Submitted:

05 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of EA 575® by HPLC Analysis

2.2. Cell Cultures

2.3. Cytotoxicity Assays

2.4. Autophagy and Reactive Oxygen Species Assays

2.5. Alloreactivity Assay

2.6. T Helper Polarization Assay

2.7. Induction of T Regulatory and Exhausted Cells

2.8. Cytokine Assays

2.9. Flow Cytometry

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

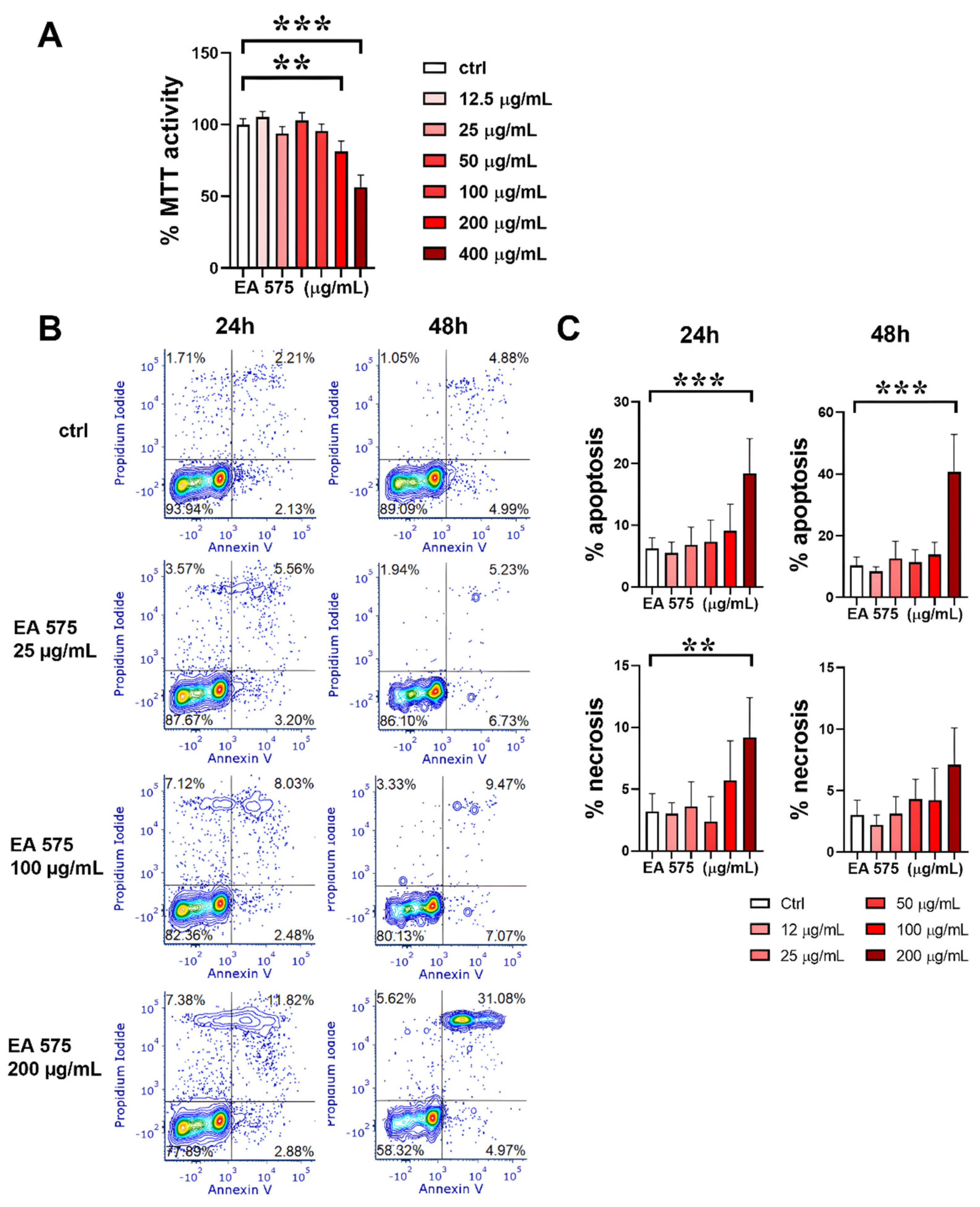

3.1. Cytotoxicity of EA 575

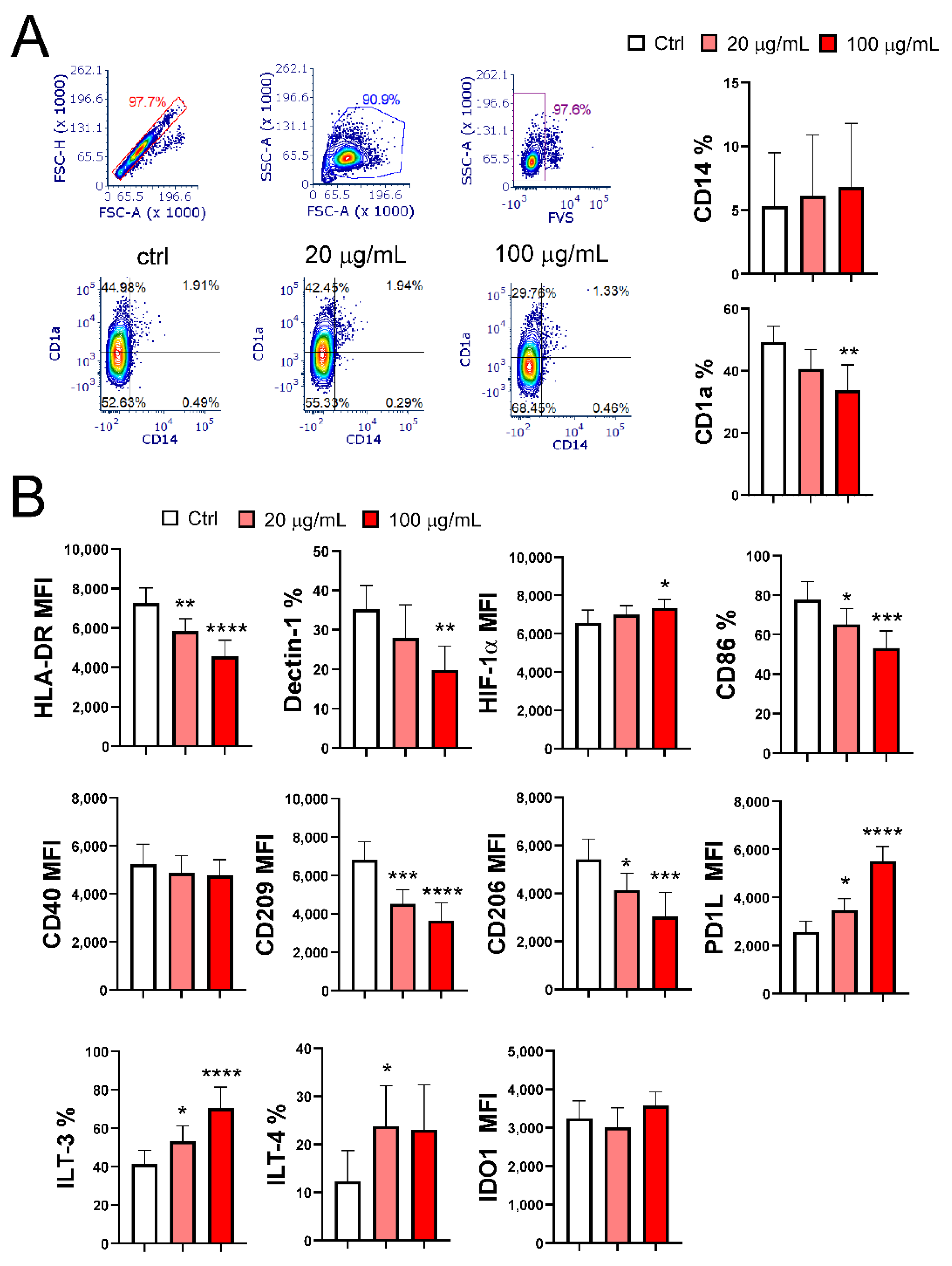

3.2. EA 575 Impairs the Differentiation of MoDCs

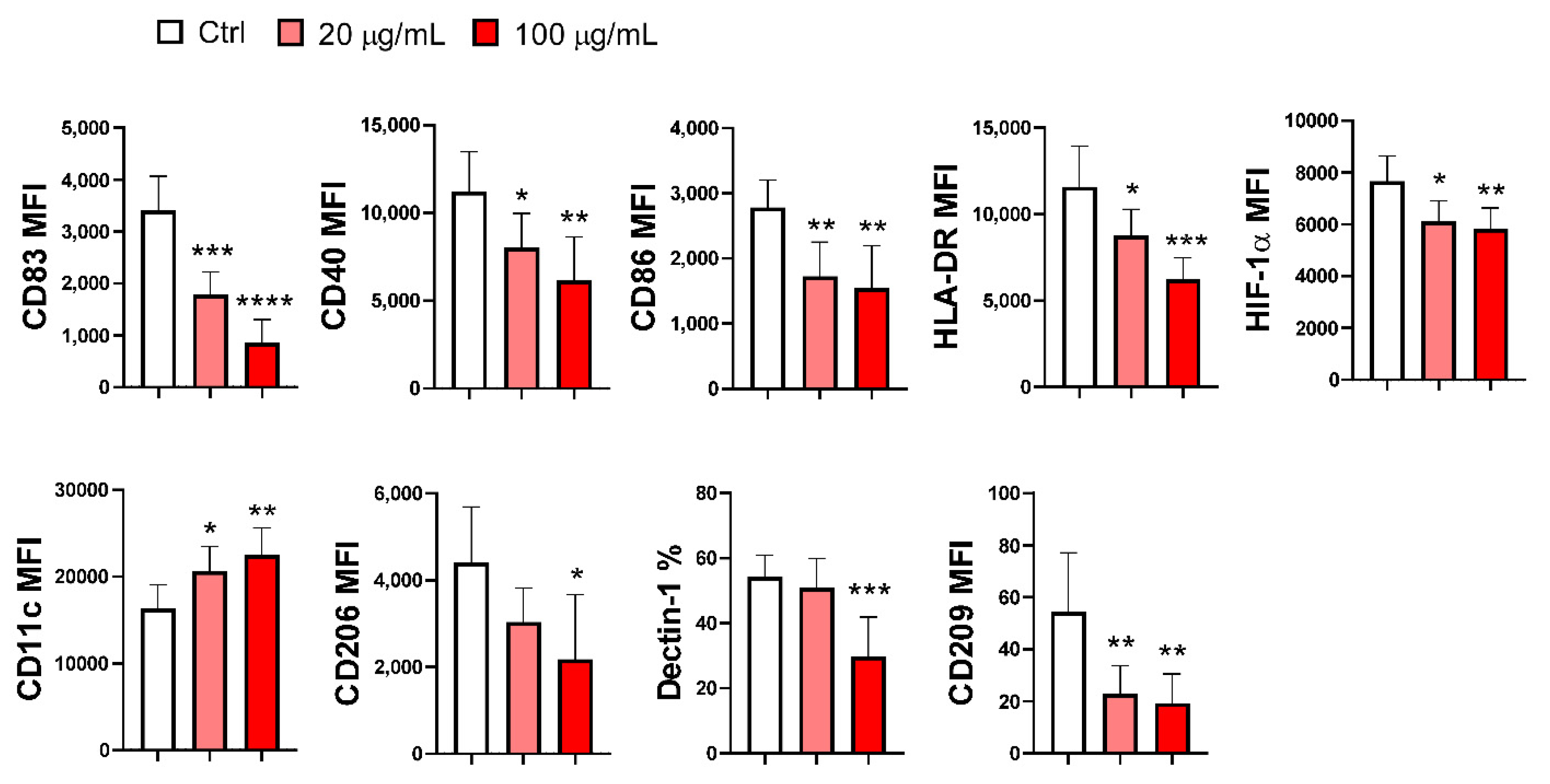

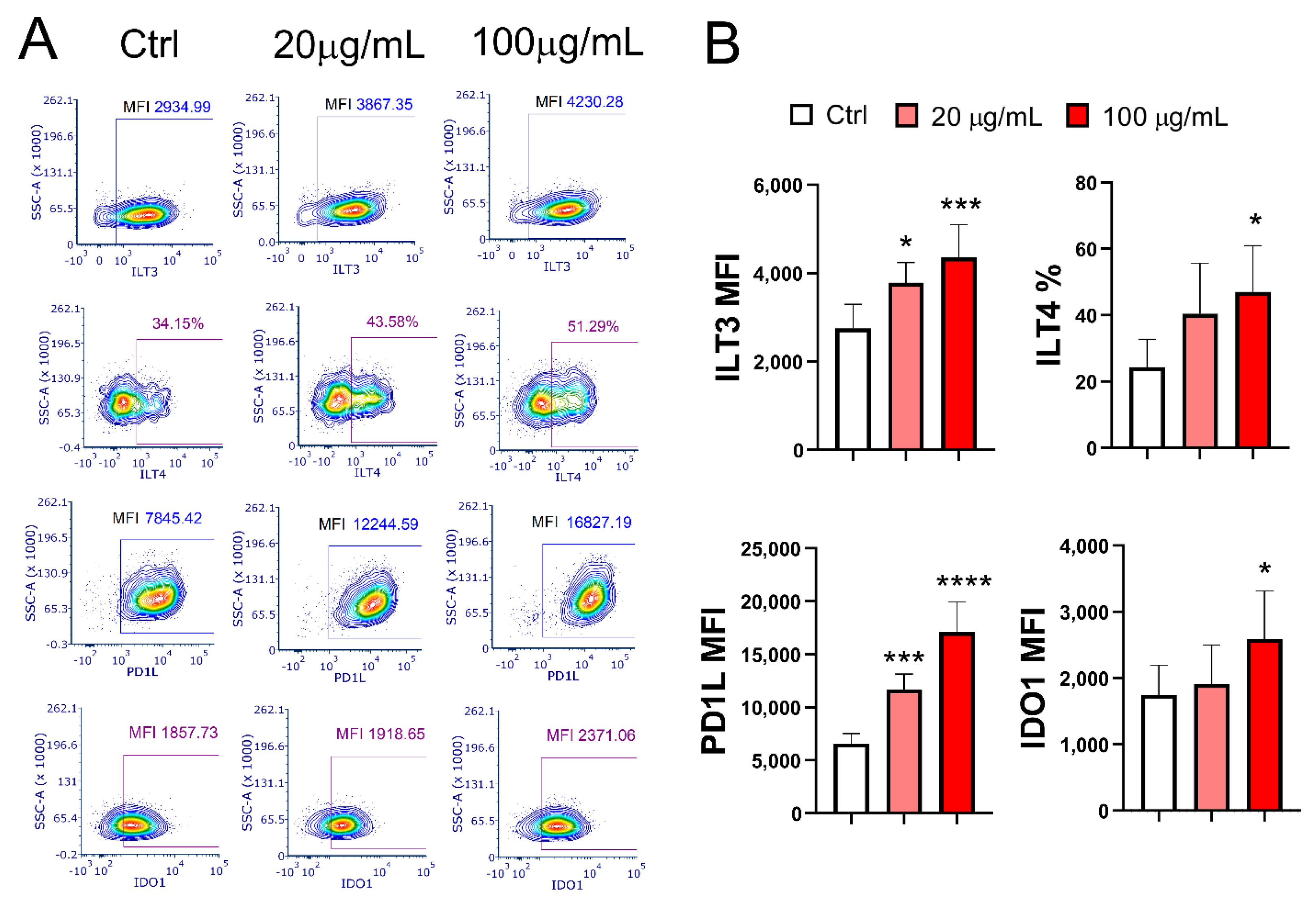

3.3. EA 575 Impairs the Phenotypic Maturation of MoDCs

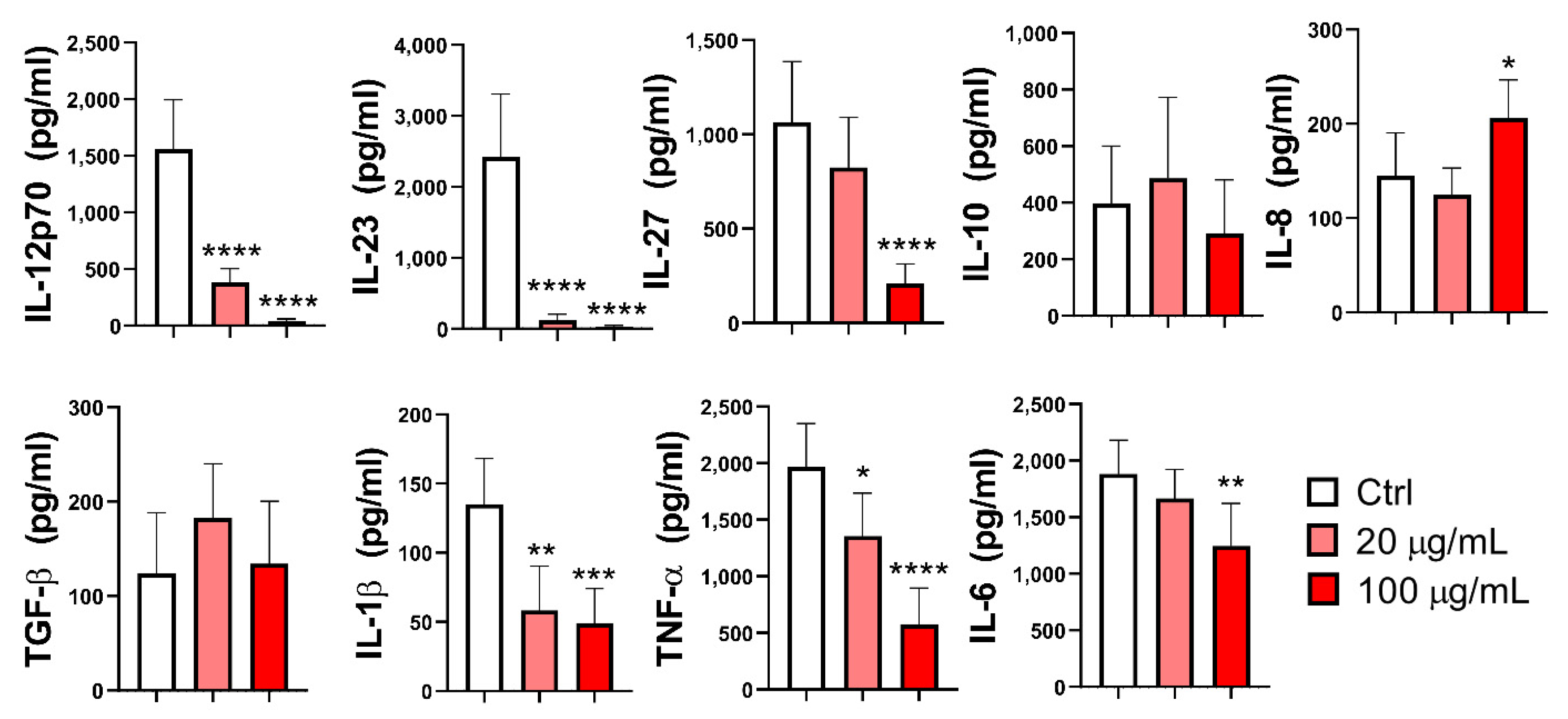

3.4. Effect of EA 575 on the Production of Cytokines by MoDCs

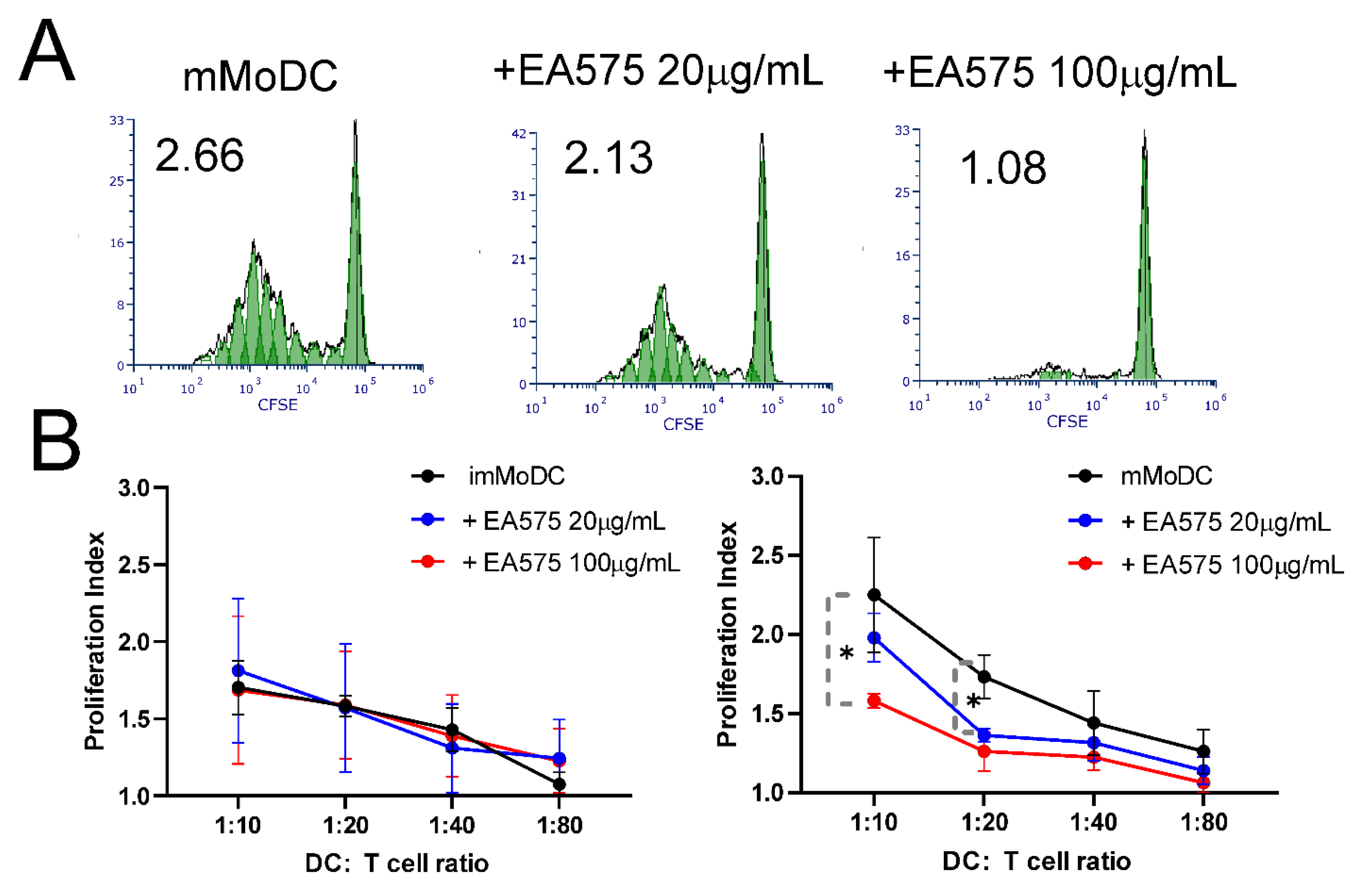

3.5. Effect of EA 575-Treated MoDCs on the Proliferation of Alloreactive T Cells

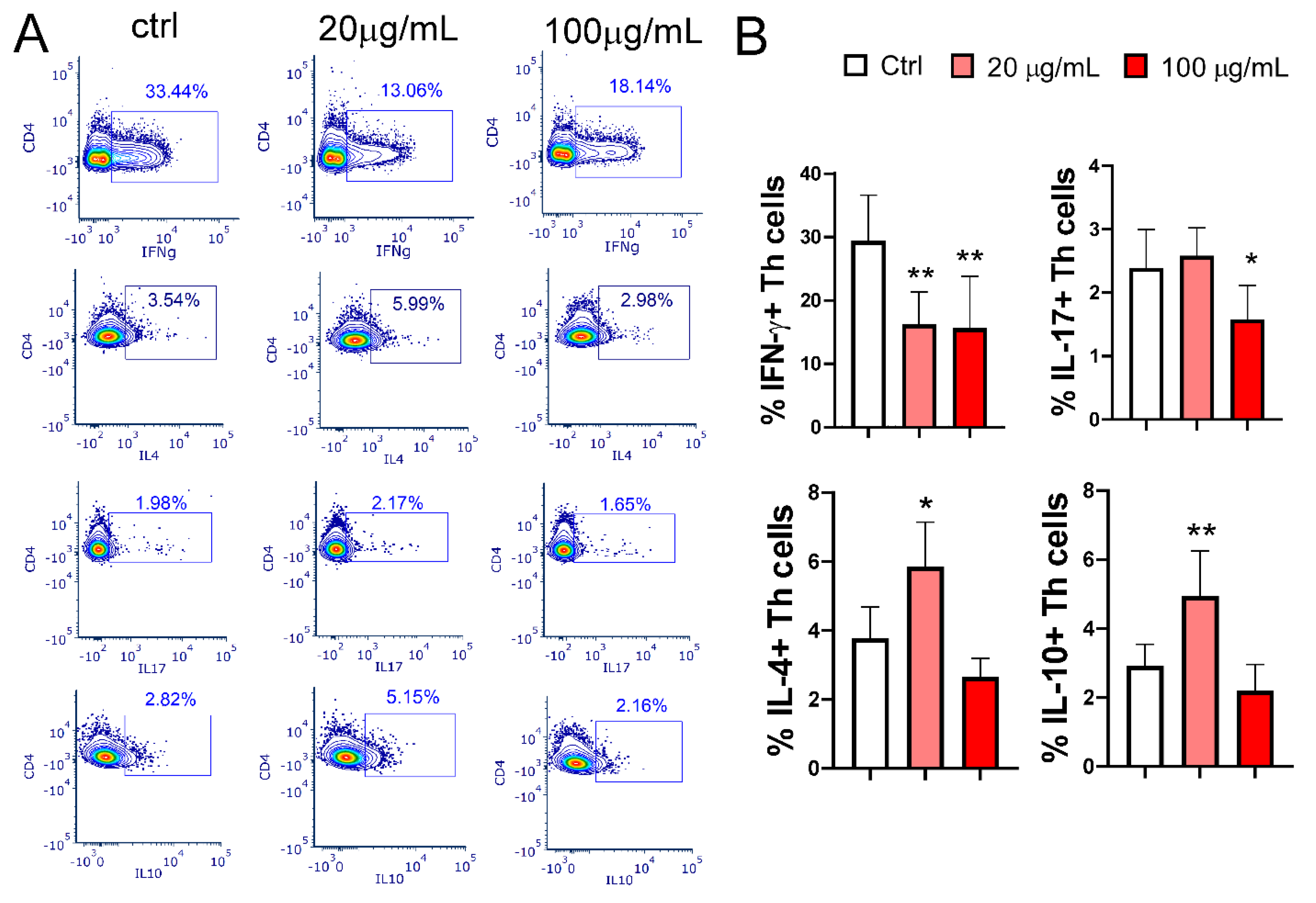

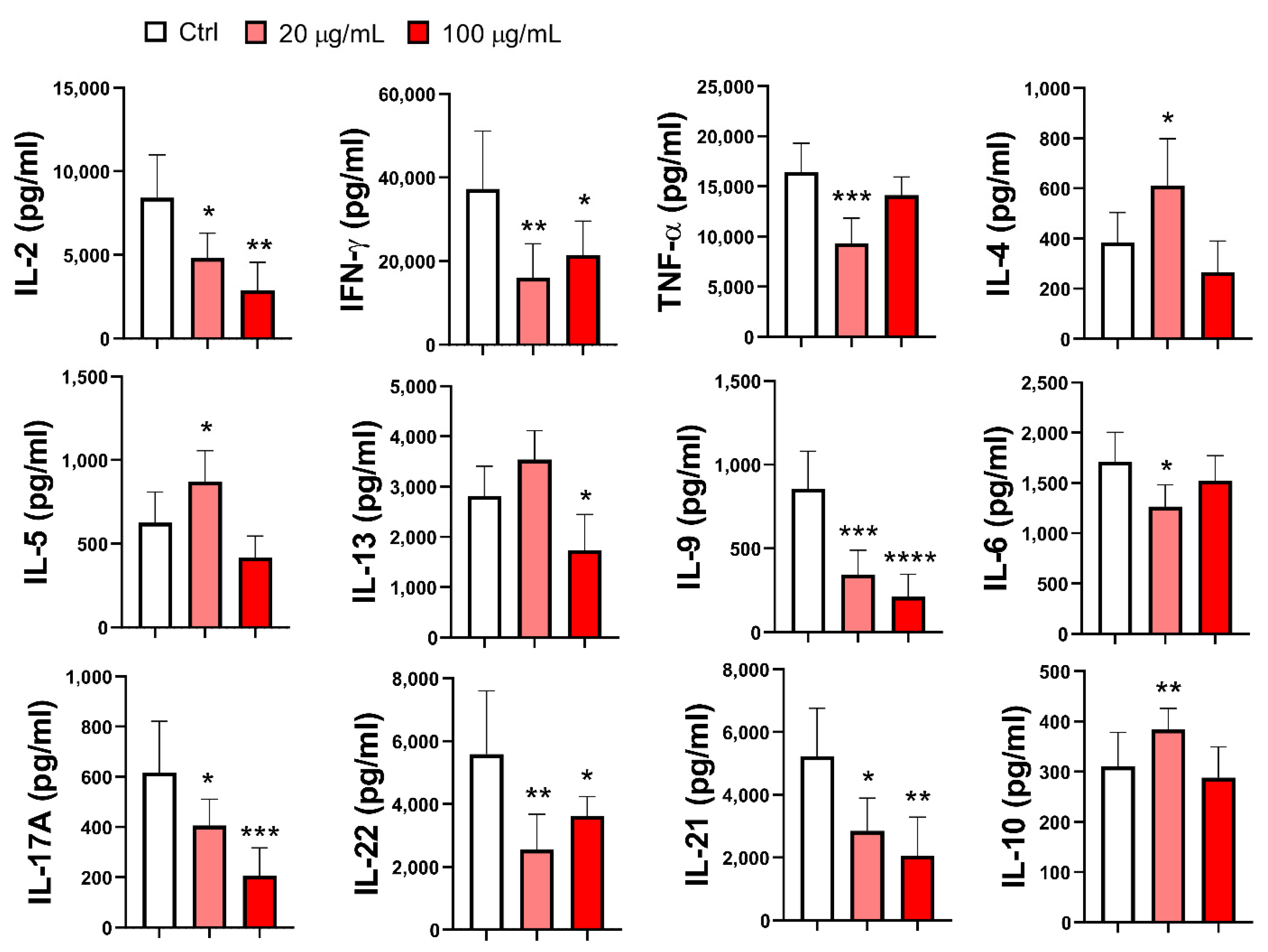

3.6. Effect of EA 575-Treated MoDCs on Th Polarization

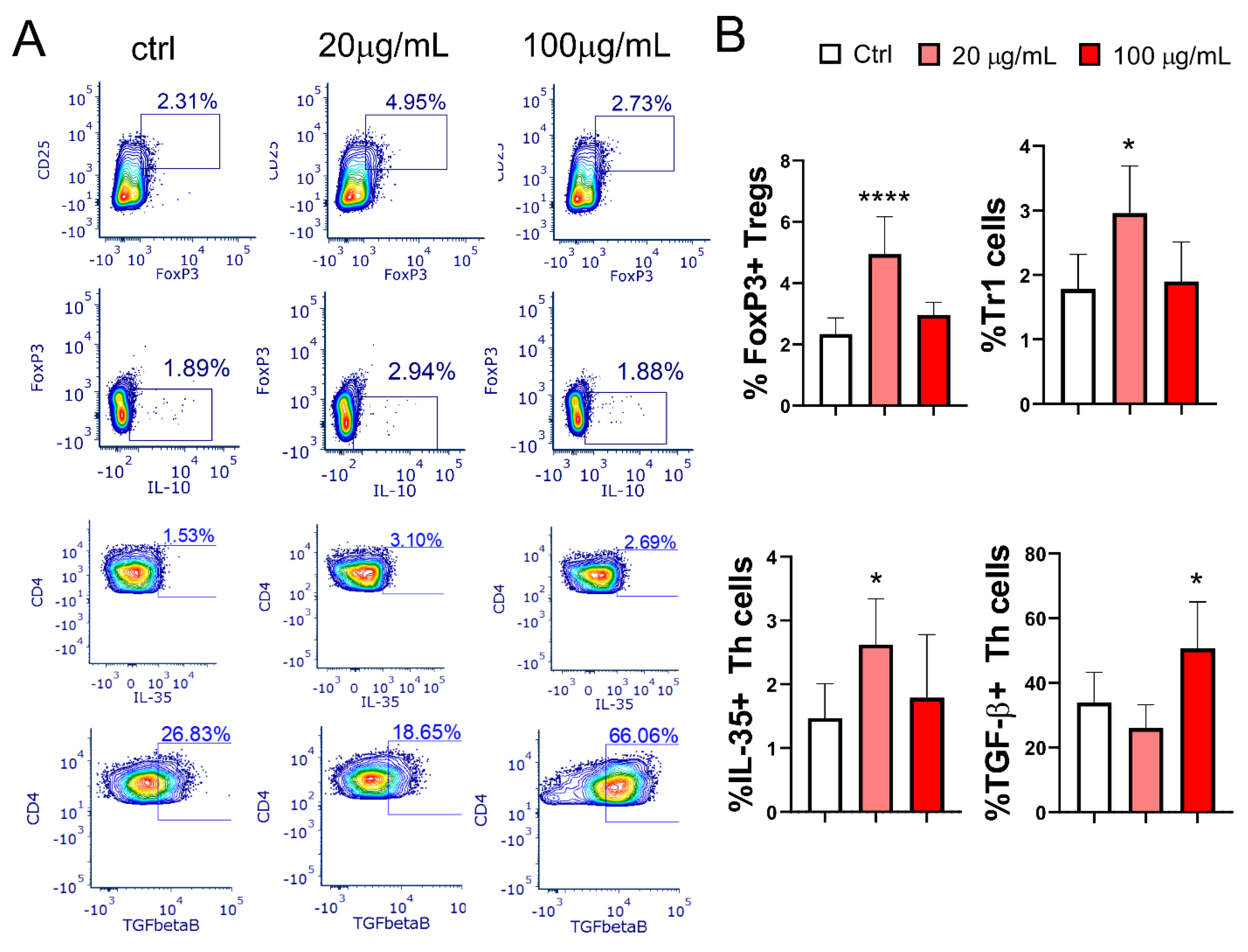

3.7. Effect of EA 575-Treated mMoDCs on the Development of Treg Populations

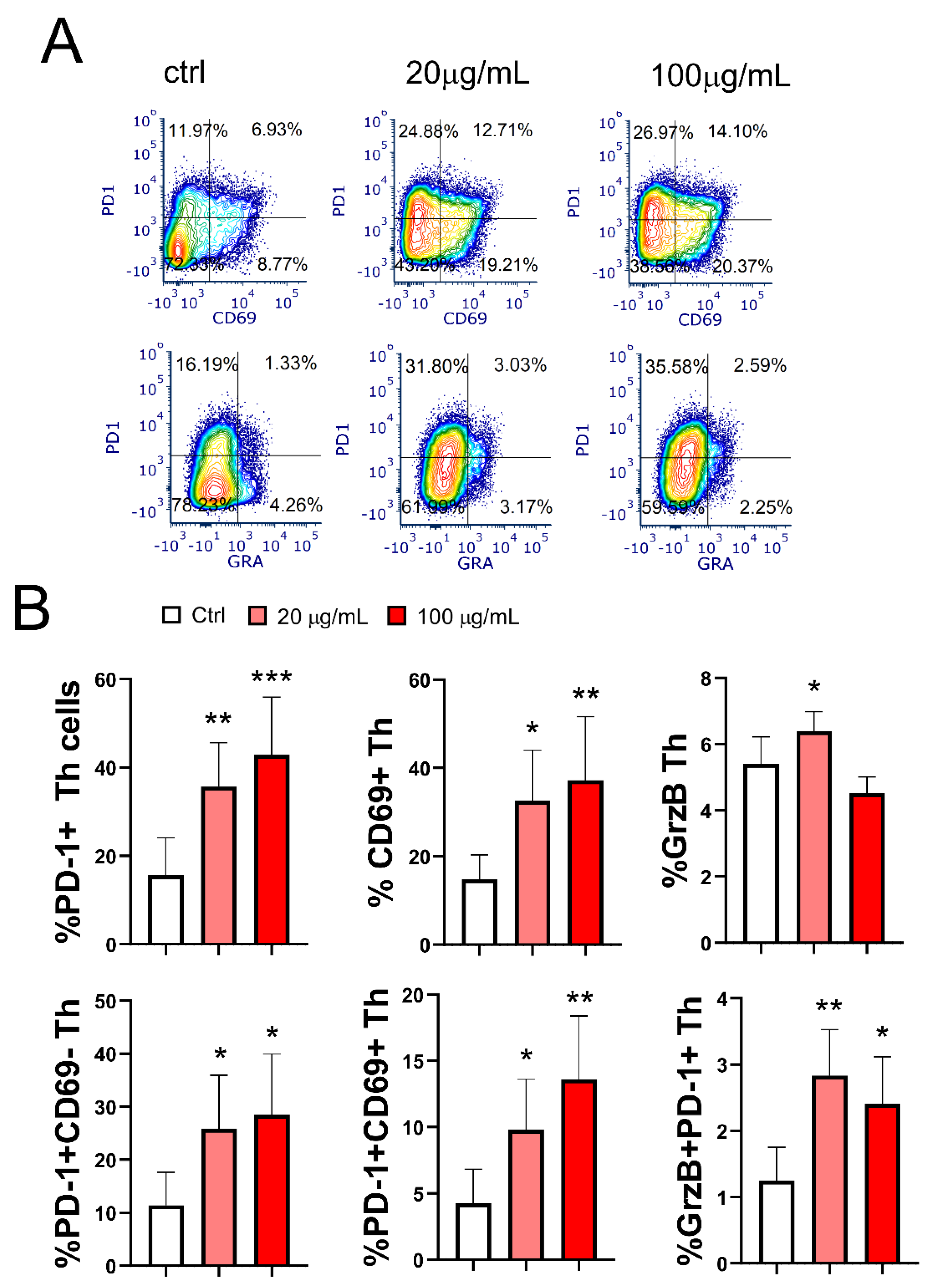

3.8. Effect of EA 575-Treated mMoDCs on the Development of Exhausted PD1+CD4+ Cells and Cytotoxic CD4+ T Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fazio, S.; Pouso, J.; Dolinsky, D.; Fernandez, A.; Hernandez, M.; Clavier, G.; Hecker, M. Tolerance, safety and efficacy of Hedera helix extract in inflammatory bronchial diseases under clinical practice conditions: a prospective, open, multicentre postmarketing study in 9657 patients. Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cwientzek, U.; Ottillinger, B.; Arenberger, P. Acute bronchitis therapy with ivy leaves extracts in a two-arm study. A double-blind, randomised study vs. an other ivy leaves extract. Phytomedicine, 2011, 18, 1105-9. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.; Kehr, M. S.; Giannetti, B. M.; Bulitta, M.; Staiger, C. A randomized, controlled, double-blind, multi-center trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a liquid containing ivy leaves dry extract (EA 575((R))) vs. placebo in the treatment of adults with acute cough. Pharmazie 2016, 71, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, A.; Ludwig, F.; Giannetti, B. M.; Bulitta, M.; Wacker, A. Efficacy of two dosing schemes of a liquid containing ivy leaves dry extract EA 575 versus placebo in the treatment of acute bronchitis in adults. ERJ Open Res 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Rottger-Luer, P.; Staiger, C. A Valuable Option for the Treatment of Respiratory Diseases: Review on the Clinical Evidence of the Ivy Leaves Dry Extract EA 575(R). Planta Med 2015, 81, 968–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifert, G.; Upstone, L.; Watling, C. P.; Vogelberg, C. Ivy leaf dry extract EA 575 for the treatment of acute and chronic cough in pediatric patients: review and expert survey. Curr Med Res Opin 2023, 39, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völp, A.; Schmitz, J.; Bulitta, M.; Raskopf, E.; Acikel, C.; Mosges, R. Ivy leaves extract EA 575 in the treatment of cough during acute respiratory tract infections: meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 20041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauss-Grabo, M.; Atiye, S.; Warnke, A.; Wedemeyer, R. S.; Donath, F.; Blume, H. H. Observational study on the tolerability and safety of film-coated tablets containing ivy extract (Prospan(R) Cough Tablets) in the treatment of colds accompanied by coughing. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 433–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocaoglu, A. B.; Karaman, O.; Erge, D. O.; Erbil, G.; Yilmaz, O.; Kivcak, B.; Bagriyanik, H. A.; Uzuner, N. Effect of Hedera helix on lung histopathology in chronic asthma. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2012, 11, 316–23. [Google Scholar]

- Suleyman, H.; Mshvildadze, V.; Gepdiremen, A.; Elias, R. Acute and chronic antiinflammatory profile of the ivy plant, Hedera helix, in rats. Phytomedicine 2003, 10, 370–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokry, A. A.; El-Shiekh, R. A.; Kamel, G.; Bakr, A. F.; Ramadan, A. Bioactive phenolics fraction of Hedera helix L. (Common Ivy Leaf) standardized extract ameliorates LPS-induced acute lung injury in the mouse model through the inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress. Heliyon, 2022, 8, e09477. [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Michels, J.; Runkel, F.; Gokorsch, S.; Häberlein, H. Ivy leaves dry extract EA 575(R) decreases LPS-induced IL-6 release from murine macrophages. Pharmazie 2016, 71, 158–61. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Michels, J.; Keksel, C.; Häberlein, H.; Franken, S. Anti-inflammatory effects of ivy leaves dry extract: influence on transcriptional activity of NF-kappaB. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S. C. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurer, F.; Häberlein, H.; Franken, S. Ivy Leaf Dry Extract EA 575((R)) Has an Inhibitory Effect on the Signalling Cascade of Adenosine Receptor A(2B). Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Hänsel, R.; Keller, K.; Rimpler, H.; Schneider, G. , Drogen EO. In Berlin: Springer-Verlag: 1993.

- Lutsenko, Y.; Bylka, W.; Matlawska, I.; Darmohray, R. Hedera helix as a medicinal plant. Herba Polonica 2010, 56, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Passos, F. R. S.; Araujo-Filho, H. G.; Monteiro, B. S.; Shanmugam, S.; Araujo, A. A. S.; Almeida, J.; Thangaraj, P.; Junior, L. J. Q.; Quintans, J. S. S. Anti-inflammatory and modulatory effects of steroidal saponins and sapogenins on cytokines: A review of pre-clinical research. Phytomedicine 2022, 96, 153842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Tan, B.; Yin, Y.; Blachier, F.; Tossou, M. C.; Rahu, N. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: What Polyphenols Can Do for Us? Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 7432797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M. A. A.; Rakib, A.; Mandal, M.; Kumar, S.; Singla, B.; Singh, U. P. Polyphenols: Role in Modulating Immune Function and Obesity. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focaccetti, C.; Izzi, V.; Benvenuto, M.; Fazi, S.; Ciuffa, S.; Giganti, M. G.; Potenza, V.; Manzari, V.; Modesti, A.; Bei, R. Polyphenols as Immunomodulatory Compounds in the Tumor Microenvironment: Friends or Foes? Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasso, P.; Gomez-Cadena, A.; Uruena, C.; Donda, A.; Martinez-Usatorre, A.; Barreto, A.; Romero, P.; Fiorentino, S. Prophylactic vs. Therapeutic Treatment With P2Et Polyphenol-Rich Extract Has Opposite Effects on Tumor Growth. Front Oncol, 2018, 8, 356. [CrossRef]

- Rajput, Z. I.; Hu, S. H.; Xiao, C. W.; Arijo, A. G. Adjuvant effects of saponins on animal immune responses. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2007, 8, 153–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, J. T. G.; Da Silva Baldivia, D.; de Castro, D. T. H.; Dos Santos, H. F.; Dos Santos, C. M.; Oliveira, A. S.; Alfredo, T. M.; Vilharva, K. N.; de Picoli Souza, K.; Dos Santos, E. L. The immunoregulatory function of polyphenols: implications in cancer immunity. J Nutr Biochem 2020, 85, 108428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbarth, S. C. Dendritic cell subsets in T cell programming: location dictates function. Nat Rev Immunol 2019, 19, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randolph, G. J.; Inaba, K.; Robbiani, D. F.; Steinman, R. M.; Muller, W. A. Differentiation of phagocytic monocytes into lymph node dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity 1999, 11, 753–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, B.; Lopez-Bravo, M.; Ardavin, C. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells formed at the infection site control the induction of protective T helper 1 responses against Leishmania. Immunity 2007, 26, 519–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, M.; Bigley, V. Human dendritic cell subsets: an update. Immunology. [CrossRef]

- Greunke, C.; Hage-Hülsmann, A.; Sorkalla, T.; Keksel, N.; Häberlein, F.; Häberlein, H. A systematic study on the influence of the main ingredients of an ivy leaves dry extract on the β₂-adrenergic responsiveness of human airway smooth muscle cells. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 31, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierocinski, E.; Holzinger, F.; Chenot, J. F. Ivy leaf (Hedera helix) for acute upper respiratory tract infections: an updated systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2021, 77, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenigün, V. B.; Kocyigit, A.; Kanımdan, E.; Durmus, E.; Koktasoglu, F. Hedera helix (Wall Ivy) leaf ethanol extract shows cytotoxic and apoptotic effects in glioblastoma cells by generating reactive oxygen species. Acta Medica 2023, 54, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. X.; Zhou, J. Y.; Li, Y.; Zou, X.; Wu, J.; Gu, J. F.; Yuan, J. R.; Zhao, B. J.; Feng, L.; Jia, X. B.; Wang, R. P. Hederagenin from the leaves of ivy (Hedera helix L.) induces apoptosis in human LoVo colon cells through the mitochondrial pathway. BMC Complement Altern Med. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. H.; Baek, S.; Shin, D.; Lee, J.; Roh, J. L. Hederagenin Induces Apoptosis in Cisplatin-Resistant Head and Neck Cancer Cells by Inhibiting the Nrf2-ARE Antioxidant Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 5498908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, I.; Mshvildadze, V.; Gepdiremen, A.; Elias, R. Antioxidant activity of saponins isolated from ivy: alpha-hederin, hederasaponin-C, hederacolchiside-E and hederacolchiside-F. Planta Med 2004, 70, 561–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mba Gachou, C.; Laget, M.; Guiraud-Dauriac, H.; De Meo, M.; Elias, R.; Dumenil, G. The protective activity of alpha-hederine against H2O2 genotoxicity in HepG2 cells by alkaline comet assay. Mutat Res 1999, 445, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Cabrerizo, M.; Cardoso, A.; Minutti, C. M.; Pereira da Costa, M.; Reis e Sousa, C. Dendritic Cells Revisited. Annu Rev Immunol 2021, 39, 131–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieseler, R.; Heise, D.; Soruri, A.; Schwartz, P.; Peters, J. H. In-vitro differentiation of mature dendritic cells from human blood monocytes. Dev Immunol 1998, 6, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, M. C.; Quintana, F. J. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Semin Immunopathol 2017, 39, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T. H.; Jin, P.; Ren, J.; Slezak, S.; Marincola, F. M.; Stroncek, D. F. Evaluation of 3 clinical dendritic cell maturation protocols containing lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma. J Immunother 2009, 32, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, K.; Guzzo, C.; Che Mat, N. F.; Ma, W.; Kumar, A. The IL-12 family of cytokines in infection, inflammation and autoimmune disorders. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 2009, 8, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait Wojno, E. D.; Hunter, C. A.; Stumhofer, J. S. The Immunobiology of the Interleukin-12 Family: Room for Discovery. Immunity 2019, 50, 851–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. K.; Kim, J. Properties of immature and mature dendritic cells: phenotype, morphology, phagocytosis, and migration. RSC Adv 2019, 9, 11230–11238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, A.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Deng, R.; Ma, Y. Inhibition of Dectin-1 on Dendritic Cells Prevents Maturation and Prolongs Murine Islet Allograft Survival. J Inflamm Res 2021, 14, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zande, H. J. P.; Nitsche, D.; Schlautmann, L.; Guigas, B.; Burgdorf, S. The Mannose Receptor: From Endocytic Receptor and Biomarker to Regulator of (Meta)Inflammation. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 765034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relloso, M.; Puig-Kroger, A.; Pello, O. M.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, J. L.; de la Rosa, G.; Longo, N.; Navarro, J.; Munoz-Fernandez, M. A.; Sanchez-Mateos, P.; Corbi, A. L. DC-SIGN (CD209) expression is IL-4 dependent and is negatively regulated by IFN, TGF-beta, and anti-inflammatory agents. J Immunol 2002, 168, 2634–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labiod, N.; Luczkowiak, J.; Tapia, M. M.; Lasala, F.; Delgado, R. The role of DC-SIGN as a trans-receptor in infection by MERS-CoV. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1177270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamik, J.; Munson, P. V.; Hartmann, F. J.; Combes, A. J.; Pierre, P.; Krummel, M. F.; Bendall, S. C.; Arguello, R. J.; Butterfield, L. H. Distinct metabolic states guide maturation of inflammatory and tolerogenic dendritic cells. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, C. M.; Holowka, T.; Sun, J.; Blagih, J.; Amiel, E.; DeBerardinis, R. J.; Cross, J. R.; Jung, E.; Thompson, C. B.; Jones, R. G.; Pearce, E. J. Toll-like receptor-induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood 2010, 115, 4742–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzade, A.; Sadeghi, O.; Naghdipour Biregani, A.; Soukhtehzari, S.; Brandt, G. S.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Immunomodulatory Effects of Flavonoids: Possible Induction of T CD4+ Regulatory Cells Through Suppression of mTOR Pathway Signaling Activity. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P.; Khan, F.; Qari, H. A.; Oves, M. Rutin (Bioflavonoid) as Cell Signaling Pathway Modulator: Prospects in Treatment and Chemoprevention. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagarajan, V.; Lee, K. W.; Leong, M. K.; Weng, C. F. Potential natural mTOR inhibitors screened by in silico approach and suppress hepatic stellate cells activation. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2018, 36, 4220–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Sun, Y.; Bai, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, Q.; Kuang, H. Effects of saponins from Chinese herbal medicines on signal transduction pathways in cancer: A review. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1159985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y. C.; Shen, J.; Si, Y.; Liu, X. W.; Zhang, L.; Wen, J.; Zhang, T.; Yu, Q. Q.; Lu, J. F.; Xiang, K.; Liu, Y. Paris saponin VII, a direct activator of AMPK, induces autophagy and exhibits therapeutic potential in non-small-cell lung cancer. Chin J Nat Med 2021, 19, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ji, Q.; Cai, G.; Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q. alpha-hederin induces autophagic cell death in colorectal cancer cells through reactive oxygen species dependent AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway activation. Int J Oncol 2019, 54, 1601–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Shaukat, A.; Zahoor, A.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Umar, T.; Guo, M.; Deng, G. Anti-inflammatory effects of Hederacoside-C on Staphylococcus aureus induced inflammation via TLRs and their downstream signal pathway in vivo and in vitro. Microb Pathog 2019, 137, 103767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, I.; Nalawade, S.; Eagar, T. N.; Forsthuber, T. G. T cell subsets and their signature cytokines in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Cytokine 2015, 74, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, C. E. T hel per cell subsets: diversification of the field. Eur J Immunol 2023, 53, e2250218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J. A.; McKenzie, A. N. J. T(H)2 cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol 2018, 18, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brogdon, J. L.; Xu, Y.; Szabo, S. J.; An, S.; Buxton, F.; Cohen, D.; Huang, Q. Histone deacetylase activities are required for innate immune cell control of Th1 but not Th2 effector cell function. Blood 2007, 109, 1123–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Yang, T.; Ye, Y.; Shan, J.; Yin, Z.; Luo, L. Chlorogenic acid protects mice against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Injury 2010, 41, 746–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, G.; Lee, S.; Hong, J.; Park, B.; Kim, D.; Kim, C. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of 4,5-Dicaffeoylquinic Acid on RAW264.7 Cells and a Rat Model of Inflammation. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E. H.; Kim, J. Y.; Kim, H. G.; Chun, H. K.; Chung, Y. C.; Jeong, H. G. Inhibitory effect of 3-caffeoyl-4-dicaffeoylquinic acid from Salicornia herbacea against phorbol ester-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in macrophages. Chem Biol Interact 2010, 183, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morante-Palacios, O.; Fondelli, F.; Ballestar, E.; Martinez-Caceres, E. M. Tolerogenic Dendritic Cells in Autoimmunity and Inflammatory Diseases. Trends Immunol 2021, 42, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaab, H. O.; Sau, S.; Alzhrani, R.; Tatiparti, K.; Bhise, K.; Kashaw, S. K.; Iyer, A. K. PD-1 and PD-L1 Checkpoint Signaling Inhibition for Cancer Immunotherapy: Mechanism, Combinations, and Clinical Outcome. Front Pharmacol 2017, 8, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravetch, J. V.; Lanier, L. L. Immune inhibitory receptors. Science 2000, 290, 84–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suciu-Foca, N.; Cortesini, R. Central role of ILT3 in the T suppressor cell cascade. Cell Immunol 2007, 248, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenk, M.; Scheler, M.; Koch, S.; Neumann, J.; Takikawa, O.; Hacker, G.; Bieber, T.; von Bubnoff, D. Tryptophan deprivation induces inhibitory receptors ILT3 and ILT4 on dendritic cells favoring the induction of human CD4+CD25+ Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol 2009, 183, 145–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallarino, F.; Grohmann, U.; Hwang, K. W.; Orabona, C.; Vacca, C.; Bianchi, R.; Belladonna, M. L.; Fioretti, M. C.; Alegre, M. L.; Puccetti, P. Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2003, 4, 1206–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevyrev, D.; Tereshchenko, V. Treg Heterogeneity, Function, and Homeostasis. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeborn, R. A.; Strubbe, S.; Roncarolo, M. G. Type 1 regulatory T cell-mediated tolerance in health and disease. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1032575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, C.; Yano, H.; Workman, C. J.; Vignali, D. A. A. Interleukin-35: Structure, Function and Its Impact on Immune-Related Diseases. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2021, 41, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, D. V.; Yano, H.; Chikina, M.; Zhang, Q.; Liao, M.; Liu, C.; Callahan, D. J.; Sun, Z.; Sun, T.; Tabib, T.; Pennathur, A.; Corry, D. B.; Luketich, J. D.; Lafyatis, R.; Chen, W.; Poholek, A. C.; Bruno, T. C.; Workman, C. J.; Vignali, D. A. A. Adaptive plasticity of IL-10(+) and IL-35(+) T(reg) cells cooperatively promotes tumor T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol 2019, 20, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheiri, F.; Rostami-Nejad, M.; Amani, D.; Sadeghi, A.; Moradi, A.; Aghamohammadi, E.; Sahebkar, A.; Zali, M. R. Expression of tolerogenic dendritic cells in the small intestinal tissue of patients with celiac disease. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, W.; Yin, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, T.; Qian, J.; Su, R.; Hong, L.; Lu, H.; Zhang, F.; Xie, H.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, S. Blocking Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells-1-Positive Tumor-Associated Macrophages Induced by Hypoxia Reverses Immunosuppression and Anti-Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Resistance in Liver Cancer. Hepatology 2019, 70, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C. W.; Gold, M. J.; Garcia-Batres, C.; Tai, K.; Elford, A. R.; Himmel, M. E.; Elia, A. J.; Ohashi, P. S. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha limits dendritic cell stimulation of CD8 T cell immunity. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0244366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, Y.; Yang, P.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z.; Xu, L. CD69 is a Promising Immunotherapy and Prognosis Prediction Target in Cancer. Immunotargets Ther 2024, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. Y.; Hayashizaki, K.; Tokoyoda, K.; Takamura, S.; Motohashi, S.; Nakayama, T. Crucial role for CD69 in allergic inflammatory responses: CD69-Myl9 system in the pathogenesis of airway inflammation. Immunol Rev 2017, 278, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, A. H.; Pauken, K. E. The diverse functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat Rev Immunol 2018, 18, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Hu, M.; Chen, Z.; Wei, J.; Du, H. Single-Cell Transcriptome Analysis Reveals RGS1 as a New Marker and Promoting Factor for T-Cell Exhaustion in Multiple Cancers. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 767070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, C. U.; Haining, W. N.; Held, W.; Hogan, P. G.; Kallies, A.; Lugli, E.; Lynn, R. C.; Philip, M.; Rao, A.; Restifo, N. P.; Schietinger, A.; Schumacher, T. N.; Schwartzberg, P. L.; Sharpe, A. H.; Speiser, D. E.; Wherry, E. J.; Youngblood, B. A.; Zehn, D. Defining ‘T cell exhaustion’. Nat Rev Immunol 2019, 19, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miggelbrink, A. M.; Jackson, J. D.; Lorrey, S. J.; Srinivasan, E. S.; Waibl-Polania, J.; Wilkinson, D. S.; Fecci, P. E. CD4 T-Cell Exhaustion: Does It Exist and What Are Its Roles in Cancer? Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27, 5742–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mita, Y.; Kimura, M. Y.; Hayashizaki, K.; Koyama-Nasu, R.; Ito, T.; Motohashi, S.; Okamoto, Y.; Nakayama, T. Crucial role of CD69 in anti-tumor immunity through regulating the exhaustion of tumor-infiltrating T cells. Int Immunol 2018, 30, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenerenti, M.; Saillard, M.; Romero, P.; Jandus, C. The Era of Cytotoxic CD4 T Cells. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 867189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).