Submitted:

10 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Gene Therapy Era and Lentiviral Vectors

2. Clinical Use of Lentiviral Vectors

3. The Derivation of Lentiviral Vectors

4. Current Issues and Development of Next-Generation Lentiviral Vectors

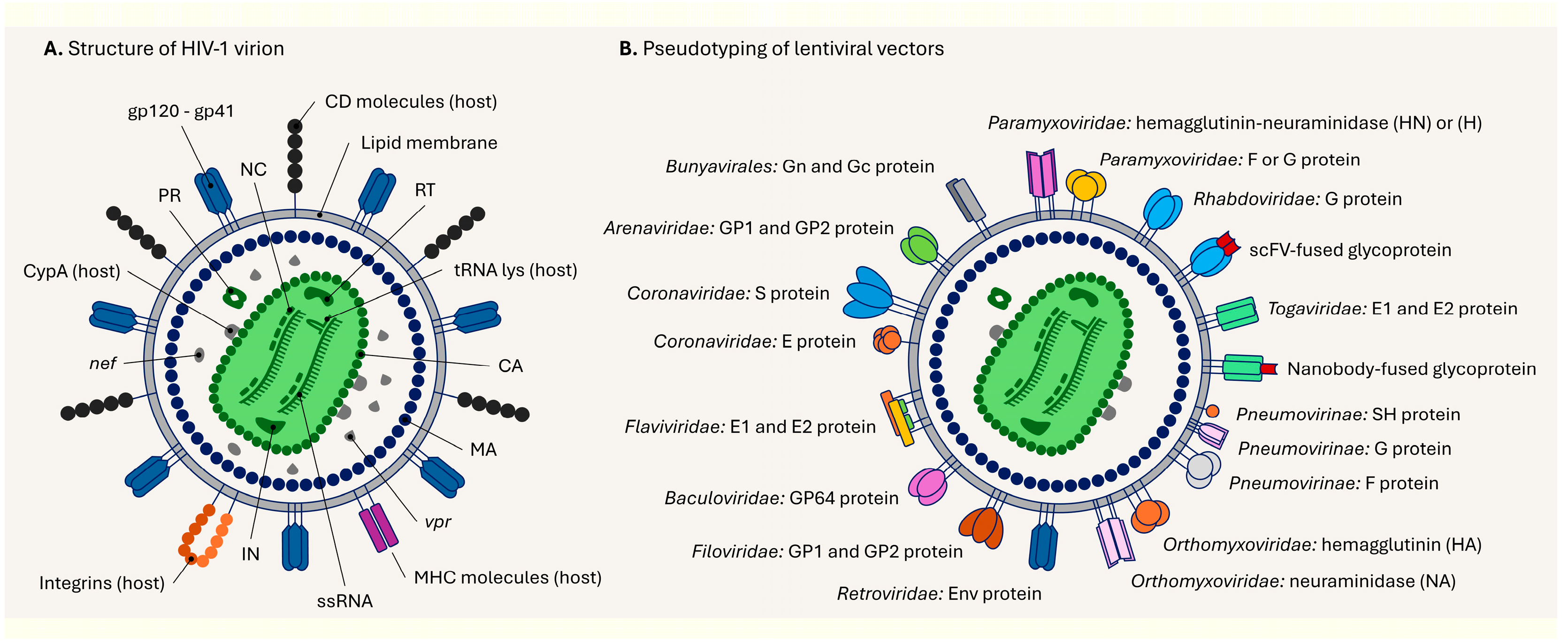

5. Structure of the Lentiviral Particle and Its Pseudotyping

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus |

| Ad | Adenovirus |

| ADA | Adenosine deaminase |

| ADA-SCID | Severe combined immunodeficiency due to the adenosine deaminase deficiency |

| AFP | Alpha-fetoprotein |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| AMD | Age-related macular degeneration |

| ASO | Antisense oligonucleotides |

| BCMA | B-cell maturation antigen |

| CA | Capsid |

| CALD | Cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| Cas | CRISPR-associated protein |

| CFTR | Cystic fibrosis membrane conductance regulator |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| cPPT/CTS | Central polypurine tract/central termination sequence |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| F | Fusion |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HBB | Hemoglobin subunit beta |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HN | Hemagglutinin-neuraminidase |

| HSCs | Hematopoietic stem cells |

| HSV | Herpes Simplex Virus |

| IL2RG | Interleukin 2 receptor subunit gamma |

| IN | Integrase |

| LTR | Long terminal repeat |

| MA | Matrix |

| MAGE-A4 | Melanoma antigen gene A4 |

| MERS-CoV | Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus |

| MESO | Mesothelin |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| MLD | Metachromatic leukodystrophy |

| MLV | Murine leukemia virus |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| NC | Nucleocapsid |

| NY-ESO-1 | New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma |

| OTC | Ornithine transcarbamylase |

| PR | Protease |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RRE | Rev response element |

| RT | Reverse-transcriptase |

| SARS-CoV | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus |

| scFV | Single-chain variable fragment |

| SeV | Sendai virus |

| sgRNA | single guide RNA |

| shRNA | short hairpin RNA |

| SIN-LTR | Self-inactivating LTR |

| SIV | Simian immunodeficiency virus |

| ssRNA | single-stranded RNA |

| TALEN | Transcription activator-like effector nuclease |

| TCR | T-cell receptor |

| TRE | Tetracycline response element |

| vgRNA | viral genomic RNA |

| vRNA | viral RNA |

| VSV-G | Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G |

| WAS | Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome |

| WPRE | Woodchuck Hepatitis Virus Post-Transcriptional Regulatory Element |

| X-SCID | X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency |

| ZNF | Zinc-finger nuclease |

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Long Term Follow-Up After Administration of Human Gene Therapy Products Guidance for Industry https://www.fda.gov/media/113768/download (accessed Jan 28, 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on the quality, non-clinical and clinical aspects of gene therapy medicinal products https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-quality-non-clinical-and-clinical-aspects-gene-therapy-medicinal-products_en.pdf (accessed Jan 28, 2025).

- Rosenberg, S. A.; Aebersold, P.; Cornetta, K.; Kasid, A.; Morgan, R. A.; Moen, R.; Karson, E. M.; Lotze, M. T.; Yang, J. C.; Topalian, S. L.; et al. Gene Transfer into Humans — Immunotherapy of Patients with Advanced Melanoma, Using Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Modified by Retroviral Gene Transduction. N. Engl. J. Med., 1990, 323, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedmann, T. A Brief History of Gene Therapy. Nat. Genet., 1992, 2, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, T.; Parker, N.; Ylä-Herttuala, S. History of Gene Therapy. Gene, 2013, 525, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landhuis, E. The Definition of Gene Therapy Has Changed. Nature, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Blaese, R. M.; Culver, K. W.; Miller, A. D.; Carter, C. S.; Fleisher, T.; Clerici, M.; Shearer, G.; Chang, L.; Chiang, Y.; Tolstoshev, P.; et al. T Lymphocyte-Directed Gene Therapy for ADA − SCID: Initial Trial Results After 4 Years. Science (80-. )., 1995, 270, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muul, L. M. Persistence and Expression of the Adenosine Deaminase Gene for 12 Years and Immune Reaction to Gene Transfer Components: Long-Term Results of the First Clinical Gene Therapy Trial. Blood, 2003, 101, 2563–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplen, N. J.; Alton, E. W. F. W.; Mddleton, P. G.; Dorin, J. R.; Stevenson, B. J.; Gao, X.; Durham, S. R.; Jeffery, P. K.; Hodson, M. E.; Coutelle, C.; et al. Liposome-Mediated CFTR Gene Transfer to the Nasal Epithelium of Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Nat. Med., 1995, 1, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabner, J.; Cheng, S. H.; Meeker, D.; Launspach, J.; Balfour, R.; Perricone, M. A.; Morris, J. E.; Marshall, J.; Fasbender, A.; Smith, A. E.; et al. Comparison of DNA-Lipid Complexes and DNA Alone for Gene Transfer to Cystic Fibrosis Airway Epithelia in Vivo. J. Clin. Invest., 1997, 100, 1529–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, R. G.; McElvaney, N. G.; Rosenfeld, M. A.; Chu, C.-S.; Mastrangeli, A.; Hay, J. G.; Brody, S. L.; Jaffe, H. A.; Eissa, N. T.; Danel, C. Administration of an Adenovirus Containing the Human CFTR CDNA to the Respiratory Tract of Individuals with Cystic Fibrosis. Nat. Genet., 1994, 8, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellon, G.; Michel-Calemard, L.; Thouvenot, D.; Jagneaux, V.; Poitevin, F.; Malcus, C.; Accart, N.; Layani, M. P.; Aymard, M.; Bernon, H.; et al. Aerosol Administration of a Recombinant Adenovirus Expressing CFTR to Cystic Fibrosis Patients: A Phase I Clinical Trial. Hum. Gene Ther., 1997, 8, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flotte, T.; Carter, B.; Conrad, C.; Guggino, W.; Reynolds, T.; Rosenstein, B.; Taylor, G.; Walden, S.; Wetzel, R. A Phase I Study of an Adeno-Associated Virus-CFTR Gene Vector in Adult CF Patients with Mild Lung Disease. Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, Baltimore, Maryland. Hum. Gene Ther., 1996, 7, 1145–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virella-Lowell, I.; Poirier, A.; Chesnut, K. A.; Brantly, M.; Flotte, T. R. Inhibition of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus (RAAV) Transduction by Bronchial Secretions from Cystic Fibrosis Patients. Gene Ther., 2000, 7, 1783–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasbender, A.; Zabner, J.; Zeiher, B.; Welsh, M. A Low Rate of Cell Proliferation and Reduced DNA Uptake Limit Cationic Lipid-Mediated Gene Transfer to Primary Cultures of Ciliated Human Airway Epithelia. Gene Ther., 1997, 4, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, M. R.; Hohneker, K. W.; Zhou, Z.; Olsen, J. C.; Noah, T. L.; Hu, P.-C.; Leigh, M. W.; Engelhardt, J. F.; Edwards, L. J.; Jones, K. R.; et al. A Controlled Study of Adenoviral-Vector–Mediated Gene Transfer in the Nasal Epithelium of Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med., 1995, 333, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raper, S. E.; Chirmule, N.; Lee, F. S.; Wivel, N. A.; Bagg, A.; Gao, G.; Wilson, J. M.; Batshaw, M. L. Fatal Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome in a Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficient Patient Following Adenoviral Gene Transfer. Mol. Genet. Metab., 2003, 80, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina, S.; von Kalle, C.; Schmidt, M.; Le Deist, F.; Wulffraat, N.; McIntyre, E.; Radford, I.; Villeval, J.-L.; Fraser, C. C.; Cavazzana-Calvo, M.; et al. A Serious Adverse Event after Successful Gene Therapy for X-Linked Severe Combined Immunodeficiency. N. Engl. J. Med., 2003, 348, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina, S.; Von Kalle, C.; Schmidt, M.; McCormack, M. P.; Wulffraat, N.; Leboulch, P.; Lim, A.; Osborne, C. S.; Pawliuk, R.; Morillon, E.; et al. LMO2 -Associated Clonal T Cell Proliferation in Two Patients after Gene Therapy for SCID-X1. Science (80-. )., 2003, 302, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina, S.; Garrigue, A.; Wang, G. P.; Soulier, J.; Lim, A.; Morillon, E.; Clappier, E.; Caccavelli, L.; Delabesse, E.; Beldjord, K.; et al. Insertional Oncogenesis in 4 Patients after Retrovirus-Mediated Gene Therapy of SCID-X1. J. Clin. Invest., 2008, 118, 3132–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, M. L.; Abedi, M. R.; Wixon, J. Gene Therapy Clinical Trials Worldwide to 2007—an Update. J. Gene Med., 2007, 9, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, T. The Road toward Human Gene Therapy-A 25-Year Perspective. Ann. Med., 1997, 29, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, C. E.; High, K. A.; Joung, J. K.; Kohn, D. B.; Ozawa, K.; Sadelain, M. Gene Therapy Comes of Age. Science (80-. )., 2018, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dropulic, B.; Humeau, L.; Slepushkin, V.; Lu, X.; Manilla, P.; Rebello, T.; Afable, C.; Lacy, K.; Ybarra, C.; Levine, B.; et al. Establishing Safety in the Clinic for the First Lentiviral Vector To Be Tested in Humans. Blood, 2004, 104, 411–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattoglio, C.; Pellin, D.; Rizzi, E.; Maruggi, G.; Corti, G.; Miselli, F.; Sartori, D.; Guffanti, A.; Di Serio, C.; Ambrosi, A.; et al. High-Definition Mapping of Retroviral Integration Sites Identifies Active Regulatory Elements in Human Multipotent Hematopoietic Progenitors. Blood, 2010, 116, 5507–5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippe, S.; Sarkis, C.; Barkats, M.; Mammeri, H.; Ladroue, C.; Petit, C.; Mallet, J.; Serguera, C. Lentiviral Vectors with a Defective Integrase Allow Efficient and Sustained Transgene Expression in Vitro and in Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 2006, 103, 17684–17689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N. M.; Alvarado, A. F.; Moffatt, T. N.; Edavettal, J. M.; Swaminathan, T. A.; Braun, S. E. HIV-Based Lentiviral Vectors: Origin and Sequence Differences. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev., 2021, 21, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J. H.; Mikkelsen, J. G. Delivering Genes with Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Derived Vehicles: Still State-of-the-Art after 25 Years. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022 291, 2022, 29, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braendstrup, P.; Levine, B. L.; Ruella, M. The Long Road to the First FDA-Approved Gene Therapy: Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Targeting CD19. Cytotherapy, 2020, 22, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J. C.; Polineni, D.; Boyd, A. C.; Donaldson, S.; Gill, D. R.; Griesenbach, U.; Hyde, S. C.; Jain, R.; McLachlan, G.; Mall, M. A.; et al. Lentiviral Gene Therapy for Cystic Fibrosis: A Promising Approach and First-in-Human Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med., 2024, 210, 1398–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Iida, A.; Ueda, Y.; Hasegawa, M. Pseudotyped Lentivirus Vectors Derived from Simian Immunodeficiency Virus SIVagm with Envelope Glycoproteins from Paramyxovirus. J. Virol., 2003, 77, 2607–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, R. J.; Coradin, T.; Nimmo, R.; Lad, Y.; Hyde, S. C.; Mitrophanos, K.; Gill, D. R. Sendai F/HN Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vector Transduces Human Ciliated and Non-Ciliated Airway Cells Using α 2,3 Sialylated Receptors. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev., 2022, 26, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-H.; Gessler, D. J.; Zhan, W.; Gallagher, T. L.; Gao, G. Adeno-Associated Virus as a Delivery Vector for Gene Therapy of Human Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther., 2024, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, R. F.; Driver, V. B.; Tanaka, K.; Crooke, R. M.; Anderson, K. P. Antiviral Activity of a Phosphorothioate Oligonucleotide Complementary to RNA of the Human Cytomegalovirus Major Immediate-Early Region. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 1993, 37, 1945–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Zhong, L.; Weng, Y.; Peng, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, X.-J. Therapeutic SiRNA: State of the Art. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther., 2020, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauffer, M. C.; van Roon-Mom, W.; Aartsma-Rus, A. Possibilities and Limitations of Antisense Oligonucleotide Therapies for the Treatment of Monogenic Disorders. Commun. Med., 2024, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, S.; Boggavarapu, R.; Cohen, N. R.; Zhang, Y.; Sharma, I.; Zeheb, L.; Mukund Acharekar, N.; Rodgers, H. D.; Islam, S.; Pitts, J.; et al. Structure of Anellovirus-like Particles Reveal a Mechanism for Immune Evasion. Nat. Commun., 2024, 15, 7219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebas, P.; Stein, D.; Tang, W. W.; Frank, I.; Wang, S. Q.; Lee, G.; Spratt, S. K.; Surosky, R. T.; Giedlin, M. A.; Nichol, G.; et al. Gene Editing of CCR5 in Autologous CD4 T Cells of Persons Infected with HIV. N. Engl. J. Med., 2014, 370, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Lee, Y.-K.; Schaefer, E. A. K.; Peters, D. T.; Veres, A.; Kim, K.; Kuperwasser, N.; Motola, D. L.; Meissner, T. B.; Hendriks, W. T.; et al. A TALEN Genome-Editing System for Generating Human Stem Cell-Based Disease Models. Cell Stem Cell, 2013, 12, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, W.; Amrolia, P. J.; Samarasinghe, S.; Ghorashian, S.; Zhan, H.; Stafford, S.; Butler, K.; Ahsan, G.; Gilmour, K.; Adams, S.; et al. First Clinical Application of Talen Engineered Universal CAR19 T Cells in B-ALL. Blood, 2015, 126, 2046–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, F. A.; Hsu, P. D.; Wright, J.; Agarwala, V.; Scott, D. A.; Zhang, F. Genome Engineering Using the CRISPR-Cas9 System. Nat. Protoc., 2013, 8, 2281–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komor, A. C.; Kim, Y. B.; Packer, M. S.; Zuris, J. A.; Liu, D. R. Programmable Editing of a Target Base in Genomic DNA without Double-Stranded DNA Cleavage. Nature, 2016, 533, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A. V.; Randolph, P. B.; Davis, J. R.; Sousa, A. A.; Koblan, L. W.; Levy, J. M.; Chen, P. J.; Wilson, C.; Newby, G. A.; Raguram, A.; et al. Search-and-Replace Genome Editing without Double-Strand Breaks or Donor DNA. Nature, 2019, 576, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmore-Harris, C.; Fruhwirth, G. O. The Clinical Potential of Gene Editing as a Tool to Engineer Cell-based Therapeutics. Clin. Transl. Med., 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Xue, J.; Deng, T.; Zhou, X.; Yu, K.; Deng, L.; Huang, M.; Yi, X.; Liang, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Safety and Feasibility of CRISPR-Edited T Cells in Patients with Refractory Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Nat. Med., 2020, 26, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippidis, A. CASGEVY Makes History as FDA Approves First CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Edited Therapy. Hum. Gene Ther., 2024, 35, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudno, J. N.; Maus, M. V.; Hinrichs, C. S. CAR T Cells and T-Cell Therapies for Cancer. JAMA, 2024, 332, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, C. A.; Harper, J. C.; Carney, J. P.; Timlin, J. A. Delivering CRISPR: A Review of the Challenges and Approaches. Drug Deliv., 2018, 25, 1234–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. G.; Dang, Y.; Abraham, S.; Ma, H.; Zhang, J.; Guo, H.; Cai, Y.; Mikkelsen, J. G.; Wu, H.; Shankar, P.; et al. Lentivirus Pre-Packed with Cas9 Protein for Safer Gene Editing. Gene Ther., 2016, 23, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, N.; Drysdale, C. M.; Nassehi, T.; Gamer, J.; Yapundich, M.; DiNicola, J.; Shibata, Y.; Hinds, M.; Gudmundsdottir, B.; Haro-Mora, J. J.; et al. Cas9 Protein Delivery Non-Integrating Lentiviral Vectors for Gene Correction in Sickle Cell Disease. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev., 2021, 21, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjana, N. E.; Shalem, O.; Zhang, F. Improved Vectors and Genome-Wide Libraries for CRISPR Screening. Nat. Methods, 2014, 11, 783–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Bak, R. O.; Krogh, L. B.; Staunstrup, N. H.; Moldt, B.; Corydon, T. J.; Schrøder, L. D.; Mikkelsen, J. G. DNA Transposition by Protein Transduction of the PiggyBac Transposase from Lentiviral Gag Precursors. Nucleic Acids Res., 2014, 42, e28–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Bak, R. O.; Mikkelsen, J. G. Targeted Genome Editing by Lentiviral Protein Transduction of Zinc-Finger and TAL-Effector Nucleases. Elife, 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strebinger, D.; Frangieh, C. J.; Friedrich, M. J.; Faure, G.; Macrae, R. K.; Zhang, F. Cell Type-Specific Delivery by Modular Envelope Design. Nat. Commun., 2023, 14, 5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Wei, L.; Chen, Y. From Bench to Bedside: Developing CRISPR/Cas-Based Therapy for Ocular Diseases. Pharmacol. Res., 2025, 213, 107638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, I. M.; Weitzman, M. D. GENE THERAPY: Twenty-First Century Medicine. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 2005, 74, 711–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Du, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhai, Z.; Pan, J. GTO: A Comprehensive Gene Therapy Omnibus. Nucleic Acids Res., 2025, 53, D1393–D1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, R. R. Clinical Protocol. A Phase 1 Open-Label Clinical Trial of the Safety and Tolerability of Single Escalating Doses of Autologous CD4 T Cells Transduced with VRX496 in HIV-Positive Subjects. Hum. Gene Ther., 2001, 12, 2028–2029. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, B. L.; Humeau, L. M.; Boyer, J.; MacGregor, R. R.; Rebello, T.; Lu, X.; Binder, G. K.; Slepushkin, V.; Lemiale, F.; Mascola, J. R.; et al. Gene Transfer in Humans Using a Conditionally Replicating Lentiviral Vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 2006, 103, 17372–17377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarrity, G. J.; Hoyah, G.; Winemiller, A.; Andre, K.; Stein, D.; Blick, G.; Greenberg, R. N.; Kinder, C.; Zolopa, A.; Binder-Scholl, G.; et al. Patient Monitoring and Follow-up in Lentiviral Clinical Trials. J. Gene Med., 2013, 15, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.-L.; Hua, Z.-C. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell (CAR T) Therapy for Hematologic and Solid Malignancies: Efficacy and Safety—A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel)., 2019, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-J.; Liu, C.; Hu, S.-Z.; Yuan, Z.-Y.; Ni, H.-Y.; Sun, S.-J.; Hu, C.-Y.; Zhan, H.-Q. Application of CAR-T Cell Therapy in B-Cell Lymphoma: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Transl. Oncol., 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yarza, R.; Bover, M.; Herrera-Juarez, M.; Rey-Cardenas, M.; Paz-Ares, L.; Lopez-Martin, J. A.; Haanen, J. Efficacy of T-Cell Receptor-Based Adoptive Cell Therapy in Cutaneous Melanoma: A Meta-Analysis. Oncologist, 2023, 28, e406–e415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, G.; Waks, T.; Eshhar, Z. Expression of Immunoglobulin-T-Cell Receptor Chimeric Molecules as Functional Receptors with Antibody-Type Specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 1989, 86, 10024–10028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüthmann, H.; Kisielow, P.; Uematsu, Y.; Malissen, M.; Krimpenfort, P.; Berns, A.; von Boehmer, H.; Steinmetz, M. T-Cell-Specific Deletion of T-Cell Receptor Transgenes Allows Functional Rearrangement of Endogenous α- and β-Genes. Nature, 1988, 334, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, P.; Hui, H. Y. L.; Brownrigg, L. M.; Fuller, K. A.; Erber, W. N. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cells: Properties, Production, and Quality Control. Int. J. Lab. Hematol., 2023, 45, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blache, U.; Popp, G.; Dünkel, A.; Koehl, U.; Fricke, S. Potential Solutions for Manufacture of CAR T Cells in Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat. Commun., 2022, 13, 5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- June, C. H.; O’Connor, R. S.; Kawalekar, O. U.; Ghassemi, S.; Milone, M. C. CAR T Cell Immunotherapy for Human Cancer. Science (80-. )., 2018, 359, 1361–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golikova, E. A.; Alshevskaya, A. A.; Alrhmoun, S.; Sivitskaya, N. A.; Sennikov, S. V. TCR-T Cell Therapy: Current Development Approaches, Preclinical Evaluation, and Perspectives on Regulatory Challenges. J. Transl. Med., 2024, 22, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, P. F.; Kassim, S. H.; Tran, T. L. N.; Crystal, J. S.; Morgan, R. A.; Feldman, S. A.; Yang, J. C.; Dudley, M. E.; Wunderlich, J. R.; Sherry, R. M.; et al. A Pilot Trial Using Lymphocytes Genetically Engineered with an NY-ESO-1-Reactive T-Cell Receptor: Long-Term Follow-up and Correlates with Response. Clin. Cancer Res., 2015, 21, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D. S.; Van Tine, B. A.; Biswas, S.; McAlpine, C.; Johnson, M. L.; Olszanski, A. J.; Clarke, J. M.; Araujo, D.; Blumenschein, G. R.; Kebriaei, P.; et al. Autologous T Cell Therapy for MAGE-A4+ Solid Cancers in HLA-A*02+ Patients: A Phase 1 Trial. Nat. Med., 2023, 29, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandora, K.; Chandora, A.; Saeed, A.; Cavalcante, L. Adoptive T Cell Therapy Targeting MAGE-A4. Cancers (Basel)., 2025, 17, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, M.; Goksu, S. Y.; Akagunduz, B.; George, A.; Sahin, I. Adoptive Cell Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Review of Clinical Trials. Cancers (Basel)., 2023, 15, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Butler, M.; O’Cearbhaill, R. E.; Oh, D. Y.; Johnson, M.; Zikaras, K.; Smalley, M.; Ross, M.; Tanyi, J. L.; Ghafoor, A.; et al. Mesothelin-Targeting T Cell Receptor Fusion Construct Cell Therapy in Refractory Solid Tumors: Phase 1/2 Trial Interim Results. Nat. Med., 2023, 29, 2099–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, S. J.; Bishop, M. R.; Tam, C. S.; Waller, E. K.; Borchmann, P.; McGuirk, J. P.; Jäger, U.; Jaglowski, S.; Andreadis, C.; Westin, J. R.; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med., 2019, 380, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, F. L.; Miklos, D. B.; Jacobson, C. A.; Perales, M.-A.; Kersten, M.-J.; Oluwole, O. O.; Ghobadi, A.; Rapoport, A. P.; McGuirk, J.; Pagel, J. M.; et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med., 2022, 386, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Jain, P.; Locke, F. L.; Maurer, M. J.; Frank, M. J.; Munoz, J. L.; Dahiya, S.; Beitinjaneh, A. M.; Jacobs, M. T.; Mcguirk, J. P.; et al. Brexucabtagene Autoleucel for Relapsed or Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma in Standard-of-Care Practice: Results From the US Lymphoma CAR T Consortium. J. Clin. Oncol., 2023, 41, 2594–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J. S.; Solomon, S. R.; Arnason, J.; Johnston, P. B.; Glass, B.; Bachanova, V.; Ibrahimi, S.; Mielke, S.; Mutsaers, P.; Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, F.; et al. Lisocabtagene Maraleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Primary Analysis of the Phase 3 TRANSFORM Study. Blood, 2023, 141, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Yang, H.; Guo, Y.; Li, W.; Zou, D.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wu, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Relmacabtagene Autoleucel (Relma-cel) CD19 CAR-T Therapy for Adults with Heavily Pretreated Relapsed/Refractory Large B-cell Lymphoma in China. Cancer Med., 2021, 10, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, L.; Song, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Q.; Xu, K.; Yan, D.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; et al. Inaticabtagene Autoleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Blood Adv., 2025, 9, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddie, C.; Sandhu, K. S.; Tholouli, E.; Logan, A. C.; Shaughnessy, P.; Barba, P.; Ghobadi, A.; Guerreiro, M.; Yallop, D.; Abedi, M.; et al. Obecabtagene Autoleucel in Adults with B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med., 2024, 391, 2219–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheykhhasan, M.; Ahmadieh-Yazdi, A.; Vicidomini, R.; Poondla, N.; Tanzadehpanah, H.; Dirbaziyan, A.; Mahaki, H.; Manoochehri, H.; Kalhor, N.; Dama, P. CAR T Therapies in Multiple Myeloma: Unleashing the Future. Cancer Gene Ther., 2024, 31, 667–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, N. C.; Anderson, L. D.; Shah, N.; Madduri, D.; Berdeja, J.; Lonial, S.; Raje, N.; Lin, Y.; Siegel, D.; Oriol, A.; et al. Idecabtagene Vicleucel in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med., 2021, 384, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.; Usmani, S. Z.; Berdeja, J. G.; Agha, M.; Cohen, A. D.; Hari, P.; Avigan, D.; Deol, A.; Htut, M.; Lesokhin, A.; et al. Ciltacabtagene Autoleucel, an Anti–B-Cell Maturation Antigen Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy, for Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: CARTITUDE-1 2-Year Follow-Up. J. Clin. Oncol., 2023, 41, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keam, S. J. Equecabtagene Autoleucel: First Approval. Mol. Diagn. Ther., 2023, 27, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, S. Zevorcabtagene Autoleucel: First Approval. Mol. Diagn. Ther., 2024, 28, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Han, X.; Bo, J.; Han, W. Target Selection for CAR-T Therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol., 2019, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, Z.; Tong, C.; Dai, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Lv, H.; Luo, C.; et al. CD133-Directed CAR T Cells for Advanced Metastasis Malignancies: A Phase I Trial. Oncoimmunology, 2018, 7, e1440169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczycka, M.; Derlatka, K.; Tasior, J.; Lejman, M.; Zawitkowska, J. CAR T-Cell Therapy in Children with Solid Tumors. J. Clin. Med., 2023, 12, 2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, S. M.; Walthers, C. M.; Ji, B.; Ghafouri, S. N.; Naparstek, J.; Trent, J.; Chen, J. M.; Roshandell, M.; Harris, C.; Khericha, M.; et al. CD19/CD20 Bispecific Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) in Naive/Memory T Cells for the Treatment of Relapsed or Refractory Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Cancer Discov., 2023, 13, 580–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M. J.; Baird, J. H.; Kramer, A. M.; Srinagesh, H. K.; Patel, S.; Brown, A. K.; Oak, J. S.; Younes, S. F.; Natkunam, Y.; Hamilton, M. P.; et al. CD22-Directed CAR T-Cell Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphomas Progressing after CD19-Directed CAR T-Cell Therapy: A Dose-Finding Phase 1 Study. Lancet, 2024, 404, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lv, H.; Xiao, X.; Bai, X.; Liu, P.; Pu, Y.; Meng, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. A Phase I Clinical Trial of CLL-1 CAR-T Cells for the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Adults. Blood, 2023, 142 (Supplement 1), 2106–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, F.; Thompson, A. A.; Kwiatkowski, J. L.; Porter, J. B.; Thrasher, A. J.; Hongeng, S.; Sauer, M. G.; Thuret, I.; Lal, A.; Algeri, M.; et al. Betibeglogene Autotemcel Gene Therapy for Non–β 0 /β 0 Genotype β-Thalassemia. N. Engl. J. Med., 2022, 386, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, F.; Calbi, V.; Natali Sora, M. G.; Sessa, M.; Baldoli, C.; Rancoita, P. M. V; Ciotti, F.; Sarzana, M.; Fraschini, M.; Zambon, A. A.; et al. Lentiviral Haematopoietic Stem-Cell Gene Therapy for Early-Onset Metachromatic Leukodystrophy: Long-Term Results from a Non-Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 1/2 Trial and Expanded Access. Lancet, 2022, 399, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, F.; Duncan, C. N.; Musolino, P. L.; Lund, T. C.; Gupta, A. O.; De Oliveira, S.; Thrasher, A. J.; Aubourg, P.; Kühl, J.-S.; Loes, D. J.; et al. Lentiviral Gene Therapy for Cerebral Adrenoleukodystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med., 2024, 391, 1302–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, J.; Chawla, A.; Thompson, A. A.; Kwiatkowski, J. L.; Parikh, S.; Mapara, M. Y.; Rifkin-Zenenberg, S.; Aygun, B.; Kasow, K. A.; Gupta, A. O.; et al. Lovotibeglogene Autotemcel Gene Therapy for Sickle Cell Disease: 60 Months Follow-Up. J. Sick. Cell Dis., 2024, 1 (Supplement_1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, A.; Semeraro, M.; Adam, F.; Booth, C.; Dupré, L.; Morris, E. C.; Gabrion, A.; Roudaut, C.; Borgel, D.; Toubert, A.; et al. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Lentiviral Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cell Gene Therapy for Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome. Nat. Med., 2022, 28, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czechowicz, A. D.; Sevilla, J.; Booth, C.; Zubicaray, J.; Rio, P.; Navarro, S.; Cherry, K.; O’Toole, G.; Xu-Bayford, J.; Ancliff, P.; et al. Lentiviral-Mediated Gene Therapy for Patients with Fanconi Anemia [Group a]: Updated Results from Global RP-L102 Clinical Trials. Blood, 2024, 144 (Supplement 1), 7463–7463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Abraham, A.; Aboobacker, F.; Singh, G.; Geevar, T.; Kulkarni, U.; Selvarajan, S.; Korula, A.; Dave, R. G.; Shankar, M.; et al. Lentiviral Gene Therapy with CD34+ Hematopoietic Cells for Hemophilia A. N. Engl. J. Med., 2025, 392, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palfi, S.; Gurruchaga, J. M.; Ralph, G. S.; Lepetit, H.; Lavisse, S.; Buttery, P. C.; Watts, C.; Miskin, J.; Kelleher, M.; Deeley, S.; et al. Long-Term Safety and Tolerability of ProSavin, a Lentiviral Vector-Based Gene Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease: A Dose Escalation, Open-Label, Phase 1/2 Trial. Lancet, 2014, 383, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campochiaro, P. A.; Lauer, A. K.; Sohn, E. H.; Mir, T. A.; Naylor, S.; Anderton, M. C.; Kelleher, M.; Harrop, R.; Ellis, S.; Mitrophanous, K. A. Lentiviral Vector Gene Transfer of Endostatin/Angiostatin for Macular Degeneration (GEM) Study. Hum. Gene Ther., 2017, 28, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M. A.; Erker, L. R.; Audo, I.; Choi, D.; Mohand-Said, S.; Sestakauskas, K.; Benoit, P.; Appelqvist, T.; Krahmer, M.; Ségaut-Prévost, C.; et al. Three-Year Safety Results of SAR422459 (EIAV-ABCA4) Gene Therapy in Patients With ABCA4-Associated Stargardt Disease: An Open-Label Dose-Escalation Phase I/IIa Clinical Trial, Cohorts 1-5. Am. J. Ophthalmol., 2022, 240, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Pneumocystis Pneumonia among Homosexual Men--New York City and California. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep., 1981, 30, 305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Shampo, M. A.; Kyle, R. A. Luc Montagnier—Discoverer of the AIDS Virus. Mayo Clin. Proc., 2002, 77, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocwieja, K. E.; Sherrill-Mix, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Custers-Allen, R.; David, P.; Brown, M.; Wang, S.; Link, D. R.; Olson, J.; Travers, K.; et al. Dynamic Regulation of HIV-1 MRNA Populations Analyzed by Single-Molecule Enrichment and Long-Read Sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res., 2012, 40, 10345–10355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, R.; Mulligan, R. C.; Baltimore, D. Construction of a Retrovirus Packaging Mutant and Its Use to Produce Helper-Free Defective Retrovirus. Cell, 1983, 33, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgenstern, J. P.; Land, H. Advanced Mammalian Gene Transfer: High Titre Retroviral Vectors with Multiple Drug Selection Markers and a Complementary Helper-Free Packaging Cell Line. Nucleic Acids Res., 1990, 18, 3587–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. G.; Adam, M. A.; Miller, A. D. Gene Transfer by Retrovirus Vectors Occurs Only in Cells That Are Actively Replicating at the Time of Infection. Mol. Cell. Biol., 1990, 10, 4239–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J. C.; Friedmann, T.; Driever, W.; Burrascano, M.; Yee, J. K. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus G Glycoprotein Pseudotyped Retroviral Vectors: Concentration to Very High Titer and Efficient Gene Transfer into Mammalian and Nonmammalian Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 1993, 90, 8033–8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldini, L.; Blömer, U.; Gallay, P.; Ory, D.; Mulligan, R.; Gage, F. H.; Verma, I. M.; Trono, D. In Vivo Gene Delivery and Stable Transduction of Nondividing Cells by a Lentiviral Vector. Science (80-. )., 1996, 272, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, R.; Nagy, D.; Mandel, R. J.; Naldini, L.; Trono, D. Multiply Attenuated Lentiviral Vector Achieves Efficient Gene Delivery in Vivo. Nat. Biotechnol., 1997, 15, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dull, T.; Zufferey, R.; Kelly, M.; Mandel, R. J.; Nguyen, M.; Trono, D.; Naldini, L. A Third-Generation Lentivirus Vector with a Conditional Packaging System. J. Virol., 1998, 72, 8463–8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, H.; Blömer, U.; Takahashi, M.; Gage, F. H.; Verma, I. M. Development of a Self-Inactivating Lentivirus Vector. J. Virol., 1998, 72, 8150–8157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, R.; Donello, J. E.; Trono, D.; Hope, T. J. Woodchuck Hepatitis Virus Posttranscriptional Regulatory Element Enhances Expression of Transgenes Delivered by Retroviral Vectors. J. Virol., 1999, 73, 2886–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follenzi, A.; Ailles, L. E.; Bakovic, S.; Geuna, M.; Naldini, L. Gene Transfer by Lentiviral Vectors Is Limited by Nuclear Translocation and Rescued by HIV-1 Pol Sequences. Nat. Genet., 2000, 25, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zennou, V.; Petit, C.; Guetard, D.; Nerhbass, U.; Montagnier, L.; Charneau, P. HIV-1 Genome Nuclear Import Is Mediated by a Central DNA Flap. Cell, 2000, 101, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, T.; Reynolds, T. C.; Yu, G.; Brown, P. O. Integration of Murine Leukemia Virus DNA Depends on Mitosis. EMBO J., 1993, 12, 2099–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.; Ruppert-Seipp, G.; Müller, S.; Maurer, G. D.; Hartmann, J.; Holtick, U.; Buchholz, C. J.; Funk, M. B. CAR T-Cell-Associated Secondary Malignancies Challenge Current Pharmacovigilance Concepts. EMBO Mol. Med., 2025, 17, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willyard, C. Do Cutting-Edge CAR-T-Cell Therapies Cause Cancer? What the Data Say. Nature, 2024, 629, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA Investigating CAR-Related T-Cell Malignancies. Cancer Discov., 2024, 14, 9–10. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, C. N.; Bledsoe, J. R.; Grzywacz, B.; Beckman, A.; Bonner, M.; Eichler, F. S.; Kühl, J.-S.; Harris, M. H.; Slauson, S.; Colvin, R. A.; et al. Hematologic Cancer after Gene Therapy for Cerebral Adrenoleukodystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med., 2024, 391, 1287–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. Y.; Zhang, X.; Witola, W. H. Small GTPase Immunity-Associated Proteins Mediate Resistance to Toxoplasma Gondii Infection in Lewis Rat. Infect. Immun., 2018, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Karpova, Y.; Guo, D.; Ghatak, A.; Markov, D. A.; Tulin, A. V. PARG Suppresses Tumorigenesis and Downregulates Genes Controlling Angiogenesis, Inflammatory Response, and Immune Cell Recruitment. BMC Cancer, 2022, 22, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvandi, Z.; Opas, M. C-Src Kinase Inhibits Osteogenic Differentiation via Enhancing STAT1 Stability. PLoS One, 2020, 15, e0241646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Bailey, A. L.; Plante, K. S.; Plante, J. A.; Zou, J.; Xia, H.; Bopp, N. E.; Aguilar, P. V.; et al. A Trans-Complementation System for SARS-CoV-2 Recapitulates Authentic Viral Replication without Virulence. Cell, 2021, 184, 2229–2238.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gossen, M.; Bujard, H. Tight Control of Gene Expression in Mammalian Cells by Tetracycline-Responsive Promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 1992, 89, 5547–5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vink, C. A.; Counsell, J. R.; Perocheau, D. P.; Karda, R.; Buckley, S. M. K.; Brugman, M. H.; Galla, M.; Schambach, A.; McKay, T. R.; Waddington, S. N.; et al. Eliminating HIV-1 Packaging Sequences from Lentiviral Vector Proviruses Enhances Safety and Expedites Gene Transfer for Gene Therapy. Mol. Ther., 2017, 25, 1790–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkhout, B. A Fourth Generation Lentiviral Vector: Simplifying Genomic Gymnastics. Mol. Ther., 2017, 25, 1741–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Alberts, B.; Mitrophanous, K.; Clarkson, N.; Farley, D.; Kazarian, K.; Hove, S. THE TETRAVECTATM SYSTEM: A NEW TOOL KIT ENHANCING LENTIVIRAL VECTOR PRODUCTION FOR THE NEXT GENERATION OF GENE THERAPIES. Cytotherapy, 2024, 26, S208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Alberts, B. M.; Hood, A. J.; Nogueira, C.; Miskolczi, Z.; Vieira, C. R.; Chipchase, D.; Lamont, C. M.; Goodyear, O.; Moyce, L. J.; et al. Improved Production and Quality of Lentiviral Vectors By Major-Splice-Donor Mutation and Co-Expression of a Novel U1 Snrna-Based Enhancer. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, N.; van Bel, N.; Berkhout, B.; Das, A. T. HIV-1 Splicing at the Major Splice Donor Site Is Restricted by RNA Structure. Virology, 2014, 468–470, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, R. A.; Jones, R. B.; Pertea, M.; Bruner, K. M.; Martin, A. R.; Thomas, A. S.; Capoferri, A. A.; Beg, S. A.; Huang, S.-H.; Karandish, S.; et al. Defective HIV-1 Proviruses Are Expressed and Can Be Recognized by Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes, Which Shape the Proviral Landscape. Cell Host Microbe, 2017, 21, 494–506.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertkaya, H.; Ficarelli, M.; Sweeney, N. P.; Parker, H.; Vink, C. A.; Swanson, C. M. HIV-1 Sequences in Lentiviral Vector Genomes Can Be Substantially Reduced without Compromising Transduction Efficiency. Sci. Rep., 2021, 11, 12067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antson, A. A.; Dodson, E. J.; Dodson, G.; Greaves, R. B.; Chen, X.; Gollnick, P. Structure of the Trp RNA-Binding Attenuation Protein, TRAP, Bound to RNA. Nature, 1999, 401, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, H. E.; Wright, J.; Kolli, B. R.; Vieira, C. R.; Mkandawire, T. T.; Tatoris, S.; Kennedy, V.; Iqball, S.; Devarajan, G.; Ellis, S.; et al. Enhancing Titres of Therapeutic Viral Vectors Using the Transgene Repression in Vector Production (TRiP) System. Nat. Commun., 2017, 8, 14834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy, 2016, 43, 203–222. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabler, C. O.; Wegman, S. J.; Chen, J.; Shroff, H.; Alhusaini, N.; Tilton, J. C. The HIV-1 Viral Protease Is Activated during Assembly and Budding Prior to Particle Release. J. Virol., 2022, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itano, M. S.; Arnion, H.; Wolin, S. L.; Simon, S. M. Recruitment of 7SL RNA to Assembling HIV-1 Virus-like Particles. Traffic, 2018, 19, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ONAFUWA-NUGA, A. A.; TELESNITSKY, A.; KING, S. R. 7SL RNA, but Not the 54-Kd Signal Recognition Particle Protein, Is an Abundant Component of Both Infectious HIV-1 and Minimal Virus-like Particles. RNA, 2006, 12, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Mak, J.; Cao, Q.; Li, Z.; Wainberg, M. A.; Kleiman, L. Incorporation of Excess Wild-Type and Mutant TRNA(3Lys) into Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. J. Virol., 1994, 68, 7676–7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiman, L.; Jones, C. P.; Musier-Forsyth, K. Formation of the TRNA Lys Packaging Complex in HIV-1. FEBS Lett., 2010, 584, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, E. K.; Yuan, H. E. H.; Luban, J. Specific Incorporation of Cyclophilin A into HIV-1 Virions. Nature, 1994, 372, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, D. E.; Coren, L. V; Kane, B. P.; Busch, L. K.; Johnson, D. G.; Sowder, R. C.; Chertova, E. N.; Arthur, L. O.; Henderson, L. E. Cytoskeletal Proteins inside Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Virions. J. Virol., 1996, 70, 7734–7743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B.; Tessmer, U.; Schubert, U.; Kräusslich, H.-G. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Vpr Protein Is Incorporated into the Virion in Significantly Smaller Amounts than Gag and Is Phosphorylated in Infected Cells. J. Virol., 2000, 74, 9727–9731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, M. E.; Colquhoun, D. R.; Ubaida Mohien, C.; Kole, T.; Aquino, V.; Cotter, R.; Edwards, N.; Hildreth, J. E. K.; Graham, D. R. The Conserved Set of Host Proteins Incorporated into HIV-1 Virions Suggests a Common Egress Pathway in Multiple Cell Types. J. Proteome Res., 2013, 12, 2045–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, R.; Ratner, L. Role of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Matrix Phosphorylation in an Early Postentry Step of Virus Replication. J. Virol., 2004, 78, 2319–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnie, J.; Guzzo, C. The Incorporation of Host Proteins into the External HIV-1 Envelope. Viruses, 2019, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzzo, C.; Ichikawa, D.; Park, C.; Phillips, D.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, P.; Kwon, A.; Miao, H.; Lu, J.; Rehm, C.; et al. Virion Incorporation of Integrin A4β7 Facilitates HIV-1 Infection and Intestinal Homing. Sci. Immunol., 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi, K.; Kim, Y.; Latinovic, O.; Morozov, V.; Melikyan, G. B. HIV Enters Cells via Endocytosis and Dynamin-Dependent Fusion with Endosomes. Cell, 2009, 137, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelman, A. N.; Singh, P. K. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of HIV-1 Integration Targeting. Cell. Mol. Life Sci., 2018, 75, 2491–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Reiser, J. Altering the Tropism of Lentiviral Vectors through Pseudotyping. Curr. Gene Ther., 2005, 5, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvergé, A.; Negroni, M. Pseudotyping Lentiviral Vectors: When the Clothes Make the Virus. Viruses, 2020, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, T.; Kanatsu-Shinohara, M. Transgenesis and Genome Editing of Mouse Spermatogonial Stem Cells by Lentivirus Pseudotyped with Sendai Virus F Protein. Stem Cell Reports, 2020, 14, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jargalsaikhan, B.-E.; Muto, M.; Been, Y.; Matsumoto, S.; Okamura, E.; Takahashi, T.; Narimichi, Y.; Kurebayashi, Y.; Takeuchi, H.; Shinohara, T.; et al. The Dual-Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vector with VSV-G and Sendai Virus HN Enhances Infection Efficiency through the Synergistic Effect of the Envelope Proteins. Viruses, 2024, 16, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dautzenberg, I. J. C.; Rabelink, M. J. W. E.; Hoeben, R. C. The Stability of Envelope-Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vectors. Gene Ther., 2021, 28, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frecha, C.; Costa, C.; Nègre, D.; Gauthier, E.; Russell, S. J.; Cosset, F.-L.; Verhoeyen, E. Stable Transduction of Quiescent T Cells without Induction of Cycle Progression by a Novel Lentiviral Vector Pseudotyped with Measles Virus Glycoproteins. Blood, 2008, 112, 4843–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haid, S.; Grethe, C.; Bankwitz, D.; Grunwald, T.; Pietschmann, T. Identification of a Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus Cell Entry Inhibitor by Using a Novel Lentiviral Pseudotype System. J. Virol., 2016, 90, 3065–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, N.; Chang, H. E.; Nicolas, E.; Gudima, S.; Chang, J.; Taylor, J. Assembly of Hepatitis B Virus Envelope Proteins onto a Lentivirus Pseudotype That Infects Primary Human Hepatocytes. J. Virol., 2007, 81, 10897–10904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatziioannou, T.; Russell, S. J.; Cosset, F.-L. Incorporation of Simian Virus 5 Fusion Protein into Murine Leukemia Virus Particles and Its Effect on the Co-Incorporation of Retroviral Envelope Glycoproteins. Virology, 2000, 267, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bour, S.; Geleziunas, R.; Wainberg, M. A. The Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) CD4 Receptor and Its Central Role in Promotion of HIV-1 Infection. Microbiol. Rev., 1995, 59, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. Molecular Mechanism of HIV-1 Entry. Trends Microbiol., 2019, 27, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitz, J.; Buchholz, C. J.; Engelstädter, M.; Uckert, W.; Bloemer, U.; Schmitt, I.; Cichutek, K. Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with Envelope Glycoproteins Derived from Gibbon Ape Leukemia Virus and Murine Leukemia Virus 10A1. Virology, 2000, 273, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schambach, A.; Galla, M.; Modlich, U.; Will, E.; Chandra, S.; Reeves, L.; Colbert, M.; Williams, D. A.; von Kalle, C.; Baum, C. Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with Murine Ecotropic Envelope: Increased Biosafety and Convenience in Preclinical Research. Exp. Hematol., 2006, 34, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, H. A.; Mestre, D. A.; Rodrigues, A. F.; Guerreiro, M. R.; Carrondo, M. J. T.; Coroadinha, A. S. Improved GaLV-TR Glycoproteins to Pseudotype Lentiviral Vectors: Impact of Viral Protease Activity in the Production of LV Pseudotypes. Mol. Ther. - Methods Clin. Dev., 2019, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. J.; Kobinger, G. P.; Passini, M. A.; Wilson, J. M.; Wolfe, J. H. Targeted Transduction Patterns in the Mouse Brain by Lentivirus Vectors Pseudotyped with VSV, Ebola, Mokola, LCMV, or MuLV Envelope Proteins. Mol. Ther., 2002, 5, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirow, M.; Schwarze, L. I.; Fehse, B.; Riecken, K. Efficient Pseudotyping of Different Retroviral Vectors Using a Novel, Codon-Optimized Gene for Chimeric GALV Envelope. Viruses, 2021, 13, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandrin, V.; Boson, B.; Salmon, P.; Gay, W.; Nègre, D.; Le Grand, R.; Trono, D.; Cosset, F.-L. Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with a Modified RD114 Envelope Glycoprotein Show Increased Stability in Sera and Augmented Transduction of Primary Lymphocytes and CD34+ Cells Derived from Human and Nonhuman Primates. Blood, 2002, 100, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuyama, M.; Ohashi, Y.; Tsubota, T.; Yaguchi, M.; Kato, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Miyashita, Y. Avian Sarcoma Leukosis Virus Receptor-Envelope System for Simultaneous Dissection of Multiple Neural Circuits in Mammalian Brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 2015, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.-L.; Halbert, C. L.; Miller, A. D. Jaagsiekte Sheep Retrovirus Envelope Efficiently Pseudotypes Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1-Based Lentiviral Vectors. J. Virol., 2004, 78, 2642–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Cai, S.; Zeng, Y.; Lindemann, D.; Pollok, K. E.; Hanenberg, H.; Clapp, D. W. A Modified Foamy Viral Envelope Enhances Gene Transfer Efficiency and Reduces Toxicity of Lentiviral FANCA Vectors in Fanca-/- HSCs. Blood, 2009, 114, 696–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colamartino, A. B. L. L.; Lemieux, W.; Bifsha, P.; Nicoletti, S.; Chakravarti, N.; Sanz, J.; Roméro, H.; Selleri, S.; Béland, K.; Guiot, M.; et al. Efficient and Robust NK-Cell Transduction With Baboon Envelope Pseudotyped Lentivector. Front. Immunol., 2019, 10, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, A.; Stahringer, A.; Ruppel, K. E.; Fricke, S.; Koehl, U.; Schmiedel, D. Development of KoRV-Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vectors for Efficient Gene Transfer into Freshly Isolated Immune Cells. Gene Ther., 2024, 31, (7–8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelshtein, D.; Werman, A.; Novick, D.; Barak, S.; Rubinstein, M. LDL Receptor and Its Family Members Serve as the Cellular Receptors for Vesicular Stomatitis Virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 2013, 110, 7306–7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePolo, N. J.; Reed, J. D.; Sheridan, P. L.; Townsend, K.; Sauter, S. L.; Jolly, D. J.; Dubensky, T. W. VSV-G Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vector Particles Produced in Human Cells Are Inactivated by Human Serum. Mol. Ther., 2000, 2, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, J. N.; Islam, T. A.; Eleftheriadou, I.; Carpentier, D. C. J.; Trabalza, A.; Parkinson, M.; Schiavo, G.; Mazarakis, N. D. Rabies Virus Envelope Glycoprotein Targets Lentiviral Vectors to the Axonal Retrograde Pathway in Motor Neurons. J. Biol. Chem., 2014, 289, 16148–16163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, J. R.; Sew, T.; Montero, L.; Burton, E. A.; Greenamyre, J. T. Pseudotype-Dependent Lentiviral Transduction of Astrocytes or Neurons in the Rat Substantia Nigra. Exp. Neurol., 2011, 228, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trobridge, G. D.; Wu, R. A.; Hansen, M.; Ironside, C.; Watts, K. L.; Olsen, P.; Beard, B. C.; Kiem, H.-P. Cocal-Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vectors Resist Inactivation by Human Serum and Efficiently Transduce Primate Hematopoietic Repopulating Cells. Mol. Ther., 2010, 18, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Mohan Kumar, D.; Sax, C.; Schuler, C.; Akkina, R. Pseudotyping of Lentiviral Vector with Novel Vesiculovirus Envelope Glycoproteins Derived from Chandipura and Piry Viruses. Virology, 2016, 488, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Bradow, B. P.; Zimmerberg, J. Large-Scale Production of Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vectors Using Baculovirus GP64. Hum. Gene Ther., 2003, 14, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauber, C.; Tuerk, M.; Pacheco, C.; Escarpe, P.; Veres, G. Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with Baculovirus Gp64 Efficiently Transduce Mouse Cells in Vivo and Show Tropism Restriction against Hematopoietic Cell Types in Vitro. Gene Ther., 2004, 11, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, M.; Canepari, C.; Assanelli, S.; Merlin, S.; Borroni, E.; Starinieri, F.; Biffi, M.; Russo, F.; Fabiano, A.; Zambroni, D.; et al. GP64-Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vectors Target Liver Endothelial Cells and Correct Hemophilia A Mice. EMBO Mol. Med., 2024, 16, 1427–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, C.; Kaname, Y.; Taguwa, S.; Abe, T.; Fukuhara, T.; Tani, H.; Moriishi, K.; Matsuura, Y. Baculovirus GP64-Mediated Entry into Mammalian Cells. J. Virol., 2012, 86, 2610–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirache, F.; Lévy, C.; Costa, C.; Mangeot, P. E.; Torbett, B. E.; Wang, C. X.; Nègre, D.; Cosset, F. L.; Verhoeyen, E. Mystery Solved: VSV-G-LVs Do Not Allow Efficient Gene Transfer into Unstimulated T Cells, B Cells, and HSCs Because They Lack the LDL Receptor. Blood, 2014, 123, 1422–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, J.-M.; Frecha, C.; Bouafia, F. A.; N′Guyen, T. H.; Boni, S.; Cosset, F.-L.; Verhoeyen, E.; Halary, F. Measles Virus Glycoprotein-Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vectors Are Highly Superior to Vesicular Stomatitis Virus G Pseudotypes for Genetic Modification of Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells. J. Virol., 2012, 86, 5192–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, C.; Amirache, F.; Costa, C.; Frecha, C.; Muller, C. P.; Kweder, H.; Buckland, R.; Cosset, F.-L.; Verhoeyen, E. Lentiviral Vectors Displaying Modified Measles Virus Gp Overcome Pre-Existing Immunity in In Vivo-like Transduction of Human T and B Cells. Mol. Ther., 2012, 20, 1699–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, C.; Amirache, F.; Girard-Gagnepain, A.; Frecha, C.; Roman-Rodríguez, F. J.; Bernadin, O.; Costa, C.; Nègre, D.; Gutierrez-Guerrero, A.; Vranckx, L. S.; et al. Measles Virus Envelope Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vectors Transduce Quiescent Human HSCs at an Efficiency without Precedent. Blood Adv., 2017, 1, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, C.; Grzybowski, B. N.; Tong, S.; Cheng, L.; Compans, R. W.; LeDoux, J. M. Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with Envelope Glycoproteins Derived from Human Parainfluenza Virus Type 3. Biotechnol. Prog., 2004, 20, 1810–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, C.; Le Doux, J. M. Lentiviruses Inefficiently Incorporate Human Parainfluenza Type 3 Envelope Proteins. Biotechnol. Bioeng., 2008, 99, 1016–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetawat, D.; Broder, C. C. A Functional Henipavirus Envelope Glycoprotein Pseudotyped Lentivirus Assay System. Virol. J., 2010, 7, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares, K.; Vigant, F.; Van Handel, B.; Pernet, O.; Chikere, K.; Hong, P.; Sherman, S. P.; Patterson, M.; An, D. S.; Lowry, W. E.; et al. Nipah Virus Envelope-Pseudotyped Lentiviruses Efficiently Target EphrinB2-Positive Stem Cell Populations In Vitro and Bypass the Liver Sink When Administered In Vivo. J. Virol., 2013, 87, 2094–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, D. N.; Abdullahi, F. L.; Abdu-Raheem, F.; Abicher, L. T.; Adelaiye, H.; Badjie, A.; Bah, A.; Bista, K. P.; Bont, L. J.; Boom, T. T.; et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection among Children Younger than 2 Years Admitted to a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit with Extended Severe Acute Respiratory Infection in Ten Gavi-Eligible Countries: The RSV GOLD—ICU Network Study. Lancet Glob. Heal., 2024, 12, e1611–e1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biuso, F.; Palladino, L.; Manenti, A.; Stanzani, V.; Lapini, G.; Gao, J.; Couzens, L.; Eichelberger, M. C.; Montomoli, E. Use of Lentiviral Pseudotypes as an Alternative to Reassortant or Triton X-100-treated Wild-type Influenza Viruses in the Neuraminidase Inhibition Enzyme-linked Lectin Assay. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses, 2019, 13, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, F.; Del Rosario, J. M. M.; da Costa, K. A. S.; Kinsley, R.; Scott, S.; Fereidouni, S.; Thompson, C.; Kellam, P.; Gilbert, S.; Carnell, G.; et al. Development of Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped With Influenza B Hemagglutinins: Application in Vaccine Immunogenicity, MAb Potency, and Sero-Surveillance Studies. Front. Immunol., 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S. T.; Crozier, I.; Fischer, W. A.; Hewlett, A.; Kraft, C. S.; Vega, M.-A. de La; Soka, M. J.; Wahl, V.; Griffiths, A.; Bollinger, L.; et al. Ebola Virus Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim., 2020, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifflett, K.; Marzi, A. Marburg Virus Pathogenesis – Differences and Similarities in Humans and Animal Models. Virol. J., 2019, 16, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutts, T.; Leung, A.; Banadyga, L.; Krishnan, J. Inactivation Validation of Ebola, Marburg, and Lassa Viruses in AVL and Ethanol-Treated Viral Cultures. Viruses, 2024, 16, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fe Medina, M.; Kobinger, G. P.; Rux, J.; Gasmi, M.; Looney, D. J.; Bates, P.; Wilson, J. M. Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with Minimal Filovirus Envelopes Increased Gene Transfer in Murine Lung. Mol. Ther., 2003, 8, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinn, P. L.; Hickey, M. A.; Staber, P. D.; Dylla, D. E.; Jeffers, S. A.; Davidson, B. L.; Sanders, D. A.; McCray, P. B. Lentivirus Vectors Pseudotyped with Filoviral Envelope Glycoproteins Transduce Airway Epithelia from the Apical Surface Independently of Folate Receptor Alpha. J. Virol., 2003, 77, 5902–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Jin, H.; Wong, G.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, C.; Feng, N.; Wu, F.; Xu, S.; Chi, H.; Zhao, Y.; et al. The Application of a Safe Neutralization Assay for Ebola Virus Using Lentivirus-Based Pseudotyped Virus. Virol. Sin., 2021, 36, 1648–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasaud, A.; Alharbi, N. K.; Hashem, A. M. Generation of MERS-CoV Pseudotyped Viral Particles for the Evaluation of Neutralizing Antibodies in Mammalian Sera; 2020; pp 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Sampson, A. T.; Heeney, J.; Cantoni, D.; Ferrari, M.; Sans, M. S.; George, C.; Di Genova, C.; Mayora Neto, M.; Einhauser, S.; Asbach, B.; et al. Coronavirus Pseudotypes for All Circulating Human Coronaviruses for Quantification of Cross-Neutralizing Antibody Responses. Viruses, 2021, 13, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, W.-S. Other Positive-Strand RNA Viruses. In Molecular Virology of Human Pathogenic Viruses; Elsevier, 2017; pp 177–184. [CrossRef]

- Khongwichit, S.; Chansaenroj, J.; Chirathaworn, C.; Poovorawan, Y. Chikungunya Virus Infection: Molecular Biology, Clinical Characteristics, and Epidemiology in Asian Countries. J. Biomed. Sci., 2021, 28, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gylfe, Å.; Ribers, Å.; Forsman, O.; Bucht, G.; Alenius, G.-M.; Wållberg-Jonsson, S.; Ahlm, C.; Evander, M. Mosquitoborne Sindbis Virus Infection and Long-Term Illness. Emerg. Infect. Dis., 2018, 24, 1141–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiot, C. C.; Grimaud, G.; Garry, P.; Bouquety, J. C.; Mada, A.; Daguisy, A. M.; Georges, A. J. An Outbreak of Human Semliki Forest Virus Infections in Central African Republic. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 1990, 42, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flies, E. J.; Lau, C. L.; Carver, S.; Weinstein, P. Another Emerging Mosquito-Borne Disease? Endemic Ross River Virus Transmission in the Absence of Marsupial Reservoirs. Bioscience, 2018, 68, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, C. A.; Marsh, J.; Fyffe, J.; Sanders, D. A.; Cornetta, K. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1-Derived Lentivirus Vectors Pseudotyped with Envelope Glycoproteins Derived from Ross River Virus and Semliki Forest Virus. J. Virol., 2004, 78, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, C. A.; Pollok, K.; Haneline, L. S.; Cornetta, K. Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with Glycoproteins from Ross River and Vesicular Stomatitis Viruses: Variable Transduction Related to Cell Type and Culture Conditions. Mol. Ther., 2005, 11, 470–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morizono, K.; Ku, A.; Xie, Y.; Harui, A.; Kung, S. K. P.; Roth, M. D.; Lee, B.; Chen, I. S. Y. Redirecting Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with Sindbis Virus-Derived Envelope Proteins to DC-SIGN by Modification of N-Linked Glycans of Envelope Proteins. J. Virol., 2010, 84, 6923–6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishishita, N.; Takeda, N.; Nuegoonpipat, A.; Anantapreecha, S. A Safe and Convenient Chikungunya-Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vector for Epidemiological Studies on Chikungunya Virus in Thailand. Int. J. Infect. Dis., 2012, 16, e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishishita, N.; Takeda, N.; Anuegoonpipat, A.; Anantapreecha, S. Development of a Pseudotyped-Lentiviral-Vector-Based Neutralization Assay for Chikungunya Virus Infection. J. Clin. Microbiol., 2013, 51, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckels, K. H.; Putnak, R. Formalin-Inactivated Whole Virus and Recombinant Subunit Flavivirus Vaccines; 2003; pp 395–418. [CrossRef]

- Lazear, H. M.; Diamond, M. S. Zika Virus: New Clinical Syndromes and Its Emergence in the Western Hemisphere. J. Virol., 2016, 90, 4864–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manns, M. P.; Buti, M.; Gane, E.; Pawlotsky, J.-M.; Razavi, H.; Terrault, N.; Younossi, Z. Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim., 2017, 3, 17006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, W.-S. Flaviviruses. In Molecular Virology of Human Pathogenic Viruses; Elsevier, 2017; pp 165–175. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mao, Y.; Li, Q.; Qiu, Z.; Li, J. J.; Li, X.; Liang, W.; Xu, M.; Li, A.; Cai, X.; et al. Efficient Gene Transfer to Kidney Using a Lentiviral Vector Pseudotyped with Zika Virus Envelope Glycoprotein. Hum. Gene Ther., 2022, 33, (23–24). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosch, B.; Dubuisson, J.; Cosset, F.-L. Infectious Hepatitis C Virus Pseudo-Particles Containing Functional E1–E2 Envelope Protein Complexes. J. Exp. Med., 2003, 197, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, R.; Yuan, L.; Tian, G.; Huang, X.; Wen, Y.; Ma, X.; Huang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Introducing a Cleavable Signal Peptide Enhances the Packaging Efficiency of Lentiviral Vectors Pseudotyped with Japanese Encephalitis Virus Envelope Proteins. Virus Res., 2017, 229, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, N.; Osterhaus, A. D. M. E.; Rimmelzwaan, G. F.; Prajeeth, C. K. Rift Valley Fever Virus—Infection, Pathogenesis and Host Immune Responses. Pathogens, 2023, 12, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawman, D. W.; Feldmann, H. Crimean–Congo Haemorrhagic Fever Virus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 2023, 21, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, V. P.; Di Paola, N.; Alonso, D. O.; Pérez-Sautu, U.; Bellomo, C. M.; Iglesias, A. A.; Coelho, R. M.; López, B.; Periolo, N.; Larson, P. A.; et al. “Super-Spreaders” and Person-to-Person Transmission of Andes Virus in Argentina. N. Engl. J. Med., 2020, 383, 2230–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifuentes-Muñoz, N.; Darlix, J.-L.; Tischler, N. D. Development of a Lentiviral Vector System to Study the Role of the Andes Virus Glycoproteins. Virus Res., 2010, 153, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Zheng, X.; Wang, H.; Gai, W.; Jin, H.; Yan, F.; Qiu, B.; Gao, Y.; et al. Packaging of Rift Valley Fever Virus Pseudoviruses and Establishment of a Neutralization Assay Method. J. Vet. Sci., 2018, 19, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasmehjani, A. A.; Salehi-Vaziri, M.; Azadmanesh, K.; Nejati, A.; Pouriayevali, M. H.; Gouya, M. M.; Parsaeian, M.; Shahmahmoodi, S. Efficient Production of a Lentiviral System for Displaying Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus Glycoproteins Reveals a Broad Range of Cellular Susceptibility and Neutralization Ability. Arch. Virol., 2020, 165, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, K. M.; Melnik, L. I.; Cross, R. W.; Klitting, R. M.; Andersen, K. G.; Saphire, E. O.; Garry, R. F. The Arenaviridae Family: Knowledge Gaps, Animal Models, Countermeasures, and Prototype Pathogens. J. Infect. Dis., 2023, 228 (Supplement_6), S359–S375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R. A.; Dai, D.; Hosack, V. T.; Tan, Y.; Bolken, T. C.; Hruby, D. E.; Amberg, S. M. Identification of a Broad-Spectrum Arenavirus Entry Inhibitor. J. Virol., 2008, 82, 10768–10775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schountz, T. Unraveling the Mystery of Tacaribe Virus. mSphere, 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimojima, M.; Ströher, U.; Ebihara, H.; Feldmann, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Identification of Cell Surface Molecules Involved in Dystroglycan-Independent Lassa Virus Cell Entry. J. Virol., 2012, 86, 2067–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, W. R.; Westphal, M.; Ostertag, W.; von Laer, D. Oncoretrovirus and Lentivirus Vectors Pseudotyped with Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Glycoprotein: Generation, Concentration, and Broad Host Range. J. Virol., 2002, 76, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Wang, J.; Lan, S.; Danzy, S.; McLay Schelde, L.; Seladi-Schulman, J.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y. Characterization of Virulence-Associated Determinants in the Envelope Glycoprotein of Pichinde Virus. Virology, 2012, 433, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, J.; Liu, X.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y. Characterization of the Glycoprotein Stable Signal Peptide in Mediating Pichinde Virus Replication and Virulence. J. Virol., 2016, 90, 10390–10397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreja, H.; Piechaczyk, M. The Effects of N-Terminal Insertion into VSV-G of an ScFv Peptide. Virol. J., 2006, 3, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyvaerts, C.; De Groeve, K.; Dingemans, J.; Van Lint, S.; Robays, L.; Heirman, C.; Reiser, J.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Thielemans, K.; De Baetselier, P.; et al. Development of the Nanobody Display Technology to Target Lentiviral Vectors to Antigen-Presenting Cells. Gene Ther., 2012, 19, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahani, R.; Roohvand, F.; Cohan, R. A.; Etemadzadeh, M. H.; Mohajel, N.; Behdani, M.; Shahosseini, Z.; Madani, N.; Azadmanesh, K. Sindbis Virus-Pseudotyped Lentiviral Vectors Carrying VEGFR2-Specific Nanobody for Potential Transductional Targeting of Tumor Vasculature. Mol. Biotechnol., 2016, 58, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, Q. T.; Morizono, K.; Chen, I. S.; De Vos, S. Construction of Lentiviruses Pseudotyped with Sindbis E2-Single Chain Antibody (SCA) Fusions or Membrane-Anchored SCAs for Targeted Therapies in Lymphoma. Blood, 2009, 114, 3571–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).