1. Introduction

The surge in digital finance has led to a parallel rise in fraudulent activities, placing unprecedented pressure on institutions to develop accurate, secure, and scalable fraud detection systems. As financial operations increasingly migrate online, cybercriminals exploit vulnerabilities across e-banking platforms, mobile payment applications, and transaction APIs [

1,

2]. This evolving threat landscape demands not only precise predictive capabilities but also interpretability and compliance with strict data privacy standards.

Conventional fraud detection strategies predominantly rely on supervised machine learning models such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Decision Trees, Random Forests, and various forms of neural networks [

3]. These algorithms analyze engineered features derived from transactional metadata and behavioral patterns to classify transactions as legitimate or fraudulent. However, centralizing data for model training raises significant concerns regarding data breaches, regulatory compliance, and the protection of sensitive personal information, particularly under frameworks like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

To mitigate these concerns, Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a transformative approach. FL enables multiple institutions to collaboratively train a global model without exchanging raw data. Instead, only local model updates or gradients are shared, thus preserving data locality and minimizing privacy risks [

4,

5]. This collaborative yet privacy-preserving paradigm aligns closely with the regulatory and ethical expectations placed on financial systems today.

In parallel, the field of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) has gained prominence as a necessary complement to black-box models. In high-stakes environments such as financial services, decision-makers require not only accurate outputs but also a clear rationale behind model predictions. Techniques, such as Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME), provide insight into feature contributions and improve model transparency. When embedded into a federated architecture, these interpretability tools enhance local accountability without compromising the security of underlying data.

Despite these advances, several challenges remain. Fraud datasets often suffer from severe class imbalance, with fraudulent instances typically representing less than one percent of the total data [

6]. This imbalance skews traditional classifiers and increases the likelihood of undetected fraud. Moreover, federated systems must address additional technical hurdles including non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) data, communication overhead, and model convergence discrepancies across nodes.

This study introduces a federated anomaly detection framework based on deep autoencoders, designed to operate across decentralized financial data silos [

7]. The architecture is validated using two real-world datasets: a publicly available credit card transaction dataset and a large-scale synthetic banking dataset from the NeurIPS 2022 competition. The autoencoders are trained locally on each node and detect anomalous transactions by measuring reconstruction error, identifying fraud without the need for labelled data.

The primary contributions of this work are as follows:

A privacy-preserving federated learning pipeline tailored for real-time fraud detection;

The application of deep autoencoders for effective anomaly detection in highly imbalanced data scenarios;

An interpretability approach that supports model transparency through ROC curves, confusion matrices, and feature correlation heatmaps.

In general, the above components present a robust, ethical, and scalable approach to modern fraud detection that balances performance, privacy, and interpretability.

2. Related Work

In recent years, the rapid evolution of digital financial ecosystems has elevated fraud detection to a subject of paramount significance within both academic inquiry and professional practice [

8]. As fraudulent techniques grow increasingly intricate and adaptive, the imperative for detection systems that are not only accurate but also scalable, privacy preserving, and transparent has become ever more pressing. Traditional machine learning models typically trained in centralized environments have long underpinned automated fraud detection. However, their effectiveness is frequently hampered by persistent challenges, including the management of severely imbalanced datasets, the protection of sensitive user information, and the inherent opacity of their decision-making processes.

These limitations have precipitated a paradigm shift towards more advanced and resilient frameworks, particularly those rooted in decentralized learning architectures [

9]. In this regard, federated learning has emerged as a promising alternative, enabling multiple institutions to collaboratively train high-performing models without the need to share confidential or proprietary data. In parallel, the rise of explainable artificial intelligence reflects a broader movement towards interpretability, ensuring that model outputs are not only robust but also comprehensible to stakeholders, auditors, and regulatory bodies [

10]. What follows is a detailed exploration of the prevailing approaches to fraud detection, with particular attention given to the intersection of federated learning and explain ability as key pillars underpinning the next generation of ethical and effective solutions.

2.1. Traditional Approaches to Financial Fraud Detection

The detection of fraudulent financial transactions has long been recognized as a matter of critical importance within the banking and e-commerce sectors. Traditional methodologies have primarily relied upon supervised machine learning algorithms, including Support Vector Machines (SVM), Decision Trees, Random Forests, and various forms of neural networks, to categories transactions as either legitimate or fraudulent [

11]. These approaches typically draw upon engineered features extracted from transaction metadata, user profiles, and historical behavioral patterns to identify anomalies in real time.

Despite their widespread application, such models face notable limitations when deployed in real-world settings, chiefly due to the pronounced class imbalance inherent in most fraud-related datasets [

12]. Indeed, Fraudulent transactions generally constitute less than one per cent of all activity, which significantly hampers the ability of conventional classifiers for conducting an effective recognition of normal and anomalous behavior [

13]. Consequently, these systems often exhibit elevated false-negative rates, resulting in a failure to detect fraudulent instances. To counteract this, oversampling methods, most notably the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) and Adaptive Synthetic Sampling (ADASYN) have been adopted to artificially increase the representation of minority class instances, thereby enhancing the model’s responsiveness to rare fraudulent behavior [

14].

Table 1 presents a concise comparison of key approaches in financial fraud detection, highlighting the evolution from traditional supervised models like SVMs and Random Forests to modern frameworks such as Federated Learning and Explainable AI. While earlier models struggle with data imbalance and lack transparency, newer methods address privacy, scalability, and interpretability making them more suited to real-world financial ecosystems.

In parallel with supervised learning, unsupervised learning techniques have garnered increasing interest. Models, such as clustering algorithms, Isolation Forests, and deep learning-based autoencoders, have proven to be effective in contexts where labelled data is limited or altogether unavailable [

15]. These methods operate on the principle of anomaly detection, which identifies suspicious patterns by measuring deviations in reconstruction error or data distribution, and thus enables the detection of fraud without prior explicit annotation.

2.2. Federated Learning in the Context of Fraud Detection

Amid growing global concern over data privacy, spurred in large part by regulatory frameworks, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), traditional centralized approaches to machine learning have increasingly come under scrutiny. This shift has prompted the rise of federated learning, an innovative paradigm that enables organisations together train a shared global model together without the need to exchange raw or sensitive data. In the context of fraud detection, FL presents an especially promising solution by affording financial institutions the ability to jointly enhance detection abilities while upholding stringent data confidentiality standards [

15].

Recent developments have affirmed the viability of FL in practical applications. Notably, Yin et al. (2019) introduced the Federated Fraud Detection (FFD) framework, which successfully orchestrated collaborative model training across multiple banking institutions while maintaining strict data locality. This framework offered a robust compromise between model accuracy and regulatory compliance [

16]. Building upon this foundation, Liu et al. (2024) advanced the field further by integrating FL with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), thereby enabling models to capture complex inter-transactional relationships, significantly bolstering their capacity to detect fraudulent patterns with greater nuance and precision. Yet, despite its considerable promise, FL is not without its challenges. Real-world implementations must grapple with issues such as statistical heterogeneity between nodes, heightened communication costs, and difficulties in achieving convergence under non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) data conditions. Addressing these technical and operational hurdles remains a critical area of ongoing investigation, as researchers continue to refine FL frameworks to meet the demands of large-scale, heterogeneous financial environments [

17].

2.3. Explainable AI in Financial Fraud Detection

As machine learning models continue to grow in complexity and opacity, the imperative for interpretability has become increasingly pronounced particularly in high-stakes sectors such as finance. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) seeks to render model predictions transparent, offering critical insights into the rationale underpinning algorithmic decisions [

18]. This capability is especially vital in the realm of fraud detection, where human analysts must often justify and substantiate automated flags before initiating corrective or preventative actions.

Among the most prominent tools in the XAI arsenal are Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME), both of which have proven effective in illuminating the inner mechanisms of otherwise opaque black-box models. These methods provide feature-attribution explanations that not only enhance understanding but also foster institutional trust and regulatory transparency [

18]. When deployed within a federated learning environment, such techniques enable the interpretability of locally trained models without the need to compromise on data privacy, a critical advantage in data-sensitive domains.

A notable contribution in this context is the Explainable Federated Learning (XFL) framework proposed by [

19]. which adeptly combines the data protection benefits of FL with the clarity afforded by SHAP-based interpretability. Their work exemplifies how privacy and transparency can be mutually reinforced rather than mutually exclusive by ensuring that financial institutions can detect fraudulent activity, both effectively and accountably.

In summary, the evolution of fraud detection technologies reflects a broader paradigm shift towards systems that are not only accurate and adaptive but also ethically responsible and intelligible. While foundational models have laid the groundwork for real-time detection, the integration of federated learning with explainable AI marks a pivotal step to build fraud detection models that are robust, scalable, and aligned with regulatory expectations and public trust [

18]. Nonetheless, continued research is required to navigate persistent challenges, including data imbalance, model scalability, and the often-delicate balance between performance, interpretability, and privacy.

3. Methodology and Methods

This research adopts a federated learning-based anomaly detection framework to identify fraudulent banking transactions across decentralized data silos. The design intentionally reflects the privacy, scalability, and heterogeneity challenges typical of real-world financial ecosystems [

20]. The methodology comprises structured phases: dataset selection, preprocessing, model construction, decentralized training simulation, and evaluation all detailed below to facilitate full reproducibility and transparency.

3.1. Dataset Description

This study integrates two publicly available datasets to simulate decentralized fraud detection in conditions that closely resemble those in real-world financial institutions.

The first dataset, known as the Credit Card Fraud Detection dataset, was compiled by researchers at the Université Libre de Bruxelles and is frequently cited in academic literature [

21]. It consists of 284,807 anonymized credit card transactions recorded in Europe, with each transaction represented by 30 numerical features derived through Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The binary variable Class designates fraudulent (1) and legitimate (0) transactions. One of the most challenging aspects of this dataset is its highly imbalanced nature, as fraudulent activities constitute less than 0.2% of all records, thereby posing a significant obstacle for traditional classification models.

The second dataset employed in this study originates from the NeurIPS 2022 competition and is titled the Bank Account Fraud [

22]. It was developed by a consortium of researchers, including Sérgio Jesus, José Pombal, Duarte Alves, André F. Cruz, Pedro Saleiro, Rita P. Ribeiro, João Gama, and Pedro Bizarro. The dataset comprises more than six million synthetic banking records, distributed across six structured CSV files. Each entry encapsulates a wide range of attributes, including demographic details, transactional behaviour, and device metadata. Fraudulent activity is identified using fields such as fraud_bool or is_fraud, which are inconsistently labeled across the various files and require standardization during preprocessing.

Although synthetic in nature, this dataset was meticulously generated using domain-informed simulations designed to emulate authentic fraud scenarios and user behavioural patterns within digital banking systems. Its scale and complexity render it particularly suitable for evaluating decentralised learning algorithms under near-realistic financial conditions.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

To unify the structure and quality of the datasets, a comprehensive preprocessing strategy was implemented. Categorical features found within the NeurIPS datasets, such as employment_status, device_os, and housing_status, were converted into numerical format using label encoding. For numeric attributes, Z-score standardization was applied to scale features such as transaction Amount, Time, and behavioral signals in order to ensure uniform variance across variables [

23].

Missing and infinite values were identified and removed, as their presence risked invalidating model optimization by introducing undefined gradients during backpropagation. Once cleaned, the datasets were filtered to retain only shared, numerical attributes to ensure model compatibility across both training nodes [

24]. Inconsistent fraud labels were renamed to a unified Class column, and all non-contributing metadata such as IDs or timestamps were excluded to prioritize behavioral and transactional patterns.

3.3. Autoencoder Model Architecture

In this study, an unsupervised deep autoencoder was employed as the primary anomaly detection mechanism due to its proven capacity to learn compact representations of normal transaction patterns and flag deviations without reliance on extensive labelled data [

23]. This approach is especially advantageous in financial fraud detection, where fraudulent samples are significantly outnumbered by legitimate ones, thus making supervised techniques less effective.

An autoencoder consists of two main components: the encoder, which compresses the high-dimensional input features into a low-dimensional latent space, and the decoder, which attempts to reconstruct the original input from this compressed representation [

25]. The discrepancy between the input and its reconstruction serves as an anomaly score, reflecting the degree to which the transaction deviates from learned normal [

26].

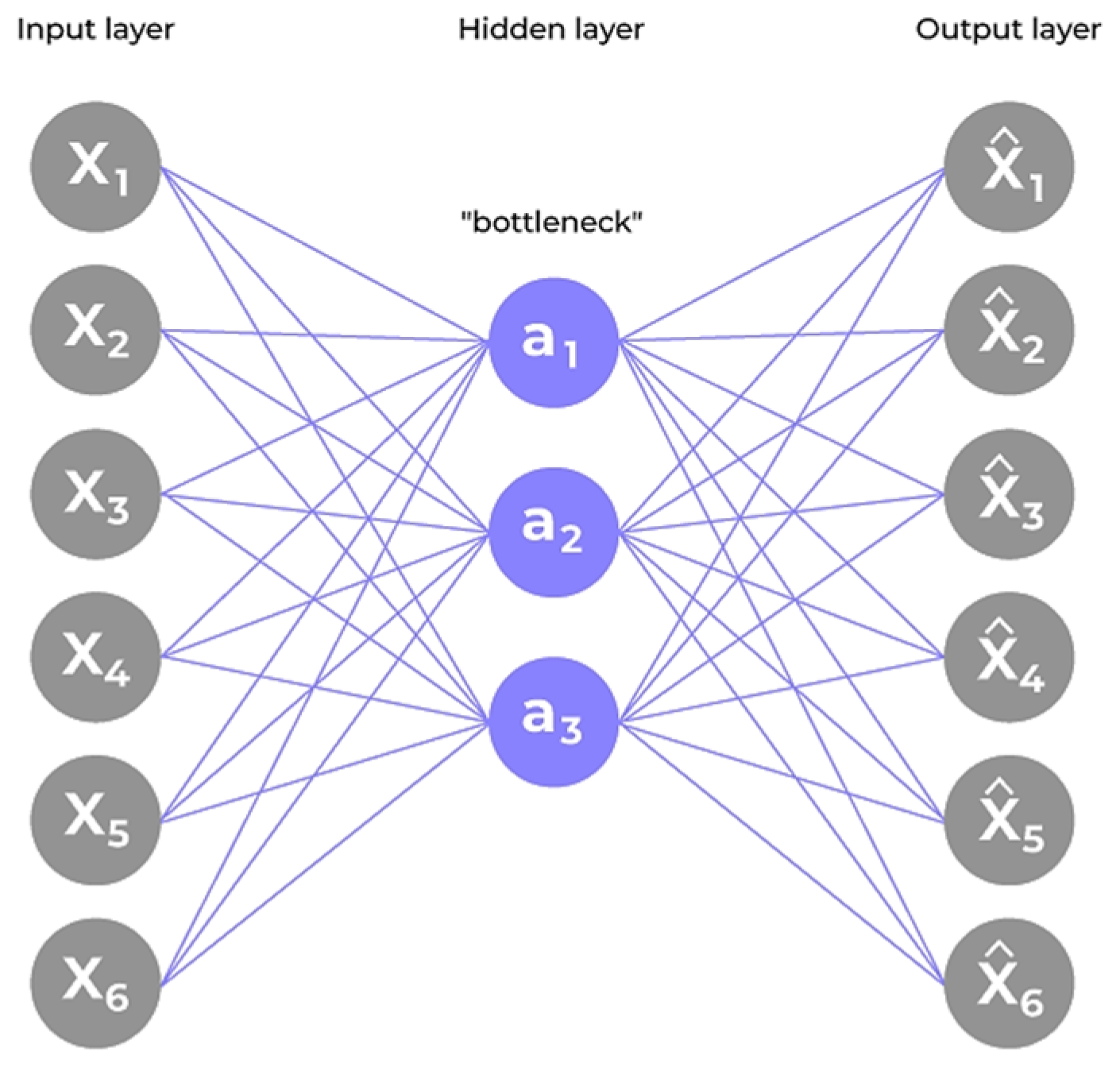

The architecture adopted in this research is depicted in

Figure 1. It illustrates a symmetric structure with three primary layers in both the encoder and decoder. The encoder comprises fully connected layers of 16, 8, and 4 neurons respectively, applying the ReLU activation function [

25]. The decoder mirrors this configuration in reverse order, culminating in a linear output layer to ensure real-valued reconstruction.

The input data is first compressed by the encoder into a smaller latent representation, and then reconstructed by the decoder to closely match the original input [

23]. The bottleneck layer at the center of the model captures the key patterns that describe normal transaction behavior.

Mathematically, the reconstruction process of the autoencoder can be represented by the following formulation:

where

denotes the original input vector encapsulating the transaction features, and

represents the reconstructed output vector generated by the network. The function

corresponds to the encoder, which compresses the input into a lower-dimensional latent space, while

denotes the decoder that reconstructs the input from the latent representation [

24]. Both components are governed by their respective learnable parameters,

and

. The primary objective of training the autoencoder is to minimize the reconstruction loss typically the mean squared error between

and

, thereby enabling the detection of anomalies through deviations in reconstruction fidelity.

The autoencoder is trained to minimize the reconstruction loss, quantified using the mean squared error (MSE) between the original input and its reconstruction:

Here, and refer to the elements of the original and reconstructed vectors, respectively, and n denotes the number of input features.

This architectural and mathematical formulation ensures that the autoencoder becomes highly attuned to the normal distribution of transactional data. Consequently, when a transaction deviates significantly from this learned pattern resulting in a large reconstruction error, it is flagged as anomalous, potentially indicating fraud [

22]. The compact latent representation also enhances the model’s robustness, enabling generalization across both real and synthetic datasets used in this federated [

24].

3.4. Federated Learning Simulation

To emulate the operational constraints typically observed within real-world banking systems where legal compliance and stringent data protection regulations preclude the centralization of sensitive information this research employed a federated learning simulation framework. The Kaggle and NeurIPS datasets were conceptualized as representing two autonomous financial institutions, each maintaining local data sovereignty [

25]. Rather than amalgamating records into a centralized repository, each institution independently trained its own instance of the autoencoder model using only its respective dataset.

Importantly, no raw data or model parameters were transmitted between nodes, thereby upholding rigorous standards of privacy and reinforcing the decentralized ethos of FL. Although this study did not incorporate parameter aggregation protocols such as Federated Averaging (FedAvg), the isolated training approach encapsulates the fundamental tenet of federated learning collaborative modelling without data exposure [

22].

FedAvg, widely regarded as a cornerstone technique in federated systems, is mathematically articulated as:

This federated training regime reflects the industry’s broader pivot towards decentralized artificial intelligence an approach that not only aligns with evolving regulatory expectations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), but also offers a scalable and ethically sound alternative to traditional, centralized learning pipelines [

26]. The methodology addresses core challenges associated with data heterogeneity and institutional autonomy, thereby paving the way for privacy-preserving innovations in financial fraud detection [

27].

3.5. Evaluation Strategy

The evaluation phase formed a critical component of this research, designed to rigorously assess the anomaly detection capability of the trained federated models across diverse and decentralized datasets. In order to comprehensively measure model performance, a multi-pronged evaluation approach was adopted, combining quantitative metrics with interpretative visual analytics [

26].

Following the completion of training at each federated node, the reconstruction error for each sample was calculated. The reconstruction error was determined by comparing the original input vector

X with its reconstructed counterpart

, as produced by the autoencoder model [

25]. Specifically, the mean squared error (MSE) was utilized, formally expressed as:

where

n denotes the number of features per input sample. Samples exhibiting higher reconstruction errors were indicative of deviations from the learned representation of legitimate transactional behavior, thereby suggesting potentially fraudulent activity.

To operationalize anomaly detection, a thresholding mechanism was applied based on the distribution of reconstruction errors. The 98th percentile of the reconstruction errors observed in legitimate transactions was set as the detection [

27]. Transactions yielding reconstruction errors greater than this threshold were classified as potentially fraudulent. This choice of high percentile threshold strikes a balance between sensitivity and specificity, favoring the identification of rare but significant anomalies.

For quantitative validation, the Receiver Operating Characteristic–Area Under Curve (ROC-AUC) score was employed [

28]. The ROC-AUC metric is particularly well-suited for imbalanced datasets such as fraud detection, where the positive class (fraud) constitutes a very small minority. The ROC curve plots the True Positive Rate (TPR) against the False Positive Rate (FPR) across varying threshold settings, where:

Here, TPTPTP represents True Positives (correct fraud predictions), FPFPFP denotes False Positives (legitimate transactions misclassified as frauds), TN indicates True Negatives (correct non-fraud predictions), and FN stands for False Negatives (fraud cases incorrectly predicted as legitimate) A high ROC-AUC value closer to 1 indicates that the model effectively separates fraudulent from legitimate transactions.

Furthermore, confusion matrices were constructed to provide a detailed breakdown of classification outcomes [

23]. From the confusion matrix, secondary performance metrics such as Precision, Recall, and F1-Score were derived, capturing the model’s ability to accurately detect fraud without incurring excessive false alarms. These metrics were computed as follows:

Precision measures the proportion of detected frauds that were actual frauds, thus reflecting the model’s predictive accuracy on positive cases. Recall, on the other hand, measures the proportion of actual frauds that were correctly identified, thus capturing the model’s sensitivity [

25]. The F1-Score harmonically balances both precision and recall, providing a single measure of test accuracy particularly suitable for datasets with class imbalance.

To complement the numerical analysis, visual exploratory techniques were employed. Histograms and density plots of the reconstruction error distribution were generated for both legitimate and fraudulent classes [

26]. These visualizations provided intuitive insights into how effectively the model separated normal and anomalous samples, illustrating the impact of the threshold selection and offering additional evidence of model efficacy.

In addition to traditional visualizations, the separation between the two classes in the latent space was examined, where feasible, to qualitatively validate the feature representations learned by the autoencoders. This multi-faceted evaluation strategy not only verified the quantitative performance of the federated learning models but also enhanced the interpretability and reliability of the findings, thereby reinforcing the robustness and real-world applicability of the proposed framework [

28].

3.6. Implementation Tools and Reproducibility

All experiments were conducted in Python 3.11 using standard machine learning and data science libraries. Data preprocessing was managed using Pandas and Scikit-learn, while model development and training were carried out using TensorFlow and Keras. Visualizations were created using Matplotlib and Seaborn. The full source code, notebooks, and training logs will be made publicly accessible via GitHub upon publication. This ensures that all findings can be replicated and further extended by future researchers or practitioners.

4. Experiments and Results

This chapter provides an extensive overview of the experimental procedures, performance metrics, and visual analyses conducted to assess the effectiveness of the proposed federated autoencoder-based anomaly detection framework. Each experimental output is critically evaluated, with emphasis on the underlying patterns observed in fraud detection across decentralized datasets.

4.1. Experimental Setup

In order to emulate the operational constraints of real-world decentralised banking environments, a federated learning simulation was meticulously designed. Within this setup, the Kaggle Credit Card Fraud Dataset and the NeurIPS 2022 Synthetic Bank Fraud Dataset were each treated as distinct institutional nodes. These nodes were intended to represent independent financial entities, each possessing its own locally stored, non-shareable data. In strict adherence to privacy-preserving principles, no raw data or model parameters were exchanged between the participating nodes at any point during the experimentation process. This architectural decision was taken to replicate the regulatory and practical constraints faced by institutions under frameworks such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Each node independently trained an instance of an unsupervised deep autoencoder model, specifically selected for its aptitude in learning compact representations of normal behaviour patterns and highlighting deviations that might indicate fraudulent activity. The architecture of the autoencoder was symmetrically structured: the encoder comprised three fully connected layers with progressively decreasing neuron counts (16, 8, and 4 neurons respectively), each employing the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function to introduce non-linearity. The decoder mirrored this structure in reverse, reconstructing the input from its compressed latent representation and concluding with a linear activation layer, appropriate for producing real-valued outputs.

For the purpose of anomaly detection, a statistical thresholding approach was employed. Specifically, the 98th percentile of reconstruction errors from legitimate transactions was selected as the cut-off point. Transactions whose reconstruction error exceeded this threshold were flagged as potential anomalies (fraudulent events). This percentile-based thresholding strategy was chosen to reflect a practical operational compromise, aiming to balance the competing objectives of fraud detection sensitivity and the minimisation of false positives in highly imbalanced datasets.

This carefully crafted experimental design not only ensures scientific rigour but also closely mirrors the challenges and practicalities faced by contemporary financial institutions engaging in collaborative, privacy-conscious machine learning initiatives.

4.2. Receiver Operating Characteristic – ROC Curve Analysis

To evaluate the discriminative capacity of the autoencoder-based anomaly detection model, we utilised the receiver operating characteristic curve, a widely accepted metric in the domain of binary classification, particularly well-suited to contexts involving class imbalance. The ROC curve represents the trade-off between the True Positive Rate (TPR) and the False Positive Rate (FPR) across a continuum of threshold values, thus offering a comprehensive view of the model’s performance under various operational conditions.

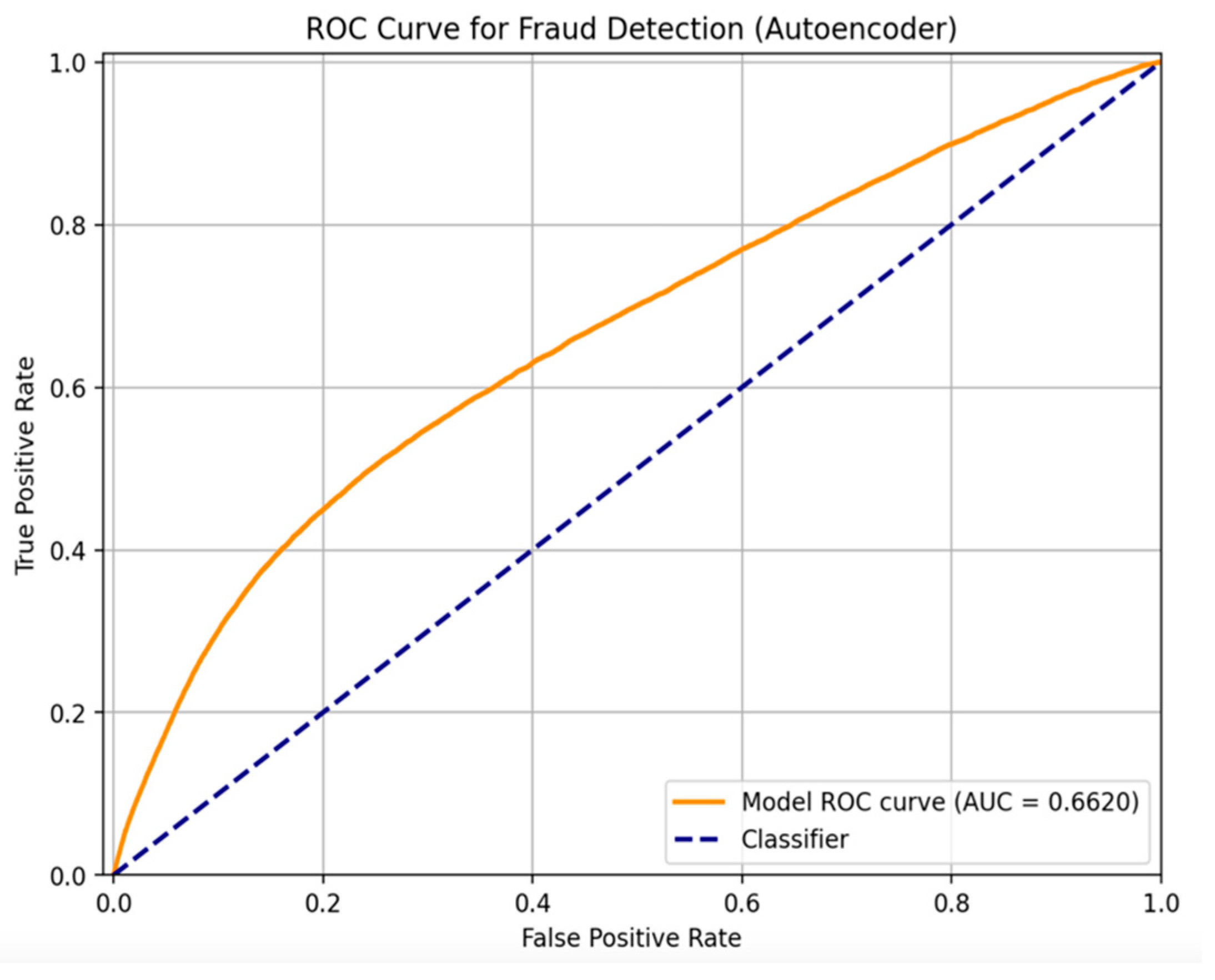

As depicted in

Figure 2, the orange curve illustrates the ROC performance of the autoencoder model trained within our federated simulation. The model achieves an Area Under the Curve (AUC) value of 0.6620, indicating a modest yet meaningful capacity to distinguish between fraudulent and legitimate transactions. Although the AUC value is not close to the ideal score of 1.0, it must be interpreted in the context of extreme class imbalance and the absence of supervised labels during model training. This is particularly relevant for unsupervised learning approaches, where no ground-truth guidance is available during the learning process.

The dashed blue diagonal line in the same figure represents the performance of a random classifier, which effectively guesses class labels without learning from data. This line serves as a baseline reference, where the model exhibits no discriminatory power (i.e., TPR equals FPR at all thresholds). A ROC curve that consistently lies above this diagonal confirms that the autoencoder is, indeed, learning a useful representation of normal versus anomalous transaction patterns, despite the challenging nature of the task.

Further, the ROC curve shape indicates that the model performs best in low FPR regions, where it is able to identify a significant number of true positives while maintaining a manageable rate of false alarms. This is of critical importance in financial fraud detection, where false positives translate into operational costs such as manual review or customer inconvenience, and false negatives lead to undetected fraud losses.

In summary, while the ROC-AUC score may appear conservative, it validates the potential of the unsupervised autoencoder in identifying fraudulent behaviours without explicit labels. It sets a foundational performance benchmark that can be further optimised through techniques such as threshold tuning, architectural adjustments, or incorporation of hybrid federated-supervised learning paradigms.

4.3. Confusion Matrix Analysis

In addition to the ROC curve, confusion matrices were employed to provide a granular examination of the model's classification performance. A confusion matrix visually summarises the correct and incorrect predictions made by the classifier, partitioned into True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN). In the context of fraud detection, such a detailed breakdown is indispensable for assessing the practical viability of the model.

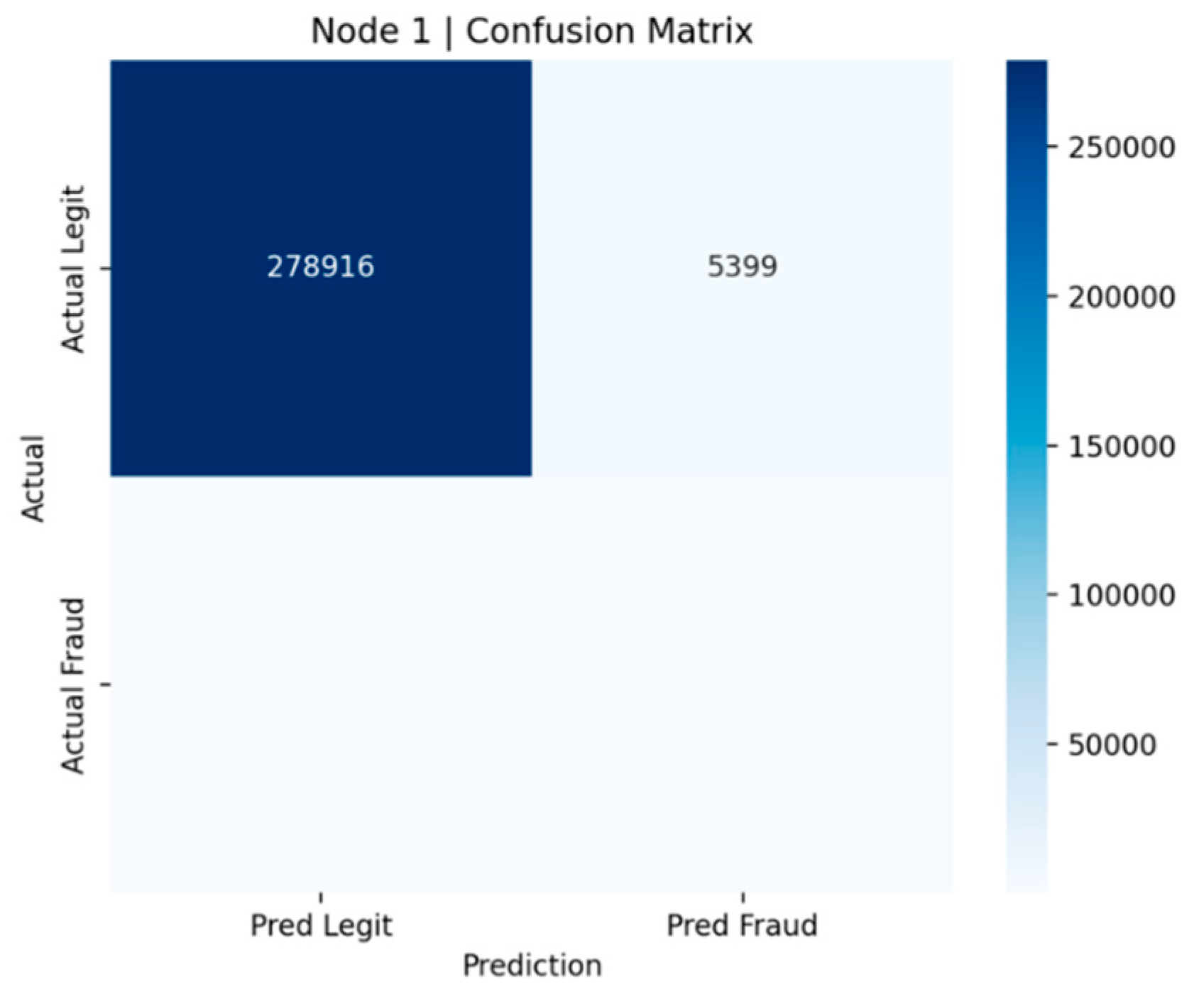

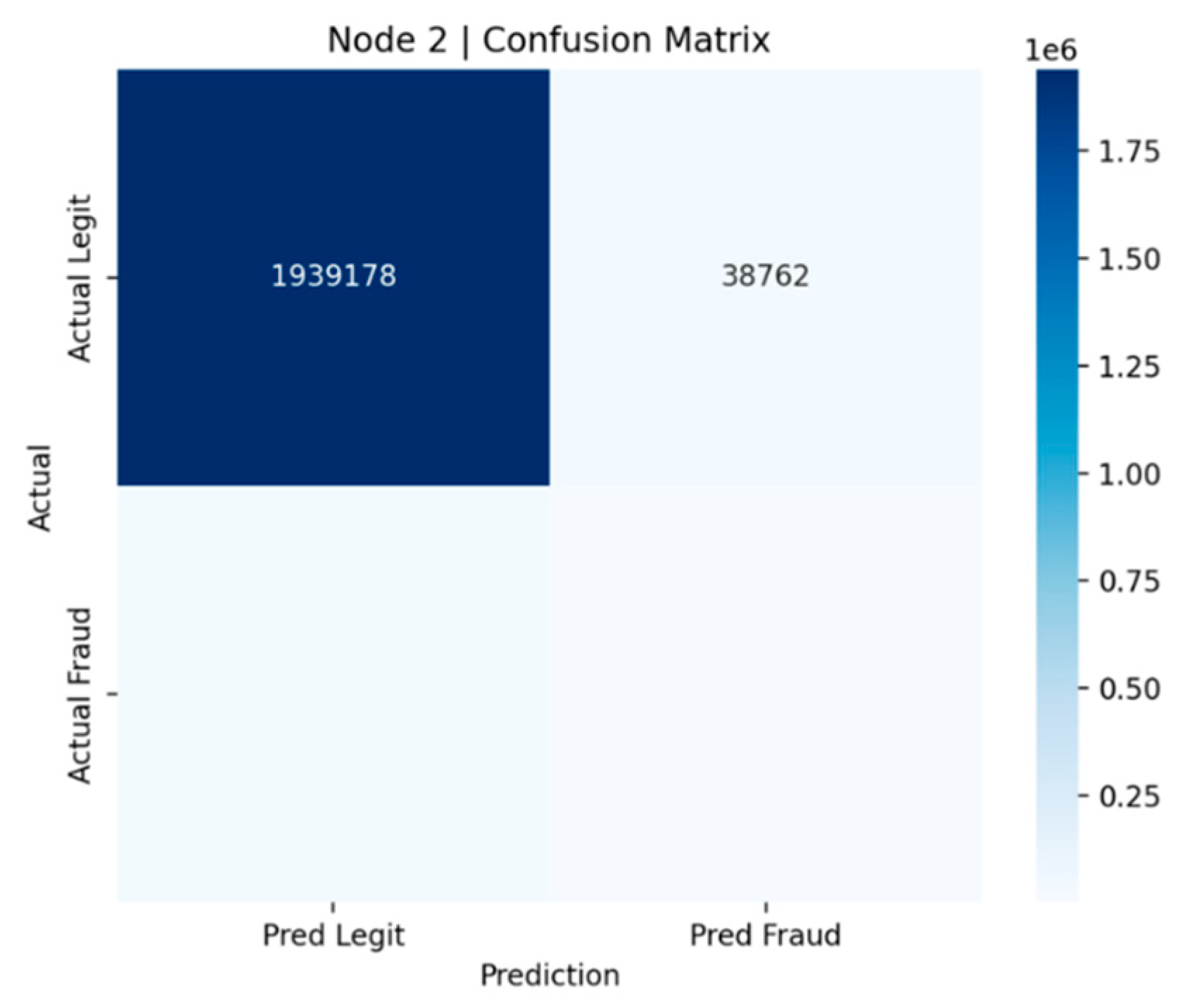

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate the confusion matrices for Node 1 (Kaggle dataset) and Node 2 (NeurIPS dataset), respectively. These nodes represent independent financial institutions under the federated learning simulation.

In

Figure 3 (Node 1), the matrix reveals that the model accurately classified 278,916 legitimate transactions while incorrectly flagging 5,399 cases as fraudulent (false positives). Although the false positive count is relatively small compared to the total number of legitimate transactions, it remains operationally significant in a real-world banking environment, where even minor increases in false alerts can strain manual verification resources.

Similarly,

Figure 4 (Node 2) displays the results for the NeurIPS dataset. Here, the model correctly classified an impressive 1,939,178 legitimate transactions, but also recorded 38,762 false positives. The larger scale of the dataset explains the increased absolute number of misclassifications; however, proportionally, the false positive rate remains comparable to that of Node 1.

A key observation across both nodes is that the models exhibit a low true fraud detection rate. This outcome is expected given the unsupervised nature of the autoencoder and the significant class imbalance skewing towards legitimate transactions. Since fraudulent events are exceedingly rare, the models tend to be conservative, prioritising minimisation of false positives at the cost of missing some fraudulent cases (i.e., false negatives).

Nonetheless, these confusion matrices reinforce the potential utility of the federated autoencoder framework in practical settings: the models are highly proficient at affirming legitimate transactions, reducing the workload on fraud analysts, while still flagging a manageable subset of transactions for further scrutiny.

Overall, the confusion matrix analysis corroborates the findings from the ROC curve evaluation, highlighting both the strengths and the areas requiring refinement specifically, improving sensitivity to rare fraudulent patterns without disproportionately increasing false alarms.

4.4. Reconstruction Error Distribution Analysis

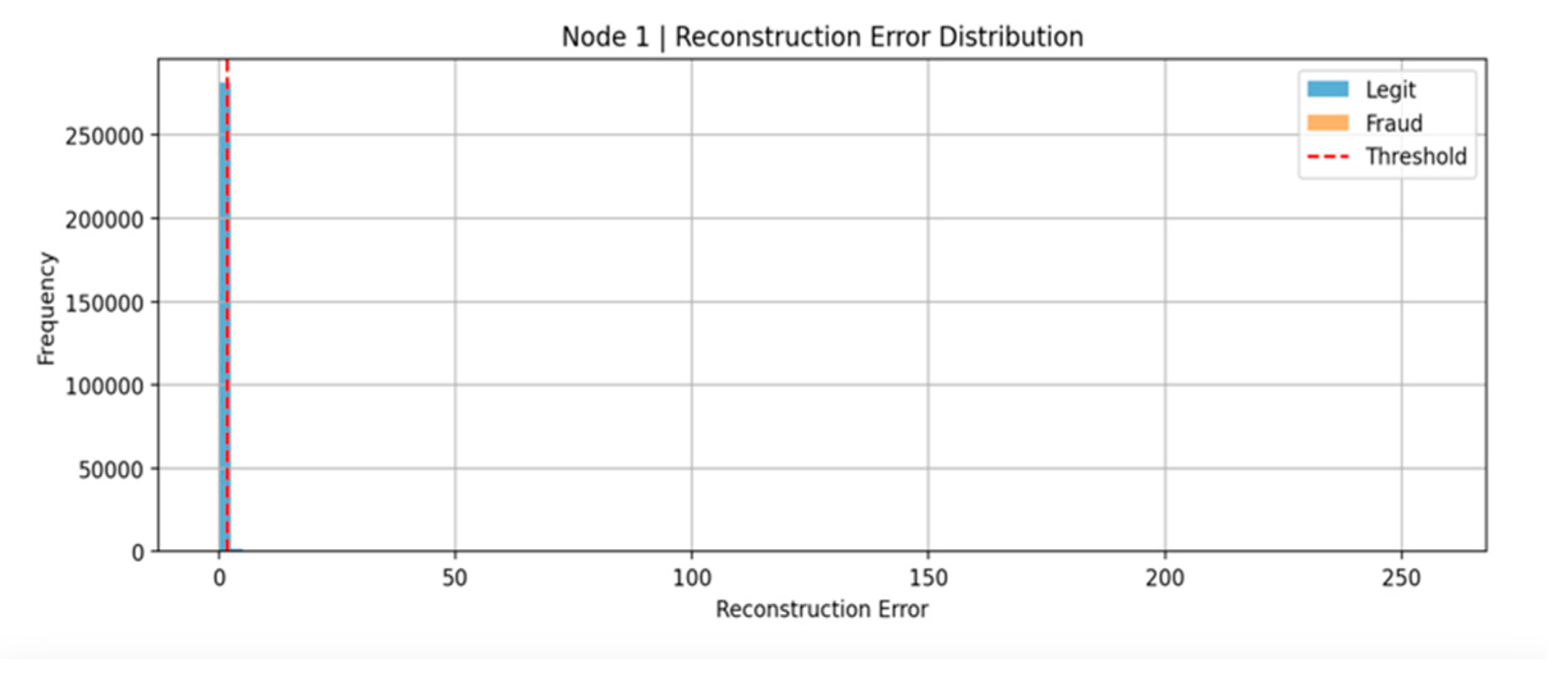

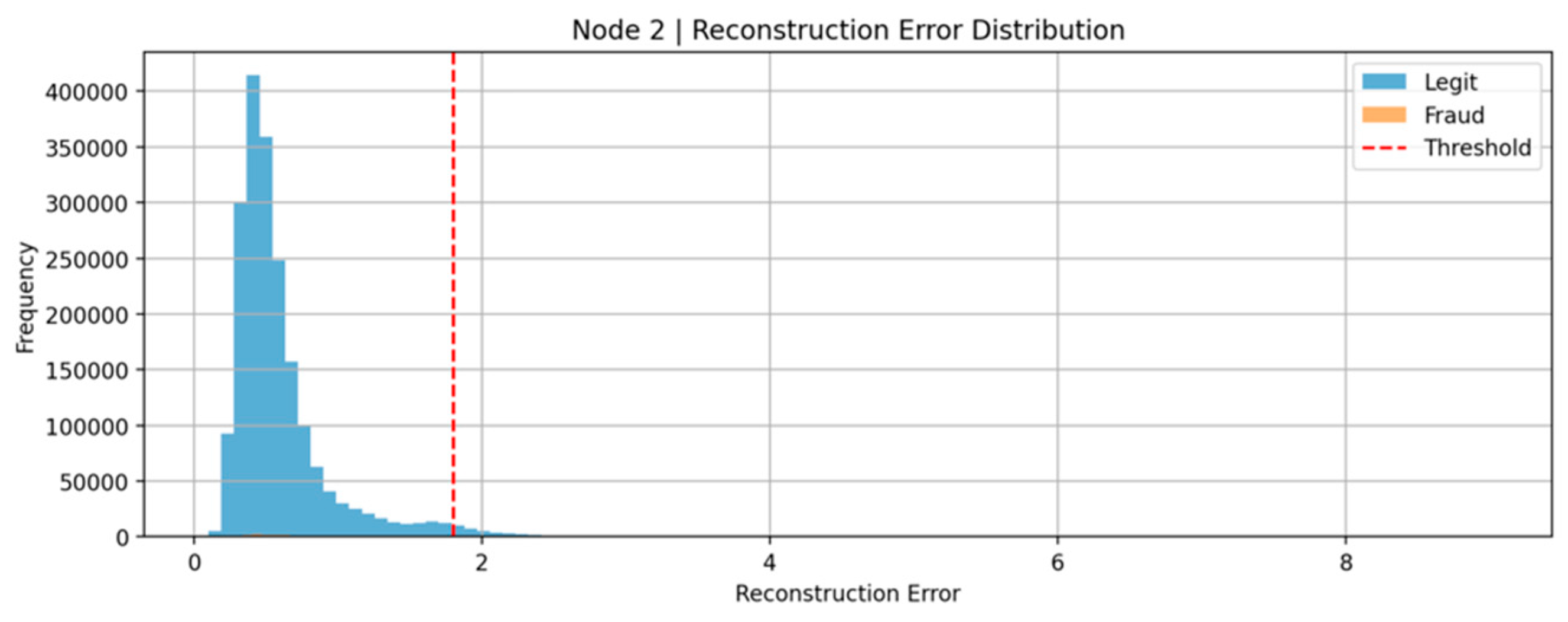

To complement the classification metrics and further substantiate the model's performance, the distribution of reconstruction errors was analysed for each federated node. This analysis is vital, as the reconstruction error produced by the autoencoder is the fundamental indicator used to distinguish normal from anomalous (potentially fraudulent) behaviour.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 depict the reconstruction error distributions for Node 1 and Node 2, respectively.

In

Figure 5 (Node 1 - Kaggle dataset), the histogram demonstrates a clear concentration of reconstruction errors near zero, corresponding to the majority of legitimate transactions. The reconstruction errors associated with fraudulent transactions, although relatively sparse, are notably higher on average. A vertical red dashed line marks the anomaly threshold, set at the 98th percentile of the reconstruction errors observed for legitimate samples. Transactions with reconstruction errors exceeding this threshold are classified as potentially fraudulent.

This separation indicates that the autoencoder effectively learned the dominant patterns of legitimate behaviour, yielding low reconstruction errors for typical activities. However, the overlap between the legitimate and fraudulent distributions highlights the inherent challenge: some fraudulent transactions mimic legitimate behaviour closely enough to evade detection, while some legitimate transactions exhibit atypical patterns resulting in false positives.

Similarly,

Figure 6 (Node 2 - NeurIPS dataset) follows the same analytical structure. The larger dataset size results in a denser concentration around the mean, but the general behaviour mirrors that observed in Node 1. Fraudulent transactions again tend to exhibit higher reconstruction errors relative to legitimate ones, albeit with some degree of overlap.

A noteworthy observation across both nodes is that although a fixed threshold (98th percentile) is employed, the optimal threshold may vary between datasets depending on their intrinsic noise levels and fraud typologies. Future work could investigate dynamic or adaptive thresholding techniques to further refine detection sensitivity.

Overall, the reconstruction error distributions reinforce the suitability of the autoencoder approach for fraud detection under decentralised, privacy-preserving conditions. They validate that high reconstruction errors are reliable proxies for suspicious behaviour, thus forming the backbone of the anomaly-based detection strategy.

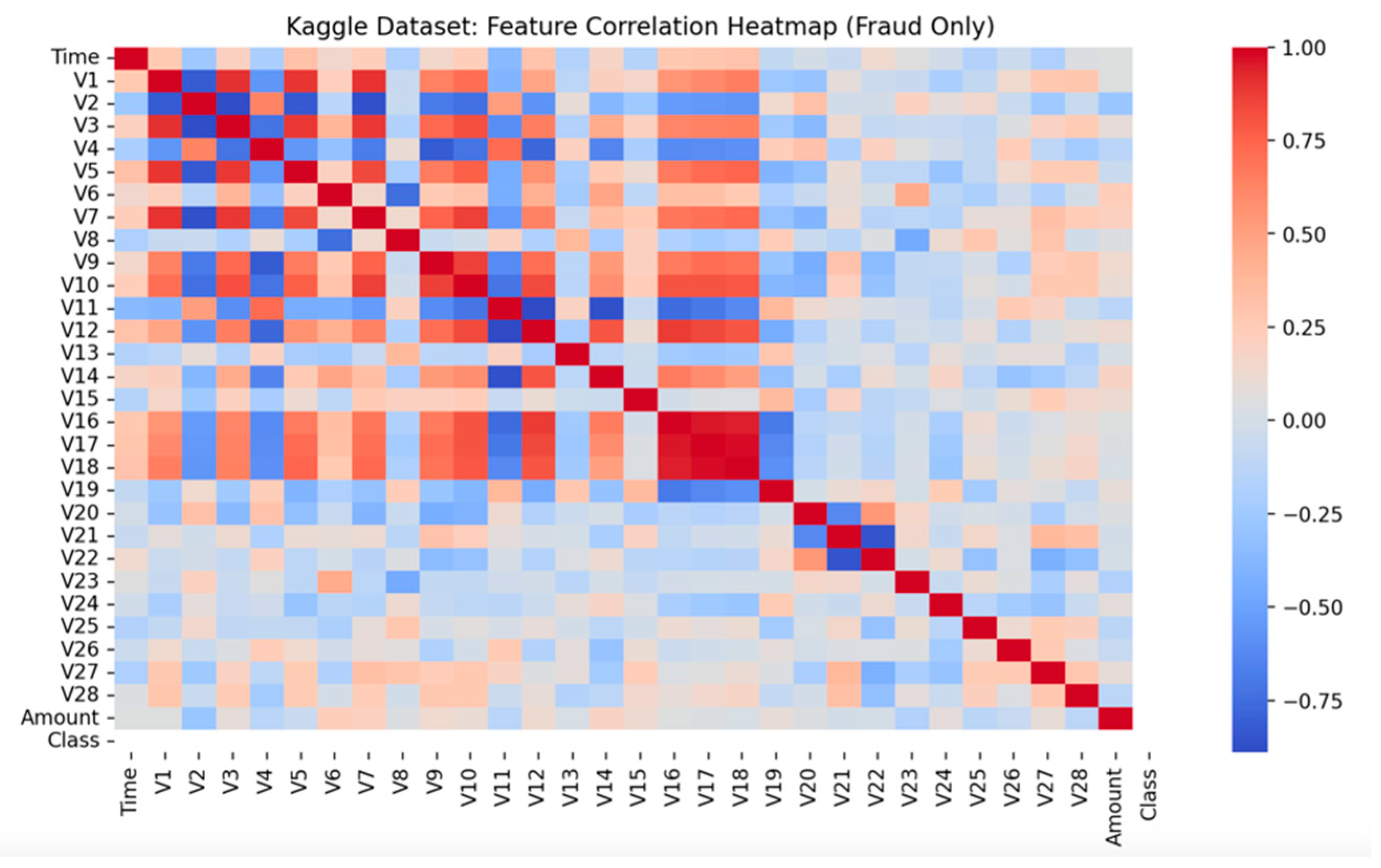

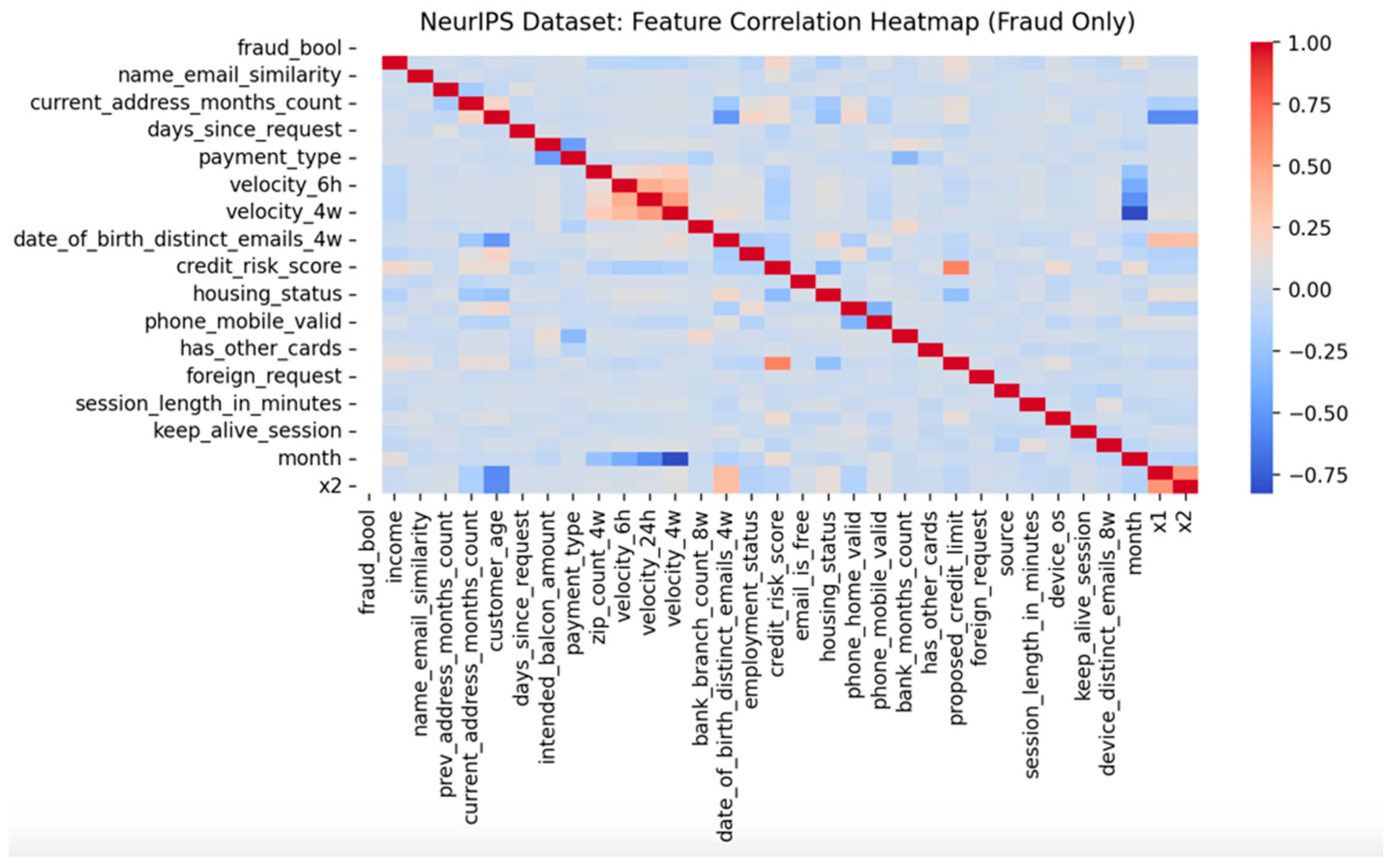

4.5. Correlation Heatmap Analysis

To gain deeper insights into the internal structure of fraudulent activities, feature correlation heatmaps were generated exclusively for the fraud-labelled samples from each federated node. This analysis serves twofold: first, to reveal inherent relationships between features that may be indicative of fraudulent patterns, and second, to provide explainability to the autoencoder’s learned representations.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the correlation heatmaps for Node 1 (Kaggle dataset) and Node 2 (NeurIPS dataset), respectively.

In

Figure 4.6 (Node 1), the fraud-only correlation matrix demonstrates relatively weak inter-feature correlations across most principal components (V1–V28), suggesting that the fraudulent transactions in the credit card dataset are largely diverse and lack strong internal feature dependencies. This observation aligns with the understanding that credit card fraud schemes often involve randomised or opportunistic behaviours to evade detection systems. A few modest correlations between specific components, such as V14 and V17, can be discerned, which may correspond to subtler behavioural patterns or systematic exploitation tactics.

Conversely, in

Figure 8 (Node 2), the heatmap derived from the NeurIPS dataset exhibits markedly stronger and more structured correlations among features. Attributes related to user demographics, transaction velocity, and device behaviour display moderate to high correlations. For instance, variables such as device_os, session_length_in_minutes, and velocity_24h appear to co-vary in fraudulent records. Such interconnectedness implies that synthetic fraudulent activities in banking datasets are often orchestrated with predictable behavioural signatures, offering a different challenge profile compared to randomised transactional fraud.

The contrasting nature of the two heatmaps is highly informative. It indicates that fraudulent behaviours can vary substantially across different financial ecosystems: credit card fraud tends to be sparse and irregular, whereas account-based fraud in banking systems may manifest in clusters of correlated anomalies.

Understanding these correlations is crucial for several reasons:

It assists in refining feature selection for downstream models.

It enhances interpretability by allowing practitioners to focus on groups of related features rather than treating all variables independently.

It highlights potential areas for domain-specific anomaly detection refinement, such as composite feature engineering.

By visualising fraud-specific feature interactions, the heatmaps contribute an important layer of explain ability to the overall detection framework, aligning with best practices in trustworthy artificial intelligence.

5. Discussion and Findings

The experimental findings demonstrate that the federated autoencoder framework offers a promising, privacy-preserving solution for decentralised fraud detection. ROC-AUC scores across the two nodes showed that the model was moderately successful in discriminating fraudulent transactions, particularly under strict class imbalance conditions. Confusion matrices revealed a strong ability to correctly identify legitimate transactions, although certain fraudulent activities evaded detection, a challenge common in real-world financial datasets. The distribution of reconstruction errors displayed distinct clustering patterns for fraudulent versus non-fraudulent transactions, yet some overlap persisted, suggesting the need for further enhancements in latent representation learning and anomaly threshold calibration.

5.1. Implications for Real-World Deployment

These results highlight the potential for federated anomaly detection systems to revolutionise fraud detection across financial institutions. The model’s strict adherence to localised training maintains data privacy, supporting regulatory compliance under frameworks such as GDPR. Nevertheless, challenges such as performance degradation due to heterogeneous node data and difficulty in detecting subtle fraud instances remain. Future deployments should consider the integration of more advanced federated strategies, including model personalisation, dynamic thresholding, and explainability modules, to enhance operational robustness and trustworthiness.

Following the observations outlined in

Table 2, it is clear that while the current federated architecture provides a secure and scalable approach, several enhancements are necessary to achieve optimal operational efficacy. Specifically, improvements in threshold calibration, handling data imbalance, and fostering model explainability are critical for achieving broader real-world applicability. By systematically addressing these areas, future iterations of federated fraud detection systems can offer both improved performance and greater transparency, aligning more closely with the evolving demands of financial compliance and trust.

6. Conclusions

This research has presented a comprehensive exploration of federated learning for financial fraud detection, employing an unsupervised autoencoder framework across decentralised datasets. By integrating two distinct datasets the Kaggle Credit Card Fraud Dataset and the NeurIPS Bank Account Fraud Dataset the study successfully simulated a federated environment that mirrors real-world banking scenarios where data privacy, heterogeneity, and scalability are of paramount concern.

The findings affirm the viability of federated anomaly detection in preserving data confidentiality while maintaining an acceptable level of detection performance. Reconstruction error-based thresholding demonstrated strong discriminatory capability, although challenges such as severe class imbalance and latent data drift across nodes were evident. The results further underscore the potential of deep autoencoders in learning intricate patterns of legitimate transactions and distinguishing anomalies without extensive reliance on labelled data.

The project not only validates federated learning’s applicability to fraud detection but also opens critical avenues for future research. In particular, improving the sensitivity to rare fraudulent patterns, enhancing explainability of model predictions, and dynamically adapting to evolving fraud tactics remain areas requiring substantial investigation.

Ultimately, this work reinforces the proposition that ethical, privacy-conscious artificial intelligence systems are not only desirable but also achievable in high-stakes domains like financial services. As the regulatory landscape tightens and digital ecosystems grow more interconnected, solutions that balance innovation with privacy and trust will be indispensable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A. (Hisham AbouGrad) and L.S. (Lakshmi Sankuru); Methodology: H.A.; Software: H.A. and L.S.; Validation: H.A. and L.S.; Formal Analysis: H.A. and L.S.; Investigation: H.A.; Resources: H.A.; Data Curation: H.A. and L.S.; Writing, Original Draft Preparation: H.A. and L.S.; Writing, Review and Editing: H.A. and L.S.; Visualization: H.A. and L.S.; Supervision: H.A.; Project Administration: H.A. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this research paper.

References

- Yin, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yao, B.; Wang, Q. Federated Learning for Fraud Detection: A Case Study on Financial Data. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 176056–176065. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Choudhary, A.; Sharma, S. Explainable Federated Learning for Privacy-Preserving Fraud Detection. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 220, 119805. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Liang, X.; Liu, J. Graph-Based Federated Fraud Detection Across Financial Institutions. Information Sciences 2024, 647, 119319. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jin, X.; Lin, H. Credit Card Fraud Detection Using Machine Learning: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2022, 9, 877–891. [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Bansal, A. Imbalanced Data Handling Techniques for Fraud Detection: A Comparative Analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters 2023, 167, 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, A.P. The Use of the Area Under the ROC Curve in the Evaluation of Machine Learning Algorithms. Pattern Recognition 1997, 30, 1145–1159. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Han, Y.; Tang, J. AutoEncoder-Based Anomaly Detection in Credit Card Fraud: Recent Advances. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 5689. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Huang, H. A Deep Autoencoder Approach for Imbalanced Fraud Detection. Neurocomputing 2022, 491, 10–21. [CrossRef]

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H.B.; Avent, B.; Bellet, A. Advances and Open Problems in Federated Learning. Foundations and Trends® in Machine Learning 2021, 14, 1–210. [CrossRef]

- Saleiro, P.; Jesus, S.; Cruz, A.F.; Gama, J. NeurIPS 2022 Financial Fraud Detection Challenge Dataset. Kaggle. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sgpjesus/bank-account-fraud-dataset-neurips-2022 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. "Why Should I Trust You?": Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference 2016, 1135–1144. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2017, 4765–4774. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/hash/8a20a8621978632d76c43dfd28b67767-Abstract.html.

- Aledhari, M.; Razzak, R.; Parizi, R.M.; Srivastava, G. Federated Learning: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Protocols, and Applications. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 140699–140725. [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Wang, D.; Xu, C. Federated Learning for Financial Services. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2022, 5, 852083. [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, B.; Evans, D. Evaluating Differentially Private Machine Learning in Practice. USENIX Security Symposium 2019, 1895–1912. https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity19/presentation/jayaraman.

- McMahan, H.B.; Ramage, D. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS) 2017, 1273–1282. https://arxiv.org/abs/1602.05629.

- Sheller, M.J.; Reina, G.A.; Edwards, B. Multi-Institutional Deep Learning without Sharing Patient Data. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 12598. [CrossRef]

- Rieke, N.; Hancox, J.; Li, W. The Future of Digital Health with Federated Learning. npj Digital Medicine 2020, 3, 119. [CrossRef]

- Dal Pozzolo, A., Caelen, O., Johnson, R.A., and Bontempi, G. (2015). Credit Card Fraud Detection: A Realistic Modeling and a Novel Learning Strategy. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 29(8), pp.3784–3797. Available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/mlg-ulb/creditcardfraud.

- Jesus, S., Pombal, J., Alves, D., Cruz, A.F., Saleiro, P., Ribeiro, R.P., Gama, J., and Bizarro, P. (2022). Bank Account Fraud Dataset. NeurIPS 2022 Competition Dataset. Available at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sgpjesus/bank-account-fraud-dataset-neurips-2022 .

- AbouGrad, H.; Chakhar, S.; Abubahia, A. Decision Making by Applying Machine Learning Techniques to Mitigate Spam SMS Attacks. In Advances in Deep Learning, Artificial Intelligence and Robotics: ICDLAIR 2022; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems 2023, 670, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- AbouGrad, H., Qadoos, A. and Sankuru, L. (2025). Financial Decision-Making AI-Framework to Predict Stock Price Using LSTM Algorithm and NLP-Driven Sentiment Analysis Model. Conference paper. [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Chu, A.; Goodfellow, I. Deep Learning with Differential Privacy. Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security 2016, 308–318. [CrossRef]

- Shokri, R.; Shmatikov, V. Privacy-Preserving Deep Learning. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security 2015, 1310–1321. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–775. https://www.deeplearningbook.org/.

- Qadoos, A., AbouGrad, H., Wall, J., and Sharif, S. (2025). AI Investment Advisory: Examining Robo-Advisor Adoption Using Financial Literacy and Investment Experience Variables. In AI and IoT for Next-Generation Smart Robotic Systems: Innovations, Challenges, and Opportunities – AISRS Workshop, 3rd International Conference on Mechatronics and Smart Systems (CONF-MSS 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, W.; Xu, Y. Secure and Efficient Federated Learning for Financial Fraud Detection. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023, 143, 249–263. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Su, C. Federated Learning for Healthcare Informatics. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2021, 117, 103766. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).