1. Introduction

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are a diverse family of biodegradable polyesters synthesized by microorganisms through microbial fermentation using renewable carbon sources such as sugars, fatty acids, and agricultural by-products. Their biosynthesis is regulated by a sequence of enzymatic reactions, with PHA synthases playing a key role in catalyzing the polymerization of hydroxyalkanoate monomers [

1,

2]. By carefully controlling the carbon source, fermentation conditions, and microbial strain, it is possible to produce various types of PHAs with a wide range of monomer compositions and material properties [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Among the different PHAs, poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-

co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (P3HBHHx) stands out due to its superior flexibility and mechanical performance compared to poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB). The incorporation of 3-hydroxyhexanoate (3HHx) comonomer units increases the elasticity and toughness of the polymer, making P3HBHHx particularly suitable for applications in packaging, agriculture, and biomedical fields [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Despite these promising properties, a key limitation of P3HBHHx for industrial use is its slow crystallization rate, especially in copolymers with higher 3HHx content [

14]. This slow crystallization behavior can hinder manufacturing processes such as injection molding and extrusion, leading to longer cycle times, incomplete solidification, and product defects. One effective strategy to accelerate crystallization is the addition of nucleating agents, which facilitate crystal formation and enhance the rate of crystallization [

15,

16,

17]. Such additives have been widely applied in biodegradable polymers, including polylactic acid (PLA) and other PHAs [

15,

18,

19,

20,

21].

In this study, a range of nucleating agents, including boron nitride (BN), poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), talc, organic potassium salts (LAK), and ultrafine cellulose (UFC), were incorporated into neat P3HBHHx to evaluate their effect on crystallization behavior, thermal stability, and mechanical performance. Both non-isothermal and isothermal crystallization behaviors were analyzed using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), with crystallization kinetics assessed through the Avrami and Lauritzen-Hoffman models. Thermal stability was examined using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and molecular degradation was evaluated via gel permeation chromatography (GPC). Mechanical properties were assessed through tensile testing. Additionally, polarized optical microscopy (POM) was used to study spherulitic morphology, crystal growth rates, and nucleation density. Self-nucleation experiments were conducted to quantify nucleation efficiency and provide deeper insight into the effectiveness of each additive.

By systematically comparing the crystallization behavior and material performance of P3HBHHx with various nucleating agents, this study aims to identify the most effective additive for enhancing processability and expanding the industrial applicability of this biodegradable polymer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (P3HBHHx, 6% 3HHx, grade BP330_05, Helian Polymers) was used as the base polymer in this study. The nucleating agents include boron nitride (LL-SP 010, HeBoFill GmbH), organic potassium salt (LAK-301, Takemoto Oil & Fat Co., Ltd), poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (P3HB, grade PB3000G, PhaBuilder), ultrafine cellulose (UFC 100, Arbocel, J. Rettenmaier & Söhne), and talc (Intalc 10CG, euroMinerals GmbH). All nucleating agents were used as received, without further purification.

2.2. Sample Preparation

P3HBHHx samples containing each nucleating agent at concentrations of 0.5 wt% and 2 wt% were prepared by melt blending. The blending was carried out using a Process 11 twin-screw extruder (Process 11, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a length-to-diameter (L/D) ratio of 40:1. The barrel temperature profile was set between 145 ˚C and 160 ˚C. Following extrusion, the materials were pelletized and subsequently dried in an oven at 60 ˚C overnight.

Injection molding of the dried pellets was performed using a MiniJet Pro injection molding machine (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at an injection temperature of 160 ˚C and a mold temperature of 50 ˚C, producing standardized test specimens suitable for thermal and mechanical analyses.

Neat P3HBHHx (without additives) was used as the control sample. The detailed composition of all prepared samples is summarized in

Table 1.

2.3. Sample Characterization

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) analysis was conducted using a Jasco FTIR 4700 spectrometer (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Specac MKII Golden Gate Single Reflection Diamond ATR system. Samples were scanned over a wavelength range of 4000-650 cm-1, and the resulting spectra were compared to identify any changes in functional groups or molecular interactions.

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) was utilized to assess whether the addition of nucleating agents led to any significant degradation of the polymer chains. The analysis was performed using a Shimadzu LC-8A liquid chromatographic pump (Tokyo, Japan) controlled by the LC Solution software (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). For each sample, 10 mg were dissolved in 1 mL of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) containing 0.05 M sodium trifluoroacetate (CF3COONa), which was also the eluent for the column. The flow rate was set at 1 mL/min and the injected volume was 20 µL with a sample concentration of 10 mg/mL. A PL-HFIP-gel column (Agilent Technologies Deutschland GmbH, Boblingen, Germany) and a refractive index detector (Shimadzu, model RID-20A, Tokyo, Japan) were employed. The molecular weights (Mw and Mn) and polydispersity index (PDI) of each sample were determined using polymethyl methacrylate standards.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a TA Instruments Q50 thermogravimetric analyzer (New Castle, DE, USA) to investigate the thermal stability of the P3HBHHx samples in the presence of nucleating agents. The samples were heated from room temperature to 550 ˚C at a rate of 10 ˚C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere. The degradation temperature and weight loss profiles were analyzed to detect any sign of thermal degradation induced by the nucleating agent.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis was performed using a TA Instruments Q100 series calorimeter, equipped with a refrigerated cooling system capable of operating within a temperature range of -90 to 550 ˚C (New Castle, DE, USA). Each experiment was conducted under a flow of dry nitrogen, using approximately 4 mg of sample. The instrument was calibrated for both temperature and heat of fusion using an indium standard, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the measurements. A series of DSC experiments were conducted to investigate the effect of various nucleating agents on the crystallization behavior of P3HBHHx, as detailed in the following sections.

The spherulitic growth rate was measured using a polarized light microscope (Zeiss Axioskop 40 Pol, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a Linkam temperature-controlled hot stage (THMS 600) connected to an LNP 94 liquid nitrogen cooling system. Spherulites were grown from homogeneous thin films prepared by melt pressing, with the film thickness controlled at approximately 10 µm. To remove any thermal history, samples were first heated to 100 ˚C and held for 5 minutes. They were then cooled to the desired isothermal crystallization temperature and held to allow for the growth of measurable spherulites. The radius of the growing spherulites was recorded over time using micrographs captured at regular intervals with a Zeiss AxiosCam MRC5 digital camera. These measurements were used to calculate the spherulitic growth rate.

The mechanical properties of the P3HBHHx samples containing nucleating agents were evaluated by tensile testing using an Instron Universal Testing Machine (Model 34SC-5 Single Column, Instron, Norwood, MA, USA), following the ASTM D527 standard. Test specimens measured 75 mm x 5 mm x 2 mm. The crosshead speed was set to 20 mm/min, and the load cell capacity was 100 kN. Mechanical parameters, including tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and elongation at break, were determined using Instron Bluehill software. For each sample, at least five specimens were tested to ensure reliable and reproducible results.

2.4. Non-Isothermal Crystallization

The non-isothermal crystallization behavior was studied using a three-step protocol. First, samples were heated from room temperature to 200 ºC at a rate of 10 °C/min to eliminate any previous thermal history. This was followed by a cooling run from 200 ºC to -50 ºC at the same rate. Finally, a second heating run was performed from -50 °C to 200 ºC at the same rate. From this second heating cycle, the melting temperature (Tm) and the apparent enthalpy of fusion (ΔHf) were determined.

2.5. Isothermal Crystallization

The isothermal crystallization process was also conducted using a three-step protocol. First, the sample was rapidly heated to 200 ºC at a rate of 50 ºC/min to eliminate any thermal history. Next, it was cooled at the maximum rate (i.e., 100 ºC/min) allowed by the apparatus to the predetermined isothermal crystallization temperature and held isothermally to allow crystallization over time. Finally, the sample was reheated to 200 ºC at a rate of 10 ºC/min to evaluate the thermal properties of the isothermally crystallized material.

2.6. Self-Nucleation Experiments

Self-nucleation experiments were conducted to quantitatively evaluate the nucleation efficiency of the selected additives on the crystallization behavior of P3HBHHx. The procedure was based on the methodology developed by Wittmann et al. [

22,

23]. The protocol consisted of the following steps: first, samples were heated to 200 ºC at a rate of 50 ºC/min to erase their thermal history. Subsequently, they were cooled to 60 ºC at 5 ºC/min to establish a standard thermal history, followed by isothermal crystallization at 60 ºC for 10 min to ensure full crystallization. Once crystallized, the samples were reheated at 10 ºC/min to a defined self-nucleation temperature (

Ts) within the partial melting zone and held at this temperature for 5 min to induce self-nucleated crystalline seeds. Finally, the samples were cooled to 30 ºC at 5 ºC/min, and the resulting crystallization peak was recorded during the cooling run.

The nucleation efficiency (NE) of each nucleating agent was calculated according to Equation (1):

where

is the minimum crystallization temperature corresponding to the fully molten state of the polymer (i.e., no residual crystals remain), and

is the maximum crystallization temperature obtained when the polymer was partially melted at a carefully selected

Ts. Both

and

were determined using neat P3HBHHx (without nucleating agents), while

Tc refers to the crystallization peak temperature of each nucleating agent loaded P3HBHHx during the DSC cooling run.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Non-Isothermal Crystallization Behavior of P3HBHHx. Effect of Nucleating Agents

3.1.1. Thermal Behavior of neat P3HBHHx

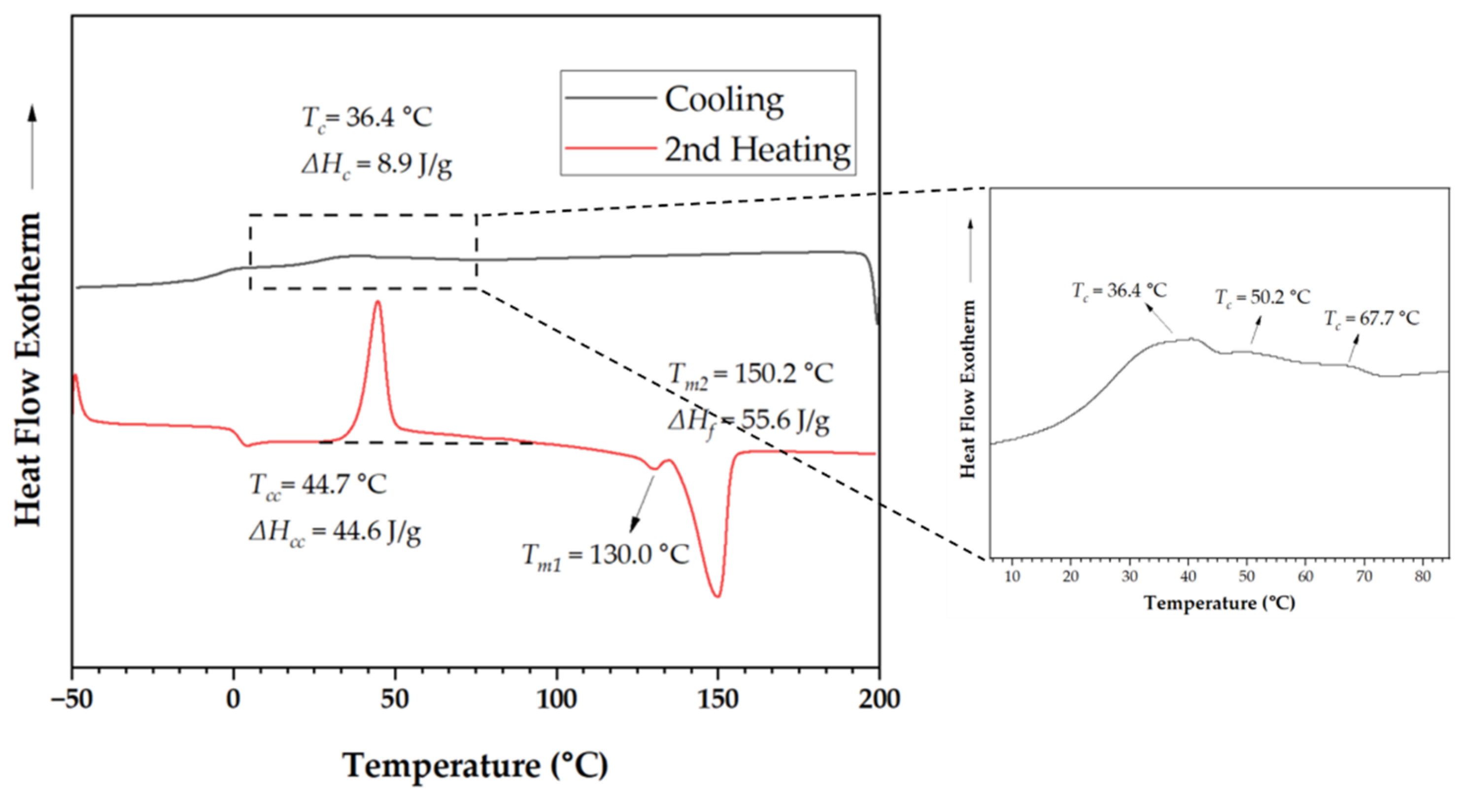

Figure 1 presents the DSC thermograms of neat P3HBHHx during the non-isothermal crystallization process, revealing two distinct crystallization events. During the cooling run at 10 ˚C/min (see inset of

Figure 1), a weak and broad crystallization peak appears at 36.4 ˚C, with a relatively low enthalpy of 8.9 J/g. This indicates that only a small fraction of the polymer crystallizes upon cooling. The broad shape and low intensity of the peak suggest non-uniform and kinetically limited crystallization, likely due to the random incorporation of 3HHx comonomer units, which disrupt chain regularity and hinder nucleation and crystal growth.

Upon reheating, a second crystallization peak appears at 44.7 ˚C, with a significantly higher enthalpy of 44.6 J/g. This cold crystallization event accounts for the majority of the crystalline fraction and suggests that more stable and ordered crystalline domains preferentially form from the amorphous solid state rather than directly from the melt. It is noticeable that the cold crystallization peak exhibits a long tail extending beyond 100 ˚C, highlighting the difficulty in achieving complete crystallization due to the presence of 3HHx units.

A double melting peak is observed during the reheating curve. This behavior is typical of semicrystalline polymers and is commonly attributed to the coexistence of multiple crystalline populations. The lower melting peak at 130 ˚C corresponds to less ordered, imperfect crystals formed during the initial crystallization, while the higher melting peak at 150 ˚C is associated with more stable lamellae that formed during the heating process.

These results highlight a significant challenge in processing neat P3HBHHx for industrial applications, especially its slow and incomplete crystallization behavior. In manufacturing processes such as injection molding and extrusion, where rapid cooling is essential, the limited crystallization rate can lead to incomplete solidification, uneven mechanical properties, and defects such as warping. The DSC analysis clearly shows the need for nucleating agents to overcome these limitations. By increasing the crystallization rate, these additives are expected to promote faster crystal growth, improve the uniformity of crystalline regions, and reduce processing times. As a result, the overall suitability of P3HBHHx for industrial use can be significantly improved.

3.1.2. Effect of Nucleating Agents on Non-Isothermal Crystallization of P3HBHHx

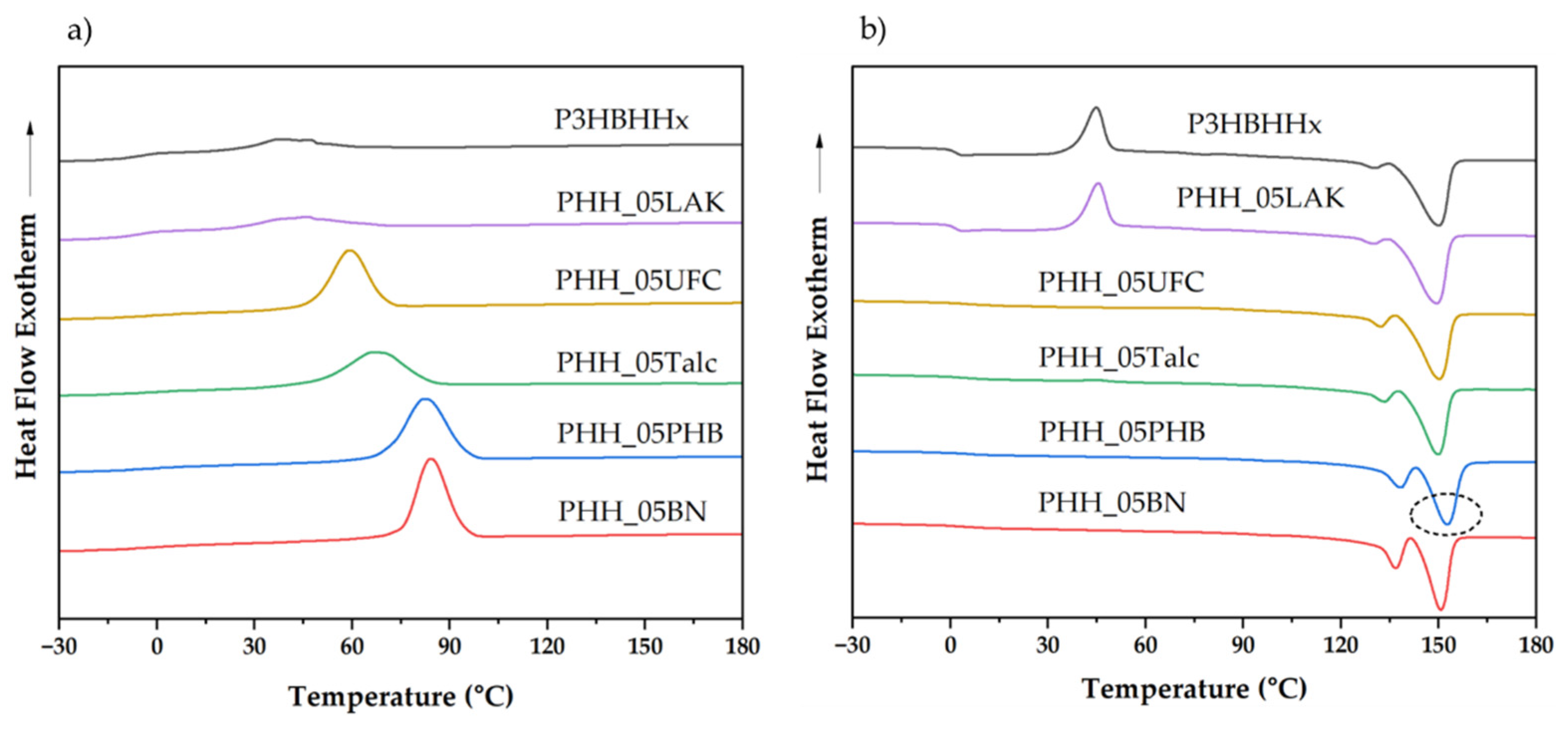

The non-isothermal crystallization behavior of P3HBHHx containing 0.5 wt% nucleating agents was investigated. The results are summarized in

Table 2 and illustrated in

Figure 2a and

2b. The incorporation of nucleating agents led to a significant increase in the crystallization temperature (

Tc) compared to that of neat P3HBHHx.

The most pronounced improvements were observed for boron nitride (PHH_05BN) and PHB (PHH_05PHB), which raised Tc from 36.4 ˚C (neat P3HBHHx) to 84.1 ˚C and 81.9 ˚C, respectively. This substantial increase indicates that both additives effectively promote crystal formation during cooling. In addition, the crystallization enthalpy increased markedly, from 8.9 J/g in neat P3HBHHx to 59.5 J/g in the PHB-loaded sample. The absence of cold crystallization peaks during the second heating run further confirms that crystallization was completed during the cooling phase, leaving no residual amorphous regions to crystallize upon reheating. These findings suggest that both BN and PHB are highly effective in enhancing nucleation and accelerating crystallization kinetics.

Talc and UFC also improved the crystallization behavior of P3HBHHx, increasing Tc to 66.5 ˚C and 58.9 ˚C, respectively. However, the presence of a cold crystallization peak in the PHH_05Talc sample, along with its relatively low crystallization enthalpy (i.e., 46.3 J/g), indicates incomplete crystallization. This suggests that while talc provides nucleation sites, it does not achieve the same level of efficiency as boron nitride or PHB. In contrast, UFC enhances crystallization kinetics compared to neat P3HBHHx, but its performance remains moderate when compared to the more effective nucleation agents.

The addition of organic potassium salt (LAK) resulted in only a slight increase in Tc to 45.6 ˚C. The limited shift in crystallization temperature, along with the presence of cold crystallization during reheating, indicates that LAK is less effective in promoting crystallization from the melt. A substantial portion of the polymer remains amorphous after cooling, further confirming its low nucleation efficiency.

The addition of nucleating agents had little impact on the melting temperatures (

Tm1 and

Tm2) of P3HBHHx, except in the case of PHB, where a slight increase was observed, as highlighted by the dashed ellipsoid in

Figure 2b. For the PHH_05PHB, the first melting peak increased to 138.1 ˚C, and the second peak increased to 152.7 ˚C. This shift is likely due to the development of thicker lamellae during crystallization process (note the difference of more than 40 ˚C between the crystallization temperatures of the neat polymer and PHB loaded sample). Similar but less pronounced effects were observed with boron nitride, where the first melting peak increased to 136.6 ˚C, while the second melting peak remained unchanged.

These results confirm that the addition of nucleating agents can significantly alter the crystallization behavior of neat P3HBHHx by enhancing crystallization kinetics and increasing the degree of crystallinity. Among the tested additives, boron nitride and PHB exhibited the highest efficiency, resulting in faster and more complete crystallization during cooling. Talc and ultrafine cellulose provided moderate improvements in crystallization behavior.

3.1.3. Effect of Increased Nucleating Agent Concentration on the Crystallization Behavior of P3HBHHx

To evaluate whether 0.5 wt% of nucleating agents is sufficient to enhance the crystallization behavior of P3HBHHx, a higher concentration of 2 wt% was also tested. As shown in

Figure S1, increasing the concentration of BN and PHB to 2 wt% resulted in only minor improvements. The

Tc increased by approximately 3 to 5 ˚C, while

ΔHc increased by 2 to 6 J/g (

Table S1). These slight increases suggest that the nucleation efficiency of BN and PHB is already near saturation at 0.5 wt%, indicating that higher concentrations are unnecessary.

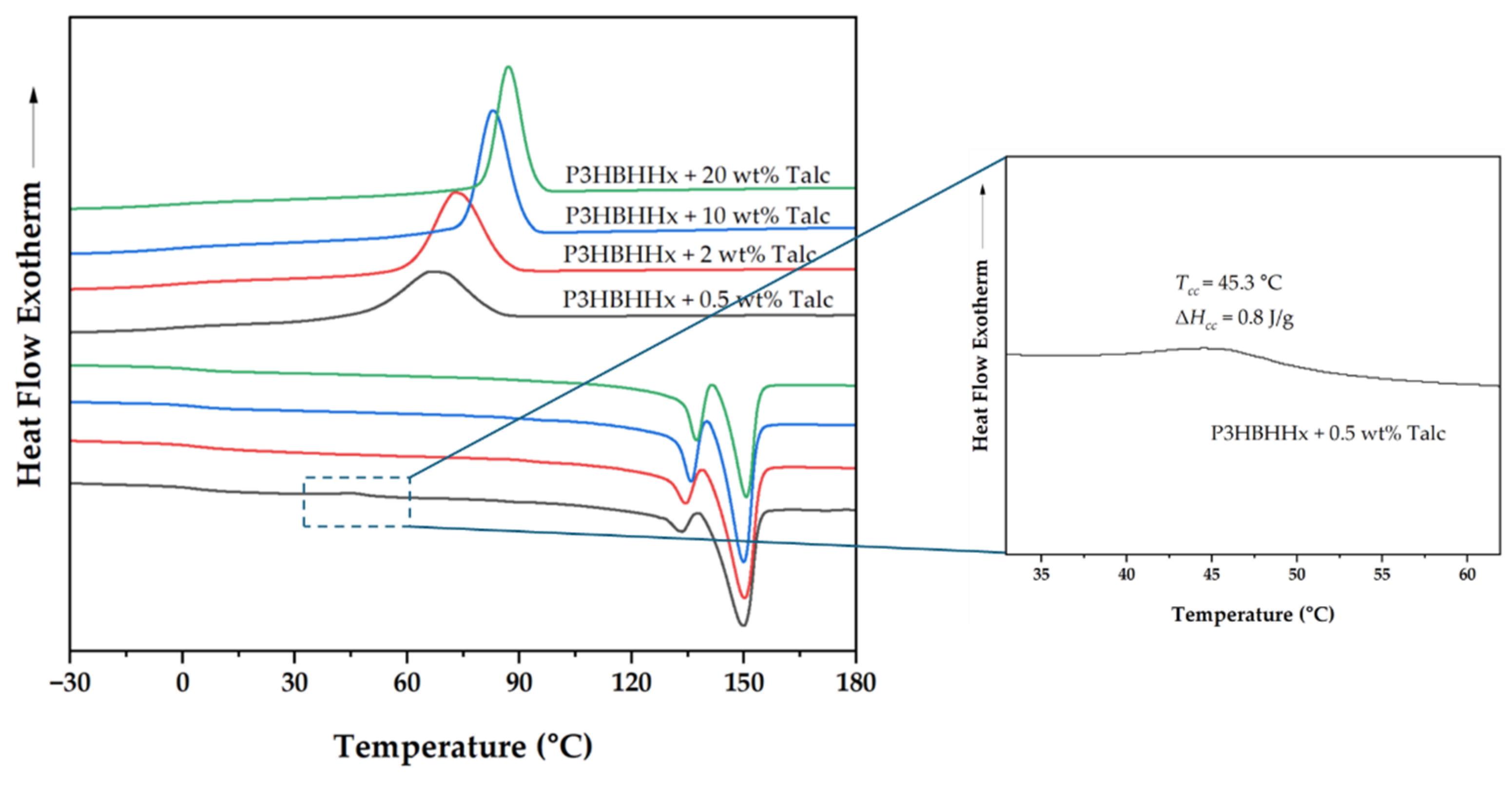

In contrast, talc exhibited a more concentration-dependent effect on the crystallization behavior of P3HBHHx.

Figure 3 compares samples with talc loadings ranging from 0.5 wt% to 20 wt%. At 2 wt%, the

Tc increased significantly from 66.5 ˚C to 72.6 ˚C, and the

ΔHc rose from 46.3 J/g to 57.1 J/g. Additionally, the cold crystallization peak observed at 0.5 wt% disappeared at 2 wt%, as shown in the inset of

Figure 3. Higher talc concentrations, including 10 wt% and 20 wt%, were also evaluated and resulted in further improvements in crystallization behavior. However, at these elevated loadings, the large quantity of talc not only affects crystallization but also has a considerable influence on other properties, such as mechanical performance, processability, and potentially on biodegradability. For these reasons, 2 wt% talc was selected for further investigation in the following studies.

For ultrafine cellulose (UFC), increasing the concentration to 2 wt% resulted in a more defined and sharper crystallization peak, indicating improved nucleation uniformity and more consistent nucleation site formation. However, the ΔHc remained largely unchanged compared to the 0.5 wt% sample, suggesting that UFC primarily enhances crystalline uniformity rather than improving crystallization efficiency.

Lastly, increasing the concentration of LAK to 2 wt% showed no improvement in either

Tc or

ΔHc (

Table 2 and

Table S1,

Figure S1). These results indicate that organic potassium salt based nucleating agent lacks sufficient nucleating activity to influence the crystallization behavior of P3HBHHx, even at higher concentrations.

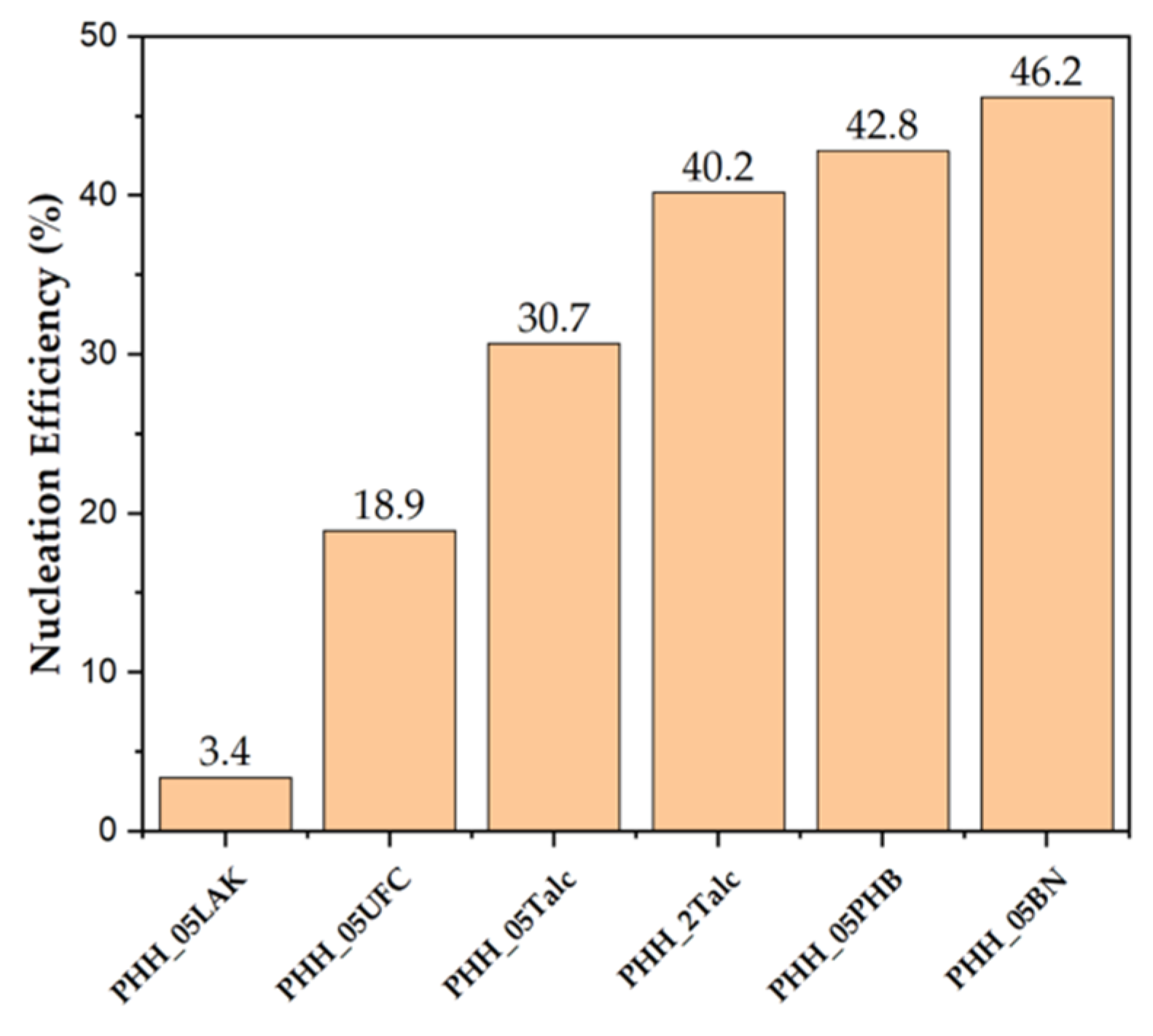

3.1.4. Nucleation Efficiency

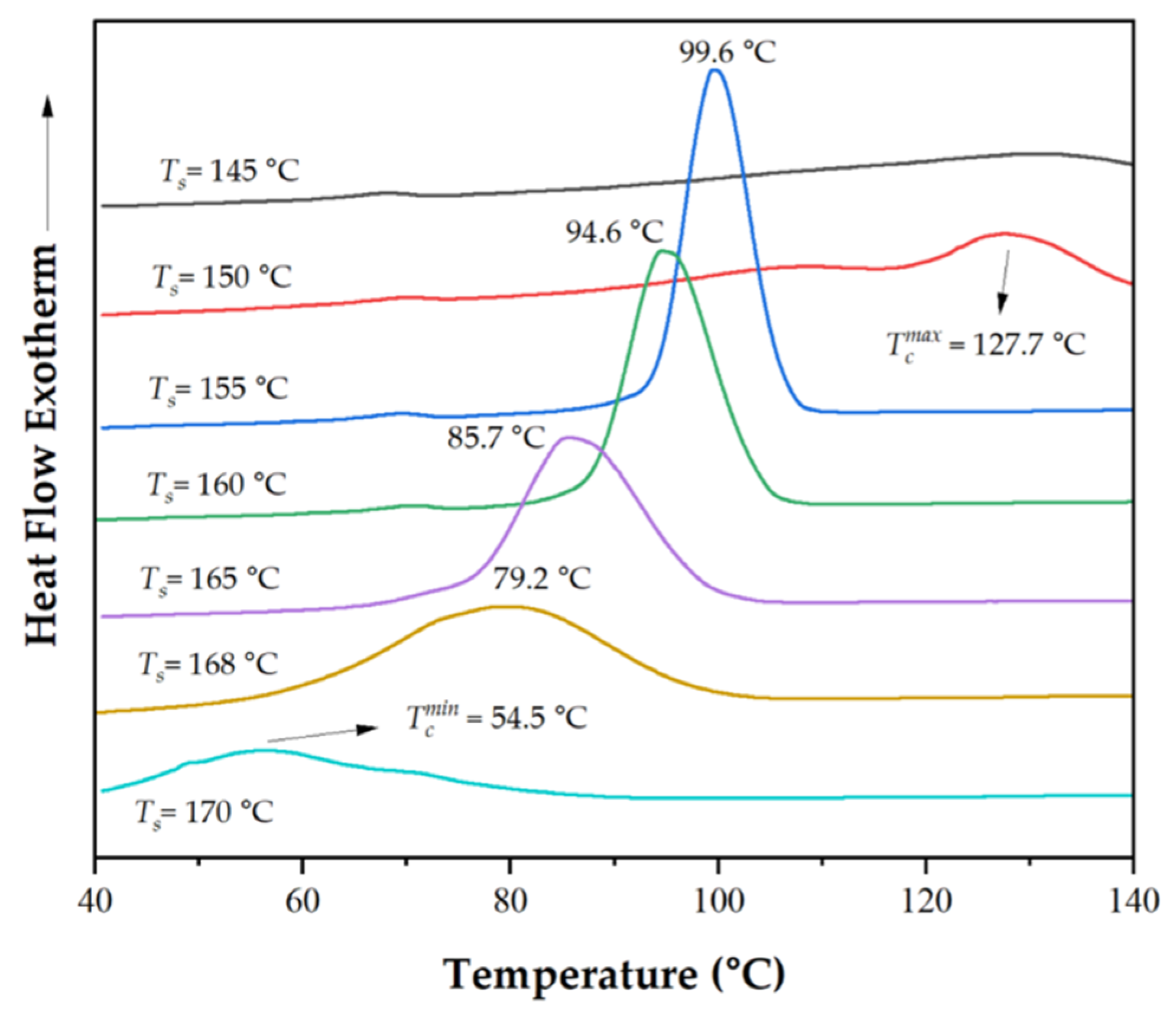

As shown in

Figure 4, self-nucleation experiments revealed that fully crystallized P3HBHHx exhibits distinct crystallization behavior when reheated to different self-nucleation temperatures (

Ts). At

Ts = 145 ˚C, no crystallization was observed during the subsequent cooling phase. Since melting had not occurred at this temperature, the original crystalline structures remained intact, and recrystallization was not initiated.

When Ts increased to 150 ˚C, partial melting occurred, leaving some crystalline domains intact. These residual structures acted as nucleating sites, resulting in rapid crystallization during cooling. Under these conditions, the crystallization temperature was recorded as = 127.7 ˚C for neat P3HBHHx.

As Ts increased further, the crystallization temperature progressively decreased due to the melting of additional crystalline domains. At Ts = 170 ˚C, all the nuclei were completely melted, leaving no residual sites for nucleation. In this case, the crystallization temperature was identified as = 54.5 ˚C. It is important to note that in a previous non-isothermal crystallization study, the crystallization temperature of neat P3HBHHx was reported as 36.4 ˚C under conditions where the material had also been fully melted. This difference can be attributed to the effect of cooling rate on crystallization behavior. At slower rates, such as 5 ˚C/min, polymer chains have more time to align and form crystalline regions, resulting in a higher Tc. In contrast, faster cooling rates, such as 10 ˚C/min, reduce the time available for nucleation and crystal growth, leading to a lower Tc.

Using equation (1), the nucleation efficiency (NE) of each nucleating agent was quantified. The results are summarized in

Table 3 and illustrated in

Figure 5. The NE results revealed significant differences in performance among the tested nucleating agents, highlighting their varying abilities to enhance the crystallization behavior of P3HBHHx.

PHH_05BN and PHH_05PHB exhibited the highest NE values, at 46.2% and 42.8%, respectively. These results demonstrate their strong ability to promote nucleation, significantly increasing the number of effective crystallization sites during cooling. Their high efficiency suggests that BN and PHB facilitate early-stage crystal formation, allowing P3HBHHx to crystallize more rapidly and uniformly. Talc also demonstrated strong nucleation effects, particularly at a concentration of 2 wt%, where it reached an NE value of 40.2%, comparable to those of BN and PHB. This enhanced crystallization behavior is particularly beneficial in industrial processes such as injection molding, where reduced cycle times are essential.

In contrast, PHH_05UFC and PHH_05LAK exhibited considerably lower NE values, at 3.4% and 18.9%, respectively, indicating limited nucleating activity. These low values suggest that both ultrafine cellulose and the organic potassium salt provide insufficient nucleation sites to significantly influence the crystallization of P3HBHHx. While slight improvements in crystallization may still be observed, their overall impact remains minimal when compared to the more effective nucleating agents such as BN, PHB, and talc.

3.2. Structural Comparison of P3HBHHx with Different Nucleating Agents

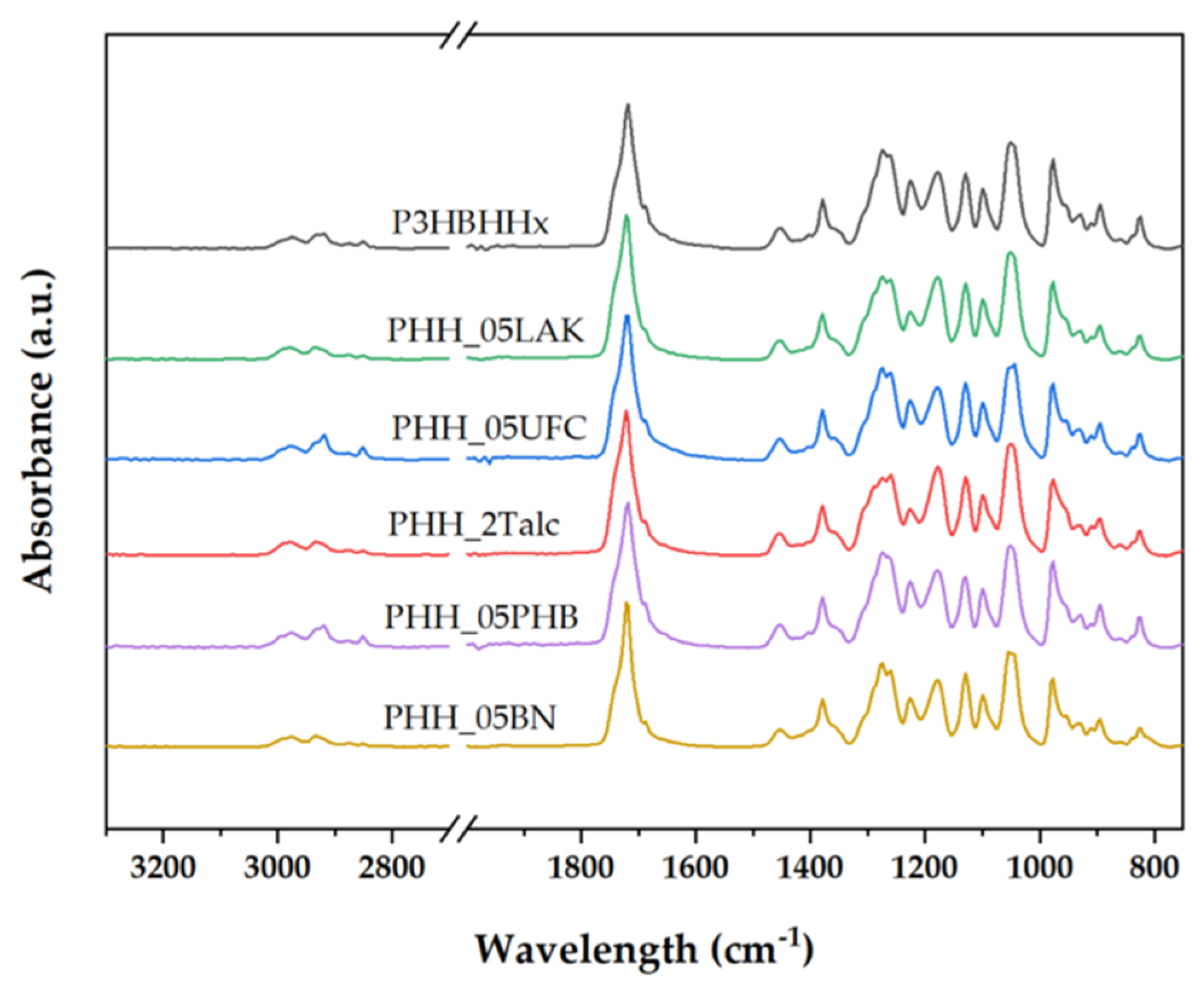

3.2.1. FTIR Analysis

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was used to assess whether the incorporation of nucleating agents induced any structural changes in P3HBHHx. As shown in

Figure 6, the characteristic absorption bands of P3HBHHx were preserved across all samples, regardless of the nucleating agent. These include the carbonyl stretching vibration (C=O) at approximately 1720 cm

-1 and the C-O stretching and bending vibrations in the range of 1300 ̶ 1050 cm

-1, which are associated with ester groups in the polymer backbone [

24]. The absence of new peaks, significant shifts, or changes in the fingerprint region further confirms that the molecular structure of P3HBHHx remained unaffected by the presence of the nucleating agents.

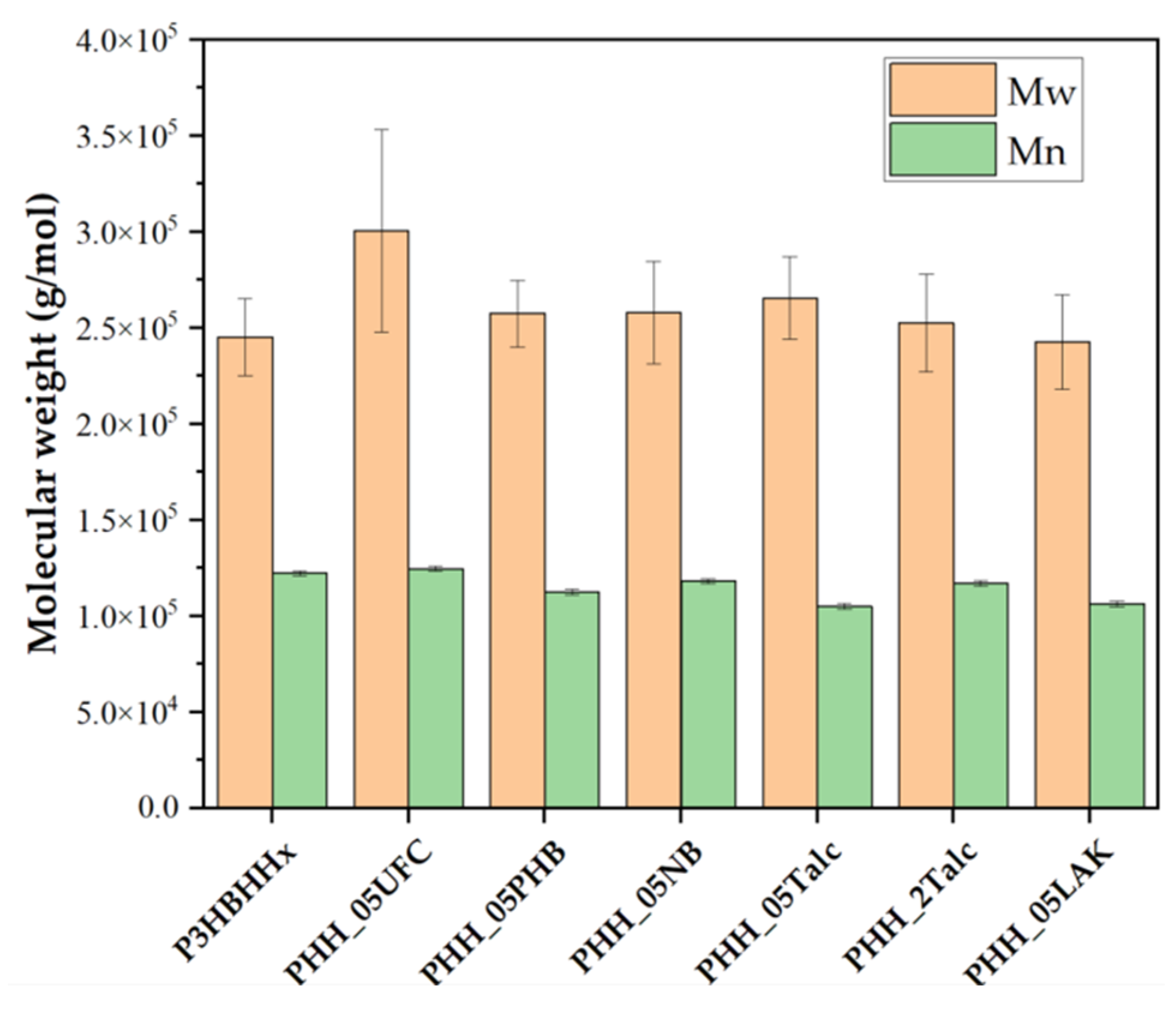

3.2.2. Degradation of Nucleated Samples During Processing

The potential degradation of P3HBHHx during the extrusion process in the presence of nucleating agents was evaluated by analyzing the molecular weight of the samples using gel permeation chromatography (GPC). As shown in

Figure 7 and summarized in

Table S2, both the weight-average (

Mw) and number-average (

Mn) molecular weights for most nucleated samples remained consistent with that of the neat P3HBHHx copolymer (

Mw = 245,280 g/mol;

Mn = 122,440 g/mol). This consistency indicates that the incorporation of nucleating agents does not lead to polymer degradation during extrusion.

An exception was observed in the sample containing ultrafine cellulose (PHH_05UFC), which exhibited a significant increase in

Mw to 300,520 g/mol, approximately 50,000 g/mol higher than that of the neat polymer. A slight increase in

Mn was also recorded (

Mn = 124,650 g/mol). This increase is not attributed to chemical modification but is likely due to physical interactions between the hydroxyl groups on the cellulose surface and the polymer matrix, which may promote chain entanglement during processing [

25]. This phenomenon appears to be specific to PHH_05UFC, as it was not observed in samples containing other nucleating agents, which lack surface functional groups capable of inducing such interactions.

Overall, these results demonstrate that most nucleating agents, when used at low concentrations, do not cause degradation of P3HBHHx during extrusion. This thermal and molecular stability is critical for industrial applications, as it ensures that crystallization performance can be enhanced without compromising the polymer’s structural integrity. As a result, the mechanical properties of the material are likely to be preserved, making these formulations suitable for a wide range of practical uses.

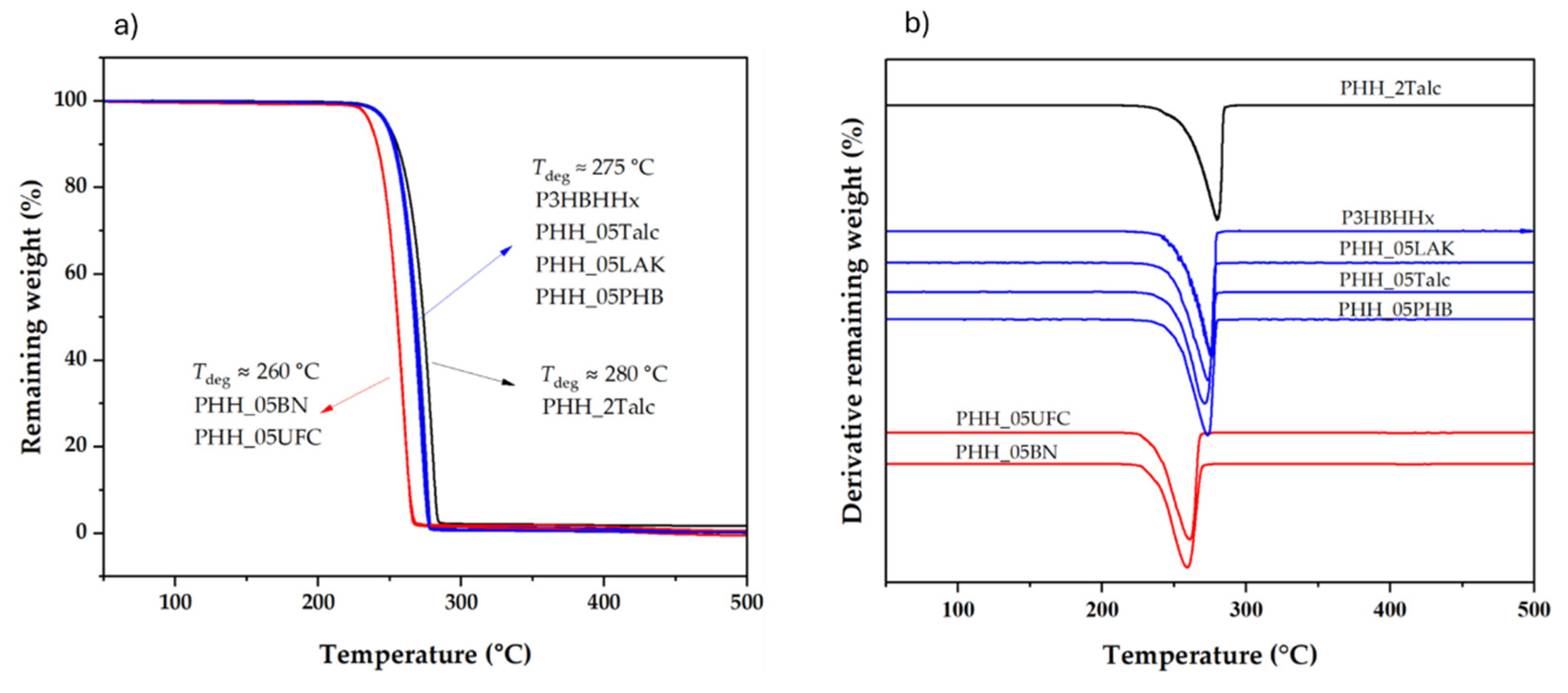

3.2.3. Influence of Nucleating Agents on the Thermal Stability of P3HBHHx

Figure 8 presents the results of TGA analysis, showing the remaining weight percentage of each sample as a function of temperature, along with the corresponding derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves. The temperatures at which 5%, 50%, and 90% weight loss occurred, as well as the residual mass at 450 ˚C, are summarized in

Table 4.

According to

Figure 8, nucleating agents such as PHB (PHH_05PHB) and LAK (PHH_05LAK) had minimal effect on the thermal stability of P3HBHHx, with differences in degradation temperature (

Tdeg) generally within 5 ˚C of the neat P3HBHHx. In contrast, boron nitride (PHH_05BN) and ultrafine cellulose (PHH_05UFC) lowered the degradation temperature peak from 275 ˚C to 260 ˚C. This reduction is likely due to specific thermal interactions between the nucleating agents and the polymer matrix. Boron nitride, known for its high thermal conductivity, may enhance heat transfer within the material, leading to localized heating and earlier onset of decomposition [

26]. Similarly, ultrafine cellulose introduces numerous hydroxyl groups, which can act as additional sites for thermal degradation. These groups are prone to hydrolysis, potentially accelerating the degradation process by initiating earlier thermal breakdown of the polymer chains [

27].

Talc exhibited a concentration-dependent effect on the thermal stability of P3HBHHx. At 0.5 wt% (PHH_05Talc), the degradation temperature peak remained at 271 ˚C, similar to that of neat P3HBHHx. However, increasing the concentration to 2 wt% (PHH_2Talc) significantly raised the degradation temperature to 280 ˚C, the highest among all tested samples. This improvement is likely related to the increased crystallinity observed at 2 wt% talc (

Figure 3), as crystalline regions are inherently more thermally stable than amorphous ones. These ordered domains require more energy to disrupt, which contributes to the elevated degradation temperature in the PHH_2Talc sample.

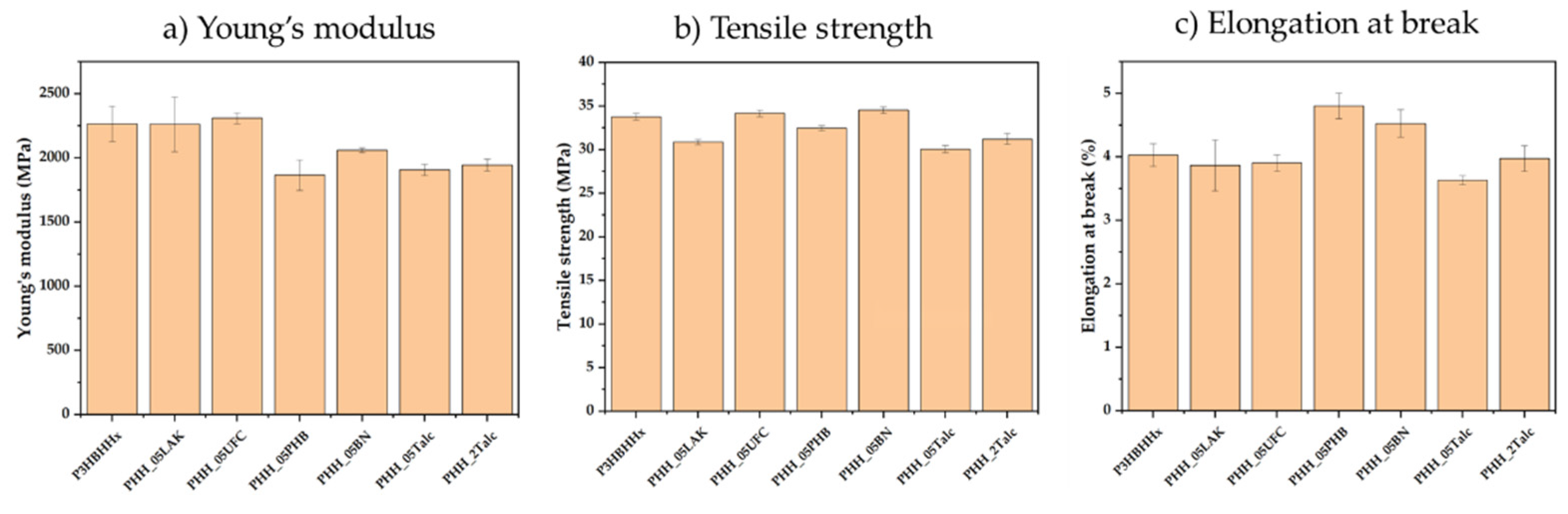

3.2.4. Mechanical Testing

Mechanical tests were conducted to assess the effect of nucleating agents on the mechanical properties of P3HBHHx. As shown in

Table 5 and

Figure 9, most nucleated samples maintained mechanical performance comparable to the neat polymer, with variations in Young’s modulus, tensile strength, and elongation at break generally within 10%. All specimens were injected in a mold set at 50 °C, allowing consistent crystallization across samples. However, as will be discussed later, heterogeneous nucleation introduced by the additives and homogeneous nucleation in the neat polymer result in different spherulite sizes due to their distinct induction time.

Specifically, samples with enhanced crystallization and higher nucleation efficiency, such as PHH_05PHB, PHH_05BN, and PHH_05Talc or PHH_2Talc, exhibited a more pronounced decrease in modulus, from 2264 MPa in the neat sample to values between 1866 and 2060 MPa, representing a reduction of up to 17%. These samples also showed a slight increase in elongation at break. This behavior is attributed to changes in crystalline morphology, particularly the formation of larger spherulites through heterogeneous nucleation, which result in reduced stiffness.

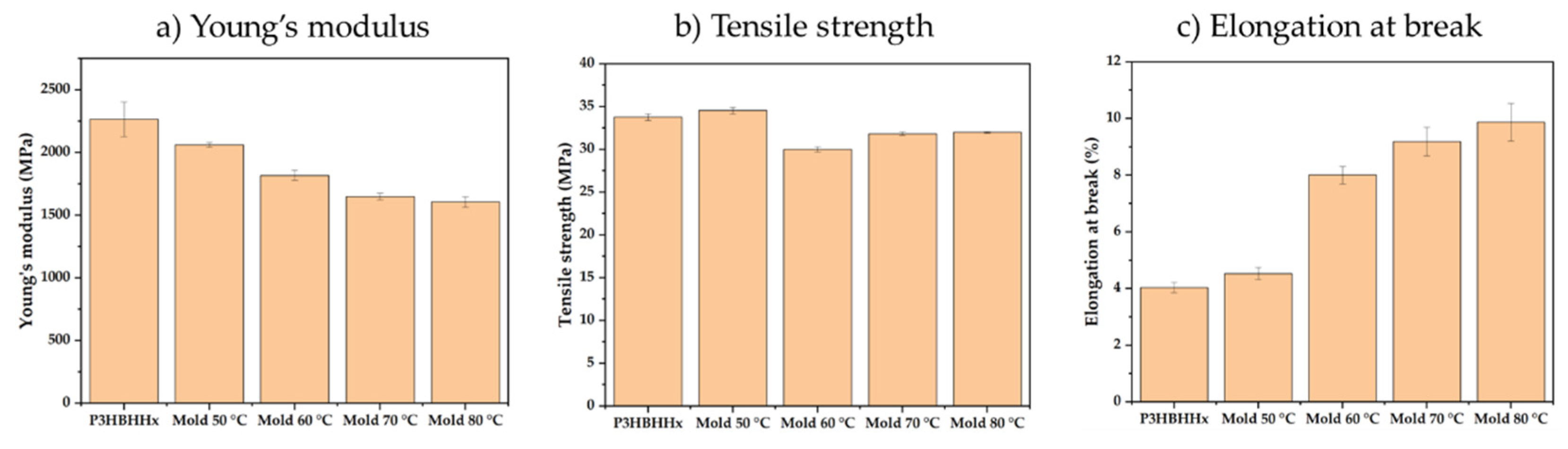

To further explore the influence of processing conditions, additional tests were conducted on PHH_05BN at different mold temperatures (50 °C, 60 °C, 70 °C, and 80 °C). As shown in

Figure 10, increasing the mold temperature led to a further decrease in stiffness, evidenced by lower modulus and higher elongation at break. This trend is consistent with the expected formation of larger spherulites in heterogeneously nucleated samples under slower cooling conditions.

These findings highlight the importance of considering the interplay between nucleating agents and processing parameters when optimizing the mechanical properties of P3HBHHx. While efficient nucleators improve crystallization kinetics and potentially reduce cycle time, their influence on crystalline morphology can affect stiffness. Therefore, achieving a balance between enhanced processability and acceptable mechanical performance is essential for industrial application.

3.3. Isothermal Crystallization and Kinetic Analysis

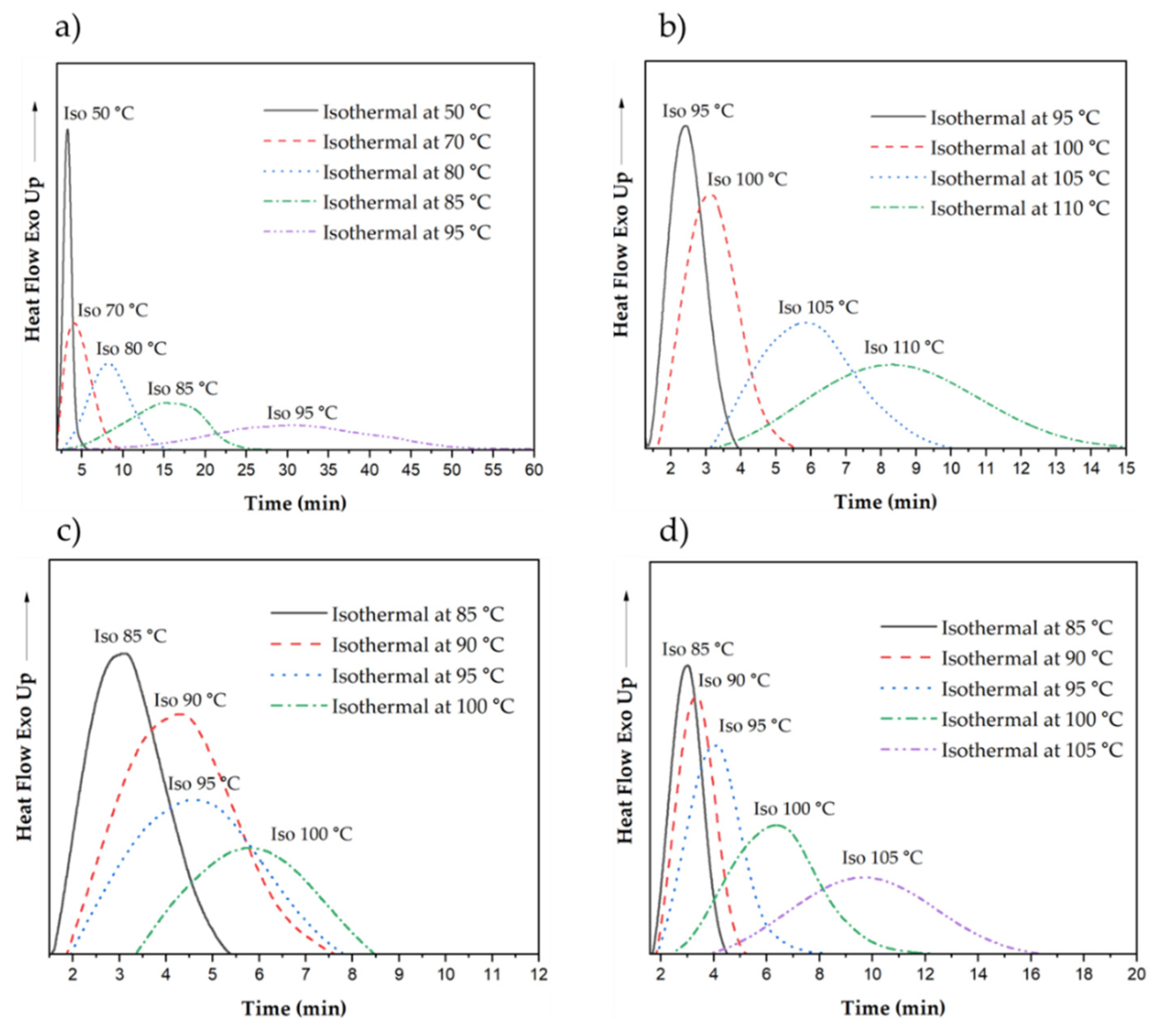

3.3.1. Crystallization of Neat and Nucleated P3HBHHx at Different Isothermal Temperatures

The non-isothermal DSC results identified boron nitride (BN) as the most effective nucleating agent for P3HBHHx, increasing the crystallization temperature (Tc) from 36.4 °C in the neat P3HBHHx to 84.1 °C. PHB and talc (2 wt%) also showed significant effects, increasing Tc to 81.9 °C and 72.6 °C, respectively. To further investigate crystallization behavior and kinetics, isothermal crystallization experiments were conducted at various temperatures for these samples.

Figure 11 presents the DSC exothermic peaks corresponding to the isothermal crystallization of neat and nucleated P3HBHHx samples. When the isothermal temperature closely approaches the crystallization temperature identified in the non-isothermal analysis, the crystallization peaks are sharp and well-defined, indicating rapid nucleation and crystal growth. In contrast, at higher isothermal temperatures, the peaks become broader and appear after longer induction times, reflecting a reduced thermodynamic driving force for crystallization and slower kinetics.

It is important to note that for reliable kinetic analysis, the selected isothermal temperature must enable full crystallization during the isothermal hold. For example, although crystallization of neat P3HBHHx (

Figure 11a) at 50 °C occurs rapidly with sharp and defined peak, the crystallization enthalpy determined was only 41.5 J/g (

Table 6), significantly lower than the 60.3 J/g measured at higher temperatures (80 °C and above). This suggests that a substantial portion of the material had already crystallized during the rapid cooling step prior to reaching the isothermal temperature. Consequently, this condition does not accurately reflect isothermal crystallization and is unsuitable for kinetic modeling.

The same criterion applies to the nucleated samples. For example, PHH_05BN required isothermal temperatures of 100 °C or higher to avoid partial crystallization during the cooling step. At this temperature, PHH_05BN exhibited significantly higher enthalpy values (64.3 J/g) compared to neat P3HBHHx (

Table 6), which can be attributed to the high nucleation sites density introduced by boron nitride, promoting the formation of well-ordered crystalline structures.

Both PHH_05PHB and PHH_2Talc also exhibited enhanced crystallization behavior, achieving complete crystallization at slightly lower isothermal temperatures than PHH_05BN. PHH_05PHB reached a stabilized enthalpy of approximately 60 J/g at 90 °C, while PHH_2Talc achieved a similar value at 95 °C. These results are comparable to the enthalpy observed for neat P3HBHHx but in significantly shorter crystallization times, confirming the effective nucleating capabilities of PHB and talc.

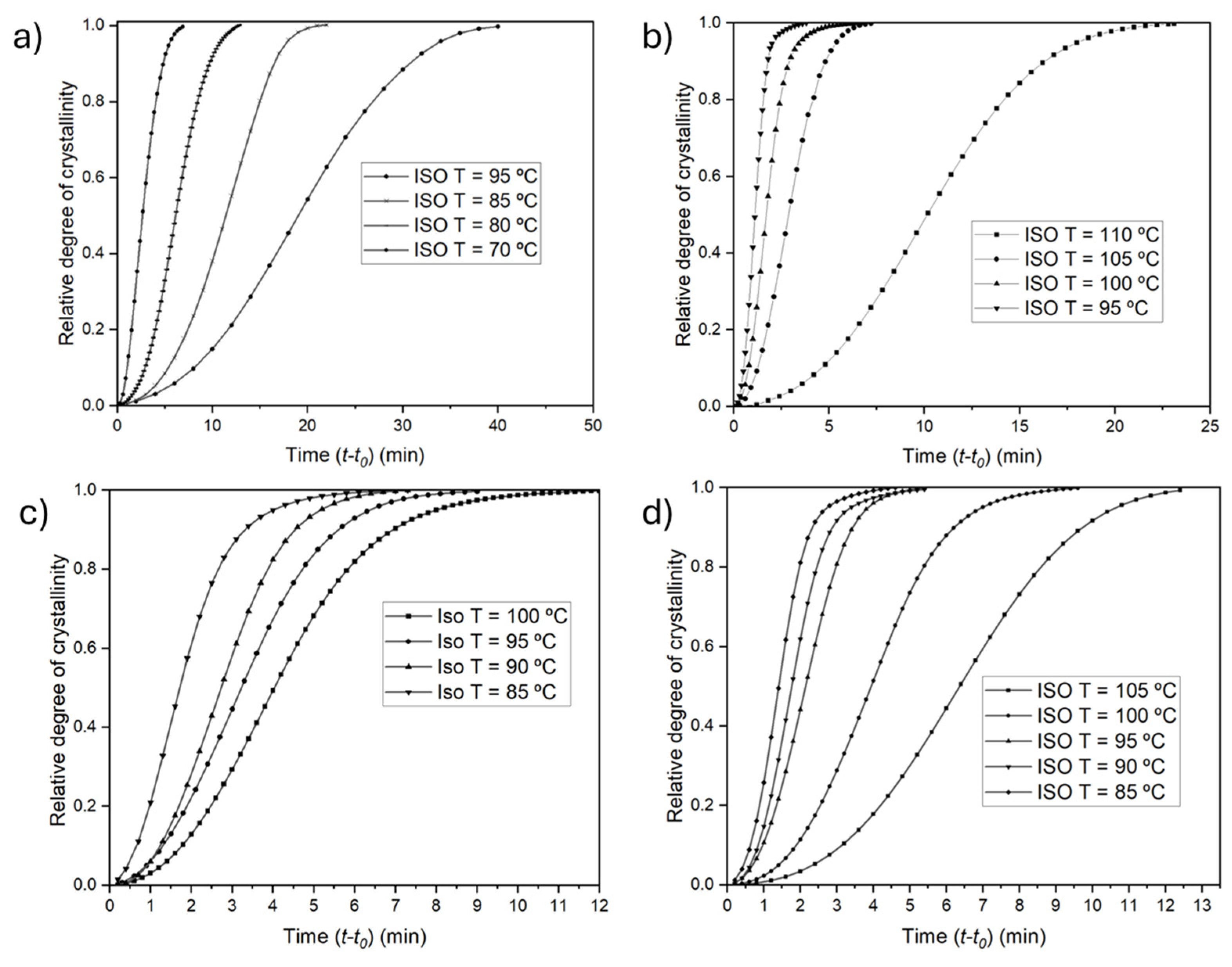

3.3.2. Evolution of the Relative Crystallinity over Time

To gain deeper insight into the crystallization kinetics of neat P3HBHHx and its nucleated variants, the evolution of relative crystallinity over time was analyzed at various isothermal temperatures, as shown in

Figure 12. The half-crystallization time (τ

1/2), defined as the time required to reach 50% relative crystallinity, was extracted from each curve, and the crystallization rate (

k) was calculated as its inverse. The corresponding values are summarized in

Table 6.

Only data obtained from isothermal conditions where full crystallization was achieved were considered valid for kinetic analysis. For neat P3HBHHx (

Figure 12a), valid data began at 80 °C, where τ

1/2 was 340 s, corresponding to a crystallization rate of 2.94 × 10⁻³ s⁻¹. As the isothermal temperature increased, the crystallization process became significantly slower, with τ

1/2 exceeding 1400 s at 95 °C.

The incorporation of BN (

Figure 12b) significantly reduced τ

1/2 to 99 s at 100 °C (

k = 10.05 × 10⁻³ s⁻¹), indicating high nucleation efficiency and rapid crystal growth. The crystallization curves were sharper and more symmetrical compared to the neat polymer, reflecting more uniform nucleation and faster crystallization process.

Similarly, PHB (PHH_05PHB,

Figure 12c) and talc (PHH_2Talc,

Figure 12d) also improved crystallization kinetics. At 90 °C, PHH_05PHB had a τ

1/2 of 165 s (

k = 6.06 × 10⁻³ s⁻¹), while PHH_2Talc crystallized even faster, with a τ

1/2 of 133 s (

k = 7.53 × 10⁻³ s⁻¹). The shape of the curves for both samples remained relatively sharp, especially at intermediate temperatures (85 – 95 °C), indicating effective nucleation. However, deduced rate constants were slightly lower than that of PHH_05BN, suggesting that while PHB and talc promote nucleation efficiently, they provide fewer active nucleation sites than boron nitride.

3.3.3. Avrami Modeling of Crystallization Kinetics

The Avrami equation was applied to model the isothermal crystallization kinetics of neat P3HBHHx and selected nucleated formulations. This approach provides quantitative insight into the nucleation mechanism and crystal growth dimensionality by evaluating the evolution of relative crystallinity over time. The relative crystallinity, χ(t − t₀), was calculated from the isothermal DSC exotherms using Equation (2):

where

dH/dt is the heat flow rate and

t0 is the induction time, defined as the time at which crystallization begins. This approach normalizes the area under the exothermic peak to the total crystallization enthalpy, enabling the determination of the crystallization degree as a function of time.

When plotted, the resulting curves exhibit a characteristic sigmoidal shape as shown in

Figure 12, which is typical of semi-crystalline polymers and reflects the distinct stages of nucleation and crystal growth [

28,

29]. These curves were fitted to the Avrami equation:

where

Z is the temperature-dependent crystallization rate constant and

n is the Avrami exponent, which provides insight into the nucleation mechanism and the dimensionality of crystal growth.

To facilitate comparison across systems, a normalized crystallization rate constant

k was calculated as:

This normalization ensures that k has consistent units of s-1, allowing for direct comparison across different nucleating agents and temperatures.

The crystallization half-time (τ

1/2) was calculated from:

Both Avrami exponent

n and the rate constant

Z were determined by plotting

against

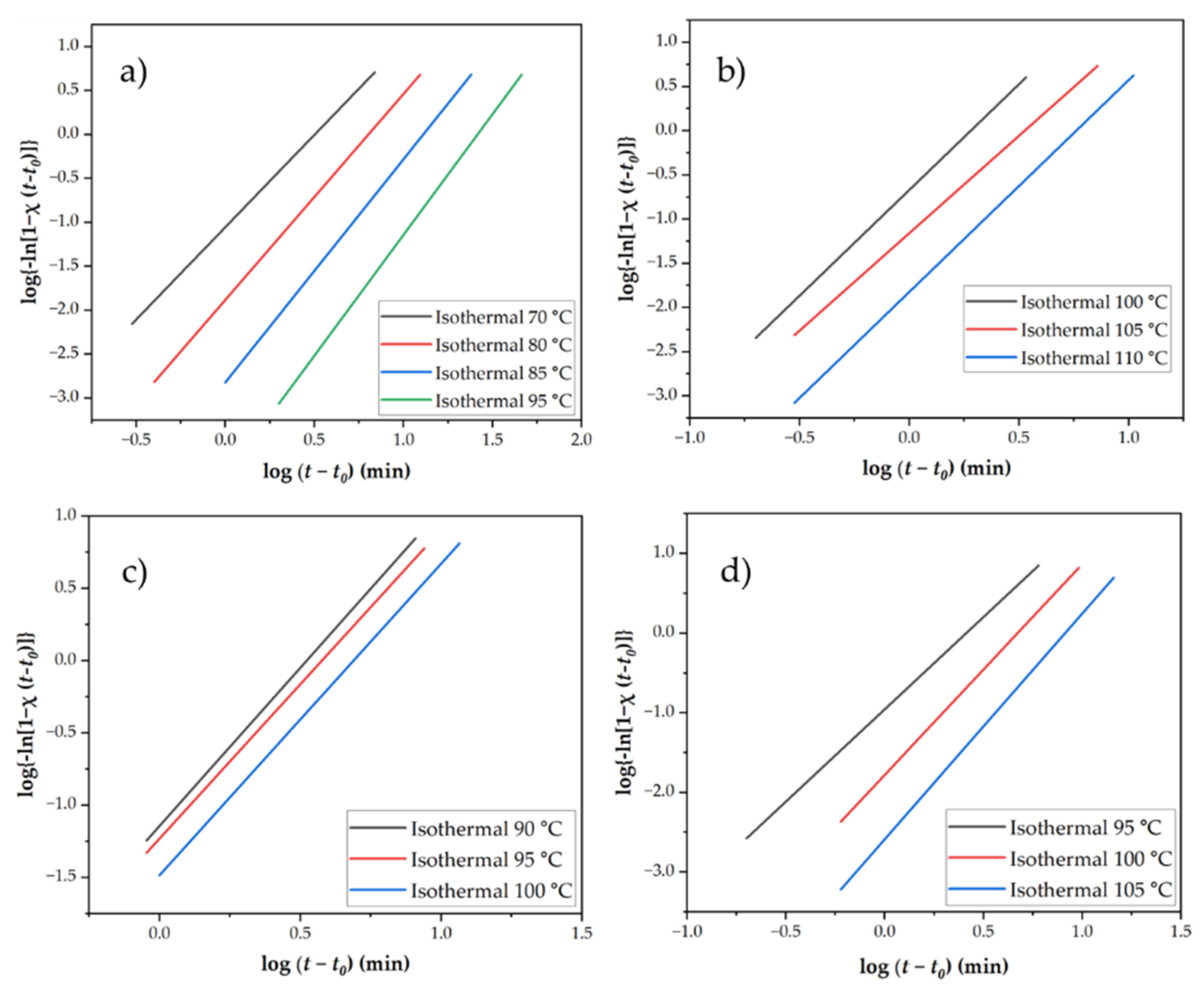

, which yielded linear fits as illustrated in

Figure 13. The kinetic parameters deduced from the Avrami analysis, including τ

1/2 and

k, are summarized in

Table 7.

3.3.4. Analysis of Avrami plots

The linearity of Avrami plots for neat P3HBHHx and nucleated samples across all tested isothermal temperatures confirms that the crystallization behavior follows the Avrami model with good approximation. The slope of each plot corresponds to the Avrami exponent (n), which provides insights into the nucleation mechanism and the dimensionality of crystal growth.

For neat P3HBHHx (

Figure 13a),

n ranged from 2.10 at 70 °C to 2.75 at 95 °C, suggesting tree-dimensional spherulitic growth with some degree of spatial confinement. These values are consistent with a combination of instantaneous and homogeneous nucleation, typically observed in systems with limited nucleation sites. The increase in

n with temperature suggests reduced spatial confinement, as fewer active nuclei form at higher temperatures, allowing larger spherulites to grow before impingement.

In the case of PHH_05BN (

Figure 13b),

n values remained relatively stable between 2.20 and 2.39 across the tested range (100 – 110 °C), suggesting a combination of instantaneous homogeneous nucleation and an additional heterogeneous nucleation induced by the additive. The steeper slopes of these plots compared to the neat polymer reflect a higher rate constant (

Z), confirming enhanced crystallization kinetics.

PHB (PHH_05PHB,

Figure 13c) and talc (PHH_2Talc,

Figure 13d) also improved the crystallization behavior of P3HBHHx. The Avrami exponent (

n) ranged from 2.06 to 2.29 for PHH_05PHB and 2.32 to 2.88 for PHH_2talc, indicating that the overall crystallization mechanism remained consistent with that of the neat polymer. In both cases, the crystallization rate constant was significantly higher than that of neat P3HBHHx, reflecting improved nucleation efficiency.

The crystallization rate constants followed the trend BN > PHB ≈ Talc > neat P3HBHHx. This observation is consistent with previous results from half-time and relative crystallinity analysis, reinforcing the conclusion that BN is the most effective nucleating agent for enhancing the crystallization of P3HBHHx.

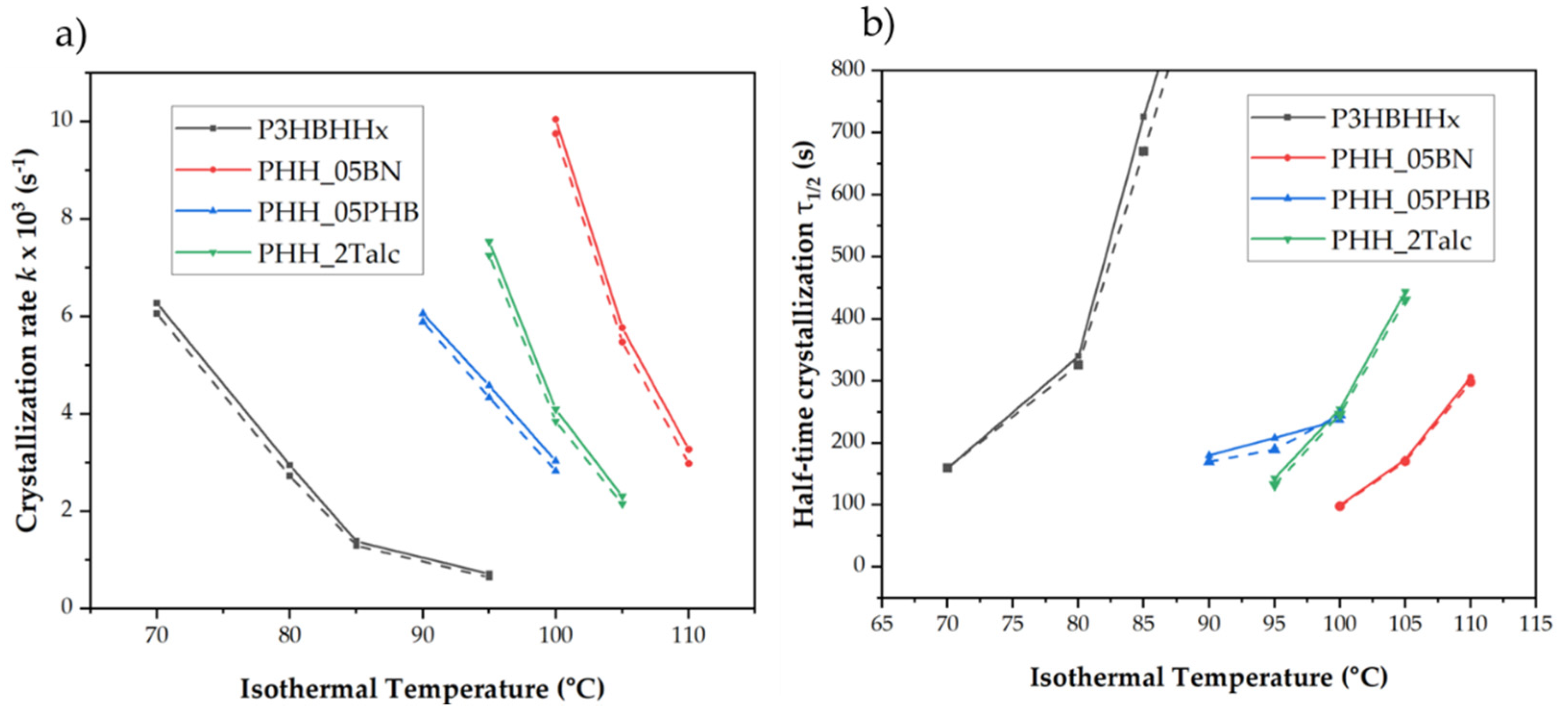

Figure 14 illustrates the validation of the Avrami model by comparing the experimental crystallization rates and half-crystallization time obtained from DSC measurements with the theoretical values predicted by the Avrami equation. The strong correlation between experimental and calculated data confirms that the crystallization behavior of both neat and nucleated P3HBHHx closely follows the Avrami model, with minimal deviations.

3.4. Spherulitic Morphology and Crystal Growth of P3HBHHx Samples

3.4.1. Spherulitic Morphology

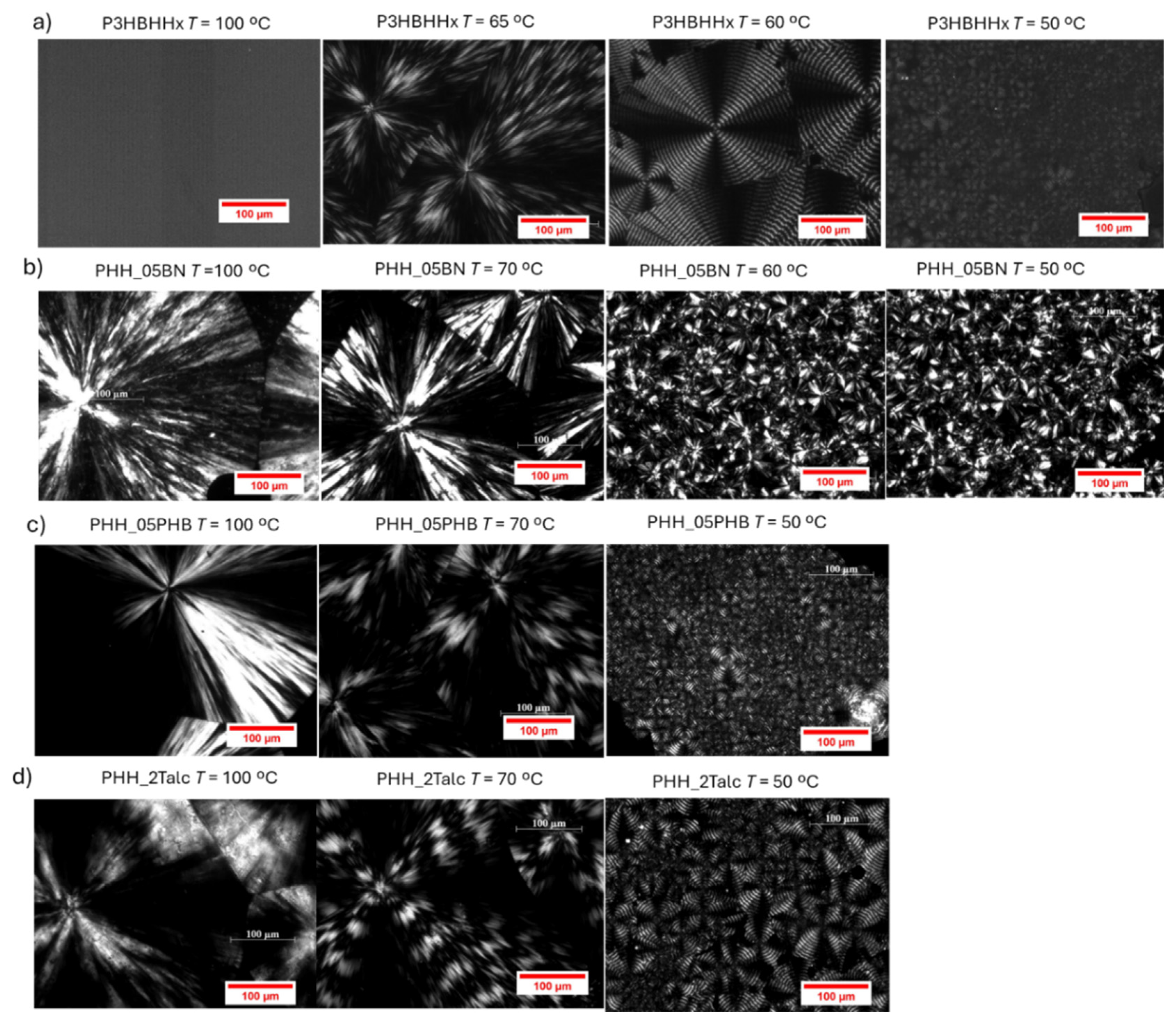

The spherulitic morphology of neat P3HBHHx and nucleated samples was examined at various isothermal temperatures using polarized optical microscopy (POM). Representative micrographs are shown in

Figure 15, highlighting significant differences in morphology and nucleation density among the samples.

For neat P3HBHHx (

Figure 15a), no spherulites were observed at temperatures above 65 °C, even after prolonged observation (e.g., approximately 30 minutes at 70 °C). The absence of crystalline structures demonstrates the difficulty of forming homogeneous primary nuclei, which require significant supercooling to initiate. At 65 °C, large spherulites with extensive radial growth appeared, although the density of primary nuclei remained low. These spherulites exhibited coarse textures with irregular Maltese-cross patterns, indicative of non-uniform lamellar packing likely caused by variations in lamellar orientation and thickness [

30].

At 60 °C, the spherulites began to display regular banding, indicating a transition in the crystallization mechanism. This banded structure is associated with periodic twisting of lamellae during radial growth [

31], and the resulting birefringence contrast between edge-on and flat-on lamellae leads to the observed alternating bright and dark rings. Surface stresses have been proposed to drive this twisting behavior [

32,

33,

34]. At 50 °C, the morphology remained banded, but the spherulite size decreased and nucleation density increased markedly, resulting in a dense arrangement of small, banded spherulites.

For the nucleated samples (

Figure 15b–d), spherulites were observed even at elevated temperatures such as 100 °C, indicating that heterogeneous crystallization was effectively promoted by the incorporated nucleating agents. At this temperature, the morphology was characterized by coarse textures and irregular Maltese-cross patterns, similar to the neat P3HBHHx at 65 °C. As the isothermal temperature decreased, nucleation density increased, leading to the formation of finer, more densely packed spherulites with banded structures. This morphology results from the combined effects of heterogeneous nucleation induced by the additives and the homogeneous nucleation inherent to the neat polymer at high degrees of supercooling.

Interestingly, the nucleation density in the nucleated samples was lower than in the neat polymer, resulting in the formation of larger spherulites. Polarized optical micrographs revealed the coexistence of two spherulitic populations: larger spherulites attributed to rapid heterogeneous nucleation and smaller ones associated with slower homogeneous nucleation. In particular, PHH_05BN samples continued to exhibit irregular Maltese-cross patterns even at lower temperatures, suggesting a distinct crystallization mechanism that may be influenced by specific interactions between boron nitride and the P3HBHHx matrix.

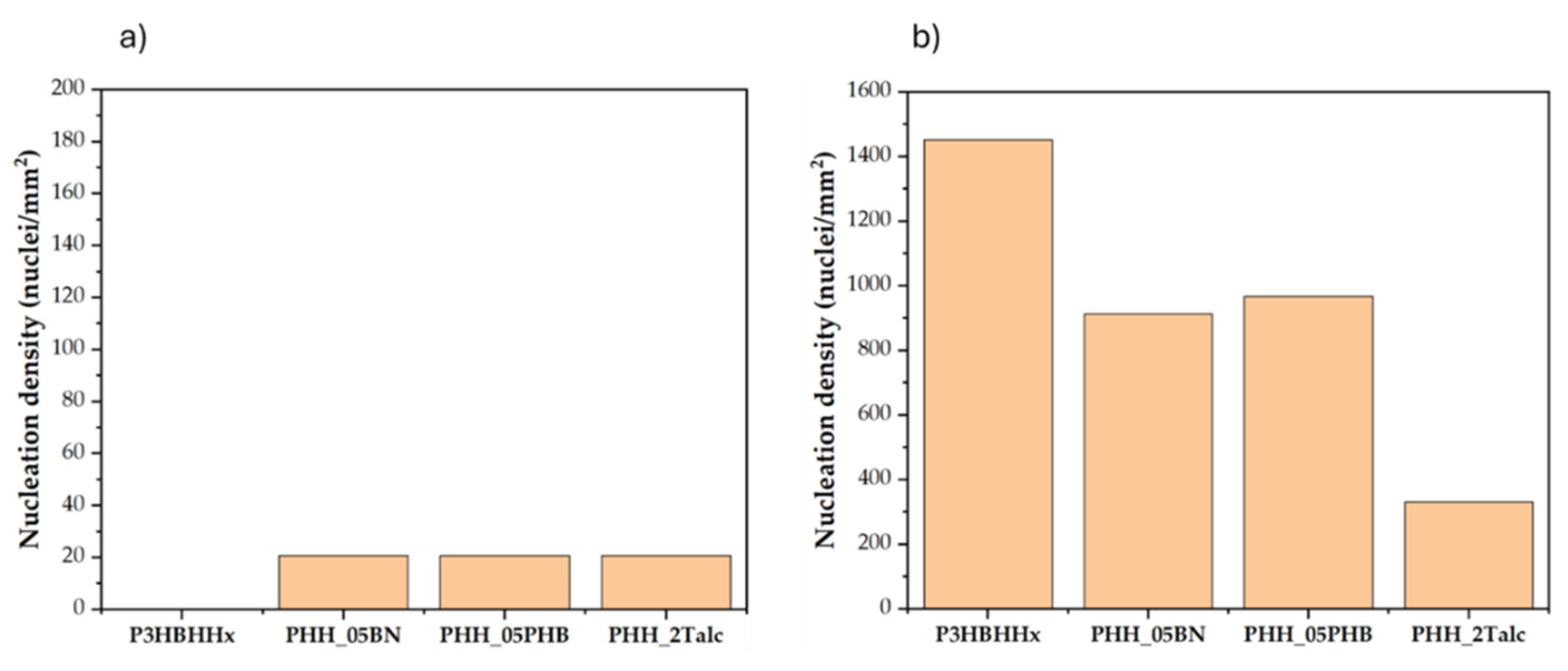

3.4.2. Nucleation Density

Figure 16 presents the nucleation density of neat P3HBHHx and nucleated samples at low (50 °C) and high (100 °C) isothermal crystallization temperatures. At 100 °C, spherulites were only observed in the nucleated samples, with nucleation densities around 20 nuclei/mm². This density was similar for all these samples since similar concentration of the nucleating agent was incorporated (0.5 or 2 wt%), which remained active even at elevated temperatures. At 50 °C, the nucleation density increased significantly in all samples due to the combined effects of heterogeneous and homogeneous nucleation. For example, PHH_05BN exhibited a sharp rise in nucleation density from approximately 20 to 850 nuclei/mm². This increase is attributed to the earlier activation of heterogeneous nucleation sites introduced by boron nitride, followed by homogeneous nucleation as supercooling progressed. In contrast, PHH_2Talc exhibited a lower nucleation density under the same conditions, suggesting that the homogeneous nucleation process was slightly hindered by the presence of the added inorganic particles.

Interestingly, at 50 °C, neat P3HBHHx exhibited a high nucleation density, reaching approximately 1440 nuclei/mm2. This high value is attributed entirely to homogeneous nucleation, which becomes increasingly favorable at low temperature due to higher degrees of supercooling. However, in nucleated samples, early formation of heterogeneously nucleated spherulites likely reduced the available material/space for homogeneous nucleation to proceed, resulting in overall lower densities.

Above 65 °C, no nuclei were detected in neat P3HBHHx, confirming that homogeneous nucleation becomes ineffective due to the increased energy barrier for primary nucleation at higher temperatures. In contrast, nucleated samples still displayed measurable nucleation densities at 100 °C, demonstrating that the additives significantly lower the energy barrier required for nucleation. This ability to promote nucleation at elevated temperatures confirms that the nucleating agents provide energetically favorable sites for stable nucleus formation.

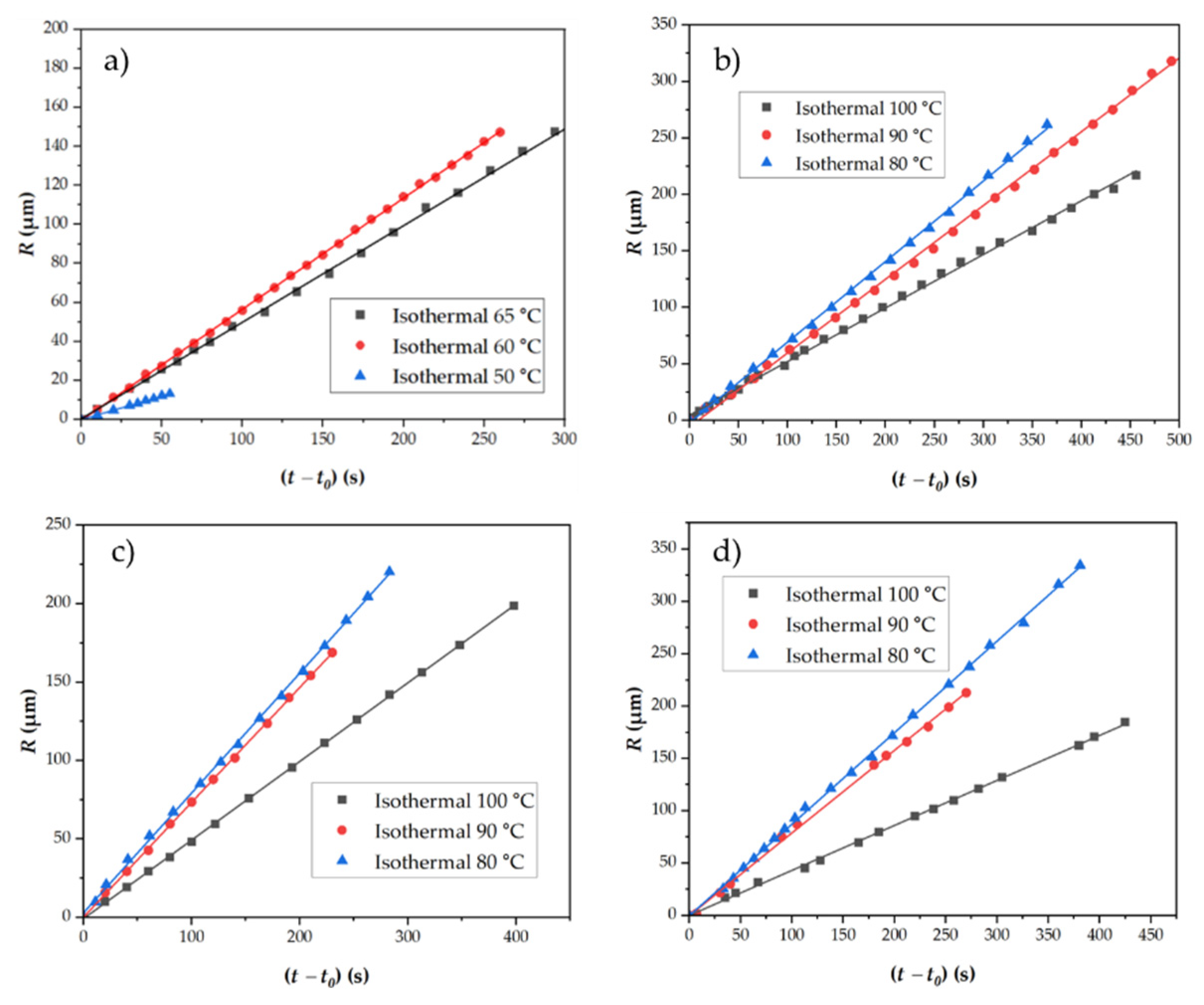

3.4.3. Crystal Growth Rates Determined from POM

The crystal growth rates (

G) of neat P3HBHHx and nucleated samples at different crystallization temperatures were determined using polarized optical microscopy (POM) by measuring the increase in spherulite radius over time. The slopes obtained from the linear correlations of radius versus crystallization time (

Figure 17) were used to calculate the growth rates, which are summarized in

Table 8.

For neat P3HBHHx, the maximum growth rate was observed at 60 °C, with a G value of 0.57 µm/s, suggesting that this temperature offers an optimal balance between polymer chain mobility and the efficiency of secondary nucleation. In contrast, the nucleated samples exhibited their maximum growth rates at higher temperatures, around 80 °C. This shift indicates that the presence of nucleating agents enhances nucleation efficiency, allowing effective crystal growth to occur at elevated temperatures compared to the neat polymer.

Among the tested formulations, PHH_2Talc exhibited the highest crystal growth rate, reaching 0.87 µm/s at 80 °C. Interestingly, this result differs from the trends observed in DSC-based crystallization data, where PHH_05BN showed the fastest overall crystallization rate. This discrepancy demonstrates the different aspects of crystallization captured by POM and DSC techniques. In DSC, the measured crystallization rate reflects a combination of primary nucleation (formation of stable nuclei) and the crystal growth from the existing nuclei. In contrast, POM focuses solely on the crystal growth at each temperature, which is directly related to secondary nucleation mechanisms rather than the initial nucleation events.

These findings suggest that while boron nitride excels at initiating crystallization (primary nucleation), talc is more effective at promoting crystal growth (secondary nucleation) once nuclei are present. As a result, talc shows a higher growth rate in POM, but boron nitride remains superior in accelerating the overall crystallization process as captured by DSC.

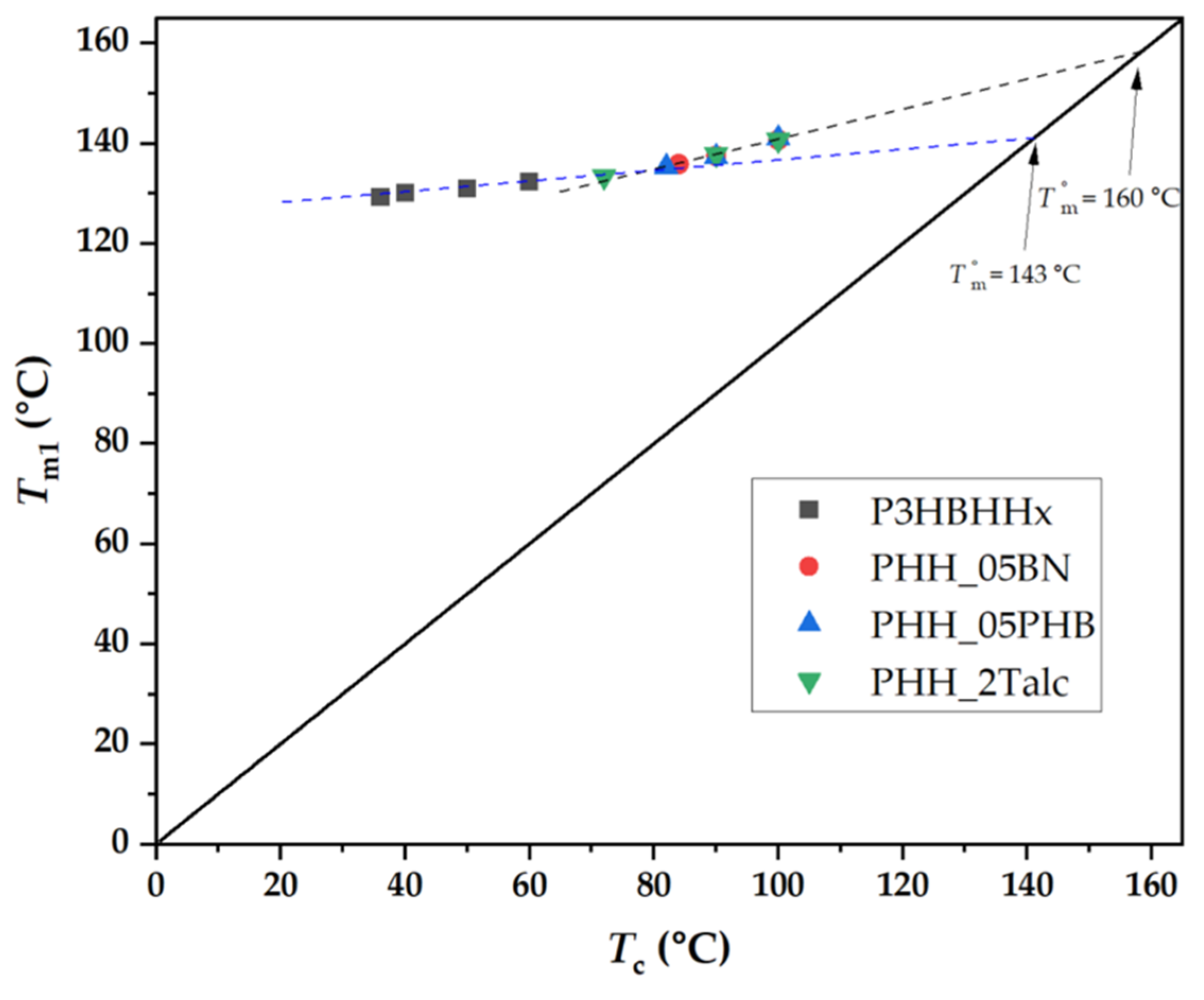

3.4.4. Determination of Equilibrium Melting Temperature ()

Figure 18 presents the equilibrium melting temperatures (

) of neat P3HBHHx and its nucleated samples, determined from the first melting peak and using the Hoffman–Weeks method. This approach involves plotting the melting temperature (

Tm) as a function of the corresponding crystallization temperature (

Tc) and extrapolating the linear fit to the point where

Tm equals

Tc. The intercept represents the equilibrium melting temperature (

), which defines the temperature at which the crystalline and melt phases can coexist.

For neat P3HBHHx, the extrapolation process may introduce intrinsic error due to the significant difference between the highest accessible melting temperatures and the actual . This discrepancy can lead to an underestimation of for neat P3HBHHx (143 °C), as the limited range of higher temperature data may bias the linear fit.

In contrast, the presence of nucleating agents enables crystallization at higher temperatures, being possible to get data at higher temperatures (i.e., closer to the real equilibrium temperature) and therefore decreasing the inherent error associated with the extrapolation.

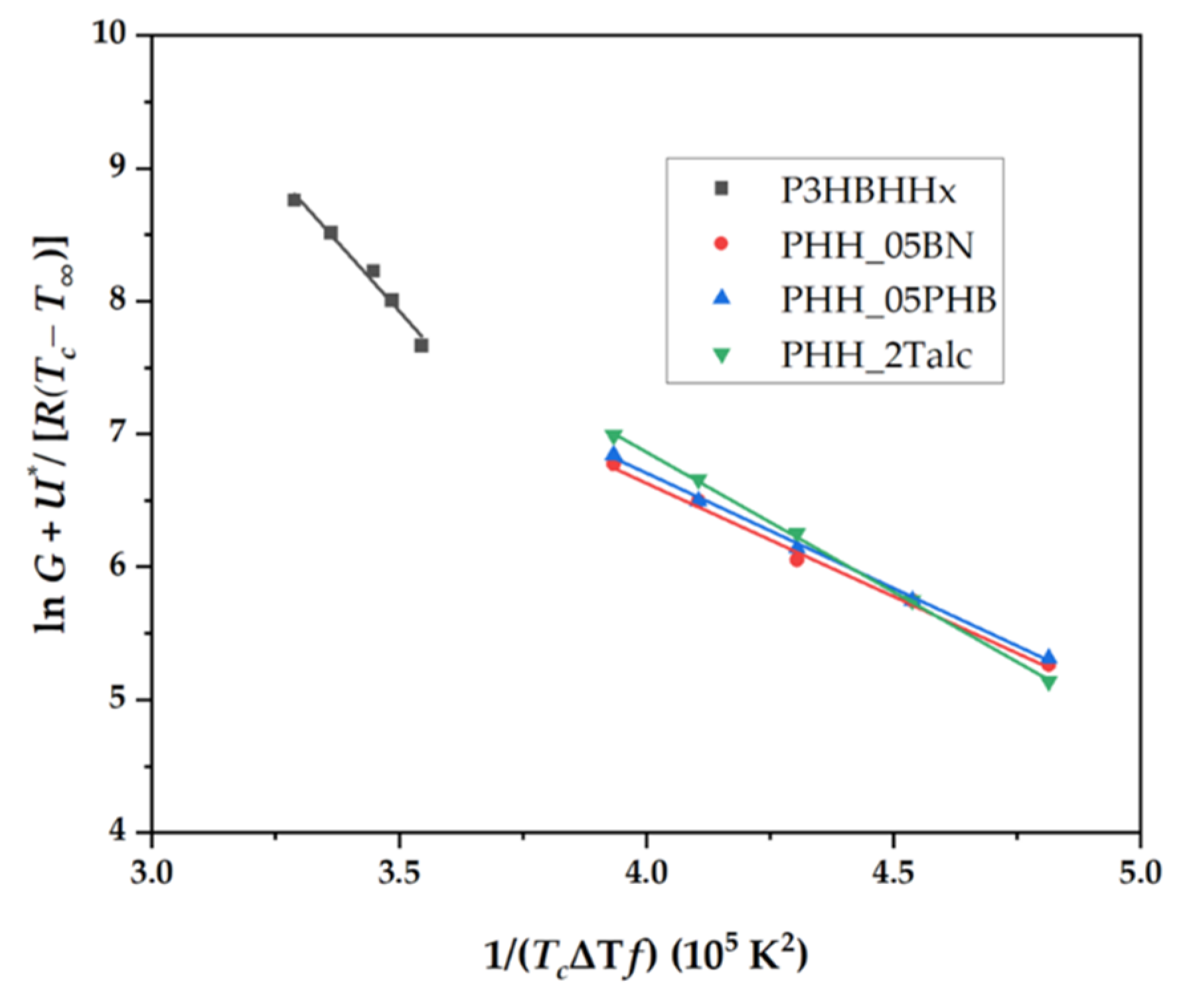

3.4.5. Kinetic Analysis Based on the Lauritzen-Hoffman Model

The crystal growth rate (

G) of neat P3HBHHx and nucleated samples can be simulated using the Lauritzen-Hoffman (LH) theory, which describes polymer crystallization kinetics by considering secondary nucleation together with molecular transport as rate-determining steps [

35,

36,

37]. This model provides insight into the activation energy and nucleation barrier controlling the crystallization process.

The Lauritzen-Hoffman equation expresses the growth rate

G as:

where

G0 is the pre-exponential factor related to molecular mobility;

U* is the activation energy for segmental motion above the glass transition temperature;

R is the universal gas constant;

Tc is the crystallization temperature;

is the reference temperature, typically approximated as

Tg ̶ 30 K;

Kg is the nucleation constant, which accounts for the energy barrier of secondary nucleation;

is the supercooling (the difference between the equilibrium melting temperature

and the crystallization temperature

Tc);

f is a correction factor for temperature dependence, given by :

To determine

Kg and validate the applicability of the LH model, experimental spherulitic growth rates obtained from POM observations were analyzed. The data were plotted according to the LH equation as:

In such calculations, it is common to adopt the “universal” values reported by Suzuki and Kovacs [

38], namely

U* = 1500 cal/mol and

=

Tg − 30 K. At low supercooling conditions (i.e., when

is small), crystallization kinetics are primarily governed by the nucleation term. As a result, the overall growth rate becomes relatively insensitive to variations in the

U* and

, allowing for reliable fitting of the Lauritzen-Hoffman (LH) model using these standard values.

As shown in

Figure 19, the LH plots for all samples exhibit strong linearity, with correlation coefficients (

R²) exceeding 0.99. The secondary nucleation constant

Kg was determined from the slope of the linear fits, and the results are summarized in

Table 9. This high degree of linear correlation supports the applicability of the LH model to describe the crystallization kinetics of both neat and nucleated P3HBHHx.

Two distinct slopes can be observed in

Figure 19,

one corresponding to neat P3HBHHx and the other to the nucleated samples. This distinction suggests that crystallization proceeded in different kinetic regimes: regime III for the neat polymer and regime II for the nucleated samples, due to the different temperature ranges used in each case. In regime III, typical of lower crystallization temperatures, crystal growth is governed by isolated nucleation events that results in higher Kg values. Conversely, in regime II, which occurs at higher crystallization temperatures, crystal growth is characterized by prolific multiple nucleation with a niche separation similar than the stem width, leading to lower Kg values.

For neat P3HBHHx, the highest Kg value was obtained (4.10 x 105 K2), consistent with its crystallization occurring at lower temperatures within regime III. In contrast, nucleated samples crystallized at higher temperatures, consistent with regime II, and exhibited lower Kg values, averaging around 2.0 x 105 K2. The findings are in agreement with the Lauritzen-Hoffman theory, which predicts a Kg ratio close to 2 between regime III and II.

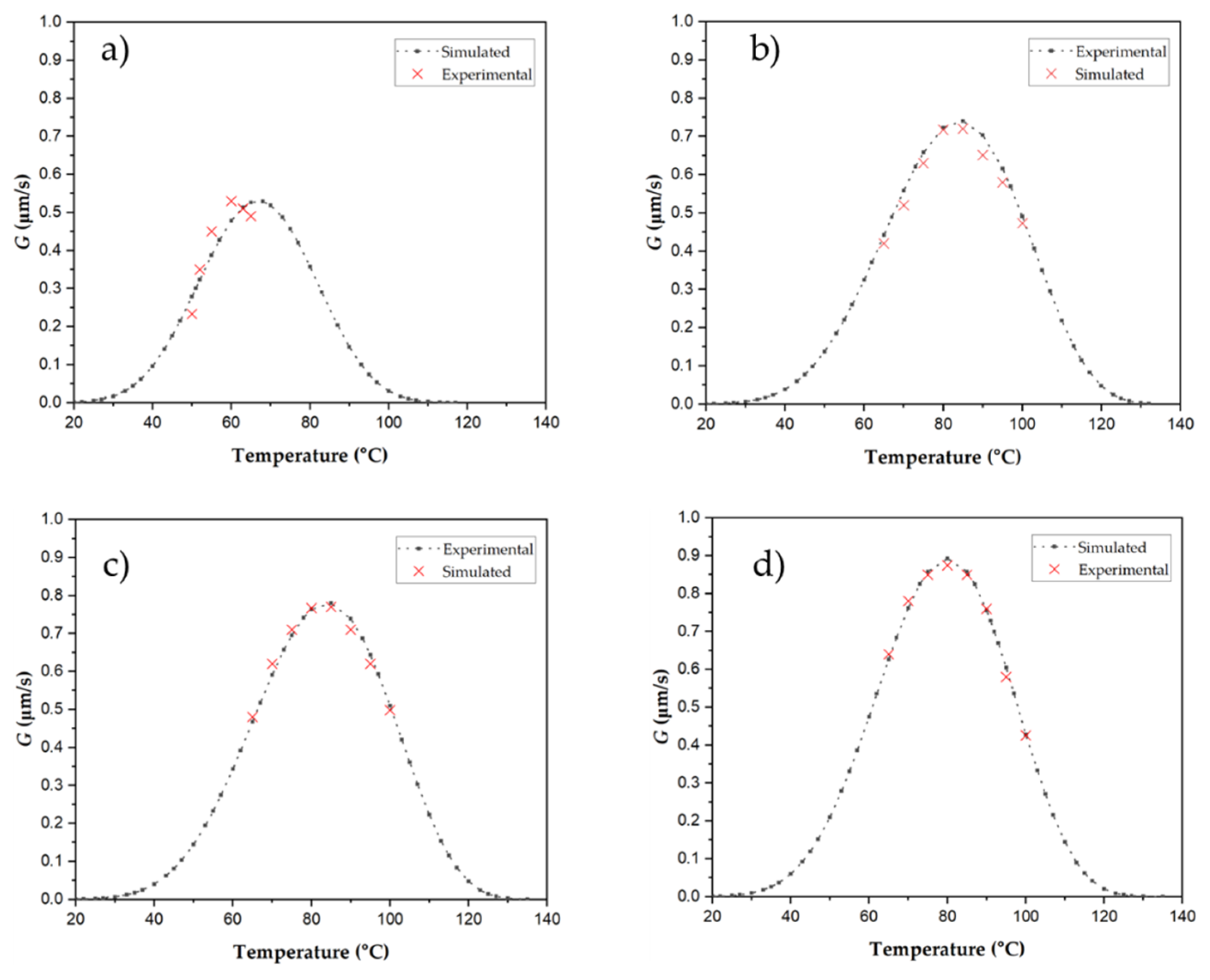

Figure 20 illustrates the simulated dependence of the crystal growth rate (

G) on crystallization temperature for neat P3HBHHx and its nucleated samples, based on Equation (6) and the corresponding parameters derived from LH model. The simulated curves exhibit the characteristics of bell-shaped profile typical of polymer crystallization, reflecting the competing effect of chain mobility and nucleation barriers. The maximum growth rate for neat P3HBHHx is predicted near 65 °C, whereas for the nucleated samples, the optimal crystallization temperature shifts to approximately 80-85 °C. This shift confirms that nucleation agents enhance cystallization kinetics at higher temperatures taking also profit of the decrease of the energy barrier for secondary nucleation. Note that there is also a slight shift between predicted and experimental temperatures for the maximum growth rate of the neat polymer. This feature should be a consequence of employing standard

U* and

T∞ values without performing additional refinement.

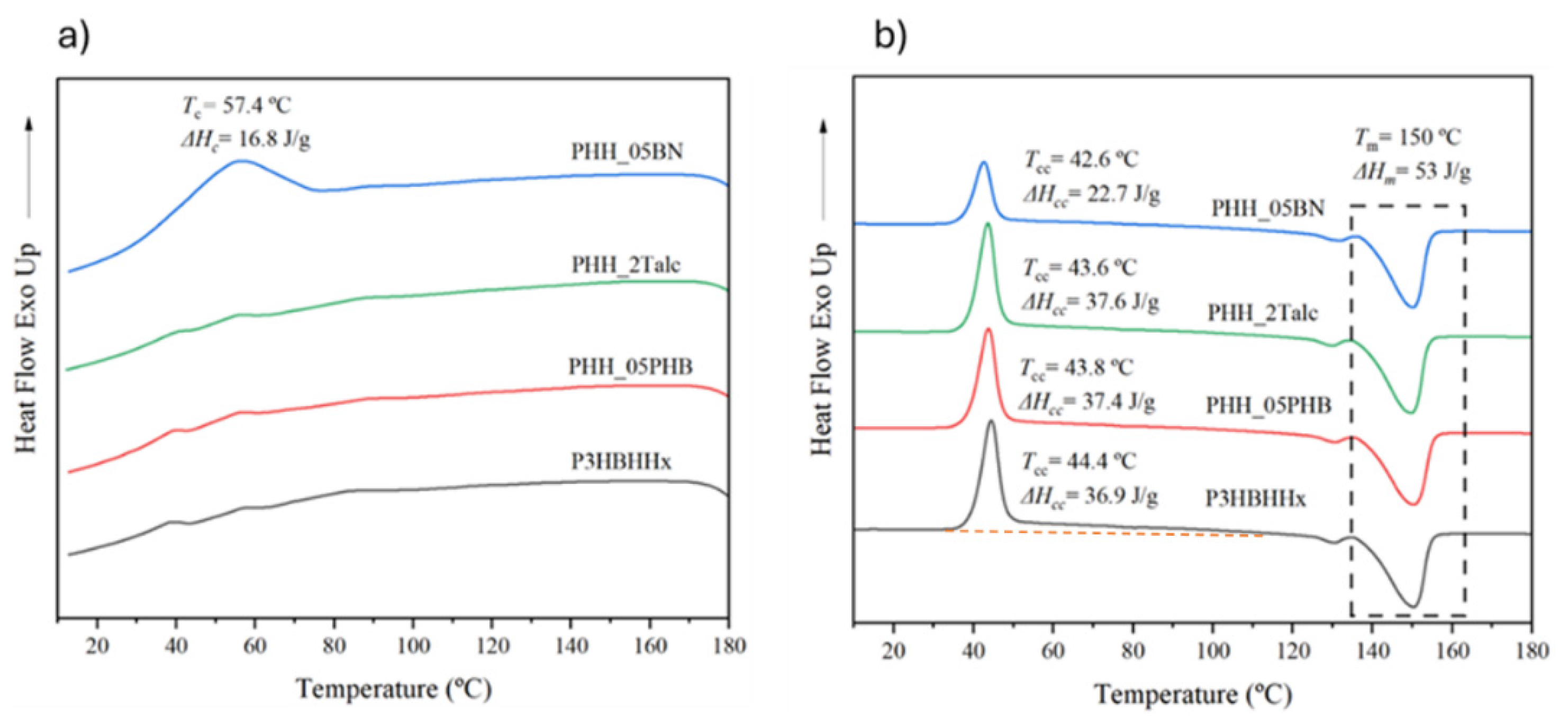

3.5. Fast Cooling Behavior of P3HBHHx and Nucleated Samples

Figure 21 shows the DSC thermograms of P3HBHHx samples with different nucleating agents during fast cooling (100 °C/min) and subsequent reheating (10 °C/min). This experiment was designed to evaluate the influence of rapid cooling on the crystallization behavior of P3HBHHx by comparing crystallization temperatures and enthalpies across the samples.

During the fast-cooling step, only the sample containing boron nitride (PHH_05BN) exhibited a crystallization exotherm, with a peak at 57.4 °C and an associated enthalpy of 16.8 J/g. This result confirms that BN substantially enhances nucleation efficiency, even under high cooling rates. However, the relatively low enthalpy suggests that while nucleation is initiated, crystal growth is limited due to the insufficient time available during rapid cooling, resulting in partial crystallization.

In contrast, neat P3HBHHx, PHH_05PHB, and PHH_2Talc did not show any exothermic peaks during cooling, indicating that crystallization was not triggered under these conditions. This suggests that while PHB and talc are effective at promoting crystallization under moderate cooling rates, they are not sufficiently active to induce nucleation during fast cooling at 100 °C/min.

Upon reheating (

Figure 21b), all samples exhibited a cold crystallization peak, confirming that most of the crystallization occurred during this second step. The cold crystallization temperatures (

Tcc) ranged from 42.6 °C to 44.4 °C, with PHH_05BN showing the lowest

Tcc. The cold crystallization enthalpies (

ΔHcc) ranged from 22.7 to 37.6 J/g, reflecting the extent of crystallization that occurred during reheating. Surprisingly, the total cold crystallization enthalpy was approximately 20 J/g lower than the melting enthalpy (approximately 53 J/g for all samples; see dashed zone in

Figure 21b). This discrepancy suggests that full crystallization was only achieved during the high temperature ramp (see dashed line in

Figure 21), likely due to kinetic limitations, restricted chain mobility, or the inability of certain amorphous domains to reorganize into crystalline structures.

Despite the differences in crystallization behavior, all samples, including the neat polymer, exhibited a melting peak around 150 °C with similar melting enthalpies (~53 J/g). This consistent melting temperature confirms that the addition of nucleating agents does not alter the fundamental crystalline structure of P3HBHHx, reinforcing that their primary role is to influence crystallization kinetics.

3.6. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the effect of various nucleating agents on the crystallization behavior, thermal stability, and mechanical properties of P3HBHHx. The incorporation of boron nitride (BN), poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), talc, and other nucleating agents significantly enhanced the crystallization kinetics of P3HBHHx, demonstrating their potential for improving the processability of this biopolymer.

From non-isothermal crystallization studies, BN and PHB were identified as the most effective nucleating agents. These agents facilitated faster and more complete crystallization during cooling, eliminating the need for cold crystallization upon reheating. Talc exhibited moderate nucleation efficiency when 0.5 wt% was employed. The effectiveness of talc increased to a comparable extent to BN and PHB when 2 %wt was used. In contrast, ultrafine cellulose (UFC) and organic potassium salt (LAK) showed limited impact on enhancing crystallization.

Isothermal crystallization studies further validated the role of BN, PHB and talc in accelerating crystallization kinetics. The Avrami analysis revealed that these nucleating agents significantly reduced the crystallization half-time (τ1/2) and increased the crystallization rate constant (k), indicating enhanced nucleation efficiency. The Avrami exponent remained in the range typical for three-dimensional spherulitic growth, with slight variations reflecting differences in nucleation mechanisms across formulations.

The Lauritzen-Hoffman model accurately predicted the crystal growth behavior of P3HBHHx and its nucleated samples across a wide temperature range. The secondary nucleation constants (Kg) derived from the model confirmed that the neat polymer crystallized in regime III, while nucleated samples crystallized in regime II at higher temperatures. These kinetic regimes explain the shift in optimal crystallization conditions and the high crystal growth rates observed for nucleated samples despite their crystallization occurring at elevated temperatures.

Fast cooling studies provided additional insights into the crystallization behavior under industrially relevant conditions. Among all nucleating agents, only BN induced crystallization during rapid cooling (100 °C/min), whereas all other samples, including neat P3HBHHx, remained amorphous and crystallized only upon reheating. The incomplete crystallization observed in all samples, evidenced by a lower total crystallization enthalpy compared to melting enthalpy, suggests that kinetic limitations restrict full crystallization.

Thermal stability analysis via TGA revealed that most nucleating agents had a minimal impact on degradation temperatures, except for BN and UFC, which slightly reduced the onset of degradation, likely due to their intrinsic thermal properties. In contrast, talc exhibited a concentration-dependent improvement in thermal stability, increasing the degradation temperature at higher loadings due to its barrier effect and enhancement of crystallinity.

Mechanical testing demonstrated that nucleating agents did not significantly alter the tensile strength or elongation at break of P3HBHHx. However, BN, PHB, and talc led to a moderate reduction in modulus and a slight increase in elongation at break, likely due to the development of larger spherulites resulting from faster nucleation and lower induction times.

Overall, this study provides a comprehensive evaluation of nucleating agents for P3HBHHx, highlighting BN as the most effective additive for enhancing active nuclei sites at high temperature. Whilst talc hinders the homogeneous nucleation and gives rise to larger spherulites. These findings offer valuable insights for optimizing the processing of P3HBHHx in industrial applications, particularly in improving cycle times and achieving better crystallization control. Future work could explore the combined use of nucleating agents or their impact on biodegradation behavior to further enhance the performance of P3HBHHx-based materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J., G.P., L.J.V. and J.P.; methodology, A.J., G.P., L.J.V. and J.P.; formal analysis, A.J., L.J.V. and J.P.; investigation, A.J., L.J.V. and J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J. and J.P.; writing—review and editing, A.J., G.P., L.J.V. and J.P.; supervision, L.J.V. and J.P.; funding acquisition, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

DSC cooling curve (black) and 2nd heating curve (red) of neat P3HBHHx. The inset graph is the expanded crystallization peak from the melt.

Figure 1.

DSC cooling curve (black) and 2nd heating curve (red) of neat P3HBHHx. The inset graph is the expanded crystallization peak from the melt.

Figure 2.

DSC traces of P3HBHHx with various nucleating agents during the cooling (a) and the second heating runs (b). The dashed sphere highlights the shifted melting peak.

Figure 2.

DSC traces of P3HBHHx with various nucleating agents during the cooling (a) and the second heating runs (b). The dashed sphere highlights the shifted melting peak.

Figure 3.

DSC cooling and 2nd heating runs of P3HBHHx with different percentages of talc. The inset graph is an expanded zone of cold crystallization of P3HBHHx with 0.5 wt% of talc.

Figure 3.

DSC cooling and 2nd heating runs of P3HBHHx with different percentages of talc. The inset graph is an expanded zone of cold crystallization of P3HBHHx with 0.5 wt% of talc.

Figure 4.

DSC thermograms of self-nucleated P3HBHHx at various self-nucleation temperatures (Ts), showing the determination of and .

Figure 4.

DSC thermograms of self-nucleated P3HBHHx at various self-nucleation temperatures (Ts), showing the determination of and .

Figure 5.

Nucleation efficiency (NE) of different nucleating agents in P3HBHHx.

Figure 5.

Nucleation efficiency (NE) of different nucleating agents in P3HBHHx.

Figure 6.

FTIR of P3HBHHx samples loaded with different nucleating agents.

Figure 6.

FTIR of P3HBHHx samples loaded with different nucleating agents.

Figure 7.

Weight and number average molecular weights of neat P3HBHHx and the different nucleated samples.

Figure 7.

Weight and number average molecular weights of neat P3HBHHx and the different nucleated samples.

Figure 8.

Thermal degradation behavior of P3HBHHx with different nucleating agents: (a) Remaining weight percentage as a function of temperature, and (b) Derivative TGA curves showing degradation temperature peaks. The black curve represents the sample with the highest thermal stability, red curves correspond to samples with lower thermal stability, and blue curves indicate samples with thermal stability similar to neat P3HBHHx.

Figure 8.

Thermal degradation behavior of P3HBHHx with different nucleating agents: (a) Remaining weight percentage as a function of temperature, and (b) Derivative TGA curves showing degradation temperature peaks. The black curve represents the sample with the highest thermal stability, red curves correspond to samples with lower thermal stability, and blue curves indicate samples with thermal stability similar to neat P3HBHHx.

Figure 9.

Mechanical properties of P3HBHHx with different nucleating agents. (a) Young’s modulus; (b) Tensile strength; (c) elongation at break.

Figure 9.

Mechanical properties of P3HBHHx with different nucleating agents. (a) Young’s modulus; (b) Tensile strength; (c) elongation at break.

Figure 10.

Mechanical properties of PHH_05BN injected at different mold temperatures. (a) Young’s modulus; (b) Tensile strength; (c) Elongation at break.

Figure 10.

Mechanical properties of PHH_05BN injected at different mold temperatures. (a) Young’s modulus; (b) Tensile strength; (c) Elongation at break.

Figure 11.

DSC exothermic peaks corresponding to the different isothermal crystallization temperatures for (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB; (d) PHH_2Talc.

Figure 11.

DSC exothermic peaks corresponding to the different isothermal crystallization temperatures for (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB; (d) PHH_2Talc.

Figure 12.

Evolution of the relative crystallinity over time for isothermal crystallizations performed at the indicated temperatures with: (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB and (d) PHH_2Talc.

Figure 12.

Evolution of the relative crystallinity over time for isothermal crystallizations performed at the indicated temperatures with: (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB and (d) PHH_2Talc.

Figure 13.

Avrami plots from various isothermal crystallization temperatures for: (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB and (d) PHH_2Talc.

Figure 13.

Avrami plots from various isothermal crystallization temperatures for: (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB and (d) PHH_2Talc.

Figure 14.

(a) Comparison between the crystallization rates (a) and crystallization half-times (b) obtained directly from DSC curves (solid lines) and those deduced from the Avrami analyses (dashed lines). Spherulitic morphologies of P3HBHHx samples.

Figure 14.

(a) Comparison between the crystallization rates (a) and crystallization half-times (b) obtained directly from DSC curves (solid lines) and those deduced from the Avrami analyses (dashed lines). Spherulitic morphologies of P3HBHHx samples.

Figure 15.

Spherulitic morphology of (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB; and (d) PHH_2Talc at different crystallization temperatures. Micrographs taken at 100 °C correspond to periods between 2 – 4 min except for the neat polymer that was taken after 30 min.

Figure 15.

Spherulitic morphology of (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB; and (d) PHH_2Talc at different crystallization temperatures. Micrographs taken at 100 °C correspond to periods between 2 – 4 min except for the neat polymer that was taken after 30 min.

Figure 16.

Primary nucleation density for crystallization performed from the melt state at isothermal temperature of 100 °C (a) and 50 °C (b).

Figure 16.

Primary nucleation density for crystallization performed from the melt state at isothermal temperature of 100 °C (a) and 50 °C (b).

Figure 17.

Spherulitic crystal growth at different crystallization temperatures for (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB and (d) PHH_2Talc.

Figure 17.

Spherulitic crystal growth at different crystallization temperatures for (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB and (d) PHH_2Talc.

Figure 18.

Equilibrium melting temperature determined from the first melting peak temperature obtained from the isothermal crystallization of the different samples (black dashed line). The extrapolation of the data from only the neat polymer (blue dashed line) gave a significantly lower value.

Figure 18.

Equilibrium melting temperature determined from the first melting peak temperature obtained from the isothermal crystallization of the different samples (black dashed line). The extrapolation of the data from only the neat polymer (blue dashed line) gave a significantly lower value.

Figure 19.

Lauritzen-Hoffman plots for the crystal growth rate obtained from POM for P3HBHHx and corresponding nucleating agents.

Figure 19.

Lauritzen-Hoffman plots for the crystal growth rate obtained from POM for P3HBHHx and corresponding nucleating agents.

Figure 20.

Simulated dependence of the growth rate on crystallization temperature of (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB; and (d) PHH_2Talc.

Figure 20.

Simulated dependence of the growth rate on crystallization temperature of (a) P3HBHHx; (b) PHH_05BN; (c) PHH_05PHB; and (d) PHH_2Talc.

Figure 21.

DSC thermogram of P3HBHHx samples with nucleating agent at (a) fast cooling run (100 °C/min) and (b) reheating run (10 °C/min). Dashed zone indicates melting of samples, all with Tm=150 °C and melting enthalpy of 53 J/g approximately.

Figure 21.

DSC thermogram of P3HBHHx samples with nucleating agent at (a) fast cooling run (100 °C/min) and (b) reheating run (10 °C/min). Dashed zone indicates melting of samples, all with Tm=150 °C and melting enthalpy of 53 J/g approximately.

Table 1.

P3HBHHx samples prepared with various nucleating agents at concentration of 0.5 wt% and 2 wt%.

Table 1.

P3HBHHx samples prepared with various nucleating agents at concentration of 0.5 wt% and 2 wt%.

| Sample code |

Nucleating agent |

Concentration (wt%) |

| P3HBHHx |

None |

0 |

| PHH_05BN / PHH_2BN |

Boron nitride |

0.5 / 2 |

| PHH_05PHB / PHH_2PHB |

P3HB |

0.5 / 2 |

| PHH_05Talc / PHH_2Talc |

Talc |

0.5 / 2 |

| PHH_05LAK / PHH_2LAK |

Organic potassium salt |

0.5 / 2 |

| PHH_05UFC / PHH_2UFC |

Ultrafine cellulose |

0.5 / 2 |

Table 2.

DSC summarized data of P3HBHHx with 0.5 wt% nucleating agents obtained from non-isothermal processes.

Table 2.

DSC summarized data of P3HBHHx with 0.5 wt% nucleating agents obtained from non-isothermal processes.

| Samples |

Tc (˚C) |

ΔHc (J/g) |

Tg (˚C) |

Tcc (˚C) |

ΔHcc (˚C) |

Tm1 (˚C) |

Tm2 (˚C) |

ΔHf (J/g) |

| P3HBHHx |

36.4 |

8.9 |

1.4 |

44.7 |

44.6 |

130.0 |

150.2 |

55.6 |

| PHH_05LAK |

45.6 |

18.3 |

1.4 |

45.5 |

38.4 |

129.8 |

149.5 |

58.0 |

| PHH_05UFC |

58.9 |

48.5 |

4.8 |

- |

- |

132.1 |

150.2 |

56.5 |

| PHH_05Talc |

66.5 |

46.3 |

3.7 |

45.3 |

0.8 |

133.2 |

149.9 |

49.7 |

| PHH_05PHB |

81.9 |

59.5 |

4.4 |

- |

- |

138.1 |

152.7 |

60.0 |

| PHH_05BN |

84.1 |

56.5 |

3.3 |

- |

- |

136.6 |

150.7 |

56.0 |

Table 3.

Crystallization temperature of P3HBHHx with different nucleating agent at cooling rate 5 ˚C/min and corresponding nucleation efficiency calculated from equation (1).

Table 3.

Crystallization temperature of P3HBHHx with different nucleating agent at cooling rate 5 ˚C/min and corresponding nucleation efficiency calculated from equation (1).

| |

Tc (˚C)a

|

NE (%)b

|

| P3HBHHx |

54.5 |

- |

| PHH_05LAK |

57.0 |

3.4 |

| PHH_05UFC |

68.3 |

18.9 |

| PHH_05Talc |

76.9 |

30.7 |

| PHH_2Talc |

83.9 |

40.2 |

| PHH_05PHB |

85.8 |

42.8 |

| PHH_05BN |

88.3 |

46.2 |

Table 4.

Thermogravimetric data for the samples studied.

Table 4.

Thermogravimetric data for the samples studied.

| |

Tdeg

(˚C) |

T5%

(˚C) |

T50%

(˚C) |

T90%

(˚C) |

Residue at 450 ˚C (wt%) |

| P3HBHHx |

275.7 |

246.9 |

269.1 |

276.7 |

0 |

| PHH_05LAK |

273.5 |

246.8 |

267.3 |

275.1 |

0.57 |

| PHH_05UFC |

261.1 |

236.3 |

255.4 |

263.6 |

0.50 |

| PHH_05PHB |

273.6 |

247.1 |

267.8 |

275.3 |

0.52 |

| PHH_05BN |

258.3 |

236.1 |

255.2 |

263.8 |

0.58 |

| PHH_05Talc |

271.4 |

246.7 |

266.9 |

274.6 |

0.53 |

| PHH_2Talc |

279.5 |

247.9 |

264.3 |

281.7 |

1.76 |

Table 5.

Mechanical properties of P3HBHHx and corresponding nucleating agents.

Table 5.

Mechanical properties of P3HBHHx and corresponding nucleating agents.

| Sample |

Young’s modulus

(MPa) |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Elongation at Break (%) |

| P3HBHHx |

2264 ± 138 |

33.7 ± 0.4 |

4.0 ± 0.2 |

| PHH_05LAK |

2260 ± 213 |

30.8 ± 0.2 |

3.8 ± 0.1 |

| PHH_05UFC |

2309 ± 42 |

34.1 ± 0.4 |

3.9 ± 0.1 |

| PHH_05PHB |

1866 ± 119 |

32.4 ± 0.3 |

4.8 ± 0.2 |

| PHH_05BN |

2060 ± 19 |

34.5 ± 0.4 |

4.5 ± 0.2 |

| PHH_05Talc |

1906 ± 43 |

30.0 ± 0.4 |

3.6 ± 0.1 |

| PHH_2Talc |

1943 ± 46 |

31.2 ± 0.6 |

3.9 ± 0.2 |

Table 6.

Summarized data of isothermal crystallization process for P3HBHHx and various nucleating agents at different temperatures obtained from DSC.

Table 6.

Summarized data of isothermal crystallization process for P3HBHHx and various nucleating agents at different temperatures obtained from DSC.

| Sample |

Isothermal Temperature (˚C) |

Enthalpy of Crystallization (J/g) |

Half-Time of Crystallization τ(1/2) (s) |

Crystallization rate

k x103(s-1) |

| P3HBHHx |

50 |

41.5 |

77 |

13.06 |

| 70 |

55.1 |

159 |

6.27 |

| 80 |

60.3 |

340 |

2.94 |

| 85 |

60.1 |

726 |

1.38 |

| 95 |

60.8 |

1404 |

0.71 |

| PHH_05BN |

95 |

48.1 |

68 |

14.67 |

| 100 |

64.3 |

99 |

10.05 |

| 105 |

66.5 |

173 |

5.77 |

| 110 |

66.7 |

306 |

3.27 |

| PHH_05PHB |

85 |

46.9 |

104 |

9.66 |

| 90 |

59.4 |

165 |

6.06 |

| 95 |

60.2 |

193 |

5.18 |

| 100 |

60.5 |

242 |

4.13 |

| PHH_2Talc |

85 |

44.5 |

84 |

11.84 |

| 90 |

55.6 |

106 |

9.47 |

| 95 |

58.0 |

133 |

7.53 |

| 100 |

58.4 |

244 |

4.09 |

| 105 |

60.3 |

434 |

2.31 |

Table 7.

Isothermal crystallization kinetic parameters deduced from Avrami equation for P3HBHHx and corresponding nucleating agents. .

Table 7.

Isothermal crystallization kinetic parameters deduced from Avrami equation for P3HBHHx and corresponding nucleating agents. .

| Sample |

Tc (˚C) |

n |

Z x106

(s-n) |

k x103(s-1) Avrami |

τ(1/2) (s)

Avrami |

| P3HBHHx |

70 |

2.10 |

16.11 |

5.26 |

160 |

| 80 |

2.34 |

0.890 |

2.63 |

326 |

| 85 |

2.54 |

0.046 |

1.29 |

670 |

| 95 |

2.75 |

0.002 |

0.64 |

1366 |

| PHH_05BN |

100 |

2.39 |

11.98 |

8.76 |

98 |

| 105 |

2.20 |

8.38 |

4.98 |

170 |

| 110 |

2.39 |

0.87 |

2.88 |

298 |

| PHH_05PHB |

90 |

2.29 |

5.21 |

4.95 |

172 |

| 95 |

2.06 |

14.43 |

4.47 |

187 |

| 100 |

2.12 |

5.79 |

3.43 |

246 |

| PHH_2Talc |

95 |

2.32 |

8.42 |

6.45 |

132 |

| 100 |

2.68 |

0.27 |

3.54 |

246 |

| 105 |

2.88 |

0.02 |

2.04 |

431 |

Table 8.

Summarized data of growth rate of P3HBHHx and nucleated samples at different temperatures, determined from the slope of lineal correlation of crystal radium increase with time.

Table 8.

Summarized data of growth rate of P3HBHHx and nucleated samples at different temperatures, determined from the slope of lineal correlation of crystal radium increase with time.

| Sample |

P3HBHHx |

G (µm/s) |

Induction time (s) |

| P3HBHHx |

50 |

0.23 |

1 |

| 60 |

0.57 |

45 |

| 65 |

0.49 |

50 |

| PHH_05BN |

80 |

0.71 |

1 |

| 90 |

0.65 |

71 |

| 100 |

0.48 |

150 |

| PHH_05PHB |

80 |

0.76 |

1 |

| 90 |

0.73 |

22 |

| 100 |

0.50 |

80 |

| PHH_2Talc |

80 |

0.87 |

1 |

| 90 |

0.79 |

75 |

| 100 |

0.43 |

100 |

Table 9.

Lauritzen-Hoffman parameters obtained from POM analyses for P3HBHHx and nucleated samples.

Table 9.

Lauritzen-Hoffman parameters obtained from POM analyses for P3HBHHx and nucleated samples.

| Sample |

Linear plot |

R2 |

Kg 10-5 (K2) |

| P3HBHHx |

y = -4.097x + 22.295 |

0.9946 |

4.10 |

| PHH_05BN |

y = -1.707x + 13.463 |

0.9924 |

1.71 |

| PHH_05PHB |

y = -1.734x + 13.644 |

0.9957 |

1.73 |

| PHH_2Talc |

y = -2.107x + 15.293 |

0.9996 |

2.11 |