Submitted:

05 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

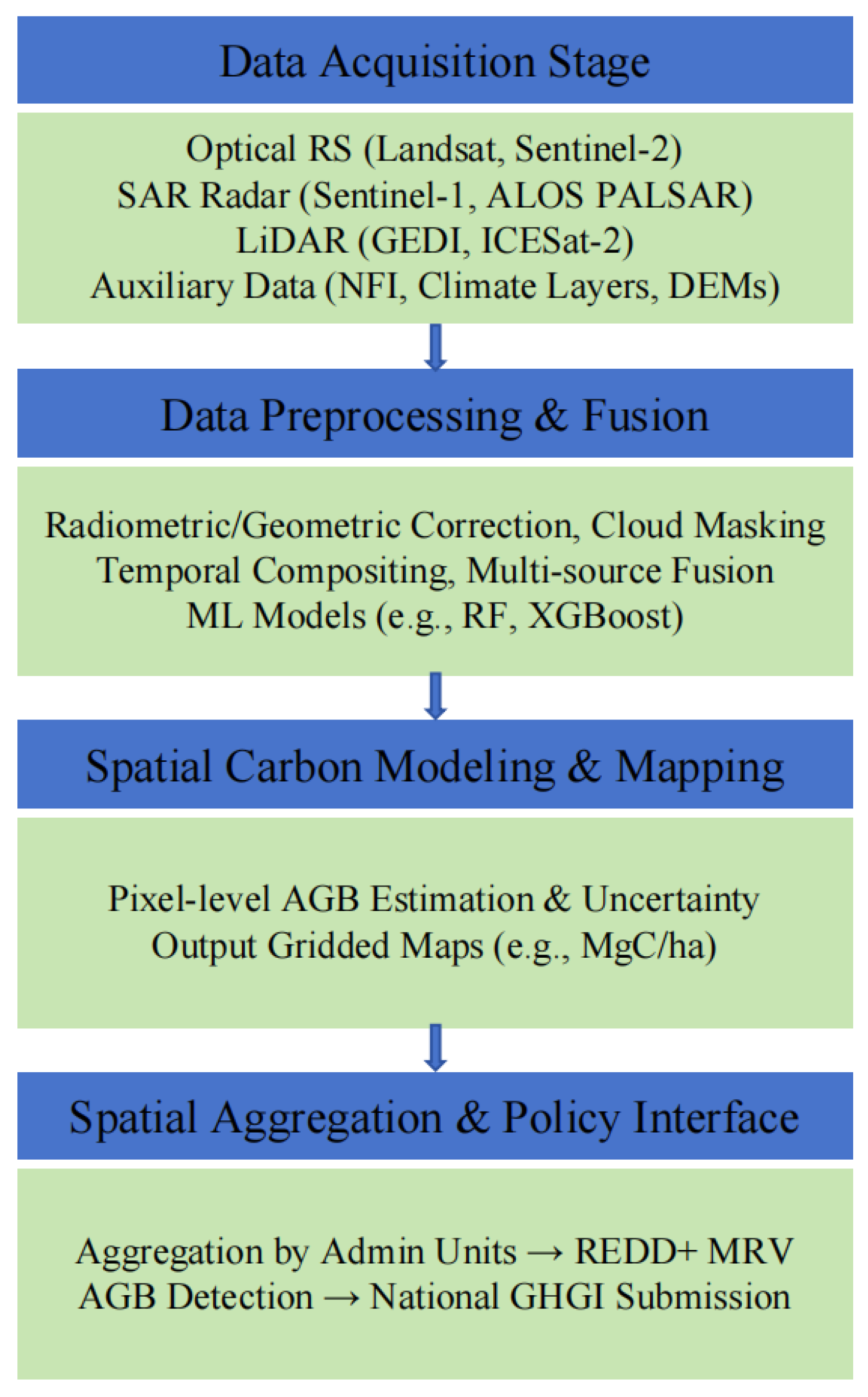

2. Data Foundations for Forest Carbon Monitoring

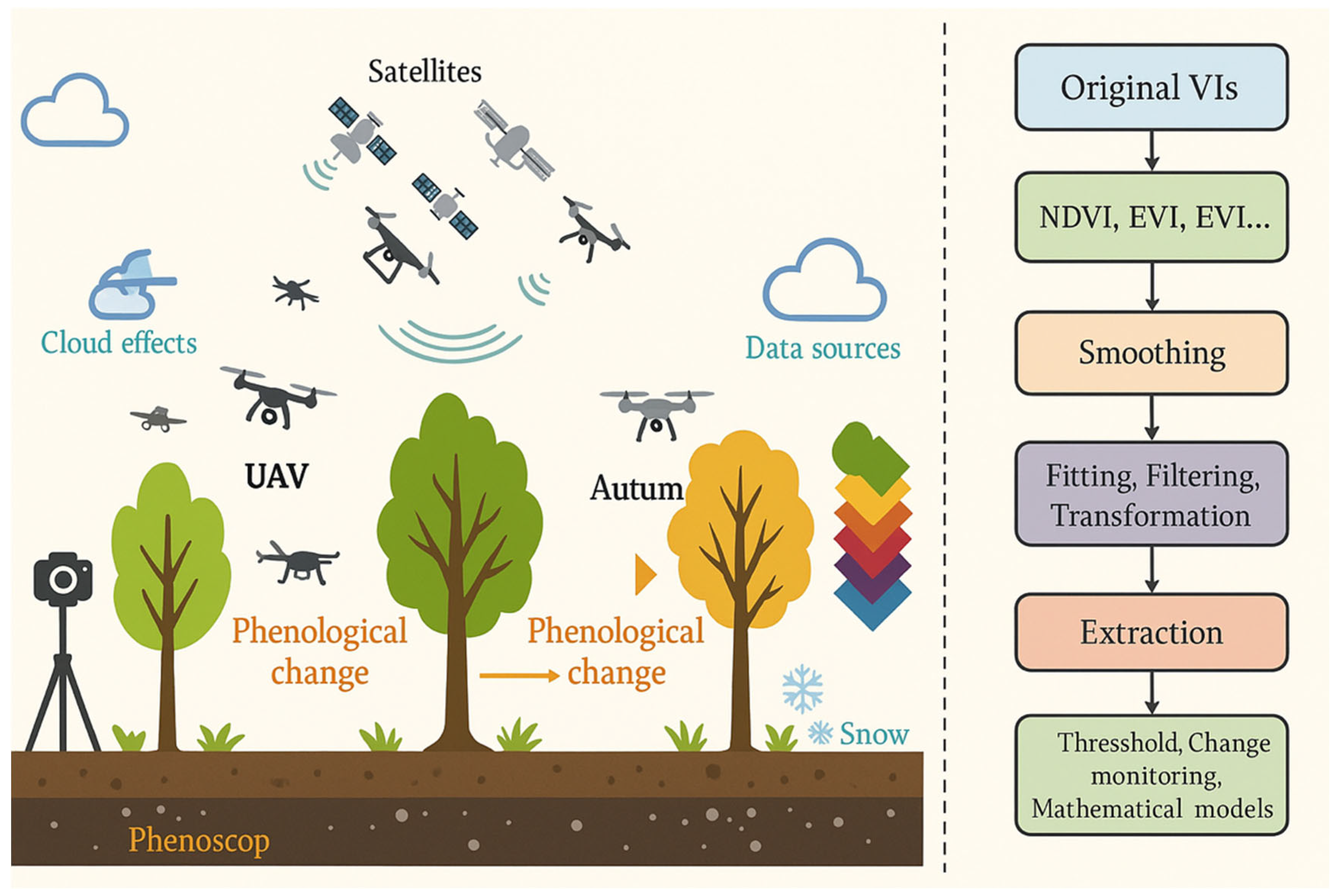

2.1. Optical Satellite Data

2.2. Radar and Microwave Observations

2.3. LiDAR Observations

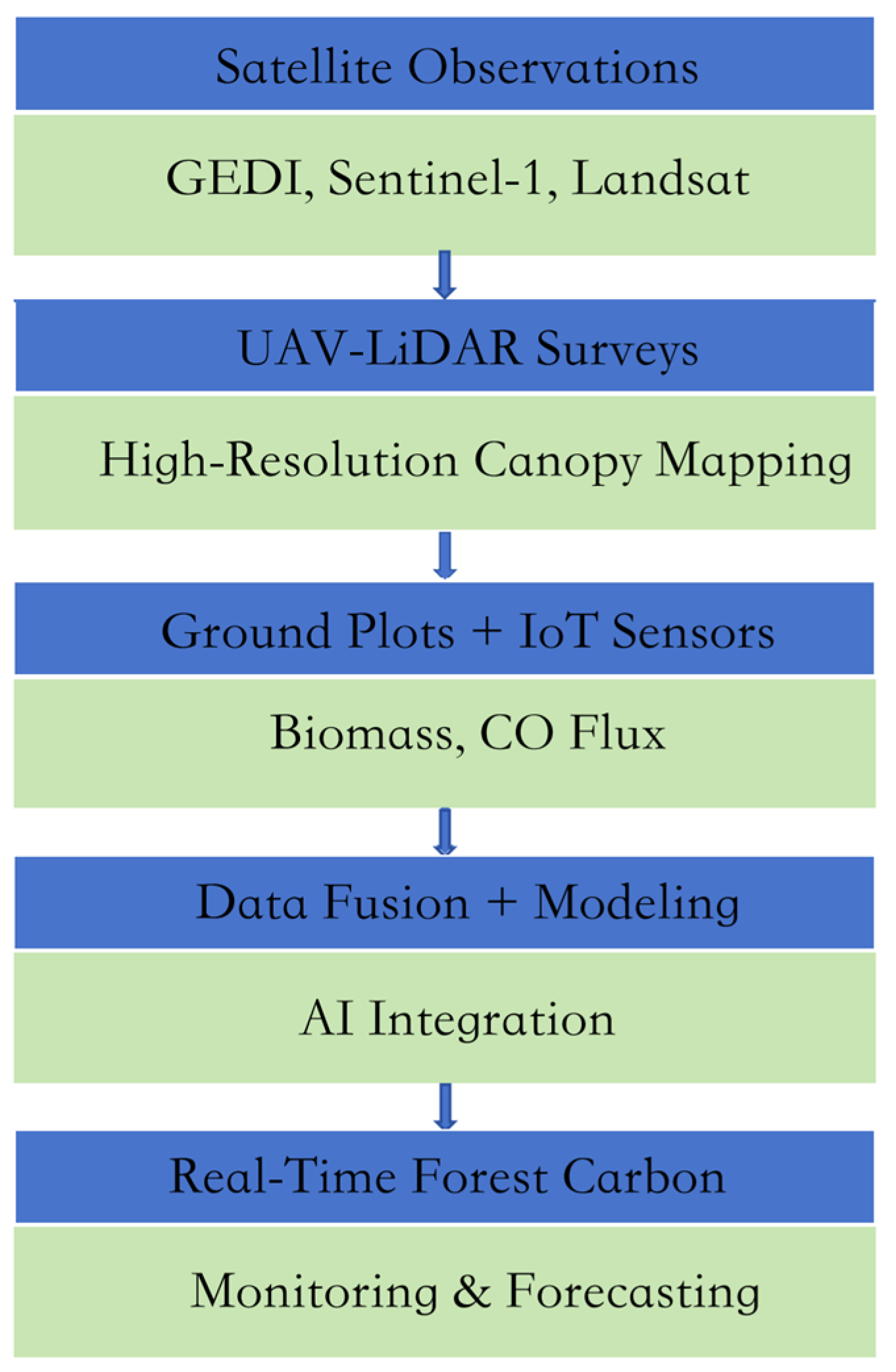

2.4. UAV and Airborne Remote Sensing

2.5. Auxiliary Data: Field Observations and Environmental Covariates

3. Modeling Layer: Data Integration and Biomass Estimation Methods

3.1. Multi-Source Data Fusion and Uncertainty Management for Forest Carbon Monitoring

3.1.1. Multi-Source Data Fusion Techniques

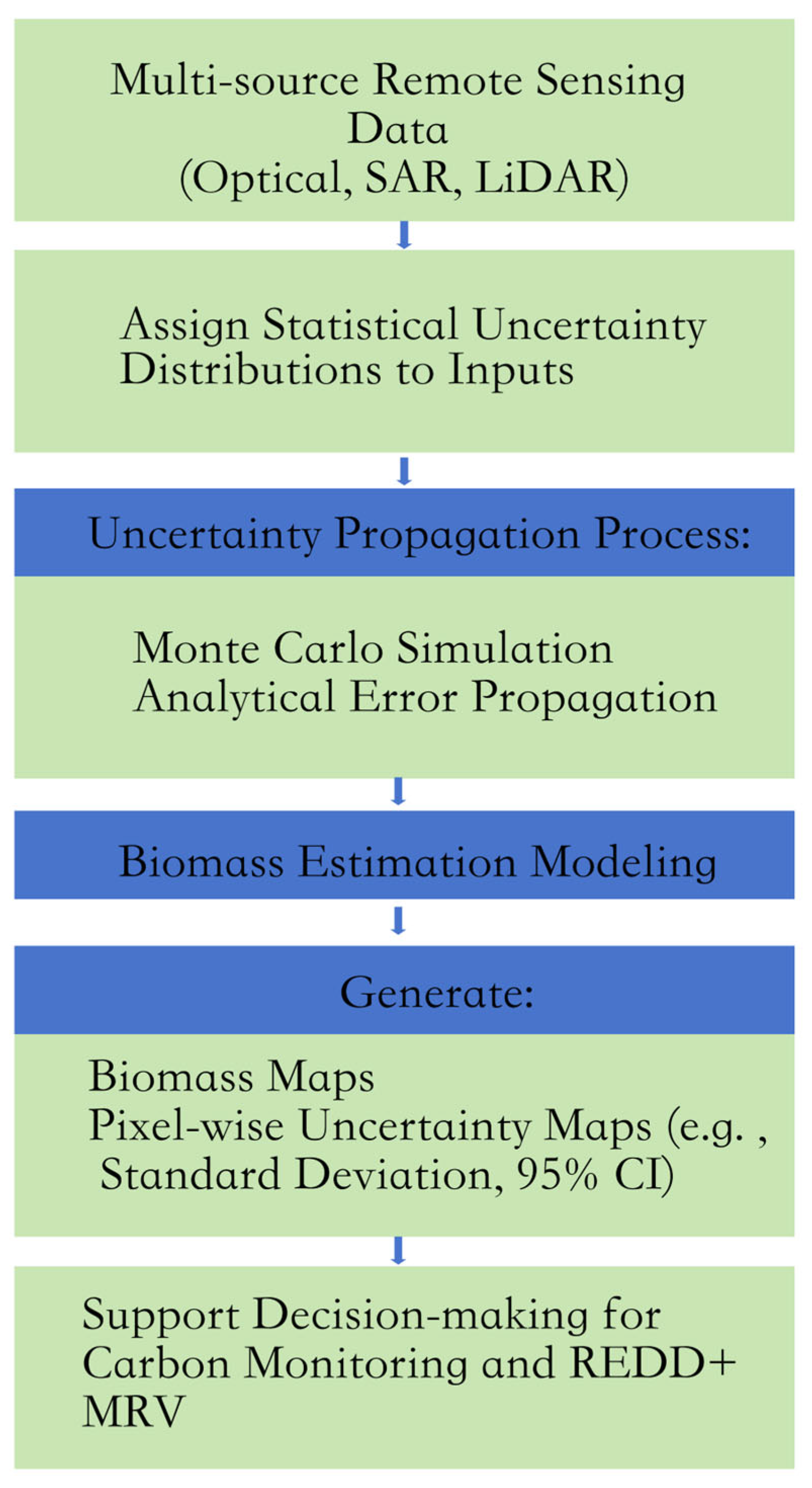

3.1.2. Uncertainty Propagation and Error Analysis in Multi-source Fusion

3.2. Empirical Regression and Allometric Approaches

3.3. Machine Learning Approaches

3.4. Deep Learning Methods

3.5. Process-based Ecological Models

3.6. Belowground and Soil Carbon Estimation

3.7. Comparative Evaluation of Modeling Approaches Across Forest Types

3.8. Meta-Analysis of Biomass Estimation Method Performance

- Deep learning models (mainly CNN-based architectures) achieved the highest average predictive performance (mean R² = 0.85; RMSE = 25 Mg C ha⁻¹), especially in structurally heterogeneous tropical forests.

- Machine learning methods such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting also exhibited strong predictive power (mean R² = 0.78) while maintaining moderate data requirements and reasonable interpretability.

- Empirical regression models, despite their simplicity and high transparency, tended to have lower predictive performance, particularly in high-biomass environments prone to signal saturation.

- Process-based models demonstrated moderate performance (mean R² = 0.66), reflecting their strength in simulating ecosystem processes but also the challenges associated with parameter calibration and spatial heterogeneity.

4. Application Layer: Forest Carbon Monitoring Under Policy Frameworks

4.1. REDD+ Monitoring and MRV Mechanisms

4.2. National and Regional Case Studies

4.2.1. Brazil: Integration of Remote Sensing into REDD+ Accounting

4.2.2. Congo Basin: Overcoming Data Scarcity

4.2.3. Indonesia: Forest Monitoring for REDD+ and Private Commitments

4.3. Carbon Markets and Zero-Deforestation Supply Chains

4.4. Smart Forestry and Digital Carbon Systems

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

5.1. Data Heterogeneity and Lack of Standardization

5.2. Limited Model Generalizability and Field Validation Deficiency

5.3. High-Resolution Data Access: Cost and Temporal Constraints

5.4. Future Directions: Toward Intelligent, Integrated Carbon Monitoring

5.4.1. Cloud Platforms and Automated Monitoring

5.4.2. AI-Augmented Ecological Modeling

5.4.3. Integrated Sky-to-Ground Networks

5.4.4. Monitoring Belowground Carbon: Emerging Opportunities from New Satellite Missions

5.4.5. Uncertainty Management in REDD+ Carbon Credit Issuance

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yoro, K.O.; Daramola, M.O. Chapter 1 - CO2 emission sources, greenhouse gases, and the global warming effect. In Advances in Carbon Capture, Rahimpour, M.R., Farsi, M., Makarem, M.A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: 2020; pp. 3-28.

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedlingstein, P.; O'sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Le Quéré, C.; Li, H.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A. Global carbon budget 2024. Earth System Science Data Discussions 2024, 2024, 1–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, J.; Medvigy, D.; Fueglistaler, S.; Walko, R. Regional dry-season climate changes due to three decades of Amazonian deforestation. Nature Climate Change 2017, 7, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, W.R.L.; Trugman, A.T.; Badgley, G.; Anderson, C.M.; Bartuska, A.; Ciais, P.; Cullenward, D.; Field, C.B.; Freeman, J.; Goetz, S.J.; et al. Climate-driven risks to the climate mitigation potential of forests. Science 2020, 368, eaaz7005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook-Patton, S.C.; Leavitt, S.M.; Gibbs, D.; Harris, N.L.; Lister, K.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.J.; Briggs, R.D.; Chazdon, R.L.; Crowther, T.W.; Ellis, P.W.; et al. Mapping carbon accumulation potential from global natural forest regrowth. Nature 2020, 585, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trugman, A.T.; Quetin, G.R. Leveraging Uncertainty in Terrestrial Ecosystem Carbon Stocks and Fluxes. Earth's Future 2023, 11, e2022EF003322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, A.W.; Houtman, R.M.; Gao, P.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Fettig, C.J.; Hicke, J.A.; Kim, J.B.; Still, C.J.; Young, K.; Riley, K.L. Carbon, climate, and natural disturbance: a review of mechanisms, challenges, and tools for understanding forest carbon stability in an uncertain future. Carbon Balance and Management 2024, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Baral, S.; Burlakoti, D. Afforestation/Reforestation and Avoided Conversion Carbon Projects in the United States. Forests 2025, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, Y.; Meir, P.; Brown, S. Forests, carbon and global climate. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2002, 360, 1567–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossy, T.; Ciais, P.; Renaudineau, S.; Wan, L.; Ygorra, B.; Adam, E.; Barbier, N.; Bauters, M.; Delbart, N.; Frappart, F.; et al. State of the art in remote sensing monitoring of carbon dynamics in African tropical forests. Frontiers in Remote Sensing 2025, Volume 6 - 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musselman, R.C.; and Fox, D.G. A Review of the Role of Temperate Forests in the Global CO2 Balance. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 1991, 41, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, A.A.; Exbrayat, J.-F.; van der Velde, I.R.; Feng, L.; Williams, M. The decadal state of the terrestrial carbon cycle: Global retrievals of terrestrial carbon allocation, pools, and residence times. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, E.; Finley, A.; May, P.; Domke, G.; Andersen, H.-E. ; Gaines, III; Nothdurft, A.; Banerjee, S. Leveraging national forest inventory data to estimate forest carbon density status and trends for small areas, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A.; Saha, S. Machine Learning and Multi-source Remote Sensing in Forest Carbon Stock Estimation: A Review; 2024.

- Xie, X.; Wang, Q.; Dai, L.; Su, D.; Wang, X.; Qi, G.; Ye, Y. Application of China’s National Forest Continuous Inventory Database. Environmental Management 2011, 48, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chen, A.; Peng, C.; Zhao, S.; Ci, L. Changes in Forest Biomass Carbon Storage in China Between 1949 and 1998. Science 2001, 292, 2320–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magerl, A.; Le Noë, J.; Erb, K.-H.; Bhan, M.; Gingrich, S. A comprehensive data-based assessment of forest ecosystem carbon stocks in the US 1907–2012. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14, 125015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navalgund, R.R.; Jayaraman, V.; Roy, P. Remote sensing applications: An overview. current science 2007, 1747–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Z.; Ge, W.; Guo, J.; Liu, J. Satellite remote sensing of vegetation phenology: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2024, 217, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, S.; and Dubayah, R. Advances in remote sensing technology and implications for measuring and monitoring forest carbon stocks and change. Carbon Management 2011, 2, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Peng, C.; Work, T.; Candau, J.-N.; DesRochers, A.; Kneeshaw, D. Application of machine-learning methods in forest ecology: recent progress and future challenges. Environmental Reviews 2018, 26, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, S.; Zhao, F.; Tian, L.; Zhao, Z. Comparison of machine learning algorithms for forest parameter estimations and application for forest quality assessments. Forest Ecology and Management 2019, 434, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Mitchard, E.; Chen, Y.; Chen, M.; Cao, C.; Hu, P.; Xu, C.; Hancock, S. Comparing remote sensing-based forest biomass mapping approaches using new forest inventory plots in contrasting forests in northeastern and southwestern China; 2024.

- Panda, S.S.; Rao, M.N.; Thenkabail, P.S.; Misra, D.; Fitzgerald, J.P. Remote sensing systems—Platforms and sensors: Aerial, satellite, UAV, optical, radar, and LiDAR. In Remote Sensing Handbook, Volume I; CRC Press: 2016; pp. 3-86.

- Teillet, P.M.; Staenz, K.; William, D.J. Effects of spectral, spatial, and radiometric characteristics on remote sensing vegetation indices of forested regions. Remote Sensing of Environment 1997, 61, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Yan, K.; Liu, J.; Pu, J.; Zou, D.; Qi, J.; Mu, X.; Yan, G. Assessment of remote-sensed vegetation indices for estimating forest chlorophyll concentration. Ecological Indicators 2024, 162, 112001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, O.; Shoko, C.; Adelabu, S.; Bangira, T. Remote sensing of aboveground forest biomass: A review. Tropical Ecology 2016, 57, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Mi, W.; and Jiang, J. China’s high-resolution optical remote sensing satellites and their mapping applications. Geo-spatial Information Science 2021, 24, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, M.D.; Prasad, S.; Pacifici, F.; Gamba, P.; Chanussot, J.; Benediktsson, J.A. Challenges and Opportunities of Multimodality and Data Fusion in Remote Sensing. Proceedings of the IEEE 2015, 103, 1585–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMasry, G.; Sun, D.-W. CHAPTER 1 - Principles of Hyperspectral Imaging Technology. In Hyperspectral Imaging for Food Quality Analysis and Control, Sun, D.-W., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2010; pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Priyanka, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Rajat, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Musthafa, M.; Avtar, R.; Singh, G. Forest Biomass Estimation Using S-Band SAR and Lidar Data. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2024 - 2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 7-12 July 2024, 2024; pp. 4495-4498.

- Tian, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, M. Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation Using Multisource Remote Sensing Data and Deep Learning Algorithms: A Case Study over Hangzhou Area in China. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioucas-Dias, J.M.; Plaza, A.; Camps-Valls, G.; Scheunders, P.; Nasrabadi, N.; Chanussot, J. Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Data Analysis and Future Challenges. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2013, 1, 6–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenkabail, P.S.; Lyon, J.G.; Huete, A. Advances in hyperspectral remote sensing of vegetation and agricultural crops. In Fundamentals, sensor systems, spectral libraries, and data mining for vegetation; CRC press: 2018; pp. 3-37.

- Xu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Luo, M.; Mai, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Progress and Limitations in Forest Carbon Stock Estimation Using Remote Sensing Technologies: A Comprehensive Review. Forests 2025, 16, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiney, S.; Rg, G. Estimation of Above Ground Biomass Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms: A Review. 2024; pp. 181-196.

- Li, C.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Dai, Q. Comparative Analysis of Seasonal Landsat 8 Images for Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation in a Subtropical Forest. Forests 2020, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verly, O.M.; Vieira Leite, R.; da Silva Tavares-Junior, I.; José Silva Soares da Rocha, S.; Garcia Leite, H.; Marinaldo Gleriani, J.; Paula Miranda Xavier Rufino, M.; de Fatima Silva, V.; Moreira Miquelino Eleto Torres, C.; Plata-Rueda, A.; et al. Atlantic forest woody carbon stock estimation for different successional stages using Sentinel-2 data. Ecological Indicators 2023, 146, 109870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Jeganathan, C.; Sharma, L.K.; Nathawat, M.S. A review of radar remote sensing for biomass estimation. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2015, 12, 1779–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treuhaft, R.N.; Law, B.E.; Asner, G.P. Forest Attributes from Radar Interferometric Structure and Its Fusion with Optical Remote Sensing. BioScience 2004, 54, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, A.; T., L.T.; S., G.; E., N.; A., L.; E., M.; C., H.C.; C., H.H.; A., K.J.; and Shin, R.T. Retrieval of forest biomass from SAR data. International Journal of Remote Sensing 1994, 15, 2777–2796. [CrossRef]

- Shiney, S.A.; Geetha, R. Estimation of Above Ground Biomass Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms: A Review. In Proceedings of the Advances in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Big Data Processing, Cham, 2025//; 2025; pp. 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Ometto, J.P.; Gorgens, E.B.; de Souza Pereira, F.R.; Sato, L.; de Assis, M.L.R.; Cantinho, R.; Longo, M.; Jacon, A.D.; Keller, M. A biomass map of the Brazilian Amazon from multisource remote sensing. Sci Data 2023, 10, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, Q.; Shen, R.; Xu, W.; Qin, Z.; Lin, S.; Ha, S.; Kong, D.; Yuan, W. Long-term reconstructed vegetation index dataset in China from fused MODIS and Landsat data. Scientific Data 2025, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Anees, S.A.; Huang, Q.; Qin, X.; Qin, Z.; Fan, J.; Han, G.; Zhang, L.; Shafri, H.Z.M. Improving Forest Above-Ground Biomass Estimation by Integrating Individual Machine Learning Models. Forests 2024, 15, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, G.; Wu, Q.; Ruan, J.; Li, D.; Lu, D. Mapping Forest Carbon Stock Distribution in a Subtropical Region with the Integration of Airborne Lidar and Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Gao, S.; Gao, H.; Sun, L.; Yan, G. Multi-Decision Vector Fusion Model for Enhanced Mapping of Aboveground Biomass in Subtropical Forests Integrating Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and Airborne LiDAR Data. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Su, Y.; Hu, T.; Jin, S.; Liu, X.; Niu, C.; Liu, Z.; Kelly, M.; Wei, J.; Guo, Q. Allometry-based estimation of forest aboveground biomass combining LiDAR canopy height attributes and optical spectral indexes. Forest Ecosystems 2022, 9, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Tan, Y.; Gul, A.A.; Abbas, S.; Wang, J. Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation and Inventory: Evaluating Remote Sensing-Based Approaches. Forests 2024, 15, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khati, U.; Lavalle, M.; Shiroma, G.H.X.; Meyer, V.; Chapman, B. Assessment of Forest Biomass Estimation from Dry and Wet SAR Acquisitions Collected during the 2019 UAVSAR AM-PM Campaign in Southeastern United States. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsah, A.A.; Nazeer, M.; Wong, M.S. LIDAR-Based Forest Biomass Remote Sensing: A Review of Metrics, Methods, and Assessment Criteria for the Selection of Allometric Equations. Forests 2023, 14, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, G.; Lu, D.; Chen, E.; Wei, X. Stratification-Based Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation in a Subtropical Region Using Airborne Lidar Data. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ren, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Xi, Y. Estimation of Forest Above-Ground Biomass by Geographically Weighted Regression and Machine Learning with Sentinel Imagery. Forests 2018, 9, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Nie, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, G.; Fan, W. Improving the Potential of Coniferous Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation by Integrating C- and L-Band SAR Data with Feature Selection and Non-Parametric Model. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Khati, U. Forest Aboveground Biomass and Forest Height Estimation Over a Sub-tropical Forest Using Machine Learning Algorithm and Synthetic Aperture Radar Data. Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing 2024, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillett, S.C.; Graham, M.E.; Montague, J.P.; Antoine, M.E.; Koch, G.W. Ground-based calibration for remote sensing of biomass in the tallest forests. Forest Ecology and Management 2024, 561, 121879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämäräinen, M.; Tuovinen, J.P.; Kulmala, M.; Mammarella, I.; Aalto, J.; Vekuri, H.; Lohila, A.; Lintunen, A. Spatiotemporal lagging of predictors improves machine learning estimates of atmosphere–forest CO2 exchange. Biogeosciences 2023, 20, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netsianda, A.; Mhangara, P. Aboveground biomass estimation in a grassland ecosystem using Sentinel-2 satellite imagery and machine learning algorithms. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2025, 197, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.; Saha, S. Machine Learning and Multi-source Remote Sensing in Forest Carbon Stock Estimation: A Review. 2024; arXiv:2411.17624 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schratz, P.; Muenchow, J.; Iturritxa, E.; Richter, J.; Brenning, A. Performance evaluation and hyperparameter tuning of statistical and machine-learning models using spatial data. 2018; arXiv:1803.11266 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sivasankar, T.; Lone, J.; Sarma, K.K.; Qadir, A.; N, R. Estimation of Above Ground Biomass Using Support Vector Machines and ALOS/PALSAR data. VIETNAM JOURNAL OF EARTH SCIENCES 2019, 41, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yao, F.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H. Estimating Forest Aboveground Biomass Using a Combination of Geographical Random Forest and Empirical Bayesian Kriging Models. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Du, H.; Han, N.; Li, X.; Zhu, D.e.; Mao, F.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, J.; Liu, H.; Huang, Z.; et al. Application of Convolutional Neural Network on Lei Bamboo Above-Ground-Biomass (AGB) Estimation Using Worldview-2. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehmcke, S.; Li, L.; Revenga, J.C.; Nord-Larsen, T.; Trepekli, K.; Gieseke, F.; Igel, C. Deep learning based 3D point cloud regression for estimating forest biomass. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th international conference on advances in geographic information systems, 2022; pp. 1-4.

- Wu, C.; Chen, K.; E, C.; You, X.; He, D.; Hu, L.; Liu, B.; Wang, R.; Shi, Y.; Li, C.; et al. Improved CASA model based on satellite remote sensing data: simulating net primary productivity of Qinghai Lake basin alpine grassland. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 6919–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Watanabe, M.; Ouyang, Z. Simulation of water and carbon fluxes using BIOME-BGC model over crops in China. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2005, 131, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Pang, Y.; Kong, D. Integrating remote sensing and 3-PG model to simulate the biomass and carbon stock of Larix olgensis plantation. Forest Ecosystems 2024, 11, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; He, H.; Peng, S.; Ren, X.; Zhang, L.; Gu, F.; Zhu, G.; Peng, C.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; et al. A Process-Based Model Integrating Remote Sensing Data for Evaluating Ecosystem Services. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 2021, 13, e2020MS002451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K C, A.; Bhattarai, S.; Pandey, P. A Comparison of Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 spectral indices for estimating aboveground forest carbon in a community forest. Forestry Journal of Institute of Forestry Nepal 2023, 01, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.M.; Huo, X.; Hoar, T.J.; Dashti, H.; Smith, W.K.; MacBean, N.; Anderson, J.L.; Roby, M.; Moore, D.J.P. Assimilation of Global Satellite Leaf Area Estimates Reduces Modeled Global Carbon Uptake and Energy Loss by Terrestrial Ecosystems. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2022, 127, e2022JG006830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.; Herold, M.; Jonckheere, I.G.C.; Espejo, A.B.; Green, C.; Wilson, S. Capacity Development for Use of Remote Sensing for REDD+ MRV Using Online and Offline Activities: Impacts and Lessons Learned. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, R.; Fan, W. Estimation of Forest Parameters in Boreal Artificial Coniferous Forests Using Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2A. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutting, B.J.; Atzberger, C.; Gholizadeh, A.; Robinson, D.A.; Mendoza-Ulloa, J.; Marti-Cardona, B. Remote Quantification of Soil Organic Carbon: Role of Topography in the Intra-Field Distribution. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, Z.; Zubair, M.; Zha, Y.; Mehmood, M.S.; Rehman, A.; Fahd, S.; Nadeem, A.A. Predictive modeling of regional carbon storage dynamics in response to land use/land cover changes: An InVEST-based analysis. Ecological Informatics 2024, 82, 102701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Duan, X.; Mao, M.; Hu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Qiu, X.; Rao, X.; et al. Assessing the impact of land use and changes in land cover related to carbon storage by linking trajectory analysis and InVEST models in the Nandu River Basin on Hainan Island in China. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, Volume 10 - 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadoux, A.M.J.-C.; Heuvelink, G.B.M. Uncertainty of spatial averages and totals of natural resource maps. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2023, 14, 1320–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Shi, L.; Lin, L.; Li, S.; Deng, X.; Li, L.; Bian, J.; Lian, X. A novel hybrid modelling framework for GPP estimation: Integrating a multispectral surface reflectance based Vcmax25 simulator into the process-based model. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 921, 171182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avitabile, V.; Herold, M.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Lewis, S.L.; Phillips, O.L.; et al. An integrated pan-tropical biomass map using multiple reference datasets. Global Change Biology 2016, 22, 1406–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargita, Y.; Günter, S.; Köthke, M. Brazil submitted the first REDD+ reference level to the UNFCCC—Implications regarding climate effectiveness and cost-efficiency. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A.; Thau, D.; Stehman, S.V.; Goetz, S.J.; Loveland, T.R.; et al. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science 2013, 342, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, A.; Laing, T. The politics and performativity of REDD+ reference levels: Examining the Guyana-Norway agreement and its implications for ‘offsetting’ towards ‘net zero’. Environmental Science & Policy 2022, 132, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokstad, E. In controversial move, Brazil may outsource Amazon deforestation monitoring. Science Magazine 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubayah, R.; Armston, J.; Kellner, J.; Duncanson, L.; Healey, S.; Patterson, P.; Hancock, S.; Tang, H.; Bruening, J.; Hofton, M. GEDI L4A Footprint Level Aboveground Biomass Density, Version 2.1. ORNL DAAC, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, USA. 2022.

- Halme, E.; Pellikka, P.; Mõttus, M. Utility of hyperspectral compared to multispectral remote sensing data in estimating forest biomass and structure variables in Finnish boreal forest. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2019, 83, 101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Chen, D.; Li, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Zhang, N.; Fan, J.; Jiang, D. Research on Estimating and Evaluating Subtropical Forest Carbon Stocks by Combining Multi-Payload High-Resolution Satellite Data. Forests 2023, 14, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Norwegian Ministry of, C. ; Environment. High-Resolution Satellite Data Opens for the Tropics. Press Release, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cappello, C.; Pratihast, A.K.; Pérez Ojeda del Arco, A.; Reiche, J.; De Sy, V.; Herold, M.; Vivanco Vicencio, R.E.; Castillo Soto, D. Alert-Driven Community-Based Forest Monitoring: A Case of the Peruvian Amazon. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wang, H.; Xu, W.; Luan, Z.; Xu, X. LiDAR Applications to Estimate Forest Biomass at Individual Tree Scale: Opportunities, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Forests 2021, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonweban, J.; Programme, U.-R. The UN-REDD Programme Approach to National Forest Monitoring and Measurement, Reporting and Verification (MRV); United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (UN-REDD): 2021.

- Ramachandran, N.; Saatchi, S.; Tebaldini, S.; d’Alessandro, M.M.; Dikshit, O. Mapping tropical forest aboveground biomass using airborne SAR tomography. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 6233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Veiga, P.; Quegan, S.; Carreiras, J.; Persson, H.J.; Fransson, J.E.S.; Hoscilo, A.; Ziółkowski, D.; Stereńczak, K.; Lohberger, S.; Stängel, M.; et al. Forest biomass retrieval approaches from earth observation in different biomes. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2019, 77, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Huang, H.; Boschetti, L.; Giglio, L.; Yan, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Roy, D. Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 burned area mapping -A combined sensor multi-temporal change detection approach. Remote Sensing of Environment 2019, 231, 111254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, E.; Barrera, J.A.; Dube, F.; Casco, F.; Hernández, A.J.; Zagal, E. Monitoring Approach for Tropical Coniferous Forest Degradation Using Remote Sensing and Field Data. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Yang, Y.; Li, R.; Zheng, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Integrating Remotely Sensed Leaf Area Index with Biome-BGC to Quantify the Impact of Land Use/Land Cover Change on Water Retention in Beijing. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Jing, L.; R., S.A.; Di, Y.; Tianyue, M.; YiTing, S.; and Shao, J. Evaluation of machine learning methods and multi-source remote sensing data combinations to construct forest above-ground biomass models. International Journal of Digital Earth 2023, 16, 4471–4491. [CrossRef]

- Strassburg, B.B.N.; Iribarrem, A.; Beyer, H.L.; Cordeiro, C.L.; Crouzeilles, R.; Jakovac, C.C.; Braga Junqueira, A.; Lacerda, E.; Latawiec, A.E.; Balmford, A.; et al. Global priority areas for ecosystem restoration. Nature 2020, 586, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate, C. Chapter 7: Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Uses (AFOLU). In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Piao, S.; Knapp, A.K.; Wang, X.; Peng, S.; Yuan, W.; Running, S.; Mao, J.; Shi, X.; Ciais, P.; et al. Decoupling of greenness and gross primary productivity as aridity decreases. Remote Sensing of Environment 2022, 279, 113120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | This Review | Xu et al. – Forests |

|---|---|---|

| Time Span and Focus | 2020–2025; carbon neutrality-focused integration | 1999–2024; technology-oriented historical scope |

| Remote Sensing Data Scope | Multi-source fusion (optical, SAR, LiDAR) with GIS modeling | Segmented analysis by sensor type with technical emphasis |

| Modeling Perspective | Practical use of ML/DL in scalable carbon estimation workflows | Conceptual classification of empirical and process-based models |

| Policy Integration | Strong alignment with REDD+, carbon markets, and NDC tracking | Technical depth but minimal linkage to climate policy mechanisms |

| Case Study Inclusion | Detailed policy-technical cases (e.g., Brazil, Congo Basin) | Lacks regionally grounded implementation examples |

| Strategic Outlook | Proposes an integrated RS-GIS-AI-policy monitoring framework | Emphasis on modeling uncertainty and methodological innovation |

| Distinctive Contribution | Practice-oriented synthesis with emphasis on operational feasibility and interdisciplinary integration | Methodologically detailed but policy-neutral, serving primarily technical audiences |

| Sensor / Mission | Type | Resolution | Revisit | Key Forest Carbon Uses |

| Landsat-8/9 (NASA/USGS) | Optical (VIS–SWIR) |

30 m | 16 days | Long-term forest cover change; biomass via spectral indices (calibrated with plots)[18]. |

| Sentinel-2 (ESA) | Optical (VIS–SWIR) |

10 m (20 m SWIR) | 5 days (2-satellite constellation) | High-resolution mapping of canopy greenness, leaf area, and forest type; inputs to biomass models, especially in regrowth and mosaic landscapes[19]. |

| MODIS (Terra/Aqua) | Optical (VIS–TIR) |

250–500 m (1 km TIR) | 1–2 days | Regional to global monitoring of vegetation activity (NDVI/EVI, FPAR); NPP estimation for carbon flux modeling[43]. |

| Planet Scope (Planet Labs) | Optical (VIS–NIR) |

3–5 m | Daily (constellation) | Detection of fine-scale changes (small clearings, degradation); verification of project-level carbon actions (e.g., tree planting survival). |

| Sentinel-1 (ESA) | SAR (C-band, VV/VH) |

10 m | 6–12 days | All-weather forest cover monitoring; near-real-time deforestation alerts; detecting flooding and damage under clouds. Limited biomass sensitivity in dense forests[25]. |

| ALOS-2 PALSAR-2 (JAXA) | SAR (L-band, HH/HV) |

25 m (10 m in spotlight) | ~42 days (global mode) | Mapping forest/non-forest extent and structure in tropics [27]; AGB estimation in low to mid biomass stands (e.g., woodland, secondary forest). |

| BIOMASS (ESA, 2024+) | SAR (P-band) |

~50–100 m | 16 days (planned) | Dedicated biomass mapping mission for high-biomass tropical and boreal forests; will provide first P-band tomographic data to estimate AGB up to >300 Mg ha−1 [25]. |

| GEDI Lidar (NASA, ISS) | LiDAR (1064 nm) |

~25 m footprint (60 m spacing) | ~2–4 years mission (sampling) | ~12 million shots per year sampling Earth’s forests; provides canopy height and structure used to calibrate biomass models and create 1-km gridded AGB products[29,30]. |

| ICESat-2 (NASA) | LiDAR (532 nm photon-counting) | ~17 m footprint (0.7 km track spacing) | 91-day exact repeat (sampling) | Global photon-counting LiDAR data used for canopy height retrievals (especially in high latitudes); complements GEDI by covering >51°N/S and open forests. |

| SMOS/SMAP (ESA/NASA) | Passive microwave (L-band) |

~40 km / 9 km | 2–3 days | Vegetation Optical Depth (VOD) as proxy for biomass and water content; tracking large-scale carbon changes (e.g., drought impacts) in combination with models [22,23]. |

| TanDEM-X (DLR) | SAR Interferometry (X-band) | ~12 m (height grid) | N/A (2010–2015 data) | Global digital elevation model from InSAR; used to derive forest canopy height (with ground DEM) and estimate biomass when calibrated[26]. |

| VIIRS (NASA/NOAA) | Thermal & Optical | 375 m (optical) 750 m (thermal) | Daily (polar orbit) | Active fire detection and burn scar mapping for estimating fire emissions; night-time lights can indicate human activity near forests (indirect driver data). |

| Source | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Optical sensor radiometry | Calibration errors, atmospheric contamination | Biases in vegetation indices |

| SAR saturation | Loss of sensitivity in high biomass zones | Underestimated AGB |

| LiDAR sampling gaps | Sparse coverage, geolocation drift | Local errors in canopy structure |

| Temporal misalignment | Seasonality, disturbance mismatches | Phenology artifacts |

| Model structure assumptions | Over-simplified relationships | Systematic bias in biomass predictions |

| Modeling Approach | Suitable Forest Types | Typical Accuracy (R²) | Prediction Error (RMSE, Mg C/ha) | Data Requirements | Interpretability | Scalability | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Regression | Temperate forests, open forests | 0.50–0.70 | 30–60 | Low | Very High | High | Simple to implement, transparent results | Signal saturation in high-biomass forests; limited generalizability |

| Machine Learning (RF) | Tropical, temperate, and boreal forests | 0.65–0.85 | 20–45 | Medium–High | Moderate | Very High | Robust to noise; integrates multi-source data effectively | Requires large training datasets; limited causal interpretation |

| Deep Learning ( CNN) | Tropical rainforests, highly heterogeneous landscapes | 0.75–0.90 | 15–35 | Very High | Low | Moderate | Excellent in extracting complex spatial patterns; suitable for high-resolution data | Data- and compute-intensive; “black box” model behavior |

| Process-based Models (CASA, Biome-BGC) | All forest types | 0.50–0.75 | 30–50 | Medium–High | High | Moderate | Simulates ecosystem processes; enables long-term scenario modeling | Requires detailed environmental inputs; complex parameterization |

| Modeling Approach | Mean R² ± SD | Mean RMSE (Mg C ha⁻¹) ± SD | 95% CI for R² |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Regression | 0.62 ± 0.08 | 42 ± 6 | (0.60, 0.64) |

| Machine Learning | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 30 ± 5 | (0.76, 0.80) |

| Deep Learning | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 25 ± 4 | (0.83, 0.87) |

| Process-based Modeling | 0.66 ± 0.09 | 50 ± 8 | (0.63, 0.69) |

| Research Frontier | Key Questions | Methodological Approaches | Critical Data Needs |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Augmented Modeling | How to integrate time series into deep learning models? | Temporal CNNs, Transfer Learning | Time-labeled biomass datasets |

| Real-Time Biomass Monitoring | Can sub-monthly biomass trends be operationalized? | Edge Computing, SAR Time Series Analysis | Near-real-time calibration data |

| High-Resolution MRV Scaling | What is the cost–benefit threshold for VHR datasets? | Cost-Effectiveness Modeling, Sampling Optimization | Regional pilot studies linked to REDD+ |

| Sky-Ground Data Fusion | How to unify satellite, UAV, and field measurements? | Data Assimilation, AI Fusion Frameworks | Coordinated multi-source observations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).