Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

09 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

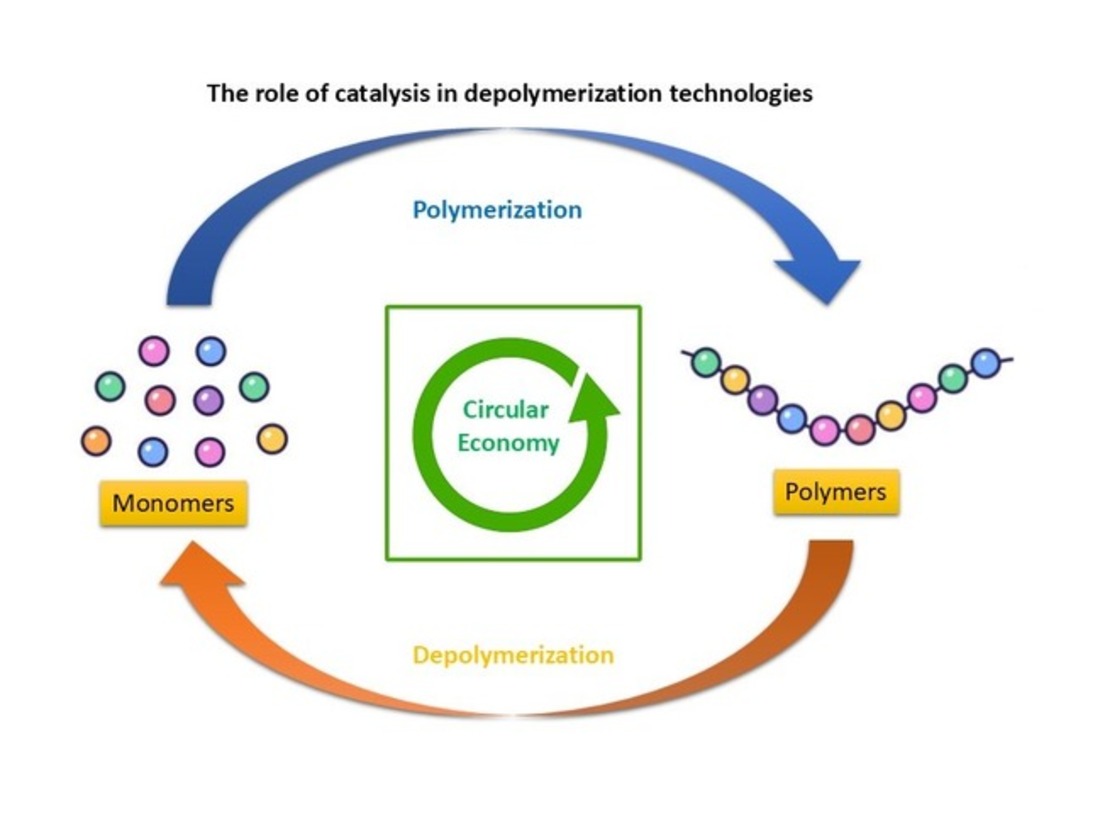

1. Introduction

2. Catalytic Depolymerization of Cellulose

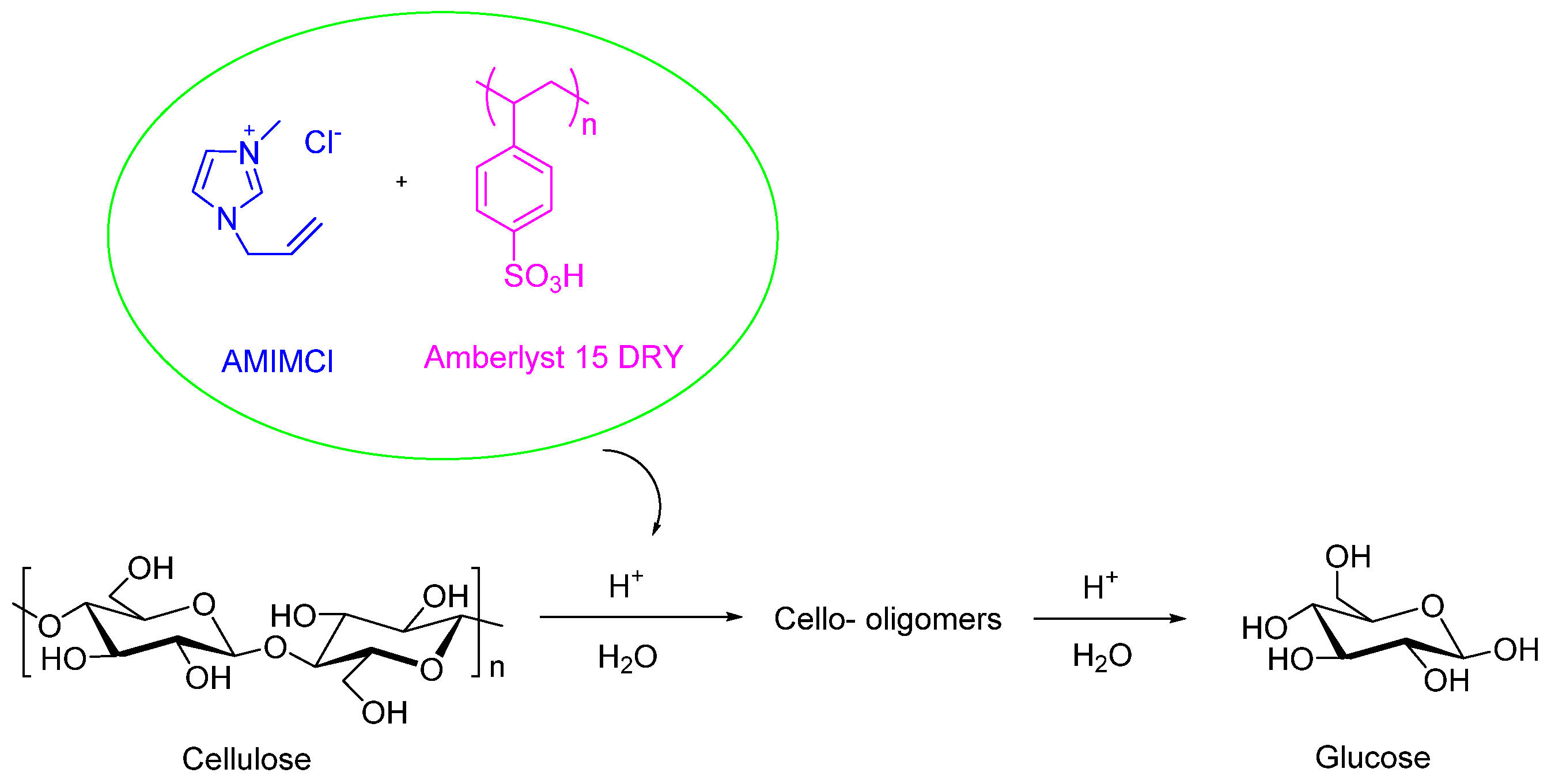

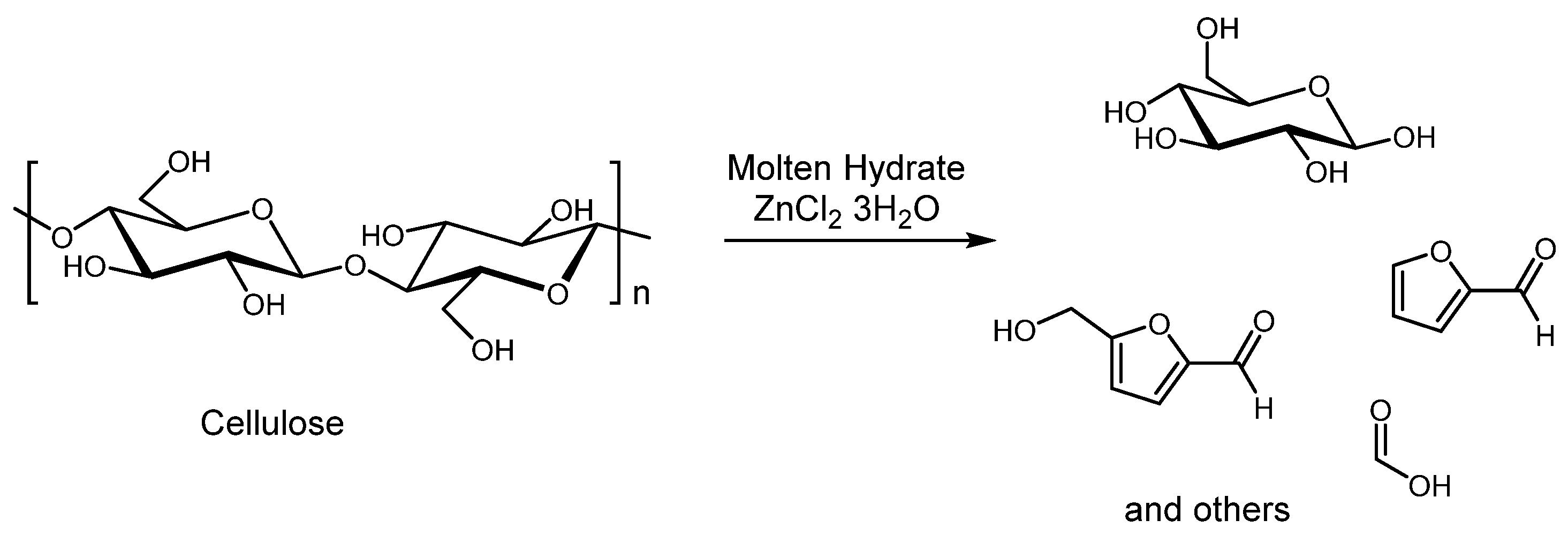

2.1. Solid Acid Catalyst Depolymerization of Cellulose

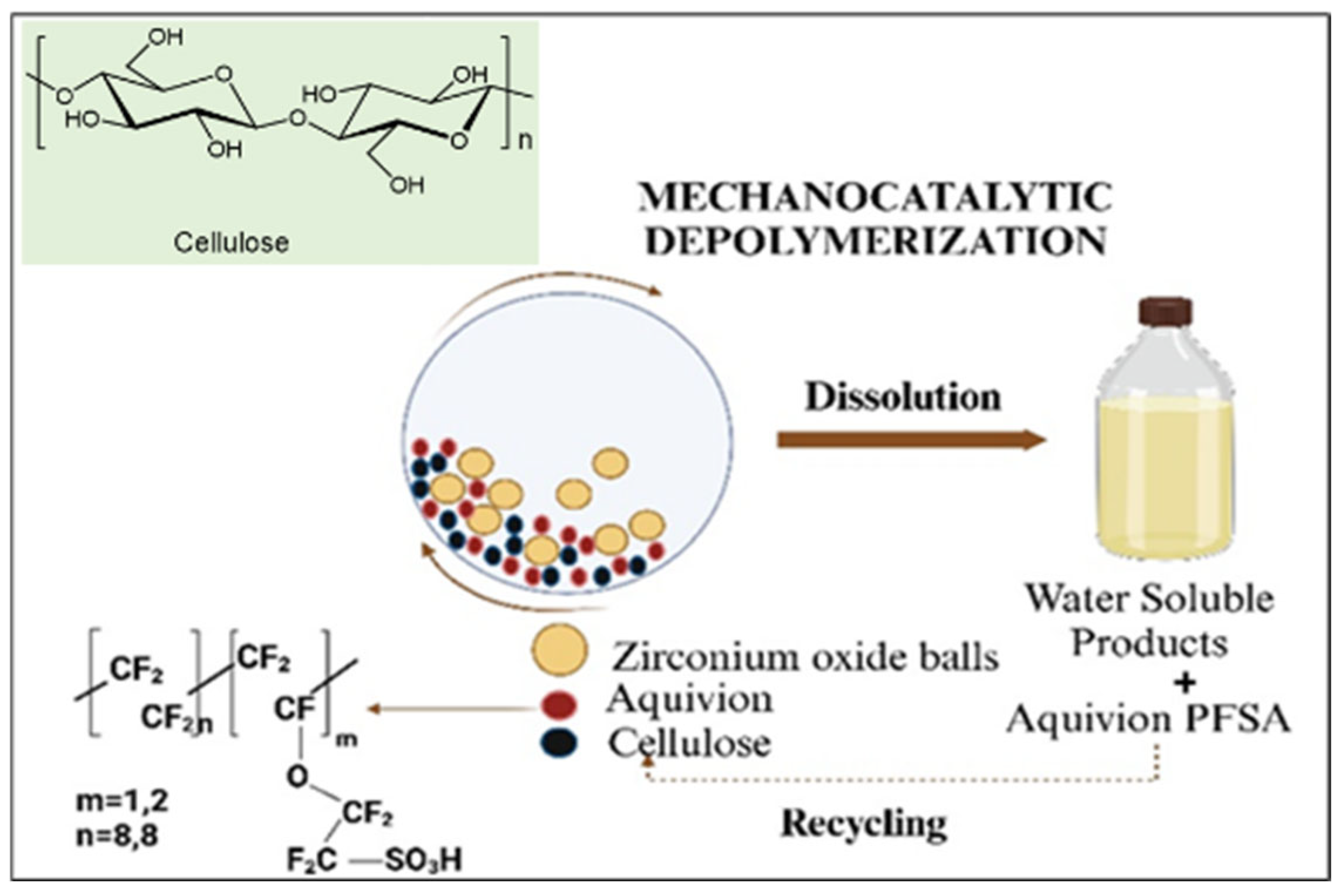

2.2. Mechanocatalytic Depolymerization of Cellulose

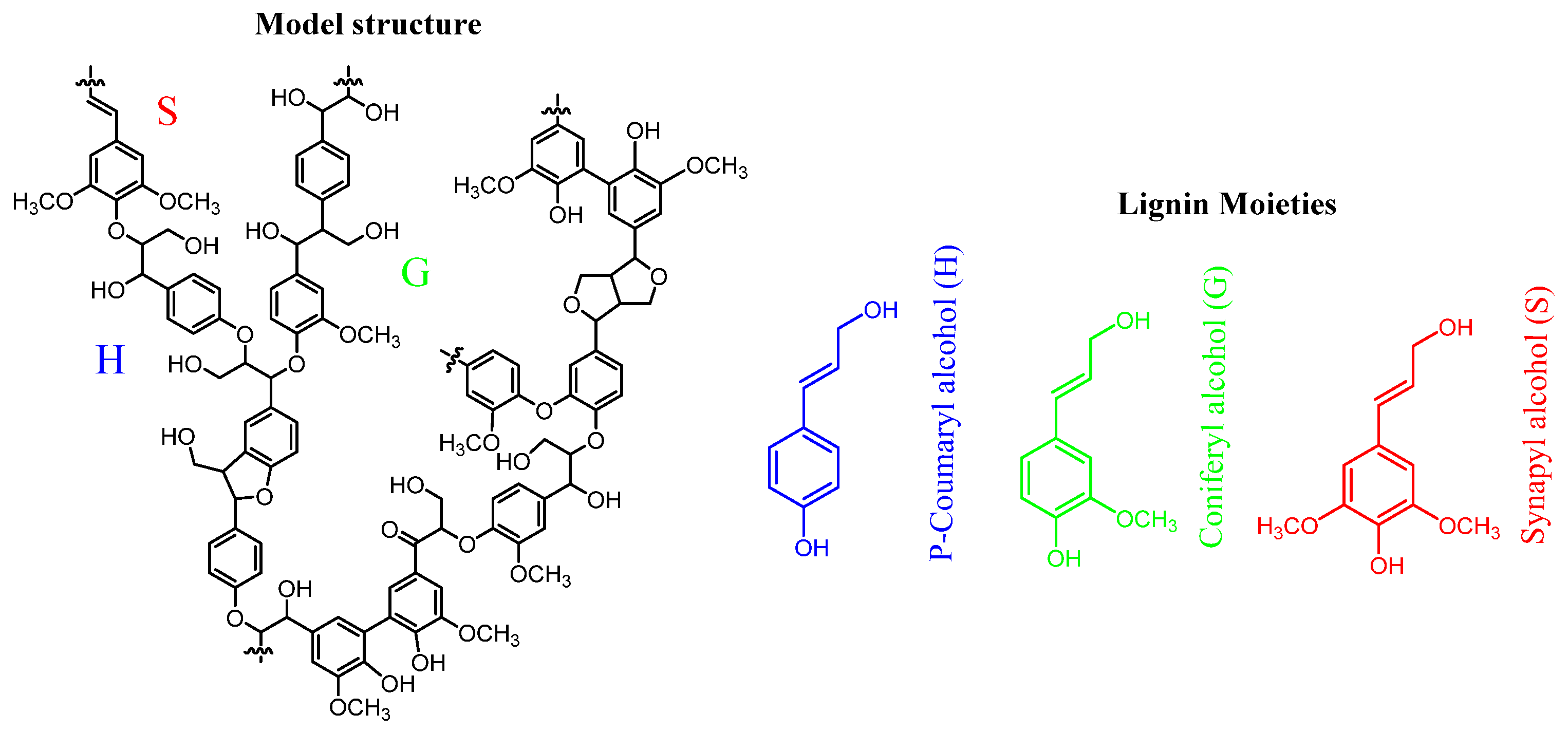

3. Catalytic Depolymerization of Lignin

3.1. Challenges and Opportunities

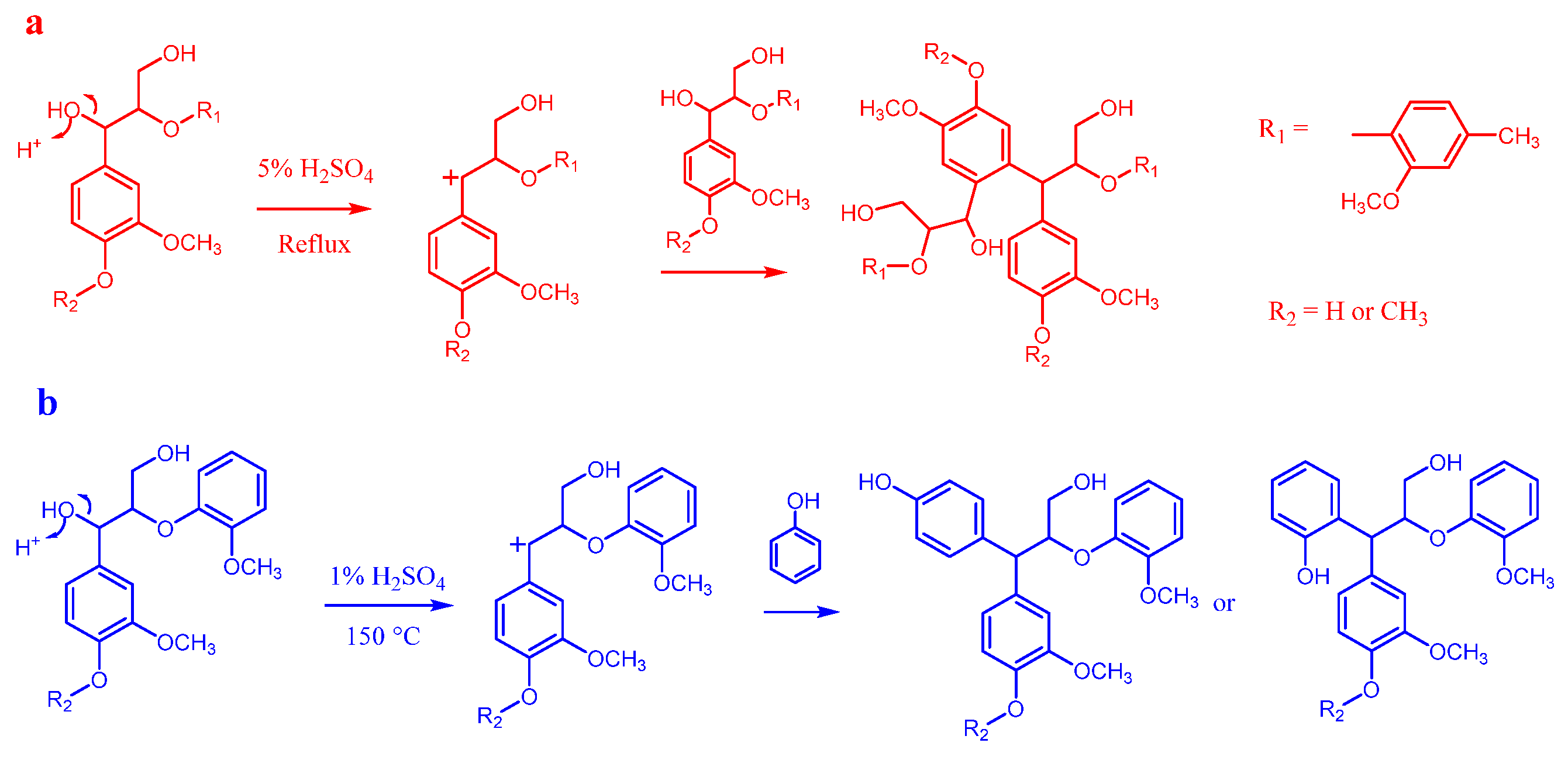

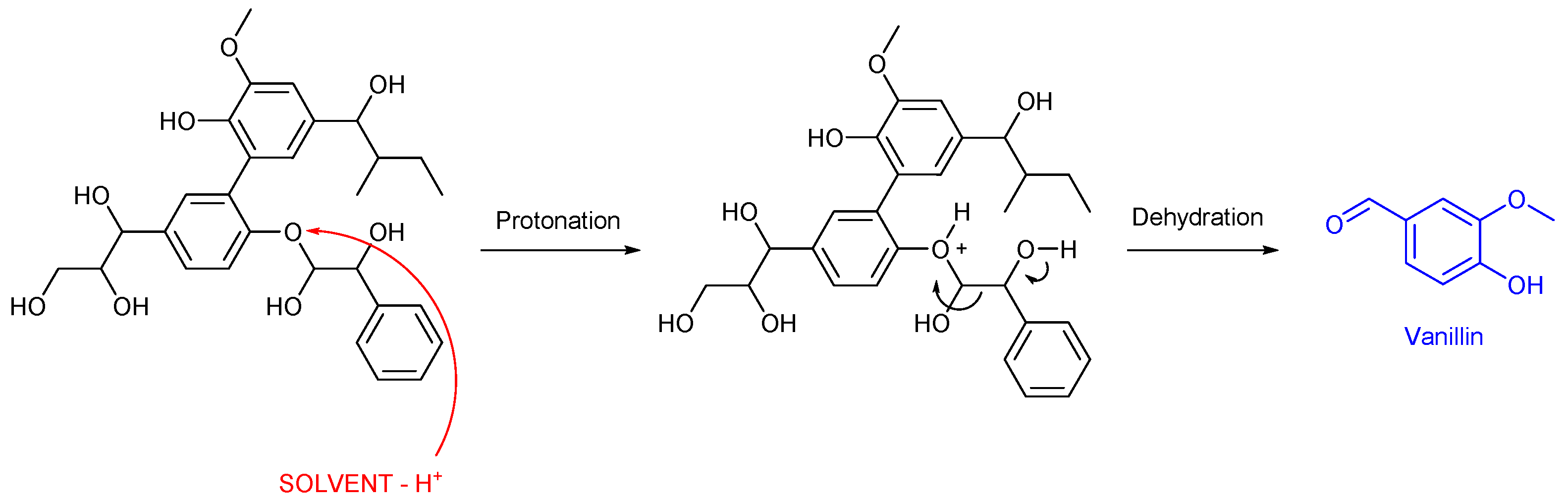

3.1.1. Homogeneous-Acid Catalysis

3.1.2. Homogeneous- Base Catalysis

Combined Acid-Base Catalysis

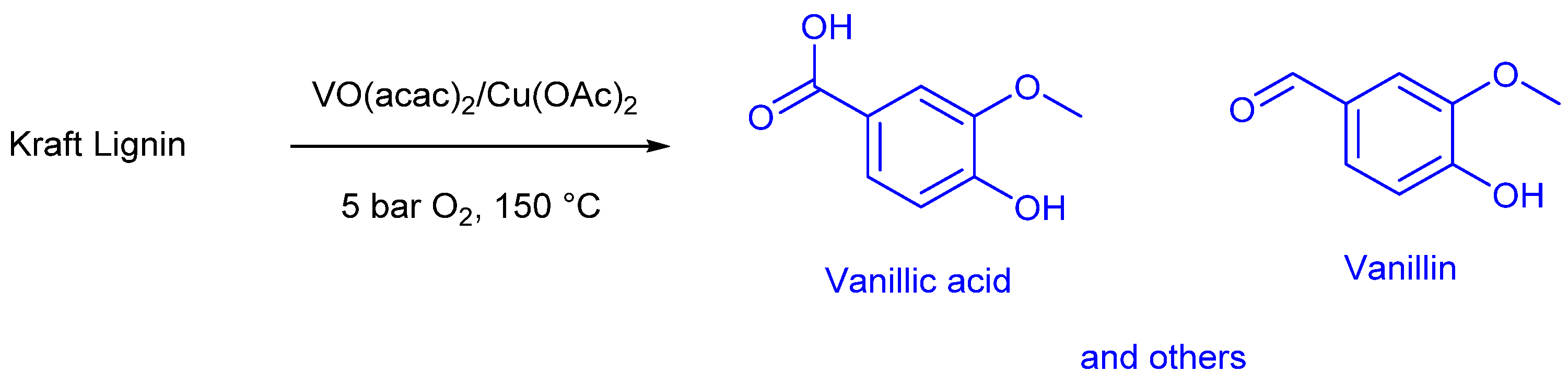

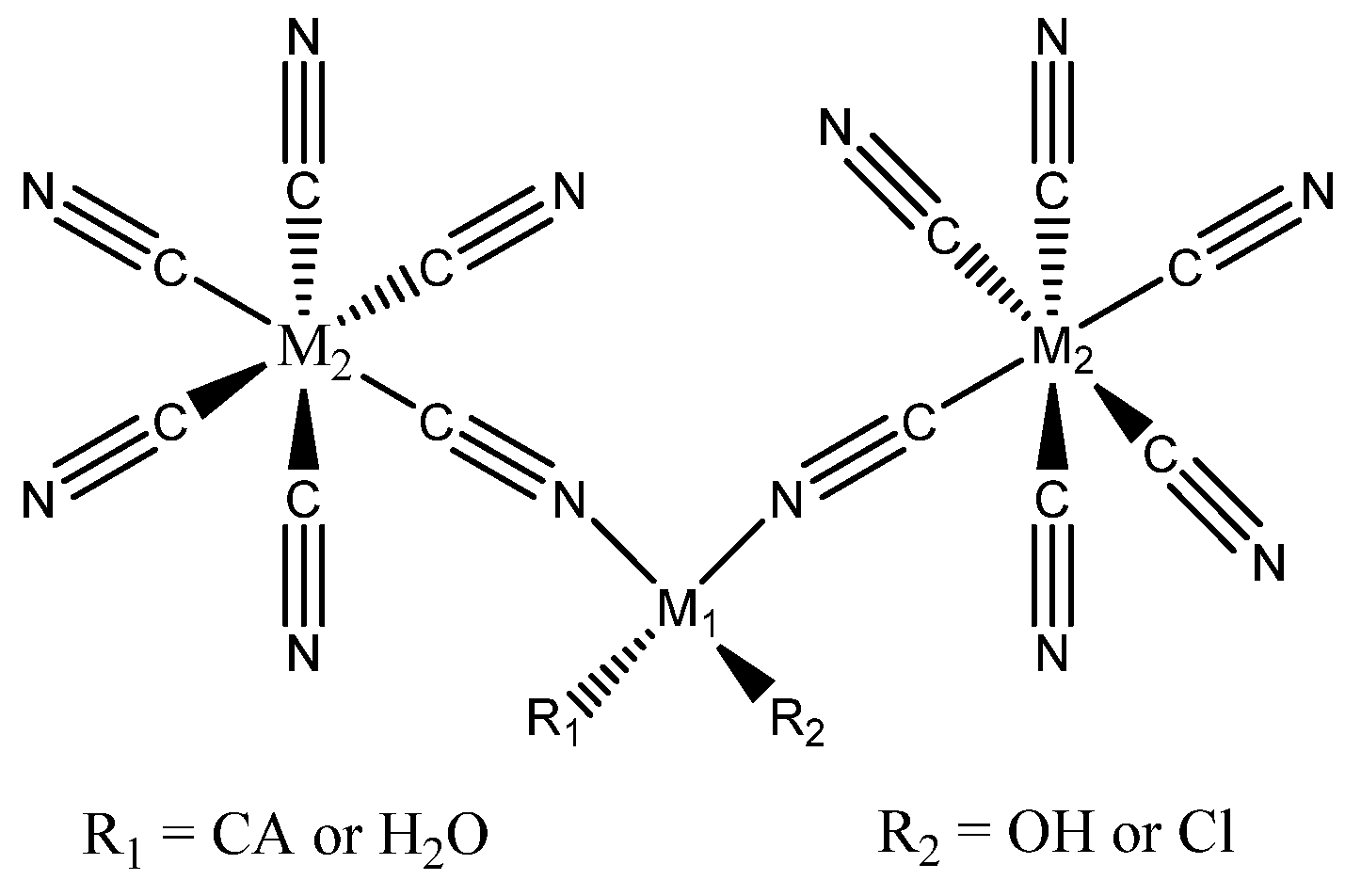

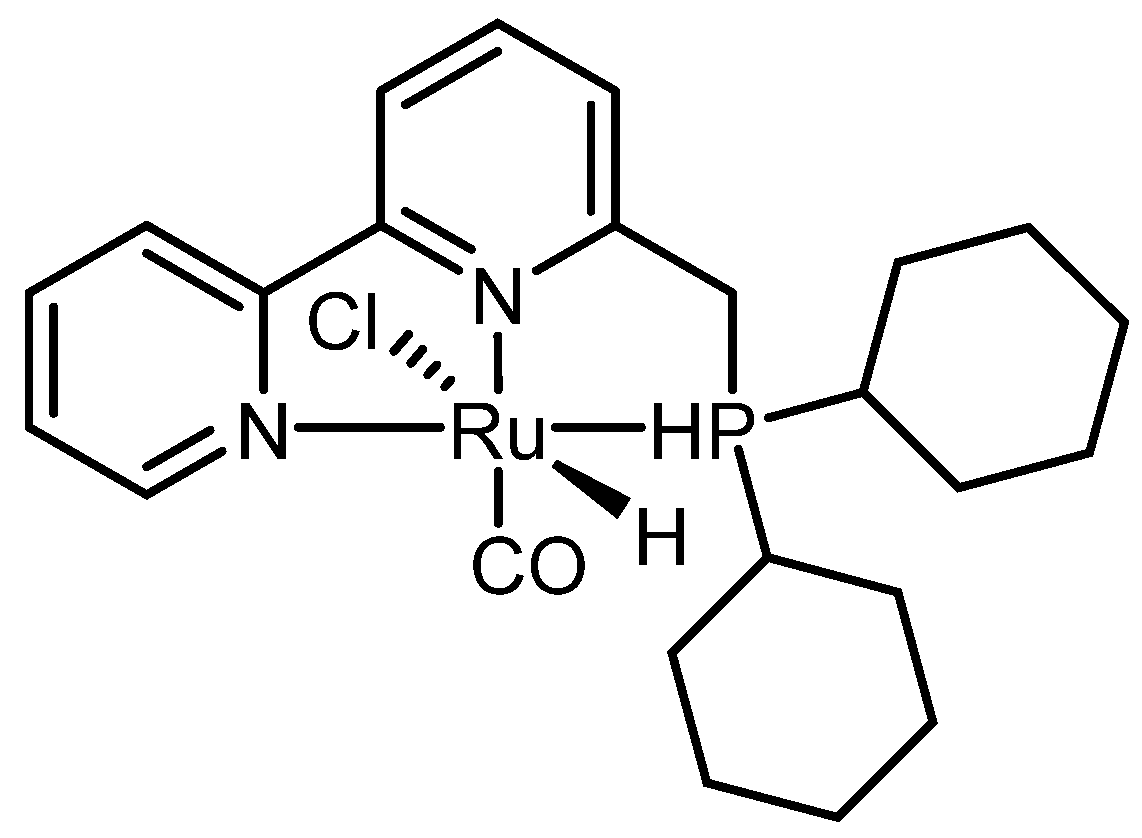

3.1.3. Homogeneous- Metal Catalysis

3.1.4. Heterogeneous – Solid acid Catalysis

3.1.5. Heterogeneous – Metal-supported Catalysis

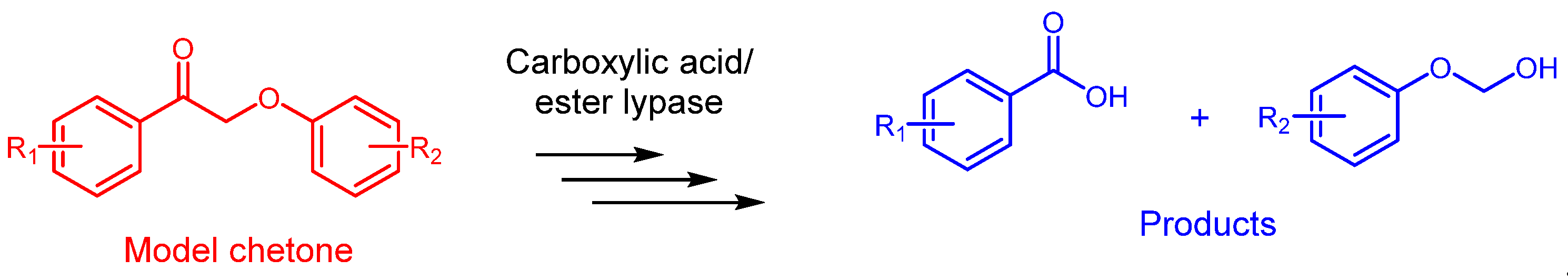

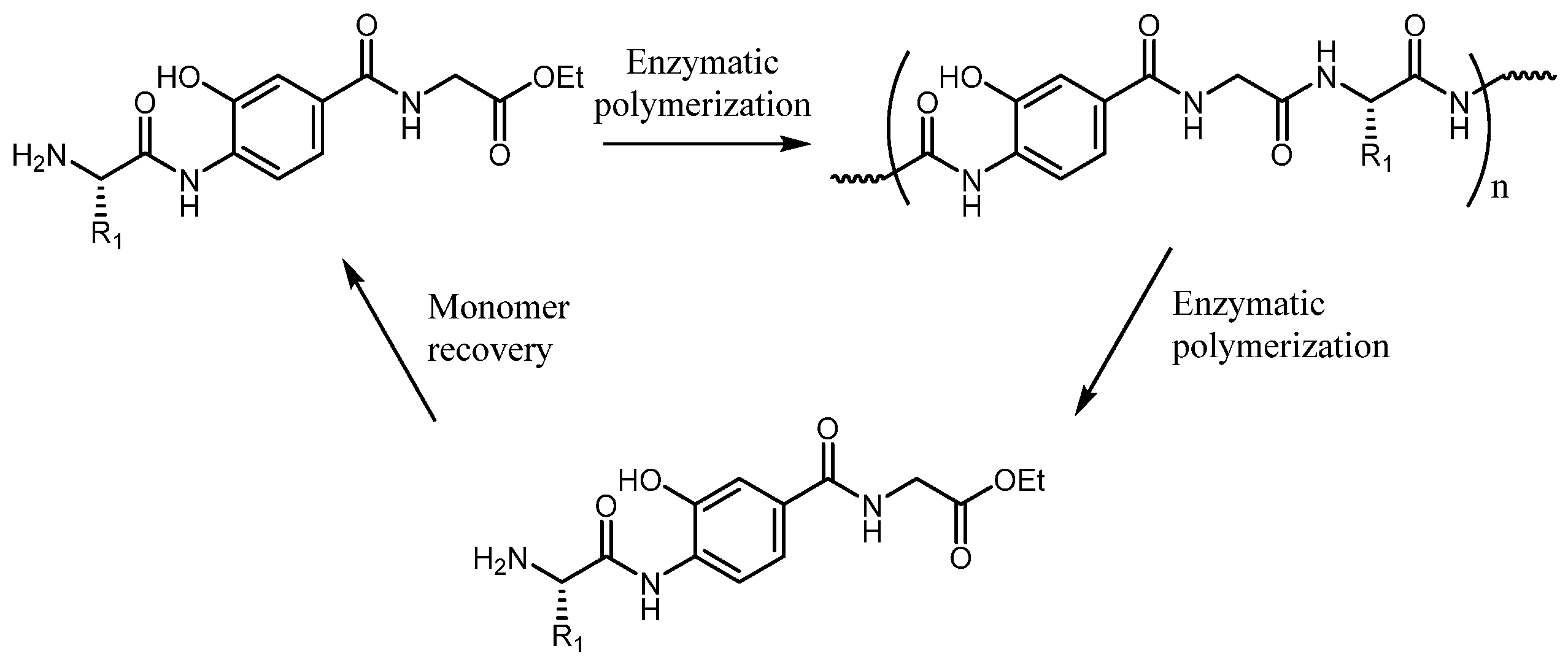

3.1.6. Enzyme Catalysis

Advantages of Enzyme Catalysis

Challenges and Limitations

Strategies for Improvement

4. Catalytic Depolymerization of Plastics

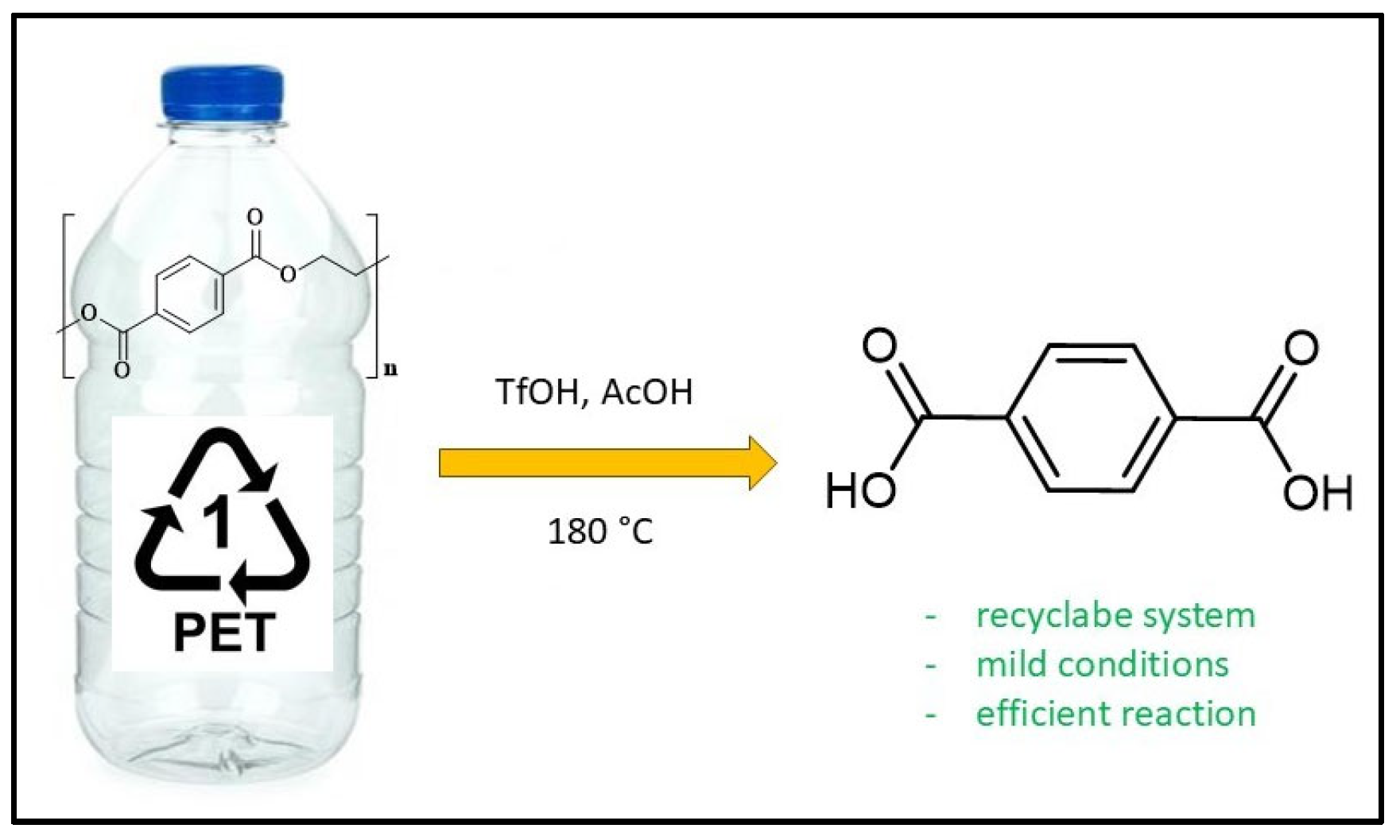

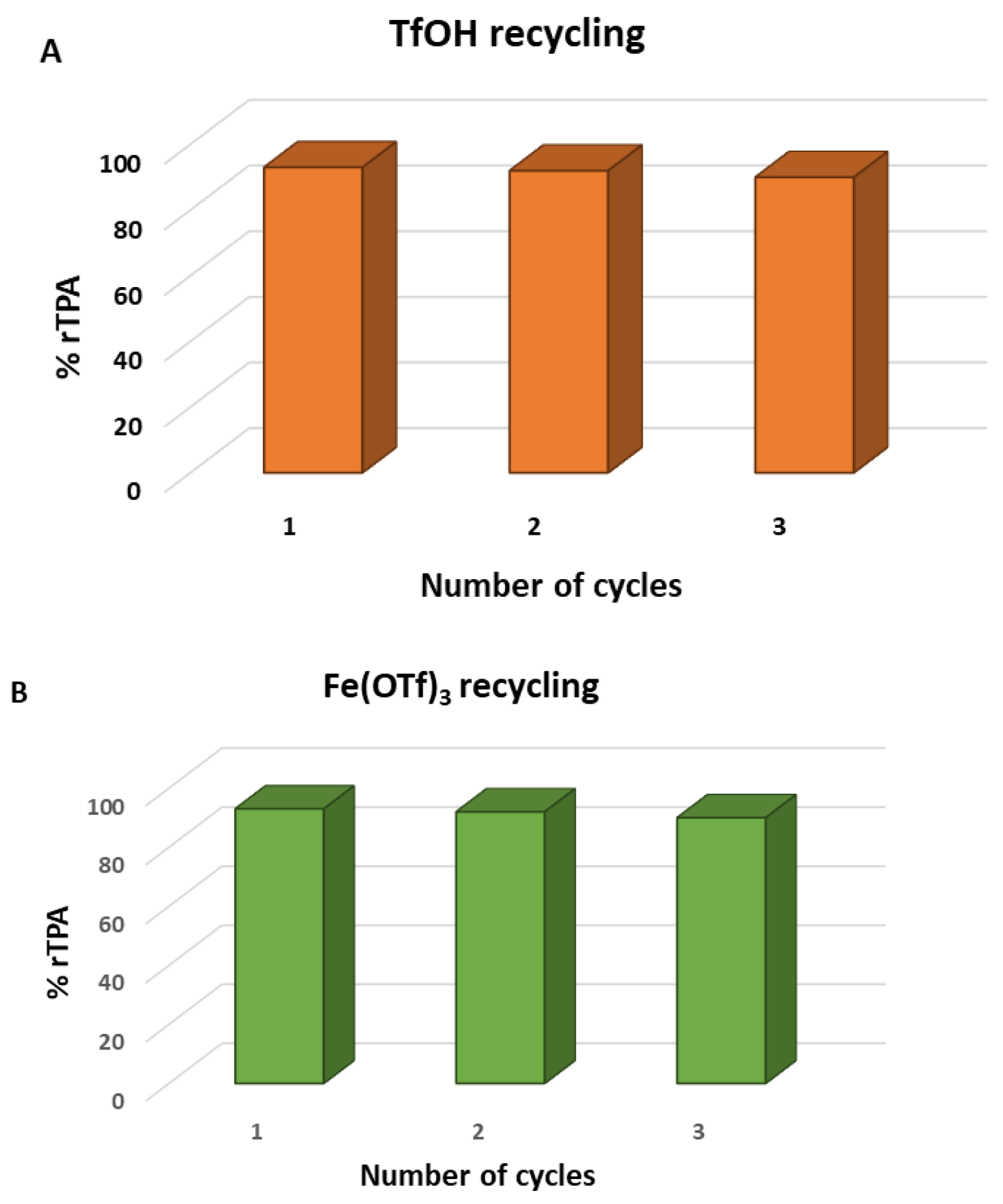

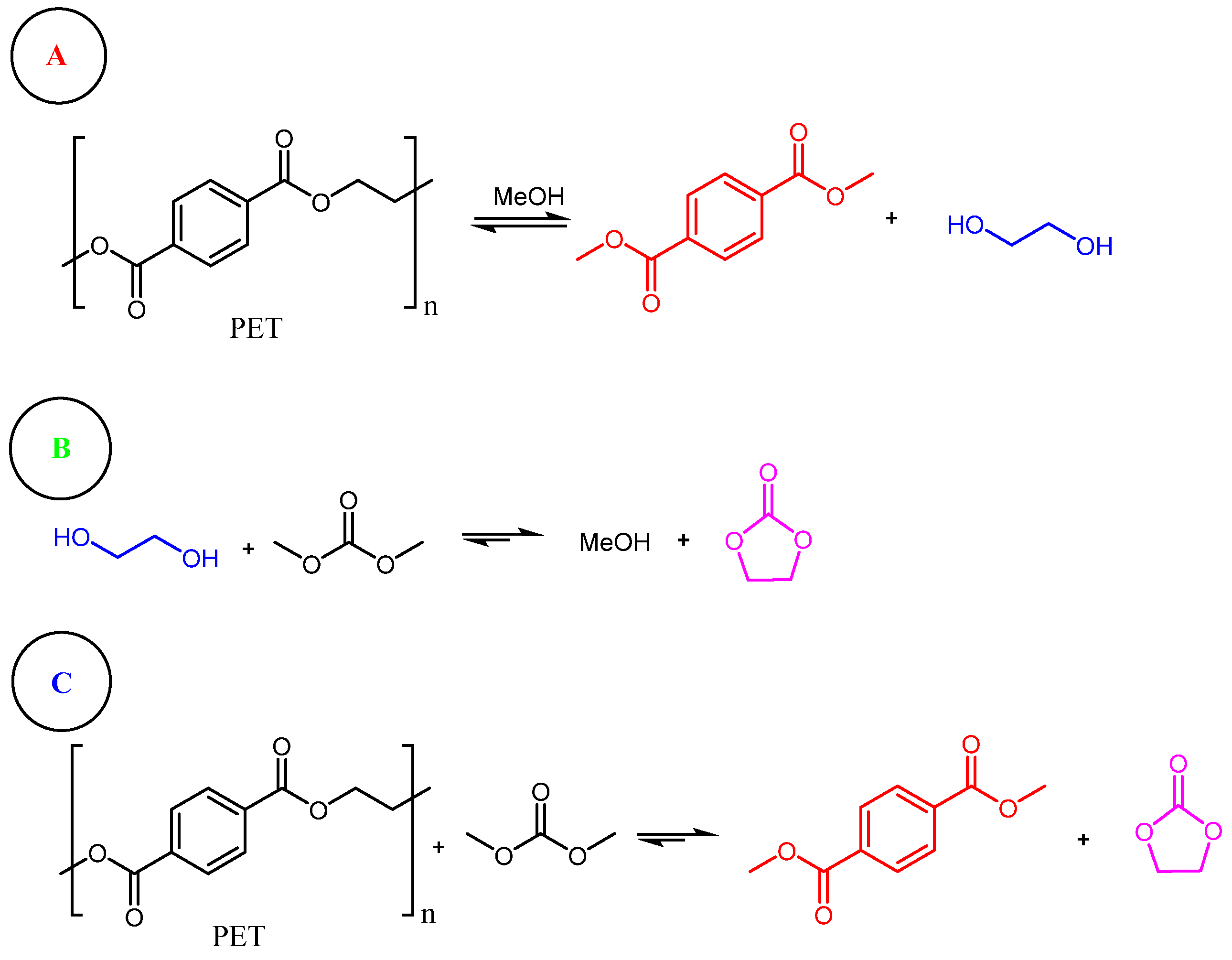

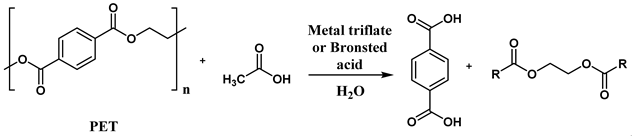

4.1. Depolymerization of Polyester Plastics

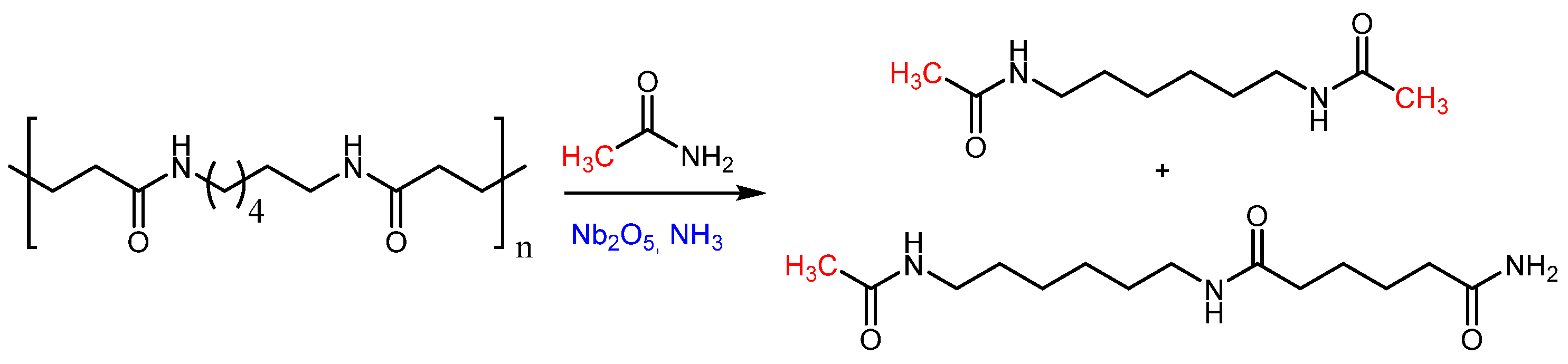

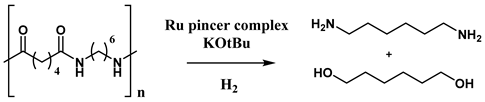

4.2. Depolymerization of Polyamides

4.3. Depolymerization of Polyurethanes

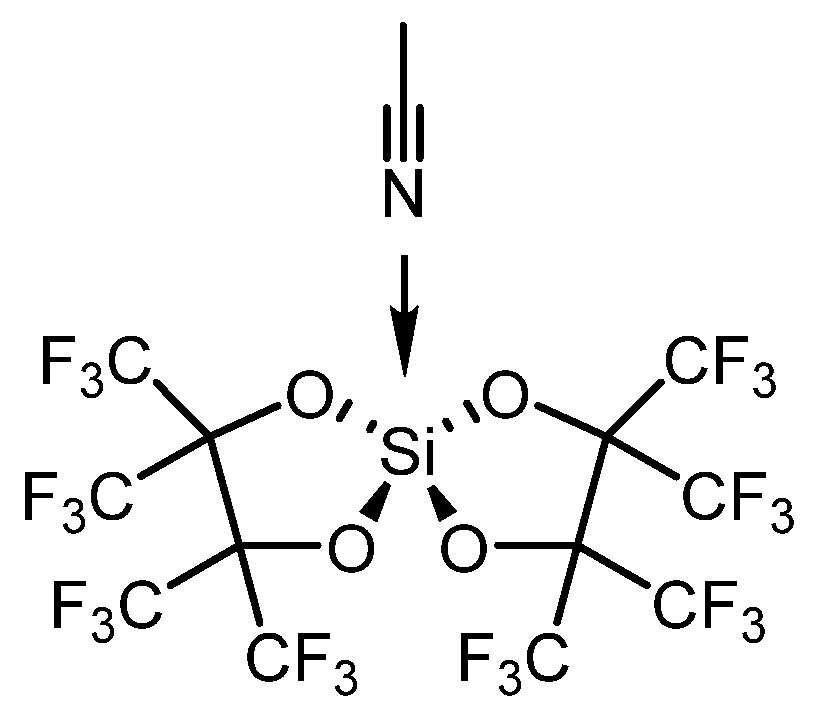

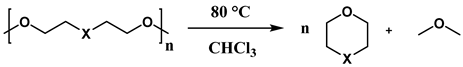

4.4. Depolymerization of Polyethers

5. Summary and Outlook

Future Challenges:

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kreps, B.H. The Moral Economy of Debt: A Critical Reappraisal. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 79, 695–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazouani, T.; Maktouf, S. Institutions, Natural Resources and Economic Growth in the MENA Region. Nat. Resour. Forum 2024, 48, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibunas, C.; Meys, R.; Kätelhön, A.; Bardow, A. Quantifying Climate Benefits of Circular Economy Strategies for Plastics. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2022, 162, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulamanti, A.; Moya, J.A. Energy Efficiency Trends in the EU. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axon, S.; James, D. The Role of Discourse Analysis in Understanding Student Perspectives on Sustainability. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2018, 13, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümmerer, K. Sustainable Chemistry: A Future Guiding Principle. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 16420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, V.G.; Eilks, I.; Elschami, M.; Kümmerer, K. Green and Sustainable Chemistry Education. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 1594–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, P.; Bernela, B.; Piccirilli, A.; Estrine, B.; Patouillard, N.; Guilbot, J.; Jérôme, C. Sustainable Chemistry: Toward a Cleaner and Greener Future. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 4973–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagnani, D.E.; Tami, J.L.; Copley, G.; Clemons, M.N.; Getzler, Y.D.Y.L.; McNeil, A.J. Chemically Recyclable Polymers: A Circular Economy Solution to Plastic Waste. ACS Macro Lett. 2021, 10, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Facchetti, A. Polymer Semiconductors for Flexible Electronics. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursi, A.; Olivito, F. Lignocellulosic Biomass Conversion. In Biomass Conversion: General Information, Chemistry, and Processes; Rahimpour, M.R., Kamali, R., Makarem, M.A., Manshadi, M.K.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Feng, Y.; Li, D.; Li, K.; Yan, Y. Catalytic Upgrading of Biomass-Derived Platform Molecules. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 9075–9103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zang, G.; Paul, M.C. Renewable Energy Applications for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 15182–15199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.; Guleria, A.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, S.; Singh, K. Recent Developments in Biodegradable Polymers. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1872–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etale, A.; Onyianta, A.J.; Turner, S.R.; Eichhorn, S.J. Advances in Lignocellulosic Biomass Conversion. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 2016–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiuolo, L.; Olivito, F.; Algieri, V.; Costanzo, P.; Jiritano, A.; Tallarida, M.A.; Tursi, A.; Sposato, C.; Feo, A.; De Nino, A. Biobased Polymers from Renewable Feedstocks. Polymers 2021, 13, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, I.; Olivito, F.; Tursi, A.; Algieri, V.; Beneduci, A.; Chidichimo, G.; Maiuolo, L.; Sicilia, E.; De Nino, A. Microwave-Assisted Reactions for Polymer Chemistry. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 34738–34751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Shrotri, A.; Fukuoka, A. Catalytic Processes in Biomass Upgrading. Appl. Catal. 2021, 621, 118177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyufekchiev, M.; Ralph, K.; Duan, P.; Yuan, S.; Schmidt-Rohr, K.; Timko, M.T. Thermochemical Conversion of Biomass. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.H.; Deswarte, F.E.I. Introduction to Chemicals from Biomass; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, T.J.; Mascal, M. Overview of Biomass-Derived Chemicals. In Introduction to Chemicals from Biomass; Clark, J., Deswarte, F., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yabushita, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Fukuoka, A. Catalytic Conversion of Cellulose. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 145, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, C.W.; Dale, B.E.; Jones, D.S.; Hossain, T.; Morais, A.R.C.; Wendt, L.M. Integration of Renewable Energy Systems. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivito, F.; Jagdale, P.; Oza, G. Sustainable Approaches to Polymer Synthesis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 17595–17599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomishige, K.; Yabushita, M.; Cao, J.; Nakagawa, Y. Green Catalysis for Biomass Utilization. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 5652–5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascal, M. Biomass-Derived Platform Molecules. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Bai, J.; Innocent, M.T.; Wang, Q.; Xiang, H.; Tang, J.; Zhu, M. Green Energy Technologies for Sustainable Development. Green Energy Environ. 2022, 7, 578–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethupathy, S.; Morales, G.M.; Gao, L.; Wang, H.; Yang, B.; Jiang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhu, D.B. Valorization of Agricultural Waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 347, 126696. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R.C. Lignin Valorization Strategies. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.; Mazumder, P.; Kalamdhad, A.S. Biotechnological Innovations in Waste Management. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 312, 123636. [Google Scholar]

- Mboowa, D. Sustainable Biomass Technologies for Renewable Fuel Production. Biomass Convers. Bioref. 2024, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Meng, Q.; Liu, H.; Han, B. Recent Advances in CO2 Conversion. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 3558–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagoz, P.; Khiawjan, S.; Marques, M.P.C.; et al. Lignin-Derived Platform Molecules. Biomass Convers. Bioref. 2024, 14, 26553–26574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo-Puerto, O.; Mendoza-Martinez, C.; Saari, J.; Vakkilainen, E. Renewable Energy from Forest Biomass. Fuel 2024, 373, 132389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Tang, B.; Peng, C. Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass. Fuel 2024, 361, 130726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X.; Xiong, Y.; Shi, Y.; Ma, L.; Dong, C.; Zhang, S.; Ji, N. Conversion of Cellulose to Biofuels. Green Chem. 2024. Advance Article. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenboom, J.G.; Langer, R.; Traverso, G. Biodegradable Polymers for Sustainable Packaging. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Awasthi, M.K.; Sheet, N.; Kharde, T.A.; Singh, S.K. Catalysts in Biomass Upgrading. ChemCatChem 2023, 15, e202300574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, K.; Denifl, P.; Hapke, M. Biocatalytic Upgrading of Lignin. ChemCatChem 2023, 15, e202300310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Nie, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, N.; Zhang, C. Advanced Materials for Biomass-Derived Electronics. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2404115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee Wong, M.; Lock, S.S.M.; Chan, Y.H.; Yeoh, S.J.; Tan, I.S. Green Engineering Approaches in Chemical Processes. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 468, 143699. [Google Scholar]

- Volanti, M.; Cespi, D.; Passarini, F.; Neri, E.; Cavani, F.; Mizsey, P.; Fozer, D. Life Cycle Assessment of Biomass Pathways. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Che, Y.; Niu, Z. Photocatalysis in Biomass Valorization. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 6200–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Akula, K.C.; Dandamudi, K.P.R.; Liu, Y.; Xu, M.; Sanchez, A.; Zhu, D.; Deng, S. Green Engineering for Polymer Recovery. Chem. Eng. 2022, 446, 137238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liang, H.; Yang, J.; et al. Photocatalytic Conversion of CO2. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; et al. Activated Clays in Biomass Processing. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; et al. Efficient Biomass Conversion Using Green Solvents. Green Chem. 2014, 1519–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; et al. Lignin-Based Biocomposites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 174, 114179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.C.; Voon, L.K.; Chin, S.F. Chitosan-Based Hydrogels: Synthesis and Applications. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; et al. Advances in Biomass Chemistry. Front. Chem. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Negi, A.; Kesari, K.K. Green Polymer Composites for Environmental Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Li, N.; Pan, X.; Chen, S.L. Nanocellulose Materials: Structure and Function. Cellulose 2020, 27, 9201–9215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, A.; Gräsvik, J.; Hallett, J.P.; Welton, T. Ionic Liquids for Lignin Processing. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; et al. Biomass Pretreatment Using Green Solvents. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 5030–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, M.F.; et al. Nanocellulose-Based Films for Packaging. Cellulose 2024, 31, 7953–7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Kennedy, J.R.; Tsilomelekis, G.; Zheng, W.; Nikolakis, V. Catalytic Conversion of Furfural. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 5226–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.R.; Song, Y.N.; Chen, C.Z.; Li, M.F.; Zhang, Z.T.; Fan, Y.M. Hemicellulose-Derived Products from Biomass. BioResources 2017, 12, 7807–7818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Wu, S. Biochar-Based Catalysts in Biofuel Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 241, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; et al. Recent Trends in Biomass Conversion. Biomass Convers. Bioref. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; et al. Hydrothermal Processing of Biomass. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 4240–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusato, S.; Takagaki, A.; Hayashi, S.; Miyazato, A.; Kikuchi, R.; Oyama, S.T. Catalysis for Biomass-Derived Fuels. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, A.; De Oliveira Vigier, K.; Marinkovic, S.; Estrine, B.; Oldani, C.; Jérôme, F. Acid Catalysts in Green Chemistry. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hick, S.M.; et al. Lignin Depolymerization Mechanisms. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 468. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, P.; et al. Agronomic Perspectives on Lignocellulosic Feedstocks. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lignin Market – By Raw Material, Product, Application, and Forecast 2024–2032. Market Research Report.

- Fernández-Rodríguez, J.; Erdocia, X.; Sánchez, C.; González Alriols, M.; Labidi, J. Optimization of Lignin Extraction Processes. J. Energy Chem. 2017, 26, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Flores, F.G.; Dobado, J.A. Green Chemistry Routes to Biomass-Derived Chemicals. ChemSusChem 2010, 3, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roy, R.; Jadhav, B.; Rahman, M.S.; Raynie, D.E. Recent Advances in Sustainable Chemical Synthesis. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.; Pradhan, D.; Du, H.; Mohapatra, S.; Thatoi, H. Hybrid Materials from Biomass. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2024, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Rahman, M.S.; Amit, T.A.; Jadhav, B. Biomass as Feedstock for Green Polymers. Biomass 2022, 2, 130–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Dhar, P.; Babaei-Ghazvini, A.; Nikkhah Dafchahi, M.; Acharya, B.B. Conversion of rice straw into valuable chemicals: Production of levulinic acid. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 22, 101463. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, C.C.; Silva, L.F.; Costa, J.A.V.; Bertolini, T.C.; Zepka, L.Q. Biochemical profile and bioactive potential of biomass from Spirulina strains: A comparative analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 123456. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, A.; Huber, G.W.; Zhang, T. Catalytic transformation of lignin for the production of chemicals and fuels. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11559–11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, N.P.; Kim, T.H.; Yoo, C.G. (Eds.) Biomass Utilization: Conversion Strategies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, M.; Domine, M.E.; Chávez-Sifontes, M. Catalytic cracking of waste plastics using natural clays and mesoporous materials. Curr. Catal. 2019, 8, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, N.; Yuan, Z.; Schmidt, J.; Xu, C.C. Production of chemicals from lignin: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 190, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanmolee, W.; Daorattanachai, P.; Laosiripojana, N. Effect of temperature on hydrothermal liquefaction of rice straw. Energy Procedia 2016, 100, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, K.J.; Wu, T.Y. Application of deep eutectic solvents in biomass pretreatment: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 384, 129238. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, L.; Hou, Q.; Mo, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, W. Fermentation of lignocellulosic biomass for ethanol production. Fermentation 2023, 9, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhavelikkakath Purushothaman, R.K.; van Erven, G.; van Es, D.S.; Rohrbach, L.; Frissen, A.E.; van Haveren, J.; Gosselink, R.J.A. Catalytic oxidative depolymerization of lignin in a flow-through system. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Qin, J.; Sun, S.; Gao, D.; Fang, Y.; Chen, G.; Tian, C.; Bao, C.; Zhang, S. Progress in developing methods for lignin depolymerization and elucidating the associated mechanisms. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 210, 112995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, D.; Cheng, X.; Li, H.; He, S.; Mu, M.; Cao, B.; Esakkimuthu, S.; Wang, S. Elucidating reaction mechanisms in the oxidative depolymerization of sodium lignosulfonate for enhancing vanillin production: A density functional theory study. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 179, 106499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paananen, H.; Eronen, E.; Mäkinen, M.; Jänis, J.; Suvanto, M.; Pakkanen, T.T. Base-catalyzed oxidative depolymerization of softwood kraft lignin. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 152, 112473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.H.; Kim, Y.I.; Um, B.H. Base-catalyzed depolymerization of organosolv lignin into monoaromatic phenolic compounds. Waste Biomass Valor. 2025, 16, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Kumar, A.; Krishna, B.B.; Bhaskar, T. Effects of solid base catalysts on depolymerization of alkali lignin for the production of phenolic monomer compounds. Renew. Energy 2021, 175, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Guo, G.; Shen, C.; Jiang, Y. Depolymerization of kraft lignin into liquid fuels over a WO3 modified acid-base coupled hydrogenation catalyst. Fuel 2022, 323, 124428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bouxin, F.P.; Fan, J.; Budarin, V.L.; Hu, C.; Clark, J.H. Recent developments in lignin valorisation via catalytic processes. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4296–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Ma, R.; Song, G. Catalytic valorization of lignin to functional materials and chemicals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2025, 58, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Singh, G.; Arya, S.K. Tandem catalytic approaches for lignin depolymerization: A review. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 6143–6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Wang, Y.; Peng, J.; Yuan, D.; Li, Z.; Ji, D.; Wu, H. Integrated catalytic process for lignin depolymerization: Advances and prospects. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 19916–19935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Evans, L.W.; Martin, D. Tandem catalysis strategies for lignin valorization. Green Chem. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Niu, M.; Guo, Y.; Li, H. Research progress on vanillin synthesis by catalytic oxidation of lignin: A review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 214, 118443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walch, F.; Abdelaziz, O.Y.; Meier, S.; Bjelić, S.; Hulteberg, C.P.; Riisager, A. Catalytic oxidative depolymerization of lignin to aromatic compounds. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 1843–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, O.Y.; Clemmensen, I.; Meier, S.; Walch, F.; Bjelić, S.; Riisager, A. Oxidative depolymerization of kraft lignin to aromatics over bimetallic V–Cu/ZrO2 catalysts. Top. Catal. 2023, 66, 1369–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, D.V.; Rodriguez, A.; Juarros, M.A.; Martinez, E.J.; Alam, T.M.; Simmons, B.A.; Sale, K.L.; Singer, S.W.; Kent, M.S. Advances in green chemistry for lignin transformation. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 1627–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Hu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Tang, Z. Recent advances in the acid-catalyzed conversion of lignin. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, C.; Chee, P.L.; Qu, C.; Fok, A.Z.; Yong, F.H.; Ong, Z.L.; Kai, D. Sustainable lignin-derived nanomaterials for energy and environment. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 2953–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, W.; Li, X. Selective depolymerization of corn stover lignin via nickel-doped tin phosphate catalyst in the absence of hydrogen. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 174, 114211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shen, X.; Jin, Y.; Cheng, J.; Cai, C.; Wang, F. Advances in catalytic lignin valorization. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 4510–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Qiu, S.; Wang, M.; Ju, C.; Cao, H.; Fang, Y.; Tan, T. Efficient catalytic conversion of lignin into valuable biofuels and chemicals. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2018, 2, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Mills, M.J.L.; Simmons, B.A.; Kent, M.S.; Sale, K.L. Catalytic conversion of lignin to bioproducts. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 2145–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, H.; Zhao, W.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Long, J.; Li, X. Lignin valorization strategies. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bai, X.; Wei, X.Y.; Dilixiati, Y.; Fan, Z.C.; Kong, Q.Q.; Li, L.; Li, J.H.; Lu, K.L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.Q.; Zong, Z.M.; Bai, H.C. Solid acid-catalyzed depolymerization of pine lignin to guaiacol. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 249, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knill, C.J.; Kennedy, J.F. Degradation of lignin: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2003, 51, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; et al. Biorefining of lignin waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 298, 122432. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.; Shi, C.; Liu, F.; Wang, W.; Ai, M.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Pan, L.; Zou, J.J. Advances in heterogeneous catalysts for lignin hydrogenolysis. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2306693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Kong, W.; Liang, W.; Guo, Y.; Cui, J.; Hu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Elangovan, S.; Xu, F. Metal-free catalysis in lignin depolymerization. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202401399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumi, D.O.; et al. Catalytic upgrading of lignin. Appl. Catal. B 2018, 232, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Kumar, A.; Krishna, B.B.; Baltrusaitis, J.; Adhikari, S.; Bhaskar, T. Catalytic fast pyrolysis of lignin. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 3813–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Song, W.; He, Z.; Yao, R.; Deng, Z. Metal-supported hydrotalcite catalysis for lignin depolymerization. Fuel 2023, 340, 127559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Omar, M.M.; Barta, K.; Beckham, G.T.; Luterbacher, J.S.; Ralph, J.; Rinaldi, R.; Román-Leshkov, Y.; Samec, J.S.M.; Sels, B.F.; Wang, F. Review on catalytic lignin valorization. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 262–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Xiao, L.P.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.H.; Guo, Y.; Zhai, S.R. Catalytic strategies for lignin transformation. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202200365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakka, A. Lignin-degrading enzymes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1994, 13, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofrichter, M. Enzymatic transformation of lignin. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2002, 30, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, R.; Xin, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, G.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, L. Enzyme-assisted lignin valorization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 5842–5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillies, J.; Vivien, C.; Chevalier, M.; Rulence, A.; Châtaigné, G.; Flahaut, C.; Senez, V.; Froidevaux, R. Enzymatic depolymerization of industrial lignins by laccase–mediator systems in 1,4-dioxane/water. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2020, 67, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Qin, J.; Sun, S.; Gao, D.; Fang, Y.; Chen, G.; Tian, C.; Bao, C.; Zhang, S. Progress in developing methods for lignin depolymerization. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 210, 112995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajer, N.; Gigli, M.; Crestini, C. Functional lignin derivatives from green processes. ChemSusChem 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Han, D.O.; Shim, K.I.; Kim, J.K.; Pelton, J.G.; Ryu, M.H.; Joo, J.C.; Han, J.W.; Kim, H.T.; Kim, K.H. Molecular insights into lignin depolymerization. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 3996–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournier, V.; Topham, C.M.; Gilles, A.; David, B.; Folgoas, C.; Moya-Leclair, E.; Kamionka, E.; Desrousseaux, M.L.; Texier, H.; Gavalda, S.; et al. An engineered PET depolymerase to break down and recycle plastic bottles. Nature 2020, 580, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Rorrer, N.A.; Nicholson, S.R.; Erickson, E.; DesVeaux, J.S.; Avelino, A.F.T.; Lamers, P.; Bhatt, A.; Zhang, Y.; Avery, G.; et al. Enzymatic and microbial degradation of plastics. Joule 2021, 5, 2479–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, Z. Catalytic lignin valorization in green chemical engineering. Green Chem. Eng. 2024, 5, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Koga, M.; Kuragano, T.; Ogawa, A.; Ogiwara, H.; Sato, K.; Nakajima, Y. Advanced materials for polymer degradation. ACS Mater. Au 2024, 4, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Aguirre-Villegas, H.A.; Allen, R.D.; Bai, X.; Benson, C.H.; Beckham, G.T.; Bradshaw, S.L.; Brown, J.L.; Brown, R.C.; Cecon, V.S.; et al. Sustainable approaches in lignin valorization. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 8899–9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Shukla, S.; Singh, A.A.; Arora, S. Resource conservation and recycling of polymers. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Sato, J.; Nakajima, Y. Catalytic strategies for lignin valorization. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 9412–9416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Aireddy, D.R.; Roy, A.; Ding, K. Catalytic depolymerization of lignin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202309949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordy, W.; Thomas, W.J.O. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies. J. Chem. Phys. 1956, 24, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Hu, Y.; Shi, N.; Zou, X.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Li, N.; Guo, K. Advances in catalytic lignin processing. Catal. Today 2025, 452, 115241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.P.; Vázquez-Vélez, E.; Galván-Hernández, A.; Martinez, H.; Torres, A. Polymer applications and sustainability. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakiba, M.; Rezvani Ghomi, E.; Khosravi, F.; et al. Polymer advances and technologies. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2021, 32, 3368–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberg, V.; Rodrigue, D. Polymer science insights. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 61, 1937–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Neumann, P.; Al Batal, M.; Rominger, F.; Hashmi, A.S.K.; Schaub, T. Catalytic lignin conversion. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 4176–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coeck, R.; De Vos, D.E. Catalysis and green chemistry. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 1444–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, G.L.; Short, R.D. Toxicology reviews in polymers. CRC Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1986, 17, 129–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, K.; Masunaga, H.; Numata, K. Sustainable polymer chemistry. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 3994–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, G.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, C.; Chen, Y. Polymer science innovations. J. Polym. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akindoyo, J.O.; Beg, M.D.H.; Ghazali, S.; Islam, M.R.; Jeyaratnam, N.; Yuvaraj, A.R. Polymer advances and applications. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 114453–114482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiuolo, L.; Olivito, F.; Ponte, F.; Algieri, V.; Tallarida, M.A.; Tursi, A.; Chidichimo, G.; Sicilia, E.; De Nino, A. Reactive polymer chemistry. React. Chem. Eng. 2021, 6, 1238–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivito, F.; Algieri, V.; Jiritano, A.; Tallarida, M.A.; Costanzo, P.; Maiuolo, L.; De Nino, A. Polymer synthesis and characterization. Polymers 2023, 15, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivito, F.; Jagdale, P.; Oza, G. Toxicology in polymer science. Toxics 2023, 11, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouren, A.; Avérous, L. Polymer environment interactions. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 197, 112338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corapi, A.; Gallo, L.; Lucadamo, L.; Tursi, A.; Chidichimo, G. Environmental toxicology and polymers. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2023, 42, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubar, V.; Haedler, A.T.; Schütte, M.; Hashmi, A.S.K.; Schaub, T. Sustainable catalysis for polymers. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, G.; Ferrier, R.C., Jr. Advances in polymer science. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 59, 2704–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, L. Applied polymer science. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, e50154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeno, Z.; Yamada, S.; Mitsudome, T.; Mizugaki, T.; Jitsukawa, K. Green polymer chemistry. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 2612–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansmann, N.; Thorwart, T.; Greb, L. Innovative polymer approaches. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202210132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschernuth, F.S.; Bichlmaier, L.; Inoue, S. Catalytic polymer chemistry. ChemCatChem 2023, 15, e202300281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansmann, N.; Johann, K.; Favresse, P.; Johann, T.; Fiedel, M.; Greb, L. Mechanistic studies in polymer catalysis. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202301615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of cellulose | Mean DPw peak 0 min and 120 min |

Percentage change of DPw ΔDPw (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sawdust | 351 | 72 | 79.5 |

| Sago pith wastes | 564 | 30 | 94.7 |

| Corn Cob | 329 | 88 | 78.1 |

| Sugarcane bagasse | 571 | 37 | 93.5 |

| Substrate | MSH/Catalyst | Main products (%yield) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCC | Beta and ZSM-5 zeolites with SiO2/Al2O3 = 30 and 50 | Gluco oligomers (54.4%), glucose (28.3%) & HMF (0.2%) | [52] |

| MCC | ZnCl2 (72wt%)/HCl (0.2 M) | HMF (69.5%) | [57] |

| Cellulose | ZnCl2·3H2O/SO4/TiO2 | Gluco oligomers (9.4%), glucose (50.5%), HMF (3.4%), fructose (5.9%), & LA (5.1%) | [58] |

| MCC | LiBr (55 wt%) Activated/Activated carbon | Glucose (80%) & LA (4%) | [59] |

| Catalyst | H+ exchange capacity(mmol/g) | Solubility (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Blank | - | <5 |

| Aquivion PW98 | 1.0 | 90 |

| SBA – SO3H | 0.2 | 60 |

| CMK-3-SO3H | 0.7 | 87 |

| Kaolinite | - | 50 |

| Aquivion PW66 | 1.45 | 99 |

| Aquivion PW79 | 1.26 | 32 |

| Aquivion PW87 | 1.15 | 80 |

| Material | Diameter (mm) | Density (g/cm−3) |

|---|---|---|

| Zirconia | 3 | 5.68 |

| Stainless steel | 2 | 7.8 |

| Stainless steel | 4 | 7.8 |

| Tungsten carbide | 3 | 15.63 |

| Catalyst | Products yield (%) |

|---|---|

| HNbMoO6 | 14 |

| kaolinite | 4 |

| NiO | 0.3 |

| SnO2 | 0.6 |

| TiO2 | 0.5 |

| Nb2O5 | 0.9 |

| H-Montmorillonite | 3 |

| USY zeolite | 3 |

| Mg–Al HT | 0 |

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst | T (°C) | Ccat (M) | CH20 (M) | Yield (%) |

| Hf(OTf)4 | 180 | 0.25 | 0 | 60 |

| Hf(OTf)4 | 180 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 72 |

| Fe(OTf)3 | 180 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 64 |

| Al(OTf)3 | 180 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 60 |

| TfOH | 180 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 98 |

| Tf2NH | 180 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 58 |

| Catalyst | DMC (mL) | MeOH (mL) | DMT (%) | EC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiOMe | 1.5 | 0.2 | 83 | 70 |

| KOMe | 1.5 | 0.2 | 95 | 93 |

| NaOMe | 1.5 | 0.2 | 95 | 86 |

| NaOMe [b] | 1.5 | 0.2 | 93 | 92 |

| NaOMe | 1 | 0.13 | 98 | 67 |

| NaOMe | 0.5 | 0.065 | 93 | 60 |

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| T (°C) | P (H2) Bar | Yield (%) Diamine | Yield (%) Diol |

| 150 | 70 | 12 | < 5 |

| 180 | 100 | 60 | 35 |

| 200 | 100 | 78 | 62 |

| 200 | 80 | 70 | 47 |

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | Catalyst (%mol) | Time (h) | Yield (%) |

| 1,5 DMP | 1-5 | 1-20 | 96-97 |

| Diglyme | 1-5 | 2.5-96 | 96-99 |

| 18-crown-6 | 30 | 30 | 88 |

| PEG-DME | 225 | 18 | 87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).