1. Introduction

Aluminum (Al) is the most abundant metallic element in the earth’s crust. The exchangeable Al ions (primarily Al(OH)

2+, Al(OH)

2+, and Al(H

2O)

3+) released from silicates or oxides can promote exponential and cause Al toxicity when the soil pH value is below 5.5 [

1,

2]. Under Al toxicity stress, the first and most important symptom of crops is the inhibition of root elongation, ultimately affecting water and nutrient uptake [

3,

4,

5]. Unfortunately, most of the winter rapeseed areas in the Yangtze River basin of China, which are the one of thre

e major rapeseed producing areas in the world, grow in the acidic red soil areas of pH5.04~5.37. Additionally, approximately 40% of the world’s potential cultivable land exhibits a pH below 5.5 [

2,

5,

6,

7]. In these acidic conditions, exchangeable Al ions precipitate in the soil, creating Al toxicity stress that severely restricts the growth and yield of rapeseed [

5,

8]. As a result, Al toxicity has become a major limiting factor for crop productivity in acidic soils worldwide.

Plant tolerance to Al is a complex trait, which is controlled by multiple genes and pathways [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) proteins, encoded by a polygenic family and belonging to the glycoside hydrolase family GH16, play a crucial role in mediating cell wall remodeling [

13,

14]. Different members of the XTH family genes exhibit distinct functions in regulating Al toxicity tolerance. For instance,

XTH31 has been shown to participate in the regulation of Al tolerance in

Arabidopsis roots. Compared to the wild type,

xth31 mutants accumulate less Al in their roots and root cell walls, demonstrating enhanced Al tolerance [

15]. Similarly,

XTH17 has been identified to function analogously to

XTH31 and is also involved in the response to Al toxicity [

16,

17]. Overexpression of

AtXTH32 in

Arabidopsis significantly inhibits root growth and triggers typical markers of programmed cell death (PCD), whereas suppression of

xth32 results in largely opposite effects [

18]. In contrast,

ZmXTH has been found to enhance Al tolerance in transgenic

Arabidopsis plants by reducing Al accumulation in their roots and cell walls [

19].

In previous studies, our research group identified the gene

BnaA10g11500D through multi-omics analysis as potentially related to Al tolerance, and we discovered that

BnaA10g11500D may played an important role in the response of rapeseed to Al toxicity stress [

20]. As the homologous gene of

BnaA10g11500D,

AtXTH22 encodes the TCH4 enzyme, the substrate of the TCH4 enzyme is xyloglucan, which is closely related to cell wall stretching [

21].

BnaA10g11500D was named

BnaXTH22. Combined with the expression level and functional annotation of

BnaXTH22, overexpression genetic transformation was conducted in rapeseed for verification. The phenotype and physiological response of overexpressed lines (OEs) were studied, and transcriptome analysis was carried out. This study significantly expands our understanding of the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying the Al toxicity tolerance of the

BnaXTH22 overexpressing lines.

2. Result

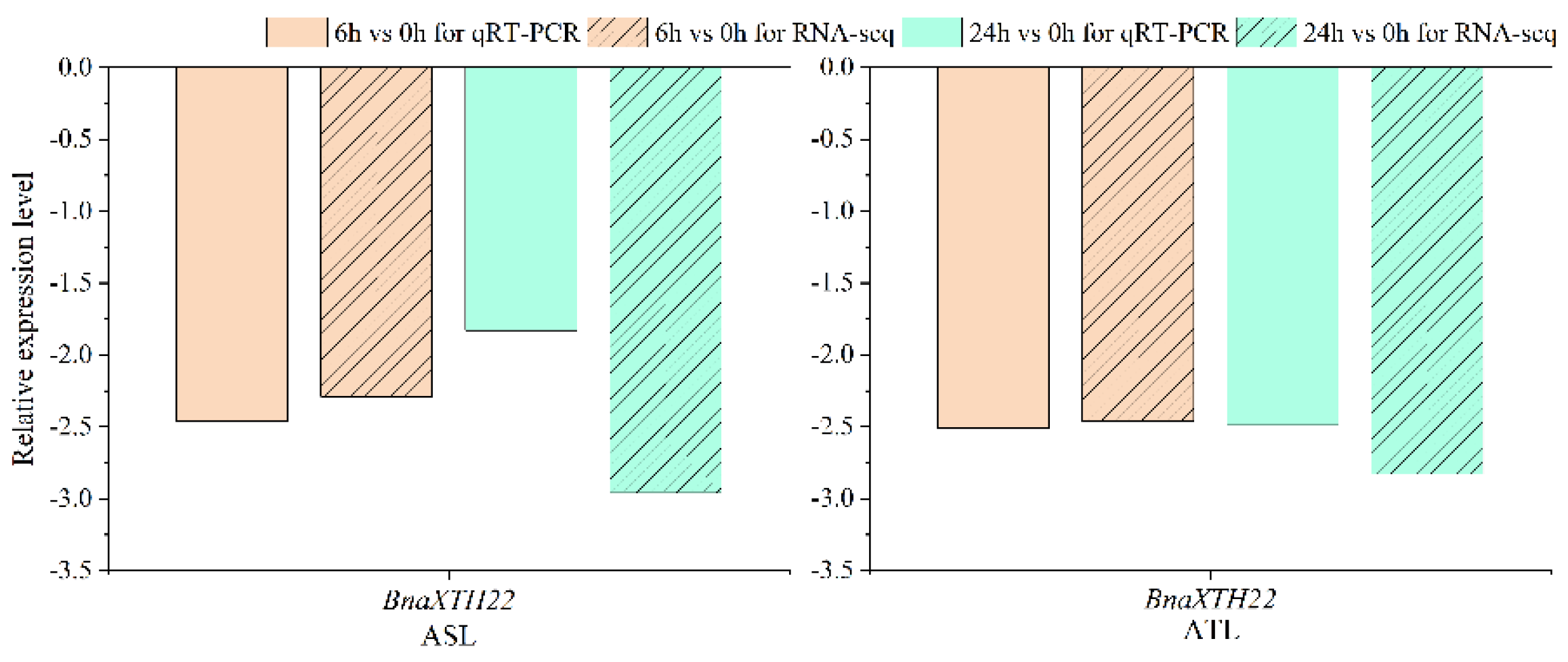

2.1. Analysis of the Expression Pattern of the BnaXTH22 Under Al Toxicity Stress

The gene

BnaXTH22 was differentially expressed at both 6 h vs. 0 h and 24 h vs. 0 h in both R178 (aluminum tolerant line, ATL) and S169 (aluminum sensitive line, ASL). To validate its expression under Al toxicity stress, we performed qRT-PCR analysis. The results demonstrated expression patterns consistent with the RNA-seq data, confirming the reliability of the selected differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (

Figure 1). These findings indicated that

BnaXTH22 likely played an important functional role in rapeseed response to Al toxicity stress.

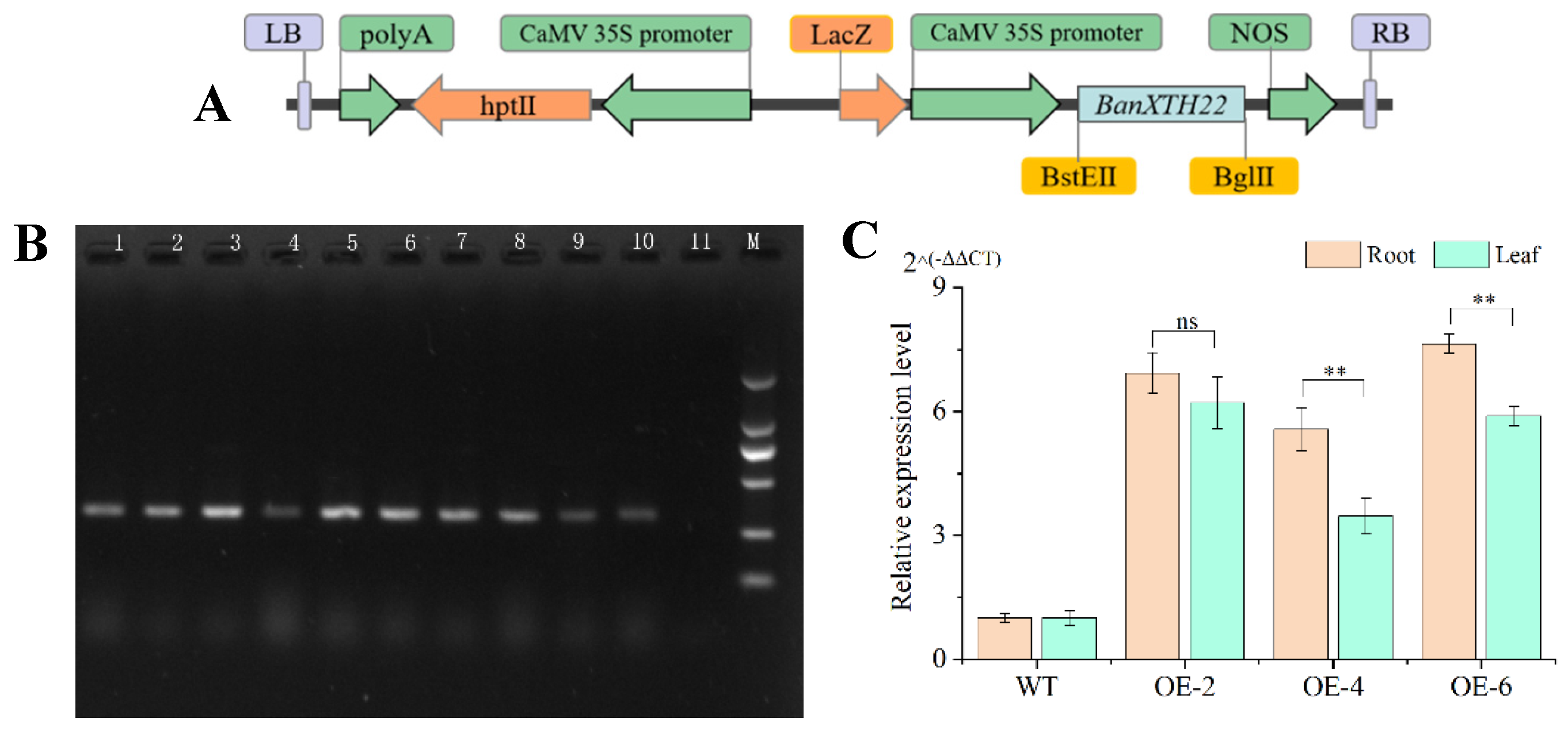

2.2. Generation of Transgenic Plants and Molecular Identification

The recombinant plasmid pCAMBIA3301-BnaXTH22 (

Figure 2A) was successfully constructed and transformed into wild-type rapeseed (Westar, non-transgenic control, WT). Eight independent transgenic lines were established, with successful transformation confirmed through T

0 generation screening (

Figure 2B). Three randomly selected T

3 transgenic lines (OE-2, OE-4, and OE-6) were subjected to

BnaXTH22 expression analysis. Quantitative results demonstrated that these overexpression lines (OEs) exhibited 2.47- to 6.64-fold higher

BnaXTH22 expression levels in both leaves and roots compared to WT plants (

Figure 2C), confirming successful transgene overexpression. These three lines were consequently chosen for further experimental investigations.

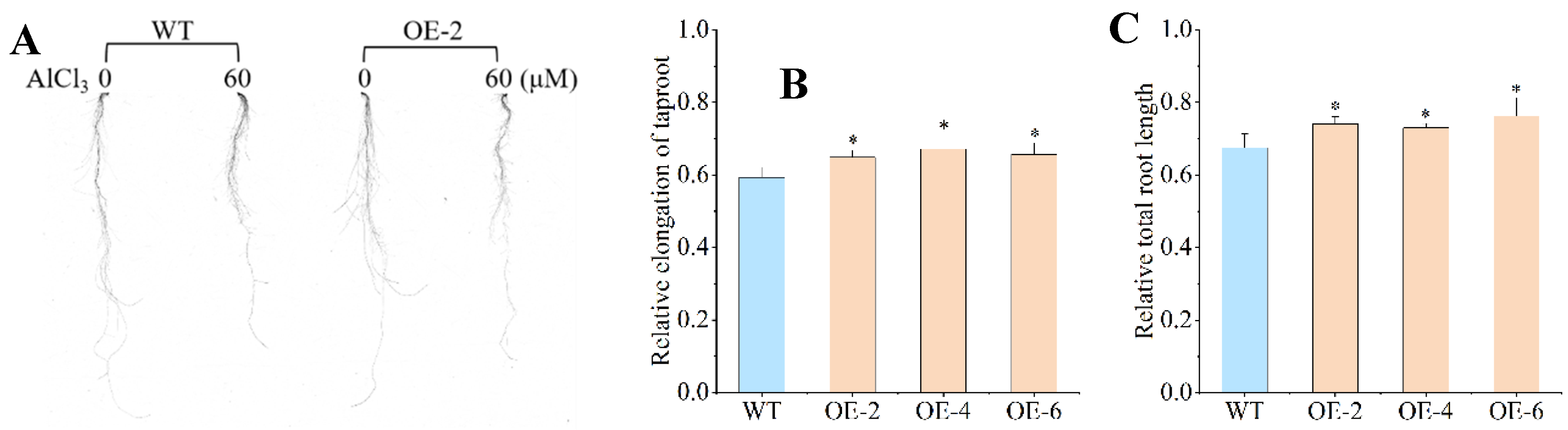

2.3. Phenotype Characterization of Overexpressing BnaXTH22

To assess phenotypic and physiological responses to 60 μM AlCl₃ treatment, we analyzed OE-2, OE-4, OE-6, and WT plants. The relative elongation of taproots (RET) in OE lines (0.649, 0.672, and 0.657 for OE-2, OE-4, and OE-6, respectively) showed significant increases of 9.44%, 13.32%, and 10.79% compared to WT (0.593) (

Figure 3A,B). While no significant differences existed among OE lines, all demonstrated markedly greater RET than WT. Similarly, relative total root length (RTRL) measurements revealed values of 0.741, 0.730, and 0.762 for OE-2, OE-4, and OE-6, respectively, corresponding to 9.78%, 8.15%, and 12.89% increases over WT (0.675) (

Figure 3C). Although RTRL did not differ significantly among the OE lines, all transgenic plants exhibited significantly greater values than WT, mirroring the RET pattern. Notably, RTRL exceeded RET in both WT and OE plants, suggesting that Al toxicity exerts a more pronounced inhibitory effect on taproot growth than on lateral roots.

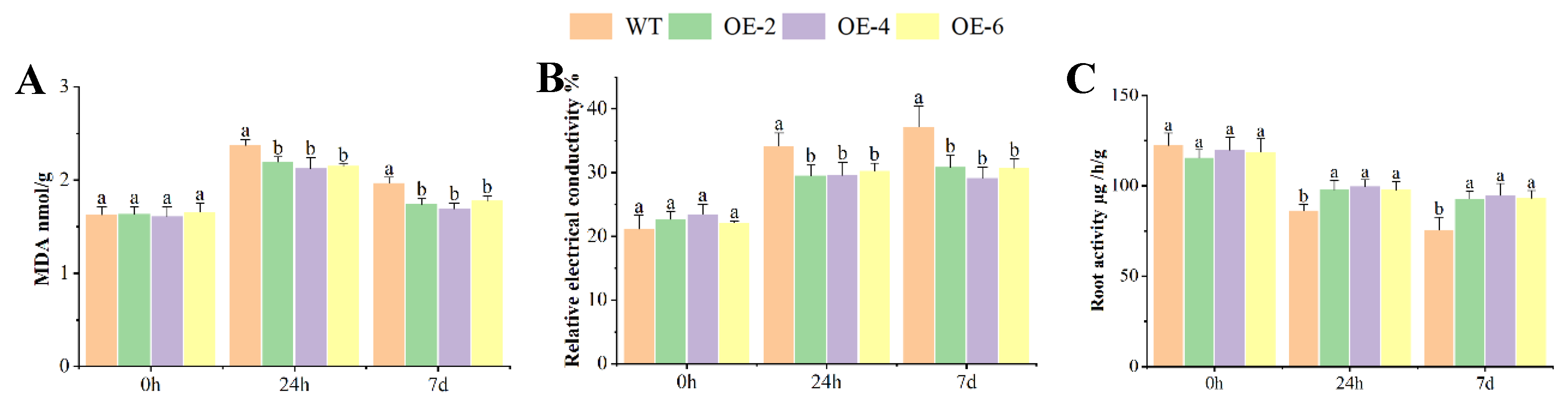

2.4. MDA, REC, and RA of OEs Response to Al Toxicity Stress

Under control conditions (0 h treatment), no significant differences were observed in any physiological indices between overexpression lines (OEs) and wild-type (WT) plants. However, following exposure to 60 μM AlCl₃ stress, while the OEs showed no significant variation among themselves, they collectively demonstrated markedly enhanced stress tolerance compared to WT, as evidenced by all physiological parameters measured. (

Figure 4).

The content of MDA increased when the plants were exposed to Al toxicity stress, and there was a significant difference in the content of MDA between WT and OEs after 7 days treatment (

Figure 4A). The relative electrical conductivity (REC) increased when the plants exposed to Al toxicity stress. The OEs exhibited lower levels of stress-induced ion leakage compared to the plants of WT plants and there was significant difference in the relative electrical conductivity between WT and OEs after 7 days treatment (

Figure 4B). The root activity (RA) was opposite to the content of MDA and the relative electrical conductivity, the root activity reduced when the plants were exposed to Al toxicity stress. The OEs exhibited higher levels of root activity compared to the plants of WT plants between WT and OEs after 24 h and 7 days treatment (

Figure 4C).

2.5. Transcriptome Analysis of Overexpressing BnaXTH22

The RET of OE-2 and WT was 0.621±0.034 and 0.533±0.042 under 60 μM AlCl

3 for 24 h. The RET of OE-2 significantly increased by 15.23% compared to WT. To obtain greater insight into the underlying molecular mechanism modulating Al tolerance and stress-responsive genes by

BnaXTH22 overexpression, RNA-seq was conducted with OE-2 and WT as experimental materials. More than 525.2 million clean reads from 12 libraries of the two genotypes were generated and mapped to the reference genome. (

Table 1).

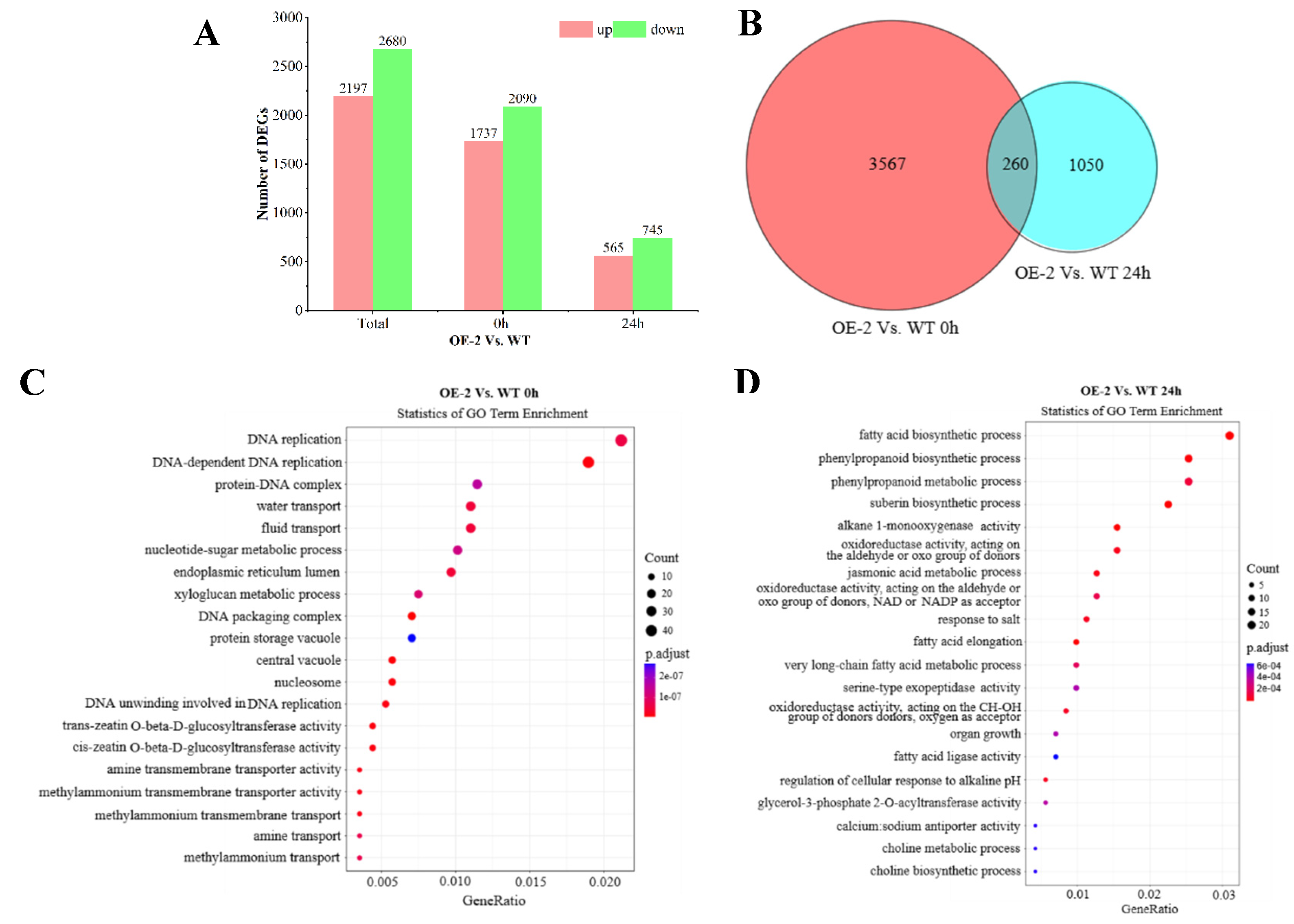

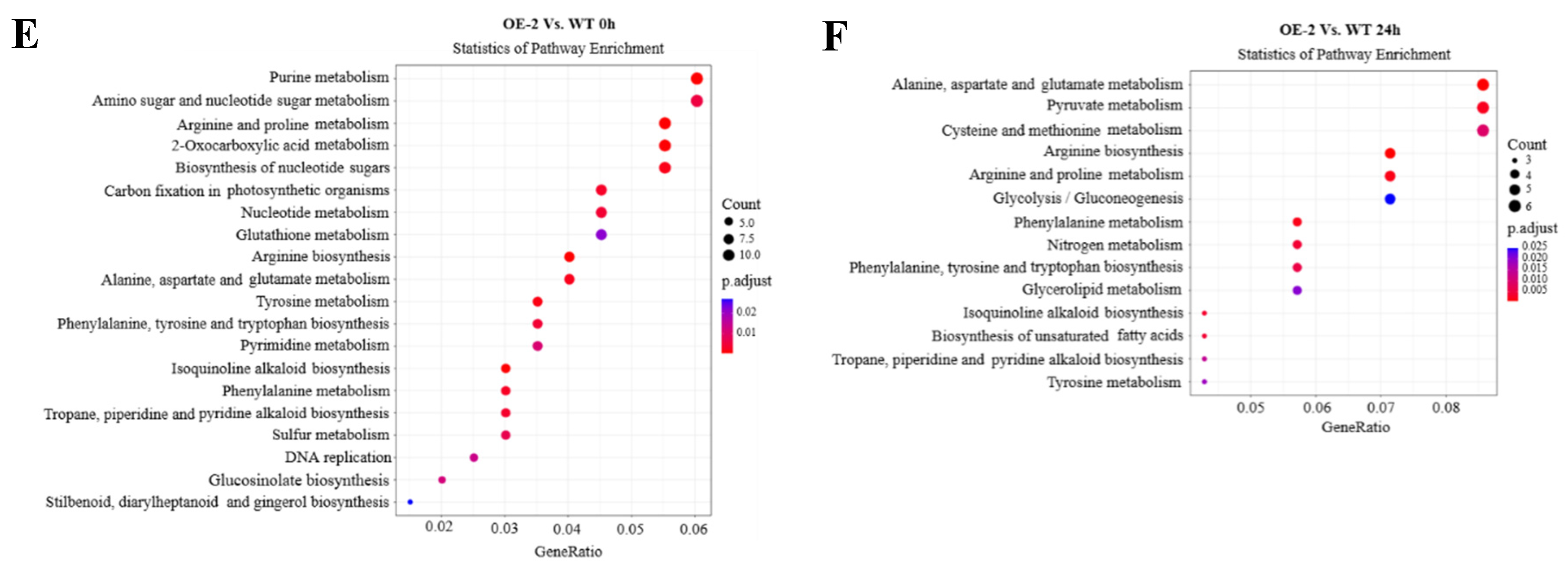

2.6. Al Toxicity Response Related Genes with BnaXTH22 Overexpression

To determine which genes correlated with

BnaXTH22 overexpression, the DEGs between the OE-2 and WT for 0 h and 24 h were identified. After screening by |log2 fold change| > 1.0 and p value < 0.05, a total of 4877 DEGs between the OE-2 and WT, of which 2197 DEGs were up regulated and 2680 DEGs were down regulated. In 0 h, a total of 3827 DEGs between the OE-2 and WT, of which 1737 DEGs showed up-regulation and 2090 DEGs showed down-regulation. Whereas 565 DEGs showed up-regulation and 745 DEGs showed down-regulation at 24 h. (

Figure 5A). Interestingly, 260 common DEGs were identified between the OE-2 and WT at both 0 h and 24 h (

Figure 5B).

The GO enrichment analysis of 3827 DEGs with WT and OE-2 at 0 h showed that these DEGs participated in a variety of biological processes, including DNA-dependent DNA replication, DNA replication, water transport, liquid transport, etc. Under the condition of Al toxicity treatment for 24 h, it mainly participated in the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic process, fatty acid biosynthetic process, suberin biosynthetic process, phenylpropanoid biosynthetic process, phenylpropanoid metabolic process and other adverse biological processes. (

Figure 5C,D)

The pathway enrichment analysis of WT and OE-2 at 0 h showed that these DEGs were significantly enriched in arginine and proline metabolism, arginine biosynthesis and Purine metabolism. However, under the condition of Al poisoning for 24 h, alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, arginine biosynthesis, arginine and proline metabolism, pyruvate metabolism were significantly enriched. (

Figure 5E,F)

3. Discussion

Plant cell walls are composed of various molecules and have many important physiological functions. One of the factors responsible for the plasticity of the cell wall is XTH family, which cleaves and reconnects xyloglucan molecules. XTHs are not necessary for cell wall loosening during plant cell expansion, but play a critical role under specific biological or abiotic stresses [

22]. Compared with the wild type,

xth31 mutants accumulate less Al in roots and root cell walls, and show stronger Al tolerance in

Arabidopsis [

15].

XTH17 and

AhXTH32 were found to be similar to

XTH31 and also involved in Al toxicity response [

16,

17,

18]. Whereas

ZmXTH could confer the Al tolerance of transgenic

Arabidopsis plants by reducing the Al accumulation in their roots and cell walls [

19]. Combined with the expression level and functional annotation of

BnaXTH22, overexpression genetic transformation was conducted in rapeseed for verification.

Root growth and elongation are the synergistic result of root cell division and cell elongation. The earliest morphological changes of crops induced by Al are root and shoot growth inhibition. Root cap cells, meristem cells, tanycytes and root hair cells were the most severely affected parts [

23,

24]. Al interferes with cell division in root tips and lateral roots by inhibiting the production and transport of cytokinin [

23,

25]. Al toxicity stress affects the transport of auxin between cells, thus inhibiting root growth [

26,

27,

28]. In crops, including rape, the Al tolerance of crops is often expressed or identified by root-related traits such as taproot length and taproot relative productivity at the seedling stage, and based on this, resource identification, gene mining and functional verification are carried out [

29,

30,

31]. In this study, it was found that the RTE of rape seedlings treated with Al toxicity was significantly reduced, which was consistent with the conclusion of the previous study that the RTE of rape was gradually reduced under Al toxicity stress [

32], and a similar pattern was also found in

Arabidopsis, rice, lettuce and other crops [

33,

34,

35]. However, in this study, RTE and RTRL of OEs treated with 60µM AlCl

3 were significantly higher than those of WT, indicating that the resistance of OEs to Al toxicity was significantly better than that of WT, indicating that overexpression of

BnaXTH22 improved the Al toxicity resistance of rape.

MDA is the end-product of membrane lipid peroxidation and can be used to characterize the degree of lipid peroxidation of plant cell membrane. Relative electrical conductivity is a basic index to reflect the permeability of plant cell membrane, and root activity level is an important index to reflect the root growth status. Under stress such as Al toxicity, MDA content increases, relative conductivity increases, and root activity decreases [

35,

36,

37,

38]. In this study, the MDA content of WT and OEs increased, the relative conductivity increased, and the root activity decreased under Al toxicity stress. Compared with WT, MDA content after 7 days of OEs treatment was lower, and the increase of MDA content was smaller than that after 0 h treatment. The REC of OEs after7 days increased less than that of 0 h, and the REC of OEs was lower or significantly lower than that of WT. The root activity of WT was lower or significantly lower than that of OEs after 7 days of treatment. In conclusion, the overexpression of

BnaXTH22 increased the resistance of rapeseed to Al toxicity.

RNA-seq was used to identify differentially expressed genes in roots and leaves of rapeseed seedlings under Al toxicity and drought stress, and the molecular functions and metabolic pathways of related differentially expressed genes were clarified through GO and KEGG enrichment analysis [

39,

40,

41]. The overexpressed transcriptome can be used to analyze the regulatory mechanism of target gene overexpression under the same genetic background. Transcriptome analysis of overexpression of

PpSAUR73 in

Arabidopsis thaliana was performed to compare differentially expressed genes between overexpressed plants and wild-type plants, and significant enrichment analysis of GO function and KEGG pathway was performed to determine that

PpSAUR73 can regulate growth of

Arabidopsis thaliana and participate in various hormone signal transduction [

42]. Transcriptome sequencing was performed on plants overexpressing D

gLsL in different treatments, and the enrichment analysis of GO and KEGG pathways confirmed previous studies on axillary bud germination and growth, revealing the important role of genes involved in plant hormone biosynthesis and signal transduction [

43]. In this study, GO enrichment analysis showed that the regulation of abiotic stress such as plant Al toxicity involved multiple functional groups. One of them affects plant type secondary cell wall biosynthesis [

44]. Some NAC and MYB transcription factors are involved in the biosynthesis of lignin, cellulose and xylan in cell wall [

45,

46,

47,

48], and irregular xylem proteins are also involved in xylan biosynthesis [

49]. Arabinogalactan, a bunch-like protein, has been shown to play an important role in plant development and environmental adaptation [

50]. In this study, it was found that DEGs are mainly involved in stress biological processes such as phenylpropanoid metabolism, fatty acid biosynthesis, lignin biosynthesis and phenylC biosynthesis under Al toxicity treatment, which was conducive to enhancing Al toxicity tolerance of plants overexpressing

BnaXTH22.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Validation of Gene by qRT-PCR

ATL and ASL were used as materials for cultivation, treatment and qRT-PCR by referring to our previous studies [

20]. Here we choose the candidate gene

BnaXTH22,which were simultaneously detected between 6 h vs 0 h and 24 h vs 0 h in ATL and ASL. The primer sequences used for qRT-PCR can be found in

Table 2. The relative expression levels were determined using the 2

-ΔΔCt method based on the normalization to the reference genes

ACT7. Three technical replicates were performed for each DEGs and reference genes.

4.2. Generation of Transgenic Westar Plants

Based on the total RNA of root after 24 h of ATL Al stress, Reverse transcription into cDNA using reverse transcription kit (Beijing Baori Medical Technology Co., LTD). Using the cDNA as a template, BnaXTH22 CDS of 645bp was obtained by PCR amplification with specific forward primers and reverse primers. The nucleotide sequence of the forward primer is 5’-ATGCAGATGAAACTCGTCC-3’. The nucleotide sequence of the reverse primer is 5’-CTATGCAGCAAAGCACTCTT-3’. And then BnaXTH22 CDS linked to the overexpression vector pCAMBIA1301. Genetic transformation into wild-type rape Westar by Wuhan Biorun Biosciences Co., LTD. After harvesting positive OEs of T0 generation, positive plants of T1 generation and T2 generation were obtained by continuous self-fertilization. The positive test plants of PCR product 683bp were selected with a forward primer 5’-TGACGTAAGGGATGACGCAC-3’ and reverse primer 5’-TGGGAGTTCCATCGACTGTG-3’. The cDNA of transgenic rapeseed plants and wild rapeseed plants were used as templates for qRT-PCR verification. The internal reference gene is ACT7. Finally, the overexpressed positive seeds of the T3 generation were used for further experiments.

4.3. Morphological and Physiological Parameter Under Al Stress

Phenotypic identification and physiological response processing time was 7 days by 60 μmol·L

-1 AlCl

3. The hydroponic method and index calculation is the same as our previous studies [

20]. Physiological parameters of WT and OEs rapeseed root were measured, including MDA content, relative electrical conductivity and root activity. These physiological indicators are carried out according to the kit instructions (Suzhou Grace Biotechnology Co., LTD.)

4.4. RNA-Seq Under Al Tolerance and Data Analysis

To obtain greater insight into the underlying molecular mechanism modulating Al tolerance and stress-responsive genes by

BnaXTH22 overexpression, the OE-2 and WT were treated with 60µmol·L

-1 AlCl

3 for 0 h and 24 h, respectively. Then the roots quickly were frozen in liquid nitrogen. To detect the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in different treatments by RNA-seq. Sequencing service was provided by Wekemo Tech Group Co., Ltd. Shenzhen China. The data and analysis methods were obtained by referring to our previous studies [

20].. The RET of the OE and WT was measured at 24 h.

5. Conclusions

Compared to the wild type (WT), plants overexpressing BnaXTH22 exhibited significantly greater relative elongation of taproots and total root length, reduced MDA accumulation and relative electrical conductivity, markedly higher root activity, and enhanced tolerance to Al toxicity. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that BnaXTH22 overexpression upregulates stress-related biological processes, including phenylpropanoid metabolism, fatty acid biosynthesis, lignin biosynthesis, and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, thereby improving Al toxicity resistance.

Author Contributions

W.Z. and X.X. designed the research plan; P.Y., D.H., M.C., L.Y., Y.L., T.H., W.X., Y.C., X.L., C. W., W.Z. and X.X. performed the research work; P.Y., X.X., D.H. and W.Z. analyzed the data; P.Y., and X.X. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China project (32160463, 32260458), the Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (20224BAB205021), the Key Laboratory of Arable Land Improvement and Quality Improvement of Jiangxi Province (2024SSY04223), and the Jiangxi Training Project of high-level and high-skill leading talents (2023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wuhan Biorun Biosciences Co., LTD. for genetic transformation and Wekemo Tech Group Co., Ltd. Shenzhen Chain for Sequencing service in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shetty, R.; Vidya, C.S.; Prakash, N.B.; Lux, A.; Vaculík, M. Aluminum toxicity in plants and its possible mitigation in acid soils by biochar: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 765, 142744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochian, L.V.; Piñeros, M.A.; Liu, J.; Magalhaes, J.V. Plant Adaptation to Acid Soils: The Molecular Basis for Crop Aluminum Resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 571–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejia-Alvarado, F.S.; Botero-Rozo, D.; Araque, L.; Bayona, C.; Herrera-Corzo, M.; Montoya, C.; Ayala-Díaz, I.; Romero, H.M. Molecular network of the oil palm root response to aluminum stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, R.; Shu, K.; Lv, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, C. Aluminum stress signaling, response, and adaptive mechanisms in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17, 2057060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou H, Yu P, Wu L, Han D, Wu Y, Zheng W, Zhou Q, Xiao X. Combined BSA-Seq and RNA-Seq Analysis to Identify Candidate Genes Associated with Aluminum Toxicity in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25(20): 11190. [CrossRef]

- von Uexküll, H.; Mutert, E. Global extent, development and economic impact of acid soils. Plant Soil. 1995, 171, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.F.; Shen, R.F. Towards sustainable use of acidic soils: Deciphering aluminum-resistant mechanisms in plants. Fundam. Res. 2023, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao HH,Ye S,Wang Q,Wang LY,Wang RL,Chen LY,Tang ZL,Li JN,Zhou QY,Cui C. Screening and comprehensive evaluation of aluminum-toxicity tolerance during seed germination in Brassca napus. Acta Agronomica Sinica. 2019, 45(9): 1416-1430. [CrossRef]

- Du H, Raman H, Kawasaki A, Perera G, Diffey S, Snowdon R, Raman R, Ryan PR. A genome-wide association study (GWAS) identifies multiple loci linked with the natural variation for Al3+ resistance in Brassica napus. Funct Plant Biol. 2022, 49(10):845-860. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay N, Kar D, Deepak Mahajan B, Nanda S, Rahiman R, Panchakshari N, Bhagavatula L, Datta S. The multitasking abilities of MATE transporters in plants. J Exp Bot. 2019, 70(18):4643-4656. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Shi H, Xu L, Xing M, Wu X, Bai Y, Niu M, Gao J, Zhou Q, Cui C. Combining transcriptomics and metabolomics to identify key response genes for aluminum toxicity in the root system of Brassica napus L. seedlings. Theor Appl Genet. 2023, 136(8):169. [CrossRef]

- Qin Z, Chen S, Feng J, Chen H, Qi X, Wang H, Deng Y. Identification of aluminum-activated malate transporters (ALMT) family genes in hydrangea and functional characterization of HmALMT5/9/11 under aluminum stress. PeerJ. 2022, 10:e13620. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Li Y, Lu C, Tang Y, Jiang X, Gai Y. Isolation and characterization of Populus xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase (XTH) involved in osmotic stress responses. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020, 155:1277-1287. [CrossRef]

- Van Sandt V S T, Suslov D, Verbelen J P, and Vissenberg K., Xyloglucan transglucosylase activity loosens a plant cell wall[J]. Annals of Botany. 2007, 100(7): 1467-1473. [CrossRef]

- Zhu XF, Shi YZ, Lei GJ, Fry SC, Zhang BC, Zhou YH, Braam J, Jiang T, Xu XY, Mao CZ, Pan YJ, Yang JL, Wu P, Zheng SJ. XTH31, encoding an in vitro XEH/XET-active enzyme, regulates aluminum sensitivity by modulating in vivo XET action, cell wall xyloglucan content, and aluminum binding capacity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012, 24(11):4731-47. [CrossRef]

- Bi H, Liu Z, Liu S, Qiao W, Zhang K, Zhao M, Wang D. Genome-wide analysis of wheat xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) gene family revealed TaXTH17 involved in abiotic stress responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24(1):640. [CrossRef]

- Zhu XF, Wan JX, Sun Y, Shi YZ, Braam J, Li GX, Zheng SJ. Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylase-Hydrolase17 Interacts with Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylase-Hydrolase31 to Confer Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylase Action and Affect Aluminum Sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165(4):1566-1574. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.243790. 16.

- Luo S, Pan C, Liu S, Liao G, Li A, Wang Y, Wang A, Xiao D, He LF, Zhan J. Identification and functional characterization of the xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 32 (AhXTH32) in peanut during aluminum-induced programmed cell death. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023, 194:161-168. [CrossRef]

- Du H, Hu X, Yang W, Hu W, Yan W, Li Y, He W, Cao M, Zhang X, Luo B, Gao S, Zhang S. ZmXTH, a xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase gene of maize, conferred aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis. J Plant Physiol. 2021, 266:153520. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, Xiao X, Asjad A, Han D, Zheng W, Xiao G, Huang Y, Zhou Q. Integration of GWAS and transcriptome analyses to identify SNPs and candidate genes for aluminum tolerance in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22(1):130. [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan R, Chinnappa CC, Staal M, Elzenga JT, Yokoyama R, Nishitani K, Voesenek LA, Pierik R. Light quality-mediated petiole elongation in Arabidopsis during shade avoidance involves cell wall modification by xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolases. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154(2):978-90. [CrossRef]

- Ishida K, Yokoyama R. Reconsidering the function of the xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase family. J Plant Res. 2022, 135(2):145-156. [CrossRef]

- Ofoe R, Thomas RH, Asiedu SK, Wang-Pruski G, Fofana B, Abbey L. Aluminum in plant: Benefits, toxicity and tolerance mechanisms. Front Plant Sci. 2023, 13:1085998. [CrossRef]

- Dong D, Deng Q, Zhang J, Jia C, Gao M, Wang Y, Zhang L, Zhang N, Guo YD. Transcription factor SlSTOP1 regulates Small Auxin-Up RNA Genes for tomato root elongation under aluminum stress. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196(4):2654-2668. [CrossRef]

- Jiang F, Lyi SM, Sun T, Li L, Wang T, Liu J. Involvement of cytokinins in STOP1-mediated resistance to proton toxicity. Stress Biol. 2022, 2(1):17. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Liu G, Geng X, He C, Quan T, Hayashi KI, De Smet I, Robert HS, Ding Z, Yang ZB. Local regulation of auxin transport in root-apex transition zone mediates aluminium-induced Arabidopsis root-growth inhibition. Plant J. 2021, 108(1):55-66. [CrossRef]

- Tao L, Xiao X, Huang Q, Zhu H, Feng Y, Li Y, Li X, Guo Z, Liu J, Wu F, Pirayesh N, Mahmud S, Shen RF, Shabala S, Baluška F, Shi L, Yu M. Boron supply restores aluminum-blocked auxin transport by the modulation of PIN2 trafficking in the root apical transition zone. Plant J. 2023, 114(1):176-192. [CrossRef]

- Jesus DDSD , Martins FM ,André Dias de Azevedo Neto. Structural changes in leaves and roots are anatomical markers of aluminum sensitivity in sunflower. Pesquisa Agropecuaria Tropical, 2016, 46(4):383-390. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W,Huang YD, Zang PC, Xu FS, Wang C, Ding GD. Screening extreme varieties with aluminum tolerance and analyzing physiological mechanisms of aluminum tolerance in Brassica napus. Journal of Huazhong Agricultural University, 2023, 42(6): 154-163. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Xu J, Guo S, Yuan X, Zhao S, Tian H, Dai S, Kong X, Ding Z. AtHB7/12 Regulate Root Growth in Response to Aluminum Stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21(11):4080. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Dong J, Li R, Zhao X, Zhu Z, Zhang F, Zhou K, Lin X. Sodium hydrosulfide alleviates aluminum toxicity in Brassica napus through maintaining H2S, ROS homeostasis and enhancing aluminum exclusion. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 858(Pt 3):160073. [CrossRef]

- HAN DP, LIU XY, WANG XY, LUO S, FU DH, ZHOU QH. Effects of aluminum stress on morphology parameters of roots and physiological indexes in Brassica napus L. Journal of Nuclear Agricultural Sciences, 2019, 33(9): 1824-1832. [CrossRef]

- Liu YT, Shi QH, Cao HJ, Ma QB, Nian H, Zhang XX. Heterologous Expression of a Glycine soja C2H2 Zinc Finger Gene Improves Aluminum Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21(8):2754. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro C, de Marcos Lapaz A, de Freitas-Silva L, Ribeiro KVG, Yoshida CHP, Dal-Bianco M, Cambraia J. Aluminum promotes changes in rice root structure and ascorbate and glutathione metabolism. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2022, 28(11-12):2085-2098. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar MVM, Mattos JPO, Wertonge GS, Rosa FCR, Lovato LR, Valsoler DV, Azevedo TD, Nicoloso FT, Tabaldi LA. Silicon as an attenuator of the toxic effects of aluminum in Schinus terebinthifolius plants. Braz J Biol. 2023, 83:e271301. [CrossRef]

- Yan L, Li S, Cheng J, Zhang Y, Jiang C. Boron-mediated lignin metabolism in response to aluminum toxicity in citrus (Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf.) root. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2022, 185:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Lu P, Magwanga RO, Kirungu JN, Hu Y, Dong Q, Cai X, Zhou Z, Wang X, Zhang Z, Hou Y, Wang K, Liu F. Overexpression of Cotton a DTX/MATE Gene Enhances Drought, Salt, and Cold Stress Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2019, 10:299. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Mo X, Sun L, Gao L, Su L, An Y, Zhou P. MsDjB4, a HSP40 chaperone in Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), improves Alfalfa hairy root tolerance to aluminum stress. Plants (Basel). 2023, 12(15):2808. [CrossRef]

- Awasthi JP, Kusunoki K, Saha B, Kobayashi Y, Koyama H, Panda SK. Comparative RNA-Seq analysis of the root revealed transcriptional regulation system for aluminum tolerance in contrasting indica rice of North East India. Protoplasma. 2021, 258(3):517-528. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Cui J, Cai Y, Yang S, Liu J, Wang W, Gai J, Hu Z, Li Y. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Two Contrasting Soybean Varieties in Response to Aluminum Toxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21(12):4316. [CrossRef]

- Brhane H, Haileselassie T, Tesfaye K, Ortiz R, Hammenhag C, Abreha KB, Vetukuri RR, Geleta M. Finger millet RNA-seq reveals differential gene expression associated with tolerance to aluminum toxicity and provides novel genomic resources. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13:1068383. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Cao HB, Zhang XY, Zhai HH, Li XM, Peng JW, Tian Y, Chen HJ. Functional Identification of Peach GenePpSAUR73[J]. Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 2023, 56(20): 4072-4086. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Ling Q, Li X, Ma Q, Tang S, Yuanzhi P, Liu QL, Jia Y, Yong X, Jiang B. Transcriptome analysis during axillary bud growth in chrysanthemum (chrysanthemum×morifolium). PeerJ. 2023, 11:e16436. [CrossRef]

- Buerstmayr M, Wagner C, Nosenko T, Omony J, Steiner B, Nussbaumer T, Mayer KFX, Buerstmayr H. Fusarium head blight resistance in European winter wheat: insights from genome-wide transcriptome analysis. BMC Genomics. 2021, 22(1):470. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Yu H, Rao X, Li L, Dixon RA. Abscisic acid regulates secondary cell-wall formation and lignin deposition in Arabidopsis thaliana through phosphorylation of NST1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021, 118(5):e2010911118. [CrossRef]

- Lou HQ, Fan W, Jin FJ, et al. Lou HQ, Fan W, Jin JF, Xu JM, Chen WW, Yang JL, Zheng SJ. A NAC-type transcription factor confers aluminium resistance by regulating cell wall-associated receptor kinase 1 and cell wall pectin. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43(2):463-478. [CrossRef]

- Xiao R, Zhang C, Guo X, Li H, Lu H. MYB Transcription Factors and Its Regulation in Secondary Cell Wall Formation and Lignin Biosynthesis during Xylem Development. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(7):3560. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Tao Y, Huang J, Liu YS, Yang XZ, Jing HK, Shen RF, Zhu XF. The MYB transcription factor MYB103 acts upstream of TRICHOME BIREFRINGENCE-LIKE27 in regulating aluminum sensitivity by modulating the O-acetylation level of cell wall xyloglucan in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2022, 111(2):529-545. [CrossRef]

- Brown D, Wightman R, Zhang Z, Gomez LD, Atanassov I, Bukowski JP, Tryfona T, McQueen-Mason SJ, Dupree P, Turner S. Arabidopsis genes IRREGULAR XYLEM (IRX15) and IRX15L encode DUF579-containing proteins that are essential for normal xylan deposition in the secondary cell wall. Plant J. 2011, 66(3):401-13. [CrossRef]

- He J, Zhao H, Cheng Z, Ke Y, Liu J, Ma H. Evolution analysis of the fasciclin-like arabinogalactan proteins in plants shows variable fasciclin-AGP domain constitutions. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20(8):1945. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).