Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

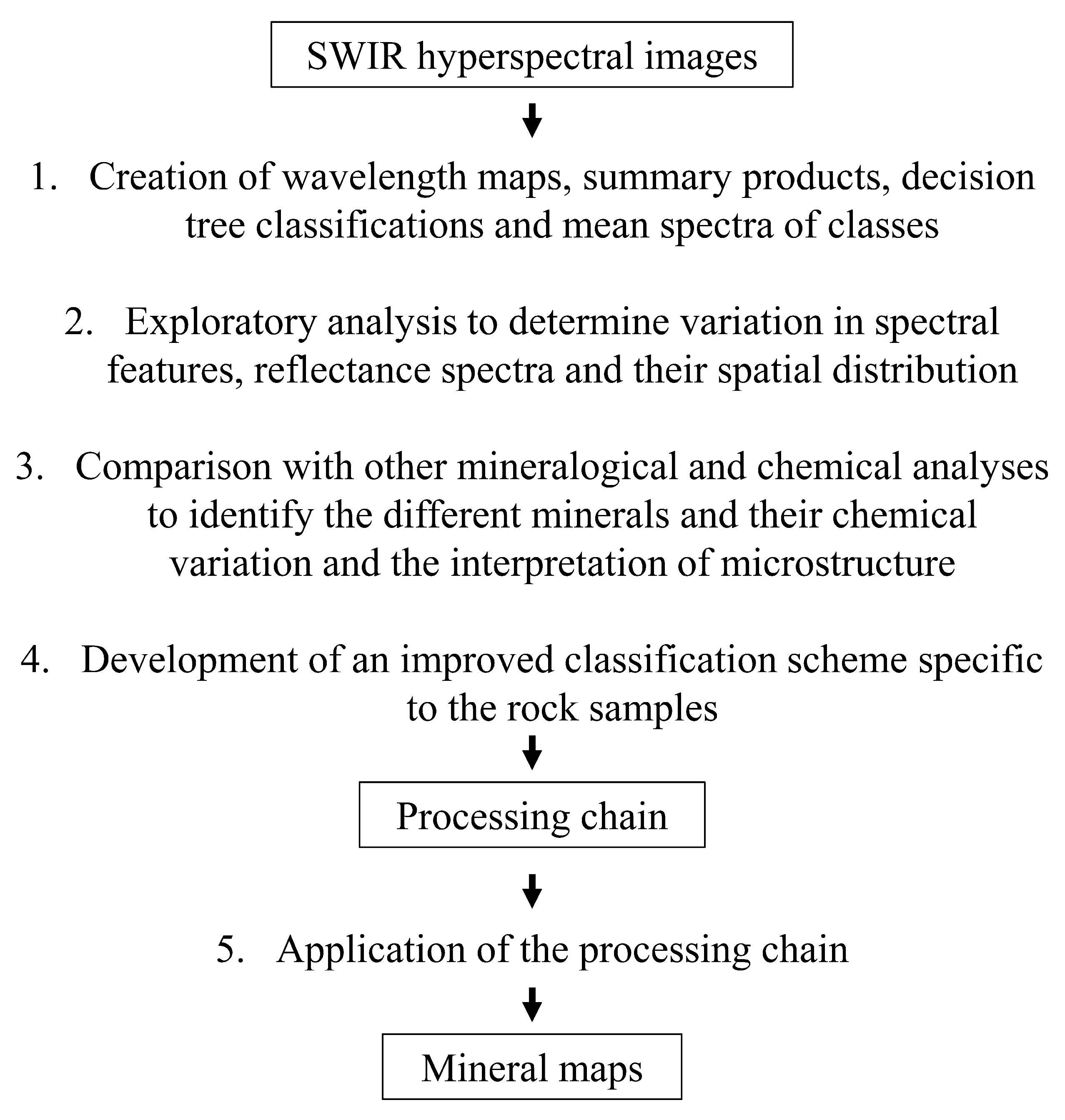

2.1. Interpretation Strategy

2.2. Image Acquisition and Preprocessing

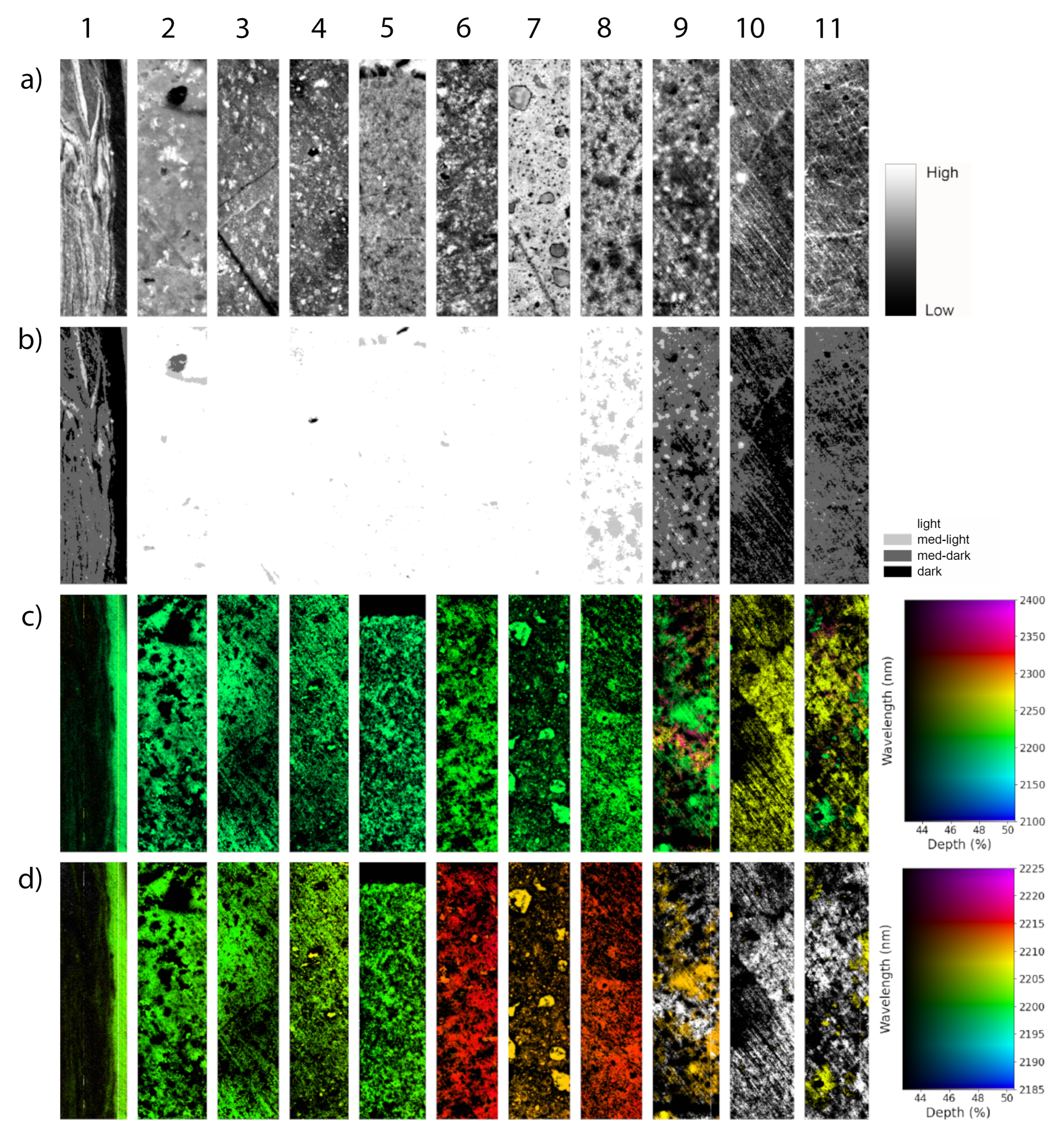

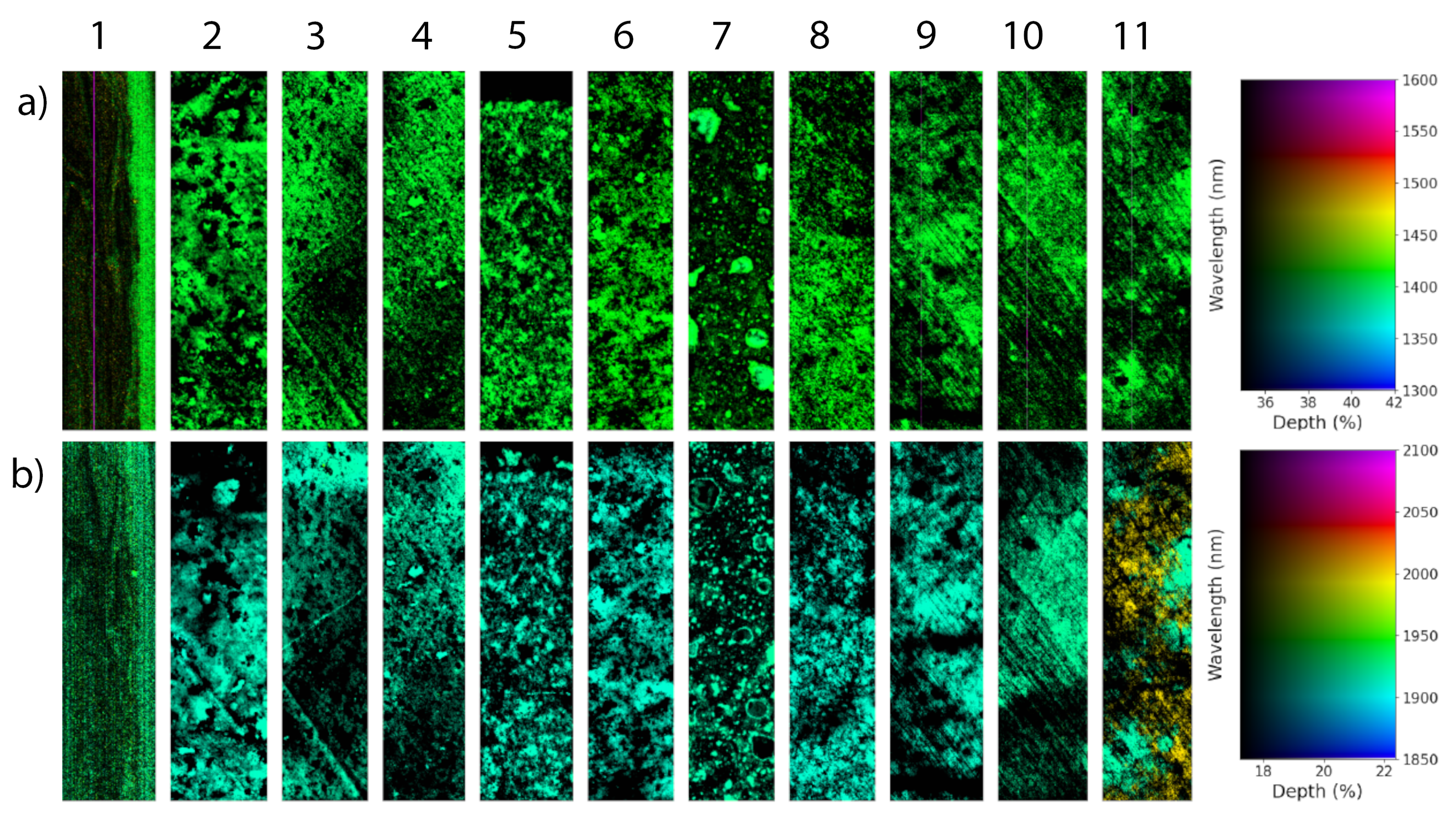

2.3. Wavelength Mapping

2.4. Summary products

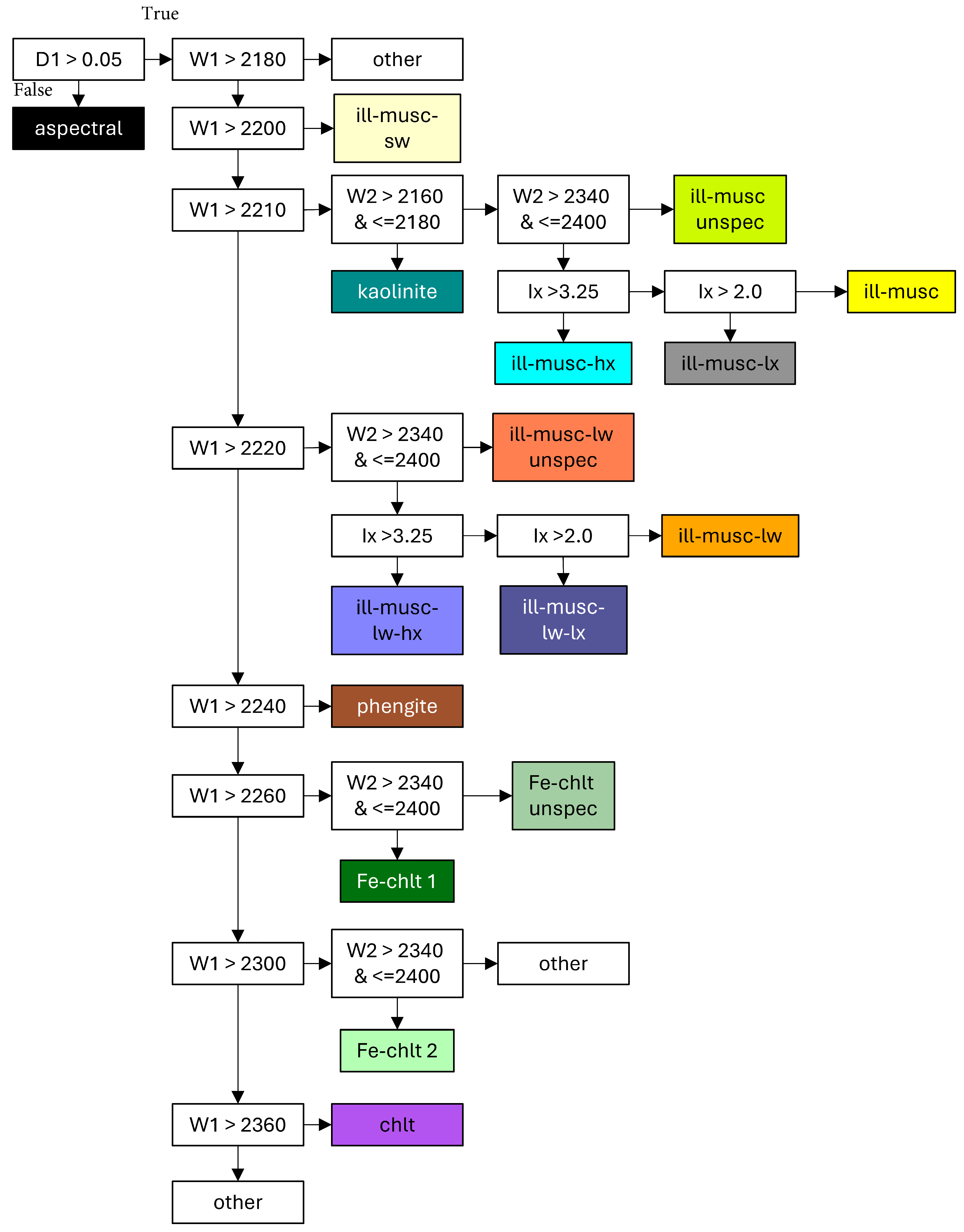

2.5. Decision trees

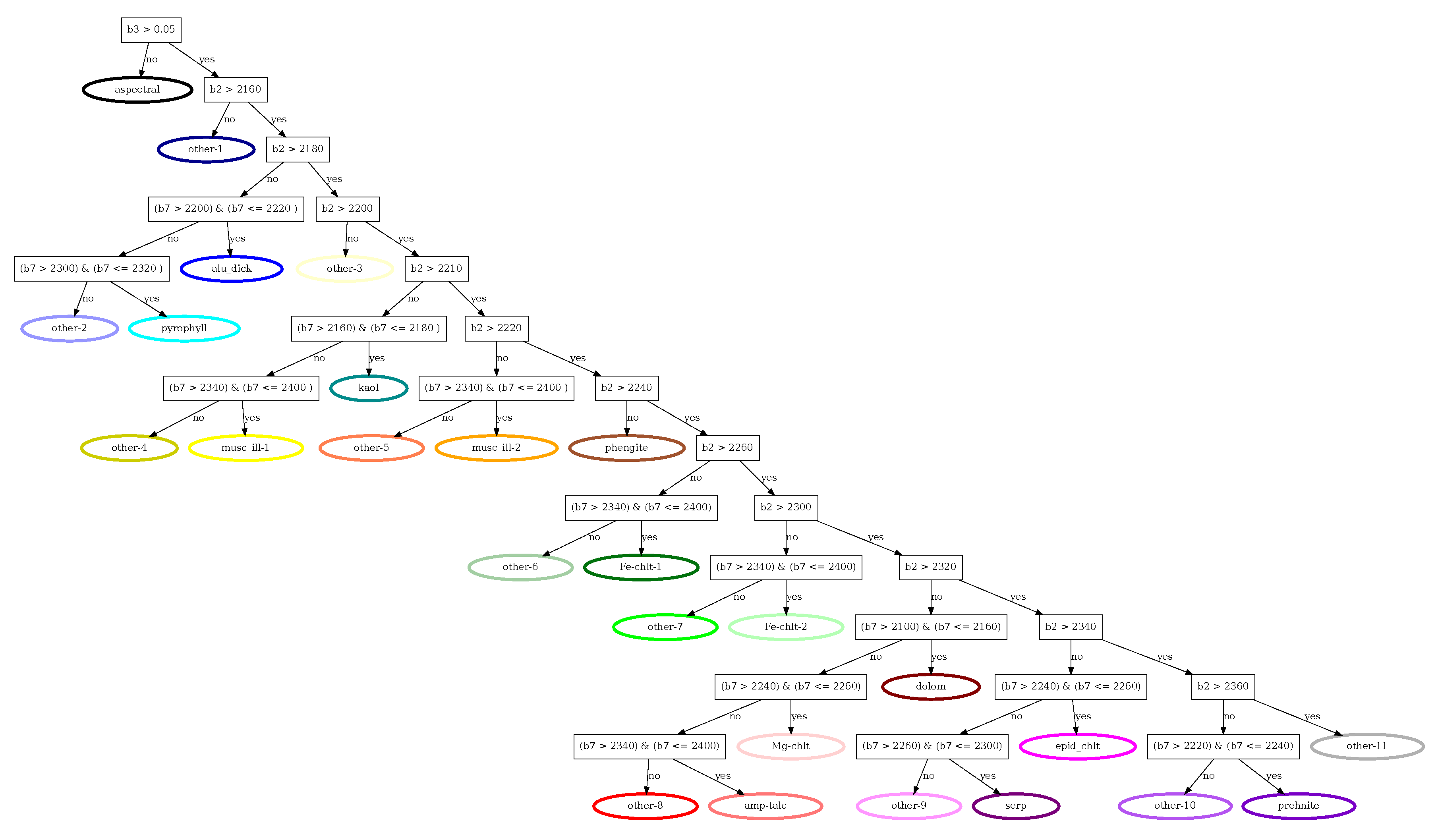

| Decision tree | Resulting classified image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| wave2100-2400_class | Classification based on depth of deepest and wavelength positions of first and second deepest absorption features in wavelength image between 2100 and 2400 nm (see Figure A2). | |

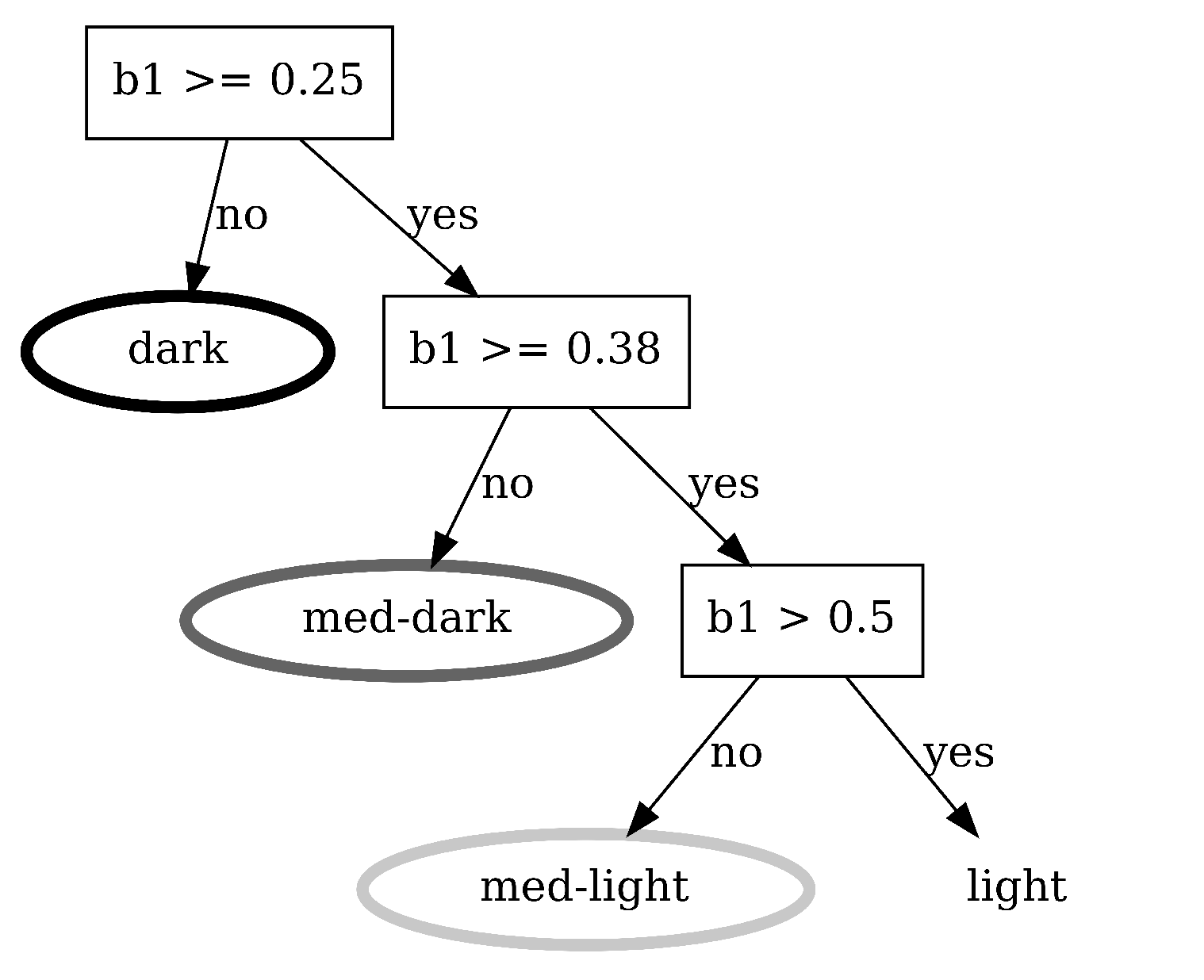

| albedo_class | Slicing of albedo image at thresholds: 0.25, 0.38 and 0.50 (see Figure A3). | |

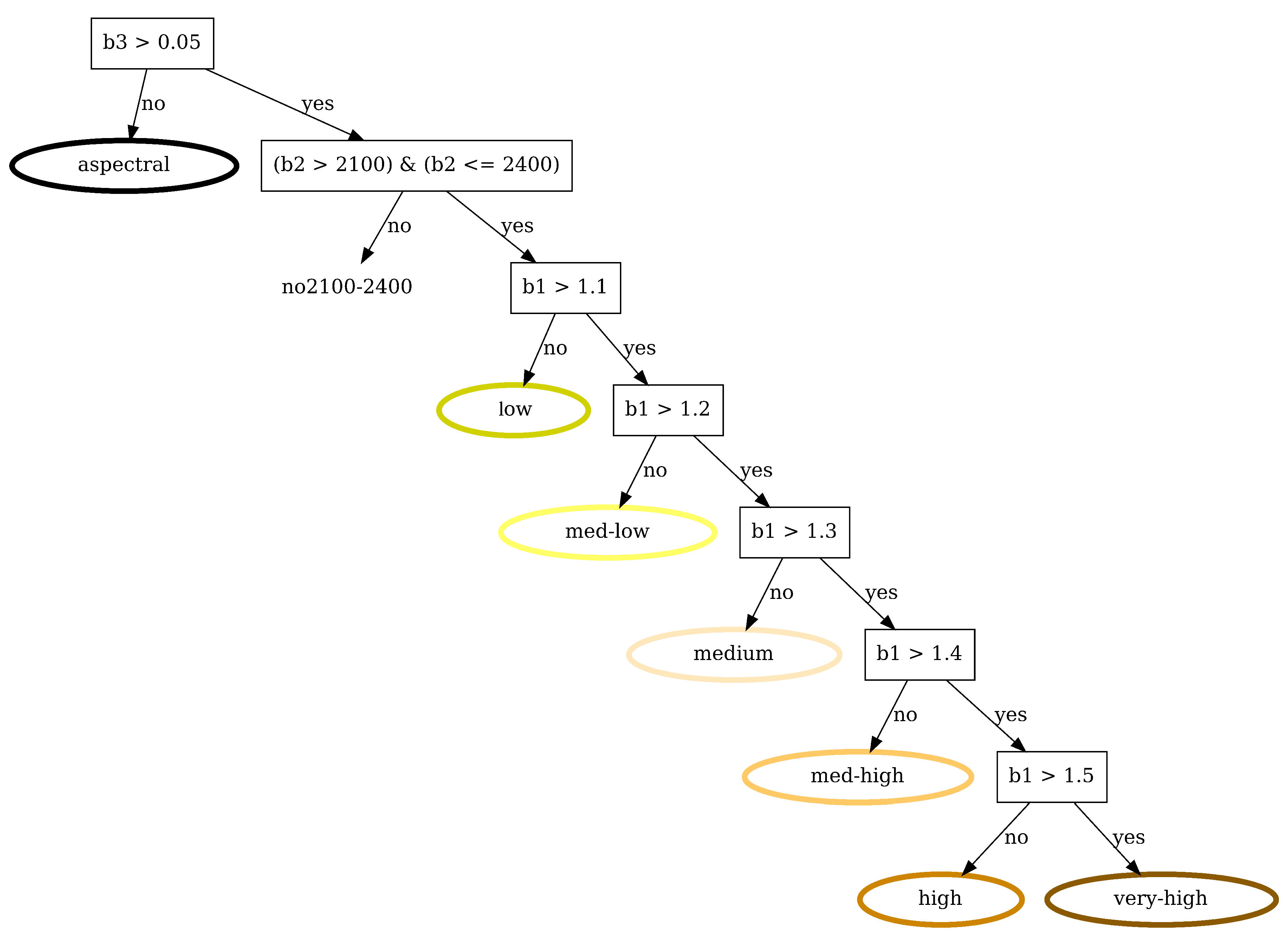

| fedrop_class | Slicing of ferrous drop (fedrop) image at thresholds: 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4 and 1.5 (see Figure A4). | |

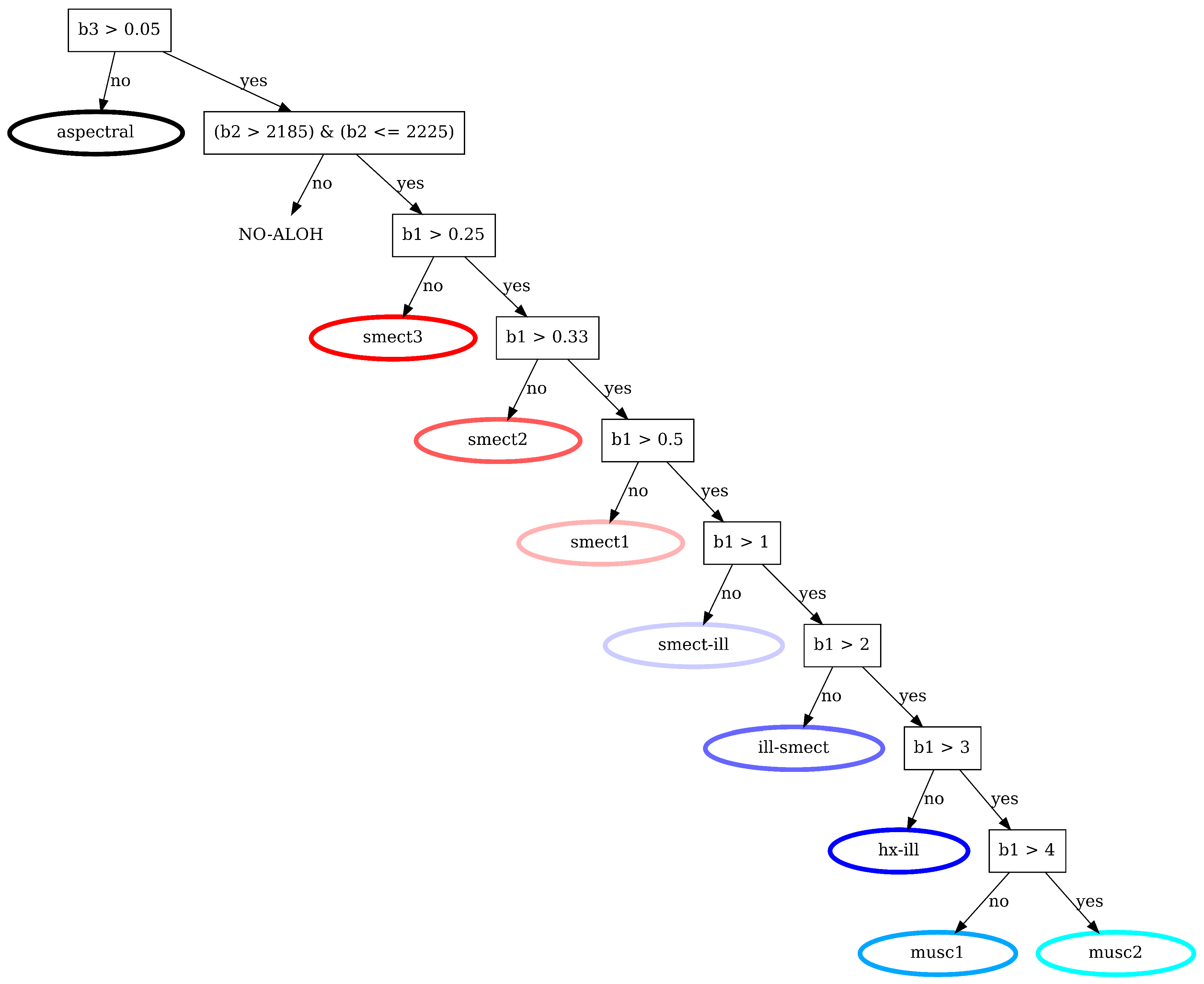

| illx_class | Slicing of illite crystallinity (illx) image at thresholds: 0.25, 0.33, 0.5, 1, 2, 3 and 4 (see Figure A5). | |

| illkaol_class | Slicing of illite over kaolinite (illkaol) image at thresholds: 0.95, 0.97, 0.99, 1.0, 1.01, 1.03 and 1.05 (see Figure A6). | |

| mineral_map | Classification using depth and wavelength positions of deepest features in the wavelength images between 2100 and 2400 nm and the illite crystallinity image. Customized for the rock sample set in this study (see Figure 2). |

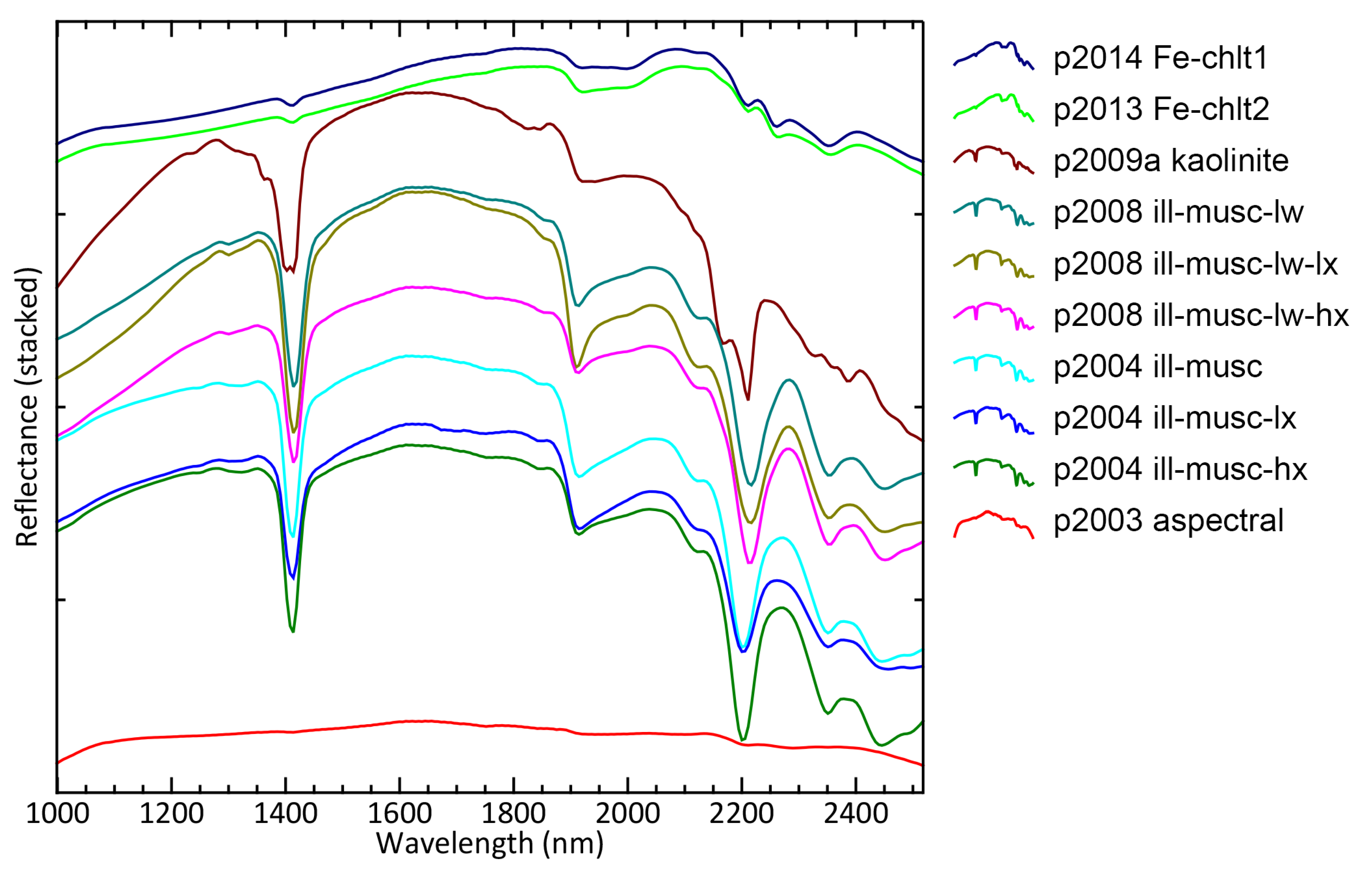

2.6. Mean Spectra of Classes

2.7. HypPy Software

2.8. Test Sample Set and Validation

| ID | Sample | Description |

|---|---|---|

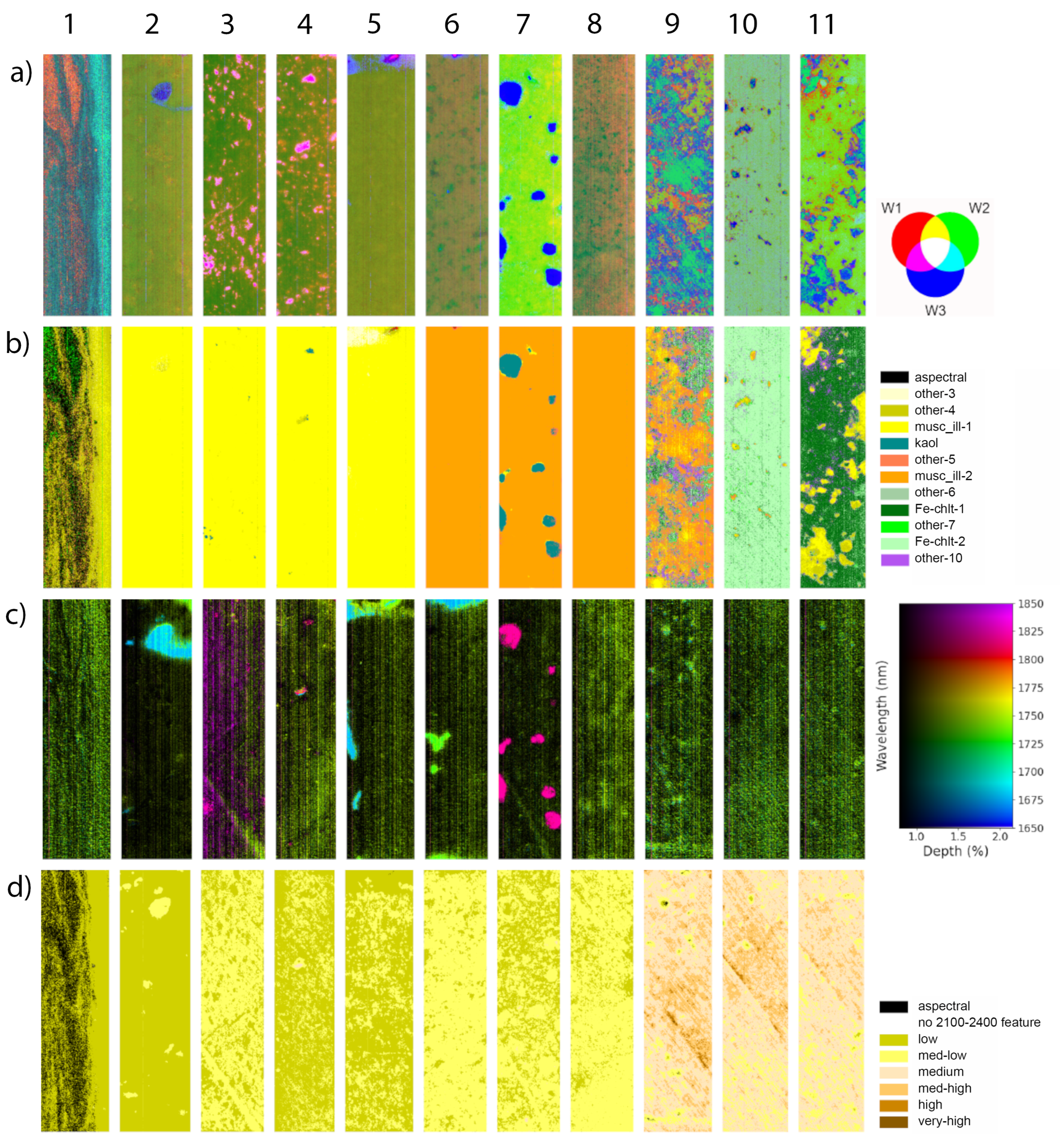

| 1 | P2003 | Weakly sericite altered and silicified muddy chert. |

| 2 | P2004 | Deuterically altered, silicified, seriticized (Al-rich), xenocrystic phenocrystic andesite. |

| 3 | P2005 | Deuterically altered, silicified, seriticized (Al-rich), phenocrystic andesite. |

| 4 | P2006 | Deuterically altered, silicified, seriticized (Al-rich), weakly phenocrystic andesite. |

| 5 | P2007 | Deuterically altered, silicified, seriticized (Al-rich), weakly phenocrystic quenched andesite. |

| 6 | P2008 | Deuterically altered, silicified, seriticized (Al-poor), weakly phenocrystic andesite. |

| 7 | P2009a | Deuterically altered, silicified, seriticized (Al-poor), weakly xenocrystic amygdaloidal basalt. Contains aproximately 15% kaolinite in amygdales. |

| 8 | P2010 | Deuterically altered, silicified, seriticized (Al-poor), weakly xenocrystic weakly amygdaloidal basalt. |

| 9 | P2012 | Deuterically altered, silicified, ferruginous, chloritised basalt. |

| 10 | P2013 | Deuterically altered, silicified, ferruginous, chloritised (pyroxene-bearing) basalt. |

| 11 | P2014 | Deuterically altered, silicified, chloritised amygdaloidal andesite. |

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Analysis

3.2. Mineral Maps

| Class | Count | Reference spectrum |

|---|---|---|

| ill-musc-sw | 2 | Muscovite_GDS113_Ruby; Muscovite_GDS113a_Ruby |

| phengite | 2 | Illite_GDS4.2_Marblehead; Illite_GDS4_Marblehead |

| epid/chlt | 5 | Chlorite_HS179.1B; Chlorite_HS179.2B; Chlorite_HS179.3B; Chlorite_HS179.4B; Chlorite_HS179.6 |

| ill-musc-hx | 3 | Muscovite_HS146.1B; Muscovite_HS146.3B; Muscovite_HS146.4B |

| ill-musc-lx | 2 | Illite_IMt-1.a; Illite_IMt-1.b_lt2um |

| ill-musc-lw-hx | 2 | Muscovite_GDS116_Tanzania; Muscovite_GDS116a_Tanzania |

| kaolinite | 3 | Kaolinite_CM9; Kaolinite_KGa-1_(wxl); Kaolinite_KGa-2_(pxl) |

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Weaknesses

4.3. Application

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. HypPy Command Line Syntax of Processing Steps

- 1.

-

Conversion of uncalibrated radiance to reflectance image ($FILE-IN = manifest.xml file):> darkwhiteref.py -f -m $FILE-IN -o $FILE-OUT px

- 2.

-

Spatial-spectral filtering (mean7 = mean filtering by 2 spectral and 5 spatial neighbours):> median.py -f -i $FILE-IN -o $FILE-OUT -m mean7

- 3.

-

Spectral math expression to create an optional mask file for dark background pixels (expression "S1.mean()>0.05" = mean pixel-spectrum is larger than 0.05; required for wavelength mapping command):> specmath.py -o $FILE-OUT -t int16 -e "S1.mean()>0.05" $FILE-IN

- 4.

-

Creation of wavelength image (-w 2100 -W 2400 = wavelength range from 2100 to 2400; -m div = continuum removal by division; -n 3 = calculation of 3 deepest features):> minwavelength2.py -f -i $FILE-IN -o $FILE-OUT –mask $MASKFILE -w 2100 -W 2400 -m div -n 3

- 5.

-

Creating a png image file of color composite of 1st, 2nd and 2rd deepest features in wavelength image (-R 0 -G 2 -B 4 = band numbers for the red, green and blue channels; -m SD = 2 standard deviations stretch mode):> tokml.py -i $FILE-IN -o $FILE-OUT -R 0 -G 2 -B 4 -m SD

- 6.

-

Creation of wavelength map from wavelength image (-w 2100 -W 2400 = wavelength stretch range from 2100 to 2400; -d 0 -D 0 = standard depth stretch; -l = saves legend as .png):> wavemap.py -f -i $FILE-IN -o $FILE-OUT -w 2100 -W 2400 -d 0 -D 0 -l

- 7.

-

Calculation of the summary products fedrop and illkaol (-u nan = input wavelength in nanometer; -l = creation of logfile):> otherindices.py -f -i $FILE-IN -o $FILE-OUT -u nan -l

- 8.

-

Band math formula to calculate illx from wavelength images 2100-2400nm and 1850-2100nm (Expression: `i1[1] / i2[1]’= ratio of band 1 in image 1 (wavelength image 2100-2400nm, $FILE-IN1) over band 1 in image 2 (wavelength image 1850-2100nm, $FILE-IN2)):> bandmath.py -o $FILE-OUT -e `i1[1] / i2[1]’ $FILE-IN1 $FILE-IN2

- 9.

-

Spectral math expression to calculate albedo image, i.e., the mean spectrum of each pixel (`S1.mean()’= expression to calculate mean of spectrum):> specmath.py -o $FILE-OUT -e `S1.mean()’$FILE-IN

- 10.

-

Band math formula to calculate illx from band ratio (expression: `i1(2178)/i1(2189)’= ratio of bands 2187 over 2189 nm):> bandmath.py -o $FILE-OUT -e `i1(2178)/i1(2189)’ $FILE-IN

- 11.

-

Spectral math expression to calculate Shannon entropy (expression: `(1-S1).entropy2()’= calculation of Shannon entropy):> specmath.py -o $FILE-OUT -e `(1-S1).entropy2()’ $FILE-IN

- 12.

-

Classification using decision tree ($DT) of bands 0 (b2), 1 (b3) and 2 (b7) of wavelength image ($FILE-IN):> decisiontree.py -t $DT -o $FILE-OUT -b2 $FILE-IN 0 -b3 $FILE-IN 1 -b7 $FILE-IN 2

- 13.

-

Creation of legend of classified file ($FILE-IN):> makelegend.py -i $FILE-IN

- 14.

-

Calculation of mean spectra of all classes in class file ($CLASS-IN) from reflectance image ($FILE-IN) (-o $PLOT-OUT = plot of mean spectra; -l $SPECLIB = folder with ASCII mean spectra; -r $CLASSREPORT = report of class percentages in image):> classstats.py -i $FILE-IN -c $CLASS-IN -o $PLOT-OUT -l $SPECLIB -r $CLASSREPORT

Appendix B. Wavelength Maps

Appendix C. Decision trees

References

- Acosta, I.C.C.; Khodadadzadeh, M.; Tolosana-Delgado, R.; Gloaguen, R. Drill-core hyperspectral and geochemical data integration in a superpixel-based machine learning framework. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2020, 13, 4214–4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baissa, R.; Labbassi, K.; Launeau, P.; Gaudin, A.; Ouajhain, B. Using HySpex SWIR-320m hyperspectral data for the identification and mapping of minerals in hand specimens of carbonate rocks from the Ankloute Formation (Agadir Basin, Western Morocco). Journal of African Earth Sciences 2011, 61, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalm, M.; Buxton, M.; Van Ruitenbeek, F. Discriminating ore and waste in a porphyry copper deposit using short-wavelength infrared (SWIR) hyperspectral imagery. Minerals engineering 2017, 105, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, F. Identification and mapping of minerals in drill core using hyperspectral image analysis of infrared reflectance spectra. International Journal of Remote Sensing 1996, 17, 1623–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, M.; Roy, R.; Launeau, P.; Cathelineau, M.; Quirt, D. Alteration mapping on drill cores using a HySpex SWIR-320m hyperspectral camera: Application to the exploration of an unconformity-related uranium deposit (Saskatchewan, Canada). Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2017, 172, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Groat, L.A.; Rivard, B.; Belley, P.M. Reflectance spectroscopy and hyperspectral imaging of sapphire-bearing marble from the beluga occurrence, Baffin Island, Nunavut. The Canadian Mineralogist 2017, 55, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, F.D.; Van der Werff, H.M.; Van Ruitenbeek, F.J.; Hecker, C.A.; Bakker, W.H.; Noomen, M.F.; Van Der Meijde, M.; Carranza, E.J.M.; De Smeth, J.B.; Woldai, T. Multi-and hyperspectral geologic remote sensing: A review. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2012, 14, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.N. Spectroscopy of rocks and minerals, and principles of spectroscopy. In Manual of Remote sensing; Rencz, A.N., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Laukamp, C.; Rodger, A.; LeGras, M.; Lampinen, H.; Lau, I.C.; Pejcic, B.; Stromberg, J.; Francis, N.; Ramanaidou, E. Mineral physicochemistry underlying feature-based extraction of mineral abundance and composition from shortwave, mid and thermal infrared reflectance spectra. Minerals 2021, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, S.; de Souza Filho, C.R. A review on spectral processing methods for geological remote sensing. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2016, 47, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, T.H.; Buckley, S.J.; Howell, J.A. Close-range hyperspectral imaging for geological field studies: Workflow and methods. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2013, 34, 1798–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodger, A.; Fabris, A.; Laukamp, C. Feature extraction and clustering of hyperspectral drill core measurements to assess potential lithological and alteration boundaries. Minerals 2021, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J.; Black, S. Hyperspectral analytics in ENVI. Available at: https://www.spectroexpo.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Hyperspectral_Whitepaper.pdf; accessed 2-April-2025, 2018.

- Kleynhans, T.; Messinger, D.W.; Delaney, J.K. Towards automatic classification of diffuse reflectance image cubes from paintings collected with hyperspectral cameras. Microchemical Journal 2020, 157, 104934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, F.; Letkoff, A.; Boardmann, J.; Heidebrecht, K.; Shapiro, A.; Barloon, P.; Goetz, A. The spectral image processing system (SIPS) – interactive visualization and analysis of imaging spectrometer data. Remote Sensing of Environment 1993, 44, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, J.W.; Kruse, F.A. Analysis of imaging spectrometer data using n-dimensional geometry and a mixture-tuned matched filtering approach. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2011, 49, 4138–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioucas-Dias, J.M.; Plaza, A.; Dobigeon, N.; Parente, M.; Du, Q.; Gader, P.; Chanussot, J. Hyperspectral unmixing overview: Geometrical, statistical, and sparse regression-based approaches. IEEE journal of selected topics in applied earth observations and remote sensing 2012, 5, 354–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, M.; Haut, J.; Plaza, J.; Plaza, A. Deep learning classifiers for hyperspectral imaging: A review. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2019, 158, 279–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, C.; Van der Meijde, M.; Van Der Werff, H.; Van Der Meer, F.D. Assessing the influence of reference spectra on synthetic SAM classification results. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2008, 46, 4162–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, W.; van Ruitenbeek, F.; van der Werff, H.; Hecker, C.; Dijkstra, A.; van der Meer, F. Hyperspectral Python – HypPy. Algorithms 2024, 17, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ruitenbeek, F. High-resolution, laboratory acquired hyperspectral images of rock samples from the footwall of the Kangaroo Caves Cu-Zn deposit, Pilbara, Western Australia. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Hecker, C.; van Ruitenbeek, F.J.; van der Werff, H.M.; Bakker, W.H.; Hewson, R.D.; van der Meer, F.D. Spectral absorption feature analysis for finding ore: A tutorial on using the method in geological remote sensing. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2019, 7, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ruitenbeek, F.J.; Bakker, W.H.; van der Werff, H.M.; Zegers, T.E.; Oosthoek, J.H.; Omer, Z.A.; Marsh, S.H.; van der Meer, F.D. Mapping the wavelength position of deepest absorption features to explore mineral diversity in hyperspectral images. Planetary and Space Science 2014, 101, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviano, C.; Seelos, F.; Murchie, S.; Kahn, E.; Seelos, K.; Taylor, H.; Taylor, K.; Ehlmann, B.; Wiseman, S.; Mustard, J.; et al. Revised CRISM spectral parameters and summary products based on the currently detected mineral diversity on Mars. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2014, 119, 1403–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontual, S.; Merry, N.; Gamson, P. GMEX, Practical applications handbook; AusSpec International Pty. Ltd., 1997.

- Dalm, M.; Buxton, M.W.; van Ruitenbeek, F.J.; Voncken, J.H. Application of near-infrared spectroscopy to sensor based sorting of a porphyry copper ore. Minerals Engineering 2014, 58, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ruitenbeek, F.; Goseling, J.; Bakker, W.H.; Hein, K.A. Shannon entropy as an indicator for sorting processes in hydrothermal systems. Entropy 2020, 22, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safavian, S.R.; Landgrebe, D. A survey of decision tree classifier methodology. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1991, 21, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ruitenbeek, F.; van der Werff, H.; Hein, K.; van der Meer, F. Detection of pre-defined boundaries between hydrothermal alteration zones using rotation-variant template matching. Computers & Geosciences 2008, 34, 1815–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hinsberg, C. An integrated study of hydrothermal white mica in the footwall of the Kangaroo Caves VMS deposit, Western Australia 2010. Master’s thesis, Available at https://studenttheses.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12932/5473/Thesis.pdf?sequence=1; accessed 2-April-2025.

- Kokaly, R.; Clark, R.; Swayze, G.; Livo, K.; Hoefen, T.; Pearson, N.; Wise, R.; Benzel, W.; Lowers, H.; Driscoll, R.; et al. USGS spectral library version 7 data: US Geological Survey data release. United States Geological Survey (USGS): Reston, VA, USA 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, G.R. Spectral signatures of particulate minerals in the visible and near infrared. Geophysics 1977, 42, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, E. Near infrared spectra of muscovite, Tschermak substitution, and metamorphic reaction progress: Implications for remote sensing. Geology 1994, 22, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ruitenbeek, F.; van der Werff, H.; Bakker, W.; van der Meer, F.; Hein, K. Measuring rock microstructure in hyperspectral mineral maps. Remote Sensing of Environment 2019, 220, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitri, K.; Hecker, C.; van Ruitenbeek, F.; Sihotang, M. A decision-tree classifier for infrared imaging spectroscopy with geothermal expert knowledge in preparation.

- Martynenko, S.; Tuisku, P.; van Ruitenbeek, F.; Hein, K. High-resolution short-wave infrared hyperspectral characterization of alteration at the Sadiola Hill gold deposit, Mali, Western Africa. In Proceedings of the 15th Biennial Meeting of the Society for Geology Applied to Mineral Deposits: Life with ore deposits on Earth. University of Glasgow, 2019, p. 1325. [Available at https://ris.utwente.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/138697676/283_SGA_Martynenko_et_al_2019_Final.pdf; accessed 2-April-2025].

| 1 | ENVI is a trademark of NV5 Geospatial Solutions, Inc. |

| Name | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Albedo | Mean reflectance value of all bands in a pixel spectrum. | Brightness. |

| Ferrous drop (fedrop) | Ratio of reflectance bands at 1600 over 1310 nm [25]. | Indication of ferrous iron in minerals, e.g. illite and carbonates. High values indicate abundant ferrous iron in the mineral. |

| Illite crystallinity (illx) | Ratio of the depths of deepest features between 2100-2400 and 1850-2100 nm, i.e., the depths of the Al-OH feature and water features of smectite-illite-muscovite minerals [25]. | Indication of the degree of ordering of the mineral (e.g., [26]); High values indicate relatively high degrees of ordering. |

| Illite-kaolinite (illkaol) | Ratio of reflectance bands at 2164 over 2180 nm. The 2164 nm band is positioned at the second deepest feature of the doublet feature of kaolinite and the 2180 nm band is position at the high between the double feature [25]. | Indication for the relative amounts of illite (high values) and kaolinite (low values). Note that the values are affected by the type of kaolinite in the rock and the center wavelengths of the bands of the hyperspectral camera used. |

| Shannon entropy | Measure from information theory: |

It measures the deviation from a flat horizontal spectrum. A flat spectrum results in highest Shannon entropy values. Spectra with few but deep features produce low values. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).