1. Introduction

The World Dental Federation (FDI) describes oral health as multifaceted. It encompasses conditions of the oral structures and diseases, such as dental caries, periodontitis, and oral cancer. It also involves physiological functions associated with these structures, such as speaking, smiling, smelling, tasting, touching, chewing, and swallowing without pain or discomfort. Furthermore, it includes psychosocial functions, allowing individuals to express emotions through facial expressions with confidence and without embarrassment [

1]. Given this comprehensive understanding, oral health care should adopt a holistic approach that addresses both normative and subjective needs.

In Canada, while healthcare is publicly funded, dental care remains a personal responsibility for most Canadians, with the exception of medically necessary surgical-dental services delivered in publicly funded hospitals [

2]. Approximately 33% of Canadians lack any form of dental care coverage and pay fully out-of-pocket for services [

3]. Even among those who have dental care coverage, co-payments, which account for 20% to 50% of treatment costs, can deter individuals from seeking care [

4]. Furthermore, trends in cost barriers to dental care have risen over the past 15 years, negatively impacting oral health [

5]. Poor oral health is more common among individuals who lack access to regular dental care, underscoring the critical role of cost as a barrier [

6].

The inability to access oral health care is a determinant of poor oral health; however, it remains unclear whether continuous access to dental care without financial barriers improves and maintains oral health outcomes. To assess the impact of cost-free dental care on enhancing and sustaining individuals' oral health, the "One Smile Research" program, a single-arm, repeated measures clinical trial, was launched at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto. The primary eligibility criterion is a self-attested declaration of inability to access dental care within the last two years due to affordability issues. Additional eligibility requirements included residency in the City of Toronto or the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), a valid mailing address, English proficiency, and the ability to provide verbal and written informed consent. There is no age restriction in the study.

The research project, which received approval from the Research Ethics Board at the University of Toronto (Ethics Board #39888) and commenced in November 2021, was launched to advance the policy agenda for universal dental care coverage in Canada. As an action research initiative, the study seeks transformative change by simultaneously conducting research and taking action, using a holistic, multi-method approach to problem-solving [

7].

In addition to the quantitative analyses of participants, an optional qualitative component was added to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the barriers faced by the disadvantaged individuals. This component aimed to capture nuances not captured during the quantitative analysis alone, and to enhance the trustworthiness of findings through triangulation [

8]. A few in-depth interviews were conducted as part of this qualitative component. The mixed-methods case studies integrate clinical and self-reported data for quantitative analysis while capturing patient perceptions in the qualitative analysis. This research will enhance our understanding of the numerous impacts that providing cost-free dental care may have, equipping governments and policymakers with the knowledge needed to build the evidence base and advocate for universal dental coverage in Canada.

2. Case Presentation

Methods

This mixed methods case study is both intrinsic, seeking a deeper understanding of the specific case of interest, and illustrative, providing descriptive and in-depth examples to augment information about a program or policy [

9]. This case report features a 26-year-old patient who self-identified as a white male of European descent, born in Canada. At the time of recruitment, the participant was single, had never been married, was unemployed and held less than a high school diploma. In terms of living arrangements, he lived with one other person in a rented accommodation. Financially, the participant had no dental insurance and reported facing barriers to accessing dental care over the past two years. At baseline, the annual household income ranged between

$20,000 and

$30,000, while the participant's personal income was

$2,500.

The participant applied to the One Smile Research program in March 2022. Upon being deemed eligible, the participant provided verbal and written informed consent and completed a medical/dental history form, along with a self-administered survey at the first visit, for a baseline assessment (

Supplementary File 1). The survey, hosted on REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) at the University of Toronto, utilized closed-ended questions. REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed for research data capture. Self-reported oral health was assessed through a combination of global questions (oral health, oral pain, satisfaction with appearance, life stress) and validated questionnaires: psychosocial impact of oral health and treatment (measured by Psychosocial Impact of Dental Esthetic Questionnaire, PIDAQ) [

10], dental anxiety (measured by the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale, MDAS) [

11], self-esteem (measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, RSES) [

12], and social functioning (measured by the Social Functioning Scale, SFQ) [

13]. Details of these instruments can be reviewed through the included references.

Following the baseline survey, a dental hygienist conducted an initial oral assessment and took radiographs, which were then reviewed by the study dentist. The clinical examination was performed to assess several key aspects, including dentate status, oral function, masticatory ability, and dental treatment needs (e.g., preventive, endodontic, prosthetic). It also evaluates the presence of prostheses, type of occlusion, mucosal health, history of dental decay, and periodontal health. In collaboration with the participant, a dental treatment plan was developed. After completing the necessary treatment and achieving oral health stability (

Supplementary File 2), recall appointments were scheduled for 15 days, six months, and then annually at one and two years. These follow-ups included post-treatment self-administered surveys (

Supplementary File 3) and clinical assessments.

Qualitative data were collected through a one-time, 30-minute semi-structured interview conducted in person at the University of Toronto’s dental clinic. The interview guide was designed around three overarching domains of inquiry to understand patients’ experiences undergoing treatment under the One Smile Research program: access to care, quality of care, and the impact on overall well-being (

Supplementary File 4). The interview was recorded, de-identified, and transcribed verbatim using the Zoom platform. The generated transcripts were proofread and read multiple times to gain familiarity with the content and gain a broader understanding of the material. A generic form of descriptive analysis was conducted inductively and iteratively, employing a line-by-line semantic approach to coding, following Braun and Clarke’s guidelines for thematic analysis [

14]. This process involved continual reference to the primary data to enhance comprehension and ensure consistency in interpretations [

14,

15]. Initial codes, categories, and the refinement of themes were discussed at various stages among the research team to strengthen trustworthiness.

Baseline Exam

At baseline, as per the medical and dental history questionnaire, the patient reported no medication usage or allergies and no history of smoking or alcohol consumption. The patient indicated the presence of dental cavities at the time of enrollment. His oral hygiene practices included brushing 4-5 times a week with no reported flossing. Complaints of halitosis and bleeding during tooth brushing were noted. Additionally, the patient presented asymptomatic clicking on the left side of his jaw.

During the clinical assessment, the patient reported pain in the lower right quadrant and expressed anxiety about dental treatment. During the initial blood pressure assessment, the patient presented with high blood pressure at the first reading (150/98), followed by a decrease on a second reading (146/87). As systolic blood pressure was still high on the second reading, the patient was advised to follow up with his physician.

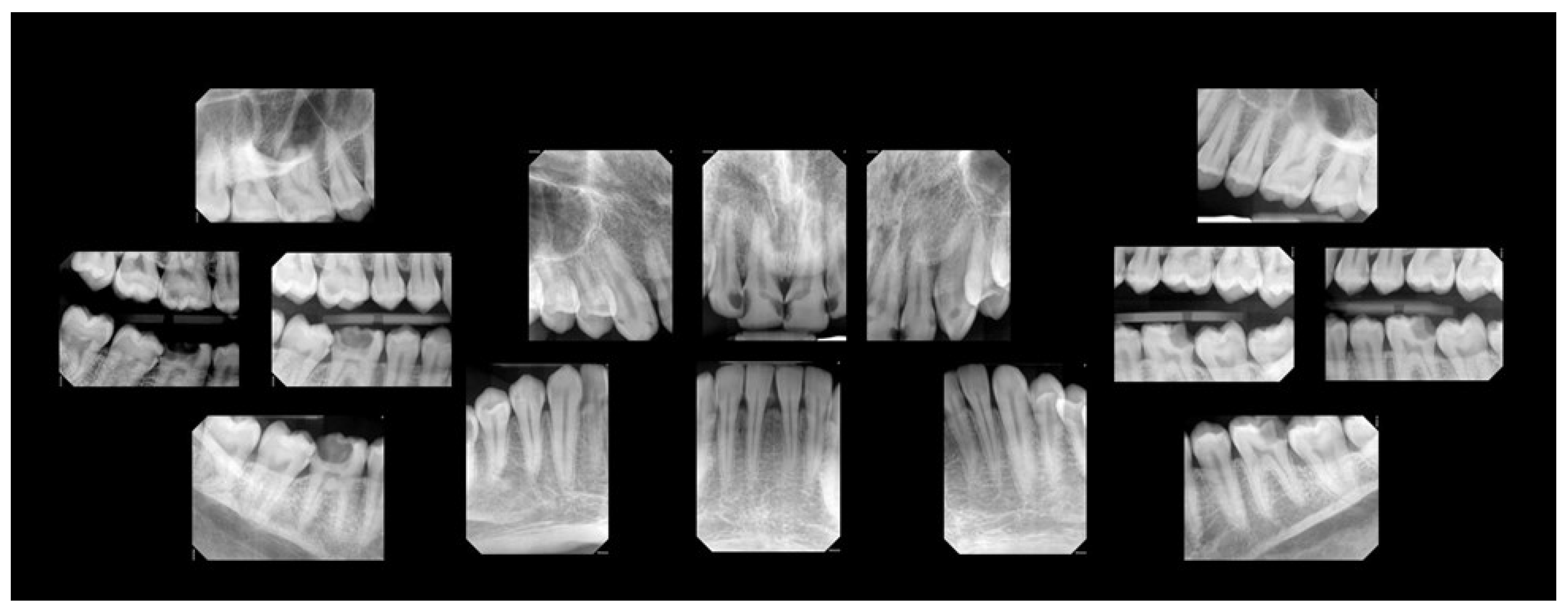

A comprehensive oral examination, including intraoral photographs and full-mouth radiographs (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), was conducted. The examination revealed that the patient had a full set of 32 teeth. Among these, 25 teeth exhibited active decay affecting single and/or multiple surfaces, six had incipient carious lesions, and one tooth was sound. Fractures were identified on the incisal surfaces of teeth numbered 41, 31, and 32. Furthermore, the distal-occlusal lingual wall of tooth 46 was found to be fractured, and tooth 28 exhibited extrusion.

Among the multiple teeth requiring restoration, teeth 36 and 47 exhibited deep caries. Testing with Endo Ice confirmed their vitality, showing a response within normal limits. The restorability of teeth 36 and 47 was deemed questionable at the time of examination due to the deep lesions. The patient was informed of a conservative treatment approach for these specific teeth, with the possibility of root canal treatment in the future. Generalized moderate sub-gingival and supra-gingival calculus was evident. Periodontal probing was within normal limits (less than 3.0 mm on average). Bleeding on probing was noted in 94% of the examined sites, calculated using the following formula: [number of bleeding sites / (number of teeth X 6 sites per tooth)].

Dental Treatment

Dental treatment began with oral prophylaxis, including full-mouth scaling, fluoride varnish application, and oral hygiene instructions. For restorative procedures, after excavating caries, no evident pulp exposure was identified. Over eight appointments, active carious lesions were restored with composite, with or without base and liner, under local anesthesia administered by the study dentist (

Figure 3). Incipient lesions were noted in the patient to be routinely monitored.

Ten days post-completion of the needed dental treatment, the patient reported discomfort while biting on the lower left side, specifically related to tooth 36. No sensitivity to cold was noted, and upon re-assessment, the bite appeared normal. The patient was advised to monitor the tooth as the restoration was deep. Afterwards, the patient achieved oral health stability as per the study criteria and transitioned into the follow-up stage.

At 15-day and 6-month follow-ups, periodontal probing was conducted, and the patient completed post-treatment questionnaires. At both the one-year and two-year follow-up appointments, radiographs were taken, a recall exam was performed, and full-mouth scaling was completed. At the one-year follow-up, the patient reported pain in quadrant four; root canal treatment was performed on tooth 46 at that time, which addressed the pain. By the two-year follow-up, the patient presented with progression of caries on the buccal surfaces of teeth 38 and 48, which were incipient at baseline.

While the average pocket depth at baseline was in the normal range, there was a slight decrease at both the one-year and two-year follow-ups. Additionally, bleeding on probing decreased substantially from 94% at baseline to 60% at the two-year follow-up.

Self-Reported Questionnaire

The patient’s self-reported oral health perception at baseline was poor; however, significant improvements were observed post-treatment at the 15-day and 6-month follow-ups, with the patient rating his oral health as “very good.” However, at the one-year follow-up (T3), the patient rated his oral health as "fair," likely due to pain and the need for root canal treatment. By the two-year follow-up (T4), the patient again reported his oral health as “very good. There was a marked enhancement in the satisfaction with his dental appearance, which transitioned from "very dissatisfied" before treatment to "satisfied/very satisfied" post-treatment, a positive change sustained through the two-year follow-up.

Regarding oral hygiene practices, the patient initially reported brushing once per day, which increased to twice per day at the 15-day follow-up and then reverted to once per day at the 6-month, 12-month and 2-year assessments. A noteworthy positive change occurred when the patient incorporated daily flossing into his routine after completing dental treatment, which he maintained for one year; however, he reverted to not flossing by the two-year follow-up.

Psychosocial aspects showed a substantial transformation, with the patient reporting feeling embarrassed because of his dental appearance "fairly often" before treatment and "never" afterwards, a feeling that persisted through the two-year follow-up. In addition, there was a significant decline in the PIDAQ score from 62 at baseline to 10 at the two-year follow-up, highlighting sustained improvements in psychosocial well-being even after 2 years post-treatment (

Table 1).

Self-esteem, as measured by the RSES, improved from 31 at baseline to 39 at the 15-day follow-up, stabilizing at 37 at the one-year and two-year follow-ups (

Table 1). Similarly, social functioning also showed improvement. According to the SFQ scale, the patient demonstrated good social functioning at baseline with an SFQ score of 5. Following dental treatment, this score improved to 2 at both the 15-day and six-month follow-ups, and to 3 at both the one-year and two-year follow-ups (

Table 1).

Dental anxiety, measured using the MDAS scale, decreased from 14 before treatment to 11 at both 15-day and six-month follow-ups, further dropping to 10 at one-year and 9 at two-year follow-ups (

Table 1). In general, before treatment, the patient reported being "slightly anxious or depressed," which changed to "not anxious or depressed" after one year of treatment; this improvement was sustained at the two-year follow-up. The patient reported increased confidence in meeting new people after receiving dental treatment, a change that persisted through the two-year follow-up. His self-perception about his general health also improved from "poor" before treatment to “very good” after treatment. Additionally, his employment status from being initially unemployed at the baseline changed to part-time employment at both the one-year and two-year follow-ups.

Qualitative Findings

The qualitative analysis yielded three main themes highlighting the patient’s perception of undergoing treatment at the One Smile Research program: ease of admission, kindness of the staff, and improvement in overall well-being.

Ease of Admission

After learning about the program through a family member, the participant reported searching for the dental program online and found no difficulty filling out the application. Although he considered the application process straightforward, with a simple roster of questions, he experienced a three-month delay between his initial attempt to register for the dental program and his actual enrollment.

Just went on Google. Searched up like U of T Green Shield Clinic, I think it was at first. Like went, selected the website and went in. I could not sign up at first because all the spaces were taken, but I had to wait, like three months I think, and then I signed up.

Kindness of the Staff

The participant describes the One Smile Research program providers as “knowledgeable,” “helpful,” and “calm.” It is noteworthy that the term “nice” is prevalent and recurrent in the data codes related to the quality of care rendered at the research program. The data suggests that this attribute is not only linked to a pleasant patient-provider interaction and a positive overall patient experience—diametrically opposed to his single experience previously with dental care abroad—but also connected to his ability to better understand and incorporate hygiene routine considered critical for maintaining stability in oral health, such as flossing. Moreover, his perception that “people are nice” may contribute to better acceptance among those seeking public dental services, as illustrated in the following excerpt:

Where I come from like in Europe, I guess, like the doctors are more rude. Like, I guess would be the term . . . People [providers] might say things, things that you haven't done [reprimanding the patient] and stuff like that. In my experience, this is just amazing cause the people [providers at OSP] are too nice . . . Oh, they were very helpful and nice, right? I mean, I learnt things that I did not know about, of course. Like flossing, for example. Like, [I] never even knew what that was until I got here [dental clinic] . . . [Patients in need of public dental care] like their incomes are lower. So, obviously, they feel better if I tell them what they get when they sign up and the people are nice, [and] stuff like that.

Improvement in Overall Well-Being

When discussing the impact of receiving dental care at the One Smile Research program, the participant believes that the benefits to his overall well-being significantly exceeded any potential “negatives” during or after treatment. Although he states at one point in the interview that “there are [were] no negatives,” he later recalls experiencing pain at the beginning of the treatment at the clinic. However, he reflects that this may be expected and a normal occurrence when starting dental treatments. While he reports experiencing “unbearable” pain before registering for the program and mentions that creating new, healthy habits were “positives” resulting from his treatment at the research program, the most significant impact on his well-being was, undoubtedly, gaining social confidence.

Like, the positives are, like way more, like, they outnumber [the negatives] . . . But no negatives I can think about really, but some pain, but I guess that’s normal, I guess, at first . . . Well, the thing I thought was actually [more beneficial is] being able to interact with people, not feeling inferior or insecure, I guess. It's like people have better teeth or perfect teeth, whatever the case may be. That’s the biggest thing for sure

At the end of the interview, the participant was also asked about his perspective on government dental programs, specifically who should be covered and what treatments should be included. His insights on how such publicly subsidized programs can better serve the population were very enriching. The participant believes that government programs should initially cover low-income individuals and those seeking refugee status in Canada. Additionally, he thinks that coverage should be incrementally extended to the middle-income population. Regarding the range of services covered, he believes that comprehensive basic services, such as root canal treatment, cleanings, fillings, and crowns, should be provided at no cost to these targeted populations. Furthermore, he argues that more specialized services, such as orthodontics, should also be included in a public dental program. Ultimately, he believes that incremental policy changes should lead to universal dental coverage and become an integral part of the Canadian healthcare system.

People coming from abroad, like war-torn places, for example, like asylum seekers, people below a certain amount of income, like $70,000 or $60,000, [should be granted public insurance] . . . I feel like the things should be covered should be like the very important things root canals, fillings, crowns . . . Like cleanings, I mean, sure if it's like possible but definitely the molar damaging things like fillings and RCTs and even braces . . . I mean the perfect place I feel like, is to be under the umbrella of health care system that everything should be free. But obviously, it will cycle slowly, it should be like the low-income people and, of course, the asylum seekers. Like I said, but in the perfect world, I feel like everyone should have access to it for sure, like other things that are a part of the health care system.

3. Discussion

This case study documents a patient's journey through the One Smile Research program, from enrollment to receiving necessary dental care and subsequent oral health follow-ups up to two years post-treatment. Overall, both clinical and self-reported outcomes indicate that providing cost-free dental care to individuals facing financial barriers can lead to significant and sustained improvements in their oral health, psychosocial well-being, and self-esteem over two years, at a minimum.

Qualitative analysis supports the positive effect on overall well-being, highlighting that social confidence gained because of the improvement of his oral and dental health was central to the program’s beneficial impact. Additionally, the analysis provided insights into the patient's perspective including the ease of enrollment, despite a three-month wait for registration, as well as the high quality of care received, particularly highlighting the perceived kindness and chair-side manners of the staff.

While the participant believes that the providers’ pleasant approach to dental care fostered greater adherence to and awareness of oral hygiene habits—improvements that were evident after treatment—proved to be ephemerous. Both quantitative and qualitative findings indicate better flossing habits up to one year post-treatment; however, subsequent self-reported follow-up data revealed that the patient stopped flossing daily after that point. Similarly, improved brushing habits were sustained for a maximum 6 months according to the follow-up questionnaires. These findings align with broader studies showing that education and knowledge alone do not lead to sustained behaviour change [

16]. Importantly, it underscores the value of a top-down approach from the government to continue facilitating access to care, as relying solely on individuals to manage their own health and hygiene may not be sufficient. Notably, participation in the One Smile Research Program arguably influenced the patient’s employment status; initially unemployed, the patient reported part-time employment at both the one-year and two-year follow-ups.

Viewing the quality of care through the lens of the patient’s experience, he reported receiving high-quality treatment. The dental program aligned with the Institute of Medicine's definition [

17], prioritizing "safety" by delivering services through a qualified licensed dentist in accordance with the Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario guidelines [

18]. The program's "effectiveness" was evident in the successful dental treatments provided and ongoing monitoring for positive outcomes. "Patient-centered" care was emphasized through clear communication and the establishment of a treatment plan tailored to the patient's needs. "Timely" access to dental services addressed long-standing issues, allowing participants to return for emergency treatment even outside the pre-determined follow-up visits, showcasing "efficiency." The program's commitment to "equity" was reflected in its availability to everyone, regardless of race, ethnicity, or religion.

This case study is limited in its evidentiary scope, as it includes only one subject; however, it offers unique insights through an in-depth exploration of the patient’s experiences with the care received and its impact on him. Additionally, this study seeks to understand the patient’s perspective on the coverage of dental care through public programs, which is often evaluated primarily by subject matter experts, administrators, and politicians. The participant’s insights on how publicly funded programs can better serve the population were very valuable. He believes that the government should cover all dental services, including orthodontics, implemented in a staggered approach: starting with low-income individuals, then expanding to middle-income groups, and gradually including everyone. Notably, he expressed the opinion that Canada should ideally have universal dental coverage as part of its healthcare system.

Despite Canada’s universal healthcare, dental care is predominantly privately funded, with only 6% publicly financed [

19]. Current government dental programs, administered through provinces and territories, vary significantly and provide limited coverage, typically restricted to emergency and basic services, and are available only to specific groups, such as children from low-income families, individuals with disabilities, social assistance recipients, and low-income seniors [

20]. The new Canadian Dental Care Plan, an income-tested program administered by Health Canada, was recently launched in May 2024 in a phased approach, initially covering seniors, children, and people with disabilities, followed by all individuals from households earning less than

$90,000 [

21] This program is expected to cover approximately nine million eligible Canadians when fully implemented. However, those with private insurance are deemed ineligible for the program; for low- and middle-income people, out-of-pocket co-payments create a financial burden, making access to dental care dependent more on cost than on need, which inadvertently exacerbates the inverse care law in Canada [

22,

23,

24]. Results of this study will hopefully highlight the importance of continuity of cost-free dental care and may provide insights to the government on why it is important not to have any co-payments for the CDCP clients.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report in dentistry addressing both clinical outcomes and patient perceptions of cost-free dental care, emphasizing the uniqueness of the participant's experience. While it is essential to acknowledge that these results are specific to one patient, they represent a substantial proportion of Canadians who experience poor oral health and are unable to access dental care due to affordability issues.

5. Conclusions

The One Smile Research program, a cost-free dental care initiative that provides continuity of care without financial barriers, not only addresses immediate dental needs but also significantly impacts the participant’s sustained oral health, self-esteem, and overall well-being. This case study highlights the need for universal dental care coverage within the framework of Medicare.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, File S1: Baseline survey for adults (17+ years old), File S2: Criteria to determine oral health stability for the One Smile Research Program. File S3: Follow-up survey for adults (17+ years old), File S4: Qualitative interview.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MA, ZH, CM, IP, KK, AA and SS; methodology, MA, ZH, CM, IP, KK, AA and SS; data collection, MA, ZH, CM, IP, KK, AA and SS; formal analysis, MA, ZH, CM, IP, KK, AA and SS; writing—original draft preparation, MA, ZH, CM, IP, KK, AA and SS; writing—review and editing, MA, ZH, CM, IP, KK, AA and SS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge the generous support of Green Shield Canada for establishing and running the One Smile Research program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of Toronto (Ethics Board #39888, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the participant involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders have no say in data collection, analysis and results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PIDAQ |

Psychosocial Impact of Dental Aesthetic Questionnaire |

| MDAS |

Modified Dental Anxiety Scale |

| RSES |

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

| SFQ |

Social Functioning Questionnaire |

References

- World Dental Federation. FDI’s definition of oral health. At: https://www.fdiworlddental.org/fdis-definition-oral-health.

- Canada Health Act, RSC 1985, c C-6. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-6/page-1.html.

- Quiñonez, C. The Politics of Dental Care in Canada. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars; 2021 Aug.

- The Canadian Dental Association. Understanding Co-payment. At: https://www.cda-adc.ca/en/oral_health/talk/copayment.asp.

- Abdelrehim M, Ravaghi V, Quiñonez C, Singhal S. Trends in self-reported cost barriers to dental care in Ontario. Plos one. 2023 Jul 7;18(7):e0280370. [CrossRef]

- Thomson WM, Williams SM, Broadbent JM, Poulton R, Locker D. Long-term dental visiting patterns and adult oral health. Journal of Dental Research. 2010 Mar;89(3):307–11.

- Koshy V. Action research for improving practice: A practical guide. Sage; 2005 May 19.

- Onghena P, Maes B, Heyvaert M. Mixed methods single case research: State of the art and future directions. Journal of mixed methods research. 2019 Oct;13(4):461-80.

- Baskarada, S. Qualitative case study guidelines. Baškarada, S. Qualitative case studies guidelines. The Qualitative Report. 2014 Oct 19;19(40):1-25.

- Klages U, Claus N, Wehrbein H, Zentner A. Development of a questionnaire for assessment of the psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics in young adults. Eur J Orthod. 2006 Apr 1;28(2):103–11. [CrossRef]

- Newton JT, Edwards JC. Psychometric properties of the modified dental anxiety scale: an independent replication. Community Dent Health. 2005 Mar;22(1):40–2.

- Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). At: https://www.apa.org/obesity-guideline/rosenberg-self-esteem.pdf.

- Tyrer P, Nur U, Crawford M, Karlsen S, McLean C, Rao B, et al. The Social Functioning Questionnaire: a rapid and robust measure of perceived functioning. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2005 Sep;51(3):265–75.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. 2006 Jan 1;3(2):77-101.

- Kelly, M. The role of theory in qualitative health research. Family practice. 2010 Jun 1;27(3):285-90.

- Arlinghaus KR, Johnston CA. Advocating for behavior change with education. American journal of lifestyle medicine. 2018 Mar;12(2):113-6.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2001.

- Royal College of Dental Surgeon of Ontario. Standards, guidelines and resources. At: https://www.rcdso.org/standards-guidelines-resources.

- The Canadian Institute for health Information. National Health Expenditure Trends, 2020: Data Tables-Series A.

- Farmer J, Singhal S, Ghoneim A, Proaño D, Moharrami M, Kaura K, McIntyre J, Quiñonez C. Environmental scan of publicly financed dental care in Canada: 2022 update. Toronto, ON: Dental Public Health, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto. Available from: https://caphd.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Canada-Dental-environmentscan-UofT-20221017.pdf.

- Government of Canada. Canadian dental care plan. At: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/dental/dental-care-plan.html?utm_campaign=hc-sc-canadian-dental-care-plan-24-25&utm_source=ggl&utm_medium=sem&utm_content=ad-text-en&adv=611850&utm_term=canada+dental+coverage&gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAjwvKi4BhABEiwAH2gcw6ReOk8pauoW4Golf9Gkr16tiBBEYmzq6FaV8FDZUnxMlTsgl7gmQhoCLVEQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds.

- Ramraj C, Quiñonez CR. Self-reported cost-prohibitive dental care needs among Canadians. Int J Dent Hyg. 2013 May;11(2):115–20.

- Abdelrehim M, Singhal S. Is private insurance enough to address barriers to accessing dental care? Findings from a Canadian population-based study. BMC Oral Health. 2024 Apr 29;24(1):503.

- Dehmoobadsharifabadi A, Singhal S, Quiñonez C. Investigating the “inverse care law” in dental care: A comparative analysis of Canadian jurisdictions. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2016;107(6):e538–44. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).