5. Towards Supraspinal Structures

It must be emphasized that, rostral to the spinal cord, nociceptive signals are fed into a cascade of structures characterized by two important properties. First, these structures receive inputs from other than nociceptive ones, the ascending nociceptive limb not being a mono-modal labelled line. Second, they exert more than nociceptive functions. Hence, they are multiple-input multiple-output and multi-functional nodes. This has already become clear in the DH.

In humans, a diverse array of CNS structures reacts to painful stimuli. In human brain imaging, acute experimental pain most commonly activates spinal and brainstem structures, the THAL, primary somatosensory (S1) and secondary somatosensory cortex (S2), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insular cortex (IC; or briefly insula), prefrontal cortex (PFC), nucleus accumbens (NAc) in the basal ganglia (BG), and AMY. S1 and S2 activations contribute to the sensory-discriminative dimension of pain. The ACC, PFC, IC, NAc, and amygdala (AMY) have been implicated in the affective component of pain (Bushnell et al. 2013; Doan et al. 2015; Henderson and Keay 2018). Signals associated with the pain experience also reach the CNS via the blood stream, by inflammatory mediators that ultimately cause the sickness response of fever, general muscle and joint ache, anorexia and lethargy (Bartfai 2001; Sandkühler 2009).

A meta-analysis of many human neuroimaging studies showed a core of areas exhibiting a largely bilateral pattern of pain-related activation in the THAL, S2, IC, and mid-cingulate cortex (MCC). These regions were activated regardless of stimulation technique, location of induction, and participant sex (Xu et al. 2020). Another meta-analysis showed that experimental pain stimuli activated S1, S2, IC, ACC, PFC, and THAL. Discrimination of pain intensity activated a ventrally directed pathway from the IC to the PFC, while discrimination of the spatial pain aspects involved a dorsally directed pathway from the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) to the dorso-lateral PFC (dlPFC) (Ong et al. 2019). Individual studies showed more diverse patterns. For example, noxious cold exposure activates the THAL, putamen and right anterior insular cortex (aIC), while innocuous cold exposure activates the posterior IC (pIC), medial orbito-frontal cortex (mOFC) and PPC (King and Carnahan 2019). Heat-evoked acute pain activates both somatic-specific areas such as the ventro-lateral THAL, the S2 and dorsal pIC, as well as regions related to affect and mood, such as the aIC, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and the medial THAL (Kuner and Kuner 2021). The medial PFC (mPFC) mediates anti-nociceptive effects via its connections with other cortical areas and via its input to the peri-aqueductal gray (PAG) for modulation of pain (Ong et al. 2019).

Neuroimaging in (mostly anesthetized) animals shows commonalities with (awake) humans. Upon hindpaw thermal stimulation in rats, activations have been seen in the medial and lateral posterior THAL nuclei, S1, IC, cingulate cortex (CC), retro-splenial cortex (RSC), pretectal area as well as in the descending pain-modulatory centers, such as the diencephalic hypothalamus (HYP) and the midbrain PAG (Da Silva and Seminowicz 2019; Kuner and Kuner 2021).

5.1. Spinal Projection Neurons with Multiple Supraspinal Targets

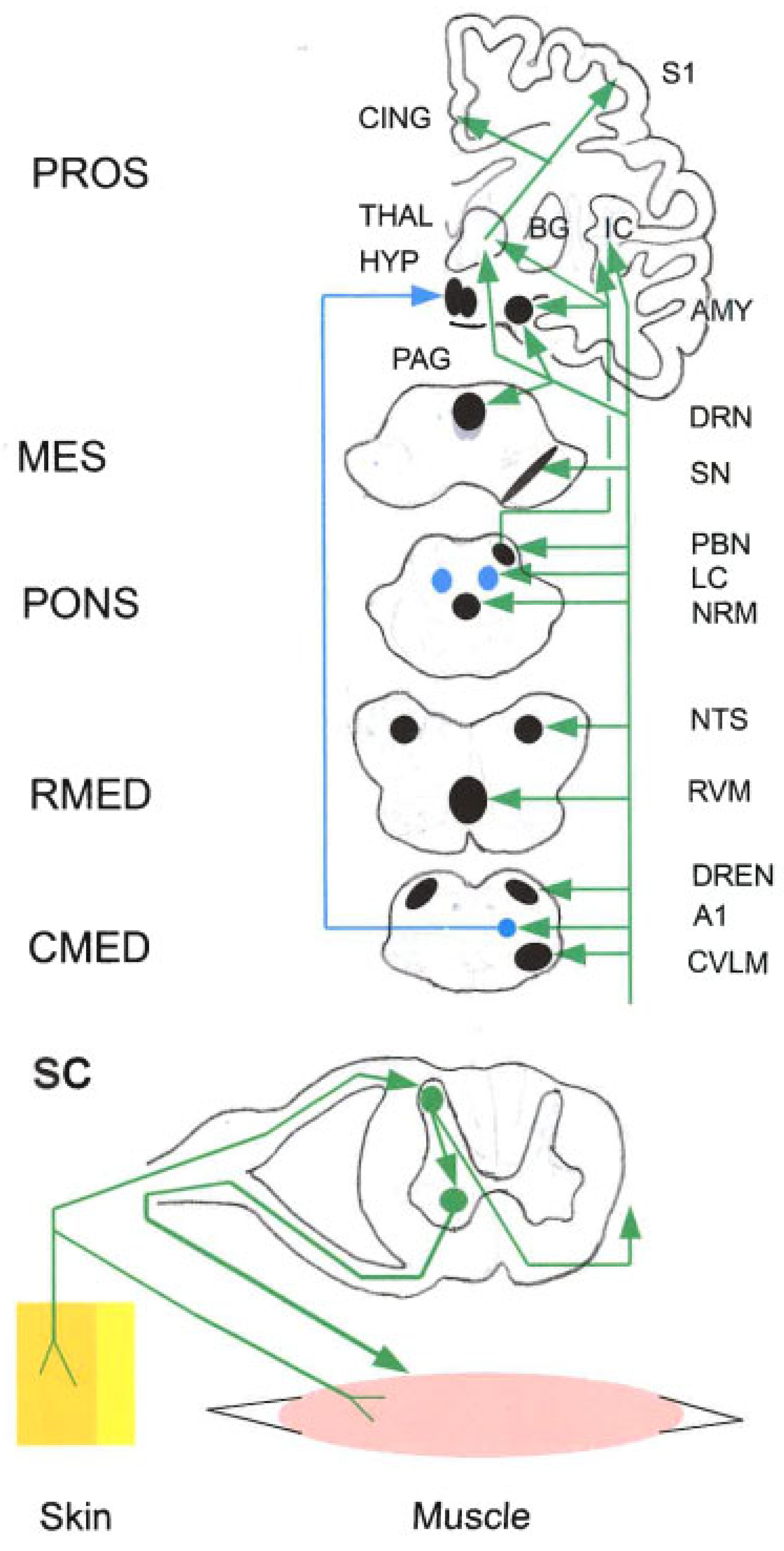

Ascending Nociceptive Tracts (Figure 2). Nociceptive group III and group IV afferents contact a minority of `projection´ neurons in the spinal DH or spV. Projection neurons convey nociceptive signals via multiple parallel pathways to multiple supraspinal targets in the brainstem, diencephalon, THAL and thence to the cerebral cortex. Ascending tracts include the spino-THAL tract (STTr), spino-cervico- THAL pathway, spino-hypothalamic pathway, spino-parabrachio-amygdaloid pathway, spino-reticular tracts, spino-mesencephalic tract, spino-limbic tracts, and postsynaptic dorsal column pathway (Bushnell et al. 2013; Coghill 2020; Dostrovsky 2000; Kuner and Kuner 2021; Poisbeau et al. 2018).

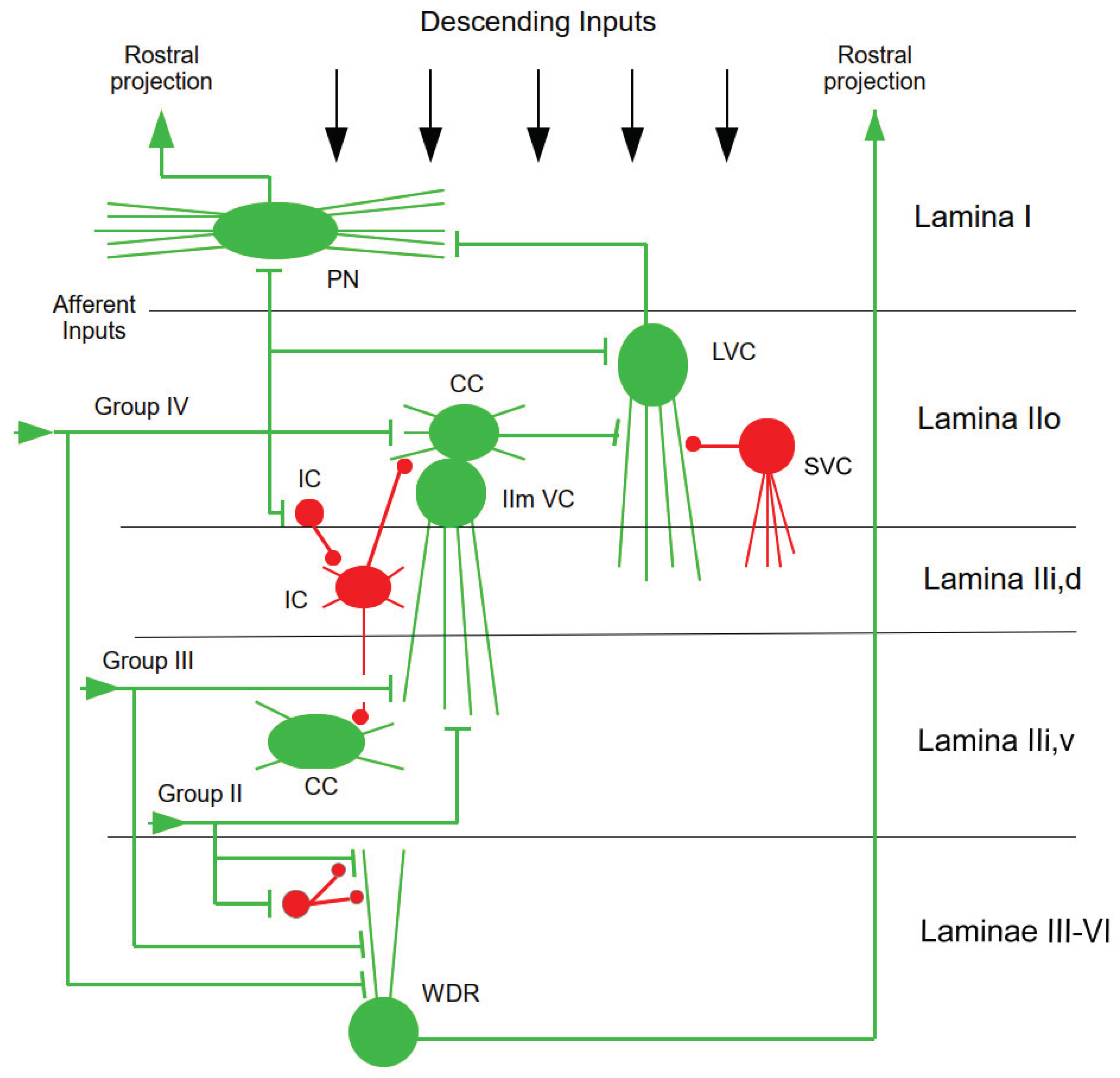

Properties of Projection Neurons. The somata of projection neurons are located in the superficial DH (lamina I), deep DH (laminae V, VI), VH (lamina VII) of primates, and the central gray (lamina X). At spinal level, projection neurons produce axon collaterals that are widely distributed within and between spinal segments, whose functions are hardly known, however (Browne et al. 2020). Many projection neurons in lamina I are nociceptive-specific (NS), with inputs from nociceptive afferents only. Lamina V contains wide-dynamic-range (WDR) neurons with inputs from nociceptive and non-nociceptive sensory afferents and appear to be able to encode noxious stimulus intensity (Braz et al. 2014). In the mouse, genetic methods have revealed distinct modular circuits made up of molecularly defined interneurons that process nociceptive (pain), pruritic (itch) and cutaneous mechano-sensitive (innocuous touch) stimuli. Excitatory interneurons transmit somatosensory information and inhibitory interneurons operate as gates to prevent innocuous stimuli from activating nociceptive and pruritic pathways (Koch et al. 2018). The properties of these neurons can change depending on context; for example, depolarization may transform NS neurons into WDR neurons (Berger et al. 2011; Sandkühler 2009). Neuron properties are also altered by the actions of several classes of neuromodulators and neuropeptides (Zeilhofer et al. 2012).

Spino-THAL Tract (STTr).The STTr has two parts, a lateral and an anterior part. The former originates in DH lamina I and, on its way to the THAL, sends collaterals to (i) the brainstem RF, interpeduncular area, noradrenergic (NA) cell groups A1, A5, A6, A7 (the latter three not illustrated in

Figure 2, for graphical reasons), and the adrenergic C1 cell group, A1 projecting further to the HYP; (ii) the parabrachial nucleus (PBN, projecting on to the AMY), the PAG, the HYP, the central nucleus of the AMY (CeA), and finally to the THAL [posterior portion of the ventral medial nucleus (Vmpo), ventro-posterior inferior nucleus (VPI), and ventral caudal portion of the medial dorsal nucleus (MDvc)] (Dostrovsky 2000; Kuner and Kuner 2021). The anterior STTr originates in DH laminae IV-V and, in the brainstem, sends collaterals to the sub-nucleus reticularis dorsalis (SRD) and other sites, and ends in VPI, ventral posterolateral nucleus (VPL) and central lateral nucleus (CL) (Dostrovsky 2000).

Other Ascending Nociceptive Pathways. Some ascending pathways transmit signals associated with motivational and cognitive aspects [the spino-reticular tract and spino-parabrachial tract (

Figure 2)], affectivity (the spino-mesencephalic tract and spino-parabrachial tract), motor responses, as well as neuro-endocrine and autonomic responses (the spino-hypothalamic tract). The spino-reticular tract is a multi-synaptic pathway originating from neurons mainly located in the spinal cord laminae IV–V and VII–VIII targeting areas of the medullary and pontine reticular formation, which have collaterals of the STTr (Martins and Tavares 2017). The spino-parabrachial tract is a significant site of convergence for both somatic and visceral nociceptive stimuli (Merighi 2018). Ascending nociceptive signals can also be indirectly conveyed to the THAL by the spino-mesencephalic and dorsal postsynaptic dorsal-column pathway (Almeida et al. 2004; Braz et al. 2014; Coghill 2020; Todd 2010; Yen and Lu 2013). The ascending pathways transmit nociceptive information across bilateral routes. That is, the spino-THAL projections may arise from deep DH and ventral-horn neurons with bilaleral and/or whole-body receptive fields. The projections of other spino-THAL neurons travel ipsilaterally instead of contralaterally to the cell body (Coghill 2020).

Visceral Projections. Spinal visceral afferent neurons project into the laminae I, II (outer part IIo) and V of the spinal DH over several segments, medio-lateral over the whole width of the DH and contralateral. Their activity is synaptically transmitted in laminae I, IIo and deeper laminae to viscero-somatic convergent neurons that receive additionally afferent synaptic (mostly nociceptive) input from the skin and from deep somatic tissues of the corresponding dermatomes, myotomes and sclerotomes. The second-order neurons consist of excitatory and inhibitory interneurons and tract neurons activated monosynaptically in lamina I by visceral afferent neurons and di- or polysynaptically in deeper laminae. Viscero-somatic tract neurons project through the contralateral ventro-lateral tract and presumably other tracts to the lower and upper brainstem, the HYP and via the THAL to various cortical areas. Visceral pain is presumably (together with other visceral sensations and nociceptive as well as non-nociceptive somatic body sensations) primarily represented in the posterior dorsal IC (primary interoceptive cortex). In primates, this cortex receives its spinal synaptic inputs mainly from lamina I tract neurons via the ventro-medial posterior nucleus of the THAL (Jänig 2014).

The ascending nociceptive pathways thus include many nodes, which will be treated below in some detail in terms of their multiple inputs, outputs and functions, and thus to emphasize their complexity (Figure 2).

5.2. Itch Pathways

Although pain and itch are distinct sensations, most noxious chemicals are not very specific to one sensation over the other. An important difference between these sensations is that itch is initiated by irritation of the skin, whereas pain can be elicited from almost anywhere in the body. Thus, itch may be encoded by the selective activation of specific sub-sets of neurons that are tuned to detect harmful stimuli at the surface and have specialized central connectivity that is specific to itch. Within the spinal cord, cross-modal inhibition between pain and itch may help sharpen the distinction between these sensations. Just as there are inhibitory circuits in the DH that mediate cross-inhibition between modalities, it appears that there are also excitatory connections that can be unmasked upon injury or in disease, leading to abnormally elevated pain states such as allodynia (Ross 2011).

Itch is a unique sensation that urges organisms to scratch away external threats, and scratching in turn induces an immune response that can enhance itchiness. The central pathways and circuits processing itch and pain overlap anatomically, but some neurons transmit itch signals independently of other modalities (Lay and Dong 2020). After spinal processing, itch signals are transferred via projection neurons that connect to the STTr. The next supraspinal itch-processing station is the PBN, which projects to different brain regions including the AMY, which links stress and anxiety to chronic itch.

Functional MRI in humans implicates cortical regions including the S1 and S2, the CC and PFC (Cevikbas and Lerner 2020).

In transgenic mice, one kind of polymodal nociceptors containing galanin (GAL) and one type of pruriceptors expressing neurotensin (NT) took different routes. NT-expressing pruriceptors avoided the STTr, although both ascending projections shared the spino-bulbar projections but occupied different sub-nuclei. In the somatic motor system, more neurons in the red nucleus (nucleus ruber) and primary motor cortex (M1) participated in the GAL-containing nociceptor-derived network, while more neurons in the NTS and the dorsal motor nucleus of vagus nerve (DMX) of the emotional motor system were found in the NT-expressing pruriceptor-derived network. Functional validation of differentially labeled nuclei by c-fos test and chemogenetic inhibition suggested that the red nucleus is involved in facilitating the response to noxious heat and the NTS/DMX in regulating the histamine-induced scratching (Chen et al. 2022).

Genetic deletion techniques have proposed that gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) may be a key neurotransmitter for itch in the spinal cord. Glutamate but not GRP acts as the key neurotransmitter in the primary afferents in the transmission of itch. GRP is more likely to serve as an itch-related neuromodulator. The ACC plays a significant role in both itch and pain sensations (Chen and Zhuo 2023).

5.3. Nucleus Tractus Solitarii (NTS)

The NTS (or nucleus of the solitary tract) is a complex of sub-nuclei aligned in a vertical slice located in the dorso-medial medulla oblongata. The NTS has been divided cytoarchitectonically into various sub-nuclei, which are partly correlated with the areas of projection of peripheral afferent endings. Gustatory and somatic afferents from the oro-pharyngeal region project with a crude somatotopy within the rostral part of the NTS (rNTS) and visceral afferents from cardio-vascular, digestive, respiratory and renal systems terminate viscero-topically within its caudal part (cNTS) (Jean 1991; Holt and Rinaman 2022).

Functions. The extensive connections indicate that the NTS is a central structure for autonomic and neuro-endocrine functions as well as for integration of somatic and autonomic responses in certain behaviors. Painful stimuli can evoke dramatic responses in the cardio-vascular and respiratory systems. The NTS has a major role as a site for integrating nociceptive and cardio-respiratory afferents including and for mediating the reflex tachycardia evoked by somatic noxious stimulation. Similar noxious stimulation attenuates the cardiac component of the peripheral chemo-receptor reflex and inhibits the peripheral chemoreceptor-evoked excitatory synaptic response of some NTS neurons. Hence, by depressing homeostatic reflexes in the NTS, noxious stimulation-evoked cardio-respiratory changes can be expressed and maintained, which may be essential for the survival of the animal (Boscan et al. 2002). The NTS has extensive connections with the vestibular nuclei, both directly and via the PBN; whereby the vestibular nuclei could also receive nociceptive inputs (Saman et al. 2020).

Inputs. The NTS receives fibers from the superficial laminae (I-III) of the spinal DH terminating bi-laterally in the cNTS, and fibers from the deeper DH laminae (IV-V) terminating ipsilaterally, mostly in the lateral areas of the cNTS (Gamboa-Esteves et al. 2001). In rat lamina I neurons receiving noxious cutaneous and visceral stimuli via NK1 receptor activation project to NTS and so may be involved in coordinating nociceptive and cardio-respiratory responses (Gamboa-Esteves et al. 2004). In rats, NTS cells receive hindlimb somatosensory inputs from low- and high-threshold cutaneous mechano-receptors, respond to capsaicin delivered into the hindlimb arterial supply, lack thermal sensitivity, and respond to activation of mechano-sensitive as well as metabo-sensitive endings in skeletal muscle. Visceral sensory information is conveyed via the afferent glossopharyngeal (IX) and vagus (X) nerves (Toney and Mifflin 2000). The NTS receives cardio-pulmonary vagal inputs from small-diameter afferents responding to mechanical distension (lung stretch, group III fibers) and noxious stimuli/immune processes (lung irritants/cytokines, via group IV-fibers/nociceptors) leading to efferent vagal activity that evokes airway defensive reflexes (Zyuzin and Jendzjowsy 2022). The NTS also receives telencephalic inputs from a large array of structures (Gasparini et al. 2020; Holt 2022; Toney and Mifflin 2000). Direct projections from the cerebral cortex to the NTS have been identified (Jean 1991).

Outputs. At the level of the area postrema (AP), axon collaterals of most small NTS cells (soma <150 μm2) establish excitatory or inhibitory local micro-circuits likely to control the activity of nearby NTS cells and to transfer peripheral signals to efferent projection neurons. At least two cell types with efferent projections from the cNTS were distinguished: (i) a greater numbers of small cells, apparently forming local excitatory micro-circuits via recurrent axon collaterals, which project specifically and unidirectionally to the lateral parabrachial nucleus (lPBN); and (ii) much less numbers of cells likely to establish multiple global connections with a wide range of brain regions, including the ventro-lateral medulla (VLM), HYP, CeA, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), spinal DH, brainstem RF, LC, PAG and peri-ventricular diencephalon (Kawai 2018). The NTS also projects to the PBN, ventro-lateral reticular formation, raphé nuclei, motor nuclei of several cranial nerves, and others, and long connections to diencephalic and telencephalic structures,spinal cord (Holt 2022).

5.4. Parabrachial Nucleus (PBN)

The PBN surrounds the superior cerebellar peduncles in the dorso-lateral pons. The PBN is a collection of cell groups that, in rodents, can be divided into more than a dozen sub-nuclei based on cytoarchitecture. The medial PBN (mPBN) comprises populations of neurons heterogeneous in size and morphology, whereas the lPBN includes several homogeneous groups, which are also characterized by differential connectivity and neurochemistry and contains numerous co-localized peptides, including CGRP, SP, NT, and dynorphin (Chiang et al. 2019).

Functions. The PBN nuclei are involved in many homeostatic functions including nociception, chemoreception and autonomic control. The lPBN is required for escape behaviors and aversive learning in response to noxious stimulation (Chiang et al. 2020).

Nociceptive Inputs. The PBN receives substantial projections from nociceptive neurons in the contralateral superficial DH, and less dense inputs from the ipsilateral superficial DH and deeper lamina (Peng et al. 2023). The PBN, particularly lPBN, is the primary supraspinal target of nociceptive, pruritic and thermal signals transmitted via the SPT from the trigeminal and spinal DHs. The STTr sends collaterals to PBN (Kuner and Kuner 2021). The PBN is reciprocally connected with CeA, BNST, and multiple HYP nuclei, including the preoptic area (POA). This hyper-excitability appeared in part to reflect a loss of recurrent inhibition from the CeA. CeA not only receives a significant projection from lPBN, but also sends a dense inhibitory reciprocal connection back to lPBN (Chiang et al. 2019). – In mice, catecholaminergic input from the cNTS caused amplification of PBN activity and their sensory afferents. Noxious mechanical and thermal stimuli activated cNTS neurons and produced prolonged NA transients in PBN. Similar NA transients could be evoked by focal electrical stimulation of cNTS, a region that contains the NA A2 cell group that projects densely on PBN. A2 neurons of the cNTS increase excitability and potentiate responses of PBN neurons to sensory inputs (Ji et al. 2023).

Outputs from the PBN are widespread and complex. Major outputs target the paraventricular and gustatory THAL, the IC, intra-limbic (IL) PFC and pre-limbic (PL) PFC, with direct projections to the CeA and BNST and, through a THAL relay, to the IC, implicating PBN in both emotional and autonomic aspects of pain. Thus, stimulation of the PBN connections with CeA and BNST drove avoidance behavior (real-time place aversion) and aversive learning Activation of efferent projections to the ventro-medial hypothalamus (vmHYP) or lateral peri-aqueductal gray (lPAG) drove escape behaviors, whereas activation of lPBN efferents to the BNST or CeA generated an aversive memory. lPBN is also related to motor functions. Thus, activation of the lPBN projections to the caudal-dorsal medullary RF facilitated motor responses evoked by noxious stimulation, particularly during inflammation. Stimulation of the projections to vmHYP and PAG evoked running and jumping. PBN projects to the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of HYP and may play a role in neuro-endocrine-autonomic integration. lPBN projects to the PAG and to the RVM, both of which are implicated in descending pain modulation (Chiang et al. 2019, 2020). PBN projects directly to the RVM. Under physiological conditions and when exposed to acute pain stimuli, the contralateral PBN transmits signals to the RVM ON- and OFF-cells and then triggers acute hyperalgesia, while the ipsilateral PBN is involved in the RVM ON-and OFF-cells-induced modulation of persistent inflammation and chronic pain (Peng et al. 2023). lPBN neurons with strong nociceptive inputs from the DH project to the capsular part of the CeA, which is an important structure linking nociception and emotion. The lPBN to CeA synaptic transmission is enhanced in various pain models. In rats, light stimulation evoked monosynaptic excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs), with very small latency fluctuations, followed by a large polysynaptic inhibitory postsynaptic current in AMY neurons. Intra-plantar formalin injection at 24 h before slice preparation significantly increased EPSC amplitude in late firing-type CeA neurons. This indicate that direct monosynaptic glutamatergic inputs from the lPBN not only excite CeA neurons but also regulate CeA network signaling through robust feed-forward inhibition, which is under plastic modulation in response to persistent inflammatory pain (Sugimura et al. 2016). – A sub-population of lPBN neurons relays nociceptive signals from the spinal cord to the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr). Pain decreases the activity of many ventral tegmental area (VTA) DA neurons. lPBN-targeted and nociception-recipient SNr neurons regulate VTA DA activity directly through feedforward inhibition and indirectly by inhibiting a distinct sub-population of VTA-projecting lPBN neurons, thereby reducing excitatory drive to VTA DA neurons. Correspondingly, ablation of SNr-projecting lPBN neurons suffices to reduce pain-mediated inhibition of DA release in vivo (Yang et al. 2021).

5.5. Cerebellum

In human neuroimaging, the cerebellum was consistently activated after a peripheral nociceptive stimulus, be it electrical, laser, capsaicin, or other types of nociceptive stimulation, the activation sites mainly involving the vermis (in lobules IV–V), the ipsilateral cortex (lobules IV–VI, Crus I), and the contralateral cortex (lobule VI, Crus I) (Welman et al. 2018).

Beyond a role in nociception, the cerebellum has been implicated in a number of functions, including oculomotor control, control of upright stance and locomotion, reaching and grasping and speech, timing and coordination of movement, control of motor-cortex excitability, prediction of sensory consequences of actions, error detection and correction, motor learning, classical conditioning (e.g. eyeblink conditioning), and even reward, language, and social behavior, emotional, motivational and cognitive functions (Dibaj and Windhorst 2024a). The cerebellum also has a role in pain processing and/or modulation, possibly due to its extensive connections with the PFC and brainstem regions involved in descending pain control (Adamaszek et al. 2017; Baumann et al. 2015; Ong et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2022). The cerebellum also has bi-directional connections to the HYP, which may be involved in feeding, cardio-vascular, osmotic, respiratory, micturition, immune, emotion, and other non-somatic regulation (Zhu et al. 2006).

Nociceptive Inputs. Animal studies suggested spinally projecting multi-sensory inputs from the skin, including tactile group III and nociceptive group III and IV fiber (Welman et al. 2018). For example, in cats, stimulation of cutaneous group III and IV fiber nociceptor afferents activated climbing fibers (CFs) that terminate on Purkinje cells (PCs) in the cerebellar anterior lobe ipsilateral to stimulation. Group IV afferents conveyed neural input through the postsynaptic dorsal columns as part of a proposed spino-olivo-cerebellar (SOC) pathway. In addition to CF input, group IV fiber input may also act through mossy fibers (MFs) to reach PCs. In rats, noxious colo-rectal distention activates visceral neurons in the lateral medullary RF, including several with direct projections to the cerebellar vermis. In addition, noxious visceral stimulation can modulate PC activity in the posterior cerebellar vermis. However, what pathway conveys these signals is yet unknown (Moulton et al. 2010). In rodents and cats, stimulation of cutaneous and visceral nociceptors and group III and/or group III/IV afferents can activate and modulate PC activity. At least two possible nociceptive spino-cerebellar pathways have been proposed: (i) a SOC pathway that conveys nociceptive group III and group IV fiber input to PCs in the cerebellar anterior lobe ipsilateral to stimulation, and (ii) a spino-ponto-cerebellar (SPC) pathway conveying group IV fiber input to PCs in the cerebellar vermis. In addition to sensory afferent input, the cerebellum receives input from brain areas associated with nociceptive processing, including cognition, affect, and motor function. With the cerebellum receiving both descending information from other brain areas and ascending nociceptive information from the spinal cord, the structure is ideally positioned to be influenced by, or to influence, the processing of pain (Baumann et al. 2015).

Other Connections. In toto, the cerebellum has extensive connections to multiple CNS regions: S1, premotor cortex (PM), mPFC, IC, ACC, hippocampus (HIPP), AMY, THAL, HYP, RF, red nucleus (nucleus ruber: NRu), PBN, PAG, spV, trigeminal ganglion, LC, vestibular nuclei, and spinal cord. Among these are several pain-related regions (Wang et al. 2022). Nociceptive signals also reach the cerebellum (Moulton et al. 2010; Saab and Willis 2003). The cerebellum is reciprocally connected to the PAG, an anti-nociceptive processing center (Wang et al. 2022).

Role in Nociception/Pain. The functional role of the cerebellum in pain processing remains largely unclear. One widely accepted idea is that cerebellar activity is related to the fine-tuning of the motor output when we experience pain, in order to protect it from further harm. However, a role in pain anticipation, in the inhibition of pain, and in perceiving pain induced in others has also been posited. Many questions remain open. One question is whether the cerebellum is involved in modulating the processing of the incoming nociceptive signals or in the preparation and execution of a motor response to the nociceptive signal. Another question is whether it is invvolved in producing tasks that are localization-independent, like pain inhibition and the production of warning signals, or whether it is involved in the precise localization and precise movement planning in response to the nociceptive signals. In the latter case, a more detailed processing of the pain signal would be required that would require a precise somatotopical organization (Welman et al. 2018).

5.6. The PAG-Triad Connection

Extensive interconnections between the ANS, endocrine, somatic and limbic networks orchestrate pain modulation, stress responses, behavioral arousal, emotion, homeostasis, cardio-vascular and respiratory control, and micturition and defecation reflexes. This system receives various inputs from diverse sources, including modulatory input from cholinergic (ANS), monoaminergic, and peptidergic neurons, as well as signals mediated by NO, purines, endocannabinoids, and neurosteroids. Visceral inputs regulate autonomic output through both the sympathetic and parasympathetic pre-ganglionic neurons in the forebrain arousal system, medulla and, spinal cord. The central ANS includes monoaminergic neurons in the brainstem RF and nuclei that use as neurotransmitters and neuromodulators monoamines such as dopamine (DA), adrenaline and noradrenaline (NA), 5-HT, and histamine (Delbono et al. 2022).

Brainstem structures of major importance in the present context are the following: PAG, RVM, CVLM, DA neurons in HYP, substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and VTA, NA LC, 5-HT neurons in the raphé nuclei (RN).

The PAG sends strong inputs to the RVM, which by intricate connections is integrated with the CVLM and DReN into a triad (Martins and Tavares 2017)..

5.6.1. Peri-Aqueductal Gray (PAG)

The midbrain PAG is a cell-dense region surrounding the midbrain aqueduct. It shows a high degree of anatomical and functional organization, which takes the form of longitudinal columns of afferent inputs, output neurons and intrinsic interneurons (Bandler and Shipley 1994; Koutsikou et al. 2017).

Inputs. Ascending inputs come from the STTr (Kuner and Kuner 2021; Figure 2). The ventro-lateral PAG (vlPAG) receives inputs from regions that are targets of the ascending nociceptive fibers, including the PBN and spinal cord. The lPAG receives direct inputs from the DH and spV organized in a roughly somatotopic map, with orofacial afferents terminating rostrally and afferents from the legs terminating caudally (Mills et al. 2021). – The cortical projections to the PAG originate from the PFC, in particular, from the mPFC (BAs 25, 32), the dorso-medial convexity of the medial wall (BA 9) extending into the ACC (BA 24), and the posterior orbito-frontal/anterior IC (BA 13, 12) (Ong et al. 2019). In the cat, significant sources of cortical PAG projections are the somatosensory cortex, frontal cortex, IC, and CC. Tract paths could be defined between the PFC, AMY, THAL, HYP and RVM bilaterally, and the PAG. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has shown that the vlPAG is functionally connected to brain regions associated with descending pain modulation including the ACC, upper pons/medulla (Bouchet and Ingram 2020; Ong et al. 2019; Ossipov et al. 2014; Vázquez-León et al. 2021; Yetnikoff et al. 2014). – The PFC-AMY-dorsal PAG-pathway may mediate fear-conditioned analgesia, i.e., a reduction in pain response upon re-exposure to a context, previously paired with an aversive stimulus. The mPFC-PAG projection plays a role in modulation of autonomic responses to pain. In addition, the PAG receives inputs from the BNST, the midbrain retro-rubral field (RRF) and VTA. – Particularly important inputs reach the PAG indirectly from the PFC. fMRI revealed that the vlPAG is functionally connected to brain regions associated with descending pain modulation including the ACC, upper pons/medulla, whereas the lPAG and dorso-lateral PAG (dlPAG) are connected with brain regions implicated in executive functions, such as the PFC, striatum, and HIPP. In vivo tracing of neuronal connections using probabilistic tractography seeded in the right dlPFC and left rostral ACC (rACC) showed that stronger placebo analgesic responses are associated with increased mean fractional anisotropy values in white matter tracts connecting the PFC with the PAG. Tensor imaging showed that tract paths could be defined between the PFC, AMY, THAL, HYP, PAG and RVM bilaterally. The PFC-AMY-dPAG pathway may mediate fear-conditioned analgesia, i.e., a reduction in pain response upon re-exposure to a context, previously paired with an aversive stimulus. The mPFC-PAG projection also plays a role in modulation of autonomic responses to pain (Ong et al. 2019).

Outputs. The PAG sends descending outputs to the pons, cerebellum, medulla oblongata (Figure 3) and spinal cord (Yetnikoff et al. 2014). The vlPAG projects to the mPFC, lateral septum, BNST, HIPP, magnocellular basal forebrain (BFB), caudate putamen, NAc, AMY (CeA), to the substantia nigra (SN), lateral habenula (lHb), VTA and the RVM (Bouchet and Ingram 2020; Yetnikoff et al. 2014). The pain modulation results from descending, excitatory and inhibitory, onnections from the PAG to the RVL, NRM and other brainstem structures which in turn send glutamatergic, GABAergic, 5-HT and enkephalin (ENK) projections to the spinal cord (Lamotte et al. 2021; Lau and Vaughan 2014). Via the RVM, the PAG exerts both anti- and pro-nociceptive influences on nociceptive signal tramission in the DH or spV. The endogenous pain-modulation structures are strongly interconnected, e.g., LC and SRD, which also send direct projections to the DH and spV modulate nociception (Mills et al. 2021). Under normal conditions, PAG output neurons to the RVM are inhibited by GABA. Removal of this inhibition resulted in activation of the descending pain modulatory circuit and analgesia. The assumption is that this disinhibition promotes excitatory neurotransmission from the PAG to RVM. Opioid-triggered analgesia was mediated by projections from the vlPAG to RVM, while non-opioid-triggered analgesia was elicited by projections of the lPAG and dlPAG to RVM (Peng et al. 2023). However, opioid receptors are expressed on both GABAergic and glutamatergic terminals in the PAG and both cell populations project to RVM. Thus, PAG to RVM connections are more complicated than simply eliciting disinhibition of excitatory descending projections and probably reflect the existence of parallel circuits that contribute to the bi-directional control of pain mediated by the RVM (Bouchet and Ingram 2020). The PAG has indirect routes to DH via the LC and NRM (Willis and Westlund 1997).

Functions. The PAG plays a crucial role in conveying the modulatory influences from higher brain regions involved in aspects of pain responses such as cognition and emotion, including the PFC, IC and the AMY. The PAG collects the modulatory influences from these areas and uses the RVM as a relay to indirectly target the spinal cord (Martins and Tavares 2017). The PAG columns serve various functions. Stimulation of the vlPAG produces opioid-mediated analgesia, as well as freezing and quiescent behaviors, whereas stimulation of the lateral column and more dorsal columns produce escape behaviors such as jumping and flight responses (Bouchet and Ingram 2020; Mills et al. 2021). Overall, PAG functions are related to pain modulation, anxiety, panic, unconditioned, conditioned, as well as learned behaviors such as fear, vocalization, food intake, and sexual behavior, and the integration of autonomic responses. PAG neurons integrate negative phenomena such as anxiety, stress, and pain with the autonomic, neuro-endocrine, and immune systems to facilitate responses to threat (Vázquez-León et al. 2021). The PAG plays a coordinative role in the management of threat, arousal, anxiety, fear, and defence systems for survival by organizing changes in sensory processing including anti-nociception, ANS activity and motor behavior, e.g., `fight or flight´ or `freezing´ (Koutsikou et al. 2017; Roelofs 2017). Different classes of threatening or nociceptive stimuli trigger distinct co-ordinated patterns of musculo-skeletal, autonomic and anti-nociceptive adjustments by selectively targeting specific PAG columnar circuits (Bandler and Shipley 1994).

Inescapable and Escapable Pain. Deep pain evokes passive emotional coping that includes quiescence and vaso-depression. Inescapable, persistent pain generated by nociceptive inputs from deep structures drive neurons in the vlPAG that co-ordinate passive emotional coping. By contrast, brief escapable cutaneous pain evokes an active emotional coping: the fight-or-flight response, which activates the dlPAG that co-ordinate active coping strategies. Hence, it has been suggested that it is the behavioral significance of the nociceptive input, rather than its organ of origin per se, that determines the characteristics of the affective response. Differential representations of escapable and inescapable pain in the PAG may extend to distinct representations of `first pain´ and `second pain´, as indicated by the columnar distribution of neurons activated by inputs from group III (Aδ) and IV (C) nociceptive afferents (Lumb 2002).

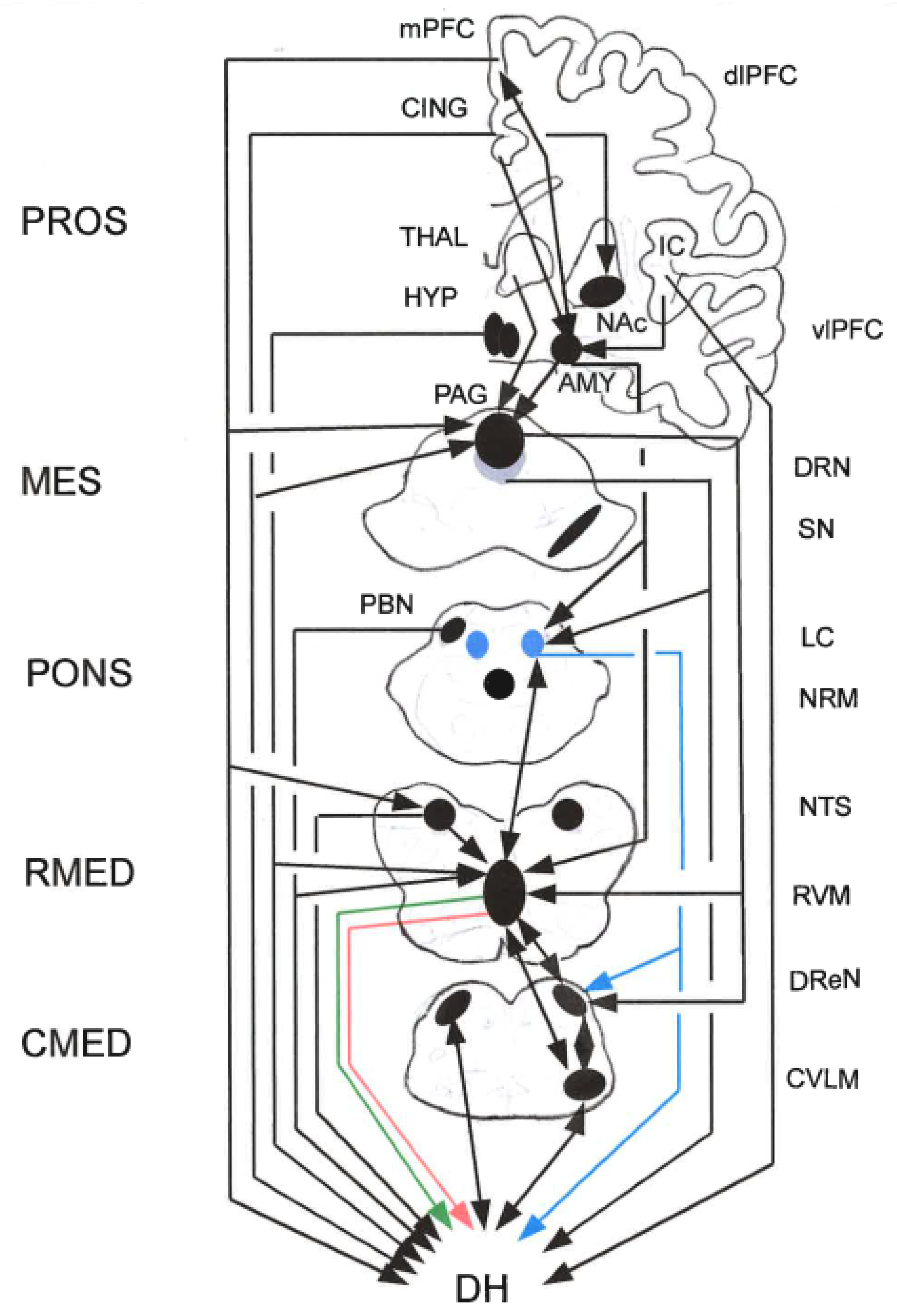

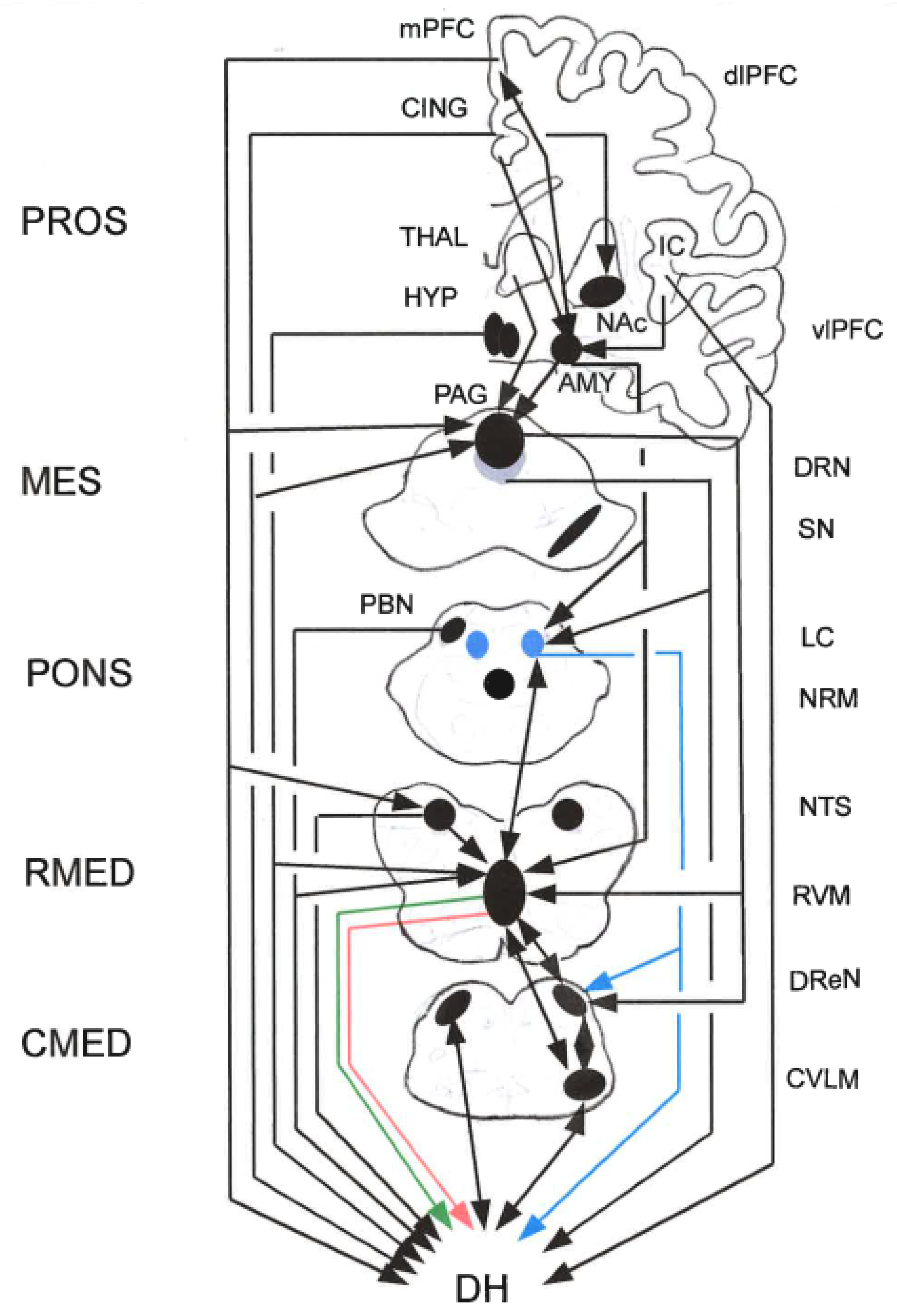

Figure 3.

Simplified and rarefied scheme of the approximate locations of some nuclei and brain structures and of connections involved in the descending control of nociceptive transmission in the spinal DH. The sections are not scaled. Some structures (e.g., raphé nuclei) distribute quite far rostro-caudally and may occur in two cross-sections, which is not shown for graphical reasons. Connections often are composed of parallel fiber systems, but are here lumped and represented by arrowed lines. Connections may be excitatory (green lines) or inhibitory (red lines). For example and importantly, the connections from RVM to DH are both facilitory and inhibitory. Other arrowed lines, e.g., from HYP to DH, comprise DA and OXT influences. Therefore, and for graphical reasons, most lines are indifferently black. Abbreviations: A1: NA A1 cell group; AMY: amygdala; BG: basal ganglia; CING: cingulate cortex; CMED: caudal medulla; CVLM: caudal ventro-lateral medulla; dlPFC: dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex; DH: dorsal horn; DReN: dorsal reticular nucleus; DRN: dorsal raphé nucleus; HYP: hypothalamus; IC: insular cortex; LC: locus coeruleus; MES: mesencephalon; mPFC: medial prefrontal cortex; NRM: nucleus raphé magnus; NTS: nucleus tractus solitarii; PAG: peri-aqueductal gray; PBN: parabrachial nucleus; PROS: prosencephalon; RMED: rostral medulla; RVM: rostral ventro-medial medulla; SN: substantia nigra; THAL: thalamus; vlPFC: ventro-lateral prefrontal cortex (Data from papers cited in the text).

Figure 3.

Simplified and rarefied scheme of the approximate locations of some nuclei and brain structures and of connections involved in the descending control of nociceptive transmission in the spinal DH. The sections are not scaled. Some structures (e.g., raphé nuclei) distribute quite far rostro-caudally and may occur in two cross-sections, which is not shown for graphical reasons. Connections often are composed of parallel fiber systems, but are here lumped and represented by arrowed lines. Connections may be excitatory (green lines) or inhibitory (red lines). For example and importantly, the connections from RVM to DH are both facilitory and inhibitory. Other arrowed lines, e.g., from HYP to DH, comprise DA and OXT influences. Therefore, and for graphical reasons, most lines are indifferently black. Abbreviations: A1: NA A1 cell group; AMY: amygdala; BG: basal ganglia; CING: cingulate cortex; CMED: caudal medulla; CVLM: caudal ventro-lateral medulla; dlPFC: dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex; DH: dorsal horn; DReN: dorsal reticular nucleus; DRN: dorsal raphé nucleus; HYP: hypothalamus; IC: insular cortex; LC: locus coeruleus; MES: mesencephalon; mPFC: medial prefrontal cortex; NRM: nucleus raphé magnus; NTS: nucleus tractus solitarii; PAG: peri-aqueductal gray; PBN: parabrachial nucleus; PROS: prosencephalon; RMED: rostral medulla; RVM: rostral ventro-medial medulla; SN: substantia nigra; THAL: thalamus; vlPFC: ventro-lateral prefrontal cortex (Data from papers cited in the text).

5.6.2. Rostral Ventro-Medial Medulla (RVM)

The RVM mainly consists of the midline NRM, the nucleus reticularis giganto-cellularis-pars alpha, and the nucleus paragiganto-cellularis lateralis, as well as GABAergic and glycinergic cell populations, all of which project diffusely to the spV and to superficial and deep DH layers (Heinricher et al. 2009; Mills et al. 2021; Ossipov et al. 2014; Peng et al. 2023). The RVM contains three populations of neurons, ON-cells, OFF-cells, and NEUTRAL cells that show different responses to noxious stimuli and are recruited by higher structures to enhance or inhibit pain (Heinricher et al. 1987, 2009; Peng et al. 2023).

Inputs. Nociceptive information is transmitted to the RVM through specific groups of spinal ascending neurons. The RVM also receives nociceptive-related inputs from a dense projection from the PAG, from the PBN, THAL, HYP (directly and indirectly), and the AMY, and further inputs from a variety of other cortical and sub-cortical areas as well as from the NA LC (Bouchet and Ingram 2020; Ossipov et al. 2014; Peng et al. 2023). The output from the CeA targets the RVM and PAG, which are crucial for mediating behavioral coping responses in the face of threat (Kuner and Kuner 2021). When experiencing noxious heat stimuli or continuous neuropathic pain, not only is the contralateral RVM but also the ipsilateral/median RVM activity increased, as indicated in a fMRI study of human supraspinal structures (Peng et al. 2023). – The AMY has direct and indirect projections to the RVM, and thereby influences the descending pain modulatory system. After micro-injection of morphine into different sites of the AMY, several findings suggest that its analgesic effects were mainly attributed to the direct projections from the AMY to the RVM. Infusing morphine into the BLA increased OFF-cell activity, modestly decreased ON-cell activity, strongly attenuated the OFF-cell pause, and increased TFL (Peng et al. 2023).

In humans, fMRI studies showed that somatic and visceral noxious stimulation led to activation of brainstem regions including the PAG and RVM, and at the primary nociceptive synapse, at either the spV or DH, during noxious muscle and cutaneous inputs. There was an association between the activation in, or signal coupling between, these regions and the intensity of pain reported during acute noxious inputs (Mills et al. 2021). fMRI also showed that when experiencing noxious heat stimuli or continuous neuropathic pain, not only the contralateral RVM but also the ipsilateral/median RVM activity was increased. In animals, extracellular recordings showed changes in RVM neuronal responses to nociceptive stimulation. Pro-nociceptive ON-cells increased activity immediately before facilitation of the withdrawal response. Anti-nociceptive OFF-cells decreased their relatively high spontaneous activity up to a pause, which triggered the nociceptive response. NEUTRAL cells did not respond to painful stimuli (Heinricher et al. 2009; Peng et al. 2023).

Outputs. RVM neurons project diffusely to the spV and, via ventro-lateral funiculus and spinal dorso-lateral funiculus separately, to DH laminae important in nociceptive processing, including superficial and deep DH layers that receive nociceptor primary afferents (Heinricher et al. 2009; Mills et al. 2021; Peng et al. 2023). It has been suggested that RVM has a distinctive role as the `main gatekeeper of descending pain modulation´, bi-directionally facilitating or inhibiting spinal nociceptive transmisison (Peng et al. 2023). ON-cell firing increased and OFF-cell firing decreasesd while NEUTRAL cells showed no responses to nociceptive stimuli (Heinricher et al. 1987).

PAG-RVM Connections. PAG neurons project extensively to RVM neurons, which in turn project to the spinal cord, and two-thirds of these reticulo-spinal neurons, appear to be GABAergic (contain GAD67 immuno-reactivity). The majority of PAG fibers that contact RVM reticulo-spinal GAD67-immuno-reactive neurons also contained GAD67 immuno-reactivity. Thus, there is an inhibitory projection from PAG to inhibitory RVM reticulo-spinal neurons. There were also PAG projections to the RVM, though, that did not contain GAD67 immuno-reactivity. Similar to the pattern above, both GAD67- and non-GAD67-immuno-reactive PAG neurons projected to RVM ON-, OFF-, and NEUTRAL cells in the RVM. These inputs included a GAD67-immuno-reactive projection to GAD67-immuno-reactive ON-cells and non-GAD67 projections to GAD67-immuno-reactive OFF-cells. This pattern is consistent with PAG neurons producing anti-nociception by direct excitation of RVM OFF-cells and inhibition of ON-cells (Morgan et al. 2008).

5.6.3. Caudal Ventro-Lateral Medulla (CVLM)

In several species including rat, mouse, cat, monkeys and man, the CVLM is located in the ventro-lateral quadrant of the caudal-most aspect of the medulla oblongata (Figure 3). The ascending projections from the spinal cord to the CVLM are anatomically segregated, with the lateral CVLM (CVLMlat) receiving mainly afferents from the superficial DH, namely from nociceptively responsive neurons located in lamina I. An important proportion of VLMlat-projecting neurons is located at lamina II, which appears to be a special feature of this spino-fugal pathway. Circuits capable of conveying CVLM-elicited anti-nociception include a direct reciprocal CVLM-spinal loop (Figure 3). Additionally, the CVLM is also bi-directionally connected with both the RVM and DReN (below), building a cooperative `triad´ (Martins and Tavares 2017).

Nociceptive Inputs. In pentobarbitone-anesthetized control and monoarthritic rats, electrophysiological recordings were used to characterize neuronal responses to noxious pinch, heat, cold and colo-rectal distension. CVLM neurons gave excitatory, inhibitory or no response to noxious test stimulation. Response patterns for part of the neurons varied with sub-modality of test stimulation; e.g., a cell with an excitatory response to heat could give no or an inhibitory response to cold (Pinto-Ribeiro et al. 2011). Visceral and somatic types of pain exhibit crucial differences not only in the experience, but also in their peripheral and central processing. In urethane-anesthetized adult male Wistar rats, responses of CVLM neurons were investigated to visceral (colo-rectal distension, CRD) and somatic (squeezing of the tail) noxious stimulations. The CVLM of healthy control rats, along with harboring of cells excited by both stimulations (23.7%), contained neurons that were activated by either visceral (31.9%) or somatic noxious stimuli (44.4%) (Lyubashina et al. 2019). In anesthetised rats, following both direct muscle stimulation and L5 ventral-root stimulation, fatigue-related c-fos gene expression was most prominent in the DH of the ipsilateral L2-L5 segments and within the ipsilateral NTS, the CVLM and RVL, and the intermediate reticular nucleus, and contralaterally (Maisky et al. 2002). Note the muscle fatigue activates group III/IV afferents.

Other Inputs. The CVLMlat receives inputs from the somatosensory and motor cortices, the IL PFC, IC, and limbic cortices, the CeA, lateral (lHYP), posterior HYP (pHYP), PVN, PAG, red nucleus, PBN, NRM, NTS, lateral reticular nucleus (LRN), dorsal and ventral medullary RF, and the lateral cerebellar nucleus (Cobos et al. 2003).

Outputs. The CVLMlat projects to the PAG, red nucleus or lateral cerebellar nucleus (Cobos et al. 2003). The projections to spinal DH laminae involved in nociceptive transmission originate exclusively in the CVLMlat. The CVLMlat is integrated in a disynaptic pathway involving spinally projecting pontine NA A5 neurons, which appears to convey α2-adreno-receptor-mediated analgesia produced from the VLM. The descending CVLMlat-spinal pathway targets lamina I, IV–V and X. Terminal boutons from lamina I neurons on CVLMlat neurons, that project to the spinal cord, suggest that the ascending nociceptive input from the spinal cord directly activates CVLMlat neurons. Electrophysiological mapping of the VLM has shown that it contains inhibitory neurons (OFF-like neurons) along with excitatory cells (ON-like cells) which indicates that the descending modulation from the VLM may include facilitatory modulation, along with the inhibitory effects. Neurons in the CVLMlat and in DH lamina I are reciprocally connected by a closed loop that is likely to mediate feedback control of supraspinal nociceptive transmission (Martins and Tavares 2017; Tavares and Lima 2002).

The CVLMlat is also activated in response to increases in blood pressure. Increases in blood pressure are a feature of the `fight or flight”´ response. Altogether, the VLM is an integrative center which is involved in producing the adequate pain, motor and cardio-vascular responses (Martins and Tavares 2017).

5.6.4. Dorsal Reticular Nucleus (DReN)

The DReN is located in the caudal-most aspect of the medulla oblongata in several species including rat, cat, monkey and man. It is located in the most caudal, dorso-lateral portion of the medulla (Figure 3; Martins and Tavares 2017). DReN neurons are reciprocally connected with DH lamina I neurons, thus forming a reverberative nociceptive circuit.

Inputs. The DReN is targeted from fibers originating from deeper layers in the spinal cord, namely from laminae IV–V, which specifically terminate in the lateral part of the DReN, and from lamina VII which terminate at the medial part of the nucleus. DReN neurons are activated only or mainly by noxious stimulation, whose intensity is reflected in the firing rate. They have large receptive fields that often cover the whole body surface. The DReN also receives projections from the A1 and C1 cell groups (Lima and Almeida 2002; Martins and Tavares 2017).

Outputs. The DReN is reciprocally connected with sensory medullary nuclei (e.g., nucleus cuneatus and spinal trigeminal nucleus pars caudalis), and with many brainstem and diencephalic nuclei involved in anti-nociception and/or autonomic control. Anterograde tracing showed that fibers and terminal boutons labeled from the DReN were located predominately in the brainstem, although extending also to the forebrain. In the rat medulla oblongata, anterograde labeling appeared in the RVM, CVLM, NTS, orofacial motor nuclei, and inferior olive (IO). Labeling was also present in the LC, NA A5 and A7 cell groups, PBN and deep cerebellar nuclei. In the midbrain, it was located in the PAG, SN, deep mesencephalic, oculomotor and anterior pretectal nuclei. In the diencephalon, fibers and terminal boutons occurred mainly in THAL nuclei, and in the HYP arcuate (HYP ARC), PVN, lateral, posterior, peri- and paraventricular areas. Telencephalic labeling was less intense and concentrated in the septal nuclei, globus pallidus and AMY. This suggests that the DReN is possibly implicated in the modulation of: (i) the ascending nociceptive transmission involved in the motivational-affective dimension of pain; (ii) the endogenous supraspinal pain control system centered in the PAG -RVM-spinal cord circuitry; (iii) the motor reactions associated with pain (Leite-Almeida et al. 2006). The medullary DReN is also reciprocally connected with the spinal DH (Leite-Almeida et al. 2006; Martins and Tavares 2017).

DH-DReN-Cerebellum Connection. The cerebellum receives input from nociceptors, which may serve to adjust motor programmes in response to pain and injury. A significant proportion of spino-reticular DH cells projecting to the DReN respond to noxious mechanical stimuli. One of the functions of this pathway may be to provide the cerebellum with nociceptive information (Huma et al. 2015).

5.6.5. Case Report: Acute Thoracoabdominal Trauma with Severe Pain and Autonomic Dysregulation

A 30-year old male patient arrived in the Emergency Department in acute distress following blunt trauma (high-speed motor vehicle collision) to the thorax and abdomen. He was conscious but exhibited shallow breathing, diaphoresis, tachycardia (HR 135 bpm), and fluctuating blood pressure (ranging from 90/60 to 150/100 mmHg). He reported excruciating, stabbing pain rated 10/10 (visual analogue scale), radiating from the lower ribs to the epigastrium. His voice was weak, and he appeared anxious and intermittently unresponsive. Neurological findings were hyperalgesia over lower thoracic dermatomes, reflexive guarding of abdominal muscles, and panic-like behavior. CT scan showed Rib fractures (T7–T10), and hepatic laceration. Ketamine infusion, high-flow oxygen therapy, and fluid resuscitation were initiated. Psychological support was necessary to manage affective amplification of pain. Within 48 hours, pain scores dropped to 4/10, cardiovascular parameters stabilized, and the patient regained emotional composure. By day 4, he was ambulating with mild discomfort and discharged with outpatient pain and trauma follow-up.

5.7. Hypothalamus (HYP)

The HYP is a diencephalic structure in the BFB, consisting of several nuclei (Takayanagi and Onaka 2021). The HYP comprises thousands of distinct cell types that form redundant yet functionally discrete circuits (Fong et al. 2023).

Functions. The HYP is involved in multiple functions serving homeostasis, which is defined as the maintenance of the internal environment that includes physiological variables such as heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature and blood sugar concentration within a certain narrow ranges. Specific functions include stress responses, control of arousal, regulation of sleep/wake cycles, regulation of body temperature and metabolism, feeding behavior, and reproductive behavior etc. (Takayanagi and Onaka 2021).

Nociceptive Inputs. The STTr sends collaterals to HYP, also indirectly via the noradrenergic A1 cell group (Figure 2; Kuner and Kuner 2021). The HYP receives converging nociceptive and visceral inputs from the spinal DHs and trigeminal nuclei (Benarroch 2006; Jänig 2014), and direct and indirect (via PBN and NA A1 cells) nociceptive inputs from the STTr (Kuner and Kuner 2021). In mice, formalin injection induced significantly increased expression of fos in the PVN, among which OXT-containing neurons are one neuronal phenotype. Under inflammatory pain, neurons in the lPBN may play essential roles in transmitting noxious information to the PVN (Ren et al. 2024).

Other Inputs. The different HYP nuclei receive and emit differentiated inputs and outputs. Largely, in addition to nociceptive inputs, the HYP receives direct or indirect inputs from somatic and visceral sensory receptors of different kinds, as well as from the HIPP formation, gyrus cinguli, piriform cortex, OFC, mammilary body, septum, AMY, THAL, from retinal, olfactory and auditory fibers, from the brainstem RF, PAG, raphé nuclei, LC, and NTS (Brodal 1981).

Outputs. In part, the efferent HYP projections are reciprocal to the afferent inputs. Among `ascending´ connections, the mamillary tract to the anterior THAL nucleus is the most massive. Other efferents target the septum, HIPP, pulvinar, AMY, vlPAG, pretectal area, superior colliculi, midbrain RF, raphé nuclei, LC, NTS, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, pre-ganglionic visceral nuclei, inter-medio-lateral cell column (IML) of the spinal cord (Brodal 1981). There is a descending HYP-DH DA system. In the adult albino rat, cells in the PVN project to autonomic centers in the brainstem or in the spinal cord of the adult albino rat. Both OXT- and AVP-stained cells in the PVN project to the spinal cord and (or) to the dorsal vagal complex (Sawchenko and Swanson 1982).

Hypothalamic Dopamine (DA) Cell Cluster. The dorsal posterior HYP contains a DA cluster called A11 cell group. These neurons, approximately 300 in rats and 130 in mice, project to the neocortex which might be related to changes in the perception of ascending sensory information; 5-HT dorsal raphé nucleus (DRN), promoting cardio-vascular and sympathetic activity. They also send descending projections as the source of spinal DA. The terminals are most concentrated in the superficial sensory-related DH and inter-medio-lateral nucleus. The loss of A11 neurons causes a disinhibition of sensory inputs and favors the occurrence of abnormal visceral or muscular sensations. The spinal cord of rats, cats, monkeys, and humans express DA receptors D1, D2, and D3. DA and D2 agonists can depress the monosynaptic reflex amplitude, dependent on D3 receptors, since this effect was absent in D3 knockout mice. Hence, A11 modulatory neurons could hypothetically inhibit spinal somatosensory and sympathetic autonomic circuits (Klein et al. 2019).

5.8. Midbrain Dopamine (DA) Neurons

The midbrain DA complex comprises the SNc, VTA and RRF, which contain the A9, A10 and A8 groups of nigro-striatal, meso-limbic and meso-cortical DA neurons, respectively. Additionally, there are dorsal-caudal A10dc and rostro-ventral A10 extensions into the vlPAG and supra-mammillary nucleus, respectively. Where they intermingle, NA A8 cells are morphologically indistinguishable from cells in A9 or A10 cells, as are A9 and A10 neurons at any imaginary boundary between the VTA and SNc. Still, A8, A9 and A10 are structurally and functionally differentiated, as also reflected in the relatively distinct, albeit broadly overlapping, topographies and functions of their ascending projections. The A8–10 nomenclature refers explicitly to DA neurons, whereas the VTA, SNc, RRF are brainstem structures that also contain locally and distantly projecting neurons that utilize as transmitters, either co-expressed with DA or separately, GABA, glutamate, cholecystokinin (CCK) and NT and possibly as yet unknown compounds (Yetnikoff et al. 2014). In the VTA, the different kinds of neurons interact via intrinsic connections and have differentiated external inputs and outputs (Morales and Margolis 2017).

Functions. DA is a neurotransmitter, synthesized in both the CNS and the periphery. DA receptors are widely expressed in the body and function in both the PNS and the CNS. DA is not simply an excitatory or inhibitory neurotransmitter, since it can bind to different G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). The DA system plays important roles in neuromodulation, such as arousal, attention, motivation, affect, feeding, olfaction, hormone regulation, maternal and reproductive behaviors, sleep regulation, spatial memory function, motivation, reward, cognitive function, and influences the immune, cardio-vascular, gastro-intestinal, and renal systems, as well as movement and motor control. Regarding its physiological role (Klein et al. 2019).

5.8.1. General Inputs

In rodents and primates, SNc and VTA receive a large array of differentially distributed inputs from, among others, telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon, pons, medulla, and cerebellum, the connections varying in strength. Inputs to the RRF resemble those to the VTA (Kelly and Fudge 2018; Morales and Margolis 2017; Yetnikoff et al. 2014). For example, VTA DA neurons receive glutamatergic inputs from the mPFC, BNST, lHb, pedunculo-pontine tegmentum, latero-dorsal tegmental nucleus (LDT), PAG, DRN, GABAergic inputs from the ventral pallidum, lHYP, rostro-medial meso-pontine tegmental nucleus (for further inputs to glutamatergic and GABAergic cells see Morales and Margolis 2017).

5.8.2. Nocicpeptive Inputs

Midbrain DA neurons change their excitability upon noxious stimulation or relief from pain-like states. DA cells are preferentially activated by appetitive versus aversive stimuli. By an acute aversive stimulus (foot pinch), DA neurons in the VTA were uniformly inhibited and a non-DA neuronal population was excited. In rodents, DA neurons, particularly in the dorsal VTA, were inhibited by noxious foot shocks while in ventral VTA DA neurons, foot-shocks induced phasic excitation (Mitsi and Zachariou 2016). The meso-limbic DA system indirectly receives somatosensory inputs, including nociceptive inputs, from the lHYP mediated by the lHb. The lHYP-lHb pathway is necessary for nociceptive modulation of the DA system (Dai et al. 2022; Ogawa and Watabe-Uchida 2018). Furthermore, nociceptive signals from the spinal cord are relayed by a sub-population of lPBN neurons to the SNr. – In anesthetized rats, many DA neurons exhibited a short-latency response to noxious stimuli, which appears to be mediated by the nociceptive-recipient PBN. During the application of noxious foot shock, simultaneous extracellular recordings showed that the PBN neurons exhibited a short-latency, short-duration excitation to foot shock, while DA neurons exhibited a short-latency but slightly later inhibition, suggesting that the PBN is an important source of short-latency nociceptive input to the DA neurons (Coizet et al. 2010). Furthermore, nociceptive signals from the spinal cord were relayed by a sub-population of lPBN neurons to the SNr. SNr-projecting lPBN neurons are activated by noxious stimuli, and silencing them blocks pain responses in two different models of pain (Yang et al. 2021). In adult anesthetized female albino rats, extracellular recordings were obtained from neurons in the VTA, the SN, including the zona compacta (SNc) and the zona reticulata (SNr), and the midbrain RF. Based on electrophysiological characteristics, the neurons were divided into two types. Type I neurons, with relatively long spike durations and slow discharge rates, were confined to the VTA and SNc. Type II neurons, with shorter spike durations and faster discharge rates, were observed in the SNr and RF as well as the VTA and SNc. Aversive foot pinch (FP) and tail pinch (TP) elicited locomotion, sniffing and gnawing responses, and stimulation of the vaginal cervix (VC) eliciting lordosis responses, vocalization and immobility. For approximately two-thirds of the neurons, the effects of the three peripheral stimuli were similar, they were either activated or suppressed. This is consistent with the view that VTA and SN neurons integrate a number of central and peripheral inputs (Maeda and Mogenson 1982). In the anesthetized rats, a majority of 194 extracellularly recorded presumed DA neurons (78%) were inhibited by intensive electrical stimulation performed at the tail (PNS) and 15% were excited. Single-shock stimulation of the lHb inhibited 89% of the tested DAergic neurons, most of which (83.8%) were also inhibited by PNS. lHb stimulation increased PNS-induced inhibition of DA neurons and electrical destruction of ipsilateral lHb depressed their nociceptive responses. This may suggest that DAergic neurons the lHb shares a step in nociceptive projection to the SN (Gao et al. 1990). Using simultaneous extracellular single-unit recordings in the SN pars compacta and in the lHb of rats, of 45 pairs of neurons responding to peripheral nociceptive stimulation, 41 pairs of nigral DA neurons were inhibited by peripheral nociceptive stimulation, while lHb neurons were excited. In 14 pairs, when sweeps were triggered randomly by spontaneous spikes from lHb neurons, the spontaneous firing rate of the DA neurons during the first 250 ms after the sweep was much lower than rates after this time period. These cross-correlations between the spontaneous activities of these two nuclei suggest that the excitation of lHb neurons induced by peripheral nociceptive stimulation might be directly responsible for inhibition of nigral DA neurons (Gao et al. 1996).

5.8.3. Outputs

There are four main ascending pathways: nigro-striatal, meso-limbic, meso-cortical, and tubero-infundibular. The midbrain DA complex gives rise to a meso-limbic pathway to the limbic forebrain and orbito-frontal cortex (OFC) and a nigro-striatal pathway to the BG striatum. Generally, nearly every telencephalic region receiving DA innervation has a medial aspect innervated by the VTA and a lateral aspect innervated by the SNc, the two separated by a broad district in which VTA and SNc projections overlap. Still, SNc projects mainly to the ventro-medial caudate-putamen and to a lesser extent to cortical structures, AMY and the subthalamic nucleus (STN) (Morales and Margolis 2017; Yetnikoff et al. 2014). Furthermore, DA efferents target in particular the mPFC (Vander Weele et al. 2019). Spinally descending DA fibers originate from the HYP (Li et al. 2019; Lindvall et al. 1983; Puopolo 2019).

In humans, midbrain DA neurons from the VTA project to the PFC via the meso-cortical pathway and to the NAc via the meso-limbic pathway. These pathways constitute the meso-cortico-limbic system, which plays a role in reward and motivation. The VTA region also gives rise to DA projections to the AMY, HIPP, CC, and olfactory bulb. The meso-limbic DA system has been implicated in positive reward and appetite-motivated behaviors. However, aversive stimuli and stress may also lead to DA release by this same system, which might correspond to a generalized behavioral arousal involving seeking safety. In animal models, micro-injections of DA into the NAc increased locomotor activity, exploratory behaviors, conditioned approach responses, and anticipatory sexual behaviors. When a GABAA receptor antagonist was injected into the VTA, locomotion was increased. This phenomenon occurred because GABAergic neurons inhibited DA neurons and the antagonist blocked this inhibition. Therefore, enhanced DA function in meso-limbic system increased behavioral activity, while lesions of this system could eliminate exploratory and appetitive behaviors (Klein et al. 2019).

In rats anesthetised with halothane, 226 spontaneously active neurons were recorded from the SN. 112 neurons (50%) were nociceptive. Approximately equal proportions of nociceptive and non-nociceptive SN neurons projected to the THAL. The majority of nigro-striatal neurons were non-nociceptive (Pay and Barasi 1982). In the rat, immediately after foot-shock termination, extracellular DA concentrations were increased in the NAc shell but remained unaltered in the NAc core. Such activation, especially in the ventral striatum and NAc, also occurred after the application of acute noxious (thermal) stimulus. In rodents, voltammetry showed changes in NAc DA release upon termination of a noxious stimulus (tail-pinch). DA release in the NAc was promoted by noxious tail stimulation and local VTA micro-injection of capsaicin. On the other hand, non-DA neurons in the VTA of anesthetized rats were excited by aversive stimuli, including pain. Moreover, fMRI in both humans and rodents showed that the offset of a noxious stimulus increased the activation of the meso-limbic DA system. Micro-dialysis supported the hypothesis that pain alleviation is modulated by changes in DA concentrations in the NAc (Mitsi and Zachariou 2016).

5.9. Locus Coeruleus (LC) and Other Cell Groups

The brainstem contains a number of catecholamine nuclei and cell groups. Through action on α₁- and α₂-adrenoceptors, NA is involved in intrinsic control of pain (Pertovaara 2013).

5.9.1. Locus Coeruleus (LC)

The locus coeruleus (actually: caeruleus: celestial blue) is a cluster of relatively large neurons containing NA, located bilaterally in the brainstem just under the cerebellum and lateral to the fourth ventricle (Poe et al. 2020). Like other neuromodulatory structures, the LC contains an exceedingly small number of cells, yet projects to much of the brain. The human LC is estimated to contain approximately 30,000 neurons that provide NA to a substantial fraction of the brain´s 100 billion neurons. The LC is therefore well positioned to modulate a wide range of functions, including homeostasis, sensory processing, motor behavior, and cognition (Bari et al. 2019). Virtually all neurons within rodent and primate LC contain NA as the primary transmitter. However, multiple peptides co-localize within LC neurons, including vasopressin (AVP), STT, neuropeptide Y (NPY), ENK, NT, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and GAL. NA neurons project broadly throughout the neuraxis, from the spinal cord to the neocortex (Aston-Jones and Waterhouse 2016).

Inputs. Almost all areas of the neocortex project to the LC, with strong glutamatergic projections from the PFC and CRH projections from the AMY (Bari et al. 2019). Besides by noxious stimuli (below), the LC-NA neurons in behaving rats to monkeys respond to (even mild) non-noxious environmental stimuli of many modalities, including auditory, visual, proprioceptive and somatosensory stimuli, depending on the present vigilance state of the animal (Aston-Jones and Bloom 1981). All LC neurons receive inputs related to autonomic arousal, but distinct sub-populations can encode specific cognitive processes, presumably through more specific inputs from the forebrain areas. LC neurons receive inputs from many regions of the brainstem and forebrain, including the PFC, BNST, CeA, HYP PVN, NTS, nucleus paragigantocellularis (PG), and the nucleus prepositus hypoglossi (NPH) (Ross and van Bockstaele 2020). The PFC is a major source of input to LC, linking circuits involved in higher cognitive and affective processes to the LC efferent system (Berridge and Waterhouse 2003).

Nociceptive Inputs. The STTr projects to the THAL, but on its way, it sends collaterals to the brainstem RF, NA cell groups A1. A5-A7, that projects further to the HYP and many other structures (Kuner and Kuner 2019; Woulfe et al. 1990; below)). Noxious peripheral stimuli increase the activity in LC. In anesthetized rats, LC neurons were potently activated by foot shock, this effect being indirect because attenuated or blocked by pharmacologic blockade of the PG (Chiang and Aston-Jones 1993). In awake mice, upon exposure to acute nociceptive stimulation consisting of a pinch and application of heat (55 °C) to the tail, both stimuli resulted in rapid and transient (<15 s) increases in the activity of LC NA neurons while control stimuli did not induce any changes (Moriya et al. 2019).

Outputs. LC (A6 group) neurons send diffuse, but regionally specific, projections throughout the neuraxis where they release NA as a neurotransmitter and neuromodulator (Berridge and Waterhouse 2003; Foote et al. 1983; Valentino and van Bockstaele 2015). LC provides the sole source of NA to the neocortex and HIPP, but less strongly innervates the BG (Berridge and Waterhouse 2003). NA cells in groups A5, A7 in the ventro-caudal LC portion and the sub-coeruleus area (together with rostral C1 adrenergic neurons) belong to the `descending catecholaminergic system´, projecting to the spinal cord including the DH and sympathetic pre-ganglionic neurons in the thoracic segments. These neurons represent the efferent arm of the central sympathetic system that influences the sympathetic outflow (Kvetnansky et al. 2009). In part, LC projections are segregated into distinct output channels and have the potential for differential release and actions of NA on its projection targets, thereby enabling differentiated modulation of diverse behaviors and cognitive functions. There are also projections to motor areas, such as the motor cortex, BG, cerebellum and inferior olive (IO) (Poe et al. 2020).

Descending Pain Modulation. The LC is involved in the descending modulation of pain, mainly through direct spinal cord projections and effects on RVM activity via NAergic projections. Ventrally located LC neurons were labeled after injecting pseudorabies virus (PRV) into the RVM. Moreover, stimulation of LC NA neurons increased the release of NA and increased 1-adrenoceptor concentrations of α1-adrenoceptors (NAα1R) in NRM, leading to analgesia. By contrast, LC-NRM projecting NA neurons possibly induced hyperalgesia by activating NRM NAα1R. During opioid withdrawal, administration of the NAα1R antagonist prazosin in NRM significantly decreased the activities of LC NA projections and suppressed hyperalgesia. RVM ON-cells received LC NA inputs and contained NAα1R, which contributed to hyperalgesia during opioid withdrawal, while inhibition of NAα2R-expressing ON-cells by clonidine suppressed DAMGO-mediated analgesia instead of modulating hyperalgesia during opioid withdrawal. OFF-cells also received dense LC NA input, and mainly expressed NAα1R and some co-expressed NAα2R. Overall, this suggests that LC-RVM projections trigger not only anti-nociceptive but also pro-nociceptive effects by modulating RVM ON- and OFF-cells (Peng et al. 2023).

5.9.2. A and C Cell Groups

Ascending projections from spinal lamina I run through and terminate in brainstem regions that contain adrenergic/NA cells. In the Cynomolgus monkey, the lamina I projections were anterogradely labeled and adrenaline/NA-containing neurons were labeled immuno-cytochemically. The terminations of the lamina I ascending projections through the medulla and pons strongly overlapped with the locations of adrenaline/NA cells in the entire rostro-caudal VLM extent (A1 caudally, C1 rostrally): the NTS and the dorso-medial medullary RF (A2 caudally, C2 rostrally); the ventro-lateral pons (A5); the LC (A6); and the sub-coerulear region, the Kölliker-Fuse nucleus, and the medial and lateral PBN (A7). Close appositions between lamina I terminal varicosities and adrenaline/NA dendrites and somata occurred, particularly in the A1, A5 and the A7 cell groups on the contralateral side. The afferent input relayed by these lamina I projections could provide information about pain, temperature, and metabolic state. Nociceptive lamina I input to adrenaline/NA cell regions with projections back to the spinal cord could form a feedback loop for control of spinal sensory, autonomic and motor activity (Westlund and Craig 1996).

Brainstem NA neuron receive dissimilar afferents via various circuits to coordinate organismal responses to internal and environmental challenges, including pain. A1, A5, A6, and A7 receive nociceptive inputs from the lateral STTr (Dostrovsky 2000; Kuner and Kuner 2021) and show extensive descending projections to the spinal cord. In rats treated with formalin into the hindpaw 30 minutes after sub-cutaneous morphine injection, NA A5 and A7 cell groups contained significantly increased fos in response to intra-plantar formalin injection (an acute noxious input) (Bajic and Commons 2010).

Brainstem NA neuron project to local segmental (brainstem), cephalic (telencephalon and diencephalon), and caudal (spinal cord anterior, lateral, and DH) regions of the CNS, to the LC (A6), the primary source of NA in the brain, and to spinal pre-ganglionic neurons, which synapse onto post-ganglionic neurons, and thence to NA neurons located at the paravertebral sympathetic ganglia, supporting an anatomical hierarchy that regulates skeletal muscle innervation, neuromuscular transmission, and muscle trophism. Together with the parasympathetic nervous system, this NA neuron network accounts for the integrated organismal response to physiological or pathological challenges, including pain. Increased sympathetic activity is associated with better cognitive performance in individuals over 65 year leading to hypothesize interactions between the ANS and higher-level brain functions in neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders (Delbono et al. 2022)

A1 Group. The rat A1 NA cell group lies in the CVLM from upper cervical spinal cord levels to the level of the area postrema. In anesthetized rats, noxious thermal stimulation of the hindleg caused c-fos activation in the HYP PVN, in the adeno-hypophysis, and in other brain nuclei, including the cathecholaminergic cell groups of the caudal medulla. The NA A1 cells receive nociceptive inputs from the lateral STTr (Dostrovsky 2000) and relay it to the HYP PVN (Figure 2) and other structures (not shown for graphical reasons) (Kuner and Kuner 2021). Consequently, noxious stimulation caused corticosterone plasma release (Pan et al. 1999). Moreover, presumed efferent target sites include the NTS, RVM, dorsal PBN, Kölliker-Fuse nucleus, PAG, HYP dorso-medial nucleus (DMH) and lateral nucleus (lHYP), PVN, peri-fornical region, zona incerta, supraoptic nucleus (SON), BNST, and organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (Woulfe et al. 1990).

A5 Group. These cells receive a wide range of inputs. Importantly, these include connections from neurons of spinal lamina I (Dostrovsky 2000; Kuner and Kuner 2021), and from the ventral region of the medulla, more specifically from the CVLM. Both lamina I and the CVLM region play a predominant role in the integration of nociceptive responses. Connections have also been described from the trigeminal afferents from the nasal cavity (Rocha et al. 2024). The A5 group projects segmentally to A6 [locus coeruleus (LC), actually: caeruleus: celestial blue], with a possible role in cognition, and spinally, to target pre-ganglionic ACh neurons in the IML. The synapse between A5 pre-ganglionic and post-ganglionic NA neurons located at the paravertebral sympathetic ganglia support a role in skeletal muscle regulation. Skeletal muscle post-ganglionic sympathetic neuron projections have been related to neuromuscular organization, transmission, and skeletal muscle mass maintenance with development and ageing. The A5 group is supposed to contribute to the regulation of nociceptive messages at the spinal cord level (Kwiat et al. 1993).

A6 Group. The A6 cluster (LC) projects to the cerebellum, midbrain, globus pallidum, and various HYP areas. It also projects to the spinal DH to regulate pain perception and plays a role in sensory-motor behavior (Delbono et al. 2022).

A7 Group. A7 cell terminals are closely related to the ACh MNs in the VH and may influence motor output through NA binding to NA receptors expressed by the VH neurons (Delbono et al. 2022). Electrical lHYP stimulation produced anti-nociception, which was partially blocked by intra-thecal α-adrenergic antagonists. SP-immuno-reactive neurons in the lHYP project near the NA A7 cell group, which effects anti-nociception in the DH. However, while some A7 cells inhibit nociception through the action of α2-adrenoceptors in the spinal DH, other A7 cells increase nociception through the action of α1-adrenoceptors in the spinal DH (Holden and Naleway 2001).

5.10. Raphé Nuclei

The raphé nuclei are a collection of functionally and anatomically diverse cell groups that span the brainstem and contain the majority of the 5-TH-producing neurons in the CNS (Brodal 1981). From caudal to rostral, the raphé nuclei are, in the medulla oblongata: nucleus raphé obscurus, NRM, nucleus raphé pallidus; in the pons: nucleus raphé pontis, nucleus centralis inferior; in the midbrain: nucleus centralis superior, median raphé nucleus, DRN, caudal linear nucleus (Nieuwenhuys et al. 1978).

Inputs. Noxious peripheral stimuli cause activity changes in neurons of the RVM, which contains the NRM. For example, in anesthetized rats, 63 raphé-spinal units in NRM were classified into 5-HT and non-5-HT units. Except one, all units showed either excitatory (n = 39) or inhibitory (n = 23) responses to noxious stepwise heating of the tail with hot water at 52o C. The threshold temperature was around 44oC. The excitatory or inhibitory responses of raphé-spinal units correlated well with those elicited by noxious pinching, but did not correlate with the different transmitter populations (5-HT or non-5-HT) of the NRM units. In addition, in parallel to LC neurons, 5-HT neurons are activated by noxious peripheral stimuli in awake mice. Exposure to acute nociceptive stimulation consisting of a pinch and application of heat (55 °C) to the tail resulted in rapid and transient (<15 s) increases in the activity of RVM/NRM 5-HT neurons while control stimuli did not induce any changes (Moriya et al. 2019).

Many upper brain areas control the 5-HT neurons in the NRM. 5-HT neurons in the RVM receive direct excitatory inputs from the S1. Other regions control the 5-HT, including the orbital cortex, CC, medial and lateral POA, several areas of the HYP and the habenula (Hb). Both NRM and DReN are the targets of regulation via projections from several nuclei in the brainstem and the midbrain, including several catecholaminergic and cholinergic (ACh) cell groups (Cortes-Altamirano et al. 2018; Kuner and Kuner 2021).