1. Introduction

Golden Syrian hamsters (

Mesocricetus auratus) is considered a model of choice and has been extensively used as a preclinical model for studying lipid metabolism because of their similarities to human fatty acid metabolism [

1]. The objective of this work was to knock out the hemoglobin β-chain (

HBB) gene in hamster to produce a β-thalassemia animal model that also has lipid metabolism resembling that of humans. Hemoglobin exists predominantly in erythrocytes as a tetramer comprised of 2 alpha (α) chains and 2 beta (β) chains (α

2β

2). The

HBB gene codes for the hemoglobin (Hb) β-chain. β-thalassemia intermedia describes patients that carry genetic mutations in the

HBB gene with insufficient β-chain production for fully functional Hb tetramers to be formed. Some of these intermedia patients require blood transfusions while others do not. Further, intermediate β-thalassemia is a disease of ineffective erythropoiesis and iron over-load, independent of the need or frequency of blood transfusions. A state of iron overload in β-thalassemia patients is characterized by dysregulation of the hepcidin-ferroportin axis leading to transferrin saturation and tissue iron accumulation [

2]. Iron partitioning to tissue is an important contributor toward lipid oxidative processes and organ injury [

3]. It has been shown that β-thalassemia intermedia patients are at higher risk of atherosclerosis due to their LDL being relatively susceptible to lipid and protein oxidation [

4]. β-thalassemia major patients (homozygous for

HBB null mutations) require chronic transfusions and have shortened life expectancy [

5]. Characteristics of patients with β-thalassemia include decreased total cholesterol and high-density lipoproteins and increased triglycerides [

6]. Thus, establishing an animal model of β-thalassemia with lipid composition and metabolism similarities to humans should be advantageous. In this regard, the Syrian hamster offers unique advantages over murine species in that, while both humans and hamsters use cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) in regulating lipid metabolism, neither mice nor rats carry the gene encoding CETP [

7]. Therefore, towards the goal of establishing a translational small animal model for β-thalassemia, we employed the CRISPR/Cas-mediated gene targeting technique that we developed in the Syrian hamster to knock out one of the hamster

HBB genes and characterized the phenotypes of this novel hamster model. Our study provided one step forward in developing more suitable animal models for β-thalassemia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

The golden Syrian Hamsters (Crl:LVG) were in-house bred at Laboratory Animal Research Center (LARC) in Utah State University and maintained in an air-conditioned room with a light cycle of 14L:10D.

2.2. Generation of HBB Knock out Golden Syrian Hamster by CRISPR/Cas9

sgRNA design, embryo manipulation and PN injection were performed as described previously [

8,

9]. Briefly, sgRNA was designed by using a web tool at Benchling (

https://www.benchling.com/) and its efficiency in indel induction was tested in BHK cells by transfecting sgRNA/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex into BHK cells using Lonza nucleofector (V4XP-3024; EN-150). To produce HBB KO hamsters, donor female hamsters were superovulated by PMSG injection intraperitoneally on Day 1, and then mated with males on Day 4 late afternoon. 18 hours later, the females were euthanized by CO2, and zygotes were flushed out and cultured in HECM-9 medium at 37.5 ℃ under 10% CO2, 5% O2. 50 ng sgRNA mRNA with Cas9 protein was injected into the pronuclei of zygotes followed by transferring the injected embryos to the oviducts of pseudopregnant recipient hamsters.

To genotype the founder hamsters produced from the pronuclear injection experiments and the animals from following generations, genomic DNA was isolated from toe clippings using Qiagen Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen Cat:69506). PCR was performed with the Ex Taq (Takara, Cat: RR001A) and the following parameters: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min followed by 32 cycles of 30 s denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s annealing at 58 °C and 30 s extension at 72 °C, with a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min. Primers for genotyping transgenic pups were: Forward primer 5’-TTAAGCCTCACCCAGTAGCACC-3’; Reverse primer 5’- CTTTTGTCAGCACTCCACGTGG-3’.

2.3. Blood Collection

Hamsters were anesthetized with isoflurane and blood was drawn by cardiac puncture into heparin coated tubes for hemolysis assay and MS analysis.

2.4. Hemolysate Preparation

Hemolysates were prepared from anticoagulated blood as described previously [

10]. Blood was obtained from hamsters that were 4-5 months of age.

2.5. Electrospray Ionization—Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS)

Intact ESI-MS was used to determine the mass of the α- and β-chain(s) in the hemolysates. Protein extracts [5µg] were denatured with neat formic acid (2:1 protein:acid vol:vol) and immediately diluted with 50% MeOH to a final 0.5µg/ul concentration. Two µl was injected using syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus) flowing at 40 µl/min with 50:50 (acetonitrile:water) into hybrid linear ion trap-orbitrap mass spectrometer (LTQ-Orbitrap Elite™, Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an HESI™ electrospray source. The following source conditions were established for the most efficient ionization in the positive mode, source voltage: 3.1kV, gas temperature: 300°C, sheath gas flow: 10, S-Lens RF level: 50%, source fragmentation: 20v and capillary temperature: 350°C. Survey MS scans were acquired in the Orbitrap with a resolution of 120,000 over 500-2,000 m/z range. Raw spectra were exported as csv files and subsequently charge state deconvoluted to intact protein masses using MagTran software [ver.1.03 b2]. Manual chromatogram and spectral follow up analyses were done using Qual Browser function in Thermo Xcalibur ver. 4.1.50 (Thermo Scientific).

2.6. Hemolysis Assay

Anticoagulated whole blood was exposed to increasing concentrations of H2O2 and hemolysis was determined in supernatants as described previously [

11].

2.7. Preparation of Minced Leg and Thigh Muscle and 2 °C Storage

Muscle tissue was obtained from hamsters that were 4-5 months of age. Leg and thigh muscles (soleus, tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and gastrocnemius) were kept at 4°C prior to deboning 24 h post-mortem. The muscles from each hamster were minced with a scalpel at 4°C to obtain the comminuted tissue. NaCl (1% w/w) was added as a solution to obtain 5 g of added solution per 95 g minced tissue. The mince was added to plastic petri dishes (3 cm diameter) overwrapped with SealWrap having an oxygen transmission rate 635 cc/100 in.2/day (AEP Industries, South Hackensack, NJ) and stored at 2°C under light display (1400 to 1700 LUX). pH values of WT and Hmz KO were 6.34 ± 0.16 and 6.28 ± 0.05, respectively.

2.8. Redness Determination

Redness was determined using a colorimeter as described previously [

12]. A white plate was used for calibration.

2.9. Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS)

TBARS, which quantify secondary lipid oxidation products, were determined as described previously with some modifications [

13]. The modification was that 1 gram of tissue was extracted with 6 ml of trichloroacetic acid solution.

2.10. Statistical Evaluations

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with statistical software (JMP, v. 15.0.0, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Repeated measures were used during storage and treatment was nested within animal in the model; a univariate split plot approach was used. Significance was set at p < 0.05 with the Student’s t-test used to differentiate means when a significant effect was found.

2.11. Ethics Statement

All animal studies were conducted in strict accordance with the guidelines of LARC and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Utah State University (IACUC#11613 and IACUC#13758). All surgeries were performed under Ketamine/Xylazine anesthesia.

3. Results

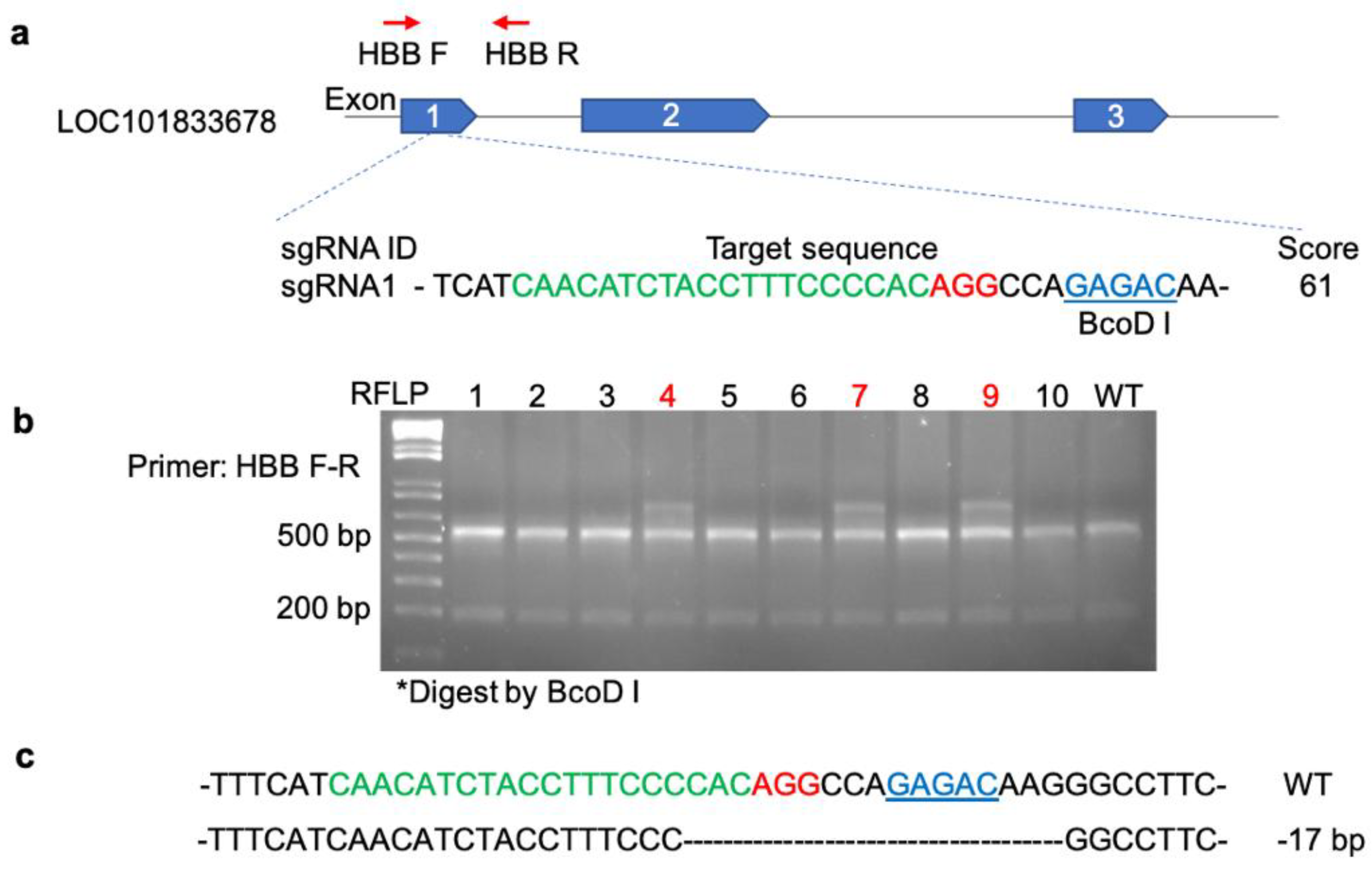

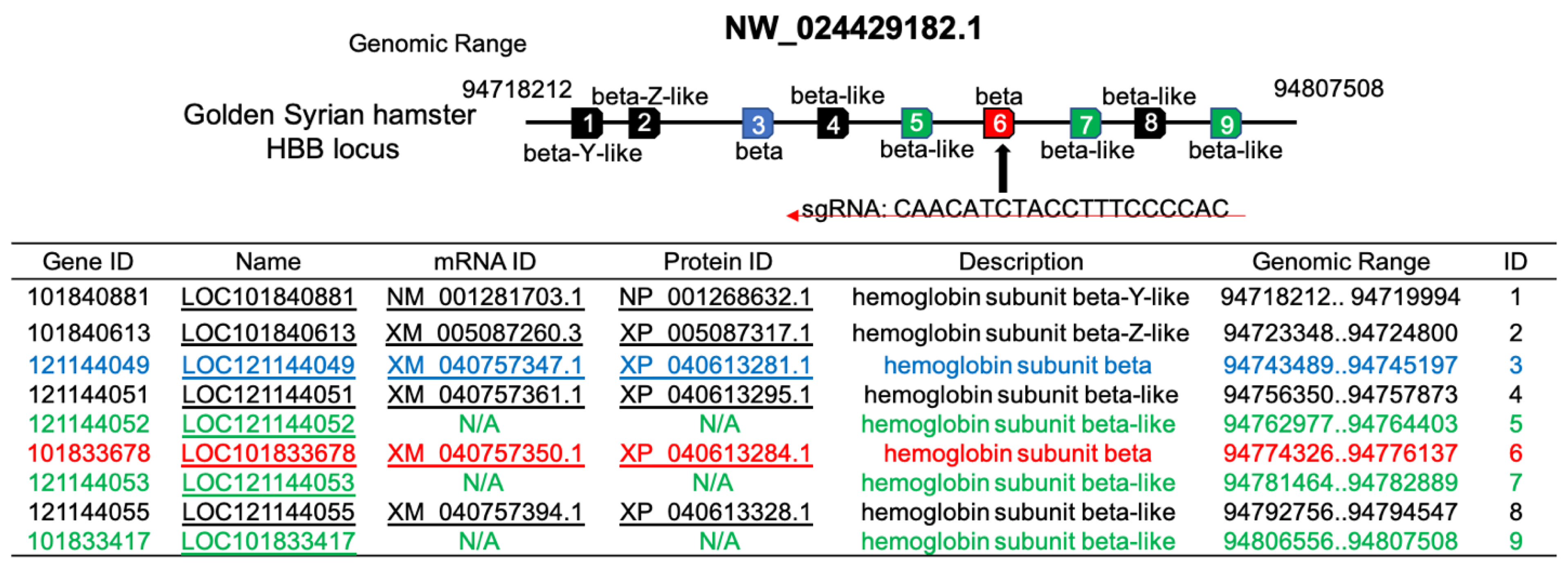

3.1. Knockout of the Hamster HBB Gene

We chose the hemoglobin beta (HBB) gene of hamster (NCBI ID: XM_040757350.1) to target, as the average mass of this HBB gene predicted to be translated into protein of 15,841.2 Daltons (XP_040613284.1), which is in the mass range of Hb β-chains found in vertebrates. To knock out this hamster HBB gene, the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene targeting technique was employed. A single guide RNA (sgRNA) was designed to target exon 1 of the HBB gene using Benchling design tool (

Figure 1). After validating the indel-inducing efficiency of the sgRNA in baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) cells, a sgRNA/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex was assembled and micro-injected into 1-cell stage hamster embryos by pronuclear (PN) injection. The injected embryos were then transferred to Day 1 pseudo pregnant females. Among the 10 pups produced from PN injected embryos, three F0 hamsters were identified carrying indels by the PCR-RFLP genotyping assay. To investigate the nature of indels, PCR products amplified with primers flanking the indels were subjected to TA cloning and then sequenced. From the sequencing results, a 17 base pair (bp) deletion was detected and confirmed in one of the founder animals. As this 17 bp deletion causes a reading frameshift of the HBB gene and leads to multiple premature stop codons, therefore a KO genotype, it was bred with wild type (WT) hamsters to produce heterozygous (Htz) KO F1 animals. The F1 animals inherited the 17 bp mutation were then used for brother-sister crossing to produce homozygous (Hmz) KO animals. All animal studies detailed below were produced from this breeding colony. Both the Htz KO and Hmz KO hamsters were found to be viable, healthy and breed well.

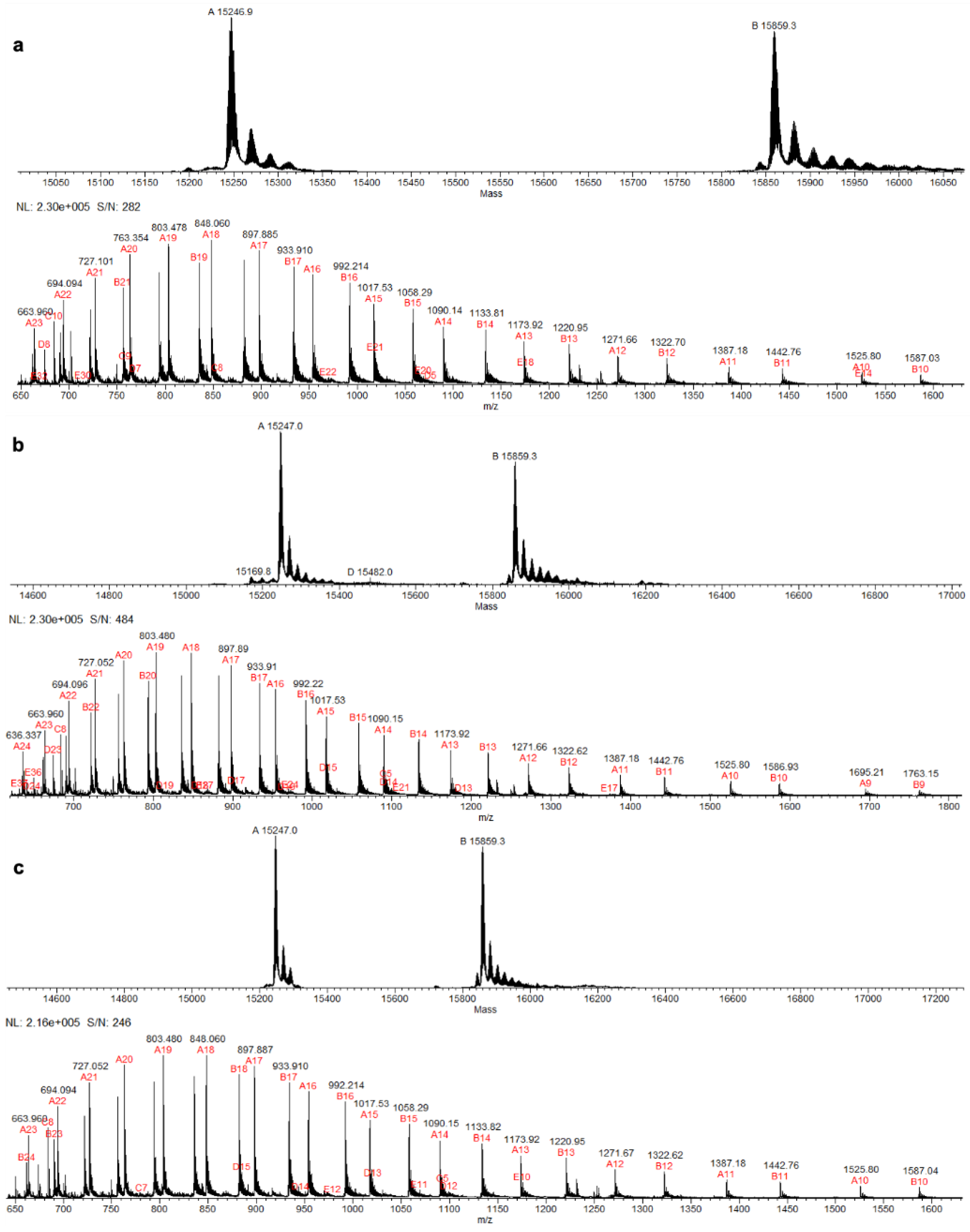

3.2. Mass Determination of Hb Chains in Hemolysates from WT and HBB KO Hamsters

ESI-MS was done on hemolysates prepared from the blood of WT, Htz KO, and Hmz KO hamsters to determine the molecular weight of the hemoglobin β-chain(s) that were present and the potential lack of Hb β-chain in Hmz KO hamsters (

Figure 2). As shown in

Table 1, the molecular weight of Hb β-chain in the hemolysates was 15,859 ± 0.2 Daltons, similar among WT, Htz KO or Hmz KO hamsters (

Table 1). This strongly suggested that the HBB gene that was knocked out was minimally translated to protein or not at all in the blood of hamsters. Therefore, we conducted a search in NCBI to identify if there was another hamster hemoglobin β-chain protein with a mass near 15,859 Daltons. The search resulted in identifying the hamster Hb β-chain protein, XP_040613281.1, which has an average mass of 15,860.2 Daltons (start methionine removed). This corresponds to a different HBB gene in the hamster: XM_040757347.1.

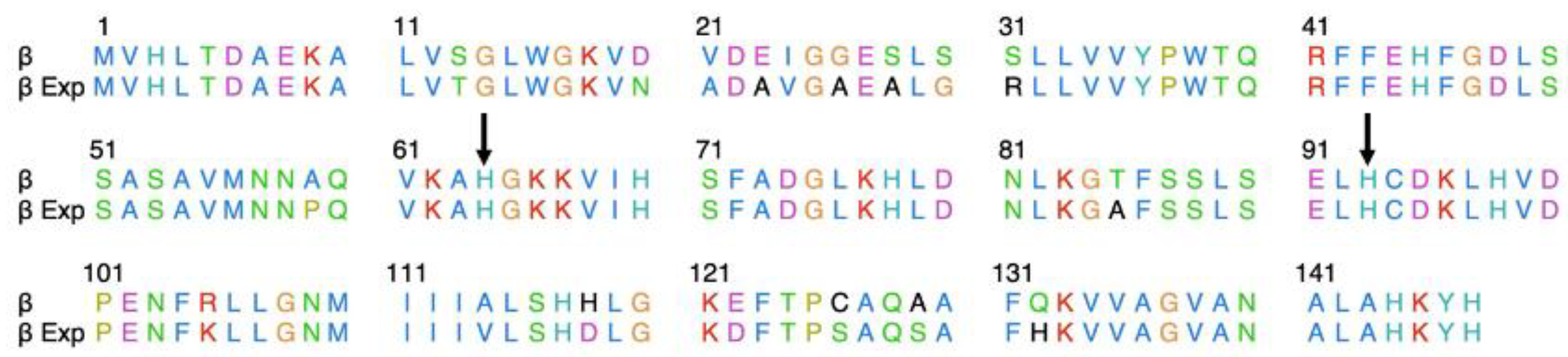

We then conducted sequence analysis by aligning the amino acid sequences for the Hb β-chain matching the mass in the hemolysates (XP_040613281.1) with that of the mass of the amino acid sequence for the

HBB gene that was knocked out (XP_040613284.1). As shown in

Figure 3, the sequences are 88% identical, with each sequence predicted to be 147 amino acids in length (

Figure 3).

It was noted from the ESI-MS analysis that there was a small peak of 15,843.5 Daltons relative to the large peak at 15,859 Daltons in the mass region of Hb β chains (

Table 1). This peak was observed in hemolysates from both WT and Hmz KO hamsters. This mass corresponded to a

HBB protein, XP_040613295.1, which has a mass of 15,844 Daltons when the start methionine is removed and is designated as hemoglobin subunit β-like in the Protein Data Bank (National Center for Biotechnological Information). This small peak observed in the deconvoluted ESI-MS spectra of the hemolysates may represent the hamster Hb βminor as described in the Discussion section.

The mass of the Hb α-chain was also determined in the hemolysates by ESI-MS of WT, Htz KO and Hmz KO hamsters. The mass was 15247.5 ± 0.5 Daltons whether WT, Htz KO or Hmz KO animals (

Table 1). This corresponded to the hamster Hb α-chain with an average mass of 15,248.3 Daltons and 141 amino acids in length (Accession: P01945.1).

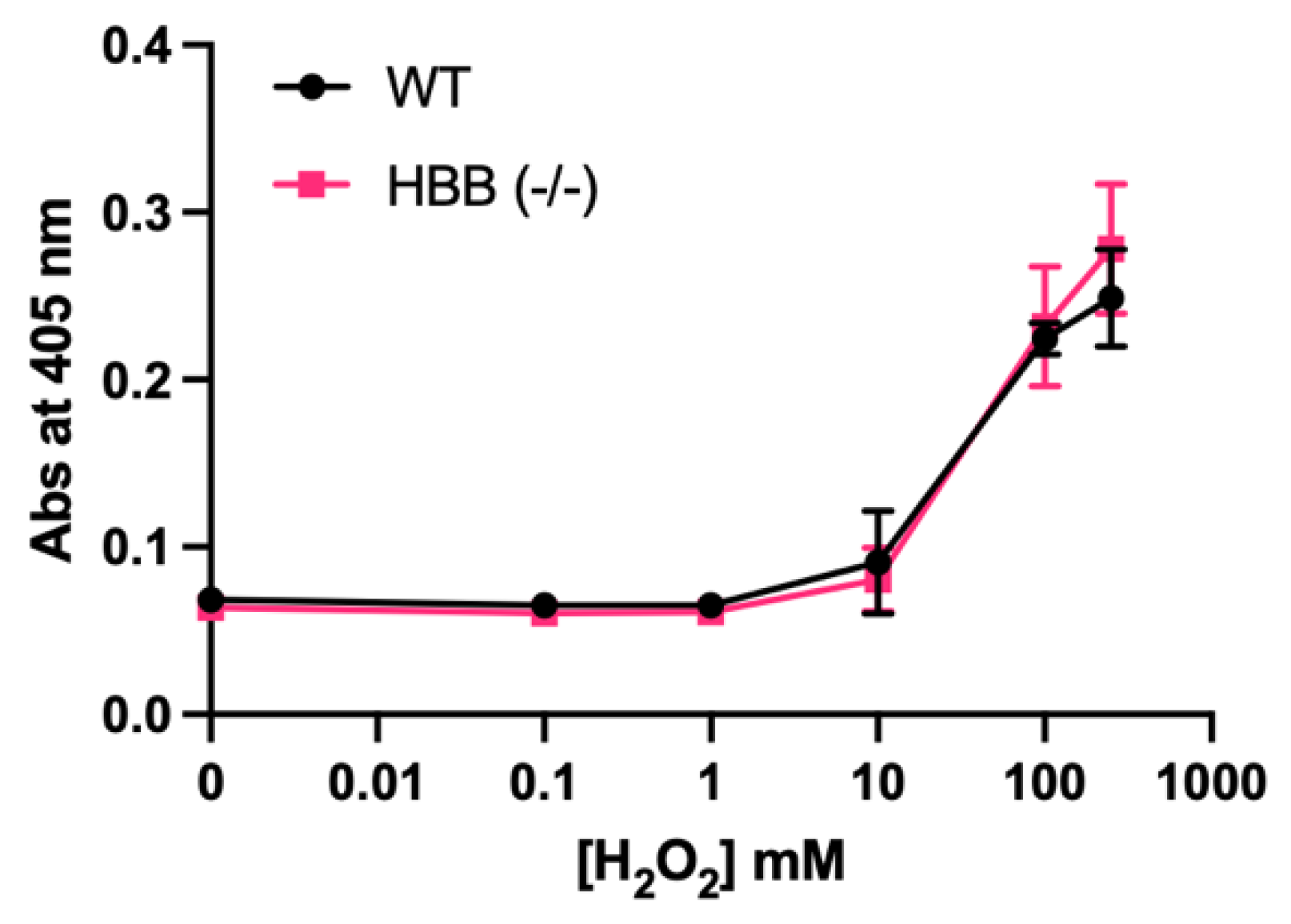

3.3. H2O2-Mediated Hemolysis of Erythrocytes in Whole Blood from WT and HBB Hmz KO Hamsters

To investigate the effect from knocking out the

HBB gene, XM_040757350.1, hydrogen peroxide-mediated hemolysis was evaluated in whole blood from WT and Hmz KO hamsters. Little hemolysis occurred at 0.1, 1 and 10 mM H

2O

2 in both WT and Hmz KO animals (

Figure 4). Hemolysis was extensive at 100 and 250 µM with no differences between WT and Hmz KO animals.

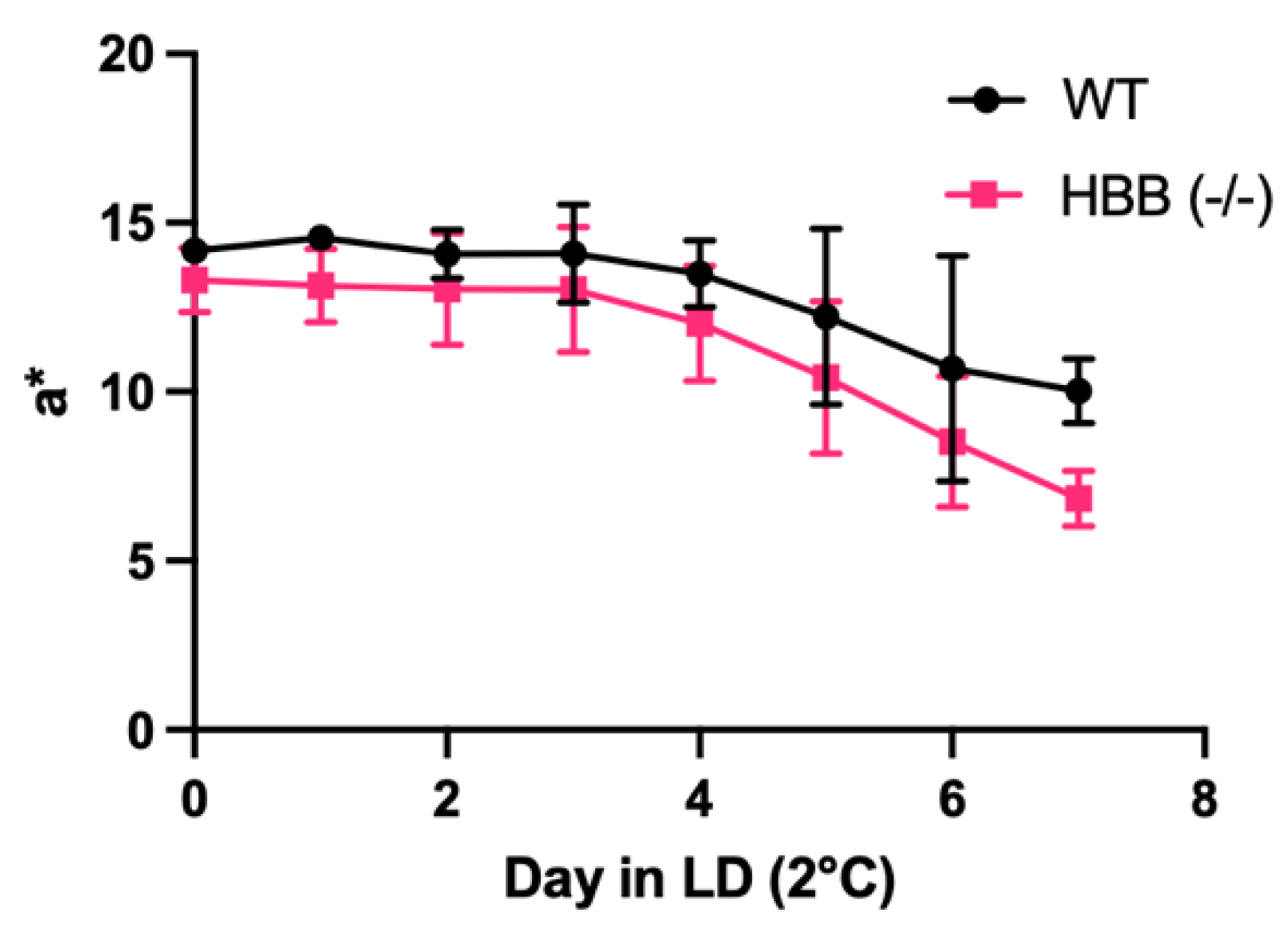

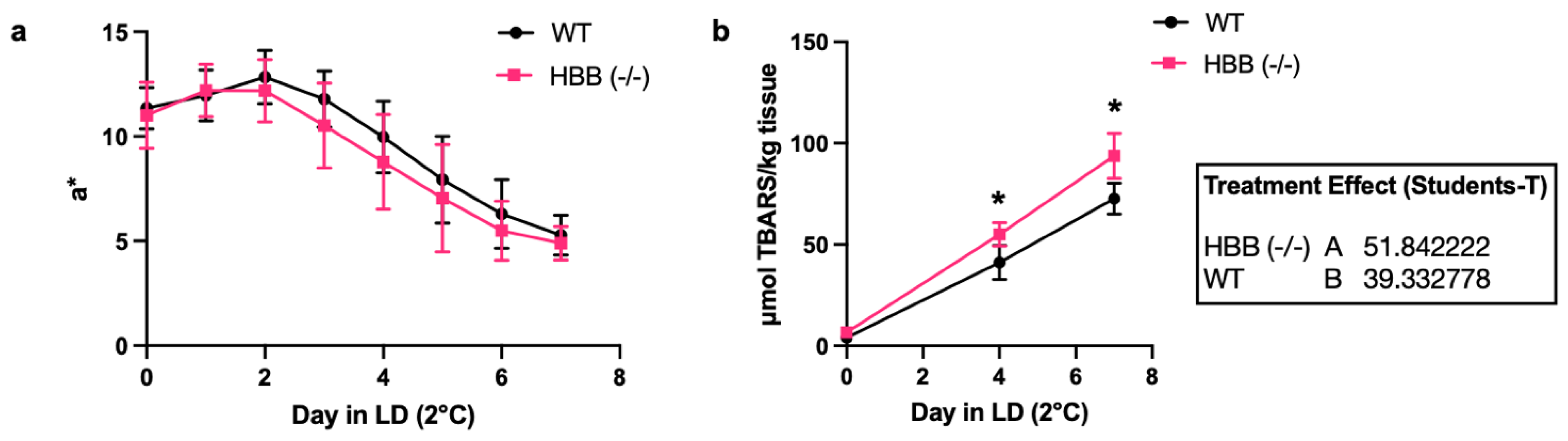

3.4. Discoloration and Lipid Oxidation During Storage of Leg Muscle from WT and HBB Hmz KO Hamsters

Oxidation of heme proteins in minced, leg muscle was assessed by changes in a-value that reflect redness. There was a trend (P = 0.15) in females that loss of redness was more rapid in Hmz KO compared to WT (

Figure 5). Additional hamsters were used to further evaluate the oxidation of heme proteins by measuring loss of redness and formation of lipid oxidation products during storage. Lipid oxidation was evaluated during 2°C storage of the ground, leg muscles from WT and Hmz KO female hamsters (n=6 per treatment). Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) were determined as the indicator of secondary lipid oxidation products. TBARS were significantly greater (P<0.05) in ground muscle from

HBB Hmz KO hamsters compared to that of WT hamsters at day 4 and day 7 of storage (

Figure 6). Loss of redness during storage of the post-mortem muscle was statistically similar in Hmz KO compared to WT (

Figure 6).

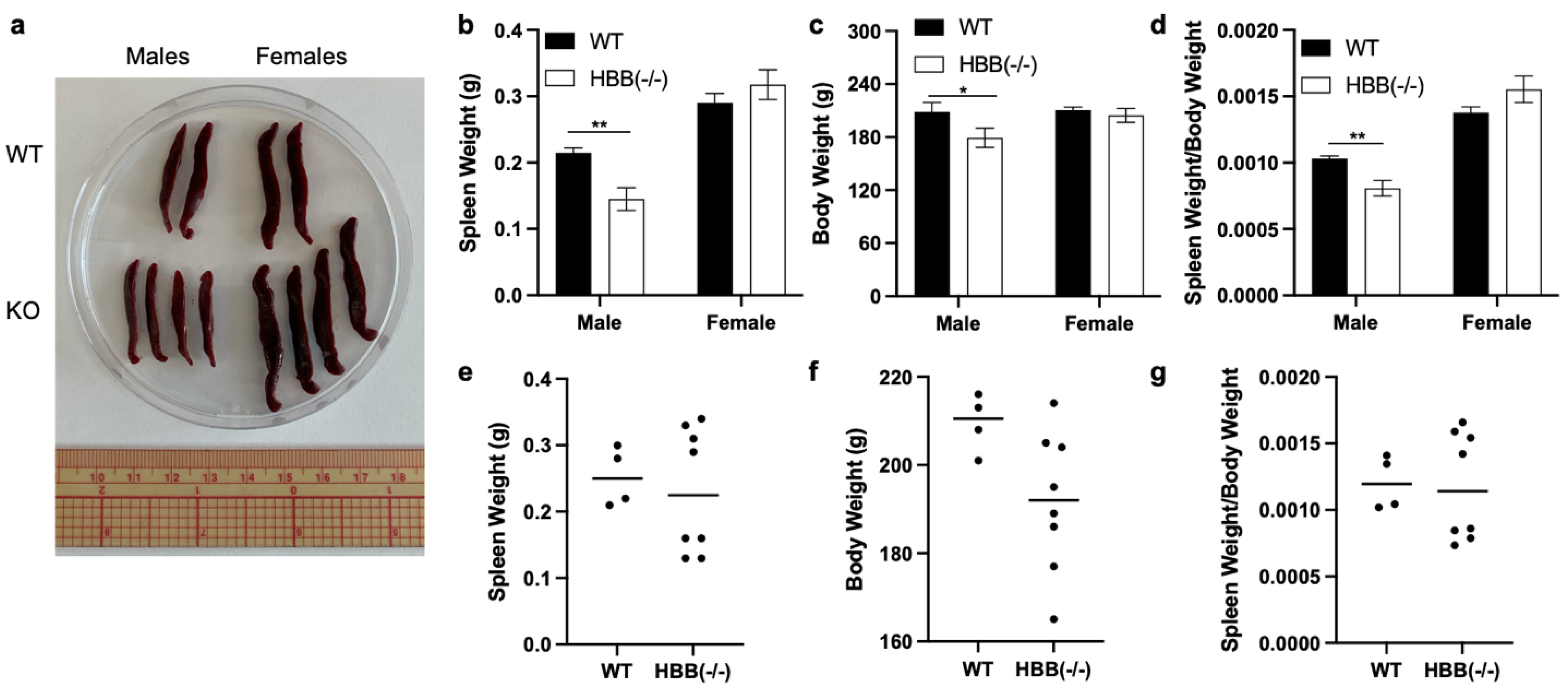

3.5. Spleen Size in WT and HBB Hmz KO Hamsters

Spleen size to body weight (SS:BW) ratio is a macro indicator of inflammation and oxidative stress, with reduced and in some cases increased SS:BW ratio indicating inflammatory and oxidative states [

14]. It was considered that the increased lipid oxidation based on TBARS in muscle of Hmz KO females may translate to altered SS:BW ratio. Therefore, we measured SS:BW ratio and found that it was similar between WT and Hmz KO in both males and females (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

An NCBI evaluation of hemoglobin beta (β) genes of Syrian hamster indicated that there are nine HBB genes designated as beta-y-like (1), beta-z-like (1), beta (2), and beta-like (5) (

Figure 8). We chose to knock out the HBB gene with the NCBI ID of XM_040757350.1 because this gene has a predicted protein mass of 15,841.2 Daltons (XP_040613284.1) that is in the mass range of Hb β-chains found in vertebrates. We were successful in knocking out the β gene and generated Htz KO and Hmz KO hamsters. Yet the KO of this gene had no effect on the major Hb β-chain protein that was observed in hemolysates prepared from blood of WT and KO hamsters (

Table 1). Thus, this gene is not the BetaMajor gene that we planned to knock out but is a different HBB gene that appears to be not translated to globin during Syrian hamster erythropoiesis. Interestingly, despite not translated, the inactivation of this HBB gene affected lipid oxidation in the stored muscle. We are in the process of investigating how this HBB gene exerts its function at the mRNA level. At the same time, our mass spectrometry analysis of hamster hemolysates definitively identified the BetaMajor gene, XM_040757347.1, that is translated to globin, XP_040613281.1, in Syrian hamster erythrocytes; this finding provides a definitive target to knock out the BetaMajor gene in future work to produce a hamster model of β-thalassemia.

It has been reported that adult golden Syrian hamsters (LVG strain) contained a hemoglobin βmajor and βminor isoform; upon protein electrophoresis, the minor isoform was barely visible relative to the dark density from the major isoform [

15]. ESI-MS is a relatively sensitive technique so that if there is even a small amount of a Betaminor, it should be detectable. We observed small amounts of protein in the hemolysate with a peak at 15,843 Da in WT, Htz KO, and Hmz KO hamsters that may represent the βminor in the hamster. The protein XP_040613295.1 is described as hemoglobin subunit beta-like in the hamster with a mass of 15,844 Daltons. Therefore, our study also demonstrated the usefulness of ESI-MS in quickly identifying and assigning each of the

HBB proteins to the predicted

HBB genes in the hamster. In this regard, we also posit that ESI-MS could have broader applications for identifying protein-coding genes and non-coding DNA sequences in organisms where genomic or transcriptomic annotation has not been fully established.

It was surprising that oxidative stress based on TBARS formation during storage of post-mortem muscle was greater in muscle from Hmz KO hamsters compared to WT hamsters. Knocking out a β gene that is not translated to protein would be expected to not affect onset of lipid oxidation in the muscle during storage. Yet, comparative proteomics of a wild-type and homozygous mutant line of Oryza sativa L. showed an altered level of 588 proteins, with 273 upregulated and 315 downregulated [

16]. An evaluation of proteomic changes in the tissues of the β XM_040757350.1 Hmz KO hamsters compared to WT hamsters may provide insight regarding the higher oxidative stress observed in muscle tissue of the Hmz KO females.

Increased hemolysis of erythrocytes was considered as a possible mechanism to explain the increased lipid oxidation observed in muscles from female Hmz KO compared to WT hamsters. Decreased hemolysis has been noted to decrease erythrocyte-mediated lipid oxidation in washed muscle [

17]. Hemoglobin that escapes the erythrocyte becomes diluted, dissociates to more oxidative subunits, and has more opportunity to oxidize surrounding lipids [

18]. Yet, H

2O

2-mediated hemolysis of anticoagulated whole blood was similar in WT compared to Hmz KO female hamsters. The ability of oxidants other than H

2O

2 to incur hemolysis should also be considered [

11]. Evaluating hemolysis in isolated erythrocytes may also yield alternative findings.

In conclusion, this work provides a validated strategy to inactivate HBB gene(s) from Syrian hamster to genetically interrogate their functions. In cases when multiple HBB genes exist, it is recommended to firstly evaluate the mass of Hb β-chain(s) in hemolysates to guide selection of the HBB gene to delete when seeking a model for β-thalassemia. This work also suggests that ‘silent’ HBB genes may limit oxidative stress in tissues by a mechanism that requires further elucidation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R. and Z.W.; methodology, J.G., J.W., S.B., R.L., N.R., Y.L. and Z.W.; formal analysis, J.W., S.B., R.L., and Y.L.; investigation, M.R. and Z.W.; resources, M.R. and Z.W.; data curation, J.W., S.B. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R. and Z.W.; writing—review and editing, M.R. and Z.W.; supervision, M.R. and Z.W.; project administration, M.R. and Z.W.; funding acquisition, M.R. and Z.W.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded upon work support by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture, Hatch/project 7000320 (to M.R.) and Utah Agriculture Experiment Station seed grants (to Z.W.).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Grzegorz Sabat of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotech Center for conducting ESI-mass spectrometry analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gao, S.; He, L.; Ding, Y.; Liu, G. Mechanisms Underlying Different Responses of Plasma Triglyceride to High-Fat Diets in Hamsters and Mice: Roles of Hepatic MTP and Triglyceride Secretion. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2010, 398, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Pathogenic Mechanisms in Thalassemia II. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America 2023, 37, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Ardehali, H.; Min, J.; Wang, F. The Molecular and Metabolic Landscape of Iron and Ferroptosis in Cardiovascular Disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2023, 20, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livrea, M.A.; Tesoriere, L.; Maggio, A.; D’Arpa, D.; Pintaudi, A.M.; Pedone, E. Oxidative Modification of Low-Density Lipoprotein and Atherogenetic Risk in Beta-Thalassemia. Blood 1998, 92, 3936–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altamentova, S.M.; Marva, E.; Shaklai, N. Oxidative Interaction of Unpaired Hemoglobin Chains with Lipids and Proteins: A Key for Modified Serum Lipoproteins in Thalassemia. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 1997, 345, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudrahem-Addour, N.; Izem-Meziane, M.; Bouguerra, K.; Nadjem, N.; Zidani, N.; Belhani, M.; Djerdjouri, B. Oxidative Status and Plasma Lipid Profile in β-Thalassemia Patients. Hemoglobin 2015, 39, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogarth, C.A.; Roy, A.; Ebert, D.L. Genomic Evidence for the Absence of a Functional Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Gene in Mice and Rats. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2003, 135, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Li, W.; Lee, S.R.; Meng, Q.; Shi, B.; Bunch, T.D.; White, K.L.; Kong, I.-K.; Wang, Z. Efficient Gene Targeting in Golden Syrian Hamsters by the CRISPR/Cas9 System. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Miao, J.; Tabaran, A.-F.; O’Sullivan, M.G.; Anderson, K.; Scott, P.; Wang, Z.; Cormier, R. A Novel Cancer Syndrome Caused by KCNQ1 -Deficiency in the Golden Syrian Hamster. J Carcinog 2018, 17, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyhn, U.E.H.; Fyhn, H.J.; Davis, B.J.; Powers, D.A.; Fink, W.L.; Garlick, R.L. Hemoglobin Heterogeneity in Amazonian Fishes. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology 1979, 62, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagsted, J.; Young, J.F. Large Differences in Erythrocyte Stability Between Species Reflect Different Antioxidative Defense Mechanisms. Free Radical Research 2002, 36, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kethavath, S.C.; Hwang, K.; Mickelson, M.A.; Campbell, R.E.; Richards, M.P.; Claus, J.R. Vascular Infusion with Concurrent Vascular Rinsing on Color, Tenderness, and Lipid Oxidation of Hog Meat. Meat Science 2021, 174, 108409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemon, D.W. An Improved TBA Test for Rancidity. In; New Series Circular; Canada, Fisheries and Marine Service, 1975; pp. 65–72.

- Ghosh, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Sarkar, P.; Sil, P.C. Ameliorative Role of Ferulic Acid against Diabetes Associated Oxidative Stress Induced Spleen Damage. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2018, 118, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussios, T.; Condon, M.R.; Bertles, J.F. Ontogeny of Hamster Hemoglobins in Yolk-Sac Erythroid Cells in Vivo and in Culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985, 82, 2794–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, G.; Usman, B.; Zhao, N.; Han, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. CRISPR/Cas9 Directed Mutagenesis of OsGA20ox2 in High Yielding Basmati Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Line and Comparative Proteome Profiling of Unveiled Changes Triggered by Mutations. IJMS 2020, 21, 6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, D.M.; Tatiyaborworntham, N.; Sifri, M.; Richards, M.P. Hemolysis, Tocopherol, and Lipid Oxidation in Erythrocytes and Muscle Tissue in Chickens, Ducks, and Turkeys. Poultry Science 2019, 98, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulow, L.; Alayash, A.I. Redox Chemistry of Hemoglobin-Associated Disorders. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2017, 26, 745–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Gene targeting golden Syrian hamster gene HBB by CRISPR/Cas9. (a) sgRNA design for HBB editing in golden Syrian Hamster and PCR-RFLP genotyping strategy. Schematic diagram of golden Syrian hamster HBB gene. sgRNA sequence (green) with PAM in red, on-target score from Benchling, and the position of PCR primers and restriction enzyme (underlined in blue) for the PCR-RFLP genotyping; (b) Genotyping results of 10 F0 generation pups by PCR-RFLP. #4, #7 & #9 animals showed resistant band “INDEL”; (c) INDEL was identified by TA cloning following Sanger sequence. 17 base pair deletion was detected and formed frameshifted translation.

Figure 1.

Gene targeting golden Syrian hamster gene HBB by CRISPR/Cas9. (a) sgRNA design for HBB editing in golden Syrian Hamster and PCR-RFLP genotyping strategy. Schematic diagram of golden Syrian hamster HBB gene. sgRNA sequence (green) with PAM in red, on-target score from Benchling, and the position of PCR primers and restriction enzyme (underlined in blue) for the PCR-RFLP genotyping; (b) Genotyping results of 10 F0 generation pups by PCR-RFLP. #4, #7 & #9 animals showed resistant band “INDEL”; (c) INDEL was identified by TA cloning following Sanger sequence. 17 base pair deletion was detected and formed frameshifted translation.

Figure 2.

ESI-MS spectra of α and β hemoglobin chains in hemolysates from (a) WT, (b) Htz KO, and (c) Hmz KO hamsters.

Figure 2.

ESI-MS spectra of α and β hemoglobin chains in hemolysates from (a) WT, (b) Htz KO, and (c) Hmz KO hamsters.

Figure 3.

Alignment of the β-chain. The alignment would result from translation of the HBB gene knocked out (β) to that of the β-chain that was predominately expressed in WT, Htz KO, and Hmz KO hamsters (β Εxp). Alignment produced no gaps, with an 88% sequence identity. Arrows indicate the distal (64) and proximal (93) histidine.

Figure 3.

Alignment of the β-chain. The alignment would result from translation of the HBB gene knocked out (β) to that of the β-chain that was predominately expressed in WT, Htz KO, and Hmz KO hamsters (β Εxp). Alignment produced no gaps, with an 88% sequence identity. Arrows indicate the distal (64) and proximal (93) histidine.

Figure 4.

H2O2-mediated hemolysis of anticoagulated blood from adult WT (n=2 male hamsters and 2 female hamsters) and HBB Hmz KO (n=4 male hamsters and 4 female hamsters).

Figure 4.

H2O2-mediated hemolysis of anticoagulated blood from adult WT (n=2 male hamsters and 2 female hamsters) and HBB Hmz KO (n=4 male hamsters and 4 female hamsters).

Figure 5.

Loss of redness based on a* value during storage at 2°C under light display (LD) of minced leg muscle from WT (n=2 female hamsters) and HBB Hmz KO (n=4 female hamsters).

Figure 5.

Loss of redness based on a* value during storage at 2°C under light display (LD) of minced leg muscle from WT (n=2 female hamsters) and HBB Hmz KO (n=4 female hamsters).

Figure 6.

Oxidative parameters of HBB Hmz KO female hamsters. (a) Loss of redness and (b) thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) values during storage at 2°C under light display of minced, leg muscle from WT (n=6 female hamsters) and HBB Hmz KO (n=6 female hamsters).

Figure 6.

Oxidative parameters of HBB Hmz KO female hamsters. (a) Loss of redness and (b) thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) values during storage at 2°C under light display of minced, leg muscle from WT (n=6 female hamsters) and HBB Hmz KO (n=6 female hamsters).

Figure 7.

Phenotypic characteristics of WT and HBB Hmz KO hamsters. (a) Images of spleen, (b/e) spleen weight, (c/f) body weight, (d/g) spleen weight to body weight (SS:BB) ratio in adult WT and HBB Hmz KO hamsters (female: WT n=6, KO n=6; male: WT n=5, KO n=5).

Figure 7.

Phenotypic characteristics of WT and HBB Hmz KO hamsters. (a) Images of spleen, (b/e) spleen weight, (c/f) body weight, (d/g) spleen weight to body weight (SS:BB) ratio in adult WT and HBB Hmz KO hamsters (female: WT n=6, KO n=6; male: WT n=5, KO n=5).

Figure 8.

Summary of the NCBI information of HBB locus. The red box is the locus we targeted HBB gene.

Figure 8.

Summary of the NCBI information of HBB locus. The red box is the locus we targeted HBB gene.

Table 1.

Mass of the α- and β-chains from wild-type, Htz HBB-KO, and Hmz HBB-KO hamster Hb determined by ESI-MS*.

Table 1.

Mass of the α- and β-chains from wild-type, Htz HBB-KO, and Hmz HBB-KO hamster Hb determined by ESI-MS*.

| Set 1 |

Hb (Da)

α-chain |

Hb (Da)

β-chain |

Set 2 |

Hb (Da)

α-chain |

Hb (Da)

β-chain |

| WT (female) |

15246.9 |

15859.3 |

WT (male) |

15247.9

15428.0 |

15859.3

15859.4 |

| WT (female) |

15246.9 |

15859.4 |

WT (female) |

15248.1

15247.9 |

15859.5

15859.3 |

| Htz KO (female) |

15246.9 |

15859.3 |

|

|

|

| Htz KO (female) |

15247.0 |

15859.3 |

|

|

|

| Hmz KO (female) |

15247.0 |

15859.4 |

Hmz KO (male) |

15248.3

15248.1

15247.9

15247.7 |

15859.7

15859.5

15859.3

15859.1 |

| Hmz KO (female) |

15247.0 |

15859.3 |

Hmz KO (female) |

15248.0

15246.8

15247.8

15247.6 |

15859.3

15859.2

15859.2

15859.0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).