Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

Study Participants and Recruitment

Survey Development and Data Collection

Data Analysis

3. Results

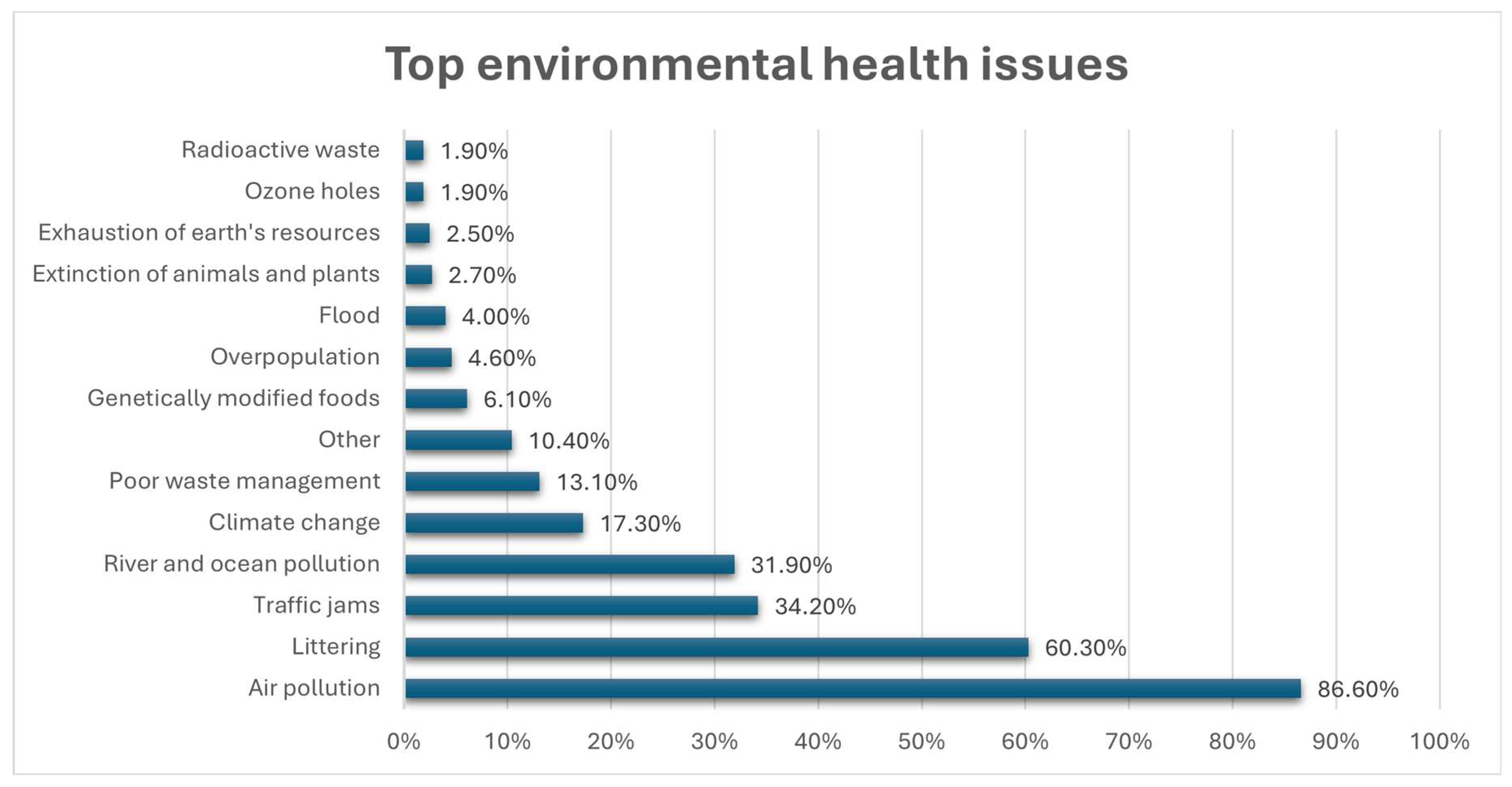

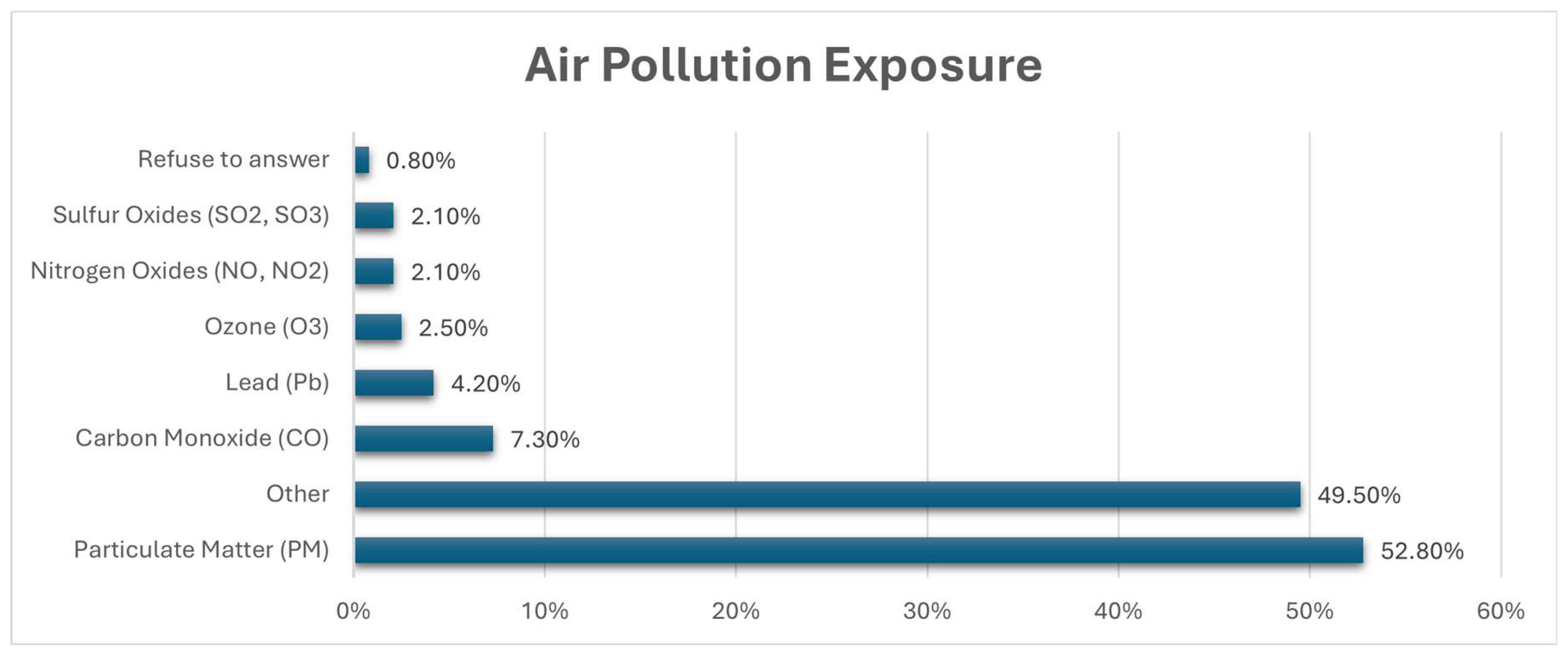

3.1. Environmental Health Issues and Exposure to Air Pollution

3.2. Knowledge of Air Pollution

3.3. Awareness of and Practices Regarding Air Pollution

3.4. Actions to Tackle Air Pollution

3.5. Impact of Sociodemographic Factors on Air Pollution Knowledge and Perception

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. More than 60 000 deaths in Viet Nam each year linked to air pollution. 2018.Available: Available online: https://www.who.int/vietnam/news/detail/02-05-2018-more-than-60-000-deaths-in-viet-nam-each-year-linked-to-air-pollution#:~:text=New data from the World Health Organization %28WHO%29,a basic requirement for human health and well-being.

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Viet Nam’s heavy air pollution needs stronger action. 2024.Available: https://www.undp.org/vietnam/blog/viet-nams-heavy-air-pollution-needs-stronger-action.

- Vo DH, Ho CM, Vo AT. Do Urbanization and Industrialization Deteriorate Environmental Quality? Empirical Evidence from Vietnam. Sage Open. 2024;14(2). [CrossRef]

- Dominutti PA, Mari X, Jaffrezo J-L, Dinh VTN, Chifflet S, Guigue C, et al. Disentangling fine particles (PM2.5) composition in Hanoi, Vietnam: Emission sources and oxidative potential. Sci Total Environ. 2024;923:171466. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Rodopoulou S, de Hoogh K, Strak M, Andersen ZJ, Atkinson R, et al. Long-Term Exposure to Fine Particle Elemental Components and Natural and Cause-Specific Mortality—a Pooled Analysis of Eight European Cohorts within the ELAPSE Project. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Hoek G. Long-term exposure to PM and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2020;143:105974. [CrossRef]

- Hien PD, Men NT, Tan PM, Hangartner M. Impact of urban expansion on the air pollution landscape: A case study of Hanoi, Vietnam. Sci Total Environ. 2020;702:134635. [CrossRef]

- Ly B-T, Matsumi Y, Nakayama T, Sakamoto Y, Kajii Y, Nghiem T-D. Characterizing PM2.5 in Hanoi with New High Temporal Resolution Sensor. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2018;18:2487–97. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2025. Air pollution in Viet Nam. Available: https://www.who.int/vietnam/health-topics/air-pollution.

- Phung D, Hien TT, Linh HN, Luong LMT, Morawska L, Chu C, et al. Air pollution and risk of respiratory and cardiovascular hospitalizations in the most populous city in Vietnam. Sci Total Environ. 2016;557–558:322–30. [CrossRef]

- Ward F, Lowther-Payne HJ, Halliday EC, Dooley K, Joseph N, Livesey R, et al. Engaging communities in addressing air quality: a scoping review. Environ Health. 2022;21:89. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Working together for equity and healthier populations: sustainable multisectoral collaboration based on health in all policies approaches. 2023. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240067530.

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Organizational Research Methods. 2018. Available: https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=44386156&site=ehost-live.

- Alahmadi NA, Alzahrani R, Bshnaq AG, Alkhathlan MA, Alyasi AA, Alahmadi AM, et al. General Public Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding the Impact of Air Pollution and Cardiopulmonary Diseases in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e48976. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shidi HK, Ambusaidi AK, Sulaiman H. Public awareness, perceptions and attitudes on air pollution and its health effects in Muscat, Oman. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 2021;71:1159–74. [CrossRef]

- Quintyne KI, Kelly C. Knowledge, attitudes, and perception of air pollution in Ireland. Public Heal Pract. 2023;6:100406. [CrossRef]

- Chin YSJ, De Pretto L, Thuppil V, Ashfold MJ. Public awareness and support for environmental protection-A focus on air pollution in peninsular Malaysia. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–21. [CrossRef]

- Odonkor ST, Mahami T. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions of Air Pollution in Accra, Ghana: A Critical Survey. J Environ Public Health. 2020;2020. [CrossRef]

- Kim SE, Harish SP, Kennedy R, Jin X, Urpelainen J. Environmental Degradation and Public Opinion: The Case of Air Pollution in Vietnam. J Environ Dev. 2020;29:196–222. [CrossRef]

- General Statistics Office of Vietnam. Statistical Yearbook of Vietnam 2023. Statistical Publishing House Hanoi, Vietnam; 2024.Available: https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/default/2024/07/statistical-yearbook-of-2023/.

- Cisneros R, Brown P, Cameron L, Gaab E, Gonzalez M, Ramondt S, et al. Understanding public views about air quality and air pollution sources in the San Joaquin Valley, California. J Environ Public Health. 2017;2017:4535142. [CrossRef]

- Pampel FC. The Varied Influence of SES on Environmental Concern. Soc Sci Q. 2014;95:57–75. [CrossRef]

- Manstead ASR. The psychology of social class: How socioeconomic status impacts thought, feelings, and behaviour. Br J Soc Psychol. 2018;57:267–91. [CrossRef]

- Unni B, Tang N, Cheng YM, Gan D, Aik J. Community knowledge, attitude and behaviour towards indoor air quality: A national cross-sectional study in Singapore. Environ Sci Policy. 2022;136:348–56. [CrossRef]

- Lin Y, Wijedasa LS, Chisholm RA. Singapore’s willingness to pay for mitigation of transboundary forest-fire haze from Indonesia. Environ Res Lett. 2017;12:24017. [CrossRef]

| Variable, No. (%)# | Response (n = 521) |

|---|---|

| Have you heard of air pollution? | |

| Yes | 512 (98.3%) |

| No | 9 (1.7%) |

| What do you know about air pollution? | |

| Natural phenomenon | 56 (10.7%) |

| Relevant to the environment | 169 (32.4%) |

| Not a big problem | 6 (1.2%) |

| Caused by air pollutants | 319 (61.2%) |

| Caused by animals | 25 (4.8%) |

| Caused by humans | 340 (65.3%) |

| Benefits the climate and/or environment | 6 (1.2%) |

| Damages the climate and/or environment | 165 (31.7%) |

| Has positive impacts on humans and other living beings | 10 (1.9%) |

| Has negative impacts on humans and other living beings | 329 (63.1%) |

| Other | 73 (14.0%) |

| Source of knowledge | |

| Government agency information | 37 (7.1%) |

| Local government internet | 53 (10.2%) |

| Social media | 359 (68.9%) |

| Television | 304 (58.3%) |

| Radio | 151 (29.0%) |

| Newspaper(s) | 254 (48.8%) |

| Specialised/academic magazine(s), school/college/university | 39 (7.5%) |

| Public library | 12 (2.3%) |

| Environmental group(s) | 19 (3.6%) |

| Energy provider | 3 (0.6%) |

| Friends/family | 50 (9.6%) |

| Other | 60 (11.5%) |

| How important is the issue of air pollution to you personally? | |

| Not important at all | 1 (0.2%) |

| Not very important | 6 (1.2%) |

| Important | 91 (17.5%) |

| Very important | 422 (81.0%) |

| Refuse to answer | 1 (0.2%) |

| Why is air pollution important to you?# | |

| Directly affects you personally (e.g., work, lifestyle) | 350 (67.2%) |

| Affects health | 489 (93.9%) |

| Affects daily activities | 302 (58.0%) |

| Affects personal well-being/mood | 230 (44.1%) |

| Affects animals | 166 (31.9%) |

| Affects the environment | 232 (44.5%) |

| Other | 18 (3.5%) |

| Variable, No. (%)# | Response (n = 521) |

|---|---|

| Causes of air pollution | |

| Many modes of transportation | 420 (80.6%) |

| Inefficient modes of transportation (motor vehicles) | 266 (51.1%) |

| Inefficient burning of fuel by households for cooking, lighting, and heating | 84 (16.1%) |

| Outdoor burning of fossil fuels | 60 (11.5%) |

| Industrial emissions | 405 (77.7%) |

| Indoor air pollution (use of toxic products: incense, cooking by wood) | 73 (14.0%) |

| Wildfires | 103 (19.8%) |

| Open burning of garbage waste | 293 (56.2%) |

| Construction and demolition work | 155 (29.8%) |

| Agriculture activities | 69 (13.2%) |

| Use of chemical and synthetic products | 83 (15.9%) |

| Other | 83 (15.9%) |

| Personal impact of air pollution | |

| Yes | 412 (79.1%) |

| No | 76 (14.6%) |

| Do not know | 33 (6.3%) |

| Refuse to answer | 0 (0.0%) |

| Impact on family/friends | |

| Yes | 408 (78.3%) |

| No | 73 (14.0%) |

| Do not know | 38 (7.3%) |

| Refuse to answer | 2 (0.4%) |

| Awareness of other effects of air pollution | |

| Yes | 354 (67.9%) |

| No | 63 (12.1%) |

| Do not know | 99 (19.0%) |

| Refuse to answer | 5 (1.0%) |

| Other effects of air pollution (if aware) | (n = 354) |

| Reduced agricultural production | 72 (20.3%) |

| Toxic to wildlife | 83 (23.4%) |

| Toxic to livestock/domesticated animals | 87 (24.6%) |

| Birth defects | 43 (12.1%) |

| Vulnerability to stresses | 118 (33.3%) |

| Vulnerability to diseases | 178 (50.3%) |

| Reduced quality of life | 237 (66.9%) |

| Affected by air pollution | |

| Infants/children under 5 years old | 429 (82.3%) |

| Children 5 years old and above | 362 (69.5%) |

| Adults (18 – 64 years old) | 238 (45.7%) |

| Adults over 65 years old | 403 (77.4%) |

| Outdoor workers | 346 (66.4%) |

| Indoor workers | 214 (41.1%) |

| Animals | 228 (43.8%) |

| Plants | 202 (38.8%) |

| Industrial Engines | 35 (6.7%) |

| Transportation | 31 (6.0%) |

| Other | 63 (12.1%) |

| Refuse to answer | 1 (0.2%) |

| Perception of air pollution's effects on yourself | |

| Yes | 506 (97.1%) |

| No | 6 (1.2%) |

| Do not know | 7 (1.3%) |

| Refuse to answer | 2 (0.4%) |

| Ways air pollution affects yourself | (n = 506) |

| Itchy eyes | 170 (33.6%) |

| Blurred vision | 133 (26.3%) |

| Respiratory infections | 279 (55.1%) |

| Emphysema | 67 (13.2%) |

| Asthma | 171 (33.8%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 89 (17.6%) |

| Heart disease | 41 (8.1%) |

| Lung cancer | 165 (32.6%) |

| Sinus infections | 259 (51.2%) |

| Allergies | 214 (42.3%) |

| Other | 91 (18.0%) |

| Variable, No. (%)# | Female (n = 281) | Male (n = 229) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you heard about air pollution? | |||

| Yes | 277 (98.6%) | 225 (98.3%) | 0.043 |

| No | 4 (1.4%) | 4 (1.7%) | |

| What do you know about air pollution? | |||

| Natural phenomenon | 27 (9.6%) | 27 (11.8%) | 0.218 |

| Relevant to the environment | 101 (35.9%) | 66 (28.8%) | 0.264 |

| Not a big problem | 5 (1.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.546 |

| Caused by air pollutants | 168 (59.8%) | 146 (63.8%) | 0.546 |

| Caused by animals | 14 (5.0%) | 11 (4.8%) | 0.902 |

| Caused by humans | 190 (67.6%) | 145 (63.3%) | 0.133 |

| Benefit to the climate and/or materials | 6 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.159 |

| Damage to the climate or to materials | 87 (31.0%) | 74 (32.3%) | 0.460 |

| Has positive impacts on humans and other beings | 7 (2.5%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0.764 |

| Has negative impacts on humans and other beings | 178 (63.3%) | 144 (62.9%) | 0.785 |

| Other | 32 (11.4%) | 39 (17.0%) | 0.111 |

| Source of knowledge | |||

| Government agency/information | 13 (4.6%) | 23 (10.0%) | 0.078 |

| Local government Internet | 23 (8.2%) | 29 (12.7%) | 0.306 |

| Social media | 196 (69.8%) | 157 (68.6%) | 0.268 |

| Television | 162 (57.7%) | 135 (58.9%) | 0.747 |

| Radio | 76 (27.0%) | 73 (31.9%) | 0.555 |

| Newspaper | 141 (50.2%) | 111 (48.5%) | 0.225 |

| Specialized/academic magazines, school/college/university | 19 (6.8%) | 19 (8.3%) | 0.563 |

| Public library | 8 (2.8%) | 4 (1.7%) | 0.815 |

| Environmental groups | 11 (3.9%) | 7 (3.1%) | 0.338 |

| Energy providers | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0.278 |

| Family/friends/ | 28 (10.0%) | 21 (9.2%) | 0.809 |

| Other | 34 (12.1%) | 25 (10.9%) | 0.806 |

| How important is the issue of air pollution to you personally? | |||

| Important | 44 (15.7%) | 46 (20.1%) | 0.963 |

| Very important | 231 (82.2%) | 181 (79.0%) | |

| Why is air pollution important to you? | |||

| Directly affects you personally | 189 (67.3%) | 152 (66.4%) | 0.473 |

| Affects health | 264 (94.0%) | 215 (93.9%) | 0.559 |

| Affects daily activities | 162 (57.7%) | 132 (57.6%) | 0.284 |

| Affects personal well-being/mood | 136 (48.4%) | 90 (39.3%) | 0.086 |

| Affects animals | 90 (32.0%) | 74 (32.3%) | 0.804 |

| Affects the environment | 128 (45.6%) | 100 (43.7%) | 0.911 |

| Other | 9 (3.2%) | 9 (3.9%) | 0.896 |

| Causes of air pollution | |||

| Many transportations | 232 (82.6%) | 177 (77.3%) | 0.176 |

| Inefficient modes of transportation | 146 (51.9%) | 114 (49.8%) | 0.940 |

| Inefficient burning of fuel in households | 43 (15.3%) | 39 (17.0%) | 0.953 |

| Burning of fossil fuels | 29 (10.3%) | 30 (13.1%) | 0.623 |

| Industrial emission | 224 (79.7%) | 173 (75.5%) | 0.515 |

| Indoor air pollution | 45 (16.0%) | 27 (11.8%) | 0.436 |

| Wildfires | 51 (18.1%) | 51 (22.3%) | 0.451 |

| Open burning of garbage waste | 168 (59.8%) | 118 (51.5%) | 0.192 |

| Construction and demolition works | 80 (28.5%) | 72 (31.4%) | 0.735 |

| Agriculture activities | 38 (13.5%) | 30 (13.1%) | 0.838 |

| Use of chemical and synthetic products | 47 (16.7%) | 34 (14.8%) | 0.451 |

| Other | 40 (14.2%) | 39 (17.0%) | 0.228 |

| Personal impact of air pollution | |||

| Yes | 231 (82.2%) | 172 (75.1%) | 0.075 |

| No | 40 (14.2%) | 36 (15.7%) | |

| Do not know | 10 (3.6%) | 21 (9.2%) | |

| Impact on family/friends | |||

| Yes | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.012 |

| No | 238 (84.7%) | 162 (70.7%) | |

| Do not know | 27 (9.6%) | 46 (20.1%) | |

| Awareness of other effects of air pollution | |||

| Yes | 192 (68.3%) | 153 (66.8%) | 0.980 |

| No | 33 (11.7%) | 29 (12.7%) | |

| Do not know | 52 (18.5%) | 46 (20.1%) | |

| Other effects of air pollution (if aware) | (n = 354) | ||

| Reduce agricultural production | 41 (14.6%) | 29 (12.7%) | 0.237 |

| Toxic to wildlife | 44 (15.7%) | 39 (17.0%) | 0.511 |

| Toxic to livestock/domesticated animals | 46 (16.4%) | 41 (17.9%) | 0.481 |

| Birth defects | 23 (8.2%) | 20 (8.7%) | 0.786 |

| Vulnerability to stresses | 71 (25.3%) | 47 (20.5%) | 0.178 |

| Vulnerability to diseases | 94 (33.5%) | 82 (35.8%) | 0.659 |

| Reduce the quality of life | 130 (46.3%) | 101 (44.1%) | 0.391 |

| Other | 48 (17.1%) | 39 (17.0%) | 0.135 |

| Perception of air pollution's effects on self | |||

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.795 |

| No | 277 (98.6%) | 218 (95.2%) | |

| Do not know | 3 (1.1%) | 3 (1.3%) | |

| Ways air pollution affects self | (n = 506) | ||

| Itchy eyes | 103 (36.7%) | 64 (27.9%) | 0.030 |

| Blurry vision | 78 (27.8%) | 51 (22.3%) | 0.008 |

| Respiratory infections | 170 (60.5%) | 103 (45.0%) | <0.001 |

| Emphysema | 41 (14.6%) | 25 (10.9%) | 0.451 |

| Asthma | 89 (31.7%) | 78 (34.1%) | 0.438 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 51 (18.1%) | 36 (15.7%) | 0.906 |

| Heart disease | 23 (8.2%) | 17 (7.4%) | 0.653 |

| Lung cancer | 94 (33.5%) | 68 (29.7%) | 0.657 |

| Sinus infections | 147 (52.3%) | 109 (47.6%) | 0.063 |

| Allergies | 134 (47.7%) | 77 (33.6%) | 0.002 |

| Other | 48 (17.1%) | 41 (17.9%) | 0.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).