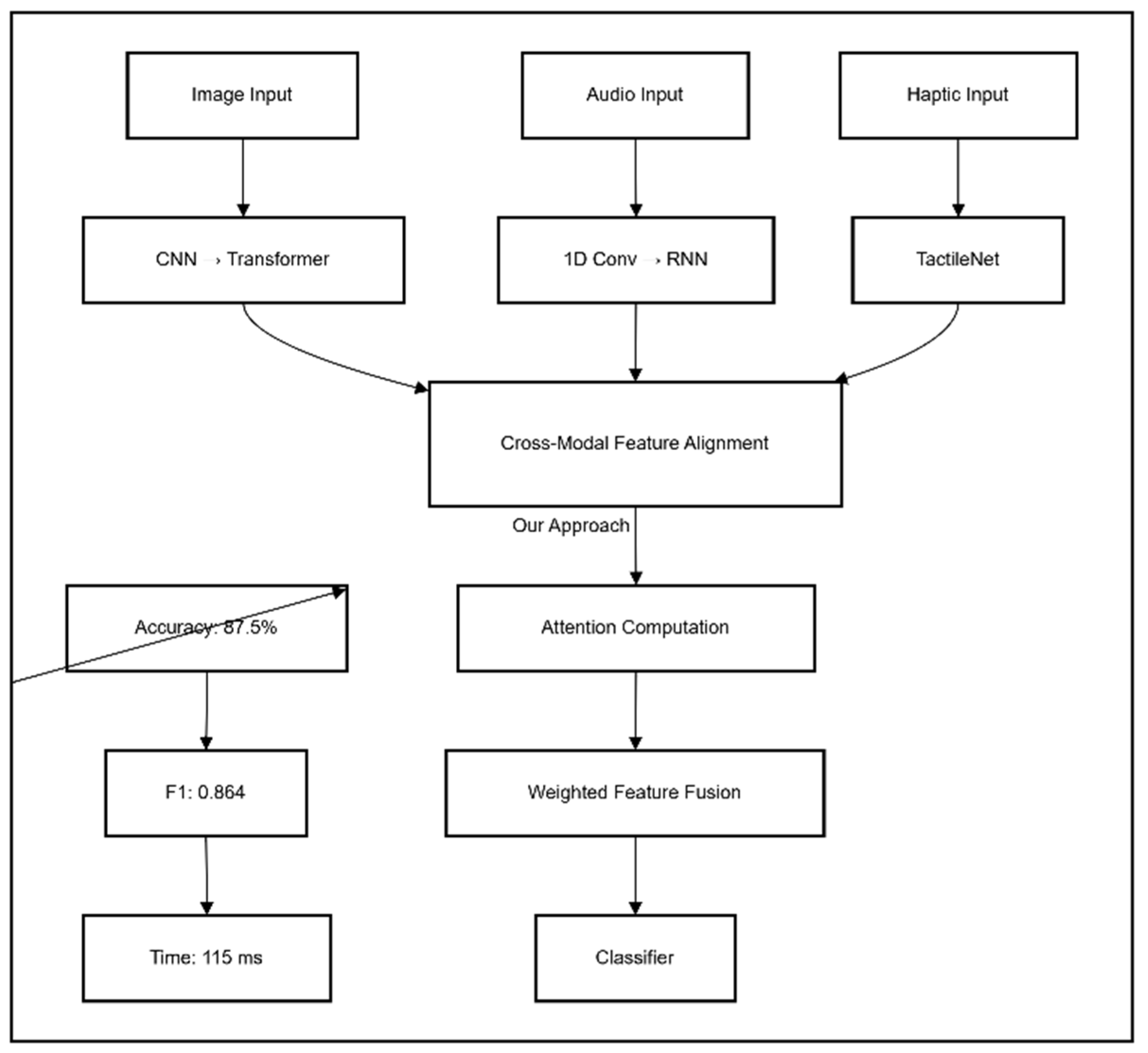

- Visual Perception: A hybrid CNN-Transformer architecture processes images and video. The CNN extracts low-level features which are then processed by self-attention mechanisms to capture spatial relationships.

- Auditory Perception: A combination of 1D convolutional networks and recurrent layers processes audio signals, extracting both temporal and frequency features.

- Tactile Perception: For robotic applications, a specialized network processes haptic feedback data to extract physical properties like texture, temperature, and pressure.

- A neural-symbolic translator that maps distributed representations to symbolic structures

- A rule-based system for logical inference

- An uncertainty handling mechanism based on probabilistic graphical models

- Natural language processing for understanding human instructions

- Multimodal output generation (text, speech, visualizations)

- Explanation generation mechanisms that provide insights into system reasoning

- Episodic memory that stores experiences as sequences of events

- Semantic memory that organizes conceptual knowledge

- Working memory that maintains information relevant to current tasks

4.3. Implementation Details

4.4. Experimental Setup

- Multimodal Scene Understanding: Requiring the system to identify objects, actions, and their relationships from video and audio

- Human-AI Collaborative Problem Solving: Measuring performance on tasks requiring coordination between the AI system and human participants

- Explainability Assessment: Evaluating the quality of explanations provided by the system

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Multimodal Perception Performance

5.2. Human-AI Collaboration

5.3. Ablation Studies

6. Discussion

6.1. Interpretation of Results

6.2. Implications of Findings

- Multimodal Integration: The results suggest that sophisticated integration mechanisms outperform simple fusion approaches, especially in noisy or ambiguous environments.

- Transparency and Explanation: The substantial improvement in collaboration metrics when explanation components are present confirms that explainability is not merely a regulatory requirement but a practical necessity for effective human-AI teamwork.

- Cognitive Architecture Design: The benefits of hierarchical processing and specialized components indicate that monolithic end-to-end models may be insufficient for complex interactive AI systems.

6.3. Limitations and Constraints

- Computational Complexity: The hierarchical architecture requires significant computational resources, potentially limiting deployment on resource-constrained devices.

- Training Requirements: The architecture’s multiple components necessitate careful training procedures and larger datasets compared to end-to-end approaches.

- Domain Adaptation: While the system performed well on the evaluated tasks, transferring to substantially different domains may require architectural modifications.

7. Discussion

8. Future Work

- Adaptive Architecture: Developing mechanisms for the architecture to dynamically adjust its structure based on task requirements and available computational resources.

- Continual Learning: Extending the framework to support continuous learning from interaction experiences without catastrophic forgetting.

- Cultural and Contextual Adaptation: Enhancing the system’s ability to adapt to different cultural contexts and social norms in human-AI interaction.

- Privacy-Preserving Perception: Integrating privacy-preserving techniques that protect sensitive information while maintaining perceptual capabilities.

Acknowledgments

References

- D. H. Park, L. A. Hendricks, Z. Akata, A. Rohrbach, B. Schiele, T. Darrell, and M. Rohrbach, “Multimodal explanations: Justifying decisions and pointing to the evidence,” in Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., 2018, pp. 8779-8788. [CrossRef]

- S. Amershi, D. Weld, M. Vorvoreanu, A. Fourney, B. Nushi, P. Collisson, J. Suh, S. Iqbal, P. N. Bennett, K. Inkpen, J. Teevan, R. Kikin-Gil, and E. Horvitz, “Guidelines for human-AI interaction,” in Proc. CHI Conf. Human Factors Comput. Syst., 2019, pp. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, W. Huang, F. Sun, T. Xu, Y. Rong, and J. Huang, “Deep multimodal fusion by channel exchanging,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 1601-1615, 2021.

- A. Nagrani, S. Yang, A. Arnab, A. Jansen, C. Schmid, and C. Sun, “Attention bottlenecks for multimodal fusion,” in Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., 2021, pp. 14200-14213.

- J. Lu, D. Batra, D. Parikh, and S. Lee, “ViLBERT: Pretraining task-agnostic visiolinguistic representations for vision-and-language tasks,” in Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., 2019, pp. 13-23.

- H. Tan and M. Bansal, “LXMERT: Learning cross-modality encoder representations from transformers,” in Proc. Conf. Empirical Methods Natural Lang. Process., 2019, pp. 5100-5111. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Anderson, D. Bothell, M. D. Byrne, S. Douglass, C. Lebiere, and Y. Qin, “An integrated theory of the mind,” Psychol. Rev., vol. 111, no. 4, pp. 1036-1060, 2004. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Laird, The Soar Cognitive Architecture. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2012.

- R. Sun, “The CLARION cognitive architecture: Extending cognitive modeling to social simulation,” in Cognition and Multi-Agent Interaction, R. Sun, Ed. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006, pp. 79-99. [CrossRef]

- S. Franklin, T. Madl, S. D’Mello, and J. Snaider, “LIDA: A systems-level architecture for cognition, emotion, and learning,” IEEE Trans. Auton. Mental Develop., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 19-41, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Mao, C. Gan, P. Kohli, J. B. Tenenbaum, and J. Wu, “The neuro-symbolic concept learner: Interpreting scenes, words, and sentences from natural supervision,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent., 2019.

- S. Amershi, M. Cakmak, W. B. Knox, and T. Kulesza, “Power to the people: The role of humans in interactive machine learning,” AI Mag., vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 105-120, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Ribeiro, S. Singh, and C. Guestrin, “’Why should I trust you?’: Explaining the predictions of any classifier,” in Proc. ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Mining, 2016, pp. 1135-1144. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tsai, S. Bai, P. P. Liang, J. Z. Kolter, L. Morency, and R. Salakhutdinov, “Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences,” in Proc. Annu. Meet. Assoc. Comput. Linguist., 2019, pp. 6558-6569. [CrossRef]

- A. Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, J. Uszkoreit, L. Jones, A. N. Gomez, Ł. Kaiser, and I. Polosukhin, “Attention is all you need,” in Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., 2017, pp. 5998-6008.

- K. Xu, J. Ba, R. Kiros, K. Cho, A. Courville, R. Salakhudinov, R. Zemel, and Y. Bengio, “Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn., 2015, pp. 2048-2057.

- J. Johnson, B. Hariharan, L. van der Maaten, J. Hoffman, L. Fei-Fei, C. L. Zitnick, and R. Girshick, “Inferring and executing programs for visual reasoning,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Vis., 2017, pp. 2989-2998. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yang, D. Yang, C. Dyer, X. He, A. Smola, and E. Hovy, “Hierarchical attention networks for document classification,” in Proc. Conf. North Amer. Chapter Assoc. Comput. Linguist.: Human Lang. Technol., 2016, pp. 1480-1489. [CrossRef]

- A. Zadeh, M. Chen, S. Poria, E. Cambria, and L. Morency, “Tensor fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis,” in Proc. Conf. Empirical Methods Natural Lang. Process., 2017, pp. 1103-1114. [CrossRef]

- D. Gunning, “Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI),” Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), 2017.

| Construct | Definition | Mathematical Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Perception | Integration of information from multiple sensory channels | Φ(M) = f(m₁, m₂, …, mₙ) |

| Cross-Modal Attention | Weighting mechanism for modality importance | αᵢⱼ = exp(eᵢⱼ) / ∑ₖ₌₁ⁿ exp(eᵢₖ) |

| Knowledge Transfer | Reuse of learned representations across domains | T(Kₛ, Dₜ) → Kₜ |

| Interpretability | Capacity to explain system decisions in human terms |

| Task | Dataset | Size | Modalities | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scene Understanding | MultiScene-5K | 5,423 samples | Video, audio, text | Complex indoor and outdoor scenes with annotations |

| Collaborative Problem Solving | AI-Human-Collab | 824 sessions | Text, images, actions | Records of human-AI interactions on design tasks |

| Explainability Assessment | XAI-Bench | 2,150 samples | Mixed | Benchmark for assessing quality of AI explanations |

| Method | Accuracy (%) | F1-Score | Processing Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual-Only (ResNet) | 68.7 | 0.665 | 42 |

| Audio-Only (WaveNet) | 51.2 | 0.487 | 38 |

| Early Fusion | 76.4 | 0.752 | 87 |

| Late Fusion | 79.1 | 0.783 | 96 |

| MulT [14] | 82.3 | 0.815 | 124 |

| Our Approach | 87.5 | 0.864 | 115 |

| System | Task Completion Rate (%) | Avg. Completion Time (min) | User Satisfaction (1-5) | Trust Score (1-5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline AI | 64.7 | 18.3 | 3.2 | 2.8 |

| Explainable AI | 72.1 | 15.7 | 3.7 | 3.5 |

| Our System | 86.9 | 12.4 | 4.3 | 4.1 |

| System Configuration | Scene Understanding (Acc. %) | Collaboration (Completion %) | Explanation Quality (1-5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full System | 87.5 | 86.9 | 4.2 |

| w/o Cross-modal Attention | 79.6 (-7.9) | 82.3 (-4.6) | 4.0 (-0.2) |

| w/o Explanation Component | 86.8 (-0.7) | 71.5 (-15.4) | 1.8 (-2.4) |

| w/o Memory Systems | 81.2 (-6.3) | 79.7 (-7.2) | 3.7 (-0.5) |

| w/o Symbolic Reasoning | 85.3 (-2.2) | 74.8 (-12.1) | 3.2 (-1.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).