Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Area

Monitoring Sites and Frequency of Sampling

Hydrological Data

Physico-Chemical and Biological Variables of Water Quality

Statistical Analyses

The Trophic State Index (TSI)

Results and Discussion

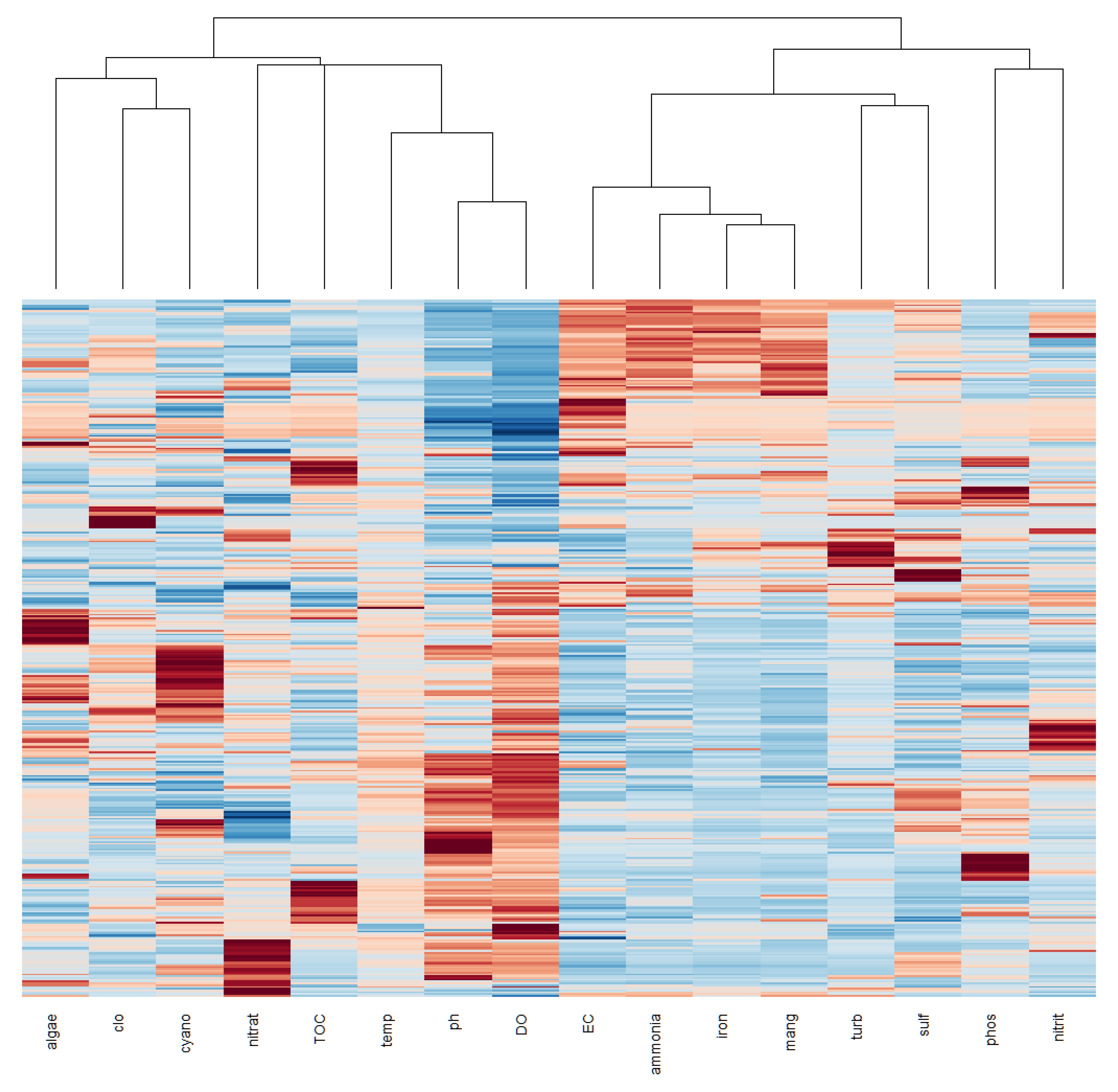

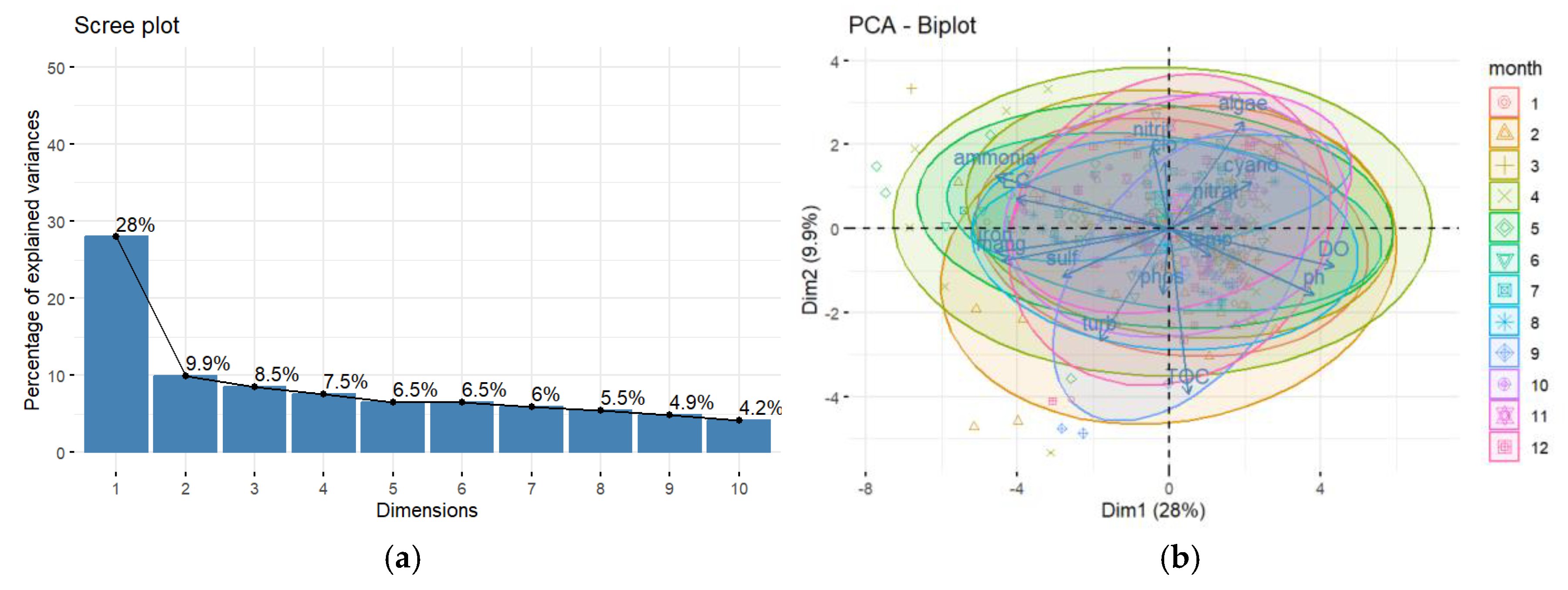

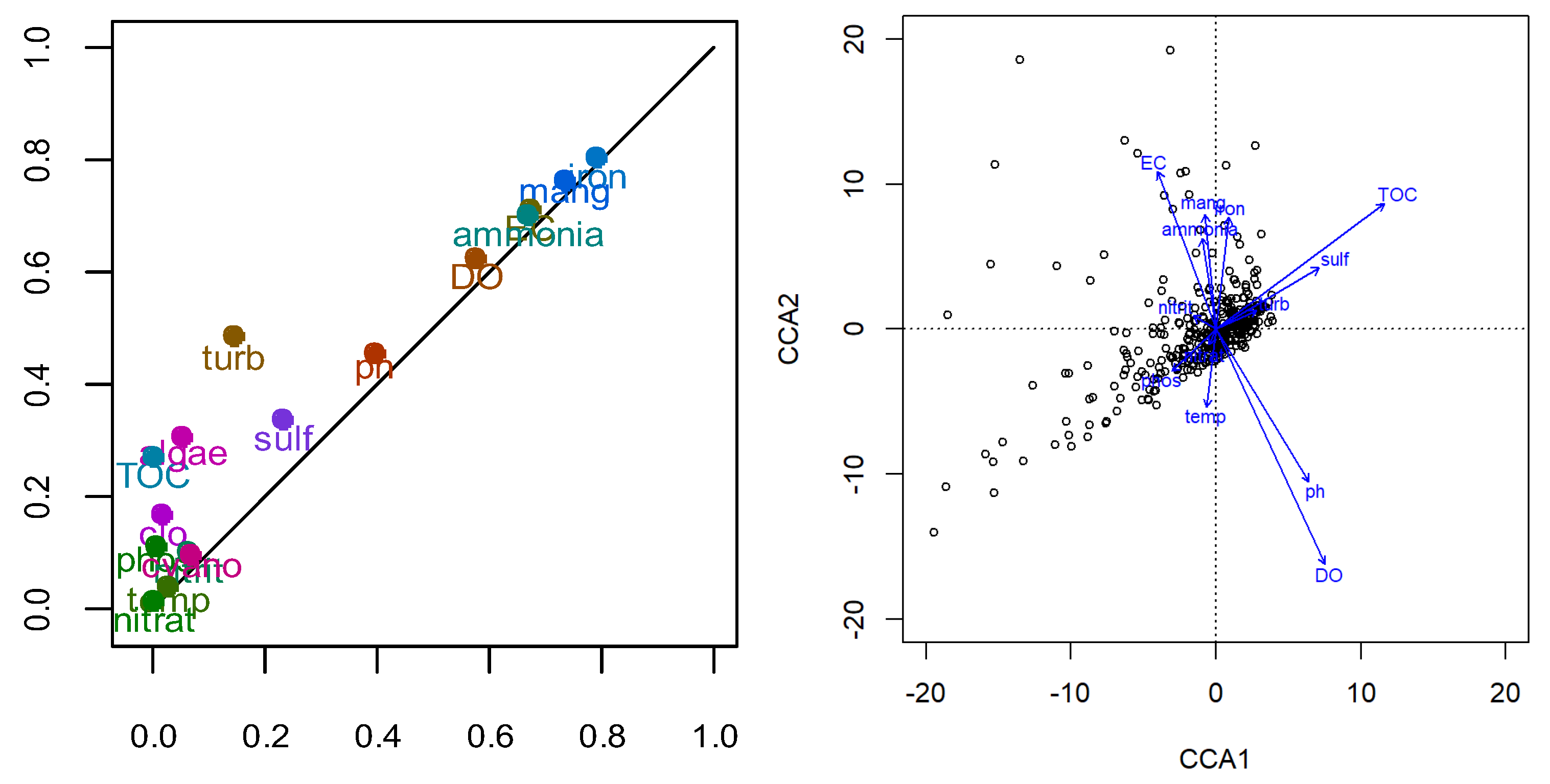

Physical, Chemical, and Biological Characterization of Water

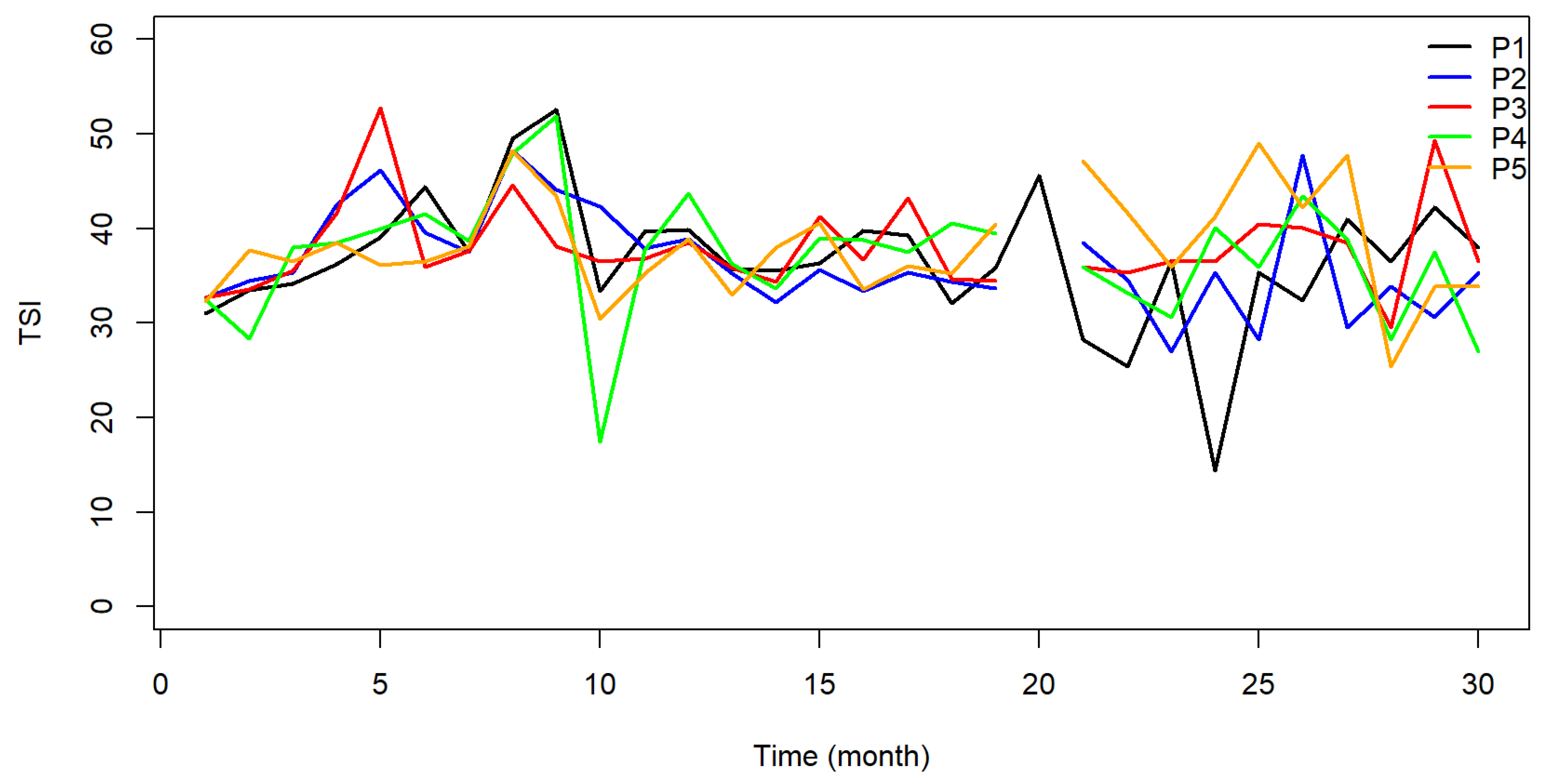

Trophic State Index (TSI)

Phytoplancton Analyses

Regional and Morphological Influences

Conclusions

References

- Rolim, Silvia Beatriz Alves et al. “Remote sensing for mapping algal blooms in freshwater lakes: A review.”. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 19602–19616. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N. Chen, N., S. Wang, X. Zhang, and S. Yang. “A risk assessment method for remote sensing of cyanobacterial blooms in inland waters.”. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 740, 140012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, H. W., and T. G. Otten. “Harmful Cyanobacterial Blooms: Causes, Consequences and Control.”. Microbial Ecology 2013, 65, 995–1010. [CrossRef]

- Carey, C. C., B. W. Ibelings, E. P. Hoffmann, D. P. Hamilton, and J. D. Brookes. “Eco-physiological adaptations that favour freshwater cyanobacteria in a changing climate.”. Water Research 2012, 46, 1394–1407. [CrossRef]

- Lins, R. P. M., L. G. Barbosa, A. Minillo, and B. S. O. De Ceballos. “Cyanobacteria in a eutrophicated reservoir in a semi-arid region in Brazil: dominance and microcystin events of blooms.”. Brazilian Journal of Botany 2016, 39, 905–915.

- Bittencourt-Oliveira, M. C., S. N. Dias, A. N. Moura, M. K. Cordeiro-Araújo, and E. W. Dantas. “Seasonal dynamics of cyanobacteria in a eutrophic reservoir (Arcoverde) in a semi-arid region of Brazil.”. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2012, 72, 533–544. [CrossRef]

- Gusmão, C. A. , and J. C. Valsecchi. “Projeto Básico Ambiental da Barragem e do Reservatório de Regularização e Acumulação do Ribeirão João Leite em Goiânia, Goiás - Brasil.” BVSDE. Biblioteca virtual desarrollo sostenible y salud ambiental, 2009. http://www.bvsde.paho.org/bvsAIDIS/PuertoRico29/gusma.pdf.

- Ferreira, R. D., C. C. F. Barbosa, and E. M. L. M. Novo. “Assessment of in vivo fluorescence method for chlorophyll-a estimation in optically complex waters (Curuai floodplain, Pará – Brazil).”. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia 2012, 24, 373–386.

- Cha, Y. S. Park, K. Kim, M. Byeon, and C. A. Stow. “Probabilistic prediction of cyanobacteria abundance in a Korean reservoir using a Bayesian Poisson Model. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mowe, M. A. D., S. M. Mitrovic, R. P. Lim, A. Furey, and D. C. J. Yeo. “Tropical Cyanobacterial Blooms: A Review of Prevalence, Problem Taxa, Toxins and Influencing Environmental Factors.”. Journal of Limnology 2015, 74, 206–227.

- O’neil, J., T. W. Davis, M. A. Burford, and C. Gobler. “The rise of harmful cyanobacteria blooms: the potential roles of eutrophication and climate change.”. Harmful Algae 2012, 14, 313–334. [CrossRef]

- Burford, M. A., S. A. Johnson, A. J. Cook, T. V. Packer, B. M. Taylor, and E. R. Townsley. “Correlations between watershed and reservoir characteristics, and algal blooms in subtropical reservoirs.”. Water Research 2007, 41, 4105–4114. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., C. Xu, Q. Lin, W. Xiao, B. Huang, W. Lu, ... and J. Chen. “Modeling of algal blooms: Advances, applications, and prospects.”. Ocean & Coastal Management 2024, 255, 107250.

- Noori, R., M. S. Sabahi, A. R. Karbassi, A. Baghvand, and T. Zadeh. “Multivariate statistical analysis of surface water quality based on correlations and variations in the data set.”. Desalination 2010, 270, 129–136.

- Oliveira, F. H. P. C., A. L. S. Capela e Ara, C. H. P. Moreira, O. O. Lira, M. R. F. Padilha, and N. K. S. Shinohara. “Seasonal changes of water quality in a tropical shallow and eutrophic reservoir in the metropolitan region of Recife (Pernambuco-Brazil).”. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 2014, 86, 1863–1872.

- Davis, T. W., D. L. Berry, G. L. Boyer, and C. J. Gobler. “The effects of temperature and nutrients on the growth and dynamics of toxic and non-toxic strains of Microcystis during cyanobacteria blooms.”. Harmful Algae 2009, 8, 715–725. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, L. V., K. T. M. Formiga, and V. A. F. Costa. “Comparison of methods for filling daily and monthly rainfall missing data: statistical models or imputation of satellite retrievals?”. Water 2022, 14, 3144. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, L. V., K. T. M. Formiga, and V. A. F. Costa. “Analysis of the IMERG-GPM precipitation product analysis in Brazilian midwestern basins considering different time and spatial scales.”. Water 2022, 14, 2472. [CrossRef]

- Rice, E. W. Bridgewater, and American Public Health Association, eds. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. Vol. 10. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 2012.

- CETESB. Guia Nacional de Coleta e Preservação de Amostra. Água, sedimento, comunidade aquáticas e efluentes líquidos. São Paulo: Companhia Estadual de Tecnologia de Saneamento Ambiental do Estado de São Paulo, 2011.

- Oliveira, F. A. D., T. S. R. Pereira, A. K. Soares, and K. T. M. Formiga. “Using hydrodynamic model for flow calculation from level measurements.”. Revista Brasileira de Recursos Hídricos 2016, 21, 707–718.

- Carlson, R. E. “A trophic state index for lakes. ” Limnology and Oceanography 1977, 22, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F., Y. Liu, and H. Guo. “Application of Multivariate Statistical Methods to Water Quality Assessment of the Watercourses in Northwestern New Territories, Hong Kong.”. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2007, 132, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E. P. R. A. Filho, J. Pereira, and K. T. Martins Formiga. “Temporal variation and risk assessment of heavy metals and nutrients from water and sediment in a stormwater pond, Brazil.” Water Supply 23, no. 1 (2023): 206-221.

- Lamparelli, M. C. “Graus de trofia em corpos d’água do estado de São Paulo: avaliação dos métodos de monitoramento.” Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, 2004.

- OECD. The OECD Cooperative Programme on Eutrophication. Canadian Contribution. Prepared by L. L. Janus and R. A. Vollenweider. Ottawa: Environment Canada, National Water Research Institute, Inland Waters Directorate, 1981.

- Li, Yuanrui et al. “Research trends in the remote sensing of phytoplankton blooms: results from bibliometrics.”. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 4414. [CrossRef]

- Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº29/14 de 12/12/2011. Dispõe sobre os procedimentos de controle e de vigilância da qualidade da água para consumo humano e seu padrão de potabilidade. 2011.

- Brasil. Conselho Nacional do Meio Ambiente - Conama. Resolução Conama N° 357, de março de 2005. Dispõe sobre a classificação dos corpos de água e diretrizes ambientais para o seu enquadramento. (URL original inválida).

- Fernandes, V. O., B. Cavati, L. B. Oliveira, and B. D. Souza. “Ecologia de cianobactérias: fatores promotores e consequências das florações.”. Oecologia Brasiliensis 2009, 13, 247–258.

- Buzeli, G. M., and M. B. Cunha-Santino. “Análise e diagnóstico da qualidade da água e estado trófico do reservatório de Barra Bonita, SP.”. Ambi-Água 2013, 8, 186–205.

- Adloff, C. T., C. C. Bem, G. Reichert, and J. C. R. Azevedo. “Análise da comunidade fitoplanctônica com ênfase em cianobactérias em quatro reservatórios em sistema de cascata do rio Iguaçu, Paraná, Brasil.”. Revista Brasileira de Recursos Hídricos 2018, 23, e6.

- Graham, L. E., J. M. Graham, L. W. Wilcox, and M. E. Cook. Algae. 3rd ed. Dubuque: LJLM Press, 2016.

- Bellém, F., S. Nunes, and M. Morais. “Toxicidade a Cianobactérias: Impacte Potencial na Saúde Pública em populações de Portugal e Brasil.” In XIV Encontro da Rede Luso-Brasileira de Estudos Ambientais, Recife, Brasil, 2011.

- Cunha, D. G. F., and M. C. Calijuri. “Variação sazonal dos grupos funcionais fitoplanctônicos em braços de um reservatório tropical de usos múltiplos no estado de São Paulo (Brasil).”. Acta Botanica Brasilica 2011, 25, 822–831. [CrossRef]

- Burford, M. A., S. A. Johnson, A. J. Cook, T. V. Packer, B. M. Taylor, and E. R. Townsley. “Correlations between watershed and reservoir characteristics, and algal blooms in subtropical reservoirs.”. Water Research 2007, 41, 4105–4114. [CrossRef]

- Malheiros, C. H. L. Hardoim, Z. M. Lima, and R. S. S. Amorim. “Qualidade da água de uma represa localizada em área agrícola (Campo Verde, MT, Brasil).” Ambi-Água 7, no. 2 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Jardim, B. F. M. “Variação dos Parâmetros Físicos e Químicos das Águas Superficiais da Bacia do Rio das Velhas-MG e sua Associação com as Florações de Cianobactérias.” Masters dissertation, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2011.

- Figueredo, C. C., R. M. Pinto-Coelho, A. M. M. B. Lopes, P. H. O. Lima, B. Gücker, and A. Giani. “From Intermittent to Persistent Cyanobacterial Blooms: Identifying the Main Drivers in an Urban Tropical Reservoir.”. Journal of Limnology 2016, 75, 540–550.

- Cha, Y., S. S. Park, K. Kim, M. Byeon, and C. A. Stow. “Probabilistic prediction of cyanobacteria abundance in a Korean reservoir using a Bayesian Poisson Model.” Water Resources Research 50 (2014). (Número/Páginas ausentes na lista original).

- Paerl, H. W., and J. Huisman. “Blooms like it hot.”. Science 2008, 320, 57–58. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J., Wang, L., Yang, Y., Huang, T. A case study of thermal and chemical stratification in a drinking water reservoir. Science of The Total Environment. Volume 848, 20 November 2022.

| Variance | Axis 1 | Axis 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 28,0% | 9,9% | |

| pH | 0.3295 | -0.2285 |

| DO | 0.3749 | -0.1314 |

| Turbidity (turb) | -0.1576 | -0.3888 |

| Electrical Cond. (EC) | -0.3474 | 0.1034 |

| Water temperature (temp) | 0.0957 | -0.0977 |

| Total phosphorus (phosp) | -0.0135 | -0.2267 |

| Nitrate | 0.1064 | 0.0665 |

| Nitrite | -0.0378 | 0.2807 |

| Ammonia | -0.3956 | 0.1823 |

| Total organic carbon (TOC) | 0.0429 | -0.5733 |

| Total iron (iron) | -0.3962 | -0.0820 |

| Manganese (mang) | -0.3802 | -0.1126 |

| Sulfate | -0.2427 | -0.1645 |

| Chlorophyll-a | -0.0107 | 0.2305 |

| Algae | 0.1695 | 0.3710 |

| Cyanobacteria | 0.1887 | 0.1595 |

| Axis 1 | Axis 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalues | 0.0008694 | 2.441e-06 |

| Proportion explained | 0.9972000 | 2.800e-03 |

| Cumulative ratio | 0.9972000 | 1.000e+00 |

| Scores biological parameters | ||

| Chlorophyll-a (clo) | -0.259900 | 3.710e-01 |

| Algae | -0.255799 | -5.098e-04 |

| Cyanobacteria (ciano) | 0.003399 | 1.054e-07 |

| Biplot scores physicochemical parameters. | ||

| pH | 0.32630 | -0.53392 |

| DO | 0.38116 | -0.82202 |

| Turbidity (turb) | 0.14211 | 0.06506 |

| Electrical Conductivity (EC) | -0.20276 | 0.55114 |

| Water temperature (temp) | -0.03188 | -0.27252 |

| Total phosphorus (phosp) | -0.15281 | -0.14644 |

| Nitrate | -0.02295 | -0.05340 |

| Nitrite | -0.07925 | 0.04514 |

| Ammonia | -0.04917 | 0.31724 |

| Total organic carbon (TOC) | 0.58905 | 0.43882 |

| Total iron (iron) | 0.04512 | 0.39125 |

| Manganese (mang) | -0.03817 | 0.40098 |

| Sulfate | 0.36101 | 0.21400 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).