1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of deep learning across various sectors has highlighted the essential need for large, high-quality datasets to achieve top-tier model performance (LeCun, Bengio, & Hinton, 2015). These data-intensive models require vast amounts of information to identify complex patterns and generalize effectively to new data (Hei et al., 2025). However, obtaining real-world data is fraught with challenges, including data scarcity, high costs, and time-intensive processes for collection and annotation (Rolnick et al., 2019; Keskes and Nita, 2025). Additionally, stringent privacy regulations governing sensitive data—such as personal, health, and financial records—along with legal and ethical restrictions, create significant barriers (Veale & Binns, 2017). Real-world datasets may also contain algorithmic biases, further complicating their use (Barocas, Hardt, & Narayanan, 2019).

Synthetic data has emerged as a powerful solution to these challenges. By generating artificial datasets that replicate the statistical characteristics of real-world data, synthetic data addresses data shortages, mitigates privacy concerns, and reduces biases (Goncalves et al., 2020; Hei et al., 2025). It can be scaled and customized for balanced class representation, making it especially useful for handling imbalanced datasets and simulating rare or complex scenarios (Frid-Adar et al., 2018). These capabilities enhance model robustness and generalization in deep learning applications (Xu & Veeramachaneni, 2018).

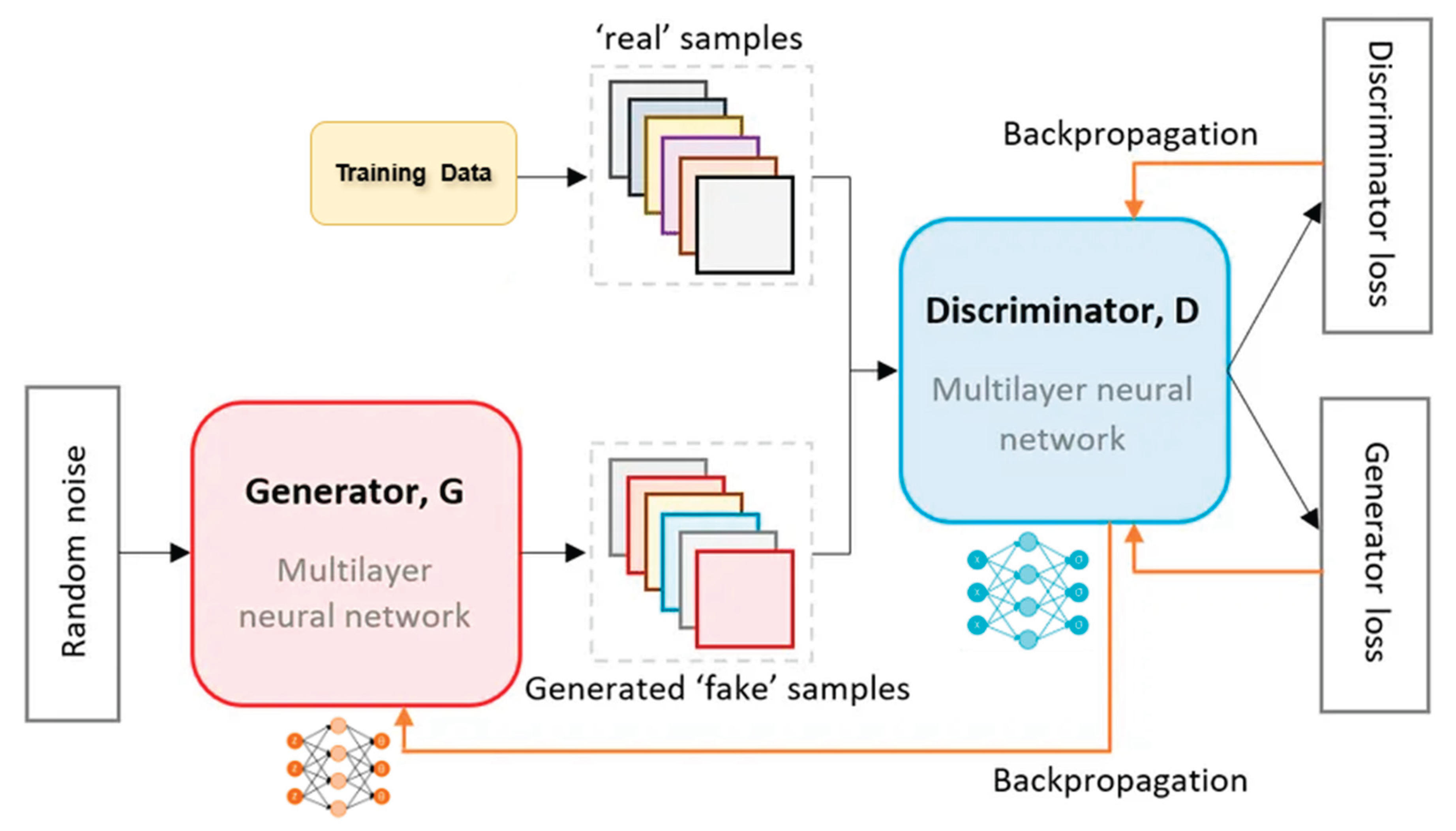

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have become a cornerstone in synthetic data generation, gaining widespread recognition for their effectiveness (Li et al., 2025). GANs utilize an adversarial training framework involving two neural networks: a generator and a discriminator (Wang et al., 2025). The generator learns the real data's underlying distribution to create synthetic samples that closely mimic it, while the discriminator works to distinguish real data from the generated samples (Chen et al., 2022). This adversarial interplay, resembling a zero-sum game, pushes the generator to continuously improve, producing increasingly realistic synthetic data. The iterative feedback loop between the two networks ensures refined outputs, capturing complex data distributions with high fidelity (Creswell et al., 2018; Gui et al., 2021).

Compared to traditional generative models, GANs excel in creating synthetic data that closely resembles real-world data (Goodfellow et al., 2014; Karras et al., 2019). A key advantage is that the generator does not directly access the original data during training, which reduces the risk of data disclosure and potential privacy breaches (Esteban et al., 2017). This makes GANs particularly valuable for applications requiring privacy preservation while maintaining the quality and utility of synthetic datasets (Li et al., 2025).

This review synthesizes current research on using GANs for synthetic data generation in deep learning. It explores GANs' core principles, applications across various fields, and advanced architectural innovations. The review compares GANs' strengths and limitations with other synthetic data generation methods and discusses quality assessment techniques. It provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and practitioners, highlighting challenges and future research directions in this rapidly evolving field.

2. Generative Adversarial Networks for Synthetic Data Generation: A Foundational Overview

A GAN consists of two opposing neural networks: the generator and the discriminator, both typically deep neural networks trained via backpropagation as shown in

Figure 1 (Goodfellow et al., 2014). The generator learns the probability distribution of real-world data to produce synthetic samples that mimic the original data (Keskes, 2025a). It takes a random noise vector, often drawn from a Gaussian or uniform distribution, as input and transforms it into synthetic outputs such as images, tabular data, or time-series sequences (Radford et al., 2016). The generator effectively learns a complex, non-linear mapping from a low-dimensional latent space to a higher-dimensional data space, generating new instances that are statistically similar to the training data (Li et al., 2025).

In contrast, the discriminator acts as a binary classifier, distinguishing real data samples from synthetic ones produced by the generator (Wang et al., 2025). It outputs a probability score indicating whether an input sample is real or fake, assigning high probabilities to real samples and low ones to synthetic ones (Hei et al., 2025). This classification provides critical feedback to the generator, enabling it to refine its outputs and improve realism through the adversarial learning process (Creswell et al., 2018).

GAN training is a competitive, zero-sum game. The generator aims to produce samples that fool the discriminator, while the discriminator strives to accurately classify real and fake samples (Li et al., 2025). Both networks are trained simultaneously in an iterative process: the discriminator improves its classification, and the generator refines its outputs to evade detection (Wang et al., 2022). This adversarial loop continues until equilibrium, where the discriminator cannot reliably distinguish synthetic samples from real data, indicating the generator has approximated the true data distribution effectively (Goodfellow, 2016; Creswell et al., 2018).

The adversarial training process in GANs can be formally represented as a minimax optimization problem (Wang et al., 2025). The objective function that governs this process typically involves the discriminator aiming to maximize the expected log-likelihood of correctly identifying real data and correctly identifying fake data (as fake). Simultaneously, the generator strives to minimize the expected log-likelihood of the discriminator correctly identifying its generated data as fake (Goodfellow et al., 2014). Mathematically, this can be expressed as:

where:

D(x) represents the discriminator's output (the probability that x is real) for a real data sample x drawn from the real data distribution

.

G(z) represents the generator's output (a synthetic data sample) for a random noise vector z drawn from a noise distribution .

D(G(z)) represents the discriminator's output for the synthetic sample G(z) (the probability that the synthetic sample is real).

E denotes the expected value.

The discriminator seeks to maximize this value function by correctly classifying both real and fake data. The generator, on the other hand, aims to minimize this value function by producing synthetic data G(z) that the discriminator is likely to classify as real (i.e., maximizing D(G(z)) or, equivalently, minimizing 1−D(G(z))). The equilibrium of this minimax game signifies that the generator has learned to produce synthetic data that is statistically indistinguishable from the real data (Goodfellow, 2016; Wang et al., 2025).

3. Applications Across Diverse Domains

The influence of GANs is expanding rapidly, transforming sectors such as healthcare, finance, computer vision, and natural language processing. In healthcare, GANs generate synthetic medical images such as MRI and CT scans, aiding in diagnosis, treatment planning, and data augmentation for deep learning models (Yi et al., 2019; Singh & Raza, 2021). They also enable data anonymization, addressing privacy concerns, with applications in brain imaging, cardiology, and oncology. For instance, models like medGAN generate synthetic electronic health records to alleviate data scarcity and preserve patient confidentiality (Armanious et al., 2020).

In finance, GANs produce synthetic time-series data such as stock prices for fraud detection, forecasting, and trading strategy development (Chen et al., 2022). TimeGAN is particularly effective at capturing temporal dependencies in financial data, enhancing risk modeling and algorithmic trading performance (Yoon, Jarrett, & van der Schaar, 2019). Similarly, FinGAN demonstrates GANs' capability in modeling complex financial distributions, supporting regulatory and market behavior analysis (Wiese et al., 2020).

Computer vision has been a primary driver of GAN advancement, with applications in synthetic image and video generation, 3D model creation, and data augmentation for classification and detection tasks (Goodfellow et al., 2014; Isola et al., 2017). GANs also facilitate image-to-image translation (e.g., changing weather or season), super-resolution, and artistic generation such as anime character synthesis or photo restoration (Karras et al., 2019).

In NLP, while GANs are less prevalent than in vision, they generate synthetic text for tasks like text summarization and translation and support creative applications like poetry or story generation (Yu et al., 2017). Though large language models dominate current NLP, GANs contribute to data augmentation and domain-specific text synthesis (Yu et al., 2017).

Beyond these, GANs are increasingly used in cybersecurity, fraud detection, and supply chain modeling. They generate synthetic fraudulent transactions or network traffic to improve model robustness and support imbalanced data training (Lin et al., 2020). Models like table-GAN (Park et al., 2018) and CTAB-GAN (Zhou et al., 2021) highlight GANs’ flexibility in structured data applications, underscoring their transformative potential across diverse fields.

4. Advanced GAN Architectures and Methodologies

Since the introduction of the original GAN framework, advanced architectures have been developed to overcome its limitations and enhance synthetic data generation (Gui et al., 2021). These innovations address diverse data types and applications, improving the quality and utility of generated data (Pan et al., 2019).

Deep Convolutional GANs (DCGANs) marked a significant advancement by integrating convolutional neural networks (CNNs) into the generator and discriminator (Zhang et al., 2017). This enabled DCGANs to synthesize realistic images by leveraging CNNs’ ability to learn hierarchical spatial features, as seen in applications like generating fashion images from the Fashion MNIST dataset (Isola et al., 2017). DCGANs set the stage for more sophisticated image synthesis models (Karras et al., 2018).

Conditional GANs (cGANs) introduced controlled generation by conditioning the process on additional information, such as class labels or textual descriptions (Reed et al., 2016). This allows targeted data synthesis, particularly in healthcare, where cGANs generate medical images for specific pathologies (Frid-Adar et al., 2018). CTAB-GAN, a conditional tabular GAN, applies this principle to structured data, enhancing realism in synthetic tabular datasets (Zhao et al., 2021).

CycleGANs facilitate unpaired image-to-image translation, learning mappings between domains without direct correspondences. Using cycle consistency loss, CycleGANs ensure reversible translations (Zhu et al., 2017), proving valuable in healthcare for tasks like transforming MRI contrasts without paired data, showcasing GANs’ ability to handle complex data mappings (Yang et al., 2020).

TimeGANs tackle time-series data generation, capturing temporal dependencies through a combination of supervised and unsupervised objectives. Applied to financial data like stock prices, TimeGAN outperforms alternatives by modeling realistic temporal dynamics, highlighting the need for specialized GAN designs for sequential data (Yoon et al., 2019).

Tabular GANs address the challenges of structured data, which mixes numerical and categorical variables. Models like medGAN, CTAB-GAN, and table-GAN enhance synthetic tabular data generation. MedGAN uses an autoencoder-GAN hybrid for electronic health records (Armanious et al., 2020), while CTAB-GAN and table-GAN incorporate classifiers to maintain semantic integrity (Majeed & Hwang, 2024). Table-GAN employs hinge loss and classification loss to balance privacy and compatibility, demonstrating effectiveness in generating realistic tabular data (Xu et al., 2019).

Training GANs requires careful optimization to overcome instability, vanishing gradients, and mode collapse. Strategies like hinge loss, gradient penalties, and hyperparameter tuning—such as adjusting epochs, batch sizes, and learning rates in FinGAN—stabilize training and improve outcomes (Xiaopeng et al., 2020). For instance, FinGAN’s adjustments enhanced its ability to capture complex financial patterns (Takahashi et al., 2019).

These advancements—DCGANs, cGANs, CycleGANs, TimeGANs, and tabular GANs—demonstrate the versatility of GANs in generating high-quality synthetic data across images, time-series, and structured datasets, with careful training ensuring their effectiveness in diverse applications (Creswell et al., 2018).

Table 1.

Comparative Table of GAN Architectures for Synthetic Data Generation.

Table 1.

Comparative Table of GAN Architectures for Synthetic Data Generation.

| Architecture |

Key Features |

Applications |

Limitations |

| DCGAN |

Incorporation of CNNs in generator and discriminator. |

Image synthesis, feature learning. |

Can still suffer from training instability and mode collapse. |

| cGAN |

Generation conditioned on additional input (e.g., labels, text). |

Controlled data generation, image editing, text-to-image synthesis. |

Requires labeled or conditional data. |

| CycleGAN |

Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle consistency loss. |

Style transfer, domain adaptation, image enhancement. |

Can sometimes produce geometrically inconsistent results. |

| TimeGAN |

Explicit modeling of temporal correlations for time-series data. |

Synthetic financial data, healthcare time-series data. |

Complexity in implementation and training. |

| medGAN |

Combines autoencoder with GAN for mixed-type data (binary, continuous). |

Synthetic electronic health records (EHR). |

Originally designed for binary and continuous data; extensions needed for multi-categorical data. |

| CTAB-GAN |

Conditional GAN with a classifier to learn data semantics for tabular data. |

Synthetic tabular data generation, handling mixed data types. |

Evaluation metrics for tabular data can be inconsistent.12

|

| table-GAN |

Adds a classifier network to enhance semantic integrity of synthetic tables. |

Synthetic tabular data generation, privacy preservation. |

Performance can vary across different datasets and may not always capture all statistical nuances.13

|

5. Advantages and Benefits of Using GANs for Synthetic Data

GANs offer significant advantages in synthetic data generation across various domains. A key benefit is addressing data scarcity by creating vast amounts of realistic synthetic data, augmenting limited real-world datasets (Guo et al., 2023). This is critical in fields like rare disease research or specialized industries where data collection is costly or challenging (Armanious et al., 2020). By generating diverse samples, GANs enable the training of robust deep learning models, reducing overfitting and improving generalization (Wang et al., 2025).

GANs also mitigate privacy risks by producing synthetic data that preserves the statistical properties of original datasets without exposing sensitive information. This facilitates data sharing and collaboration while complying with regulations like GDPR and HIPAA (Jordon et al., 2019). Models like table-GAN are designed to synthesize tabular data, minimizing disclosure risks, which is vital in sensitive sectors such as healthcare and finance (Park et al., 2018).

Additionally, GANs help address algorithmic bias in datasets. By generating synthetic data to balance imbalanced classes or represent underrepresented groups, GANs support the development of fairer machine learning models (Xu et al., 2020). This is crucial for preventing AI systems from perpetuating societal biases, ensuring more equitable outcomes.

Synthetic data from GANs enhances model robustness and generalization by exposing models to a wider range of scenarios, including rare or complex cases do not present in real data. This makes models more resilient to variations and noise, improving performance on unseen data. For example, GANs can simulate challenging conditions, enabling models to handle diverse real-world inputs effectively (Shmelkov et al., 2018).

Finally, GANs offer cost and time efficiency compared to collecting and processing real-world data. Once trained, GANs can quickly generate large volumes of synthetic data, accelerating the development and deployment of deep learning models (Torfi et al., 2020). This efficiency, combined with their ability to overcome data limitations, privacy concerns, and biases, makes GANs a transformative tool for advancing AI applications.

6. Challenges, Limitations, and Considerations

Despite the numerous advantages of using GANs for synthetic data generation, several challenges, limitations, and considerations need to be carefully addressed. One major issue is the instability of the training process, often requiring extensive hyperparameter tuning and sophisticated architectural design to achieve convergence (Keskes, 2025b). Mode collapse, where the generator produces limited sample variety, further complicates capturing the full diversity of real data, reducing the utility of synthetic data (Srivastava et al., 2017). Advanced training techniques and careful monitoring are essential to mitigate these issues.

Another limitation is the lack of standardized evaluation metrics to assess synthetic data quality and utility. Existing metrics often focus on specific aspects, like visual fidelity, but fail to capture the data’s usefulness for downstream tasks or preservation of complex relationships, hindering model comparisons (Borji, 2019). The high computational cost of training GANs, requiring powerful GPUs and significant time, poses a barrier for those with limited resources (Lucic et al., 2018).

Privacy concerns arise when generators memorize training data patterns, risking information leakage. Balancing privacy and utility require ongoing research into privacy-preserving techniques (Chen et al., 2020). Additionally, the ability of GANs to create realistic synthetic data raises ethical concerns, including the potential for deepfakes and misinformation (Westerlund, 2019). Addressing these risks demands ethical guidelines, responsible data practices, and robust detection mechanisms to maintain trust in information sources.

7. GANs in Comparison to Other Synthetic Data Generation Techniques

The Generative Adversarial Networks are not the sole method for synthetic data generation; other techniques like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Large Language Models (LLMs), and traditional statistical methods also play significant roles. VAEs, which encode data into a probabilistic latent space and decode it to generate new samples, offer greater training stability than GANs but often produce less realistic outputs, especially for complex data like images (Kingma & Welling, 2014). Both GAN-based (e.g., CTGAN) and VAE-based (e.g., TVAE) models are popular for tabular data (Majeed & Hwang, 2024).

LLMs excel in generating coherent, contextually relevant synthetic text, leveraging their training on vast text corpora, but are less versatile for structured data like images or tables compared to GANs (Miletic & Sariyar, 2024). Traditional statistical methods, which model data properties like means and correlations, are computationally lighter and suitable for simpler tasks but struggle to capture complex, high-dimensional patterns (Du et al., 2024). These methods often require more manual domain expertise, unlike the automated learning of GANs. While GANs provide a strong balance of realism and fidelity for complex data like images and time-series, the choice of technique depends on application needs, data type, and trade-offs in training stability, computational cost, and data realism Miletic & Sariyar, 2024; Deng & Chen, 2024).

8. Conclusion

As a breakthrough in synthetic data generation, GANs produce highly realistic datasets, driving advancements in healthcare, finance, computer vision, and natural language processing. Their adversarial training process enables them to tackle data scarcity, mitigate privacy risks, and reduce algorithmic bias, advancing AI applications. However, challenges such as training instability, the lack of robust evaluation metrics, and ethical concerns persist. Ongoing research focuses on developing advanced GAN architectures, refining training techniques, and establishing standardized evaluation methods to address these issues. As these efforts progress, GANs promise to enhance data sharing, model development, and the creation of fair, privacy-preserving, and robust deep learning solutions, with future improvements targeting stability, efficiency, controllability, and ethical deployment.

References

- Armanious, K.; Jiang, C.; Fischer, M.; Küstner, T.; Hepp, T.; Nikolaou, K.; Gatidis, S.; Yang, B. MedGAN: Medical image translation using GANs. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2020, 79, 101684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, X.; Cao, J.; Yuqin, L.; Dai, Q. Improved training of spectral normalization generative adversarial networks. 2020 2nd World Symposium on Artificial Intelligence (WSAI); IEEE, 2020; pp. 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, X.-H.; Wei, Z.; Heidari, A.A.; Zheng, N.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Hu, H.; Zhou, Q.; Guan, Q. Generative adversarial networks in medical image augmentation: A review. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 144, 105382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, A.; White, T.; Dumoulin, V.; Arulkumaran, K.; Sengupta, B.; Bharath, A.A. Generative adversarial networks: An overview. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2018, 35, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Chen, L. CDGFD: Cross-domain generalization in ethnic fashion design using LLMs and GANs: A symbolic and geometric approach. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 7192–7207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Luo, D.; Yan, R.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhu, H.; Song, Y.; Zhang, J. Enhancing job recommendation through LLM-based generative adversarial networks. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024, 38, 8363–8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, C.; Hyland, S.L.; Rätsch, G. Real-valued (medical) time series generation with recurrent conditional GANs. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.02633. [Google Scholar]

- Frid-Adar, M.; Diamant, I.; Klang, E.; Amitai, M.; Goldberger, J.; Greenspan, H. GAN-based synthetic medical image augmentation for improved CNN performance in liver lesion classification. Neurocomputing 2018, 321, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frid-Adar, M.; Klang, E.; Amitai, M.; Goldberger, J.; Greenspan, H. Synthetic data augmentation using GAN for improved liver lesion classification. Neurocomputing 2018, 321, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, A.; Ray, P.; Soper, B.; Stevens, J.; Coyle, L.; Sales, A.P. Generation and evaluation of synthetic patient data. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2020, 20, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I. NIPS 2016 tutorial: Generative adversarial networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1701.00160. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2014; Volume 27, pp. 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Communications of the ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, J.; Sun, Z.; Wen, Y.; Tao, D.; Ye, J. A review on generative adversarial networks: Algorithms, theory, and applications. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2021, 35, 3313–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Chen, J.; Qiu, T.; Guo, S.; Luo, T.; Chen, T.; Ren, S. MedGAN: An adaptive GAN approach for medical image generation. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2023, 163, 107119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hei, Z.; Sun, W.; Yang, H.; Zhong, M.; Li, Y.; Kumar, A.; Xiang, J.; Zhou, Y. Novel domain-adaptive Wasserstein generative adversarial networks for early bearing fault diagnosis under various conditions. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2025, 257, 110847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.E.; Srivastava, N.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Improving neural networks by preventing co-adaptation of feature detectors. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1207.0580. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE, 2017; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, T.; Aila, T.; Laine, S.; Lehtinen, J. Progressive growing of GANs for improved quality, stability, and variation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1710.10196. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aila, T. A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE, 2019; pp. 4401–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskes, M.I. Review of The Current State of Deep Learning Applications in Agriculture. Preprints 2025a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskes, M.I. Review of the current state of deep learning applications in agriculture. Preprints 2025b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskes, M.I.; Nita, M.D. Developing an AI tool for forest monitoring: Introducing SylvaMind AI. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov. Series II: Forestry • Wood Industry • Agricultural Food Engineering 2024, 17, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational Bayes. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Bai, F.; Lyu, C.; Qu, X.; Liu, Y. A systematic review of generative adversarial networks for traffic state prediction: Overview, taxonomy, and future prospects. Information Fusion 2025, 117, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, C. IDSGAN: Generative adversarial networks for attack generation against intrusion detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 75828–75840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.; Hwang, S.O. Moving conditional GAN close to data: Synthetic tabular data generation and its experimental evaluation. IEEE Transactions on Big Data 2024. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miletic, M.; Sariyar, M. Assessing the potentials of LLMs and GANs as state-of-the-art tabular synthetic data generation methods. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer, 2024; Vol. 14975, pp. 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Yu, W.; Yi, X.; Khan, A.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, Y. Recent progress on generative adversarial networks (GANs): A survey. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 36322–36333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.; Mohammadi, M.; Gorde, K.; Jajodia, S.; Park, H.; Kim, Y. Data synthesis based on generative adversarial networks. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 2018, 11, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Metz, L.; Chintala, S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1511.06434. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, S.; Akhtar, Z.; Yan, X.; Du, L.; Chintala, S. Generative adversarial text to image synthesis. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2016; pp. 1060–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.K.; Raza, K. Medical image generation using generative adversarial networks: A review. In Studies in Computational Intelligence; Springer, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Chen, Y.; Tanaka-Ishii, K. Modeling financial time-series with generative adversarial networks. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2019, 527, 121261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Qin, X.; Song, F.; Cheng, L. Stabilizing training of generative adversarial nets via Langevin Stein variational gradient descent. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022, 33, 2768–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, H.; Mu, M.; Dong, Y. A trackable multi-domain collaborative generative adversarial network for rotating machinery fault diagnosis. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2025, 224, 111950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, M.; Knobloch, R.; Korn, R.; Kretschmer, T. Quant GANs: Deep generation of financial time series. Quantitative Finance 2020, 20, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Veeramachaneni, K. Synthesizing tabular data using generative adversarial networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.11264. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Li, N.; Zhao, Z.; Fan, X.; Chang, E.I.; Xu, Y. MRI cross-modality image-to-image translation. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.; Jarrett, D.; van der Schaar, M. Time-series generative adversarial networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); 2019; Volume 32, pp. 5508–5518. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y. SeqGAN: Sequence generative adversarial nets with policy gradient. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2017; p. 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Metaxas, D.N. StackGAN: Text to photo-realistic image synthesis with stacked generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE, 2017; pp. 5907–5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Kunar, A.; Birke, R.; Chen, L.Y. CTAB-GAN: Effective table data synthesizing. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.07669. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, L.; Fan, Y. CTAB-GAN: Effective table data synthesizing. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.01906. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE, 2017; pp. 2223–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).